Abstract

Objective

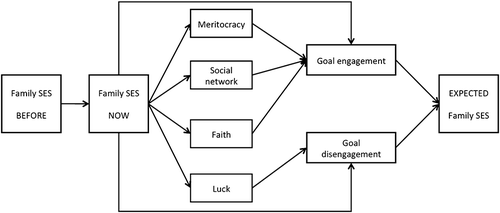

Household theory of labour migration assumes that the decision to work in another country is a family's strategy to improve prospects of socio‐economic mobility. We inquired into the social cognitive processes associated with this goal by applying model of pathways to socio‐economic mobility, but extending the types of causal conceptions related to social mobility that are considered important in the Philippine context.

Method

We surveyed 246 Filipino migrant workers in Macau, who answered questions about perceptions of the socio‐economic status of their family (before they worked abroad, presently, and 10 years after), socio‐economic mobility causal conceptions (merit, luck, faith in God, social networks), and goal‐attainment strategies (goal engagement, goal disengagement).

Results

Migrant workers expect improved socio‐economic status of their families compared to before, and they expect further improvement after 10 years. They endorsed faith in God and meritocracy as important causal factors to mobility. Path analysis indicated two pathways to socio‐economic mobility expectations: (1) engagement‐promoting pathway—involving faith in God and meritocracy as causal conceptions related to goal engagement, and higher socio‐economic mobility expectations and (2) disengagement‐promoting pathway—involving luck as causal conception related to goal disengagement, and lower socio‐economic mobility expectations.

Conclusion

Although working abroad is fraught with uncertainties, Filipino migrant workers aspire for upward socio‐economic mobility for their families, which they seek to attain by working hard and persistence, which in turn relate to causal conceptions of mobility that involve controllable factors.

What is already known about the topic?

Economic theories assume that migrant labour decisions are family strategies to improve prospects of social mobility.

A general social cognitive model suggests engagement‐promoting and disengagement‐promoting pathways to social mobility expectations that involve causal conceptions and goal attainment strategies.

Although there is research on mental health concerns of migrant workers, not much is known about their psychological processes associated with their social mobility expectations.

What this topic adds?

The results provide evidence for the applicability of the general social cognitive model to the case of migrant workers.

The results suggest the Filipino migrant workers who believe in meritocracy and faith in God as causes of socio‐economic mobility tend to engage and persist in their goals, and to hold higher socio‐economic mobility expectations—indicating an engagement‐promoting pathway.

The results provide evidence for social cognitive processes that may support the assumptions of economists' household theory of migrant labour.

Most recent estimates by the International Labour Organisation (ILO, Citation2015) suggest that there are about 150.3 million migrant workers in different parts of the world. Household theory of labour migration (Massey, 1994; Stark, 1984) assumes that the decision to migrate is actually a strategy adopted by families or the household unit to increase the flow of income. This theory has been applied to understand Filipino labour migration, which has steadily increased since the 1970s. The most recent government estimates (Philippine Statistics Authority, 2017) indicate that 2.2 million Filipinos (more than 2% of the national population) are working overseas, and studies indicate that the decision to migrate is a family strategy to improve their financial status (Lauby & Stark, 1988). In particular, for labour migrants from low‐income families, migration was done in the hopes of providing for subsistence of their relatives, but more generally for most other labour migrants, migration is undertaken in the hopes of increasing the family's social mobility (Tacoli, 1996). But how do Filipino migrant workers think about the pathways towards their families' better socio‐economic future? In this study, we inquire into Filipino migrant workers' beliefs and expectations related to their families' socio‐economic mobility. In particular, we surveyed a sample of Filipino migrant workers in Macau to examine how their beliefs about the causes of social mobility relate to either goal engagement or disengagement and their socio‐economic mobility expectations for their families.

PATHWAYS TO UPWARD SOCIO‐ECONOMIC MOBILITY

Economists have suggested that there is evidence that working overseas does lead to upward socio‐economic mobility for the Filipino workers' families. Studies indicate that there are observable improvements in the standard of living of families of Filipino migrant workers (Semyonov & Gorodzeisky, Citation2008) and also reduction in the incidences of poverty among these families (Orbeta, Jr., Citation2008). There are also indications that families of Filipino migrant workers spend more on education of children, engage in more hours of self‐employment, and are more likely to start small businesses (Yang, Citation2008)—all indicators of future social mobility. But some studies show that increased income flow to families of Filipino migrant workers does not have an impact on overall poverty gap, and might actually contribute to further income inequality (Ravanilla & De Pano Robleza, Citation2005; Rodriguez, Citation1998). That is, the improved socio‐economic status of families of Filipino migrant workers is limited to those families in the higher income range; those from lower income ranges remain poor. A Filipino deciding to work abroad is likely to know these uncertainties related to gaining social mobility by working abroad.

Though not specifically referring to migrant workers, Shane & Heckhausen (Citation2013) propose two pathways to achieve the goal of upward socio‐economic mobility: the goal engagement‐promoting pathway and the goal disengagement‐promoting pathway. Their model derives primarily from attribution theory and underscores the roles of (1) perceptions of current socio‐economic status (SES), (2) causal conceptions of SES attainment, and (3) goal attainment strategies. Perception of current SES refers to an individual's self‐definition or personal judgement of his/her status relative to others; a person may have lower subjective social status in the sense that they perceive to have less‐wealth, less‐advanced education, and/or hold less‐prestigious jobs compared to others (Côté, Citation2011). Shane and Heckhausen's model assumes that it is the subjective social status that is important in the pathways towards socio‐economic mobility, primarily because the extent to which people perceive themselves to be of lower or higher social status influences their willingness to engage in causal belief systems that either emphasise their own control or lack thereof in social mobility. These causal systems refer to causal conceptions of SES attainment that are “beliefs in the importance of causal factors for status attainment in general, and how influential they feel these causal factors are for them personally” (Shane & Heckhausen, Citation2013, p. 13). They distinguish between meritocratic‐ and luck‐oriented beliefs that differ in terms of the degree to which the person has control over the causal factors. Persons who endorse meritocracy believe that their social class standing is primarily determined by their personal skills, qualities and abilities, which are within their control. On the other hand, luck‐oriented beliefs attribute SES attainment to factors such as fate and bad luck, which are not within their control. Finally, goal pursuit strategies refer to the types of control striving processes that an individual engages in during goal attainment (Heckhausen, Wrosch, & Schulz, Citation2010). Goal engagement strategies attempt to change the world so that it fits one's needs and desires (e.g., persistence in goal striving), and these attempts may involve thoughts and actions of the individual (i.e., selective primary and secondary control) and seeking out help from others or other unusual means (i.e., compensatory primary control) to attain one's goals. In contrast, goal disengagement strategies attempt to change the individual's inner world, emotion, motivations, and thoughts (i.e., compensatory secondary control; e.g., lowering expectations).

The relationships among the three factors described above determine the type of pathway to upward mobility, and both pathways are influenced by individuals' perceptions of their current status. An engagement‐promoting pathway is a more proactive strategy towards upward mobility wherein meritocratic‐oriented beliefs associated with increased goal engagement tendencies are linked to higher expected subjective social status. The assumption is that individuals who perceive themselves to have good or high social status are more likely to endorse meritocracy and to believe that upward mobility is within their control, and this belief positively motivates their own social mobility attitudes and expectations and they proceed accordingly by modifying the external world to suit their purposes (Shane & Heckhausen, Citation2017). In contrast, in a disengagement‐promoting pathway, individuals who perceive themselves to have lower social status may be more likely to endorse luck‐oriented causal beliefs are associated with enhanced goal disengagement tendencies linked to decreased expected subjective social status. The individual believes that uncontrollable external forces are at play in one's goal pursuit and this leads the person to renegotiate expectations so as to minimise failure. The general assumption is that the attainment of higher social status is a function of one's goal‐pursuit and perceived control over the goal process (Shane & Heckhausen, Citation2013).

SOCIAL MOBILITY PATHWAYS IN THE PHILIPPINES

Shane and Heckhausen's (Citation2013) model could be used to study Filipino migrant workers' socio‐economic mobility expectations. Indeed, quantitative (Bernardo, Citation2013) and qualitative studies (Clemente, Daganzo, Bernardo, & Pangan, Citation2017; Tuason, Citation2008) on Filipino's conceptions of causes of poverty, wealth, and socio‐economic mobility affirm the factors related to meritocracy and luck. But the two qualitative studies suggest other causal factors that may need to be considered in applying the Shane and Heckhausen's model. For example, faith in God was a typical response of Filipinos who were born poor, when asked about ways of coping with their indigence (Tuason, Citation2008); faith in God was also a common response in a sample of adolescents' responses related to questions about socio‐economic mobility (Clemente et al., Citation2017). Some might think that faith in God indicates a causal belief that relates to some uncontrollable factor, and as such, represents secondary control strivings. However, the qualitative studies suggest that the act of believing may be seen as a controllable factor, as the researchers suggest that “…some responses indicate that it is the act of believing and trusting in God's will that would move one up the socioeconomic ladder” (Clemente et al., Citation2017; p. 137). This causal belief could be interpreted as indicating that an individual's own resources are not adequate to attain the socio‐economic mobility goals, and that one has to take on external resources (i.e., God's help) to attain the goal. As such, faith in God could be seen as a causal belief that indicates a form of compensatory primary control (i.e., seeking out help from a powerful supernatural force) in this particular cultural context where people put a very high level of trust on God's capacity to fulfil one's goals. In this cultural context, faith in God is seen as complementing one's own goal‐directed efforts and not a sign of giving up on one's agency and efforts; and this perspective is expressed in a very common Filipino saying, “Nasa Diyos ang awa, nasa tao ang gawa,” which translate into English as “God gives mercy to those who help themselves.”

Another causal factor that seems to indicate compensatory primary control relates to asking help from others and also giving help to others to cope with their indigence, which is mentioned in the qualitative studies of Filipinos who were born poor (Tuason, Citation2008). Asking for help to lift one's socio‐economic status aligns with discourses related to social networks as a specific form of social resources that poor families use to cope (Hill, Jobling, Pollet, & Nettle, Citation2014; Reyes & Yujuico, Citation2014). Again, there seems to be an acknowledgement that one's personal resources are not sufficient to move oneself towards higher social mobility, and help from other people could be recruited for this purpose. Working with such social networks to improve one's family's social resources reflects a primary compensatory control of the social mobility goals.

We wish to underscore, however, that the two causal factors could also represent secondary control strivings in other contexts. That is, the causal roles of social networks and belief in God could be seen as uncontrollable, and as such, belief in these factors might promote compensatory secondary control (Heckhausen et al., Citation2010). Our assumption that both causal factors involve primary compensatory control is based on the notion that these two beliefs are premised on the acknowledgement of the insufficiency of one's personal resources. Indeed, it is not unreasonable to assume that Filipino migrant workers would perceive that their personal resources towards social mobility are insufficient. The decision that they and their families made about working in a foreign land indicates that they sense that their social mobility goals are not within reach in the Philippines if they simply rely on their current personal resources. Thus, causal conceptions that faith in God and social networks help towards upward social mobility represent primary control beliefs that involve a compensatory strategy on their part. Interestingly, both social‐oriented coping and belief in God are important factors in how Filipino migrant workers deal with stress (van der Ham, Ujano‐Batangan, Ignacio, & Wolffers, Citation2014), suggesting that the factors are salient in the minds of Filipino migrant workers.

THE CURRENT STUDY

In this study, we adopt and extend Shane and Heckhausen's (Citation2013) model of socio‐economic mobility expectations to study Filipino migrant workers' beliefs, strategies and expectations. We study a sample of Filipino migrant workers in Macau, comprised mainly of low‐skilled workers. Consistent with assumptions of household theory of labour migration (Massey, Citation1994) we first hypothesize that the migrant workers would expect upward social mobility for their families in the Philippines. That is, we assume that the decision to work abroad represents the migrant worker's family's strategy to improve prospects of socio‐economic mobility, and thus, the migrant worker would expect that their work abroad would result in upward social mobility after a period of time. We operationalise this hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis 1: Expected SES ratings 10 years later would be higher than SES rating for the present time and for the time before they started working abroad.

We also hypothesised that the migrant workers would be more likely to believe that the causes of social mobility relate to factors within their control, and these refer to meritocracy (selective primary control), social networks and faith in God (both compensatory primary control). We base this hypothesis on the assumption that the strategic decision to work abroad to help improve the socio‐economic status of their families (Lauby & Stark, Citation1988) reflects a belief that that goal is controllable and within their reach. Thus we expect that:

Hypothesis 2: Agreement on the causal role of meritocracy, social network, and faith in God would be higher than agreement on the causal role of luck.

Finally, and consistent with Shane and Heckhausen's (Citation2013) model, we hypothesised that subjective social status, causal conceptions of SES attainment and goal pursuit strategies predict expectations of upward socio‐economic mobility. As their model indicates, causal beliefs and goal pursuit strategies are all influenced by the individuals' perceived status, as perceived status affects perceptions of the adaptiveness of the beliefs and strategies. As such the distal predictors in the model are the individuals' past and current subjective social class. As explained earlier, the model then highlights how the control‐related causal beliefs about social mobility are closely tied to goal engagement and disengagement, and as such these links between beliefs and goal pursuit strategies are the more proximal predictors of expected social mobility. However, we contextualised this model by extending the causal conceptions of SES attainment to reflect more culturally relevant causal conceptions of socio‐economic mobility by adding two other causal factors: social networks and faith in God. We propose that social networks and faith in God both represent compensatory primary control processes, and hypothesize that both would be part of the engagement‐promoting pathways. That is, the two factors relate to goal engagement strategies, and indirectly to socio‐economic mobility expectations. The extended model we test is summarised in Figure 1, and we summarise the specific hypotheses related to the model as follows:

Hypothesis 3: The Filipino migrant workers' past and current subjective social class, causal conceptions of SES attainment, and goal pursuit strategies predict their expected SES for their families in the future; and in particular:

Hypothesis 3a: The relationship between past family SES (prior to doing migrant work) and expected future family SES will be mediated by current family SES, causal conceptions of SES attainment, and goal pursuit strategies;

Hypothesis 3b: The relationship between current family SES and expected future family SES will be mediated by causal conceptions of SES attainment and goal pursuit strategies;

Hypothesis 3c: Consistent with an engagement‐promoting pathway, the relationship between meritocracy, social networks, and faith in God as causal conceptions of SES attainment and expected future family SES will be mediated by goal engagement;

Hypothesis 3d: Consistent with a disengagement‐promoting pathway, the relationship between luck as a causal conception of SES attainment and expected future family SES will be mediated by goal disengagement.

METHOD

Sample and participant selection

The sample comprised of 246 Filipino migrant workers in Macau (61% females) who were recruited through snowball sampling. Data from another six participants were excluded because they did not provided complete data on the key variables, thus ensuring that the statistical analysis involved no missing data. The participants were approached in their places of work, residence, or worship. Researchers and their assistants informed them about the nature and scope of the study, and assured them of full confidentiality. Only those who gave their informed consent were given the questionnaire and answered the survey during their free time and, whenever possible, in the presence of the research assistants. Respondents received a supermarket voucher as a token for their participation.

We inquired about some personal information, but providing these details was made optional because of privacy concerns on the part of some participants. As such, the description of our sample is based on only on whatever data were supplied. Among those who indicated their age, the average was 35.4 years (standard deviation (SD) = 8.8). Of those who indicated their highest educational attainment, 26.9% had secondary education or less, and 73.1% had some post‐secondary (vocational, university) education. Of those who indicated their civil status; 33.8% were single, 52.6% married, 9.4% separated, and 4.3% widowed.

We also inquired about the participants' work experience, including the number of years they have been working overseas. Eight did not provide a response, but of those who did, 16.1% have been working for 1 year or less, 48.3% for over 1–6 years, 19.5% for 7–11-years, and 16.1% for more than 12-years. Seven did not indicate their current work, and one was currently unemployed (waiting for the next job); of those who indicated their work, 53.0% were employed as domestic helpers, 15.3% restaurant workers, 12.3% security guards, 11.9% store assistants, and the rest had various jobs like car washer, dog groomer, and so on. All participants possessed a “Non‐resident Worker's Identification Card” (also called, blue card) and were authorised to stay in Macau as long as they were working.

Measures

All the scales used in this study were presented in Filipino, the national language of the Philippines. To ensure conceptual equivalence with the original English items, the instruments underwent translation and back‐translation procedures (Brislin, Citation1970). The original English scales were translated into conversational Filipino by a Filipino‐English bilingual graduate student who had an understanding of pertinent constructs and scales. Another Filipino‐English bilingual graduate student was asked to translate the Filipino translation into English. The two then met to discuss any divergences in the back translation, and made minor adjustments in the Filipino items when deemed necessary. A third Filipino‐English bilingual research reviewed the Filipino translations in comparison the original English versions. In addition to the scales described below, the participants also answered scales on hope, acculturative stress, social support, and life satisfaction, but these were not analysed in the current study as they were not pertinent to the specific model being tested (i.e., the other scale data are part of a larger database that would be used for future studies).

Socio‐economic mobility expectations

Subjective social class standing was assessed using a modified version of the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status (Adler, Epel, Castellazzo, & Ickovics, Citation2000), a pictorial measure that represents social class as a ladder. Participants were asked to choose a rung based on where they stand compared to other Filipino families in terms of education, income, and occupation. They answered the measure thrice, indicating their perceptions of their families' past (i.e., before they left the Philippines to work abroad), current (i.e., at the time of the survey), and future (i.e., after 10 years) social class standing.

Causal conceptions of SES attainment

Participants' beliefs about the causal factors that determine one's position in the social class hierarchy were measured using a 12‐item scale consisting of four subscales: meritocracy, luck, faith, and social network. The social class ladder was used as a reference in the items; each item started with the clause “where I end up on the ladder will be largely because of…” The meritocracy and luck subscales were adopted from Shane and Heckhausen's (Citation2013) causal conceptions about SES; however, in the current study, each subscale had three items, whereas, Shane and Heckhausen's meritocracy and luck subscales had four and two items, respectively. Meritocracy underscored the role of personal ability and effort as determinants of social class standing (e.g., “…how good I am at work”), while luck focused on external and uncontrollable causes (e.g., “…my destiny in life”). New items were for the faith and social network causal factors were generated by the researchers based on responses given in an earlier study on Filipino's social mobility beliefs (Clemente et al., Citation2017). Faith items attributed social class attainment to belief in a supreme being (e.g., “…my trusting in God.”); social network items emphasised social connections that benefit the self (e.g., “…the influential and powerful people I know”). Participants responded from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The internal consistency of the subscales (computed from the current sample's data) were mostly adequate: meritocracy, α = .75; faith, α = .77, and social network, α = .67. The luck subscale had lower internal consistency (α = .56) but was still included in the analysis for completeness.

Goal engagement and disengagement

Goal engagement and goal disengagement subscales assessed general goal attainment strategies that represent primary and secondary control striving, respectively (Shane & Heckhausen, Citation2013) and did not refer specifically to strivings towards socio‐economic mobility. An example of goal engagement was persistence in goal striving (e.g., “When I encounter problems, I don't give up until I solve them”); goal disengagement includes lowering aspirations (e.g., “To avoid disappointments, I don't set my goals too high”). Each subscale consisted of five items that were rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The internal consistency of the scales (computed using the current sample's data) were both adequate (engagement, α = .79; disengagement, α = .72).

Data analysis

To test the first hypothesis (H1) regarding upward social mobility expectations, we compared past, present and future SES perceptions using paired sample t‐tests. To test the second hypothesis (H2) regarding the four causal conceptions of socio‐economic mobility, we conducted a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) to test the differences among the causal conceptions, and then followed this with a post hoc pairwise comparison of means tests using Bonferroni correction. To test the third hypothesis (H3, see Figure 1), we conducted path analysis using AMOS (for SPSS 24). In specifying the model to be tested, the error terms of the four causal conceptions were allowed to covary with each other, and the errors terms of the two strategies were also allowed to covary.

RESULTS

The descriptive statistics and the correlations among the main variables (socio‐economic status ranks, causal conceptions of social mobility, and strategies) are summarised in Table . The results pertaining to the three hypotheses are presented in the following subsections.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of SES ratings, causal conceptions, and strategies

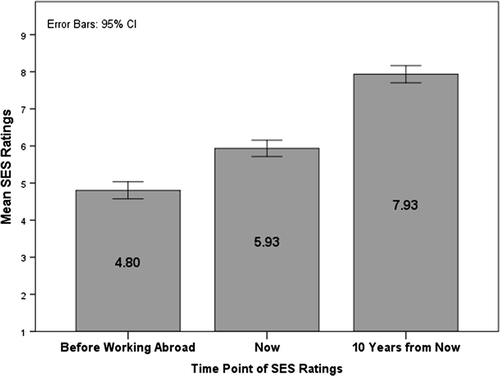

Social mobility expectations

Do the participants expect upward social mobility for their families back home? The results summarised in Figure 2 support the first hypothesis: the migrant workers' expected SES of their families in the future was significantly higher than their perceptions of their families' SES before they left the country to work abroad, t(242) = 22.50, p < .001, Cohen's d = 1.44. Participants also report significant improvements in their families' current social class standing compared to their condition before they started working abroad. Their current SES perceptions of their families were also higher than their past SES, t(243) = −11.70, p < .001, Cohen's d = 0.75, and their expected subjective social status in the future was also higher than their current SES, t(242) = 21.09, p < .001, Cohen's d = 1.35. These results suggest that the participants already perceive improvements in their family's SES and continue to expect further upward socio‐economic mobility.

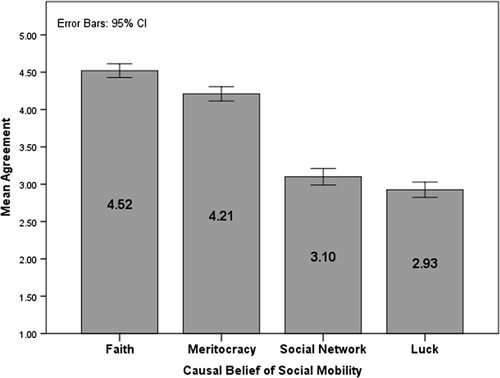

Causal conceptions of social mobility

Which among the four causal conceptions of SES attainment did the participants endorse more strongly? The means for the causal beliefs are summarised in Figure 2. The Mauchly's test in the ANOVA indicated that the assumption of sphericity was violated, χ2(5) = 27.78, p < .001, therefore degrees of freedom were corrected using Huynh‐Feldt estimates of sphericity (ε = .94). The results show that particular causal beliefs of SES attainment were more highly endorsed than others, F(2.82, 687.64) = 353.97, p < .001, η p 2 = .59 (see Figure 3). Post hoc comparisons revealed that causal conceptions related to faith in God were endorsed the highest, followed by meritocracy, social network, and luck. All pairwise comparison differences were significant at p < .001, except for the difference between social network and luck, which were significant at p = .022.

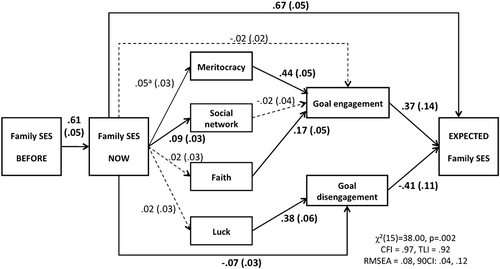

Pathways to expected social mobility

The initial path analysis indicated a bad fit between the data and the model: χ2(16) = 172.43, p < .0001, χ2/df = 10.78, CFI = .74, TLI = .42, RMSEA = .20 (90%CI:.17, .23). But the modification indexes on the original model suggested that including a direct path from current family SES and expected family SES would improve the model, so this path was added. The results of the analysis in the revised model are summarised in Figure 4, and there was an adequate fit with the data: χ2(15) = 36.00, p = .002, χ2/df = 2.40, CFI = .97, TLI = .92, and RMSEA = .08 (90%CI:.04, .11). A χ2‐difference test was conducted to compare the two models, and the results indicate that the more constrained model is better: χ2 diff(1) = 136.42, p < .0001. For good measure we also tested a model that included direct paths from past family SES to causal beliefs, among others. The path analysis of this full model indicated a poor fit with the data: χ2(14) = 150.45, p < .0001, χ2/df = 10.75, CFI = .77, TLI = .42, and RMSEA = .20 (90%CI:.17, .23). A χ2‐difference test was conducted to compare the full model and the retained model, and the results indicate that the more retained model shown in Figure 4 is better: χ2 diff(1) = 114.45, p < .0001.

As shown in Figure 4, the path linking perceived current SES with meritocracy was marginally significant, but the link with luck was not significant; these results are generally consistent with Shane and Heckhausen's (Citation2013) model. Also consistent, there was a goal engagement‐promoting pathway linking meritocracy, engagement, and expected family SES, and a goal disengagement‐promoting pathway linking luck, disengagement, and negatively with expected family SES. As regards the two additional causal factors added in the current study, current family SES was positively associated with belief in social network as a causal factor in socio‐economic mobility, but social network was not related to either engagement or disengagement. On the other hand, faith in God was not associated with current family SES, but was positively associated with goal engagement.

The indirect effects were tested using 10,000 bootstrapped samples. Collectively, current family SES, causal beliefs of socio‐economic mobility, and goal attainment strategies mediated the relationship between family SES before doing migrant work and expected family SES, standardised indirect effect = .42 (95%CI:.34, .50). Collectively, causal beliefs of socio‐economic mobility, and goal attainment strategies mediated the relationship between current family SES and expected family SES, standardised indirect effect = .03 (95%CI:.002, .06); but we should note that there was also a large direct effect of current family SES on expected family SES, standardised direct effect = .64 (95%CI:.56, .71). The relationship between meritocracy and expected family SES was mediated by engagement strategies (fitting the engagement‐promoting pathway), standardised indirect effect = .07 (95%CI:.01, .14). The same was true with the relationship between luck and expected family SES mediated by disengagement strategies (fitting the disengagement‐promoting pathway), standardised indirect effect = −.07 (95%CI:−.12, −.03]. Regarding the two new causal conceptions we tested in the model the results were mixed. The relationship between faith in God and expected family SES was mediated by engagement strategies, standardised indirect effect = .02 (95%CI: .002, .07), but the relationship between social networks and expected family SES was not, standardised indirect effect = −.004 (95%CI: −.03, .01).

Although not part of the hypotheses, it was conceivable that social mobility expectations are associated with demographic or background characteristics of the participants. Unfortunately because the provision of personal background information was made optional because of participants' privacy concerns, we did not have complete data on these demographic variables, and as such, we could not include demographic variables in the path analysis. However, we explored the correlations between several demographic variables and the main variables (causal beliefs, motivational strategies, and subjective social status ranks), excluding cases pairwise when values were missing. The only consistent correlate was education (high school or less vs college education), which positively correlated with subjective social status ratings (rs from .21 to .25) and negatively with goal disengagement (r = −.14); goal disengagement was also correlated with years working abroad (r = .15) and sex (r = −.22). Sex also correlated with goal engagement (r = −.14). No demographic variables were associated with any of the causal beliefs. These correlations suggested to us that there were no strong relationships between the variables and the main criterion variable in the hypothesized model.

DISCUSSION

Migrant workers, who leave their families of origin in order to seek for opportunities abroad, often aspire for upward socio‐economic mobility and a better life for them and their families back home. Household theory of labour migration (Lauby & Stark, Citation1988; Massey, Citation1994) suggests that sending a family member to work in a foreign country is a strategy adopted by families to improve the prospects of upward social mobility for the family. This view seems to be shared by the sample of Filipino migrant workers in Macau whose perceptions of the current SES of their families have already improved compared to before they started working abroad, and whose expected SES for their families 10 years after are even higher. Indeed, even if there are uncertainties as to whether working in a foreign country actually leads to improved socio‐economic status for all types of Filipino families who have migrant workers (Rodriguez, Citation1998), the expectation of a better future for their families seems to be clearly envisioned among the migrant workers in our sample. And as our results suggest, the expectation of a better future is related to whether they already see improvements in their family's current social status.

Our results also suggest that these envisaged better futures are not mere dreams or hollow expectation. Instead, our results provide some insights as to how the migrant workers' expectations of a better future are related to adaptive goal‐pursuit strategies. Consistent with previous models (Shane & Heckhausen, Citation2013), our results provide evidence for engagement‐promoting and disengagement‐promoting pathways towards socio‐economic mobility. The migrant workers' belief that meritocracy leads to socio‐economic mobility tends to be associated with goal engagement strategies such as being persistent in working towards their goals, which was associated with higher social mobility expectations. Thus, the migrant workers' high expectations for their family's future socio‐economic status are driven by their belief in the importance of their own efforts and abilities, and their tendency to persevere and to persist in their work. On the other hand, their belief that luck and other uncontrollable factors are at work in socio‐economic mobility tends to be associated with goal disengagement such as giving up and lowering one's expectations, which is negatively associated with social mobility expectations. Fortunately for this sample, luck was the lowest rated causal factor (endorsed much less than meritocracy), which suggests that the migrant workers in our sample were more likely to be in the engagement‐promoting pathway to higher socio‐economic expectations. Beyond the economic assumptions of household labour migration theory, our results show the applicability of social cognitive models to understand the motivated cognitive mindsets that are associated with these expectations of improved family SES associated with the decision to work abroad.

Interestingly, meritocracy was not the most highly endorsed causal factor of socio‐economic mobility among the migrant workers in our sample. We added two causal factors based on relevant previous studies in the Philippines—social network and faith in God. Social network as a causal factor was not associated with either engagement or disengagement strategies, and was thus, not indirectly related to the migrant workers' socio‐economic mobility expectations. However, faith in God was actually endorsed more strongly than meritocracy, and it was also positively associated with goal engagement and not with goal disengagement. Even if the causal factor makes reference to an external supernatural agent, it does not seem that belief in God represents purely uncontrollable causal factors. Instead, as we hypothesized, the causal factor may be seen as a form of compensatory primary control that is associated with recognising that one's personal resources, which are pushed a lot in working overseas, are not sufficient to attain the goal, and that another extraordinary resource—God's help—is needed. This result is consistent with findings in qualitative studies involving Filipino samples (Tuason, Citation2008), and may reflect a form of spiritual experience in Philippine society and in other societies with strong belief in the importance of religious beliefs (Crabtree, Citation2010). Thus, faith in God also fits the engagement‐promoting pathway, though its indirect effect is smaller than that of meritocracy. The idea seems consistent with the popular Filipino saying, “Nasa Diyos ang awa, nasa tao ang gawa” (God gives mercy to those who help themselves) and with earlier research showing that among Filipinos, hopeful thoughts regarding the role of spiritual forces in goal attainment (i.e., external‐spiritual locus‐of‐hope) tend to be associated with the belief that hard work and application lead to positive outcomes, an association not found in other Asian samples (Bernardo & Nalipay, Citation2016).

However, we wish to note that the causal belief related to faith in God may not always represent primary control strivings in all contexts. It is possible that the causal roles of faith in God could be seen as being beyond one's control. Viewed in this way, the causal role of faith in God might be understood as similar to fatalism or surrendering to the will or workings of unknown external forces. As such, belief in these factors might promote compensatory secondary control more likely to be associated with a disengagement‐oriented pathway. There is some evidence from Philippine samples that hopeful thoughts regarding the role of spiritual forces in goal attainment are negatively associated with help‐seeking intentions of Filipino women who experienced intimate partner violence (Bernardo & Estrellado, Citation2017), which is consistent with disengagement‐oriented coping even if not directly related to social mobility goals. Although our results are consistent with the assumption that causal beliefs related to faith in God relate to goal engagement, future research might inquire into other possible conceptions of this particular causal belief and their implications for social mobility expectations.

The hypothesis relating luck, disengagement, and lower SES expectations was supported by the data, but the hypothesis on social network was not. This was surprising given how this factor was suggested to be a causal factor in a study of Filipino's social mobility attributions (Clemente et al., Citation2017), and especially given that social networks are notable in the experiences of overseas Filipino workers (Hosoda, Citation2013; Jackson, Citation2011). But a recent study of Filipino migrant workers in Macau noted the negative impact of social network support on migrant workers' mental health (Mendoza, Mordeno, Latkin, & Hall, Citation2017). This finding might provide clues to why social networks were not related to goal strategies of the workers in our sample.

Although the results generally support Shane and Heckhausen's (Citation2013) model, there is an important difference that relates to the engagement‐promoting pathway's origins in the participants' current subjective social status. In the current study, the path from current SES to meritocracy was only marginally significant, and that to faith in God was not significant. Thus, the engagement‐promoting pathway does not seem to originate from the participants' current subjects social status, and does not support the model's assumption regarding status‐related goal engagement. The difference may be due to dissimilar current SES measures. In Shane and Heckhausen's, the current SES measure referred to a more directly personal reference rating (students' compared themselves to other students in their university); in our study, participants compared their family to other families in the Philippines. Future studies could inquire into whether different measures of current subjective social class (e.g., compared to families of other known overseas workers) would be better predictors of causal conceptions and strategies.

There are other limitations in the study related to its methods, which relied on a cross‐sectional design and self‐report data. Because of missing data, many factors were uncontrolled for in the analysis such as the number of years as a migrant worker, type of work, among others. The Filipino migrant workers in Macau might also have a different migrant labour experience compared to those in other countries. Future research with more diverse samples that use longitudinal research designs, and consider other possible causal conceptions of socio‐economic mobility would help in verifying the generalizability of our research findings.

Moreover, although we increased the range of factors that might represent causal conceptions of socio‐economic mobility, it is possible that there are other more important causal factors we did not assess. There are other external and less controllable factors that might be perceived causes of social mobility. Social factors such as job opportunities, government policies, and social conditions of the country were mentioned in a study on social mobility conceptions (Clemente et al., Citation2017). Similar uncontrollable social factors in the country of migrant work could be salient causal conceptions of overseas Filipino workers, particularly as this relate to policies on migrant labour (e.g., binding minimum wage, migrant quotas, etc.) that change as a result of political transitions, shifts in the country's economic well‐being, among others (Castles, Citation2004). It is possible that for migrant workers such uncontrollable factors in their country of work might relate to disengagement.

These limitations in the scope notwithstanding, our study provides another level of analysis regarding the household theory of labour migration, by presenting evidence that shows the engagement‐promoting pathways to socio‐economic mobility that originates from controllable causal conceptions of socio‐economic mobility and goal engagement strategies. Not only do our results provide further evidence for Shane and Heckhausen's (Citation2013) model of pathways to socio‐economic mobility; the evidence derives from a new population of individuals who have chosen particularly challenging approaches to improve their family's socio‐economic status. Our results also point to new causal conceptions in these pathways, suggesting a need to contextualise such models within the cultural systems of individuals and pointing to the possibility of other meaningful pathways to a seeing a better future for their families.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by a grant from the Research Development and Administration Office of the University of Macau (Project Reference No.: SRG014‐FSH13‐ABIB). We would like to acknowledge the valuable assistance of Mario R. Echano in gathering the research data.

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Adler, N. E., Epel, E. S., Castellazzo, G., & Ickovics, J. R. (2000). Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy, white women. Health Psychology, 19, 586–592. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.19.6.586

- Bernardo, A. B. I. (2013). Social dominance orientation and attitudes towards the poor: Contrasting lower and higher socioeconomic groups in the Philippines. Philippine Journal of Psychology, 46(1), 39–69.

- Bernardo, A. B. I., & Estrellado, A. F. (2017). Locus‐of‐hope and help‐seeking intentions of Filipino battered women victims of intimate partner violence. Current Psychology, 36, 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-015-9385-z

- Bernardo, A. B. I., & Nalipay, M. J. N. (2016). Social axioms as social foundations of locus‐of‐hope: A study in three Asian cultural groups. Personality and Individual Differences, 95, 110–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.02.046

- Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back‐translation for cross‐cultural research. Journal of Cross‐Cultural Psychology, 1, 185–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910457000100301

- Castles, S. (2004). The factors that make and unmake migration policies. International Migration Review, 38, 852–884. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2004.tb00222.x

- Clemente, J. A. R., Daganzo, M. A. A., Bernardo, A. B. I., & Pangan, C. A. C. (2017). Filipino adolescents' conceptions of socioeconomic mobility: A consensual qualitative research. Child Indicators Research, 10, 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-016-9370-6

- Côté, S. (2011). How social class shapes thoughts and actions in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 31, 43–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2011.09.004

- Crabtree, S. (2010). Religiosity highest in world's poorest nations. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/142727/religiosityhighest-world-poorest-nations.aspx (Accessed 13 January 2018).

- van der Ham, A. J., Ujano‐batangan, M. T., Ignacio, R., & Wolffers, I. (2014). Toward healthy migration: An exploratory study on the resilience of migrant domestic workers from the Philippines. Transcultural Psychiatry, 51(4), 545–568. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461514539028

- Heckhausen, J., Wrosch, C., & Schulz, R. (2010). A motivational theory of life‐span development. Psychological Review, 117, 32–60. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017668

- Hill, J., Jobling, R., Pollet, T., & Nettle, D. (2014). Social capital across urban neighbourhoods: A comparison of self‐report and observational data. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 8, 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0099131

- Hosoda, N. (2013). Kababayan solidarity? Filipino communities and class relations in United Arab Emirates cities. Journal of Arabian Studies, 3, 18–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/21534764.2013.802945

- International Labour Organization. (2015). ILO global estimates on migrant workers: Results and methodology. Geneva, Switzerland: ILO.

- Jackson, V. (2011). Belonging against the national odds: Globalisation, political security and Philippine migrant workers in Israel. Global Society, 25, 49–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2010.522982

- Lauby, J., & Stark, O. (1988). Individual migration as a family strategy: Young women in the Philippines. Population Studies, 42, 473–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/0032472031000143596

- Massey, D. S. (1994). An evaluation of international migration theory. Population and Development Review, 20, 699–751. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137660

- Mendoza, N. B., Mordeno, I. G., Latkin, C. A., & Hall, B. J. (2017). Evidence of the paradoxical effect of social network support: A study among Filipino domestic workers in China. Psychiatry Research, 255, 263–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.05.037

- Orbeta Jr., A. (2008). Economic impact of international migration and remittances on Philippine households: What we thought we knew, what we need to know (No. 2008–32). PIDS Discussion Paper Series.

- Philippine Statistics Authority. (2017). 2016 Survey of overseas Filipinos. Retrieved from https://psa.gov.ph/content/statistical-tables-overseas-contract-workers-ocw-2016 (Accessed 13 January 2018)

- Ravanilla, N. M., & de Pano robleza, E. J. (2005). The contribution of OFW remittances to income inequality: A decomposition analysis. Philippine Review of Economics, 42(2), 27–54.

- Reyes, M. L., & Yujuico, I. C. (2014). Psychological distress among college youth as a function of family SES: The mediating effect of sense of poverty and the mitigating role of family resources. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology, 8(02), 95–104. https://doi.org/10.1017/prp.2014.9

- Rodriguez, E. (1998). International migration and income distribution in the Philippines. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 46, 329–350. https://doi.org/10.1086/452341

- Semyonov, M., & Gorodzeisky, A. (2008). Labor migration, remittances and economic well‐being of households in the Philippines. Population Research and Policy Review, 27, 619–637. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-008-9084-7

- Shane, J., & Heckhausen, J. (2013). University students' causal conceptions about social mobility: Diverging pathways for believers in personal merit and luck. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 82, 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.08.003

- Shane, J., & Heckhausen, J. (2017). It's only a dream if you wake up: Young adults' achievement expectations, opportunities, and meritocratic beliefs. International Journal of Psychology, 52, 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12408

- Stark, O. (1984). Migration decision making: A review essay. Journal of Development Economics, 14, 251–259.

- Tacoli, C. (1996). Migrating for the sake of the family'? Gender, life course and infra‐household relations among Filipino migrants in Rome. Philippine Sociological Review, 44, 12–32.

- Tuason, M. T. G. (2008). Those who were born poor: A qualitative study of Philippine poverty. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55, 158–171. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.55.2.158

- Yang, D. (2008). International migration, remittances and household investment: Evidence from Philippine migrants' exchange rate shocks. The Economic Journal, 118(528), 591–630. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2008.02134.x