Abstract

The Levels of Emotional Awareness Scale (LEAS) is a performance‐based measure of emotional awareness. This study examined whether the LEAS is suitable to be administered orally by administering two half‐forms of the LEAS to literate participants; one orally and one in written format. In doing so, this study raised questions regarding the internal reliability and statistical equivalence of the LEAS half‐forms. Despite this, results showed no significant difference between oral and written administration. Further, the correlation between scores obtained through oral and written administration was no less than the correlation between the LEAS‐A and LEAS‐B half‐forms. Together, these results suggest that, in circumstances where administering the written format of the LEAS is not possible, this scale may be administered orally.

Emotional awareness is the ability to attend to, recognise, and label emotions in oneself and others (Lane & Schwartz, Citation1987; Lumley, Gustavson, Partridge, & Labouvie‐Vief, Citation2005). Poor emotional awareness has been found in a range of psychopathologies, including borderline personality disorder (Levine, Marziali, & Hood, Citation1997), generalised anxiety disorder (Novick‐Kline, Turk, Mennin, Hoyt, & Gallagher, Citation2005) and depression (Pasquier & Pedinielli, Citation2010). Emotional awareness is essential because it allows an individual to access important, adaptive information inherent in emotions (Gohm & Clore, Citation2002a), such as knowledge about values, goals, or needs (Paivio & Greenberg, Citation2001). This, in turn, is likely to facilitate more effective emotion processing and regulation (Berkowitz, Citation1990; Greenberg & Pascual‐Leone, Citation2006; Roberton, Daffern, & Bucks, Citation2012).

Levels of emotional awareness

Lane and colleagues have written extensively on the theory and measurement of emotional awareness (Bajgar, Ciarrochi, Lane, & Deane, Citation2005; Lane, Citation2000; Lane, Quinlan, Schwartz, Walker, & Zeitlin, Citation1990; Lane & Schwartz, Citation1987; Lane et al., Citation1996; Lane, Sechrest, & Riedel, Citation1998; Subic‐Wrana, Beutel, Garfield, & Lane, Citation2011). In their seminal article, Lane and Schwartz (Citation1987) describe emotional awareness as a type of cognitive processing. They suggest that as an individual's level of emotional awareness increases, new ways of representing emotion are developed that are more flexible and can capture more information. They describe the formation of emotional awareness as a process where awareness moves from being relatively global and lacking in differentiation to increasing in differentiation and articulation. Their levels of emotional awareness (LEA) model involves five progressive, hierarchically organised levels of emotional awareness (Lane et al., Citation1990; Lane & Schwartz, Citation1987). The first level of emotional awareness is called sensorimotor reflexive. It involves an awareness of bodily sensations, experienced as global arousal involving the whole person. A person with sensorimotor reflexive awareness, when describing how they are feeling, might state that they are ‘sick’ or ‘exhausted’ (Lane et al., Citation1990). The second level is termed sensorimotor enactive. It involves a positively or negatively balanced bodily sensation and/or an action tendency aimed at maximising pleasure and minimising distress. A person with sensorimotor enactive awareness would typically describe action tendencies, such as ‘I feel like crying’, or global hedonic states, such as ‘I feel bad’ (Lane et al., Citation1990). The third level is called preoperational. It involves an awareness of individual feelings, including a mental representation of the emotion. At this level, emotions are experienced psychologically as well as somatically. A person at this level might describe themselves as ‘sad’ or ‘afraid’, but is not yet aware of experiencing blends of emotions (Lane et al., Citation1990). The fourth level is described as concrete operational. At this level, an individual is aware that they have the capacity to experience a number of different emotions within a single emotional reaction, bringing a new ability to perceive complexity and unity at the same time (Subic‐Wrana, Beutel et al., Citation2011). A person with concrete operational awareness might describe themselves as ‘both sad and afraid’ (Lane et al., Citation1990). Finally, the fifth level is termed formal operational. It involves differentiation between an individual's experiences and the experiences of those around them, allowing an individual to put oneself into a feeling state previously not experienced by the self (Subic‐Wrana, Beutel et al., Citation2011). A person with this level of awareness might describe themselves as ‘sad, afraid, and hopeless’, while recognising that the person they are with may be feeling ‘sad and worried’ (Lane et al., Citation1990).

Thus, the LEA model follows a sequence of progressive differentiation and integration (Lane & Schwartz, Citation1987). As people move from one level of emotional awareness to the next, they are, arguably, better equipped to process and regulate their emotional responses in a manner that is adaptive. Research has found that increased emotional awareness is related to a lower level of experienced negative emotion (Berenbaum & Irvin, Citation1996), increased ability to tolerate and contain negative‐emotion states (Wilkowski & Robinson, Citation2008), and increased engagement in adaptive coping styles (Gohm & Clore, Citation2002b).

Levels of Emotional Awareness Scale (LEAS)

In order to measure emotional awareness as set out in the LEA model, Lane et al. (Citation1990) designed the LEAS. The LEAS is a performance‐based measure that uses objective ratings of material produced by the individual, setting it apart from self‐report measures of emotional awareness and its related constructs, such as the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS‐20; Bagby, Parker, & Taylor, Citation1994); Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS, Gratz & Roemer, Citation2004); and Trait Meta‐Mood Scale (TMMS, Salovey, Mayer, Goldman, Turvey, & Palfai, Citation1995). The LEAS consists of 20 evocative, interpersonal scenarios. While each scenario is designed to elicit anger, happiness, sadness, or fear, the scenarios also provide the opportunity to describe blends of emotions, as well as ambivalence. Each scenario contains two components: a self component, where participants are required to describe how they would feel, and an other component, where they describe how the other person in the scenario would feel. Responses are scored from 0 to 4 on the basis of the level of emotional awareness displayed, in accordance with levels 1–4 of the LEA model. These ratings are given irrespective of whether or not the emotional response is considered appropriate for that scenario. A total score for the scenario is also assigned; equal to the higher score obtained for either the self or other component. When the self and other components each receive the maximum score of 4 and are sufficiently differentiated from each other, a total score of 5 is given, to reflect the fifth level of the LEA model. These scores are averaged to produce LEAS subscale scores for self (LEAS‐S), other (LEAS‐O), and total (LEAS‐T).

Psychometric evidence regarding the English version of the LEAS suggests the scale has good reliability. In a sample of 371 community participants, Lane et al. (Citation1996) found that internal consistency was α = 0.84, 0.83, and 0.88 for LEAS‐S, LEAS‐O, LEAS‐T, respectively (cf. Lane, Kivley, Dubois, Shamasundara, & Schwartz, Citation1995; Lane et al., Citation1990; Lindsay & Ciarrochi, Citation2009), reflecting good internal consistency. Using the stringent scoring manual, interrater reliability also tends to be high. Lane et al. (Citation1996) found that interrater reliability was excellent, r = 0.98, 0.91, and 0.92, for LEAS‐S, LEAS‐O, LEAS‐T, respectively (cf. Lane et al., Citation1995; Lane et al., Citation1990; Lindsay & Ciarrochi, Citation2009). Only a single study has examined the test‐retest reliability of the LEAS, which was found to be r = 0.67 over a 2‐week period (Lane & Pollerman, Citation2002).

Convergent validity has been established. Lane et al. (Citation1990) found that the LEAS was positively and significantly correlated with two measures of cognitive‐developmental complexity: the Washington University Sentence Completion Test of Ego Development, r = 0.40; and the Parental Descriptions Scale, which measures participants' developmental level of conceptual complexity, r = 0.35. This provides evidence that the LEAS measures increasing conceptual complexity with regards to emotions. Scores on the LEAS have also been associated with both verbal and non‐verbal emotion recognition tasks (Lane, Sechrest, Riedel, Shapiro, & Kaszniak, Citation2000), as well as neural correlates of emotional arousal (Lane, Reiman et al., Citation1998).

Finally, there is evidence of divergent validity. In one study, LEAS scores did not correlate significantly with the number of words used in the LEAS responses (Lane et al., Citation1990), offering evidence that the LEAS measures more than verbal productivity. Although one study has found a moderate correlation between the LEAS and TAS‐20 scores (Waller & Scheidt, Citation2004), most studies have found only weak or non‐significant correlations between these two measures (Lane, Sechrest et al., Citation1998; Lumley et al., Citation2005). As such, it has been suggested that the LEAS measures a construct that is distinct from alexithymia (Lumley et al., Citation2005).

While there is only one form of the full, 20‐item test, the test manual also includes two half‐forms (Lane, Citation1991). Each of these half‐forms (LEAS‐A and LEAS‐B) comprise 10 scenarios taken from the original 20, divided such that each form is designed to be of equal complexity and eliciting a range of emotions. These half‐forms are described by the scale's author as statistically parallel (Subic‐Wrana, Beutel et al., Citation2011; Subic‐Wrana, Bruder, Thomas, Lane, & Kohle, Citation2005).

Utility as a clinical measure

The LEAS has become increasingly popular in emotion regulation research. Since 2010, it has been used in studies on attachment (Subic‐Wrana, Beetz, Wiltink, & Beutel, Citation2011), risk‐taking (Brejard, Pasquier, Bonnet, & Pedinielli, Citation2011), gambling (Pascual‐Leone, Gomes, Orr, Kaploun, & Abeare, Citation2011), alcohol and substance dependence (Bochand & Nandrino, Citation2010; Carton et al., Citation2010), anorexia nervosa (Parling, Mortazavi, & Ghaderi, Citation2010), mood disorders (Pasquier & Pedinielli, Citation2010), somatoform disorders (Subic‐Wrana, Beutel, Knebel, & Lane, Citation2010), hypertension (Consoli et al., Citation2010), and spinal cord injury (Deady, North, Allan, Smith, & O'Carroll, Citation2010).

Several studies have also been undertaken using the LEAS half‐forms, either using one half‐form as a single measure of emotional awareness (Barrett, Lane, Sechrest, & Schwartz, Citation2000; Subic‐Wrana et al., Citation2010), or using both to measure change in emotional awareness over time (Subic‐Wrana et al., Citation2005). Furthermore, in a theoretical article exploring the utility of the LEAS as a tool for measuring emotion‐centred structural change, Subic‐Wrana, Beutel et al. (Citation2011) suggest that the half‐forms of the scale provide a clinically useful pre‐ and post‐measure of emotional awareness.

To extend research on emotional awareness to more diverse populations, and in order to use the measure regularly as a clinical tool in a wide variety of settings, it is important that the LEAS is accessible to individuals who are illiterate. In many settings, it is common for clinicians to read scales aloud to clients who have difficulty reading and/or writing. While some research has found comparable results between written and oral responses for self‐report scales generally (Walters & Merrell, Citation1995; Witherspoon et al., Citation1997), no psychometric data have yet been published on the oral delivery of the LEAS. Given that the LEAS is a performance‐based measure that requires the individual to share information about typically private emotion experiences, it is important to establish that asking participants to share their answers orally yields the same results as asking them to write their answers.

Thus, the aim of this study was to determine whether the LEAS yields comparable results when delivered orally as when completed in written format. Because past research has found comparable reports between written and oral responses for other self‐report scales, it was expected that the scores obtained using different modes of administration would be strongly correlated. It was also expected that there would be no significant differences between these scores.

Method

Participants

Approval to conduct this research was provided by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee. Participants (N = 69) were recruited in the community and from a pool of 1st year psychology students at Monash University. Approximately half were female (N = 38; 52%). Participants had a mean age of 31.4 (standard deviation (SD) = 13.0) and had undergone a mean of 16.1 (SD = 2.6) years of education. All participants spoke English as a primary language.

Measures

The LEAS was administered as part of a battery of tests being used in a larger study on emotions and offending. Given that this study aimed to determine whether the LEAS yields comparable results across two methods of administration, the two half‐forms (LEAS‐A and LEAS‐B) of the scale were used (Lane, Citation1991), with one minor change from the original format. In the original LEAS, each scenario is presented followed by the questions ‘How would you feel? How would the other person feel?’ In this study, these questions were given separately. The scenario was presented first, immediately followed by the self component (‘How would you feel?’). Space (written) or time (oral) was then given for the participant to answer before the other component was presented (‘How would the other person feel?’). This was done so as to prevent people from obtaining low ‘other’ scores simply from forgetting to answer the second part of the question.

Procedure

After obtaining informed consent, participants were randomly allocated to one of four groups. All participants completed a demographic questionnaire followed by separate presentations of the LEAS‐A and LEAS‐B, one oral and one written. The groups differed according to a 2 × 2 manipulation whereby the mode of administration for LEAS‐A and LEAS‐B was changed (oral or written), as was the order of presentation. This study design was used to limit practice effects expected from being presented with the same scenarios twice.

For the oral administration of the LEAS, an audio recording of each question was played to participants so that there was no difference in emphasis, tone, or volume of the presented scenarios. Participants responded orally to a researcher who recorded their answer verbatim. Answers for both the written and oral administrations were scored per the LEAS protocol by one researcher, a doctoral student with qualifications in psychology and previous experience scoring the LEAS. A second doctoral student with qualifications in psychology was trained in the LEAS and scored a subset of 14 (20% of the total sample size) oral and written answers, in order to establish interrater reliability.

Statistical analyses

Total scores for the LEAS‐A (oral), LEAS‐A (written), LEAS‐B (oral), and LEAS‐B (written) were calculated. All distributions were considered to be sufficiently normal as skewness and kurtosis were within |3| (Howitt & Camer, Citation2005; Micceri, Citation1989; Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2007).

Within‐group analysis of variance and t‐tests were used to investigate differences between the scales with regards to mode of delivery, type of half‐form, and order of presentation. Pearson correlations were used to explore the relationships between the scales. Two‐tailed significance testing, and an alpha level of 0.05, was used for all analyses (Howell, Citation2002). All within‐subjects effect sizes were corrected for dependence between means (Morris & DeShon, Citation2002). Data were analysed using PASW Statistics for Windows (version 18.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Cronbach's alpha revealed a wide range in the level of internal reliability for the oral and written administration of LEAS‐A and LEAS‐B (see Table ). Alpha scores for several subscales were unacceptable, particularly for the oral administration of LEAS‐B. There was no one item that, when removed, improved the reliability of this subscale to an acceptable point (i.e. ≥0.70). Given the questionable internal reliability of several self and other subscales, only the total scales, which demonstrated good internal reliability, were used in the remaining analysis. Intraclass correlations revealed excellent interrater reliability for both the oral and written administrations across self, other, and total scores: intraclass correlation coefficients ranged from 0.98 to 0.99, (95% confidence intervals 0.93–0.99).

Table 1. Reliability of the LEAS, according to group

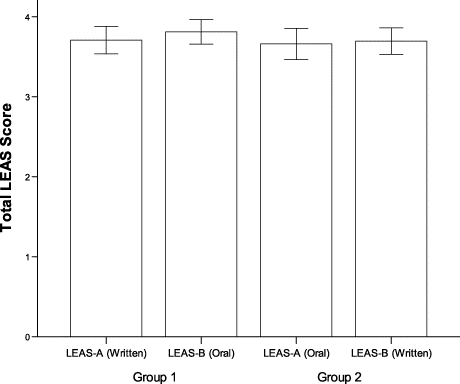

There was no effect of order of presentation on LEAS scores, F(2,64) = 1.33, p = .272. Thus, data were collapsed across order of presentation such that two counterbalanced groups were formed: Group 1 (n = 31) completed the LEAS‐A (written) and the LEAS‐B (oral), while Group 2 (n = 38) completed the LEAS‐A (oral) and the LEAS‐B (written). There was no significant difference between groups either in age, t(68) = 1.27, p = .210, d = 0.45, or years of education, t(68) = 1.81, p = .075, d = 0.31, nor in the proportion of males and females, χ2(1, N = 69) = 0.69, p = .405. LEAS‐A and LEAS‐B scores for each group are presented in Fig. 1.

There was no significant difference between scores when the LEAS was delivered orally and when completed in written format, for either Group 1, t(30) = 1.55, p = .133, d = 0.28, or Group 2, t(37) = 0.57, p = .571, d = −0.10. Participants' scores from the oral administration of the LEAS were strongly correlated with their scores obtained from the LEAS in written format, for both Group 1, r = 0.67, p < .001, and Group 2, r = 0.76, p < .001.

Comparing LEAS‐A and LEAS‐B across the entire sample, no significant difference was found between half‐forms LEAS‐A and LEAS‐B, t(68) = 1.44, p = .155, d = −0.18, and there was a strong, significant correlation between LEAS‐A and LEAS‐B, r = 0.73, p < .001.

With regards to the association between method of administration and other relevant sociodemographic participant information, there were no differences between women, M(oral) = 3.80, M(written) = 3.74; and men, M(oral) = 3.66, M(written) = 3.66, across either method of administration: written, t(68) = 0.73, p = .470, d = 0.17; oral, t(68) = 1.07, p = .291, d = 0.26. Years of education was weakly positively correlated with both oral, r = 0.24, p = .050, and written, r = 0.27, p = .024, LEAS scores; albeit for oral, this was only at strong trend levels. Age was weakly negatively correlated with both the written, r = −0.16, p = .189, and oral administration, r = −0.22, p = .070, but neither was significant. These correlations mean that as little as 2.5% and no more than 7.3% of variance in LEAS scores is explained by age or education.

Discussion

As expected, this study found no significant differences between participants' scores on the oral and written administration of the LEAS.Footnote1 Furthermore, this study found significant, positive correlations between scores on the written and oral versions, suggesting that oral and written delivery of the LEAS offer comparable results. However, given that a correlation of r = 0.80 is often identified as an acceptable correlation for equivalent forms (Waltz, Strickland, & Lenz, Citation2010), these correlations were not as strong as would be necessary to consider oral administration of the scale equivalent to written administration. That is, scores obtained using one administration format should not be directly compared with scores obtained using the other.

This study also provided evidence that the LEAS may be administered orally. There was no significant difference between men and women with either method of administration, nor was the relationship between LEAS scores and age significant for either method. When the LEAS was presented in written format, level of education was positively correlated with the level of emotional awareness, as might be expected given that scores on the LEAS are associated with cognitive‐developmental measures (Lane et al., Citation1990). However, when the LEAS was presented in oral format, this correlation was of a similar magnitude, but only approached significance. Two points suggest that this is not cause for concern: The first is that the magnitude of the effects is not dissimilar (.24 and 27); the second that both effects show that only a small proportion of the variance in LEAS scores is due to education. Taken together, the evidence suggests that the LEAS, whether administered orally or in writing, is suitable for use with all ages and education levels, and in men and women.

While this study provided evidence for the use of the LEAS in written format, it also brought attention to two aspects of the LEAS half‐forms that require further consideration: the internal reliability of the scales and the statistical equivalence of the two half‐forms, LEAS‐A and LEAS‐B. Each of these will be discussed in turn.

Internal reliability of the LEAS half‐forms

The internal reliability of the half‐forms of the LEAS presented orally and in written format varied considerably. Alpha values ranged from α = 0.36 for the other subscale of LEAS‐B when presented orally to α = 0.84 for the other subscale of LEAS‐A, also when presented orally, although most variants achieved internal reliability scores above 0.60. It is unclear why the reliability of the LEAS‐B other subscale was so low when presented orally while the reliability of the LEAS‐A other subscale was so high when presented orally, but these results suggest that the other scale is generally less reliable than the self and total scales. A number of prior studies have only reported the reliability of the total scale (Lane et al., Citation1990; Lindsay & Ciarrochi, Citation2009). It is therefore difficult to ascertain whether these findings reflect poor internal consistency of the scale or idiosyncratic features of the participants. It should be noted, however, that interrater reliability for both the oral and written administrations of the scale were excellent across all subscales. Idiosyncratic scoring is therefore unlikely to have contributed to the variable internal reliability scores.

One reason why the other scale may be less reliable is that this scale also requires participants to be willing to examine the scenario from a second perspective. Should someone be unwilling to guess another's emotions (e.g., ‘I can't say how my friend would feel’), this would result in an errant low score from someone who has otherwise demonstrated good emotional awareness. If this were the case, to some degree, the other scale would measure an individual's willingness to guess another person's emotion as well as their general level of emotional awareness. However, while this may explain reduced internal reliability for the other subscale, it fails to account for differences in reliability across administration modes.

Regardless of the contributing factor to individual subscales' low reliability, the total scales demonstrated acceptable internal reliability. It is therefore clear that when using the LEAS to determine a person's level of emotional awareness, it is psychometrically advantageous to use the total score. The total scale allows the individual two opportunities to display their emotional awareness by considering both the self and other scores within each scenario. As such, it is likely to be a more reliable indicator of an individual's overall level of emotional awareness. This will be particularly true if administering a half‐form of the LEAS, which is necessarily less reliable than administering the full 20 scenarios, given that internal consistency is partly dependent on the number of items (Schmitt, Citation1996). While the total score for each LEAS half‐form may be used with some confidence regardless of method of administration, scores from the longer scale will likely provide a more reliable indicator of an individual's level of emotional awareness. Therefore, if assessment demands allow, the 20‐item form is preferred, but if time is constrained, or retesting is needed, the half‐forms have adequate internal consistency.

Statistical equivalence of the LEAS half‐forms

The two half‐forms of the measure (LEAS‐A and LEAS‐B) were strongly correlated, at 0.70. However, this was a little lower than would be ideal for parallel half‐forms (Waltz et al., Citation2010), and suggests that the lower than ideal correlations between modes of administration may reflect slight differences in the parallel forms proposed in the test manual, rather than genuine differences in the degree to which individuals are able to describe emotions across written and oral modalities. Although the LEAS half‐forms have been described by the scale author as ‘two statistically parallel half‐forms’ (Subic‐Wrana, Beutel et al., Citation2011, p. 92) and have been used as such (e.g. Subic‐Wrana et al., Citation2005), there are insufficient published psychometric data confirming their equivalence. Given the variable reliabilities across subscales and the moderate correlations between half‐forms obtained in the present study, further examination of these half‐forms is warranted.

It may be that the development of equivalent half‐forms requires the creation of new scenarios that are designed specifically to mimic the emotion evocation of a selection of current scenarios, rather than a particular allocation of existing scenarios. For example, an existing scenario such as ‘You and a friend agree to invest money together to begin a new business venture. Several days later you call the friend back only to learn that she/he changed her/his mind’ may be paired with a similar, but new, scenario, such as: ‘You and a friend plan an overseas holiday together. Several weeks later you call the friend only to learn that she/he no longer wants to go’. Developing paired scenarios that elicit similar emotional responses may allow for half‐forms that are more highly correlated.

Establishing the psychometric equivalence of the LEAS half‐forms will be particularly important given these half‐forms have already been used in research measuring changes in emotional awareness (Subic‐Wrana et al., Citation2005), and have been proposed as a clinically useful pre‐ and post‐measure of emotional awareness (Subic‐Wrana, Beutel et al., Citation2011). While the ability to evaluate change in emotional awareness is important for both research and clinical practice, use of the LEAS half‐forms for this purpose may currently be premature.

Conclusion

In sum, the primary aim of this study was to determine whether completing the LEAS orally yields comparable results to when it is administered in written format. To answer this question, two findings from this study must be considered. First, there was no significant difference between scores obtained through the oral and written administration of the LEAS. Second, the correlation between scores obtained through the oral and written administration of the LEAS was no less than the correlation between the LEAS‐A and LEAS‐B half‐forms. Together, these results suggest that, in circumstances where administering the written format of the LEAS is not possible, this scale may be administered orally with comparable results. Further, either of these methods of administration is suitable for participants of difference age, education, and gender.

Notes

1. The modest sample size raises the spectre of type‐II error. However, for the between‐group differences in order and written format at a 0.05 level with 80% power, one would need samples of 105 and 817 participants for Groups 1 and 2, respectively, thus confirming that it is unlikely there are marked differences in performance between oral and written forms.

References

- Bagby, R. M., Parker, J. D. A., & Taylor, G. J. (1994). The 20‐item Toronto Alexithymia Scale 1. Item selection and cross‐validation of the factor structure. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 38, 23–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0022‐3999(94)90005‐1

- Bajgar, J., Ciarrochi, J., Lane, R., & Deane, F. P. (2005). Development of the Levels of Emotional Awareness Scale for Children (LEAS‐C). British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 23, 569–586. doi:https://doi.org/10.1348/026151005X35417

- Barrett, L. F., Lane, R. D., Sechrest, L., & Schwartz, G. E. (2000). Sex differences in emotional awareness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(9), 1027–1035. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672002611001

- Berenbaum, H., & Irvin, S. (1996). Alexithymia, anger, and interpersonal behavior. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 65, 203–208.

- Berkowitz, L. (1990). On the formation and regulation of anger and aggression—a cognitive‐neoassociationistic analysis. American Psychologist, 45, 494–503. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037//0003‐066X.45.4.494

- Bochand, L., & Nandrino, J. L. (2010). Levels of emotional awareness in alcohol‐dependent patients and abstinent alcoholics. Encephale‐Revue De Psychiatrie Clinique Biologique Et Therapeutique, 36, 334–339. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.encep.2009.12.013

- Brejard, V., Pasquier, A., Bonnet, A., & Pedinielli, J. L. (2011). Comparative study of the subjective emotional experience among adolescents showing depressive symptoms associated or not with risk‐taking behavior. Encephale‐Revue De Psychiatrie Clinique Biologique Et Therapeutique, 37, 257–265. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.encep.2010.12.003

- Carton, S., Bayard, S., Paget, V., Jouanne, C., Varescon, I., Edel, Y., & Detilleux, M. (2010). Emotional awareness in substance‐dependent patients. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 66, 599–610. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20662

- Consoli, S. M., Lemogne, C., Roch, B., Laurent, S., Plouin, P. F., & Lane, R. D. (2010). Differences in emotion processing in patients with essential and secondary hypertension. American Journal of Hypertension, 23, 515–521. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/ajh.2010.9

- Deady, D. K., North, N. T., Allan, D., Smith, M. J. L., & O'carroll, R. E. (2010). Examining the effect of spinal cord injury on emotional awareness, expressivity and memory for emotional material. Psychology Health & Medicine, 15, 406–419. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2010.482138

- Gohm, C. L., & Clore, G. L. (2002a). Affect as information—An individual‐differences approach. In L. F. Barrett & P. Salovey (Eds.), Wisdom in feeling (pp. 89–113). New York: Guilford Press.

- Gohm, C. L., & Clore, G. L. (2002b). Four latent traits of emotional experience and their involvement in well‐being, coping, and attributional style. Cognition & Emotion, 16, 495–518. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930143000374

- Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26, 41–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94

- Greenberg, L. S., & Pascual‐leone, A. (2006). Emotion in psychotherapy: A practice‐friendly research review. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62, 611–630. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20252

- Howell, D. C. (2002). Statistical methods for psychology (5th ed.). Pacific Grove, CA: Duxbury/Thomson Learning.

- Howitt, D., & Camer, D. (2005). Introduction to statistics in psychology (3rd ed.). Harlow, England: Pearson.

- Lane, R. D. (1991). Leas scoring manual & glossary. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona.

- Lane, R. D. (2000). Levels of emotional awareness: Neurobiological, psychological and social perspectives. In R. Bar‐on & J. Parker (Eds.), Handbook of emotional intelligence: Theory, development, assessment and application at home, school, and in the workplace (pp. 171–191). San Francisco, CA: Jossey‐Bass.

- Lane, R. D., Kivley, L. S., Dubois, M. A., Shamasundara, P., & Schwartz, G. E. (1995). Levels of emotional awareness and the degree of right hemispheric dominance in the perception of facial emotion. Neuropsychologia, 33, 525–538. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0028‐3932(94)00131‐8

- Lane, R. D., & Pollerman, B. (2002). Complexity of emotion representations. In L. F. Barret & P. Salovey (Eds.), The wisdom in feeling (pp. 271–293). New York: Guildford.

- Lane, R. D., Quinlan, D. M., Schwartz, G. E., Walker, P. A., & Zeitlin, S. B. (1990). The Levels of Emotional Awareness Scale—a cognitive‐developmental measure of emotion. Journal of Personality Assessment, 55, 124–134. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5501&2_12

- Lane, R. D., Reiman, E. M., Axelrod, B., Yun, L. S., Holmes, A., & Schwartz, G. E. (1998). Neural correlates of levels of emotional awareness: Evidence of an interaction between emotion and attention in the anterior cingulate cortex. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 10, 525–535. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/089892998562924

- Lane, R. D., & Schwartz, G. E. (1987). Levels of emotional awareness—a cognitive‐developmental theory and its application to psychopathology. American Journal of Psychiatry, 144, 133–143.

- Lane, R. D., Sechrest, L., Reidel, R., Weldon, V., Kaszniak, A., & Schwartz, G. E. (1996). Impaired verbal and nonverbal emotion recognition in alexithymia. Psychosomatic Medicine, 58, 203–210.

- Lane, R. D., Sechrest, L., & Riedel, R. (1998). Sociodemographic correlates of alexithymia. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 39, 377–385. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010‐440X(98)90051‐7

- Lane, R. D., Sechrest, L., Riedel, R., Shapiro, D. E., & Kaszniak, A. W. (2000). Pervasive emotion recognition deficit common to alexithymia and the repressive coping style. Psychosomatic Medicine, 62, 492–501.

- Levine, D., Marziali, E., & Hood, J. (1997). Emotion processing in borderline personality disorders. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 185, 240–246. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053‐199704000‐00004

- Lindsay, J., & Ciarrochi, J. (2009). Substance abusers report being more alexithymic than others but do not show emotional processing deficits on a performance measure of alexithymia. Addiction Research Theory, 17, 315–321. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/16066350802472056

- Lumley, M. A., Gustavson, B. J., Partridge, R. T., & Labouvie‐vief, G. (2005). Assessing alexithymia and related emotional ability constructs using multiple methods: Interrelationships among measures. Emotion, 5, 329–342. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/1528‐3542.5.3.329

- Micceri, T. (1989). The unicorn, the normal curve, and other improbable creatures. Psychological Bulletin, 105, 156–166.

- Morris, S. B., & Deshon, R. P. (2002). Combining effect size estimates in meta‐analysis with repeated measures and independent‐groups designs. Psychological Methods, 7, 105–125. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037//1082‐989x.7.1.105

- Novick‐kline, P., Turk, C. L., Mennin, D. S., Hoyt, E. A., & Gallagher, C. L. (2005). Level of emotional awareness as a differentiating variable between individuals with and without generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 19, 557–572. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdix.2004.06.001

- Paivio, S. C., & Greenberg, L. S. (2001). Introduction: Treating emotion regulation problems. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 57, 153–155. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/1097‐4679(200102)57:2<153:AID‐JCLP2>3.0.CO;2‐F

- Parling, T., Mortazavi, M., & Ghaderi, A. (2010). Alexithymia and emotional awareness in anorexia nervosa: Time for a shift in the measurement of the concept? Eating Behaviors, 11, 205–210. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2010.04.001

- Pascual‐leone, A., Gomes, K., Orr, E. S., Kaploun, K. A., & Abeare, C. A. (2011). Affective and cognitive correlates of gambling behavior in university students. Journal of Gambling Studies, 27, 401–408. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899‐010‐9226‐9

- Pasquier, A., & Pedinielli, J. L. (2010). Exploratory study of relations between emotional awareness, social sharing of emotions, anxious and depression states. Encephale‐Revue De Psychiatrie Clinique Biologique Et Therapeutique, 36, D97–D104. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.encep.2009.01.007

- Roberton, T., Daffern, M., & Bucks, R. S. (2012). Emotion regulation and aggression. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17, 72–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2011.09.006

- Salovey, P., Mayer, J. D., Goldman, S. L., Turvey, C., & Palfai, T. P. (1995). Emotional attention, clarity, and repair: Exploring emotional intelligence using the Trait Meta‐Mood Scale. In J. W. Pennebaker (Ed.), Emotion, disclosure, & health (pp. 125–154). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Schmitt, N. (1996). Uses and abuses of coefficient alpha. Psychological Assessment, 8, 350–353. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/1040‐3590.8.4.350

- Subic‐wrana, C., Beetz, A., Wiltink, J., & Beutel, M. E. (2011). Unresolved attachment and remembered childhood trauma in patients undergoing psychosomatic inpatient treatment. Zeitschrift Fur Psychosomatische Medizin Und Psychotherapie, 57, 325–342.

- Subic‐wrana, C., Beutel, M. E., Garfield, D. A. S., & Lane, R. D. (2011). Levels of emotional awareness: A model for conceptualizing and measuring emotion‐centered structural change. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 92, 289–310. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745‐8315.2011.00392.x

- Subic‐wrana, C., Beutel, M. E., Knebel, A., & Lane, R. D. (2010). Theory of mind and emotional awareness deficits in patients with somatoform disorders. Psychosomatic Medicine, 72, 404–411. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181d35e83

- Subic‐wrana, C., Bruder, S., Thomas, W., Lane, R. D., & Kohle, K. (2005). Emotional awareness deficits in inpatients of a psychosomatic ward: A comparison of two different measures of alexithymia. Psychosomatic Medicine, 67, 483–489. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000160461.19239.13

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson/Allyn & Bacon.

- Waller, E., & Scheidt, C. E. (2004). Somatoform disorders as disorders of affect regulation—A study comparing the TAS‐20 with non‐self‐report measures of alexithymia. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 57, 239–247. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022‐3999(03)00613‐5

- Walters, A. S., & Merrell, K. W. (1995). Written versus oral‐administration of a social‐emotional self‐report test for children—does method of execution make a difference. Psychology in the Schools, 32, 186–189. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/1520‐6807(199507)32:3<186:aid‐pits2310320305>3.0.co;2‐w

- Waltz, C. F., Strickland, O., & Lenz, E. R. (2010). Measurement in nursing and health research (4th ed.). New York: Springer Publishing Company.

- Wilkowski, B. M., & Robinson, M. D. (2008). Clear heads are cool heads: Emotional clarity and the down‐regulation of antisocial affect. Cognition and Emotion, 22, 308–326. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930701394199

- Witherspoon, A. D., Hitson, D., Laprairie, C., Rendon, C., Thompson, S., & Long, C. K. (1997). Comparison of written and oral responses for scoring the environmental deprivation scale. Psychological Reports, 80, 847–850.