Abstract

Objective

Previous studies have found that psychological safety is central to effective team functioning and teamwork. Research has also found that psychological safety is dependent on work locus of control (WLOC). Specifically, external WLOC (i.e., perceived lack of personal control over work life) is negatively associated with psychological safety. However, there is limited understanding of underlying mechanisms, such as trust, which may affect this relationship.

Method

Surveys from 131 adult employees from Western Australia were collected from four different organisations.

Results

Results indicated a negative relationship between participants’ expression of external WLOC and psychological safety. Results also indicated that trust significantly moderated the relationship between WLOC and psychological safety.

Conclusion

These findings are valuable for all organisations that wish to increase psychological safety among team members for enhanced productivity and employee wellbeing.

What is known about this topic?

Individuals’ work locus of control (WLOC) can affect psychological safety.

External WLOC has been shown to negatively affect psychological safety.

Psychological safety needs to be encouraged as it is central to effective team functioning, teamwork, and employee wellbeing.

What does this topic add?

In this study, external WLOC was found to be negatively associated with psychological safety among employees from organisations working in Western Australia.

Trust was found to moderate the relationship between external WLOC and psychological safety. This suggests that the level of trust is an important factor between external WLOC and psychological safety.

These findings are valuable for organisations that wish to promote psychological safety and trust among team members, enhancing productivity and employee wellbeing.

Competitive organisations are essentially reliant upon employee cooperation and effective team functioning for successful outcomes (Erdem, Ozen, & Atsan, Citation2003; Kotzé & Steyn, Citation2013). Whilst there is a large body of research, which focused on the influential processes underlying effective team functioning (Kozlowski & Ilgen, Citation2006; Ochieng, Price, Ruan, Egbu, & Moore, Citation2013), there appears to be sparse research on factors that specifically relate to the concept of ‘psychological safety’. Psychological safety refers to the perception that team members can freely share thoughts and knowledge without negative consequences (Edmondson, Citation1999b). Psychological safety is deemed significant because it enhances the success of team performance and cooperative goal interdependence (Leung, Deng, Wang, & Zhou, Citation2015; Nienaber, Holtorf, Leker, & Schewe, Citation2015).

Psychological safety

Psychological safety is formally defined by Kahn as ‘feeling able to show and employ one's self without fear of negative consequences to self‐image, status or career’ (Citation1990, p. 703). Edmondson (Citation1999b) proposes a definition of psychological safety as the shared belief that the work team offers a safe environment for interpersonal risks and information sharing. According to Edmondson (Citation1999b), heightened psychological safety was related to better team learning behaviours and job performances. Furthermore, it has been shown that psychological safety is associated with optimal team functioning, proactive team discussions, engagement in behaviours that facilitated a safe environment, increased feelings of security and employee wellbeing (Kessel, Kratzer, & Schultz, Citation2012; Kozlowski & Ilgen, Citation2006). Therefore, a workplace that encourages psychological safety can lead to heightened cohesiveness and performance among team members (Baer & Frese, Citation2003).

Work locus of control

A factor thought to determine the perception of psychological safety in the workplace is ‘work locus of control (WLOC)’. Generally speaking, ‘locus of control’ refers to the degree to which individuals believe that they have control of the events in their lives (internal locus of control) over external forces beyond their control (external locus of control) (Spector, Sanchez, Siu, Salgado, & Ma, Citation2004). From a conceptual perspective, locus of control refers to a unidimensional continuum, ranging from external to internal (Rotter, Citation1966; Spector, Citation1982). Importantly, locus of control is a continuum because most people are thought to lie somewhere on the continuum between these two extremes. This makes sense when you consider that no one has 100% external or internal locus of control. Consequently, individuals are able to vary their locus of control in different contexts and environments (Hans, Citation2000; Hattie, Marsh, Neill, & Richards, Citation1997).

A number of researchers have questioned the unidimensionality of this concept stating that there is a possibility that the internal and external items of the scale could reflect two to three different psychodynamic constructs (Macan, Trusty, & Trimble, Citation1996). However, other researchers such as Fitzgerald and Clark (Citation2013); Oliver, Jose, and Brough (Citation2006); Spector et al. (Citation2004); Sprung and Jex (Citation2012), and Tillman, Smith, and Tillman (Citation2010) stated that there was insufficient evidence to totally abandon the unidimensional continuum concept of the locus of control. They further noted that factor analysis is insufficient and should not be used as the only tool to decide whether locus of control is unidimensional or multidimensional. Research has also shown that individuals, through training, were able to shift their locus of control from external to internal (Hans, Citation2000; Hattie et al., Citation1997) suggesting that locus of control may reflect a unidimensional continuum, which ranges from external to internal (Rotter, Citation1966; Spector, Citation1982).

When this is extended into the workplace, the term ‘WLOC’ is used specifically to refer to individuals’ beliefs of empowerment within the work domain (Christian, Bradley, Wallace, & Burke, Citation2009). Research has found that employees who express an internal WLOC believe that they are personally responsible for their success (and failure) in the workplace and are empowered to control their environment (Fitzgerald & Clark, Citation2013). In contrast, employees who express external WLOC believe that external forces control the events in their workplace (Loosemore & Lam, Citation2004). For example, employees with an internal WLOC may actively attribute their success to their hard work, whereas employees with an external WLOC may believe their success was due to luck.

An individual's locus of control has a large impact on how much information he or she is willing to contribute to others (Kahya, Citation2015). For instance, Kahya (Citation2015) found that individuals with an internal WLOC were more inclined to express themselves, whilst those with an external WLOC were more likely to remain silent. WLOC has been deemed important in explaining how employees conduct themselves in the work environment, both attitudinally and behaviourally (Ng, Sorensen, & Eby, Citation2006). Spector (Citation1982) found that people showing more internal WLOC often have higher levels of job performance, job satisfaction, and wellbeing than those who express external WLOC.

Research findings have also suggested that WLOC is fundamentally related to self‐evaluations, with internal WLOC individuals showing more favourable core self‐evaluations and higher levels of self‐esteem (Fitzgerald & Clark, Citation2013). Internal WLOC individuals also tend to feel more successful and to place more importance on successful work decisions than external WLOC individuals (Fitzgerald & Clark, Citation2013). The higher core self‐evaluation and self‐esteem of the internal WLOC individuals could debatably be related to higher psychological safety with increased belief to express opinions without fear of negative ramifications to self‐worth. Inversely, it could be debated that the lower core self‐evaluations of external WLOC individuals may lead to less inclination to express personal opinions for fear of negative ramifications. Thus, this may lead external WLOC individuals to have lowered psychological safety (Judge & Bono, Citation2001). Therefore, we propose that:

Hypothesis 1: WLOC (External) is negatively associated with psychological safety.

Trust

It has been shown that certain factors promote psychological safety within a team environment, such as trust between its members (Aranzamendez, James, & Toms, Citation2014). According to McAllister (Citation1995), trust refers to ‘the extent to which a person is confident in, and willing to act on the basis of, the words, actions, and decisions of another’ (McAllister, Citation1995 p. 25).In addition, Mayer, Davis, and Schoorman (Citation1995) believe that trust is about the confidence and willingness of individuals to depend upon another and to be vulnerable to the actions of another. Trust between team members in the workplace has been shown to be related to effective cooperative and risk taking behaviours, such as expressing opinions (Erdem et al., Citation2003), willingness to communicate, sharing knowledge, and participating in team goals (Citation2014b). Hence, trust between team members can be considered to be closely associated or complementary with members’ psychological safety (Edmondson, Citation2003).

Whilst trust and psychological safety are closely aligned psychological states in that they both involve perceptions of risk or vulnerability, making choices to minimise negative personal consequences, and have an impact on positive outcomes for work teams and organisations, these two concepts are nonetheless conceptually and theoretically distinct (Edmondson, Citation2003). According to Edmondson (Citation2003), trust is more concerned with the vulnerability and the expectation that another person's future behaviours will be favourable to oneself, whereas psychological safety concerns an individual's belief that they can comfortably express and communicate their opinions without negative ramifications. Further supporting the distinct constructs, Edmondson (Citation2003) describes three elements of psychological safety that definitively distinguishes it from trust—the ‘object of focus’, ‘timeframe’, and the ‘level of analysis’. The ‘object of focus’ refers to whether the focus is on one's ‘self’ or ‘others’ in the interaction. Trust equates with giving others the benefit of the doubt, hence focus is on ‘others’ and their potential trustworthiness. However, with psychological safety, one questions whether others will give you the benefit of the doubt, therefore the focus is on one's ‘self’ (Edmondson, Citation2003).

Edmondson (Citation2003) also argues that the ‘timeframe’ of potential consequences differentiate trust and psychological safety in that the ramifications of trusting another can affect an individual into the distant future. In contrast, psychological safety is concerned with short‐term interpersonal consequences, even to the point that a person may temporarily negate the longer‐term consequences of not speaking up. The final distinction, according to Edmondson (Citation2003), is that trust relates primarily to a dyadic relationship and psychological safety essentially is experienced within a group or team level.

Despite these differences, Edmondson (Citation1999b) acknowledges the importance of interpersonal trust in the development of team psychological safety, which is thought to lead to team effectiveness (Dirks, Citation2000), positive psychological welfare, job satisfaction, motivation, and commitment to the organisation (Brockner, Siegel, Daly, Tyler, & Martin, Citation1997). Given the benefits of psychological safety and interpersonal trust within the work environment, it is deemed important to investigate this relationship further to consider promotional measures within organisational teams.

The propensity to trust and locus of control dynamic could be explained by considering both constructs as intrinsic traits (Colquitt, Scott, & LePine, Citation2007). Researchers have identified that people expressing an internal locus of control, as opposed to external, were more inclined to cultivate and possess the social skills required to positively manipulate an environment whilst showing consideration to others (Sabatelli, Buck, & Dreyer, Citation1983). In other words, individuals who express an internal locus of control are more likely to trust others compared to individuals who express an external locus of control. Ng et al. (Citation2006) suggest that those expressing internal locus of control demonstrate more proactive behaviours in the maintenance of trusting relationships. Similarly, Lo (Citation2010) found that participants who expressed an internal locus of control were more trusting and more likely to share personal information over a social network site than participants who showed an external locus of control. These studies provided some explanations as to why individuals with internal locus of control have higher levels of trust than individuals with external locus of control.

Despite these empirical studies, there is still limited understanding about the role of trust and how it may moderate the relationship between employees’ WLOC and psychological safety. Hence, we proposed that:

Hypothesis 2: Trust will moderate the relationship between WLOC and psychological safety such that higher trust levels as opposed to lower trust levels will increase the positive relationship between internal WLOC and psychological safety.

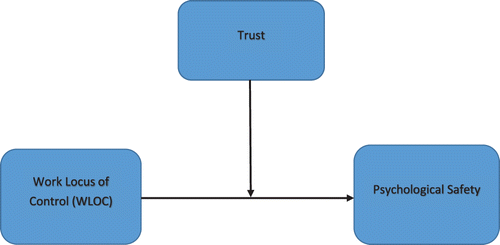

Please refer to Fig. 1 for the study model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Research design

This study consists of a cross‐sectional correlational design, which considers trust as a moderator, WLOC as a predictor variable, and psychological safety as the outcome variable.

Participants

Participants were 131 adult workers employed in organisations within Western Australia. There were 104 males (mean age = 40.46, standard deviation (SD) = 10.17) and 27 females (mean age = 39.79, SD = 11.54). Participants were recruited from construction companies specialising in mining, oil, and gas. The rationale for recruiting workers from construction companies that specialise in mining, oil, and gas was because these industries are considered a ‘high safety risk’, with both trust and psychological safety considered vital to reduce incidents and fatalities (Conchie, Donald, & Taylor, Citation2006).

Materials and data analysis

Materials required for this study included an initial letter of introduction and request of organisation participation. These documentations were sent to the Manager of Human Resources. An introduction letter to participants was employed to explain the aims of the study/survey, to give assurance of confidentiality, and to clarify procurement of informed consent (through full completion of the survey questionnaire). Data analysis was conducted using Hayes's PROCESS moderation regression programme via IBM SPSS statistical package (Hayes, Citation2013). The moderation regression (Model 1) utilised a ‘bias corrected bootstrap’ method of 1,000 replications where variables were mean centred as part of Hayes's PROCESS moderation analysis.

Measures

Work locus of control

The degree of WLOC was assessed using Spector's (Citation1988) domain‐specific ‘Work Locus of Control Scale’. The WLOC is measured on a 6‐point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicated higher levels of external WLOC. Two example items included, ‘On most jobs, people can pretty much accomplish whatever they set out to accomplish’ and ‘Promotions are usually a matter of good fortune’. This scale has shown good internal consistency with a Cronbach's α ranging from .80 to .85 (Spector, Citation2004). Cronbach's α in this study showed good reliability at .83.

Psychological safety

Six questions specifically measuring the construct of team psychological safety were used from the Team Learning Climate subsection of Edmondson's (Citation1999a) ‘Team Learning and Psychological Safety Survey’. According to Edmondson (Citation1999b), team psychological safety refers to the extent to which team members view the social climate as being conducive to interpersonal risk. This construct is measured on a 6‐point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicated greater psychological safety. An example question is ‘When someone makes a mistake in this team, it is often held against him or her’. Evaluations of this scale have previously showed high internal reliability with a Cronbach's α of .78 to .82 (Carmeli, Brueller, & Dutton, Citation2009; Edmondson, Citation1999b). The Cronbach's α in this study was at an acceptable level of .66, however, upon inter‐item correlation analysis, reliability was improved with the removal of Item S4, increasing Cronbach's α to .78.

Trust

Trust was measured using five items from Currall and Judge's (Citation1995) ‘Boundary Role Person Trust Measure’ to specifically capture the trust construct on information sharing within the team environment, and three items from Citation2014a ‘Trust Measure’, to explicitly address perceptions of team members’ consideration, friendliness, and reliability. The phrase ‘counterpart boundary role person’ from Currall and Judge's (Citation1995) measure was modified and replaced with ‘my work team’ to help facilitate participants’ evaluation of trust towards team members as opposed to a certain individual. The items were measured on a 6‐point Likert scale, which asked participants to rate their response in terms of what they would do in dealing with their work team, ranging from 1 (extremely unlikely) to 6 (extremely likely). An example of a statement is, ‘Think carefully before telling my work team my opinions’. Inter‐item correlation for the ‘Boundary Role Person Trust Measure’ was improved from α .67 to α .72 upon removal of Items T1 and T6. Summing the two scales to represent total trust was deemed viable as both measures collectively embraced the researchers’ desired concept of trust (i.e., participants’ opinions about their willingness to share information and their perceptions of team members’ trustworthiness). Moreover, combining the two scales proved psychometrically advantageous and increased the Cronbach's α from .67 to α .72.

Procedure

Eight organisations working within Australia were sent a letter of introduction and invitation via email to participate in the research project. Four organisations accepted the invitation to participate. At the scheduled time onsite, the first researcher handed out the research information letter to participants and clarified questions from participants. Participants were notified about the purpose of the study, the voluntary nature of the study, and were given assurance that participants’ confidentiality and anonymity would be kept. The survey questionnaire was then distributed to the volunteer participants, with standardised instructions from the researcher. Participants were reminded to answer all questions honestly and that there was no right or wrong answer. Demographic information such as age, gender, education, and work industry was also collected. The completed questionnaires were then placed in sealed envelopes and collected. The total data collection took 10 weeks from initial invitation to final data collection.

RESULTS

The data were assessed for normality and outliers. Normality could not be assumed for the outcome variable ‘psychological safety’ or the predictor variable ‘WLOC’. Whilst there were seven outliers across the three variables, it was decided not to alter the outliers and instead use bootstrapping in the analysis to increase the robustness of violations to assumptions and outliers (Field, Citation2013). There was one ‘extreme’ outlier on the psychological safety measure from participant number 121. In this one case, Winsorising was utilised whereby the extreme score was replaced by a score the same as the next highest score that was not an outlier (Field, Citation2013). Multivariate outliers were assessed using Mahalanobis distance and Cook's distance. Two participants showed Mahalanobis distance above the critical chi‐square value χ2 for df = 2 (at α = .001) of 13.816. However, both Cook's distance was acceptable at less than 1, showing that their inclusion and hence influence to the model was minimal, therefore they were not excluded in the analysis. Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix are presented in Table . Finally, a factor analysis was conducted on the relevant scales of trust and psychological safety to ensure that they are relatively distinct concepts.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlations between the measures

To test for Hypothesis 1, a bivariate correlation was carried out. Assumptions of normality for the psychological safety variable were violated W(130) = .96, p = .002 and WLOC, W(130) = .98, p = .048, therefore the Spearman's rho test was used, which indicated a significant negative relationship among individuals with external WLOC (rˢ = −.461, p ˂ .001) and psychological safety. This indicated that as scores increased towards external WLOC, psychological safety decreased in the work place. Finding thus supported Hypothesis 1.

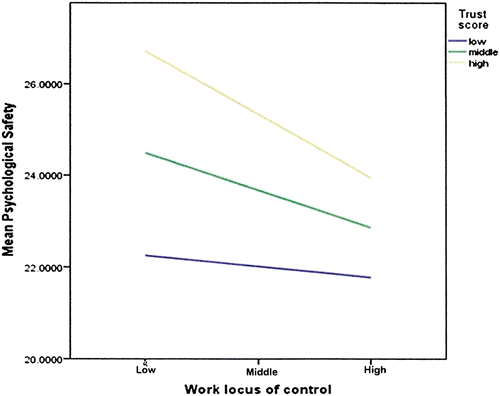

The analysis for moderation effects of trust on the relationship between WLOC and psychological safety revealed a significant moderating effect. The overall model's significance was F(3, 127) = 17.02, p = ˂.001, R 2 = .36. Trust was a significant contributor to psychological safety b = .30, t(127) = 4.16, p = <.001, 95% confidence interval (CI) [0.16, .45], showing that for every one unit increase in trust, we get a .30 increase in psychological safety. Results also showed that for every one unit increase in trust, we get a − .09 reduction in external WLOC b = −.09, t(127) = −2.29, p = .02, 95% CI [−.16, −.01].

The interaction between WLOC and trust was also significant b = −.01, t(127) = −2.05, p = .04, 95% CI [−.0.02, −0.01] indicating a moderating effect of trust on the relationship between WLOC and psychological safety. In other words, trust will moderate the relationship between WLOC and psychological safety such that higher trust levels, as opposed to lower trust levels, will increase the positive relationship between internal WLOC and psychological safety. For a visual interpretation of the moderation effect of trust on the relationship between WLOC and psychological safety, please refer to Fig. 2.

DISCUSSION

The overall aim of this study was to investigate the factors that might affect psychological safety in organisational work teams. The results indicated that individuals possessing higher external WLOC tend to experience lower psychological safety. This finding aligns with previous research suggesting that individuals with external WLOC tend to communicate less effectively with their colleagues, have increased negative work outcomes, and are more dissatisfied in their job (Ng et al., Citation2006; Tillman et al., Citation2010).In addition, in a study conducted by Owolabi (Citation2013), employees who were inclined to be internal in control tended to perceive their work environment as more supportive than employees who were external in their locus of control.

Generally, locus of control has been viewed as an intrinsic trait with certain predictable characteristics (Avtgis & Brogan, Citation1999). One of these characteristics is self‐esteem. Specifically, individuals with internal WLOC tend to show higher self‐esteem than those with external WLOC (Fitzgerald & Clark, Citation2013). Therefore, internal WLOC orientation encourages proactive behaviours and open communications leading to higher perceived psychological safety. In contrast, individuals with an external WLOC tend to express lower self‐esteem leading to a lowered inclination to express personal opinions for fear of negative ramifications. Consequently, individuals with an external WLOC will tend to experience lowered psychological safety than those with internal WLOC (Judge & Bono, Citation2001).

Importantly, the results indicated that trust was a significant moderator between WLOC and psychological safety in the workplace. The moderating effect of trust on the relationship between WLOC and psychological safety was considered theoretically viable with empirical evidence suggesting that those with higher intrinsic trust were more likely to hold internal WLOC and to experience higher self‐esteem, greater involvement in proactive behaviours and communications, all of which ultimately led to increased psychological safety. In contrast, those with lower levels of trust were more inclined towards an external WLOC which reduced proactive behaviours and communications and lead to lowered psychological safety perceptions.

Considering Spector's (Citation1982) belief that WLOC orientation can change depending on experiences, the findings from this research could indicate that if organisations focus on trust building exercises, WLOC orientation could improve towards internal WLOC with consequential enhanced psychological safety and improved team interactions and outcomes. This finding supports Roussin and Webber's (Citation2012) study which found that a disposition to trust is positively related to how individuals judge the trustworthiness of new co‐workers. It is plausible to suggest that highly trusting individuals may be better able to express themselves and to develop stronger interpersonal relationships with their colleagues. In doing so, they experience higher levels of psychological safety in their workplace than individuals who are mistrustful. Similarly, Ferres, Connell, and Travaglione (Citation2004) found that promoting trust between co‐workers served to increase social capital, organisational learning behaviours, knowledge sharing between team members, innovation and consequently, improved the overall psychological safety experiences of all employees.

Limitations

A limitation in this study is the ambiguity of participants ‘work team’ in their respective organisations. Although participants were recruited from within construction companies that specialised in the mining, oil, and gas industry, we were unable to fully ascertain if all the participants came from the same team or they were from different work teams. Future researchers may wish to refine this recruitment procedure. So, whilst the general term ‘work team’ was used in the questionnaire scales, thorough insight into the individual's specific work team configurations and dynamics was not identified and consequently, clarification of work team parameters was inaccessible. Therefore, findings may not be applicable to all team configurations and dynamics.

Another limitation has to do with common method bias (CMB); that our finding may lack validity due to CMB. Although some researchers concluded that CMB posed a significant threat to validity (Cote & Buckley, Citation1987; Doty & Glick, Citation1998), other researchers concluded that the effects of CMB may be relatively small (Crampton & Wagner, Citation1994; Spector, Citation1987). In our study, we have taken a number of steps to guard against CMB. For instance, we assured participants that the responses they provided will be kept anonymous and confidential. We also instructed participants to answer all the questions as honestly as possible as we were only interested in their opinions. We also conducted Harman single factor to test for CMB. Our result indicated that the first (largest) factor did not account for the majority of the variance (25.62% to less than 50%) suggesting that CMB is not a primary concern in our study.

The current study used two measures: Currall and Judge's (Citation1995) ‘Boundary Role Person Trust Measure’ and Citation2014a ‘Trust Measure’ to help capture participants’ opinions about their willingness to share information and their perceptions of team members’ trustworthiness. Although the majority of the trust items loaded onto one factor, some of the remaining items loaded onto second and third factors, suggesting the need to refine these items. Despite this, the combined scales proved psychometrically advantageous as the correlations between variables improved. In addition, the Cronbach's α for the combined scale also improved from .67 to α .72. Nevertheless, future study should consider either adopting a trust measure which covers participants’ willingness to share information and their perceptions of team members’ trustworthiness or develop a scale that will cover the above trust issues.

Another concern for the overall generalisability of the findings is the consideration of the demographic data. The sample indicates that 69.5% of participants held a position in the managerial or engineering fields whereby it is conceivable that contribution to team discussion and knowledge sharing is an expectation vital to their job description and hence these participants would perhaps perceive higher psychological safety to express themselves without negative ramifications. Similarly, research has found that individuals with internal WLOC have higher self‐esteem than those expressing external WLOC (Avtgis & Brogan, Citation1999; Fitzgerald & Clark, Citation2013). As a result of this, these individuals tend to successfully engage in proactive behaviours and open communications leading to higher psychological safety. More research needs to be conducted to investigate the relationship between self‐esteem, locus of control, and psychological safety. This is important because a number of previous studies have found that individuals from East Asian countries tend to have lower self‐esteem than individuals from Western countries (Cai, Brown, Deng, & Oakes, Citation2007; Schmitt & Allik, Citation2005), which may contribute to heightened external WLOC among Asian workers. Therefore, future research should consider investigating self‐esteem, WLOC, and psychological safety among culturally diverse work groups so that cultural misinterpretation among culturally diverse team members could be reduced.

CONCLUSION

The overall aim of this study was to investigate factors that may affect WLOC and psychological safety among team members. Trust is one such factor, which has been shown to be an important catalyst for increasing psychological safety. Accordingly, developing trust not only improves psychological safety within the workplace but also deemed highly beneficial for both employee wellbeing and organisational interests, particularly when team collaboration is essential for outcomes (Ferres et al., Citation2004; McAllister, Citation1995).

Results in our study indicated that trust significantly moderated the relationship between WLOC orientation and psychological safety. This is an exciting finding especially for organisations that are struggling with interventions to increase cohesiveness within work groups. By focusing on strategies that improve trust across all team members, psychological safety consequently could be improved. This strategy is particularly pertinent in the current climate of expanding global organisations that desire that competitive edge.

This research also contributes to organisational psychology and the understandings of employee interactions in the team workplace. Investigating this theoretical dynamic has addressed a gap in the current organisational literature, specifically regarding the relationship between WLOC and psychological safety and a factor that affects this relationship. Awareness of this factor, specifically that trust between team members is highly valuable for increasing psychological safety, should lead all organisations to implement interventions assisting the expansion of trust in the workplace for optimal employee, team, and organisational outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The researchers would like to acknowledge the effort and support of John Triplett, whose considerable assistance with data collection and proof reading were of tremendous help to the study.

Notes

1. A factor analysis was conducted via a principal axis factoring analysis utilising the Promax rotation method. Items S4, T1, and T6 were removed due to low inter‐item correlations as per reviewer's suggestion to increase reliability of the scales. Three factors were isolated with Eigenvalues exceeding 1. All items on the psychological safety scale loaded highly onto Factor 1. While some of the trust items loaded onto Factor 1, most of them loaded onto Factors 2 and 3. This result provided evidence that the two scales (psychological safety and trust) were relatively distinct.

REFERENCES

- Akgün, A. E. , Lynn, G. S. , Keskin, H. , & Dogan, D. (2014a). Trust measure [Database record]. Retrieved from PsycTESTS. https://doi.org/10.1037/t33431‐000

- Akgün, A. E. , Lynn, G. S. , Keskin, H. , & Dogan, D. (2014b). Team learning in IT implementation projects: Antecedents and consequences. International Journal of Information Management, 34(1), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2013.09.007

- Aranzamendez, G. , James, D. , & Toms, R. (2014). Finding antecedents of psychological safety: A step toward quality improvement. Nursing Forum, 50(3), 171–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.1208

- Avtgis, T. A. , & Brogan, S. M. (1999). Quality of organisational relationships as a function of work locus of control. Communication Research Reports, 16(1), 65–71.

- Baer, M. , & Frese, M. (2003). Innovation is not enough: Climate for initiative and psychological safety, process innovations, and firm performance. Journal of Organisational Behaviour, 24, 45–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.179

- Brockner, J. , Siegel, P. A. , Daly, J. , Tyler, T. , & Martin, C. (1997). When trust matters: The moderating effect of outcome favorability. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42(3), 558–583. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393738

- Cai, H. J. , Brown, J. D. , Deng, C. P. , & Oakes, M. A. (2007). Self‐esteem and culture: Differences in cognitive self‐evaluations or affective self‐regard? Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 10(3), 162–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467‐839X.2007.00222.x

- Carmeli, A. , Brueller, D. , & Dutton, J. E. (2009). Learning behaviours in the workplace: The role of high‐quality interpersonal relationships and psychological safety. Systems Research and Behavioural Science, 26, 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.932

- Christian, M. S. , Bradley, J. C. , Wallace, J. C. , & Burke, M. J. (2009). Workplace safety: A meta‐analysis of the roles of person and situational factors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 1103–1127. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016172

- Colquitt, J. A. , Scott, B. A. , & Lepine, J. A. (2007). Trust, trustworthiness, and trust propensity: A meta‐analytic test of their unique relationship with risk taking and job performance. American Psychological Association, 92(4), 909–927.

- Conchie, S. M. , Donald, I. J. , & Taylor, P. J. (2006). Trust: Missing piece(s) in the safety puzzle. Risk Analysis, 26(5), 1097–1407. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539‐6924.2006.00818.x

- Cote, J. A. , & Buckley, M. R. (1987). Estimating trait, method, and error variance: Generalising across 70 construct validation studies. Journal of Marketing Research, 24(3), 315–318.

- Crampton, S. , & Wagner, J. (1994). Percept–percept inflation in micro‐organisational research: An investigation of prevalence and effect. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(1), 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021‐9010.79.1.67

- Currall, S. C. , & Judge, T. A. (1995). Boundary Role Person Trust Measure [Database record]. Retrieved from PsycTESTS. https://doi.org/10.1037/t19686‐000

- Dirks, K. T. (2000). Trust in leadership and team performance: Evidence from NCAA basketball. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 1004–1012. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021‐90I0.85.6.1004

- Doty, D. H. , & Glick, W. H. (1998). Common methods bias: Does common methods variance really bias results? Organisational Research Methods, 1(4), 374–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442819814002

- Edmondson, A. (1999a). Team Learning and Psychological Safety Survey [Database record]. Retrieved from Measurement Instrument Database for the Social Sciences. https://doi.org/10.13072/midss.111

- Edmondson, A. (1999b). Psychological safety and learning behaviour in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999

- Edmondson, A. (2003). Psychological safety, trust and learning in organisations: A group‐ level lens (Unpublished doctoral dissertation or master's thesis). Harvard Business School, Boston, MA.

- Erdem, F. , Ozen, J. , & Atsan, N. (2003). The relationship between trust and team performance. Work Study, 52(6/7), 337–340.

- Ferres, N. , Connell, J. , & Travaglione, A. (2004). Co‐worker trust as a social catalyst for constructive employee attitudes. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 19(6), 608–622. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940410551516

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (4th ed.). London, England: Sage.

- Fitzgerald, C. S. , & Clark, S. (2013). Work locus of control and perceptions of practice. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 7(1), 59–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548732.2012

- Hans, T. (2000). A meta‐analysis of the effects of adventure programming on locus of control. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 30(1), 33–60.

- Hattie, J. A. , Marsh, H. W. , Neill, J. T. , & Richards, G. E. (1997). Adventure education and outward bound: Out‐of‐class experiences that have a lasting effect. Review of Educational Research, 67(1), 43–87.

- Hayes, A. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression‐based approach. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Judge, T. A. , & Bono, J. E. (2001). Relationship of core self‐evaluations traits – Self‐esteem, generalised self‐efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability – With job satisfaction and job performance: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021‐9010.86.1.80

- Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724.

- Kahya, C. (2015). The relationship between locus of control and organisational silence: A study on the Turkish academicians. IIB International Refereed Academic Social Sciences Journal, 6(19), 1–18.

- Kessel, M. , Kratzer, J. , & Schultz, C. (2012). Psychological safety, knowledge sharing and creative performance in healthcare teams. Creativity and Innovation Management, 21(2), 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467‐8691.2012.00635.x

- Kotzé, M. , & Steyn, L. (2013). The role of psychological factors in workplace safety. Ergonomics, 56(12), 1928–1939. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139.2013.851282

- Kozlowski, S. W. J. , & Ilgen, D. R. (2006). Enhancing the effectiveness of work groups and teams. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 7(3), 77–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601110390835

- Leung, K. , Deng, H. , Wang, J. , & Zhou, F. (2015). Beyond risk‐taking: Effects of psychological safety on cooperative goal interdependence and prosocial behaviour. Group and Organisational Management, 40(1), 88–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601114564012

- Lo, J. (2010, August). Privacy concern, locus of control and salience in a trust‐risk model of information disclosure on social networking sites. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the Sixteenth Americas Conference on Information Systems, Peru.

- Loosemore, M. , & Lam, A. (2004). The locus of control: A determinant of opportunistic behaviour in construction health and safety. Construction Management and Economics, 22(4), 385–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144619042000239997

- Macan, T. H. , Trusty, M. L. , & Trimble, S. K. (1996). Spector's work locus of control scale: Dimensionality and validity evidence. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 56(2), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164496056002016

- Mayer, R. C. , Davis, J. H. , & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integration model of organisational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734.

- Mcallister, D. J. (1995). Affect‐ and cognition‐based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organisations. Academy of Management Journal, 38(1), 24–59.

- Ng, T. W. H. , Sorensen, K. L. , & Eby, L. T. (2006). Locus of control at work: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Organisational Behaviour, 27(8), 1057–1087. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.416

- Nienaber, A. I. , Holtorf, V. , Leker, J. , & Schewe, G. (2015). A climate of psychological safety enhances the success of front end teams. International Journal of Innovation Management, 19(2), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1363919615500279

- Ochieng, E. G. , Price, A. D. F. , Ruan, X. , Egbu, C. O. , & Moore, D. (2013). The effect of cross‐cultural uncertainty and complexity within multicultural construction teams. Engineering Construction and Architectural Management, 20(3), 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1108/09699981311324023

- Oliver, J. E. , Jose, P. E. , & Brough, P. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis of the work locus of control scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(5), 835–851. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164405285544

- Owolabi, A. B. (2013). Influence of work locus of control and perceived support on employees’ work attitude and organisationally beneficial behaviour. Nigerian Journal of Applied Behavioural Sciences, 1(1), 11–20.

- Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalisutilied expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs, 80(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0092976

- Roussin, C. J. , & Webber, S. S. (2012). Impact of organisational identification and psychological safety on initial perceptions of co‐worker trustworthiness. Journal of Business and Psychology, 27(3), 317–329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869‐011‐9245‐2

- Sabatelli, R. M. , Buck, R. , & Dreyer, A. (1983). Locus of control, interpersonal trust and nonverbal communication accuracy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(2), 399–409.

- Schmitt, D. P. , & Allik, J. (2005). Simultaneous administration of the Rosenberg Self‐Esteem Scale in 53 nations: Exploring the universal and culture‐specific features of global self‐esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(4), 623–642. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022‐3514.89.4.623

- Spector, P. E. (1982). Behaviour in organisations as a function of employee's locus of control. Psychological Bulletin, 91, 482–497.

- Spector, P. E. (1987). Method variance as an artifact in self‐reported affect and perceptions at work: Myth or significant problem? Journal of Applied Psychology, 72(3), 438–443.

- Spector, P. E. (1988). ‘Work locus of control scale – 8’. Retrieved from http://shell.cas.usf.edu/~pspector/scales/wlcover.html

- Spector, P.E. (2004). Overview of the Work Locus of Control Scale. Retrieved from http://shell.cas.usf.edu/

- Spector, P. E. , Sanchez, J. I. , Siu, O. L. , Salgado, J. , & Ma, J. (2004). Eastern versus western control beliefs at work: An investigation of secondary control, socioinstrumental control, and work locus of control in China and the US. Applied Psychology. An International Review, 53(1), 38–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464‐0597.2004.00160.x

- Sprung, J. M. , & Jex, S. M. (2012). Work locus of control as a moderator of the relationship between work stressors and counterproductive work behaviour. International Journal of Stress Management, 19(4), 272–291. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030320

- Tillman, C. J. , Smith, F. A. , & Tillman, W. R. (2010). Work locus of control and the multidimensionality of job satisfaction. Journal of Organisational Culture, Communications and Conflict, 14(2), 107–125.