Abstract

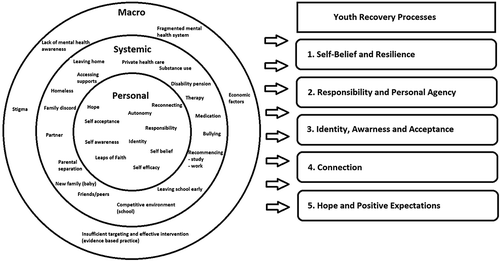

The recovery model and practice orientation is promoted as a central feature of mental health service provision across the English speaking world. Yet the model relies on adult frameworks and its applicability to the youth recovery experience has not been established. The current qualitative study explored the common themes in the recovery experiences of 15 young people aged 18–23-years with severe mental health conditions from the Eastern Metropolitan Region of Melbourne, Australia. The aim of the study was to develop a thematic model of youth recovery utilising the experiences of young people with severe mental illness. These findings are then discussed in relation to common themes found in adult recovery research and in regard to the current understanding of young people and recovery. Qualitative data was inductively coded into a thematic model of youth recovery forming two overarching themes. The first was defined as ecological systems (ES) including three subthemes (personal, systemic, and macro). The second was defined as youth recovery processes drawing narratives from across the ES to form five subthemes (self‐belief and resilience; responsibility and personal agency; identity, awareness and acceptance; connection; and hope and positive expectations). The resulting themes revealed the critical importance of the ecological context in the personal recovery experiences of young people. It is contended that recovery in this stage of the lifespan is best conceptualised within this ecological framework. Implications for youth recovery conceptualisation and mental health service delivery are discussed.

What is already known about the topic?

Recovery is a core part of service delivery for all government funded specialist mental health services within Australia, including those working with youth.

The vast evidence base of recovery research is derived primarily from qualitative studies that analyse the narratives of adults with a lived experience of mental illness. Research that focuses on the recovery experiences of children, young people and older adults is scarce. This is particularly the case for research on young people with severe mental health conditions.

Recovery by its very nature focuses on individual personal perspectives of recovery. While idiosyncratic to the individual, a number of common themes in the recovery process can be established through a qualitative thematic analysis and narrative synthesis.

What this topic adds?

Being the only recovery research that exclusively utilises the narratives of young people aged 18–23-years of age (mean age 20), the study provides evidence of commonalities and differences between themes found in existing adult research on this topic, where the mean age commonly ranges from 30 to 50-years. This has important implications for the manner in which recovery‐oriented practice is carried out with young people.

The study discovered two overarching themes: (1) ecological systems (ES) placing narratives within personal, systemic, and macro systems; and (2) youth recovery processes that involved narratives across the ES. The findings reinforce the need to develop and refine ecological models for working with young people experiencing severe mental illness.

The study developed the first thematic model of youth recovery displaying youth recovery processes within an ecological context. The findings provide insight into recovery and youth, filling a gap that supports application of recovery and integration with existing paradigms in the context of youth mental health service provision.

Mental illness commonly emerges and is at its highest prevalence from late adolescence through to young adulthood (Alegria, Jackson, Kessler, & Takeuchi, Citation2001–2003; Arnett, Citation2000; Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], Citation2007). It has been noted that at this critical juncture in human development, access to targeted mental health services is crucial in addressing such issues (Davis, Koroloff, & Ellison, Citation2012; Eccles, Barber, Stone, & Templeton, Citation2001; Wickrama, Conger, Lorenz, & Jung, Citation2008). The recovery model (Anthony, Citation1991), including recovery oriented practice models (Oades, Deane, Crowe, Lambert, & Kavanagh, Citation2005) have been described as a practice ‘movement’ (Davidson, Citation2016), in that it has been incorporated into most state‐funded mental health systems throughout the English speaking world and for all people across the lifespan who access these services. This includes the United States (Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Citation2010), England (National Institute for Mental Health in England (NIMHE), Citation2005), and Australia (Department of Health, Citation2009). However, the vast majority of recovery research that informs this model is concerned with adult populations.

This broad‐stroke approach to research and service delivery promotes a single and homogenous model of recovery, which may ignore the idiosyncratic needs and narratives of subgroups such as children, young people and older adult populations (Barnett & Lapsley, Citation2006; Lal, Citation2010; Rankin & Petty, Citation2016). In relation to young people, the use of adult driven recovery models may be ignoring the typical cognitive, behavioural, environmental and social developmental factors that are unique to this stage of development (Simonds, Pons, Stone, Warren, & John, Citation2014). Drawing from the experiences of young people with severe mental health conditions, the current study's aim is to address an important gap in recovery research by developing a thematic model of youth recovery for young people with severe mental illness. These results are further discussed in relation to recovery themes previously uncovered in research with adults and the limited research available exploring recovery and young people.

The recovery movement: Clinical and personal

Current literature often differentiates between two discrete but interconnected conceptualisations of recovery (Davidson, Lawless, & Leary, Citation2005; Glover, Citation2012). The first is commonly referred to as ‘clinical recovery’, and is focused on the reduction of symptoms, impairment and a return to a level of functioning prior to the development of an illness. The second approach, commonly referred to as personal recovery, is focused on an individual's journey of growth and development, typically defined through social success and personally defined goals (Macpherson et al., Citation2016). Personal recovery is thereby challenging to define due to its individualised nature (Gilburt, Slade, Bird, Oduola, & Craig, Citation2013). However, a commonly cited definition by Anthony (Citation1993) describes personal recovery as:

a deeply personal, unique process of changing one's attitudes, values, feelings, goals, skills and/or roles. It is a way of living a satisfying, hopeful and contributing life even with the limitations caused by an illness. Recovery involves the development of new meaning and purpose in one's life as one grows beyond the catastrophic effects of mental illness (p. 15).

The importance of personal narratives, as identified within the personal recovery movement, only gained prominence in the 1980s when people with a mental illness, and a minority of professionals, responded against the dominance of profession‐based power and its association with clinical recovery. Clinical recovery was viewed as disempowering as it emphasised the pre‐eminence of professional intervention and alluded to the permanency of severe mental illness (Corrigan, Citation2002; Ralph & Corrigan, Citation2005). However, the two terms are arguably useful for different purposes and populations (Davidson et al., Citation2005). A difference is displayed in divergence in participant ratings on clinical and personal recovery outcome measures (Macpherson et al., Citation2016). The current study utilises a narrative approach to understanding recovery and is thereby more aligned with personal recovery. We will utilise the term ‘recovery’ for simplicity, referring to definitions of recovery originating from personal recovery research.

Recovery characteristics, processes, and stages

The evidence base of recovery originates from the personal experiences of adults living with severe mental illness (Barnett & Lapsley, Citation2006; Slade et al., Citation2012). Despite the highly individual nature of recovery, established narratives appear to centre on a limited combination of personal characteristics, processes, and stages of recovery (Leamy, Bird, Boutillier, Williams, & Slade, Citation2011; Tew et al., Citation2012). Characteristics include personal descriptions of the recovery journey (i.e., ‘non‐linear’ or ‘a struggle’). Processes are discrete areas of change involving intrapersonal and interpersonal responses to the presence of an illness and changed life circumstance. For example, a theme may be broad, such as ‘rediscovring life’, and that theme may possess subthemes, like ‘role transformation’ and ‘reconnecting with day‐to‐day activities’. Glover's (Citation2012) model outlined five processes: (1) a passive to active sense of self; (2) hopelessness and despair to hope; (3) moving from others in control to having personal control and responsibility; (4) alienation to discovery; and (5) disconnectedness to connectedness. Further more, models of recovery that are based on thematic analysis often include a progression through a series of stages that represent movement along a continuum from less to more recovery. Andresen, Oades, and Caputi (Citation2003) studied personal recovery accounts to identify additional processes such as ‘finding and maintaining hope’ and produced a validated stage model where individuals moved along stages of a given trajectory. This research informed a widely utilised psychiatric rehabilitation model called the Collaborative Recovery Model (Oades et al., Citation2005).

The commonality between themes arising from separate studies on recovery has given way to research focusing on synthesising findings from multiple studies. Schrank and Slade (Citation2007) synthesised several studies that identified common components involved in the recovery process including: hope, spirituality, responsibility, control, empowerment, connection, purpose, self‐identity, and stigma. Another comprehensive synthesis was carried out by Leamy et al. (Citation2011) utilising 87 studies of personal accounts of recovery in which they identified five categories of individual recovery processes outlined as the CHIME model of processes including: connectedness; hope and optimism for the future; identity; meaning and purpose; and empowerment.

Beyond a person centred process

While most studies exploring recovery are concerned with personal themes and processes on a continuum from less recovered to more recovered, others have adopted alternative ways of conceptualising recovery. Jacobson and Greenley (Citation2001) described a model of recovery that included both personal and external recovery conditions. Personal conditions included recovery processes commonly outlined, such as an individual journey of hope, healing, empowerment and connection. Whereas, external conditions included broader societal factors that influenced recovery, such as human rights, a positive culture of healing and recovery‐oriented services. Alternatively, Onken, Craig, Ridgway, Ralph, and Cook (Citation2007) mapped out recovery concepts within an ecological framework using a dimensional analysis of existing recovery literature. The researchers conceptualised recovery as an interactive process within an environmental system that included internal and external resources and challenges. Kaewprom, Curtis, and Deane (Citation2011) constructed a broadened understanding of recovery, arising from the opinions of Thai mental health nurses supporting patients with schizophrenia. They identified both personal and environmental facilitators and barriers to recovery. Tew et al. (Citation2012) explored the external influence of social factors on recovery and concluded that existing models of recovery are limited by not adequately taking into account the dynamic relationship between social systems and recovery.

Recovery and young people

The terms ‘youth’ and ‘young people’ are often used interchangeably to define those who are in the pivotal period of the lifespan between childhood and adulthood, which, from a developmental perspective is known as ‘adolescence’. A key feature of this period of development is biological, neurological and psychosocial transition, including the expectation that the end of this period is marked by the successful attainment of independence and adult roles (Arnett, Citation2000; Eccles et al., Citation2001). There is, however, disparity both within the literature and in global adolescent population research designs of what age constitutes the start and beginning of the adolescent period, which in turn impacts on the age of participants that are included in adolescent studies, and then on laws, policies, and programs designed to support those who are in this period of the lifespan (Sawyer, Azzopardi, Wickremarathne, & Patton, Citation2018). The World Health Organisation defines adolescence as spanning between the ages of 10 and 19-years of age (World Health Organisation, Unesco, & Mathers, Citation2017). In contrast, some scholars argue that adolescence should span from 10 to 24-years (i.e., Sawyer et al., Citation2018), which would be more in line with the host of brain imaging studies which show the extended period of time that neurological changes are taking place (i.e., Paus, Keshavan, Giedd, & Paus, Citation2008). In regards to studies of later adolescence, researchers have regularly treated individuals over 18 or 21-years of age in line with their legal status as adults and have therefore labelled participants as such (Davis et al., Citation2012; Wickrama et al., Citation2008). From a service delivery and study‐context perspective, the national youth mental health service in Australia, headspace, determines young people to be those who are aged between 12 and 25 (Bassilios, Telford, Rickwood, Spittal, & Pirkis, Citation2017), and as this study is concerned with interviewing young people aged 18–23, the term ‘youth’ will be utilised.

Research on the recovery experiences of young people is scarce. From those that are available, there are two types of methodologies: top‐down or deductive research and bottom‐up or inductive research. Top‐down studies ask young people, professionals, and family members whether existing models of recovery are relevant to their experience (Friesen, Citation2007; Mental Health Coordinating Council, Citation2014). These studies impose an existing framework of recovery on study participants. Bottom‐up studies interview young people directly about their recovery experiences without limiting responses to agreement or non‐agreement to a prescribed model (Barnett & Lapsley, Citation2006; Simonds et al., Citation2014). These studies seek to add to the existing body of work in this area, in order to inform a better understanding of this phenomenon.

Top‐down approaches to recovery for young people

Top‐down research has raised some important issues around the applicability of the recovery paradigm to young people (Friesen, Citation2007; Mental Health Coordinating Council (MHCC), Citation2014). Using feedback from five young people, family, and professionals, ‘The Recovery Paper for Young People’ (MHCC, Citation2014) includes a review of the CHIME model, concluding that this may need to be slightly adjusted for young people as it was said to be incongruent with young people still progressing through a key developmental stage. The authors outlined the notion of responsibility as an area of conjecture as young people may still be inherently reliant on parents or caregivers as they are only beginning a process of independence and acquiring more responsibility in their lives.

Friesen (Citation2007) completed a phased review of children and youth recovery, resilience, and mental health that included a literature review, a structured discussion process with individuals and groups and a cross tabulation of different and shared experiences of recovery, resilience and systems of care principles. Friesen found that some professionals were advocates of the explicit application of a recovery model to children and youth in services, while others had significant misgivings. Some of the issues raised included questions around what recovery might add beyond existing systems of care, and how recovery related to existing early intervention and resilience models. The term recovery itself was not consistently seen by participants as desirable due to its literal focus on returning to a previous state of functioning or wellbeing. Participants preferred a developmental perspective of recovery, which, in contrast requires a young person to advance beyond previous states of functioning. Friesen (Citation2007) argued that young people are often without reference to former states of improved functioning, leading participants to ask the question ‘recovery from what?’. Common conceptions of recovery as a process of returning to a previous state is somewhat of a juxtaposition for young people aged 12–25 who should be continuing to develop forward rather than backwards to previous developmental stages (Robinson, Citation2006). Other points included the notion that the term recovery is easily confused with the common phraseology around ‘clinical’ recovery from illness. This may lead people to misinterpret recovery within youth mental health settings, by conceptualising recovery as having undergone a ‘cure’ (Friesen, Citation2007).

Bottom‐up exploration of young people's recovery experiences

One study conducted by Simonds et al. (Citation2014) directly explored the recovery narratives of young people, using a sample of early adolescents (aged 12–16). Another study, conducted by Barnett and Lapsley (Citation2006) used a combination of older adolescents and adults (aged 18–29-years), which they termed young adults.

The first study by Simonds et al. (Citation2014) explored the personal narratives of 12 young participants who had been diagnosed with depression and anxiety along with their maternal parent. Simonds et al. adopted a bottom‐up approach by not referring to existing themes identified in adult recovery literature. They discovered the following themes: loss of self, renegotiating the self, and (limited) anticipation of future self. The first two themes were consistent with adult experiences of recovery and encapsulated the notion of loss and rediscovery, such as and in relation to loss of identity (i.e., Glover, Citation2012). Furthermore, the identified period of adjustment to living with mental illness, that young people experienced, was characterised as contributing to disruption of self‐identity and to a heightened sense of self‐other difference. The second theme represented a period where young people reported increased self‐awareness and engagement in services. Simonds et al. indicated that this phase included increased awareness of personal strengths, resilience and a reduction in self‐other difference, which resulted in social re‐engagement. However, the last theme, ‘anticipation of future self’, was argued to depart from existing recovery research paradigms, with young people focusing mainly on symptom eradication, and displaying limited ability or inclination to look forward into the future. Acknowledging the potential for sampling bias, Simonds et al. proposed that, amongst other things, younger adolescents may not yet have reached the ability to reflect on and imagine possible future selves.

The second study by Barnett and Lapsley (Citation2006) documented the experiences of 40 adolescents and young adults aged 18–29-years with severe mental health problems (i.e., two‐thirds had been diagnosed with a psychosis spectrum disorder including schizophrenia and bipolar illnesses and others were given diagnoses that included one or more of the affective, anxiety, personality, eating or posttraumatic stress disorders). While comparable to other studies of adult recovery experiences, the existence of 18–25‐year‐old participants in the sample is of interest to the authors considering the dearth of recovery research on youth samples. With this in mind, Barnett and Lapsley explored the nature of early use of publicly funded mental health services and gathered information on the factors that helped or hindered recovery in the sample. They identified three overarching themes related to recovery: (1) surviving day to day; (2) moving forward; and (3) living well. While their themes were not contrasted against processes or themes identified in adult recovery models, they are akin to documented adult stages of recovery, whereby individuals move from an initial point of distress, detachment and confusion to one of greater wellbeing, awareness and autonomy (i.e., Leamy et al., Citation2011).

In summary, despite the recovery‐oriented practice model being a central component of mental health service provision in Australia and globally, the scarcity of research on youth populations has arguably resulted in a questionable ‘one size fits all’ application of existing adult recovery models to services for young people (Simonds et al., Citation2014). While they may well be applicable (i.e., Leamy et al., Citation2011), there may also be some nuanced differences in young people's recovery experiences, which are associated with the specific developmental needs of this stage of the lifespan. The lack of youth‐specificity to recovery research is even further diluted when one considers the differential developmental needs of children, early adolescence, adolescence, and emerging or young adulthood. Youth mental health service providers who must rely on existing research to inform their evidence‐informed recovery practices need to be provided with a greater array of evidence, which focuses specifically on the recovery of young people with mental illness.

METHOD

Recruitment and sample

Research ethics approval was granted by Swinburne University's Human Research Ethics Committee, project number 2015/268 that permitted data collection with young service‐recipients of a number of mental health services operated by EACH social and community health a non‐government organisation operating a range of social and community health services in the Eastern Metropolitan Region of Melbourne, Australia. Participation in the research interviews was offered to all young service users of a youth mental health community support service, whereby eligibility for the service included being 16–25-years old and having a disability likely to be lifelong that is attributable to a psychiatric condition with impairments resulting in substantial disruption to areas of day‐to‐day functioning (i.e., severe mental illness). Participation was on a voluntary basis, with participants compensated for their time and contribution by way of a voucher. Interested participants were provided with a plain language research information statement and consent form that was completed and returned to researchers. The final sample included 15 young people, 10 females and 5 males, aged between 18 and 23-years old with a mean age of 20-years old. Participant diagnoses were not limited to any one disorder and all reported one or more co‐occurring disorders made up of both high prevalence mental health conditions, such as anxiety and depression, and low prevalence mental health conditions, such as schizophrenia, bipolar, and borderline personality disorder.

Procedure and instruments

Individual face‐to‐face audio‐recorded interviews were conducted by one researcher using a semi‐structured interview schedule derived from previous research by Simonds et al. (Citation2014). The structured questions included:

Can you tell me about the period when you first started to experience problems with your mental health?

Can you tell me about the time you first began receiving mental health services?

Can you tell me about your current situation?

What do you think has changed over these points in time?

How do you think these changes came about?

How do you see yourself in the future in relation to the issues you have experienced with mental health?

The interview process was influenced by recommendations around qualitative research by Davidson (Citation2003) including emphasising the participant as expert in their own experience, collecting narratives of raw experience and following the participants lead. Data was collected for each question until saturation was achieved. Recordings totalled 690-min with an average length of 46-min per interview. Recovery as construct was never mentioned in the interview to ensure experiences of young people where not influenced by existing conceptualisations of recovery.

Data analysis

Audio‐recorded interviews were transcribed into written format in preparation for thematic analysis. Transcriptions were anonymised by replacing participant names and other identifiers with codes or pseudonyms. The primary researcher, a youth mental health professional with 10 years’ experience carried out the thematic analysis process using an inductive approach. Nvivo 11 software was used as a platform to carry out steps of coding and thematic analysis (Nvivo qualitative data analysis Software, Version 11. 2015; QSR International Pty Ltd., Melbourne, Australia). For reliability purposes, codes were also cross‐checked with the second researcher. Throughout the analysis process, it was acknowledged that the process of coding and thematic analysis is a co‐construction of the narratives of young people and the researchers’ interpretation of meaning. Braun and Clark's (Citation2006) exploratory method was followed, where all themes that emerged from interviews were reported and none were excluded from the results. The steps included: (1) researcher familiarisation with the data within each interview; (2) generating initial codes by listing and naming all components of a young person's interview and only excluding immaterial dialogue; (3) searching for emerging themes and patterns within and between individually coded interviews; (4) cross‐checking of themes with the second researcher; (5) reviewing and compiling themes; (5) defining and naming themes; and (6) producing a report.

RESULTS

The thematic analysis revealed two overarching themes: (1) ecological systems (ES); and (2) youth recovery processes (YRP) that were formed exclusively from the narratives of young people. The first of these overarching themes, ES, included three subtheme levels (personal, systemic, and macro) and the second overarching theme, YRP, included five subthemes (self‐belief and resilience; responsibility and personal agency; identity awareness and acceptance; connection; and hope and positive expectations, see Fig. 1).

Ecological systems

This overarching theme included three subthemes related to the context of where recovery narratives were occurring. The personal level included intrapersonal change, including modified individual attitudes, awareness and perspectives. For example, Young Person 10, a 22 year old female, spoke about her own personal struggles with trusting other people enough to talk to about her schizophrenia, anxiety and depression, and her own personal narrative about how she manages her diagnoses:

‘No. I don't talk to anyone about what's going on in my head, because they could use that against me and, I've just learnt to shut‐out from people and just be artificial.’ and ‘I'm still disciplined with my mind, and the motions and that. I guess I've accepted anxiety and depression because that wasn't my fault, it was genetic, so I try and manage it. I really try and manage it. The schizophrenia I've accepted in a way, and because I have to learn to just manage it without medication I use the term I have two brains, the logical side, and then the illogical side…’.

The systemic level included social and geographic factors within the individual's immediate sphere such as family, friends, school, and accessing professional supports. For example, Young Person 6, a 19 year old female spoke about the impact of finding school friends that she connected with (after a period of being bullied at school) on her wellbeing:

‘In Year 8, I found a new bunch of friends… but I got really lucky with that, we became quite close, and I still see them now. And so I think that helped quite a bit, finding a new bunch of people to hang out with’.

Similarly Young Person 5, 23 year old female, spoke about the negative impact of being admitted to a hospital to receive support for her anorexia:

‘At the Hospital (name removed) for about three, four days, basically restore the body. And yep, my hospital admission, I found the first one, it made me so much worse, because I mean you had rules there, for example you only have half an hour to eat dinner, you'd have to eat it all, portion sizes, that kind of thing, and snacks’.

At the macro level, young people spoke about broader social, political and technological forces that impacted on the Personal and Systemic level factors. For example, Young Person 7, 19-year old female, spoke about the impact of the ‘Better Access’ initiative on her ability to receive support:

‘Yeah, so I used to have counselling with her. It was usually once, well, it sort of varied, because through Medicare I get 10 sessions free. So last year I did that.’

Youth recovery processes

The second overarching them included five subthemes, each defining a separate recovery process, which resided within and interacted with each level of the Ecological subthemes. For example, connection is a process that might involve a personal change in attitude or desire, the capacity to re‐engage friends, the presence of friends and their friends’ openness to engage an individual with a mental illness, where the macro factors include awareness of mental health and stigma. Each individual recovery process is outlined further below with example quotes derived from the interviews.

Youth recovery process 1: Self‐belief and resilience

This recovery process outlines the reported development of confidence, self‐efficacy and self‐belief and an accompanying resilience that enabled young people to take on the various challenges in life despite systemic (i.e., lack of employment opportunities or social exclusion) and mental health adversity. Young Person 4, 20 year old female:

‘It's so much harder than I thought but I can so do it. It makes you feel really proud of yourself when you can do all this stuff and actually survive on your own’.

‘Yeah. Well now I'm like, you know what, this isn't going to let me down, I'm going to try and beat this, or not have it consume my life’.

Youth recovery process 2: Responsibility and personal agency

This recovery process involved the development of a sense of personal agency and control within young people's lives. Young people going through this process appeared to move away from others who are in control of them and towards self‐control and autonomous direction. Young person 4, 20 year old female stated:

‘I just really started I suppose breaking things down in terms of the goals and like working towards planning my life out, the start of my life out.’ ‘It feels good to be able to have some control over the way I am feeling. The harder I work the better I feel.’

‘I've actually been able to help around the house, and that, because I haven't done anything to help the family and they've done so much…. So, I'll cook dinner, do housework, I look after everyone,’

Youth recovery process 3: Identity, awareness and acceptance

This recovery process involved the young person developing a greater sense of themselves, their personal context and a growing sense of acknowledgement and acceptance of their mental health diagnosis, the challenges they face and their unique strengths. Young Person 5, 23 year old female stated:

‘Last year was when I developed acceptance of my mental health, and that it's okay. This is me. Labelled with diagnoses. They are part of me but they don't define me as a person.’ ‘I think the first step…was the acceptance part. That was a really big part of yeah, planning around the future and how I'm going to manage and keep going.’

‘I have changed my hair so many times in the past twelve months, two years whatever and that is kind of me trying to figure out what I want, what I want to be and sort of taking back control over my physical appearance’.

Youth recovery process 4: Connection

Young people spoke about moving from disconnection to connection, especially in relation to their peers. At times, this process involved actively disengaging from others. Many had experiences of rejection and bullying by peers throughout their school years. This often occurred years in advance of and subsequent to the development of mental health issues. Young Person 6, female 19-years old stated:

‘I think that's probably been one of the biggest things that's impacted on my mental health is the lack of connection.’

‘I am trying to reach out more to a lot of my friends and say hey let's do something. I try to get to my sister's house one night a week and stay over.’

Youth recovery process 5: Hope and positive expectations

This recovery process involved a shift in thinking, from one of despair and hopelessness to the that of hope and positive expectations for the future, including a belief that life would improve despite current challenges. Young Person 9, 18 year old male stated:

‘I've slept in car washes, I've done that, been that. All right, and when you're scraping the… bottom of the barrel you have nowhere else to look but….up. As soon as you look up everything changed for me.’

‘Long term I actually want to go back and study. I really want to start getting linked in with workers to help me find a house…..I want to get my licence…. I am learning more and more….about independent living like cooking for myself, meal planning, actually how to run a household…. like adapting and still being able to be ok with that. It's so much harder than I thought, but I can so do it.’

DISCUSSION

The current study's aim was to develop a thematic model of youth recovery based around the personal recovery narratives of young people ‘with severe mental illness’. The results formed a thematic model of youth recovery including two overarching themes, ES and YRP. The ES subthemes form an ecological context for narratives, emerging within personal, systemic, and macro levels. The second theme outlined five YRPs formed from narratives including factors from each of the ES subthemes. These results are important to discuss in relation to the main body of recovery research derived from the experiences of adults. The vast majority of adult based recovery research outlines themes as personal processes and stages that occur on a continuum from less to further recovered (Glover, Citation2012; Leamy et al., Citation2011; Oades et al., Citation2005; Schrank & Slade, Citation2007; Simonds et al., Citation2014). This research supports the conceptualisation of recovery as a personal process, which is evident in one of the most cited definitions of recovery (i.e., Anthony, Citation1993). It is however, arguable and indicated by the current findings that a dynamic interplay between person‐environmental processes are an integral part of young people's experience of recovery processes. The current research emphasises the interactive nature of recovery for young people, sharing components with the original ecological systems theory and risk‐resilience models that outline interactive personal and environmental factors, cumulative protective and promoting factors, adversity and trauma factors that contribute to an individual's well‐being and developmental trajectories (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979; Gorter et al., Citation2014; Schilling, Aseltine, & Gore, Citation2008).

Withstanding the ecological conceptual differentiation, the YRPs share many similarities with the diverse number of processes found in adult populations (Glover, Citation2012; Oades et al., Citation2005; Schrank & Slade, Citation2007). In contrasting the current study's findings with the CHIME model, arguably the most comprehensive research synthesising adult recovery processes, the current findings are highly consistent in underlying meaning and terminology utilised to describe specific themes of ‘connection’, ‘Hope and positive expectations’ and ‘identity, awareness and acceptance’. The two CHIME processes of ‘meaning and purpose’ and ‘empowerment’ were identified as subcomponents of the themes of ‘self‐esteem and resilience’ and ‘personal agency and autonomy’ respectively.

A significant point of difference between this study's thematic model of youth recovery and themes found in adult literature was the clear importance of narratives occurring across an ecological context, where factors fell into personal, systemic, and macro environmental subthemes. The emphasis on environmental factors as an integrative part of (rather than impacting on) recovery have been explored in a small number of previous studies (i.e., Jacobson & Greenley, Citation2001; Kaewprom, Curtis, & Deane, Citation2011; Onken et al., Citation2007). There is also limited research exploring the mechanisms or external factors involved in recovery (Silverstein & Bellack, Citation2008). However, there are examples of studies exploring systemic factors such as social contact as important to recovery and emphasise the need for professionals to facilitate interaction with communities, rather than only focusing singularly on the personal process (Davidson, 2003; Tew et al., Citation2012). External factors have been highlighted as crucial to recovery, contributing to personal changes such as self‐esteem and sense of self (Roe, Citation2001). It is therefore arguable that external factors are vital and inseparable from the broader construct of recovery. The current findings reinforce recovery as a process involving interaction between the individual and their environment. Recovery may include a combination of discrete processes such as continuation of the psycho‐social development, a process heavily intertwined with the external environment and more personal or internal changes that include adaptation and accommodation. These discrete processes are likely to occur concurrently with progress in one area cascading positively or negatively. This is consistent with common descriptions of recovery as non‐linear with peaks and troughs (Leamy et al., Citation2011).

Another important consideration is the current study's youth recover model's contribution to the limited research base exploring recovery and young people. Two previous studies with different age ranges to the current study utilised inductive designs to identify recovery themes that encapsulated a process of moving from an initial point of distress, detachment and confusion towards greater wellbeing, awareness and autonomy (Barnett & Lapsley, Citation2006; Simonds et al., Citation2014). Comparisons with Simonds et al's research need to be premised with the fact that their study utilised a sample of young people aged 14–16-years diagnosed with anxiety and depression. Despite this difference underlying themes were highly consistent with the exception of Simonds et al.’s third theme titled ‘anticipation of future self’, which revealed that younger adolescents appeared to lack a positive future orientation beyond the hope for symptom eradication. This also contrasted with findings from adult studies that typically displayed adults possessing a capacity to anticipate and hold hope for the future despite the presence of symptoms. Certainly there have been other studies, which have found that children under 16-years have a reduced capacity for future orientation (Steinberg et al., Citation2009). However, the current study found the narratives of young people aged 18–23-years old had moved to a point of anticipation of future challenges associated with having a mental illness that occurred concurrently with hope and expectation for improvement. This difference may be related to developmental differences between the samples, with increased experience and additional developmental years leading to this capacity to envisage a future self that is able to better cope with mental illness.

The outlined model of recovery provides a holistic definition of recovery identifying it as part of a personal journey involving the physical and social ecological system. Importantly, this journey begins before any formal diagnosis is received and continues after that point. It is posited that recovery, like development, occurs in a dynamic ecological context that includes both adversity and trauma, barriers to human potential, and positive and promoting factors that support interactive personal processes of recovery. It is in fact contended that youth recovery is best conceptualised as an interactive process that includes personal and ecological factors and caution should be applied in viewing recovery solely from a personal perspective without reference to context.

The focus of the recovery movement, which has been on the importance of the personal process and individual experience, was formed in response to the historical dominance of professional power and clinical recovery (Glover, Citation2012). However, this history may have unintentionally reinforced the personal component of recovery over a more unified definition of recovery that includes personal and environmental interaction. Based on the current findings a unified definition of recovery that includes a dynamic environmental and personal process is of particular importance in reference to young people who are still in a key developmental period and who rely on others and interact heavily with external factors to progress through developmental milestones. Application of an ecological systemic lens to the recovery conceptualisation may resolve concerns raised by Friesen (Citation2007) that commonly used recovery models are overly person‐centred to the detriment of family‐centred work. It also recognises the varying degrees of dependence of many young people on systems of care, such as family or school professionals, as they progress through this developmental stage (MHCC, Citation2014).

Finally, the results have implications for the manner in which professionals conceptualise their roles, as not only supporting personal adaptation and accommodation to an illness, but to support reintegration of young people who may be disengaged from social and economic activities such as family and peer relationships, education and work. This is crucial in supporting psycho‐social development, social and economic participation and thereby recovery.

Limitations of the current research include the lack of differentiation between individuals at different points in recovery and the small sample size. In order to determine the extent of generalisability of these findings further research is required with other samples of similar cohorts to confirm themes identified. Future research could further explore the composition of recovery narratives in terms of psycho‐social development, adaptation and accommodation to mental illness.

In conclusion, it is important to critically interrogate the foundational definitions and conceptualisations of recovery in relation to their relevance for supporting young people with severe mental illness. The current research offers the first attempt at a thematic model of recovery developed with such young people, that displays the interactive nature of the individual within an ecological context. Based on the findings, interventions aimed at supporting young people with severe mental illness may attempt to both target opportunities and barriers within each individual's ecological context and support the individual young person's personal processes and journey towards recovery.

REFERENCES

- Alegria, M., Jackson, J., Kessler, R., & Takeuchi, D. (2001–2003). Collaborative psychiatric epidemiology surveys, United States. Princeton, NJ: Inter‐University Consortium for Political and Social Research. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR20240.v8

- Andresen, R., Oades, L. G., & Caputi, P. (2003). The experience of recovery from schizophrenia: Towards an empirically validated stage model. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 37, 586–594.

- Anthony, W. A. (1991). Recovery from mental illness: The new vision of services researchers. Innovations and Research, 1(1), 13–14.

- Anthony, W. A. (1993). Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990’s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, 16(4), 11–23.

- Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2007). Mental health of young people (No. BS 4840.0). Retrieved from http//http://www.abs.gov.au

- Barnett, H., & Lapsley, H. (2006). Journeys of despair, journeys of hope. Young adults talk about severe mental distress, mental health services and recovery. New Zealand: Mental Health Commission Research Report. Wellington. Retrieved from https://www.mentalhealth.org.nz/assets/ResourceFinder/journeys‐of‐despair‐journeys‐of‐hope‐2006.pdf

- Bassilios, B., Telford, N., Rickwood, D., Spittal, M. J., & Pirkis, J. (2017). Complementary primary mental health programs for young people in Australia: Access to allied psychological services (ATAPS) and headspace. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 11, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-017-0125-7

- Braun, V., & Clark, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research, 3(2), 77–101.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Corrigan, P. W. (2002). Empowerment and serious mental illness: Treatment partnerships and community opportunities. Psychiatric Quarterly, 73(3), 217–228.

- Davidson, L. (2003). Living outside mental illness qualitative studies of recovery in schizophrenia. New York, NY: NYU Press.

- Davidson, L. (2016). The recovery movement: Implications for mental health care and enabling people to participate fully in life. Health Affairs, 35, 1091–1097. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0153

- Davidson, L., Lawless, M. S., & Leary, F. (2005). Concepts of recovery: Competing or complementary? Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 18, 664–667.

- Davis, M., Koroloff, N., & Ellison, M. L. (2012). Between adolescence and adulthood: Rehabilitation research to improve services for youth and young adults. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 35(3), 167–170.

- Department of Health (2009). National mental health plan: An agenda for collaborative government action in mental health. Retrieved from http://www.health.gov.au/internet/publishing.nsf/Content/mental-pubs

- Eccles, J. S., Barber, B. L., Stone, M., & Templeton, J. (2001). Adolescence and emerging adult‐hood: The critical passage ways to adulthood. In M. H. Bornstein, L. Davidson, & C. L. Keyes (Eds.), Well‐being: Positive development across the life‐span. (pp. 383–406). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Friesen, B. A. (2007). Recovery and resilience in children's mental health: Views from the field. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 31(1), 38–48.

- Gilburt, H., Slade, M., Bird, V., Oduola, S., & Craig, T. (2013). Promoting recovery‐oriented practice in mental health services: A quasi‐experimental mixed‐methods study. BMC Psychiatry, 13, 176.

- Glover, H. (2012). Recovery, lifelong learning, empowerment & social inclusion: Is a new paradigm emerging?. In P. Ryan, S. Ramon, & S. Greacen (Eds.), Empowerment, lifelong learning and recovery in mental health: Towards a new paradigm. London, England: Palgrave.

- Gorter, J. W., Stewart, D., Smith, M. W., Kingam, G., Wright, M., Nguyen, T., … Swinton, M. (2014). Psychosocial outcomes and mental health for youth with disabilities: A knowledge synthesis of developmental trajectories. Canadian Journal of Mental Health, 33(1), 45–61.

- Jacobson, N., & Greenley, D. (2001). What is recovery? A conceptual model and explication. Psychiatric Services, 52(4), 482–485.

- Kaewprom, C., Curtis, J., & Dean, F. P. (2011). Factors involved in recovery from schizophrenia: A qualitative study of Thai mental health nurses. Nurse Health Sciences, 13(3), 323–327.

- Lal, S. (2010). Prescribing recovery as the new mantra for mental health: Does one prescription serve all? Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 77(2), 82–89.

- Leamy, M., Bird, V., Le boutillier, C., Williams, J., & Slade, M. (2011). A conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 199, 445–452.

- Macpherson, R., Pesola, F., Leamy, M., Bird, V., Le boutillier, C., Williams, J., & Slade, M. (2016). The relationship between clinical and recovery dimensions of outcome in mental health. Schizophrenia Research, 175, 142–147.

- Mental Health Coordinating Council (2014). Recovery for young people: Recovery orientation in youth mental health and child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS): Discussion paper. Sydney, NSW: MHCC. Retrieved from http://www.mhcc.org.au/media

- National Institute for Mental Health in England. (2005). Guiding statement on recovery. Retrieved from http://studymore.org.uk/nimherec.pdf

- Oades, L. G., Deane, F. P., Crowe, T. P., Lambert, G., & Kavanagh, D. (2005). Collaborative recovery: An integrative model for working with individuals who experience chronic and recurring mental illness. Australasian Psychiatry, 13(3), 279–284.

- Onken, S. J., Craig, C. M., Ridgway, P., Ralph, R. O., & Cook, J. A. (2007). An analysis of definitions and elements of recovery: A review of the literature. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 31(1), 9–22.

- Paus, T., Keshavan, M., Giedd, J. N., & Paus, T. (2008). Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9, 947–957. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2513

- Ralph, O., & Corrigan, P. W. (2005). Recovery in mental illness: Broadening our understanding of wellness. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Books.

- Rankin, S., & Petty, S. (2016). Older adult recovery: What are we working towards? Mental Health Review Journal, 21(1), 1–10.

- Robinson, E. (2006). Young people and their parents: Supporting families through changes that occur in adolescence. Australian Family Relationships Clearinghouse (AFRC) briefing, no. 1. Barton, ACT: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Roe, D. (2001). Progressing from patienthood to personhood across the multidimensional outcomes in schizophrenia and related disorders. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 189, 691−699.

- Sawyer, S. M., Azzopardi, P. S., Wickremarathne, D., & Patton, G. C. (2018). The age of adolescence. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 2(2), 223–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30022-1

- Schilling, E. A., Aseltine, R. H., & Gore, S. (2008). The impact of cumulative childhood adversity on young adult mental health: Measures, models, and interpretations. Social Science & Medicine, 66, 1140–1151.

- Schrank, B., & Slade, M. (2007). Recovery in psychiatry. Psychiatric Bulletin, 31, 321–325.

- Silverstein, S. M., & Bellack, A. S. (2008). A scientific agenda for the concept of recovery as it applies to schizophrenia. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 1108–1124.

- Simonds, L. M., Pons, R. A., Stone, N. J., Warren, F., & John, M. (2014). Adolescents with anxiety and depression: Is social recovery relevant? Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 21, 289–298.

- Slade, M., Leamy, M., Bacon, F., Janosik, M., Le boutillier, C., Williams, J., & Bird, V. (2012). International differences in understanding recovery: Systemic review. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 21, 353–364.

- Steinberg, L., Graham, S., O'brien, L., Woolard, J., Cauffman, E., & Banich, M. (2009). Age differences in future orientation and delay discounting. Child Development, 80(1), 28–44.

- Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration. (2010). Shared decision‐making in mental health care: Practice. Research and future directions (No. 09‐4371). Retrieved from http://store.samhsa.gov/product/SharedDecision-Making-in-Mental-Health-Care/SMA09-4371

- Tew, J., Ramon, S., Slade, M., Bird, B., Melton, J., & Le, B. (2012). Social factors and recovery from mental health difficulties: A review of evidence. British Journal of Social Work, 42, 443–460.

- Wickrama, K. A. S., Conger, R. D., Lorenz, F. O., & Jung, T. (2008). Family antecedents and consequences of depressive symptoms from adolescence to young adulthood: A life course investigation. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, 49, 468–483.

- World Health Organisation, Unesco, & Mathers, C. (2017). Global strategy for women's, children's and adolescents' health (2016–2030). Organization, 2016 (9). Retrieved from http://www.who.int/life-course/publications/global-strategy-2016-2030/en/