Abstract

Objective

This study investigated the relation between flow and aesthetic salience during sport, specifically whether heightened aesthetic salience interfered with flow for adolescent athletes. This study further tested whether neuroticism strengthened the relation between aesthetic salience and flow for boys and girls and whether this relation was stronger for year 9 or year 11 high school students.

Method

Data were from wave two of the Youth Activity Participation Study (YAPS) of Western Australia. The sample included 1,812 students (814 boys, 988 girls). The YAPS survey was administered using laptop computers or in pen and paper format.

Results

Results indicated a significant four‐way interaction between aesthetic salience, gender, neuroticism, and year level for experiences of flow. Probing of the four‐way interaction indicated that aesthetic salience was positively predictive of flow at lower levels of neuroticism, but negatively predictive of flow at higher levels of neuroticism, for year 11 girls. For boys, there was a conditional main effect such that more experiences of aesthetic salience predicted more flow in sport.

Conclusions

These findings illustrate that experiences of aesthetic salience in sport are complex and vary according to individual attributes.

Funding information Australian Research Council, Grant/Award Number: DP0774125, DP1095791, DP130104670

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

Sport participation provides young people with an opportunity to experience flow

Focusing on the body's aesthetics may heighten body awareness and influence the probability of flow states

Neuroticism is a personality trait that may exacerbate bodily experiences, including aesthetic salience

WHAT THIS TOPIC ADDS?

Greater aesthetic body satisfaction predicted more experiences of flow in athletes

Year 11 girls who reported higher aesthetic salience and more neuroticism experienced less flow in sport

Boys who reported higher aesthetic salience also experienced more flow in sport

INTRODUCTION

Sport participation often promotes positive views of self (Blomfield & Barber, Citation2011), physical competence (Blinde, Taub, & Han, Citation1993), and positive psychological experiences and peak motivational states including flow (Csikszentmihalyi & Rochberg‐Halton, Citation1981; Jackson, Citation2000). Flow is an optimal experience, a state that is associated with heightened performance and concentration (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1990; Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2002; Ullen et al., Citation2012). Self‐reports of flow describe a feeling of being ‘in the zone’ due to total absorption in the activity. Further, flow is an intrinsically rewarding and enjoyable experience (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1990) motivating people to return to activities in which they experience it, including sport.

Sport provides necessary elements for flow to occur including challenge‐skill balance, clear goals, and concentration on the sporting activity (Jackson, Citation2000). Further, sport provides opportunities to be in the present moment (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1990). Although sport provides opportunities for flow these opportunities may be inhibited under certain conditions. Specifically, contexts that trigger body consciousness may inhibit flow (Greenleaf, Citation2005; Jackson, Citation1992; Jackson, Citation1995; Tiggemann & Slater, Citation2001). Because flow experiences require a person to be fully absorbed in the moment (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1990), elements of sport that trigger appearance awareness may limit flow (Fredrickson & Roberts, Citation1997).

Focusing on the body's aesthetics, also called aesthetic salience, is associated with negative psychological and behavioural consequences (e.g., Fredrickson & Harrison, Citation2005; Fredrickson & Roberts, Citation1997; Greenleaf & McGreer, Citation2006; Tiggemann & Slater, Citation2001; Young, Citation1990). For example, compared to those who do not emphasise appearance, those who focus on how their body looks are less satisfied with their body (Fredrickson & Roberts, Citation1997; Greenleaf & McGreer, Citation2006), have increased body shame, and show decreases in performance on both physical (Fredrickson & Harrison, Citation2005) and cognitive tasks (Fredrickson, Roberts, Noll, Quinn, & Twenge, Citation1998; Guizzo & Cadinu, Citation2016; Quinn, Kallen, & Cathey, Citation2006). Further, focusing on how the body looks while participating in sport may undermine opportunities for flow (Jackson & Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1999). Because flow is linked with peak experiences and persistence in sport (Jackson & Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1999), examining circumstances and personal attributes that enhance or supress flow is important.

Objectification theory

A theoretical framework for examining bodily experiences in sport is Objectification Theory (Fredrickson & Roberts, Citation1997). Objectification Theory states that women's bodies are viewed and evaluated for the use and pleasure of others (Fredrickson & Roberts, Citation1997; Tylka & Hill, Citation2004), particularly men (Tiggemann & Kuring, Citation2004). When girls experience objectification they have an awareness of their physical appearance. Although most girls are, to some extent, affected by focusing on the body's aesthetics, not all experience this bodily focus negatively, or to the same degree as their peers (Donaghue, Kurz, & Whitehead, Citation2011; Tiggemann, Coutts, & Clark, Citation2014). Some girls may experience aesthetic salience as confidence enhancing, and even empowering (Carey, Donaghue, & Broderick, Citation2010; Thompson & Donaghue, Citation2014).

This study explores experiences of aesthetic salience in a large sample of adolescent athletes. Little research has explored aesthetic salience in sport and its relation to flow, and the few studies have reported different levels of strength in the link between body consciousness and flow. In some cases, focusing on the body's aesthetics had a negative impact on flow; these studies, however, only tested adult women (Fredrickson et al., Citation1998; Greenleaf, Citation2005; Szymanski & Henning, Citation2007; Tiggemann & Slater, Citation2001; Tiggemann & Williamson, Citation2012) and little is known about the relation for younger participants. Some research has found that body awareness led to habitual body monitoring, which in turn led to greater body shame and appearance anxiety, but body consciousness was not significantly related to flow (Tiggemann & Slater, Citation2001). Therefore, research on how athletes experience their body needs to be extended younger to adolescents and should consider for whom body consciousness is related to flow in sport. This study focused on individual vulnerabilities likely to accentuate awareness of appearance, and therefore to amplify effects of aesthetic salience experiences. We asked if the relation between aesthetic salience and flow differed for older and younger boys and girls, and whether personality influenced how athletes experienced their body.

Potential moderators

Gender

Body image research focuses primarily on girls’ experiences of body consciousness, with little research examining such experiences for boys. This is surprising as boys have become increasingly aware of how their body is perceived by others (e.g., Slater & Tiggemann, Citation2010; Strelan & Hargreaves, Citation2005; Tiggemann & Kuring, Citation2004). This awareness is particularly evident for boys who participate in sport, given that they are evaluated by spectators (Slater & Tiggemann, Citation2011), but the outcome of such experiences is not well understood, particularly during adolescence. This study addresses this gap by examining experiences of aesthetic salience in sport for both boys and girls.

Personality

An individual difference that may moderate the link between aesthetic salience and flow is personality. An individual's personality can influence how they think and feel about their body. Some research has explored how personality may influence bodily experiences and well‐being in adulthood. Miner‐Rubino, Twenge, and Fredrickson (Citation2002) found body consciousness was associated with neuroticism and depressive symptoms in female students. However, little is known about how neuroticism is related to aesthetic salience during the high school years, for boys and girls. Neuroticism encompasses a broad domain of negative affect, including predispositions to experience anxiety, depression, and shame (Costa Jr., Terracciano, & McCrae, Citation2001; Costa & McCrae, Citation1980). Therefore, having a neurotic personality could exacerbate aesthetic salience experiences and interfere with flow states.

Grade in school

During adolescence a young person goes through complex physiological changes (Tiggemann & Williamson, Citation2012). These changes are experienced differently for boys and girls. For girls, body dissatisfaction increases with age, with the increasing discrepancy between how they look and how they would like to look, exacerbated after pubertal development (Clay, Vignoles, & Dittmar, Citation2005). For boys, pubertal development brings them closer to the ideal male physique; thus, older boys are more satisfied than younger boys with how their body looks (Abbott & Barber, Citation2010; Cohane & Pope, Citation2001; McCabe & Ricciardelli, Citation2004). Given these developmental trends, the self‐monitoring and concern with external appearance fundamental to aesthetic salience may vary in impact during different periods of adolescence for boys and girls, especially for those higher in neuroticism.

The present study

Our primary aim was to investigate the relation between aesthetic salience and flow in sport; specifically, whether aesthetic bodily experiences interfere with flow for adolescent athletes. Because the relation between aesthetic salience and flow is likely complex, we investigated whether neuroticism strengthened the relationship between aesthetic salience and flow for boys and girls, and whether this relation was more influential for older or younger athletes. We hypothesised that aesthetic salience would hinder flow for girls; given evidence that girls are less satisfied with their body. We further expected that neuroticism would strengthen the predicted relation between aesthetic salience and flow. The expected relation for boys was less clear, so we posed a research question about whether aesthetic salience would vary in its link to flow, depending on personal attributes of male athletes. Because previous literature has shown that aesthetic satisfaction may be positively associated with flow (Szymanski & Henning, Citation2007; Tiggemann & Williamson, Citation2012), we controlled for aesthetic satisfaction.

METHOD

Participants

Data were derived from wave two of the Youth Activity Participation Study of Western Australia (YAPS‐WA). Participants included year 9 and 11 students. Of the 1,812 participants, 988 were girls (639 in year 9 and 349 in year 11) and 814 were boys (510 in year 9 and 304 in year 11). The mean age was 14-years and 6 months (SD = 1.1 years; year 9 M = 13.98, year 11 M = 15.98). Participants were from 34 high schools (19 government and 15 independent) across several districts (urban, rural and semirural) in WA. The sample comprised 82% Caucasian, 7% Asian, 1% African, 1% Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, and 0.6% Middle Eastern students. The remaining 8% were from other backgrounds or did not respond to the question. Students were included as athletes if they indicated they had participated in an organised sport outside of physical education.

Measures

Demographics

Demographic information was collected from participants, including gender and school year level. Gender was coded 0 = boys and 1 = girls. Year in school was coded 0 = year 9 and 1 = year 11.

Sport participation

Participants were provided with a list of sports and asked to indicate the organised sports, outside of school hours, in which they participated. The most popular sports for girls were netball, athletics, and soccer and for boys were Australian Football League (AFL), soccer, and cricket. The self‐selected sport in which they spent the most hours per week was the context for which participants addressed aesthetic salience and flow questions.

Aesthetic salience

Three items were used to assess aesthetic salience in sport. These items were modelled on the Youth Experience Survey (YES 2.0; Larson, Hansen, & Moneta, Citation2006) and were written to capture aesthetic salience. Participants reported whether they had the following experiences in their sport, ‘I have been encouraged to make sure that my body looks attractive’, ‘people have said things about how my body looks’, and ‘I have worried about how good my body looks’. Responses were rated on a 4‐point scale (1 = not at all; 2 = a little; 3 = quite a bit; 4 = yes, definitely) and had adequate reliability (α = .81).

Flow

Experiences of flow were assessed using four items (1 = never to 7 = always). A higher score indicated more frequent flow experiences in sport. Flow items were developed by Tiggemann and Slater (Citation2001) to operationalise Csikszentmihalyi's (Citation1990) description of optimal experiences, questions included ‘I become so involved in this sport that I lose track of time’, ‘during this activity I feel so involved that nothing else seems to matter’, ‘during this activity I have a very high level of concentration’, and ‘I concentrate so intensely that I can't think about anything else’ (α = .90).

Neuroticism

Ten items were used to measure neuroticism, made up of three facets: anxiety, self‐consciousness, and vulnerability. Items were derived from the NEO Personality Inventory (Costa & McCrae, Citation1992), with small adjustments to ease student comprehension. Specifically, ‘It doesn't embarrass me too much if people tease me’ was changed to ‘it doesn't embarrass me too much if people ridicule and tease me’, ‘sometimes I have been so ashamed I just wanted to hide’ was changed to ‘at times I have been so ashamed I just wanted to hide’, and ‘I feel comfortable in the presence of my teachers or other authorities’ was changed to ‘I feel comfortable in the presence of my bosses or other authorities’. Items were assessed with a 5‐point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree; α = .71).

Aesthetic satisfaction

This construct was measured with three items, and has been found to be both reliable and valid. Each item was rated from 1 = not at all; to 4 = yes, definitely. An example item was, ‘I am very happy with the appearance of my body’ (α = .91).

Procedure

Parent and student consent were required to participate. The YAPS survey was administered by researchers using laptop computers, or pen and paper format. The survey took approximately 30–40-min to complete during school time. Participants were entered into a prize draw as compensation for their time.

RESULTS

Bivariate correlations

Bivariate analyses were conducted separately by gender. Correlations and descriptive statistics are presented in Table . For girls, significant positive relations were found between aesthetic satisfaction and flow, as well as between aesthetic salience and neuroticism. As expected, significant negative associations were found between aesthetic salience and aesthetic satisfaction, and between neuroticism and aesthetic satisfaction. No other correlations were statistically significant for girls. For boys, significant positive correlations were found between aesthetic salience and flow and aesthetic satisfaction and flow, and significant negative relations were found between aesthetic satisfaction and neuroticism, and between school year level and neuroticism.

Table 1. Correlations and descriptive statistics (N = 1, 812)

Prior to hierarchical multiple regression the relevant assumptions were tested. A sample size of 1,812 was deemed adequate given five independent variables in the analysis (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2007). Tests of normality suggested that the aesthetic salience and flow scales were skewed. Given our large sample size, and the limited gains to be made, data were not transformed (Games, Citation1983).

Moderation analyses

Aesthetic satisfaction was entered at step one of the regression, as a covariate predicting flow. Aesthetic salience, neuroticism, gender, and year level were then entered at step two, followed by two‐way, three‐way, and four‐way interaction terms. Table shows coefficients and R‐squared statistics for all steps of the model.

Table 2. Hierarchical regression predicting experiences of flow in sport (N = 1, 812)

Aesthetic satisfaction accounted for significant variance in flow experiences. Greater aesthetic satisfaction predicted more experiences of flow. The second step accounted for significant additional variance in flow, with significant main effects of aesthetic salience and gender, such that boys, and students experiencing more aesthetic salience in sport, reported more flow experiences.

Steps three and four did not significantly predict flow. In the fifth step the four‐way interaction term contributed a small but significant amount of variance explained. Follow‐up analyses examined the three‐way interaction between aesthetic salience x neuroticism x year level separately for boy and girls.

Aesthetic salience, neuroticism, and year level predicting flow for boys and girls

Probing the interaction separately for boys and girls, aesthetic satisfaction was entered in step one. The predictor variables were entered in step two, followed by the two‐way interaction terms (aesthetic salience × neuroticism, aesthetic salience × year level, neuroticism × year level) and finally the three‐way interaction term (aesthetic salience × neuroticism × year level).

Boys

For boys, aesthetic satisfaction significantly predicted flow (Table ). Specifically, boys reporting more aesthetic satisfaction also experienced more flow. Aesthetic salience, neuroticism, and year level accounted for a significant increase in variance accounted for, such that greater aesthetic salience predicted more flow, and higher neuroticism predicted less flow. Year level was not significant. No two‐way or three‐way interactions were significant.

Table 3. Regression analyses predicting boys’ experiences of flow in sport (N = 814)

Girls

Aesthetic satisfaction accounted for a significant proportion of variance in flow experiences (Table ). Greater aesthetic satisfaction in sport predicted more flow. There were no significant main effects or two‐way interactions for aesthetic salience, neuroticism, and year level. The three‐way interaction (aesthetic salience × neuroticism × year level) was a significant predictor of flow. We tested the two‐way interaction (aesthetic salience × neuroticism) separately for year 9 and year 11 girls. The two‐way interaction was significant for year 11 girls F(1, 176), 4.04, p = .04, but not significant for year 9 girls F(1, 318), 1.23, p = .27. Thus, results for year 11 girls were further tested through plotting using Modprob (Hayes & Matthes, Citation2009).

Table 4. Regression analyses predicting girls’ experiences of flow in sport (N = 988)

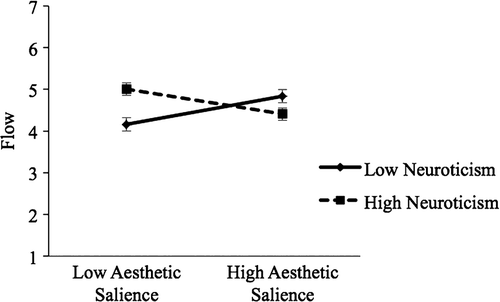

Year 11 girls

The significant interaction of aesthetic salience × neuroticism was further plotted for year 11 girls (Figure 1). Figure 1 shows the regression of aesthetic salience predicting flow, at both low and high levels of neuroticism (cut points one standard deviation above and below the mean were used as recommended; Aiken & West, Citation1991). Analyses of the simple slopes indicated that the relationship between aesthetic salience and flow varied, depending on the level of neuroticism. Specifically, year 11 girls higher in neuroticism reported less flow when aesthetic salience was higher, whereas the girls lower in neuroticism manifested the reverse.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to investigate the roles of aesthetic salience, gender, neuroticism, and year level in flow experiences reported by young athletes. We proposed that aesthetic salience is a bodily experience that can be triggered in sport participation. Research generally states that experiences of aesthetic salience are negative and undesirable (e.g., Fredrickson & Harrison, Citation2005; Fredrickson & Roberts, Citation1997; Greenleaf & McGreer, Citation2006; Tiggemann & Slater, Citation2001). We suggested, however, that this might not always be the case, and that aesthetic salience might vary in its link to flow, depending on personal attributes of adolescent athletes. Thus, this study explored differential vulnerability to effects of a bodily focus by asking whether the impact of aesthetic salience might vary depending on a combination of gender, neuroticism and year level.

Girls’ experiences of aesthetic salience

Surprisingly, we found a positive relationship between aesthetic salience and flow for girls low on neuroticism, such that the less neurotic year 11 girls who experienced more aesthetic salience in sport also experienced more flow. This novel finding is in contrast to previous research showing aesthetic salience was detrimental to flow (e.g., Jackson & Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1999). Perhaps girls lower in neuroticism find aesthetic experiences less disruptive than their more neurotic peers. We also note in our bivariate results that girls who scored lower on neuroticism reported more aesthetic satisfaction. Positive aesthetic self‐views may make a focus on appearance, during sport rewarding and perhaps even facilitative of flow when neuroticism is low. This potential facilitation of flow may depend on the sport context. In this sample, the most popular sports for girls were team‐based sports that are not primarily focused on appearance (e.g., netball and soccer). Future research could explore team‐based versus individual sports, or compare sports that differ in appearance focus.

Girls higher in neuroticism did not show the same pattern as girls lower in neuroticism, reporting less flow with more aesthetic salience. This finding supports previous evidence that neuroticism may exacerbate body awareness, which may interfere with positive psychological states, such as flow (Fredrickson & Roberts, Citation1997; Jackson, Kimiecik, Ford, & Marsh, Citation1998). Neuroticism is accompanied by anxiety and worry, which have been consistently associated with heightened body consciousness experiences (Miner‐Rubino et al., Citation2002), and prevention and disruption of flow (Jackson et al., Citation1998). Therefore, more neurotic athletes who also experience high levels of body consciousness may have more difficulty attaining the necessary dimensions of flow, including sense of control, enjoyment, and loss of self‐consciousness.

Further, as girls who score high in neuroticism develop, they may be particularly responsive to socio‐cultural expectations of how the female body is expected to look, eliciting body consciousness (Canals, Vigil‐Colet, Chico, & Martí‐Henneberg, Citation2004). Over time, comments about one's body and how it looks during sport may accentuate female athletes’ body consciousness, perhaps with negative impact for girls higher in neuroticism. Body awareness while practicing sport may also be heightened in older girls because as girls get older they report experiencing their body as more of a “public domain” for others to observe and evaluate (Fredrickson & Roberts, Citation1997). The negative outcome of feeling that people are observing the body is further exacerbated for those individuals who have a neurotic personality. Therefore, neuroticism may be particularly detrimental as girls get older, exacerbating aesthetic bodily experiences and limiting the opportunity for flow to occur.

Boys’ experiences of aesthetic salience

Contrary to findings for girls (e.g., Slater & Tiggemann, Citation2010), boys had a significant positive relation between aesthetic salience and flow. This novel finding demonstrates that aesthetic salience experiences do not have universally negative effects. Focusing on how their body looks may confirm to boys that their appearance is free of perceived flaws and matches the thin or muscular ideal. Indeed, aesthetic salience experiences may be empowering for some boys (Ferron, Narring, Cauderay, & Michuad, Citation1999), for whom focusing on how their body looks is a positive experience that may enhance flow in sport. This result needs to be interpreted in light of the fact that our aesthetic satisfaction measure is valence free. For example, one item asks whether people have commented on how your body looks while you are playing sport. Perhaps boys are more likely than girls to receive positive comments about appearing strong and muscular, creating a positive experience. Therefore, aesthetic bodily experiences may differ by gender, being more positive and self‐enhancing for boys, but less so for girls.

Results also indicated a conditional main effect of neuroticism on flow, whereby boys higher in neuroticism experienced less flow in sport. There are several factors that may underlie this association between neuroticism and flow for boys. To experience flow, one must enjoy the sport and be completely absorbed in the activity. Because salient features of neuroticism are emotional (Eid & Diener, Citation1999) and cognitive (Flehmig, Steinborn, Langner, Scholz, & Westhoff, Citation2007) instability, such fluctuations in mood could interrupt both cognitive and emotional aspects of flow, causing an increased risk for attention lapses and thus inhibiting flow. Therefore, it seems that neuroticism may directly interfere with the enjoyment component of flow, hindering the likelihood of flow in sport.

Limitations

The present study needs to be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, the design was cross‐sectional; thus causal conclusions may not be drawn. For example, it is not possible to determine if aesthetic salience experiences lead to changes in flow or if a decrease in flow results in changes in aesthetic salience experiences. Longitudinal studies are needed to ascertain whether individual attributes of young athletes have a long‐term impact on flow experiences.

Second, the self‐reported aesthetic salience measure is focused on a range of experiences related to appearance—including what other people say or encourage, as well participants’ focus on appearance. The measure is therefore tapping into external and internal scrutiny. The data for the current study were also retrospective, as the respondents were instructed to consider their sport participation in the recent past. Retrospective data can be problematic, particularly for flow research. Flow is experiential in nature and flow theorists have argued that the best way to assess flow is to collect data immediately following the activity or by interrupting the activity (Csikszentmihalyi & Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1992).

Further, the small effect sizes need to be acknowledged, as they potentially limit the implications of this research. We suggest that one might expect truncated ranges for the constructs that limit flow in sport among those who voluntarily participate in sport. In other words, those who are most neurotic (De Moor, Beem, Stubbe, Boomsma, & De Geus, Citation2006) and body conscious (Slater & Tiggemann, Citation2011) may choose to avoid sport. Therefore, because our participants are all athletes, there may be a more restricted range in aesthetic views than if our sample also included non‐athletes. Despite the limited variance accounted for, the four‐way interaction still significantly adds to the original model, and these small effects can accumulate into consequential outcomes at a population level.

IMPLICATIONS

If aesthetic salience disrupts flow for girls higher in neuroticism, one practical application would be to modify the sport context to reduce potential for body consciousness. Further, to ensure positive experiences in sport it is particularly important to encourage girls to value, appreciate, and respect their body while participating in sport. Doing so could enhance body appreciation and allow adolescents to value their body more in terms of functionality (Abbott & Barber, Citation2010). Due to the important physiological and psychological benefits sports have to offer, it is important that national and international campaigns continue to encourage girls to participate in sport (e.g., the Sports England This Girl Can campaign and Queensland Government's Start Playing, Stay Playing). Our study makes a unique contribution to existing literature on bodily experiences in sport and is the first study to consider how gender, personality and year level moderate the link between aesthetic salience and flow for young athletes. Unique combinations of personal attributes and predispositions can lead to different experiences for young people. Understanding both boys’ and girls’ experiences of aesthetic salience is important, as health professionals hope to keep youth engaged in sport through adolescence.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Youth Activity Participation Study of Western Australia has been funded by grants under Australian Research Council's Discovery Projects funding scheme: DP0774125 and DP1095791 to Bonnie Barber and Jacquelynne Eccles, and DP130104670 to Bonnie Barber, Kathryn Modecki, and Jacquelynne Eccles. Bree Abbott provided invaluable input on the conceptual framing for this article. We would like to thank the high school principals, their staff, and the students who participated in the YAPS‐WA study. We would also like to thank Gabriel Heaslip, Bree Abbott, Catherine Drane, Corey Blomfield Neira, Kira McCabe, Lynette Vernon, and Stuart Watson for their contributions to data collection and management.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

Funding information Australian Research Council, Grant/Award Number: DP0774125, DP1095791, DP130104670

REFERENCES

- Abbott, B. D., & Barber, B. L. (2010). Embodied image: Gender differences in functional and aesthetic body image among Australian adolescents. Body Image, 7(1), 22–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.10.004

- Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. London, England: SAGE.

- Blinde, E. M., Taub, D. D., & Han, L. (1993). Sport participation and women's personal empowerment: Experiences of the college athlete. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 17(1), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/019372359301700107

- Blomfield, C. J., & Barber, B. (2011). Developmental experiences during extracurricular activities and Australian adolescents’ self‐concept: Particularly important for disadvantaged youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 582–594. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9563-0

- Canals, J., Vigil‐colet, A., Chico, E., & Martí‐henneberg, C. (2004). Personality changes during adolescence: The role of gender and pubertal development. Personality and Individual Differences, 39(1), 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.12.012

- Carey, R., Donaghue, N., & Broderick, P. (2010). What you look like is such a big factor: Girls’ own reflections about the appearance culture in an all‐girls’ school. Feminism & Psychology, 21(3), 299–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353510369893

- Clay, D., Vignoles, V. L., & Dittmar, H. (2005). Body image and self‐esteem among adolescent girls: Testing the influence of sociocultural factors. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 15(4), 451–477. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2005.00107.x

- Cohane, G. H., & Pope, H. G. (2001). Body image in boys: A review of the literature. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 29(4), 373–379. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.1033

- Costa, P. T., Jr., Terracciano, A., & Mccrae, R. R. (2001). Gender differences in personality traits across cultures: Robust and surprising findings. Journal of Personality and Social Sciences, 81(2), 322–331. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.2.322

- Costa, P. T., & Mccrae, R. R. (1980). Influence of extraversion and neuroticism on subjective well‐being: Happy and unhappy people. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38, 668–678.

- Costa, P. T., & Mccrae, R. R. (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI‐R) and NEO Five‐Factor Inventory (NEO‐FFI): Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Csikszentmihalyi, I. S. (1992). Optimal experience: Psychological studies of flow in consciousness. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Rochberg‐halton, E. (1981). The meaning of things: Domestic symbols and the self. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- De moor, M. H., Beem, A. L., Stubbe, J. H., Boomsma, D. I., & De geus, E. J. (2006). Regular exercise. Anxiety, depression and personality: A population‐based study. Preventative Medicine, 42(4), 273–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.12.002

- Donaghue, N., Kurz, T. R., & Whitehead, K. (2011). Spinning the pole: A discursive analysis of the websites of recreational pole dancing studios. Feminism & Psychology, 21(4), 443–457.

- Eid, M., & Diener, E. (1999). Intraindividual variability in affect: Reliability, validity, and personality correlated. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology., 76(4), 662–676. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.76.4.662

- Ferron, C., Narring, F., Cauderay, M., & Michuad, P. A. (1999). Sport activity in adolescence: Associations with health perceptions and experimental behaviours. Health Education Research, 14(2), 225–233. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/14.2.225

- Flehmig, H. C., Steinborn, M., Langner, R., Scholz, A., & Westhoff, K. (2007). Assessing intraindividual variability in sustained attention: Reliability, relation to speed and accuracy, and practice effects. Psychology Science, 49(2), 132–149.

- Fredrickson, B. L., & Harrison, K. (2005). Throwing like a girl: Self‐objectification predicts adolescent girls’ motor performance. Journal of Sport & Social Issues, 29(1), 79–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723504269878

- Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. (1997). Objectification theory: Towards understanding women's lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

- Fredrickson, B. L., Roberts, T. A., Noll, S. M., Quinn, D. M., & Twenge, J. M. (1998). That swimsuit becomes you: Sex differences in self‐objectification, restrained eating, and math performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 269–284.

- Games, P. A. (1983). Curvilinear transformations of the dependent variable. Psychological Bulletin, 93(2), 382–387. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.93.2.382

- Greenleaf, C. (2005). Self‐objectification among physically active women. Sex Roles, 52(1/2), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-1193-8

- Greenleaf, C., & Mcgreer, R. (2006). Disordered eating attitudes and self‐objectification among physically active and sedentary female college students. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 140(3), 187–198. https://doi.org/10.3200/JRLP.140.3.187-198

- Guizzo, F., & Cadinu, M. (2016). Effects of objectifying gaze on female cognitive performance: The role of flow experience and internalization of beauty ideals. British Journal of Psychology, 56, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12170

- Hayes, A. F., & Matthes, J. (2009). Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behavior Research Methods, 41(3), 924–936. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.3.924

- Jackson, S. A. (1992). Athletes in flow: A qualitative investigation of flow states in elite figure skaters. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 4(2), 161–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413209208406459

- Jackson, S. A. (1995). Factors influencing the occurrence of flow state in elite athletes. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 7, 138–166.

- Jackson, S. A. (2000). Joy, fun, and flow state in sport. In Y. L. Hanin (Ed.), Emotions in sport (pp. 135–155). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Jackson, S. A., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1999). Flow in sports: The keys to optimal experiences and performances. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Jackson, S. A., Kimiecik, J. C., Ford, S. K., & Marsh, H. W. (1998). Psychological correlates of flow in sport. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 20, 358–378.

- Larson, R. W., Hansen, D. M., & Moneta, G. (2006). Differing profiles of developmental experiences across types of organized youth activities. Developmental Psychology, 42(5), 849–863. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.849

- Mccabe, M., & Ricciardelli, L. (2004). A longitudinal study of pubertal timing and extreme body change behaviors among adolescent boys and girls. Adolescence, 39(153), 145–166.

- Miner‐rubino, K., Twenge, J. M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2002). Trait self‐objectification in women: Affective and personality correlates. Journal of Research in Personality, 36(2), 147–172. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.2001.2343

- Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2002). The concept of flow. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 89–105). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Quinn, D. M., Kallen, R. W., & Cathey, C. (2006). Body on my mind: The lingering effect of state self‐objectification. Sex Roles, 55(11–12), 869–974. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9140-x

- Slater, A., & Tiggemann, M. (2010). Body image and disordered eating in adolescent girls and boys: A test of objectification theory. Sex Roles, 63(1–2), 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9794-2

- Slater, A., & Tiggemann, M. (2011). Gender differences in adolescent sport participation, teasing, self‐objectification and body image concerns. Journal of Adolescence, 34(3), 455–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.06.007

- Strelan, P., & Hargreaves, D. (2005). Reasons for exercise and body esteem: Men's responses to self‐objectification. Sex Roles, 53(7/8), 495–503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-7137-5

- Szymanski, D. M., & Henning, S. L. (2007). The role of self‐objectification in women's depression: A test of objectification theory. Sex Roles, 56(1–2), 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9147-3

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). New York: Allyn and Bacon.

- Thompson, L., & Donaghue, N. (2014). The confidence trick: Competing constructions of confidence and self‐esteem in young Australian women's discussions of the sexualisation of culture. Women's Studies International Forum, 47, 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2014.07.007

- Tiggemann, M., Coutts, E., & Clark, L. (2014). Belly dance as an embodying activity?: A test of embodiment model of positive body image. Sex Roles, 71, 197–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0408-2

- Tiggemann, M., & Kuring, J. K. (2004). The role of body objectification in disordered eating and depressed mood. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43(3), 299–311. https://doi.org/10.1348/0144665031752925

- Tiggemann, M., & Slater, A. (2001). A test of objectification theory in former dancers and non‐dancers. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 25(1), 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-6402.00007

- Tiggemann, M., & Williamson, S. (2012). The effect of exercise on body satisfaction and self‐esteem as a function of gender and age. Sex Roles, 43(1/2), 119–127. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007095830095

- Tylka, T. L., & Hill, M. S. (2004). Objectification theory as it relates to disordered eating among college women. Sex Roles, 51(11–12), 719–730. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-004-0721-2

- Ullen, F., de Manzano, O., Almeida, R., Magnusson, P., Pederson, N. L., Nakamura, J., … Madison, G. (2012). Proneness for psychological flow in everyday life: Associations with personality and intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(2), 167–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.003

- Young, I. M. (1990). Throwing like a girl. Bloomington, IN: Indiana Press.