Abstract

Objective

Postgraduate psychology students must develop three generic capabilities: theory, research, and communication. This is critical to strengthen the link between science and practice. The current study explored the impact of students’ postgraduate program on task values and self‐efficacy beliefs using an expectancy‐value perspective.

Method

Two hundred and thirty‐seven postgraduate psychology students (195 females, Mage = 30.98, standard deviation = 8.34) completed a survey investigating student values and expectations. Students were enrolled in a Master of Psychology (n = 90), research‐only PhD (n = 72), or professional doctorate/Masters with PhD (n = 75).

Results

A series of 3 (Domain) × 3 (Program) mixed factorial analysis of variances were conducted to explore postgraduates’ social influences, task values, and self‐efficacy beliefs towards theory, research, and communication. Coursework students perceived peers to value communication skills significantly more than research, while research‐only students perceived peers to value theory, research, and communication equally. Postgraduate students in all programs reported consistently lower task values and self‐efficacy beliefs towards the research domain.

Conclusion

Australian universities and professional organisations are encouraged to support the development of practice–research networks to facilitate greater collaboration and stronger links between future psychological scientists and practitioners.

What is already known about this topic?

Expectancy‐value theory is a useful model for explaining achievement motivation that can be applied to different learning domains.

Postgraduate psychology training currently advocates evidence‐based practice within the current model of training, which requires positive attitudes towards theory, research, and communication domains.

The research training environment in Australia is a key area for reform with demand for more skills training during a research degree; theoretical knowledge, advanced research skills, and communication and interpersonal skills were identified by stakeholders as the most important areas for development.

What this topic adds?

Previous research had not simultaneously investigated differences between psychology students undertaking different postgraduate degrees.

The subjective norms of postgraduate psychology students were investigated, including students' perceptions of the value placed on theory, research, and communication by friends and family, peers, and academic staff.

Key differences emerged between the task values that the various groups of postgraduate students hold towards the three domains (theory, research, and communication).

In Australia, students’ choice of postgraduate psychology program is an area that receives some recognition, but little attention, in learning and teaching research. There are a range of postgraduate study options for psychology students to consider. At the Masters level, students have two options: one‐year of postgraduate study followed by a one‐year internship (5 + 1 model) or a two‐year professional Masters in an area of practice (e.g., organisational, clinical psychology). At the doctoral level, students have three options: they can complete a professional doctorate, a higher degree by research, typically a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), or the two‐year Masters combined with a Doctor of Philosophy (Australian Psychology Accreditation Council [APAC], Citation2010). Despite the range of programs and practice areas, most research on postgraduate students has focussed on the Masters and Doctoral programs in clinical psychology (Scott, Pachana, & Sofronoff, Citation2011). However, for all students undertaking postgraduate psychology coursework, their program is grounded in the scientist–practitioner model of training (APAC, Citation2010).

Despite the scientist–practitioner emphasis in Australian psychology education, there is evidence to suggest a decline in research interest occurs among clinical psychology students during postgraduate training. Horn et al. (Citation2007) examined students’ interests using the scientist‐practitioner inventory (Zachar & Leong, Citation1991) at the beginning and end of their coursework program. Interest in scientist activities decreased (e.g., reviewing the literature on an issue in psychology), while interest in practitioner activities remained stable (e.g., consulting with other psychologists about a particular client's concerns). Therefore, it is important that the emphasis on practitioner skills in Australian postgraduate psychology education does not simultaneously reduce students’ value in the scientific approach necessary for functioning as a scientist–practitioner (Jones, Citation2008).

The scientist–practitioner model is typically translated into postgraduate training through evidence‐based practice (EBP; Australian Psychological Society, Citation2012). EBP posits that professional decision‐making should be based on best available research evidence, client preferences, and professional expertise (Briner & Rousseau, Citation2011; Spring, Citation2007). EBP aims to overcome biases and errors in professional judgement by incorporating evidence in the context of relevant theories or processes (Bell & Mellor, Citation2009). Further, the best point to improve adherence to EBP is at the postgraduate level (Spring, Citation2007). Ideally, postgraduate students should develop three generic capabilities: theory, research, and communication (see Table ). These skills are also critical for psychology students in postgraduate research pathways, as these graduates will progress to become psychological scientists, researchers, and educators (Lodge, Citation2015). However, research‐only PhD students often do not have the same access to skills training (especially communication skills; McGagh et al., Citation2016).

Table 1. Definitions of theory, research, and communication for postgraduate psychology students

THE TRAINING OF PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENTISTS

Research on PhD students has generally focussed on students across all disciplines (Edwards, Radloff, & Coates, Citation2009), or those concurrently enrolled in professional psychology programs (e.g., Graham & Kim, Citation2011). There has yet to be a systematic exploration of students’ motivation and self‐efficacy beliefs across different Australian psychology pathways. Although research has rarely focussed on this group, graduates of research‐only psychology programs remain important members of the psychological community. It is important to ensure PhD graduates are adequately prepared for employment, in terms of their ability to apply theoretical knowledge, research skills, and to communicate with stakeholders.

Unlike the U.S. system, Australian research training does not include formal coursework or placement requirements (McGagh et al., Citation2016). The Australian Council of Learned Academies (ACOLA) conducted a review into Australia's research training, with employers reporting that PhD graduates were recruited for their research skills, but those with effective oral and written communication skills, advanced disciplinary knowledge, and flexibility in applying critical thought to diverse problems were highly sought after (McGagh et al., Citation2016). However, Manathunga, Pitt, and Critchley (Citation2009) reported less than 60% of graduates believed they developed their communication skills during their degree and less than 30% reported developing teamwork. This corresponds to a major concern voiced by employers of PhD graduates: that graduates lack communication and human relations skills (Cumming, Citation2010). The current study, therefore, examined postgraduate psychology students’ motivation towards developing theory, research, and communication knowledge and skills. Motivation was compared across those in research‐only postgraduate training and professional coursework programs using expectancy‐value theory (EVT; Eccles et al., Citation1983).

EVT OF ACHIEVEMENT MOTIVATION

EVT explains students’ choices to begin and persist with achievement‐related tasks, such as their motivation to develop their knowledge and skills in theory, research, and communication (Eccles et al., Citation1983). EVT does this through students’ social influences, subjective task values, and self‐efficacy beliefs (Eccles & Wigfield, Citation2002). Social influences refer to the value that influential others are thought to place on a domain and how this value is interpreted by the student (Eccles & Wigfield, Citation2002). For example, students perceived academic staff to value theory and research significantly more than communication skills (Green, Conlon, & Morrissey, Citation2016). Conversely, when asked about their own values, fourth‐year students reported significantly more positive values towards communication than research and, at times, theory (Green et al., Citation2016). This mismatch may be detrimental to student engagement. The perception that peers and influential others value the benefits of research has been shown to be a significant predictor of practitioners’ intentions to use research (Tasca, Grenon, Fortin‐Langelier, & Chyurlia, Citation2014). Therefore, to encourage the uptake of research evidence, it is important that postgraduate students perceive important others (especially peers and academic staff) to value the three domains equally.

Tasca et al. (Citation2014) identified attitudes as the strongest predictor of research intentions; within EVT, subjective task values are used to assess attitudes towards a domain using four dimensions (Eccles & Wigfield, Citation2002). These include (1) students' perception of how interesting a task is (intrinsic value); (2) how useful a task is to their future (utility value); (3) how important they consider performing well on a task to be (attainment value); and (4) how difficult that task is (cost value). While EVT has not been formally studied with postgraduate psychology students, program directors overseeing clinical psychology students have identified a lack of interest in research as a critical factor in the timely completion of the postgraduate thesis (Pachana, O'Donovan, & Helmes, Citation2006). Findings by Green et al. (Citation2016) also provided evidence of this lack of interest in research, with fourth‐year students reporting that it was equally important to perform well in theory, research, and communication, but that research was less interesting, less useful, and costlier than theory and communication. Fourth‐year students also reported significantly lower self‐efficacy for using research skills compared to using their theory and communication skills (Green et al., Citation2016).

Self‐efficacy has been operationalised as students’ confidence in their knowledge of theory, research, and communication and the ability to apply that knowledge (Bandura, Citation1997; Eccles & Wigfield, Citation2002). Self‐efficacy has been shown to be a significant predictor of intentions to use research (Tasca et al., Citation2014). Further, studies have indicated that clinical psychology postgraduates have poor research self‐efficacy (Wright & Holttum, Citation2012), and this leads to difficulty engaging with their research project (Gelso, Baumann, Chui, & Savela, Citation2013). This also forms a barrier to using EBP in professional psychological practice (Tasca et al., Citation2014).

To date, students’ values and self‐efficacy beliefs have not been directly compared between those in different postgraduate programs. The current study examined the values and self‐efficacy beliefs of students in Master of Psychology programs, Psychology Doctorates (PsyD: professional doctorate or Masters with PhD), and research‐only PhD programs (i.e., no coursework component). Based on findings with fourth‐year psychology students (Green et al., Citation2016), postgraduate students, regardless of program, were expected to perceive friends and family to value communication over theory, and theory over research. However, unlike undergraduate students (Green et al., Citation2016), postgraduate students were expected to perceive academic staff to value the three domains equally. Finally, students’ perceptions of their peers were explored to provide additional information on the perceived subjective norms.

For students’ task values, doctoral students (PhD and PsyD) were expected to have more positive attitudes towards research compared to Masters students, while coursework students (Masters and PsyD) were expected to have more positive attitudes towards communication than research‐only PhD students. As a lack of interest in research was reported by Pachana et al. (Citation2006), for both Masters and PsyD students, it was expected that coursework students would report lower intrinsic and higher cost values towards research. These students were expected to report equal utility and attainment values for the three domains, due to the emphasis on EBP in their programs. As the results of Manathunga et al. (Citation2009) suggest that communication skills are not prioritised in the research environment, research‐only PhD students were expected to report higher intrinsic, utility, and attainment values towards theory and research. Students’ self‐efficacy beliefs were also expected to diverge with their postgraduate sequence. Coursework students were expected to report greater self‐efficacy with communication skills than research‐only PhD students. Doctoral students were expected to report greater self‐efficacy for research skills than Masters students.

METHOD

Participants and procedure

There were 237 psychology students aged between 22 and 59-years (M = 30.98, standard deviation (SD) = 8.34, 195 females). Participants were recruited from 24 Australian universities and colleges offering postgraduate qualifications in psychology. There were 90 students enrolled in a 2‐year Master of Psychology (MPsych), and 75 students enrolled in a Psychology Doctorate (PsyD) with extensive research and coursework components. The PsyD group included those in a professional doctorate (DPsych, n = 45) or Master of Psychology with PhD (MPsych/PhD, n = 30). Students enrolled in the DPsych and MPsych/PhD did not differ on any target variables, so were combined into a single group. Finally, 72 students were enrolled in a research‐only PhD (PhD‐RO). Participants time in their program ranged from 0 to 4-years for MPsych students (M = 1.57, SD = 0.58), and 0–7-years for doctoral students (PsyD: M = 2.83, SD = 1.34; PhD‐RO: M = 2.66, SD = 1.38). The areas of practice endorsement for students in accredited psychology programs are shown in Table .

Table 2. Area of practice endorsement (AoPE) for MPsych, DPsych, and MPsych/PhD students

This research was approved by the University Human Research Ethics Committee, with further approvals obtained from Heads of Schools and HREC committees at participating universities. The survey was created using Qualtrics and distributed through email broadcasts and social media; participation was voluntary with a prize draw incentive.

Measures

A 6‐point Likert response scale, extending from 1 “Strongly Disagree” to 6 “Strongly Agree” with no neutral midpoint, was used with all scales and text anchors were matched to each question. Higher scores indicated more positive social influences, intrinsic, utility, and attainment values, and self‐efficacy beliefs towards a domain. For cost value, higher scores indicated greater difficulty, reflecting a negative attitude towards a domain.

Social influences

Two social influences scales were developed for the current study based on the measures used in Green et al. (Citation2016). The personal social influences scale assessed the extent to which students perceived friends and family to value their learning of theory (α = .86), research (α = .86), and communication (α = .87), in psychology, using a 2‐item subscale. Academic social influences used a 3‐item subscale to assess the extent that students perceived previous and current tutors, lecturers, and supervisors to value their learning in theory (α = .86), research (α = .88), and communication (α = .89), in psychology. A single‐item measure was used to assess the extent to which students perceived their peers to value each domain (theory, research, and communication).

Subjective task values

The four task values were measured with the same 5‐item subscales used in Green et al. (Citation2016). Participants rated their agreement with statements about the intrinsic (αs = .93–.96), utility (αs = .81–.91), attainment (αs = .88–.93), and cost (αs = .73–.84) value of each domain. These scale reliabilities are similar to previous research where α ranged from .76 to .96 (Green et al., Citation2016).

Self‐efficacy beliefs

Self‐efficacy was assessed using a 7‐item scale, which asked about students’ confidence in their knowledge of theory, research, and communication, and their ability to apply that knowledge to personal, professional, and societal issues (Cranney et al., Citation2012; Green et al., Citation2016). The factor structure of each domain was previously examined using principle components analysis, where a single factor emerged for each domain (Green et al., Citation2016). The current study conducted confirmatory factor analysis, using the maximum likelihood estimation procedure in AMOS 21, to test the fit of a single‐factor structure for students’ self‐efficacy beliefs for each domain. Standardised regression coefficients are shown in Table . The Chi‐squared (χ2) test showed acceptable absolute fit, while the comparative fit index (CFI) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) demonstrated good model fit (Jackson, Gillaspy, & Purc‐Stephenson, Citation2009). All items loaded significantly on their latent variables, with internal reliabilities of .81 for theory, .92 for research, and .91 for communication.

Table 3. Standardised regression coefficients for theory, research, and communication (n = 237)

RESULTS

A series of 3 (Domain: theory, research, communication) × 3 (Program: MPsych, PhD‐RO, PsyD) mixed factorial ANOVAs were used to test the hypotheses for social influences, subjective task values, and self‐efficacy. With the exception of violations to sphericity, for which the Huyhn–Feldt correction was applied (Keppel, Citation1991), assumptions of each analysis were acceptable. Significance was assessed against an alpha level of .01 to control for Type 1 error.

Social influences

Personal social influences

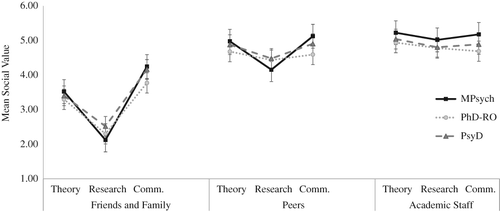

There was a significant main effect of Domain, F(2, 456) = 218.99, p < .001, ηp2 = .48. As expected, independent of program, students perceived friends and family to value communication over theory, and theory over research (all ps ≤ .001, see Fig. 1). An unexpected significant Domain by Program interaction emerged, F(4, 456) = 3.48, p = .009, ηp2 = .03. MPsych students perceived friends and family to value communication significantly more than theory, and theory more than research (all ps ≤ .001), while PhD‐RO and PsyD students perceived friends and family to value theory and communication significantly more than research (all ps ≤ .009), with no difference between theory and communication domains (all ps ≥ .015).

Peer influences

There was a significant main effect of Domain, F(2, 460) = 24.16, p < .001, ηp2 = .09, and a significant Domain by Program interaction, F(4, 460) = 4.52, p = .001, ηp2 = .04. This was explained by MPsych and PsyD students reporting that their peers would value theory and communication significantly more than research (MPsych, ps < .001, PsyD, ps ≤ .009), with no difference between theory and communication domains (p ≥ .249). In contrast, PhD‐RO students reported their peers would value the three domains equally (p ≥ .097).

Academic social influences

For academic influences, there was a significant main effect of Domain only, F(2, 464) = 4.83, p = .009, ηp2 = .02. Regardless of students’ program, academic staff were perceived to value theory followed by communication, which was followed by research, with only the difference between theory and research reaching significance (p = .004).

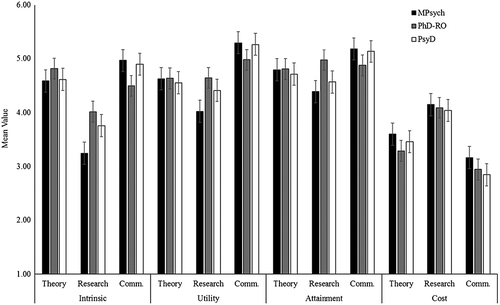

Subjective task values

The mean intrinsic, utility, attainment, and cost values for each program type is shown in Fig. 2.

Intrinsic value

There was a significant main effect of Domain, F(2, 418) = 98.48, p < .001, ηp2 = .30, and a significant Domain by Program interaction, F(4, 418) = 9.18, p < .001, ηp2 = .07. As expected, PhD (p < .001) and PsyD (p = .006) students reported significantly greater interest in research than MPsych students, with no difference between PhD and PsyD students’ research interest (p = .191). Consistent with the emphasis of their program choice, MPsych students (p = .002) reported significantly greater interest in communication than PhD‐RO students, with no significant difference between PsyD and MPsych students (p = .629). Despite this, students in all programs reported significantly more interest in theory and communication than the research domain (all ps ≤ .009), with Masters students also reporting greater interest in communication skills than in theory (p = .001).

Utility value

There was a significant main effect of Domain, F(2, 446) = 90.81, p < .001, ηp2 = .28, and a significant Domain by Program interaction, F(4, 446) = 10.54, p < .001, ηp2 = .08. PhD and PsyD students did not differ in their utility values towards research (p = .125), although both PhD (p < .001) and PsyD (p = .006) students reported significantly higher utility value towards research than MPsych students. Communication was considered significantly more useful than both theory and research (all ps ≤ .009) by students in all programs. However, while MPsych students perceived theory to also be more useful than research (p < .001), both PhD‐RO and PsyD students reported no significant difference between the utility of theory and research (p ≥ .179).

Attainment value

There was a significant main effect of Domain, F(2, 461) = 22.55, p < .001, ηp2 = .09, and a significant Domain by Program interaction, F(4, 461) = 8.99, p < .001, ηp2 = .07. The importance placed on the research domain was significantly lower amongst students in coursework programs (MPsych. p < .001, PsyD students, p = .006) compared to PhD‐RO students. Contrary to our predictions, students in coursework programs reported that communication was significantly more important than theory and research (all ps < .001). MPsych students also reported theory to be significantly more important than research (p < .001), while PsyD students reported no difference between these domains (p = .186). In contrast, for PhD‐RO students, there was no significant difference between their attainment values for theory, research, and communication (all ps ≥ .135).

Cost value

There was a significant main effect of Domain only, F(2, 413) = 117.79, p < .001, ηp2 = .34. Students in all programs regarded research to be significantly more difficult than theory, and theory to be significantly more difficult than communication (all ps < .001).

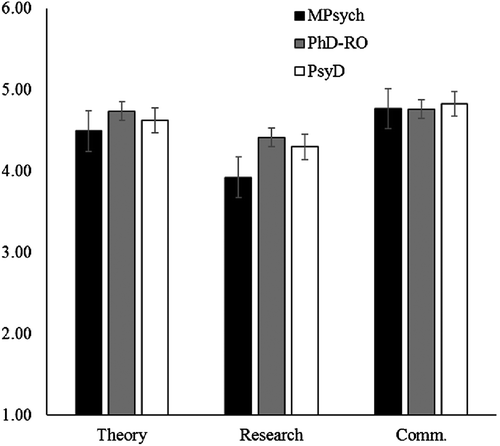

Self‐efficacy beliefs

There were significant main effects of Domain, F(2, 349) = 51.70, p < .001, ηp2 = .18, and Program, F(2, 234) = 4.70, p = .010, ηp2 = .04, which were modified by a significant Domain by Program interaction, F(3, 349) = 4.08, p = .007, ηp2 = .03 (see Fig. 3). As hypothesised, both PhD‐RO (p < .001) and PsyD (p = .004) students reported significantly greater self‐efficacy for using research than MPsych students. However, the hypothesis that students’ confidence in using communication skills would differ based on their program was not supported (all ps ≥ .585). Students’ self‐efficacy for the domains did differ, with PhD‐RO students reporting significantly greater self‐efficacy for theory (p = .002) and communication (p = .008) than that for research, while both MPsych and PsyD students reported significantly greater self‐efficacy with the communication domain than that with theory (p ≤ .005), and with theory over research (p ≤ .002).

DISCUSSION

Previous research had not investigated differences in values between psychology students in different postgraduate programs. The current study compared students enrolled in coursework postgraduate psychology programs (Master of Psychology), research‐only programs (PhD), and coursework programs with a substantial research component (Psychology Doctorates) on measures of achievement motivation. These included social influences, subjective task values, and self‐efficacy beliefs towards theory, research, and communication domains.

Social influences

Consistent with Green et al. (Citation2016), postgraduate students perceived friends and family to value communication and theory significantly more than research. This suggests that the importance of research is not well understood by postgraduate students’ personal support networks. Previous research has not addressed subjective norms by assessing postgraduate psychology students’ perceptions of their peers. The current findings suggest that coursework (Master and PsyD) students perceive their peers to value theory and communication more than research, while research‐only students report that their peers value the three domains equally. Thus, subjective norms towards research appear to be less positive among coursework students than research‐only students. Previous findings from Tasca et al. (Citation2014) suggest that this may have implications for coursework students’ willingness to rely on research in their professional practice.

Students in all programs perceived academic staff to value theory significantly more than research, but communication was perceived to be on par with both theory and research domains. These findings differ substantially from previous research with fourth‐year students, who reported academic staff value theory and research significantly more than communication skills (Green et al., Citation2016). As students progress through their postgraduate studies, the value of good communication skills becomes more apparent. To promote positive perceptions of research among postgraduate peers, programs might wish to encourage greater collaboration in postgraduate research classes by combining training for coursework students (Masters and PsyD) with research‐only students (Castonguay, Barkham, Lutz, & McAleavey, Citation2013).

Subjective task values

It was expected that postgraduate students’ values towards theory, research, and communication would correspond to their program of study. This was not found for all program types. Students completing a Masters program reported that communication was more interesting, more useful, and more important to develop than theory, and theory was more valuable than research. While these findings are consistent with reports of reduced research interest in clinical Masters programs (Pachana et al., Citation2006), it is concerning that Masters students do not consider research skills to be as useful, or important to develop in, as theory or communication skills. Further, Masters students also considered theory to be less valuable than communication. As with the Masters group, PsyD students also reported that communication was more interesting, more useful, and more important to develop in than theory and research, but did not report any difference between the latter domains. However, both MPsych and PsyD students reported significantly lower attainment values for the research domain compared to PhD‐RO students. This may be due to the competing priorities and heavy workloads reported in psychology coursework programs (Scott et al., Citation2011).

Further, the hypothesis that PhD students would show a preference for theory and research domains relative to communication was not supported. PhD‐RO students reported greater interest for communication and theory than research, and considered communication to be of more use than the theory and research domains. However, where PhD students differed was in their attainment values; PhD‐RO students considered theory, research, and communication to be equally important to develop, suggesting that research‐only students are aware of the importance of developing their communication skills (McGagh et al., Citation2016). While research‐only students reported less interest in communication than Masters students, their interest did not differ from the PsyD group. In addition, PhD‐RO students responded in line with coursework students when reporting on the perceived difficulty of theory, research, and communication. Collectively, postgraduate students reported that communication was considerably less difficult than theory, which in turn was considered significantly less difficult than research. Green et al. (Citation2016) suggest that students may enter psychology training with significantly greater self‐efficacy for their communication skills. Thus, students may perceive their communication skills to be highly developed when they enter undergraduate and postgraduate studies, and therefore, more easily developed than skills required in the theory and research domains.

While recommendations for closing the science–practice divide have often concentrated on practitioners alone, this has been criticised in favour of a more balanced approach (Beutler, Williams, Wakefield, & Entwistle, Citation1995). To address negative beliefs about research, Tasca et al. (Citation2014) promoted the establishment of practice‐research networks (PRNs) where clinicians collaborate directly with researchers to “define research questions, design research protocols, and implement studies” (p. 201). It was expected that PRNs could encourage research–clinician pairings that would change existing subjective norms, improve attitudes, and provide opportunities for clinicians to engage in and build confidence towards research (Castonguay et al., Citation2013; Tasca et al., Citation2014). Thus, the development of formal PRNs may be an ideal place to bridge the science‐practice divide during postgraduate study and beyond. Ideally, students in all programs would be encouraged to attend and collaborate on projects to forge stronger links. PRNs could introduce beneficial changes to the research training environment for PhD‐RO students who report less interest and greater cost for research compared to theory and practice domains. A review by Gelso et al. (Citation2013) suggested that presenting research as a partly social experience and emphasising the collaborative aspects of the research environment was associated with improved research attitudes and better self‐efficacy among psychology postgraduates.

Self‐efficacy beliefs

Students reported on their confidence in expressing and applying their knowledge of theory, research, and communication to personal, professional and societal issues. The hypothesis that doctoral students would report greater self‐efficacy for research than Masters students was supported. However, students in all programs still reported greater self‐efficacy for communication than theory, and for theory than research. All postgraduate psychology students successfully completed research projects as part of their studies. Despite students having the capability to use research skills, they appeared to have less confidence in applying these skills. This could be explained by the high‐perceived cost of research compared to the other domains. An alternative explanation for this may be a lack of preparation for students to translate their knowledge of research, independently, to applied problems (Luebbe, Radcliffe, Callands, Green, & Thorn, Citation2007). This coincides with the findings of the ACOLA review, which suggested that greater emphasis should be placed on developing research students’ transferable skills and improving the assessment of research competencies (McGagh et al., Citation2016). Further, while the programs examined in the current study all include a research component, it is critical to note that the 5 + 1 pathway, does not (APAC, Citation2010).

Limitations and future research

The current study offers a snapshot of the values and self‐efficacy beliefs of postgraduate psychology students. However, there are two major limitations. First, the values and self‐efficacy beliefs discussed reflect the views of postgraduate students at all stages of their respective programs. A cross‐sectional study of commencing postgraduate psychology students with a longitudinal follow‐up at the end of each year of study would contribute much to our understanding of how postgraduate psychology students’ task values and self‐efficacy beliefs are influenced by training. Second, while the current study aimed to compare students enrolled in the 5 + 1 pathway to the 2‐years Masters pathway, there were insufficient respondents to form a comparison group. Therefore, it is critical that future research investigate the impact of research training on fifth‐year students in 1‐ and‐2‐year Masters programs, especially as the 5 + 1 program is growing in popularity as a pathway to general registration.

Implications for psychology education and training

Currently psychology education and training are limited by the traditional didactic approaches used in the Australian postgraduate training environment (Scott et al., Citation2011). However, the current research suggests that students require more integrated postgraduate learning experiences. Strategies to provide this can include scaffolding students’ use of research and decision‐making skills in simulated or problem‐based learning (PBL) scenarios (Hmelo‐Silver, Citation2004). There has been much support for the inclusion of simulation and PBL approaches in postgraduate education (Stevens, Hyde, Knight, Shires, & Alexander, Citation2015). Research suggests that PBL has advantages over traditional learning activities in enhancing self‐directed learning and cognitive competencies, understanding of content, and interpersonal or collaborative skills (Hmelo‐Silver, Citation2004; Stevens et al., Citation2015). Most studies of PBL have used self‐report assessments, which, due to students’ preference for this teaching style, could be biased in favour of PBL (Scott et al., Citation2011; Stevens et al., Citation2015). According to EVT, this may be an advantage of the approach: by enhancing students’ interest and enjoyment of research training and demonstrating the utility of research skills in problem‐based scenarios, students’ values (and achievement motivation) towards research can be improved.

The current model of education and training may partially explain students’ diminished interest in research. It is considered by some that the science followed by practice model is outdated and not fit for purpose. Emphasis on research training in the first 4-years of psychology education with little incorporation of interpersonal and communication skills may result in a desire by postgraduate students to develop these skills as a priority. Hence, they are likely to hold less interest in additional research pursuits, particularly as research self‐efficacy was low at the honours level. This is especially the case among the Masters programs. A more balanced approach to the science and practice of psychology throughout the education and training of psychologists may remedy this and ensure students value all three domains equally. Perhaps as the review of education and training in psychology in Australia is completed, the new APAC Standards for accreditation will allow for this. A balanced model such as this can provide a richer integration of specialised skills‐based training in both postgraduate coursework and research programs. This is likely to increase the efficacy of tomorrow's psychological workforce, including practitioners, researchers, and educators.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge assistance from a Griffith University Research Grant awarded to Conlon and Morrissey. Other than providing employment and research opportunity for Conlon and Morrissey, and research resources for Green, Griffith University had no input into the research described in this article. They appreciate the support of Australian higher education providers who provided assistance distributing the survey used in this article. The authors declare no conflict of interest arising from the publication of this article.

REFERENCES

- Australian Psychological Society. (2012). Psychology 2020: The 2011–2012 Presidential Initiative on the future of psychological science in Australia. Retrieved from http://www.psychology.org.au/Assets/Files/2012_APS_PIFOPS_WEB.pdf

- Australian Psychology Accreditation Council. (2010). Rules for Accreditation and Accreditation Standards for Psychology Courses. Retrieved from http://www.psychologycouncil.org.au/Assets/Files/APAC_Rules_for%20_Accreditation_and_Accreditation_Standards_for%20_Psychology_Courses_Ver_10_June_2010.pdf

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self‐efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman.

- Bell, I., & Mellor, D. (2009). Clinical judgements: Research and practice. Australian Psychologist, 44, 112–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050060802550023

- Beutler, L. E., Williams, R. E., Wakefield, P. J., & Entwistle, S. R. (1995). Bridging scientist and practitioner perspectives in clinical psychology. American Psychologist, 50, 984–994. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066X.50.12.984

- Briner, R., & Rousseau, D. (2011). Evidence‐based I‐O psychology: Not there yet. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 4, 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-9434.2010.01287.x

- Castonguay, L., Barkham, M., Lutz, W., & Mcaleavey, A. (2013). Practice‐oriented research: Approaches and applications. In J.Lambert (Ed.), Bergin and Garfield's handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (pp. 85–133). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

- Cranney, J., Botwood, L., & Morris, S. (2012). National Standards for Psychological Literacy and Global Citizenship: Outcomes of Undergraduate Psychology Education. Final report ALTC/OLT National Teaching Fellowship. Retrieved from http://www.groups.psychology.org.au/Assets/Files/Cranney_NTF_Final_Report_231112_Final_pdf.pdf

- Cumming, J. (2010). Contextualised performance: Reframing the skills debate in research education. Studies in Higher Education, 35, 405–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903082342

- Eccles, J., Adler, T. F., Futterman, R., Goff, S. B., Kaczala, C. M., Meece, J., & Midgley, C. (1983). Expectancies, values and academic behaviors. In J. T.Spence (Ed.), Achievement and Achievement Motives. San Francisco, CA: W. H. Freeman.

- Eccles, J., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 109–132. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135153

- Edwards, D., Radloff, A., & Coates, H. (2009). Supply, demand and characteristics of the higher degree by research population in Australia. Canberra, Australia: Department of Innovation, Industry, Science and Research.

- Gelso, C. J., Baumann, E. C., Chui, H. T., & Savela, A. E. (2013). The making of a scientist‐psychotherapist: The research training environment and the psychotherapist. Psychotherapy, 50, 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028257

- Graham, J. M., & Kim, Y. (2011). Predictors of doctoral student success in professional psychology: Characteristics of students, programs, and universities. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67, 340–354. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20767

- Green, R. A., Conlon, E. G., & Morrissey, S. A. (2016). Task values and self‐efficacy beliefs of undergraduate psychology students. Australian Journal of Psychology, 69, 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12125

- Hmelo‐silver, C. E. (2004). Problem‐based learning: What and how do students learn? Educational Psychology Review, 16, 235–266. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:EDPR.0000034022.16470.f3

- Horn, R., Troyer, J., Hall, E., Mellott, R., Coté, L., & Marquis, J. (2007). The scientist‐practitioner model: A rose by any other name is still a rose. American Behavioral Scientist, 50, 808–819. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764206296459

- Jackson, D. L., Gillaspy, J. A., & Purc‐stephenson, R. (2009). Reporting practices in confirmatory factor analysis: An overview and some recommendations. Psychological Methods, 14, 6–23. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014694

- Jones, C. (2008). From novice to expert: Issues of concern in the training of psychologists. Australian Psychologist, 43, 38–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050060601089470

- Keppel, G. (1991). Design and analysis: A Researcher's handbook (3rd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Lodge, J. (2015). Transitioning into academia: The challenges and opportunities for early career psychologists and psychological scientists. InPsych, 37, 14–15 Retrieved from http://www.psychology.org.au/inpsych/2015/dec/lodge.

- Luebbe, A., Radcliffe, A., Callands, T., Green, D., & Thorn, B. (2007). Evidence‐based practice in psychology: Perceptions of graduate students in scientist–practitioner programs. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63, 643–655. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20379

- Manathunga, C., Pitt, R., & Critchley, C. (2009). Graduate attribute development and employment outcomes: Tracking PhD graduates. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 34, 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930801955945

- Mcgagh, J., Marsh, H., Western, M., Thomas, P., Hastings, A., Mihailova, M., & Wenham, M. (2016). Review of Australia's Research Training System. Report for the Australian Council of Learned Academies (ACOLA). Retrieved from http://acola.org.au/PDF/SAF13/SAF13%20RTS%20report.pdf.

- Pachana, N., O'donovan, A., & Helmes, E. (2006). Australian clinical psychology training program directors survey. Australian Psychologist, 41, 168–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050060600820644

- Scott, T., Pachana, N., & Sofronoff, K. (2011). Survey of current curriculum practices within Australian postgraduate clinical training programmes: Students' and programme directors' perspectives. Australian Psychologist, 46, 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9544.2011.00030.x

- Spring, B. (2007). Evidence‐based practice in clinical psychology: What it is, why it matters; what you need to know. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63, 611–631. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20373

- Stevens, B., Hyde, J., Knight, R., Shires, A., & Alexander, R. (2015). Competency‐based training and assessment in Australian postgraduate clinical psychology education. Clinical Psychologist. [Advance online copy] https://doi.org/10.1111/cp.12061

- Tasca, G., Grenon, R., Fortin‐langelier, B., & Chyurlia, L. (2014). Addressing challenges and barriers to translating psychotherapy research into clinical practice: The development of a psychotherapy practice research network in Canada. Canadian Psychology, 55, 197–203. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037277

- Wright, A., & Holttum, S. (2012). Gender identity, research self‐efficacy and research intention in trainee clinical psychologists in the UK. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 19, 46–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.732

- Zachar, P., & Leong, F. T. L. (1991). Development and validation of the scientist‐practitioner inventory for psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 38, 331–341. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.38.3.331