Abstract

Understanding the factors that contribute to sun exposure is vital for skin cancer prevention. The present study aimed to examine the utility of a new measure for cancer prevention research, the Skin Tone Rating Scale. Australian undergraduate women (N = 156) completed an online questionnaire measuring skin tone dissatisfaction, peer and media norms surrounding tanning, internalisation of a tanned ideal, appearance reasons for tanning, and self‐reported tanning behaviour. The two‐item Skin Tone Rating Scale provided a short and easy‐to‐administer measure of skin tone dissatisfaction that correlated with self‐reported tanning behaviour. The Skin Tone Rating Scale was also moderately related to appearance reasons for tanning and internalisation of a tanned ideal, demonstrating concurrent validity. Socio‐cultural influences (from peers and media) were positively correlated with skin tone dissatisfaction, and this relationship was partially mediated by internalisation of a tanned ideal. Although more research is needed to establish causation, this study provides an important addition to sun tanning literature; it provides a new measure to predict self‐reported tanning behaviour, the Skin Tone Rating Scale, which highlights the importance of appearance concerns in relation to tanning and sun exposure.

Despite numerous social marketing campaigns, Australia has one of the highest rates of skin cancer in the world (Shih, Carter, Sinclair, Mihalopoulos, & Vos, Citation2009; Stanton, Janda, Baade, & Anderson, Citation2004). The causal link between ultraviolet radiation from the sun and cancers of the skin is well established (Hussein, Citation2005; Narayanan, Saladi, & Fox, Citation2010). Although skin cancer is largely preventable, large numbers of people, particularly young adults and women, report engaging in deliberate sun exposure behaviours in an attempt to darken skin tone (Dobbinson et al., Citation2008; Hillhouse, Stair, & Adler, Citation1996; Leary & Jones, Citation1993; Stanton et al., Citation2004). It is vital to identify factors that contribute to tanning behaviour. Doing so will provide valuable insight when developing interventions to reduce dangerous levels of sun exposure.

One main reason that people participate in tanning is the perceived positive effect that a tanned skin has on appearance and attractiveness (Cafri et al., Citation2006b; Cafri et al., Citation2008; Hillhouse et al., Citation1996; Jackson & Aiken, Citation2000; Leary & Jones, Citation1993; Sahn, McIlwain, Magee, Veledar, & Chen, Citation2012). Appearance concerns and the belief that having a tan skin tone increases attractiveness to others have been shown to predict UV exposure in young adults (Leary & Jones, Citation1993). Social‐cultural models of body image can be applied to the formation of attitudes to tanning and skin tone ideals because socio‐cultural factors perpetuate ideals about what constitutes an ‘attractive’ appearance (Cafri et al., Citation2006b). The tripartite influence model identifies social norms as critical, and stipulates that the media, family, and peers all impact upon a desired image by encouraging the internalisation of particular, socially endorsed ideals (Thompson, Heinberg, Altabe, & Tantleff‐Dunn, Citation1999). According to the tripartite influence model, internalisation of the ‘thin ideal’ mediates the relationship between peer, media, and family norms, and body shape and size dissatisfaction (Thompson et al., Citation1999). Tanned skin is considered a Western cultural ideal comparable to thinness (Cafri et al., Citation2006b). Conversely, pale skin is considered socially undesirable in Western culture, particularly in Australia (Potente, Coppa, Williams, & Engels, Citation2011). Just as internalisation of the ‘thin ideal’ leads to body size dissatisfaction, internalisation of this tanned ideal is likely to result in skin tone dissatisfaction.

Existing research confirms that socio‐cultural factors (i.e., the messages about tanned skin conveyed by the media, peers, and to a lesser extent, family) impact upon what people believe defines attractiveness, and that this in turn influences tanning attitudes and behaviours. Jackson and Aiken (Citation2000) established that participants who believed the media endorsed a tanned ideal were more likely to suntan. Exposure to tanned images in magazines has also been shown to predict beliefs about and attitudes to tanning (Cho, Lee, & Wilson, Citation2010; Dixon, Warne, Scully, Wakefield, & Dobbinson, Citation2011), and negative media have been shown to increase the awareness of cancer risk associated with solaria use (Jalleh, Donovan, Lin, & Slevin, Citation2008). The attitudes and tanning behaviours of family members have not been as consistently related to tanning behaviour (e.g., see Cafri et al., Citation2006b). There is, however, strong evidence for the influence of peers on tanning behaviour whereby engagement in tanning behaviour is associated with having friends or peers who also tan (Jackson & Aiken, Citation2000; Keesling & Friedman, Citation1987; Wichstrøm, Citation1994). This is perhaps because sunbathing may be perceived as a social activity, best undertaken in the company of friends (Wichstrøm, Citation1994). In addition, incidental sun exposure can occur when individuals avoid sun protection because of the opinions of peers (Potente et al., Citation2011). In sum, studies concerned with the influence of media and peer behaviour and attitudes to tanning have shown that these socio‐cultural factors influence tanning and sun‐protective behaviours by magnifying appearance concerns (Cafri, Thompson, & Jacobsen, Citation2006a; Cafri, Thompson, Jacobsen, & Hillhouse, Citation2009). Data with families are less convincing. Notwithstanding the results to date, the specific role of subjective dissatisfaction with skin tone on sun exposure behaviours remains unaddressed.

The present study examined the specific role of the discrepancy between current skin tone and desired skin tone (skin tone dissatisfaction) as an appearance‐focused measure to predict sun exposure. The current study was conducted with young females because they are more likely to be concerned with their appearance and are a high risk group for high levels of UV exposure, putting them at risk of skin cancer later in life (Cafri et al., Citation2006b; Choi et al., Citation2010; Francis, Dobbinson, Wakefield, & Girgis, Citation2010). In addition, research indicates that women are also more likely to deliberately tan than men (Choi et al., Citation2010; Stanton et al., Citation2004); tanning among men is more likely to be incidental. The aim of the present study was to determine whether skin tone dissatisfaction could predict self‐reported sun tanning behaviour in young women.

Specifically, it was hypothesised that (1) higher skin tone dissatisfaction, as indicated by a larger discrepancy score on the Skin Tone Rating Scale, would be associated with greater self‐reported participation in tanning; (2) scores on the Skin Tone Rating Scale would be positively correlated with scores on other appearance‐focused measures of tanning (e.g., appearance reasons for tanning and internalisation of a tanned ideal); and (3) internalisation of a tanned ideal would mediate the relationship between peer and media norms and skin tone dissatisfaction. Specifically, it was predicted that perceptions of the tanned ideal portrayed by peers and media would be positively related to attractiveness of a tan, which would in turn be positively associated with higher skin tone dissatisfaction.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 156 Caucasian female students ranging in age from 17 to 27 years (M = 19.45, standard deviation (SD) = 2.18) recruited from Flinders University, South Australia.

Measures

Measures were presented to participants in an online questionnaire designed to assess tanning beliefs, tanning behaviours, and skin tone dissatisfaction. The questionnaire took approximately 15-min to complete.

Demographic information and tanning behaviour

All participants were asked to indicate their age and ethnicity. Following Jackson and Aiken (Citation2000), past tanning behaviour was assessed with an open‐ended question by asking participants to indicate, on average, how many hours per week they spent intentionally sun tanning in summer, and how many times per month they would get a solarium tan.

Skin tone dissatisfaction

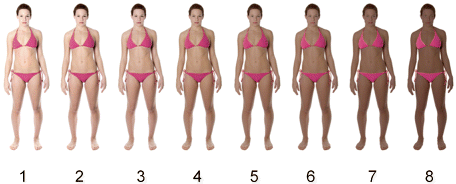

The Skin Tone Rating Scale was developed for the present study to measure skin tone dissatisfaction (see Fig. 1). The measure developed for the present study was based upon the Body Image Fig. Rating Scale (Stunkard, Sorenson, & Schlusinger, Citation1983). The perceived discrepancy between current and ideal self‐perceptions has been widely used to measure body size dissatisfaction, and the index has been validated as a predictor of dieting and eating disorders (Thompson & Altabe, Citation1991). Our scale presents participants with eight female figures, increasing in level of tan from very pale to very tanned (rather than increasing in body size). Using the photo editing program Adobe Photoshop (CS Version 8, Adobe Systems Incorporated, San Jose, CA, USA), each image in between was adjusted such that there was an even distribution from lightest to darkest skin tone across all images. Each figure differed in opacity by approximately 10%. This was done to ensure that the set was ‘visually even’ over the complete set of figures while also ensuring that there was enough of a discriminable difference in skin tone between each image. Participants were first asked to select the figure with the skin tone that they felt best represented their own (range = 1–8). They were then asked to select the figure (range = 1–8) that best represented their desired skin tone. Dissatisfaction with current skin tone was calculated by subtracting a participant's current skin tone score from their ideal skin tone score. Possible scores ranged from −7 to +7, with a score of 0 indicating total satisfaction with current skin tone. Positive scores indicated a desire for a darker skin tone, whereas a negative score demonstrated a desire for paler skin tone. To date, while previous research has examined participants' preferences for and views about different types of tans using images portraying differing levels of tan (e.g., Broadstock, Borland, & Gason, Citation1992; Dixon, Borland, & Hill, Citation1999), the discrepancy between current and ideal tan has not been examined.

Figure 1. The Skin Tone Rating Scale. Participants select the image that best represents their current skin tone and then the image that best represents their desired skin tone.

In order to evaluate the test–retest reliability of the Skin Tone Rating Scale, a subset of 32 participants volunteered to complete the scale on two occasions (separated by 3 months). Test–retest reliability coefficients for current and ideal skin tone over the 3‐month period were large (r = .75, p = .001 and r = .56, p = .001, respectively). The reliability of the difference between current and ideal skin tone (skin tone dissatisfaction) was also large, r = .62, p = .001. The 3‐month period occurred over winter; thus, not surprisingly, there was a significant reduction in participants' current skin tone rating, t(31) = 3.52, p = .001, d = .47 (baseline M = 2.34, SD = 1.21; 3 month M = 1.84, SD = 0.92), indicating lighter skin over the colder months. The reduction in desired skin tone over this period approached significance, t(31) = 1.8, p = .07, d = .31 (baseline M = 3.78, SD = 1.31; 3 month M = 3.41, SD = 1.04). Overall, however, participants' dissatisfaction with their skin tone did not significantly change, t(31) = −0.81, p = .423, d = .12 (baseline M = 1.44, SD = 1.01; 3 month M = 1.56, SD = 0.98). Test–retest reliability for a separate community sample of 17 women (Mage = 27.12, SD = 9.40) who completed the scale 1–2 weeks apart was high (current: r = .85, p = .001; ideal: r = .85, p = .001; discrepancy: r = .89, p = .001).

Peer and media influence

Peer and media influence on tanning was measured using Jackson and Aiken's (Citation2000) subscales assessing peer norms for sun protection (four items) and sunbathing (five items), and perceptions of tanned images in the media (five items). Responses ranged from 1, strongly disagree/not at all, to 6, strongly agree/very much. Following Jackson and Aiken (Citation2000), a mean score was calculated for this combined scale. Scores ranged from 1 to 6, with higher scores indicative of greater perceptions of peer and media norms supportive of a tanned appearance. In the present study, Cronbach's alpha for the combined measure was acceptable, α = .65.

Physical Appearance Reasons for Tanning Scale (PARTS)

The PARTS (Cafri et al., Citation2006b) was utilised to assess appearance motivations for tanning and to determine the concurrent validity of the Skin Tone Rating Scale. The 27‐item scale incorporates questions on general attractiveness, influence from media, influence of family, concerns about acne, physical fitness, and concerns about skin aging. Participants responded to each item on a 5‐point Likert scale, ranging from 1, strongly disagree, to 5, strongly agree. A mean score for all items on this scale was calculated, with higher scores indicative of a greater desire to get a tan for appearance reasons. Internal reliability in the present study for the entire scale was high, α = .92.

Internalisation of a tanned ideal

Internalisation of a tanned ideal was measured using Jackson and Aiken's (Citation2000) seven‐item Beliefs About Attractiveness Scale, which measured the perceived advantages of sunbathing (e.g., ‘I feel more attractive with a tan’). Responses ranged from 1, strongly disagree, to 6, strongly agree. Mean scores were calculated (range = 1–6), and higher scores indicated that a person found a tan more attractive and important to them (higher internalisation of the tanned ideal). Jackson and Aiken (Citation2000) established high internal consistency for the scale, α = .93 (Study 1) and α = .95 (Study 2). In the present study, internal consistency was also high, α = .95.

Procedure

Upon receiving ethics approval from the university's ethics committee, the study was advertised online to first year psychology students. Participants received course credit in exchange for their participation. Out of a pool of approximately 300 female first year psychology students, 156 young women chose to participate in the study. This represents a response rate of approximately 52%.

Results

Characteristics of the sample

Overall, 64.1% of the sample self‐reported that they intentionally tanned on at least one occasion per week over the previous summer, spending an average of 3.27-hr (SD = 5.36) per week on this behaviour. Only 11 participants (7.1%) reported engaging in solarium tanning. Of participants who did solarium tan, all also reported that they suntanned, and when their solarium tanning levels were added to their sun tanning, it made negligible difference to the correlations. Therefore, solarium tanning was excluded from further analyses. Table shows the descriptive statistics for all measures used.

Table 1. Means (and standard deviations) for all variables measured among 156 Australian undergraduate women

Skin tone dissatisfaction and sun tanning behaviour

Mean skin tone dissatisfaction was low (Table ). A single‐sample t‐test indicated that the mean skin tone dissatisfaction score was significantly different from zero, t(155) = 18.06, p < .001, d = 1.45. Table presents the correlation coefficients for the relationships between skin tone dissatisfaction and self‐reported sun tanning behaviour, internalisation of a tanned ideal, and appearance reasons for tanning (PARTS). As predicted, higher skin tone dissatisfaction was associated with more participation in sun tanning behaviour (see Table ).

Table 2. Correlations between skin tone dissatisfaction and the Physical Appearance Reasons for Tanning Scale (PARTS), internalisation of a tanned ideal, peer and media influence, and sun exposure

As this was the first time the Skin Tone Rating Scale had been used, it was compared to the PARTS. As an indication of concurrent validity, skin tone dissatisfaction was also moderately positively associated with both appearance reasons for tanning and internalisation of a tanned ideal (see Table ). Both skin tone dissatisfaction and appearance reasons for tanning were significantly positively related to sun tanning behaviour. Fisher's t‐test for the difference between two non‐independent correlation coefficients (Howell, Citation1992) showed that there was no significant difference between the two correlations, t(148) = 0.202, p > .05, suggesting that both scales are equally effective at predicting sun tanning behaviour.

Potential mediators of the relationship between peer and media influence and skin tone dissatisfaction

Following guidelines specified by Preacher and Hayes (Citation2008), based on the relationships in Table , we tested whether internalisation of a tanned ideal and appearance reasons for tanning mediated the relationship between peer and media influence and skin tone dissatisfaction. Internalisation of a tanned ideal (and not appearance reasons for tanning) partially mediated the relationship between peer and media influence and skin tone dissatisfaction (see Table ).

Table 3. Multiple mediation analyses (MMA) with unstandardised coefficients (and standard error (SE)), and estimates of direct and indirect pathways (with 95% confidence intervals (CI)), examining peer and media influence as a predictor of skin tone dissatisfaction, N = 145

Conclusions and Implications

In order to prevent excessive sun exposure and decrease cancer risk, there is a particular need for measures that are able to predict sun tanning behaviour. The present study demonstrated that a simple two‐item measure, the Skin Tone Rating Scale, was a correlate of past self‐reported tanning behaviour. These findings add to previous literature that has established that generalised body dissatisfaction is positively linked to tanning behaviour (Banerjee, Campo, & Greene, Citation2008; Brandberg, Ullen, Sjoberg, & Holm, Citation1998; Leary & Jones, Citation1993; Wichstrøm, Citation1994). From a public health perspective, this suggests that targeting skin tone dissatisfaction may be one way to reduce sun tanning behaviour. In addition, future research should consider the Skin Tone Rating Scale as a quick and effective way to measure appearance concerns and as a potential predictor of sun tanning behaviour.

The second aim of the present study was to determine whether skin tone dissatisfaction was predicted by socio‐cultural influences (e.g., peer, media). Results confirmed the role that perceptions of peer and media norms play in skin tone dissatisfaction. Analyses also established that the relationship between perceived socio‐cultural influence and skin tone dissatisfaction was partially mediated by internalisation of a tanned ideal. Thus, the findings demonstrate that people who internalise attitudes towards tanning based on the perceived beliefs of others are more likely to be dissatisfied with their skin tone. It may be possible to reduce skin tone dissatisfaction by manipulating perceptions of peer and media attitudes, and consequently altering how much people internalise beliefs about the attractiveness of a tan. One way this could be done is by promoting pale skin as the new image norm for attractiveness among peers and celebrities/models in magazines and other forms of visual media. Currently, the norms implicit within popular media (e.g., magazines) consist of images of young women with dark tans and poor sun‐protective behaviours (Dixon, Dobbinson, Wakefield, Jamsen, & McLeod, Citation2008).

The results of the present study should be considered in light of a number of limitations arising from study design, sampling, and materials. The study was cross‐sectional and correlational in nature. As such, it is possible that the relationships identified run in the reverse causal order, whereby increased tanning leads to increased skin tone dissatisfaction, which may result in increased perceived pressure from peers and media to tan. This seems unlikely. Findings from the body image literature (e.g., Groesz, Levine, & Murnen, Citation2002; Grogan, Citation2008; Stice, Maxfield, & Wells, Citation2003) confirm that peer and media have a causal influence on body dissatisfaction, a finding that must be confirmed for skin tone dissatisfaction.

The measure of tanning behaviour used in the present study may not have been an accurate estimate of actual tanning behaviour; the data for this study were collected during autumn and participants were asked to recall their tanning levels from the previous summer. Future research should assess tanning behaviour and skin tone dissatisfaction during summer, perhaps with the use of a sun exposure diary or objective measures of UVR exposure (e.g., UV dosimeter) as a more accurate measure of tanning behaviour. Lastly, in its current form, the Skin Tone Rating Scale is only useful for the female population and was tested in the present study with Caucasian undergraduate women. Young Caucasian women were selected because they participate in a number of behaviours that can lead to skin cancer (Cafri et al., Citation2006b; Choi et al., Citation2010; Francis et al., Citation2010). Future research is needed to modify the scale to test its utility among other samples (i.e., males, different skin types).

In sum, the Skin Tone Rating Scale is a short and easy‐to‐administer two‐item measure of current and ideal skin tone that can be used to predict self‐reported tanning behaviour. The present study demonstrated that skin tone dissatisfaction, as measured by the Skin Tone Rating Scale, is associated with young women's self‐reported tanning behaviour. Furthermore, skin tone dissatisfaction can be conceptualised in a similar way to body dissatisfaction; socio‐cultural influence models are a useful framework to determine predictors of skin tone dissatisfaction. The results highlight the importance of further exploring the genesis of skin tone dissatisfaction and addressing the socio‐cultural ideal of tanned skin being beautiful, perhaps by increasing the value of pale skin in the media, in order to reduce sun tanning behaviour among women and reduce skin cancer incidence.

References

- Banerjee, S. C., Campo, S., & Greene, K. (2008). Fact or wishful thinking? Biased expectations in ‘I think I look better when I'm tanned’. American Journal of Health Behavior, 32, 243–252.

- Brandberg, Y., Ullen, H., Sjoberg, L., & Holm, L. E. (1998). Sunbathing and sunbed use related to self‐image in a randomized sample of Swedish adolescents. European Journal of Cancer Prevention, 7, 321–329.

- Broadstock, M., Borland, R., & Gason, R. (1992). Effects of suntan on judgements of healthiness and attractiveness by adolescents. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 22, 157–172. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559‐1816.1992.tb01527.x

- Cafri, G., Thompson, J. K., & Jacobsen, P. B. (2006a). Appearance reasons for tanning mediate the relationship between media influence and UV exposure and sun protection. Archives of Dermatology, 142, 1067–1069.

- Cafri, G., Thompson, J. K., Jacobsen, P. B., & Hillhouse, J. (2009). Investigating the role of appearance‐based factors in predicting sunbathing and tanning salon use. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32, 532–544. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865‐009‐9224‐5

- Cafri, G., Thompson, J. K., Roehrig, M., Rojas, A., Sperry, S., Jacobsen, P. B., & Hillhouse, J. (2008). Appearance motives to tan and not tan: Evidence for validity and reliability of a new scale. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 35, 209–220. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160‐008‐9022‐2

- Cafri, G., Thompson, J. K., Roehrig, M., van den Berg, P., Jacobsen, P. B., & Stark, S. (2006b). An investigation of appearance motives for tanning: The development and evaluation of the Physical Appearance Reasons For Tanning Scale (PARTS) and its relation to sunbathing and indoor tanning intentions. Body Image, 3(3), 199–209. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2006.05.002

- Cho, H., Lee, S., & Wilson, K. (2010). Mazagine exposure, tanned women stereotypes, and tanning attitudes. Body Image, 7, 364–367. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.04.002

- Choi, K., Lazovich, D., Southwell, B., Forster, J., Rolnick, S. J., & Jackson, J. (2010). Prevalence and characteristics of indoor tanning use among men and women in the United States. Archives of Dermatology, 146, 1356–1361. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/archdermatol.2010.355

- Dixon, H., Borland, R., & Hill, D. (1999). Sun protection and sunburn in primary school children: The influence of age, gender, and coloring. Preventive Medicine, 28, 119–130.

- Dixon, H., Dobbinson, S. J., Wakefield, M. A., Jamsen, K., & Mcleod, K. (2008). Portrayal of tanning, clothing fashion and shade use in Australian women's magazines, 1987–2005. Health Education Research, 23, 791–802. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cym057

- Dixon, H., Warne, C. D., Scully, M. L., Wakefield, M. A., & Dobbinson, S. J. (2011). Does the portrayal of tanning in Australian women's magazines relate to real women's tanning beliefs and behavior? Health Education & Behavior, 38, 132–142. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198110369057

- Dobbinson, S. J., Wakefield, M. A., Jamsen, K. M., Herd, N. L., Spittal, M. J., Lipscomb, J. E., & Hill, D. J. (2008). Weekend sun protection and sunburn in Australia trends (1987–2002) and association with SunSmart television advertising. [Research Support, Non‐U.S. Gov't]. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 34(2), 94–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.024

- Francis, K., Dobbinson, S. J., Wakefield, M. A., & Girgis, A. (2010). Solarium use in Australia, recent trends and context. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 34, 427–430.

- Groesz, L. M., Levine, M. P., & Murnen, S. K. (2002). The effect of experimental presentation of thin media images on body satisfaction: A meta‐analytic review. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 31, 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10005

- Grogan, S. (2008). Body image: Understanding body dissatisfaction in men, women, and children (2nd ed.). London and New York: Routledge.

- Hillhouse, J. J., Stair, A. W., & Adler, C. M. (1996). Predictors of sunbathing and sunscreen use in college undergraduates. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 19, 543–561.

- Howell, D. C. (1992). Statistical methods for psychology (3rd ed.). Boston, MA: PWS‐KENT Publishing Company.

- Hussein, M. R. (2005). Ultraviolet radiation and skin cancer: Molecular mechanisms. Journal of Cutaneous Pathology, 32(3), 191–205. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0303‐6987.2005.00281.x

- Jackson, K. M., & Aiken, L. S. (2000). A psychosocial model of sun protection and sunbathing in young women: The impact of health beliefs, attitudes, norms, and self‐efficacy for sun protection. Health Psychology, 19(5), 469–478.

- Jalleh, G., Donovan, R. J., Lin, C., & Slevin, T. (2008). Changing perceptions of solaria and cancer risk: The role of the media. Medical Journal of Australia, 188, 735.

- Keesling, B., & Friedman, H. S. (1987). Psychosocial factors in sunbathing and sunscreen use. Health Psychology, 6, 477–493. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0278‐6133.6.5.477

- Leary, M. R., & Jones, J. L. (1993). The social psychology of tanning and sunscreen use: Self‐presentational motives as a predictor of health risk. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 23, 1390–1406.

- Narayanan, D. L., Saladi, R. N., & Fox, J. L. (2010). Ultraviolet radiation and skin cancer. International Journal of Dermatology, 49(9), 978–986. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365‐4632.2010.04474.x

- Potente, S., Coppa, K., Williams, A., & Engels, R. (2011). Legally brown: Using ethnographic methods to understand sun protection attitudes and behaviours among young Australians ‘I didn't mean to get burnt—it just happened!’. Health Education Research, 26, 39–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyq066

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. doi:https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

- Sahn, R. E., Mcilwain, M. J., Magee, K. H., Veledar, E., & Chen, S. (2012). A cross‐sectional study examining the correlation between sunless tanning product use and tanning beliefs and behaviors. Archives of Dermatology, 148, 448–454. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/archdermatol.2011.2072

- Shih, S. T.‐F., Carter, R., Sinclair, C., Mihalopoulos, C., & Vos, T. (2009). Economic evaluation of skin cancer prevention in Australia. Preventive Medicine, 49, 449–453. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.09.008

- Stanton, W. R., Janda, M., Baade, P. D., & Anderson, P. (2004). Primary prevention of skin cancer: A review of sun protection in Australia and internationally. Health Promotion International, 19, 369–378. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dah310

- Stice, E., Maxfield, J., & Wells, T. (2003). Adverse effects of social pressure to be thin on young women: An experimental investigation of the effects of ‘fat talk’. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 34, 108–117.

- Stunkard, A. J., Sorenson, T., & Schlusinger, F. (1983). Use of the Danish adoption registers for the study of obesity and thinness. In S. S. Kety, L. P. Rowland, R. L. Sidman, & S. W. Matthysse (Eds.), The genetics of neurological and psychological disorders (pp. 115–120). New York: Raven Press.

- Thompson, J. K., & Altabe, M. N. (1991). Psychometric qualities of the Figure Rating Scale. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 5, 615–619. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/1098‐108X(199109)10:5<615:AID‐EAT2260100514>3.0.CO;2‐K

- Thompson, J. K., Heinberg, L. J., Altabe, M., & Tantleff‐dunn, S. (1999). Exacting beauty: Theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Wichstrøm, L. (1994). Predictors of Norwegian adolescents' sunbathing and use of sunscreen. Health Psychology, 13, 412–420. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0278‐6133.13.5.412