Abstract

Objective

Red may increase perceptions of sexual intent and the sexual attractiveness of women. As such, red is purported to serve a function in sexual attraction, although findings have been mixed. Individual differences in observers can affect the perception of sexual intent. One of these individual differences (i.e., sub‐clinical schizotypy) has not been investigated in relation to the perceived sexual intent of women wearing red, hence this was addressed.

Method

This study involved 72 men and 144 women, recruited to complete an online survey. Participants completed a schizotypy symptom scale, and rated women wearing red and green dresses on sexual desire, sexual receptivity, and sexual attractiveness.

Results

In line with the hypothesis, increases in schizotypy scores were associated with increased perception of sexual interest (summed ratings of sexual desire and sexual receptivity) for the model wearing the red dress more so than the green dress. However, no main effect of colour was observed.

Conclusions

Individuals high in schizotypy showed an exaggerated perception of sexual interest for women wearing red, implying that intentionality biases in schizotypy could be extended to the perception of sexual intent. The effect of colour on sexual intent perception may be dependent on measurement of individual variation.

What is already known about this topic

Mixed findings have been presented previously on the effect of colour on perception of sexual intent in women.

Individual variation in participants can affect the perception of intent.

Schizotypy is associated with perceiving intent in others’ behaviour.

What this topic adds

The main effect of colour did not influence the perceived sexual intent of women.

Accounting for schizotypy variation revealed an effect of colour.

The perception of intentionality in others’ as a characteristic of schizotypy may be extended to the perception of sexual intent.

In many non‐human primates, female displays using the colour red act as a signal of sexual receptivity for potential mates (see Dixson, Citation1983). Red may also serve a role in sexual attraction in human females. For example, it has been shown that women (1) prominently display red in online dating profile pictures when they are interested in casual sex (Elliot & Pazda, Citation2012), (2) choose to wear a red shirt (rather than a green or blue shirt) when expecting to converse with an attractive male (Elliot, Greitemeyer, & Pazda, Citation2013), and (3) are more likely to wear red when in the most fertile phase of the menstrual cycle (Beall & Tracy, Citation2013).

Women's use of the colour red can also influence an observer's behaviour and perception. For example, women's red clothing (1) increases men's self‐reported likelihood of engaging in mate‐guarding behaviours, such as unannounced visits ‘to see what she is doing’ (Prokop & Pazda, Citation2016), (2) enhances men's perceptions of women's attractiveness and sexual desirability (Elliot & Niesta, Citation2008), (3) increases both women's (Pazda, Prokop, & Elliot, Citation2014) and men's (Pazda, Elliot, & Greitemeyer, Citation2012) perception of sexual receptivity, and (4) increases competitor derogation (e.g., rating a competitor as promiscuous) in other women (Pazda et al., Citation2014). Red can also be used by women to increase the chances that a male will engage with them. For example, Guéguen and Jacob (Citation2012) showed that female waiters who wore red received more tips from male patrons than did female waiters wearing other colours. Similarly, female hitchhikers’ who wore red (compared with other colours) solicited more offers of a ride from male drivers (Guéguen, Citation2012). Thus, there is evidence suggesting that red clothing influences both men's and women's perception of a woman's sexual intent, and increases the behavioural engagement of men with women who wear red.

The assertion is that since women have a higher chance of wearing red on days when the risk of conception is high, it is likely that red clothing serves as a signal of fertility (Beall & Tracy, Citation2013), and thus a proxy for the absence of a sexual receptivity signal apparent in some primates. Importantly, though, recent research has brought this assertion into question. For example, and in contrast to the findings of Elliot and Niesta (Citation2008), Peperkoorn, Roberts, and Pollet (Citation2016) found no effect of clothing colour on the perceived attractiveness of women. In addition, and in contrast to Guéguen and Jacob (Citation2012), Lynn, Giebelhausen, Garcia, Li, and Patumanon (Citation2013) failed to find an effect of female waiters’ clothing colour on men's tipping behaviour. Finally, and in contrast to Beall and Tracy's (Citation2013) findings, Blake, Dixson, O'Dean, and Denson's (Citation2017) research calls into question whether a reliable relationship exists between hormonal variation across the menstrual cycle and the use of red clothing. Others have questioned the veracity of the red‐effect using logical and methodological arguments (e.g., Francis, Citation2013), as well as empirical ones (e.g., Hesslinger, Goldbach, & Carbon, Citation2015). Thus, the claim that red acts as a sexual signal in humans, and has correlated effects on (1) a viewer's perception of a woman's sexual intent, and (2) men's engagement with women who wear red, is one that requires further exploration and clarification. Here, we explore the perception of sexual intent of women, using a repeated‐measures design, with dress colour (red or green) as the independent variable, the specific combination of which has not been explored. Examining the various combinations of colour manipulation and experimental design on perceptions of others can help clarify the limits of the effect of red on perceptions of others.

Interestingly, characteristics of the perceiver can change perceptions of sexual intent in others. For example, male observers are more likely than are female observers to perceive sexual intent in a female actor's behaviour (Abbey, Citation1982; Farris, Treat, Viken, & McFall, Citation2008), and Koukounas and Letch (Citation2001) showed that a male's preoccupation with sex and reduced sociosexual effectiveness (i.e., an inability to accurately interpret nonverbal cues in social interactions) were associated with inferring greater sexual intent in female actors. Farris, Viken, Treat, and McFall (Citation2006) found, among other things, that men considered at high‐risk of committing sexual violence were less capable of interpreting women's cues (e.g., friendly, rejecting) than men considered low‐risk. Similarly, Farris, Viken, and Treat (Citation2010) found that high‐risk, relative to low‐risk, men were less able to distinguish between women's ‘friendly’ and ‘sexual interest’ cues. One, seemingly overlooked, area of potential interest here is the role of personality characteristics (e.g., schizotypy) in perceptions of sexual intent. Schizotypal Personality Disorder (SPD) is characterised by deficiencies in social and interpersonal relationships, cognitive or perceptual distortions, and eccentricities of behaviour (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). People high in schizotypal traits have similar deficits to, but milder deficits than, those individuals diagnosed with Schizophrenia (Burns, Citation2004). That said, the traits common to both disorders exist at sub‐clinical levels in the general population, suggesting that schizotypal traits lie on a continuum.

One reason that schizotypy symptoms are interesting in relation to sexual intent perception is because of the intentionality bias (i.e., the tendency for people to interpret the behaviour of others as intentional when no intention exists). Moore and Pope (Citation2014) demonstrated that individuals scoring higher on a schizotypy scale, relative to those scoring lower, were more inclined to attribute intention to pre‐recorded hand movements when there was none. Similarly, White, Borgan, Ralley, and Shergill (Citation2016) showed that individuals with schizophrenia had a greater tendency, than matched controls, to infer intentionality from the ambiguous hand movements of other individuals. Thus, schizotypy is associated with increased perception of intent in others’ actions. Given that perception of sexual intent relates to the extent to which we perceive others’ behaviour as denoting intention to engage in sexual behaviour (and consequently may serve a mating function by increasing approach behaviour; Choi & Hur, Citation2013), it is possible that those scoring higher on a measure of schizotypy have an increased perception of sexual intent in others, relative to those scoring lower. Hence, we aimed to determine whether schizotypy symptoms would increase sexual intent perception. If red is a signal of sexual intent, as claimed in previous studies, then those individuals high in schizotypy may perceive the act of wearing red as an intentional display of sexual interest. As such, schizotypy symptoms should exaggerate the perceptual difference between red and green, if one does exist.

To summarise, in light of conflicting findings in the literature, we aimed to re‐examine whether clothing colour (i.e., red) and gender affect the perception of sexual interest in women. Finally, in order to investigate personality characteristics, we examined how schizotypy affected sexual interest perception. We attempted to achieve this by asking participants to (1) complete a questionnaire assessing schizotypy symptoms, and (2) rate two images of women (wearing red and green dresses) on desire to have sex and sexual receptivity. Consistent with Elliot and Niesta (Citation2008), we hypothesised that if sexual intent is signalled by red clothing, then models wearing red would be perceived as being higher in sexual interest than those wearing green, and that men would have higher sexual interest perception than women. Furthermore, and given findings relating to the intentionality bias, we hypothesised that participants high in schizotypy would perceive women as having more sexual interest than would those low in schizotypy, regardless of dress colour. Finally, we thought that schizotypy would moderate the effect of clothing colour on perceptions of sexual interest, with higher sexual interest ratings for red dresses (compared with green dresses) as schizotypy scores increased. If red clothing is not a proxy for the absence of a sexual receptivity signal, then we might expect no difference between red and green clothing and no interaction between schizotypy and colour on sexual interest perception.

METHODS

Participants

A convenience sample of 216 participants took part in the study. The sample consisted of 72 (33%) men and 144 (67%) women, with ages ranging from 18 to 63-years (M = 31.13-years, standard deviation (SD) = 11.08). The University's ethics committee approved the study and all participants provided informed consent prior to taking part in the study.

Stimuli and materials

Participants were recruited via advertisements posted on social media (e.g., Facebook and Twitter). Social media users were invited to share the online invitation, and thus snowballing was also used. The survey was part of a larger study hosted on SurveyMonkey. Participants completed a demographics questionnaire, the Schizotypy Personality Questionnaire (SPQ; Raine, Citation1991), and a stimulus rating task. Demographics included questions about age and sex. The SPQ is a 74‐item questionnaire that measures thoughts and feelings across nine domains (Ideas of Reference, Excessive Social Anxiety, Unusual Perceptual Experiences, Odd or Eccentric Behaviour, No Close Friends, Odd Speech, Constricted Affect, and Suspiciousness). Participants respond to statements such as ‘I rarely laugh or smile’ and ‘I often feel that others have it in for me’ on 5‐point Likert scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Sub‐scale scores are taken as the average of responses to items on the relevant sub‐scale, while the total SPQ score is the average of all items. Higher scores indicate higher levels of schizotypy symptoms. The SPQ has high internal reliability (α = 0.90; Raine, Citation1991), and demonstrated high internal reliability in our study (α = 0.97).

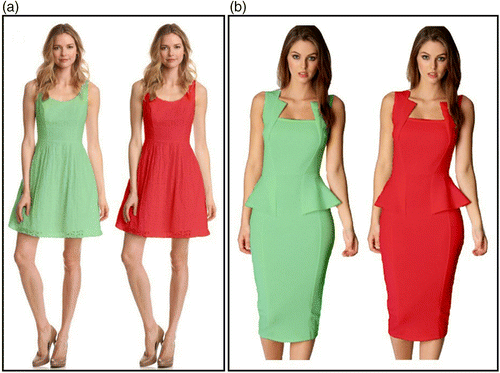

The stimulus rating task was created by choosing two images from a copyright‐free Internet database. The images were of two women wearing white dresses. Dress colours were digitally manipulated to appear red or green (as shown in Fig. 1). Participants were presented with both a red‐dress stimulus and a green‐dress stimulus, but the women in the images were different. That is, if participants saw Model A in red, they would see Model B in green. The order in which the red‐green stimuli appeared was counterbalanced across participants. For each stimulus, participants were asked to rate how much they agreed with the statements ‘This woman is interested in sex’ (sexual desire), ‘This woman would accept an offer of sex from a stranger’ (sexual receptivity), and ‘This woman is sexually attractive’ (sexual attractiveness) on scales from 1 (not at all) to 9 (very much).

Procedure

Participants accessed the survey via a link provided in the recruitment materials. After answering the demographic questions, all participants answered a series of unrelated questionnaires (which comprise part of another study). Participants then completed the stimulus rating task, and finally the SPQ. Total participation time was approximately 30-min.

RESULTS

The mean scores for each of the ‘sexual intent’ questions, for participants responding to red and green dress colour, are presented in Table . Preliminary analyses revealed that responses to each of these questions violated assumptions of normality, and thus responses to the sexual receptivity and sexual desire items were summed to form a single scale, which we labelled ‘sexual interest’.Footnote1 While this summed scale was still slightly skewed (green skewness = 0.51, SD = 0.17; red skewness = 0.37, SD = 0.17), F‐tests (e.g., analysis of variance (ANOVA)) are robust against slight violations of normality (see Keppel & Wickens, Citation2004), and so we continued with an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA).

Table 1. Mean scores (and SD) on the three sexual intent questions for participants responding to women wearing red and green dresses

Firstly, the difference between red and green perceptions were investigated using a t‐test. This test revealed that colour did not have a significant effect on sexual interest scores (t(215) = 0.41, p = .685), and thus neither the hypothesis nor the standard red‐effect were supported. We next investigated the effect of gender in a 2 (colour: red vs green) × 2 (gender: men vs women) ANOVA. No effects were evident here (all p > .05) which, again, is inconsistent with the hypothesis.

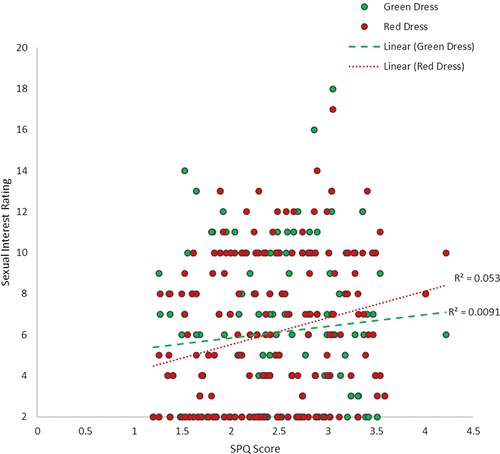

The correlation between SPQ scores and the sexual intent scores of participants was significant (r(214) = .185, p = .006), which was in line with the hypothesis. As such, we included schizotypy scores as a covariate in the 2 (colour) × 2 (gender) ANCOVA model. Although the main effect of colour was significant in this model (F(1, 213) = 4.71, p = .031, ηp2 = . 020), with women in red dresses (M = 6.18, standard error (SE) = 0.24) rated as more interested in sex than women in green dresses (M = 6.12, SE = 0.26), this result is an artefact of including schizotypy in the model, given the lack of significance in the t‐test. Importantly though, there was also a significant interaction between schizotypy scores and dress colour (F(1, 213) = 5.57, p = .019, ηp2 = . 025). As shown in Fig. 2, as SPQ scores increased, the perceived sexual interest of women wearing red dresses increased (r = .23, p = .001), relative to the marginal increase in sexual interest scores for women wearing green dresses (r = .12, p = .068). Using Cocor (Diedenhofen & Musch, Citation2015) to compare the correlations, with an overlapping, matched sample and a two‐tailed test, the red dress r‐value was significantly higher than the green dress r‐value (z = 2.56, p = .010). Given this, it is clear that the association between schizotypy and sexual interest was stronger in the red dress condition than it was in the green dress condition. Gender remained a non‐significant contributor to sexual intent perception scores, and SPQ scores did not interact with gender.

DISCUSSION

We failed to observe the expected effect of dress colour on sexual interest ratings. Previous research (e.g., Pazda et al., Citation2012, Citation2014) has demonstrated that women wearing red are perceived to be more sexually receptive than are women wearing other colours. While a majority of research findings have demonstrated that red affects people's perceptions of, and behaviour in relation to, others, the findings are not equivocal. For example, in an attempt to replicate and extend Guéguen and Jacob's (Citation2012) findings, Lynn et al. (Citation2013) failed to find an effect of female waiters’ clothing colour on men's tipping behaviour. Other researchers have also noted non‐significant findings, publication bias, and power issues (see Francis, Citation2013). Several suggestions have been put forward in an attempt to explain the failure to replicate the red‐effect, including how red has been used (i.e., manipulation of t‐shirt colour, background colour, accessory colour), as well as the comparison colours used (e.g., blue, black, green). This study adds to the growing body of literature showing that red may influence people's perceptions, however the red‐effect is likely moderated by variation in individuals’ personalities. To express this in another way, it seems as though the association between red and sexual intent is weak, and as individuals high in schizotypy have a tendency to infer intentionality in people's actions, this weak effect is amplified after controlling for individual variation.

In relation to this point, and consistent with the hypothesis, a significant increase in sexual interest ratings was observed for the red dress, but not the green dress, as scores on the schizotypy measure increased. Furthermore, the correlation between schizotypy scores and the sexual interest scores was positive. It is thought that a characteristic of schizotypy is the perception of intent in others’ behaviour where no such intent exists (see Moore & Pope, Citation2014; White et al., Citation2016). The results of the present study suggest that this cognitive bias can be extended to perceptions of sexual intent in others. Specifically, including schizotypy in the model demonstrated that people find women wearing red to be more sexually receptive than when the same women wear green, where this was not observed as a main effect (Elliot & Pazda, Citation2012). Thus, those higher in schizotypy perceived women in the red dress to be increasingly more receptive than women in the green dress and, when schizotypy was controlled for, a main effect of colour on sexual intent perception was revealed. An explanation for this finding is provided above, but we could also speculate that individuals high in schizotypy made a naïve hypothesis about the experiment, and responded accordingly (that is, guessed that the woman in red should be rated as being more sexually receptive). In this way, their perception of intentionality may have been in the experimenters’ intentions, rather than in the perception of sexual interest. Although this is unlikely, it needs to be further explored.

Considering possible explanations for our null effect of dress colour, it is important to note that most of our participants were women (n = 144; 67%), who do not benefit in the same way as men do from the perception of sexual intent in other women (Haselton, 2003). However, Pazda et al. (Citation2014) demonstrated that exposing women to another woman wearing red (compared with white) increased competitor derogation. Specifically, women were more likely to state that the woman would cheat on men. We might then expect that female participants would rate the women in red as being higher in intentions to accept sex from a stranger than the women in green. However, no effect of gender was observed, nor was there an interaction between gender and colour. Importantly, and a limitation that should be addressed in future research, we did not measure the participants’ sexual orientation. Homosexual women appear to engage in less derogation of competitors than heterosexual women (VanderLaan & Vasey, Citation2008), and thus may have rated the women in red as equally interested in sex as those in green. However, while this is an important factor to consider, it is unlikely that more than a small percentage of women in the sample were exclusively homosexual, and hence this effect is unlikely to be the cause of our non‐significant finding.

Some limitations must be addressed. In most research investigating the effects of colour on sexual perception, participants are presented with red or another colour (e.g., Elliot & Niesta, Citation2008; Elliot, Tracy, Pazda, & Beall, Citation2013; Pazda et al., Citation2012, Citation2014; Schwarz & Singer, Citation2013), thus participant's first and only impressions are recorded. Here, we presented participants with both colours (i.e., a repeated‐measures design). Despite the different models used to present the colours, participants may have guessed that we were interested in their perceptions of red versus green, and rated the woman in the green dress as being as interested in sex as the woman in red (i.e., guessed that the woman in red should be rated as more sexually receptive, but took a negative‐participant role). However, this assumes that all participants (i.e., not just those higher in schizotypy) made the same naïve hypothesis (i.e., had some innate understanding of the red‐effect), but those higher in schizotypy responded differently from other participants. In addition, making a relative judgement about the sexual interest of an individual, rather than an absolute judgement, is more akin to real‐world interactions. That is, we are rarely presented with one alternative but, instead, have to decide which of a group of people we would be most likely to approach. If the effect of colour on sexual intent perception is limited to sequential rather than simultaneous presentation, then this implies a limitation in the strength, and therefore the ecological validity, of the effect.

In addition, we compared red with green, but red may not always increase perceptions relative to other colours, such as black (see, for example, Roberts, Owen, & Havlicek, Citation2010). Given the colours we used did not induce the typical ‘red is sexy’ finding, comparison colours other than the green we chose should be examined. In addition, a replication of this study with different models varying on a range of characteristics (e.g., attractiveness and age) is warranted to further explore the boundaries of the interaction between schizotypy and clothing colour.

Another potential issue is that the scales used to rate the stimuli on the three sexual interest questions were Likert scales, and demonstrated deviations from normality. As such, two of these ratings were summed. Future research could address this concern by using broader rating scales; perhaps visual analogue scales (VAS; see Crichton, Citation2001, for an outline of the benefits of VAS). Relatedly, and given that red dresses may increase the attractiveness ratings made by men but not by women (see Elliot & Niesta, Citation2008), assessing the ratings of sexual desire, sexual receptivity, and sexual attractiveness separately is important. Finally, the stimuli used in this study were static, whereas in earlier studies (i.e., Moore & Pope, Citation2014; White et al., Citation2016) the intentionality bias occurred when a person was exposed to the movement of another individual. The use of recorded, dyadic interactions could modify the effect of clothing colour on perceptions of sexual intent, particularly for those individuals high in schizotypy.

While further research is warranted, the results of the study reported here importantly indicate that individual differences may moderate the effect of red clothing on perceptions of a woman's sexual interest. Individual differences have only been explored briefly in previous research (e.g., the age of participants; Schwarz & Singer, Citation2013). We have shown that schizotypy moderates the relationship between red and the perceived sexual interest of others. Specifically, those individuals scoring high on a measure of schizotypy are more likely to perceive sexual interest in women wearing red dresses than are those scoring lower on this measure. However, individuals (i.e., those scoring high and low on the schizotypy measure) did not differ as greatly in their ratings of the sexual interest of women in green dresses. Exploring the extent to which other individual differences impact the influence of colour on people's perceptions of women may go some way to understanding conflicting findings in the literature. The results therefore add to a growing body of research highlighting the associations between visual information (i.e., colour) and sexual attraction.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was not funded. The authors thank David Van Doorn for assistance with stimulus preparation.

Notes

1. As ‘sexual attractiveness’ does not denote a woman's ‘intent’ to have sex (i.e., it is a rating of how attractive a participant finds the woman in each stimulus), it was not included in the summed ‘sexual interest’ variable. Furthermore, as the ‘sexual attractiveness’ data was highly skewed, it was not analysed. As such, this variable will not be referred to again.

REFERENCES

- Abbey, A. (1982). Sex differences in attributions for friendly behavior: Do males misperceive females' friendliness? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42(5), 830–838.

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (Vol. 5). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Beall, A. T., & Tracy, J. L. (2013). Women are more likely to wear red or pink at peak fertility. Psychological Science, 24(9), 1837–1841. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613476045

- Blake, K. R., Dixson, B. J., O'dean, S. M., & Denson, T. F. (2017). No compelling positive association between ovarian hormones and wearing red clothing when using multinomial analyses. Hormones and Behavior, 90, 129–135.

- Burns, J. K. (2004). An evolutionary theory of schizophrenia: Cortical connectivity, metarepresentation, and the social brain. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 27(06), 831–855.

- Choi, E., & Hur, T. (2013). Is reading sexual intention truly functional? The impact of perceiving a partner's sexual intention on courtship initiation behaviors. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42(8), 1525–1533. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0153-6

- Crichton, N. (2001). Visual analogue scale (VAS). Journal of Clinical Nursing, 10, 706.

- Diedenhofen, B., & Musch, J. (2015). Cocor: A comprehensive solution for the statistical comparison of correlations. PLoS One, 10(4), e0121945.

- Dixson, A. F. (1983). Observations on the evolution and behavioral significance of ‘sexual skin’ in female primates. Advances in the Study of Behavior, 13, 63–106.

- Elliot, A. J., Greitemeyer, T., & Pazda, A. D. (2013). Women's use of red clothing as a sexual signal in intersexual interaction. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(3), 599–602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.10.001

- Elliot, A. J., & Niesta, D. (2008). Romantic red: Red enhances men's attraction to women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(5), 1150–1164. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.95.5.1150

- Elliot, A. J., & Pazda, A. D. (2012). Dressed for sex: Red as a female sexual signal in humans. PLoS One, 7(4), e34607. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0034607

- Elliot, A. J., Tracy, J. L., Pazda, A. D., & Beall, A. T. (2013). Red enhances women's attractiveness to men: First evidence suggesting universality. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(1), 165–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.07.017

- Farris, C., Treat, T. A., Viken, R. J., & Mcfall, R. M. (2008). Perceptual mechanisms that characterize gender differences in decoding women's sexual intent. Psychological Science, 19(4), 348–354.

- Farris, C., Viken, R. J., & Treat, T. A. (2010). Perceived association between diagnostic and non‐diagnostic cues of women's sexual interest: General recognition theory predictors of risk for sexual coercion. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 54(1), 137–149.

- Farris, C., Viken, R. J., Treat, T. A., & Mcfall, R. M. (2006). Heterosocial perceptual organization: Application of the choice model to sexual coercion. Psychological Science, 17(10), 869–875.

- Francis, G. (2013). Publication bias in ‘red, rank, and romance in women viewing men,’ by Elliot et al. (2010). Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 142(1), 292–296. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027923

- Guéguen, N. (2012). Color and women hitchhikers’ attractiveness: Gentlemen drivers prefer red. Color Research & Application, 37(1), 76–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/col.20651

- Guéguen, N., & Jacob, C. (2012). Clothing color and tipping: Gentlemen patrons give more tips to waitresses with red clothes. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 38(2), 275–280. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348012442546

- Haselton, M. G. (2003). The sexual overperception bias: Evidence of a systematic bias in men from a survey of naturally occurring events. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(1), 34–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00529-9

- Hesslinger, V. M., Goldbach, L., & Carbon, C. C. (2015). Men in red: A re‐examination of the red‐attractiveness effect. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 22(4), 1142–1148.

- Keppel, G., & Wickens, T. D. (2004). Design and analysis: A researcher's handbook. (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice‐Hall.

- Koukounas, E., & Letch, N. M. (2001). Psychological correlates of perception of sexual intent in women. Journal of Social Psychology, 141(4), 443–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224540109600564

- Lynn, M., Giebelhausen, M., Garcia, S., Li, Y., & Patumanon, I. (2013). Clothing color and tipping: An attempted replication and extension. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 40(4), 516–524. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348013504001

- Moore, J. W., & Pope, A. (2014). The intentionality bias and schizotypy. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 67(11), 2218–2224.

- Pazda, A. D., Elliot, A. J., & Greitemeyer, T. (2012). Sexy red: Perceived sexual receptivity mediates the red‐attraction relation in men viewing woman. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(3), 787–790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2011.12.009

- Pazda, A. D., Prokop, P., & Elliot, A. J. (2014). Red and romantic rivalry: Viewing another woman in red increases perceptions of sexual receptivity, derogation, and intentions to mate‐guard. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40(10), 1260–1269. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167214539709

- Peperkoorn, L. S., Roberts, S. C., & Pollet, T. V. (2016). Revisiting the red effect on attractiveness and sexual receptivity: No effect of the color red on human mate preferences. Evolutionary Psychology, 14(4), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474704916673841

- Prokop, P., & Pazda, A. D. (2016). Women's red clothing can increase mate‐guarding from their male partner. Personality and Individual Differences, 98, 114–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.04.021

- Raine, A. (1991). The SPQ: A scale for the assessment of schizotypal personality based on DSM‐III‐R criteria. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 17(4), 555–564.

- Roberts, S. C., Owen, R. C., & Havlicek, J. (2010). Distinguishing between perceiver and wearer effects in clothing color‐associated attributions. Evolutionary Psychology, 8(3), 350–364.

- Schwarz, S., & Singer, M. (2013). Romantic red revisited: Red enhances men's attraction to young, but not menopausal women. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(1), 161–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.08.004

- Vanderlaan, D. P., & Vasey, P. L. (2008). Mate retention behavior of men and women in heterosexual and homosexual relationships. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37(4), 572–585.

- White, T. P., Borgan, F., Ralley, O., & Shergill, S. S. (2016). You looking at me?: Interpreting social cues in schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine, 46(1), 149–160. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715001622