Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to establish the nature of health practitioner (HP) motivations that are associated with the practitioner who chooses and stays in work in a very remote Indigenous (VRI) community for more than 3 years. The maldistribution of HPs across Australia and the high costs associated with their low retention rates in VRI communities underpinned the study. Little work had been conducted on the HP's intrinsic motivations relating to this workplace. The power of job‐based incentives to attract and hold practitioners in remote and very remote areas has received some attention. It was hypothesised that the practitioner who chooses VRI community work will provide some motivation ratings very specific to that decision, which will be useful in predicting substantial total length of stay.

Method

A total of 547 HPs from four levels of remoteness in Australia responded to a HP's motivation survey. Using principal component analysis, motivation components were identified. Using binary logistic regression, likelihoods were estimated, linking motivations with VRI community work retention.

Results

Eight of 14 subscales developed were sensitive to VRI work experience. These formed the Very Remote Health Practitioner Motivation subscale set. Four of these motivation subscale scores together provided a significant estimate of likelihood of a practitioner having a total of more than 3 years' VRI community work experience, compared with no such experience.

Conclusions

The aims of the study were achieved by identifying the eight subscale set and the retention predictive model. Their potential value, limitations of the study, and future research possibilities are discussed.

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

Poor selection and retention of health practitioners (HPs) in very remote Indigenous (VRI) communities are very costly.

Little is known of the intrinsic motivations behind HP choice of VRI work.

No motivation measuring methods specific to HP VRI choice exist.

WHAT THIS TOPIC ADDS?

Fourteen HP work motivation scales including eight sensitive to VRI community work choice were developed.

A likelihood estimator for the HP staying in VRI work for longer than 3 years in total was developed.

There are opportunities for further pure and applied research to confirm, further validate, and refine the scales.

INTRODUCTION

This article documents the development of a set of health practitioner's work motivations subscales, which explore the nature and influence of health practitioner (HP) work motivations, particularly as they relate to recruitment and retention to very remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (hereafter termed Indigenous) communities. These communities are predominantly populated by Indigenous peoples and serviced by usually non‐Indigenous HPs (medical, nursing, and allied health) who are resident or visit for widely varying periods. They usually work in a small team setting, including local Indigenous HPs. The considerable money, time, service quality, and related costs associated with recruitment and poor retention of these HPs in this setting provided the rationale for the study (e.g., Russell, McGrail, Humphreys, & Wakerman, Citation2011; Wakerman, Sparrow, Thomas, Humphreys, & Jones, Citation2017). The enduring apocryphal assertion that to choose and stay in the very remote Indigenous (VRI) community workplace, the practitioner is likely to be a “Missionary, Mercenary, or Misfit”—that is, motivated by zealotry, greed or an inability to fit in anywhere else (Stirrat, Citation2008)—provided early stimulus for the study, but was not expected to provide a relevant contemporary model of motivation.

There is a growing body of work concerning the recruiting and retaining of well‐suited medical practitioners to “rural and remote” areas (Eley, Young, & Przybeck, Citation2009; Eley, Young, & Shrapnel, Citation2008; Humphreys, McGrail, Joyce, Scott, & Kalb, Citation2012). However, both recruiting and retaining medical, nursing, and allied health professions specifically to very remote areas have received little specific attention (Campbell, McAllister, & Eley, Citation2012). The main focus has been on employer controlled workplace incentives likely to motivate the HP to seek rural or remote work, such as monetary or related “mercenary” incentives. These relate to extrinsic motivations, using Herzberg's (Citation1968) distinction between such motivations and intrinsic motivations. The latter involve rewarding internal experiences from work, such as good feelings of accomplishment (e.g., Deci & Ryan, Citation1991) and contributing to the common good (de Botton, Citation2015). Intrinsic motivations are influenced by beliefs, values, and related felt needs and wants (Cooper, Citation2012; Herzberg, Citation1968; Vroom, Citation1964).

There is little evidence concerning the most prevalent intrinsic motivations, which influence the practitioner to seek and stay for a substantial total time (e.g., more than 3 years) in VRI communities, where need is great and access to services limited (Campbell et al., Citation2012). Such intrinsic influences might include compassion, need for sense of purpose, social justice values (Perry, Citation1996), drive to serve the underserved (Grobler et al., Citation2009), and desire to learn intercultural skills.

Locke and Latham (Citation2004) proposed that motivation constitutes “…internal factors that impel action and …external factors that can act as inducements to action. The three aspects of action that motivation can affect are direction (choice), intensity (effort), and duration (persistence)” (p. 388). Their model relates well to this study. The first‐time VRI practitioner must be impelled to action by the belief that the VRI job may suit; then induced to consider the very remote opportunity, often with little information about the actual current working situation. To be recruited, the VRI opportunity must be researched, sought out, and accepted, all usually at a large distance from the workplace and usually without meeting future workplace colleagues. Then, to be retained in a very remote job for a substantial time (i.e., more than 3 years), the practitioner's work motivations must influence effort and persistence to stay in what can be a demanding, and socially and professionally isolated situation (Lenthall et al., Citation2009).

There has been no instrument available that is specifically tailored to assessing the work motivations relevant to the VRI or any other non‐urban work setting. The underlying construct of work motivation in the new scale was conceptualised as the behaviour‐energising influences that arise from within the practitioner, being goal focussed, expectancy driven, and readily changeable. Such motivations do not constitute personality traits but will reflect them. They were proposed to influence the direction, effort, and persistence in the seek/stay/go sequence of choosing to work in any job (Locke & Latham, Citation2004). This is a synthesis of various motivation descriptors found in the literature, which Wright described as “vast…numerous and diverse…” (Citation2001, p. 576).

METHOD

The study was carried out in three stages. First, the Health Practitioner Motivations Survey (HPMS) was constructed and administered to develop the motivation scales, using cross‐sectional surveying. Second, motivation subscale development was carried out from survey data using standard scale development practice (e.g., Pallant, Citation2010). This was expected to provide a set of subscales which, when taken together, would comprise the Health Practitioner Motivations Scale, with each subscale representing one work‐related motivation. Third, after controlling for a number of variables, the power of the motivation subscale scores to indicate likelihood of choice of and substantial total length of retention in the VRI community workplace was identified. This was consistent with the central goal of this study.

Participants

A total of 547 HPs (allied health, medical, and nursing) were surveyed across all levels of remoteness in Australia (sampling details below). Participation was voluntary, responses were anonymous, and submitting the completed survey was accepted as informed consent for the survey responses to be used in the project. A small cash donation was committed for every completed survey received, to the one of several health bodies chosen by each responder. Ethics approval was obtained from the Flinders University Social and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee, the Central Australian Health Research Ethics Committee, and the Aboriginal Health Research Ethics Committee of South Australia.

The Accessibility/Remoteness Index Australia (ARIA+) classification system was used throughout this study (GISCA, Citation2011; Lees & White, Citation2009). This system comprises five grades of remoteness: Major Cities; Inner Regional; Outer Regional; Remote; and Very Remote. The Inner and Outer regional data were merged into one grade, “Regional,” for this study. Respondents were provided with a map of Australia showing colour coded ARIA+ zones, with which to calculate their total duration of work experience in each zone.

Procedures and data collection

Developing the HPMS

First, a test plan was developed, which listed the domains and subdomains, or themes, of work‐related motivation that were expected to both share the underlying construct and scope the expected needs of the scale. These domains were deduced from the literature review and experienced practitioner input, as described below. They provided the domain themes from which the individual items were identified. The essential needs based framework of autonomy, competence, and relatedness, relating to developing self‐determination, was used in shaping this plan (Deci & Ryan, Citation1991).

Many items were derived from the free‐access Internet‐based International Personality Item Pool (IPIP) (Goldberg et al., Citation2006). Many of these items link behavioural tendencies with needs and wants, such as those relating to altruistic, compassionate, risk taking, and adventure seeking preferences. The IPIP items were used as the basis from which items were shaped to be contextually relevant to the health professionals participating in the study. Examples of these modified items are listed in Table .

Table 1. Examples of HPMS final items and their IPIP derivatives

Several subdomain themes were identified in the public service motivation work, including compassion, social justice, and self‐sacrifice (Coursey, Perry, Brudney, & Littlepage, Citation2008; Perry, Citation1996). Items were tailored to “tap” (DeVellis, Citation2003) such themes while also capturing national potentially motivating policies such as Closing the Gap (Lenthall et al., Citation2011) in the remote and very remote public service environment.

Over 120 motivation‐specific items were generated from the identified domains. The target number for the final HPMS was 100 motivation‐related items, consistent with DeVellis's (Citation2003) recommendation of commencing with approximately four times the number of items expected to suit the end‐product scale, in this case for VRI community applications. A total of 25–30 items were expected to optimise both the scope and user friendliness of the scale's subscales.

Item design was kept positive and simple, with 6‐point rating scale from 1 (very unlike me) to 6 (very like me) with no midway neutral point. Item content was aimed to span practitioner motivations across all levels of remoteness.

In the process of drafting the HPMS, review was obtained by a scale development specialist and a panel of 12 HPs of at least 10 years' minimum relevant health practice experience, including urban, remote, and very remote experience. The refined draft HPMS was further assessed by several specialist senior HPs across all remoteness levels and several experts in surveying health matters. In all, more than 50 practitioner and survey experts were consulted.

Sampling

The HPMS was first made available to HPs in Internet‐based form across all levels of remoteness in Australia, over 5 months in 2013/2014, using purposive sampling strategies. A national database of very remote facilities was used; the less remote facilities were accessed via publicly accessible Internet‐based sources. Members of professional associations were also accessed via five health professional peak bodies, several state and local Medicare network bodies; several Aboriginal health services in the Northern Territory (NT), Western Australia (WA), and South Australia (SA); several rural medical training groups (WA, SA, NT); and urban, remote, and very remote health provider networks in every state. HPs were also accessed at continuing professional development events in hospital and community‐based regional, remote, and very remote workplaces. Response rates were around 50% for the latter approach. All hardcopy data collected were transferred to the Survey Monkey platform, from which they were exported to SPSS Version 20.

Analysing the data

The approximately 45,000 useable responses obtained were subjected to principal component analyses (PCA), following guidance by DeVellis (Citation2012), Pallant (Citation2011), and Tabachnick and Fidell (Citation2013), to produce the subscales that could together comprise the Health Practitioners' Motivation Scale. Only components with three or more items loading above .4 were retained in the final analysis. Once an item was retained, it was not used again. Items were considered for deletion when their communalities were below .3 and their mean inter‐item correlations were exceptionally high (>.8) or low (<.2). Each component was corroborated with the use of the exploratory factor analysis method of principal axis factoring, as recommended by Pallant (Citation2011) and DeVellis (Citation2012). The internal reliability of each subscale was assessed using Cronbach's α and inter‐item correlation means. The latter indicator is recommended (e.g., Pallant, Citation2011), because adequately reliable scales of less than 10 items often fail to produce a Cronbach's α above .7, the usual minimum accepted for adequate internal reliability.

To initially appraise the subscales' construct validities, Spearman's ρ correlations were obtained between each subscale and three relevant variables: the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale, the Person‐Job Fit Scale, and the Job Satisfaction scale. These three variables were chosen on both practical and evidence‐based grounds. The Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (Schaufeli, Bakker, & Salanova, Citation2006) measures high motivation related variables, such as work‐related enthusiasm, energy, commitment, and sense of achievement. Some authors (e.g., Mbindyo, Blaauw, Gilson, & English, Citation2009) effectively equate these measures with motivation per se. Choice of the fit variables was based on evidence (e.g., Bright, Citation2007, 2008) that work motivation and sense of fit with job tasks and the employer's values and principals are strongly associated. Job satisfaction (Warr, Citation1990) was chosen on the evidence‐based expectation that work motivation and work satisfaction is significantly positively correlated (e.g., Blegen, Citation1993).

Each subscale's criterion validity, or how well it predicts choice of and total duration of work in the VRI community setting, was reflected in its ability to estimate likelihood of a practitioner having had nil or long term experience in the remote and very remote workplace. This was estimated in Stage 3 of the study.

Predicting very remote workplace choice and retention

The likelihoods of each motivation having influence over total retention in VRI community work were calculated using the SPSS Version 20 binary logistic regression program. The potentially confounding influence of various personal and professional practitioner variables, such as gender, age and profession, was controlled for.

RESULTS

The HPMS

The final HPMS comprised 101 work motivation items and 39 profession related, validity appraising and demographic questions. It gathered total length of stay in each workplace by remoteness, using ARIA+ zoning. Piloting had revealed no indication of social desirability bias, so that “fake‐check” items were considered unnecessary.

The distribution of participants' workplace remoteness at the time of response is summarised in Table . Twenty‐five of the 547 respondents worked over two different zones, explaining the total of 572.

Table 2. HPMS respondent distribution by remoteness of workplace

Frequencies of key demographic variables are listed in Table . The sample was weighted towards the Australian born, non‐Indigenous, middle‐aged female practitioner, with partner, and offspring who have left both school and home.

Table 3. HPMS frequencies of variables of interest

The motivation subscales

The PCA of the HPMS data produced 17 components that potentially constituted useful HP work motivation subscales, using the method described above. Each was named to reflect its evident underlying construct. Table lists these components along with their constituent items and each item's component loading, presented in decreasing order of loading magnitude for each component. Each loading provides a measure of the correlation of its item with the component it is affiliated with.

Table 4. The 17‐health practitioner work motivation subscales: Their constituent items and component loadings

None of these components were very close to normally distributed, which was expected in such human variables (Pallant, Citation2010). Accordingly non‐parametric statistics were used to explore their properties.

Subscale internal reliabilities

Of the 17 components, referred to as subscales from here, 14 were of at least adequate internal reliability, based on Pallant's (Citation2011) guidelines, with Cronbach's α ≥ .65 and/or their inter‐item correlation ≥.35. The three remaining subscales—Variety Seeker, Career Builder, and Managerial Self Confidence—were suspended due to their low internal reliability ratings, as listed at the bottom of Table .

Table 5. The 17‐new health practitioner work motivation subscales: Internal reliabilities

Early validity appraisals

Spearman's ρ correlations between each of the 14 retained subscales and the 3 validity related variables of interest were obtained. Five subscales correlated significantly (p < .05) with all three variables of interest concerning validity: Primary Health Care (PHC) Orientation; Compassion; Clinical Competence Seeking; Intercultural Interest; and Challenge Seeking. Three of these subscales correlated at >0.3 with the Utrecht Engagement scale, while none correlated above 0.17 with Job Satisfaction, and 0.18 with Job Fit.

Five subscales significantly correlated (p < .05) with two of the three variables of interest, with all again involving Work Engagement. These were Belonging Needs; Personal Demand Preferences; Living Location Preferences; Avoidance Needs; and Clinical Self‐Containment. Four of these subscales also correlated significantly with Job Satisfaction, while only one, Belonging Needs, correlated with Workplace Fit (0.15; p < .002).

Despite their very probable roles in motivating job choice, the four remaining subscales—Lifestyle Preferences, Financial Incentives, Relationship Imperatives, and Spiritual Beliefs—did not correlate significantly with any of the three variables of interest (see Discussion for implications).

The 14 subscale motivations were matched against the responses to the open HPMS question: “Please record … your main motivation(s) for seeking Very Remote work before your first such work experience.” Of 313 responses, 291 (93.0%) were closely aligned with at least one subscale in the 14 subscale set. The remaining 7% of responses were of non‐specific themes such as “It was part of my job” and “For experience.” Hence, it is concluded that the 14 subscale set well reflects actual work motivations associated with VRI work experience. The implications of both high and low scores for each retained subscale are described in Table .

Table 6. The 14‐health practitioner work motivation subscales: Likely high and low score meanings

Motivations sensitive to VRI community work

Using binary logistic regression (see Table ), eight of the 14 motivations indicated significant likelihood of more than 3 years' total retention in VRI community work.

Table 7. Logistic regression summary: Each of 14 subscales with the dependent variable VRI 3-years+/no VRI community work experience

After controlling for the potentially confounding variables of age, gender, partner status, and parental status, motivations Compassion and Personal Demand Preferences were eliminated. However, taking into account the effect size by four VRI Workplace variables (VRI and VR Work Experience, VRI Work Satisfaction, and self‐appraised Probability of Seeking VRI Work), on each of the 14 motivations, the following eight motivations were selected to constitute the Very Remote Health Practitioners' Motivation (VRHPM) subscale set:

Living Location Preferences;

Clinical Self‐containment;

Intercultural Interests;

Challenge Seeker;

Personal Demand Preferences;

Clinical Competence;

Relationship Imperatives;

Lifestyle Preferences.

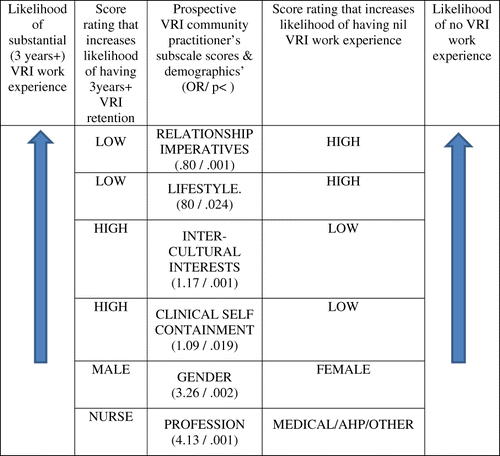

This eight subscale, 33‐item set differentiated between those prospective practitioners who were and were not likely to stay in VRI community work for a substantial total time. Further binary logistic regression (see Table ) identified the best predictive combination of motivations and other practitioner variables for predicting more than a total 3 years' VRI community work, as compared with nil such work, as follows:

Relationship Imperatives;

Intercultural Interests;

Clinical Self‐containment;

Lifestyle Preferences;

Gender;

Profession.

Table 8. Logistic regression summary: Subscales and practitioners' personal variables

Both Relationship Imperatives and Lifestyle Preferences estimated that the likelihood of belonging to the VRI 3 years + group would reduce by a factor of .80 for every unit increase in the total score of each subscale. The subscales Intercultural Interests and Clinical Self‐containment (reverse scored) estimated that the likelihood of belonging to the VRI 3 years + group, rather than the No VRI group, would increase by 1.17 and 1.09, respectively, for every unit of total score increase in each subscale. The respondent being male increased the likelihood by 3.26 times that he would have VRI 3 years + community experience. Being a nurse quadrupled this likelihood. The six factor model correctly classified 83.0% of respondents into those with VRI 3 years + total work experience compared with those with no such experience.

DISCUSSION

Both recruitment and subsequent retention of health professionals to very remote locations are major national workforce issues. This study described a set of 14 HP work motivations, along with their measuring scales, potentially relevant to his matter. Eight of these motivations were associated with practitioner retention in the VRI community for more than a total of 3 years, as compared with nil such work experience. Four of these eight subscales, along with gender and profession, together provided a global indication of likelihood of a practitioner choosing and staying in the VRI community workplace for longer than 3 years in total (see the Ready Reckoner at Figure 1). In producing these measures, the study has resulted in new knowledge and has developed a tool that could enhance both the recruitment to and retention of HPs in the Australian very remote health system.

In the less than VR work environment, work motivations are usually highly centred on the expected and actual demands and rewards of the job per se. Motivations concerning after‐hours possibilities tend to be met independently of the workplace. In contrast, in the majority of VR jobs and especially the VRI live‐in‐community job, the practitioner enters into a job‐lifestyle total package. This usually involves the “24/7” demands of living and working in the VRI community, with limited physical and human resources to meet the many and frequent demands (Lenthall et al., Citation2009), thus drawing heavily on the personal resources of the practitioner. Both the prospective VRI practitioner's work and lifestyle motivations will therefore be very influential in the decision to work there. Accordingly, they could be time efficiently assessed in the recruitment stage, using relevant subscales. Motivations will need to be resilient, as will the applicant overall, since familiar support networks and convenient opportunities to de‐brief and de‐role, cannot be assumed in the VRI community work setting. Such opportunities are taken for granted in major cities, regional and even remote, but not very remote, workplaces.

The absence of a motivation related purely to continuing professional education (CPE) was unexpected. An examination of the items distribution showed that, rather than all clustering into one component, CPE‐related items appeared in several subscales. These included Clinical Competence, Career Management, and Financial Interests. This absence of a distinct CPE component/subscale reflected the mixed findings in the literature review relating to the strength of CPE in motivating practitioners to remain in very remote work environments (e.g., Humphreys et al., Citation2007).

The results strongly supported at least 10 of the 14 subscales as adequately valid. However, it is very likely that the four which did not correlate significantly with the validity measures—Financial Interests, Lifestyle Preferences, and Relationship Imperatives—do play significant extrinsic motivating roles in choice of work of most categories. Their low correlations with the chosen validity measures suggest the need for review of the latter in terms of their scope as major validity guides in future work.

The apocryphal “3 Ms” were represented by several of the 14 subscales. Spiritual Beliefs reflected “Missionary”‐based motivations to a moderate extent; Financial Interests reflected “Mercenary”‐based motivations to a moderate extent; and Avoidance Needs and Belonging Needs provided measures clearly relevant to “Misfit” (i.e., searching for better sense of fit) motivations. None of these four motivations indicated strong influence on the likelihood of VRI 3 years + retention. Spiritual Beliefs was mildly more associated with non‐VRI work choice. It is therefore likely that the 3Ms, despite Stirrat's (Citation2008) claim that they still strongly resonate with the very remote aid industry, do not play a significant role in contemporary very remote health work choice.

Methodological issues

There are a number of methodological issues, including limitations of the study, that warrant specific comment. First, one of the strengths of the study was the use of the ARIA+ remoteness classification, thus avoiding the shortcomings of the majority of “rural and remote” studies in which lack of distinction between very remote, remote and rural workplaces severely limits the strength of their conclusions with regard to key very remote recruitment and retention issues.

The Ready Reckoner predictive model (Figure 1) is underpinned by the odds ratios (ORs) estimated for each of the four subscales involved. The majority of significant ORs produced for the subscales appear relatively small, ranging from .75 to 1.30. However, the likelihood of a respondent belonging to the VRI 3 years + group changes by a multiple of the OR figure for every unit increase in score of the scale measure (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2013). For example, for a practitioner scoring the maximum of 30 on Intercultural interests (score range 5–30, with 26 score points inclusive) likelihood that this respondent will belong to the VRI 3 years + group is 1.1726 or 59.3 times greater than that of belonging to the No VRI group, controlling for other factors.

Scale construct validity includes several subclasses of validity, including “known groups” and convergent and discriminant validity (Pallant, Citation2010). It is assessed progressively as research evidence builds. By assessing the significance of differences between each VR variable's two “known groups” (e.g., very remote and non‐very remote practitioners), support for the subscales' construct validities concerning VR practitioner motivations can be added to the existing evidence, which comprises the strong links between the subscale scores and some or all of the three benchmark variables which relate to work motivations: Job Engagement, Job Satisfaction, and Person‐job Fit. The correlations between 10 of the 14 retained subscales and these three variables are supportive of their construct validities. It is especially notable that the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale content is both the most likely to be sensitive to work motivations based on face validity, and is the most strongly related of the three variables with 10 of the 14 subscales. Of the 14 subscales, 13 responded with at least one significant difference between the known groups on at least one VR‐related variable. Four subscales were significantly influenced by three of four VR variables; eight of the 14 subscales registered significant influence by the VR Work Satisfaction variable; and seven subscales were significantly influenced by the VRI community work experience variable. These findings provide additional evidence for the construct validity of 13 of the 14 subscales.

In summary, the results provided important validating evidence for the majority of the 14 subscales, and no evidence that would warrant rejecting any one subscale on the basis of inadequate validity.

There were several study limitations or potential limitations, including sample representativeness, brevity of subscales, and the possibility of “faking.” The sample surveyed was broad in both health profession and remoteness categories. Due to the unquantifiable number of practitioners who may have accessed the HPMS on the Internet via professional associations, but chose not to respond, it was not possible to calculate the overall response rate provided. Hence it was difficult to assess the degree to which the motivations identified were truly representative of the entire populations accessed.

The subscales produced are all brief, at eight items or less, and the impact of this on their internal reliability was accounted for. However, it should be noted that these subscales would usually not be used or researched alone but in various sets (e.g., in Figure 1), depending on the intended task. This means that the composite scale comprising the chosen subscales will be substantially larger in item number than any single subscale.

As noted above, all surveys and scales are potentially prone to image management or “faking” of answers, aimed at providing a more socially acceptable response than the genuine one. No evidence emerged that this presented a problem in this study, possibly because all respondents were aware that their answers were anonymous. Where a respondent is both not anonymous and seeking a certain outcome, such as selection for a job, faking could become an issue.

Future research and possible applications

The future research invited by this work can be considered in three categories. The first involves further exploration of the subscales with reference to validity and structure. Confirmatory factor analysis with new samples should be involved. Special attention needs to be focussed on those four subscales (Financial Interests, Lifestyle Preferences, Relationship Imperatives, and Spiritual Beliefs), which did not correlate significantly with the three validity benchmarks. It would be useful to compare the influence of the motivation of Financial Interests across the three health professional categories (medical, nursing, allied heath) with regard to choice and retention in the VRI community workplace.

Second, it will be fruitful to explore various subset combinations of the 14 subscales to further establish their potential applications in human resource management. This would include the longitudinal testing of the in‐field predictive power of the Ready Reckoner (Figure 1), and other likelihood estimators of various important workplace variables, to predict choice and retention with regard to specific workplaces of interest. The potential of the VRHPM set in continuing professional development, staff counselling, related problem solving, and devising VRI community job advertisements also needs testing.

Third, the matter of possible “faking” needs attention where the subscales are being used in non‐anonymous potential‐gain situations such as job applications. This could involve the comparing of response patterns of those with and without obvious outcome preferences, using any of several fake check scales alongside the motivations scales, to assess faking tendencies (Paulhus & Reid, Citation1991).

Such research findings could assist in personnel selection, new appointee orientation, professional development, and staff counselling, all aimed to foster better recruitment and retention of the very remote health workforce. It is not proposed that a prospective practitioner would be selected or rejected based purely on their motivation subscale scores. In the recruitment process, adaptive motivations can be aligned with job realities by providing appropriate motivational information. The scales provide a way of measuring both current motivations and changes in them.

CONCLUSION

Addressing the high disease burden of and optimising access to health services by remote Indigenous Australians is a national priority. One of the persistent major barriers to improved health outcomes relates to workforce maldistribution and subsequent poor access. This study has generated important new knowledge that can be applied through the utilisation of the set of eight subscales, which relates specifically to the VRI workplace and the retention prospect Ready Reckoner to enhance the recruitment process and to maximise retention of the remote health workforce.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Scholarship funding was provided for the first 3 years of the study by the Centre for Remote Health, which is funded by the Australian Government Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training Program.

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Blegen, M. A. (1993). Nurses job satisfaction: A meta‐analysis of related variables. Nursing Research, 42(1), 36–41. https://doi.org/10.1097/0000.6199‐199301000‐00007

- Bright, L. (2007). Does person‐organization fit mediate the relationship between public service motivation and the job performance of public employees? Review of Public Personnel Administration, 27(4), 361–379. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X07307149

- Bright, L. (2008). Does public service motivation really make a difference on the job satisfaction and turnover intentions of public employees? The American Review of Public Administration, 38(2), 149–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074008317248

- Campbell, N., Mcallister, L., & Eley, D. S. (2012). The influence of motivation in recruitment and retention of rural and remote allied health professionals: A literature review. Rural and Remote Health, 12, 1900.

- Cooper, M. (2012). The intrinsic foundations of extrinsic motivations and goals: Towards a unified humanistic theory of well‐being and change. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 53(2), 153–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167812453368

- Coursey, D. H., Perry, J. L., Brudney, J. L., & Littlepage, L. (2008). Psychometric verification of Perry's public service motivation instrument. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 28(1), 79.

- de Botton, A. (2015). Opinion: Connected to the good: Exploring the sources of motivation at work [Podcast]. Sydney, Australia: Religion and Ethics RN ABC Radio.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1991). A motivational approach to self: Integration in personality. Paper presented at the Nebraska symposium on motivation: Vol. 38 (pp. 237–288). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

- Devellis, R. (Ed.). (2003). Scale development: Theory and applications (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Devellis, R. (2012). Scale development: Theory and applications (Vol. 1, 3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Eley, D. S., Young, L., & Przybeck, T. R. (2009). Exploring the temperament and character traits of rural and urban doctors. The Journal of Rural Health, 25(1), 43–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.2009.00197.x

- Eley, D. S., Young, L., & Shrapnel, M. (2008). Rural temperament and character: A new perspective on retention of rural doctors. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 16, 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1584.2007.00946

- GISCA. (2011). Accessibility index of Australia (ARIA) review: Analysis of areas of concern. Adelaide, Australia: University of Adelaide.

- Goldberg, L. R., Johnson, J. A., Eber, H. W., Hogan, R., Ashton, M. C., Cloninger, C. R., & Gough, H. G. (2006). The international personality item pool and the future of public‐domain personality measures. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(1), 84–96. Retrieved from. http://www.elsevier.com/locate/jrep

- Grobler, L., Marais, B. J., Mabunda, S. A., Marindi, P. N., Reuter, H., & Volmink, J. (2009). Intervention for increasing the proportion of health professionals practising in rural and other underserved areas [Review]. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 6–13. Retrieved from. http://www.thecochranelibrary.com

- Herzberg, F. (1968). One more time: How do you motivate employees. Harvard Business Review, 46, 53–62.

- Humphreys, J. S., Mcgrail, M. R., Joyce, C. M., Scott, A., & Kalb, G. (2012). Who should receive recruitment and retention incentives? Improved targeting of rural doctors using medical workforce data. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 20(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1584.2011.01252.x

- Humphreys, J. S., Wakerman, J., Wells, R., Kuipers, P., Jones, J., Entwistle, P., & Harvey, P. (2007). Improving primary health care workforce retention in small rural and remote communities: How important is ongoing education and training. Canberra, Australia: Australian Primary Health Care Research Institute.

- Lees, J., & White, C. (2009). Taking a GRIP of ASGC‐RA: A peek at GPRIP and ASGC‐RA. Brisbane, Australia: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing.

- Lenthall, S., Wakerman, J., Opie, T., Dollard, M., Dunn, S., Knight, S., & Watson, C. (2009). What stresses remote area nurses? Current knowledge and future action. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 17(4), 208–213.

- Lenthall, S., Wakerman, J., Opie, T., Dunn, S., Macleod, M., Dollard, M., & Knight, S. (2011). Nursing workforce in very remote Australia, characteristics and key issues. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 19(1), 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1584.2010.01174.x

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2004). What should we do about motivation theory? Six recommendations for the twenty‐first century. The Academy of Management Review, 29(3), 388–403. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20159050

- Mbindyo, P. M., Blaauw, D., Gilson, L., & English, M. (2009). Developing a tool to measure health worker motivation in district hospitals in Kenya. Human Resources for Health, 7(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478‐4491‐7‐40

- Pallant, J. (2010). Scale development survival manual ACSPRI course manuals – How to manual (). Melbourne, Australia: ACSPRI.

- Pallant, J. (2011). SPSS survival manual (4th ed.). Sydney, Australia: Allen and Unwin.

- Paulhus, D. L., & Reid, D. B. (1991). Enhancement and denial in socially desirable responding. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(2), 307–317.

- Perry, J. L. (1996). Measuring public service motivation: An assessment of construct reliability and validity. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 6(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjounals.jpart.a024303

- Russell, D. J., Mcgrail, M. R., Humphreys, J. S., & Wakerman, J. (2011). What factors contribute most to the retention of general practitioners in rural and remote areas? Australian Journal of Primary Health, 18(4), 289–294. https://doi.org/10.1071/PY11049

- Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire a cross‐national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164405282471

- Stirrat, R. L. (2008). Mercenaries, missionaries and misfits: Representations of development personnel. Critique of Anthropology, 28(4), 406–425. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308275X08098259

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using mutlivariate statistics (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

- Vroom, V. H. (1964). Work and motivation. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

- Wakerman, J., Sparrow, L., Thomas, S. L., Humphreys, J., & Jones, M. (2017). Equitable resourcing of primary health care in remote commmunities in Australia's Northern Territory: A pilot study. BMC Family Practice, 18, 75.

- Warr, P. (1990). The measurement of well‐being and other aspects of mental health. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(3), 193–210.

- Wright, B. E. (2001). Public‐sector work motivation: A review of the current literature and a revised conceptual model. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 11(4), 559–586. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjounals.jpart.a003515