Abstract

Cognitive‐behavioural models suggest that perfectionistic beliefs and anticipatory processing are key maintaining factors of social anxiety. The present study examined the moderating and mediating role that anticipatory processing has on the relationship between perfectionism and social anxiety. The sample consisted of 245 individuals from the general community who completed an online questionnaire package comprising depression, perfectionism, and social anxiety measures. Participants also rated their levels of anticipatory processing in response to vignettes describing an upcoming social interaction and performance situation. Results showed that maladaptive perfectionism and maladaptive anticipatory processing were positively associated with social anxiety. Furthermore, maladaptive anticipatory processes (stagnant deliberation and outcome fantasy) remained significantly and positively associated with social anxiety even after controlling for depression and maladaptive perfectionism, whereas adaptive anticipatory processes (plan rehearsal and problem analysis) were not significantly associated with social anxiety. These findings support current classifications of anticipatory processing in social anxiety. Contrary to predictions, maladaptive anticipatory processing did not moderate the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and social anxiety. An exploratory analysis indicated that maladaptive anticipatory processing mediated the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and social anxiety. Implications for therapeutic intervention are discussed.

In its most severe form, social anxiety meets the clinical diagnosis for social phobia, which is defined as a ‘marked and persistent fear of social or performance situations in which embarrassment may occur’ (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2000, p. 411). Social phobia has a 12‐month prevalence of between 1.2% and 7.2% and a lifetime prevalence of between 2.3% and 7.3% (Alonso et al., Citation2004; Lampe, Slade, Issakidis, & Andrews, Citation2003), is highly comorbid with a range of mental disorders (Chartier, Walker, & Stein, Citation2003), and has a significant impact on social and occupational functioning (Waghorn, Chant, & Whiteford, Citation2005).

According to cognitive‐behavioural models (Clark & Wells, Citation1995; Heimberg, Brozovich, & Rapee, Citation2010), perfectionistic beliefs and anticipatory processing are key maintaining factors of social anxiety. As predicted by these models, there is a robust positive association between maladaptive perfectionism and social anxiety (Antony, Purdon, Huta, & Swinson, Citation1998; Frost & DiBartolo, Citation2002; Jain & Sudhir, Citation2010; Juster et al., Citation1996), and a positive association between anticipatory processing and social anxiety (Hinrichsen & Clark, Citation2003; Vassilopoulos, Citation2004, Citation2008; Wong & Moulds, Citation2011). However, few studies have examined these constructs simultaneously, and it remains unclear how these constructs are related in the context of social anxiety.

Perfectionism and social anxiety

Perfectionism is a personality disposition, which encompasses the tendency to strive for flawless performance, set excessively high performance standards, engage in critical self‐evaluation, and be intolerant to errors. In Clark and Wells's (Citation1995) model, excessively high performance standards are a dysfunctional belief endorsed by socially anxious individuals typified by cognitions such as: ‘I must get everyone's approval’ and ‘I must not let anyone see I am anxious’. During anticipatory, in‐situation, and post‐event processing of a social situation, performance is evaluated against high standard beliefs. As high standard beliefs are difficult, if not impossible, to achieve, they are associated with cognitive (e.g., negative self statements) behavioural (e.g., avoiding eye contact) and physical (e.g., sweating) symptoms of anxiety.

Similarly, in Heimberg et al.'s (Citation2010) model, socially anxious individuals endorse high standard beliefs and have lowered self‐efficacy. When a social situation is anticipated, encountered, or retrospectively ruminated upon, socially anxious individuals form a mental representation of the audience's perception of their performance and compare this to an appraisal of the audience's expected performance standards. A negative discrepancy is perceived; therefore, negative audience evaluation is expected. This elicits cognitive, behavioural, and physical symptoms of anxiety which further contribute to a negative perception of their performance as seen by the audience, which in turn renews the cycle of social anxiety.

These cognitive‐behavioural models suggest that rather than having high personal standards, socially anxious individuals believe that others have high expectations for their social performance. A number of studies using the Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (Frost, Marten, Lahart, & Rosenblate, Citation1990) found that relative to non‐clinical controls, individuals with social phobia scored higher on concern over mistakes, doubts about actions, and parental criticism sub‐scales, while no significant difference in the personal standards sub‐scale has been found (Antony et al., Citation1998; Frost & DiBartolo, Citation2002; Jain & Sudhir, Citation2010; Juster et al., Citation1996). Furthermore, preliminary evidence suggests that post‐treatment reductions in concern over mistakes and doubts about actions predict post‐treatment reductions in social anxiety (Ashbaugh et al., Citation2007).

Anticipatory processing in social anxiety

In order to deal with the anxiety that accompanies high standard beliefs, individuals with social anxiety engage in a range of metacognitive processes and safety behaviours including anticipatory processing. Anticipatory processing is an important stage of coping that involves preparing and reviewing potential outcomes of an upcoming stressful situation and dwelling on avoidance strategies (Aspinwall & Taylor, Citation1997). For socially anxious individuals, anticipatory processing is typically ‘dominated by recollections of past failures, by negative images of themselves during the event, and by other predictions of poor performance and rejection’ (Clark & Wells, Citation1995, p. 74). Furthermore, anticipatory processing may also set the stage for future coping strategies such as post‐event processing, which is a repetitive thinking process that involves reviewing negative thoughts and feelings experienced during the social situation (Grant & Beck, Citation2010).

As cognitive‐behavioural models conceptualise anticipatory processing as unitarily maladaptive, the methodology of several studies have reflected this presupposition (Hinrichsen & Clark, Citation2003; Vassilopoulos, Citation2004; Wong & Moulds, Citation2009, Citation2011). Taken together, these studies showed that engagement in anticipatory processing was maladaptive as it heightened anxiety, and involved recalling past perceived failures and dwelling on avoidance strategies.

By contrast, several studies have demonstrated that both adaptive and maladaptive anticipatory processes can be harnessed when coping with upcoming stressful situations. Anticipatory processes such as avoiding the details of the problem and perseverative thinking have been found to be associated with psychological distress (Belzer, D'Zurilla, & Maydeu‐Olivares, Citation2002; Davis & Nolen‐Hoeksema, Citation2000; Dunkley, Blankstein, Halsall, Williams, & Winkworth, Citation2000; Feldman & Hayes, Citation2005; Weiner & Carton, Citation2012), whereas anticipatory processes such as mental simulation and rational problem solving have been found to be associated with adaptive mental health outcomes (Aspinwall & Taylor, Citation1997; Feldman & Hayes, Citation2005).

Feldman and Hayes's (Citation2005) suggested that maladaptive anticipatory processing is characterised by ruminating and experiencing unproductive thoughts about a stressful life problem (i.e., stagnant deliberation), and responding to potential problems by daydreaming or fantasising about desired outcomes while ignoring other details of the problem‐solving process (i.e., outcome fantasy). Conversely, adaptive anticipatory processing involves envisioning steps and strategies to achieve desired outcomes (i.e., plan rehearsal), and the contemplation of the antecedents and meaning of future stressful events (i.e., problem analysis). As predicted, Feldman and Hayes found that maladaptive anticipatory processing was positively associated with cognitive inflexibility, avoidant problem solving, perseverative thought, anxiety, and depression. Additionally, adaptive anticipatory processing was positively associated with cognitive flexibility, rational problem solving, positive problem‐solving orientation, and was not significantly associated with anxiety and depression.

More specific to social anxiety, Vassilopoulos (Citation2008) found that individuals with high social anxiety (n = 24) were more likely than low socially anxious individuals (n = 22) to engage in stagnant deliberation but not outcome fantasy. Findings also showed no significant differences between groups in adaptive anticipatory processes (plan rehearsal and problem analysis). These findings were partially consistent with Feldman and Hayes's (Citation2005) findings that both stagnant deliberation and outcome fantasy were associated with anxiety and depression. In other words, Vassilopoulos' findings suggest that stagnant deliberation might be particularly problematic for social anxiety, whereas outcome fantasy may be problematic for anxiety in general. It is nonetheless still possible that the association between outcome fantasy and social anxiety may be significant in a larger sample.

Additionally, Vassilopoulos's (Citation2008) did not control for depression despite emerging evidence that depression is associated with anticipatory processing (Feldman & Hayes, Citation2005). Both depression and social anxiety are characterised by repetitive thinking styles (brooding and stagnant deliberation, respectively). Brooding involves negative self‐reflection that focuses on abstract ‘why me’ issues and obstacles to overcoming problems (e.g., ‘Why can't I handle problems better?’; Nolen‐Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubomirsky, Citation2008). Stagnant deliberation involves dwelling on a specific and upcoming stressful problem that leads to pessimistic performance expectations (e.g., ‘I think about the problem without making progress on it’; Feldman & Hayes, Citation2005). Due to the apparent similarity between these constructs, it is integral that depression is controlled for when examining anticipatory processing in social anxiety.

Perfectionism and anticipatory processing in social anxiety

Cognitive‐behavioural models suggest that maladaptive perfectionism (high standard beliefs) influence anticipatory processing in social anxiety; during anticipatory processing, socially anxious individuals perceive a large discrepancy between an appraisal of their performance and their performance standards (Clark & Wells, Citation1995; Heimberg et al., Citation2010). Consistent with these models, preliminary evidence suggests that maladaptive self‐beliefs (high standard, conditional, and unconditional beliefs) may be situation‐specific and particularly important during anticipatory processing (Wong & Moulds, Citation2009, Citation2011). In an experimental study, Wong and Moulds's (Citation2011) randomly allocated 80 high and low socially anxious participants to anticipatory processing or distraction conditions prior to a social‐evaluative task. They found that all participants in the anticipatory processing condition (relative to distraction) experienced greater self‐reported anxiety. Furthermore, for the high (but not low) social anxiety participants, anticipatory processing resulted in increased skin conductance and endorsement of high standard and conditional beliefs. These findings suggest that a positive association between maladaptive perfectionism and social anxiety might be particularly strong in individuals who engaged in maladaptive anticipatory processing. In other words, it appeared that maladaptive anticipatory processing might moderate the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and social anxiety. However, additional research is required to further investigate this association as findings may inform clinical intervention.

Aims and hypotheses

In line with cognitive‐behavioural models of social anxiety, the overarching aim was to investigate the role of maladaptive perfectionism and anticipatory processing in social anxiety. This study also sought to extend and clarify inconsistencies in previous anticipatory processing research (Feldman & Hayes, Citation2005; Vassilopoulos, Citation2008). The association between social anxiety and maladaptive anticipatory processing (stagnant deliberation and outcome fantasy) was re‐examined with a larger sample size, while controlling for depression and maladaptive perfectionism. Lastly, based on preliminary findings (Wong & Moulds, Citation2011), this study aimed to examine the moderating influence of maladaptive anticipatory processing on the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and social anxiety.

It was hypothesised that: (1) stagnant deliberation and outcome fantasy (not plan rehearsal and problem analysis) would be significantly positively associated with social anxiety even after controlling for depression and maladaptive perfectionism, and (2) stagnant deliberation and outcome fantasy would moderate the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and social anxiety, even after controlling for depression.

Method

Participants

A total of 371 participants commenced the survey. However, only 245 participants aged between 18 and 63 years (M = 29.65, SD = 12.44) completed all scales in the online survey. Of these participants, 166 were females and 78 were males; one participant failed to specify gender. There were no significant differences between dropouts and completers in age, t(368) = −.33, p > .05, gender, χ2 (1) = .07, p > .05, ethnicity, χ2 (1) = .28, p > .05, highest level of education attained, χ2 (4) = .91, p > .05, marital status, χ2 (3) = 1.17 p > .05, or employment status, χ2 (3) = 6.38, p > .05. Participants were recruited via a Facebook group, talks during undergraduate psychology lectures, and advertisements posted around university campuses. Participants were not paid for their participation; however, they were given the opportunity to enter a draw to win an iPad3.

Materials

The following measures were used in the study.

The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale‐Self Report (LSAS‐SR; Fresco et al., Citation2001) is a 24‐item self‐report measure that contains social interaction and performance situation items. For each item, participants indicate their general levels of fear and avoidance on two separate 4‐point Likert scales ranging from 0 (none and never, respectively) to 3 (severe and usually, respectively). The LSAS‐SR has excellent internal consistency (Cronbach's α = .97; Weeks, Heimberg, Rodebaugh, Goldin, & Gross, Citation2011), and adequate convergent validity (r = .61–.71) and discriminant validity (Fresco et al., Citation2001).

The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale‐21 (DASS‐21; Lovibond & Lovibond, Citation1995) is a 21‐item self‐report measure that contains three sub‐scales: depression, anxiety, and stress. Participants rated how each item ‘applied to me over the past week’ on a 4‐point Likert scale ranging from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much or most of the time). Only the DASS‐depression sub‐scale was used and a total score was calculated by summing item values and multiplying the score by 2. The DASS‐depression sub‐scale has good internal consistency (Cronbach's α = .82), and good convergent and discriminant validity (Henry & Crawford, Citation2005).

The Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (FMPS; Frost et al., Citation1990) is a 35‐item self‐report measure that contains six sub‐scales: concern over mistakes, doubts about actions, personal standards, parental expectations, parental criticism, and organisation. Participants indicated what best reflected their opinion on each item on a 5‐point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Consistent with previous studies, a total FMPS‐maladaptive perfectionism score was calculated by summing item values on concern over mistakes, doubts about actions, and parental criticism sub‐scales (Antony et al., Citation1998). The FMPS has excellent convergent validity (Frost, Heimberg, Holt, Mattia, & Neubauer, Citation1993) and good internal consistency for relevant sub‐scales (Cronbach's α; concern over mistakes = .88, doubts about actions = .77, and parental criticism = .84; Frost et al., Citation1990).

The Measure of Mental Anticipatory Processes (MMAP; Feldman & Hayes, Citation2005) is a 15‐item self‐report measure that contains two sub‐scales measuring maladaptive anticipatory processes: stagnant deliberation and outcome fantasy, and two sub‐scales measuring adaptive anticipatory processes: plan rehearsal and problem analysis. The instructions of the MMAP were adapted in the current study; instead of asking participants to imagine an important, difficult and stressful problem, we asked participants to imagine themselves preparing for a social interaction and performance situation using Vassilopoulos's (Citation2008) vignettes, and to rate their typical responses on a 5‐point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never true for me) to 5 (always true for me) (see Appendix). The total scores for each sub‐scale were calculated by summing relevant item values for both vignettes. The MMAP has good internal consistency (Cronbach's α = .81; Vassilopoulos, Citation2008), satisfactory temporal stability over a 4‐week interval (Pearson's r = .61–.70; range of four sub‐scales) and satisfactory factorial stability (Feldman & Hayes, Citation2005).

In this study, all measures demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach's α ranged from .81 to .92; see Table ).

Table 1. Intercorrelations, means, standard deviations, and Cronbach's α for measures of social anxiety, depression, maladaptive perfectionism, and anticipatory processing (N = 240)

Procedure

Following university ethics approval, a Facebook group was created that used word‐of‐mouth and snowballing methods to invite participants to complete the survey, which was administered online using Qualtrics.com. Prior to commencing the survey, participants were informed that the survey would take approximately 30-min to complete, and could be saved and recommenced at a later time (24 participants recommenced the survey). The participants completed the LSAS‐SR, DASS‐21, and FMPS self‐report measures. Next, participants read the social interaction and performance vignettes (Vassilopoulos, Citation2008) that were designed to elicit anticipatory processing by exposing participants to the possibility of being in a future anxiety‐provoking social interaction or performance situation (see Appendix). Participants were required to complete the MMAP after reading each vignette. Upon completion, participants were given the opportunity to enter a draw to win an iPad3. The study was conducted as part of the first author's honours thesis and therefore, time restrictions applied to the data collection period which occurred between July and October 2012.

Data analysis

Pearson product‐moment correlations were conducted to assess the relationships between independent variables (DASS‐depression, FMPS‐maladaptive perfectionism, and MMAP sub‐scales) and the dependent variable (LSAS‐SR‐social anxiety). A two‐step hierarchical regression analysis with LSAS‐SR‐social anxiety as the dependent variable was conducted to assess predictors of social anxiety. DASS‐depression and FMPS‐maladaptive perfectionism were entered in the first step, and MMAP sub‐scales were entered in the second step.

Two separate three‐step hierarchical multiple regression analyses were conducted to assess the moderating effect of maladaptive anticipatory processing on the relationship between FMPS‐maladaptive perfectionism and LSAS‐SR‐social anxiety. Continuous predictor variables were centred prior to analysis (Aiken & West, Citation1991). In the first analysis, DASS‐depression was entered in the first step, FMPS‐maladaptive perfectionism and MMAP‐stagnant deliberation were entered in the second step, and the product term between FMPS‐maladaptive perfectionism and MMAP‐stagnant deliberation was entered in the third step. In the second analysis, DASS‐depression was entered in the first step, FMPS‐maladaptive perfectionism and MMAP‐outcome fantasy were entered in the second step, and the product term between FMPS‐maladaptive perfectionism and MMAP‐outcome fantasy was entered in the third step.

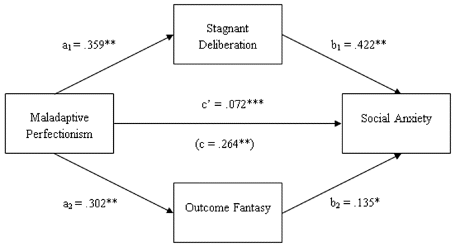

Based on results from the regression analyses, an exploratory analysis was also conducted to examine a multiple mediation model (see Fig. 1). A bootstrapping procedure was conducted to examine the indirect effects using Preacher and Hayes (Citation2008) multiple mediation analyses SPSS script (SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY, USA). As recommended by Preacher and Hayes, 5,000 bootstrapping samples and 95% biased corrected and accelerated confidence intervals (CIs) were used for all analyses. FMPS‐maladaptive perfectionism was the independent variable, and LSAS‐SR social anxiety was the dependent variable. Maladaptive anticipatory processes (MMAP‐stagnant deliberation and MMAP‐outcome fantasy) were the mediators. As with the previous multiple regression analyses, depression was entered as a covariate.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Means and standard deviations for each variable were calculated. Square root transformations of LSAS‐SR‐social anxiety, FMPS‐maladaptive perfectionism and MMAP‐stagnant deliberation, and a log 10 transformation of DASS‐depression improved the normality and reduce outliers. Examination of boxplots post transformation indicated the presence of five outliers that were beyond 1.5 times of the interquartile range. These outliers were removed. Based on previous research, medium to large effect sizes were expected (Jain & Sudhir, Citation2010). A post‐hoc power analysis conducted using GPower 3.1 (Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner, & Lang, Citation2009) showed that the power to detect medium effect sizes in the multivariate regressions (including the interaction effects) in the current study was above .99 for all hypotheses, given a sample size of 240 and an alpha of .05.

The majority of participants were employed (80.01%) and unmarried (65.31%). The means, standard deviations, and person's correlations between variables are presented in Table . LSAS‐SR‐social anxiety was strongly and positively correlated with DASS‐depression, FMPS‐maladaptive perfectionism, MMAP‐stagnant deliberation, and MMAP‐outcome fantasy. There were no significant associations between LSAS‐SR‐social anxiety and both MMAP‐plan rehearsal and MMAP‐problem analysis. Results indicated a strong positive association between FMPS‐maladaptive perfectionism and MMAP‐stagnant deliberation, and a moderate positive association between FMPS‐maladaptive perfectionism and MMAP‐outcome fantasy.

Prediction of social anxiety

Step 1 of the hierarchical regression analysis indicated DASS‐depression and FMPS‐maladaptive perfectionism were significant positive predictors of LSAS‐SR‐social anxiety (see Table ). DASS‐depression remained a positive predictor of LSAS‐SR‐social anxiety when MMAP anticipatory processing sub‐scales were added in the second step, whereas FMPS‐maladaptive perfectionism was no longer a significant predictor. Step 2 indicated a significant increase in R2 with the addition of MMAP sub‐scales, and only DASS‐depression, MMAP‐stagnant deliberation, and MMAP‐outcome fantasy significantly contributed to the variance in the final model.

Table 2. Summary of hierarchical multiple regression analysis for variables predicting social anxiety (N = 240)

Moderating effect of maladaptive anticipatory processing

Two separate regression analyses were conducted to test the moderating effects of stagnant deliberation and outcome fantasy. In the first analysis, results indicated that the interaction between FMPS‐maladaptive perfectionism and MMAP‐stagnant deliberation did not significantly contribute to the variance in the final model, ΔR2 = .00, ΔF(1, 235) = .37, p = .54. In the second analysis, results indicated the interaction between FMPS‐maladaptive perfectionism and MMAP‐outcome fantasy did not significantly contribute to the variance in the final model, ΔR2 = .00, ΔF(1, 235) = .06, p = .80.

Exploratory analysis: A multiple mediation model

Results from the regression analyses indicated that the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and social anxiety was no longer significant after controlling for maladaptive anticipatory processing. These findings suggested that the effect of maladaptive perfectionism on social anxiety occurred because of the indirect effects of maladaptive anticipatory processing. Although a mediation model was not hypothesised when designing the study, we decided to conduct an exploratory analysis to evaluate this possibility (see Fig. 1).

A summary of the bootstrapping procedure results is presented in Table . As bootstrapping does not impose distributional assumptions (Preacher & Hayes, Citation2008), non‐transformed data including outliers were used. Findings indicated significant total indirect effects of maladaptive anticipatory processing and significant indirect effects for both stagnant deliberation and outcome fantasy. Although the total effect of maladaptive perfectionism on social anxiety (c) was significant (p < .001), the direct effect (c') was no longer significant (p = .22) after accounting for indirect effects, indicating that maladaptive anticipatory processing mediated the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and social anxiety. Although the direct effect (c') is small, it is not zero, and the percentages of the total effect mediated by stagnant deliberation and outcome fantasy were 57.4% and 15.4%, respectively (Ambler, Citation1998).

Table 3. Summary of the mediation of the effect of maladaptive perfectionism on social anxiety through stagnant deliberation and outcome fantasy while controlling for depression (N = 245)

Discussion

The results supported the first hypothesis. Maladaptive (not adaptive) anticipatory processing uniquely predicted social anxiety, even after controlling for depression and maladaptive perfectionism. Contrary to the second hypothesis, maladaptive anticipatory processing did not moderate the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and social anxiety. Interestingly, the exploratory analysis showed that when controlling for depression, maladaptive anticipatory processing mediated the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and social anxiety. Collectively, these findings highlight the important role of anticipatory processing in social anxiety.

Anticipatory processing and social anxiety

Consistent with Hypothesis 1 when controlling for depression and maladaptive perfectionism, maladaptive (not adaptive) anticipatory processes uniquely predicted social anxiety. This key finding has significant theoretical and clinical implications. First, utilisation of the MMAP scale to measure anticipatory processes clarified inconsistencies in previous research (Feldman & Hayes, Citation2005; Vassilopoulos, Citation2008), and supported Feldman and Hayes's (Citation2005) finding that both stagnant deliberation and outcome fantasy were associated with social anxiety and depression. Second, the present study's finding extends Vassilopoulos's (Citation2008) study by showing that maladaptive anticipatory processes uniquely predict social anxiety while controlling for depression. In other words, the association between maladaptive anticipatory processes and social anxiety is not just a result of depressed mood. Lastly, this finding supports the wider literature that has demonstrated that perseverative thought (Davis & Nolen‐Hoeksema, Citation2000; Feldman & Hayes, Citation2005), and avoidance of the details of the problem (Belzer et al., Citation2002; Dunkley et al., Citation2000; Feldman & Hayes, Citation2005; Weiner & Carton, Citation2012) are maladaptive anticipatory processes associated with psychopathology.

Our findings highlight the importance of targeting anticipatory processing during treatment intervention. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for social anxiety targets underlying beliefs and habitual patterns of responding. Perhaps, in addition to assisting socially anxious individuals reduce engagement in maladaptive anticipatory processing, there may be benefits in training adaptive coping skills (plan rehearsal and problem analysis). Teaching plan rehearsal may involve assisting individuals to envision steps and strategies that could be used to achieve social performance outcomes (e.g., smiling and making eye contact). Teaching effective problem solving may involve assisting clients to accurately define the problem and analysing the factors that contribute to the situation (D'Zurilla & Nezu, Citation2001).

Alternatively, it may be more effective to implement mindfulness and acceptance‐based therapies such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, Citation1999). Feldman, Hayes, Kumar, Greeson, and Laurenceau's (Citation2007) key study demonstrated that greater mindfulness was associated with greater cognitive flexibility and adaptive anticipatory processing, and lower anxiety and maladaptive anticipatory processes. However, the magnitude of the association of mindfulness with cognitive flexibility was found to be greater than the association with adaptive anticipatory processing. Collectively, these findings suggest that mindfulness may be distinct from analytical modes of thought, and may be better classified by the tendency to approach problems ‘without relying on habitual response sets’ (Feldman et al., Citation2007, p. 185). Thus, mindfulness‐based interventions targeting anticipatory processing may be more effective than challenging the content of beliefs or training habitual response sets such as adaptive anticipatory processing. Future research is required to examine this further.

Influence of anticipatory processing on perfectionism in social anxiety

Our findings showed that maladaptive anticipatory processing (stagnant deliberation and outcome fantasy) was positively associated with maladaptive perfectionism. However, contrary to Hypothesis 2, maladaptive anticipatory processing did not moderate the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and social anxiety. Interestingly, further inspection of the regression analyses indicated that the addition of maladaptive anticipatory processes rendered maladaptive perfectionism no longer a significant predictor of social anxiety. Although not hypothesised, these findings suggested that the effect of maladaptive perfectionism on social anxiety occurred because of the indirect effects of maladaptive anticipatory processing.

Subsequently, a multiple mediation model (see Fig. 1) was explored. To the author's knowledge, the present study is the first to show that maladaptive anticipatory processing (both stagnant deliberation and outcome fantasy) mediated the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and social anxiety. This exploratory finding is consistent with Wong and Moulds's (Citation2011) study which found socially anxious individuals' engagement in anticipatory processing led to greater endorsement of high standard beliefs, and Dunkley et al. (Citation2000) study that found avoidant coping (disengagement from the details of problems), mediated the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism (concern over mistakes and doubts about actions) and psychological distress (anxiety and depression).

In addition, this finding is consistent with the ACT model of psychopathology which suggests that experiential avoidance contributes to cognitive inflexibility which in turn maintains psychopathology (Hayes et al., Citation1999). Socially anxious individuals' engagement in maladaptive anticipatory processing involves futile attempts in controlling upcoming social situations in order to avoid experiencing distressing bodily sensations, emotions, and thoughts. An emerging body of evidence suggests that mindfulness‐based interventions that promote receptive and flexible moment‐to‐moment experience may have clinically significant outcomes for socially anxious individuals (Dalrymple & Herbert, Citation2007; Goldin & Gross, Citation2010; Koszycki, Benger, Shlik, & Bradwejn, Citation2007). If the present study's findings are supported by future research, it may indicate that mindfulness‐based interventions addressing maladaptive anticipatory processing might have a more direct and immediate impact on social anxiety than interventions that involve challenging the content of maladaptive perfectionistic beliefs.

Limitations and directions for future research

The present study is cross‐sectional; therefore casual relationships between variables cannot be inferred, and results from the exploratory mediation analysis should be interpreted with considerable caution. Sixty‐six per-cent of participants who commenced the survey successfully completed it. The remaining 34% were considered dropouts, which may have introduced sampling bias. Dropouts may have been due to survey length (Hoerger, Citation2010), or failure to include an indication of the percentage of the survey completed as motivation to continue. However, post‐hoc analyses indicate no significant differences in age, gender, level of education attained, marital status, or employment status between dropouts and completers.

A major limitation concerns the difficultly in ascertaining whether vignettes elicited experiential anticipatory processing, or whether previous experiences of anticipatory processing were recalled as there were no checks to ensure participants responded after reflecting on the vignettes. Findings are, therefore, subject to recall bias. Future research is recommended where participants are asked to engage in a social task (e.g., speech or social interaction task) so that that experiential anticipatory processing is more likely to be elicited.

Several limitations were associated with the online administration of the survey. First, the validity and reliability of the online administration of the original pen‐and‐paper‐based measures have not been subject to psychometric evaluation. Second, online administration may have introduced sampling bias as participation required Internet access. Evidence suggests there are significant differences between the Internet user population and the general population in age, gender, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity (see Couper, Citation2000, for a review). Replication with alternative methods of data collection (e.g., observer ratings and diaries) is recommended.

Facebook recruitment methods may also have introduced sampling bias. Evidence suggests compared to non‐users, Facebook users are more likely to be younger, have higher levels of extraversion and neuroticism, and lower levels of shyness, conscientiousness, and loneliness (Correa, Hinsley, & de Zúñiga, Citation2010; Ryan & Xenos, Citation2011). Furthermore, Facebook samples may include an over‐representation of individuals with numerous social connections who share similar characteristics (Magnani, Sabin, Saidel, & Heckathorn, Citation2005). Future research is recommended to reconsider Facebook recruitment methods, and to examine results in different socioeconomic and age groups, and within clinical populations.

Conclusions

In sum, this study contributes to current understandings of maladaptive perfectionism and anticipatory processing, which are key maintaining factors of social anxiety. Findings support current classifications of adaptive (plan rehearsal and problem analysis) and maladaptive (stagnant deliberation and outcome fantasy) anticipatory processing. Furthermore, findings indicated that maladaptive anticipatory processes mediated the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and social anxiety, which has significant clinical implications.

References

- Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Alonso, J., Angermeyer, M. C., Bernert, S., Bruffaerts, R., Brugha, T. S., Bryson, H, … Volleberg, W. A. M. (2004). 12‐month comorbidity patterns and associated factors in Europe: Results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 109(s420), 28–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600‐0047.2004.00328.x

- Ambler, T. (1998). Mediation and moderation: Rules and tests. Pan ‘Agra Working Paper no. 98–904. London: London Business School.

- American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., Text Rev). Washington, DC: Author.

- Antony, M. M., Purdon, C. L., Huta, V., & Swinson, R. P. (1998). Dimensions of perfectionism across the anxiety disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36(12), 1143–1154. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005‐7967(98)00083‐7

- Ashbaugh, A., Antony, M. M., Liss, A., Summerfelt, L. J., Mccabe, R. E., & Swinson, R. P. (2007). Changes in perfectionism following cognitive‐behavioural treatment for social phobia. Depression and Anxiety, 24, 169–177. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20219

- Aspinwall, L. G., & Taylor, S. E. (1997). A stitch in time: Self‐regulation and proactive coping. Psychological Bulletin, 121(3), 417–436. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033‐2909.121.3.417

- Belzer, K. D., D'zurilla, T. J., & Maydeu‐olivares, A. (2002). Social problem‐solving and trait anxiety as predictors of worry in a college student population. Personality and Individual Differences, 33(4), 573–585.

- Chartier, M. J., Walker, J. R., & Stein, M. B. (2003). Considering comorbidity in social phobia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 38, 728–734. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127‐003‐0720‐6

- Clark, D. M., & Wells, A. (1995). A cognitive model of social phobia. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Correa, T., Hinsley, A. W., & de Zúñiga, H. G. (2010). Who interacts on the Web?: The intersection of users' personality and social media use. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(2), 247–253. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.09.003

- Couper, M. P. (2000). Web surveys: A review of issues and approaches. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 64(4), 464–494. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3078739

- Dalrymple, K. L., & Herbert, J. D. (2007). Acceptance and commitment therapy for generalised social anxiety disorder: A pilot study. Behavior Modification, 31, 543–568. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445507302037

- Davis, R. N., & Nolen‐hoeksema, S. (2000). Cognitive inflexibility among ruminators and nonruminators. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 24(6), 699–711.

- Dunkley, D. M., Blankstein, K. R., Halsall, J., Williams, M., & Winkworth, G. (2000). The relation between perfectionism and distress: Hassles, coping, and perceived social support as mediators and moderators. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47(4), 437–453. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/AW22‐0167.47.4.437

- D'zurilla, T. J., & Nezu, A. M. (2001). Problem‐solving therapies. In K. S. Dobson (Ed.), Handbook of cognitive‐behavioral therapies (2nd ed., pp. 211–245). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.‐G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 1149–1160. doi:https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

- Feldman, G., & Hayes, A. (2005). Preparing for problems: A measure of mental anticipatory processes. Journal of Research in Personality, 39, 487–516. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2004.05.005

- Feldman, G., Hayes, A., Kumar, S., Greeson, J., & Laurenceau, J.‐P. (2007). Mindfulness and emotion regulation: The development and initial validation of the Cognitive Affective Mindfulness Scale‐Revised (CAMS‐R). Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 29, 177–190. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862‐006‐9035‐8

- Fresco, D. M., Coles, M. E., Heimberg, R. G., Liebowitz, M. R., Hami, S., Stein, M. B., & Goetz, D. (2001). The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale: A comparison of the psychometric properties of self‐report and clinician‐ administered formats. Psychological Medicine, 31, 1025–1035. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291701004056

- Frost, R. O., & Dibartolo, P. M. (2002). Perfectionism, anxiety, and obsessive compulsive disorder. In G. L. Flett & P. L. Hewitt (Eds.), Perfectionism: Theory, research, and treatment (pp. 341–371). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Frost, R. O., Marten, P., Lahart, C., & Rosenblate, R. (1990). The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14, 449–468. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01172967

- Frost, R. O., Heimberg, R. G., Holt, C. S., Mattia, J. I., & Neubauer, A. L. (1993). A comparison of two measures of perfectionism. Personality and Individual Differences, 14, 119–126. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0191‐8869(93)90181‐2

- Goldin, P. R., & Gross, J. J. (2010). Effects of Mindfulness‐based Stress Reduction (MBSR) on emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder. Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 10, 83–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037//a001844

- Grant, D. M., & Beck, J. G. (2010). What predicts the trajectory of rumination?: A prospective evaluation. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 24(5), 480–486. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.03.004

- Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Heimberg, R. G., Brozovich, F. A., & Rapee, R. M. (2010). A cognitive behavioural model of social anxiety disorder: Update and extension. In S. G. Hofmann & P. M. Dibartolo (Eds.), Social anxiety: Clinical, developmental, and social perspectives (pp. 396–423). London: Academic Press.

- Henry, J. D., & Crawford, J. R. (2005). The short‐form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS‐21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non‐clinical sample. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44, 227–239. doi:https://doi.org/10.1348/014466505X29657

- Hinrichsen, H., & Clark, D. M. (2003). Anticipatory processing in social anxiety: Two pilot studies. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 34(3–4), 205–218. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005‐7916(03)00050‐8

- Hoerger, M. (2010). Participant dropout as a function of survey length in internet‐mediated university studies: Implications for study design and voluntary participation in psychological research. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 13(6), 697–700. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2009.0445

- Jain, M., & Sudhir, P. M. (2010). Dimensions of perfectionism and perfectionistic self‐presentation in social phobia. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 3(4), 216–221. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2010.08.006

- Juster, H. R., Heimberg, R. G., Frost, R. O., Holt, C. H., Mattia, J. I., & Faccenda, K. (1996). Social phobia and perfectionism. Personality and Individual Differences, 21, 403–410. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0191‐8869(96)00075‐X

- Koszycki, D., Benger, M., Shlik, J., & Bradwejn, J. (2007). Randomized trial of a meditation‐based stress reduction program and cognitive—Behavior therapy in generalized social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 2518–2526. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2007.04.011

- Lampe, L., Slade, T., Issakidis, C., & Andrews, G. (2003). Social phobia in the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well‐Being (NSMHWB). Psychological Medicine, 33(4), 637–646.

- Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depressions Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 335–343. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0005‐7967(94)00075‐U

- Magnani, R., Sabin, K., Saidel, T., & Heckathorn, D. (2005). Review of sampling hard‐to‐reach and hidden populations for HIV surveillance. AIDS (London, England), 19, 67–72. Retrieved from http://ist‐socrates.berkeley.edu/~maccoun/PP279_Magnani.pdf

- Nolen‐hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 400–424. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745‐6924.2008.00088.x

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. doi:https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

- Ryan, T., & Xenos, S. (2011). Who uses Facebook? An investigation into the relationship between the Big Five, shyness, Narcissism, loneliness and Facebook usage. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(5), 1658–1664. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.02.004

- Vassilopoulos, S. P. (2004). Anticipatory processing in social anxiety. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 32, 303–311. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465804001377

- Vassilopoulos, S. P. (2008). Coping strategies and anticipatory processing in high and low socially anxious individuals. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22, 98–107. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.01.010

- Waghorn, G., Chant, D., & Whiteford, H. (2005). Disability, employment and work performance among people with ICD‐10 anxiety disorders. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 39, 55–66. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440‐1614.2005.01510.x

- Weeks, J. G., Heimberg, R. G., Rodebaugh, T. L., Goldin, P. R., & Gross, J. G. (2011). Psychometric evaluation of the fear of positive evaluation scale in patients with social anxiety disorder. Psychological Assessment, 1, 1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025723

- Weiner, B. A., & Carton, J. S. (2012). Avoidant coping: A mediator of maladaptive perfectionism and test anxiety. Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 632–636. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.12.009

- Wong, Q. J. J., & Moulds, M. L. (2009). Impact of rumination versus distraction on anxiety and maladaptive self‐beliefs in socially anxious individuals. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47, 861–867. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2009.06.014

- Wong, Q. J. J., & Moulds, M. L. (2011). Impact of anticipatory processing versus distraction on multiple indices of anxiety in socially anxious individuals. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49, 700–706. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.07.007

Appendix Appendix

Vignettes

Social interaction vignette

Imagine the following situation:

A friend of yours is giving a party and you are invited to come. There will be a lot of people present at the party; however, all the guests are perfect strangers to you. Unfortunately, you cannot find someone to accompany you to the party. On the other hand, if you decline your friend's invitation you may offend him/her.

In responding to the items that follow, try to think of the kinds of things you typically do when you are facing such a situation.

Social performance vignette

Imagine the following situation:

You are going to deliver a presentation in the classroom/workplace. There will be a lot of students/colleagues as well as the professor/employer and the tutor/supervisor in the room watching your presentation. Although you have worked hard, you still do not feel ready to make the presentation in front of an audience. On the other hand, you are not in a position to postpone the presentation.

In responding to the items that follow, try to think of the kinds of things you typically do when you are facing such a situation.