Abstract

Graduate employability has been the subject of little empirical research. There are a number of difficulties in defining and measuring graduate employability, which means that there is a paucity of research that looks at its predictors and outcomes. Previous work has proposed that emotional competence improves graduate employability, and this study further investigates this idea by examining the association between emotional self‐efficacy and employability. Also investigated is the association between employability and career satisfaction. Working graduates (N = 306) completed measures of emotional self‐efficacy, self‐perceived employability, and career satisfaction, and the data were analysed using structural equation modelling. We found emotional self‐efficacy to be an important predictor of graduate employability. Additionally, we found that graduate employability mediates the relationship between emotional self‐efficacy and career satisfaction. Some recommendations, in light of these findings, are discussed.

Graduate employability

Graduate employability has been discussed for some time, but there have been difficulties with its definition and conceptual clarity (e.g., Pegg, Waldock, Hendy‐Isaac, & Lawton, Citation2012; Sewell & Dacre Pool, Citation2010). The literature suggests that graduate employability is more than just getting a job or accumulating skills, and should not be confused with employment rates or seen as a measure of institutional success or otherwise (Harvey, Citation2003, Citation2005).

One of the more widely accepted definitions (Yorke, Citation2006) suggests that it is, ‘[a] set of achievements—skills, understandings and personal attributes—that makes graduates more likely to gain employment and be successful in their chosen occupations, which benefits themselves, the workforce, the community and the economy’ (p. 8). The concept of graduate employability shares much with the concept of graduate attributes, defined as ‘the qualities, skills and understandings a university community agrees its students should develop during their time with the institution. These attributes include, but go beyond, the disciplinary expertise or technical knowledge that has traditionally formed the core of most university courses’ (Bowden, Hart, King, Trigwell, & Watts, Citation2000, p. 1).

Measuring graduate employability is particularly problematic with the full‐time employment rates of graduates often used as easily measurable proxies for graduate employability (Bridgstock, Citation2009). However, measuring employability in this way is problematic, not least because the current state of the labour market will always impact on levels of graduate employment. Additionally, it is employers who ultimately convert graduate employability into employment, and there are a number of factors that mediate the employment process, including the type of higher education institution attended, mode and subject of study, age, ethnicity, gender, and social class (Harvey, Citation2001). As such, using employment rates as an ‘objective’ measure of graduate employability would appear to be deeply flawed. It could be that, as with many achievements valued by society, graduate employability is something that resists objective measurement (Yorke & Knight, Citation2006). As such, self‐evaluation is likely to be the most useful way of approaching this task.

Recent years have seen the emergence of models of graduate employability development (e.g., Dacre Pool & Sewell, Citation2007; Knight & Yorke, Citation2004), and some measures of self‐perceived employability are now available (e.g., Berntson & Marklund, Citation2007; Rothwell & Arnold, Citation2007). These help inform what these ‘skills, understandings and personal attributes’ might be, but there is still limited empirical research in this area, particularly in relation to the self‐perceived employability of graduates.

Much of the discussion surrounding graduate employability focuses on the skills and competencies that employers consider desirable in their graduate recruits, sometimes referred to as ‘generic’ or ‘transferable’ employability skills (Bridgstock, Citation2009). These include self‐management, team‐working, communication, and the ability to work under pressure (e.g., Lowden, Hall, Elliot, & Lewin, Citation2011). Researchers have highlighted the need for further empirical investigation of these skills and competencies as possible predictors of employability (Wittekind, Raeder, & Grote, Citation2010). Other researchers (Dacre Pool & Sewell, Citation2007; Jaeger, Citation2003; Liptak, Citation2005; Repetto Talavera & Pérez‐González, Citation2007; Vandervoort, Citation2006) have argued that emotional competence should also be studied as this may have a direct or indirect impact (via the generic skills mentioned above) on graduate employability.

Emotional intelligence (EI)

The construct of EI provides a scientific framework for the study of emotional competence (Mikolajczak, Petrides, Coumans, & Luminet, Citation2009). It has been conceptualised as an emotion‐related cognitive ability (Mayer & Salovey, Citation1997; Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, Citation2002) comprising a set of four emotion‐related skills that include the ability to perceive, use, understand, and manage emotion (the four‐branch model). EI has also been defined as a constellation of emotional self‐perceptions located at the lower levels of personality hierarchies (Petrides, Pita, & Kokkinaki, Citation2007). These two distinct perspectives are usually referred to as ‘ability EI’ and ‘trait EI’, respectively, with meta‐analytical studies finding a weak correlation between the two (Van Rooy, Viswesvaran, & Pluta, Citation2005). Different measurement methods are utilised dependent upon the EI perspective taken: ability EI uses performance‐based measures, and trait EI utilises self‐report methodology. There have been a number of studies that have examined work‐related outcomes in relation to a person's EI ability. These outcomes are likely to impact on graduate employability, and include enhanced work performance (O'Boyle, Humphrey, Pollack, Hawver, & Story, Citation2010), negotiation skills (Mueller & Curhan, Citation2006), effective leadership (Kerr, Garvin, Heaton, & Boyle, Citation2006), successful team‐working (Vitello‐Cicciu, Citation2001), and greater revenue generation and better customer retention in sales professionals (Kidwell, Hardesty, Murtha, & Sheng, Citation2011). Furthermore, there is now evidence directly linking emotional competence in undergraduate students with interview success, another important aspect of employability (Nelis et al., Citation2011).

However, whether or not people feel confident about, or motivated to use, their emotional knowledge and skills has received little empirical investigation.

Emotional self‐efficacy

One research area that helps address this issue is that of emotional self—efficacy (ESE). ESE has been suggested as an appropriate alternative label for trait EI (Petrides & Furnham, Citation2001; Petrides, Pérez‐González, & Furnham, Citation2007). However, Kirk, Schutte, and Hine (Citation2008, Kirk, Schutte, and Hine Citation2011) argue that although ESE may be an aspect of trait EI, the two are not identical. In support of this argument, recent studies have found only small to medium correlations between ESE subscales and trait EI subscales, as measured by the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (Petrides & Furnham, Citation2006) of between 0.15 and 0.62 (Dacre Pool & Qualter, Citation2012b). ESE is solely concerned with confidence in one's emotional competence as operationalised by the four‐branch ability model of EI (Mayer & Salovey, Citation1997), whereas trait EI encompasses other aspects of self‐perception and dispositions (Kirk et al., Citation2008). The concept of self‐efficacy is most often associated with the work of Bandura (Citation1997), with Mayer, Caruso, and Salovey (Citation1999) furthering this work by suggesting that people often act on what they believe about their abilities as opposed to their actual abilities, highlighting the importance of measuring ESE. Literature that looks at how people differ in their capability and skills does not fully explain why these individual differences may or may not be demonstrated in actual levels of performance. As such, it is possible that self‐efficacy is even more important than actual task‐related abilities and skills in explaining these individual differences in performance (Gundlach, Martinko, & Douglas, Citation2003).

In the case of EI, a person may have the ability to read emotions well in other people or to manage their own emotions, but they may decide not to use either of these abilities, possibly because they are not motivated to do so or because they lack self‐efficacy in this domain (Kirk et al., Citation2008; Qualter, Barlow, & Stylianou, Citation2011). People who believe that they have some control over their emotional competence are more successful in regulating their emotions than those who believe that this is something they cannot control effectively (Bandura, Caprara, Barbaranelli, Gerbino, & Pastorelli, Citation2003). Research in this new field of interest is limited, but recent work has found that ESE helps school children and university students manage the negative effects of anxiety in relation to mathematics testing (Galla & Wood, Citation2012; Tariq, Qualter, Roberts, Appleby, & Barnes, Citation2013), and predicts academic performance among boys (Qualter, Gardner, Pope, Hutchinson, & Whiteley, Citation2012).

It could be that ESE is also an important factor in relation to work‐related outcomes, and in particular graduate employability, but as yet this has not been investigated. Confirming the association between ESE and graduate employability is important because it would indicate that ESE is a potential contributor to employability, which itself predicts better health and well‐being (Berntson & Marklund, Citation2007). There is also evidence to suggest that ESE and EI can be improved through teaching interventions for undergraduate students (Dacre Pool & Qualter, Citation2012a), and is therefore something that universities can help students to develop.

Career satisfaction

Career satisfaction is not to be confused with job satisfaction, which is purely concerned with the current role; instead, it relates to an individual's satisfaction with the accumulation of their career‐related experiences (Rothwell & Arnold, Citation2007). For graduates, having invested a good deal of time, hard work, and for many, expense in gaining their qualifications, the attainment of a satisfying career is likely to be of great importance to them (e.g., Purcell, Elias, Davies, & Wilton, Citation2005). Research indicates that employability and career satisfaction are related concepts (De Vos & Soens, Citation2008; Rothwell & Arnold, Citation2007). However, this previous research has been carried out with broad population samples and may not generalise to working graduates.

Associations among the three concepts

So, by which mechanisms might ESE, graduate employability, and career satisfaction be associated? It would make sense that people who are confident in their ability to manage their emotions effectively also perform these behaviours, and as such enjoy better interpersonal relationships than those who are not; ESE is likely to help with employability issues, such as developing and maintaining networks, and being ‘kept in the know’ concerning possible opportunities. The current research aims to investigate whether ESE predicts self‐perceived graduate employability.

It may be that having well‐developed, job‐specific and generic skills—both aspects of employability—gives graduates confidence in their ability to gain alternative employment, either within their current organisation or elsewhere if necessary. As such, they are more likely to take a proactive approach where career management is concerned, making positive changes before they become dissatisfied with their careers. Therefore, this research aims to investigate the relationship between graduate employability and career satisfaction.

A further consideration is whether or not there is a direct relationship between ESE and career satisfaction. Confidence in one's emotional competence could create a more general positive approach to life and work, which then leads to a more favourable assessment of the current career situation. The current research will also investigate this possibility.

Finally, it could be that employability plays a mediating role between ESE and career satisfaction. Arnold (Citation2011) discusses the issue of career capital, defined as the accumulation of assets that improve a person's chances of career satisfaction. This would appear to be a very similar construct to employability: included within this definition are personal attributes, social contacts, and relationships. It is possible that ESE is one of these personal attributes that helps in the development and maintenance of social contacts and relationships, thereby enhancing employability. People who consider themselves better able to perceive, use, understand, and manage emotion should use these skills to form better interpersonal relationships with others in the workplace. As such, they are likely to enjoy wider, more supportive networks, and feel confident in their ability to gain and retain suitable employment that will bring them career satisfaction. The current study also explores the possible mediating role of employability in relation to ESE and career satisfaction.

The following hypotheses are formulated:

Hypothesis 1: There will be a positive correlation between ESE and self‐perceived employability.

Hypothesis 2: There will be a positive correlation between self‐perceived employability and career satisfaction.

Hypothesis 3: There will be a positive correlation between ESE and career satisfaction.

Hypothesis 4: Self‐perceived employability will mediate the effects of ESE on career satisfaction.

Method

Participants and procedure

An email was sent to approximately 4,000 graduates (graduated 2006, 2007, and 2008) who are alumni of a university in the north‐west of England, requesting their participation in a research study. The participants graduated from a wide range of disciplines, including business studies, electronic engineering, history, and human resource management. Further email reminders were sent 7 days and 14 days after the initial email invite. Respondents completed the questionnaire online. Three hundred six working graduates (M = 140, F = 164, not reported = 2; mean age = 28 years, standard deviation = 7.0) participated in the study. No incentives to take part in this study were provided.

Measures

Emotional self‐efficacy (ESE)

The Emotional Self‐Efficacy Scale (ESES) developed by Kirk et al. (Citation2008) originally comprised 32 items, with eight items representing each of the four branches of the Mayer and Salovey (Citation1997) model. Participants are required to rate their confidence in respect of each item by selecting a number on a 5‐point scale, with ‘1’ indicating ‘not at all confident’ and ‘5’ indicating ‘very confident’. The revised scoring system (Dacre Pool & Qualter, Citation2012b) was used in this study. Only 27 items are scored; they make up four subscales: (1) using and managing own emotions; example item ‘Calm down when feeling angry’; (2) identifying and understanding own emotions; example item ‘Correctly identify your own positive emotions’; (3) dealing with emotions in others; example item ‘Realise what causes another person to feel a positive emotion’; and (4) perceiving emotion through facial expressions and body language; example item ‘Notice the emotion another person's body language is portraying’. Cronbach's alpha for the four subscales ranged from 0.79 to 0.89.

Employability

A limited number of employability measures have been published in the literature. The three used in this research tap into the different elements of self‐perceived employability and are appropriate for use with a graduate sample; there are 19 items in total. The Self‐perceived Employability Scale (Rothwell & Arnold, Citation2007) comprises 11 items that make up two subscales (internal employability (four items) and external employability (seven items)). Participants are required to state their agreement with the items by selecting a number on a 5‐point scale, with ‘1’ indicating strong disagreement and ‘5’ indicating strong agreement. Examples of items include the following: ‘My personal networks in this organisation help me in my career’ (internal employability item) and ‘I could easily get a similar job to mine in almost any organisation’ (external employability item). Rothwell and Arnold (Citation2007) report good internal consistency for the measure (Cronbach's alpha for internal employability = 0.72, external employability 0.79, and the total scale 0.83). The Measure of Perceived Employability (Berntson & Marklund, Citation2007) comprises five items. Participants are required to state their agreement with the items by selecting a number on a 5‐point scale, with ‘1’ indicating strong disagreement and ‘5’ indicating strong agreement. Examples of items include the following: ‘My competence is sought‐after in the labour market’ and ‘I know of other organisations/companies where I could get work’. Cronbach's alpha for the total scale is good α = 0.88 (Berntson & Marklund, Citation2007). The Perceived Employability Scale (De Vos & Soens, Citation2008) comprises three items: ‘I believe I could easily obtain a comparable job with another employer’, ‘I believe I could easily obtain another job that is in line with my level of education and experience’ and ‘I believe I could easily obtain another job that would give me a high level of satisfaction’. Participants are required to state their agreement with the items by selecting a number on a 5‐point scale, with ‘1’ indicating strong disagreement and ‘5’ indicating strong agreement. De Vos and Soens (Citation2008) report good internal consistency for the measure, with Cronbach's alpha for the total scale = 0.91.

Career satisfaction

The Career Satisfaction Scale (De Vos & Soens, Citation2008, adapted from Martins, Eddleston, & Veiga, Citation2002), comprises three items that measure career satisfaction: ‘I am satisfied with my career status’, ‘I am satisfied with my current job’ and ‘I feel my career progress has been satisfactory’. Participants are required to state their agreement with the items by selecting a number on a 5‐point scale, with ‘1’ indicating strong disagreement and ‘5’ indicating strong agreement. De Vos and Soens (Citation2008) report good internal consistency for the measure, with Cronbach's alpha for the total scale n(289) = 0.87.

Analysis plan

This study uses structural equation modelling (SEM) techniques to investigate the relationships among ESE, employability, and career satisfaction. SEM is different to path analysis because it hypothesises that the variables under investigation may not be observable, and are thus better modelled as latent variables. Models that involve only observed variables (i.e., total scores) in regression or path models assume that measured variables are valid and reliable, but this is unrealistic in studies, like ours, where all measurements take place through self‐report questionnaires. Using SEM with latent variables of our constructs means that we can include measurement error components of unknown size that are likely to vary for the different instruments we used. Because not accounting for measurement error when it is present is a serious problem (Schumacker & Lomax, Citation2004), our SEM model includes latent variables with measurement error estimated in AMOS 17 (Arbuckle, Citation2008) using maximum likelihood estimation.

SEM requires relatively large sample sizes. Studies have shown that if sample size is sufficiently large, maximum likelihood (ML) parameter estimates are quite robust against violations of assumptions of multivariate normality and continuity of the data (West, Finch, & Curran, Citation1995). Some have suggested, as a rough guideline, a 5:1 ratio of sample size to number of parameters estimated in order to trust ML parameter estimates (Bentler & Chou, Citation1987). For models with highly reliable factors, quite satisfactory solutions can be obtained with relatively small samples, (e.g., Gagné & Hancock, Citation2006; Marsh, Hau, Balla, & Grayson, Citation1998); models with less reliable factors might require larger samples (Jackson, Citation2003).

Within our model, the four subscales of the ESES formed a latent variable of ESE. The latent variable of employability was formed from the 19 employability indicator variables that are items on the three employability scales. The three items from the De Vos career satisfaction measure formed a latent variable of career satisfaction. We posited that ESE would exert some direct influence on employability but also on career satisfaction, employability would influence career satisfaction, and that ESE would exert some indirect influence on career satisfaction through employability.

The structural equation model was performed in AMOS 17 (Arbuckle, Citation2008). All analyses were conducted using full information maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (Little & Rubin, Citation1987). The degree of model fit was used to make interpretations about the overall model, with parameter information being used to determine the associations between the variables; after initial testing, if the degree of model fit and parameter information suggested modification to the model with the removal of any given path, we removed that path and re‐ran the model. We adopt Kline's (Citation2011) recommendation and report several goodness‐of‐fit (GOF) statistics: the comparative fit index (CFI), normed fit index (NFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (Browne & Cudeck, Citation1992). Hu and Bentler's (Citation1999) proposals for thresholds for approximate model fit from these GOF statistics are the most widely used in the SEM literature, but there is debate regarding these cut‐off criteria; computer simulations cast doubt on the generality of these thresholds (see Kline, Citation2011, for discussion). From their computer simulations, Marsh, Hau, and Wen (Citation2004) highlighted some important problems in using the proposed cut‐off criteria in model fit assessment and suggested rules of thumb to use when testing hypotheses. Marsh et al. state that RMSEA would be expected to be less than 0.05 to be viewed as having a good fit, or between 0.05 and 0.08 for a reasonable fit to the data. According to Marsh et al., the CFI should exceed 0.90, as should NFI. The chi‐square index, which tests the null hypothesis of perfect fit to the data, should be as small as possible. According to the computer simulation studies, we would not necessarily expect all GOF statistics to be above these thresholds. We report unstandardised regression coefficients (B) and correlations (r, obtained as standardised regression coefficients). The alpha level is set to 0.05 throughout.

Results

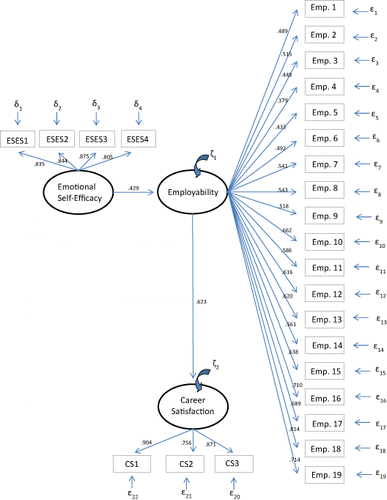

Table presents the descriptive statistics, the intercorrelations between subscale scores, and reliability coefficients (Cronbach's alpha) for the study variables. The significant correlations between the variables support the development of the proposed model. The baseline SEM model included direct paths from (1) the latent variable ESE to the latent variable employability and (2) from ESE to the latent variable career satisfaction. The model also included a path from employability to career satisfaction. This model was a reasonable fit to the data (χ2 (296, N = 306) = 734.52, p < .001, NFI = 0.80, CFI = 0.87, RMSEA = 0.07 (CI95 = 0.063, 0.076)). The squared multiple correlations provided within AMOS show that the latent variables of employability and career satisfaction were predicted reasonably accurately by other variables in the model (employability = 0.483, career satisfaction = 0.571). This model included a nonsignificant path from ESE to career satisfaction, suggesting that ESE did not directly affect career satisfaction; instead, ESE indirectly affected career satisfaction via employability. This path was subsequently removed from the model, which improved model fit slightly (χ2 (297, N = 306) = 655.06, p < .001, NFI = 0.89, CFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.06 (CI95 = 0.053, 0.066)). Based on the rules of thumb for determining acceptable levels of GOF detailed in Marsh et al. (Citation2004), the final model fit the data reasonably well. Figure 1 displays the final model, with all significant pathways included. The removal of the path from ESE to career satisfaction did not change the squared multiple correlations, suggesting that career satisfaction was influenced only by employability and not by ESE.

Figure 1. Final structural equation model linking emotional self‐efficacy and employability variables to career satisfaction and success.

Note. ESES1 = using and managing own emotions; ESES2 = identifying and understanding own emotions; ESES3 = dealing with emotions in others; ESES4 = perceiving emotion through facial expressions and body language; Emp. 1–Emp. 11 = Self‐perceived Employability Scale (Rothwell & Arnold, Citation2007); Emp. 12–Emp. 16 = Measure of Perceived Employability (Berntson & Marklund, Citation2007); Emp. 17–Emp. 19 = Perceived Employability Scale (De Vos & Soens, Citation2008); CS1–CS3 = Career Satisfaction Scale (De Vos & Soens, Citation2008).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics, intercorrelations, and reliability coefficients (Cronbach's alpha) for the study variables

Using latent variables in the current study meant that measurement error was present in our model. This is important because all of our measurements took place through self‐report. Common method variance (CMV) may still be a concern however, so a post hoc Harman one‐factor analysis (Harman, Citation1967) was carried out. Should the results reveal a single factor, or one general factor that accounts for the majority of covariance among the variables, this could suggest that CMV is a cause for concern. For our data, the test revealed 10 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1. These factors accounted for 67% of the variance, and the first factor accounted for 32%. This does not allow a definitive conclusion that CMV had no effect (Chang, Van Witteloostuijn & Eden, Citation2010), but suggests that its effects are limited in relation to these data.

Discussion

Findings from the current study provide support for Hypothesis-1 showing that ESE is significantly related to employability; it appears that working graduates who have higher ESE also perceive themselves as highly employable. This implies that beliefs concerning emotional competence influence self‐perceived employability; people who are more confident in their abilities to perceive, use, understand, and manage emotion also consider themselves more employable. Employability is concerned with having certain skills and attributes that make a person more likely to choose, secure, and retain employment, such as having good personal networks, being aware of opportunities, and feeling respected within an organisation. Somebody who is confident in his/her emotional competence, and sees himself/herself as an effective communicator with his/her colleagues, managers, and customers, is more likely to be able to develop and maintain personal networks and gain the respect of others.

The findings regarding the associations among ESE, graduate employability, and career satisfaction are also of importance. In line with Rothwell and Arnold (Citation2007), De Vos and Soens (Citation2008), and supporting Hypothesis-2, we found a significant relationship between employability and career satisfaction, but we fill a gap in the research by showing this association within a graduate sample. Further, in support of Hypothesis-4, we found that ESE did not have a direct effect on career satisfaction, but operated indirectly via employability. Thus, having confidence in your emotional competence does not in itself bring you career satisfaction; instead, it most likely results in better communication and social interaction in the workplace, increasing feelings of perceived employability, which leads to a more satisfying career. It is possible that over time, there is a bidirectional effect with increasing career satisfaction leading to increases in perceived employability. Future prospective work will enable such an investigation.

The current findings must be seen within the context of the self‐efficacy and emotional skills distinction (Dacre Pool & Qualter, Citation2012b). It may not be sufficient to possess the ability to accurately recognise and manage emotions such as anger or confusion in a colleague or customer; confidence in these abilities is also necessary for greater emotional competence in the workplace. This not only means that future research will want to establish the links between both emotional abilities and ESE in predicting behaviour that enhances employability, but also that any interventions designed to increase graduate employability should look to increase both skills and confidence.

Such ideas are important within models of graduate employability development, which propose that undergraduate students should be given the opportunity to develop their emotional skill while within higher education (Dacre Pool & Sewell, Citation2007). It seems students should also be given the opportunity to gain confidence in their emotional competence. Both the teaching of emotional skill and the increasing of ESE can be achieved through teaching and learning schemes that provide students with knowledge of emotional functioning and emotion management strategies (Dacre Pool & Qualter, Citation2012a). Giving students the opportunity to practice possible emotion management strategies and then reflect on these mastery experiences within a safe and supportive environment will increase their levels of self‐efficacy in relation to emotional competence (Bandura, Citation1995). Based on these results, including such opportunities for students to increase their levels of ESE as part of their learning experiences should also result in an enhancement of their employability and general career satisfaction.

There are some limitations to this study that should be noted, including the self‐selecting sample, which could create bias. Additionally, the design is cross‐sectional, and it is not possible to be certain about the direction of causality in the data. Further studies should examine the relationships longitudinally. Also, the study utilised measurement tools that were all self‐report, and as such is reliant on participants' self‐perceptions of their ESE and employability. This could contribute to common method bias (see Spector, Citation2006, for a detailed discussion), although the post hoc analysis carried out does not indicate that CMV was a problem in relation to these data. Future studies may be able to utilise observational methodology to study what it is that people higher in EI and/or ESE actually do in the workplace. Such a design would mean that possible mechanisms by which these concepts influence behaviour can be examined. For example, in relation to managing emotion, do high EIs/high ESEs actively manage conflict or are they are able to spot potential conflict before it happens and withdraw from the situation? While a strength of this study is the inclusion of graduates from many different disciplines, the small number from each meant that it was not possible to explore the pattern of effects across the different disciplines. As earlier work (Sánchez‐Ruiz, Pérez‐González, & Petrides, Citation2010) found differences in trait EI between students of different disciplines, it is possible that ESE and graduate employability may vary across domains. Future studies may want to explore this. It might also be useful to explore gender in future studies.

Our findings show that emotional self‐efficacy is an important aspect of graduate employability. Previous work also shows that it is possible to design and deliver appropriate interventions that increase levels of EI and ESE in undergraduate students (Dacre Pool & Qualter, Citation2012a). Together, these empirical findings provide some support for the idea of including appropriate ‘emotional’ learning experiences within the higher education curricula. However, if such learning is to be included, the teaching needs to be empirically based and its potential impact evaluated (e.g., Qualter, Gardner, & Whiteley, Citation2007; Zeidner, Roberts, & Matthews, Citation2002).

In conclusion, we found that emotional self‐efficacy is important for graduate employability and career satisfaction. This study adds to the literature on graduate employability by providing some empirical evidence of predictors and outcomes, which support the inclusion within educational curricula of activities to develop and improve emotional competence. In addition to the more general life benefits that improved emotional competence brings, it should also enhance graduate employability; ensuring graduates have a greater chance of securing and retaining occupations in which they can experience satisfaction and success.

Acknowledgement

We wish to thank F. Mathieson and J. Lee for their help with data collection.

References

- Arbuckle, J. L. (2008). AMOS 17 user's guide. Chicago, IL: SPSS.

- Arnold, J. (2011). Career concepts in the 21st century. The Psychologist, 24(2), 106–109.

- Bandura, A. (1995). Exercise of personal and collective efficacy in changing societies. In A. Bandura (Ed.), Self‐efficacy in changing societies (pp. 1–45). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self‐efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company.

- Bandura, A., Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Gerbino, M., & Pastorelli, C. (2003). Role of affective self‐regulatory efficacy in diverse spheres of psychosocial functioning. Child Development, 74(3), 769–782. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467‐8624.00567

- Bentler, P. M., & Chou, C. P. (1987). Practical issues in structural equation modeling. Sociological Methods & Research, 16, 78–117.

- Berntson, E., & Marklund, S. (2007). The relationship between perceived employability and subsequent health. Work & Stress, 21(3), 279–292. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370701659215

- Bowden, J., Hart, G., King, B., Trigwell, K., & Watts, O. (2000). Generic capabilities of ATN University graduates. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Education, Training and Youth Affairs.

- Bridgstock, R. (2009). The graduate attributes we've overlooked: Enhancing graduate employability through career management skills. Higher Education Research & Development, 28(1), 31–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360802444347

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research, 21, 230–258. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124192021002005

- Chang, S.‐J., van Witteloostuijn, A., & Eden, L. (2010). From the editors: Common method variance in international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 41, 178–184. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2009.88

- Dacre pool, L., & Qualter, P. (2012a). Improving emotional intelligence and emotional self‐efficacy through a teaching intervention for university students. Learning and Individual Differences, 22, 306–312. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2012.01.010

- Dacre pool, L., & Qualter, P. (2012b). The dimensional structure of the Emotional Self‐efficacy Scale (ESES). Australian Journal of Psychology, 64, 147–154. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742‐9536.2011.00039.x

- Dacre pool, L., & Sewell, P. (2007). The key to employability: Developing a practical model of graduate employability. Education and Training, 49(4), 277–289. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910710754435

- De vos, A., & Soens, N. (2008). Protean attitude and career success: The mediating role of self‐management. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73, 449–456. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2008.08.007

- Gagné, P. E., & Hancock, G. R. (2006). Measurement model quality, sample size, and solution propriety in confirmatory factor models. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 41, 65–83.

- Galla, B. M., & Wood, J. J. (2012). Emotional self‐efficacy moderates anxiety‐related impairments in math performance in elementary school‐age youth. Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 118–122. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.09.012

- Gundlach, M. J., Martinko, M. J., & Douglas, S. C. (2003). Emotional intelligence, causal reasoning and the self‐efficacy development process. The International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 11(3), 229–246.

- Harman, H. H. (1967). Modern factor analysis (2nd ed., revised). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Harvey, L. (2001). Defining and measuring employability. Quality in Higher Education, 7(2), 97–109. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13538320120059990

- Harvey, L. (2003). On employability. The Higher Education Academy. Retrieved April 30, 2013, from http://www.qualityresearchinternational.com/esecttools/esectpubs/harveyonemp.pdf

- Harvey, L. (2005). Embedding and integrating employability. New Directions for Institutional Research, 128, 13–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ir.160

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Jackson, D. L. (2003). Revisiting sample size and number of parameter estimates: Some support for the N:q hypothesis. Structural Equation Modeling, 10, 128–141.

- Jaeger, A. J. (2003). Job competencies and the curriculum: An inquiry into emotional intelligence in graduate professional education. Research in Higher Education, 44(6), 615–639. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026119724265.

- Kerr, R., Garvin, J., Heaton, N., & Boyle, E. (2006). Emotional intelligence and leadership effectiveness. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 27(4), 265–279. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730610666028

- Kidwell, B., Hardesty, D. M., Murtha, B., & Sheng, S. (2011). Emotional intelligence in marketing exchanges. Journal of Marketing, 75, 78–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.75.1.78

- Kirk, B. A., Schutte, N. S., & Hine, D. W. (2008). Development and preliminary validation of an emotional self‐efficacy scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 45, 432–436. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.06.010

- Kirk, B. A., Schutte, N. S., & Hine, D. W. (2011). The effect of an expressive writing intervention for employees on emotional self‐efficacy, emotional intelligence, affect, and workplace incivility. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41(1), 179–195. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559‐1816.2010.00708.x

- Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). London: The Guildford Press.

- Knight, P., & Yorke, M. (2004). Learning, curriculum and employability in higher education. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

- Liptak, J. J. (2005). Using emotional intelligence to help college students succeed in the workplace. Journal of Employment Counseling, 42, 171–178. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161‐1920.2005.tb01088.x

- Little, R. J. A., & Rubin, D. B. (1987). Statistical analysis with missing data. New York: John Wiley.

- Lowden, K., Hall, S., Elliot, D., & Lewin, J. (2011). Employers' perceptions of the employability skills of new graduates. London: Edge Foundation.

- Marsh, H. W., Hau, K.‐T., Balla, J. R., & Grayson, D. (1998). Is more ever too much? The number of indicators per factor in confirmatory factor analysis. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 33, 181–220.

- Marsh, H. W., Hau, K. T., & Wen, Z. L. (2004). In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralising Hu & Bentler (1999) findings. Structural Equation Modeling, 11, 320–341. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1103_2

- Martins, L. L., Eddleston, K. A., & Veiga, J. F. (2002). Moderators of the relationship between work‐family conflict and career satisfaction. Academy of Management Journal, 45(2), 399–409.

- Mayer, J. D., Caruso, D., & Salovey, P. (1999). Emotional intelligence meets traditional standards for an intelligence. Intelligence, 27, 267–298. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160‐2896(99)00016‐1

- Mayer, J. D., & Salovey, P. (1997). What is emotional intelligence? In P. Salovey & D. Sluyter (Eds.), Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Implications for educators (pp. 3–31). New York: Basic Books.

- Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., & Caruso, D. R. (2002). Mayer‐Salovey‐Caruso emotional intelligence test—MSCEIT. User's manual. Toronto: Multi‐Health Systems.

- Mikolajczak, M., Petrides, K. V., Coumans, N., & Luminet, O. (2009). The moderating effect of trait emotional intelligence on mood deterioration following laboratory‐induced stress. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 9(3), 455–477.

- Mueller, J., & Curhan, J. (2006). Emotional intelligence and counterpart mood induction in a negotiation. International Journal of Conflict Management, 17, 110–128.

- Nelis, D., Kotsou, I., Quoidbach, J., Hansenne, M., Weyens, F., Dupuis, P., & Mikolajczak, M. (2011). Increasing emotional competence improves psychological and physical well‐being, social relationships and employability. Emotion, 11(2), 354–366. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021554.

- O'boyle, E. H. Jr, Humphrey, R. H., Pollack, J. M., Hawver, T. H., & Story, P. A. (2010). The relation between emotional intelligence and job performance: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(5), 788–818. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/job.714

- Pegg, A., Waldock, J., Hendy‐isaac, S., & Lawton, R. (2012). Pedagogy for employability. York: The Higher Education Academy.

- Petrides, K. V., & Furnham, A. (2001). Trait emotional intelligence: Psychometric investigation with reference to established trait taxonomies. European Journal of Personality, 15, 425–448. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/per.416

- Petrides, K. V., & Furnham, A. (2006). The role of trait emotional intelligence in a gender‐specific model of organizational variables. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36, 552–569. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0021‐9029.2006.00019.x

- Petrides, K. V., Pérez‐gonzález, J. C., & Furnham, A. (2007). On the criterion and incremental validity of trait emotional intelligence. Cognition and Emotion, 21(1), 26–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930601038912

- Petrides, K. V., Pita, R., & Kokkinaki, F. (2007). The location of trait emotional intelligence in personality factor space. British Journal of Psychology, 98, 273–289. doi:https://doi.org/10.1348/000712606x120618

- Purcell, K., Elias, P., Davies, R., & Wilton, N. (2005). The Class of ′99. A study of the early labour market experiences of recent graduates. A report to the Department for Education & Skills (UK). Retrieved April 30, 2013, from http://www.hecsu.ac.uk/assets/assets/documents/Class_99_Full.pdf

- Qualter, P., Barlow, A., & Stylianou, M. S. (2011). Investigating the relationships between ability and trait emotional intelligence, and theory of mind. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 29, 437–454. doi:https://doi.org/10.1348/026151010X502999

- Qualter, P., Gardner, K. J., Pope, D., Hutchinson, J. M., & Whiteley, H. E. (2012). Ability emotional intelligence, trait emotional intelligence, and academic success in British secondary schools: A 5‐year longitudinal study. Learning and Individual Differences, 22, 83–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2011.11.007

- Qualter, P., Gardner, K. J., & Whiteley, H. E. (2007). Emotional intelligence: Review of research and educational implications. Pastoral Care, 25(1), 11–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468‐0122.2007.00395.x

- Repetto talavera, E., & Pérez‐gonzález, J. C. (2007). Training in socio‐emotional skills through on‐site training. European Journal of Vocational Training, 40(1), 83–102.

- Rothwell, A., & Arnold, J. (2007). Self‐perceived employability: Development and validation of a scale. Personnel Review, 46(1), 23–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480710716704.

- Sánchez‐ruiz, M. J., Pérez‐gonzález, J. C., & Petrides, K. V. (2010). Trait emotional intelligence profiles of students from different university faculties. Australian Journal of Psychology, 62(1), 51–57. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/000495309033129707

- Schumacker, R. E., & Lomax, R. G. (2004). A beginner's guide to structural equation modeling. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Sewell, P., & Dacre pool, L. (2010). Moving from conceptual ambiguity to operational clarity. Employability, enterprise and entrepreneurship in higher education. Education and Training, 52(1), 89–94. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/00400911017708

- Spector, P. (2006). Method variance in organizational research. Truth or urban legend? Organizational Research Methods, 9(2), 221–232. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428105284955

- Tariq, V. N., Qualter, P., Roberts, S., Appleby, Y., & Barnes, L. (2013). Mathematical literacy in undergraduates: Role of gender and emotional intelligence. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, i‐First. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0020739X.2013.770087

- Van rooy, D. L., Viswesvaran, C., & Pluta, P. (2005). An evaluation of construct validity: What is this thing called emotional intelligence? Human Performance, 18, 445–462. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327043hup1804_9

- Vandervoort, D. J. (2006). The importance of emotional intelligence in higher education. Current Psychology: Developmental‐Learning‐Personality‐Social, 25(1), 4–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144‐006‐1011‐7

- Vitello‐cicciu, J. M. (2001). Leadership practices and emotional intelligence of nursing leaders (Unpublished dissertation), Fielding Graduate Institute, Santa Barbara, CA. Cited in Vitello‐Cicciu, J. M. (2003). Emotional intelligence. Nursing Management. doi:10.1097/00006247‐200310000‐00010

- West, S. G., Finch, J. F., & Curran, P. J. (1995). Structural equation models with non‐normal variables. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications (pp. 56–75). London: Sage.

- Wittekind, A., Raeder, S., & Grote, G. (2010). A longitudinal study of determinants of perceived employability. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31, 566–586. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/job.646

- Yorke, M. (2006). Employability in higher education: What it is—what it is not. Learning and Employability Series One. York: The Higher Education Academy.

- Yorke, M., & Knight, P. T. (2006). Curricula for economic and social gain. Higher Education, 51, 565–588. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734‐004‐1704‐5.

- Zeidner, M., Roberts, R. D., & Matthews, G. (2002). Can emotional intelligence be schooled? A critical review. Educational Psychologist, 37(4), 215–231. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3704_2