Abstract

Objective

Healthy sleep is an important factor in predicting longevity, physical health, as well as cognitive functioning. This study examined the psychosocial factors contributing to healthy sleep intention and practice in college students, under the framework of the theory of planned behaviour.

Method

This study used a convenience sampling at a public university in Macao, China, where students voluntarily filled out questionnaires. Data were obtained from 362 college students, aged 18–25 years, with no serious sleep or emotional disturbances. Path analysis was used to investigate whether the data collected from the sample fit an extended model of the theory of planned behaviour including two additional variables, namely parental nurturance and perceived invulnerability.

Results

Self‐reported healthy sleep patterns were positively associated with behavioural intention and perceived behavioural control. As hypothesised, positive direct effects of attitude, descriptive norm, injunctive norm, and perceived behavioural control on intention were also observed. The resultant path model suggested that parental nurturance and perceived invulnerability exerted direct effects only on attitude, norms, and perceived behavioural control.

Conclusion

The results of our path analysis generally supported the application of the theory of planned behaviour to understanding healthy sleep among college students. University‐based health campaigns, which modify attitude, descriptive norm, injunctive norm, and perceived behavioural control, should be effective for promoting their intention and practice of healthy sleep.

Healthy sleep predicts longevity (Dement & Vaughan, Citation1999) as it can maintain the circadian rhythm (Giannotti, Cortesi, Sebastiani, & Ottaviano, Citation2002) and improve the immune system and cognitive functioning (Reis et al., Citation2011). It can be defined as a regular wake–sleep pattern with sufficient length. Young people are generally recommended to have 7–9-hr of continuous sleep per night (Barber & Munz, Citation2001; Louzada, da Silva, Peixoto, & Menna‐Barreto, Citation2008) so as to recover from daily physical and mental exertions and maximise functioning of the following day. Healthy sleep can also reduce excessive daytime sleepiness (Giannotti et al., Citation2002) and specifically optimise working memory performance and capacity for learning (Gradisar, Terrill, Johnston, & Douglas, Citation2008). Despite the benefits of healthy sleep, maintaining healthy sleep patterns has always been challenging to college students, who as emerging adults are facing unique demands, stressors, and changes (Galambos, Dalton, & Maggs, Citation2009). Unhealthy sleep patterns are prevalent among young people in both the West (Buboltz et al., Citation2009; Giannotti et al., Citation2002) and the East (Huang, Wang, & Guilleminault, Citation2010; Tsui & Wing, Citation2009). This study aims to examine the psychosocial influences on healthy sleep intention and patterns of college students based on the theory of planned behaviour (TPB; Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation2010).

Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB)

TPB is one of the most successful models in explaining and predicting health behaviours (Armitage & Conner, Citation2001; Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation2010). It has been used to explain and predict Australian undergraduate students' sleep hygiene behaviours (e.g., making a bedroom restful and ensuring no pre‐bedtime stress‐provoking activities) within a week (Kor & Mullan, Citation2011) and whether American college students had sufficient sleep on the previous night of a survey (Knowlden, Sharma, & Bernard, Citation2012). The model presumes that a volitional behaviour, such as engaging in healthy sleep patterns, is best predicted by one's behavioural intention. Behavioural intention indicates how much effort a person is willing to spend on accomplishing a given behaviour. According to TPB, behavioural intention is determined by one's attitude (i.e., the evaluation of the favourability of the behavioural outcome), perceived norms (i.e., the perceived social pressure on engaging in a behaviour or not), and perceived behaviour control (PBC; i.e., the perceived capability to perform a specific behaviour). Perceived norms can be further divided into two components: (a) injunctive norms, which refer to individuals' perceptions of what significant others would want of them regarding their engagement in the target behaviour, and (b) descriptive norms, which refer to perceptions regarding whether significant others have performed the target behaviour or not. In addition, TPB proposes that PBC has a direct effect on the actual target behaviour.

Previous findings have generally supported the efficacy of TPB in explaining college students' sleep behaviours, but the proportion of variance on the target sleep behaviour has varied widely, from 7% to 35% (Knowlden et al., Citation2012; Kor & Mullan, Citation2011). Those target sleep behaviours were set with a short time frame (from previous night to 1 week). Moreover, the past studies only tested the effect of injunctive, but not descriptive, norms. The explanatory value of attitude was also not consistently observed (Kor & Mullan, Citation2011). Therefore, this study tested an extended model of TPB including attitudes, injunctive and descriptive norms, PBC, behavioural intention, and two additional psychosocial factors (parental nurturance and perceived invulnerability) to identify the psychosocial factors of healthy sleep intention and patterns with a longer‐term time frame (i.e., 1 month) among college students.

Parental Nurturance and Perceived Invulnerability

Emerging adulthood is a crucial transitional stage from late adolescence to adulthood (Hernandez, Ramirez Garcia, & Flynn, Citation2010). Despite striving for autonomy, emerging adults are still under strong parental influence due to familism and social‐oriented motivation (Tao & Hong, Citation2014). Parental nurturance and support was generally found a protective factor against unhealthy behaviours (e.g., Needham & Austin, Citation2010; Wood, Read, Mitchell, & Brand, Citation2004). On the other hand, perceived invulnerability was reported as a risk factor (e.g., Greene, Krcmar, Walters, Rubin, & Hale, Citation2000; Millstein & Halpern‐Felsher, Citation2002); it is also a common cognitive characteristic of emerging adults (Millstein & Halpern‐Felsher, Citation2002). Impacts of parental nurturance and perceived invulnerability on healthy sleep, however, have not yet been tested.

Parental nurturance

The parental influence plays a significant role in affecting health and health behaviour of not only adolescents, but also emerging adults (Needham & Austin, Citation2010; Patock‐Peckham & Morgan‐Lopez, Citation2009). In the domain of health behaviours, parents promote children's desirable behaviours by not only monitoring them, but also providing them care and acceptance (Wood et al., Citation2004). Sense of parental nurturance and support was negatively associated with health‐risk behaviour among emerging adults, such as substance abuse (Needham & Austin, Citation2010). Young people with better familial relationships were also more likely to report sufficient sleep (Mueller, Bridges, & Goddard, Citation2011). Therefore, parental nurturance may be a potential protective factor, and it is hypothesised to be positively correlated with healthy sleep intention and patterns of college students. Moreover, it is plausible that when young people perceive their parents as more nurturing, they are more likely to be influenced by their views and habits of sleep (usually healthier), and perceive stronger norms for healthy sleep patterns. In the extended model of TPB, we hypothesise that parental nurturance have a direct positive effect on injunctive and descriptive norms of healthy sleep patterns among college students.

Perceived invulnerability

Perceived invulnerability is the perception bias that one has a relatively lower vulnerability to dangerous and negative events than others (Greene, Rubin, & Hale, Citation1995). People in emerging adulthood are inclined to perceiving illusion of invulnerability and misjudging the risk of unhealthy behaviour (Millstein & Halpern‐Felsher, Citation2002). Perceived invulnerability is thus considered to be a potential risk factor, and we expect that it negatively correlated with healthy sleep intention and patterns in the present study. A study of the applicability of TPB on drinking and driving among young adults showed a direct effect of perceived invulnerability on risk‐taking attitudes (Chan, Wu, & Hung, Citation2010). Therefore, we also speculate that perceived invulnerability may similarly lead young adults to underrate the positive consequences and importance of regular and sufficient sleep, and thus propose a direct negative effect of perceived invulnerability on attitude towards healthy sleep patterns in the extended model of TPB.

The Present Study

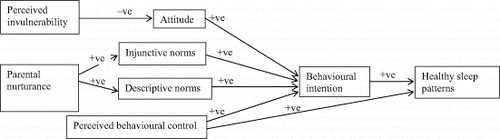

In this study, we generally hypothesise that both behavioural intention and self‐reported sleep patterns of college students are correlated positively with attitude, injunctive and descriptive norms, PBC, and parental nurturance, but negatively with perceived invulnerability. Fig. 1 also illustrates the extended model of TPB we proposed, which specifically outlines the hypothesised paths of influence among these factors. These hypotheses were tested in a sample of college students using both correlational and path analyses in this study. Under the framework of TPB, the findings provide a better understanding of the direct and indirect influences of psychosocial factors on healthy sleep intention and patterns, and facilitate the design of effective education campaigns for college students.

Method

Participants and procedure

Potential respondents, aged 18–25 years, were recruited via the subject pool (in which the students who had enrolled in introductory psychology courses voluntarily registered as potential research participants) or in different public areas of campus (such as libraries, dormitories, and classrooms) of a major public university in Macao, China, in January 2012, after obtaining ethics approval from the concerned psychology department. In total, we distributed a self‐administered, anonymous, structured questionnaire to 550 college students who had given their consent of participation.

A total of 485 respondents returned their questionnaires, with a response rate of 88%; 44 cases were considered invalid because of incomplete questionnaires (over 10% of questionnaires missing), essential information (such as age or sleep duration) missing, or an age of over 25 years. Moreover, to unveil the relationship between the TPB constructs and volitional sleep habit, we also screened out those respondents who were experiencing sleep disorders or severe emotional distress, which may jeopardise their healthy sleep (Talbot et al., Citation2012; Zee & Turek, Citation2006). Based on the scores on the subscales of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI; Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman, & Kupfer, Citation1989; Tsai et al., Citation2005) and the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS21; Lovibond & Lovibond, Citation1995), 40 and 52 respondents suffering from problematic sleep or emotional disturbance, respectively, were excluded from the data analyses.

The resultant sample was composed of 362 respondents, with 156 male (43.1%) and 206 female students (56.9%), with a mean age of 20.39 years (SD = 1.76). There were 120 (33%) first‐year undergraduates, 102 (28%) second‐year undergraduates, 50 (14%) third‐year undergraduates, 48 (13%) fourth‐year undergraduates, and 42 (12%) postgraduates. According to the official data, the current sample is representative of the college student population in Macao, in which 80% of the population are 24 year olds or below, with 43.4% being male and 56.6% being female (Statistics and Census Service [DSEC, Citation2013).

Measures

The questionnaire was composed of the measurement scales and items of the variables stated below. Respondents were also asked to provide demographics information (gender, age, and year of study). The comprehensiveness of the questionnaire was examined with a pilot study among 13 college students.

Healthy sleep patterns

Three items were extracted from the Chinese version of PSQI (Buysse et al., Citation1989; Tsai et al., Citation2005) to measure respondents' sleep habit. The respondents were asked to report their usual sleep duration and bedtime in the month prior to the interview. The first item was ‘During the last month, how many hours of sleep did you have at night?’ and scored as follows: 7–9-hr = 2, shorter or longer than 7–9-hr = 1. The second item was ‘During the last month, when did you go to bed at night?’ and scored as follows: before 11.00pm = 3, between 11.00pm to 1.00am = 2, between 1.00am to 3.00am = 1, and after 3.0am = 0. Finally, the third item was ‘During the last month, when did you wake up in the morning?’ and scored as follows: From 7.00am to 9.00am = 2, within 2-hr before 7.00am/after 9.00am = 1, after 11.00am = 0. These three items were positively correlated with one another (rs = .18–.33) and their internal consistency was .49. The sum of these three items scores gave a general index of healthy sleep patterns and a higher index indicated a healthier sleep pattern.

TPB components

Based on Fishbein and Ajzen's (Citation2010) guideline of construction of the TPB questionnaire, a healthy sleep pattern was clearly defined as regular and sufficient sleep for multiple days per week in a month in the questionnaire. The items of the TPB scales were adopted from those used by Knowlden et al. (Citation2012). Each TPB construct, except attitudes, was measured by multiple items with 7‐point Likert scale, ranging from 1 ‘strongly disagree’ to 7 ‘strongly agree’. A higher mean score of the corresponding scale represented a higher intention, stronger supportive norm, or higher PBC.

Behavioural intention to sleep healthily was assessed by three items, and a sample item was: ‘In the future month, I plan to practice healthy sleep’. PBC was assessed by four items, such as: ‘It is up to me whether or not I practice healthy sleep’. The reliabilities of the intention scale and the PBC scale were .90 and .80, respectively.

Injunctive norm was measured by four items that asked respondents to rate perceptions regarding significant others' views about their sleep patterns. A sample item was: ‘My friends want me to have healthy sleep patterns’. Descriptive norm was measured by three items regarding the degree to which respondents perceived their significant others having healthy sleep patterns. A sample item was: ‘My parents sleep healthily’. The reliabilities of these two scales were .80 and .72, respectively.

Six 7‐point semantic differential scale items describing healthy sleep patterns with adjective end points, namely, ‘bad (1) to good (7)’, ‘unhealthy (1) to healthy (7)’, ‘not refreshing (1) to refreshing (7)’, ‘unnecessary (1) to necessary (7)’, ‘not enjoyable (1) to enjoyable (7)’, and ‘detrimental to my social life (1) to beneficial to my social life (7)’, were used to measure attitude towards healthy sleep patterns. A sample item was: ‘To me, having healthy sleep night would be: bad (1) to good (7)’. Higher mean scores indicated more favourable attitudes towards healthy sleep. The reliability of the scale was .88.

Parental nurturance

The 24‐item Parental Nurturance Scale (Hopkins & Klein, Citation1993) was used to assess respondent's parental nurturance with a 5‐point Likert scale of 1 ‘strongly disagree’ to 5 ‘strongly agree’. A higher mean score represented a higher parental nurturance. A sample item was: ‘My parents expressed their warmth and affection for me’. The high reliability of the scale (α = .94) was confirmed in this study.

Perceived invulnerability

Respondents' perceptions of invulnerability to dangers and negative events, such as accidents and illnesses, were assessed by the 12‐item subscale of invulnerability to danger from the Adolescent Invulnerability Scale (Duggan, Lapsley, & Norman, Citation2000), with a 7‐point Likert scale of 1 ‘strongly disagree’ to 7 ‘strongly agree’. A higher mean score represented a higher perceived invulnerability. A sample item was: ‘I'm unlikely to be injured in an accident’. The reliability of the scale was .86 in this study.

Sleep and emotional disturbance

The subscales of sleep latency and sleep disturbance in PSQI (Buysse et al., Citation1989; Tsai et al., Citation2005) and the three subscales of depression, anxiety, and stress in DASS21 (Lovibond & Lovibond, Citation1995) were used in this study as exclusion criteria assessment for respondents. It was because problematic sleep or emotional disturbances might make healthy sleep behaviours undesirably less volitional. The two subscales of PSQI were measured on a 4‐point frequency scale (from 0 ‘never’ to 3 ‘three times or more per week’), whereas those of DASS21 was used with another 4‐point scale (from 0 ‘not at all’ to 3 ‘most of the time’). Higher total scores of these scales reflected higher levels of sleep problems or negative emotions. Respondents who reported moderate to severe sleep disturbance (i.e., the composite subscale score of PSQI > 12; Buysse et al., Citation1989) or emotional disturbance (i.e., depression subscale score > 15, anxiety subscale score > 11, or stress subscale score > 19; Lovibond & Lovibond, Citation1995) were excluded from further analyses.

Results

Preliminary analysis

We used IBM SPSS19 (IBM, New York, NY, USA) to clean and analyse the current dataset. Of the respondents, 60% reported 7–9-hr of sleep, 53% woke up early (7.00am–9.00am), and 40% went to bed before 1.00am. There was no significant effect of gender, age, and year of study on healthy sleep patterns or intention (p > .05). These factors were not controlled in the subsequent multivariate analyses. The descriptive statistics of the psychosocial variables and their correlation coefficients are reported in Table .

Table 1. Means, standard deviations (SDs), and correlations among the concerned variables

Healthy sleep patterns were positively associated with behavioural intention, attitude, injunctive norm, PBC, and parental nurturance. They were also associated with descriptive norms and perceived invulnerability in the hypothesised positive directions, but the correlation magnitude did not reach the statistically significance level. Behavioural intention was significantly correlated with all other psychosocial factors, except perceived invulnerability. As expected, parental nurturance was positively associated with injunctive and descriptive norms, whereas perceived invulnerability was negatively correlated with attitude significantly.

Path analysis

Path analyses using maximum likelihood method were conducted with IBM SPSS Amos 19 to test how well the extended model of TPB (Fig. 1) fit the data collected from the sample. The model fit was regarded as acceptable when the goodness of fit index (GFI) was greater than .95 (Hooper, Coughlan, & Mullen, Citation2008), the comparative-fit index (CFI) was greater than .90 (Bentler, Citation1992), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was less than .08 (Browne & Cudeck, Citation1993), and the standardised mean square residual (SRMR) was less than .08 (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). The statistical significance of each path in the proposed model was also tested.

All the hypothesised paths were significant (ps < .01), but the proposed model did not adequately fit with the current dataset, with χ2 = 242.072, df = 23, p < .001, GFI = .86, CFI = .63, RMSEA = .16, SRMR = .14. Therefore, the modification indices, which suggest plausible paths among the existing variables based on the statistical comparison of various models, were checked to explore how the goodness‐of‐fit of the proposed model to the data could be improved.

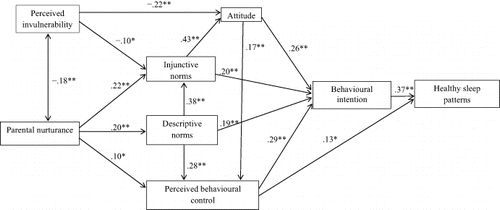

Six additional paths suggested by the modification indices were added into the proposed model. These paths included (1) one from perceived invulnerability to injunctive norm, (2) from parental nurturance to PBC, (3) from descriptive norm to injunctive norm, (4) from descriptive norm to PBC, (5) from injunctive norm to attitude, and (6) from attitude to PBC. Moreover, parental nurturance and perceived invulnerability were allowed to be correlated. Having added these paths, the resultant model, with standardised coefficients, is shown in Fig. 2. Its goodness‐of‐fit was satisfactory, with χ2 = 29.71, df = 12, p = .003, GFI = .98, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .06, and SRMR = .04.

Figure 2. The finalised path model result summary with standardised coefficients: *p < .05; **p < .01.

According to the resultant model, 19% of the variance in healthy sleep patterns was explained by behavioural intention and PBC. PBC, attitude, injunctive norm, and descriptive norm explained 43% of the variance in intention. The standardised indirect effects of these four TPB components on healthy sleep patterns were .11, .14, .13, and .19, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) [.06, .17], [.08, .19], [.08, .19], and [.14, .24], respectively. Perceived invulnerability had negative effect on attitude-and injunctive norm, but its overall indirect effect on healthy sleep patterns was very weak (standardised indirect effect = −.04, 95% CI [−.07, −.02]). Parental nurturance had positive effects on injunctive norm, descriptive norm, and PBC. Its standardised indirect effect on healthy sleep pattern was .09, 95% CI [.05, .13].

Discussion

The results of the correlational and path analyses support the efficacy of TPB in understanding healthy sleep intention and patterns of college students. As hypothesised, PBC and behavioural intention were significant correlates of self‐reported healthy sleep patterns. Behavioural intention was also positively associated with attitude, perceived norms, and PBC. These findings were consistent with the previous sleep research findings, which showed that TPB generally predicted behavioural intention and sleep behaviours of college students (Knowlden et al., Citation2012; Kor & Mullan, Citation2011). Many health behaviour studies supported that TPB‐based interventions were effective in modifying attitudes, perceived norms, and PBC, and then leading to desirable changes in students' intention and actual behaviours such as condom use (Caron, Godin, Otis, & Lambert, Citation2004) and breast‐feeding (Giles et al., Citation2014). In fact, TPB has also been recommended to be a useful theoretical framework for promotion programmes of healthy sleep (Blunden, Chapman, & Rigney, Citation2012), but there is a lack of empirical research on the effectiveness of its actual application. The current and past findings provide insight into how the efficacy of an intervention programme for healthy sleep can be promoted, but further research must be conducted to give empirical test of its efficacy.

The present findings filled in the knowledge gap, precisely that in addition to injunctive norm (Knowlden et al., Citation2012; Kor & Mullan, Citation2011), descriptive norm was also a significant factor of behavioural intention of healthy sleep. In fact, these two norms were positively correlated, indicating that one may be more likely to perceive a strong injunctive norm in the form of social pressure to engage in healthy sleep patterns if he/she also perceives that important others in his or her life are engaging in these practices (i.e., the descriptive norm). Furthermore, our respondents who perceived a strong injunctive norm for healthy sleep were more likely to report favourable attitudes. Similar positive effect of injunctive norms on attitudes towards drinking and driving was found among young adults (Chan et al., Citation2010). The cultural context of this study may also play a role. People from a collectivistic culture (e.g. Chinese culture) are more relationship oriented, and thus, they are more inclined to internalise their significant others' perspectives regarding a behaviour into their own perspectives (Chao, Citation1994; Grolnick, Deci, & Ryan, Citation1997), and to view that behaviour as important, good, and worth investing energy performing it when they perceive that their significant others want them to engage in that behaviour (Hernandez & Iyengar, Citation2001; Iyengar & Lepper, Citation1999).

Despite previous non‐significant findings (Kor & Mullan, Citation2011), a positive association between attitude and health sleep intention was observed. Consistent with the previous findings of intercorrelations among TPB constructs of health behaviours (Armitage, Norman, & Conner, Citation2002; Chan et al., Citation2010; Knowlden et al., Citation2012; Kor & Mullan, Citation2011), the present path model showed that both descriptive norm and attitude were associated with PBC over healthy sleep. Students might be empowered to practice good sleep habits through seeing these patterns modelled by their significant others. Furthermore, students who had a favourable attitude towards healthy sleep patterns might pay more attention to any available information, such as skills and aids, which would make these healthy sleep patterns possible and thus in turn promote the corresponding PBC.

The present findings also supported the potential protective role of parental nurturance. Students who perceived greater parental nurturance (i.e., more parental love and warmth) also perceived more supportive norms and stronger behavioural control regarding their healthy sleep patterns. As hypothesised, children in families of nurturing parenting were more likely to report a supportive atmosphere for healthy sleep, plausibly because nurturing parents were more likely to practice and encourage health habits at home. Moreover, children of nurturant parents tend to have higher global self‐esteem and sense of competence (Buri, Murphy, Richtsmeier, & Komar, Citation1992), which can be generalised to various specific behavioural domains, such as sleep patterns (Lemola, Räikkönen, Gomez, & Allemand, Citation2013). These plausible mechanisms of how parental nurturance can be translated into PBC and supportive norms deserve further research attention, particularly via longitudinal studies.

The present findings showed no significant correlation between perceived invulnerability and healthy sleep intention/patterns, but provided support to the negative associations between perceived invulnerability and cognitions (attitude and injunctive norm) related to healthy sleep. Students who perceived themselves as invulnerable to health risks were less likely to report favourable attitude and injunctive norm towards healthy sleep patterns. It is possible that those students' sense of invulnerability was also shared by their significant others (including their friends and families), who might not have believed that adhering to health behaviours like healthy sleep patterns was important and that the students should engage in them.

The findings of the current study offer practical insights into how to promote healthy sleep intention and patterns among college students through university‐based interventions. For example, we suggest incorporating psychoeducation into university campaigns to promote PBC via the provision of knowledge and techniques, such as time management skills. Also, the beneficial outcomes of healthy sleep, such as improved academic performance (Yeung, Chung, & Chan, Citation2008), can be explained to students to promote favourable attitudes. The current findings also highlight the importance of the perception of significant others' sleep practice (i.e. descriptive norms) and (dis)approval of one's (un)healthy sleep practice (i.e. injunctive norms). Therefore, we suggest establishing supportive social environments for healthy sleep patterns at home and in university. For example, mentors, instructors, and peer leaders may facilitate group discussions in which they share positive experiences and personal advice with students as to how to engage in healthy sleep patterns. Furthermore, college students who perceive themselves as being less supported by parents or more invulnerable to risks may be more likely to possess unfavourable attitude and norms regarding healthy sleep; these students may be identified through surveys distributed among freshmen and invited to participate in more intensive health workshops conducted at campus.

This study has several limitations. First, the present study relied on self‐report information, which may have been susceptible to biased reporting. Future research of sleep practice may involve reports from a parent or roommate. Second, the current sampling may limit the generalisability of the findings, and future research should recruit a more representative sample of emerging adults, with both students and non‐students. Third, causal relations among the concerned variables cannot be tested due to the cross‐sectional study design. To learn the predictive values of the psychosocial variables on healthy sleep intention and patterns, prospective and experimental studies are warranted. The internal consistency of the current measure of healthy sleep is also quite low, and this may account for its weak associations with some sleep‐specific variables (such as descriptive norm) in this study. Future research should develop a better measurement tool for healthy sleep patterns and then test the replicability of the current findings. Moreover, there is a debate on adequate sleep duration (Bin, Marshall, & Glozier, Citation2012; Bixler, Citation2009; Carskadon & Short, Citation2014) and thus its operational definition has been inconsistent across sleep studies. For instances, this study defined it as 7–9-hr, permitted by the PSQI, whereas Knowlden et al. (Citation2012) regarded 7–8-hr as adequate sleep. Compared with previous studies (e.g., Knowlden et al., Citation2012; Kor & Mullan, Citation2011), a longer time frame (i.e., 1 month) was set in the measurement of both the intentional and behavioural construct of volitional sleep patterns in this study. Therefore, current findings must be interpreted with caution when comparing with the findings of those studies. Meta‐analysis is recommended to test the moderating effects of these methodological differences on the associations between the TPB constructs and sleep behaviours when sufficient knowledge has been accumulated in the area.

To conclude, our resultant path model generally supported the application of TPB in understanding college students' healthy sleep intention and practices. Furthermore, it showed that the positive association between parental nurturance and healthy sleep intention was mediated by perceived norms and PBC. The negative association between perceived invulnerability and attitudes towards a specific health behaviour was also replicated in this college sample. However, the current extended model of TPB accounted for only about 43% and 19% of behavioural intention and patterns of healthy sleep respectively. The impacts of other physiological, behavioural, and environmental factors, such as computer or smart phone use and living environments, should be further investigated.

References

- Armitage, C. J., & Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behavior: A meta‐analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 471–499.

- Armitage, C. J., Norman, P., & Conner, M. (2002). Can the theory of planned behavior mediate the effects of age, gender and multidimensional health locus of control? British Journal of Health Psychology, 7(3), 299–316.

- Barber, L. K., & Munz, D. C. (2001). Consistent‐sufficient sleep predicts improvement in self‐regulatory performance and psychology strain. Stress and Health, 27, 314–324.

- Bentler, P. M. (1992). On the fit of models to covariances and methodology to the Bulletin. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 400–404.

- Bin, Y. S., Marshall, N. S., & Glozier, N. (2012). Secular trends in adult sleep duration: A systematic review. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 16(3), 223–230.

- Bixler, E. (2009). Sleep and society: An epidemiological perspective. Sleep Medicine, 10(Suppl. 1), S3–S6.

- Blunden, S. L., Chapman, J., & Rigney, G. A. (2012). Are sleep education programs successful? The case for improved and consistent research efforts. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 16(4), 355–370.

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Buboltz, W. R., Jenkins, S. M., Soper, B., Woller, K., Johnson, P., & Faes, T. (2009). Sleep habits and patterns of college students: An expanded study. Journal of College Counseling, 12(2), 113–124.

- Buri, J. R., Murphy, P., Richtsmeier, L. M., & Komar, K. K. (1992). Stability of parental nurturance as a salient predictor of self‐esteem. Psychological Reports, 71, 535–543.

- Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F. III, Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R., & Kupfer, D. J. (1989). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 28(2), 193–213.

- Caron, F., Godin, G., Otis, J., & Lambert, L. D. (2004). Evaluation of a theoretically based AIDS/STD peer education program on postponing sexual intercourse and on condom use among adolescents attending high school. Health Education Research, 19, 185–197.

- Carskadon, M. A., & Short, M. A. (2014). Measuring sleep need. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 18(5), 369–370.

- Chan, D. N., Wu, A. M. S., & Hung, E. H. W. (2010). Invulnerability and the intention to drink and drive: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 42(6), 1549–1555.

- Chao, R. (1994). Beyond parental control & authoritarian parenting style: Understanding Chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training. Child Development, 65, 1111–1119.

- Dement, W. C., & Vaughan, C. (1999). The promise of sleep: A pioneer in sleep medicine explores the vital connection between health, happiness, and a good night's sleep. New York: Dell.

- Duggan, P. M., Lapsley, D. K., & Norman, K. (2000). Adolescent invulnerability and personal uniqueness: Scale development and initial construct validation. Paper presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence, Chicago, IL.

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (2010). Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. New York: Psychology Press (Taylor & Francis.

- Galambos, N. L., Dalton, A. L., & Maggs, J. L. (2009). Losing sleep over it: Daily variation in sleep quantity and quality in Canadian students' first semester of university. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 19(4), 741–761.

- Giannotti, F., Cortesi, F., Sebastiani, T., & Ottaviano, S. (2002). Circadian preference, sleep and daytime behavior in adolescence. Journal of Sleep Research, 11(3), 191–199.

- Giles, M., Mcclenahan, C., Armour, C., Millar, S., Rae, G., Mallett, J., & Stewart‐knox, B. (2014). Evaluation of a theory of planned behaviour–based breastfeeding intervention in Northern Irish Schools using a randomized cluster design. British Journal of Health Psychology, 19(1), 16–35.

- Gradisar, M. M., Terrill, G. G., Johnston, A. A., & Douglas, P. P. (2008). Adolescent sleep and working memory performance. Sleep and Biological Rhythms, 6(3), 146–154.

- Greene, K., Rubin, D. L., & Hale, J. L. (1995). Egocentrism, message explicitness, and AIDS messages directed toward adolescents: An application of the theory of reasoned action. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 10, 547–570.

- Greene, K., Krcmar, M., Walters, L. H., Rubin, D. L., & Hale, J. L. (2000). Targeting adolescent risk‐taking behaviors: The contribution of egocentrism and sensation‐seeking. Journal of Adolescence, 23(4), 439–461.

- Grolnick, W. S., Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1997). Internalization within the family: The self‐determination theory perspective. In J. E. Grusec & L. Kuczynski (Eds.), Parenting and children's internalization of values: A handbook of contemporary theory (pp. 135–161). New York: John Wiley.

- Hernandez, B., Ramrez garcía, J. I., & Flynn, M. (2010). The role of familism in the relation between parent‐child discord and psychological distress among emerging adults of Mexican decent. Journal of Family Psychology, 24, 105–114.

- Hernandez, M., & Iyengar, S. S. (2001). What drives whom? A cultural perspective on human agency. Social Cognition, 19, 269–294.

- Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. R. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60.

- Hopkins, H. R., & Klein, H. (1993). Multidimensional self‐perception: Linkages to parental nurturance. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 154(4), 465–473.

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

- Huang, Y., Wang, C., & Guilleminault, C. (2010). An epidemiologic study of sleep problems among adolescents in north Taiwan. Sleep Medicine, 11(10), 1035–1042.

- Iyengar, S. S., & Lepper, M. K. (1999). Rethinking the value of choice: A cultural perspective on intrinsic motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 349–366.

- Knowlden, A. P., Sharma, M., & Bernard, A. L. (2012). A theory of planned behavior research model for predicting the sleep intentions and behaviors of undergraduate college students. Journal of Primary Prevention, 33, 19–31.

- Kor, K., & Mullan, B. A. (2011). Sleep hygiene behaviors: An application of the theory of planned behavior and the investigation of perceived autonomy support, past behavior and response inhibition. Psychology and Health, 26, 1208–1224.

- Lemola, S., Räikkönen, K., Gomez, V., & Allemand, M. (2013). Optimism and self‐esteem are related to sleep. Results from a large community‐based sample. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 20(4), 567–571.

- Louzada, F. M., da Silva, A. G. T., Peixoto, C. A. T., & Menna‐barreto, L. (2008). The adolescence sleep phase delay: Causes, consequences and possible interventions. Sleep Science, 1, 49–53.

- Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (2nd ed.). Sydney: Psychology Foundation.

- Millstein, S. G., & Halpern‐felsher, B. L. (2002). Judgements about risk and perceived invulnerability in adolescents and young adults. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(4), 399–422.

- Mueller, C. E., Bridges, S. K., & Goddard, M. S. (2011). Sleep and parent‐family connectedness: Links, relationships and implications for adolescent depression. Journal of Family Studies, 17(1), 9–23.

- Needham, B. L., & Austin, E. L. (2010). Sexual orientation, parental support, and health during the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(10), 1189–1198.

- Patock‐peckham, J. A., & Morgan‐lopez, A. A. (2009). Mediational links among parenting styles, perceptions of parental confidence, self‐esteem, and depression on alcohol‐related problems in emerging adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 70(2), 215–226.

- Reis, E. S., Lange, T., Kohl, G., Hermann, A., Tschulakow, A. V., & Naujoks, J. (2011). Sleep and circadian rhythm regulate circulating complement factors and immunoregulatory properties of C5a. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 25, 1416–1426.

- Statistics and Census Service (DSEC). (2013). Education survey 2011/2012. Retrieved April 11, 2015, from http://www.dsec.gov.mo/Statistic.aspx?NodeGuid=77e4b03a‐e3bb‐4c58‐81f9‐36e18600ca43

- Talbot, L. S., Stone, S., Gruber, J., Hairston, I. S., Eidelman, P., & Harvey, A. G. (2012). A test of the bidirectional association between sleep and mood in bipolar disorder and insomnia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121(1), 39–50.

- Tao, V. Y. K., & Hong, Y. Y. (2014). When academic achievement is an obligation: Perspectives from social‐oriented achievement motivation. Journal of Cross‐Cultural Psychology, 45(1), 110–136.

- Tsai, P. S., Wang, S. Y., Wang, M. Y., Su, C. T., Yang, T. T., Huang, C. J., & Fang, S. C. (2005). Psychometric evaluation of the Chinese Version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (CPSQI) in primary insomnia and control subjects. Quality of Life Research, 14(8), 1943–1952.

- Tsui, Y. Y., & Wing, Y. K. (2009). A study on the sleep patterns and problems of university business students in Hong Kong. Journal of American College Health, 58(2), 167–176.

- Wood, M. D., Read, J. P., Mitchell, R. E., & Brand, N. H. (2004). Do parents still matter? Parent and peer influences on alcohol involvement among recent high school graduates. Psychology of Addictive Behavior, 18(1), 19–30.

- Yeung, W., Chung, K., & Chan, T. (2008). Sleep‐wake habits, excessive daytime sleepiness and academic performance among medical students in Hong Kong. Biological Rhythm Research, 39(4), 369–377.

- Zee, P. C., & Turek, F. W. (2006). Sleep and health: Everywhere and in both directions. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(16), 1686–1688.