Abstract

The purpose of this study was to assess the psychometric properties of the Self‐Ambivalence Measure and its subscales developed by Bhar and Kyrios. The factor structure, reliability, and validity of the measure were examined utilising a non‐clinical sample of 415 participants who completed self‐report measures of aspects of the self. Results indicated that the Self‐Ambivalence Measure exhibited levels of internal consistency and convergent and divergent validity, warranting its use in further research. In contrast to earlier research finding a two‐factor structure, a three‐factor structure was found to best fit the current sample and the factors were labelled Self‐Worth Ambivalence, Moral Ambivalence, and Public Self‐consciousness. This solution separated internal aspects of self‐ambivalence from social aspects which were conceptualised as an aspect of lovability. A discussion of implications is provided.

Introduction

Self‐ambivalence is conceptualised as the holding of conflicting views of the self simultaneously. The Self‐Ambivalence Measure (SAM; Bhar & Kyrios, Citation2007) is a relatively recent measure developed to assess the construct of self‐ambivalence which arose in the context of observations of clinical and non‐clinical levels of obsessive–compulsive (O–C) symptoms characterised by obsessions (i.e., persistent thoughts, impulses, ideas or images that are intrusive and inappropriate and cause marked levels of anxiety or distress) and compulsions (i.e., repetitive behaviours or mental acts that are often a response to obsessions and aim to reduce or prevent the distress of anxiety). In their theoretical discourse, Guidano and Liotti (Citation1983) proposed a model of obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) asserting that the development and maintenance of O–C patterns can be understood specifically in the context of conflicting views of the self, or ‘self‐ambivalence’, in which a person experiences dichotomous self‐perceptions and is unable to integrate them into a whole. Such individuals are conceptualised as being ambivalent about their self‐worth, morality, or lovability. Although other frameworks for the emergence of O–C symptoms have been proposed (e.g., genetic predispositions (Mundo, Zanoni, & Altamura, Citation2006); structural brain differences (Narayan et al., Citation2008); parenting practices (Hudson & Rapee, Citation2001); and faulty self‐perceptions and beliefs (Rachman, Citation1997; Salkovskis, Citation1985), the role of the self has been overlooked empirically despite its seemingly essential role in the understanding of an O–C presentation.

The concept of the self has undergone a dramatic transformation from early views of the self as a unitary, monolithic entity in which the focus of research efforts were often on a single aspect of self‐concept, such as self‐esteem (Campbell et al., Citation1996). More recently, the self has been redefined to be multifaceted and dynamic, including different components such as self‐beliefs, self‐evaluation, knowledge, structure, values, and goals. Amongst cognitive theorists, the self has been referred to as an agent who holds personal feelings of morality and can be held responsible and blamed for catastrophes (Wroe & Salkovskis, Citation2000). The construct of self‐ambivalence is part of this multifaceted view and reflects what was reported by O'Neill (Citation1999, p. 81) in a qualitative study of one woman's account of living with OCD documenting her inner conflict—‘There's the rational me and there's the irrational … it's the two of us I suppose or my conscience or two bits of my mind battling it out.’

The empirical study of self‐ambivalence is fairly limited but is expanding with the development of SAM which is often used as a singular measure of self‐ambivalence. The SAM has identified subscales that are consistent with two of three aspects of self‐ambivalence theorised: self‐worth ambivalence holding conflicted evaluations of the self and confusion about self‐worth, and moral ambivalence holding dichotomous views of the self as good or bad. The initial findings support the premise of Guidano and Liotti (Citation1983) that individuals who are self‐ambivalent are prone to O–C symptoms specifically as self‐ambivalence was associated with OCD severity and OCD‐relevant beliefs (Bhar & Kyrios, Citation2007). Self‐ambivalence has also been found to be a unique predictor of compulsive hoarding and compulsive buying symptoms after consideration of depressive symptoms and decision‐making difficulties (Frost, Kyrios, McCarthy, & Matthews, Citation2007). Higher self‐ambivalence has been reported by individuals presenting with body dysmorphic disorder (BDD, characterised by a preoccupation with a defect in appearance causing significant distress in daily functioning) as compared to normal controls in exploration of the O–C nature of BDD symptoms (Labuschagne, Castle, & Rossell, Citation2011; Labuschagne, Castle, Dunai, Kyrios, & Rossell, Citation2010). However, there is some indication that self‐ambivalence might be relevant to anxiety more generally, outside of OCD presentations. More specifically, although self‐ambivalence distinguished OCD sufferers from normal controls, it did not do so for anxious controls in Bhar and Kyrios's (Citation2007) original research.

Notably, self‐esteem research has developed other measures of self‐ambivalence that include the Riketta and Ziegler's (Citation2006) measure of self‐ambivalence and the measure upon which it was based by Gramzow, Sedikides, Panter, and Chester (Citation2000). In such research, self‐ambivalence is conceptualised and measured as the co‐existence of positive and negative self‐evaluations, arguing that self‐ambivalence is related to self‐esteem. Self‐ambivalence is viewed with two components: structural ambivalence also called objective ambivalence, holding positive and negative self‐evaluations, and experienced ambivalence—also called subjective ambivalence—subjective feeling towards being self‐ambivalent. Structural ambivalence has been found to predict self‐evaluations in manipulated experimental conditions (Demarree, Morrison, Wheeler, & Petty, Citation2011; Riketta & Ziegler, Citation2007). However, Riketta and Ziegler's (Citation2006) measure of self‐ambivalence is at a similar stage of development and does not address the question of the relationship between self‐ambivalence and O–C symptoms and its theoretical underpinnings.

Therefore, it is clear that further exploration of the psychometric properties of the SAM is warranted to establish it as a tool for use in research associated with O–C symptoms. Further, consideration of the use of the SAM with anxiety more generally is indicated.

Study aims

The purpose of the present study was to further investigate the psychometric properties of the SAM in a non‐clinical sample. Preliminary data analyses were conducted, and confirmatory and exploratory factor analyses were both performed to ascertain the best fitting factor structure for the current sample. Reliability was assessed through internal consistency, and convergent and divergent validity was tested by including several alternative measures of self‐evaluation, namely self‐splitting, rumination, reflection, and self‐clarity. The SAM was expected to be associated with greater self‐splitting, rumination and reflection, and poorer self‐clarity. An additional aim of the study was to confirm the association between the SAM and O–C symptoms, and assess the association between the SAM and anxiety symptoms more generally.

Method

Participants

The sample comprised of 415 participants who were 18 years or older (mean age = 26.5, SD = 11.1) and able to read English. The sample included 271 women and 149 men of which 265 were students (63%) and 155 were non‐students (37%). Psychology undergraduate students volunteered via the research participation program at Monash University and received course credit for their participation (n = 178). Other student participants responded to announcements made in lectures or posters advertised on the university campus (n = 87). Staff or interested members of the community who saw posters also responded (n = 20). Participants also responded to an advertisement in a state newspaper (n = 108) or an email sent to researchers' social networks (n = 24). Finally, an advertisement was placed through a local anxiety support centre in its monthly newsletter and electronic bulletin (n = 3).

Materials

The Self‐Ambivalence Measure (Bhar & Kyrios, Citation2007) consists of 21 items that measure ambivalence about one's general sense of self‐worth, based on Guidano and Liotti's concept of self‐ambivalence described in the introduction (Guidano, Citation1987; Guidano & Liotti, Citation1983). Items represent ambivalence about self‐worth, morality and social acceptance, including dichotomous appraisals of self, self‐uncertainty, and preoccupation about self‐worth (e.g., ‘I question the extent to which others want to be close to me’). Participants indicate their level of agreement for each item according to a 5‐point scale (0 = not at all to 4 = agree totally) and higher scores represent greater self‐ambivalence (item 11 was reverse‐scored). Two analyses of the factor structure of the SAM were conducted with two samples, a non‐clinical sample and a clinical sample, and Bhar and Kyrios (Citation2007) consistently identified two factors, Self‐worth Ambivalence and Moral Ambivalence. The SAM has been associated with good internal consistency in non‐clinical and clinical samples (Self‐Ambivalence factor α = .88, .88; Moral Ambivalence factor α = .85, .86), and has achieved a satisfactory level of criterion and convergent validity. Test–retest reliability has also been demonstrated over an average 10.8–week interval (r ≥ .77) (Bhar & Kyrios, Citation2007).

Other self measures

The Splitting Index is a 24‐item questionnaire based on Kernberg's (Citation1985) notion of splitting, that is, a tendency to see oneself as all good or all bad (e.g., ‘my feelings about myself shift dramatically’). The original measure includes three subscales: splitting of self, splitting of others, and splitting of family. The questionnaire has shown good internal consistency (α = .92), temporal stability over a four‐week interval (r = .88), and construct validity (Gould, Prentice, & Ainslie, Citation1996). Given that the Splitting Index was used to assess convergent validity of the SAM, only the self subscale of the Splitting Index was administered (S‐S; α = .88, r = .83) and item 6 was reverse‐scored. Participants rated the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with each of the eight statements (1 = disagree completely to 5 = agree completely), higher scores reflecting greater splitting of the self.

The Rumination–Reflection Measure (RRM) is a 24‐item questionnaire used to assess private self‐attentiveness/self‐focus (Trapnell & Campbell, Citation1999). The questionnaire consists of two subscales which purport to measure rumination (neurotic self‐attentiveness including recurrent thinking about the self, ‘sometimes it is hard for me to shut off thoughts about myself’) and reflection (intellectual self‐attentiveness motivated by curiosity, ‘I love analysing why I do things’). Participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement or disagreement with each statement on a 5‐point scale (0 = not at all to 4 = very much). Eight of the 24 items were reverse‐scored. Higher scores reflect greater rumination or reflection. The two scales, rumination and reflection, have been found to be independent tendencies, loading highly and uniquely on different factors (Trapnell & Campbell, Citation1999). Convergent and discriminant validity have also been demonstrated and alpha estimates of reliability have exceeded .90 (Joireman, Parrott, & Hammersla, Citation2002; Trapnell & Campbell, Citation1999).

The Self‐concept Clarity Scale (SCC) is a 12‐item instrument designed to measure the extent to which an individual's sense of self is clearly and confidently defined, consistent, and somewhat stable (Campbell et al., Citation1996). Participants indicate their level of agreement or disagreement on a 5‐point scale (0 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree). The 12 items, 10 of which are reverse‐scored, are summed to provide an index of self‐concept clarity, with higher scores reflecting greater levels of self‐clarity. Reports of psychometric properties of the SCC have indicated high internal consistency (α ≥ .86; Campbell, Assanand, & Di Paula, Citation2003; Campbell et al., Citation1996) and temporal stability over 4–5 month periods (r = .79 and .70, respectively) has been demonstrated. An example item is ‘In general, I have a clear sense of who I am and what I am’.

Symptom measures

The State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory‐Trait Subscale (TANX; Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg, & Jacobs, Citation1983) is a widely used 20‐item self‐report scale. Respondents are asked to rate how they generally feel in response to a series of self‐descriptive statements. The TANX is scored on four levels of anxiety intensity from 1 = not at all to 4 = very much with higher scores reflecting greater levels of trait anxiety. The scale includes 10 positively valanced items that are reverse‐scored and the internal consistency reliability estimates are very good (Cronbach's α ranging from .89 to .91) with acceptable test–retest reliability (α ranging from. 65 to .86). An example item is ‘I worry too much over something that really doesn't matter’.

The Padua Inventory—Revised (PI‐R) (Burns, Keortge, Formea, & Sternberger, Citation1996) is a 39‐item subset of the original 60‐item Padua Inventory (Sanavio, Citation1988). The inventory measures the frequency and severity of a range of intrusive thoughts and compulsive behaviours using a 5‐point scale (0 = not at all to 4 = very much), higher scores indicating more severe O–C symptoms. The PI‐R has been found to have acceptable psychometric properties, including discriminant validity between obsessions and worry, and test–retest reliability for a 6–7 month interval (r = .76, Burns et al., Citation1996), and has been used with both clinical and non‐clinical samples (Bhar & Kyrios, Citation2007; Obsessive Compulsive Cognitions Working Group, Citation2003). Consistent with past research, the total PI‐R score was used as an index of O–C symptoms. An example item is, ‘I feel my hands are dirty when I touch money.’

Procedure

Participants could choose whether to participate in person at Monash University (n = 291) or via mail (n = 129). All participants provided consent for participating. Participants completed questionnaires and, to control for order effects, the order in which the questionnaires were presented was counterbalanced across participants.

Results

Preliminary data analyses

Preliminary data analyses were conducted to assess missing data and to establish the normality of data. Of the 420 participants, five participants were excluded via listwise deletion because of incomplete responses. The remaining participants had minimal data missing (less than 0.05%). Scale scores were computed if all items or all but 1 item were completed resulting in 415 complete response sets. Skewness and kurtosis statistics were used to test assumptions of normality for all variables. Histograms and box plots were visually inspected. The data consisted of univariate skewness no greater than 3.0 and kurtosis indices no greater than 8.0, and were therefore considered to be within acceptable ranges (Kline, Citation1998). Comparisons between the non‐student and student sample were made on demographic information and responses to measures of the self. Significant differences were found between the student and non‐student samples as the student sample included a greater proportion of males (39.2% vs 29%, χ2 (1) = 4.46), was significantly younger (M = 21.9, SD = 6.1 vs M = 34.3, SD = 13.4, t(192) = −10.84) and spoke less English at home (25.7% vs 14.8%, χ2 (2) = 10.21). Although demographic differences were found between the two samples, there were no significant differences when comparing the measures of the self between the student and non‐student sample. A decision was made to merge the two samples in order to ascertain the factor structure with a larger sample size, to allow the total sample mean to closer approximate the unknown population mean, and to increase power (Gravetter & Wallnau, Citation2000). In order to examine the structure of the SAM, confirmatory factor analysis was first conducted to determine whether the current data set could be explained by previous factor structures empirically determined. This analysis was guided by past empirical research which hypothesised a two‐factor model (Bhar & Kyrios, Citation2007). The fit of this two‐factor model was evaluated and, following a weak solution, exploratory factor analysis was performed in order to find the best fitting factor structure for the current data set.

The structure of self‐ambivalence: CFA and EFA

A maximum likelihood confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed on the SAM using AMOS 7 (Amos Development Corporation, Meadville, PA, USA). CFA was performed to empirically determine whether the two‐factor structure previously found was an accurate fit for the current data set. A brief description of CFA is provided below.

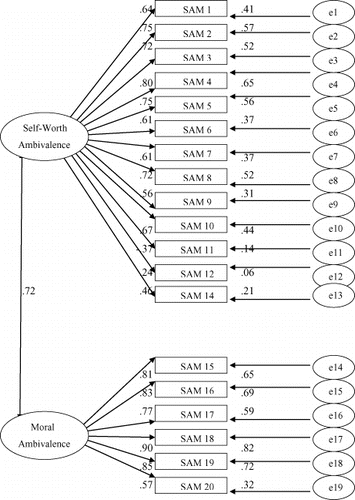

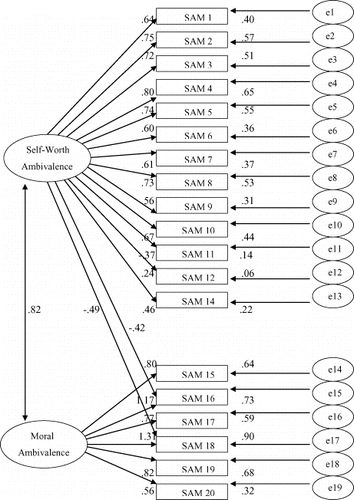

The initial hypothesised model (see Fig. 1) in the current study was based on Bhar and Kyrios's (Citation2007) two‐factor result, performed a priori with an initial non‐clinical sample of 268 participants, and then validated with 123 clinical participants. Evaluation of the hypothesised two‐factor structure indicated a poor model fit (χ2 = 786.25, df = 151, p < .001, normed fit index (NFI) = .83, comparative fit index (CFI) = .86, root‐mean‐squared error of approximation (RMSEA) = .10). Post hoc modifications were performed in an attempt to develop a better fitting model. Two large modification indices indicated that the model fit could be substantially improved by allowing item 16, ‘I question whether I am a moral person,’ and item 18, ‘I question whether I am morally a good or bad person’ to load on a Self‐Worth Ambivalence factor (see Fig. 2). Although the fit indices were improved, the final model was still deemed unacceptable (χ2 = 702.77, df = 149, p < .001, NFI = .85, CFI = .87, RMSEA = .09). Given that the hypothesised two‐factor structure did not appear to be an acceptable fitting model to the present sample, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed to identify a factor structure of the SAM that would best fit the current data.

EFA was used to determine whether the set of items used to measure self‐ambivalence could statistically reflect the self‐ambivalence variables the items were chosen to represent. Four methods for determining the number of factors were considered; the Kaiser–Guttman eigenvalue rule (Kaiser, Citation1960; Kaiser & Rice, Citation1974); Cattell's scree test (Cattell, Citation1966); Velicer's minimum average partial (MAP) test (Velicer, Citation1976); and Horn's ‘parallel’ test (Horn, Citation1965). The eigenvalue rule suggested five factors, the scree plot suggested two factors, and both the MAP test and the parallel test suggested three factors. The approach of retaining factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 has been criticised for having too generous a basis for retaining factors and has not been accepted by specialist factor analysts (e.g., DeVellis, Citation2003). Further, the scree test, although frequently used and often found to be an accurate determination of the number of factors, has been noted to be subjective, and research suggests that this approach is not particularly reliable (Crawford & Koopman, Citation1979; Streiner, Citation1998). The MAP and parallel tests have been shown to be more accurate and less variable than the scree test (Wood, Tartaryn, & Gorsuch, Citation1996; Zwick & Velicer, Citation1986). Accordingly, an oblique rotation (Promax, Kappa = 2) extracting three factors was deemed most appropriate (RMSEA = 0.01) showing a close fit (Browne & Cudeck, Citation1993). An item was included in a factor scale if the item's loading was at least .30, and if the difference in loadings across the two factors was more than .10. Item 9, ‘I fear I am capable of doing something terrible’ and item 21, ‘Essentially people like you or they don't; there is no middle ground’ failed to meet these criteria. Subsequently, items 9 and 21 were excluded. The resulting factor loadings are shown in Table .

Table 1. Factor analytic solution for the SAM (n = 415)

Reliability

Internal consistency was inspected for all scales used to assess the validity of the SAM (see Table ). All scales showed very good internal consistency (α = .75 or above). In addition, omega and omega‐h statistics were computed (Watkins, Citation2013) to assess whether the scale scores were reliable in estimating self‐ambivalence scores for individuals and generalised to a common latent variable, respectively (Zinbarg, Yovel, Revelle, & McDonald, Citation2006). As is reported in Table , the omega values for the SAM total, Self‐worth Ambivalence, and Public Self‐conciousness are very high, indicating that an individual's scores on these scales are reliable in estimating his or her standing on the latent variable described as self‐ambivalence. The Moral Ambivalence's omega coefficient indicates it is not a useful scale to estimate one's self‐ambivalence. The omega‐h coefficients are lower, but consistent, indicating that the total scale and subscales generalise to a common latent variable.

Table 2. Reliability coefficients, means, and standard deviations for the self scales (n = 415)

Validity

In order to assess convergent validity and divergent validity, zero‐order correlations between the SAM and measures of self‐splitting, rumination reflection, and self‐uncertainty were conducted (see Table ). Convergent validity occurs when a measure correlates highly with other measures which are theoretically similar. Divergent validity occurs when low correlations are demonstrated with variables that are dissimilar to the measure (Groth‐Marnat, Citation1997). Given the number of comparisons, an alpha level of .001 (Bonferroni method) was used to assess significance.

Table 3. Zero‐order correlations between measures of self‐ambivalence, self scales, trait anxiety, and obsessive–compulsive symptoms (n = 415)

As can be seen from Table , Self‐Worth and Moral Ambivalence correlated most highly with self‐concept clarity, and these relationships were in a negative direction, providing convergent validity as individuals' greater conflict about their self‐worth and morality corresponds with feeling less clarity and consistency about themselves. Public Self‐consciousness was most strongly related to Rumination while the Reflection subscale showed the weakest association with all three self‐ambivalent factors. This suggests that although there is some slight overlap between the two concepts, the SAM relates better to preoccupation with self than to reflections about the self.

Discussion

This study aimed to further investigate the psychometric properties of the SAM, originally developed by Bhar and Kyrios (Citation2007), in a non‐clinical sample. Statistical analyses indicated a three‐factor structure, rather than the original two‐factor structure as identified by Bhar and Kyrios (Citation2007). The current three‐factor SAM was found to have adequate internal consistency. Convergent validity was assessed by correlating the SAM with measures assessing concepts that are theoretically similar. The high associations found between the self‐ambivalent factors and splitting, rumination and self‐uncertainty (low clarity of self‐concept) provide support for convergent validity while divergent validity was shown by the nonsignificant associations between all three self‐ambivalence factors and self‐reflection. This result provides further support for previous research on the SAM (Bhar & Kyrios, Citation2007). Similar relationships were found for the total self‐ambivalence scores. More specifically, in contrast with previous research in which a two‐factor solution was identified (Bhar & Kyrios, Citation2007), in this sample, the SAM was best characterised by three factors tapping into a more global Self‐worth Ambivalence, as well as specific domains of Moral Ambivalence and Public Self‐consciousness. The first factor (Self‐Worth Ambivalence; 9 items) reflects a fragmented sense of self and confusion about self‐worth, including items about perceptions about self‐worth and a general sense of ambivalence and conflict. These nine items were also included in Bhar and Kyrios's (Citation2007) Self‐Worth Ambivalence factor. The second factor (Moral Ambivalence; 6 items) specifically reflects preoccupation with self‐morality and concern about being a good person. Many of the items in this factor reflected a dichotomy between moral and immoral, and the ambivalence in thinking of oneself as a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ person. The items that encompassed this factor are consistent with Bhar and Kyrios's (Citation2007) Moral Ambivalence factor.

The third factor (Public Self‐consciousness; 4 items) reflected concern about social appearances and a preoccupation with other peoples' perceptions and judgements. Public self‐consciousness is defined as a preoccupation with oneself, rather than the philosophical state of self‐awareness, and this is evident in the need to check self‐observations against a standard of social expectations or a stereotyped self‐image (Buss, Citation1980). This factor signified a key difference from the previous two‐factor solution (Bhar & Kyrios, Citation2007) in which three of the Public Self‐consciousness items were subsumed within the Self‐Worth Ambivalence factor, and one item was omitted because of its weak loading. The separation of Public Self‐consciousness in the current study provides initial evidence that the SAM might be tapping into an internally consistent social domain, as well as moral and self‐worth domains. This third factor was labelled ‘Public Self‐consciousness’ given that the meaning of the items in this factor was similar to the content of items in Fenigstein, Scheier, and Buss's (Citation1975) Public Self‐consciousness Scale.

The final item of the Public Self‐consciousness factor ‘I think about how I can improve myself’ suggests that one's perception of self‐improvement has a social motivation. This is consistent with the concept of public self‐consciousness that is underpinned by preoccupation with oneself, self‐acceptance, and other people's approval of one's appearance. Together, all three factors achieved omega‐hierarchical coefficients consistent with these factors being generalisable to a common latent variable that is conceived as self‐ambivalence. The omega coefficients indicated that the Self‐Worth Ambivalence and Public Self‐consciousness subscales can be considered as reliably estimating an individuals standing on the latent variable. However, the Moral Ambivalence subscale is not reliable as such an estimation, despite being generalisable to the common latent variable.

The three factors appear to represent unique but related facets of uncertainty and internal doubting, and suggest that specific domains of the self are not necessarily subsumed within a broad sense of self‐worth. The Self‐Worth Ambivalence factor reflected a state of inner conflict characterised by uncertainty about one's worth as an individual, and a torn personality. This factor may represent broader questioning of self‐worth, as the items appear more global in nature. In contrast, the second and third factors appear to represent two specific domains of the self; a moral component and a social component, respectively. However, given the Moral Ambivalence factor is not a statistically good estimate of one's overall self‐ambivalence and that this factor explains relatively little (i.e., .58) of the variance in the factor analytic solution, further research is demanded. Further, given the differing results here to the original study by Bhar and Kyrios (Citation2007), the factors may lack stability and the SAM might be better utilised as a single scale based on a total score, rather than three separate factors. Future research may clarify the factor stability.

However, the identification of Public Self‐consciousness as a separate factor in the current study may be consistent with a component of Guidano and Liotti's (Citation1983) theoretical description of individuals' ambivalence about lovability. Guidano and Liotti (Citation1983) do not specify a definition of lovability, but rather use lovability to describe an individual feeling secure about being loved by his or her parents, being accepted without conditions, self‐acceptance, and feeling approved by others. These latter components (i.e., self‐acceptance and others' approval) overlap with the concept of public self‐consciousness. Arguably, if individuals are comfortable and accepting of themselves, they might feel less preoccupied with other people's impressions (Tisher, Citation2009). Individuals who are preoccupied with other people's judgements are more sensitive to being shunned by others (Leary, Citation2000) and therefore, acceptance and approval by others are defining features of public self‐consciousness. In other words, lovability does not equate to public self‐consciousness. Rather, elements of public self‐consciousness in this study (‘When I am with others, I think about whether I look my best’) and the importance of others' approval (‘I am constantly aware of how others perceive me’), overlap with references made to lovability throughout Guidano and Liotti's (Citation1983) discourse. Although the emphasis of certain features such as self‐acceptance and other people's approval of one's appearance in public self‐consciousness can be understood as being incorporated in the overall concept of lovability, the current findings suggest the extension of this factor is consistent with the original model's description of self‐ambivalence.

With regard to the second aim of the study, the current study confirmed the significant and positive relationship between all three subscales and the total score of O–C symptoms and trait anxiety in a non‐clinical sample of men and women. Although self‐ambivalence was originally formulated as specific to obsessive–compulsive symptoms (Guidano & Liotti, Citation1983), the limited empirical research has extended the relevance of self‐ambivalence to other manifestations of anxiety (Bhar & Kyrios, Citation2007). The finding that self‐ambivalence is related to trait anxiety is consistent with past research that has identified uncertain self‐concepts as common to multiple clinical and subclinical manifestations and diagnostic groups (e.g., McNally, Citation1993; Ozgul, Heubeck, Ward, & Wilkinson, Citation2003; Veale, Kinderman, Riley, & Lambrou, Citation2003).

The results from this study offer implications for research and clinical practice. The relationships identified in the current results suggest that aspects of the self are experienced at an accessible level of consciousness, and that empirical research using self‐report measures provides important information about an individual's view of self and how s/he relates to the social context. Based on the findings and previous research discussed above, the SAM is recommended for use to both clinicians and researchers as a total scale that taps into a global sense of self‐ambivalence that reflects whether or not an individual views his or her self‐worth with ambivalence, and holds concerns of ‘goodness’ and about the perceptions of others. The research described earlier by Labuschagne, Castle, Dunai, Kyrios & Rossell (Citation2010) and Labuschagne, Castle & Rossell (Citation2011) have used the SAM in this way. However, the evidence here suggests that two of the three SAM subscales are robust enough to use individually to enhance the description of research findings. Whereas, the results indicate that Moral Ambivalence requires further investigation. Therefore, it is recommended here that future research should continue to assess the factor structure of the SAM. Future research might benefit with the use of a combination of self‐report and interview, behavioural and observational measures, as well as measures accessing aspects of the self at a more unconscious level. The SAM may also be a valuable addition to clinical practice subject to further analyses that include measures of mood, obsessions, and compulsions. Such findings might suggest that it is relevant to consider self‐ambivalence in a clinical assessment process and highlight a focus for therapeutic intervention.

Certain limitations of this study should be noted. Caution needs to be taken when interpreting the current factor solution. After the CFA did not support a two‐factor solution, EFA was performed to gain statistical information and identify a best fitting model for the current sample. EFA and CFA are preferably performed on different samples as a means to demonstrate the generalisability of a scale (DeVellis, Citation2003). Given that an appropriate sample size for factor analysis is over 300 (Comrey & Lee, Citation1992), the current sample of 415 was not deemed large enough to split in half, one half to be used for exploratory factor analysis, the other half for CFA. Following the decision to perform both EFA and CFA on the same sample in the current study, this factor solution warrants replication to strengthen the use of three subscales and increase generalisation.

Interpretations from the current investigation are also limited to aspects of self‐ambivalence that are accessible to a person's awareness and can therefore be tapped into via a self‐report measure. Aspects of the self, because of their importance in defining or characterising the self, are likely to be constantly accessible (Higgins, King, & Mavin, Citation1982; Markus & Kunda, Citation1986) and therefore should be relevant for self‐report measures. Arguably, it is possible that parts of the self do remain outside an individual's awareness, and therefore the current research did not elicit such information. Accordingly, our knowledge from the SAM is only informative for components of self‐ambivalence of which an individual is aware. In addition, method variation could have inflated the correlations given the sole use of self‐report measures.

Despite these limitations, the current psychometric investigation provides further evidence about the SAM and how it might be used. Further, the separation of social aspects of self‐ambivalence is unique and suggests public self‐consciousness as an aspect of lovability. Allowing for the caveat that exploratory and CFA were performed on the same sample, the results suggest that the SAM can be used to measure both general and specific domains of self‐ambivalence. This study also confirmed the relevance of self‐ambivalence to general manifestations of anxiety. Further replication is warranted to ascertain the underlying factors of the SAM.

References

- Bhar, S. S., & Kyrios, M. (2007). An investigation of self‐ambivalence in obsessive‐compulsive disorder. Behaviour Research & Therapy, 45, 1845–1857.

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Newbury Park: Sage.

- Burns, G. L., Keortge, S. G., Formea, G. M., & Sternberger, L. G. (1996). Revision of the Padua Inventory of obsessive compulsive disorder symptoms: Distinctions between worry, obsessions, and compulsions. Behaviour Research & Therapy, 34, 163–173.

- Buss, A. H. (1980). Self‐consciousness and social anxiety. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman and Company.

- Campbell, J. D., Trapnell, P. D., Heine, S. J., Katz, I. M., Lavallee, L. F., & Lehman, D. R. (1996). Self‐concept clarity: Measurement, personality correlates, and cultural boundaries. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 141–156.

- Campbell, J. D., Assanand, S., & Di paula, A. (2003). The structure of the self‐concept and its relation to psychological adjustment. Journal of Personality, 71(1), 115–140.

- Cattell, R. B. (1966). Patterns of change: Measurement in relation to state‐dimension, trait change, lability, and process concepts. In R. B. Cattell (Ed.), Handbook of multivariate experimental psychology (pp. 355–402). Chicago: Rand McNally & Company.

- Comrey, A. L., & Lee, H. B. (1992). A first course in factor analysis. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Crawford, C. B., & Koopman, P. (1979). Inter‐rater reliability of scree test and mean square ratio test of number of factors. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 49, 223–226.

- Demarree, K. G., Morrison, K. R., Wheeler, S. C., & Petty, R. E. (2011). Self‐ambivalence and resistance to subtle self‐change attempts. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37, 674–686.

- Devellis, R. F. (2003). Scale development: Theory and applications. London: SAGE Publications.

- Fenigstein, A., Scheier, M. F., & Buss, A. H. (1975). Public and private self‐consciousness: Assessment and theory. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 43, 522–527.

- Frost, R. O., Kyrios, M., Mccarthy, K. D., & Matthews, Y. (2007). Self‐ambivalence and attachment to possessions. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 21, 232–242.

- Gould, J. R., Prentice, N. M., & Ainslie, R. C. (1996). The splitting index: Construction of a scale measuring the defense mechanism of splitting. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66, 414–430.

- Gramzow, R. H., Sedikides, C., Panter, A. T., & Chester, A. I. (2000). Aspects of self‐regulation and self‐structure as predictors of perceived emotional distress. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 188–205.

- Gravetter, F. J., & Wallnau, L. B. (2000). Statistics for the behavioral sciences. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

- Groth‐marnat, G. (1997). Handbook of psychological assessment. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Guidano, V. F. (1987). Complexity of the self: A developmental approach to psychopathology and therapy. New York: The Guilford Pres.

- Guidano, V. F., & Liotti, G. (1983). Cognitive processes and emotional disorders. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Higgins, E. T., King, G. A., & Mavin, G. H. (1982). Individual construct accessibility and subjective impressions and recall. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43, 35–47.

- Horn, J. L. (1965). A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometika, 30, 179–185.

- Hudson, J. L., & Rapee, R. M. (2001). Parent–child interactions and anxiety disorders: An observational study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 39, 1411–1427.

- Joireman, J. A., Parrott, L. III, & Hammersla, J. (2002). Empathy and the self‐absorption paradox: Support for the distinction between self‐rumination and self‐Reflection. Self and Identity, 1(1), 53–65.

- Kaiser, H. F. (1960). The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20, 141–151.

- Kaiser, H. F., & Rice, J. (1974). Little Jiffy, Mark IV. Educational & Psychological Measurement, 34, 111–117.

- Kernberg, O. F. (1985). Borderline conditions and pathological narcissism. New Jersey: Jason Aronson Inc.

- Kline, R. B. (1998). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Labuschagne, I., Castle, D., Dunai, J., Kyrios, M., & Rossell, S. (2010). An examination of delusional thinking and cognitive styles in body dysmorphic disorder. The Australian and New Zealand Journal Of Psychiatry, 44, 706–712.

- Labuschagne, I., Castle, D. J., & Rossell, S. L. (2011). What the cognitive deficits in body dysmorphic disorder tell us about the underlying neurobiology: An investigation of three cases. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 4, 21–33.

- Leary, M. R. (2000). Self‐consciousness. In A. E. Kazdin (Ed.), Encyclopaedia of psychology. Vol. 7, (pp. 209–210). Washington, DC; New York, NY: American Psychological Association; Oxford University Press.

- Markus, H., & Kunda, Z. (1986). Stability and malleability of the self‐concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(4), 858–866.

- Mcnally, R. J. (1993). Self‐representation in post‐traumatic stress disorder: A cognitive perspective. In Z. V. Segal & S. J. Blatt (Eds.), The self in emotional distress: Cognitive and psychodynamic perspectives (pp. 71–99). New York: Guilford Press.

- Mundo, E., Zanoni, S., & Altamura, A. C. (2006). Genetic issues in obsessive‐compulsive disorder and related disorders. Psychiatric Annals, 36, 495–512.

- Narayan, V. M., Narr, K. L., Phillips, O. R., Thompson, P. M., Toga, A. W., & Szeszko, P. R. (2008). Greater regional cortical gray matter thickness in obsessive‐compulsive disorder. Neurorepor, 19, 1551–1555.

- Obsessive Compulsive Cognitions Working Group (2003). Psychometric validation of the obsessive beliefs questionnaire and the interpretation of intrusions inventory: Part 1. Behaviour Research & Therapy, 41, 863–878.

- O'neill, S. A. (1999). Living with obsessive‐compulsive disorder: A case study of a woman's construction of self. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 12(1), 73–86.

- Ozgul, S., Heubeck, B., Ward, J., & Wilkinson, R. (2003). Self‐discrepancies: Measurement and relation to various negative affective states. Australian Journal of Psychology, 55(1), 56–62.

- Rachman, S. (1997). A cognitive theory of obsessions. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35, 793–802.

- Riketta, M., & Ziegler, R. (2006). Self‐ambivalence and self‐esteem. Current Psychology, 25, 192–211.

- Riketta, M., & Ziegler, R. (2007). Self‐ambivalence and reactions to success versus failure. European Journal of Social Psychology, 37, 547–560.

- Salkovskis, P. M. (1985). Obsessional‐compulsive problems: A cognitive‐behavioural analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 23, 571–583.

- Sanavio, E. (1988). Obsessions and compulsions: The Padua Inventory. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 26(2), 169–177.

- Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., Lushene, P. R., Vagg, P. R., & Jacobs, A. G. (1983). Manual for the state‐trait anxiety inventory (Form Y). Redwood City: Mind Garden.

- Streiner, D. L. (1998). Factors affecting reliability of interpretations of scree plots. Psychological Reports, 83, 687–694.

- Tisher, R. (2009). A study of obsessive‐compulsive phenomena: self‐ambivalence, perfectionism and romantic attachment. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia.

- Trapnell, P. D., & Campbell, J. D. (1999). Private self‐consciousness and the five‐factor model of personality: Distinguishing rumination from reflection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 284–304.

- Veale, D., Kinderman, P., Riley, S., & Lambrou, C. (2003). Self‐discrepancy in body dysmorphic disorder. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 42, 157–169.

- Velicer, W. F. (1976). Determining the number of components from the matrix of partial correlations. Psychometrika, 41, 321–327.

- Watkins, M. W. (2013). Omega (Computer software). Phoenix, AZ: Ed & Psych Associates.

- Wood, J. M., Tartaryn, D. J., & Gorsuch, R. L. (1996). Effects of under‐ and overextraction on principal axis factor analysis with varimax rotation. Psychological Methods, 1, 354–365.

- Wroe, A. L., & Salkovskis, P. M. (2000). Causing harm and allowing harm: A study of beliefs in obsessional problems. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38, 1141–1162.

- Zinbarg, R. E., Yovel, I., Revelle, W., & Mcdonald, R. P. (2006). Estimating generalizability to a latent variable common to all of a scales indicators: A comparison of estimators for ωh. Applied Psychological Measurement, 27, 121–144.

- Zwick, W. R., & Velicer, W. F. (1986). A comparison of five rules for determining the number of components to retain. Psychological Bulletin, 99, 432–442.