Abstract

Objective

Research has highlighted the role of gender in the expression of aggression. While boys display higher levels of physical aggression, girls appear to display higher levels of relational aggression. It is proposed that the expression of relational aggression may be associated, at least in part, with a child's development of language skills. The aim of the present study was to investigate the role of expressive and receptive language in the expression of relational aggression.

Method

A sample of 106 four to six‐year‐old Iranian children completed a test of language ability while their teachers completed a rating scale measuring the children's expression of relational aggression.

Results

Results supported the hypothesis that language skills play an important role in the development of relational aggression. Teachers reported that girls displayed significantly more relational aggression that boys. Girls were also found to have higher receptive and expressive language than boys. Finally, a mediation analysis found that language skills mediated the relationship between gender and relational aggression.

Conclusions

The results suggest that gender differences in the expression of relational aggression may be related to gender differences in the development of language as opposed to gender per se.

Key points

Relational aggression is behaviour that harms others through damage to social relationships, and can be distinguished from physical aggression.

Understanding relational aggression is becoming increasingly important as the rise of social media, and the accessibility of electronic devices provide a novel means for perpetrating relational aggression.

While boys are more likely to display physical aggression than girls, research is mixed on gender differences in the expression of relational aggression report mixed findings.

Relational aggression is an expression of aggression that requires the development of verbal and social skills.

Gender differences maybe an artefact of differences in language skills between genders.

Language skills were found to mediate the relationship between gender and relational aggression.

High levels of aggressive behaviour in early childhood can be a precursor of Oppositional Defiant Disorder and Conduct Disorder (Moffitt & Scott, Citation2008). These externalising problems are associated with poor developmental outcomes, including peer problems (Dodge, Citation1991), poor educational attainment (Rowe, Costello, Angold, Copeland, & Maughan, Citation2010), and other negative consequences later in life (Crick & Grotpeter, Citation1995). Half a century of research has shown that childhood aggression is related to temperament (Vitaro, Barker, Boivin, Brendgen, & Tremblay, Citation2006), can be modelled (for reviews see Anderson & Bushman, Citation2001; Kempes, Matthys, de Vries, & van Engeland, Citation2005), and can arise in the context of coercive family processes (Patterson, Citation2002; Patterson, Dishion, & Bank, Citation1984). However, the majority of this research has focused on physical aggression. The last decade has seen an increasing interest in relational aggression, defined as ‘behavior that harms others through damage (or the threat of damage) to relationships or feelings of acceptance, friendship or group inclusion’ (Crick, Casas, & Ku, Citation1999, p. 77). Relational aggression is an expression of aggression that requires the development of verbal and social skills. Children who display relationally aggressive behaviour have been found to experience high levels of depression, loneliness, peer rejection, and negative self‐perception (Crick & Grotpeter, Citation1995). While the use of relational aggression is not new in social situations, the rise of social media and the accessibility of mobile phones and other devices provides a novel means for perpetrating relational aggression. Given the negative impact of relational aggression on both perpetrators and victims, a greater understanding of this form of childhood aggression is clearly important.

The expression of relational aggression can be both direct and indirect (Crick, Ostrov & Werner, Citation2006). Direct relational aggression occurs when a child threatens a friend that they will no longer be friends, using phrases such as ‘you cannot play with me’ or ‘you can't be my friend’ (Crick & Grotpeter, Citation1995). Direct relational aggression can also be non‐verbal (e.g., placing hands on a chair so a child cannot sit at a table). Indirect relational aggression includes the spreading of rumours and gossip about another child (Crick et al, Citation2006). Relational aggression has been observed in children as young as three years of age (Crick et al., Citation1999). Preschool children generally employ more direct forms of relational aggression (Bailey & Ostrov, Citation2008), although sophisticated forms of indirect relational aggression can occur, such as trying to make the child look bad among a group of friends or silence treatment (Burr, Ostrov, Jansen, Cullerton‐Sen, & Crick, Citation2005). Direct and indirect forms of relational aggression become more prevalent during the school‐age years as cognitive abilities and social networks develop (Crick et al., Citation1999).

The expression of physical and relational aggression varies between boys and girls. It is widely accepted that physical aggression has a higher prevalence among boys (for reviews see Bettencourt & Miller, Citation1996; Card, Stucky, Sawalani, & Little, Citation2008; Renouf et al., Citation2010). However, the influence of gender on relational aggression is more controversial. Some studies (Bonica, Arnold, Fisher, Zeljo, & Yershova, Citation2003; Gomez‐Garibello & Talwar, Citation2015; Renouf et al., Citation2010) reported that girls appear to exhibit more relational aggression, while there is also reported evidence of more relational aggression among boys (Tomada & Schneider, Citation1997). Some studies have failed to find a significant difference between boys and girls in the expression of relational aggression (Crick, Casas, & Mosher, Citation1997; Swit & McMaugh, Citation2012). A possible explanation for a lack of consistency between studies may be related to the role of language and differences in the language ability of the children included in these studies. If language is important for the expression of relational aggression, it follows that greater language development would be associated with higher expression of relational aggression. In turn, because girls develop the social and verbal skills necessary to engage in relational aggression earlier than boys (Salmivalli, Kaukiainen, & Lagerspetz, Citation2001), they would also display relational aggression at a younger age. The expression of relational aggression in boys would be expected to increase as their language and social skills develop.

While gender differences remain controversial, less is known about the association between relational aggression and language skills. Bonica et al. (Citation2003) found that relational aggression was positively related to language development (specifically receptive and expressive vocabulary, and expressive language) in preschool children aged between 3 to 5 years old. In this study, language scores on the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test were more strongly associated with relational aggression for boys than girls. To the contrary, Hawley (Citation2003) found that relational aggression was positively correlated with receptive language in a sample of preschool‐aged girls but not in boys. Similarly, Estrem (Citation2005) found that expressive language skills more strongly predicted the relational aggression of preschool girls than preschool boys (aged between 36 and 66 months). Also that the highest rates of both relational and physical aggression was displayed by children who scored lowest on a measure of expressive and receptive language. In a series of studies carried out in Iran, Shahim (Citation2007, Citation2008) did not find any gender differences in relational aggression in a sample of Iranian preschool aged between 3 and 7. However, in a sample of elementary school children, boys were found to express higher levels of both overt and relationally aggressive behaviour than girls (Shahim, Citation2006). In these studies, school environment rather than the age of the child may have been important, as children in Iran attend mixed‐sex schools at preschool then move into single‐sex elementary schools. Overall, while the body of evidence to date suggests that the level of a child's language skills may mediate the relationship between gender and relational aggression, there is insufficient research and inconsistencies preventing any clear conclusion.

It is notable that the majority of research on relational aggression has been conducted in Western cultures (see Crick et al., Citation1999 for a review). The few studies that have investigated relational aggression in other cultures have been inconsistent. In a sample of Russian children, it was found that teachers, peers, and trained observers reported that girls expressed more relational aggression than boys Hart, Nelson, Robinson, Olsen, and McNeilly‐Choque (Citation1998). Other reports show that Italian boys expressed more relational aggression than girls Tomada and Schneider (Citation1997). Despite the paucity of research, cultural differences might be expected to determine the role of gender in the expression of relational aggression. In Iran, which is known to reflect collectivist cultural practices (Frank, Plunkett, & Otten, Citation2010; Ghorbani, Bing, Watson, Kristl Davison, & LeBreton, Citation2003), interpersonal relationships, maintaining friendships, maintaining a high level of satisfaction among the group and taking responsibility for other group members are all highly valued (Shahaeian, Peterson, Slaughter, & Wellman, Citation2011). Thus the threat of exclusion or ostracism may have different implications as a means of controlling the behaviour of others. For example, Behzadi (Citation1994) described the common use of silent treatment or qahr (in the Persian language) as a tool to control others in Iranian culture. It is possible that individuals who maintain a relationship orientation will be more likely to show relational aggression than individuals with an individualistic self‐construal (Ostrov & Godleski, Citation2010). If so, children from collectivist cultures may show relatively higher rates of relational aggression.

The aim of the present study was to assess gender differences in relational aggression in a group of Iranian preschool children and whether any observed differences in the expression of relational aggression was related to language development. It was hypothesised that (1) girls would show higher levels of relational aggression than boys; (2) girls would show higher levels of language skills than boys; and (3) language development would mediate the relationship between gender and relational aggression.

Method

Participants

One hundred and six children aged 4 to 6 years (Mean = 4.92, SD = 0.74) were recruited from four day care centres located in different suburbs in the city of Shiraz (sixth largest city in Iran; population: 1.2 million). The families varied in their average salary. The age of the children's mothers and fathers ranged from 23 to 49 (Mean = 31.96, SD = 5.46) and 27 to 60 (Mean = 36.90, SD = 5.63), respectively. Eighty‐five per cent of the parents held a high school diploma, 10.2% had finished high school, and 2.8% had elementary school education.

Procedure

During a monthly meeting held in each day care centre, a researcher met parents and explained the purpose of the study. Parents provided written consent for their child to participate. Questionnaires were given to teachers of the target child to complete, only if the teachers had known the child for at least five months. Administration of the language test took place in a quiet room in the preschool area. The first author tested all children individually. Each child took around 20 min to complete the language scale.

Measures

Relational aggression questionnaire for preschool children–teacher form

The questionnaire is a short form of the translated and adopted version of Crick and Grotpeter (Citation1995) relational aggression questionnaire which was adopted and used by Shahim (Citation2008) to assess the level of relational aggression displayed by Iranian children aged between 3 and 7 years. It includes 10 items using 3‐point likert scale: (1) rarely observed; (2) sometimes observed; and (3) frequently observed). The items included behaviours such as spreading malicious lies, gossip or secrets, ignoring or giving the silent treatment, and directly or covertly excluding a peer from an activity (e.g., ‘the child threatens a peer that he/she won't be invited to her/his birthday party’). Shahim (Citation2008) reported a Cronbach alpha of .92 in a study conducted in Iran.

Test of Language Development‐Primary: Third Edition (TOLD‐3; Newcomer & Hammill, Citation1997)

TOLD‐3 is an individually administered test to assess the language competence of children aged between 4–0 and 8–11. The TOLD‐3 scale was translated to Farsi and standardised for Iranian children by Hassanzade and Minayi (Citation2002). Only two subtests measuring receptive language (the ability to understand language and social cues) and expressive language (the ability to respond efficiently) were used in the present study. The receptive language subtest included items from scales measuring picture vocabulary and grammatical understanding. The expressive language subtest included items from scales measuring oral vocabulary and grammatical completion. Cronbach's alpha for expressive and receptive language skills were .90 and 82, respectively. Test–retest reliability has been found to range from .85 for expressive language to .88 for receptive language. Also, the internal consistency was reported to range from 0.74 for grammatical understanding to 0.89 for oral vocabulary subscales with test–retest reliability ranging from 0.78 for picture vocabulary to 0.85 for oral vocabulary (Hassanzade & Minayi, Citation2002).

Data analysis

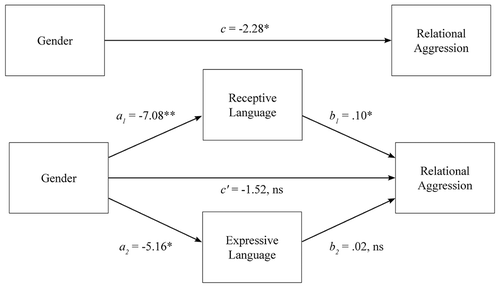

Missing data were excluded from data analyses on a case‐wise basis. Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS v21 (IBM Corp, Citation2012). The first hypothesis was tested using a t‐test was to assess whether girls show higher levels of relational aggression than boys. A further t‐test was carried out to test the second hypothesis that girls would have higher language skills than boys. The third hypothesis, that language development would mediate the relationship between gender and relational aggression, was tested by conducting a parallel mediation analysis using the SPSS PROCESS macro developed by Hayes (Citation2013). The parallel mediation model tested is represented in Fig. 1. Path c refers to the total effect of gender on relational aggression in the absence of the mediators. Path c′ refers to the direct effect of gender on relational aggression when controlling for the mediators. Specific indirect effects refer to the influence of path a × path b via each specific mediator (a1 × b1 is the indirect effect of gender on relational aggression via receptive language; a2 × b2 is the indirect effect of gender on relational aggression via expressive language. The total indirect effect reflects the summation of the specific indirect effects. Similar to R in a multiple regression analysis, the total indirect effect tests whether language skills mediate the association between gender and relational aggression.

Figure 1. Parallel multiple mediation model showing direct and indirect effects.

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01; ns = not significant.

a = unstandardised IV to mediator coefficient, b = unstandardised mediator to DV coefficient, c = unstandardised total effect (IV to DV), c′ = unstandardised direct effect. Subscripts refer to specific indirect paths. Gender coded 1 = female, 0 = male. DV = relational aggression; IV = gender.

Results

The means and standard deviations for the measures of relational aggression and language development are presented in Table . A t‐test was carried out to test the first hypothesis that girls would show higher levels of relational aggression than boys. The results found that teachers reported significantly higher levels of relational aggression in girls than boys (t(104) = 2.49, p = .014, Cohen d = .48). A further t‐test carried out to test the second hypothesis that girls would have higher language skills than boys, found that girls scored higher than boys on both the expressive (t(104) = 2.32, p = .022, Cohen d = .45) and receptive language scales (t(104) = 2.61, p = .011, Cohen d = .51). A parallel multiple mediation analysis conducted using the PROCESS macro (Model 4; Hayes, Citation2013) found that receptive language, but not expressive language, mediated the relationship gender and relational aggression. The total direct effect of the model (path c in Fig. 1) was a significant predictor of relational aggression (R2 = .06, F(1, 104) = 6.19, p = .014). However, when the effects of receptive and expressive language were statistically controlled in the mediation analysis, the direct effect of gender on relational aggression (path c’) was no longer significant (see Fig. 1). The overall mediation model found that the combined effects of gender and the two mediators (receptive and expressive language) was significant and explained 15% of the variance in relational aggression (R2 = .15, F(3, 102) = 5.90, p < .001). The total indirect effect was significant (–.76, SE = .37, 95% CI: −1.68 to −0.19). On closer inspection of the specific indirect effects, the indirect effect of gender on relational aggression through receptive language was found to be significant (–.69, SE = .38, (95% CI: −1.6376 to −.1281). However the indirect effect of gender on relational aggression through expressive language was not significant. Thus, receptive language, but not expressive language skills, was found to mediate the relationship between gender and relational aggression.

Table 1. Means and standard deviations of measures of relational aggression and language development

Discussion

The present study examined the role of gender and language in the expression of relational aggression in a group of Iranian children. The findings of this study are consistent with prior studies that found girls displayed higher levels of relationally aggressive behaviour than boys (Crick & Grotpeter, Citation1995; Bonica et al., Citation2003; Russell, Hart, Robinson, & Olsen, Citation2003; Murray‐Close, Ostrov, & Crick, Citation2007). Girls were also found to have more advanced language skills than boys. The hypothesis that gender would not be significantly associated with relational aggression after controlling for language was supported. This finding is consistent with previous studies that have shown children with a higher level of language ability, irrespective of gender, are more likely to engage in relational aggression (Bonica et al., Citation2003). Overall, the results of this study suggest that language may play a more important role in the expression of relational aggression than gender.

With regard to gender differences, two reasons can be suggested why girls express more relational aggression. First, it seems that girls are equipped with a more complex communication tool (better language skills, Keenan & Shaw, Citation1997), which makes them more skilled in learning and using relationally aggressive strategies and to verbally manipulate a relationship (McNeilly‐Choque, Hart, Robinson, Nelson, & Olsen, Citation1996). In other words, stronger language skills might facilitate relationally aggressive behaviours among girls. Second, girls have more opportunities to manipulate relationships. Girls are more vulnerable to use relational aggression, as they often have higher levels of intimate exchange than boys (Parker &Asher, Citation1993) and relationally aggressive behaviour is often used in close relationships (Grotpeter & Crick, Citation1996). More specially, having broader social relationships, having more frequent contact with peers, and having more personal knowledge of peers, will make girls vulnerable to use relational aggression (Grotpeter & Crick, Citation1996).

Of interest, the present study found that receptive language, but not expressive language, predicted relational aggression after controlling for gender. Receptive language skills are important in understanding social cues (Dodge, Pettit, McClaskey, Brown & Gottman, Citation1986) and are highly correlated with cognitive abilities important in the development of relationally aggressive strategies (Crick et al., Citation1997). Children with higher receptive language skills may employ non‐verbal relational aggression at this age to exclude peers and to gain a higher social status (e.g., turning their back to another child when they are mad at them) rather than use expressive language skills such as directly saying ‘we don't play with boys’.

The relationship between receptive language and relational aggression found in the present study is not consistent with prior research that has reported expressive language to be more strongly associated with relational aggression than receptive language skills (Estrem, Citation2005). To speculate on the reasons for this, it could be argued that receptive language skill is associated with general cognitive abilities and better social skills. Children with higher receptive language are more likely to build and maintain larger social circles, providing then with more opportunity to use relational aggression. Alternatively, it is possible that this finding may reflect cultural factors. Explicit disagreement (such as arguing) with other people is not a well‐regarded means of communication in Iranian culture. People prefer not to be involved in direct conversations when they disagree with others (Shahaeian et al., Citation2011; Shahaeian, Nielsen, Peterson, & Slaughter, Citation2014) and Iranian children are actively encouraged to think carefully of what they say to their friends and not express what they think. However, this is speculative and further research replicating this result is required to determine whether the relationship between receptive rather than expressive language and relational aggression in Iranian children is a robust finding.

The current research was one of the few studies using non‐Western samples to study relational aggression (Hart et al., Citation1998; Tomada & Schneider, Citation1997). It is interesting to note that the mean scores on the measure of relational aggression in this sample of Iranian children was one standard deviation higher than that found in a sample of American children (M = 15.6, SD = 4.7, for Iranian children; M = 10.2, SD = 4.2, for American children; Bonica et al., Citation2003). This lends support to the argument put forward by Shahaeian et al. (Citation2011) that Iranian families place a greater emphasis on relationships than American families, potentially making children more vulnerable to the manipulations of relational aggression with their peers. Also in Iranian culture, as a collective interdependent culture that values social cooperation, group harmony and close relationships, people avoid direct encounters, and are more likely to engage in indirect forms of showing dissatisfaction towards others (Behzadi, Citation1994). Future studies directly comparing children raised in collectivist and individualistic cultures is required to better understand possible cultural differences in the expression of relational aggression.

Overall, the present study points to the importance of language skills over and above gender in the expression of relational aggression. Further studies are now needed to better understand the role of receptive and expressive language, social skills, and the impact of culture on the expression of relational aggression.

References

- Anderson, C. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2001). Effects of violent video games on aggressive behavior, aggressive cognition, aggressive affect, physiological arousal, and prosocial behavior: A meta‐analytic review of the scientific literature. Psychological Science, 12, 353–359.

- Bailey, C. A., & Ostrov, J. M. (2008). Differentiating forms and functions of aggression in emerging adults: Associations with hostile attribution biases and normative beliefs. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 713–722. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964‐007‐9211‐5

- Behzadi, K. (1994). Interpersonal conflict and emotions in an Iranian cultural practice: Qahr and ashti. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 18, 321–359. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01379230

- Bettencourt, B., & Miller, N. (1996). Gender differences in aggression as a function of provocation: A meta‐analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 422–447. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033‐2909.119.3.422

- Bonica, C., Arnold, D. H., Fisher, P. H., Zeljo, A., & Yershova, K. (2003). Relational aggression, relational victimization, and language development in preschoolers. Social Development, 12, 551–562. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467‐9507.00248

- Burr, J. E., Ostrov, J. M., Jansen, E. A., Cullerton‐sen, C., & Crick, N. R. (2005). Relational aggression and friendship during early childhood: ‘I won't be your friend!’. Early Education & Development, 16, 161–184. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15566935eed1602_4

- Card, N. A., Stucky, B. D., Sawalani, G. M., & Little, T. D. (2008). Direct and indirect aggression during childhood and adolescence: A meta‐analytic review of gender differences, intercorrelations, and relations to maladjustment. Child Development, 79, 1185–1229.

- Crick, N. R., & Grotpeter, J. K. (1995). Relational aggression, gender, and social‐psychological adjustment. Child Development, 66, 710–722. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467‐8624.1995.tb00900.x

- Crick, N. R., Casas, J. F., & Mosher, M. (1997). Relational and overt aggression in preschool. Developmental Psychology, 33, 579–588. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0012‐1649.33.4.579

- Crick, N. R., Casas, J. F., & Ku, H.‐C. (1999). Relational and physical forms of peer victimization in preschool. Developmental Psychology, 35, 376–385. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0012‐1649.35.2.376

- Crick, N. R., Ostrov, J. M., & Werner, N. E. (2006). A longitudinal study of relational aggression, physical aggression, and children's social‐psychological adjustment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34, 131–142. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802‐005‐9009‐4

- Dodge, K. A. (1991). Social information‐processing variables in the development of aggression and altruism in children. In C. Zahn‐waxler, E. M. Cummings, & R. J. Iannotti (Eds.), Altruism and Aggression: Social and Biological Origins (pp. 280–302). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dodge, K. A., Pettit, G. S., Mcclaskey, C. L., Brown, M. M., & Gottman, J. M. (1986). Social competence in children. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 51, 1–85. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1165906

- Estrem, T. L. (2005). Relational and physical aggression among preschoolers: The effect of language skills and gender. Early Education and Development, 16, 207–232. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15566935eed1602_6

- Frank, G., Plunkett, S. W., & Otten, M. P. (2010). Perceived parenting, self‐esteem, and general self‐efficacy of Iranian American adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19, 738–746.

- Ghorbani, N., Bing, M. N., Watson, P., Kristl davison, H., & Lebreton, D. L. (2003). Individualist and collectivist values: Evidence of compatibility in Iran and the United States. Personality and Individual Differences, 35, 431–447. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191‐8869(02)00205‐2

- Gomez‐garibello, A., & Talwar, V. (2015). Can you read my mind? Age as a moderator in the relationship between theory of mind and relational aggression. International Journal of Behavioral Development, doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025415580805

- Grotpeter, J. K., & Crick, N. R. (1996). Relational aggression, overt aggression, and friendship. Child Development, 67, 2328–2338. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1131626

- Hart, C. H., Nelson, D. A., Robinson, C. C., Olsen, S. F., & Mcneilly‐choque, M. K. (1998). Overt and relational aggression in Russian nursery‐school‐age children: Parenting style and marital linkages. Developmental Psychology, 34, 687. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0012‐1649.34.4.687

- Hassanzade, S., & Minayi, A. (2002). Adaption and language development test TOLD‐P: 3 for children of Persian speaking language (part I). Research on Exception Children, 1, 34–119.

- Hawley, P. H. (2003). Strategies of control, aggression, and morality in preschoolers: An evolutionary perspective. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 85, 213–235. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022‐0965(03)00073‐0

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression‐Based Approach. New York: Guildford Press.

- IBM Corp. (2012). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. IBM Corp., Armonk, NY.

- Keenan, K., & Shaw, D. (1997). Developmental and social influences on young girls' early problem behavior. Psychological Bulletin, 121, 95–113. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033‐2909.121.1.95

- Kempes, M., Matthys, W., de Vries, H., & van Engeland, H. (2005). Reactive and proactive aggression in children A review of theory, findings and the relevance for child and adolescent psychiatry. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 14, 11–19.

- Mcneilly‐choque, M. K., Hart, C. H., Robinson, C. C., Nelson, L. J., & Olsen, S. F. (1996). Overt and relational aggression on the playground: Correspondence among different informants. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 11, 47–67.

- Moffitt, T. E., & Scott, S. (2008). Conduct Disorders of Childhood and Adolescence. In M. Rutter, D. Bishop, D. Pine, S. Scott, J. S. Stevenson, E. A. Taylor, & A. Thapar (Eds.), Rutter's Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (5th ed., pp. 543–564). Malden: MA Blackwell Publishing.

- Murray‐close, D., Ostrov, J. M., & Crick, N. R. (2007). A short‐term longitudinal study of growth of relational aggression during middle childhood: Associations with gender, friendship intimacy, and internalizing problems. Development and Psychopathology, 19, 187–203. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579407070101

- Newcomer P. L., & Hammill, D. D. (1997). Test of language development‐primary. 3rd Pro‐Ed, Inc., Austin, TX.

- Ostrov, J. M., & Godleski, S. A. (2010). Toward an integrated gender linked gender model of aggression subtypes in early and middle childhood. Psychological Review, 117, 233–242. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018070

- Parker, J. G., & Asher, S. R. (1993). Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology, 29, 611–621. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0012‐1649.29.4.611

- Patterson, G. R. (2002). The early development of coercive family process. In J. B. Reid, G. R. Patterson, & J. Snyder (Eds.), Antisocial Behavior in Children and Adolescents: A Developmental Analysis and Model for Intervention (pp. 25–44). Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

- Patterson, G. R., Dishion, T. J., & Bank, L. (1984). Family interaction: A process model of deviancy training. Aggressive Behavior, 10, 253–267. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/1098‐2337

- Renouf, A., Brendgen, M., Parent, S., Vitaro, F., David zelazo, P., Boivin, M., … Séguin, J. R. (2010). Relations between theory of mind and indirect and physical aggression in kindergarten: Evidence of the moderating role of prosocial behaviors. Social Development, 19, 535–555. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467‐9507.2009.00552.x

- Rowe, R., Costello, E. J., Angold, A., Copeland, W. E., & Maughan, B. (2010). Developmental pathways in oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119, 726–738. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020798

- Russell, A., Hart, C. H., Robinson, C. C., & Olsen, S. F. (2003). Children's sociable and aggressive behaviour with peers: A comparison of the US and Australia, and contributions of temperament and parenting styles. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 27, 74–86. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250244000038

- Salmivalli, C., Kaukiainen, A., & Lagerspetz, K. (2001). Aggression and sociometric status among peers: Do gender and type of aggression matter? Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 41, 17–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467‐9450.00166

- Shahaeian, A., Peterson, C. C., Slaughter, V., & Wellman, H. M. (2011). Culture and the sequence of steps in theory of mind development. Developmental Psychology, 47, 1239–1247. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023899

- Shahaeian, A., Nielsen, M., Peterson, C., & Slaughter, V. (2014). Cultural and family influences on children's theory of mind development: A comparison of Australian and Iranian school‐age children. Journal of Cross‐Cultural Psychology, 45, 555–568. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022113513921

- Shahim, S. (2006). Overt and relational aggression among elementary school children. Psychological Research, 9, 27–44.

- Shahim, S. (2007). Relational aggression in preschool children. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 13, 264–271.

- Shahim, S. (2008). Sex differences in relational aggression in preschool children in Iran. Psychological Reports, 102, 235–238. doi:https://doi.org/10.2466/PRO.1021.235‐238

- Swit, C., & Mcmaugh, A. (2012). Relational aggression and prosocial behaviours in Australian preschool children. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 37, 30–34.

- Tomada, G., & Schneider, B. H. (1997). Relational aggression, gender, and peer acceptance: Invariance across culture, stability over time, and concordance among informants. Developmental Psychology, 33, 601–609. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0012‐1649.33.4.601

- Vitaro, F., Barker, E. D., Boivin, M., Brendgen, M., & Tremblay, R. E. (2006). Do early difficult temperament and harsh parenting differentially predict reactive and proactive aggression? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34, 681–691. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802‐006‐9055‐6