Abstract

This article describes a pilot evaluation involving teaching and learning activities focussed on developing intercultural competencies in an undergraduate psychology unit. Specifically, first year psychology students engaged in two tasks derived from the alliance building and cultural mapping methods of an existing intercultural training resource—the Excellence in Cultural Experiential Learning and Leadership (EXCELL; Mak, Westwood, Barker, & Ishiyama) programme. At the end of the semester, 94 first year psychology students (mean age = 21.6, standard deviation = 6.4) completed a survey about their educational and intercultural experiences. Quantitative results indicated that participants reported some improvement in various aspects of cultural learning, including being better prepared to communicate with people from different cultures. Thematic analysis of student responses to an open‐ended question regarding cultural learning indicated that students perceived a range of benefits from intercultural training, including increased knowledge, respect, and competencies for engaging with others from different cultures. Students also reported that participation in the training would lead to increased scope and breadth of practice in their future careers. Suggestions for future research about teaching of intercultural competencies within undergraduate curricula are discussed.

The composition of undergraduate psychology programmes has recently been a focus of discussion internationally, including in Australia (Cranney, Botwood, & Morris, Citation2012; Cranney et al., Citation2009; Dunn, Saville, & Baker, Citation2013), the USA (e.g., American Psychological Association, Citation2006; Halpern, Citation2010; Leong, Leach, & Malikiosi‐Loizos, Citation2012; Stoloff et al., Citation2010; Wadkins & Miller, Citation2011), and also the UK (Trapp et al., Citation2011). This discussion has largely centred on issues such as determination of the key core units that should be taught within psychology degrees; the kinds of skills that will best prepare psychology graduates for work in the future; the sorts of experiences that will provide psychology graduates with the ‘competitive edge'—especially in the field of healthcare; and how best to respond to the increased diversity of both the student population and the community in which students will live and work (Trapp et al., Citation2011).

The Australian Psychology Accreditation Council's (APAC) accreditation standards for undergraduate psychology programmes require curricula that address six specific graduate attributes (APAC, Citation2010). However, the extent to which these attributes hold currency and relevance for psychology undergraduate training has been questioned. Cranney and Dunn (Citation2011) argue that, as we head towards working in an increasingly complex, technological, and globalised society, graduate attributes adopted in the future by APAC should emphasise not only psychological literacy (the capacity to adaptively and intentionally apply psychology to meet personal, professional, and societal needs; Chester, Xenos, Burton, & Elgar, Citation2013; Cranney & Dunn, Citation2011; Morris, Cranney, Jeong, & Mellish, Citation2013) but also global citizenship and employability (Cranney et al., Citation2012). Cranney and Dunn (Citation2011, p. 10) define global citizenship with reference to psychological literacy by suggesting that psychologically literate citizens engage ‘… to solve problems in an ethical and socially responsible manner in a way that directly benefits their communities’. Furthermore, Crowe (Citation2012, p. 62), in his Australian Psychological Society Presidential initiative on the future of psychological science in Australia, recommended that in years 1–3 of tertiary psychology education, ‘the applications to the workplace are particularly relevant to employability … and applications to communities and societies can be relevant to global citizenship’.

In preparing for these potential changes to the required curriculum, educators need to consider ways to incorporate learning that addresses emerging attributes such as global citizenship and employability, while also providing a consistent standard of education that includes a focus on the scientific study of human behaviour. Currently, there are few evidence‐based approaches that inform educators about how to do this. As highlighted by Wilson‐Doenges and Gurung (2013) and Dunn, Saville, Baker, and Marek (Citation2013), best practice in the scholarship of teaching and learning in undergraduate psychology needs to be underpinned by a clear pedagogy and supported by evidence.

Within psychology, few resources are currently available to assist, for example, with the development of practical skills in communication, as is required for communicating within and across culture boundaries. Increased intercultural awareness and skills are particularly relevant for developing global citizenship competencies for domestic students who do not have the experiences or opportunities to study abroad. Traditional psychological approaches to the teaching of ‘culture’, at least as we have experienced in Australia, have emphasised ethnocentric concepts conveyed in North American literature. This approach to the teaching of culture is unlikely to lead to the development of global citizens. Indeed, Trapp et al. (Citation2011), when describing approaches to psychology undergraduate training in the UK, suggest that approaches that deal with cultural diversity in meaningful, and non‐Western ways, are required.

An approach that may be more appropriate in the teaching and learning of cultural skills, and in particular, intercultural communication and/or competencies, is known as the Excellence in Cultural Experiential Learning and Leadership (EXCELL; Mak, Westwood, Barker, & Ishiyama, Citation1998) programme. EXCELL aims to provide a structured approach to assist individuals to develop key generic social competencies for accessing and negotiating in challenging intercultural encounters (Westwood, Mak, Barker, & Ishiyama, Citation2000). The key EXCELL competencies vital for accessing a new culture are making contact, seeking help (which includes making a request), and participating in a group. The key competencies for negotiation are refusing a request, expressing disagreement, and giving feedback.

EXCELL has a strong theoretical base that draws on an integration of learning paradigms, including operant and classical conditioning, social cognitive learning, and role‐based learning (Mak, Westwood, Ishiyama, & Barker, Citation1999). Ho, Holmes, and Cooper (Citation2004) review revealed that the programme improved participants' social interaction skills and intercultural social self‐efficacy while reducing the tendency for social avoidance. The entire EXCELL programme, successfully integrated within the curriculum of a communication course, was found to enhance students' intercultural social confidence, interaction skills, and intercultural friendships (Mak & Buckingham, Citation2007). Mak and Kennedy (Citation2012) reported that experiential learning activities based on two EXCELL components (the alliance building and cultural mapping methods) in two to three classes improved students' cultural awareness and understanding of the cultural context of social interactions in a first‐year unit in politics and a postgraduate unit in organisational behaviour. Mak (Citation2012) outlines how pedagogy involving cultural mapping activities in two tutorials can be integrated with the subject content of a fourth‐year unit in health psychology in embedding the development of intercultural competency.

Alliance building (which incorporates cultural validation) provides group facilitation strategies designed to build a sense of cultural safety and to encourage sharing in a group (which can be a physical or a virtual community), while validating the original cultural backgrounds of members from diverse backgrounds (Mak & Kennedy, Citation2012; Mak et al., Citation1998). Techniques in alliance building include experiential activities that provide opportunities for all members to share aspects of their original culture, and to draw out and reflect on similarities in observations and everyday experiences despite cultural differences.

The second EXCELL component—cultural mapping—provides a schematic framework for mapping or making explicit a sequence of micro verbal and non‐verbal behaviours to support the effective engagement in what may be construed as a challenging intercultural social scenario (Mak et al., Citation1998). The framework involves the specification of the context of the encounter (i.e., what is the scenario and which key competency or competencies are involved), and then the behaviours (both verbal and non‐verbal) and underlying values for one effective way to navigate the encounter. The behaviours and values are presented in terms of the approach, bridging, communicating, and developing/departure (ABCD) phases. Examples of EXCELL cultural maps are available from https://sites.google.com/site/internationalisationathome/professional‐development

Explicit and practical training in developing intercultural awareness and communication skills are relevant for developing ‘global citizenship’ competencies. As well, generic intercultural competencies are clearly needed for employment in multicultural societies such as Australia. Thus, application of the EXCELL model in undergraduate psychology may provide an appropriate theoretically based model that facilitates an increase in intercultural competencies for communicating across cultures and may help support curriculum development pertaining to future APAC competencies involving global citizenship and employability. The aim of this pilot study was to assess the implementation of an EXCELL alliance building and an EXCELL cultural mapping activity in a first year psychology undergraduate unit.

Method

Participants

Participants were 94 psychology 101 students who self‐identified as having attended the tutorial involving application of the EXCELL model. There were 60 females (64%) and 34 males (36%) with a mean age of 21.6 (standard deviation (SD) = 6.4). Three participants were international students, with the majority enrolled as domestic students (n = 91). Domestic students identified themselves as being from a variety of backgrounds including Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander (n = 1), Anglo‐Australian (n = 55), European (n = 15), Chinese (n = 1), Indian (n = 2), Asian (n = 1), mixed ethnicity (n = 7), and other (n = 9).

Measures

Students were invited to complete an anonymous online survey on students' educational and intercultural experiences at the end of semester. The survey contained 47 closed‐ended items about student background (e.g., country of birth), interactions with domestic and international students, and a 13‐item cultural learning measure. The cultural learning items measured students' perceptions about the development of their knowledge, skills, and attitudes in intercultural interactions through the undergraduate psychology unit. These items were adapted from MacNab and Worthley's (Citation2012) measure of cultural intelligence development and Mak's (Citation2012) measure of students' cultural learning through an internationalised curriculum. An example of an item is, ‘With regards to Psychology 101, I have developed a better understanding of cross‐cultural interpersonal skills.’ Responses were rated on a 5‐point Likert scale (1 = strongly agree, 2 = agree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = disagree, 5 = strongly disagree); lower scores indicate greater cultural learning. The overall scale demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach's α = .95).

The survey also included an open‐ended question that asked students to indicate ways in which they could apply the learning about intercultural competencies to their professional preparation.

Approach to development of intercultural competence

The training of students' intercultural competencies was integrated into a large first year undergraduate psychology unit (n = 420) at the University of Canberra in semester 1, 2012. This curriculum renewal was part of the ‘Internationalisation at Home’ national priority project (ALTC PP10‐1810), funded by the Australian Government Office for Learning and Teaching (see https://sites.google.com/site/internationalisationathome). The training was adapted from two components of the EXCELL programme (Mak et al., Citation1998): alliance building activities early in semester and a cultural mapping experiential exercise 8 weeks later (within a 14‐week teaching period).

Alliance building exercise

A critical self‐reflection activity was used as an alliance building exercise. Garvey (Citation2007) argues that critical self‐reflection is a necessary precursor to the development of cultural competencies as required to work within and across cultures. During the first lecture, students were asked to introduce themselves to the person sitting alongside them and were asked to post to an online discussion forum (following the lecture) their reflections with respect to two key issues. First, students were asked to reflect upon the following question: What do introductions tell us about ourselves and others? Second, students were asked to reflect upon Dorothea Mackellar's poem, ‘My Country’ (see http://www.dorotheamackellar.com.au/archive/mycountry.htm) and answer these questions described in Garvey (Citation2007, p. 31), ‘Do McKellar's [sic] descriptions reflect your upbringing? Can you relate to one (or more) of the landscapes she describes? Do you retain a connection to that place? How was your connection made and developed?’ International students were encouraged to share their experiences regarding introductions, for example, they were asked to draw out connections with their own country or culture.

Cultural mapping exercise

Eight weeks later, approximately 125 students attended a 2‐hr face‐to‐face tutorial. The tutorial included an EXCELL cultural mapping exercise. Tutors modelled the EXCELL mapping method of breaking down a dyadic interaction into the model's ABCD steps. Each tutor modelled verbal and non‐verbal behaviours using an example scenario of approaching and making social contact with an Australian male student (aged 19) to request that he consider becoming a member of the University's Psychology Society. In small groups, students were given one of several scenarios to work on. Each scenario included two specific competencies—making social contact and making a request. In all instances, the request was the same (requesting that the person become a member of the University's Psychology Society). However, the cultural group used in the scenario differed: Saudi‐Arabian woman; Indonesian male student, aged 20; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander woman, aged 45.

Procedure

Following approval by the University of Canberra Committee for Ethics in Human Research, an invitation containing a hyperlink to an online survey was distributed to students in the final week of semester. An opportunity to enter a draw to win a $200 shopping voucher was offered as an incentive for completing the survey. The survey took respondents approximately 10-min to complete.

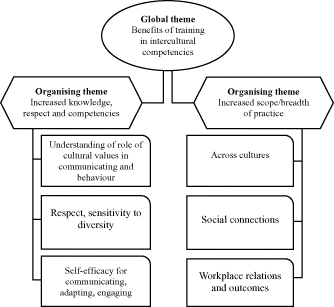

Open‐text responses were downloaded into a word processing document and analysed according to the method of analysis described by Attride‐Stirling (Citation2001); that is, themes were systematically organised into a hierarchy of themes, including global themes, organising themes, and basic themes. At the first step, each student statement was entered into the left column of a table and coded in the right column to identify basic themes. A third column was then added while the table was inspected to assess for common basic themes. For example, notations were made in the third column with regard to duplications in themes and themes that occurred infrequently were recorded. At the third step, a thematic model (i.e., a figure) was developed whereby common basic themes (e.g., duplicated themes or themes with similar meanings) were grouped into categories, known as ‘organising themes’. The labels used for these organising themes were not based on previous research or theory but were instead grounded in the data (see Glaser, Citation1992) and principally reflected the language used by students. Then, each of the organising themes—along with basic themes— was summarised in a table with a range of supportive statements (i.e., participants' quotes) provided as evidence for the emergent themes. Each of these themes (organising and basic) was then grouped into a higher order theme (i.e., global theme), and a label was chosen to reflect the meaning of the data as a whole. Finally, exceptions, or points of disagreement noted within statements provided by students, were also recorded to enable reporting.

Results

The end‐of‐semester survey showed that respondents tended to agree that their cultural competence had been developed through the introductory psychology unit (see Table ). Respondents generally agreed that they enjoyed interaction with people from different cultures. The highest ranked effects involved being more conscious of and better prepared to adjust cultural knowledge when interacting with people from different cultural backgrounds. Respondents also indicated a relatively strong agreement that they were now more familiar with the role of culture in their chosen field of study. Arguably, more difficult cross‐cultural competencies, such as being equipped to enjoy living in unfamiliar cultures, were less impacted.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for self‐perceived change in cultural competence

Qualitative analysis on applications of intercultural competencies

Open‐text responses (n = 73) to the question on the ways in which students could apply the learning about intercultural competencies were analysed according to Attride‐Stirling's (Citation2001) method (see procedure). Results of the thematic analysis are summarised within the global theme, benefits of training, two organising themes, and six basic themes, as shown in Figure 1.

Organising theme: Increased knowledge, respect, and competencies

Students described a range of benefits from training (global theme 1) with statements falling within two organising themes. The first theme, increased knowledge, respect and competencies, contained three basic themes reflective of student statements: increased respect and sensitivity to diversity; increased understanding of the role of cultural values underpinning communication and behaviour; and increased self‐efficacy for communicating, adapting to, and engaging with other cultures. Table shows statements reflecting these three basic themes.

Table 2. Basic themes and supporting statements for organising theme on increased knowledge, respect and competencies

Organising theme: Increased scope and breadth of professional practice

Within this organising theme, students' statements suggested that they perceived that the training they had received in the unit would ultimately extend the scope and breadth of their professional practice across cultures, and in relation to social connections, and workplace relations and outcomes. These statements, shown in Table , were evident for students who were studying psychology, as well students in other degrees.

Table 3. Basic themes and supporting statements for organising theme on increased Scope and breadth of practice

Other comments

Although the majority of comments were positive, there were some critical comments, for example: ‘The learning about cultures was pointless and was teaching aspects of cultures everyone already knows’; ‘I've lived in many different cultures around the world … so this course, culturally, has taught me nothing …’; and ‘There has not been enough psychological research around various cultures’.

Additional evidence of engagement with training materials

Additional to the survey results, evidence of engagement with the alliance‐building activity was indicated with many students (n = 125 of n = 420 enrolled) voluntarily posting comments to the discussion forum on the unit's website. In the tutorial where the cultural mapping method was taught, students worked together as small groups to successfully develop 45 maps involving the competencies of making social contact and making a request. Although tutors were instructed to provide an equal number of cultural group examples within each tutorial group, the numbers of maps for each cultural group example differed: Indonesian male (11 maps), Saudi Arabian woman (18 maps), and Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander woman (16). Some students (n = 4) crossed out the scenario description involving the Aboriginal woman and instead chose to work on the scenario involving the Saudi‐Arabian woman.

Discussion

We have described a teaching approach aimed at integrating explicit teaching of intercultural competency training within an accredited introductory psychology unit. In this section, we will discuss some initial observations on the basis of the pilot data presented and reflect upon our experience in implementing this approach. Suggestions for teaching, measurement and assessments of effectiveness, involving the teaching of cultural diversity and intercultural competencies within undergraduate psychology programmes, are highlighted.

Two main teaching activities formed the basis of this pilot study. The first activity involved an EXCELL alliance‐building exercise, which aimed to create a culturally inclusive learning environment that facilitated the validation of students' own cultural origin and stimulated critical self‐reflection. Garvey (Citation2007) argues, for example, that critical self‐reflection is a necessary precursor in the subsequent development of intercultural competencies. The second activity involved the explicit application of the EXCELL's cultural mapping activity (Mak et al., Citation1998). Students readily engaged with both the alliance building and the cultural mapping activities; however, a few students appeared reluctant to develop maps for approaching and making social contact with an Aboriginal woman. A lack of knowledge about Aboriginal people may underpin this observation. Alternatively, the apparent lack of engagement with this scenario may also reflect a particular tutor's lack of knowledge, training, or alternatively, may be indicative of a tutor's portrayal of his/her views about cultural diversity and/or prejudices. Therefore, future applications of the EXCELL model require systematic assessment of such factors that may inhibit or facilitate the delivery of training in intercultural competencies.

In future applications of EXCELL, one may need to re‐consider whether it is appropriate to include the Aboriginal scenario, alongside scenarios involving Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) groups. Indeed, it may be more appropriate to deliver teaching and learning activities with respect to Indigenous issues and the development of competencies for communicating with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders separately. Ranzijn, McConnochie, Day and Wharton (Citation2008) and Garvey (Citation2007) argue that the delivery of curricula on issues impacting upon Indigenous communities and the development of cultural competencies should be embedded throughout undergraduate and post‐graduate training in psychology. They further suggest that a tokenistic approach, or approaches that label the study of the culture and issues impacting upon Aboriginal people, as Indigenous psychology, can be counterproductive in that they can impart a Western view and result in continued ‘cultural colonisation’ (Ranzijn et al., Citation2008, p. 138). For further discussion on cultural competency development and emerging models for Indigenous education in psychology and higher education, see Dudgeon, Darlaston‐Jones, and Clark (Citation2011).

The quantitative data indicated that students reported gaining some skills in intercultural communication following completion of the introductory psychology unit, although these gains were modest. It may be that students in the Australian Capital Territory already have well‐developed intercultural competencies because of their educational experiences prior to entering University. For example, it is common in the ACT for students to attend school alongside children of Diplomats from a variety of countries. As emphasised in Wilson‐Doenges and Gurung (2013), it is imperative that baseline data are collected prior to the implementation of teaching and learning interventions.

Littlefield (Citation2012) argues that the future training of undergraduate psychology students needs to include an emphasis on application of skills learnt in psychology curricula. In this pilot study, the majority of students responded positively to the open‐ended question pertaining to the application of their training in intercultural skills. Students reported that they had gained knowledge, respect, and sensitivity towards cultural differences and indicated that the intercultural communication skills developed within the introductory unit would increase their scope and breadth of professional practice.

Several limitations impact on the reliability and generalisability of the results reported here. First, without baseline data pertaining to levels of cultural knowledge and intercultural communication skills, we cannot determine if our teaching activities have led to improvements in either knowledge or competencies. Similarly, without an adequate control group, we cannot determine whether self‐reported improvements in knowledge and competencies described occurred as a result of participating in either of the activities. Further, we have no way of identifying whether it was the first activity, or the second, or other aspects of the unit, that potentially accounted for the outcomes reported. For instance, the cultural learning items were framed with reference to the entire unit, so it is not possible to determine the extent to which such cross‐cultural competency changes derived from the particular activities described in this article.

Furthermore, it could be argued that the alliance‐building activity may have resulted in the improvement in a sense of community with fellow students from diverse cultural backgrounds, whereas the cultural mapping training was directly linked with the reported increases in skills pertaining to effectively communicating across cultural boundaries. However, it is important to highlight Garvey's (Citation2007) point that without critical self‐reflection of one's own connection with culture, the development of intercultural competencies will be difficult. It is likely, therefore, that development of intercultural competencies will be enhanced by both the intercultural competence activities described in this study, as well as the additional activities. As Owens and White (Citation2013) concluded in their study of five approaches to reducing plagiarism, all approaches likely contributed to the reduction. Thus, further empirical work is required to determine the role of alliance building and cultural mapping and other activities in developing intercultural competencies for communicating within and across cultures.

Further empirical work is also required to determine whether application of the EXCELL model addresses the learning outcomes relevant to the proposed graduate attribute of global citizenship. Additional work may also be required to define and operationalise the elements that comprise the construct of intercultural competence, and determine how this is different from the concept of ‘global citizenship’. The approaches advocated by Dunn et al. (Citation2013), Karantzas et al. (Citation2013), and Morris et al. (Citation2013) should also be considered when designing further evaluations of teaching and learning activities involving EXCELL and other methods to improve intercultural competencies.

Despite the limitations, the observations made and implications drawn deserve further application and investigation. Face‐to‐face and online activities involving critical self‐reflection and explicit mapping of intercultural communication skills can facilitate development of intercultural competencies at first year level; these types of novel learning activities can also be adapted in subsequent years of the undergraduate psychology curriculum.

Specific recommendations for future curriculum innovations throughout the undergraduate psychology programme include linking assessment tasks to demonstrating knowledge of the challenges in communicating with members from CALD communities, and (with caveats noted earlier) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders. Worthy areas of investigation would involve the collection of data pertaining to undergraduate students' knowledge of issues impacting CALD communities and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Scholars in psychology may then be more informed to develop relevant theory upon which appropriate (and less ethnocentric) approaches to the delivery of curricula on culture can be developed and monitored for effectiveness. Ideally (although ambitious), methods that aim to assess long‐term impact, following curricula changes, on improvements in outcome for underserved communities would also be included.

Within undergraduate psychology, there are a number of novel ways in which educators could embed cultural knowledge. Approaches include the delivery of specialised units, or alternatively curricula could be embedded within existing core units such as social psychology or research methods. Within research methods, students could be encouraged to reflect on the appropriateness of methods in particular contexts. For example, there is evidence to support improved health outcomes for Indigenous populations, through the application of community‐based participatory action research models, incorporating Indigenous governance of research and the use of qualitative methods (Miller, Knott, Wilson, & Roder, Citation2012). Similarly, further explicit teaching, such as use of the EXCELL programme and adopting scenarios relevant to effective communication within elective unit areas (e.g., health and or community psychology), may also aid students in developing the capacity to respond to the issues affecting underserved populations.

Conclusion

Currently, in Australia, the UK and USA, there is considerable discussion about the aims of undergraduate psychology education. We argue that cultural competence should be one of those aims, and we have provided some preliminary evidence that practical skill‐based activities can be successfully integrated with core curricula in an introductory psychology unit. In our example, we showed how local‐born, immigrant, and international students can engage in alliance‐building activities. Additionally, we showed how explicit teaching of intercultural skills can be facilitated with a cultural mapping tutorial activity. We recommend further investigation to understand how best to engage students in the sharing and development of knowledge with respect to cultural diversity. We believe that approaches that incorporate practical skills, particularly those pertaining to reflection and communication within and across cultures, could help to ensure that our graduates are prepared, and indeed are competitive, relative to other health care professionals when gaining employment following completion of a three year undergraduate degree in psychology.

Acknowledgements

Support for this publication has been provided by the University of Canberra, Faculty of Health Research Support Grant 2012 and the Australian Government Office for Learning and Teaching. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the Office for Learning and Teaching.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychological Society (2006). APA Guidelines for the undergraduate psychology major. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/ed/precollege/about/psymajor‐guidelines.pdf

- Attride‐stirling, J. (2001). Thematic networks: An analytical tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 1, 385–405.

- Australian Psychology Accreditation Council. (2010). Rules for accreditation and accreditation standards for psychology courses. Retrieved from http://www.psychologycouncil.org.au/Assets/Files/APAC_Rules_for_Accreditation_&_Accreditation_Standards_for_Psychology_Courses_Ver_10_June_2010.pdf

- Chester, A., Xenos, S., Burton, L. J., & Elgar, K. (2013). Peer mentoring: Supporting successful transition for first year undergraduate psychology students. Australian Journal of Psychology, 65(1), 30–37.

- Cranney, J., Botwood, J., & Morris, S. (2012). National standards for psychological literacy and global citizenship: Outcomes of undergraduate psychology education. Retrieved from http://www.psychologicalliteracy.com

- Cranney, J. , & Dunn, D. S. (Eds.) (2011). The psychologically literate citizen: Foundations and global perspectives. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Cranney, J., Turnbull, C., Provost, S. C., Martin, F., Katsikitis, M., White, F. A., … Varcin, K. J. (2009). Graduate attributes of the 4‐year Australian undergraduate psychology program. Australian Psychologist, 44, 253–262. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00050060903037268

- Crowe, S. (2012). Psychology 2020: The 2011–2012 presidential initiative on the future of psychological science in Australia. Melbourne: Australian Psychological Society. Retrieved from http://www.psychology.org.au/Assets/Files/2012_APS_PIFOPS_WEB.pdf

- Dudgeon, P., Darlaston‐jones, D., & Clark, Y. (2011). Changing the lens: Indigenous perspectives on psychological literacy. In J. Cranney & D. S. Dunn (Eds.), The psychologically literate citizen: Foundations and global perspectives (pp. 72–90). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Dunn, D. S., Saville, B. K., Baker, S. C., & Marek, P. (2013). Evidence‐based teaching: Tools and techniques that promote learning in the psychology classroom. Australian Journal of Psychology, 65(1), 5–13.

- Garvey, D. (2007). Indigenous identity in contemporary psychology: Dilemmas, development and directions. Melbourne: Thomson Learning.

- Glaser, B. (1992). Basics of grounded theory analysis. Mill Valley: Sociology Press.

- Halpern, D. F. (2010). Undergraduate education in psychology: A blueprint for the future of the discipline. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Ho, E. S., Holmes, P., & Cooper, J. (2004). Review and devaluation of international literature on managing cultural diversity in the classroom. Wellington: Ministry of Education, New Zealand.

- Karantzas, G. C., Avery, M. R., Macfarlane, S., Mussap, A., Tooley, G., Hazelwood, Z., & Fitness, J. (2013). Enhancing critical analysis and problem‐solving skills in undergraduate psychology: An evaluation of a collaborative learning and problem‐based learning approach. Australian Journal of Psychology, 65(1), 38–45.

- Leong, F. T. L., Leach, M. M., & Malikiosi‐loizos, M. (2012). Internationalizing the psychology curriculum in the United States: Meeting the challenges and opportunities of a global era. In F. T. L. Leong , W. E. Pickren , M. M. Leach , & A. J. Marsella (Eds.), Internationalizing the psychology curriculum in the United States (pp. 1–9). New York: Springer.

- Littlefield, L. (2012). Executive director's report: New APS model of psychology education under consideration. InPsych: The Bulletin of the Australian Psychological Society. Retrieved from http://www.psychology.org.au/psych/2012/august/ed/

- Macnab, B. R., & Worthley, R. (2012). Individual characteristics as predictors of cultural intelligence development: The relevance of self‐efficacy. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 36, 62–71. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.12.001

- Mak, A., & Kennedy, M. (2012). Internationalising the student experience: Preparing instructors to embed intercultural skills in the curriculum. Innovative Higher Education, 37, 323–334. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755‐012‐9213‐4. Retrieved from http://www.springerlink.com/openurl.asp?genre=article&id=doi:10.1007/s10755‐012‐9213‐4

- Mak, A. S. (2012). Embedding intercultural competence development in the psychology curriculum. Psychology Learning and Teaching, 11, 365–369. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.2304/plat.2012.11.3.365

- Mak, A. S., & Buckingham, K. (2007). Beyond communication courses: Are there benefits in adding skills‐based EXCELL™ sociocultural training? International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 31(3), 277–291. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2006.02.002

- Mak, A. S., Westwood, M. J., Barker, M., & Ishiyama, F. I. (1998). Developing sociocultural competencies for success among international students: The EXCELL programme. Journal of International Education, 9, 33–38.

- Mak, A. S., Westwood, M. J., Ishiyama, F. I., & Barker, M. C. (1999). Optimising conditions for learning sociocultural competencies for success. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 23, 77–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0147‐1767(98)00026‐1

- Miller, J., Knott, V., Wilson, C., & Roder, D. (2012). A review of community engagement in cancer control studies among Indigenous people of Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the US. European Journal of Cancer Care, 21(3), 283–295. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365‐2354.2012.01325.x

- Morris, S., Cranney, J., Jeong, J. M., & Mellish, L. (2013). Developing psychological literacy: Student perceptions of graduate attributes. Australian Journal of Psychology, 65(1), 54–62.

- Owens, C., & White, F. A. (2013). A five‐year systematic strategy to reduce plagiarism amongst first‐year psychology university students. Australian Journal of Psychology, 65(1), 14–21.

- Ranzijn, R., Mcconnochie, K., Day, A., & Wharton, W. M. (2008). Towards cultural competence: Australian indigenous content in undergraduate psychology. Australian Psychology, 43(2), 132–139.

- Stoloff, M. L., Mccarthy, M., Keller, L., Varfolomeeva, V., Lynch, J., Makara, K., … Smiley, W. (2010). The undergraduate psychology major: An examination of structure and sequence. Teaching of Psychology, 37, 4–15. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00986280903426274

- Trapp, A., Banister, P., Ellis, J., Latto, R., Miell, D., & Upton, D. (2011). The future of undergraduate psychology in the United Kingdom. York: Higher Education Academy Network, University of York.

- Wadkins, T. A., & Miller, R. L. (2011). Structuring the capstone experience in psychology. In R. L. Miller , E. Amsel , B. M. Kowalewsdi , B. Beins , K. D. Keith , & B. Peden (Eds.), Promoting student engagement, volume 1: Programs, techniques and opportunities (pp. 95–102). Syracuse, NY: Society for the Teaching of Psychology. Retrieved from http://www.teachpsych.com/ebooks/pse2011/vol1/volume1.pdf

- Westwood, M. J., Mak, A. S., Barker, M., & Ishiyama, I. (2000). Group procedures and applications for developing sociocultural competencies among immigrants. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 22, 317–330.