Abstract

Objective

Psychological crossover is the interpersonal transfer of stress. Details of how this transfer actually occurs are scarce, causing difficulties for advancement of crossover research. Crossover research has also suffered from a sampling bias, traditionally assessing the extent to which a husband's work stressors are transferred to his wife. Clearly, with the advent of both dual‐income and dual‐career partners, this research sampling method requires updating. The research reported here directly addresses these two issues and reports on an original model mapping the crossover process.

Method

The research adopted a qualitative method of enquiry in order to explore the crossover process afresh. Dyadic interviews were conducted with 16 dual‐earner couples who were both employed full time.

Results

Template analysis of the transcribed data revealed the existence of both negative (e.g., strain) and positive (e.g., well‐being) crossover experiences between the couples. These crossover experiences followed a five‐step process: (1) work event experienced; (2) impact of work event; (3) transfer of impact to partner; (4) impact on partner's well‐being and work performance; and (5) dyadic outcomes.

Conclusions

This research advances recent discussions of the crossover process by supporting the five‐step Crossover Process Model. The findings support the occurrence of both negative and positive crossover of emotions, although negative work stressors were found to be the most commonly experienced initiator of crossover. Importantly, this research demonstrated that neither the gender of the initiating partner nor the gender of the recipient partner significantly influenced the crossover process.

Key words:

A pertinent source of occupational stress arises from the ‘stress transmission’ process via direct exposure to a work colleague's or a spouse's stress experiences. Direct crossover is the primary stress transmission process and is defined as: ‘the interpersonal process that occurs when job stress or psychological strain experienced by one person affects the level of strain of another person in the same social environment’ (Bolger, DeLongis, Kessler, & Wethington, Citation1989, p. 175). Both the theoretical explanations of crossover and the informed practices to reduce this stressor have received comparatively minimal scholarly attention as compared to either the primary causes of occupational stress (i.e., job demands and job resources) and other established sources of occupational stress such as work–life balance (O'Driscoll & Brough, Citation2010). This scarcity of attention is partly due to the difficulty of empirically assessing the theoretical explanations of crossover. Current knowledge does not explain, for example, the specific details of when or how crossover is experienced or the outcomes of crossover on each partner and on their relationship. The specific mechanism of how strain is actually transferred between partners also remains unclear. The current research addresses these knowledge gaps and reports the results of an investigation that reconsidered the specific pathways by which crossover occurs.

Work conducted by Westman (Westman, Citation2001; Westman & Etzion, Citation1995; Westman, Etzion, & Danon, Citation2001; Westman & Vinokur, Citation1998) described a conceptual crossover model based on role theory (Katz & Kahn, Citation1978) and focused on an inter‐individual focus of analysis (i.e., dyads). Westman described crossover as a complex, interchangeable, and multifaceted process, which commences at the individual level and transfers to a partner within the home or work environments. Westman reasoned that, due to the interdependent nature of relationships, crossover between individuals is most appropriately assessed with dyads as the unit of analysis. Westman's theoretical explanation of crossover described three mechanisms (direct crossover, indirect crossover, and shared stressors) by which positive or negative experiences, emotions, and resources are transferred between individuals within the same social and organisational contexts. Direct crossover describes the interpersonal transfer of emotional states by empathy, commonly demonstrated by the transfer of strain between spouses or co‐workers. Indirect crossover describes how the transfer of emotions occurs through moderating variables, such as coping and social support, during interpersonal interactions, explaining, for example, the compounded impact that an overly critical colleague/spouse has on an individual experiencing strain. Finally, common stressors explain the process by which shared experiences, such as family illness or economic problems, may impact a dyad's health outcomes. The core reasoning of Westman's theoretical model (Westman, Citation2001) is that the extreme experiences of one individual can directly induce corresponding outcomes in a second individual (i.e., spouse/partner). Support for Westman's (Citation2001) explanation of stress transmission was evidenced by a spouse's levels of strain being caused primarily by the experienced occupational stress of their partner (Westman & Etzion, Citation1995). The impact of direct crossover within the work environment between work team members or between employee–supervisor dyads has also been demonstrated (Bakker, Westman, & Schaufeli, Citation2007).

Advances in the theoretical explanations of crossover are limited and most noticeably include the introduction of the two‐step ‘spillover‐crossover’ model (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2013). This model emphasised that crossover is primarily initiated by the experience of within‐individual spillover of experiences from the work to the home environment (work–family conflict or work–family enhancement) and, secondly, by the transfer (crossover) of the outcomes of these experiences to a partner. Importantly, this model was supported in samples where both male and female employees experienced strain and transferred this to their respective female/male partners (Shimazu, Demerouti, Bakker, Shimada, & Kawakami, Citation2011). Previous crossover research has traditionally suffered from sampling bias, with a predominant focus on strain experienced by male employees being transferred to their (non‐employed) wives (for a review, see Brough & Westman, Citation2018).

Advances in crossover research

Recent crossover research has expanded the focus beyond stress transmission to examine the transference of a wider range of both positive and negative emotions between spouses and/or colleagues. Evidence has demonstrated that concepts including incivility (Ferguson, Citation2012), work harassment (Dionisi & Barling, Citation2015), emotional exhaustion (Wirtz, Rigotti, Otto, & Loeb, Citation2017), resilience (Chen, Westman, & Hobfoll, Citation2015), and burnout and work engagement (Westman & Chen, Citation2017) can also be transmitted via an interpersonal crossover process. The recent emphasis on the transfer of resources is particularly pertinent. For example, Neff, Sonnentag, Niessen, and Unger (Citation2015) demonstrated the crossover of self‐esteem and self‐efficacy from one partner to another, describing how a partner can function as a ‘resource supply’ for their spouse. By transferring resources from the individual to their spouse, the spouses’ levels of work engagement were also subsequently enhanced, creating a spiral of gains that illustrates, for example, how resource caravans function (Hobfoll, Citation1989). The finding that high levels of resources are not only beneficial for an individual's outcomes but also impact his or her partner's outcomes via a crossover process has practical implications for dual‐earner couples and their organisations. That is, supporting employees’ work resources may positively affect their partner's resources and subsequent levels of work engagement, leading to their improved work performance.

Whilst research has demonstrated that a range of positive and negative psychological constructs occur via crossover between spouses and colleagues, it is unclear how this process specifically transpires. More particularly, the inherent details of this crossover process, including the extent, intensity, and duration of crossover, have rarely been examined within the existing literature. The impact of the crossover of negative and positive emotions on dyadic outcomes, for example, has not yet been identified. Does the transference of negative emotions have a longer duration and/or a greater impact compared to positive emotions? What happens if both members of the dyad are experiencing occupational stress—does simultaneous negative crossover occur? Does the gender of the sender/receiver of crossover have an impact on the crossover process? These questions remain unanswered partly due to the complexity of the theoretical crossover models within this literature, which have hindered empirical assessments, and partly due to the requirement for dyadic appraisals, which adds complexity to research designs.

Aims of the current research

The research described here advances our understanding of the crossover process by addressing key existing methodological and theoretical issues. This research assesses crossover within a heterogeneous sample of dual‐career couples, including couples with and without dependent children and including both heterosexual and homosexual couples. Couples were employed in a variety of occupations to remedy the focus on male‐dominated occupations (e.g., police, military), which is predominant within this literature. This research employed a qualitative approach in order to explore the details of the crossover process with minimal restriction by documented frameworks. Importantly, the research aimed to document the transference of both negative and positive emotions between the couples and to explore the impact and duration of this crossover process on the dyad. We specifically addressed two primary research questions:

RQ1: (1a) How does the transference of negative and positive emotions occur between couples? (1b) What are the details of this crossover process?

RQ2: What are the key outcomes of crossover for the couples?

METHOD

Participants

The research adopted a purposeful research sampling technique to identify participants with four key demographic characteristics: they were in a committed and intimate relationship and were living with their partner; were at least 18-years old; both partners worked full time (minimum of 38-hr/week); and both partners were willing to participate in this research. Participants were recruited from personal acquaintances, via a Facebook social media page, and by a snowball method of participants sharing the research invitation with their own personal acquaintances.

Procedure

Each couple was invited to participate in a face‐to‐face semi‐structured dyadic interview in a location of their choice: at participants’ homes, or workplaces, or in local cafes. The interview locations were selected to ensure privacy and to minimise any interruptions (i.e., away from the family home when children would be present, at workplaces before or after normal working hours). An interview guide was devised informed by the a priori themes derived from Westman's (Citation2001) crossover model and other pertinent literature. The interview guide consisted of nine groupings of questions, including: demographics, communication, common stressors, positive and negative crossover, and empathetic reactions. The open‐ended questions aimed to deconstruct the crossover process, for example: ‘Can you tell me about a time either of you have come home after having a stressful experience at work?’ and ‘In what ways do you feel that the stress/strain of work affected the relationship?’ Interview questions also investigated the key interpersonal factors pertinent to the crossover process and included questions relating to social support, coping strategies, and communication characteristics between the dyad, including: ‘What do you think are the benefits of communicating about work to each other as opposed to others?’ Positive‐framed interview questions included: ‘Can you tell me about a time when you came home from work after having a positive experience?’ Questions assessing empathetic reactions included: ‘How do you deal with each other's work experiences (positive and negative)?’ The interviewer was not formally trained in interviewing procedures but conducted a ‘practice interview’ to pilot both the interview guide and the interview process. This pilot interview was conducted with an opportunity sample of one dyad. Feedback from this pilot interview primarily resulted in the interview guide being revised to include a greater number of demographic questions (e.g., length of relationship). The length of each interview varied between 45 and 90-min. Each interview was audio recorded and transcribed. Each interview transcript was made available to the respective dyad for content checking, producing only minor adjustments to the transcripts.

Data analysis

The transcribed data were coded and analysed via template analysis (King, Citation2012). Template analysis refers to a technique for thematically organising and analysing qualitative data: data are coded and analysed to identify and explore themes, patterns, and relationships. Categories of themes are assessed hierarchically as higher‐ and lower‐order codes, dependent on the extent to which the participants detail the themes and the level of insight the themes provide (King, Citation2012). Compared to traditional and prescribed data analysis approaches, template analysis is a flexible technique and is useful for the analysis and interpretation of large quantities of data. Several iterations of the coding template were developed, with the final template comprising four first‐level themes, one of which (the focus of this article) was the crossover process. The themes were integrated with participants’ quotes to highlight particularly pertinent illustrations of described experiences. To address data validation, the verification strategies of bracketing, audit trails, and independent coding were undertaken (Tufford & Newman, Citation2010). For the independent coding process, an independent researcher was recruited to code a random sample of the data (n = 3 dyad transcripts; 20%) using the initial template as a guide. The researchers then compared codes and discussed variances in interpretations, resulting in some modifications to the final coding template.

FINDINGS

Demographic results

A total of N = 38 individuals (19 dyads) responded to the initial invitations to participate in this research. However, six individuals (3 dyads) subsequently withdrew their participation, leaving a total N = 32 individuals (16 dyads). Reported reasons for attrition included: time constraints due to work or non‐work commitments, inability to coordinate an opportunity for both partners to be interviewed simultaneously, and a lack of interest or reluctance from one of the partners to participate.

The 16 dyads who participated in this research (N = 32 individuals) consisted of 18 females (56%) and 14 (44%) males. Approximately one third of the interviewed dyads were in a registered marriage (n = 6 dyads; 37%), and 10 dyads (63%) identified their relationship status as de facto. Four dyads (25%) were in homosexual relationships. The participants were aged between 25 and 58-years, with a mean age of 35-years. Relationship length ranged between 2 and 37-years, with a mean relationship length of 10 years. Nearly half of the dyads had dependent children (n = 7 dyads; 43%), and these children were aged between 10 months and 21-years. The respondents were employed in a wide variety of occupations (e.g., teacher, psychologist, vet nurse, medical doctor, police officer, hospitality, and retail). Half of the sample regularly worked additional work hours each week (n = 16 individuals; 50%), and these work hours ranged between 2 and 20-hr/week, with a mean of 8 hr. Twelve individuals (38%) typically conducted these additional work hours within their home (rather than work) environments. The respondent's demographic characteristics are summarised in Table .

Table 1. Sample demographic characteristics (N = 32)

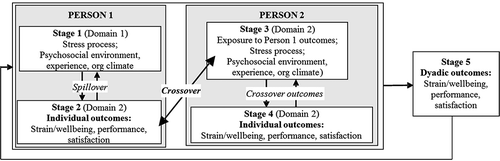

The central theme identified by this research was the transfer of occupational stressors between partners via a direct crossover pathway. This pathway constituted an intricate interplay of intra‐level and inter‐level experiences. The respondents described how this direct crossover process occurred in five discrete steps, termed the crossover process (illustrated in Fig. 1).

Step 1: Stress experience (Partner A)

Partner A described their experienced stress in one of two ways: either as a specific negative incident and/or as a perpetual (chronic) issue about their employment conditions. The majority of stressors identified by the participants focused on working overtime, shift work, working with difficult colleagues, dealing with difficult specific work issues, and taking on new work roles. For example, 12 participants (38%) identified the issue of their partner regularly performing work duties within the home environment as a stressor. These additional work hours were generally unpaid and performed outside of formally contracted hours. The participants commented on how these additional work hours often had an adverse impact on their relationship quality and maintenance. This is illustrated, for example, by these comments from participants:

Well, there's only a certain amount of time in a week, so if we're working six days; there's only a certain amount of hours, certain amount of days, and you need rest time and down time to do things like go for a drive, or have a picnic, or do anything that's ever leisure. Because it's always about working and resting, working and resting, there's no time for anything else. (Retail manager).

I used to work probably 60, 70, 80-hr a week, and so I'd get very tired and when I'd come home I was like ‘Don't talk to me, I don't want to talk to anyone, I don't want to be organised to do anything. I just want to chill out’. (Psychologist)

If it weren't for [partner] staying home in the morning until I get back home from work, we could be living in the same house and barely see each other, because of the completely opposite shifts. (Medical Registrar)

For five participants (15%), their occupational stress primarily arose due to working with difficult colleagues. These participants reported becoming physically unwell and experiencing feelings of anger and disappointment as a result of a perceived lack of support from either their organisation and/or other colleagues. For example:

Well, the boss was a bully. The guy who had the job before me was shown the door, because he might have been a bit outspoken or whatever. I just knew that when I went into that role that it could happen to me; so you had to put up with her treatment. Basically the boss had terrible mood swings and didn't like anything, bitched about other people and so on, but to the point where you would sort of bring it home. So you wouldn't sleep very well because you'd be thinking about going to work the next day, having to put up with this. So that was a bad time. (Photographer)

Step 2: Outcome of stress: Strain (Partner A)

The second step of the crossover process focused on the intra‐level negative outcomes (i.e., strain) arising from the step 1 stress experience, that is, when the experienced occupational stress continued to impact the same person within a different domain. We found that, rather than a person directly transferring their strain onto their partner, they first attempted to alleviate their experiences of strain themselves. The participants identified how the consequences of stress spillover within their home environments was typically manifested by their negative moods, fatigue, rumination of work events, and being emotionally unavailable. For example:

At times when work gets harder and I've had a hard day with the kids, I sort of notice when I get home I might get a bit cranky or a bit grumpy. (Teacher)

If I've had a really bad day I need a good two hours of just “Don't come near me, don't talk to me, don't get anywhere within two metres of my bubble. Leave me alone. Don't ask me questions’. (Administration Manager)

Most of the participants (n = 28; 80%) identified that they continued to think about their occupational stress experience after formally concluding work. Participants frequently mentioned how negative work events continued to linger in their minds as they would rethink the scenario or come up with alternative outcomes to what had actually eventuated. For example:

It definitely can affect you though. It's always in the back of your mind, ‘I've got to go to work tomorrow, I've got to go to work tomorrow’. Most days you can shut it off, forget about it, and go into home mode. But some days, it's just too difficult, if really affects you that evening, and then the next day too usually. (Safety Officer)

The second common mechanism utilised by the participants was segmentation, employed to purposefully separate the participant's work and home domains. The findings indicated that many of the participants purposefully created boundaries and compartmentalised their work obligations in order to manage their responsibilities across multiple roles. Segmentation occurred either due to external factors (e.g., employment regulations and work confidentiality issue) or as a purposeful coping strategy by Partner A. These participant's comments are illustrative of this segmentation process:

I've learnt over the last four or five years now to literally switch off and disconnect. There are days that I can't, so they are hard, because something really nasty has happened, but when I'm at work, I'm at work. When I leave that place, I literally switch police off. It's the weirdest thing, I can do it; it's just off. (Police Officer)

I've had to learn to confine my work to work, because children don't understand work. They want mum and dad. So I have to come home with big smiles, or cuddles, or console, or cheer up, or play. (Administration Manager)

Step 3: Crossover

Regardless of Partner A's best attempts to prevent the transfer of his or her strain (step 2), crossover of Partner A's strain to Partner B was identified in the interviews. Half of the participants (50%) expressed experiencing negative emotions as a result of their partners experiencing strain. They described mirroring the mood presented by their partner as a sign of empathy and emotional support. This response by a participant aptly illustrates the stress transmission (crossover):

I think if he still seems down, I think I really take it on board. If I can tell his mood is a bit down, and I can't make him feel better, yeah, I do get a bit worried about him, and I think I can be a bit frustrating for him, if I keep saying ‘What's wrong? What can I do?’ There's nothing I can do, so I think sometimes that can be a bit frustrating. (Marketing Officer)

Negative empathic reactions were also prevalent among dyads that described experiencing occupational stress simultaneously. Four dyads (25%) described situations in which both partners had returned home feeling negatively impacted by occupational stress. The mutual stress resulted in each partner becoming even more irritable, as well as having less tolerance and empathy for each other's own experiences, for example:

I've found that if one of us is experiencing a stressful period of time and the other person is as well; looking back, we haven't recognised that other person's stress, we're sort of focused on our own stress. (Academic)

Step 3 also demonstrated that, while Partner B detected a negative change in Partner A's behaviour or mood state, Partner B did not necessarily emulate the negative state or take it on as their own; that is, Partner B is not therefore necessarily a passive recipient of strain.

Step 4: Crossover outcomes (Partner B)

The Partner B participants identified that strain generated at home from their partner could be transferred to their own workplace. Thus, negative interactions with their partner had a subsequent negative impact on their own mood and interactions with their work colleagues and/or hindered their work performance. Themes were also identified about how an inadequate understanding of an individual's support needs, coping, and communication strategies from their partner compounded the conflict between the partners. Without the relevant context surrounding an individual's experienced strain, his or her partner often took personal offence to their behaviour and made negative attributions about their partner and the state of their relationship. For example:

If we've had a fight, or I had a fight with my family, I can't let that go at work, it really affects me and my performance there. I just can't block that out. (Teacher)

Step 5: Relationship (dyadic) outcomes

Finally, step 5 occurred at the dyadic level (both partners). The impact of crossover on their relationship was commonly influenced by the ways in which Partner A's initial stress was perceived by Partner B and how this stress was collectively managed by the couple. The findings identified the importance of differentiating specific contributions from each partner and the impact of these contributions on both individual and dyadic outcomes. Common negative dyadic outcomes included: inadequate quality time spent together and perception that the relationship was perceived to be a low priority. Fundamental to this step was the notion that not all negative events produced negative outcomes. That is, the sharing of occupational stress provided the opportunity for partners to face adversity together and provided them with opportunities to develop closer bonds through the process of overcoming a common challenge. It is apparent that responding to stressful events takes up time and energy, resources that are not limitless. However, spending quality time with one's partner and working through issues together can be a useful tool to aid relationship functioning and maintenance. Consequently, we found that the allocation of time spent managing the original occupational stress often encouraged experiences of transparency, closeness, and commitment between the dyad.

Positive crossover

Similar to the theme of negative work stressors, numerous positive work events were also recalled in all of the interviews. The impact of these positive events can also be mapped onto the crossover process via the five‐step process described above. Positive experiences were commonly perceived as the absence of negative experiences, that is, three participants commented on how simply the absence of negative events or even getting through the working week was enough for them to transfer a positive mood and energy to the partner at home. However, most of the positive events were represented by separate and significant personal achievements; for example: ‘I guess submitting my thesis was kind of positive’ (Research Fellow); ‘When I've had clients, when I send them an invoice and they write me out a cheque straight way’ (Builder). Receiving positive feedback on work performance was also a common positive experience identified by the majority (n = 26; 80%) of participants. This included experiences of an encouraging performance review; the attainment of a work promotion or contract; attending work activities; or verbal feedback from clients, managers, or work colleagues. For example:

We were doing performance reviews, and mine went really well; there's definitely a difference when I come home. (Engineer)

Both the spillover of positive events from work to home and the positive impact of Partner's A good mood on Partner B (crossover) were both described as being easily identifiable. For example:

I think when he's particularly had big projects or good reviews, I could tell when he came in the door, he was so chuffed (Teacher)

When it is a positive thing for me, like if I have positive news, I do feel as though it is being reciprocated. I can see [Partner] perking up as well. I can see the empathy there. (OHS Officer)

DISCUSSION

The findings reported here support a five‐step process of interpersonal crossover between the couples for the transferences of both positive and negative emotions (Research Question 1). This five‐step crossover process has been described elsewhere (Muller & Brough, Citation2017), and this article provides the first assessment of research findings to support this model. The Crossover Process Model describes the transfer of emotions via both an interpersonal spillover and an intrapersonal crossover process and, importantly, includes a final step focused on the outcomes for the dyad. For dyads in a personal relationship, these outcomes predominantly focus on relationship satisfaction and commitment, even when the initiating stressor was a negative (rather than a positive) experience (Research Question 2). This finding supports the evidence that the effective management of negative events by the couple can be a catalyst for achieving positive relationship outcomes, including opportunities to strengthen dyadic bonds and identities (e.g., Muller & Brough, Citation2017). It is anticipated that assessments of this model with workplace dyads could elicit similar positive dyadic experiences focused on work performance and job satisfaction outcomes, as suggested by the emerging crossover research conducted with work colleagues (e.g., Wirtz et al., Citation2017). These findings reinforce occupational stress explanations, which describe how a focus on the cognitive appraisal of the stressor, rather than the stressor per se, can have a greater impact for stress outcomes, including positive outcomes such as individual growth and resilience (Biggs, Brough, & Drummond, Citation2017; Lazarus, Citation1966). We acknowledge that the application of this Crossover Process Model to the assessment of positive growth within workplace dyads would be useful in order to identify how positive work attitudes and job performance can best be achieved when experiencing a common occupational stressor.

The Crossover Process Model identifies a clear stage when interpersonal crossover occurs, clarifying some existing confusion about this specific transfer of emotions. Our findings have illustrated, for example, that neither the gender of the initiating crossover partner or the relationship length of the dyad were relevant for the occurrence of crossover. It is pertinent that crossover initiated by both males and females was found to be equally likely and that the five‐step crossover process occurred regardless of the gender of the second partner. These findings assist in addressing the sampling bias within crossover research, which has traditionally focused on how occupational stress experienced by male workers impacts their female spouses. Our findings also emphasise the need for future crossover research to focus on samples of dual‐career couples and the assessment of dual occupational stress experiences in order to provide a more balanced and informed context for the work–home crossover process. We recognise, for example, recent research that examines crossover experienced by couples working within the same (military) industry (e.g., Huffman, Craddock, Culbertson, & Klinefelter, Citation2017). We suggest that an expansion of this research beyond military contexts is valuable in order to identify the advantages and disadvantages of experienced common occupational stressors on both relationship satisfaction and work performance outcomes for couples employed within various contexts.

We also acknowledge that the majority of crossover research remains focused on identifying the negative and positive emotions that are able to be transferred interpersonally. Whilst this research listing emotions is valuable, we suggest an overlooked avenue of inquiry, the identification of the specific mechanisms of the crossover process. What are the characteristics of either the specific initiating negative/positive experience and/or the dyad that encourages crossover? Can crossover occur in dyads lacking empathy with each other? Which individual differences significantly influence the impact of crossover? The qualitative approach adopted by the current research enabled a focus on the exploration of this crossover mechanism. The findings produced valuable insights distinguishing between intra‐level and inter‐level contributions whilst acknowledging the individual differences that commonly impact the crossover process (e.g., dyadic levels of social support, coping, and communication reported in Muller & Brough, Citation2017). We recognise that the illumination we have provided on the crossover process is a useful starting point for such research enquiries to be assessed in greater depth by future qualitative and quantitative research approaches.

Research limitations

One limitation of the current research was the selection process undertaken to recruit the participant dyads. We acknowledge that dyads who were satisfied and confident in their relationships were most likely to have participated in this research and that this self‐selection may have influenced the research findings. This issue of relationship satisfaction was not directly assessed in the current research. Instead, the interviewer perceived only an inherent subjective assessment of the dyad's level of relationship satisfaction, that is, an informal assessment based on the way the dyad interacted with, and responded to, one another and the degree of good humour exhibited between each dyad during the interviews. From our observations, it appeared that dyads experiencing serious relationship problems did not participate in this research and, for example, declined to participate in the research at the recruitment stage when it was apparent that the research involved a joint interview with their partner. Future research is recommended to sample dyads with a range of relationship satisfaction levels in order to assess how much the crossover process is influenced by dyads with high and low levels of relationship satisfaction, although we also acknowledge that recruitment may be difficult and should be planned carefully. We also recommend that these dyads be sampled from both the home and work environments to assess the impact of relationship satisfaction upon the crossover process occurring within both personal relationships and within work relationships between colleagues.

A second limitation of the current research was the conducting of dyadic interviews only. Whilst this interview method was purposefully adopted in order to assess the couple's interactions (reported elsewhere Muller & Brough, Citation2017), we acknowledge that the presence of partners may have influenced the answers provided to the interview questions. An alternative method for qualitative dyadic data collection focuses on multiple interviews, where both sole and dyadic interviews are conducted, and the data are subsequently assessed for consistency by the researcher (e.g., Arksey, Citation1996). However, we also acknowledge the laborious nature of this multiple interview approach for the research participants, the researcher, and the independent coder/s.

CONCLUSIONS

This research was successful in identifying the details of the crossover process experienced by dual‐career couples. The research supported a five‐step Crossover Process Model characterised by stressor experience, intrapersonal spillover, interpersonal crossover, partner outcomes, and dyad outcomes. The findings also supported the occurrence of both negative and positive crossover of emotions, although negative work stressors were found to be the most commonly experienced initiator of crossover. Importantly, this research demonstrated that neither the gender of the initiating partner nor the gender of the recipient partner significantly influenced the crossover process. This research advances recent discussions of the crossover process by supporting the five‐step Crossover Process Model and recommending it for further empirical assessment. Whilst this research focused on how occupational stress, via the crossover process, impacts outcomes for personal relationships, we also acknowledge and encourage the application to workplace relationships and outcomes.

REFERENCES

- Arksey, H. (1996). Collecting data through joint interviews. Social Research Update, Winter 15, 1–8.

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2013). The spillover‐crossover model. In J. G. Grzywacz & E. Demerouti (Eds.), New Frontiers in work and family research. (pp. 54–70). Hove, Sussex, England: Psychology Press.

- Bakker, A. B., Westman, M., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2007). Crossover of burnout: An experimental design. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 16(2), 220–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320701218288

- Biggs, A., Brough, P., & Drummond, S. (2017). Lazarus and Folkman's psychological stress and coping theory. In C. L. Cooper & J. Quick (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of stress and health: A guide to research and practice. (pp. 351–364). London, England: Wiley.

- Bolger, N., De longis, A., Kessler, R. C., & Wethington, E. (1989). The contagion of stress across multiple roles. Journal of Marriage and Family, 51(1), 175–183. https://doi.org/10.2307/352378

- Brough, P., & Westman, M. (2018). Crossover, culture and dual‐earner couples. In K. Shockley, W. Shen, & R. Johnson (Eds.), Handbook of global work and family. (pp. 629–645). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Chen, S., Westman, M., & Hobfoll, S. E. (2015). The commerce and crossover of resources: Resource conservation in the service of resilience. Stress and Health, 31(2), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2574

- Dionisi, A. M., & Barling, J. (2015). Spillover and crossover of sex‐based harassment from work to home: Supervisor gender harassment affects romantic relationship functioning via targets' anger. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(2), 196–215. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1969

- Ferguson, M. (2012). You cannot leave it at the office: Spillover and crossover of coworker incivility. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(4), 571–588. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.774

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources. A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. The American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.44.3.513

- Huffman, A. H., Craddock, E. B., Culbertson, S. S., & Klinefelter, Z. (2017). Decision‐making and exchange processes of dual‐military couples: A review and suggested strategies for navigating multiple roles. Military Psychology, 29(1), 11–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/mil0000135

- Katz, D., & Kahn, R. L. (1978). The social psychology of organizations. (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Wiley.

- King, N. (2012). Doing template analysis. Qualitative organizational research: Core methods and current challenges. In G. Symon & C. Cassell (Eds.), Qualitative organizational research: Core methods and current challenges. (pp. 426–450). London, England: Sage.

- Lazarus, R. (1966). Psychological stress and the coping process. New York, NY: McGraw‐Hill.

- Muller, W., & Brough, P. (2017). Work, stress, and love: Investigating crossover through couples’ lived experiences. In J. Fitzgerald (Ed.), Foundations for couples’ therapy: Research for the real world. (pp. 464–474). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Neff, A., Sonnentag, S., Niessen, C., & Unger, D. (2015). The crossover of self‐esteem: A longitudinal perspective. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24(2), 197–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432x.2013.856298

- O'driscoll, M., & Brough, P. (2010). Work organisation and health. In S. Leka & J. Houdmont (Eds.), A textbook of occupational health psychology. (pp. 57–87). Chichester, England: Wiley‐Blackwell.

- Shimazu, A., Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Shimada, K., & Kawakami, N. (2011). Workaholism and well‐being among Japanese dual‐earner couples: A spillover‐crossover perspective. Social Science & Medicine, 73(3), 399–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.049

- Tufford, L., & Newman, P. (2010). Designing qualitative research. London, England: Sage.

- Westman, M. (2001). Stress and strain crossover. Human Relations, 54(6), 717–751. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726701546002

- Westman, M., & Chen, S. (2017). Crossover of burnout and engagement from managers to followers. In C. L. Cooper & J. C. Quick (Eds.), The handbook of stress and health: A guide to research and practice. (pp. 236–251). London, England: Wiley.

- Westman, M., & Etzion, D. (1995). Crossover of stress, strain and resources from one spouse to another. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 16(2), 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030160207

- Westman, M., Etzion, D., & Danon, E. (2001). Job insecurity and crossover of burnout in married couples. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(5), 467–481. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.91

- Westman, M., & Vinokur, A. D. (1998). Unraveling the relationship of distress levels within couples: Common stressors, empathic reactions, or crossover via social interaction? Human Relations, 51(2), 137–156.

- Wirtz, N., Rigotti, T., Otto, K., & Loeb, C. (2017). What about the leader? Crossover of emotional exhaustion and work engagement from followers to leaders. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(1), 86–97. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000024