Abstract

Teachers and youth sports coaches are in prominent positions to support young people and their mental health. However, the way these professionals perceive their roles is likely to be a powerful influence on such behaviour. This article investigates and compares the effect of four types of role perceptions—role breadth, instrumentality, efficacy, and discretion—on teachers' and coaches' engagement in helping behaviour that supports young people's mental health through promotion, prevention, and early intervention. An online survey was completed by 117 teachers and 131 coaches. Results from three multiple group path analyses revealed role breadth, instrumentality, and efficacy significantly influenced teachers' and coaches' helping behaviour. The extent to which role perceptions predicted helping behaviour did not differ between teachers and coaches. Assisting teachers and coaches to carry out promotion, prevention, and early intervention behaviour increases young people's access to mental health support and may help to reduce the burden of mental health problems among Australian young people.

Introduction

Young people have the highest prevalence of mental health problems across the lifespan, but they tend not to seek help and have the lowest rate of mental health service use (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2010; Rickwood, Deane, Wilson, & Ciarrochi, Citation2005). Adolescence and young adulthood are, therefore, critical periods in which to promote mental health and provide assistance to access support and interventions for mental health problems. Taking early and effective action is critical to minimise the impact and progression of mental health problems. Consequently, improving young people's mental health and well‐being through promotion, prevention, and early intervention are priorities for mental health in Australia (Commonwealth of Australia, Citation2009).

Promotion, prevention, and early intervention (PPEI) can be carried out across a range of contexts, and many adults in community‐based roles, such as teachers and sports coaches, can help (Commonwealth of Australia, Citation2009). Both teachers and coaches are in regular contact with a large number of young people have established relationships with young people, occupy positions of care and responsibility for young people, impart learning primarily in areas such as academic or physical performance but also invaluable life skills, and contribute to positive youth development (Graham, Phelps, Maddison, & Fitzgerald, Citation2011; Mazzer & Rickwood, Citation2013). Collectively, this places teachers and youth sports coaches in prominent positions to make a major contribution to young people's mental health (Donovan et al., Citation2006).

Although teachers, coaches, and other community‐based adults may have the potential to support young people's mental health, how they should or could be involved is not well defined. There is growing interest in the extent to which promotion, prevention, and early intervention fit within the roles of a teacher or coach, but little understanding of how this occurs and can be supported. Mazzer and Rickwood (Citation2013) recently explored this area, finding that both teachers and coaches often engage in activities that promote young people's mental health, but that there is significant variability. While both were similarly involved in promotion, teachers were found to more commonly engage in behaviour to prevent and intervene early in mental health problems than coaches.

It is also important to understand factors that may influence teachers' and coaches' involvement in PPEI for young people's mental health in order to determine ways to support their performance in this regard. The ways individuals perceive their roles can be a powerful influence on behaviour (Morrison, Citation1994; Parker, Citation2007), but little is known about teachers' and coaches' views regarding their role in supporting young people's mental health.

Previous research examining individuals' views of their working roles has focused on four main types of role‐related perceptions: perceived role breadth, perceived instrumentality, perceived role efficacy, and perceived role discretion. These role perceptions have been found to have a substantial impact on employees' interpersonal helping behaviour at work when such behaviour may be considered above and beyond the formal requirements of a job (McAllister, Kamdar, Morrison, & Turban, Citation2007), as may be the case with PPEI behaviour for teachers and coaches.

Role breadth

Perceived role breadth is the most studied role‐related perception and refers to whether an individual regards particular activities or behaviours as part of their job (McAllister et al., Citation2007). Role breadth is subject to an individual's perception; so, two people holding the same formal position can differ in how broadly they each define that job. Previous studies have shown perceived role breadth to directly predict behaviour, whereby, individuals are more likely to perform behaviour they perceive as within their role breadth (Coyle‐Shapiro, Kessler, & Purcell, Citation2004; Morrison, Citation1994). Furthermore, McAllister et al. (Citation2007) found role breadth to be the strongest predictor of employee's interpersonal helping behaviour when compared to perceived instrumentality, perceived role efficacy, and perceived role discretion. Research investigating the role breadth of teachers and coaches in relation to young people's mental health is limited, however, two recent studies have indicated that both teachers and coaches perform a number of activities which support young people's mental health as part of their role (Donovan, et al., Citation2006; Mazzer, Rickwood, & Vanags, Citation2012).

Instrumentality

Perceived role instrumentality can be defined as whether an individual perceives a relationship between performance of behaviour and outcomes such as rewards and punishment (McAllister et al., Citation2007). Behaviour that is linked to valued outcomes is more likely to be performed (Bandura & McClelland, Citation1977). McAllister et al. (Citation2007) reported instrumentality to be a significant predictor of employees' interpersonal helping behaviour. The role instrumentality of teachers and coaches for supporting young people's mental health has not previously been investigated.

Efficacy

Role efficacy refers to a specific form of self‐efficacy relating to an individual's perception of their competence in performing a given type of behaviour (Bandura, Citation1977; McAllister, et al., Citation2007). Self‐efficacy is a well‐established predictor of behaviour and performance (Bandura, Citation1986; Beauchamp, Bray, Eys, & Carron, Citation2002). Low self‐efficacy has been identified by teachers and coaches to be a limitation to their willingness for involvement in supporting young people's mental health (Mazzer & Rickwood, Citation2013, unpublished data).

Discretion

Role discretion refers to the extent to which an individual perceives choice with respect to performing particular behaviour (McAllister et al., Citation2007). Behaviour that is considered discretionary can vary from person to person and across different situations (Organ, Citation1997). The degree to which teachers and coaches have freedom to choose to perform PPEI activities may influence their actions.

Aims and hypotheses

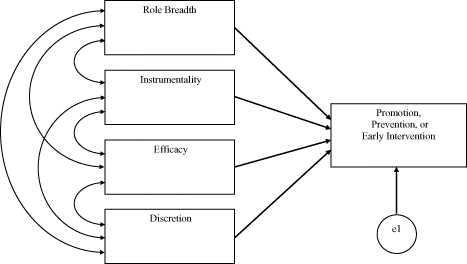

The aim of this study was to investigate how role‐related perceptions impact on teachers' and coaches' undertaking of promotion, prevention, and early intervention in order to better understand ways to assist and improve their performance of such activities. We examined the relative effects of four role perceptions—role breadth, instrumentality, efficacy, and discretion—as proposed by McAllister et al. (Citation2007) on teachers' and coaches' engagement in helping behaviour to support young people's mental health through PPEI. It was hypothesised that role breadth would be the strongest predictor for helping behaviour. The study also sought to determine whether the effects of role perceptions on helping behaviour were equivalent for teachers and coaches. In the absence of any evidence to suggest otherwise, it was hypothesised that there would be group invariance, that is, these effects would be similar across the teacher and coach groups. Fig. 1 displays the proposed saturated model for predicting the three types of helping behaviour (promotion, prevention, and early intervention).

Method

Participants

Participants were 117 teachers (71 female, 43 male, and 3 did not report) and 131 coaches (49 female, 81 male, and 1 did not report) of 12–18 year olds from Canberra, Australia, creating a total sample of 258. The age of teacher participants ranged from 22 to 69 years, with a mean age of 41.59 (standard deviation (SD) = 12.27). The age range of coach participants was 18 to 58 years, with a similar mean age of 39.11 (SD = 11.90). Participants' length of experience in their role ranged from less than 1 year to 50 years, with teachers' mean experience of 14.60 years (SD = 11.62) being greater than coaches' mean experience of 9.75 years (SD = 8.64).

Teachers from eight schools within Canberra participated in the study. Most (n = 74) teachers were employed at co‐educational schools rather than single‐sex schools (n = 35; 8 not reported). Sixty‐four taught at government high schools or colleges and 53 at non‐government (private or independent) schools. Teachers who participated in the study taught across a range of subjects including: mathematics (n = 20); science (n = 11); English and social studies (n = 33); physical education (PE; n = 14); and other (elective) subjects such as drama, information technology, and religion (n = 36; 3 did not report).

Coaches from four sports participated: soccer (n = 49); netball (n = 28); basketball (n = 34); Australian Football League (AFL; n = 17; 3 did not report). Slightly more coaches worked with girls only (n = 61) than boys only (n = 40) or mixed gender groups (n = 30). The level of sport competition that participants coached included social (n = 52), competitive (n = 104), and elite (n = 17) sport, with many (n = 42) reporting they coached across a variety of levels.

Procedure

The project was approved by the Committee for Human Research Ethics at the University of Canberra, the ACT Government Education and Training Directorate, and the Archdiocese of Canberra and Goulburn Catholic Education Office. Final permission was sought and obtained from the principal of each school prior to the research proceeding at their site. The club president or club contact of each sporting club was also consulted prior to involvement in the project. Principals and presidents of each selected school and sports club were initially contacted by phone and/or email. Those who gave permission for involvement in the research forwarded an email from the primary researcher with a link to the online survey inviting teachers and coaches of young people aged 12 to 18 to participate in the research. Participants then completed the survey online. To encourage greater participation, all participants were given the opportunity to enter a prize draw to win an Apple iPad (Cobanoglu & Cobanoglu, Citation2003).

Recruitment of teachers

Teachers were recruited through their schools. To ensure a representative cross‐section of schools and school characteristics, a multi‐stage sampling technique combining a number of sampling methods was employed. This involved alphabetically sorting and stratifying a list of all schools within Canberra. Every second school (n = 23) was invited to participate; eight schools agreed and were included in the final sample. All teachers of 12–18 year olds from the recruited schools were invited to participate in the study.

Recruitment of coaches

Multi‐stage sampling was similarly used for the recruitment of coaches who were accessed through sports clubs of the four most popular team sports in Australia: soccer, netball, basketball, and AFL (Australian Sports Commission, Citation2010). All 31 sports clubs based within Canberra, involving young people aged 12 to 18 years, and listed on their respective sports' state organisation web site were invited to participate. Twenty‐one clubs agreed to participate, including six soccer, four netball, four basketball, and seven AFL clubs. All coaches of 12–18 year olds within the recruited sports clubs were invited to participate.

Measures

Helping behaviour

Fifteen items developed by Mazzer and Rickwood (Citation2013) assessed teachers' and coaches' engagement in the three types of helping behaviour. Promotion behaviour was measured by items such as ‘encourage inclusivity and participation of all young people in activities’ and ‘promote healthy lifestyle and exercise’. Prevention activities included ‘identify and stop bullying’ and ‘assist young people in learning how to manage stress’. Early intervention items included ‘notify and consult colleagues about concerns you have for a young person's mental health’ and ‘refer a young person to other sources of help (e.g., general practitioner, psychologist, counsellor)’. Participants indicated the extent to which they engage in each item within their role as a teacher or coach. Responses were given on a 5‐point scale, from 1 ‘never’ to 5 ‘very often’. The three subscales contained five items each and were calculated by averaging the relevant item scores.Footnote1 Higher scores indicated greater engagement in that type of helping behaviour. The promotion, prevention and early intervention subscales demonstrated adequate to high internal consistency, reporting Cronbach's alphas of .69, .82, and .88, respectively. Full methodology for the development of the behaviour items can be found in Mazzer and Rickwood (Citation2013).

Role perceptions

Four types of role perceptions used by McAllister et al. (Citation2007) were measured—perceived role breadth, instrumentality, efficacy, and discretion. For each of the five helping behaviours across each of the domains of promotion, prevention, and early intervention, role breadth was measured with the statement ‘This behaviour is an expected part of my job’. Similarly, instrumentality was measured by the statement ‘I see a direct connection between whether I engage in this behaviour and my outcomes at work’; efficacy was measured with the statement ‘I am completely confident in my capabilities when engaging in this behaviour’; and role discretion was measured by the statement ‘I have complete freedom to choose whether or not I engage in this behaviour’. Participants indicated their level of agreement with each of the four role perception statements for the 15 helping behaviour items. Responses were given on a 5‐point scale, from 1 ‘strongly disagree’ to 5 ‘strongly agree’. By averaging across the relevant items, 12 subscales were created, which all showed good internal reliability with Cronbach's alpha statistics ranging from .67 to .88 (see Table ).

Table 1. Reliability estimates and descriptive statistics of teachers' and coaches' helping behaviour and role perceptions

Data analysis

Data were screened and checked for normality. To explore differences between teachers' and coaches' role perceptions and PPEI helping behaviour, descriptive analyses and t‐tests were conducted using SPSS Version 21 (IBM Corp, Citation2012b). To examine and compare, for teachers and coaches, the effect of role perceptions in predicting PPEI behaviour, three multiple group path analyses were conducted using AMOS Version 21 (IBM Corp, Citation2012a).Footnote2

Multiple group path analysis examines group differences by testing for the equality of structural parameters across distinct groups and determines whether group membership moderates the effects specified in the model (Kline, Citation2010). This analytic approach was employed in order to simultaneously estimate and compare regression weights for the teacher and coach groups (Kline, Citation2010). Assessing equivalence across groups involves testing sets of parameters in an increasingly restrictive manner through hierarchical ordering of nested models, where each model constrains more parameters than the preceding model (Arbuckle, Citation2012; Byrne, Citation2004). Four nested models (unconstrained, structural weights, structural covariances, and structural residuals models) which tested three sets of structural parameters (regression paths, covariance of predictor variables, and covariance of residuals) were produced for each of the three path analyses in the current study (see Table ). Note that testing for the invariance of error parameters is considered an overly restrictive test of little importance (Byrne, Citation2004) and, consequently, the structural residuals models are not reported.

Results

Descriptives, t‐tests, and inter‐correlations

Assumption testing revealed minor violations of normality, however, the sample size was sufficiently large for tests to be robust against these violations. Descriptive statistics and t‐test comparisons are displayed in Table . Participants reported most frequent (‘often’) engagement in promotion behaviour, followed by prevention which was engaged in ‘sometimes’ to ‘often’. Early intervention behaviour was ‘rarely’ to ‘sometimes’ engaged in. t‐Tests revealed no significant difference between teachers' and coaches' engagement in promotion behaviour. Teachers engaged significantly more than coaches in both prevention and early intervention behaviour. Mean scores for role perception variables were all above the scale midpoint, indicating participants' role perceptions were generally supportive. t‐Tests indicated no significant differences between teachers' and coaches' role breadth, instrumentality, efficacy, and discretion for promotion behaviour. Teachers had significantly greater role breadth, instrumentality, and efficacy for prevention and early intervention behaviour than coaches. Coaches had significantly greater role discretion for prevention behaviour than teachers. No significant difference was found between teachers' and coaches' role discretion for early intervention behaviour.

Inter‐correlations for the total sample are displayed in Table . Promotion was strongly correlated with both prevention and early intervention. Prevention and early intervention had a very strong positive relationship. Helping behaviour measures were also strongly correlated with the hypothesised predictors of role breadth, instrumentality, and efficacy for their respective type of helping behaviour but not with discretion which had predominantly weak and non‐significant relationships with all other variables.

Multiple group path analysis 1: predicting promotion behaviour

The results of the multiple group analysis for promotion behaviour comparing the unconstrained and structural weights model yielded a chi‐square of χ2 = 5.63, df = 4, p = .228. This chi‐square was not significant, demonstrating no difference between the unconstrained and constrained models and, therefore, no significant difference in the effect of role perceptions predicting promotion behaviour for the teacher and coach groups.

As the structural weights were equivalent across groups, the structural covariances model was able to be interpreted.Footnote3 A non‐significant chi‐square (χ2 = 11.70, df = 10, p = .306) showed the structural covariances model did not fit the data significantly worse than the structural weights model. This result demonstrates teachers and coaches had similar inter‐correlations between role perceptions. Consistent with the correlations presented in Table , role perceptions were found to be strongly inter‐correlated, with the exception of discretion, in this model.

Table 2. Inter‐correlations

Interpreting the model for promotion

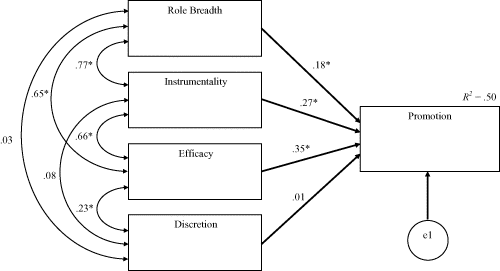

As groups did not significantly differ, the structural (regression) weights are presented using estimates for the total sample rather than for individual groups.Footnote4 The saturated model and estimates predicting promotion behaviour are illustrated in Fig. 2. This saturated model accounted for 50% of the variance in participants' promotion behaviour. Role efficacy was the strongest predictor of promotion behaviour, followed by instrumentality, and breadth. Discretion was not a significant predictor of promotion behaviour.

Multiple group path analysis 2: predicting prevention behaviour

The multiple group analysis for prevention behaviour revealed structural regression weights to be equivalent across the teacher and coach groups, as reflected by a non‐significant chi‐square (χ2 = 2.93, df = 4, p = .569) between the unconstrained and structural weights model.

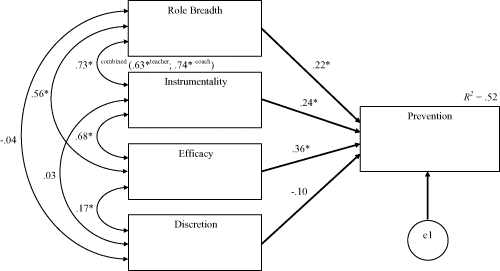

Given the equivalence of structural weights across groups, testing for the equality of structural covariances proceeded. The significant chi‐square (χ2 = 28.64, df = 10, p = .001) shows the structural covariances model fit significantly worse than the structural weights model, revealing inter‐correlations for role perceptions were not equivalent for teachers and coaches. Consequently, follow‐up tests to determine which individual paths significantly differed were indicated. Six additional nested models, constraining one covariance path at a time to be constant across groups, assuming the structural weights model to be correct, were conducted. These tests found that, while strong for both groups, the covariance between role breadth and instrumentality for prevention behaviour was significantly stronger (χ2 = 4.89, df = 1, p = .027) for coaches (r = .74) than teachers (r = .63). All other inter‐correlations in this model were consistent with those presented in Table .

Interpreting the model for prevention

The saturated model and estimates predicting prevention behaviour are presented in Fig. 3. The saturated model accounted for 52% of the variance in participants' prevention behaviour, with role efficacy shown to be the strongest predictor of prevention behaviour, followed by instrumentality, and breadth. Discretion was not a significant predictor of prevention behaviour.

Multiple group path analysis 3: predicting early intervention behaviour

A non‐significant chi‐square was obtained when comparing the unconstrained and the structural weights model for early intervention (χ2 = 5.17, df = 4, p = .271). This again demonstrates that role perceptions had similar influence in predicting early intervention behaviour for teachers and coaches. This allowed testing of the structural covariances model to proceed. A significant chi‐square (χ2 = 33.98, df = 10, p < .001) showed the structural covariances model fit significantly worse than the structural weights model, revealing role perceptions had differing inter‐correlations for the teacher and coach groups.

Follow‐up tests constraining individual covariance paths one at a time were again indicated. Six additional nested models were conducted. While the overall analysis of the structural covariance model had sufficient power to produce a significant chi‐square, no single path was found to differ significantly between the groups when individually tested. The role perceptions' inter‐correlations for this model were, therefore, consistent with those presented in Table .

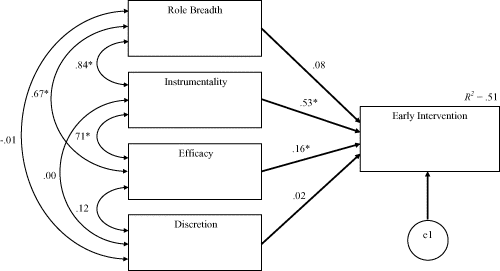

Interpreting the model for early intervention. The saturated model and estimates predicting early intervention behaviour are illustrated in Fig. 4. The saturated model accounted for 51% of the variance in participants' early intervention behaviour. Role instrumentality was overwhelmingly the strongest predictor of early intervention behaviour, followed by efficacy. Role breadth and discretion were not significant predictors of early intervention behaviour.

Discussion

This study examined the influence of role perceptions on teachers' and coaches' engagement in PPEI behaviour for young people's mental health. Role efficacy, instrumentality, and breadth significantly influenced teachers' and coaches' helping behaviour, whereas role discretion did not. These effects did not vary between teachers and coaches; while teachers' role perceptions for supporting young people's mental health tended to exceed coaches', the extent to which their involvement in helping behaviour from these perceptions could be predicted was comparable.

In contrast to our first hypothesis and McAllister et al. (Citation2007), role breadth was not the strongest predictor of helping behaviour; efficacy and instrumentality had stronger effects. The reduced influence of role breadth may be a consequence of the type of professionals included in the sample. Teachers and coaches are often caring in nature, which leads to these career choices. They may be motivated by more intrinsic values (e.g., helping young people in need) than other employees, such as the engineers recruited in McAllister et al. (Citation2007). These intrinsic values may drive engagement in helping behaviour more than formal role expectations or duties for teachers and coaches. While not the strongest perception in predicting helping behaviour, role breadth still had an important influence on helping behaviour. Mazzer et al. (Citation2012) found teachers to have greater awareness of guidelines and structured procedures for assisting young people's mental health than coaches who reported receiving less guidance in this area. Coaches, and teachers to a lesser extent, may benefit from the development of clearer role requirements for supporting young people's mental health.

Role efficacy was the strongest predictor of both promotion and prevention behaviour. Surprisingly McAllister et al. (Citation2007) did not find self‐efficacy to predict helping behaviour, however, current findings are congruent with much previous research demonstrating that self‐efficacy greatly affects behaviour (Beauchamp et al., Citation2002; Ross, Bradley Cousins, & Gadalla, Citation1996). Previous research has found teachers and coaches to perceive deficits in their skills and knowledge of mental health‐related areas (Graham et al., Citation2011; Mazzer et al., Citation2012). Mazzer and Rickwood (Citation2013, unpublished data) found that Canberra‐based teachers had generally received some training in mental health‐related areas, but that many desired and needed further training and support. Indeed, a number of studies of teachers' views on supporting mental health have revealed a common desire among teachers for further mental health training and support (Askell‐Williams, Lawson, & Murray‐Harvey, Citation2007; Cohall et al., Citation2007).

The past 15 years have seen significant developments in school‐based mental health, and a number of programs for teacher support have emerged (Weare & Nind, Citation2011). MindMatters has been the main support in Australia for teachers, providing teacher education, classroom activities, and tools to support a whole‐school approach to mental health (MindMatters, Citation2009). ResponseAbility provides resources specific to pre‐service teacher education (Hunter Institute of Mental Health, Citation2012). Teacher education and resources for mental health are also available from the ReachOut Teachers Network (Inspire Foundation, Citation2013), HeadStrong (Black Dog Institute, Citation2013), and SenseAbility (beyondblue, Citation2013). However, while there is a growing range of high‐quality resources available, they are not routinely incorporated within tertiary teacher training programs nor ongoing professional development.

Coaches have received less attention and have fewer available training options. However, Mental Health First Aid (MHFA), which aims to increase mental health literacy (Kitchener & Jorm, Citation2002), has been applied to both teachers and coaches with promising results (Jorm, Kitchener, Sawyer, Scales, & Cvetkovski, Citation2010; Pierce, Liaw, Dobell, & Anderson, Citation2010). MHFA training was found to improve participants' knowledge of mental disorders, capacity to recognise mental illness, and confidence in helping someone with a mental health problem. Instrumentality had a significant effect on helping behaviour and was particularly influential in early intervention. This finding was consistent with McAllister et al. (Citation2007) who also found instrumentality to predict employees' interpersonal helping behaviour. Highlighting and reinforcing to teachers and coaches the impact that helping behaviours have in leading to desired and rewarding outcomes, such as improved mental health and well‐being for young people, and the positive contribution that relatively small actions (like encouraging young people to participate in activities) can have for a young person's mental health, are ways of increasing instrumentality and motivating behaviour. Furthermore, explicitly including actions that support young people's mental health in key performance indicators, performance and development reviews, and formal job descriptions would further encourage teachers' and coaches' involvement in such behaviour.

Role discretion did not significantly influence PPEI behaviour for teachers or coaches. This result is consistent with McAllister et al. (Citation2007) who found, while role discretion did influence some types of behaviours, it did not predict interpersonal helping behaviour. The extent to which people perceive that they can choose to carry out helping behaviour within their work role does not influence their performing such behaviours.

Behaviour that supports the promotion of mental health and prevention of mental illness was affected by role perceptions in a similar way, but a different predictive pattern was revealed for early intervention behaviour. Role efficacy was the strongest predictor of both promotion and prevention behaviour, whereas early intervention was predominantly influenced by role instrumentality. Promotion and prevention both aim to act before the onset of a mental illness (Mrazek & Haggerty, Citation1994), whereas early intervention actions are more directly related to assisting mental health problems, which may require a different set of skills and be driven by alternate or additional factors. Current results showed both teachers and coaches felt less capable to carry out early intervention behaviours which may explain the greater influence that instrumentality had for these activities; additional motivation may be required for teachers and coaches to carry out early intervention actions due to their reduced confidence in their ability to perform them effectively. The link between helping behaviour and rewarding outcomes may be more important in this area and could provide the additional motivation required to perform the behaviour.

Strength and limitations

While the results of the current study have implications for the role of teachers and coaches in supporting youth mental health, it is important to note that the volunteer nature of the sample may affect the findings by including participants particularly committed to youth mental health. Nevertheless, one of the strengths of the study was that the recruitment process targeted a variety of sites and captured a diverse range of participants across ages, experience, subjects taught, and sports coached, which should attenuate this limitation. Future research could, however, investigate other participant characteristics, such as gender as there may be important differences between the ways that males and females in these roles engage in such helping behaviour. Teachers' and coaches' level of previous training in mental health is also likely to be influential factor, and this was not considered in the current study.

A further limitation stemmed from the lack of an available measure of PPEI activities. The items developed by Mazzer and Rickwood (Citation2013) needed to be relevant to different occupation groups, and were derived directly from discussions with teachers and coaches. However, the measure requires further validation beyond this initial study. A significant strength, however, was the simultaneous examination of the influence of teachers' and coaches' role perceptions on helping behaviour. Finding that these role perceptions had similar predictive qualities across the occupational groups enhances the generalisability of the current findings to apply to other relevant community‐based roles, such as youth workers. Future research should continue to investigate the range of activities that adults in community‐based roles perform to support young people's mental health.

Conclusion

Community‐based adults can be valuable sources of support for young people's mental health. This study revealed that role perceptions are influential in predicting teachers' and coaches' involvement in supporting young people's mental health through promotion, prevention, and early intervention. Both occupations are more likely to perform helping behaviour when they perceive themselves as capable, when the behaviour is linked to desired outcomes and rewards, and when the actions are expected or required within their work role. Assisting adults in community‐based roles to engage in promotion, prevention, and early intervention may strengthen and diversify young people's access to mental health support and help to reduce the burden of mental health problems.

Notes

1. A confirmatory factor analysis has not been performed to confirm categorisation of the items within the subscales of this measure. The reason for this was that the scale was designed to allow for exploration of the boundaries of activities within teachers' and coaches' roles. Care was taken to ensure inclusion of items that were likely to capture a range of endorsements from teachers and coaches, that is, including activities that were likely to be performed frequently as well as activities that were less frequent. Therefore, items would not have been expected to load similarly within PPEI categories but rather would load according to frequency of endorsement.

2. Saturated models were used for the three multiple group analyses as the current research hypotheses were concerned with assessing group invariance of regression weights predicting behaviour rather than specifying the model fit.

3. When the structural weights model is not accepted as equivalent across groups, subsequent models cannot be interpreted (Arbuckle, Citation2012).

4. All models that find no significant group difference are presented with the total sample estimates.

References

- Arbuckle, J. (2012). IBM SPSS Amos 21 User's Guide. Mount Pleasant, SC: Amos Development Corporation.

- Askell‐williams, H., Lawson, M. J., & Murray‐harvey, R. (2007). Teaching and learning about mental illnesses: An Australian perspective. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 9(4), 26–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14623730.2007.9721846

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2010). Mental health of young people, 2007. (Cat no. 4840.0.55.001). Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Sports Commission (2010). Participation in exercise, recreation and sport (annual report). Canberra: ASC.

- beyondblue. (2013). SenseAbility communications portal. Retrieved November 12, 2012, from http://www.beyondblue.org.au/resources/schools‐and‐universities/secondary‐schools‐and‐tertiary/senseability

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self‐efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033‐295x.84.2.191

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Edgewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Bandura, A., & Mcclelland, D. C. (1977). Social learning theory. New York: General Learning Press.

- Beauchamp, M. R., Bray, S. R., Eys, M. A., & Carron, A. V. (2002). Role ambiguity, role efficacy, and role performance: Multidimensional and mediational relationships within interdependent sport teams. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 6(3), 229–242. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/1089‐2699.6.3.229

- Black Dog Institute. (2013). HeadStrong. Retrieved November 14, 2012, from http://www.headstrong.org.au/

- Byrne, B. M. (2004). Testing for multigroup invariance using Amos graphics: A road less traveled. Structural Equation Modeling, 11(2), 272–300. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1102_8

- Cobanoglu, C., & Cobanoglu, N. (2003). The effect of incentives in web surveys: Application and ethical considerations. International Journal of Market Research, 45(4), 475–488.

- Cohall, A. T., Cohall, R., Dye, B., Dini, S., Vaughan, R. D., & Coots, S. (2007). Overheard in the halls: What adolescents are saying, and what teachers are hearing, about health issues. Journal of School Health, 77(7), 344–350. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746‐1561.2007.00218.x

- Commonwealth of Australia (2009). Fourth national mental health plan. An agenda for collaborative government action in mental health 2009–2014. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing.

- Coyle‐shapiro, J. A. M., Kessler, I., & Purcell, J. (2004). Exploring organizationally directed citizenship behaviour: Reciprocity or ‘it's my job. Journal of Management Studies, 41, 85–106. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467‐6486.2004.00422.x

- Donovan, R. J., Henley, N., Jalleh, G., Silburn, S., Zubrick, S., & Williams, A. (2006). The impact of mental health in others of those in a position of authority: A perspective of parents, teachers, trainers, and supervisors. Australian e‐Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health, 5, 60–66. doi:https://doi.org/10.5172/jamh.5.1.60

- Graham, A., Phelps, R., Maddison, C., & Fitzgerald, R. (2011). Supporting children's mental health in schools: Teacher views. Teachers & Teaching, 17, 479–496. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2011.580525

- Hunter Institute of Mental Health. (2012). ResponseAbility, about the resource. Retrieved October 24, 2012, from http://www.responseability.org/secondary

- IBM Corp (2012a). IBM SPSS Amos Statistics for Windows (version 21). Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

- IBM Corp (2012b). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 21). Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

- Inspire Foundation. (2013). Reachout.com professionals, teaching resources. Retrieved November 12, 2012, from http://au.professionals.reachout.com/Professional‐development/Teachers/Teaching‐resources#

- Jorm, A. F., Kitchener, B. A., Sawyer, M. G., Scales, H., & Cvetkovski, S. (2010). Mental health first aid training for high school teachers: A cluster randomized trial. BMC Psychiatry, 10:51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471‐244X‐10‐51

- Kitchener, B. A., & Jorm, A. F. (2002). Mental health first aid training for the public: Evaluation of effects on knowledge, attitudes and helping behavior. BMC Psychiatry, 2:10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471‐244X‐2‐10

- Kline, R. B. (2010). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford press.

- Mazzer, K. R., & Rickwood, D. J. (2013). Community‐based roles promoting youth mental health: Comparing the roles of teachers and coaches in promotion, prevention and early intervention. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 15(1), 29–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14623730.2013.781870; (ahead of print).

- Mazzer, K. R., Rickwood, D. J., & Vanags, T. (2012). Teachers and sports coaches supporting young people's mental health: Promotion, prevention, and early intervention. Paper presented at the International Conference of Applied Psychology and Behavioral Science, Paris, France.

- Mcallister, D. J., Kamdar, D., Morrison, E. W., & Turban, D. B. (2007). Disentangling role perceptions: How perceived role breadth, discretion, instrumentality, and efficacy relate to helping and taking charge. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(5), 1200–1211. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0021‐9010.92.5.1200

- MindMatters. (2009). MindMatters. Retrieved October 24, 2012, from http://www.mindmatters.edu.au/default.asp

- Morrison, E. W. (1994). Role definitions and organisational citizenship behavior: The importance of the employee's perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 37(6), 1543–1567. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/256798

- Mrazek, P. J., & Haggerty, R. J. (1994). Reducing risks for mental disorders: Frontiers for preventive intervention research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- Organ, D. W. (1997). Organizational citizenship behavior: It's construct clean‐up time. Human Performance, 10, 85–97. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327043hup1002_2

- Parker, S. K. (2007). ‘That is my job’. Human Relations, 60(3), 403–434. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726707076684

- Pierce, D., Liaw, S.‐T., Dobell, J., & Anderson, R. (2010). Australian rural football club leaders as mental health advocates: An investigation of the impact of the coach the coach project. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 4, 10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1752‐4458‐4‐10

- Rickwood, D., Deane, F. P., Wilson, C. J., & Ciarrochi, J. (2005). Young people's help‐seeking for mental health problems. Australian e‐Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health, 4(3), 218–251. doi:https://doi.org/10.5172/jamh.4.3.218

- Ross, J. A., Bradley cousins, J., & Gadalla, T. (1996). Within‐teacher predictors of teacher efficacy. Teaching and Teacher Education, 12(4), 385–400. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0742‐051X(95)00046‐M

- Weare, K., & Nind, M. (2011). Mental health promotion and problem prevention in schools: What does the evidence say? Health Promotion International, 26(Suppl. 1), i29–i69. doi:0.1093/heapro/dar075