Abstract

Objective

The aims of this systematic literature review were to identify and synthesise all relevant information about targeted parents’ characteristics and experiences from their own perspective.

Method

The academic databases Web of Science, PsycINFO, PubMed, EMBASE‐ELSEVIER, The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and conference abstracts were systematically searched from their inception until May 2018. The systematic review followed the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses protocol (PRISMA‐P) and was registered in PROSPERO (ID = CRD42017062533).

Results

Nine relevant articles were included after conducting inclusion criteria and quality assessment. Data were collated and analysed using guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews.

Conclusion

Targeted parents report consistent stories about the nature of the alienation tactics used by alienating parents across the included studies. Targeted parents expressed dissatisfaction with legal and mental health system services available to them. Further, despite feeling despair, frustration, and isolation, targeted parents appear to be resilient and seek out positive coping strategies. This review showed that research on targeted parents from their own perspective is sparse, and more studies are needed.

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC?

Parental alienation occurs during and after family separation, especially in legal and therapeutic contexts when child custody is disputed.

The targeted parent is the parent alienated from their children without reasonable justification.

Although there is some description of the targeted parent's experience in the literature, there has been no systematic review of the literature to date examining their experiences and characteristics.

WHAT THIS TOPIC ADDS?

This is the first academic systematic literature review of the experience of alienating behaviours from the targeted parent perspective.

This study shows that more research is needed into the targeted parents’ experience of alienating behaviours.

Despite the lack of studies, common targeted parent experiences were described in the literature such as feelings of isolation and reports of dissatisfaction with legal and mental health services.

INTRODUCTION

Parental alienation is a phenomenon that occurs during and after family separation. It can be defined as the outcome of one parent influencing their child to turn against their other parent (Bernet, Boch‐Galhau, Baker, & Morrison, Citation2010; Garber, Citation2011) without legitimate justification (Bernet & Baker, Citation2013). The child (referred to as the targeted child) is encouraged to refuse or resist a relationship with the other parent (targeted parent) and align themselves with the alienating parent (Garber, Citation2011). Some authors have suggested that parental alienation is a form of child abuse or family violence (Baker & Ben‐Ami, Citation2011; Meier, Citation2009; Poustie, Matthewson, & Balmer, Citation2018; Reay, Citation2015). It is important to note that a child rejecting a parent on reasonable grounds, such as in response to abuse or neglect is estrangement (Garber, Citation2011), not parental alienation (Gardner, Citation2001; Reay, Citation2015). Parental alienation can occur even if the relationship between the targeted child and targeted parent was once a very positive one for the child (Darnall, Citation2011).

Parental alienation has been seen in legal and therapeutic contexts, especially in child custody disputes. However, the term has not been formally recognised as a result of controversy surrounding the notion of parental alienation as a syndrome. Gardner (Citation2002a) considered parental alienation as a syndrome (PAS) diagnosed in the targeted child. Gardner argued that this diagnosis is made on the basis of a cluster of eight symptoms.

The eight symptoms of PAS included: (a) ongoing denigration of the targeted parent; (b) weak, poor, or unrealistic rationalisations for rejecting the targeted parent; (c) an inability to display ambivalence toward the targeted parent; (d) claiming their resistance against the targeted parent derives from their own thinking (“independent‐thinker phenomenon”); (e) aligning with the alienating parent during conflict; (f) a lack of guilt regarding their treatment of the targeted parent; (g) existence of false and/or distorted accounts of events involving the targeted parent (borrowed scenarios); and (h) attempts to influence the views of others about the targeted parent (Gardner, Citation2002a). These symptoms usually appear together in almost all cases of moderate to severe parental alienation. In mild cases of parental alienation, the child may display some alienating behaviours, but is able to maintain contact with the targeted parent. In moderate cases, the child displays a variety of alienating behaviours and struggles with the transition from the alienating parent's care to the care of the targeted parent. Once they have made the transition, however, the child quickly settles and bonds with the targeted parent. In severe cases, the child is emphatic in their rejection of the targeted parent and refuses all contact (Gardner, Citation1998). Several authors suggest there is insufficient evidence to support the validation of PAS as a construct (Childress, Citation2015; Ellis, Citation2008; Kelly & Johnston, Citation2001; Meier, Citation2009; Walker & Shapiro, Citation2010), because it lacks an empirical foundation (Childress, Citation2015), and does not have a pathological basis (Kelly & Johnston, Citation2001). Nevertheless, the consensus in the literature is that parental alienation exists.

Although the targeted parent has been described as experiencing depression and anxiety during and after alienation (Kopetski, Citation1998), fear, post‐traumatic stress disorder, insomnia (Giancarlo & Rottmann, Citation2015), frustration, powerlessness, helplessness, and anger due to constant interference from the alienating parent (Baker, Citation2010; Baker & Andre, Citation2008; Baker & Darnall, Citation2006), many of these descriptions appear to be based on the perception of other informants such as the targeted child and practitioners. These descriptions do not provide a clear view of who targeted parents are and what their experience of alienating behaviours has been like for them. It is important to know what has been published about targeted parents from their own perspective in order to fully appreciate their needs as they respond and react to alienating behaviours. Hence, this study aims to identify and synthesise all relevant information about targeted parents’ characteristics and experiences from their own perspective in the existing academic literature. From this review, recommendations on how targeted parents can be better supported in psychological and legal interventions will be made along with recommendations for future research.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Design

The literature review search protocol followed the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses protocol (PRISMA‐P; Shamseer et al., Citation2015). The review was registered in PROSPERO (ID = CRD42017062533).

Procedure and search strategy

The academic databases searched from their inception until May 2018 were: Web of Science, PsycINFO, PubMED, and EMBASE‐ELSEVIER, using the following search terms: (parental alienation AND [targeted parent OR alienated parent]). The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and conference abstracts were also searched.

Article titles were screened and duplicates removed by one of the researchers. Relevant studies were exported to endnote. Abstracts were screened for relevance and double screened by another member of the research team. Two of the researchers reviewed the full text of these articles against the inclusion criteria.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Included articles had to meet the following inclusion criteria: qualitative, quantitative or mixed method studies from peer‐reviewed journals articles, book chapters or books. The articles or books needed to report on the characteristics and experiences of targeted parents from their own perspective. Any article describing the targeted parent experience from the perspective of another such as targeted children, practitioners or hypothetical case examples were excluded from this review. There were no restrictions on date of publication or language the articles were published in.

Data analysis

The data were analysed using guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews (Popay et al., Citation2006). Guidance is recommended when articles likely to include mixed methodologies are included (Garg, Hackam, & Tonelli, Citation2008). To ensure study quality and avoid bias, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) was used (Pluye et al., Citation2011) appraising methodological quality for quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods studies included in a review. Data were analysed by content and extracted by the following variables: author and year, study design, sample, research objectives, data collection, and findings.

RESULTS

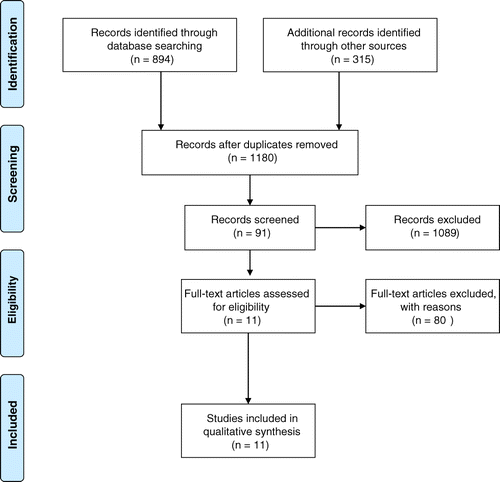

As shown in Figure 1, the number of articles identified from searching the electronic databases were 894 and a further 315 articles were identified from hand searches. After removing duplicates, 1,180 articles remained and the titles and abstract of these were reviewed for relevance. A total of 91 articles were identified. The full text of the 91 articles were screened independently by two researchers. Eleven articles (11%) met the inclusion criteria. Eighty articles (89%) were excluded from the review. See Table for a summary of reasons for exclusion.

Table 1. Reasons of articles excluded

Eight of the 11 included articles met 100% of the quality criteria using MMAT (Pluye et al., Citation2011). This means these articles met four criteria for each of the four domains: (a) research question, (b) methodology, (c) data analysis, and (d) responses rate. Three articles did not meet 100% of the quality criteria. Where possible, authors of these articles were contacted to obtain further information about the studies’ methodologies. Only one author, Dr. Despina Vassiliou, provided further information and this study met inclusion criteria. The remaining two articles were excluded from the analyses, because without the additional information eligibility for inclusion could not be confirmed. Thus, the final data analysis was conducted on nine articles.

As shown in Table , six of the studies included more males than females in the sample. One article (Finzi‐Dottan et al., Citation2012) included only females as a result of purposive sampling, and two other studies (Balmer et al., Citation2017; Poustie et al., Citation2018) had more females than males participating in the research. The studies were conducted mostly in the United States (six articles), two in Australia and one in Israel. However, the countries of residence of participants throughout the studies included United States, Canada, Israel, Australia, United Kingdom, New Zealand, India, Belgium, and Ireland.

Table 2. Demographic synthesis

Table shows a synthesis of the nine articles included in this review, six followed a quantitative descriptive design and three followed a qualitative design. For all the studies, the sample included targeted parents and the date of publication ranged from 1997 to 2018. The methods used in the studies to collect the data were through surveys (Baker, Citation2010; Baker & Darnall, Citation2006, Citation2007; Balmer et al., Citation2017; Harman et al., Citation2016; Poustie et al., Citation2018), in depth interviews (Finzi‐Dottan et al., Citation2012; Vassiliou & Cartwright, Citation2001) and the administration of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory 2 (MMPI‐2) and psychological assessment (Gordon et al., Citation2008).

Table 3. Articles synthesis

DISCUSSION

A systematic literature review was conducted to identify and synthesise all relevant information available in the academic literature reporting targeted parents’ characteristics and experiences from their own perspective. From nine articles meeting the inclusion criteria, only four of these specifically focused on the targeted parents’ characteristics and experiences (Balmer et al., Citation2017; Finzi‐Dottan et al., Citation2012; Poustie et al., Citation2018; Vassiliou & Cartwright, Citation2001). Moreover, only three of these studies were qualitative in design, two of them had small participant numbers (Finzi‐Dottan et al., Citation2012; Vassiliou & Cartwright, Citation2001) and were predominantly females (11 females vs. 5 males). However, despite the number of articles found and their features, it was still possible to obtain valuable information about the characteristics and experiences of targeted parents from their own voice.

Characteristics of targeted parents

According to the evidence provided by Gordon et al. (Citation2008), targeted parents were not responsible for being rejected by their child. Further, they did not present with any psychopathology. However, the alienating parents presented with psychopathology consistent with personality disorder. Similarly, Johnston and Campbell (Citation1998) described alienating parents as experiencing narcissistic injury with unresolved anger that may be a trigger for the alienation.

There is conflicting evidence in the literature regarding the parenting role of targeted parents. Balmer et al. (Citation2017) found targeted parents generally perceived themselves adequate and confident in their parental skills and their ability to discipline their children. They were motivated to be involved in their child's life, considered themselves able to set healthy boundaries with their children and encourage them to be autonomous (Balmer et al., Citation2017). The same authors found some gender differences, with mothers feeling more satisfied with being a parent than did fathers. Fathers reported being more involved with their children's activities than did mothers. Despite these gender differences, a general positive attitude toward their parental ability was experienced. In contrast, Vassiliou and Cartwright (Citation2001) described the targeted parents who participated in their study as experiencing a loss of their parental role and power due to parental alienation. The reasons for this variance are unclear and cannot be elucidated in this review due to the differences in the design, recruitment and location of the studies.

It is unclear from the literature whether mothers or fathers are more likely to become targeted parents. For decades, fathers have reportedly been more likely to be alienated from their children than mothers (Ellis & Boyan, Citation2010; Gardner, Citation1989, Citation2002a; Johnston, Citation2003; Meier, Citation2009; Rand, Citation1997a, Citation1997b; Vassiliou & Cartwright, Citation2001). Even Turkat (Citation1995) proposed the “divorce related malicious mother's syndrome” emphasising mothers as alienating parents. This is consistent with Gardner's (Citation2001, Citation2002a) assumptions that females are more commonly the alienating parent. However, three reasons can be provided to postulate why these gender assumptions may not be completely true.

First, some authors found more mothers participated in their research than was expected (Baker & Darnall, Citation2006; Balmer et al., Citation2017; Poustie et al., Citation2018), which would suggest that perhaps in previous studies the voluntary participation rate of fathers was higher. Second, past recruitment processes may have influenced the gender recruited. Third, in the past it was more common for mothers to obtain custody of their children, increasing the probabilities of positioning her as the alienating parent (Gardner, Citation2002a, Citation2002b).

The relationship between the severity of alienation and gender is also not entirely clear. Balmer et al. (Citation2017) found that mothers experienced significantly greater severity of exposure to parental alienation tactics compared to fathers. Specifically, targeted mothers reported experiencing significantly higher severity of exposure to denigration tactics at the hand of the alienating parent than did fathers. Harman et al. (Citation2016) reported no differences in the severity of the alienation between mothers and fathers.

There is not enough evidence to establish the mean age of the participants as a characteristic either. Although it was found that the mean age of the participants of the articles included was 42.8 years, no data was found regarding to the age of the participants when they first experienced alienating behaviours. This lack of clarity seems to be a consequence of the lack of information or the scarce number of studies examining these variables. Further, only three of the included studies reported on the age of the child at the time of data collection (Baker & Darnall, Citation2006, Citation2007; Balmer et al., Citation2017). From these studies, the common age range for children was 11–15-years of age. This is consistent with previous research indicating that older children are more susceptible to parental alienation (Johnston, Citation2003) because by adolescents they are physically able to stay with the parent they have aligned with. Moreover, children over the age of 12 are more likely than younger children to be asked by the Court during custody proceedings about their preferences regarding custody (Barnett & Wilson, Citation2004). No study reported on the age of the child when the alienation commenced, therefore no conclusions can be drawn in relation to the most common age targeted parents may see changes in their children as a consequence of alienating behaviours.

Targeted parents’ experiences of alienation and its impact

Targeted parents considered hate, anger, revenge or a combination of these as the trigger for the alienating parent's behaviour; feeling that their relationship with their children had been sabotaged by the alienating parent (Vassiliou & Cartwright, Citation2001). Targeted parents reported having experienced a variety of tactics by the alienating parent that contributed to the alienation including emotional manipulation, encouraging defiance and alliance, interrupting the time destined to spend with the targeted child, denying the targeted parent information about the child, defamation, and erasing the targeted parent from the child's life (Poustie et al., Citation2018). Similar findings were reported by Baker and Darnall (Citation2006) and Baker and Fine (Citation2014).

Targeted parents also reported their relationship with the alienating parent was strained after the onset of parental alienation; describing their alienating behaviours as severe (Baker & Darnall, Citation2006; Harman et al., Citation2016) and often involving a third party as an alienator such as a family member (Balmer et al., Citation2017), the child (Vassiliou & Cartwright, Citation2001) or their mother‐in‐law (Finzi‐Dottan et al., Citation2012). When considered together, these findings show that targeted parents feel isolated, despair, and frustrated (Balmer et al., Citation2017; Finzi‐Dottan et al., Citation2012; Poustie et al., Citation2018; Vassiliou & Cartwright, Citation2001) and they perceive themselves as victims of a series of strategies used by the alienating parent and their allies to turn the targeted child against them.

Targeted parents reported negative consequences of being exposed to alienating behaviour, such as dissatisfaction with the legal and mental health systems (Baker, Citation2010; Balmer et al., Citation2017; Poustie et al., Citation2018; Vassiliou & Cartwright, Citation2001), emotional and financial implications (Poustie et al., Citation2018; Vassiliou & Cartwright, Citation2001), and psychological distress (Baker, Citation2010; Balmer et al., Citation2017; Poustie et al., Citation2018). Targeted parents described their experiences with the legal system as slow, ineffective, uncaring, and contributing to the alienation (Poustie et al., Citation2018). This was also shown in Baker (Citation2010), who reported the duration of legal disputes ranged from one to 10 years and during this period, targeted parents reported having their case heard by several judges, hindering procedural continuity. They also reported encountering attorneys and judges who do not appear to understand parental alienation and the relevant concerns in such cases.

The lack of understanding of parental alienation by those involved in the legal and mental health systems may be contributing to increased feelings of anxiety and depression in targeted parents (Baker, Citation2010; Balmer et al., Citation2017). It cannot be ascertained if the psychological outcomes experienced by targeted parents were indeed a consequence of parental alienation or one of a series of precipitating factors of the alienation. Only one study (Balmer et al., Citation2017) used a validated instrument to measure these clinical variables, which confirms the need to further assess the impact of parental alienation on the targeted parent.

As part of the experiences of the alienation, targeted parents have reported some coping strategies they have used to endure the process. These strategies include self‐education, educating others, finding social support and being stoic (Poustie et al., Citation2018). This finding indicates that many targeted parents are resilient and seek out active coping strategies.

Cultural concerns

There is a narrow picture of parental alienation and who targeted parents are around the world. Most studies included in this review were conducted in the United States (six articles). Only one study used an international sample (Balmer et al., Citation2017) and one small study of six targeted parents was conducted in Israel (Finzi‐Dottan et al., Citation2012). See Table for demographic variables.

According to the findings of this review, in Israel targeted mothers experienced abuse, discord, rejection, isolation, and detachment from significant figures in their lives, including parents, husband, extended family, husband's family, and their own children (Finzi‐Dottan et al., Citation2012). Similar perceptions were reported by targeted parents from English‐speaking countries (Baker & Darnall, Citation2006; Balmer et al., Citation2017; Harman et al., Citation2016; Vassiliou & Cartwright, Citation2001). It is important to expand this picture of parental alienation in order to create a better understanding of the targeted parent and the parental alienation phenomenon cross‐culturally.

Recommendations for practitioners

Based on the findings of this study, it is recommended that practitioners need to be aware that mothers and fathers can be alienated from their children. This is important because a prevailing misconception is that targeted parents tend to be fathers. It is important that practitioners working in family law and family mental health become aware of parental alienation and its consequences. Further, practitioners need to be aware that targeted parents can experience symptoms of depression and anxiety and their symptomatology must be factored into any intervention strategies developed by practitioners.

Limitations of this study and recommendations for research

The following limitations were identified in this review. Firstly, the scarce number of articles meeting inclusion criteria and the methodological nature of the studies restricted any possibility to compare the findings or conduct a meta‐analysis. Secondly, the review was limited to published peer‐reviewed research excluding grey literature. Finally, the findings of this review may not be generalisable as most of the studies were conducted in the United States and therefore lacking information across cultures.

In addition, caution is needed when drawing conclusions from the results presented in this review. For example, full diagnostic interviews or psychological assessments would be more accurate to confirm that targeted parents suffered anxiety, depression, and stress during the process of parental alienation; the interviews and surveys of the studies included did not report the time the alienation occurred or the age of the targeted parents experiencing the alienation.

One important outcome of this systematic literature review was that there is a gap in the literature about targeted parents and their experience of being alienated from their children. The present literature review has identified many questions that need further investigation such as, who is more likely to become a targeted parent? What is the impact of parental alienation on the emotional and physical wellbeing of the targeted parent? How do targeted parents cope with the alienation and what can practitioners do to help? How are these issues similar or different cross‐culturally and between mothers and fathers?

Future studies investigating personality profiles of alienating and targeted parents may help elucidate whether there are any common characteristics shared by targeted parents and alienating parents. It is also necessary to develop valid and reliable instruments to measure parental alienation and assess risk of becoming a targeted parent. In general, more qualitative studies are needed to understand the experience of targeted parents from their perspective and more quantitative studies are required to elaborate a profile of the targeted parent. Understanding how individuals experience parental alienation and identifying the common characteristics might be the first step to assist in the development of appropriate interventions.

CONCLUSION

The present study has provided valuable insights into the characteristics and experiences of targeted parents of parental alienation from their own perspective, despite the scarce number of studies found in the academic literature. However, more information about parental alienation is needed with more studies about targeted parents in order to further understand their needs.

The importance of this study lies in being the starting point for future research. We have identified gaps in the literature that will serve to initiate a new line of research that will help mental health and legal professionals in their work with targeted parents. If families, parents, mental health and legal professionals understand what parental alienation is and how targeted and alienating parents behave, then perhaps the cases of alienation might decrease.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no potential conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

- Baker, A. J. L. (2010). Even when you win you lose: Targeted parents’ perception of their attorneys. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 38, 292–309.

- Baker, A. J. L., & Andre, K. (2008). Working with alienated children and their targeted parents: Suggestions for sound practices for mental health professionals. Annals of the American Psychotherapy Association, 11, 10.

- Baker, A. J. L., & Ben‐ami, N. (2011). To turn a child against a parent is to turn a child against himself: The direct and indirect effects of exposure to parental alienation strategies on self‐esteem and wellbeing. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 52, 472–489. https://doi.org/10.1080/10502556.2011.609424

- Baker, A. J. L., & Darnall, D. C. (2006). Behaviors and strategies employed in parental alienation. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 45(1–2), 97–124. https://doi.org/10.1300/J087v45n01_06

- Baker, A. J. L., & Darnall, D. C. (2007). A construct study of the eight symptoms of severe parental alienation syndrome. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 471(2), 55–75. https://doi.org/10.1300/J087v47n01_04

- Baker, A. J. L., & Fine, P. R. (2014). Surviving parental alienation: A journey of hope and healing. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Balmer, S., Matthewson, M., & Haines, J. (2017). Parental alienation: Targeted parent perspective. Australian Journal of Psychology., 70, 91–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12159

- Barnett, C., & Wilson, C. J. (2004). Children's “wishes” in the Australian Family Court: Are they wishful thinking? Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 11(1), 73–78. https://doi.org/10.1375/pplt.2004.11.1.73

- Bernet, W., & Baker, A. (2013). Parental alienation, DSM‐5, and ICD‐11: Response to critics. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 41, 98–104.

- Bernet, W., Boch‐galhau, W. V., Baker, A. J. L., & Morrison, S. L. (2010). Parental alienation, DSM‐V, and ICD‐11. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 36, 76–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926180903586583

- Childress, C. (2015). An attachment‐based model of parental alienation: Foundations. Claremont, CA: Oaksong Press.

- Darnall, D. (2011). The psychosocial treatment of parental alienation. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 20, 479–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2011.03.006

- Ellis, E. (2008). A stepwise approach to evaluating children for parental alienation syndrome. Journal of Child Custody: Research, Issues, and Practices, 4, 55–78. https://doi.org/10.1300/J190v04n01_03

- Ellis, E. M., & Boyan, S. (2010). Intervention strategies for parent coordinators in parental alienation cases. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 38(3), 218–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926181003757074

- Finzi‐dottan, R., Goldblatt, H., & Cohen‐masica, O. (2012). The experience of motherhood for alienated mothers. Child and Family Social Work, 17, 316–325. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2011.00782.x

- Garber, B. (2011). Parental alienation and the dynamics of the enmeshed parent–child dyad: Adultification, parentification, and infantilization. Family Court Review, 49, 322–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-1617.2011.01374.x

- Gardner, R. A. (1989). Family evaluation in child custody mediation, arbitration, and litigation. Cresskill, NJ: Creative Therapeutics.

- Gardner, R. A. (1998). Recommendations for dealing with parents who induce a parental alienation syndrome in their children. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 28, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1300/J087v28n03_01

- Gardner, R. A. (2001). Should courts order PAS children to visit/reside with the alienated parent? A follow‐up study. The American Journal of Forensic Psychology, 19(3), 61–106.

- Gardner, R. A. (2002a). Denial of the parental alienation syndrome also harms women. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 30, 191–202.

- Gardner, R. A. (2002b). Parental alienation syndrome v/s parental alienation: Which diagnosis should evaluators use in child‐custody disputes? The American Journal of Family Therapy, 30, 93–115.

- Garg, A. X., Hackam, D., & Tonelli, M. (2008). Systematic review and meta‐analysis: When one study is just not enough. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 3, 253–260. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.01430307

- Giancarlo, C., & Rottmann, K. (2015). Kids come last: The effect of family law involvement in parental alienation. The International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences: Annual Review, 9, 27–43.

- Gordon, R., Stoffey, R., & Bottinelli, J. (2008). MMPI‐2 findings of primitive defences in alienating parents. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 36, 211–228.

- Harman, J., Leder‐elder, S., & Biringen, Z. (2016). Prevalence of parental alienation drawn from a representative poll. Children and Youth Services Review, 66, 62–66.

- Johnston, J. R. (2003). Parental alignments and rejection: An empirical study of alienation in children of divorce. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 31, 158–170.

- Johnston, J. R., & Campbell, L. E. (1998). Impasses of divorce: The dynamics and resolution of family conflict. New York, NY: The Free Press.

- Kelly, J. B., & Johnston, J. R. (2001). The alienated child: A reformulation of parental alienation syndrome. Family Court Review, 39(3), 249–266. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.174-1617.2001.tb00609.x

- Kopetski, L. M. (1998). Identifying cases of parental alienation syndrome—part II. The Colorado Lawyer, 27(3), 61–64.

- Meier, J. S. (2009). A historical perspective on parental alienation syndrome and parental alienation. Journal of Child Custody, 6, 232–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/15379410903084681

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Prisma Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097.

- Pluye, P., Robert, E., Cargo, M., Bartlett, G., O'cathain, A., Griffiths, F., Boardman, F., Gagnon, M. P., & Rousseau, M. C. (2011). Proposal: A mixed methods appraisal tool for systematic mixed studies reviews. Retrieved from http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com.

- Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., Britten, N., Roen, K., & Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. Final report. Lancaster, CA: Institute of Health Research.

- Poustie, C., Matthewson, M., & Balmer, S. (2018). The forgotten parent: The targeted parent perspective of parental alienation. Journal of Family Issues, 39, 3298–3323. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513XI8777867

- Rand, D. C. (1997a). The spectrum of parental alienation syndrome (part I). American Journal of Forensic Psychology, 15(3), 1–50.

- Rand, D. C. (1997b). The spectrum of parental alienation syndrome (part II). American Journal of Forensic Psychology, 15(4), 1–33.

- Reay, K. (2015). Family reflections: A promising therapeutic program designed to treat severely alienated children and their family system. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 43, 197–207.

- Shamseer, L., Moher, D., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberatu, A., Petticrew, M., … PRISMA‐P Group. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta‐analysis protocols (PRISMA‐P): Elaboration and explanation. BMJ, 349, g7647. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7647

- Turkat, I. D. (1995). Divorce related malicious mother syndrome. Journal of Family Violence, 10(3), 253–264.

- Vassiliou, D., & Cartwright, G. F. (2001). The lost parents’ perspective on parental alienation syndrome. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 29(3), 181–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/019261801750424307

- Walker, L. E., & Shapiro, D. L. (2010). Parental alienation disorder: Why label children with a mental diagnosis? Journal of Child Custody, 7(4), 266–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/15379418.2010.521041