Abstract

Objective

Psychological literacy has been proposed as an outcome for psychology graduates, which requires an understanding of and integration between theory, research, and practice. Using the expectancy‐value theory, the current study aimed to examine psychology students’ values and self‐efficacy towards these domains.

Method

Three hundred and nineteen psychology students (M age = 26.25, SD = 10.26) reported on their social influences, task values, and self‐efficacy beliefs for theory, research, and practice.

Results

Using 3 (Year) × 3 (Domain) mixed factorial analyses of variance (ANOVAs), it was shown that students have poorer task values and lower self‐efficacy towards research than theory or practice. A consistent effect of year was not found for task values, but students’ self‐efficacy beliefs showed an effect of training, with first years reporting poorer self‐efficacy than middle and fourth‐year students. Results indicated that students hold contrasting views of what they perceive friends and family to value compared to their perception of what academic staff value.

Conclusions

It was recommended that the undergraduate curriculum promote equal values across theory, research, and practice by integrating education in the three domains. Utility interventions are discussed as a cost‐effective way to improve task values and performance in learning domains that are not well‐valued by students.

Key words:

TASK VALUES AND SELF‐EFFICACY BELIEFS OF PSYCHOLOGY STUDENTS

The current model of education and training in psychology has been hotly debated since the scientist‐practitioner (S‐P) model of training was introduced in the Boulder Summit of 1949 (Raimy, Citation1950). This model aimed to integrate science and practice in psychology education and training and, despite its criticisms, has become integral to psychology education (Belar & Perry, Citation1992; Stoltenberg & Pace, Citation2007). In Australia, while the S‐P model forms the basis of programmes accredited by the Australian Psychology Accreditation Council (APAC, Citation2010), elements of the S‐P model are not equally weighted in undergraduate and postgraduate degrees (Australian Psychological Society [APS], Citation2012; Provost et al., Citation2010). Instead, the initial 4 years of undergraduate psychology education strongly emphasise the science of psychology, providing ‘broad foundational knowledge, […] strong skills in research methods, data analysis and report writing’ (Cranney et al., Citation2009, p. 253).

Traditionally, psychology programmes in Australia have favoured a ‘science first, train later’ interpretation of the S‐P model and one that does not typically provide an integrative approach. A major problem with this is the limited number of fourth‐year places, which allows less than half of third‐year psychology graduates to progress into fourth‐year studies (Cranney, Botwood, & Morris, Citation2012). As the fourth year is required for supervised practice or postgraduate training, this means a significant proportion of undergraduates will not be exposed to the applied component of psychology education (APS, Citation2012). To resolve this issue, Cranney et al. (Citation2009, Citation2012) have argued that psychology graduates need to develop psychological literacy and that the place to do so is in the first 3 years of psychology education (Cranney et al., Citation2012).

Psychological literacy is defined as the capacity to effectively and intentionally apply the science of psychology to problems of a psychological nature, spanning an individuals’ personal and professional life, and to problems affecting their social environment at local and global levels (Cranney & Dunn, Citation2011). Cranney et al. (Citation2009) established a set of six graduate attributes (GAs) for undergraduate psychology, which were incorporated into the APAC (Citation2010) Standards. Psychological literacy is intended to align with the sixth GA, learning, and its application (Morris, Cranney, Jeong, & Mellish, Citation2013). However, as the ability to apply psychological knowledge to a range of problems stems from students’ ability to effectively integrate psychological knowledge, students must attain a high level of competence with each GA to develop psychological literacy (Cranney et al., Citation2009). The three main components of psychological knowledge are described in Table , mapped against the relevant GA.

Table 1. A comparison of the three content domains with their source graduate attributes

Expectations of psychology education and student values

Students rarely enter psychology programmes with equal values towards theory, research, and practice. Prior research suggests first‐year students are often unaware of the extent of research training in psychology, which is an area of concern for educators (Rowley, Hartley, & Larkin, Citation2008). Research has also suggested that students expect a significant proportion of psychology training to address advanced clinical or helping skills, skills that are largely absent from the undergraduate programme (Gaither & Butler, Citation2005; Goedeke & Gibson, Citation2011). Therefore, students entering undergraduate studies, especially those who are most passionate about professional practice in psychology, may become dissatisfied or disengage early due to the mismatch between their expectations and experiences (Holmes, Citation2014). A consideration of students’ values and expectancies is important if the overall value of psychology education is to be improved.

Expectancy‐value theory (EVT) of achievement motivation (Eccles et al., Citation1983) aims to explain students’ choice to invest time and effort into learning a specific topic. According to EVT, these choices are influenced by task attributions made by students, composed of subjective task values and self‐efficacy beliefs (Wigfield & Eccles, Citation1992). Task values refer to four attributions made towards a topic (Wigfield & Eccles, Citation1992, Citation2000), including how interesting students’ find learning about a topic (intrinsic value), how important they perceive performing well in a topic (attainment value), how useful the topic is to their future (utility value), and how difficult and time‐consuming they perceive learning a topic to be (cost value). Some researchers have suggested that intrinsic and utility task values are most important for a range of outcomes, including course decisions and performance (Hulleman, Durik, Schweigert, & Harackiewicz, Citation2008). EVT has been used to predict psychology students’ performance in a second‐year statistics course, accounting for 40% of the variance in students’ achievement (Hood, Creed, & Neumann, Citation2012).

According to EVT, students’ values are formed, in part, through their socialisation towards a domain by important people in their lives and those with authority or expertise in the area (Eccles & Wigfield, Citation2002). This socialisation involves the attitudes, expectations, beliefs, values, and behaviours of these influential others. Thus, how each domain is introduced will influence the extent to which a student values that domain (Jacobs & Eccles, Citation2000). For a student, those who teach and support them would be considered part of their social environment (i.e., family, friends, tutors, and lecturers). The attitudes that family and friends communicate can influence both the values and self‐efficacy beliefs students’ hold towards the domains (Jacobs & Eccles, Citation2000; Osborne & Jones, Citation2011). However, the values of academic staff may contradict those of family and friends as research suggests that undergraduate instructors hold stronger preferences for scientist over practitioner interests (Holmes, Citation2014).

Self‐efficacy (Bandura, Citation1997), defined as a student's confidence in their ability to possess and employ the necessary skills to succeed in a given task, has been shown to be important in predicting academic performance (Eccles & Wigfield, Citation1995). Interestingly, students’ task values assessed mid‐semester were found to be better predictors of course performance and enrolment intentions than self‐efficacy beliefs (Bong, Citation2004). However, at the end‐of‐semester, self‐efficacy best predicted students’ final exam performance (Bong, Citation2004), suggesting that positive task values are most important for willingness to develop knowledge, while self‐efficacy is important for maintaining efforts towards developing competence.

This article investigates students’ task values and self‐efficacy beliefs towards theory, research, and practice in psychology education. In line with the literature, it was expected that first‐year students’ family and friends would value practice over theory and research. In contrast, it was expected that academic staff would be perceived by first years to value research and theory over practice (Holmes, Citation2014). Furthermore, students’ friends and family were hypothesised to have the greatest influence on intrinsic and utility values during the first year. Thus, first‐year students would report greater interest in practice than theory and research and would also report practice to be more useful.

Consistent with prior research, it was expected that students’ intrinsic and utility values would become more similar to those of academic staff in their later years of study. Hence, students in second and third years would report greater interest and perceived utility for theory and research than practice. As research suggests that students report more difficulty with research topics, it was expected that the cost value would remain high for the research domain throughout the first, second, and third year. In the fourth year, given that students have completed an undergraduate sequence in psychology, it was hypothesised that these students would report equal intrinsic, utility, and cost value towards each of the three domains. For attainment value, it was expected that theory, research, and practice would be valued equally in all year levels as the importance of obtaining a good grade should not vary by year.

In developing self‐efficacy for using theory, research, and practice in psychologically literate ways, it was expected that there would be an effect of year level, with first‐year students reporting the lowest self‐efficacy for all three domains. Students in their middle years should have developed self‐efficacy for using theory and research but were not expected to have developed self‐efficacy for using practice as the 3‐year degree does not provide students with sufficient experience with this domain. As fourth‐year students have reached the end of their undergraduate degree, it was expected that their self‐efficacy for using theory, research, and practice in psychologically literate ways would be equal for the three domains.

METHOD

Participants and procedure

The sample consisted of 319 psychology students aged between 17 and 68 years (M = 26.38, SD = 10.29, 245 females). There were 103 students in their first year, 69 students in second year, 45 students in third year, and 102 students in fourth year. The current sample was obtained through 22 universities and private colleges offering accredited undergraduate sequences in psychology. There was a comparable sample from different‐level institutions and preliminary analyses detected no difference in target measures. Students were recruited online through the provider's learning website or mass email with approval from the relevant Head of School. The study was also advertised on social media using psychology interest groups. The study was approved by the University Human Research Ethics Committee and endorsed by HREC committees in participating universities where required. A prize draw incentive was provided for all students, and first‐year students in eligible courses were offered research participation credit.

Measures

The measures used for the current study were pilot‐tested on a sample of 78 undergraduate psychology students from three universities, demonstrating good reliabilities and small to large effect sizes (Cohen's d = 0.26–1.33). All measures were presented on a 6‐point Likert response scale with no neutral midpoint, for example, from 1 ‘Strongly Disagree’ to 6 ‘Strongly Agree’ with ‘Somewhat Disagree’ and ‘Somewhat Agree’ as midpoints. Scale anchors were matched to the question text, for example, ‘Not at all’ to ‘A great deal’. Definitions for research, theory, and practice (see Table ) were provided to participants for each of the three domains during the survey.

Social influences

Two social influences (personal and academic) scales were generated. The personal social influences scale assessed the extent to which students perceived that their friends and family valued their learning of theory, research, and practice in psychology. The academic social influences scale assessed the extent to which students perceived tutors and lecturers to value learning in theory, research, and practice within psychology. Cronbach's alpha for the 2‐item personal social influences scale was .62 for theory, .74 for research, and .79 for practice. Cronbach's alpha for the 2‐item academic social influences scale was .92 for theory, .94 for research, and .96 for practice.

Subjective task values

The four task values were measured with 5‐item subscales. These items were generated using item stems from the Self‐and‐Task Perception Questionnaire (STPQ; Parsons et al., Citation1980, as cited in Eccles & Wigfield, Citation1995) and the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ) by Pintrich, Smith, Garcia, and McKeachie (Citation1991). For each domain, students rated their agreement with items from the four subscales. Internal consistency of the task value scales ranged from acceptable to excellent; these are provided with example items for each domain in Table .

Table 2. Means (M), standard deviations (SD), and scale reliabilities of task values with example items (N = 319)

Self‐efficacy beliefs

A 7‐item measure of self‐efficacy for using theory, research, and practice in psychologically literate ways was developed. Each item had the question stem, ‘To what extent do you feel confident expressing/applying your knowledge of…’ adapted from the Self‐efficacy scale of the MSLQ (Pintrich et al., Citation1991). This measure assessed students’ confidence in their knowledge of each domain and their confidence in their ability to apply each domain to personal, professional, and societal problems. As this scale was developed for the current study, the factor structure of the self‐efficacy scale was examined for each domain using principal components analysis (PCA) with a varimax rotation. A simple factor structure emerged for research (Cronbach's α = .92) and practice (α = .94). Theory items loaded on two factors, representing students’ confidence in expressing and applying theoretical knowledge. However, due to high cross‐loadings and a reliable factor structure (α = .83), a simple factor structure was retained for theory.

RESULTS

Initial analysis of second‐ and third‐year student responses on the dependent variables indicated that these groups did not differ significantly; as such, these groups were combined to form a middle‐year group (n = 114). A series of 3 (Year: first, Middle, fourth) × 3 (Domain: theory, research, practice) mixed factorial analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted using each of the personal social influences, academic social influences, task values, and self‐efficacy measures as dependent variables. In all analyses, a violation to the assumption of sphericity was detected using Mauchly's Test (all ps < .001), to which the Huyhn‐Feldt correction was applied (Keppel, Citation1991). Other assumptions of the analysis were acceptable.

Social influences

Personal social influences

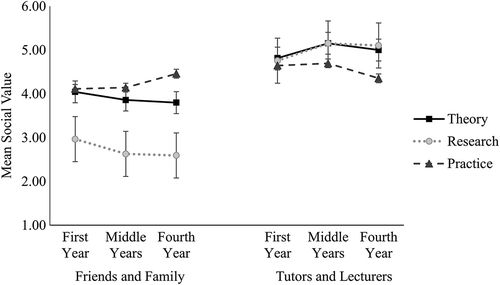

There was a significant main effect of Domain, F(2, 572) = 243.48, p < .001, ηp 2 = .44, which was modified by a significant Domain–Year interaction, F(4, 572) = 4.41, p = .001, ηp 2 = .03. There was no significant main effect of Year, F(2, 316) = 0.88, p = .418. As predicted, students in all year levels perceived family and friends to value practice significantly more than research (all ps < .001; see Fig. 1). Contrary to expectations, the first‐year group perceived family and friends to value research significantly more than students in the middle‐ (p = .039) and fourth‐year groups (p = .027). Furthermore, first‐year students reported no difference in the values of family and friends for theory and practice, while both middle years (p = .010) and fourth years (p < .001) thought family and friends would value practice more than theory.

Academic social influences

There was a significant main effect of Domain, F(2, 527) = 30.26, p < .001, ηp 2 = .09, with no effect of Year, F(2, 316) = 2.47, p = .087. There was a significant interaction, F(3, 527) = 4.34, p = .004, ηp 2 = .03, which was explained by differences between the first‐year group and students of the later years. During the first year, students perceived academic staff to value all three domains equally (all ps > .05). Students in later years perceived academic staff to value theory and research significantly more than practice (all ps < .001, see Fig. 1).

Subjective task values

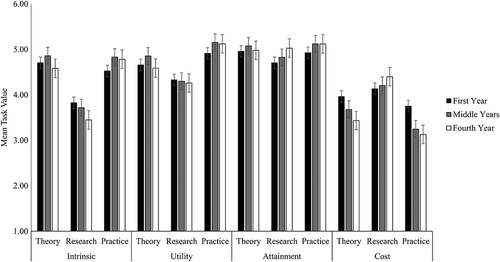

Previous research has found a positive association between intrinsic, attainment, and utility value (Eccles & Wigfield, Citation1995). However, due to a violation of homogeneity of regression, intrinsic value could not be used as a covariate in analyses of attainment and utility values. The correlations between these values are reported in Table . Significant positive associations were found between the task values for all domains, except for intrinsic value for research, which was not associated with intrinsic, attainment, or utility value for practice. This indicates that research interest was not associated with students’ values towards practice. The mean intrinsic, utility, attainment, and cost value for theory, research, and practice are presented in Fig. 2.

Table 3. Correlations between intrinsic, attainment, and utility task values (N = 319)

Intrinsic value

There was a significant main effect of Domain, F(2, 535) = 151.16, p < .001, ηp 2 = .32, with no significant main effect of Year, F(2, 316) = 2.38, p = .094. The Domain–Year interaction was significant, F(3, 535) = 3.59, p = .010, ηp 2 = .02. It was expected that students’ intrinsic values would reflect personal social influences during the first year and academic social influences in later years. However, students in all years reported research to be significantly less interesting than both theory and practice (all ps < .001), with fourth‐year students reporting significantly less interest in research than even first‐year students (p = .023).

Utility value

There was a significant main effect of Domain, F(2, 577) = 107.35, p < .001, ηp 2 = .25, with no significant main effect of Year, F(2, 316) = 1.51, p = .222. The Domain–Year interaction was significant, F(4, 577) = 2.65, p = .037, ηp 2 = .02. It was expected that students’ perception of usefulness would also reflect their social influences across the year levels. However, students in all years reported practice to be significantly more useful than theory and theory to be more useful than research (all ps ≤ .002). Students in their middle years perceived theory to be significantly more useful than both first‐ (p = .046) and fourth‐ year (p = .007) groups, which may be an impact of the strong theoretical focus of coursework in the middle years.

Attainment value

There was a significant main effect of Domain, F(2, 605) = 11.45, p < .001, ηp 2 = .04, with no significant main effect of Year, F(2, 316) = 2.26, p = .106, and a significant Domain–Year interaction, F(4, 605) = 2.65, p = .034, ηp 2 = .02. It was expected that attainment value would not be significantly different across the three domains or year levels. This was supported only in the fourth‐ year group (all ps > .05). During the first and middle years, students reported significantly greater attainment value for theory (p = .001) and practice (p = .011) than research.

Cost value

There was a significant main effect of Domain, F(2, 531) = 119.85, p < .001, ηp 2 = .28, and Year, F(2, 316) = 7.07, p = .001, ηp 2 = .04, which were modified by a significant interaction, F(3, 531) = 12.42, p < .001, ηp 2 = .07. Students’ cost value showed an effect of year: first‐year students reported a significantly higher cost value for theory than middle‐year students (p = .004), who in turn reported significantly higher cost than fourth‐year students (p = .012). First years also reported higher cost for research (p = .040) when compared to fourth years, although middle‐year students were not significantly different from first or fourth years (ps ≥ .126). Finally, first‐year students considered practice to be more costly than middle‐ and fourth‐year students (ps < .001), with no difference between the latter groups (p = .283).

It was expected that first and middle years would consider research more costly than theory and practice, while fourth‐year students would rate all domains equally. This was supported only in the middle‐years group; first‐year students considered both theory (p = .013) and research (p = .002) to be significantly more costly than practice, with no significant difference between theory and research (p = .063). Both middle‐ and fourth‐year students reported a significantly higher cost value for research than theory and theory to be significantly more costly than practice (all ps < 001).

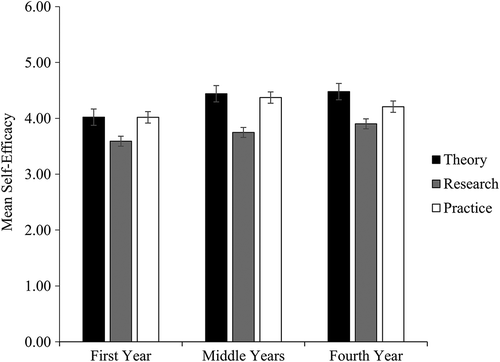

Self‐efficacy beliefs

There was a significant main effect of Domain, F(2, 471) = 59.06, p < .001, ηp 2 = .16, and Year, F(2, 316) = 6.78, p = .001, ηp 2 = .04, with no significant interaction, F(3, 471) = 2.62, p = .051 (see Fig. 3). Students in all years reported significantly greater self‐efficacy for using theory over practice (p = .032) and for practice over research (p < .001). Consistent with the predicted effect of training, first years reported significantly less self‐efficacy when compared to later years (ps ≤ .005), but middle‐ and fourth‐year groups did not differ (p = .999).

DISCUSSION

Students’ expectations of psychology are often unrealistic. The current study sought to investigate what impact inaccurate expectations have on the values and self‐efficacy beliefs of students across the undergraduate years. The perceived values of friends and family and tutors and lecturers were also investigated to examine whether these aligned with the values held by students.

Social influences and subjective task values

In all year levels, students perceived family and friends to value practice over theory and research. Surprisingly, first‐year students reported that they perceived family and friends to hold more positive values towards research than fourth years. This could reflect the added pressure on fourth‐ year students to develop work‐ready skills as they approach the end of their degree. Middle‐ and fourth‐year students’ reported that they perceived academic staff to value theory and research over practice, while first‐year students reported academic staff to value theory, research, and practice equally. This is consistent with first‐year students’ expectation of psychology having a strong focus on helping skills (Goedeke & Gibson, Citation2011).

Students’ interest in theory, research, and practice were consistent with previous findings on students’ expectations (Holmes, Citation2014; Rowley et al., Citation2008). While it was expected that later‐year students would value the domains equally, in all years, research was reported to be less interesting than theory and practice. In fact, first years rated research as more interesting than fourth‐year students. For utility value, students in all year levels rated practice as the most useful domain followed by theory, which was followed by research. This supports the idea that the place and purpose of research training is not well understood by undergraduate students (Goedeke & Gibson, Citation2011; Holmes, Citation2014). These values may be related to task difficulty; first‐year students reported equally high cost value towards theory and research when compared to the practice domain; however, in later years, students considered research to have a higher cost value than both theory and practice.

Despite the perceived cost, students need to perform well in all domains for entry into fourth‐year programmes; therefore students’ attainment value was expected to be equal across domains and year levels. This was not supported; first‐ and middle‐year students reported that research was not as important to develop as theory or practice. While this may be related to the greater perceived cost of research, those in fourth year reported equal attainment value for all domains, despite reporting a high cost value for research. This may reflect the importance of doing well in the fourth‐year research requirements.

Psychology educators have recognised undergraduates’ lack of interest with research and have attempted to improve this through applied examples. However, according to Sizemore and Lewandowski (Citation2011), these strategies have limited success in improving interest and did not improve utility value or performance. However, there is growing support for interventions targeting students’ utility value to enhance interest and performance in tasks involving maths and psychology (Canning & Harackiewicz, Citation2015; Harackiewicz & Hulleman, Citation2010). This has been examined through laboratory‐ and classroom‐based interventions, where students were asked to write a short essay on the utility of a task or technique (Harackiewicz & Hulleman, Citation2010; Hulleman, Godes, Hendricks, & Harackiewicz, Citation2010). This has been shown to be effective for motivating poorly performing students and shows the greatest gains when using self‐generated utility information (Canning & Harackiewicz, Citation2015; Hulleman et al., Citation2010). Thus, utility interventions are an ideal place to start when attempting to improve students’ values towards a domain as they require little additional resources and are easily incorporated into regular assessment activities.

In sum, the hypothesis that students would equally value theory, research, and practice by the fourth year, in accordance with the S‐P model, was not supported for intrinsic, utility, or cost values. Despite students having very little of their programme devoted to practice, they reported greater interest in this domain and find the knowledge and skills associated with this domain to be more useful across a range of settings. To improve students’ achievement motivation in theory and research domains, educators should focus on developing an integrative curriculum through the inclusion of graded simulation tasks that require students to draw from theory, research, and practice (Provost et al., Citation2010). Furthermore, students in the first year reported a greater interest in research than those in later years. It is important that educators capitalise on this by providing hands‐on opportunities to engage with research design and analysis early in the programme and link this material to professional applications across a range of areas.

Self‐efficacy beliefs

Despite undergraduate psychology's strong focus on the science of psychology, students reported greater self‐efficacy in using theory and practice in psychologically literate ways than research. While surprising in an Australian context, where programmes have a strong research focus and little development of students’ self‐efficacy for practice, these findings are consistent with previous research that shows low research self‐efficacy among psychology students (Love, Bahner, Jones, & Nilsson, Citation2007). One concern has been raised that the inclusion of greater practical skills in the undergraduate curriculum could lead students to practice beyond their competence (APS, Citation2012; Provost et al., Citation2010). The current results suggest that students’ self‐efficacy for practice may be inflated; and so, it may be beneficial to provide more experiential learning to enable students to have a more realistic assessment of their own competencies.

This study aimed to provide a snapshot of students’ values and self‐efficacy beliefs towards theory, research, and practice. Currently, students do not appear to be developing psychological literacy incrementally throughout their undergraduate degree as middle‐ and fourth‐year groups did not differ in self‐efficacy for the three domains. However, psychological literacy as an explicit outcome of the undergraduate psychology degree is still in its infancy and may not be emphasised by all higher education providers. The results do suggest that to help develop psychological literacy, the undergraduate curriculum needs to improve the integration of the requisite domains and provide more self‐relevant, pre‐professional skills in research and practice. In addition, programmes should include more practically oriented research training at an undergraduate level. The latter would contribute to the development of self‐efficacy with research that students are currently lacking and help to reduce students’ cost value towards research.

Limitations and future research

There are three methodological issues that should be addressed. First, the theory domain had consistently lower reliability than the research and practice scales. This may be linked to the diversity of the study of psychological theories. While students’ reported no difference in interest and importance of theory and practice, theory was thought to be less useful. This is concerning as theoretical knowledge is the primary focus of the undergraduate degree and underpins the S‐P model and psychological practice (Stoltenberg & Pace, Citation2007). Further exploration of students’ values towards the different theoretical areas in psychology would be beneficial to identify areas for intervention. Second, the current study used a narrow measure of psychological literacy; a more extensive measure is being developed, which may yield different results (Roberts, Heritage, & Gasson, Citation2015). Third, the interpretation of cross‐sectional data can be fraught, especially as the current study examined first‐year students recruited throughout the academic year, and students therefore had different levels of experience with psychology education. It is unclear whether these students form a homogenous sample or if the values students enter with are significantly altered within their first year. A longitudinal study to examine whether students’ values and self‐efficacy beliefs are influenced by training in the first year of study is currently being conducted.

In summary, this study suggests that the undergraduate curriculum may not be effective at providing students with a well‐rounded psychology education. The integration of theory, research, and practice domains in undergraduate courses is recommended to encourage the development of psychological literacy. In addition, utility‐focussed assignments that are self‐relevant and require students’ to generate an argument for the real‐world utility of a topic may have the greatest influence on student values. Such utility interventions may improve students’ cost value, although current research has not addressed this. Further research is needed on implementing utility interventions that are effective for different year levels and topics in psychology.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge and appreciate the support of Australian higher education providers who provided assistance distributing the survey used in this study. The authors declare no conflict of interest arising from the publication of this article.

REFERENCES

- Australian Psychological Society. (2012). Psychology 2020: The 2011–2012 Presidential Initiative on the future of psychological science in Australia. Retrieved from http://www.psychology.org.au/Assets/Files/2012_APS_PIFOPS_WEB.pdf

- Australian Psychology Accreditation Council. (2010). Rules for accreditation and accreditation standards for psychology courses. Retrieved from http://www.psychologycouncil.org.au/Assets/Files/APAC_Rules_for%20_Accreditation_and_Accreditation_Standards_for%20_Psychology_Courses_Ver_10_June_2010.pdf

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self‐efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman.

- Belar, C. , & Perry, N. (1992). The national conference on scientist‐practitioner education and training for the professional practice of psychology. American Psychologist, 47, 71–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.47.1.71

- Bong, M. (2004). Academic motivation in self‐efficacy, task value, achievement goal orientations, and attributional beliefs. The Journal of Educational Research, 97, 287–297. doi:https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.97.6.287-298

- Canning, E. , & Harackiewicz, J. (2015). Teach it, don't preach it: The differential effects of directly‐communicated and self‐generated utility–value information. Motivation Science, 1, 47–71. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000015

- Cranney, J. , Botwood, L. , & Morris, S. (2012). National standards for psychological literacy and global citizenship: Outcomes of undergraduate psychology education. Final report of ALTC/OLT National Teaching Fellowship. Retrieved from http://www.groups.psychology.org.au/Assets/Files/Cranney_NTF_Final_Report_231112_Final_pdf.pdf

- Cranney, J. , & Dunn, D. (2011). The psychologically literate citizen: Foundations and global perspectives. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Cranney, J. , Turnbull, C. , Provost, S. , Martin, F. , Katsikitis, M. , White, F. , … Varcin, K. (2009). Graduate attributes of the 4‐year Australian undergraduate psychology program. Australian Psychologist, 44, 253–262. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00050060903037268

- Eccles, J. , Adler, T. , Futterman, R. , Goff, S. , Kaczala, C. , Meece, J. , & Midgley, C. (1983). Expectancies, values and academic behaviors. In J. T. Spence (Ed.), Achievement and achievement motives. San Francisco, CA: W. H. Freeman.

- Eccles, J. , & Wigfield, A. (1995). In the mind of the actor: The structure of adolescents’ achievement task values and expectancy‐related beliefs. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21, 215–225. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167295213003

- Eccles, J. , & Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 109–132. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135153

- Gaither, G. , & Butler, D. (2005). Skill development in the psychology major: What do undergraduate students expect? College Student Journal, 39, 540–552.

- Goedeke, S. , & Gibson, K. (2011). What do new psychology students know about psychology? Australian Psychologist, 46, 133–139. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9544.2011.00028.x

- Harackiewicz, J. , & Hulleman, C. (2010). The importance of interest: The role of achievement goals and task values in promoting the development of interest. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4, 42–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00207.x

- Holmes, J. (2014). Undergraduate psychology's scientific identity dilemma: Student and instructor interests and attitudes. Teaching of Psychology, 41, 104–109. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628314530339

- Hood, M. , Creed, P. , & Neumann, D. (2012). Using the expectancy value model of motivation to understand the relationship between student attitudes and achievement in statistics. Statistics Education Research Journal, 11, 72–85. Retrieved from iase‐web.org/documents/SERJ/SERJ11(2)_Hood.pdf.

- Hulleman, C. , Durik, A. , Schweigert, S. , & Harackiewicz, J. (2008). Task values, achievement goals, and interest: An integrative analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100, 398–416. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.100.2.398

- Hulleman, C. , Godes, O. , Hendricks, B. , & Harackiewicz, J. (2010). Enhancing interest and performance with a utility value intervention. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102, 880–895. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019506

- Jacobs, J. , & Eccles, J. (2000). Parents, task values, and real‐life achievement‐related choices. In J. M. Harackiewicz (Ed.), Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: The search for optimal motivation and performance (pp. 405–439). Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

- Keppel, G. (1991). Design and analysis: A researcher's handbook (3rd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Love, K. , Bahner, A. , Jones, L. , & Nilsson, J. (2007). An investigation of early research experience and research self‐efficacy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 38, 314–320. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.38.3.314

- Morris, S. , Cranney, J. , Jeong, J. , & Mellish, L. (2013). Developing psychological literacy: Student perceptions of graduate attributes. Australian Journal of Psychology, 65, 54–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12010

- Osborne, J. , & Jones, B. (2011). Identification with academics and motivation to achieve in school: How the structure of the self‐influences academic outcomes. Educational Psychology Review, 23, 131–158. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-011-9151-1

- Parsons, J.E . (1980). Self perceptions, task perceptions and academic choice: Origins and change. ERIC document reproduction service No. ED 186 477. Unpublished final technical report to the National Institute of Education, Washington, DC.

- Pintrich, P. , Smith, D. , Garcia, T. , & Mckeachie, W. (1991). A manual for the use of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ) (Report No. 91‐8‐004). Ann Arbour, MI: The Regents of the University of Michigan.

- Provost, S. , Hannan, G. , Martin, F. , Farrell, G. , Lipp, O. , Terry, D. , … Wilson, P. (2010). Where should the balance be between “scientist” and “practitioner” in Australian undergraduate psychology? Australian Psychologist, 45, 243–248. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00050060903443227

- Raimy, V. (1950). Training in clinical psychology. New York, NY: Prentice Hall.

- Roberts, L. , Heritage, B. , & Gasson, N. (2015). The measurement of psychological literacy: A first approximation. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(105), 1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00105

- Rowley, M. , Hartley, J. , & Larkin, D. (2008). Learning from experience: The expectations and experiences of first‐year undergraduate psychology students. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 32, 399–413. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03098770802538129

- Sizemore, O. , & Lewandowski, G. (2011). Lesson learned: Using clinical examples for teaching research methods. Psychology Learning and Teaching, 10, 25–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.2304/plat.2011.10.1.25

- Stoltenberg, C. , & Pace, T. (2007). The scientist‐practitioner model: Now more than ever. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 37, 195–203. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-007-9054-0

- Wigfield, A. , & Eccles, J. (1992). The development of achievement task values: A theoretical analysis. Developmental Review, 12, 265–310. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0273-2297(92)90011-P

- Wigfield, A. , & Eccles, J. (2000). Expectancy‐value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 61–81. doi:https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1015