Abstract

Background

Mindfulness‐based interventions improve a variety of clinical outcomes. Executive functioning (EF) and emotion dysregulation are among the proposed transdiagnostic mechanisms that such interventions are proposed to target. The aim of the current study was to evaluate the impact of mindfulness meditation training on EF and emotion dysregulation in a sample of female adolescents with elevations in attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms against a waitlist control condition.

Method

This study adopted a mixed 2 (treatment group, waitlist control group) × 2 (pre‐test, post‐test) design. Adolescent females (13–15 years old) exhibiting elevations in ADHD symptoms according to multiple informants were randomly assigned to a mindfulness treatment group (n = 15) or a waitlist control group (n = 15).

Results

Among EF laboratory tasks, planning and inhibition were higher in the treatment group relative to the control group with large effect sizes at post‐treatment. The treatment group also exhibited lower scores in self‐reported emotion dysregulation (total, nonacceptance of emotional responses, and impulse control difficulties) in comparison to the waitlist control group with large effect sizes at post‐treatment. Within group pre‐test and post‐test comparisons indicated improvement on particular facets of EF and emotion dysregulation only for the treatment group.

Conclusions

Mindfulness meditation training improved particular facets of EF and emotion dysregulation in adolescent females with elevations in ADHD symptoms. Treatment development efforts should target clinical populations that exhibit difficulties in these transdiagnostic mechanisms.

What is already known about this topic

Mindfulness meditation is a feasible intervention for adolescents.

Mindfulness meditation is also a feasible intervention for adults diagnosed with attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Mindfulness meditation training is proposed to improve executive functioning (EF) and emotion dysregulation, which may be transdiagnostic mechanisms that account for the growing evidence that mindfulness training improves functioning in a variety of different clinical and vulnerable populations.

What this topic adds

This study assessed the effectiveness of mindfulness in an adolescent female sample with elevated ADHD symptoms.

The current study used a battery of EF tasks to assess multiple facets of EF.

This study conducted in a non‐Western sample to address generalizability of the effects of mindfulness training.

INTRODUCTION

Mindfulness‐based interventions are considered a ‘third wave’ of behaviour therapy (Hayes, Follette, & Linehan, Citation2004) that involve the formal practice of adopting a non‐judgemental attention to one's experience in the present moment (Kabat‐Zinn, Citation1990). Reviews and meta‐analyses demonstrate that mindfulness‐based interventions are effective in improving symptoms of a variety of different mental disorders and psychological health outcomes (e.g., Chiesa & Serretti, Citation2011). Many of these conditions, particularly mental health conditions, are characterised by difficulties in regulating emotions and poor executive functioning (EF). For example, mindfulness training yielded lower relapse rates relative to treatment‐as‐usual and cogntive‐behavioural therapy comparison conditions in a substance use sample (Bowen et al., Citation2014), which is a population with demonstrated difficulties in emotion regulation (Cheetham, Allen, Yücel, & Lubman, Citation2010) and EF (Blume & Marlatt, Citation2009).

Although mindfulness has been proposed to be effective via a variety of different pathways (Hölzel et al., Citation2011), its impact on emotion dysregulation and EF are regularly implicated (Chiesa, Calati, & Serretti, Citation2011; Gratz & Tull, Citation2010). For example, in an adolescent sample administered mindfulness training, improvements were observed in emotional awareness, emotional clarity, and access to emotion regulation strategies in comparison to an active control group (Metz et al., Citation2013). In another study of patients diagnosed with recurrent depression, individuals in the mindfulness‐based treatment group improved in emotional reactivity to stress relative to a waitlist control group (Britton, Shahar, Szepsenwol, & Jacobs, Citation2012). Another study found that 4-days of meditation training (20-minutes per day) improved visuo‐spatial processing, working memory, and EF in comparison to an active control group in a non‐clinical sample (Zeidan, Johnson, Diamond, David, & Goolkasian, Citation2010). Overall, the impact of mindfulness‐based interventions on aspects of emotion dysregulation and EF is important since these are transdiagnostic mechanisms that cut across different forms of psychopathology (Greeson, Garland, & Black, Citation2014).

Attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a disorder characterised by deficits in EF (e.g., sustained attention, inhibition, planning, and working memory) (Barkley, Citation1998; Willcutt, Doyle, Nigg, Faraone, & Pennington, Citation2005) and emotion dysregulation (Barkley, Citation2010). Indeed, EF and emotion dysregulation symptoms are predictive of outcomes in adult samples above and beyond core DSM ADHD symptoms (i.e., inattention and hyperactivity–impulsivity) (Barkley & Fischer, Citation2010). Studies have demonstrated that mindfulness‐based treatment for ADHD improves core ADHD symptoms, though studies need to address transdiagnostic targets such as EF and emotion dyrsegulation (see Mitchell, Zylowska, & Kollins, Citation2015, for a review). In a within subjects study on adults and adolescents with ADHD, self‐reported ADHD, anxiety, and depressive symptoms improved, as well as performance on neuropsychological tasks assessing attention and cognitive inhibition (Zylowska et al., Citation2008); however, without a control group it was difficult to determine if improvement was a function of time. One study demonstrated improvements in emotion dysregulation (self‐reported) and EF (self‐reported, clinician interviews), but not laboratory tasks assessing EF in an ADHD sample randomised to a mindfulness treatment group in comparison to a waitlist control group (Mitchell et al., Citation2013). In contrast, a recent study of adults with ADHD administered the same treatment demonstrated improvement on some EF measures in comparison to a waitlist control group (Bueno et al., Citation2015).

Several other studies evaluated the impact of mindfulness training for children and adolescents with ADHD. For example, in one of these studies with ADHD adolescents, after 8-weeks of mindfulness training, adolescents’ attention and behaviour problems decreased, and EF (parent and tutor reports) improved. In addition, performance on computerised sustained attention tests improved (Van de Weijer‐Bergsma, Formsma, deBruin, & Bogels, Citation2012). In a study with children with ADHD and their parents, improvements in inattention and hyperactivity–impulsivity were observed after treatment and at 8‐week follow‐up as rated by parents (Van der Oord, Bogels, & Peijnenburg, Citation2012). In another study of male adolescents diagnosed with a learning disorder and comorbid ADHD, after 20-weeks of mindfulness meditation training with elements of cognitive behavioural therapy and martial arts, externalizing behaviour (parent rating) improved for the subgroup with ADHD in comparison to the waitlist control subgroup with ADHD. Moreover, in the subgroup of adolescents with elevated symptoms of hyperactivity–impulsivity, improvement in parent‐rated social problems and regulatory skills (a facet of EF) was observed in the treatment group in comparison to the waitlist control group (Haydicky, Wiener, Badali, Milligan, & Ducharme, Citation2012).

A sample with elevations in ADHD symptoms was considered for the current study since ADHD symptoms are normally distributed in the population (e.g., Frazier, Youngstrom, & Naugle, Citation2007), and subclinical symptoms of ADHD in adolescents and young adults are associated with negative outcomes (e.g., De Alwis, Lynskey, Reiersen, & Agrawal, Citation2014; Scahill et al., Citation1999). Furthermore, given the increasing focus of the continuous nature of ADHD symptoms in clinical practice (Lahey & Willcutt, Citation2010), we felt a sample with elevations in symptoms would inform treatment development efforts for those with ADHD, in addition to addressing the overarching aim of this study to examine the impact of a mindfulness intervention on EF and emotion dysregulation. That is, the primary goal of the current study was to examine the impact of mindfulness training in an adolescent sample with elevated ADHD symptoms and expand on the EF laboratory tasks in order to assess additional facets of EF. Furthermore, we also aimed to assess the impact of mindfulness on emotion dysregulation. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess mindfulness in a female adolescent sample with elevated ADHD symptoms. Furthermore, no studies have assessed the impact of mindfulness for clinical or subclinical ADHD in a non‐Western sample—the current study included an Iranian sample. We hypothesised that mindfulness meditation training would result in significantly lower emotion dysregulation and improved EF relative to a waitlist control group.

METHOD

Participants

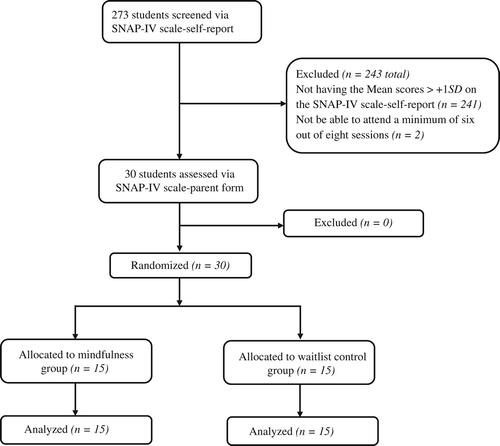

Female adolescents (n = 30) with elevated ADHD symptoms were recruited from a public school (Grades 7 and 8) in Shiraz, Iran. Two‐hundred and seventy‐three students were screened (see Fig. 1 for a summary). Inclusion criteria included: from 13–15 years old, elevated ADHD symptoms (i.e., self‐report and parent report of mean scores on the Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham‐fourth edition (SNAP‐IV) > +1 SD), enrolled in seventh‐ or eighth‐grade classes, expressed interest in treatment, and were able to commit to participate in the first session and attend a minimum of six out of eight sessions. Exclusion criteria included: receiving psycho‐medical treatment; presence of biological diseases which affect EF (e.g., brain damage history, and epilepsy); and any current psychiatric disorders such as psychosis, major depression, personality disorders, or substance abuse. The most common reason for being excluded was not meeting symptom severity criterion on the SNAP‐IV. Consent was obtained from parents and adolescents. This study was approved by the ethics committee for Shiraz University.

Measures

Screening measures

The SNAP‐IV rating scale, self‐report and parent form: The SNAP‐IV rating scale (Swanson et al., Citation2001) includes 18 items which assess DSM‐IV (American Psychiatric Association, Citation1994) ADHD symptoms and covers 9 items for inattention (e.g., often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork or tasks) and 9 items for hyperactivity–impulsivity (e.g., often fidgets with hands or feet or squirms in seat) based on a 0 (not at all) to 3 (very much) rating scale. Swanson et al. (Citation2001) confirmed two factors of this scale (inattention and hyperactivity–impulsivity). These scales have been administered previously in Persian‐speaking samples (Aghaei, Abedi, & Mohammadi, Citation2011; Kiani, Citation2015). Also, factor analysis of SNAP‐IV 18‐item scale (self‐report) in female adolescent students revealed two distinct factors of inattention and hyperactivity–impulsivity in a Persian‐speaking sample (Kiani, Citation2015). In this study, Cronbach's alpha coefficient, Spearman‐Brown coefficient, and Guttman split‐half coefficient, respectively, were 0.81, 0.81, and 0.80 on the inattention subscale and were 0.75, 0.65, and 0.64 on the hyperactivity–impulsivity subscale.

Treatment outcome

Emotion dysregulation

The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) (Gratz & Roemer, Citation2004) is a self‐report scale and includes 36 items on a 5‐point scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). The items cover six subscales: Nonacceptance of Emotional Responses (e.g., ‘When I'm upset, I feel guilty for feeling that way’), Difficulty Engaging in Goal‐Directed Behaviour (e.g., ‘When I'm upset, I have difficulty concentrating’), Impulse Control Difficulties (e.g., ‘When I'm upset, I lose control over my behaviours’), Lack of Emotional Awareness (e.g., ‘I am attentive to my feelings’), Limited Access to Emotion Regulation Strategies (e.g., ‘When I'm upset, I believe that I'll end up feeling very depressed’), and Lack of Emotional Clarity (e.g., ‘I have difficulty making sense out of my feelings’). Higher scores indicate greater difficulty with emotion regulation. The DERS has high internal consistency for the total score (0.93) and all subscales (>0.80), and has also demonstrated convergent validity (Gratz & Roemer, Citation2004). In a Persian‐speaking sample, exploratory factor analysis demonstrated six factors in accordance with the original scale, but three items were eliminated (Khanzadeh, Saidiyan, Hosseinchary, & Edrissi, Citation2012). Also, the Persian version of the scale had good criterion validity with Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (Beck, Epstein, Brown, & Steer, Citation1988) and Beck Depression Inventory‐II (BDI‐II) (Beck, Brown, & Steer, Citation1996), along with acceptable reliability (Cronbach's ∝ between 0.66 and 0.88 and test–retest coefficients between 0.79 and 0.91) (Khanzadeh et al., Citation2012). In the current study, the 33 item version of the DERS was administered and had good internal consistency with Cronbach's alpha ranging from 0.73 to 0.81.

Executive functioning

Continuous performance test (CPT): The CPT assesses continuous attention dysfunction and response inhibition (Corbett, Constantine, Hendren, Rocke, & Ozonoff, Citation2009). In the Persian version of this computerised test, 150 numbers with a given time interval (500-ms) appear and one stimulant (in this test number 6) determines as target stimulant. Participants are told to press the spacebar on a keyboard whenever the number 6 emerges. Result of the test yield three outcome variables assessed in this study: number of correct responses, number of commission errors (response to non‐target stimulus), and number of ommission errors (no response to target stimulus). In this test, commission errors are related to impulsivity and ommission errors to inattention. The reliability of this test by test–retest with 20-days interval was 0.59–0.93; criterion validity which assessed by comparing a normal group and an ADHD group was desirable in a Persian‐speaking sample (Hadianfard, Najarian, Shokrkon, & Mehrabizade Honarmand, Citation2000).

Digit Span (Forward and Backward) subtest and Letter–Number Sequencing subtest of working memory index of Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children‐Fourth Edition (WISC‐IV) (Wechsler, Citation2003a): The Digit Span subtest consists of Digit Span Forward and Digit Span Backward. For Digit Span Forward, the subject is asked to recall a series of numbers that the examiner reads; for Digit Span Backward, the subject is asked to repeat a series of numbers in reverse order. Letter–Number Sequencing requires subjects to recall numbers in ascending order and letters in alphabetical order after listening to a given number and letter sequence (Flanagan & Kaufman, Citation2009). Reliability of Digit Span and Letter–Number Sequencing by split‐half method was 0.87 and 0.90, while test–retest reliability coefficients were 0.83 for both subtests (Wechsler, Citation2003b). In another study, reliability coefficients for Digit Span and Letter–Number Sequencing were >0.71 in a Persian‐speaking sample (Abedi, Sadeghi, & Rabiei, Citation2013).

Stroop Word‐Colour Interference Test: A version similar to the standard stroop word‐colour test (Stroop, Citation1935) was used for assessing inhibition. In the current study, three cards were presented. In the first step, subjects were required to read the black colour words (word card). In the second step, they were asked to name the colour of solid rectangulars (colour card), and finally to name the colours of incongruent colour words (colour‐word card) as fast as possible. This task has been translated for a Persian‐speaking sample (Hosseini Ramaghami, Hadianfard, Taghavi, & Aflakseir, Citation2014). The validity of stroop word‐colour interference test was assessed in many studies by comparing children with ADHD and normal groups (Homack & Riccio, Citation2004). The result of most of these studies showed that children with ADHD exhibited impaired performance in this test in comparison to non‐ADHD children (e.g., Barkley, Grodzinsky, & DuPaul, Citation1992; Boucugnani & Jones, Citation1989).

Tower of London test (TLT; Kovács, Citation2013): This test consists of three pegs of descending height onto which three cubes (red, blue, and green) can be placed. On the first and highest peg, three cubes can be placed, on the second and middle peg, two cubes can be placed, and on the third and shortest peg, only one cube is possible. In each of the 16 different problems, a start position of problem is presented to the subject by the examiner, then the goal position is displayed in a picture, and then the subject is asked to move the cubes one‐by‐one from the start position to reach the goal position the same as the picture displayed. Subjects are also instructed that (a) only one cube can be moved at a time, (b) to move a cube that is under another cube, first, the top cube should be moved, then the under cube can be moved, (c) cubes cannot be placed anywhere else than on a peg, and that (d) the subject should try to solve the problem with the fewest movements possible. The number of needed movements for solving the problems is between 2 and 7 (i.e., the first two problems required two movements, the second two problems required three movements, problems 5 to 8 required four movements, problems 9 to 12 required five movements, problems 13 and 14 required six movements, and the last two problems required seven movements). There are two attempts to solve each of the 16 problems in which subjects are asked to match the goal position. Among the 16 problems, each attempt was scored as correct if the subject made the fewest moves possible. Directions for this task were translated for a Persian‐speaking sample for the current study. Criterion‐related validity of TLT by comparing children with ADHD and non‐ADHD children was desirable (Culbertson & Zillmer, Citation1998).

Procedures

Study involvement included: screening, pre‐test assessment, randomization, intervention or a waiting period, and post‐test assessment. Screening was conducted in an all‐female school for Grades 7–8. Among the 273 students who were screened, 30 were enrolled (see Fig. 1). They were randomly assigned to the treatment group (n = 15) or control group (n = 15) (see Table ). Two weeks before treatment, participants in both groups were assessed for the pre‐test portion of the study. Then the treatment group received the intervention—the waitlist control group did not receive any intervention at this time. One month after the intervention, all participants received a post‐test. Later, the waitlist control group received the same intervention. Before the first treatment session, a meeting was conducted with adolescents in the treatment group to discuss treatment goals, gain a greater understanding of problems that participants faced at school and with peers, and provide a short introduction of mindfulness meditation.

Table 1. Participant baseline characteristics for treatment (n = 15) and Waitlist (n = 15) groups

Treatment

Mindfulness meditation training

The treatment was conducted in groups of seven to eight members in 8‐weekly 1.5‐hour sessions. Content of sessions was based on the steps described in The Mindfulness Prescription for Adult ADHD (Zylowska, Citation2012). Sessions included didactic and experiential training with a therapist leading the session, similar to past mindfulness studies (e.g., Mitchell et al., Citation2013; Zylowska et al., Citation2008). First, in a meeting before beginning the treatment, psychoeducation on ADHD and an introduction to mindfulness were presented. Members of the treatment groups became more familiar with ADHD symptoms and talked about their own ADHD behaviours. Also, some basic directions on how doing the mindfulness practices were provided (e.g., posture). Each session consisted of similar parts including listening to music with mindfulness at the beginning of each session, reviewing the last session practices and homework, introducing the goal of the session and the new practices, and doing the mindfulness meditation practices in the group and after each practice the members shared their own experiences. The either session themes were: Attention and the Five senses; Mindful Breathing; Mindfulness of Sound, Breath, and Body; Mindfulness of Body Sensations and Movement; Mindfulness of Thoughts; Mindfulness of Feelings; Mindful Listening and Speaking; and Mindful Decisions and Actions. The formal practices of each session were related to the theme of that session (see Mitchell et al., Citation2015, for additional details). Group members discussed their experiences and how the practice was applicable in the context of ADHD behaviours. In addition, several mindfulness practices were prescribed for homework at the end of each session, including formal and informal exercises.

Data analysis

SPSS 16.0 was used to analyse the data. One‐way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was conducted to compare the treatment and control groups at post‐test (α = .05). Pre‐test equivalence between groups on all outcome variables was established (available upon request from the corresponding author). Assumptions for ANCOVA were also established, including Levene's test for homogeneity of variances, Shapiro–Wilk to test the assumption of normality, and a ‘pretest X group’ interaction test for homogeneity of regression slopes. Dependent variables were scores of EF and emotion dysregulation at post‐test. The pre‐test score of each of these variables was considered as a covariate and group was a fixed factor. A Bonferroni correction was used for paired t‐tests assessing EF and emotion dysregulation from pre‐test to post‐test for both groups. Following this correction, alpha was set at .005 for EF and .007 for emotion dysregulation. Effect sizes were considered as well (e.g., partial η 2 of .13 was large and .06 was medium) (Cohen, Citation1988).

RESULTS

Executive functions

The results of ANCOVA indicated that the difference between the treatment and control groups in Stroop post‐test was statistically significant (F(1, 27) = 7.58, p = .01) and the effect size was large (partial η 2 = .22), indicating that the adolescents in the treatment group had a significantly higher inhibition than the control group at post‐test. Also, performance on TLT demonstrated that planning of the treatment group was significantly different than the control group (F(1, 27) = 4.88, p = .04) with a large effect size (partial η 2 = .15) (Table ). Between group differences on post‐test performance did not emerge for any of the other EF tasks variables. When within‐group analyses were considered, the treatment group improved in working memory (t = −3.42, p = .004). No other pre‐test and post‐test comparisons within each group reached significance (Table ).

Table 2. Executive functioning post‐treatment comparisons between groups

Table 3. Within group pre‐test to post‐test comparisons for executive functioning

Emotion dysregulation

ANCOVA for DERS total score indicated that the treatment group had lower emotion dysregulation at post‐treatment (F(1, 27) = 6.41, p = .02) relative to the control group with a large effect size (partial η 2 = .19). Subscales demonstrated that the treatment group had a statistically significant lower score in Nonacceptance of Emotion Responses (F(1, 27) = 9.67, p = .004), and Impulse Control Difficulties (F(1,27) = 7.97, p = .009) in comparison to the control group with large effect sizes (partial η 2 = .26 and .23, respectively) (Table ). When within‐group analyses were considered, DERS total scores for the treatment group decreased significantly (t = 3.63, p = .003), but not the waitlist control group. Furthermore, consistent with the ANCOVA analysis, the treatment group yielded statistically significant changes on the Nonacceptance of Emotion Responses (t = 3.54, p = .003) (Table ).

Table 4. Emotion dysregulation post‐treatment comparisons between groups

Table 5. Within group pre‐test to post‐test comparisons for emotion dysregulation

DISCUSSION

The current study evaluated the impact of a group‐based mindfulness meditation training for female Iranian adolescents with elevated ADHD symptoms. The present study is the first to assess the impact of mindfulness training in an adolescent, female, non‐Western sample characterised by multi‐informant elevations in ADHD symptoms. In addition, given that emotion dysregulation and EF are commonly implicated in ADHD and are transdiagnostic mechanisms, our analysis focused on these constructs. Overall, the hypothesis that the treatment group would yield improved performance in EF measures relative to the waitlist control group that was partially supported. ANCOVA analysis indicated that the treatment group exhibited more inhibition on the Stroop task relative to the waitlist control group. ANCOVA analyses indicated that performance of the treatment group on the TLT, a measure of planning, was higher than the waitlist control group. Effect sizes for both outcome variables taking the effects of time (i.e., pre vs. post) and group status (i.e., treatment vs. control) were large. Previous studies have shown that planning ability plays an important role in social functioning and peer relationships in adolescents with ADHD (Chiang & Gau, Citation2014; Clark, Prior, & Kinsella, Citation2002). Our findings involving the Stroop task are consistent with Zylowska et al.’s (Citation2008) findings with Stroop colour‐word task. The results of our study showed that mindfulness meditation training could have a positive effect on planning and inhibition abilities in female adolescents at‐risk for ADHD. Future studies should consider these findings in ADHD samples and other clinical populations characterised by poor EF.

Two other EF facets considered were working memory and sustained attention. No group differences emerged. The null effects for working memory is consistent with previous studies (Mitchell et al., Citation2013; Zylowska et al., Citation2008). For example, in Mitchell et al. (Citation2013), working memory was assessed with both behavioural and neurocognitive assessments: the treatment group improved in working memory via questionnaire, but not on the Digit Span task similar to the one we administered. Our finding regarding sustained attention is also consistent with Mitchell et al. (Citation2013), but in contrast with findings from another recent study in an adult ADHD sample demonstrating improved sustained attention evaluated by an attention task (Bueno et al., Citation2015). Future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to clarify these findings, particularly since paired t‐tests indicated improvement within the treatment group only for Working Memory following Bonferroni correction.

Also, we hypothesised that mindfulness meditation training would have a positive impact on emotion dysregulation. Emotion dysregulation total scores of the treatment group were lower in comparison to the control group at post‐treatment. This finding is consistent with Mitchell et al.’s (Citation2013) study, which is the only other study using an emotion dysregulation measure in an ADHD sample. The analysis of the DERS subscales showed that the treatment group exhibited lower scores in Nonacceptance of Emotion Responses and Impulse Control Difficulties relative to the control group. This is partially consistent with Mitchell et al.’s (Citation2013) study that the treatment group improved in subscales of Impulse Control Difficulties and Limited Access to Emotion Regulation strategies relative to a waitlist control group. These findings demonstrate that mindfulness meditation could help adolescents to experience emotions and respond more adaptively to them. The results of paired t‐tests demonstrated improvement within the treatment group for DERS total score and Nonacceptance of Emotion Responses following Bonferroni correction.

The current study included some limitations that should be considered in the context of interpreting study findings. First, the sample included only female adolescents and is not necessarily generalizable to male adolescents. This design feature of this study could be considered strength since elevations in ADHD symptoms in females are associated with negative functional outcomes (e.g., Cardoos, Loya, & Hinshaw, Citation2013). Future studies should consider gender as a moderator of treatment outcome. Second, adolescents in the current study had elevations in ADHD symptoms, although diagnostic criteria for ADHD were not considered. Future studies should assess the impact of mindfulness meditation training for clinical ADHD adolescents to assess the generalizability of our findings. Relatedly, based on findings from this study, the impact on particular facets of EF and emotion dysregulation should be considered. Third, post‐test evaluations were conducted 1-month after the treatment. Future studies need to evaluate long‐term outcomes. Fourth, in this study, we did not have an active treatment comparison group. In future studies, an active treatment comparison group should be included to differentiate the outcomes caused by treatment from the results due to other factors. Fifth, in addition to one measure of emotion dysregulation, only four measures of EF were administered. Future studies should consider additional assessments measures of these multi‐faceted constructs. Sixth, the sample size of the current study was small, which limits statistical power. Future studies should include larger samples. We need larger studies to examine mindfulness for adolescent females with ADHD (or at‐risk for ADHD) that are well‐powered statistically.

The results of our study demonstrate that mindfulness meditation training could have positive effects on EF and emotion dysregulation in female adolescents with elevations in ADHD symptoms. This is the first study that assessed the impact of mindfulness meditation training in either a female adolescent sample or in a non‐Western sample with elevations in ADHD symptoms. Such findings can inform treatment development efforts for adolescents at‐risk for ADHD or who are diagnosed with ADHD via improvement in EF and emotion dysregulation.

REFERENCES

- Abedi, M. R. , Sadeghi, A. , & Rabiei, M. (2013). Standardization of the Wechsler Inteligence Scale for Children‐IV in Chahar Mahal Va Bakhteyri State. Personality & Individual Differences, 2(3), 138–158.

- Aghaei, A. , Abedi, A. , & Mohammadi, E. (2011). A study of psychometric characteristics of SNAP‐IV rating scale (parent form) in elementary school students in Isfahan. Researches of Cognitive and Behavioral Science, 1(1), 43–58.

- American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM‐IV) (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Barkley, R. A. (1998). Attention‐deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Barkley, R. A. (2010). Deficient emotional self‐regulation: A core component of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of ADHD & Related Disorders, 1(2), 5–37.

- Barkley, R. A. , & Fischer, M. (2010). The unique contribution of emotional impulsiveness to impairment in major life activities in hyperactive children as adults. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(5), 503–513. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2010.01.019

- Barkley, R. A. , Grodzinsky, G. , & Dupaul, G. (1992). Frontal lobe functions in attention deficit disorder with and without hyperactivity: A review and research report. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 20(2), 163–188. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00916547

- Beck, A. T. , Brown, G. , & Steer, R. A. (1996). Beck Depression Inventory II manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation.

- Beck, A. T. , Epstein, N. , Brown, G. , & Steer, R. A. (1988). An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(6), 893–897. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.56.6.893

- Blume, A. W. , & Marlatt, G. A. (2009). The role of executive cognitive functions in changing substance use: What we know and what we need to know. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 37(2), 117–125. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-009-9093-8

- Boucugnani, L. , & Jones, R. (1989). Behaviors analogous to frontal lobe dysfunction in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 4(2), 161–173. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/4.2.161

- Bowen, S. , Witkiewitz, K. , Clifasefi, S. L. , Grow, J. , Chawla, N. , Hsu, S. H. , Larimer, M. E. (2014). Relative efficacy of mindfulness‐based relapse prevention, standard relapse prevention, and treatment as usual for substance use disorders: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Medical Association Psychiatry, 71(5), 547. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4546

- Britton, W. B. , Shahar, B. , Szepsenwol, O. , & Jacobs, W. J. (2012). Mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy improves emotional reactivity to social stress: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Behavior Therapy, 43, 365–380. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2011.08.006

- Bueno, V. F. , Kozasa, E. H. , da Silva, M. A. , Alves, T. M. , Louzã, M. R. , & Pompéia, S. (2015). Mindfulness meditation improves mood, quality of life, and attention in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. BioMed Research International, 2015, 1–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/962857

- Cardoos, S. , Loya, F. , & Hinshaw, S. P. (2013). Adolescent girls’ ADHD symptoms and young adult driving: The role of perceived deviant peer affiliation. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 42(2), 232–242. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2012.759117

- Cheetham, A. , Allen, N. B. , Yücel, M. , & Lubman, D. I. (2010). The role of affective dysregulation in drug addiction. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(6), 621–634. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.005

- Chiang, H. L. , & Gau, S. S. (2014). Impact of executive functions on school and peer functions in youths with ADHD. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 35(5), 963–972. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2014.02.010

- Chiesa, A. , Calati, R. , & Serretti, A. (2011). Does mindfulness training improve cognitive abilities? Asystematic review of neuropsychological findings. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(3), 449–464. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.11.003

- Chiesa, A. , & Serretti, A. (2011). Mindfulness based cognitive therapy for psychiatric disorders: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Psychiatry Research, 187(3), 441–453. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2010.08.011

- Clark, C. , Prior, M. , & Kinsella, G. (2002). The relationship between executive function abilities, adaptive behaviour, and academic achievement in children with externalizing behaviour problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 43(6), 785–796. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00084

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates.

- Corbett, B. A. , Constantine, L. J. , Hendren, R. , Rocke, D. , & Ozonoff, S. (2009). Examining executive functioning in children with autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and typical development. Psychiatry Research, 166(2‐3), 210–222. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2008.02.005

- Culbertson, W. C. , & Zillmer, E. A. (1998). The Tower of LondonDX: A standardized approach to assessing executive functioning in children. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 13(3), 285–301. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/13.3.285

- De alwis, D. , Lynskey, M. T. , Reiersen, A. M. , & Agrawal, A. (2014). Attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder subtypes and substance use and use disorders in NESARC. Addictive Behaviors, 39(8), 1278–1285. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.04.003

- Flanagan, D. P. , & Kaufman, A. S. (2009). Introduction and overview. In A. S. Kaufman & N. L. Kaufman (Eds.), Essentials of WISC‐IV assessment (2nd ed., pp. 2–51). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc..

- Frazier, T. W. , Youngstrom, E. A. , & Naugle, R. I. (2007). The latent structure of attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a clinic referred sample. Neuropsychology, 21(1), 45–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0894-4105.21.1.45

- Gratz, K. L. , & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/b:joba.0000007455.08539.94

- Gratz, K. L. , & Tull, M. T. (2010). Emotion regulation as a mechanism of change in acceptance and mindfulness‐based treatments. In R. A. Baer (Ed.), Assessing mindfulness and acceptance processes in clients: Illuminating the theory and practice of change (pp. 107–133). Oakland, CA: Context Press/New Harbinger Publications.

- Greeson, J. M. , Garland, E. L. , & Black, D. (2014). Mindfulness: A transtherapeutic approach for transdiagnostic mental processes. In A. Ie , C. T. Ngnoumen , & E. J. Langer (Eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of mindfulness (pp. 533–562). Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Hadianfard, H. , Najarian, B. , Shokrkon, H. , & Mehrabizade honarmand, M. (2000). Preparation Persian form of the continuous performance test. Journal of Psychology, 4(4), 388–404.

- Haydicky, J. , Wiener, C. , Badali, P. , Milligan, K. , & Ducharme, J. M. (2012). Evaluation of a mindfulness‐based intervention for adolescents with learning disability and co‐occurring ADHD and anxiety. Mindfulness, 3(2), 151–164. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0089-2

- Hayes, S. C. , Follette, V. M. , & Linehan, M. M. (Eds). (2004). Mindfulness and acceptance: Expanding the cognitive‐behavioral tradition. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Hölzel, B. K. , Lazar, S. W. , Gard, T. , Schuman‐olivier, Z. , Vago, D. R. , & Ott, U. (2011). How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(6), 537–559. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611419671

- Homack, S. , & Riccio, C. A. (2004). A meta‐analysis of the sensitivity and specificity of the Stroop Color and Word Test with children. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 19(6), 725–743. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acn.2003.09.003

- Hosseini ramaghami, N. , Hadianfard, H. , Taghavi, S. M. R. , & Aflakseir, A. (2014). Anxiety and cognitive performance: The effect of induced anxiety conditions in inhibition function of working memory. Journal of Psychological Models and Methods, 5(17), 31–59.

- Kabat‐zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York, NY: Deltacorte Press.

- Khanzadeh, M. , Saidiyan, M. , Hosseinchary, M. , & Edrissi, F. (2012). Factor structure and psychometric properties of difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of Behavioral Siences, 6(1), 87–96.

- Kiani, B. (2015). The impact of therapy based on mindfulness meditation training on executive functioning and emotion dysregulation in subclinical ADHD adolescents. Shiraz, Iran: Shiraz University.

- Kovács, F. (2013). TLT: Manual. Voorhout, Netherlands: Pyramid Productions.

- Lahey, B. B. , & Willcutt, E. G. (2010). Predictive validity of a continuous alternative to nominal subtypes of attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder for DSM‐V. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 39(6), 761–775. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2010.517173

- Metz, S. , Frank, J. , Reibel, D. , Cantrell, T. , Sanders, R. , & Broderick, P. (2013). The effectiveness of the learning to BREATHE program on adolescent emotion regulation. Jefferson Myrna Brind Center of Integration Medicine Faculty Papers, 10(3), 252–272. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15427609.2013.818488

- Mitchell, J. T. , Mcintyre, E. M. , English, J. S. , Dennis, M. F. , Beckham, J. C. , & Kollins, S. H. (2013). A pilot trial of mindfulness meditation training for ADHD in adulthood: Impact on core symptoms, executive functioning, and emotion dysregulation. Journal of Attention Disorders. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054713513328

- Mitchell, J. T. , Zylowska, L. , & Kollins, S. H. (2015). Mindfulness meditation training for attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adulthood: Current empirical support, treatment overview, and future directions. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(2), 172–191. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.10.002

- Scahill, L. , Schwab‐stone, M. , Merikangas, K. R. , Leckman, J. F. , Zhang, H. , & Kasl, S. (1999). Psychosocial and clinical correlates of ADHD in a community sample of school‐age children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(8), 976–984. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199908000-00013

- Stroop, J. R. (1935). Studies of Interference in Serial Verbal Reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 18(6), 643–661. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054651

- Swanson, J. , Schuck, S. , Mann, M. , Carlson, C. , Hartman, K. , Sergeant, J. , Timothy Wigal . (2001). Categorical and dimensional definitions and evaluations of symptoms of ADHD: The SNAP and SWAN ratings scales [ADHD Web Site]. Retrieved from http://www.adhd.net

- Van de weijer‐bergsma, E. , Formsma, A. R. , Debruin, E. I. , & Bogels, S. M. (2012). The effectiveness of mindfulness training on behavioral problems and attentional functioning in adolescents with ADHD. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21(5), 775–787. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-011-9531-7

- Van der oord, S. , Bogels, S. M. , & Peijnenburg, D. (2012). The effectiveness of mindfulness training for children with ADHD and mindful parenting for their parents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21(1), 139–147. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-011-9457-0

- Wechsler, D. (2003a). WISC‐IV: Administration and scoring manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation.

- Wechsler, D. (2003b). WISC‐IV: Technical and interpretation manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation.

- Willcutt, E. G. , Doyle, A. E. , Nigg, J. T. , Faraone, S. V. , & Pennington, B. F. (2005). Validity of the executive function theory of attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A meta‐analytic review. Biological Psychiatry, 57(11), 1336–1346. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.02.006

- Zeidan, F. , Johnson, S. K. , Diamond, B. J. , David, Z. , & Goolkasian, P. (2010). Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: Evidence of brief mental training. Consciousness and Cognition, 19(2), 597–605. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2010.03.014

- Zylowska, L. (2012). The mindfulness prescription for adult ADHD: An 8‐step program for strengthening attention, managing emotions, and achieving your goals. Boston, MA: Shambhala.

- Zylowska, L. , Ackerman, D. L. , Yang, M. H. , Futrell, J. L. , Horton, N. L. , Hale, T. S. , & Smalley, S. L. (2008). Mindfulness meditation training in adults and adolescents with ADHD: A feasibility study. Journal of Attention Disorders, 11(6), 737–746. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054707308502