Abstract

Objective

Young men are very reluctant to seek help for anxiety disorders. In particular, the factors that facilitate mental health help‐seeking in adolescent males are poorly understood. This study aimed to investigate the barriers and facilitating factors to help‐seeking behaviour for clinical anxiety in Australian adolescent males.

Method

The views of 29 adolescent males, both with and without experience of clinical anxiety symptoms, were elicited using semi‐structured interviews and focus groups. Verbatim transcripts were analysed using grounded theory.

Results

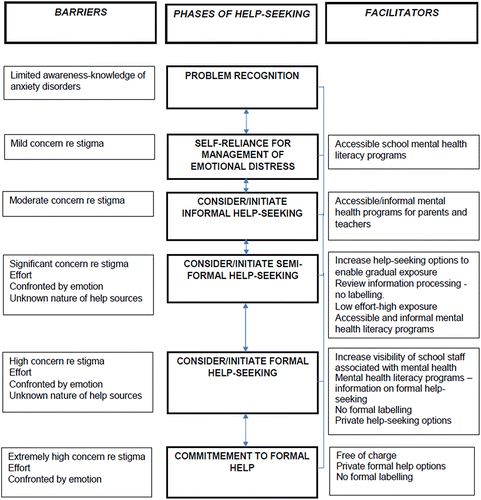

Primary barriers to help‐seeking included stigma (particularly in relation to social norms of masculinity), effort, limited awareness/knowledge of symptoms of anxiety and a sense of being ‘confronted’ by private emotions through help‐seeking. Facilitating factors included increasing the accessibility of school‐based mental health literacy programs and providing a wider range of formal and informal help‐seeking options. Other facilitators related to amendments in how mental health information is presented and investments into high speed/low effort help‐seeking options. A preliminary model of mental health help‐seeking in adolescent males with clinical anxiety is presented.

Conclusion

Adolescent males feel that they risk significant stigma by help‐seeking for mental health problems but lack information as to the benefits or the experience of help seeking. A stepped approach to options for mental health support and information for this population should be evaluated.

What is already known about this topic

Adolescent males are often reluctant or unwilling to seek help for mental health issues.

Stigma, poor mental health literacy, and concerns regarding confidentiality have been identified as common barriers to mental health help‐seeking in young people although little is known about adolescent male‐specific barriers to help‐seeking.

Anxiety disorders are the most common mental health disorder in young people and are associated with greater levels of ‘weak not sick’ mental health stigma than other mental health disorders. This stigma is where a mental health disorder is attributed to a personal weakness rather than an illness.

What this topic adds

The current investigation is one of the first to investigate help‐seeking for anxiety disorders specifically in adolescent males.

This investigation identified barriers to help‐seeking that included stigma (particularly in relation to social norms of masculinity), effort, limited awareness/knowledge of symptoms of anxiety and a sense of being ‘confronted’ by private emotions through help‐seeking.

This investigation also identified facilitating factors to help‐seeking that included increasing the accessibility of school‐based mental health literacy programs and providing a wider range of formal and informal help‐seeking options. Other help‐seeking facilitators related to how mental health information is presented and investments into high‐speed/low‐effort help‐seeking options.

A preliminary model is proposed to illustrate how barriers and facilitating factors may influence different components of the help‐seeking process.

Young adults (aged 16–24-years) have higher rates of mental disorders than any adult age group in Australia (Slade, Johnston, Oakley Browne, Andrews, & Whiteford, Citation2009). It is estimated that 14% of Australian adolescents (aged 12–17-years) will experience a mental health disorder over a 12‐month period (Lawrence et al., Citation2015). Anxiety disorders alone are estimated to affect 6% of adolescent males and 8% of adolescent females (Lawrence et al., Citation2015). Despite these statistics, mental health service use is reported to be lower in young adults than any other adult age group (Slade et al., Citation2009). Young men are found to be the most reluctant to seek help and approximately only 15% of clinically anxious adolescent males (next to 25% of anxious adolescent females) utilise mental health services (Merikangas et al., Citation2011; Reavley, Cvetkovski, Jorm, & Lubman, Citation2010). Although formal help‐seeking (i.e., from mental health professionals) has been found to attenuate psychological distress (e.g., Gulliver, Griffiths, & Christensen, Citation2010), both qualitative and quantitative investigations have found young adults to prefer self‐reliance or informal sources of help (e.g., family, friends, religious leaders) when managing symptoms of psychological distress (Gulliver et al., Citation2010; Rickwood, Citation1995).

A systematic review by Gulliver et al. (Citation2010) reported the barriers and facilitators to mental health help‐seeking in young adults (aged 12–25-years). The review identified that barriers to help‐seeking included public, perceived, and self‐stigmatising attitudes to mental illness, concerns regarding confidentiality, poor mental health literacy, and a preference for self‐reliance. To a lesser extent, a lack of accessible services, poor emotional competence, and a preference for informal sources of support were also found to inhibit formal help‐seeking. Facilitating factors were found to be comparatively under‐researched with only three studies (all qualitative) included in the review investigating methods to promote help‐seeking. Key facilitator themes included a positive past experience with help‐seeking, good social support, trust, and a positive relationship with the care provider and, to a lesser extent, education on mental health and positive attitudes towards seeking help generally. To date, help‐seeking in young adults has tended to conceptualise non‐engagement in help‐seeking as ‘a series of discrete barriers rather than as an integrated complex of factors or help‐seeking process’ (Martínez‐Hernáez, DiGiacomo, Carceller‐Maicas, Correa‐Urquiza, & Martorell‐Poveda, Citation2014, p. 2). As a result, there is a need to develop the youth help‐seeking literature in a manner which considers the complexity of mental health help‐seeking and adds focus to capturing data on facilitating factors.

Within Australia, adolescent males are the group least likely to seek treatment for common mental health problems (Burgess et al., Citation2009), (Reavley et al., Citation2010). The lack of specific help‐seeking investigations in adolescent male populations is surprising given that barriers to help‐seeking are often influenced by gender. First, low emotional competence, stigmatising attitudes towards mental illness, and lower mental health literacy have all been associated with lower help‐seeking intentions and behaviour in young adults (Ciarrochi, Deane, Wilson, & Rickwood, Citation2002; Gulliver et al., Citation2010). Young men have been found to have lower mental health literacy and lower emotional competence (i.e., the ability to identify, describe, understand, and communicate emotions) than their female equivalents (Ciarrochi, Wilson, Deane, & Rickwood, Citation2003; Rickwood, Deane, Wilson, & Ciarrochi, Citation2005). Second, the literature suggests that male and female adolescents utilise available help sources differently. Martínez‐Hernáez et al. (Citation2014) found that male participants were more likely to seek help from their friends to ‘forget about’ emotional distress, a behaviour associated with normalising symptoms of depression. In contrast, female participants tended to understand their social networks as a resource for ‘talking about it’ or problematizing the distress. Third, a fear of threatened masculinity has been identified as a barrier to mental health help‐seeking in adult and adolescent males (Hutchinson & John, Citation2012; Tyler & Williams, Citation2014). Health help‐seeking has been traditionally conceptualised as a feminine behaviour and males who fail to conform to hegemonic masculine behaviours, are perceived as weak, less masculine with reduced social power (e.g., Lyons, Citation2009; Spalding, Zimmerman, Fruhauf, Banning, & Pepin, Citation2010).

Where information on the barriers and facilitating factors to adolescent male help‐seeking is available, a number of methodological limitations are pertinent. Studies which have focused on help‐seeking in young males have typically recruited participants aged 17-years and older (Tyler & Williams, Citation2014; Wilson, Cruickshank, & Lea, Citation2012). Older adolescents are likely to be far more autonomous in their health‐care management than younger adolescents, and at the age of 18, young people will have adult health‐care options. Such investigations have also collected data predominantly by indirect methods such as through other individuals in the help‐seeking process (i.e., parents, sports coaches, school nurses; Hutchinson & John, Citation2012; Wilson et al., Citation2012). Perhaps even more importantly, while disorder‐specific investigations into help‐seeking in young adults are beginning to emerge (e.g., suicidal behaviour, depression; Deane, Wilson, & Ciarrochi, Citation2001; Wilson, Deane, & Ciarrochi, Citation2005; Wilson, Rickwood, & Deane, Citation2007), these have yet to be extended to anxiety disorders. Anxiety disorders (in particular, social anxiety disorder) have been associated with greater levels of ‘weak not sick’ mental health stigma than other common mental health disorders in young adults (Yap, Wright, & Jorm, Citation2011). This is where a mental disorder is attributed to a personal weakness rather than an illness. Mental health stigma relates to a negative perception of individuals with mental health problems where they are considered weak, flawed, dangerous, and/or socially incompetent (Wahl, Citation2003). Consequently, a comprehensive understanding of stigma towards help‐seeking for anxiety and help‐seeking behaviour in adolescent males with anxiety is needed.

The aim of the present study was to obtain the perspectives of adolescent males aged 12–18-years, both with and without experience of clinical anxiety, on the barriers and facilitating factors to help‐seeking for anxiety. A qualitative methodology was utilised to ensure a detailed understanding of how barriers and facilitators interact in the context of the mental health help‐seeking process.

METHOD

Participants

Purposive sampling was employed to recruit adolescent male participants ranging in age between 12 and 18-years. To generate a representative sample, participants with and without experience of formal help‐seeking for clinical anxiety were recruited from New South Wales, Australia. The final sample comprised of 29 adolescent males aged 12–18-years (M = 15.17, SD = 1.91). All participants were in full‐time school education.

Clinical participants (n = 8) were recruited from child and adolescent mental health services across New South Wales, gumtree (a nationwide internet classified advertisements and community website), and the Centre for Emotional Health, Macquarie University. Sources of professional help obtained by participants included a school counsellor (n = 1), a private local psychologist (n = 2), and a child and adolescent mental health clinic which offered online treatment (n = 2) in addition to face‐to‐face therapy (n = 2). Non‐clinical participants (n = 21) were adolescent males who did not have a mental health disorder and had not sought help for a mental health disorder. Non‐clinical participants were recruited from gumtree and two independent schools based in New South Wales. Using the Australian Rural, Remote, and Metropolitan Areas (RRMA) classification, 4 (14%) participants lived in a remote area (Rem2), 18 (62%) participants lived in a small rural centre (R2), and 7 (24%) lived in a metropolitan city (M1) area (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Citation2016). Recruitment ceased when data saturation had been achieved. Data saturation is considered to have been reached when the collection of new data does not provide additional information and when the analysis of data no longer returns new codes (Mason, Citation2010).

Procedure

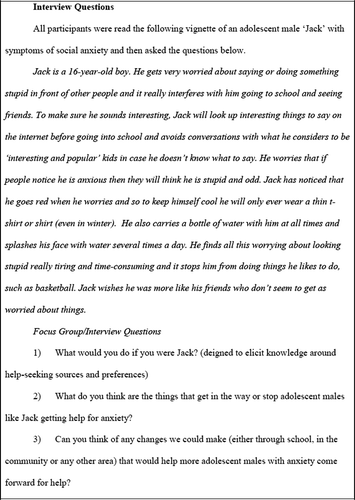

Ethical approval for the project was granted by the Macquarie University Committee for Ethics in Human Research. Participants and their parents were required to sign information consent forms prior to their involvement in the interviews. To facilitate discussion in interviews and focus groups (FGs), a vignette with related questions was used to identify participant's knowledge of and preferences regarding help‐seeking options (see Fig. 1).

With the exception of one FG, a female aged 31-years conducted the interviews in mental health clinics, schools, or at the participant's home and occurred either in four FGs (n = 20) or individually (n = 9). Due to the personal nature of the topic, participants with a history of clinical anxiety, or non‐clinical participants opting not to participate in a group (n = 1), were interviewed individually. FGs contained between three and six participants (FG 1: n = 3; FG 2: n = 6; FG 3: n = 4; FG 4: n = 7) with other adolescents of similar ages (FG 1: 13–14-years; FG 2: 16–17-years; FG 3: 12–13-years; FG 4: 15–16-years). FGs were conducted where possible (as opposed to single person interviews) as one of the major advantages of this technique lies in the kind of interaction that emerges during the debate (Acocella, Citation2012).

Interviews (FG and individual) lasted between 43 and 67-min. All interviews were audio recorded for transcription purposes and video recorded to supplement the transcription with pertinent non‐verbal communication. FGs and individual interviews all followed the format detailed in Fig. 1.

Data analysis

The interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed by the first author in accordance with the principles of grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, Citation2009). Analysis was initially conducted within and across individual questions in order to identify emerging themes relating to global themes of (1) help source preferences, (2) barriers, and (3) facilitating factors to help‐seeking. Following this analysis, a behavioural model was developed to conceptualise the dynamic relationship between the barriers and facilitating factors to help‐seeking in adolescent males with anxiety (see Fig. 2). In accordance with the principles of grounded theory, the model incorporated existing theory on barriers from the youth help‐seeking literature.

The thematic analysis component of the data analysis followed a structure proposed by Attride‐Stirling (Citation2001). This process involved coding the material, identifying key themes, then constructing, describing, exploring, and summarising thematic networks (an analytic tool used to organise the thematic analysis of the data) before interpreting broader patterns across the data. The data were organised into ‘basic’ (the lowest order theme), ‘organising’ (middle‐order theme that organises the basic themes into clusters of similar issues), and ‘global’ (super‐ordinate themes that encompass the principal metaphors in the data as a whole) themes. To determine the level of representativeness of responses, four levels of frequency labels were also applied (see Mazzer, Rickwood, & Vanags, Citation2012). A theme that applied to all or all but one of the cases was considered general. A typical theme applied to more than half of the cases (up to the cut‐off for general). A theme was considered variant when included in at least two cases up to a maximum of half of all cases. Responses from clinical and non‐clinical participants were categorised separately (i.e., to qualify as a ‘general’ theme, it had to be present in all or all but one of the clinical interviews (a total of eight) and in all or all but one of the non‐clinical interviews/FGs (a total of five). This was done to ensure that all themes reported were represented across both participant groups and not specific to one subgroup.

A more in‐depth analysis was conducted to facilitate the development of the help‐seeking model. The grounded analysis component of the data analysis followed a structure proposed by Charmaz (Citation2006). Initial coding process involved line‐by‐line coding and studying fragments of data words, lines, segments, and incidents‐closely for their analytic import. Then focused coding, using the most significant and/or frequent earlier codes to sift through large amounts of data, was then conducted. Throughout the process comparative methods were employed and data was compared with data and existing codes.

An inter‐rater reliability check (for both forms of analysis) was conducted by randomly selecting six transcripts using an online random number generator. The selected transcripts were then independently coded by a second researcher (the fourth author). The development of almost identical themes suggested that the original interpretation of the data had been appropriate. However, a number of original themes were developed and refined as a result of the inter‐rater check and subsequent discussion (see results for further details).

RESULTS

Global theme 1: Help‐source preferences

Preference for self‐reliance

Most participants indicated a preference for self‐reliance in response to Question 1 (i.e., what they would do if they were in Jack's position). This general theme was present in seven clinical interviews and four non‐clinical FGs. Participants were less certain on what ‘relying on themselves’ would involve and, when asked what they would do, suggested non‐specific help‐seeking responses such as ‘get a new mindset’, ‘do something fun’, ‘try to relax’, and ‘use people as role models’. Many participants stated that they would be comfortable speaking to friends or family members and typically held strong opinions on which of these two options they would prefer.

‘I wouldn't talk to anyone personally. I would just probably keep trying to deal with it myself and try my best not to let anyone else know about it’ (non‐clinical FG member, aged 14-years).

Global theme 2: Barriers to help‐seeking

The organising themes associated with the global theme of ‘barriers to help‐seeking’ identified included stigma, limited knowledge‐awareness of information on clinical anxiety, effort, and feeling ‘confronted’ by private emotion through help‐seeking.

Stigma

An important typical organising theme was that of stigma, identified in six clinical interviews, one non‐clinical interview and four FGs. Stigma (particularly public stigma) was reported by participants of all ages to be a significant barrier to help‐seeking. Mental health was conceptualised as a ‘secret’ or ‘hidden’ problem and consequently help‐seeking was identified as involving exposure to potential stigma (usually characterised as bullying or exclusion). In particular, many interviewees felt that help‐seeking in youth (as opposed to adulthood) was a public, rather than a private, experience. Several clinical participants spoke about the ‘embarrassment’ of being removed from class by the counsellor or the counsellor's office being next to public areas (e.g., lunch rooms).

‘I don't think there's really anywhere to go [in terms of getting help for anxiety], I think that's backing yourself against a wall’ (non‐clinical FG member, aged 14-years).

‘it's be kind of embarrassing [to leave class for an appointment with the school counsellor] because everyone would ask me where are you going and this and that, why are you going to miss so much class’ (clinical participant, had sought formal help from a school counsellor, aged 13-years).

When exploring the theme of stigma, many adolescents articulated views associated with social norms of masculinity (a variant theme present in five clinical interviews and two FGs). Help‐seeking behaviour was conceptualised as ‘weak’ or ‘not macho’, perceived to potentially compromise their social status leaving them vulnerable to stigma. A subtheme associated with themes of masculinity related to concerns that others would dismiss anxiety as not a ‘real’ illness, further increasing the likelihood of the help‐seeker being stigmatised as ‘weak’. A number of interviewees felt that this specific fear would cause them to deny experiencing symptoms both to others and themselves.

‘Yeah, there's a sort of stereotype of males…. if you are suffering from one of those [mental health problems] that you are weaker than everyone else’ (non‐clinical FG member, aged 16-years).

‘Seeking help is often the toughest thing to do, um, it can be tough but, um, it's not, it doesn't make you look tough’ (clinical participant, aged 14).

Limited awareness‐knowledge of clinical anxiety

Many participants felt that most adolescent males, parents, and teachers would lack important information on the symptoms and treatment of clinical anxiety. This typical theme was present in two FGs, one non‐clinical, and eight clinical interviews. In particular, participants felt others lacked information on the ‘treatable’ nature of the disorder and this lack of knowledge was felt to promote the perception of anxiety as ‘not a real illness’. School based mental health literacy programs were considered ‘inaccessible’ and unhelpful with classes on social and emotional development being considered overly formalised and ‘like school’ involving ‘too much reading’ and ‘assignments’. As a result, help‐seeking from peers was considered unhelpful and ineffective and more likely to result in stigma than useful support.

While participants perceived parents and teachers as being less likely (than other adolescents) to stigmatise a young person for having an anxiety disorder, they felt confident that such individuals would also lack the knowledge to help them. A few participants expressed concern that as a result of help‐seeking from parents or teachers adolescents would be ‘forced’ into formal help‐seeking options (see also ‘confronted by emotion’ theme below) due to a lack of knowledge of other support options.

‘They have like awareness days and all that … but they don't actually explain what it is. They don't explain how to help’ (clinical participant, had sought help from a school counsellor and private psychologist, aged 18-years).

A limited knowledge/awareness of anxiety treatments and support, in particular the unknown nature of help‐sources, in terms of what would happen if they sought help (i.e., the process of help‐seeking, policies around confidentiality, or the likelihood of being given ‘labelled’ with a diagnosis) was also identified as a key barrier to help‐seeking. Specifically, many participants had concerns about the efficacy of help‐seeking/treatment. All of these concerns contributed to a sense of help‐seeking being unfamiliar and potentially risky.

Confronted by emotion

A variant theme (featuring in one FG and five clinical interviews) related to an intense negative experience (either imagined or real) as a result of participants speaking about their feelings or emotional problems to a health‐care provider. Participants’ felt these topics to be ‘private’, and as a result, these conversations felt ‘confronting’. Several clinical participants described lying to school counsellors because, although they recognised that they needed help, the conversation about emotions felt too personal and intrusive. Many participants felt that formal help seeking (i.e., seeing a counsellor, logging on to a website about clinical anxiety) would feel ‘confronting’ in several ways, first, it would mean that the problem became ‘real’ and second, that they would be labelled as ‘having an issue’ (i.e., mental health disorder).

‘it is, um, quite confronting to go onto a website all about treatment, like it's quite, um, yeah, you've just suddenly stepped into another world’ (clinical participant, aged 14-years).

‘yeah, I wasn't comfortable having that conversation (about anxiety)’ (clinical participant, aged 16-years).

Effort

The majority of participants (a typical theme featuring in three FGs and five clinical interviews) identified low motivation or ‘laziness’ as an important barrier to help‐seeking in this population. Any help source that required organisation (such as booking an appointment) or effort (such as following an online treatment program) was perceived as highly problematic unless the anxiety disorder was very severe.

‘It would be too hard to get like to work [get adolescent males to seek help online] you'd need to work to do stuff’ (non‐clinical FG member, aged 16-years).

Global theme 3: Facilitating factors to help‐seeking

The global theme of ‘facilitating factors to help‐seeking’ related to organisational themes of a gradual introduction to information/support, increased help‐seeking options for adolescents, accessible school‐based anxiety programs, and a review of how information on anxiety is presented. These themes were often extensions of discussions related to the barriers identified above.

Fast to access, low effort to use options that introduce mental health information/support concepts gradually

Participants felt that, in order to increase the number of adolescent males engaging in help‐seeking behaviour, options for help/information needed to be highly visible and easily accessible. This typical theme was present in three FGs, one non‐clinical and five clinical interviews. Most participants felt that schools should increase the information provided on clinical anxiety within school lessons on social and emotional development in early high school.

The motivation to seek help for emotional distress was perceived to be very short lived and, consequently, more immediate methods of communication with formal help services (i.e., the school counsellor) were required, such as through an online messenger service, phone application, or text to capitalise on this. Several participants felt that school counsellors should be visible in schools and offer ‘drop in’ sessions so the need to organise an appointment was removed. Some participants suggested that schools should allow students to be able to try online anxiety treatment during mental health information classes in order to be able to consider this as an option before committing to a program.

Several participants also felt that schools should have members of staff (dual‐role teachers) with training in mental health that adolescents could talk to easily. These staff members would not be directly connected to mental health (reducing stigma) and adolescents may have contact with the staff member as part of their daily routine (low effort).

‘yeah, you just need to get to know them, um, and it's quite easy if they're your year co‐ordinator or someone like that as well’ (clinical participant, aged 14-years).

Participants believed that information on anxiety needed to be accessible at all times. Several participants recommended having a phone app (to an anxiety information website or treatment program) or placing advertising (such as beyondblue posters) at the top of school staircases so that adolescents have a constant visual reminder. Participants regularly asked if more information could be linked to social media (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter) where adolescents could incidentally learn about mental health and sources of help without the effort of actively searching for it.

‘So kind of putting it in front of kids as often as possible so that they get lots of opportunities to be reminded that it's there if they need it’ (clinical participant, aged 13-years).

Increased informal and formal help‐seeking options for adolescents

Discrete help‐seeking

Concern regarding confidentiality and help‐seeking being very ‘public’ was identified as a typical theme and was evident throughout the interviews (see Stigma), featuring in four FGs and four clinical interviews. The provision of a dual‐role teacher, options to speak to school mental health personnel anonymously (e.g., text, messenger) and monitored online forums for adolescents with mental health questions were all popular suggestions believed to facilitate more discrete help‐seeking. Adolescents felt that counsellors’ offices should be positioned in a more discrete area of the school, options for evening and weekend appointments should be available and that adolescents are not removed from class for appointments.

Accessible school‐based anxiety information programs

Discussions associated with inaccessible school mental health literacy programs revealed a desire for more relatable information on mental health. This global theme featured in three FGs, one non‐clinical, and seven clinical interviews. Participants described a desire for a more personalised learning experience which involved (either directly or video) listening to the experience of an individual (ideally a young person) who had experienced anxiety as an adolescent. Participants felt that mental health literacy programs should stress the ‘seriousness’ of anxiety (i.e., that it can cause significant life interference if left untreated) and that clinical anxiety is a treatable illness (i.e., how an individual's life can change/improve after completing treatment). Adolescents felt these two components should be communicated using personal stories/examples that they could relate to.

‘Probably knowing, or even just having the possibility, that you can be better off at the end’ (non‐clinical FG member, aged 14-years).

‘Hearing other people's success stories [would make an adolescent more likely to seek help for anxiety]’ (non‐clinical FG member, aged 14-years).

Participants felt, in addition to being more accessible, school‐based mental health literacy programs should communicate information on (1) formal help seeking professionals (e.g., professional restrictions regarding confidentiality, non‐judgemental process) and treatment programs; (2) efficacy of treatment for anxiety disorders; (3) details of impact when anxiety is untreated/severe; and (4) specific options for help rather than ‘just come and talk to someone’.

‘I guess if you got information like, you know, like [about] counsellors and stuff … you shouldn't be intimidated by them [counsellors], they're like here to help, you know, like not going to judge you’ (clinical participant, in the process of seeking help from a child and adolescent mental health clinic, aged 13-years).

Review of anxiety information presentation

A smaller help‐seeking barrier (a variant theme, identified in two FGs and three clinical interviews) related to labelling (either by a formal help‐source or the individual themselves). Participants felt that information on anxiety and informal/formal help‐sources needed to utilise less formal and less diagnostic‐driven vocabulary. For example, participants described being far more likely to log on to a website about general men's health issues than a website tailored to clinical anxiety difficulties. It was also clear that information needed to have a ‘masculine’ tone, with examples using stereotypical ‘manly’ figures (‘Like, the tradies … the guys that work sort of in tough situations’, clinical participant, aged 16-years), in order for adolescent males to feel that they could relate to it. It should be noted that themes identified above appeared consistent across participants from different geographic locations.

Model of mental health help‐seeking behaviour in adolescent males

An important theme throughout the interviews was the conceptualisation of help‐seeking intentions and behaviour as fluid processes that alter in the context of different help‐seeking opportunities and the formality of each option. Drawing from existing theoretical conceptualisations (Gulliver et al., Citation2010; Martínez‐Hernáez et al., Citation2014), a preliminary model is proposed to illustrate how barriers and facilitating factors may influence different components of the help‐seeking process (see Fig. 2). The model suggests that adolescents engage at a level of help‐seeking that is dependent on a dynamic interaction of barriers and facilitators that are moderated by severity of symptoms. The ‘barriers’ and ‘facilitators’ identified at each stage represent factors which would encourage or influence the adolescent to move from the current phase (e.g., preferring to manage emotional distress independently) to the following phase (consideration of informal help). However, at each point in the model, participants may return to a previous phase of help‐seeking.

The severity of the disorder and the formality of the help‐seeking options appeared to alter the nature and impact of specific barriers/factors influencing the decision making process. The interviews suggested that, in order for adolescent males to engage in formal support for anxiety, they must first naturally (without external pressure) transition from a preference of self‐reliance to contemplating more informal help‐seeking options and then more formalised help‐seeking options. Participants also felt that greater exposure to options that would typically fall in between formal and informal help‐seeking categories would facilitate more adolescent males to consider formal help‐seeking options.

DISCUSSION

This study sought to investigate the barriers and facilitating factors to help‐seeking for anxiety disorders in adolescent males and to provide a conceptualisation of how these factors interact within the help‐seeking process. Consistent with existing youth help‐seeking research (Gulliver et al., Citation2010), perceived stigma, limited mental health literacy, and a preference for self‐reliance were found to be barriers to mental health help‐seeking. Additionally, as previously identified in the literature, discussions of stigma often related to ‘weak not sick’ forms of stigma and social norms of masculinity (Hutchinson & John, Citation2012; Tyler & Williams, Citation2014; Yap et al., Citation2011). The study findings overlapped significantly, both in terms of barriers and facilitators, with results reported in the Martínez‐Hernáez et al. (Citation2014) qualitative investigation into non‐professional help‐seeking among Spanish young adults with depression. This suggests that although both are qualitative studies with small samples and conducted in different countries, the findings might be more generalisable than is traditionally estimated in qualitative research.

Several novel constructs were identified. The study identified that help‐seeking may be inhibited by (1) a belief that society does not perceive anxiety as a ‘real problem’ and (2) a sense of feeling ‘confronted’ by private emotion. Participants reported current school‐based mental health literacy programs are perceived as being ‘inaccessible’ and not widely reaching (i.e., no programs for teachers and parents). These views have important implications for how information on clinical anxiety is communicated to adolescents. Perhaps most significantly, the current study adds to the existing literature by providing a more developed understanding of facilitating factors to help‐seeking in adolescent males. Participants provided practical suggestions regarding how services could facilitate discrete options for help‐seeking in a manner which was fast, low effort, and communicated the seriousness of clinical anxiety disorders. There were very few differences between the clinical and non‐clinical participants in terms of the themes that emerged, only ‘confronted by emotion’ was found to be more present in clinical versus non‐clinical participant interviews.

Consistent with the findings of Martínez‐Hernáez et al. (Citation2014), help‐seeking was found to be a dynamic and multi‐faceted process rather than a discrete set of barriers and facilitators. It is clear that the relationship between barriers and help‐seeking behaviours in young adults is not one‐dimensional. Even participants with a non‐stigmatising view of mental health, a good social network, and high levels of mental health literacy (i.e., individuals where established barriers to help‐seeking were not particularly prominent), said they would be extremely reluctant to seek help if they had a mental health disorder. As demonstrated in Prochaska and DiClemente's (Citation1982) transtheoretical model of intentional human behaviour change, individuals need to be psychologically ready (i.e., pre‐conceptualisation and conceptualisation to have occurred) to embrace behaviour change. Furthermore, the theory of self‐determination asserts that in order to be intrinsically motivated people need (1) a sense of skill mastery; (2) a sense of belonging to others; and (3) to feel in control of their own behaviours (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000). Therefore, enabling anxious youth to become knowledgeable on the topic of anxiety, exposing adolescents to individuals with personal experience of anxiety disorders, and facilitating opportunities for young adults to contemplate help and move between informal‐formal help‐seeking gradually, may significantly improve youth help‐seeking rates. Future research is needed to investigate the impact of implementing a stepped care approach to help‐seeking.

A number of limitations of the study should be acknowledged. First, while a sample size of 29 participants is considered an appropriate sample size for a qualitative investigation (Depaulo, Citation2000) and data saturation was established, this nevertheless limits the generalisability of its findings. Second, the sample was also more homogeneous than ideally desired with most participants (68%) living in a rural area. All non‐clinical participants lived in a rural area, whereas clinical participants were from rural, remote, and metropolitan areas. Despite this limitation, themes were found to be consistent across participants from different geographic locations. Third, the majority of clinical participants (62%) were recruited from an independent school, whereas the clinical participants may have attended public or private education (this information was not collected). This difference in education may have influenced participants’ opportunities for, and consequently views towards, mental health support. Finally, the vignette utilised in the interviews related to symptoms of social anxiety and future studies should aim to investigate adolescent help‐seeking within the context of specific anxiety disorders.

CONCLUSION

This investigation demonstrates that adolescent males feel that they risk significant stigma and discrimination by help‐seeking for mental health problems and are highly uncertain as to the benefits or the experience of seeking help. The data suggest that, currently, this population are not provided with sufficient options to seek help discretely and in a manner that minimizes identified barriers. Further research in this area may have the potential to facilitate higher rates of formal help‐seeking for mental health problems in this population.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank the adolescents, parents and schools who participated in the study. This study was part‐funded by the Beyondblue National Priority Driven Research Program MEN0029.

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Acocella, I. (2012). The focus groups in social research: Advantages and disadvantages. Quality & Quantity, 46(4), 1125–1136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-011-9600-4

- Attride‐stirling, J. (2001). Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 1(3), 385–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/146879410100100307

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2016). Rural, remote and metropolitan areas (RRMA) classification. Retrieved from http://www.aihw.gov.au/rural-health-rrma-classification

- Burgess, P. M., Pirkis, J. E., Slade, T. N., Johnston, A. K., Meadows, G. N., & Gunn, J. M. (2009). Service use for mental health problems: Findings from the 2007 national survey of mental health and wellbeing. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 43(7), 615–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048670902970858

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative research. London: Sage.

- Ciarrochi, J., Deane, F. P., Wilson, C. J., & Rickwood, D. (2002). Adolescents who need help the most are the least likely to seek it: The relationship between low emotional competence and low intention to seek help. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 30(2), 173–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069880220128047

- Ciarrochi, J., Wilson, C. J., Deane, F. P., & Rickwood, D. (2003). Do difficulties with emotions inhibit help‐seeking in adolescence? The role of age and emotional competence in predicting help‐seeking intentions. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 16(2), 103–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951507031000152632

- Deane, F. P., Wilson, C. J., & Ciarrochi, J. (2001). Suicidal ideation and help‐negation: Not just hopelessness or prior help. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 57(7), 901–914. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.1058

- Depaulo, P. (2000). Sample size for qualitative research: The risk of missing something important. Quirk's Marketing Research Review, Retrieved April 20, 2015, from http://www.quirks.com/articles/article_print.asp?arg_articleid=636

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (2009). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Victoria: Transaction Publishers.

- Gulliver, A., Griffiths, K. M., & Christensen, H. (2010). Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help‐seeking in young people: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 10(1), 113–128. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-10-113

- Hutchinson, L., & John, W. S. (2012). Creating connections: Strategies to improve adolescent boys’ access and engagement with school‐based health services. Contemporary Nurse, 40(2), 258–268. https://doi.org/10.5172/conu.2012.40.2.258

- Lawrence, D., Johnson, S., Hafekost, J., Boterhaven de haan, K., Sawyer, M., Ainley, J., & Zubrick, S. (2015). The mental health of children and adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing. Canberra: Telethon Kids Institute.

- Lyons, A. C. (2009). Masculinities, femininities, behaviour and health. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 3(4), 394–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00192.x

- Martínez‐hernáez, A., Digiacomo, S. M., Carceller‐maicas, N., Correa‐urquiza, M., & Martorell‐poveda, M. A. (2014). Non‐professional‐help‐seeking among young people with depression: A qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry, 14(1), 124–135. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-124

- Mason, M. (2010). Sample size and saturation in PhD studies using qualitative interviews. Qualitative Social Research, 11(3), 8. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-11.3.1428

- Mazzer, K. R., Rickwood, D. J., & Vanags, T. (2012). Teachers and sports coaches supporting young people's mental health: Promotion, prevention, and early intervention. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology, 66, 489–494.

- Merikangas, K. R., He, J.‐p., Burstein, M., Swendsen, J., Avenevoli, S., Case, B., … Olfson, M. (2011). Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in US adolescents: Results of the National Comorbidity Survey–Adolescent Supplement (NCS‐A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 50(1), 32–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.006

- Prochaska, J. O., & Diclemente, C. C. (1982). Transtheoretical therapy: Toward a more integrative model of change. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 19(3), 276–288. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0088437

- Reavley, N. J., Cvetkovski, S., Jorm, A. F., & Lubman, D. I. (2010). Help‐seeking for substance use, anxiety and affective disorders among young people: Results from the 2007 Australian national survey of mental health and wellbeing. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 44(8), 729–735. https://doi.org/10.3109/00048671003705458

- Rickwood, D. (1995). The effectiveness of seeking help for coping with personal problems in late adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 24(6), 685–703. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01536951

- Rickwood, D., Deane, F. P., Wilson, C. J., & Ciarrochi, J. (2005). Young people's help‐seeking for mental health problems. Advances in Mental Health, 4(3), 218–251. https://doi.org/10.5172/jamh.4.3.218

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self‐determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well‐being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

- Slade, T., Johnston, A., Oakley browne, M. A., Andrews, G., & Whiteford, H. (2009). 2007 National survey of mental health and wellbeing: Methods and key findings. Australasian Psychiatry, 43(7), 594–605. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048670902970882

- Spalding, R., Zimmerman, T. S., Fruhauf, C. A., Banning, J. H., & Pepin, J. (2010). Relationship advice in top‐selling men's magazines: A qualitative document analysis. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 22(3), 203–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952833.2010.503795

- Tyler, R. E., & Williams, S. (2014). Masculinity in young men's health: Exploring health, help‐seeking and health service use in an online environment. Journal of Health Psychology, 19(4), 457–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105312473784

- Wahl, O. (2003). Depictions of mental illnesses in children's media. Journal of Mental Health, 12(3), 249–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/0963823031000118230

- Wilson, C., Deane, F., & Ciarrochi, J. (2005). Can hopelessness and adolescents' beliefs and attitudes about seeking help account for help negation? Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(12), 1525–1539. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20206

- Wilson, C., Rickwood, D., & Deane, F. (2007). Depressive symptoms and help‐seeking intentions in young people. Clinical Psychologist, 11(3), 98–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/13284200701870954

- Wilson, R., Cruickshank, M., & Lea, J. (2012). Experiences of families who help young rural men with emergent mental health problems in a rural community in New South Wales, Australia. Contemporary Nurse, 42(2), 167–177. https://doi.org/10.5172/conu.2012.42.2.167

- Yap, M. B., Wright, A., & Jorm, A. F. (2011). The influence of stigma on young people's help‐seeking intentions and beliefs about the helpfulness of various sources of help. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 46(12), 1257–1265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-010-0300-5