Abstract

Despite the continued reliance on undergraduate students as research participants, there is an absence of valid, reliable measures of student perceptions of educational gains from research participation. In this article, we present two studies outlining the development and initial validation of a new measure, the student perceptions of the educational value of research participation scale. In Study One a pool of 28 items was developed from previous qualitative research and administered to a convenience sample of 68 Australian university student volunteers. Following principal axis factoring, a seven‐item unidimensional scale with good internal reliability (α = .82) was developed and validated against an existing measure of reactions to research participation. In Study Two, 104 members of a second‐year undergraduate psychology participant pool completed the measure. Confirmatory factor analysis supported a higher order two‐factor model (overall α = .82). Across both volunteer and participant pool samples, the educational value of research participation was rated more highly than the costs of research participation (emotional reactions and drawbacks of participating), indicating a positive cost–benefit ratio of research participation. This brief, internally reliable measure can be used in assessing students' perceptions of educational gain in both individual research projects and across research projects.

The majority of published psychological research is based on the use of undergraduate student participants (Higbee, Millard, & Folkman, Citation1982; Korn, Citation1999; Sieber & Saks, Citation1989; Wintre, North, & Sugar, Citation2001) who are easily accessible to university‐based researchers (Diamond & Reidpath, Citation1992; Sieber & Saks, Citation1989). Many universities utilise participant pools with mandated research participation for first‐year students. Penalties may be applied for non‐participation (Diamond & Reidpath, Citation1992). Even where participation is not mandated, incentives such as extra credit may be offered as an inducement to participate in research (Sieber & Saks, Citation1989).

This reliance on undergraduate students as research participants has been questioned on both research and ethical grounds. From a research perspective, the generalisability of the results based on undergraduate students has been questioned, with the potential for systematic biases in research findings identified as a particular concern (Henrich, Heine, & Norenzayan, Citation2010; Norenzayan & Heine, Citation2005; Sears, Citation1986). From an ethical perspective, concerns relate to dual relationships (Clark & McCann, Citation2005; Ferguson, Myrick, & Yonge, Citation2006; Ferguson, Yonge, & Myrick, Citation2004; Shi, Citation2006) and the perceptions of coercion associated with mandated and incentivised research participation (Miller & Kreiner, Citation2008). However, others (e.g., Dalziel, Citation1996) have argued that mandated and incentivised research participation for students is no more coercive than other course requirements such as exams and essays. Instead, Dalziel argued that the question is whether research participation is educationally justifiable.

The educational benefits suggested to result from the experiential learning involved in research participation include exposure to a variety of research methods and research processes that may develop students' research capabilities (Dalziel, Citation1996; Moreland, Citation1999). As such, research participation may contribute to both meeting the graduate attribute of Research Methods in Psychology (see Morris, Cranney, Jeong, & Mellish, Citation2013) and the development of psychological literacy; important learning outcomes for undergraduate psychology students (Cranney & Dunn, Citation2011; Morris et al., this issue). Qualitative and survey research findings to date indicate that some, but not all, students see research participation as having some educational value (e.g., Darling, Goedert, Ceynar, Shore, & Anderson, Citation2007), with benefits including learning about psychology, understanding research and ethical processes, and increasing interest in psychology (Landrum & Chastain, Citation1995; Moreland, Citation1999; Rosell et al., Citation2005; Trafimow, Madson, & Gwizdowski, Citation2006). Experimental research has provided limited support for the educational value of participating in research. Gil‐Gómez de Liaño, León, and Pascual‐Ezama (Citation2012) reported that students who participated in research (regardless of whether or not they engaged in activities designed to enhance their understanding of the experiments they participated in) scored higher on a research methods exam than those who did not. However, students self‐selected into the ‘no‐participation’ condition, thus systematically differing in motivation from students in the research participation conditions. Elliott, Rice, Trafimow, Madson, and Hipshur (Citation2010) randomly assigned students to a lecture or participation in an experiment followed by debriefing. While there was a main effect for knowledge gained from pre‐test to post‐test, there was no significant difference across conditions, suggesting no advantage of research participation over lecture attendance.

Ethical research balances potential benefits from research against potential risks to research participants and others. Student research participation provides clear benefits to researchers through providing access to research participants, with flow on benefits to society through the findings stemming from the research. However, the benefits to students in terms of educational gains are seldom assessed (Landrum & Chastain, Citation1999) and have not been adequately measured (typically relying on a very limited number of survey items), inhibiting the ability to conduct a full cost–benefit analysis of student research participation. In addition to research measuring actual education gains from research participation, there is a need for a psychometrically sound measure of student perceptions of education gains from research participation that can be used across studies and contexts.

In a previous qualitative study (Roberts & Allen, Citation2012), we asked 195 undergraduate students, ‘You've been invited to participate in a number of research projects this semester; what have you learned from this experience?’ Their responses were content analysed, and the key theme that emerged was that through participating in others' research, students gained insight into the research process, enhancing their knowledge about the conduct of psychological research.

Within this overarching theme of insight into the research process, eight subthemes were identified. The first six themes comprised insight into the range of topics and issues that were studied by psychologists and within the university; how ‘real’ research was conducted; the role of the researcher; the opportunity to view participation from the participant perspective; process issues in conducting research; and specific information on research methodologies (predominantly questionnaires). The seventh subtheme was participation as complementing the research methods taught in class, and the eighth was that the insights made could be applied in their own future research (Roberts & Allen, Citation2012).

In this article, we draw on the major theme and subthemes identified to develop and begin the validation of a new scale, the student perceptions of the educational value of research participation scale (SPEVRPS), which measures students' perceived educational gains from research participation. In a search of the literature, we could locate no measure of student perceptions of the educational value of research that could be used across disciplines and types of research. Given the concerns raised over whether student research participation is educationally and ethically justifiable, such a measure is required to begin to examine the cost–benefit ratio of student research participation.

Study One

The primary aim of Study One was to develop a brief measure of student perceptions of the educational value of research participation. In addition, this study begins the validation of the new measure, with the convergent and divergent validity of the SPEVRPS assessed in relation to the subscales of the reactions to research participation questionnaire‐revised (RRPQ‐R; Newman, Willard, Sinclair, & Kaloupek, Citation2001), a questionnaire designed to measure participants' evaluation of research participation, but that does not explicitly measure perceived educational gains. It was hypothesised that correlations between the new measure and the RRPQ‐R would be weak and positive with the ‘participation’ and ‘personal benefits’ subscales, weak and negative with the ‘emotional reactions’ and ‘perceived drawbacks’ subscales, and moderate and positive with the ‘global evaluation’ subscale.

As a further form of validation, the relationship between scores on the new measure and amount of research participation was examined. At the time of this first study (2010), there was no participant pool in our university, and volunteers were used in all research. It is likely that only students who perceive some sort of benefit from research participation would volunteer to participate in multiple research projects. Thus, it was hypothesised that there would be a positive correlation between scores on the new measure and the number of studies participated in over the semester.

The secondary aim of this study was to compare students' perceptions of the educational value of research against their perceptions of the costs of the research. It was hypothesised that the perceived educational benefits of research (measured by the newly developed SPEVRPS) would be greater than the perceived costs of participation (measured by the ‘emotional reactions’ and ‘drawbacks’ subscales of the RRPQ‐R).

Method

A cross‐sectional correlational design was utilised with data collected using an online survey.

Participants

Participants were a convenience sample of 68 Australian undergraduate psychology students. Reflecting the gender bias in the psychology student population, 83.8% of the research participants were female (male 13.2%, unstated 2.9%). Participants ranged in age from 17 to 51 (M = 24.7, standard deviation (SD) = 8.34). Almost half (45.6%) were first‐year students, with second year (19.1%), third year (11.8%), and fourth year (20.6%) undergraduate students also represented. All participants had taken part in at least one previous study during the semester (range = 1–12; median = 3). The majority (98.5%) had participated in questionnaire or survey research, 23.5% had participated in experimental research, and 5.9% had participated in a qualitative study.

Measures

An online questionnaire was constructed containing 28 items designed to measure student perceptions of the educational value of research participation, the RRPQ‐R, single‐item measures of demographics (age, gender, and year of study), and the number and type of research projects participated in.

Perceptions of the educational value of research

Based on our prior qualitative analysis (Roberts & Allen, Citation2012), we developed a pool of 28 items designed to provide measures of seven of the eight subthemes of insight into the research process.Footnote1 Items were reviewed to ensure that they represented views expressed by participants in the original qualitative study. Each was rated on a scale ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree.

RRPQ‐R (Newman et al., Citation2001)

The RRPQ‐R is a 23‐item scale designed to measure ethical constructs associated with research participation. The measure comprises five subscales named ‘participation’ (four items; example item, ‘I like the idea that I contributed to science’), ‘personal benefits’ (four items; example item, ‘I gained insight about my experiences through research participation’), ‘emotional reactions’ (four items; example item, ‘The research made me think about things I didn't want to think about’), ‘perceived drawbacks’ (six items; example item, ‘I found the questions too personal’), and ‘global evaluation’ (five items; example item, ‘I was treated with respect and dignity’). One item was reworded from ‘I understood the consent form’ to ‘I understood the information sheet/consent form’. In the current study, each item was rated on a scale from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree.

Previous exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses support the five factor structure of the RRPQ‐R (Newman et al., Citation2001). When used in previous research, the internal reliabilities of the subscales have mostly fallen within acceptable ranges (α = .53–.87; DePrince & Chu, Citation2008; Edwards, Kearns, Calhoun, & Gidycz, Citation2009; Newman et al., Citation2001).

Procedure

Prior to commencing the research, ethics approval was obtained from Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee. To prevent perceptions of coercion that could arise from our dual roles as lecturers and researchers, data collection was online, anonymous, and completed outside of class time. Recruitment for the research commenced late in semester 2, 2010, through advertisements on student learning management system sites and announcements during lectures. Participation in the research was voluntary, and no incentive for participation was offered. Interested students were provided with a link to an online participant information sheet, and upon consenting were redirected to an online questionnaire.

Of 82 survey responses, 11 were deleted because the SPEVRPS items had not been completed, and three cases were removed that did not meet the inclusion criteria. Across the survey there were 24 missing data points (0.06% missing data). A missing values analysis indicated that these data were missing completely at random, Little's Missing Completely at Random test χ2(635, n = 68) = 652.66, p = .276. Missing data points on scale measures were replaced using expectation‐maximisation.

Results

Principal axis factoring with varimax rotation was used to explore the factor structure of the 28 newly created student perceptions of the educational value of research participation items. Nine factors were extracted with eigenvalues greater than one. However, the unrotated factor solution (with most items loading more strongly on the first factor than other factors) and scree plot (steep curve between first factor with an eigenvalue of 9.5 and all other factors with eigenvalues between 2.2 and 1.0) suggested only one main factor underlying the items. To develop a short measure with strong content validity, the highest loading item for each of the seven subthemes (see Table ) was selected for a second‐factor analysis. Principal axis factoring extracted one factor with an eigenvalue over 1 with all item loadings above.4, confirming the unidimensionality of the measure. The items and factor loadings are presented in Table . The Cronbach's alpha for this factor was.82, suggesting good internal reliability in this sample.

Table 1. Subthemes, selected items, and factor loadings for the seven‐item student perceptions of the educational value of research participation scale

For each respondent, the mean of the seven items was calculated to provide a scale score. This new measure is called the SPEVRPS. Descriptive statistics for the new measure and the RRPQ‐R are presented in Table .

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and reliability coefficients for the SPEVRPS and RRPQ‐R in Study One and Study Two

The relationships between the SPEVRPS and the subscales of the RRPQ‐R were examined to assess convergent and divergent validity through a series of bivariate correlations (n = 68). As hypothesised, there were significant positive correlations between the SPEVRPS and ‘participation’ (r = .27, p = .024), ‘personal benefits’ (r = .33, p = .006), and ‘global evaluation’ (r = .44, p < .001) subscales of the RRPQ‐R. There was a significant negative correlation between the SPEVRPS and the ‘perceived drawbacks’ subscale (r = −.25, p = .041) and a negative, but non‐significant, correlation with the ‘emotional reactions’ subscale (r = −.14, p = .243) of the RRPQ‐R.

The SPEVRPS was also examined in relation to demographic and participation variables (n = 68). As hypothesised, there was a positive correlation between the SPEVRPS and the number of research projects participated in over the semester (rs = .32, p = .007). There was no significant relationship with age (rs = .08, p = .440) or gender, t(64) = −0.97, p = .337.

To compare students' perceptions of the educational value of research against their perceptions of the costs of the research, two paired samples t‐tests were conducted, comparing scores on the SPEVRPS to scores on the ‘emotional reactions’ and ‘drawbacks’ subscales of the RRPQ‐R. As hypothesised, scores on the SPEVRPS (M = 4.01, SD = .49) were significantly higher than scores on the ‘emotional reactions’ subscale (M = 1.77, SD = .69), t(67) = 20.40, p < .001, d = 3.80, and the ‘perceived drawbacks’ subscale (M = 2.09, SD = .55), t(67) = 19.21, p < .001, d = 3.69, of the RRPQ‐R.

Discussion

In Study One, we have presented the development and initial validation of a new brief measure of student perceptions of the education value of research, the SPEVRPS. This measure has good content validity, covering seven subthemes of ‘insight into the research process’ that emerged as the key educational outcome of research participation in previous qualitative research (Roberts & Allen, Citation2012). Exploratory factor analysis and internal reliability testing indicated the measure is unidimensional and has good internal consistency. The SPEVRPS correlated with subscales of the RRPQ‐R in the expected directions, supporting the convergent and divergent validity of the measure. In addition, scores on the SPEVRPS were positively correlated with the number of research studies participated in over the semester, and students rated the perceived benefits of participating in research higher than the perceived costs.

Further validation of the measure is required. The sample for this study comprised students who volunteered to participate in research. It will be important to examine whether the psychometric properties of the measure hold when the sample comprises students who are members of a participant pool.

Study Two

The aim of Study Two was to continue the validation of the SPEVRPS on a sample of undergraduate psychology students recruited through a participant pool. The introduction of an undergraduate participant pool to our university in 2012 provided an ideal opportunity to collect comparative data to Study One. This study examines the factor structure and the test–retest reliability of the measure within a participant pool sample. It further examines the relationship between the SPEVRPS and the RRPQ‐R to determine if the benefits of participating in research continue to outweigh the costs of participating in research for members of a participant pool.

Method

A cross‐sectional correlational design was utilised with data collected using an online survey.

Participants

All students in the second year undergraduate psychology participant pool (n = 144) had the option of participating in this study. Of these, 104 (73.5% female) completed the survey, providing a response rate of 72%. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 47 (M = 20.7, SD = 4.04). All participants had taken part in at least one previous research study within the university that semester (range = 1–9; median = 5). All had participated in questionnaire research, 39.8% had participated in experimental research, and 6.1% had participated in qualitative research.

Measures

An online questionnaire was constructed containing the new seven item SPEVRPS, the RRPQ‐R, and demographic questions.

Procedure

Ethics approval was obtained from the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee. Recruitment for the research commenced in semester 1, 2012, through the second year participant pool. Interested students were provided with a link to an online participant information sheet, which linked them to an online questionnaire. Students completing the survey were assigned credits towards their research participation requirement. Students not participating in this research could participate in other research studies or complete an alternative activity. At the end of the questionnaire, participants were invited to indicate their interest in completing a second survey 2 weeks later, containing the SPEVRPS only. Twenty‐two participants completed the second survey between 13 and 17 days after completion of the initial survey.

There were three missing data points across the scales, and these were replaced using mean substitution. Missing data points on demographic questions (gender = 6, age = 8) were not replaced.

Results

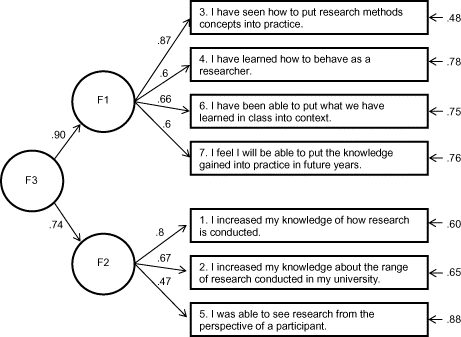

Confirmatory factor analysis of the SPEVRPS was conducted using EQS (version 6.2) (EQS 6.2 for Windows: Multivariate Software, Inc., Encino, CA, USA). A one‐factor model, as suggested by Study One, was tested against the recommended cut‐offs for goodness of fit of four fit indices: the Satorra–Bentler chi‐square divided by degrees of freedom, the comparative fit index, the non‐normed fit index, and the root mean square error of approximation. The fit statistics suggested the fit of the one factor model was less than optimal (see Table ). Following exploratory factor analysis, which suggested a two factor model may provide a better fit to the data, three further models were tested using confirmatory factor analysis: a correlated two‐factor model, an uncorrelated two‐factor model, and a higher order model. Fit indices for each of the models are presented in Table . The higher order model (see Fig. 1) is preferred to the other models because of superior fit indices. The first factor relates to the practice of research, and the second factor relates to knowledge of research. The full measure has good internal reliability, and as such is suitable for use as a single measure. Descriptive statistics and reliability coefficients for the SPEVRPS and the RRPQ‐R in this sample are presented in Table .

Table 3. Fit indices for confirmatory factor analysis models (robust statistics)

The relationships between the SPEVRPS and the subscales of the RRPQ‐R were examined to determine convergent and divergent validity through a series of bivariate correlations (n = 104). As hypothesised, there were significant positive correlations between the SPEVRPS and ‘participation’ (r = .47, p < .001), ‘personal benefits’ (r = .60, p < .001), and the ‘global evaluation’ (r = .23, p = .03) subscales of the RRPQ‐R. There was a significant negative correlation between the SPEVRPS and the ‘perceived drawbacks’ subscale (r = −.42, p < .001) and an unexpected positive correlation with the ‘emotional reactions’ subscale (r = .23, p = .02) of the RRPQ‐R. There was no significant relationship between the SPEVRPS and the number of research projects participated in over the semester (r = .04, p = .71), age (rs = −.24, p = .82), or gender, t(96) = −1.97, p = .06.

To examine test–retest reliability, the time 1 and time 2 scores were correlated for the 22 participants who completed both surveys. A moderate significant correlation was found (r = .47, p = .03).

To compare students' perceptions of the educational value of research against their perceptions of the costs of the research, two paired samples t‐tests were conducted, comparing scores on the SPEVRPS to scores on the ‘emotional reactions’ and ‘drawbacks’ subscales of the RRPQ‐R. Scores on the SPEVRPS (M = 3.90, SD = .48) were significantly higher than scores on the ‘emotional reactions’ subscale (M = 2.01, SD = .73), t(103) = 24.81, p < .001, d = 3.12, and the ‘perceived drawbacks’ subscale (M = 2.54, SD = .69), t(103) = 14.01, p < .001, d = 2.32, of the RRPQ‐R.

Comparison across samples

Independent samples t‐tests were conducted to compare the scores on the SPEVRPS and RRPQ‐R across the volunteer and participant pool samples. The results are summarised in Table . A consistent pattern of lower scores on measures of the benefits of research participation and higher scores on the disadvantages of research participation in the participant pool sample in comparison with the volunteer sample emerged, with small to large effect sizes.

Discussion

In Study Two, using a sample of students recruited through an undergraduate psychology participant pool, the findings from Study One were largely replicated. In this sample, confirmatory factor analysis indicated that a higher order model best represented the measure, in contrast to the unidimensional factor structure found in Study One. We speculate that where students engage in a greater number of studies through participant pools, they begin to more clearly differentiate between the knowledge and practice of research. The internal reliability of the overall scale remained high. The test–retest reliability, conducted on a small sample, was lower than desirable and requires further testing on a larger sample. The SPEVRPS mostly correlated with subscales of the RRPQ‐R in the expected directions, supporting the convergent and divergent validity of the measure. The positive correlation between the SPEVRPS and ‘emotional reactions’ subscale was unexpected, and further research is required to see if this finding is replicated. Students rated the perceived benefits of participating in research more highly than the perceived costs of participating in research.

Overall Discussion

The SPEVRPS is a brief, reliable measure of student perceptions of the educational value of research participation. Combined with the promising psychometric properties, the brevity of the SPEVRPS (seven items) means that it may be suitable for use both within individual research projects and across research projects. It could be included at the end of individual research projects to provide an indication of the perceived educational value of the particular project. Alternatively, the SPEVRPS is suitable for assessing students' perceptions of the educational value of participation across multiple studies, and it could be useful to researchers seeking to develop an evidence base to support the integration of participant pools in undergraduate psychology courses that is comparable with the evidence bases that have been developed around other pedagogic tools and techniques common to the modern psychology classroom (see, e.g., Dunn, Saville, Baker, & Marek, Citation2013).

Identification of how students perceive the educational value of research participation provides an important first step in evaluating the possible benefits of research participation. However, this should not be seen as an end in itself. Previous research has suggested that not all students view research participation as positive or educational (Coulter, Citation1986; Roberts & Allen, Citation2012). Increasing the pedagogic value of student research participation for all students may require a closer integration of research participation and the teaching of research methods (Dalziel, Citation1996) through the provision of debriefing directly after each participation experience (Coulter, Citation1986; Sharpe & Faye, Citation2009; Sieber, Citation1999), later feedback (Dalziel, Citation1996), and class assignments relating to the participation experience (Moyer & Franklin, Citation2011). Increasing the educational value of research participation will contribute to developing the psychological literacy of undergraduate students, through enhancing knowledge and understanding of scientific and ethical research practices.

The SPEVRPS can be used on its own or in conjunction with the RRPQ‐R to provide a more comprehensive measure of the costs and benefits of research participation. The SPEVRPS provides researchers with the opportunity to revisit the key ethical question of whether potential benefits from research outweigh potential risks to research participants. The findings from these initial studies suggest that students rate the perceived benefits of participating in research more highly than the perceived costs of participating in research. However, the ratio of benefits to costs varied across samples, with the participant pool sample perceiving less benefits and greater costs than the volunteer sample. Future research could examine whether this ratio changes across participation in research of differing levels of sensitivity, requiring differing commitment of time or effort, or using different methodologies (e.g., experimental versus survey research).

In summary, this article has presented the development and initial validation of a measure of the perceived educational value of research participation, the SPEVRPS. This is a brief, internally reliable measure that can be used in assessing students' perceptions of educational gain in both individual research projects and across research projects.

Notes

1. We developed four additional items linked to the subtheme of questionnaire design. However, these were excluded from subsequent analyses, as our aim was to develop a measure that could be used across all types of research.

References

- Clark, E., & Mccann, T. (2005). Researching students: An ethical dilemma. Nurse Researcher, 12(3), 42–51.

- Coulter, X. (1986). Academic value of research participation by undergraduates. American Psychologist, 41, 317. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037//0003‐066X.41.3.317.a

- Cranney, J. , & Dunn, D. (Eds.) (2011). The psychologically literate citizen: Foundations and global perspectives. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Dalziel, J. R. (1996). Students as research subjects: Ethical and educational issues. Australian Psychologist, 31, 119–123. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00050069608260190

- Darling, J., Goedert, K., Ceynar, M., Shore, W., & Anderson, D. (2007). Learning about the means to an end: What US introductory psychology students report about experimental participation. Psychology Learning and Teaching, 6, 91–97. doi:https://doi.org/10.2304/plat.2007.6.2.91

- Deprince, A. P., & Chu, A. (2008). Perceived benefits in trauma research: Examining methodological and individual difference factors in responses to research participation. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research, 3, 35–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.1525/jer.2008.3.1.35

- Diamond, M. R., & Reidpath, D. D. (1992). Psychology ethics down under: A survey of student subject pools in Australia. Ethics and Behavior, 2, 101–108. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327019eb0202_3

- Dunn, D., Saville, B. K., Baker, S. C., & Marek, P. (2013). Evidence‐based teaching: Tools and techniques that promote learning in the psychology classroom. Australian Journal of Psychology 65(1), 5–13.

- Edwards, K. M., Kearns, M. C., Calhoun, K. S., & Gidycz, C. A. (2009). College women's reactions to sexual assault research participation: Is it distressing? Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33, 225–234. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471‐6402.2009.01492.x

- Elliott, L. J., Rice, S., Trafimow, D., Madson, L., & Hipshur, M. F. (2010). Research participation versus classroom lecture: A comparison of student learning. Teaching of Psychology, 37, 129–131. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00986281003626862

- Ferguson, L. M., Myrick, F., & Yonge, O. (2006). Ethically involving students in faculty research. Nurse Education in Practice, 6, 397–403. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2006.07.016

- Ferguson, L. M., Yonge, O., & Myrick, F. (2004). Students' involvement in faculty research: Ethical and methodological issues. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 3(4), 1–14.

- Gil‐gómez de liaño B., León, O. F., & Pascual‐ezama, D. (2012). Research participation improves student's exam performance. Spanish Journal of Psychology, 15, 544–550. doi:https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_SJOP.2012.v15.n2.38865

- Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33, 61–135. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0999152X

- Higbee, K., Millard, R., & Folkman, J. (1982). Social psychology research during the 1970s: Predominance of experimentation and college students. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 8, 180–183. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/014616728281028

- Korn, J. H. (1999). Students' roles, rights, and responsibilities as research participants. In M. E. Ware & C. L. Brewer (Eds.), Handbook for teaching statistics and research methods (2nd ed.). (pp. 113–118). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Landrum, R. E., & Chastain, G. (1995). Experiment spot‐checks: A method for assessing the educational value of undergraduate participation in research. IRB: Ethics and Human Research, 17, 4–6.

- Landrum, R. E., & Chastain, G. (1999). Subject pool policies in undergraduate‐only departments: Results from a nationwide survey. In G. Chastain & R. E. Landrum (Eds.), Protecting human subjects: Departmental subject pools and institutional review boards (pp. 25–43). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Miller, W. E., & Kreiner, D. S. (2008). Student perception of coercion to participate in psychological research. North American Journal of Psychology, 10, 53–64.

- Moreland, R. L. (1999). Evaluating students' research experiences via credit slips. In G. Chastain & R. E. Landrum (Eds.), Protecting human subjects: Departmental subject pools and institutional review boards (pp. 87–108). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Morris, S., Cranney, J., Jeong, J. M., & Mellish, L. (2013). Developing psychological literacy: Student perceptions of graduate attributes. Australian Journal of Psychology 65(1), 54–62.

- Moyer, A., & Franklin, N. (2011). Strengthening the educational value of undergraduate participation in research as part of a psychology department subject pool. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 6, 75–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1525/jer.2011.6.1.75

- Newman, E., Willard, T., Sinclair, R., & Kaloupek, D. (2001). Empirically supported ethical research practice: The costs and benefits of research from the participants' view. Accountability in Research, 8, 309–329. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08989620108573983

- Norenzayan, A., & Heine, S. J. (2005). Psychological universals: What are they and how can we know? Psychological Bulletin, 131, 763–784. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033‐2909.131.5.763

- Roberts, L. D., & Allen, P. J. (2012). Student perspectives on the value of research participation. In S. Mccarthy , K. L. Dickson , J. Cranney , A. Trapp , & V. Karandashev (Eds.), Teaching psychology around the world, Volume 3 (pp. 198–212). Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Rosell, M. C., Beck, D. M., Luther, K. E., Goedert, K. M., Shore, W. J., & Anderson, D. D. (2005). The pedagogical value of experimental participation paired with course content. Teaching of Psychology, 32, 95–99. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328023top3202_3

- Sears, D. O. (1986). College sophomores in the laboratory: Influences of a narrow data base on social psychology's view of human nature. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 515–530. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022‐3514.51.3.515

- Sharpe, D., & Faye, C. (2009). A second look at debriefing practices: Madness in our method? Ethics and Behavior, 19, 432–447. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10508420903035455

- Shi, L. (2006). Students as research participants or as learners? Journal of Academic Ethics, 4, 205–220. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805‐006‐9028‐y.

- Sieber, J. E. (1999). What makes a subject pool (un)ethical. In G. Chastain & R. E. Landrum (Eds.), Protecting human subjects: Departmental subject pools and institutional review boards (pp. 43–68). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Sieber, J. E., & Saks, M. J. (1989). A census of subject pool characteristics and policies. American Psychologist, 44, 1053–1061. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0003‐066X.44.7.1053

- Trafimow, D., Madson, L., & Gwizdowski, L. (2006). Introductory psychology students' perceptions of alternatives to research participation. Teaching of Psychology, 33, 247–249. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328023top3304_7

- Wintre, M. G., North, C., & Sugar, L. A. (2001). Psychologists' response to criticisms about research based on undergraduate participants: A developmental perspective. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 42, 216–225.