Abstract

The present study aimed to examine how perfectionism is contributing to social anxiety and its cognitive processes of post‐event rumination and self‐perception of performance following a speech task. Forty‐eight undergraduate students completed measures of perfectionism and trait social anxiety prior to performing a 3‐min impromptu speech task. Immediately following the speech task, participants rated their state anxiety and self‐perception of performance, and 24-hr later, their level of post‐event rumination was measured. Structural equation modelling revealed that perfectionism, in the form of socially prescribed perfectionism and doubts about actions, directly influences trait social anxiety, and indirectly influences post‐event rumination and self‐perception of performance through its relationship with trait social anxiety and state anxiety. This is the first study to investigate how perfectionism is contributing to social anxiety and its cognitive processes. The findings of this study provide evidence in support of the potential predictive role of perfectionism in social anxiety.

Social anxiety disorder (SAD), characterised by ‘a marked and persistent fear of social or performance situations in which embarrassment may occur’ (American Psychiatric Association [APA], Citation2000, p. 450), is a highly prevalent disorder motivated by a fear of negative evaluation by others relating to one's own social performance. Socially anxious individuals tend to view social situations as dangerous, which inevitably provokes anxiety reactions as well as avoidance behaviours (APA, Citation2000). Perfectionism, a personality trait associated with a broad range of psychopathology including social anxiety (Egan, Wade, & Shafran, Citation2011; Hewitt & Flett, Citation1991), is commonly defined as a tendency to establish excessively high personal standards for performance, along with a tendency to be overly critical upon one's failure to meet those standards (Frost, Marten, Lahart, & Rosenblate, Citation1990). Although well‐known cognitive‐behavioural models of SAD (e.g., Clark & Wells, Citation1995; Rapee & Heimberg, Citation1997) do not specify perfectionism per se, the conceptualisations of several cognitive concepts within these models seem to fit with the descriptions of specific dimensions of maladaptive perfectionism. For example, in some of the earliest literature to name perfectionism (e.g., Hamachek, Citation1978), it is suggested that perfectionists place emphasis on performance, are overly sensitive to rejection, and excessively concerned with approval from others. These themes are mirrored in models of social anxiety (e.g., Clark & Wells, Citation1995; Rapee & Heimberg, Citation1997).

Schlenker and Leary (Citation1982), in their self‐presentational model of social anxiety, propose social anxiety as a secondary emotion arising in part from doubts about the person's ability to make a desired social impression and personality characteristics that increase self‐presentational concerns, such as excessively high standards for social performance (e.g., perfectionistic standards). In specific reference to standards of performance, Clark and Wells (Citation1995) suggest that socially anxious individuals hold high standards for themselves in a social situation, reflecting perfectionistic personal standards (the requirement for the self to be perfect; Hewitt & Flett, Citation1991), and self‐oriented perfectionism (setting excessively high standards for one's own performance; Frost et al., Citation1990). Rapee and Heimberg (Citation1997), on the other hand, suggest that socially anxious individuals make predictions that the ‘audience’ expects high standards for their own performance, reflecting socially prescribed perfectionism (SPP; the perception that others require oneself to be perfect; Hewitt & Flett, Citation1991). More recently, Hofmann (Citation2007) proposed a comprehensive maintenance model of SAD in which the theoretical perspectives of both Clark and Wells (Citation1995) and Rapee and Heimberg (Citation1997) are incorporated. According to Hofmann (Citation2007), social anxiety exists in a bi‐directional relationship with an overestimation of the social standards and an underestimation of one's ability to achieve such social goals, both of which reflect SPP and doubts about actions (DAA; the extent to which people doubt their ability to accomplish tasks; Frost et al., Citation1990), respectively.

Supporting these notions, there is a large body of evidence showing that certain aspects of perfectionism are associated with social anxiety. For example, studies have shown that socially anxious individuals perceive the expected performance standards to be much higher than what non‐anxious controls do (e.g., Moscovitch & Hofmann, Citation2007; Wallace & Alden, Citation1995), and are more likely to believe that their ability would fall short of what others expected (i.e., they doubt their abilities to meet standards; Wallace & Alden, Citation1995). More specifically, research has supported the perspectives of Hofmann (Citation2007) and Rapee and Heimberg (Citation1997) by showing that SPP, rather than self‐oriented perfectionism or personal standards, is higher in those with SAD when compared to non‐clinical controls (e.g., Antony, Purdon, Huta, & Swinson, Citation1998; Juster et al., Citation1996). Additionally, in line with Hofmann's (Citation2007) model, research has consistently found DAA to be higher in those with SAD than in non‐clinical controls (Antony et al., Citation1998; Juster et al., Citation1996).

Although a vast amount of research provides support for the relationships between certain domains of perfectionism and social anxiety and there is consistency in the literature that individuals with social anxiety are more perfectionistic, to date it has been difficult to draw causal conclusions. It is possible that perfectionistic cognitions may lead people to believe that others expect more from them than what they perceive they are capable of giving, and this may lead to feelings of social inadequacy (Frost, Glossner, & Maxner, Citation2010). Conversely, it is also possible that holding the belief that one is socially inadequate may lead someone to become more perfectionistic in social situations in order to try and lift their standards of performance to avoid negative evaluation (Frost et al., Citation2010).

Nevertheless, perfectionism has long been suggested as a personality trait, and its impact on emotion and behaviour has been made apparent (Egan et al., Citation2011; Hamachek, Citation1978). In a recent review of clinical perfectionism, Egan et al. (Citation2011) demonstrated that maladaptive perfectionism is elevated in many disorders including anxiety disorders and proposed perfectionism as a transdiagnostic process. In their argument, perfectionism not only occurs across different diagnoses but also serves as a risk factor and/or maintaining mechanism contributing to the aetiology and maintenance of different disorders, including social anxiety. In line with this view, Wirtz et al. (Citation2007) found perfectionism to be a predictor of the cortisol response to stress, whereby perfectionistic cognitions contributed independently to stress‐induced bodily responses when participants were placed in a socially evaluative situation. This further supports the view of Schlenker and Leary (Citation1982) that social anxiety may be a symptom of perfectionism. In addition, perfectionism has been shown to predict depression, a highly coexisting emotion with social anxiety (APA, Citation2000), over a 12‐year period (Hewitt, Flett, & Ediger, Citation1996).

Based on these suggestions, the present study proposes perfectionism as a risk factor to social anxiety and aims to examine how perfectionism, in the form of both SPP and DAA, contributes to social anxiety and its cognitive processes. Specifically, we focus on post‐event rumination and self‐perception of performance.

Post‐event rumination is conceptualised as repetitive, negative‐laden thoughts related to perceived inadequacies of the self (Clark & Wells, Citation1995). According to Clark and Wells (Citation1995), following a social situation those experiencing social anxiety selectively retrieve, and repeatedly think about, negative information relating to themselves and their social performances. The repetitive review of such negative‐laden thoughts serves to maintain the socially anxious individuals negative perceptions of themselves, thereby maintaining their sense of inadequacy, and in turn, their anxiety (Clark & Wells, Citation1995). Correlational and empirical studies have reliably found that socially anxious individuals engage in elevated levels of rumination (for a review, see Brozovich & Heimberg, Citation2008). Recent research aiming to investigate factors that may impact on rumination has demonstrated that in addition to trait social anxiety, self‐perception of performance pertaining to a certain social event (e.g., public speaking) is a key factor contributing to rumination (Chen, Rapee, & Abbott, Citation2013).

Negative self‐perception of performance is described as subjective appraisal of one's own performance that is negatively biased (Rapee & Abbott, Citation2007). Such negative appraisal stems from an underestimation or negative perception of one's social skills instead of an actual deficit in their social skills, and it is this perception that produces social fear (Rapee & Lim, Citation1992). Studies have shown that socially anxious individuals consistently appraise their performance more negatively than non‐socially anxious controls (Abbott & Rapee, Citation2004; Rapee & Lim, Citation1992).

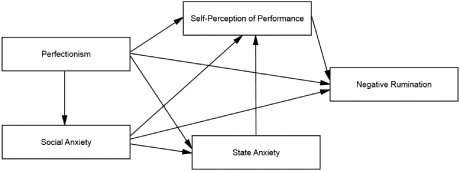

Taking these findings into account, the current study aimed to investigate whether perfectionism would influence the relationships between these factors. The literature has demonstrated that particular dimensions of perfectionism (e.g., SPP or DAA) are associated with social anxiety (Antony et al., Citation1998; Juster et al., Citation1996), rumination (Blankstein & Lumley, Citation2008; Randles, Flett, Nash, McGregor, & Hewitt, Citation2010), and negative self‐evaluation of performance (Kim, Lundh, & Harvey, Citation2002; Shafran, Cooper, & Fairburn, Citation2002). However, to date, these relationships have been examined in isolation. An integrated perspective on how perfectionism may influence social anxiety and its cognitive processes is needed. We proposed a model (see Fig. 1) by integrating perfectionism, specifically SPP and DAA, into the existing findings (e.g., Chen et al., Citation2013; Rapee & Abbott, Citation2007). The direction of the paths between trait social anxiety and rumination were hypothesised based on previous research results (Chen et al., Citation2013; Rapee & Abbott, Citation2007), and temporal relationships (rumination was measured 24-hr after the other variables). We also expected direct paths from perfectionism to self‐perception of performance and state anxiety. This was based first on Shafran et al.'s (Citation2002) suggestion that negative evaluation of performance is influenced by perfectionism and second on Lo and Abbott's (Citation2013) suggestion that maladaptive perfectionism increases emotional distress and task anxiety. We expected our results would provide insight into the relationships between perfectionism and social anxiety as well as its cognitive processes, and further inform the treatment for SAD.

Overview of the current study

The aim of the current study was to examine how perfectionism, in the form of SPP and DAA, contributes to social anxiety and its cognitive processes. Specifically, we focus on the influence of perfectionism on trait social anxiety, rumination, self‐perception of performance, and state anxiety. Figure 1 shows our proposed model. We hypothesised that (1) perfectionism directly influences trait social anxiety, rumination, state anxiety, and self‐perception of performance, and (2) perfectionism influences rumination indirectly through its relationships with trait social anxiety, state anxiety, and self‐perception of performance. Given that social anxiety research using non‐clinical populations can be used to inform investigations of clinical populations (Rapee & Heimberg, Citation1997), the present study focused on social anxiety in an undergraduate student sample. Participants were invited to attend an experimental session where they were asked to perform an impromptu speech task. After completing questionnaires on trait social anxiety and perfectionism, participants delivered the speech and rated their state anxiety and self‐perception of performance immediately following the task. Rumination was measured 24-hr after the speech task. The relationships between these factors were examined using structural equation modelling (SEM).

Method

Participants

Participants were 48 first‐year undergraduate psychology students from Flinders University aged between 18 and 55 (M = 23.98, standard deviation (SD) = 9.05; 34 female). Participants were recruited as part of a first‐year volunteer research pool in which participation earned course credit. Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Research Ethics Committee, and informed written consent was obtained from each participant before participation commenced.

Measures

Brief fear of negative evaluation scale–straightforward items (BFNE‐S)

The BFNE‐S was used to assess the participants' trait social anxiety. The original BFNE scale (Leary, Citation1983) is a 12‐item self‐report measure of fear related to negative evaluation from others. Rodebaugh et al. (Citation2004) and Weeks et al. (Citation2005) have reported that the eight straightforwardly worded items are more reliable, and valid indicators of fear of negative evaluation than the 12‐item measure which includes four reverse‐scored items. The BFNE‐S uses a 5‐point rating scale (1: not at all characteristic of me; 5: extremely characteristic of me). An example item is ‘I am afraid that others will not approve of me’. Higher scores represent a greater fear of negative evaluation. The BFNE‐S has demonstrated excellent internal consistency (all αs > .90; Rodebaugh et al., Citation2004; Weeks et al., Citation2005) and good convergent and discriminant validity (Weeks et al., Citation2005). Internal consistency in the current sample was .95.

Doubts about actions (DAA)

The DAA subscale from the Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (Frost et al., Citation1990) consists of four items with a 5‐point Likert‐type rating scale (1: strongly disagree; 5: strongly agree). An example item is ‘even when I do something very carefully, I often feel that it is not quite right’. Higher scores represent a greater degree of perfectionism. This subscale has good internal consistency (α = .77 and .81; Frost et al., Citation1990; Shumaker & Rodebaugh, Citation2009, respectively) and convergent validity (Frost et al., Citation1990). Internal consistency in the current sample was .81.

Socially prescribed perfectionism (SPP)

The SPP subscale from the Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (Hewitt & Flett, Citation1991) consists of 15‐items with a 7‐point Likert‐type rating scale (1: strongly disagree; 7: strongly agree). An example item is ‘the people around me expect me to succeed at everything I do’. The subscale demonstrates high internal consistency (α = .87) and good convergent validity (Hewitt & Flett, Citation1991). Internal consistency in the current sample was .93. Higher scores on this subscale indicate a greater degree of perfectionism.

State anxiety rating (SAR)

The 10‐item SAR (Rapee & Abbott, Citation2007) was used to assess state anxiety experienced during the speech task on a 5‐point rating scale (0: not at all; 4: extremely). An example item is ‘I felt nervous during the speech’. Higher scores on this measure represent higher state anxiety. This measure has demonstrated excellent internal consistency both in previous studies (α = .96 and .97; Chen et al., Citation2013; Rapee & Abbott, Citation2007, respectively) and in the current sample (α = .93).

Speech performance questionnaire (SPQ)

The SPQ (Rapee & Lim, Citation1992) was used to assess the participants’ subjective perception of their speech on a 5‐point rating scale (0: not at all; 4: very much). The 17‐item measure includes 12 specific performance items, for example ‘kept eye contact with the audience’ and five global performance items, for example, ‘appeared nervous’. Higher scores represent a more negative perception of performance. Good internal consistency is shown both in previous studies (α = .84 and .92; Abbott & Rapee, Citation2004; Chen et al., Citation2013, respectively) and in the current sample (α = .90).

Thoughts questionnaire (TQ)

The TQ (Abbott & Rapee, Citation2004; Edwards, Rapee, & Franklin, Citation2003) is a measure of both positive and negative rumination specifically related to a speech task. The 24‐item scale (15 negative; nine positive) asked respondents to rate how often they thought about various aspects of the speech during the past 24-hr using a 5‐point rating scale (0: never; 4: very often). Given that social anxiety is positively related to negative rumination but not positive rumination (Abbott & Rapee, Citation2004), only the negative rumination items (15 items) were used in the present study. An example item is ‘I looked stupid’. Higher scores indicate a greater degree of negative rumination. Internal consistency for the negative rumination subscale was excellent in previous studies (all αs > .90; Abbott & Rapee, Citation2004; Chen et al., Citation2013; Rapee & Abbott, Citation2007) and in the present sample (α = .94).

Procedure

Participants were first asked to complete measures of perfectionism and trait social anxiety. Following this, participants were advised to deliver a 3‐min impromptu speech about a chosen topic to a video camera, and the video of their speech would be evaluated by an audience after the session. Examples of the speech topics included my favourite book/movie, my first pet, and university life. Participants were given 2-min to mentally prepare for their speech and started the speech when ready. Participants who stopped the speech in less than 3-min were briefly encouraged to continue, but if they refused, the speech was stopped at this time, and measures of state anxiety and self‐perception of performance were administered. Finally, participants received an email after the in‐person session which instructed them to complete the rumination questionnaire in 24-hr from the completion time of the in‐person session and return via email. One hundred per-cent of participants returned the rumination questionnaire with varied completion time ranging from 4 to 165 hr (M = 38.27, SD = 33.30).

Statistical analyses

Means, standard deviations, range, and bivariate Pearson correlations for all variables were calculated. Following this, in order to examine the hypothesised model (Fig. 1), SEM was conducted with IBM SPSS Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS) version 22. In addition to the commonly used chi‐square, several goodness of fit indices were used to evaluate the overall model fit. Hu and Bentler (Citation1999) recommend suitable indices for small sample sizes (n < 250), including the comparative fit index (CFI) and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) in order to reduce Type I and Type II errors. The CFI assesses model fit relative to other models with values greater than .95 being indicative of a good fitting model (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). The SRMR is the average differences between the residuals of the sample covariance matrix and the hypothesised covariance model (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2013). Values of .08 or less are deemed acceptable (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). In addition, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) with its 90% confidence intervals was reported. The RMSEA estimates a lack of fit compared to a perfect model with values of .06 or less indicating an acceptable fit while values larger than .10 represent a poor model fit (Browne & Cudeck, Citation1993; Hu & Bentler, Citation1999).

Multiple mediation procedures, using the SPSS macro PROCESS developed by Hayes (Citation2013), were carried out to assess the indirect effect of the proposed models (i.e., SPP and DAA on rumination through trait social anxiety, state anxiety, and self‐perception of performance), as well as supplementary mediation models. PROCESS (Hayes, Citation2013) can be used to test direct and indirect effects of variables in complex statistical analyses. The macro also calculates bootstrap confidence intervals around the indirect effect on the basis of k bootstrap re‐samples. Simple mediation was conducted using PROCESS, Model 4, and multiple mediation was undertaken using PROCESS, Model 6.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table displays the means, standard deviations, range, and intercorrelation matrix of all variables included in the model. Overall, correlations between all variables included in the model were moderate to strong and statistically significant with the exception of the correlations between DAA and state anxiety and DAA and self‐perception of performance which were small and non‐significant.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and intercorrelation matrix of variables included in the model

Model testing

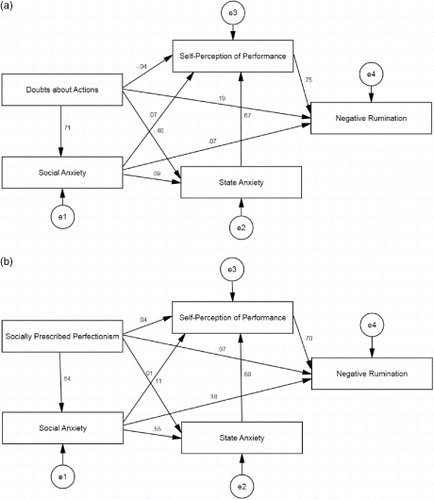

Based on the hypothesised model presented in Fig. 1,Footnote1 we tested the direct paths from SPP and DAA separately to trait social anxiety, state anxiety, self‐perception of performance, and rumination (see Tables & ). Both models showed a good fit to the data (see Table , Models a & b), with non‐significant chi‐square and excellent CFI, SRMR, and RMSEA. However, several paths were not significant (see Tables & ; Fig. 2a & 2b). Table (Model a & b) shows the indirect effects examined and their bootstrap bias‐corrected 95% confidence intervals (with 5,000 re‐samples). All indirect relations regarding SPP were statistically significant (i.e., the lower limit of the 95% confidence interval did not span zero). However, the path from DAA to rumination through self‐perception of performance, DAA to self‐perception of performance through state anxiety, and DAA to rumination through both state anxiety and self‐perception of performance were not significant. Of primary interest, however, is the significant indirect effect of the entire model (i.e., perfectionism on rumination through trait social anxiety, state anxiety, and self‐perception of performance).

Table 2. Regression weights for model a

Table 3. Regression weights for model b

Table 4. Fit indices for models a and b

Figure 2. The final SEM model for the role of DAA in social anxiety and its cognitive processes (a). The final SEM model for the role of SPP in social anxiety and its cognitive processes (b).

Table 5. Indirect effects for mediation models

In summary, the current results showed that as expected SPP and DAA directly influenced trait social anxiety, but contrary to predictions did not directly influence rumination or self‐perception of performance and only DAA influenced state anxiety directly. However, consistent with the hypothesised model, SPP and DAA indirectly influenced rumination through trait social anxiety or in sequence through trait social anxiety, state anxiety, and self‐perception of performance. Further, SPP and DAA influenced self‐perception of performance through trait social anxiety or serially through trait social anxiety and state anxiety. Additional findings showed that trait social anxiety did not directly influence rumination but did have an indirect influence through its relationship with state anxiety and self‐perception of performance.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to examine how perfectionism, in the form of SPP and DAA, contributes to social anxiety and its cognitive processes. As expected, we found that both SPP and DAA influenced trait social anxiety directly. This finding is consistent with previous studies showing the relationship between these dimensions of perfectionism and social anxiety (Antony et al., Citation1998; Bieling & Alden, Citation1997; Juster et al., Citation1996), and the potentially predictive role of perfectionism in social anxiety (Egan et al., Citation2011; Schlenker & Leary, Citation1982; Wirtz et al., Citation2007). The current study has gone a step further by considering perfectionism within the context of a speech task, and in doing so, we have implicated perfectionism as a potential predictor of social anxiety. Our findings provide preliminary data to support the proposal of Egan et al. (Citation2011) that perfectionism may be a risk factor for social anxiety.

Although a significant correlation between perfectionism and rumination was found in the current study, which is convergent with previous studies (Blankstein & Lumley, Citation2008; Randles et al., Citation2010), when placed in the model with social anxiety, this direct relationship was not maintained. An explanation for the variation in results is that the current study assessed rumination in relation to a specific social task rather than a general level of rumination seen in previous studies (Blankstein & Lumley, Citation2008; Randles et al., Citation2010). This inconsistent finding suggests that when trait social anxiety is taken into account, perfectionism may be indirectly influencing rumination through trait social anxiety. The mediation analysis revealed that perfectionism was indeed influencing rumination in this way.

Similarly, opposing our hypothesis, neither SPP nor DAA directly influenced self‐perception of performance. Literature suggests that those with perfectionism tend to evaluate their performance in a biased way (Shafran et al., Citation2002). Although weak correlations between perfectionism and self‐evaluation of speech were found in Kim et al. (Citation2002), in our study, when perfectionism and self‐perception of performance are considered together with trait social anxiety, a direct influence from perfectionism to self‐perception of performance does not appear. However, mediation analysis revealed the relationship between perfectionism and self‐perception of performance occurs through trait social anxiety and serially through trait social anxiety and state anxiety for both SPP and DAA. These findings suggest that in the social anxiety context, the impact of perfectionism on negative self‐perception of performance should be considered along with the degree of the individual's trait social anxiety and situational anxiety symptoms.

In the same vein, contrary to expectations only DAA but not SPP influenced state anxiety directly. The initial unexpected non‐significant correlation between DAA and state anxiety changed when it was integrated in the entire model, that is, DAA played a different role in affecting state anxiety in the context of a social task. In contrast, the initial significant correlation between SPP and state anxiety disappeared when it was considered in the model with social anxiety. Lo and Abbott (Citation2013) proposed that for maladaptive perfectionists, high expected standards of performance and perceived failure to meet such standards leads to emotional distress and in‐situation task anxiety. Our results suggest that during a specific social situation, it is more likely that doubting one's ability rather than the perception of unachievable high standards triggers one's in‐situational anxiety. However, results of the mediation analyses suggest that both DAA and SPP indirectly influence in‐situational anxiety via their impact on trait social anxiety, once again pointing to the interactive roles that trait social anxiety and perfectionism may play in their contribution to situation anxiety.

Based on Hofmann's (Citation2007) model of social anxiety, we expected an indirect effect of perfectionism on rumination through trait social anxiety, state anxiety, and self‐perception of performance. Consistent with our predictions, both SPP and DAA indirectly influenced rumination pertaining to an anxiety‐provoking speech task serially through its relationship with these factors. Empirical evidence has supported the relationships between trait social anxiety, state anxiety, self‐perception of performance, and rumination (e.g., Chen et al., Citation2013). Our study extended these findings by integrating perfectionism and examining the contribution of SPP and DAA to these relationships. Taken together, our results suggest that perfectionism does not only influence trait social anxiety directly but also state anxiety and the cognitive processes such as self‐perception of performance and rumination through its relationship with trait social anxiety. The indirect pathways from perfectionism to state anxiety, self‐perception of performance, and rumination through trait social anxiety suggest that perfectionism impacts on social anxiety, which, in turn, leads to the later anxiety symptoms and cognitive processes including self‐perception of performance and rumination.

Findings of this study should be considered in light of potential limitations. First, the small sample size limited the generalization of the findings. Second, the study relied on self‐report measures and assessed only a few of the potentially important cognitive processes seen in social anxiety. Other processes highlighted in the models of social anxiety (Clark & Wells, Citation1995; Hofmann, Citation2007; Rapee & Heimberg, Citation1997), such as self‐focused attention, interpretation bias, safety behaviours and perceived threat in relation to the speech, should be included in future research to determine the relationships between perfectionism and these processes. In addition, objective measures of the speech task, along with measures of expected standards and perceived ability to meet standards in relation to the speech task, should be included in future research. Third, the current model was limited to a performance‐based situation only. Although public speaking is often viewed as one of the most anxiety‐provoking social tasks, evaluation of models using a range of other social tasks (e.g., interactional situations) is needed in order to gain a more general perspective. Fourth, an alternative measure of perfectionism is the Revised Almost Perfect Scale (APS‐R; Slaney, Rice, Mobley, Trippi, & Ashby, Citation2001). The APS‐R is often used to categorise people into adaptive and maladaptive perfectionists. Future research could include this measure to assess maladaptive perfectionism in social anxiety. Lastly, as state anxiety was only measured once (immediately following the speech task), there was no manipulation check to see whether the speech task actually induced anxiety in participants. This could potentially change the relationship between perfectionism, anxiety, and rumination.

Nevertheless, to our knowledge the current study is the first to investigate the role of perfectionism in a social situation such as a speech task. Our results (1) support the role of perfectionism in social anxiety as theoretically postulated by the cognitive‐behavioural models of social anxiety and (2) offer empirical support for the role of perfectionism in social anxiety and its cognitive processes in relation to a speech task. Based on the results of this study, perfectionism can potentially be considered as a possible predictor of social anxiety which in turn influences the anxiety symptoms and cognitive processes. Results of this study may enhance the existing literature by applying an integrative perspective of the role perfectionism plays in social anxiety and its cognitive processes. Although beyond the scope of our study, our findings may shed some light on prevention and treatment for social anxiety. In keeping with Hofmann's (Citation2007) model, if perfectionism serves as an important contributor to social anxiety, it is possible that targeting perfectionism may prevent or reduce social anxiety and its cognitive processes. Future studies will need to address the role of perfectionism in the prevention and treatment of social anxiety.

Notes

1. Given that literature has shown non‐causal relationships between social anxiety and perfectionism and Hofmann's model suggests a bi‐directional relationship between social anxiety and perfectionism, in addition to the hypothesised model, we also explored an alternative model implicating social anxiety as a contributor to perfectionism. Although the model fit from the SEM are identical, the PROCESS results show that the original hypothesised models were superior to that of the alternative models (SA → DAA → StA → PP → R = −.22, 95% CIs (−.51, −.08); SA → SPP → StA → PP → R = .05, 95% CIs (−.07, .24)). Further details of the supplementary analyses are available from the authors upon request.

References

- Abbott, M. J., & Rapee, R. M. (2004). Post‐event rumination and negative self‐appraisal in social phobia before and after treatment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113(1), 136–144. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0021‐843X.113.1.136

- Antony, M. M., Purdon, C. L., Huta, V., & Swinson, R. P. (1998). Dimensions of perfectionism across the anxiety disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36(12), 1143–1154. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005‐7967(98)00083‐7

- APA (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. American Psychiatric Association, text rev.

- Bieling, P. J., & Alden, L. E. (1997). The consequences of perfectionism for patients with social phobia. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 36(3), 387–395. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044‐8260.1997.tb01246.x

- Blankstein, K. R., & Lumley, C. H. (2008). Multidimensional perfectionism and ruminative brooding in current dysphoria, anxiety, worry, and anger. Journal of Rational‐Emotive and Cognitive‐Behavior Therapy, 26(3), 168–193. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942‐007‐0068‐z

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Brozovich, F., & Heimberg, R. G. (2008). An analysis of post‐event processing in social anxiety disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(6), 891–903. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2008.01.002

- Chen, J., Rapee, R. M., & Abbott, M. J. (2013). Mediators of the relationship between social anxiety and post‐event rumination. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27(1), 1–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.10.008

- Clark, D. M., & Wells, A. (1995). A cognitive model of social phobia. In R. G. Heimberg, M. R. Liebowitz, D. A. Hope, & F. R. Schneier (Eds.), Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment (pp. 69–93). New York: Guilford Press.

- Edwards, S. L., Rapee, R. M., & Franklin, J. (2003). Postevent rumination and recall bias for a social performance event in high and low socially anxious individuals. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27(6), 603–617. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026395526858

- Egan, S. J., Wade, T. D., & Shafran, R. (2011). Perfectionism as a transdiagnostic process: A clinical review. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(2), 203–212. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.009

- Frost, R. O., Marten, P., Lahart, C., & Rosenblate, R. (1990). The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14(5), 449–468. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01172967

- Frost, R. O., Glossner, K., & Maxner, S. (2010). Social anxiety disorder and its relationship to perfectionism. In S. G. Hofmann & P. M. Dibartolo (Eds.), Social anxiety: Clinical, developmental, and social perspectives (2nd ed., pp. 121–146). Oxford, UK: Elsevier.

- Hamachek, D. E. (1978). Psychodynamics of normal and neurotic perfectionism. Psychology: A Journal of Human Behavior, 15(1), 27–33.

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression‐based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

- Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (1991). Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: Conceptualisation, assessment, and association with psychopathology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(3), 456–470. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022‐3514.60.3.456

- Hewitt, P. L., Flett, G. L., & Ediger, E. (1996). Perfectionism and depression: Longitudinal assessment of a specific vulnerability hypothesis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 105(2), 276–280. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0021‐843X.105.2.276

- Hofmann, S. G. (2007). Cognitive factors that maintain social anxiety disorder: A comprehensive model and its treatment implications. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 36(4), 193–209. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/16506070701421313

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Juster, H. R., Heimberg, R. G., Frost, R. O., Holt, C. S., Mattia, J. I., & Faccenda, K. (1996). Social phobia and perfectionism. Personality and Individual Differences, 21(3), 403–410. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0191‐8869(96)00075‐X

- Kim, H. Y., Lundh, L. G., & Harvey, A. (2002). The enhancement of video feedback by cognitive preparation in the treatment of social anxiety. A single‐session experiment. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 33(1), 19–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005‐7916(02)00010‐1

- Leary, M. R. (1983). A brief version of the Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 9(3), 371–375. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167283093007

- Lo, A., & Abbott, M. J. (2013). The impact of manipulating expected standards of performance for adaptive, maladaptive, and non‐perfectionists. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 37(4), 762–778. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608‐013‐9528‐1

- Moscovitch, D. A., & Hofmann, S. G. (2007). When ambiguity hurts: Social standards moderate self‐appraisals in generalized social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(5), 1039–1052. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2006.07.008

- Randles, D., Flett, G. L., Nash, K. A., Mcgregor, I. D., & Hewitt, P. L. (2010). Dimensions of perfectionism, behavioral inhibition, and rumination. Personality and Individual Differences, 49(2), 83–87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.03.002

- Rapee, R. M., & Abbott, M. J. (2007). Modelling relationships between cognitive variables during and following public speaking in participants with social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(12), 2977–2989. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2007.08.008

- Rapee, R. M., & Heimberg, R. G. (1997). A cognitive‐behavioral model of anxiety in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35(8), 741–756. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005‐7967(97)00022‐3

- Rapee, R. M., & Lim, L. (1992). Discrepancy between self‐ and observer ratings of performance in social phobics. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101(4), 728–731. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0021‐843X.101.4.728

- Rodebaugh, T. L., Woods, C. M., Thissen, D. M., Heimberg, R. G., Chambless, D. L., & Rapee, R. M. (2004). More information from fewer questions: The factor structure and item properties of the original and Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale. Psychological Assessment, 16(2), 169–181. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/1040‐3590.16.2.169

- Schlenker, B. R., & Leary, M. R. (1982). Social anxiety and self‐presentation: A conceptualization model. Psychological Bulletin, 92(3), 641–669. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033‐2909.92.3.641

- Shafran, R., Cooper, Z., & Fairburn, C. G. (2002). Clinical perfectionism: A cognitive‐behavioural analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40(7), 773–791. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005‐7967(01)00059‐6

- Shumaker, E. A., & Rodebaugh, T. L. (2009). Perfectionism and social anxiety: Rethinking the role of high standards. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 40(3), 423–433. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2009.04.002

- Slaney, R. B., Rice, K. G., Mobley, M., Trippi, J., & Ashby, J. S. (2001). The revised Almost Perfect Scale. Measurement and Evaluation in counseling and Development, 34(3), 130–145.

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

- Wallace, S. T., & Alden, L. E. (1995). Social anxiety and standard setting following social success or failure. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 19(6), 613–631. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02227857

- Weeks, J. W., Heimberg, R. G., Fresco, D. M., Hart, T. A., Turk, C. L., Schneier, F. R., & Liebowitz, M. R. (2005). Empirical validation and psychometric evaluation of the Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale in patients with social anxiety disorder. Psychological Assessment, 17(2), 179–190. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/1040‐3590.17.2.179

- Wirtz, P. H., Elsenbruch, S., Emini, L., Rudisuli, K., Groessbauer, S., & Ehlert, U. (2007). Perfectionism and the cortisol response to psychosocial stress in men. Psychosomatic Medicine, 69(3), 249–255. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e318042589e