?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Objective

As negative repetitive thought forms, depressive rumination and worry have been most closely examined in the contexts of depression and anxiety, respectively. However, recent research suggests that rumination and worry are transdiagnostic processes that are similarly related to both disorders. As the higher rates of depression and anxiety in women are largely attributable to negative repetitive thought, it is important to examine how rumination and worry influence symptoms of these disorders within women across time. The present study first sought to evaluate the specificity of depressive rumination and worry in their correspondence to shared and unique symptoms of depression and anxiety. Second, we delineated the temporal relationships between affective symptoms and repetitive thoughts.

Method

In a study of 67 women, weekly ratings of general distress, anxious arousal, anhedonic depression, worry, and rumination were collected over 5 weeks.

Results

Analyses revealed that both rumination and worry were independently related to concurrent general distress (shared feature of depression and anxiety), but not anxious arousal or anhedonia (unique symptoms). Further, a positive feedback loop was observed involving depressive rumination—and its brooding component—predicting greater general distress the following week, and vice versa.

Conclusion

These findings indicate that depressive rumination and worry do not distinguish between depression and anxiety disorders, and that both forms of negative repetitive thoughts are related to shared features of depression and anxiety. However, given the cyclical relationship between rumination and distress symptoms, rumination may be a more corrosive cognitive process in women.

Disclosure statement: Dr. Kalmbach reports no conflict of interest. Dr. Pillai reports no conflict of interest. Dr. Ciesla reports no conflict of interest.

Introduction

Given the high prevalence rates of depression and anxiety in women (Kessler et al., Citation2003; Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, & Walters, Citation2005), elucidating the impact of negative repetitive thought (NRT) on symptoms of depression and anxiety over time within women is paramount. The insidious effects of NRT in the context of mood and anxiety disorders are well‐documented (Aldao, Nolen‐Hoeksema, & Schweizer, Citation2010; Borkovec, Citation1994; Nolen‐Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubomirsky, Citation2008; Watkins, Citation2008). Two forms of NRT have received considerable attention: depressive rumination and worry. Recent evidence suggests that rumination and worry are similar thought processes (Watkins, Citation2008) that differ in content (Watkins, Moulds, & Mackintosh, Citation2005). Although born out of the separate research traditions of anxiety and depression, worry and rumination have nevertheless been shown to be similarly related to both disorders (McEvoy, Watson, Watkins, & Nathan, Citation2013). However, the literature currently suffers from a dearth of investigations examining NRT as it relates to shared and disorder‐specific features of anxiety and depression. Given the significant comorbidity between depression and anxiety, elucidating how rumination and worry temporally relate to these shared and unique symptoms of depression and anxiety within people may offer insight into the cognitive processes complicit in these disorders. The present study was part of a larger effort focusing on women's health, and examined how changes in depressive rumination and worry corresponded to variations in week‐to‐week experiences of general distress (shared symptoms), anxious arousal (unique to anxiety) and anhedonia (unique to depression) using a 5‐week repeated‐measures design in a community sample of adult women.

A defining feature of generalised anxiety disorder (GAD), worry is a future‐focused form of NRT that involves problem solving, and preparing for and avoiding perceived threats (Borkovec & Roemer, Citation1995; Borkovec, Robinson, Pruzinsky, & DePree, Citation1983). The process of worrying has been associated with greater fear and apprehension, as well as somatic tension (Borkovec et al., Citation1983). Notably, women tend to engage in greater levels of worry than men (Stavosky & Borkovec, Citation1987). Although worry initially received attention as the key ingredient of GAD, high levels of worry have also been found in samples of individuals suffering from unipolar depression, social anxiety disorder, and panic disorder (McEvoy et al., Citation2013).

Depressive rumination, on the other hand, is a past‐focused form of NRT that involves perseverating on one's depressive symptoms, reflectively pondering one's feelings and emotions, and passively brooding on the causes of one's negative affect and current situation (Nolen‐Hoeksema, Citation1991; Nolen‐Hoeksema et al., Citation2008; Treynor, Gonzalez, & Nolen‐Hoeksema, Citation2003). Notably, although several forms of ‘rumination’ have been described in various literatures, including stress‐specific rumination (Roger & Najarian, Citation1989) and positive rumination (Feldman, Joormann, & Johnson, Citation2008), among many other forms, the present study exclusively focuses on depressive rumination, as it has naturally received much of the focus in the anxiety and depression literatures. Although the perceived functions of depressive rumination include gaining insight into one's feelings and problems (Nolen‐Hoeksema et al., Citation2008), rumination has been linked to the onset and maintenance of depressive episodes. Moreover, prior research has shown that women are more likely to ruminate than men, which has been posited to at least partially account for the gender difference in depression prevalence (Nolen‐Hoeksema et al., Citation2008).

Thus, given these similarities between rumination and worry, and the significant comorbidity between depression and anxiety, it is surprising how few studies have compared rumination and worry as they relate to the shared and unique features of anxiety and depression. Clark and Watson's (Citation1991) tripartite model describes anxiety and depression as sharing high negative affect, which they labelled general distress (e.g., sadness, fear). On the other hand, anhedonia, defined as blunted positive affect and diminished appetitive drive, is considered to be unique to depression. In turn, anxious arousal, defined as somatic hyperarousal (e.g., increased heart rate, muscle tension), is unique to anxiety.

One study that incorporated Clark and Watson's (Citation1991) tripartite model in the comparison of worry and rumination found that high worriers and high ruminators also reported greater concurrent general distress (Hong, Citation2007). Further, high worriers, but not high ruminators, experienced greater general distress, anxious arousal, and anhedonia 1 month later. However, this study did not examine the potential reciprocal effect of mood on subsequent NRT. Additionally, the study examined inter‐individual differences, which offer insight into trait characteristics. That is, the study indicated that individuals who endorsed greater trait levels of NRT experienced greater mood symptoms later on compared with low trait perseverators. The impact of within‐person changes in levels of perseverating on worrisome or ruminative thoughts on affective symptoms was not explored. In other words, rather than comparing high versus low perseverators, it is important to investigate what happens when someone worries versus when that same person ruminates, irrespective of his/her general tendencies to engage in NRT. By examining this intra‐individual change, which allows for the examination of state‐level relations, we are afforded a better understanding of how depressed or anxious mood and NRT relate over time, irrespective of trait characteristics.

The present investigation sought to describe the concurrent and temporal relationships among worry and depressive rumination and symptoms of anxiety and depression. By doing so, we were able to test whether anxiety uniquely corresponded to worry and depression independently related to depressive rumination (i.e., each form of NRT is disorder‐specific), or if shared symptoms between the two disorders were associated with both thought processes (i.e., both forms of NRT are transdiagnostic). To accomplish this goal, we collected prospective data from a community sample of adult women who reported weekly experiences of depressive rumination, worry, general distress (shared symptoms), anhedonia (depression‐specific), and anxious arousal (anxiety‐specific). By assessing affective symptoms and NRT weekly, we aimed to maximise ecological validity and capture fluctuations in mood and repetitive thought while reducing the effects of recall bias. Additionally, this repeated‐measures design allows for the examination of both concurrent and temporal relations. Overall, we predicted that depressive rumination and worry would be associated with same‐week general distress (i.e., shared features of depression and anxiety) due to recent evidence that depressive rumination and worry are non‐specific to various mood and anxiety disorders and overall mental health (McEvoy et al., Citation2013; Watkins, Citation2008). Regarding temporal precedence, we predicted cyclical associations such that rumination and worry would act as determinants and consequences of weekly general distress. Because evidence has demonstrated the transdiagnostic characteristics of depressive rumination and worry, we predicted that these thought processes would only be significantly associated with the shared symptoms between the two disorders (i.e., general distress), whereas they would not be independently related to either anxious arousal or anhedonia.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from the community using advertisements in local newspapers, public buildings, mental health clinics, and online. The present study was part of a larger ongoing study of women's health, funded by an institutional grant. Participants were required to meet the following inclusion criteriaFootnote1: (1) female, (2) ages between 25 and 45 years, (3) no history of diabetes or heart disease, and (4) free of antidepressants for at least the previous month. Participants provided written informed consent prior to participation and were financially compensated for each completed assessment. This protocol was approved by the local institutional review board. Sixty‐seven women (age 30 ± 6) participated in the current study. The sample largely identified as Caucasian (86.6 %), although some ethnic diversity was observed (6% African‐American, 4.5% Latino or Hispanic, 1.5% Eastern Asian or Pacific Islander, and 1.5% ‘Other’).

Procedure

Participants were asked to report NRT and anxiety and depression symptoms on the same day each week for the 5‐week duration of the study. Because assessments were weekly, questionnaires were modified to assess experiences over the past 7 days. For the first assessment, participants met with researchers in a laboratory and were given instructions for participation. The next three assessments were web‐delivered to the participants' email addresses using Remark Web Survey 5.0 (Gravic, Inc., Malvern, PA, USA). Participants returned to the laboratory to complete the final assessment and to receive compensation. Analyses indicated that study compliance was high, as the mean number of assessments completed was 4.61 (SD = 1.00) and 60 participants (89.55%) completed four or more of the weekly questionnaires. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Measures

Depression and anxiety

The Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire—Short Form (MASQ; Watson, Clark, et al., Citation1995a; Watson, Weber, et al., Citation1995b) is a 62‐item self‐report measure of depression and anxiety. Three main factors assess the facets of the tripartite model: general distress (e.g., ‘felt uneasy’, ‘felt discouraged’), anxious arousal (e.g., ‘was short of breath’, ‘hands were shaky’), and anhedonia (e.g., ‘felt nothing was really enjoyable’). Internal consistencies ranged from adequate to high (see Table ). Higher scores on the MASQ indicate higher levels of depression and anxiety symptoms. This measure has been validated for use in non‐clinical samples (Watson, Clark, et al., Citation1995a) and has been shown to have good convergent and discriminant validity (Reidy & Keogh, Citation1997). See Table for descriptive correlations.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for general distress, anhedonia, anxious arousal, and NRT

Repetitive thought

The Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ; Meyer, Miller, Metzger, & Borkovec, Citation1990) is a 16‐item self‐report measure of the excessiveness (e.g., ‘I am always worrying about something’), pervasiveness (e.g., ‘many situations worry me’), and uncontrollability of worry (e.g., ‘I know I shouldn't worry, but I just can't help it’). Internal consistency was adequate (see Table ). Higher scores on the PSWQ indicate greater levels of worry. See Table for descriptive correlations.

The Ruminative Responses Scale (RRS; Nolen‐Hoeksema & Morrow, Citation1991; Treynor et al., Citation2003) is a 22‐item self‐report measure of ruminative thought. Although the measure is often used as a unitary construct, three subscales have been identified: focusing on depressive symptoms (e.g., ‘think about how sad you feel’), intropunitive brooding (e.g., ‘think “what am I doing to deserve this” ’), and reflective pondering about the causes of negative affect (e.g., ‘go someplace alone to think about your feelings’). Although the depressive symptom‐focused subscale is highly collinear with depression, the brooding and pondering subscales are less confounded. Internal consistencies ranged from adequate to very high (see Table ). See Table for descriptive correlations.

Data analysis plan

Analyses were conducted using hierarchical linear modelling (HLM, also known as multilevel modelling) to account for the time‐nested structure of the data. HLM allows for the examination of within‐person (i.e., level 1) changes. Further, this approach permits the examination of both covariance effects and lagged effects that may exist between these constructs, revealing any concurrent and temporal relations. Importantly, HLM is robust to the presence of missing data, which are common in longitudinal studies (Singer & Willett, Citation2003).

To examine covariance effects, each form of NRT was estimated using general distress, anhedonia, and anxious arousal from the same week (for person i, at time t). Notably, predictors were entered into the model simultaneously in order to allow for examination of unique relations with the outcome variables. An example of a covariance model is below.

Example 1:

These results revealed unique associations of general distress, anhedonia, and anxious arousal with various forms of NRT during the same week.

To examine temporal relations, we conducted lagged effects models. Each dependent variable (at time t) was estimated by predictor variables of the previous week (at time t−1). Notably, when regressing mood onto NRT, depressive rumination and worry were entered as predictors into a single model. This allowed for the testing of independent predictive qualities of depressive rumination and worry on mood. Although prior research has demonstrated worry and rumination to be highly correlated (e.g., Fresco, Frankel, Mennin, Turk, & Heimberg, Citation2002; Segerstrom, Tsao, Alden, & Craske, Citation2000), analysis revealed that the multicollinearity assumption of HLM was not violated as rumination and worry were correlated at r = .52. However, lagged measures of the outcome variables were not included in the HLM models as covariates due to high collinearity among the outcome variables and their lagged values,Footnote2 and the likelihood that lagged values would be highly related to random parts of the HLM model (Moberly & Watkins, Citation2008; Spencer, Citation2002), both of which violate model assumptions.

Results

Covariance models

Null models

First, we established that the outcome variables exhibited sufficient variance across time within participants to justify HLM analyses. An unconditional means model with weekly depressive rumination was regressed on an intercept, a level 1 residual (intra‐individual) and a level 2 residual (inter‐individual) (see Singer & Willett, Citation2003). Results indicated that approximately 43% of the total variance in depressive rumination was due to intra‐individual fluctuations. We then ran similar unconditional means models for weekly brooding and pondering, and found that 47% and 45% of the variance in brooding and ponder, respectively, were due to intra‐individual fluctuations. Next, we examined the proportions of inter‐ and intra‐individual variances in weekly worry and found that 40% of the variance was due to fluctuations within individuals. These results supported our use of HLM analyses for time‐varying outcomes.

Same‐week models

First, we tested whether worry and depressive rumination were related to same‐week experiences of shared and unique symptoms of depression and anxiety. As such, we then examined how weekly levels of general distress, anhedonia, and anxious arousal were related to same‐week levels of NRT (see Table ). We estimated depressive rumination as predicted by general distress, anhedonia, and anxious arousal. Analyses revealed that only general distress was uniquely related to same‐week depressive rumination, such that higher levels were associated with greater same‐week depressive rumination. Anhedonia and anxious arousal were non‐significant predictors. However, as the depression symptom‐focused items on the RRS posed a potential confound, we then estimated the brooding and pondering subscales using the same predictors. Consistently, we found that general distress was the only unique predictor of brooding and pondering. Overall, findings showed that higher levels of depressive rumination predicted shared symptoms between anxiety and depression, and that rumination was not related to depression‐specific nor anxiety‐specific symptoms.

Table 2. Same‐week relationships between NRT and symptoms of depression and anxiety

Next, we examined the concurrent relationships among general distress, anhedonia, and anxious arousal and worry. Similar to the results of the depressive rumination models, analyses revealed that general distress was uniquely related to same‐week levels of worry such that higher levels of worry were associated with greater same‐week shared symptoms of depression and anxiety. Notably, anhedonia and anxious arousal were not significant predictors. These findings were consistent with those of depressive rumination such that worry and depressive rumination were shown to be related to shared symptoms of anxiety and depression, but not independently associated with any symptoms that are unique to either disorder.

Although above results demonstrated that rumination and worry were both related to same‐week levels of general distress, it remained unclear if the relationship between depressive rumination and general distress was unique from the relationship between worry and general distress, or if these two relationships were redundant. In order to test the independence of these relationships, the associations of worry and rumination with general distress needed to be compared. As such, we regressed general distress onto same‐week rumination and worry in the same model. Analyses revealed that rumination and worry were both independently predictive of general distress (see Table ). In other words, although depressive rumination and worry are both related to the shared symptoms between anxiety and depression, the contributions of worry and depressive rumination to general distress are independent of one another.

Lagged models

Regressing NRT onto prior week's mood

Next, we tested whether symptoms of depression and anxiety predicted worry and rumination a week later. Specifically, we examined how weekly levels of general distress, anhedonia, and anxious arousal were related to the following week's levels of NRT (see Table ). First, we estimated depressive rumination as predicted by the prior week's mood symptoms. Analyses revealed that only general distress was a unique predictor of later rumination such that higher levels of distress predicted greater rumination the following week, whereas anhedonia and anxious arousal were non‐significant. We then estimated the brooding and pondering subscales using the same prior week predictors. Consistently, we found that general distress was the only unique predictor of the following week's levels of brooding and pondering. Next, we examined the predictive qualities of general distress, anhedonia, and anxious arousal on the following week's levels of worry. In contrast to the results of the rumination models, analyses revealed that worry was not predicted by the previous week's levels of general distress, anxious arousal, or anhedonia.

Table 3. Depression and anxiety symptoms predicting next‐week rumination and worry

Regressing mood onto prior week's negative repetitive thinking

After exploring how affective symptoms predict later levels of NRT, we then tested prospective relationships in the opposite direction. That is, we tested whether worry and depressive rumination significantly predicted symptom levels of depression and anxiety the following week. To examine NRT's predictive abilities of later mood, each mood state was estimated twice. In the first model, we regressed mood (e.g., general distress at time t) onto the previous week's rumination and worry (time t−1) while controlling for same week's other mood states (e.g., anxious arousal and anhedonia at time t). In the second model, for the purpose of accounting for the potential confound of the depression symptom‐focused items in the RRS, we replaced depressive rumination with its brooding and pondering components and reran the model as described. Because each mood state was estimated twice in this set of analyses, we used a Bonferroni‐adjusted alpha of p = .025.

First, we regressed general distress onto the prior week's depressive rumination and worry while controlling for concurrent anhedonia and anxious arousal (see Table ). Analyses revealed that rumination predicted the following week's levels of general distress such that higher levels of rumination predicted greater shared symptoms of anxiety and depression the following week. Contrary to our predictions, worry was not predictive of next‐week levels of mood symptoms. We then ran an additional model regressing general distress onto brooding, pondering, and worry. Analyses revealed that brooding predicted next‐week general distress such that higher levels of brooding predicted greater distress the following week. Pondering and worry were non‐significant predictors. Taking the lagged results together, the relationship between depressive rumination and general distress was reciprocal. That is, depressive rumination led to greater distress later on, which in turn increased levels of depressive rumination. In contrast, worry did not share temporal relationships with general distress.

Table 4. Rumination and worry predicting next‐week symptoms of depression and anxiety

Next, we regressed anxious arousal onto the prior week's depressive rumination and worry while controlling for concurrent general distress and anhedonia (see Table ). Analyses revealed that depressive rumination predicted greater anxious arousal a week later. Worry was not a significant predictor. We then regressed anxious arousal onto the previous week's brooding, pondering, and worry. In this model, NRT did not predict anxious arousal. As such, it was interpreted that the depression symptom‐focused items in the RRS accounted for the previous model, indicating that rumination was predictive of greater anxious arousal the following week.

Lastly, we regressed anhedonia onto the previous week's depressive rumination and worry while controlling for concurrent general distress and anxious arousal (see Table ). In this model, neither depressive rumination nor worry predicted the following week's anhedonia. We then regressed anhedonia onto the previous week's brooding, pondering, and worry. Consistently, we found that brooding, pondering, and worry were not predictive of anhedonia a week later.

Discussion

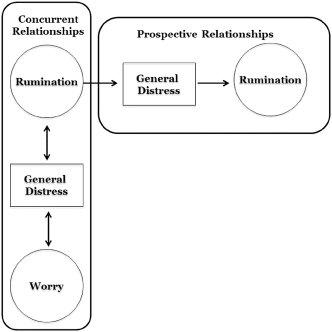

The present study followed adult women for 5 weeks to examine how changes in ruminative and worrisome thought processes correspond to week‐to‐week variations in shared and disorder‐specific symptoms of depression and anxiety. Consistent with a growing body of research, we found evidence in support of depressive rumination and worry as transdiagnostic processes (see Fig. 1). Specifically, both worry and rumination were independently related to same‐week experiences of general distress (i.e., shared features of depression and anxiety). Notably, neither form of NRT was related to the unique aspects of either depression (i.e., anhedonia) or anxiety (i.e., anxious arousal). Importantly, we examined temporal relations between state‐level NRT and depressive and anxious mood. Analyses revealed a cyclical pattern between depressive rumination and general distress such that rumination predicted greater general distress the following week and vice versa.

Figure 1. Model depicting both concurrent and prospective relationships between negative repetitive thought processes and overlapping symptoms between anxiety and depression.

Overall, we found both state levels of rumination and worry to be independently related to the same aspects of depression and anxiety in a community sample of women. To illustrate, when a women either worries or ruminates, she will experience greater concurrent sadness, fear, irritability, and poorer self‐worth (i.e., features of both depression and anxiety). Furthermore, she will also experience greater levels of distress later on, just as elevated levels of distress will then lead to greater rumination. Worry, on the other hand, did not exhibit weekly temporal relations with mood in the present study. These results suggest that rumination may be a more corrosive state‐level thought process than worry for women. Moreover, these findings were replicated when excluding depression symptom‐focused aspects of depressive rumination. Specifically, intropunitively brooding on the causes of one's negative mood and current situation is related to greater concurrent distress. Notably, as women brood, their distress is prolonged, which in turn causes them to continue to brood, acting as a positive feedback loop. In comparison, reflectively pondering on one's feelings and emotions was related to concurrent distress and was predicted by the prior week's distress. That is, if an individual feels distressed, she may respond by pondering on her feelings. However, pondering was not predictive of future mood or anxiety symptoms, which may suggest that this component of depressive rumination may not prolong psychological suffering. This finding that the brooding component of rumination is more harmful than reflective pondering, and that it is related to both depression and anxiety, is consistent with prior research (Joormann, Dkane, & Gotlib, Citation2006; McEvoy et al., Citation2013; Nolen‐Hoeksema et al., Citation2008).

Although we believe the present study adds to the literature on depression, anxiety, and NRT, our findings must be interpreted in the context of certain limitations. One such consideration regards generalisability. Our sample was recruited from the community and solely comprised women aged between 25 and 45. Additionally, baseline assessments of depression and anxiety that would allow for diagnostic impressions were not administered. Future studies may benefit from examining these intra‐individual relations while controlling for higher order depression and anxiety. Notably, we know of no research indicating that diagnostic status moderates the relation between NRT and depression or anxiety, but it is important to investigate if one's current severity of depression or anxiety moderates the strength of the relations between state‐level affective symptoms and NRT. Additionally, given the gender differences in both NRT and affective disorders, it is important to study these relations in men. Second, the week‐long duration of assessments may not have been sensitive enough to capture more transient fluctuations in affect and NRT. Although the present study did not demonstrate temporal relations between distress and worry, the case may be that worry's impact on later mood (or vice versa) may be more proximal than a week.

Despite these limitations, we believe the present study adds to the current literature on depression, anxiety, and NRT. Although prior research has demonstrated that depressive rumination and worry are transdiagnostic processes (McEvoy et al., Citation2013; Nolen‐Hoeksema et al., Citation2008; Watkins, Citation2008), this study is the first, to our knowledge, to examine state‐level relations of rumination and worry in their relation to depression and anxiety using Clark and Watson's (Citation1991) conceptualisation. Notably, our findings indicated that although depressive rumination and worry may be similar thought processes, they are unique in that they are both independently related to general distress. Further, these findings may offer insight into the comorbidity between mood and anxiety disorders in adult women. Not only are both thought processes highly correlated, but they are similarly related to fear, sadness, self‐worth, and pessimism, which are common features of both depressed and anxious mood. These results highlight the clinical importance of tending to and defusing both ruminative and worrisome thoughts in patients, whether the primary diagnosis is a form of unipolar depression or anxiety disorder. Importantly, our findings suggest that depressive rumination, especially its brooding component, may be the most detrimental form of NRT, given the positive feedback loop it shares with anxiety and depression symptoms. This suggests that elevated state levels of depressive rumination and brooding may be key ingredients in the evolution of distressed affect into more clinical states of anxiety or depression. Of note, brooding differs in content from other forms of perseverative thought, and as mentioned in the introduction many forms of ruminative thought exist and are described in various literatures. Thus, exploring potential concurrent and temporal relationships between affect states and other forms of negatively and positively valenced, global versus concrete (see Stöber & Borkovec, Citation2002) ruminative thought processes may enrich our conceptualisation of the manner in which perseverative thought processes may contribute to or protect against depression and anxiety.

Notes

Disclosure statement: Dr. Kalmbach reports no conflict of interest. Dr. Pillai reports no conflict of interest. Dr. Ciesla reports no conflict of interest.

1. Inclusion criteria were intended to reduce the prevalence medical comorbidities and iatrogenic effects of antidepressants, as to minimise potential confounds within the sample.

2. Correlations between outcome variables at time t and time t−1 indicated high collinearity (general distress r = .72; RRS r = .74; PSWQ r = .74).

References

- Aldao, A., Nolen‐hoeksema, S., & Schweizer, S. (2010). Emotion‐regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta‐analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 217–237.

- Borkovec, T. D. (1994). The nature, functions, and origins of worry. In G. C. L. Davey & F. Tallis (Eds.), Worrying: Perspectives on theory, assessment, and treatment (pp. 5–33). Oxford: John Wiley & Sons.

- Borkovec, T. D., Robinson, E., Pruzinsky, T., & Depree, J. A. (1983). Preliminary exploration of worry: Some characteristics and processes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 21(1), 9–16.

- Borkovec, T. D., & Roemer, L. (1995). Perceived functions of worry among generalized anxiety disorder subjects: Distraction from more emotionally distressing topics? Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 26(1), 25–30.

- Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1991). Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(3), 316–336.

- Feldman, G. C., Joormann, J., & Johnson, S. L. (2008). Responses to positive affect: A self‐report measure of rumination and dampening. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 32(4), 507–525.

- Fresco, D. M., Frankel, A. N., Mennin, D. S., Turk, C. L., & Heimberg, R. G. (2002). Distinct and overlapping features of rumination and worry: The relationship of cognitive production to negative affective states. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 26(2), 179–188.

- Hong, R. Y. (2007). Worry and rumination: Differential associations with anxious and depressive symptoms and coping behavior. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(2), 277–290.

- Joormann, J., Dkane, M., & Gotlib, I. H. (2006). Adaptive and maladaptive components of rumination? Diagnostic specificity and relation to depressive biases. Behavior Therapy, 37(3), 269–280.

- Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Koretz, D., Merikangas, K. R., … Wang, P. S. (2003). The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS‐R). Journal of the American Medical Association, 289(23), 3095–3105.

- Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P. A., Demler, O., Jin, R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age‐of‐onset distributions of DSM‐IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS‐R). Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 593–602.

- Mcevoy, P. M., Watson, H., Watkins, E. R., & Nathan, P. (2013). The relationship between worry, rumination, and comorbidity: Evidence for repetitive negative thinking as a transdiagnostic construct. Journal of Affective Disorders, 151(1), 313–320.

- Meyer, T. J., Miller, M. L., Metzger, R. L., & Borkovec, T. D. (1990). Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 28(6), 487–495.

- Moberly, N. J., & Watkins, E. R. (2008). Ruminative self‐focus and negative affect: An experience sampling study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117(2), 314–323.

- Nolen‐hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(4), 569–582.

- Nolen‐hoeksema, S., & Morrow, J. (1991). A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(1), 115–121.

- Nolen‐hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 400–424.

- Reidy, J., & Keogh, E. (1997). Testing the discriminant and convergent validity of the Mood and Anxiety Symptoms Questionnaire using a British sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 23, 337–344.

- Roger, D., & Najarian, B. (1989). The construction and validation of a new scale for measuring emotion control. Personality and Individual Differences, 10(8), 845–853.

- Segerstrom, S. C., Tsao, J. C., Alden, L. E., & Craske, M. G. (2000). Worry and rumination: Repetitive thought as a concomitant and predictor of negative mood. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 24(6), 671–688.

- Singer, J. D., & Willett, J. B. (2003). Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Spencer, N. H. (2002). Combining modelling strategies to analyse teaching styles data. Quality and Quantity, 36(2), 113–127.

- Stavosky, J. M., & Borkovec, T. D. (1987). The phenomenon of worry: Theory, research, treatment and its implications for women. Women & Therapy, 6(3), 77–95.

- Stöber, J., & Borkovec, T. D. (2002). Reduced concreteness of worry in generalized anxiety disorder: Findings from a therapy study. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 26(1), 89–96.

- Treynor, W., Gonzalez, R., & Nolen‐hoeksema, S. (2003). Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27(3), 247–259.

- Watkins, E., Moulds, M., & Mackintosh, B. (2005). Comparisons between rumination and worry in a non‐clinical population. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43(12), 1577–1585.

- Watkins, E. R. (2008). Constructive and unconstructive repetitive thought. Psychological Bulletin, 134(2), 163–206.

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., Weber, K., Assenheimer, J. S., Strauss, M. E., & Mccormick, R. A. (1995a). Testing a tripartite model: II. Exploring the symptom structure of anxiety and depression in student, adult, and patient samples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104, 15–25.

- Watson, D., Weber, K., Assenheimer, J. S., Clark, L. A., Strauss, M. E., & Mccormick, R. A. (1995b). Testing a tripartite model: I. Evaluating the convergent and discriminant validity of anxiety and depression symptom scales. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104, 3–14.