Abstract

Objective

To review available literature and identify the experimental evidence for effective treatment of depression in Indigenous populations worldwide.

Method

MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsychInfo, Informit, Psychology, and Behavioural Sciences databases were systematically searched for intervention studies from each database's inception to November 2016. Randomised controlled trials were included if they examined the effects of therapy for depression as primary or secondary outcome with Indigenous participants of any age group.

Results

This review found a total of four experimental trials (152 participants) worldwide studying the effect of behavioural and pharmacological interventions for depression in Indigenous populations. The quality of evidence was low to moderate. Results from three diverse interventions suggest that culturally specific cognitive and behavioural therapy may have the potential to reduce depressive symptoms in Indigenous young people. However, the evidence base is currently insufficient to offer sound conclusions. One trial studied the effect of dosage differences (75 vs 125 mg) of a tricyclic antidepressant, clomipramine, finding that Indigenous African patients may respond to treatment regimens at a lower dosage than recommended standard in western textbooks.

Conclusions

Findings from this review indicate potential for the use of culturally adapted behavioural interventions to target depression in Indigenous populations; however, current evidence is insufficient to confirm their effectiveness. Similarly, there is insufficient evidence to propose recommendations for effective pharmacological treatment for Indigenous people. A tentative finding, that lower doses of antidepressants might be effective for the Indigenous, compared to the general population, requires further investigation as it holds important implications for clinical practice. More rigorous experimental research with adequate sample sizes needs to be conducted to provide conclusive recommendations for adoption into standard care.

What is already known about this topic

Indigenous populations are considered at high risk of depression.

There is paucity of evidence for effective (culturally tailored) interventions.

Despite existing effective treatments for depression, minority groups are often not included in efficacy studies.

What this topic adds

This review is the first systematic review to summarise the current state of experimental research on treatment for depression in Indigenous populations.

The current evidence‐base is insufficient to offer sound conclusions to support the use of culturally adapted behavioural interventions. However, the findings show potential in using western treatment models (CBT) combined with Indigenous values and beliefs. It is worth noting that the trials included in this review were designed with the support and consultations of Indigenous people, and the overall score for participant satisfaction was rated as high; consequently improving treatment uptake and adherence.

Similarly, there is lack of evidence base to propose recommendations for effective pharmacological treatment for depression in Indigenous populations. However, a tentative finding that lower doses of antidepressants might be effective for Indigenous people, compared to the general population, requires further research with well‐powered trials. Paucity of evidence on the effectiveness of antidepressants for Indigenous people holds important implications for clinical practice.

Depression is a highly prevalent mental disorder (Waraich, Goldner, Somers, & Hsu, Citation2004) and a leading cause of disability worldwide (WHO, Citation2015). Depressive disorders place a significant burden on health and quality of life of individuals and are a huge societal burden, for instance due to reduced work performance and costs associated with lost productivity (Ferrari, Charlson, et al., Citation2013; Kessler & Bromet, Citation2013).

In the current literature, the prevalence rates for depression differ depending on a range of participant and methodological variables; however, the global point prevalence of major depressive disorder is estimated at 4.7%, with an annual incidence of 3.0% (Ferrari, Somerville, et al., Citation2013). The World Health Organisation's (WHO) projections based on prevalence trends indicate that by 2030 depression will no longer be the fourth, but the first cause of global disease burden in high‐income countries (Mathers & Loncar, Citation2006). A key explanation for the increasing burden of depression can be found in the estimated global treatment gap of 56.3%. Even in developed countries such as Australia, New Zealand, and the USA estimates of individuals not receiving treatment are 45%, 60%, and 72%, respectively.

These rates may be even higher for the Indigenous people residing in the above‐mentioned countries, given the many barriers to receiving treatment for depression in Indigenous populations worldwide (Gadalla, Citation2010; Isaacs, Pyett, Oakley‐Browne, Gruis, & Waples‐Crowe, Citation2010). Barriers specific to Indigenous people include a history of racism, discrimination, lack of trust in mainstream services, cultural and language miscommunication and inadequate measures to address stigma issues associated with mental illness. According to the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, there are 70 countries with approximately 300 million Indigenous people who live and retain distinct languages, culture, and beliefs (Hall & Patrinos, Citation2012). Keeping in mind that risk factors for developing depression include economic disadvantage, low education, exposure to violence, loss, grief, or chronic illness (Belmaker & Agam, Citation2008)—and that these risk factors are common among Indigenous people (Gracey & King, Citation2009; Zubrick et al., Citation2010)—it is not surprising that Indigenous populations are considered at high risk of depression (Arroll et al., Citation2009; Jorm, Bourchier, Cvetkovski, & Stewart, Citation2012). Existing studies rarely include Indigenous controls to allow prevalence comparisons. However, a recently published systematic review and meta‐analysis (Kisely et al., Citation2017) found that the rates of depressive disorders were not higher among the Indigenous people of the Americas, compared to non‐Indigenous groups. The study's results have to be considered with caution due to limitations such as a possible lack of accuracy when measuring the symptoms of depression with diagnostic tools not validated for use in Indigenous populations.

Untreated depression is associated with increased risk of early mortality, increased risk of suicide and elevated rates of hospitalisation (Balázs et al., Citation2006; Mayou, Hawton, Feldman, & Ardern, Citation1991; Wulsin, Vaillant, & Wells, Citation1999). Epidemiological studies show that the benefits of treating depression far outweigh the treatment costs and lead to improvements not only in health but also in economic outcomes such as large economic productivity gains (Chisholm et al., Citation2016). While research provides evidence for effective treatment options for depression in the general population, e.g., cognitive‐behavioural therapy (CBT) or interpersonal therapy (IT), alone and in combination with antidepressants (Huhn et al., Citation2014; McHugh, Whitton, Peckham, Welge, & Otto, Citation2013), western treatments are of uncertain effectiveness when applied in Indigenous contexts.

Currently research on effectiveness of various treatments for depression in Indigenous people is limited and data mostly stem from non‐randomised controlled trials. Indigenous health researchers have highlighted that interventions designed without consideration of different world‐views and different value systems of Indigenous populations will likely fail to meet treatment goals and will remain irrelevant (Turner & Kelly, Citation2000; Vicary & Westerman, Citation2004). Increasingly more studies and position papers have, therefore, called for the need for holistic culturally tailored interventions (Dudgeon, Milroy, & Walker, Citation2014; Vicary & Westerman, Citation2004) in order to improve treatment uptake and adherence. This is further reinforced by qualitative studies which confirm that western models of treatment do not sufficiently account for the Indigenous world‐view and cultural beliefs about mental illness (Dudgeon et al., Citation2012). As a result of colonisation practises, Indigenous people experience a wide range of psychological symptoms (e.g., grief, post‐traumatic stress disorder, separation from cultural and family ties, lack of cultural identity, substance abuse, violence). Moreover, they often experience limited access to health services and literacy or communication barriers. The non‐experimental Indigenous health research findings suggest that in light of these challenges, there is a need to develop culturally adapted psychological interventions that can be delivered in primary care settings (Brown, Abe‐Kim, & Barrio, Citation2003). In addition, Indigenous people may respond differently to pharmacotherapy, as has been shown in a study with non‐Caucasian patients, which further complicates treatment strategy and compliance (Schraufnagel, Wagner, Miranda, & Roy‐Byrne, Citation2006).

To date, limited evidence and no literature appraisal or systematic review has been available on the effects of psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy for treatment of depression in Indigenous populations around the world. Clinical practice guideline recommendations for treatment of depression in Indigenous people are non‐existent. Our review's aim is a response to this gap in knowledge, as guideline recommendations are based on systematic synthesis of available scientific evidence. Randomised controlled trials are less susceptible to biased conclusions compared to non‐experimental research methods. Therefore, this review aimed to summarise the current state of experimental research on treatment for depression among Indigenous populations worldwide, and had the goal to determine the potential effect treatment of depression may have on a number of associated outcomes. In addition, it also aimed to determine the potential cost‐effectiveness of treatment. Given the prevalence of depression and its impact on health and the quality of life, this review was undertaken with the intention to guide future intervention designs and clinical practice.

METHOD

The search strategy, inclusion criteria, primary and secondary outcomes and data synthesis methods for the present study were pre‐specified in the protocol registered and published on the Prospero database (Prospero ID 2016:CRD42016041957).

Inclusion criteria

Study design

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and controlled clinical trials (CCTs) were eligible for inclusion. Interventions were to focus on pharmacological therapies (e.g., first or second generation antidepressants), psychological therapies (e.g., CBT, family therapy, mindfulness therapy), or alternative therapies including natural‐product therapies, where treatment for depression was the primary or secondary outcome.

Setting

Indigenous populations from any setting were eligible for inclusion, such as in‐patient, out‐patient or primary care settings. We included studies with participants who were reported to be exclusively or primarily Indigenous to their country and were part of the main study population or a major subpopulation (> 60%). Ethnic classification was accepted as reported in the publications. No attempt was made to re‐identify or classify Indigenous status by the review authors.

Participants

Studies included participants across all ages who had a formal diagnosis of depression as determined by a qualified clinician according to a validated diagnostic criteria (e.g., DSM‐V) (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013), or participants who reached a predefined threshold on a validated diagnostic tool (e.g., Becks Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck, Steer, & Brown, Citation1996) or Children's Depression Inventory (CDI) (Kovacs, Citation1992)).

Exclusion criteria

No date, language or age restrictions were applied. Studies which did not focus on clinical improvements for depression in an Indigenous population were not included in the review.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure for this review was a change in depressive symptoms as measured by a validated diagnostic tool (e.g., BDI). Secondary outcomes included change in self‐perceived wellness, suicidal ideation, change in anxiety, change in ability to cope, change in the quality of life, and cost‐effectiveness of the intervention.

Data source and search process

A systematic literature search of electronic databases including: MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsychInfo, Informit Health Collection, and Psychology and Behavioural Sciences was conducted from database inception until November 2016. The key search phrases used were: ‘depression OR major depressive disorder OR depressive symptoms OR social‐and‐emotional‐wellbeing AND Aboriginal OR Indigenous OR Maori OR Native American OR tribal’. In order to extract relevant data from the papers, two authors (JP and JA) independently screened the titles and abstracts of potentially eligible studies. The full text articles were then independently examined by the two authors (JP and JA). Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion and the third author (KC) reviewed the data if a consensus was not researched. Reference lists of included relevant papers were hand‐searched to identify additional studies.

Study selection process

Two authors (JP and JA) independently extracted data using custom‐made extraction forms which included ‘assessing compliance with Indigenous health research guidelines within systematic reviews’ (MacLean, Ritte, Thorpe, Ewen, & Araben, Citation2015). Data on the following characteristics were extracted for each study identified for inclusion: design, sample size, participant characteristics, setting, intervention, comparators, outcomes, follow‐up period, Indigenous people's involvement in the research/intervention, limitations and strengths. Authors of abstracts and papers with missing data were contacted to retrieve further information.

Risk of bias in studies

Two authors (JP and JA) independently assessed the quality of the studies at the study‐level using the Cochrane Collaboration risk of bias tool (Higgins et al., Citation2011). The tool allows review authors to assess the risk of bias for seven elements of each study. The risk of selection bias is split into two categories focusing on ‘adequate random sequence generation’ and ‘allocation concealment’ of the randomisation sequence. ‘Blinding of participants and personnel’ and ‘blinding of outcome assessment’ aims to assess the risk of performance bias and detection bias respectively. “Incomplete outcome data” assesses the risk of attrition bias between the conditions in the study and ‘selective reporting’ assesses the presence of reporting bias. Finally a category of ‘free of other bias’ is included to indicate potential problems found in the study that may not be covered by the six aforementioned topics. Each topic can be graded as high, low or unclear risk of bias and is accompanied by specific reasons for the particular grading.

Data synthesis

Heterogeneity in methodology and sample populations of the included studies did not allow for meta‐analysis to be conducted. Therefore, the results are presented in the form of narrative synthesis. Where possible, outcomes are presented with measure of effect (e.g., mean difference) and variance (e.g., standard deviation (SD) as reported in the original paper).

RESULTS

Study characteristics

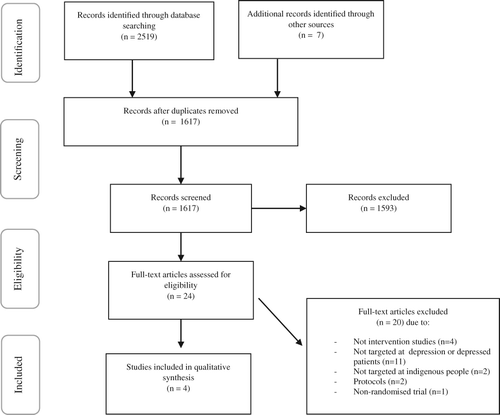

The systematic search identified a total of 2,519 citations (Fig. 1). Full text screening of 24 papers identified during abstract screening yielded a total of four studies for inclusion in the review synthesis; Table summarises the four included studies. Evidence for this review comes from four small RCTs. One study was conducted in New Zealand (Woods & Jose, Citation2011), two in the United States (Ginsburg et al., Citation2012; Listug‐Lunde, Vogeltanz‐Holm, & Collins, Citation2013) and one in Tanzania (Kilonzo et al., Citation1994). The four studies had a total of 152 participants, with small sample sizes for individual studies, ranging from 16 participants in the smallest trial to 56 participants in the largest. Two studies took place in local health services clinics, two in schools and one in a psychiatry department.

Table 1. Descriptive summary of included studies, summary of the main findings and their strengths and weaknesses

Studies differed in participant age categories with three studies recruiting children and young adults aged 11–19-years (Ginsburg et al., Citation2012; Listug‐Lunde et al., Citation2013; Woods & Jose, Citation2011) and one study recruiting adults >18-years (Kilonzo et al., Citation1994). Criteria for depression differed for each study. One study (Kilonzo et al., Citation1994) selected patients based on DSM‐III criteria for major depressive disorder and found an average moderate baseline level of depression as measured by the Bech‐Rafaelsen Melancholia Scale (MES) (Bech, Citation2002). Another study (Ginsburg et al., Citation2012) selected patients who reached the cut‐off of 16 points on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies‐Depression scale (CES‐D) (Weissman, Sholomskas, Pottenger, Prusoff, & Locke, Citation1977) indicating risk of depressive symptoms; where participants with MDD were excluded. Two studies focusing on children (Listug‐Lunde et al., Citation2013; Woods & Jose, Citation2011) used the CDI scale finding scores of 21 and 25 indicating moderate baseline depression.

The only study testing the effectiveness of pharmacological treatment was conducted by Kilonzo et al. (Citation1994) examining the effect of dosage differences (75 vs 125-mg) for the tricyclic antidepressant clomipramine among Black African Indigenous patients. All three of the psychological interventions utilised culturally adapted CBT‐based programs. Ginsburg et al. (Citation2012) compared culturally tailored CBT versus educational sessions for the prevention of postpartum depression in American Indians. Listug‐Lunde et al. (2013) compared small group sessions with treatment as usual. Finally, Woods and Jose (Citation2011) found that a culturally adapted training for small groups relying on cognitive‐behavioural and psycho‐educational techniques reduced depression symptoms in Maori and Pacific adolescents. The duration of psychological treatments in the studies varied between eight and 13 sessions. Follow‐up data collection varied between 1 month and 1 year for the psychological therapies, whereas the pharmacological intervention reported results for five follow‐up data collection points which were 3, 6, 20, 34, and 64-days post‐participant recruitment. All authors stated that the psychological interventions were designed through consultations with Indigenous leaders and the interventions were delivered by either an Indigenous health professional or a culturally trained health professional.

Outcome measures used

Ginsburg et al. (Citation2012) assessed depressive symptoms using the CES‐D (Weissman et al., Citation1977) and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) (Cox, Holden, & Sagovsky, Citation1987). The CES‐D scores depressive symptoms on a 4‐point‐Likert‐scale with score ranges of 0 to 60 while the EPDS has scores ranging from 0 to 30, with higher scores for both tests indicating more depressive symptoms. Listug‐Lunde et al. (2013) used the CDI (Kovacs, Citation1992) to measure depressive symptoms in youth. Raw scores of the CDI can be converted into t‐scores, with t‐scores at or above 65 being the cut‐off for showing clinically significant depressive symptoms. They also used the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC) (March, Parker, Sullivan, Stallings, & Conners, Citation1997) to test for anxiety, which similarly has a t‐score of 65 or above as cut‐off for clinically significant anxiety symptoms. Woods and Jose (Citation2011) used the CDI to indicate severity of depressive symptoms. Kilonzo et al. (Citation1994) used the MES to determine depression.

Risk of bias of included studies

The four included studies were rated to be at unclear or high risk of bias for the majority of bias types (Table ). Most studies did not provide sufficient information to allow assessment of risk of selection bias, with the exception of Listug‐Lunde et al. (2013) who provided an adequate description of their random sequence generation. Ginsburg et al. (Citation2012) and Kilonzo et al. (Citation1994) were at high risk of performance and detection bias as they were not blinded. The remaining two studies did not provide sufficient information to permit judgement. Woods and Jose (Citation2011) was assessed as being at high risk of attrition bias as a result of their per‐protocol analysis and substantial drop‐out in both groups. The three remaining studies were assessed to be at low risk of bias. None of the studies provided a protocol or trial registry, thus it was not possible to assess risk of reporting bias. No other biases were identified for any of the studies.

Table 2. Risk of bias for the included studies based on the Cochrane collaboration risk of bias assessment

Effectiveness of interventions

Reduction in depressive symptoms (primary outcome)

Ginsburg et al. (Citation2012) found that both CBT‐based treatment and education support program reduced depressive symptoms as measured by the CES‐D but not by the EPDS. Mean scores on the CES‐D in the CBT group decreased from 22.0 units (SD = 8.3) to 15.4 units (SD =9.33), p = <.05, while in the education‐support group mean scores decreased from 21.4 (SD = 7.4) to 10.9 (SD = 6.6), p < .005 at 24-week follow‐up. No significant between‐group differences were found in scores on CES‐D between baseline and 24-weeks for the CBT‐based group or the education‐support group (Table ). Listug‐Lunde et al. (2013) found significant reductions in scores on CDI immediately after the intervention and at 3‐month follow‐up. The baseline mean was 21.0 (SD = 5.3) with scores reduced to 14.4 (SD = 9.93, p < .05) at immediate post‐intervention follow‐up. At 3‐month follow‐up the scores reduced to 14.13 (SD = 8.11, p < .001). Woods and Jose (Citation2011) reported a significant reduction at 1‐year follow‐up for the intervention group, which was significantly different from scores of the control condition (p = .001). The intervention groups reduced CDI scores from 22.9 (SD = 6.6) to 11.9 (SD = 7.0), while no such reduction was seen for the control group, with baseline scores being 26.2 (SD = 4.3) and one‐year follow‐up scores being 25.3 (4.7). Kilonzo et al. (Citation1994) found significant reductions in both the 75-mg and the 125-mg groups. The 75-mg groups had a MES score of 6.13 at end of follow‐up compared to 19.46 at baseline, while the 125-mg group had a final score of 5.87 as compared to a baseline score of 18.13 (p < .01) for both groups (no SD or confidence interval were reported).

Anxiety symptoms

Listug‐Lunde et al. (2013) found no significant reductions in scores on the CDI immediately after the intervention or at 3‐month follow‐up. The baseline mean on the MASC was 51.6 (SD = 14.4), with scores reduced to 43.3 (SD = 23.01) at immediate post‐intervention follow‐up, and 40.1 (SD = 24.1) at 3‐month follow‐up.

Other outcomes

None of the studies tested self‐perceived wellness, suicidal ideation, ability to cope, quality of life, or cost‐effectiveness.

DISCUSSION

This review found a total of four experimental studies evaluating the effect of behavioural and pharmacological interventions for depression in Indigenous people worldwide, three studies assessed behavioural interventions, while one study tested a pharmacological intervention. The three studies assessing behavioural interventions utilised and tested culturally adapted versions of CBT in samples of school‐age children and young adults. The overall findings indicate potential for the use of culturally adapted, CBT‐based treatment for depression, but the provided results are not conclusive due to a low number of studies, heterogeneity between studies, and other methodological limitations. One trial (Ginsburg et al., Citation2012) found that both CBT‐based programs and educational sessions for the prevention of postpartum depression in American Indian adolescents reduced depressive symptoms with no significant difference between the two comparators. A study by Listug‐Lunde et al. (2013), with small group sessions using culturally adapted CBT, showed similar results to a ‘treatment as usual’ group, thereby indicating a potential effectiveness of a less resource‐intensive approach to treating depression in American Indian reservation school participants. Another study (Ginsburg et al., Citation2012) found that a culturally adapted program for small groups, based on cognitive‐behavioural and psycho‐educational techniques, reduced depression symptoms in Maori and Pacific adolescents. The only pharmacological intervention included in this review (Kilonzo et al., Citation1994) compared a lower dosage of a tricyclic antidepressant, clomipramine, to a higher dosage, finding that Indigenous African outpatients responded similarly to 75-mg as to 125-mg. While only tested on a small number of participants, this tentative finding implies that Indigenous African population may respond to treatment regimens at a lower dosage than the standard dose recommended by western guidelines for the general population.

Good evidence exists for the effectiveness of CBT and other psychological therapies for the general population; however, a significant gap remains between evidence and practice for Indigenous people. Culturally tailored use of behavioural therapies in non‐western populations is in line with previous findings which highlight appropriateness of cultural adaptation of CBT‐based therapies (Kalibatseva & Leong, Citation2014), as advocated by Aboriginal Australian clients and counsellors (Bennett‐Levy et al., Citation2014). Results from non‐randomised trials complement our findings. For example, a pre‐post study by Bennett et al. (Citation2014) found that culturally adapted CBT offers promising results as a treatment for clinical depression in adult Maori people. Bennett et al. (Citation2014) found a significant (p < .01) reduction in scores on the BDI‐II from the original 28.7 points (SD = 11.2) to 10.9 points (SD = 14.8) at 6 month follow‐up, and a significant (p < .01) reduction in scores on the Automatic Thought Questionnaire, from 97.5 points (SD = 25.48) to 65.9 points (SD = 28.2) at 6‐month follow‐up.

The improved scores on depressive symptoms and highly rated participant satisfaction with the interventions, suggest that culturally adapted programs may provide mental health services with a potential tool to battle high prevalence rates of depression and suicide in young Indigenous people (Clifford, Doran, & Tsey, Citation2013). Given that holistic approaches to mental wellness are recommended by Indigenous health professionals (Day & Francisco, Citation2013), utilising culturally tailored, CBT‐based techniques as a complement to existing programs may be beneficial (Stewart, Citation2008).

The studies identified in this review provide several insights to using culturally adapted treatments for depression. Firstly, the trials were conducted in various Indigenous groups that is Maori n = 1, American Indians n = 2, African Indigenous n = 1 (Ginsburg et al., Citation2012; Kilonzo et al., Citation1994; Listug‐Lunde et al., Citation2013; Woods & Jose, Citation2011), suggesting that using a culturally adapted CBT‐based intervention to treat depression has the potential to be effective for distinct populations. This is important, considering the substantial differences between Indigenous populations worldwide (Cunningham & Stanley, Citation2003). However, at the same time caution should be taken before generalising the findings to other Indigenous populations for exactly that reason. Secondly, the studies included in the review targeted prevention as well as treatment of depression; this indicates that culturally adapted behavioural intervention can potentially be effective in decreasing the risk of future depressive episodes. Finally, our findings, in conjunction with previous work (Whitfield, Citation2010), demonstrate potential efficacy of culturally adapted CBT in a group scenario rather than on an individual basis, highlighting a potentially more cost‐ and time‐effective way to treat depression. This is particularly important to consider among children and adolescents who attend school. Group‐based CBT has been shown to be useful in the general population for a variety of conditions and can offer a number of advantages including de‐stigmatisation of mental illness and the ability for vicarious learning (Whitfield, Citation2010).

In scientific literature, there is paucity of both experimental and non‐experimental studies on depression in Indigenous people. It is a major concern given the number of Indigenous people admitted to hospitals for depression‐related issues (e.g., self‐harm, suicide, substance misuse) (Vos, Barker, & Begg, Citation2009). Aside from stigma related to mental illness, one reason why insufficient number of studies exists is that Indigenous people are more willing to participate in culturally appropriate studies, designed in partnership with Indigenous communities (Dudgeon et al., Citation2012). Indigenous research reform is not necessarily advocating for the development of specific research designs, but instead for a greater involvement of Indigenous peoples within the construction of research (Henry, Dunbar, Arnott, Scrimgeour, & Murakami‐Gold, Citation2004). Given that the included studies were designed and delivered with the engagement and in consultation with the local Indigenous community members, elders and researchers, the interventions were consistent with the community needs and values (Listug‐Lunde et al., Citation2013; Ginsburg et al., Citation2012; Woods & Jose, Citation2011). Consequently, two of the three studies report a high overall score for participant satisfaction (Listug‐Lunde et al., Citation2013; Woods, 2011) with satisfactory treatment uptake and adherence.

The fact that only one, small study provided data on the effectiveness of pharmacological treatment could be considered surprising in the light of the increasing number of patients who are prescribed antidepressant medication worldwide (McManus et al., Citation2000; Mojtabai & Olfson, Citation2013; Stephenson, Karanges, & McGregor, Citation2013). In the field of Indigenous health research, one of the challenges is to overcome the mistrust among Indigenous communities who have been concerned about past misuse of specimens in genetic studies (Boyer et al., Citation2011). The differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics between Indigenous and non‐Indigenous populations have been noted in the context of various medical conditions and related medications (Grimson et al., Citation2016; Po, Citation2000; Yasuda, Zhang, & Huang, Citation2008). However, due to the methodological limitations of the trial assessing the tricyclic antidepressant treatment, it is not possible to propose conclusive recommendations. The finding that there is paucity of evidence on the effects of antidepressants for Indigenous patients holds important implications for clinical practice. If Indigenous people were to respond to a lower dosage than recommended in treatment manuals, prescribing the standard dosage may lead to increased side‐effects and other adverse events (Bollini, Pampallona, Tibaldi, Kupelnick, & Munizza, Citation1999). This in turn can lead to problems with treatment adherence and a false sense of ineffectiveness of pharmacological treatment, fuelling further hesitance towards the use of Western medical treatments despite their potential effectiveness.

Admittedly, the evidence in this review is insufficient to allow recommendations; nevertheless, we argue that the paucity of evidence base is a valid finding highlighting the necessity for further research. While a systematic review approach by no means revealed all the interventions for treatment of depression that have been trialled in Indigenous communities worldwide, it did include studies that could potentially contribute to the evidence base. Hence, this review may be a useful resource informing governments, policy makers and researchers about the existing paucity and about the need for empirical evidence on this topic.

Limitations

The findings of this review should be considered with caution for a number of reasons. The primary limitation relates to the low number of included studies and related methodological issues, i.e., non‐representative small samples, poorly described study designs and methodology. Limited sample sizes and limited number of adult participants do not allow for generalisability of results and conclusive recommendations regarding the overall effectiveness of behavioural interventions. Similarly, methodological limitations of one study using pharmacological treatment, prevent general conclusions about the findings and effects of antidepressant intervention in Indigenous populations. Meta‐analysis was not possible due to variability in methodology of the included studies, thereby further lowering the power, precision, and generalisability of the treatment effect estimates reported (Akobeng, Citation2005).

Firstly, paucity of methodologically rigorous research trials confirms the notion that most research studies around Indigenous health are descriptive rather than experimental (Sanson‐Fisher, Campbell, Perkins, Blunden, & Davis, Citation2006). Secondly, the trials focusing on behavioural interventions were tested on youth rather than adults. Thirdly, the trial conducted by Woods and Jose (2011) only reported data for those participants who provided data on each assessment point, rather than their full sample; such approach lowers the sample size and its predictive power. Finally, this review aimed to identify available published evidence from experimental trials for effective treatment of depression in Indigenous people. Looking only at diagnosed depression rather than the more holistic account of social and emotional wellbeing narrowed the number of studies included in the systematic search. There is a debate within the literature regarding the relevance of mainstream diagnostic tools across different cultural groups, including Indigenous populations (Durie et al., Citation1995). A key concern about application of standardised measures across various cultural groups is that the assessment of the symptoms may be inaccurate, as Indigenous concepts of depression tend to be broader than psychological and behavioural problems (Westerman, Citation1997).

Future studies and interventions

This review highlights a number of vital points for future research. Significant consequences of untreated depression combined with a low rate of diagnosis among Indigenous communities demand further attention. Future qualitative studies could contribute by providing more insight into understanding Indigenous people and clinicians’ perspectives, fears and beliefs in relation to treatment and diagnosis.

None of the trials in this review compared the culturally adapted CBT intervention to a non‐culturally tailored version; therefore, it is not known if a non‐culturally adapted version would perform similarly. Future studies are needed to provide conclusive recommendations when developing interventions for Indigenous people. Moreover, integration of findings (i.e., translation of evidence) into standard practice comes with its own set of challenges which are not addressed with the evidence from these studies as the trials are all conducted in a research controlled environment with funding and personnel support. To understand the implications for adaptation into the real‐world, future studies need to consider translation within their evaluation model and dissemination strategy.

In terms of effectiveness of pharmacological treatment, more rigorous experimental research with adequate, culturally diverse sample sizes needs to be conducted to determine whether lower doses of antidepressants are effective for Indigenous people, compared to the general population.

Depressive symptoms in Indigenous people are often related to an array of other unresolved issues, including historical trauma (Brave Heart, Chase, Elkins, & Altschul, Citation2011; Brown et al., Citation2012), chronic illness, substance abuse and suicidal ideation (Hunter, Citation2007; Kirmayer, Brass, & Tait, Citation2000). Therefore, a holistic approach may be the most adequate and appropriate approach when designing interventions for Indigenous groups. Furthermore, while some trials used psycho‐educational components, no trials used narrative or interpersonal psychotherapy. The effectiveness of some of these methods for depression is comparable to CBT (Hofmann, Asnaani, Vonk, Sawyer, & Fang, Citation2012) and some of their constructs may be more suitable for the Indigenous population, e.g., narrative therapy. Incorporating validated screening tools, or cultural adaptations of psychometric tools (Brown et al., Citation2013) to determine reductions in depressive symptoms should be a common practice in studies focusing on mental health of Indigenous people, to allow results of trials to be compared to trials focusing on depression in general population. Our systematic search identified a qualitative study (Shepherd et al., Citation2015) looking at the potential of using a computerised gamified depression therapy for Maori adolescents. This innovative study targets depression using CBT and may provide new ways to prevent depression in Indigenous youth.

CONCLUSIONS

Due to limited number of studies and their heterogeneity, the evidence provided in this review is currently not sufficient to conclude that culturally adapted behavioural interventions targeting depression in Indigenous people are effective. However, the findings show some potential in using western treatment models (CBT) combined with Indigenous values and beliefs, especially considering that the interventions included in this review were designed with consultations and the support of Indigenous people; and the overall score for participant satisfaction was rated as high. We argue that paucity of evidence is an important finding encouraging more experimental research to be conducted to trial interventions and to assess optimal evidence translation in order to provide recommendations for current clinical practice and policy. Studies that evaluate the effects of pharmacological treatments and studies that compare the effectiveness of interventions aimed at depression with multi‐component interventions (e.g., trauma or grief and depressive symptoms) are needed. Moreover, future studies should focus on more holistic accounts of mental wellbeing. Only through the development and provision of methodologically rigorous evidence to policy makers and key stakeholders, can we support long‐term positive change for clinical practice.

REFERENCES

- Akobeng, A. K. (2005). Understanding systematic reviews and meta‐analysis. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 90(8), 845–848. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2004.058230

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition (DSM 5). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- Arroll, B., Goodyear‐smith, F., Kerse, N., Hwang, M., Crengle, S., Gunn, J., & Sidhu, K. (2009). Prevalence of depression among Maori patients in Auckland general practice. Journal of Primary Health Care, 1(1), 26–29.

- Balázs, J., Benazzi, F., Rihmer, Z., Rihmer, A., Akiskal, K. K., & Akiskal, H. S. (2006). The close link between suicide attempts and mixed (bipolar) depression: Implications for suicide prevention. Journal of Affective Disorders, 91(2), 133–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2005.12.049

- Bech, P. (2002). The Bech–Rafaelsen melancholia scale (MES) in clinical trials of therapies in depressive disorders: A 20‐year review of its use as outcome measure. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 106(4), 252–264. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.01404

- Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Beck depression inventory‐II. (pp. 78204–72498). San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

- Belmaker, R. H., & Agam, G. (2008). Major depressive disorder. New England Journal of Medicine, 358(1), 55–68. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc080186

- Bennett, S. T., Flett, R. A., & Babbage, D. R. (2014). Culturally adapted cognitive behaviour therapy for Maori with major depression. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, e20(7), 1. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X14000233

- Bennett‐levy, J., Wilson, S., Nelson, J., Stirling, J., Ryan, K., Rotumah, D., & Beale, D. (2014). Can CBT be effective for aboriginal Australians? Perspectives of aboriginal practitioners trained in CBT. Australian Psychologist, 49(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12025

- Bollini, P., Pampallona, S., Tibaldi, G., Kupelnick, B., & Munizza, C. (1999). Effectiveness of antidepressants. Meta‐analysis of dose‐effect relationships in randomised clinical trials. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 174(4), 297–303. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.174.4.297

- Boyer, B. B., Dillard, D., Woodahl, E. L., Whitener, R., Thummel, K. E., & Burke, W. (2011). Ethical issues in developing pharmacogenetic research partnerships with American Indigenous communities. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 89(3), 343–345.

- Brave heart, M. Y. H., Chase, J., Elkins, J., & Altschul, D. B. (2011). Historical trauma among indigenous peoples of the Americas: Concepts, research, and clinical considerations. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 43(4), 282–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2011.628913

- Brown, A., Scales, U., Beever, W., Rickards, B., Rowley, K., & O'dea, K. (2012). Exploring the expression of depression and distress in aboriginal men in Central Australia: A qualitative study. BioMedCentral Psychiatry, 12(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-97

- Brown, A. D. H., Mentha, R., Rowley, K. G., Skinner, T., Davy, C., & O'dea, K. (2013). Depression in aboriginal men in Central Australia: Adaptation of the patient health questionnaire 9. BioMedCentral Psychiatry, 13(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-271

- Brown, C., Abe‐kim, J. S., & Barrio, C. (2003). Depression in ethnically diverse women: Implications for treatment in primary care settings. Professional Psychology, 4, 333–352.

- Chisholm, D., Sweeny, K., Sheehan, P., Rasmussen, B., Smit, F., Cuijpers, P., & Saxena, S. (2016). Scaling‐up treatment of depression and anxiety: A global return on investment analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(5), 415–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30024-4

- Clifford, A. C., Doran, C. M., & Tsey, K. (2013). A systematic review of suicide prevention interventions targeting indigenous peoples in Australia, United States, Canada and New Zealand. BioMedCentral Public Health, 13(1), 463. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-463

- Cox, J. L., Holden, J. M., & Sagovsky, R. (1987). Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10‐item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 150(6), 782–786. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.150.6.782

- Cunningham, C., & Stanley, F. (2003). Indigenous by definition, experience, or world view: Links between people, their land, and culture need to be acknowledged. The British Medical Journal, 327(7412), 403–404. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7412.403

- Day, A., & Francisco, A. (2013). Social and emotional wellbeing in indigenous Australians: Identifying promising interventions. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 37(4), 350–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12083

- Dudgeon, P., Cox, K., D'anna, D., Dunkley, C., Hams, K., Kelly, K., … Walker, R. (2012). Hear our voices: Community consultations for the development of an empowerment, healing and leadership program for aboriginal people living in the Kimberley, Western Australia. Final research report. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Dudgeon, P., Milroy, H., & Walker, R. (2014). Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice. (2nd ed.). Canberra: Kulunga Aboriginal Research Development Unit.

- Durie, M. H., Black, T. H., Christensen, I. S., Durie, A. E., Fitzgerald, E. D., & Taiapa, J. T. (1995). Te hoe Nuku Roa framework: A maori identity measure. Journal of Polynesian Society, 104, 461–470.

- Ferrari, A. J., Charlson, F. J., Norman, R. E., Patten, S. B., Freedman, G., Murray, C. J. L., & Whiteford, H. A. (2013). Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Medicine, 10(11), e1001547. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001547

- Ferrari, A. J., Somerville, A. J., Baxter, A. J., Norman, R., Patten, S. B., Vos, T., & Whiteford, H. A. (2013). Global variation in the prevalence and incidence of major depressive disorder: A systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Psychological Medicine, 43(03), 471–481. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291712001511

- Gadalla, T. M. (2010). Ethnicity and seeking treatment for depression: A Canadian National Study. Canadian Ethnic Studies, 41(3), 233–245. https://doi.org/10.1353/ces.2010.0042

- Ginsburg, G. S., Barlow, A., Goklish, N., Hastings, R., Baker, E. V., Mullany, B., & Walkup, J. (2012). Postpartum depression prevention for reservation‐based American Indians: Results from a pilot randomized controlled trial. Child & Youth Care Forum, 41(3), 229–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-011-9161-7

- Gracey, M., & King, M. (2009). Indigenous health part 1: Determinants and disease patterns. The Lancet, 374(9683), 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60914-4

- Grimson, S., Cox, A. J., Pringle, K. G., Burns, C., Lumbers, E. R., Blackwell, C. C., & Scott, R. J. (2016). The prevalence of unique SNPs in the renin‐angiotensin system highlights the need for pharmacogenetics in indigenous Australians. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology, 43(2), 157–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1681/12525

- Hall, G. H., & Patrinos, H. A. (2012). Indigenous peoples, poverty, and development. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Henry, J., Dunbar, T., Arnott, A., Scrimgeour, M., & Murakami‐gold, L. (2004). Indigenous research reform agenda: A review of literature. Casuarina, NT: Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal & Tropical health (CRCATH).

- Higgins, J. P. T., Altman, D. G., Gøtzsche, P. C., Jüni, P., Moher, D., Oxman, A. D., & Sterne, J. A. C. (2011). The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. British Medical Journal, 343, d5928. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5928

- Hofmann, S. G., Asnaani, A., Vonk, I. J. J., Sawyer, A. T., & Fang, A. (2012). The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta‐analyses. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 36(5), 427–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-012-9476-1

- Huhn, M., Tardy, M., Spineli, L. M., Kissling, W., Förstl, H., Pitschel‐walz, G., & Davis, J. M. (2014). Efficacy of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy for adult psychiatric disorders: A systematic overview of meta‐analyses. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(6), 706–715. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.112

- Hunter, E. (2007). Disadvantage and discontent: A review of issues relevant to the mental health of rural and remote indigenous Australians. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 15(2), 88–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1584.2007.00869.x

- Isaacs, A. N., Pyett, P., Oakley‐browne, M. A., Gruis, H., & Waples‐crowe, P. (2010). Barriers and facilitators to the utilization of adult mental health services by Australia's indigenous people: Seeking a way forward. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 19(2), 75–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2009.00647.x

- Jorm, A. F., Bourchier, S. J., Cvetkovski, S., & Stewart, G. (2012). Mental health of indigenous Australians: A review of findings from community surveys. Medical Journal of Australia, 196(2), 118–121. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja11.10041

- Kalibatseva, Z., & Leong, F. T. L. (2014). A critical review of culturally sensitive treatments for depression: Recommendations for intervention and research. Psychological Services, 11(4), 433–450. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036047

- Kessler, R. C., & Bromet, E. J. (2013). The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Annual Review of Public Health, 34, 119–138. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114409

- Kilonzo, G. P., Kaaya, S. F., Rweikiza, J. K., Kassam, M., & Moshi, G. (1994). Determination of appropriate clomipramine dosage among depressed African outpatients in Dar es salaam, Tanzania. The Central African Journal of Medicine, 40(7), 178–182.

- Kirmayer, L. J., Brass, G. M., & Tait, C. L. (2000). The mental health of aboriginal peoples: Transformations of identity and community. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 45(7), 607–616. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370004500702

- Kisely, S., Alichniewicz, K. K., Black, E. B., Siskind, D., Spurling, G., & Toombs, M. (2017). The prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders in indigenous people of the Americas: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 84, 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychires.2016.09.032

- Kovacs, M. (1992). Children's depression inventory: Manual. Tonawanda, NY: Multi‐Health Systems.

- Listug‐lunde, L., Vogeltanz‐holm, N., & Collins, J. (2013). A cognitive‐behavioral treatment for depression in rural american indian middle school students. American Indian & Alaska Native Mental Health Research: The Journal of the National Center, 20(1), 16–34. https://doi.org/10.5820/aian.2001.2013.16

- Maclean, S., Ritte, R., Thorpe, A., Ewen, S., & Araben, K. (2015). Assessing compliance with aboriginal and Torres Strait islander health research guidelines within systematic reviews. Australian Indigenous Health Bulletin, 15(4), 1–5.

- March, J. S., Parker, J. D. A., Sullivan, K., Stallings, P., & Conners, C. K. (1997). The multidimensional anxiety scale for children (MASC): Factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(4), 554–565. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199704000-00019

- Mathers, C. D., & Loncar, D. (2006). Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Medicine, 3(11), e442. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442

- Mayou, R., Hawton, K., Feldman, E., & Ardern, M. (1991). Psychiatric problems among medical admissions. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 21(1), 71–84.

- Mchugh, R. K., Whitton, S. W., Peckham, A. D., Welge, J. A., & Otto, M. W. (2013). Patient preference for psychological vs pharmacologic treatment of psychiatric disorders: A meta‐analytic review. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74(6), 595–602. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.12r07757

- Mcmanus, P., Mant, A., Mitchell, P. B., Montgomery, W. S., Marley, J., & Auland, M. E. (2000). Recent trends in the use of antidepressant drugs in Australia, 1990‐1998. Medical Journal of Australia, 173(9), 458–462.

- Mojtabai, R., & Olfson, M. (2013). National trends in long‐term use of antidepressant medications: Results from the US National Health and nutrition examination survey. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 75(2), 169–177. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.13m08443

- Po, L. W. (2000). Pharmacogenetics and psychopharmacotherapy. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 25(3), 197–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coph.2003.09.007

- Sanson‐fisher, R. W., Campbell, E. M., Perkins, J. J., Blunden, S. V., & Davis, B. B. (2006). Indigenous health research: A critical review of outputs over time. Medical Journal of Australia, 184(10), 502–505.

- Schraufnagel, T. J., Wagner, A. W., Miranda, J., & Roy‐byrne, P. P. (2006). Treating minority patients with depression and anxiety: What does the evidence tell us? General Hospital Psychiatry, 28(1), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.07.002

- Shepherd, M., Fleming, T., Lucassen, M., Stasiak, K., Lambie, I., & Merry, S. N. (2015). The design and relevance of a computerized gamified depression therapy program for indigenous maori adolescents. JMIR Serious Games, 3(1), e1. https://doi.org/10.2196/games.3804

- Stephenson, C. P., Karanges, E., & Mcgregor, I. S. (2013). Trends in the utilisation of psychotropic medications in Australia from 2000 to 2011. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 47(1), 74–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867412466595

- Stewart, S. L. (2008). Promoting indigenous mental health: Cultural perspectives on healing from native counsellors in Canada. International Journal of Health Promotion and Education, 46(2), 49–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/14635240.2008.10708129

- Turner, J., & Kelly, B. (2000). Emotional dimensions of chronic disease. Western Journal of Medicine, 172(2), 124–128. https://doi.org/10.1136/ewjm.172.2.124

- Vicary, D., & Westerman, T. (2004). 'That's just the way he is': Some implications of aboriginal mental health beliefs. Australian e‐Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health, 3(3), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.5172/jamh.3.3.103

- Vos, T., Barker, B., & Begg, S. (2009). Burden of disease and injury in aboriginal and Torres Strait islander peoples: The Indigneous health gap. International Journal of Epidemiology, 38, 470–477.

- Waraich, P., Goldner, E. M., Somers, J. M., & Hsu, L. (2004). Prevalence and incidence studies of mood disorders: A systematic review of the literature. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 49(2), 124–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370404900208

- Weissman, M. M., Sholomskas, D., Pottenger, M., Prusoff, B. A., & Locke, B. Z. (1977). Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: A validation study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 106(3), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112455

- Westerman, T. G. (1997). Working with aboriginal people. Psychologically Speaking, 2(35), 5–12.

- Whitfield, G. (2010). Group cognitive–behavioural therapy for anxiety and depression. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 16(3), 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.bp.108.005744

- WHO (2015). Mental health ATLAS 2014. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Woods, B., & Jose, P. E. (2011). Effectiveness of a school‐based indicated early intervention program for Maori and Pacific adolescents. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology, 5(1), 40–50. https://doi.org/10.1375/prp.5.1.40

- Wulsin, L. R., Vaillant, G. E., & Wells, V. E. (1999). A systematic review of the mortality of depression. Psychosomatic Medicine, 61(1), 6–17. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-199901000-00003

- Yasuda, S. U., Zhang, L., & Huang, S. M. (2008). The role of ethnicity in variability in response to drugs: Focus on clinical pharmacology studies. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 84(3), 417–423. https://doi.org/10.1038/clpt.2008.141

- Zubrick, S. R., Dudgeon, P., Gee, G., Glaskin, B., Kelly, K., Paradies, Y., & Walker, R. (2010). Social determinants of aboriginal and Torres Strait islander social and emotional wellbeing. In Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice (pp. 75–90). Canberra, Australia: Department of Health and Ageing.