Abstract

Objective

To determine the perceived met and unmet need for clinical neuropsychological assessment (CNA) in headspace youth mental health services Australia wide.

Method

Brief online survey of headspace service providers exploring the number and types of clients seen, confidence in identifying neurocognitive impairments, and need, availability and usefulness of CNA. A total of 532 salaried, private, and in‐kind service providers working across 103 primary headspace and headspace Youth Early Psychosis Programs completed the survey from May to December 2017.

Results

Survey respondents were 76% female with a mean age of 38 (range 22–74-years). The majority had psychology (42%) or social work (21%) backgrounds. CNA was believed to be beneficial for 35% of headspace clients on average, but 86% of service providers reported that CNA was unavailable. Only 12% of clients were estimated to have received CNA when it was needed. On average, 36% of headspace clients were estimated to present with neurocognitive impairment and 38% were described as diagnostically complex (e.g., comorbid medical, developmental, substance use, trauma presentations). A mean of 27% were described as having a suspected or diagnosed developmental condition (e.g., intellectual disability, learning disorder, autism spectrum disorder, attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder). Respondents rated their confidence in identifying cognitive impairment as moderate.

Conclusions

There is marked unmet need for CNA to provide diagnostic clarification and inform treatment approaches in youth mental health care. Funding for CNA under the Medicare Benefits Schedule, headspace workforce development in neurocognitive screening and cognitive interventions, and tele‐neuropsychological services should be explored.

Funding information National Health and Medical Research Council, Grant/Award Number: APP1051891; University of Melbourne, Grant/Award Number: Ronald Philip Griffiths Fellowship

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Clinical neuropsychological assessment (CNA) is an important component of holistic mental health care.

CNA is not routinely available in youth public mental health services or through the Medical Benefits Schedule.

headspace is Australia's federally funded primary care service that provides early intervention and support for young people with mental health concerns. The perceived need for CNA among primary care clinicians in this service has not been examined.

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS

According to a national survey of youth mental health service providers, respondents reported CNA would benefit a third of their clients but only 12% can access this service.

headspace service providers report that over one‐third of their clients have neurocognitive or developmental difficulties.

There is a significant gap in neuropsychology service provision in youth mental health services. Funding of CNA, workforce training in neurocognitive screening and interventions, and tele‐neuropsychology options are urgently needed to meet this service gap.

INTRODUCTION

Holistic and timely assessment has been identified as an important and potentially cost‐effective attribute of youth mental health services (Hamilton et al., Citation2017a). Neurocognitive and symptom assessment specifically, is internationally recognised as important to youth mental health care (Hamilton et al., Citation2017b). CNA is the most comprehensive and reliable means to assessing neurocognitive functioning in individuals (Braun et al., Citation2011; Lezak, Howieson, & Loring, Citation2004; Meyer et al., Citation2001; Roebuck‐Spencer et al., Citation2017). In young people, in addition to comprehensively assessing neurocognitive domains, CNA often includes academic achievement and behaviour testing, to diagnose neurodevelopmental disorders and help understand current school functioning, tertiary study, and employment capacity. CNA yields rich information, including: (a) describing the presence and nature of neurocognitive impairments and strengths; (b) confirming, refuting, or modifying diagnoses; (c) identifying the treatment needs and guiding therapeutic approaches; and (d) monitoring the treatment effects and changes in functioning over time (Allott et al., Citation2013; American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology, Citation2007; Fisher, Hetrick, Merrett, Parrish, & Allott, Citation2017; Meyer et al., Citation2001; Proffitt, Brewer, Parrish, McGorry, & Allott, Citation2018). To facilitate clinical practice and client outcomes, a written report and verbal feedback is standard practice (Allott, Brewer, McGorry, & Proffitt, Citation2011; American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology, Citation2007; Gorske & Smith, Citation2009).

In their Review of Mental Health Programs and Services, Australia's National Mental Health Commission identified a specific gap in clinical neuropsychology service provision. Accordingly, they recommended that CNA be included in the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) as part of the Better Access to Mental Health Care initiative (National Mental Health Commission, Citation2014). Currently, however, CNA is not routinely available in public mental health services (Fisher et al., Citation2017), nor through the MBS. The frequency and uptake of private referrals for young people with mental ill health is unknown, but suspected to be low given the high cost of private CNA (College of Clinical Neuropsychologists, Citation2012; MSAC, Citation2015), minimal reimbursement through private health insurance, and possible lack of qualified providers.

headspace was established in 2006 and is Australia's federally‐funded primary care service that provides early intervention and integrated support to people aged 12–25-years with mental health concerns (McGorry et al., Citation2007; Rickwood, Telford, Parker, Tanti, & McGorry, Citation2014). The headspace Youth Early Psychosis Programs (hYEPP) were established in 2014 and offer specialist early intervention to 12–25-year‐olds experiencing or identified as being at risk of psychosis (Hetrick et al., Citation2017). The headspace model involves an engagement and assessment session with an intake worker to determine the person's presenting concerns and needs. The young person is then referred to the appropriate service provider/clinician for treatment. Published data reveal the main presenting concerns and services provided within headspace (Rickwood et al., Citation2014; Rickwood et al., Citation2015), but there are currently no empirical data on the perceived need by clinicians for CNA in youth presenting for mental health care in Australia. The aim of this study was to address this gap and determine the met and unmet need for CNA in headspace Australia wide.

METHODS

Participants and procedure

All operational primary headspace (N = 101) and hYEPP (N = 6) centres were invited to participate. Eligible participants were salaried, private, or in‐kind service providers of any professional background who assessed or treated young people attending headspace or hYEPP. Administrative staff were excluded.

A two‐step recruitment process was undertaken. First, each headspace manager was contacted by telephone; the study was explained and an invitation made to include their centre. Upon agreement, headspace managers were asked to indicate how many staff would be sent the survey, to estimate response rates. Eligible staff were then invited to participate via an email from their headspace manager, which included the study Plain Language Statement and link to the online survey. The survey was open at each centre for a minimum of 4 weeks. Staff were sent a reminder email at the end of week 1 and 3 to further encourage participation. Given the large number of centres, the survey was rolled out in waves of approximately 10 headspace centres every few weeks. The survey was conducted from May to December 2017. Ethics approval was obtained from the Centre for Youth Mental Health—Human Ethics Advisory Group (The University of Melbourne) and Alfred Health Ethics Committee. The survey was managed using the Qualtrics online platform. This research conformed to standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Online survey

A brief, cross‐sectional, anonymous online survey was developed to gain an understanding of the needs for CNA within headspace. The survey was piloted by a group of experts and refined following feedback. A brief definition of CNA was provided prior to the survey questions, to ensure respondents had sufficient baseline knowledge to complete the survey. Ten questions asked about the number and types of clients seen, confidence in identifying neurocognitive impairments, and need, availability and usefulness of CNA. Workplace, demographic, and professional background information were also captured.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS 22.0 and Microsoft Excel. Preliminary data screening identified missing or extreme survey responses, which were excluded or corrected where possible using predetermined criteria. Most (99.5%) item responses fell within z = ±4.00 of the mean, which is considered acceptable in a large sample (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, Citation2010). Descriptive analysis was conducted, including a breakdown of responses per state/territory. In addition, data from primary headspace and hYEPP responders were summarised and compared using Mann–Whitney U tests; note that only a proportion of respondents answered the question asking whether they were from primary headspace, hYEPP or both as this question was only added some time after the study had commenced.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

Every headspace manager agreed to have their centre included in the study. Survey responses were received from 103 (96.3%) centres. Based on manager reports, it was estimated that 1,687 headspace staff were sent the survey link. The survey was commenced by 792 individuals; however, 260 incomplete cases were removed. The final sample comprised 532 survey responders, corresponding to a completer response rate of 31.5%. The median survey completion time was 8 min.

Table shows the sample demographic and employment characteristics. The majority of survey respondents were female, with postgraduate qualifications, and with a psychology or social work background. Approximately 8% of survey completers were medical professionals. A broad range in age and years working in mental health and with young people was represented.

Table 1. Demographic and employment characteristics of survey responders (N = 532)

Client presentations and need for CNA

As shown in Table , at a national level, survey responders estimated contact with approximately 24 unique clients per month. Over one‐third of young people were estimated to present with neurocognitive impairment (e.g., problems with concentration, learning, memory, problem solving, language) (M = 35.8%, SD = 23.6), or were described as diagnostically complex (e.g., diagnosis unclear due to medical, developmental, substance use, trauma, or other complications) (M = 37.5%; SD = 25.3). Around one‐quarter of clients (M = 26.9%, SD = 19.1) were described as having a suspected or diagnosed developmental difficulty (e.g., intellectual disability, learning disorder, language disorder, autism spectrum disorder, attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and other developmental condition). Service providers reported moderate confidence in their ability to detect neurocognitive impairment (M = 5.6, SD = 2.0; estimated on a 10‐point scale, with 10 being most confident).

Table 2. Reporting of client presentations and need for clinical neuropsychological assessment in headspace at a national and state/territory level

Respondents estimated that over a third (M = 34.5%, SD 25.0) of headspace clients would benefit from CNA. On average, however, 85.9% (range: 81–100%) of service providers reported that CNA was not available. The proportion of clients who had actually received CNA when it was needed was low (M = 12.2%, SD = 21.3). Of the service providers reporting that CNA was available to their clients (n = 75), 44 (8.3% of total sample) reported free accessibility and 30 (5.6% of total sample) could only access CNA for a fee.

Findings were broadly consistent between states and territories (Table ). However, notable differences were that providers in Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) tended to report lower rates of clients presenting with neurocognitive impairment or developmental difficulties, whereas estimates were higher in South Australia. Reported confidence in detecting neurocognitive difficulties was somewhat higher in Northern Territory and lower in Tasmania. Percentage of clients estimated to benefit from CNA was somewhat lower in Tasmania and the ACT, consistent with the finding of lowered estimated rates of clients presenting with neurocognitive impairments in these states.

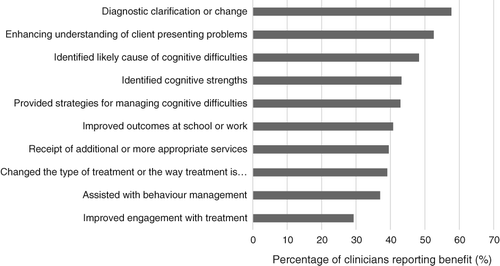

Benefits of CNA

The reported benefits for young people who accessed CNA at a national level are displayed in Figure 1. When examining the data at a state/territory level, similar to national estimates, diagnostic clarification or change, an enhanced understanding of the presenting problems and identification of the likely causes of neurocognitive difficulty were identified as the three greatest benefits of CNA across the state/territories. Of the 307 people who indicated that diagnostic clarification or change was a key benefit, the specific diagnostic outcomes were: confirmed diagnosis (n = 192, 62.5%), identified clinically significant neurocognitive impairment (n = 152, 49.5%), made a new diagnosis (n = 147; 47.9%), and ruled out a diagnosis (n = 112, 36.5%).

Subgroup analysis comparing headspace primary and hYEPP responders

Comparisons between responders from headspace primary (n = 269) and hYEPP (n = 35) were undertaken. Respondents who did not specify either headspace primary or hYEPP (n = 218), or were involved in both programs (n = 10), were excluded from this analysis. hYEPP staff reportedly worked significantly more hours per week (M = 38.4, SD = 14.1) than headspace primary staff (M = 27.5, SD = 12.4; p < .001). Despite working more hours, hYEPP staff reported seeing significantly fewer unique clients per month compared with headspace primary staff (M = 15.6, SD = 13.5 vs. M = 26.0, SD = 19.4, respectively, p < .001). No other demographic differences were observed. Table shows that service providers from hYEPP reported a significantly greater proportion of young people presenting with neurocognitive impairment and being more likely to benefit from CNA compared with headspace primary service providers.

Table 3. Reported client presentations and need for clinical neuropsychological assessment by headspace primary or hYEPP only (n = 304) service providers7

DISCUSSION

The key finding from this national survey is that service providers report that over a third of youth presenting to headspace would benefit from CNA; however, over 85% of surveyed clinicians indicated that CNA is unavailable within their service. Respondents estimated that only around 1 in 10 young people who needed CNA had one completed. This highlights a substantial gap in service for headspace clients, which may also extend to youth attending primary and secondary mental health care (e.g., child and adolescent/youth mental health services) in Australia more generally (e.g., Fisher et al., Citation2017). This marked gap in service provision suggests that a large subgroup of young people seeking mental health care do not receive holistic and timely assessment of their presenting concerns, which increases the risk of inappropriate or inadequate treatment. We argue that this gap in service is a missed early intervention opportunity, given that headspace has reached to youth Australia wide.

Service providers estimated that over one‐third of their young clients are experiencing neurocognitive impairment or are diagnostically complex, and over a quarter are coming with confirmed or suspected developmental difficulties. However, these service providers had only moderate confidence in their ability to identify cognitive impairments themselves. The large minority of young people reportedly experiencing neurocognitive impairment is unsurprising as neurocognitive impairment is recognised as a core symptom of mental illness (McGorry et al., Citation2014). Comprehensive meta‐analyses demonstrate significant impairments in attention, information processing, learning, memory, and executive function early in the course of psychosis (Hauser et al., Citation2017; Mesholam‐Gately, Giuliano, Faraone, Goff, & Seidman, Citation2009), bipolar disorder (Lee et al., Citation2014), eating disorders (Zakzanis, Campbell, & Polsinelli, Citation2010), and depression (Goodall et al., Citation2018; Lee, Hermens, Porter, & Redoblado‐Hodge, Citation2012). Impairments are also present in young people seeking help for mental ill health who do not meet full threshold for a mental disorder (Fusar‐Poli et al., Citation2012; Hermens et al., Citation2013; Lee et al., Citation2015). Indeed, the average neurocognitive performance of Australians aged 18–30 presenting for treatment is significantly lower than their healthy peers (Hermens et al., Citation2013).

Neurocognitive impairments in psychosis tend to be larger than in other mental health conditions, so it was not surprising that responders from the headspace early psychosis services reported a higher frequency of neurocognitive difficulties in their clients relative to primary headspace responders (50 vs. 33%, respectively). Furthermore, hYEPP responders reported working more hours but seeing fewer unique clients per month than headspace primary clinicians, suggesting that they may spend more time with their clients. Thus, hYEPP clinicians may have greater opportunities for deeper knowledge of their clients, including being able to gauge neurocognitive function and observe potential impairments. A recent international survey of youth mental health practitioners found that neuropsychological assessment was believed to be relatively more important for psychosis than other disorders (Hamilton et al., Citation2017b). Taken together, there is strong alignment between previous objective and the current subjective findings, indicating that the assessment and management of neurocognitive impairments is an essential component of early intervention for mental ill health.

Neurocognitive impairment is also a core and stable symptom of pervasive neurodevelopmental disorders that emerge in childhood, including intellectual disability, communication disorders, autism spectrum disorder, attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and specific learning disorders (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Previous research has shown that neurodevelopmental disorders are more common in youth with mental illness than the general population (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013; Khandaker, Stochl, Zammit, Lewis, & Jones, Citation2014; King, Citation2016) and headspace service providers affirmed that neurodevelopmental difficulties were over‐represented in their clients. Neurodevelopmental disorders pose increased challenges to diagnosis and providing effective mental health treatment (Allott et al., Citation2011; King, Citation2016). Indeed, survey responders from the present study reported that when it was accessed, the greatest benefits of CNA were diagnostic clarification, enhancing understanding of the presenting problems, and identifying the likely cause of neurocognitive difficulties in their clients.

Previous research demonstrates a strong association between neurocognitive impairments and poorer productivity in school, work and independent living in youth and adults with mental illness (Allott et al., Citation2013; Bowie et al., Citation2010; Lee et al., Citation2013; Lee et al., Citation2015). Almost 30% of young adults attending headspace are disengaged from study or work (O'Dea et al., Citation2014; Rickwood et al., Citation2014). Unless recognised early and appropriately treated, neurocognitive impairments and pre‐existing neurodevelopmental conditions reduce the efficacy of mental health treatment (Braun et al., Citation2011), inhibiting the chances of full functional recovery. The ultimate consequence is reduced productivity and creation of ongoing significant economic burden (Gore et al., Citation2011). Respondents from the present study reported that improvements in school and work were a common outcome of CNA.

While the reasons for lack of access to CNA need further exploration, a number of factors are likely, including availability/access, cost, and knowledge (Temple, Carvalho, & Tremont, Citation2006). National registration data indicate that 650 psychologists are registered with endorsement in clinical neuropsychology, but almost half (46.6%) are based in Victoria, a quarter are in New South Wales (24.8%), and 15.7% are in Queensland. This leaves only 12.9% of neuropsychologists registered in the remaining five states/territories, despite 24.8% of headspace centres being located in these regions. Discussions with managers during this survey indicated that only one neuropsychologist was employed part‐time within headspace Australia wide. This neuropsychologist was a salaried staff member of a Melbourne‐based hYEPP.

It is also possible that knowledge of CNA, including why and how to access it, may be variable among service providers, with psychology trained health professionals potentially having greater knowledge than other professions (Temple et al., Citation2006). The cost of private CNA (College of Clinical Neuropsychologists, Citation2012; MSAC, Citation2015) may also be prohibitive for many young people attending headspace.

There are several avenues for increasing access to CNA within headspace. The most obvious is direct funding of CNA, either locally or federally via the MBS, aligned with the National Mental Health Commission recommendations (National Mental Health Commission, Citation2014). Even with increased access via Medicare, workforce distribution means that neuropsychologists are not easily accessible by many headspace centres. Alternative modes of access, such as tele‐neuropsychology should be explored, with demonstrated feasibility in psychiatric populations (Brearly et al., Citation2017). A pilot study involving 11 young people (aged 14–27) with early psychosis in rural NSW found that CNA via videoconferencing was feasible, acceptable, and reliable in comparison with face‐to‐face assessment (Stain et al., Citation2011). Tele‐neuropsychology provides a promising alternative for rural and remote headspace clients to access clinical expertise that may not be readily available locally. Our findings also suggest that headspace workforce training in screening for and providing interventions for neurocognitive impairment may be beneficial.

A limitation of the present study is that respondents were self‐selecting and results may not be representative of headspace service providers generally, although the professional breakdown of this sample is broadly consistent with a previous report (Rickwood et al., Citation2015). While the response rate was low (31.5%), this rate is comparable to similar studies (Cunningham et al., Citation2015; Sellars, Detering, & Silvester, Citation2015). Furthermore, not all headspace clients attend for mental health reasons, which were not explored in the survey. Referrers' only moderate confidence in identifying neurocognitive difficulties may affect the accuracy of their estimated rates of neurocognitive and developmental difficulties among their clients. Finally, our survey did not ask about knowledge of CNA. Previous research has shown that knowledge may vary depending on professional background and previous exposure to CNA, which may influence the perceived need for CNA (Temple et al., Citation2006). For example, it is possible that given psychologists were the largest health profession represented among the survey respondents, the findings may have been positively biased towards a greater perceived need for CNA.

In conclusion, service providers report neurocognitive impairment, developmental difficulties, and diagnostic complexity in over a third of young people attending headspace, and accordingly, report that CNA would be beneficial for diagnostic clarification and treatment planning. However, over 85% of service providers do not have access to specialist CNA, with only 12% of clients in need receiving the service. This demonstrates a substantial gap in service delivery. Potential solutions include direct funding of CNA, workforce development, and tele‐neuropsychology.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research team wish to acknowledge headspace national and the contributing headspace managers and clinicians for supporting the conduct of this research. K.A. is supported by a Ronald Philip Griffiths Fellowship from the Faculty of Medicine Dentistry and Health Sciences, The University of Melbourne. E.K. receives funding from NHMRC (APP1051891) and the Faculty of Medicine at The University of Melbourne.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

Funding information National Health and Medical Research Council, Grant/Award Number: APP1051891; University of Melbourne, Grant/Award Number: Ronald Philip Griffiths Fellowship

REFERENCES

- Allott, K., Brewer, W., Mcgorry, P. D., & Proffitt, T. M. (2011). Referrers' perceived utility and outcomes of clinical neuropsychological assessment in an adolescent and young adult public mental health service. Australian Psychologist, 46, 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9544.2010.00002.x

- Allott, K., Cotton, S. M., Chinnery, G. L., Baksheev, G. N., Massey, J., Sun, P., … Killackey, E. (2013). The relative contribution of neurocognition and social cognition to 6‐month vocational outcomes following Individual Placement and Support in first‐episode psychosis. Schizophrenia Research, 150(1), 136–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2013.07.047

- Allott, K., Proffitt, T.‐M., Mcgorry, P. D., Pantelis, C., Wood, S. J., Cumner, M., & Brewer, W. J. (2013). Clinical neuropsychology within adolescent and young‐adult psychiatry: Conceptualizing theory and practice. Applied Neuropsychology: Child, 2(1), 47–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2012.670566

- American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology. (2007). American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology (AACN) practice guidelines for neuropsychological assessment and consultation. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 21(2), 209–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825580601025932

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

- Bowie, C. R., Depp, C., Mcgrath, J. A., Wolyniec, P., Mausbach, B. T., Thornquist, M. H., … Pulver, A. E. (2010). Prediction of real‐world functional disability in chronic mental disorders: A comparison of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(9), 1116–1124.

- Braun, M., Tupper, D., Kaufmann, P., Mccrea, M., Postal, K., Westerveld, M., … Deer, T. (2011). Neuropsychological assessment: A valuable tool in the diagnosis and management of neurological, neurodevelopmental, medical, and psychiatric disorders. Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology, 24(3), 107–114. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNN.0b013e3182351289

- Brearly, T. W., Shura, R. D., Martindale, S. L., Lazowski, R. A., Luxton, D. D., Shenal, B. V., & Rowland, J. A. (2017). Neuropsychological test administration by videoconference: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Neuropsychology Review, 27(2), 174–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-017-9349-1

- College of Clinical Neuropsychologists. (2012). Practice survey 2011. Melbourne, Australia: Australian Psychological Society https://groups.psychology.org.au/GroupContent.aspx?ID=5076

- Cunningham, C. T., Quan, H., Hemmelgarn, B., Noseworthy, T., Beck, C. A., Dixon, E., … Jette, N. (2015). Exploring physician specialist response rates to web‐based surveys. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 15, 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-015-0016-z

- Fisher, C. A., Hetrick, S. E., Merrett, Z., Parrish, E. M., & Allott, K. (2017). Neuropsychology and youth mental health in Victoria: The results of a clinical service audit. Australian Psychologist, 52(6), 453–460.

- Fusar‐poli, P., Deste, G., Smieskova, R., Barlati, S., Yung, A. R., Howes, O., … Borgwardt, S. (2012). Cogntive functioning in prodromal psychosis: A meta‐analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69(6), 562–571.

- Goodall, J., Fisher, C., Hetrick, S., Phillips, L., Parrish, E. M., & Allott, K. (2018). Neurocognitive functioning in depressed young people: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Neuropsychology Review, 28(2), 216–231.

- Gore, F. M., Bloem, P. J., Patton, G. C., Ferguson, J., Joseph, V., Coffey, C., … Mathers, C. D. (2011). Global burden of disease in young people aged 10‐24 years: A systematic analysis. Lancet, 377(9783), 2093–2102. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60512-6

- Gorske, T. T., & Smith, S. R. (Eds.). (2009). Collaborative therapeutic neuropsychological assessment. New York, NY: Springer Science and Business Media.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

- Hamilton, M. P., Hetrick, S. E., Mihalopoulos, C., Baker, D., Browne, V., Chanen, A. M., … Mcgorry, P. D. (2017a). Identifying attributes of care that may improve cost‐effectiveness in the youth mental health service system. The Medical Journal of Australia, 207(10), S27–S37.

- Hamilton, M. P., Hetrick, S. E., Mihalopoulos, C., Baker, D., Browne, V., Chanen, A. M., … Mcgorry, P. D. (2017b). Targeting mental health care attributes by diagnosis and clinical stage: The views of youth mental health clinicians. The Medical Journal of Australia, 207(10), S19–S26.

- Hauser, M., Zhang, J. P., Sheridan, E. M., Burdick, K. E., Mogil, R., Kane, J. M., … Correll, C. U. (2017). Neuropsychological test performance to enhance identification of subjects at clinical high risk for psychosis and to be most promising for predictive algorithms for conversion to psychosis: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 78(1), E28–E40. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.15r10197

- Hermens, D. F., Naismith, S. L., Lagopoulos, J., Lee, R. S., Guastella, A. J., Scott, E. M., & Hickie, I. B. (2013). Neuropsychological profile according to the clinical stage of young persons presenting for mental health care. BMC Psychology, 1(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/2050-7283-1-8

- Hetrick, S. E., O'connor, D. A., Stavely, H., Hughes, F., Pennell, K., Killackey, E., & Mcgorry, P. D. (2017). Development of an implementation guide to facilitate the roll‐out of early intervention services for psychosis. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12420. [Epub ahead of print]

- Khandaker, G. M., Stochl, J., Zammit, S., Lewis, G., & Jones, P. B. (2014). A population‐based longitudinal study of childhood neurodevelopmental disorders, IQ and subsequent risk of psychotic experiences in adolescence. Psychological Medicine, 44(15), 3229–3238. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291714000750

- King, B. H. (2016). Psychiatric comorbidities in neurodevelopmental disorders. Current Opinion in Neurology, 29, 113–117. https://doi.org/10.1097/wco.0000000000000299

- Lee, R. S., Hermens, D. F., Naismith, S. L., Lagopoulos, J., Jones, A., Scott, J., … Hickie, I. B. (2015). Neuropsychological and functional outcomes in recent‐onset major depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia‐spectrum disorders: A longitudinal cohort study. Translational Psychiatry, 5, e555. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2015.50

- Lee, R. S., Hermens, D. F., Porter, M. A., & Redoblado‐hodge, M. A. (2012). A meta‐analysis of cognitive deficits in first‐episode major depressive disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 140(2), 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.10.023

- Lee, R. S., Hermens, D. F., Redoblado‐hodge, M. A., Naismith, S. L., Porter, M. A., Kaur, M., … Hickie, I. B. (2013). Neuropsychological and socio‐occupational functioning in young psychiatric outpatients: A longitudinal investigation. PLoS One, 8(3), e58176. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0058176

- Lee, R. S., Hermens, D. F., Scott, J., Redoblado‐hodge, M. A., Naismith, S. L., Lagopoulos, J., … Hickie, I. B. (2014). A meta‐analysis of neuropsychological functioning in first‐episode bipolar disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 57, 1–11.

- Lezak, M. D., Howieson, D. B., & Loring, D. W. (2004). Neuropsychological assessment (4th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Mcgorry, P. D., Keshavan, M., Goldstone, S., Amminger, P., Allott, K., Berk, M., … Hickie, I. (2014). Biomarkers and clinical staging in psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 13, 211–223.

- Mcgorry, P. D., Tanti, C., Stokes, R., Hickie, I. B., Carnell, K., Littlefield, L. K., & Moran, J. (2007). headspace: Australia's National Youth Mental Health Foundation‐‐where young minds come first. The Medical Journal of Australia, 187(7 Suppl), S68–S70.

- Mesholam‐gately, R., Giuliano, A. J., Faraone, S. V., Goff, K. P., & Seidman, L. J. (2009). Neurocognition in first‐episode schizophrenia: A meta‐analytic review. Neuropsychology, 23(3), 315–336. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014708

- Meyer, G. J., Finn, S. E., Eyde, L. D., Kay, G. G., Moreland, K. L., Dies, R. R., … Reed, G. M. (2001). Psychological testing and psychological assessment. A review of evidence and issues. American Psychologist, 56(2), 128–165.

- MSAC. (2015). 1400—Clinical neuropsychology assessment services. Retrieved from http://www.msac.gov.au/internet/msac/publishing.nsf/Content/1400‐public

- National Mental Health Commission. (2014). The national review of mental health programmes and services. Sydney: National Mental Health Commission, Australian Government.

- O'dea, B., Glozier, N., Purcell, R., Mcgorry, P. D., Scott, J., Feilds, K. L., … Hickie, I. B. (2014). A cross‐sectional exploration of the clinical characteristics of disengaged (NEET) young people in primary mental healthcare. BMJ Open, 4(12), e006378. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006378

- Proffitt, T. M., Brewer, W. J., Parrish, E. M., Mcgorry, P. D., & Allott, K. (2018). Reasons for referral and findings of clinical neuropsychological assessment in youth with mental illness: A clinical file audit. Applied Neuropsychology: Child, 7(2), 164–174.

- Rickwood, D. J., Telford, N. R., Mazzer, K. R., Parker, A. G., Tanti, C. J., & Mcgorry, P. D. (2015). The services provided to young people through the headspace centres across Australia. Medical Journal of Australia, 202(10), 533–536.

- Rickwood, D. J., Telford, N. R., Parker, A. G., Tanti, C. J., & Mcgorry, P. D. (2014). headspace—Australia's innovation in youth mental health: Who are the clients and why are they presenting? Medical Journal of Australia, 200(2), 108–111.

- Roebuck‐spencer, T. M., Glen, T., Puente, A. E., Denney, R. L., Ruff, R. M., Hostetter, G., & Bianchini, K. J. (2017). Cognitive screening tests versus comprehensive neuropsychological test batteries: A National Academy of neuropsychology education paper. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 32(4), 491–498. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acx021

- Sellars, M., Detering, K. M., & Silvester, W. (2015). Current advance care planning practice in the Australian community: An online survey of home care package case managers and service managers. BMC Palliative Care, 14, 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-015-0018-y

- Stain, H. J., Payne, K., Thienel, R., Michie, P., Carr, V., & Kelly, B. (2011). The feasibility of videoconferencing for neuropsychological assessments of rural youth experiencing early psychosis. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 17(6), 328–331. https://doi.org/10.1258/jtt.2011.101015

- Temple, R. O., Carvalho, J., & Tremont, G. (2006). A national survey of physicians' use of and satisfaction with neuropsychological services. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 21(5), 371–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acn.2006.05.002

- Zakzanis, K. K., Campbell, Z., & Polsinelli, A. (2010). Quantitative evidence for distinct cognitive impairment in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Journal of Neuropsychology, 4(4(Pt 1), 89–106. https://doi.org/10.1348/174866409x459674