Abstract

Objective

Previous experimental research has yielded inconclusive findings regarding the effects of Holocaust trauma to survivors’ descendants, while qualitative studies have suggested diverse long‐term impacts of this traumatic past. While the extant literature has focused mainly on Israeli and North American children of survivors, this study drew on theories of transgenerational trauma transmission to explore the lived experiences of six Jewish Australian grandchildren of Holocaust survivors.

Method

Data from semi‐structured interviews were analyzed using interpretative phenomenological analysis to investigate how the impacts of historical trauma are experienced across generations in an Australian sample.

Results

The impact of their grandparents’ Holocaust experiences was found to echo across the participants’ affective experiences, their sense of connection to family histories, their understanding of being different to others, and their political and ethical values. An analysis of these findings suggested that the participants define themselves in a collective manner as part of a group of survivors’ descendants, with their post‐Holocaust positioning existing in a state of tension alongside their Australian identity.

Conclusions

This study extends the literature on transgenerational trauma by shedding light on how the identities of Australian grandchildren of Holocaust survivors continue to be profoundly informed by their identification with familial narratives of trauma, despite their generational distance from the Holocaust.

What is already known about this topic

The psychological and physical deprivation of the victims of the Holocaust are among the worst noted in recent history with the trauma sequelae noted not only among the victims themselves but also their children—the ‘second generation’.

The impacts documented among second‐generation descendants include both psychopathological and physical health vulnerabilities together with evidence for more positive outcomes, including enhanced adaptation, resilience, and psychological strength—thus the ‘echoes’ of trauma can be diverse in subsequent generations.

The majority of research into third‐generation descendants has indicated that transgenerational trauma symptomology, evidenced by many quantitative clinically focused studies have all but dissipated in the third generation; however, a few qualitative studies focusing on less clinically based sequelae suggest that such echoes remain.

What this topic adds

Evidence that the phenomenological expression of transgenerational trauma is not homogenous between second‐ and third‐generation descendants.

The experiences of third‐generation descendants are heavily influenced by their active connection with the Holocaust—these individuals have sought knowledge and understanding of their grandparents experiences by avenues additional to grandparent narratives, therefore overcoming the ‘conspiracy of silence’ evident in their parents’ often more passive Holocaust exposure.

The identities of third‐generation descendants are unique and changing as these individuals reconcile their place in Australia with their Holocaust history. Ultimately, for the participants here, their Holocaust identity was privileged, suggesting some deep connection with the traumatic experiences of their grandparents.

Traumatic events to which parents have been exposed can have a profound psychological effect on their descendants in many populations (Burchert, Stammel, & Knaevelsrud, Citation2017; de Graaf, Citation1998). The Holocaust, and its impact on the survivors and their descendants, is perhaps the most comprehensively researched case of transgenerational transmission of trauma (Starman, Citation2006). Until recently, this literature has predominantly focused on Jewish children of survivors, commonly referred to as ‘second‐generation survivors’ (Solomon, Citation1998), with a select few now examining its impact on ‘third‐generation survivors’ (Giladi & Bell, Citation2013; Scharf & Mayseless, Citation2011); grandchildren whose connections to this traumatic past are not the result of direct involvement but arise from their grandparents’ experiences (Chaitin, Citation2002).

The Holocaust refers to the systematic persecution and murder of almost 6 million Jews, along with 5 million homosexuals, Romani people, Communists, people with disabilities, and others, who were targeted for genocide between 1933 and 1945 in Nazi Germany and German‐occupied territories (Dawidowicz, Citation1986). Individuals who survived the Holocaust were subject to trauma that has been classified as among the most severe in human history because of the chronic and repeated exposure to both physical and psychological distress (Herman, Citation1992). Research has shown that the trauma of the Holocaust has affected the psychological wellbeing of survivors, with the term ‘survivor syndrome’ used to define a set of psychopathological features that have been observed to characterize many members of this population (Niederland, Citation1968). These symptoms include chronic depression and anxiety, guilt, fear of renewed persecution, sleep disturbances and nightmares, anhedonia, hypochondria, emotional disruption, cognitive disturbances, and personality problems (Juni, Citation2016; Yaroslawitz, DeGrace, Sloop, Arnold, & Hamilton, Citation2015), with a selected few studies also suggestive of more positive expressions of trauma, specifically, resilience and adaptive abilities (Barel, van Ijzendoorn, Sagi‐Schwartz, & Bakermans‐Kranenburg, Citation2010). For this reason in this study, we take up Wiseman and Barber's (Citation2008) notion of trauma ‘echoes’, in recognition of the diverse ways that trauma exposure can be evidenced across time and place.

Herman (Citation1992) describes trauma as an experience in which an individual is directly involved in or a witness to an event that evokes feelings of loss of safety, helplessness, intense fear, horror, and a threat of annihilation. The event not only depletes an individual's personal resources but also renders their basic psychic adaptation system helpless (Diller, Citation2003). In the early 1960s, Israeli clinicians were among the first to expand the classic definition of trauma upon observing psychological problems in children of Holocaust survivors (de Graaf, Citation1998). Some studies, using clinical diagnostic indicators of trauma, have since suggested trauma symptomology does not transcend generations (see meta‐analysis by van IJzendoorn, Bakermans‐Kranenburg, & Sagi‐Schwartz, Citation2003), while others have suggested that children of survivors tend to present with a specific ‘second‐generation psychological profile’ (Felsen, Citation1998). Here, the children are described as being within the normal range of psychological functioning but exhibit a range of common characteristics (Felsen, Citation1998), including an increased vulnerability to general psychological distress and the more trauma specific clinical diagnoses like post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Yehuda, Halligan, & Grossman, Citation2015), separation and individuation issues (Kellermann, Citation2001a), and feelings of obligation to compensate for their survivor parents’ suffering (Kellermann, Citation2001b). They have also been shown to suffer from impaired self‐esteem, problems with aggression, and difficulties handling interpersonal conflicts (Kellermann, Citation2001b). Kellermann (Citation2001a, p. 43) observed that survivors’ children tend to demonstrate excellent occupational, social, and emotional functioning in ordinary circumstances, but that this may be interrupted by periods of anxiety and depression that have a distinct ‘Holocaust flavor’ in times of crisis. For this reason, a stringent clinical investigation, using diagnostic criteria, might be insensitive to the subtle trauma sequelae among survivor offspring.

The mechanisms for how trauma might be conveyed across generations were initially understood to develop out of the relationships held between parents (the ‘survivors’) and their children (the ‘second generation’). For many, it was thought that the narratives of trauma experience might be vicariously traumatizing for survivor descendants. However, research reporting on the ‘conspiracy of silence’, emanating not only from the survivor parents’ need to forget and adjust to new social contexts, but also from their belief that withholding information about the horrors of the Holocaust was crucial to their children's normal development (Bar‐On et al., Citation1998) suggests that such narrative mechanisms could not be exclusively responsible. From this early work, the mechanisms for transgenerational trauma (i.e., attachment, social learning, and epigenetics) have flourished with the recognition that trauma experienced by one generation can result in trauma‐like symptomology among second‐generation individuals who were neither directly exposed to the original trauma nor to the more indirect story‐telling exposure; that is, the trauma is transmitted via less explicit means (Yehuda et al., Citation2016).

A limited number of third‐generation studies have been undertaken. Akin to the meta‐analysis conducted with second‐generation descendants, Sagi‐Schwartz, van IJzendoorn, and Bakermans‐Kranenburg (Citation2008) reported no evidence to suggest poorer wellbeing or adaptation among third‐generation descendants. However, Wiseman and Barber (Citation2008) argue that the quantitative approach taken in many of the studies included in Sagi‐Schwartz et al.'s (Citation2008) meta‐analysis adhered mainly to psychopathological paradigms and might therefore have masked important emotional sensitivities or vulnerabilities that are not adequately captured by clinical questionnaires. Instead, qualitative studies, which have predominantly used Israeli and North American samples, have pointed to a wider range of effects experienced by grandchildren of survivors, many of which are non‐pathological, or at least sub‐clinical, in nature (Lazar, Litvak‐Hirsch, & Chaitin, Citation2008).

Continued investigations with third‐generation descendants are necessary as generational differences are likely. For instance, the ‘conspiracy of silence’ (Danieli, Citation1998) that characterized the post‐war decades is seemingly less apparent for the third generation (Solomon, Citation1998); in countries such as Israel, the USA, and Australia, grandchildren of survivors have growing up in a surrounding culture that has commemorated, taught, and commercialized narratives of survival in the mainstream media (Moskowitz, Citation2015). They are encouraged to learn about their grandparents’ pasts through interviews for school roots projects, and since the 1990s thousands of students have participated in Holocaust‐focused excursions to Poland (Sagi‐Schwartz et al., Citation2008). It stands to reason that our understanding of transgenerational trauma, gathered from second‐generation survivors, might require updating and re‐negotiating as societal influences shift across generations.

This study is specifically concerned with Australian grandchildren of Holocaust survivors. The geographical and political distance of this population from European Holocaust sites means that the Australian context differs considerably from those predominantly studied in the existing literature (Rowland‐Klein & Dunlop, Citation1998). In Israel, the Holocaust has been shown to have profoundly permeated the national psyche, holding a central position as a ‘national trauma’ (Elon, Citation1981), with sociocultural mechanisms at play that ensure that it remains a widespread preoccupation even for Jewish Israelis who do not have a family connection to this event (Lazar et al., Citation2008). Likewise in the USA where survivors comprise a far smaller proportion of American Jewry and play a less prominent role in Jewish life, yet the Holocaust narrative takes pride of place on the national mall in Washington's Holocaust Memorial Museum. In this way, the US national narrative is integrative of the events of the Holocaust (Jilovsky, Silverstein, & Slucki, Citation2015). In Australia, Jewish people constitute 0.5% of the total population (Graham, Citation2014) and Holocaust discourse does not operate as part of the construction of national identity as it does in Israel and, to a lesser extent, the USA. Therefore, the experiences of Australian third‐generation descendants may be critically unlike those of previously studied samples. In this study, then, we examine the lived experiences of Jewish Australian grandchildren of Holocaust survivors. Specifically, we ask how the experiences of their grandparents as Holocaust survivors echo throughout the lives of a sample of young Jewish Australian women and men.

METHOD

This research was conducted using qualitative methods to capture the emotional worlds of the participants. Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) was employed to arrive at a ‘finely tuned’ understanding of the subjective lived experiences of Jewish Holocaust survivors’ grandchildren living in Australia.

Data collection

Data were collected using semi‐structured interviews to enable the interviewer flexibility in following lines of questioning to facilitate access to areas of significance in the participant's life (Smith & Osborn, Citation2008). All interviews were conducted by the chief investigator who holds post‐graduate qualifications in psychology. An interview schedule was generated comprising 11 open‐ended and non‐directive questions designed to create opportunities for participants to share their personal experiences and understandings of how they perceive their grandparents’ Holocaust background to have influenced their lives.

Participants

Participants included a purposive sample of six individuals, including three women and three men. Participants were more than 18 years of age (M = 28 years), had spent most of their life living in Australia, and had at least one Jewish Holocaust survivor grandparent who immigrated to Australia after World War Two (see Table ). Participants were recruited following the publishing of advertisements, outlining the purpose of the study and the inclusion criteria, on online forums regularly frequented by the Australian Jewish community, from here a snowball recruitment strategy was also utilised. All participants who made contact with the research team as a result of viewing the advertisements consented to being interviewed. Once the six participant quota was achieved, the advertisements were removed. Face‐to‐face interviews were conducted in locations including participants’ homes and quiet spaces in libraries. All interviews were audio‐recorded and later transcribed verbatim.

Table 1. Participant demographics

Ethical considerations

This research received full approval from the Australian College of Applied Psychology Human Research Ethics Committee (308270516). Participation was voluntary and written consent was obtained from each participant with the understanding that all data collected would be de‐identified to assure anonymity. Potential discomfort was minimised by providing participants the opportunity to view the interview schedule in advance and to decline to answer any questions without prejudice. Details of support services were provided to participants at the end of the interview.

Data analysis

The interview transcripts were analysed using IPA, a methodology consistent with the research aims of the current study, in that it is committed to an in‐depth examination of how people make sense of their lived experiences (Smith & Osborn, Citation2008). IPA follows the phenomenological and interpretative traditions in focusing on the subjective account of a phenomenon as it is experienced in the lifeworld of the individual, while explicitly recognising the centrality of the researcher's own thoughts and theoretical positioning in making sense of that account. Smith and Osborn (Citation2008, p. 53) describe the ‘double hermeneutic’ of this analytic activity as a dual process involving the participants trying to make sense of their world, in turn requiring the researcher ‘to make sense of the participants trying to make sense of their world’. The analytic process mirrored that of Braun and Clarke (Citation2013) and Shaw (Citation2010) by implementing an iterative process whereby the interpretation of the participant transcripts was done through initial coding, the development of code clusters, the identification of emerging themes all with a continued reflection back to the participant's words to ensure that these themes remained consistent with the participant's narrative.

Validity and integrity

Steps were taken to ensure that the analysis was valid and internally consistent. First, individual transcripts were read independently by members of the research team for initial coding and thematic development. Second, a rigorous reiterative process, taking comprehensive notes, keeping records of each stage of the process and using reflexive practice, was undertaken independently by both researchers. Finally, following the development of the final thematic structure, all researchers engaged in a disconfirming case analysis of final themes to ensure they faithfully represented the participants’ disclosures (Yardley, Citation2008) before asking participants for their feedback on the arrived at thematic structure. At each step of this process, the two researchers met to discuss their independent understandings of the participant disclosures; in this way the research team endeavoured to maintain a faithfulness to the participant disclosures by reducing the capacity for the participants’ words to be interpreted through the eyes of any single researcher.

RESULTS

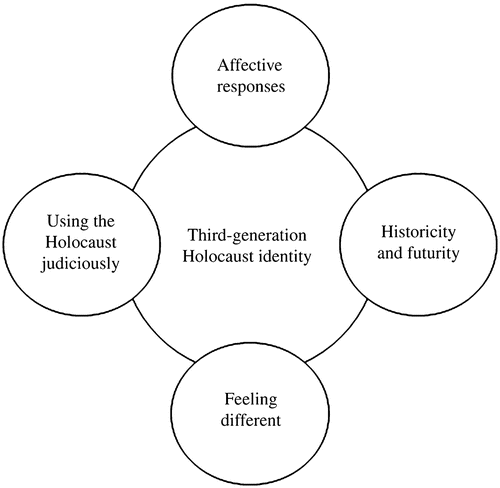

The analysis revealed that the participants constructed their experiences through four main shared themes: Affective responses, Historicity and futurity, Feeling different, and Using the Holocaust judiciously. When these four themes were analysed in composite, they were found to yield one central superordinate theme: Third‐generation Holocaust identity (the thematic map is depicted in Fig. 1).

Theme 1: Affective responses

In reflecting on the impact they perceive the Holocaust and their grandparents’ backgrounds have had on their lives, all six participants described experiencing strong affective responses. In particular, participants expressed feelings of anxiety and fear regarding renewed persecution based on their Jewish identity, which they explicitly linked to the history of the Holocaust:

Kate: I always think life's going so good, when will the next war happen? Like I always have that sense of feeling. Like when's the next methodical murder spree gonna happen?

Kate believes that her worry and hypervigilance about an ‘Armageddon style thing’ occurring is ‘the main point of like what the Holocaust has done to my psychology’. Dean makes a similar attribution when he states that, ‘I think for myself, and I think for other Jews there's this heightened sensitivity or heightened threat alert when anti‐Semitism happens, which I think is directly related to the Holocaust’.

Coupled with a sense of fear, anxiety, and hypervigilance, a number of participants spoke about Holocaust‐related nightmares, and, although they were unable to provide precise accounts of the content of these nightmares, they all described them in an emotionally evocative manner:

Brad: I can't tell you if it's Auschwitz, I just don't know, but it's something that it feels like I'm there … it's quite like graphic and quite unpleasant. I'm I'm I'm in it, I'm not just observing it. Um, it feels like the real thing, whatever that is. And it feels very vivid.

Dean: I've had on a few occasions nightmares where I'm a concentration camp prisoner, and they were quite intense nightmares.

Participants also expressed considerable emotional difficulty in relation to talking about their families’ Holocaust experiences or when confronted with Holocaust‐related stimuli:

Jake: I still get very emotional about the sense of loss that I feel. Even though I never knew any of those people I still feel an enormous sense of loss… To know that your own loved one has lost their entire family, and not just lost them but they were all murdered, you know it's it's a crushing feeling.

Here, Jake describes the ‘crushing feeling’ he experiences when thinking about the losses his grandparents have suffered, a feeling mirrored by another participant who would not recount his grandparents’ experiences at length because he found it ‘hard to talk about’. For three participants, this emotional difficulty has led to varying degrees of avoidance. Kate, on the most extreme end of the spectrum of participants’ experiences, speaks about avoiding all Holocaust‐related material and has not openly spoken to her grandfather about his experiences, despite his willingness to communicate. Other participant approaches are more nuanced and have shifted over time to encompass periods of greater and lesser engagement, because it can be ‘too painful’:

Ella: Now I avoid it more [pause] I find it too painful … I'm not saying that I won't go back again. But, yeah, I pulled away from it. It was like I got close but then pulled away.

Theme 2: Historicity and futurity

The analysis of the participants’ accounts revealed that they all feel highly connected to their families’ stories of Holocaust suffering and survival. They are motivated to learn about and engage with their historical origins, while also committing themselves to sustaining these family narratives into the future:

Maya: I feel like knowing where you came from especially when it's such a kind of traumatic history of our people, and such a recent history, it's really important to know all of it, like right down to the really small details.

The only participant who did not attend a Jewish school and did not partake in a Jewish heritage ‘roots project’ was Jake, who instead designed his own research project at the age of 27, incorporating personal writing about his experience as a grandchild of survivors along with research in trauma and memory studies. Jake describes his interest in engaging with Holocaust history in emphatic terms, drawing on notions of ‘obsession’, ‘compulsion’, and ‘overwhelming force’. He says:

Jake: [I]t continues to be a lifelong journey, something that I'll always explore and engage with… I've been to about fifteen Holocaust museums around the world. That arguably is bordering on obsessive, I think it's fair to say… but I just didn't stop, you know, I couldn't stop.

Four participants emphasised the importance of having face‐to‐face contact with living Holocaust survivors, acknowledging their own unique position in being the last generation to personally know survivors. Kate finds the fact that the last remaining survivors will soon die to be ‘shocking’, believing that ‘things are gonna change really quickly’. Indeed, all participants see themselves as responsible for passing their grandparents' stories on to future generations.

Theme 3: Feeling different

The analysis revealed that all six participants consider their Holocaust heritage a significant part of who they feel themselves to be and that they use this identification to distinguish themselves from others:

Ella: I definitely feel like, elitist is not the right word, but I definitely feel like people who don't have grandparents who went through Auschwitz or any kind of concentration camp will never get it. And they're not entitled to feel the same pain that survivors do. So I remember a friend she visited Auschwitz and came back quite down about it. And I remember being like quite pissed off, I was like well you don't have a right cos it didn't happen to you.

Of all the participants, Ella demonstrates the most evident personal identification with her grandparents’ suffering. She feels a sense of entitlement over the suffering of the Holocaust and uses this as a means to differentiate herself from those who are not descendants of survivors and will therefore ‘never get it’.

Notably, while many of the participants use their family's Holocaust background to differentiate themselves from non‐descendants and to connect with other descendants through ‘shared experience’, to use Brad's words, they hold contrasting views on the application of the label ‘third‐generation survivor’. This is a term regularly used in the literature and colloquially to describe the grandchildren of Holocaust survivors. Ella is the only participant who identifies with this label, and in particular with the term ‘survivor’. She states:

Ella: I see myself as a third generation of course. Yeah. And I very much identify with that term survivor.

Three other participants, however, reject the use of ‘survivor’ as a self‐descriptor:

Jake: I don't describe myself as a survivor, I'm not a survivor I didn't survive anything, and I do take some umbrage with those that describe themselves in that way, although they're free to, because I think it's a dangerous slippage, ethically speaking, between identity positions.

Maya: I don't feel like I've survived anything. I don't feel like I survived personally… I feel like they're the survivors, and I am the product of their survival.

Brad: The word survivor is just inappropriate because no‐one who wasn't there can ever be a survivor.

The participants also articulated a broader sense of feeling different to other Australians. Maya and Ella express ambivalence about their Australian identity relative to their Jewish identity:

Maya: I happen to be Australian, but I'm a Jew, I'm an Australian Jew. That's how I feel. So I feel like the emphasis in my life is much more Jew oriented than Australian. Does it have something to do with the Holocaust? I'm pretty sure it does.

Four of the participants’ accounts demonstrate complex and multifaceted identifications that reveal deeper tensions and negotiations between their third‐generation Holocaust identities and their Australian identities. For Jake, this tension is described viscerally as a ‘split’ between ‘two selves’:

Jake: [T]here are times when I do feel very much that my Australian identity is like this, almost like a second skin that I have … it's not a feeling I have all the time, it's just at those moments where there's a kind of bifurcation or a split of these two selves, the self that is like informed strongly by the Holocaust and uses it at least intellectually and ethically as a buttress against atrocities and human rights abuses, and on the other hand, this Aussie identity which is kind of like [strong Australian accent] she'll be right mate, just suck it up mate. I I I hate it.

Theme 4: Using the Holocaust judiciously

All six participants’ accounts exhibited a strong tendency to use the Holocaust and their position as grandchildren of survivors as a framework through which to situate themselves in relation current political and cultural events.

Jake: I think undeniably my relationship to the Holocaust has informed my social conscience.

In Maya's words, the Holocaust makes the participants ‘stop and think’, enabling them to form ethically informed opinions on contemporary issues. For instance, a number of the participants raised the issue of Australia's treatment of asylum seekers. Dean states that the Holocaust provides him with ‘a basis to be empathetic towards refugees and asylum seekers’, while others draw direct parallels between the Holocaust and Australia's approach to refugees:

Maya: [I]t's terrible that I say this but my grandmother has a terrible view on the refugees of today, and I'm like Bubba you were that person running away. So it affects the way that I I guess view politics now and view refugees now … it just makes me stop and think, like 70 years ago that was my grandparents trying to get away from persecution.

A final way in which the participants’ political attitudes have been shaped by the Holocaust is reflected in their views on Israel, with three participants expressing feelings of connection to and solidarity with Israel:

Dean: I am sensitive to anti‐Semitism and to anti‐Israeli or criticism of Israel.

This appears to be in part because a number of them view Israel, in Ella's words, as a ‘place of escape’. Ella explains her attachment to Israel as stemming ‘not from a Zionistic point of view, but from a um, a place of escape point of view’, in the sense that ‘if the Jews were kicked out of Australia then I guess that's somewhere where we are supposedly safe’.

Superordinate theme: Third‐generation Holocaust identity—‘This is who I am’

Maya: [I]f I think of what I thought about the Holocaust when I was growing up … I guess it was from a very kind of point of understanding like this is who I am and this is how I grew up and my grandparents came from a place.

The four main themes that emerged from the analysis of the participants’ accounts yielded one overarching superordinate theme, Third‐generation Holocaust identity. By analysing the four themes in composite, it becomes clear that the Holocaust, and their position as grandchildren of Holocaust survivors, profoundly informs the identities of these young Jewish Australian women and men. Importantly, the trauma of the Holocaust was seen to echo throughout various elements of the participants’ identities, as played out in their affective responses, their sense of connection to their family histories and commitment to continuing these narratives into the future, the experience of feeling different to others, and their social and political values. For some participants, the influence of the Holocaust on their self‐understanding is overt:

Jake: I don't think my life would be as rich, I don't think I would understand myself as well.

For others, the effect of the Holocaust is more understated and ‘unconscious’:

Brad: I've read a little bit about inherited trauma and that sort of thing. And again with the caveat that I wasn't there and I will never know what it was like, but it it has to have some effect on an unconscious level at least.

Despite these differences and notwithstanding that three participants reject the use of the label, third‐generation survivor’, their accounts indicate that they all identify themselves as part of a group of grandchildren of Holocaust survivors. The Holocaust provides the participants with a framework for understanding their own and others’ identities, and it is used to distinguish them from others and to situate themselves in relation to current political and social issues.

DISCUSSION

The participants’ Holocaust backgrounds were found to produce a number of common emotional responses and sensitivities that impact their patterns of thinking and are indicative of trauma symptoms (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). As such, while this investigation was not concerned with identifying psychopathological symptoms among third‐generation descendants, the remnants of such trauma symptomology was present. The typical patterns of hyper‐vigilance and avoidance were universally spoken of alongside experiences like nightmares, despite these descendants having no direct exposure to such information. Such experiences can be understood through the psychodynamic model of trauma transmission, previously used to explain second‐generation symptomology, whereby descendants unconsciously absorb the repressed and insufficiently worked‐through Holocaust experiences of their survivor parents, or, in this case, grandparents (Kellermann, Citation2001b; Rowland‐Klein & Dunlop, Citation1998).

Previous studies have referred to a ‘second‐generation profile’, where children of Holocaust survivors are described as being within the normal range of psychological functioning but often exhibit a range of characteristics, such as elevated levels of anxiety, guilt and depression, as well as separation and individuation issues with respect to their parents (Felsen, Citation1998). The findings in this research suggest that a ‘third‐generation profile’ may be a similar approach through which to characterise some of the experiences of survivors’ grandchildren. Importantly, though, whereas much of the past literature has focused on how parenting styles and modes of communication within survivor families can impact descendants’ wellbeing (Juni, Citation2016; Scharf & Mayseless, Citation2011), in the present research parenting did not emerge as a predominant pathway through which trauma was transmitted to the third‐generation descendants. Contrary to findings in studies that have focused on second‐generation children of survivors (Wiseman & Barber, Citation2008), the participants’ engagement with the Holocaust was not significantly mediated by patterns of parental, or grandparental, communication; instead, their engagement with their grandparents’ Holocaust stories was mostly self‐initiated, marked by personal research, judicious reflection and trips to Holocaust sites. This finding may be an effect of their generational context of growing up in an environment in which knowledge about the Holocaust has entered mainstream discourse (Moskowitz, Citation2015).

In feeling highly connected to their grandparents’ stories of suffering and survival, the participants were found, on the whole, to be motivated to engage with their family histories, while committing themselves to sustaining these narratives into the future. The participants’ active, and, for some, ‘obsessive’, search for information is in sharp contrast to the ‘conspiracy of silence’ surrounding the Holocaust that characterised the decades following the war (Bar‐On, Citation1995). Rather, this ‘silence’ appears to have been circumvented by a plethora of Holocaust literature and discourse available to the third‐generation offspring (Solomon, Citation1998) and integrated into their self‐identity. Critically, while this Holocaust identity was used as a discriminator between themselves and non‐Holocaust descendants, the participants also spoke of using their identity as survivors’ descendants as a framework through which to ethically situate themselves in relation to contemporary political and social issues (e.g., asylum seekers).

Ultimately, it was revealed that the participants’ Holocaust heritage was formative in their lives, as echoes of their grandparents’ Holocaust trauma were shown to reverberate loudly throughout various elements of their identities. By considering these impacts through the dual lenses of social identity and diaspora identity theory, the analysis reveals how the participants define themselves in a collective manner as part of a group of Holocaust survivors’ descendants. The concept of diaspora was initially used to describe the forced dispersions of Jews and Armenians who maintained strong identification with their homelands and distinct group identities through community boundaries shaped by hostile responses in places of settlement (Baron, Citation2017; Drzewiecka, Citation2002). Here, the notion of diaspora is useful as a way of elucidating how the participants’ continued attachment to their families’ Holocaust past affects their present‐day lived experiences in Australia, given that one of the constitutive criteria of diaspora groups is ‘boundary‐maintenance’, which involves a group's preservation of a distinctive identity vis‐à‐vis a host society (Brubaker, Citation2005, p. 6).

Importantly, family legacies were found to play a central role in the participants’ lives; although they do not necessarily view themselves as ‘survivors’, their identification as grandchildren of survivors provides them with a post‐Holocaust identity that is an important part of their self‐definition. This identification reflects an engagement with the Holocaust that is not mediated or endorsed by the broader Australian culture, as it is in Israeli public and political life (Lazar et al., Citation2008). Rather, it is an identity that appears to be assumed by the participants on an individual, familial and group level, as reflected by their collective definition as survivors’ descendants according to the principles of social identity theory (Matz, Vogel, Mattar, & Montenegro, Citation2015; Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979).

Transferability and future research

All six participants were born and raised in Sydney, with five having attended Jewish high schools. Moreover, three of the participants referenced their attendance at Jewish community events held for third‐generation Holocaust descendants. The participants thus represent a sample of Jewish individuals who are affiliated with the Australian Jewish community and have at least some degree of involvement in Holocaust‐related communal activity. Future studies would benefit from studying a more diverse sample of descendants who are better representative of the scope of young Australian Jewry, including unaffiliated Jews who did not attend Jewish schools and who are less involved in the mainstream Jewish community, in order to further investigate how Holocaust trauma might impact a more socially varied sample of Holocaust descendants. Moreover, by looking more deeply at grandchildren of survivors of other extreme traumas, we will continue to expand understandings of how historical trauma can impact descendants across different groups.

CONCLUSIONS

This study suggests that the phenomenological expression of transgenerational trauma is not entirely homogenous between second‐ and third‐generation descendants. For example, the experiences of third‐generation descendants are heavily influenced by their active connection with the Holocaust; these individuals have sought knowledge and understanding of their grandparents’ experiences via avenues additional to grandparent narratives, therefore overcoming the ‘conspiracy of silence’ evident in the previous generation's often more passive Holocaust exposure. The participants accounts suggest that their families’ Holocaust histories provide them with ethical framework in relation to the contemporary suffering of other groups, and these findings are consistent with the previous literature that suggests third‐generation Holocaust descendants are thoughtful, empathic individuals who value social justice (Chaitin, Citation2002; Hogman, Citation1998).

The present study is one of a limited number examining third‐generation descendants of Holocaust survivors, and certainly the first of its kind in Australia. The themes presented here share some similarities with those of other third‐generation studies in so far as the diagnostic symptomology of trauma‐related disorders do again appear here in this research as they have been spoken about by Juni (Citation2016) and Yaroslawitz et al. (Citation2015). However the mechanisms of such transferability as decidedly different in the present research presumably due to the Holocaust not being represented in Australia as part of the country's fabric and therefore these participants have elected to be active in researching, learning, and cultivating the histories of their grandparents and the Holocaust more generally. Consequently, a unique outcome of this study is juxtapositioning experienced by these third‐generation descendants living in Australia as they attempt to reconcile a post‐Holocaust positioning that is not immediately reconcilable with their Australian national identity. This finding is considerably different to that presented in studies from Israel and other Holocaust descendent communities. Ultimately, for the participants here, their Holocaust identity was privileged, suggesting a deep connection with the traumatic experiences of their grandparents which speaks to how the echoes of their grandparent's traumas continue to be felt some 80 years later.

References

- American Psychological Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Barel, E., van Ijzendoorn, M. H., Sagi‐schwartz, A., & Bakermans‐kranenburg, M. J. (2010). Surviving the Holocaust: A meta‐analysis of the long‐term sequelae of a genocide. Psychological Bulletin, 136(5), 677–698. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020339

- Bar‐on, D. (1995). Fear and hope: Three generations of the Holocaust. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bar‐on, D., Eland, J., Kleber, R. J., Krell, R., Moore, Y., Sagi, A., … van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (1998). Multigenerational perspectives on coping with the Holocaust experience: An attachment perspective for understanding the developmental sequelae of trauma across generations. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 22(2), 315–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/016502598384397

- Baron, I. Z. (2017). The contradictions of Dispora: A reflective critique of the Jewish Dispora's relationship with Israel. Journal of International Political Theory, 14(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1755088217741322

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research. London, England: Sage Publications.

- Brubaker, R. (2005). The ‘diaspora’ diaspora. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 28(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141987042000289997

- Burchert, S., Stammel, N., & Knaevelsrud, C. (2017). Transgenerational trauma in a post‐conflict setting: Effects on offspring PTSS/PTSD and offspring vulnerability in Cambodian families. Psychiatry Research, 254, 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.04.033

- Chaitin, J. (2002). Issues and interpersonal values among three generations in families of Holocaust survivors. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 19(3), 379–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407502193005

- Danieli, Y. (1998). International handbook of multigenerational legacies of trauma. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

- Dawidowicz, L. (1986). The war against the Jews: 1933–1945. New York, NY: Bantam.

- de Graaf, T. K. (1998). A family therapeutic approach to transgenerational traumatization. Family Process, 37, 233–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.1998.00233.x

- Diller, J. V. (2003). Cultural diversity: A primer for the human services. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- Drzewiecka, J. A. (2002). Reinventing and contesting identities in constitutive discourses: Between diaspora and its others. Communication Quarterly, 50(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463370209385643

- Elon, A. (1981). The Israelis: founders and sons. Tel Aviv, Israel: Adam Publishers.

- Felsen, I. (1998). Transgenerational transmission of effects of the Holocaust: The North American research perspective. In Y. Danieli (Ed.), International handbook of multigenerational legacies of trauma. (pp. 43–69). New York, NY: Plenum.

- Giladi, L., & Bell, T. S. (2013). Protective factors for intergenerational transmission of trauma among second and third generation Holocaust survivors. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 5(4), 384–391. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028455

- Graham, D. (2014). The Jewish population of Australia: Key findings from the 2011 census. Darlinghurst, Australia: JCA.

- Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence from domestic abuse to political terror. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Hogman, F. (1998). Trauma and identity through two generations of the Holocaust. Psychoanalytic Review, 85, 573–578.

- Jilovsky, E., Silverstein, J., & Slucki, D. (Eds). (2015). In the shadows of memory. London: Vallentine Mitchell.

- Juni, S. (2016). Second‐generation Holocaust survivors: Psychological, theological, and normal challenges. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 17(1), 97–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2015.1064506

- Kellermann, N. P. F. (2001a). Psychopathology in children of Holocaust survivors: A review of the research literature. Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences, 38(1), 36–46. Retrieved from. http://peterfelix.tripod.com/home/Psychopathology.pdf

- Kellermann, N. P. F. (2001b). Transmission of Holocaust trauma: An integrative review. Psychiatry, 64(3), 256–267. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.64.3.256.18464

- Lazar, A., Litvak‐hirsch, T., & Chaitin, J. (2008). Between culture and family: Jewish‐Israeli young adults relation to the Holocaust as a cultural trauma. Traumatology, 14(3), 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765608320332

- Matz, D., Vogel, E. B., Mattar, S., & Montenegro, H. (2015). Interrupting intergenerational trauma: Children of Holocaust survivors and the third Reich. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 46(2), 185–205. https://doi.org/10.1163/15691624-12341295

- Moskowitz, G. (2015). Grandsons of the Holocaust: Contemporary maleness and post‐traumatic meaning. In E. Jilovsky, J. Silverstein, & D. Slucki (Eds.), In the shadows of memory. (pp. 53–76). London, England: Vallentine Mitchell.

- Niederland, W. G. (1968). The problem of the survivor: The psychiatric evaluations of emotional problems in survivors of Nazi persecution. In H. Krystal (Ed.), Massive psychic trauma. (pp. 8–22). New York, NY: International University Press.

- Rowland‐klein, D., & Dunlop, R. (1998). The transmission of trauma across generations: Identification with parental trauma in children of Holocaust survivors. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 31, 358–369. https://doi.org/10.3109/00048679809065528

- Sagi‐schwartz, A., van Ijzendoorn, M. H., & Bakermans‐kranenburg, M. J. (2008). Does intergenerational transmission of trauma skip a generation? No meta‐analytic evidence for tertiary traumatization with third generation Holocaust survivors. Attachment and Human Development, 10(2), 105–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730802113661

- Scharf, M., & Mayseless, O. (2011). Disorganizing experiences in second‐ and third‐generation Holocaust survivors. Qualitative Health Research, 21(11), 1539–1553. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732310393747

- Shaw, R. (2010). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In M. A. Forrester (Ed.), Doing qualitative research in psychology. (pp. 177–201). London, England: Sage Publications.

- Smith, J. A., & Osborn, M. (2008). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In J. A. Smith (Ed.), Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to methods. (2nd ed., pp. 53–80). London, England: Sage Publications.

- Solomon, Z. (1998). Transgenerational effects of the Holocaust: The Israeli research perspective. In Y. Danieli (Ed.), International handbook of multigenerational legacies of trauma. (pp. 69–83). New York, NY: Plenum Press.

- Starman, H. (2006). Generations of trauma: Victimhood and the perpetuation of abuse in Holocaust survivors. Historical Anthropology, 17(4), 327–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/02757200600916172

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations. (pp. 34–47). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

- van Ijzendoorn, M. H., Bakermans‐kranenburg, M. J., & Sagi‐schwartz, A. (2003). Are children of Holocaust survivors less well‐adapted? A meta‐analytic investigation of secondary traumatization. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 16, 459–469. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025706427300

- Wiseman, H., & Barber, J. P. (2008). Echoes of the trauma. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Yardley, L. (2008). Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods. London, England: Sage Publications.

- Yaroslawitz, S., Degrace, B., Sloop, J., Arnold, S., & Hamilton, T. (2015). A study of family health in Chareidi second and third generation survivors of the Holocaust. Work, 50(3), 501–510. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-141961

- Yehuda, R., Daskalakis, N. P., Bierer, L. M., Bader, H. N., Klengel, T., Holsboer, F., & Binder, E. B. (2016). Holocaust exposure induced intergenerational effects on FKBP5 methylation. Biological Psychiatry, 80(5), 375–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.08.005

- Yehuda, R., Halligan, S. L., & Grossman, R. (2015). Childhood trauma and risk for PTSD: Relationship to intergenerational effects of trauma, parental PTSD, and cortisol excretion. Development and Psychopathology, 13, 733–753. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579401003170