Abstract

Objective

This study investigated the reliability and factor structure of the General Health Questionnaire‐12 (GHQ‐12) in children and adolescents and examined whether the GHQ‐12 is sensitive to expected mental well‐being differences across age and sex.

Method

Here, N = 180,700 Australian students (7–19 years of age) completed the GHQ‐12 as part of a larger survey, the Resilience Survey (Resilient Youth Australia Limited). Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted, and internal consistency was assessed with Cronbach's alpha. Linear mixed model ANOVAs were conducted to investigate differences in GHQ‐12 scores between females and males.

Results

EFA revealed a two‐factor model which was consistent across all age bands—Factor A: General Dysphoria (depression and anxiety), and Factor B: General Functioning (ability to cope with day‐to‐day activities). Internal consistency was good (Cronbach's α > 0.7) in all age bands for total GHQ‐12 and factor scores. Confirmatory factor analysis with a two‐factor correlated structure supported EFA results. Bifactor modelling suggested a unidimensional structure. Males aged 7–9 years had significantly higher (more problematic) total GHQ‐12 scores, General Dysphoria scores and General Functioning scores than females (p < 0.001), and females aged 12–19 years had significantly higher scores than males (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Our results support the use of the GHQ‐12 for the measurement of mental well‐being symptoms in children from 7 to 19 years of age. Overall, psychometric properties including sensitivity, suggest that the GHQ‐12 provides a robust indicator of short‐term mental state in children and adolescents.

Funding information Resilient Youth Australia

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

The General Health Questionnaire‐12 (GHQ‐12) is commonly used in adult populations. It has good internal consistency and is a sensitive measure of mental well‐being in adults.

In the adult literature, two‐factor, three‐factor, and unidimensional structure models have been proposed as optimal.

The GHQ‐12 has been used with adolescents as young as 11 years of age, but the psychometric properties have not been assessed in younger populations.

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS

This is the first paper to analyse the psychometric properties of the General Health Questionnaire‐12 (GHQ‐12) in primary as well as secondary school‐aged children. A two‐factor structure was found to be stable across ages 7–19 years.

The GHQ‐12 had good internal consistency across ages 7–19 years and appears to be sensitive to expected changes in mental well‐being with age.

This article provides GHQ‐12 scores for females and males aged 7–19 years from a large cohort which may be useful in clinical settings and within schools.

INTRODUCTION

The General Health Questionnaire (Goldberg, McDowell, & Newell, Citation1972) is a widely used instrument for assessing mental well‐being in adults. Initially conceived as a 60‐item instrument, several short forms have been developed with the most widely established being the 12‐item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ‐12). The GHQ‐12 is reported to demonstrate strong psychometric properties, although debate exists as to whether it is a unitary or multidimensional measure containing two or possibly three factors. Originally designed for adult populations, the GHQ‐12 has been used with success in adolescent populations with similar psychometric findings to those in adults. This includes studies that have used children as young as 11 years of age. This raises the possibility that the GHQ‐12 may be adaptable for use in preadolescent children. For the past 6 years, Resilient Youth Australia (RYA) Limited, a charitable institution in Victoria, Australia, have been conducting an omnibus Resilience Survey which incorporates the GHQ‐12 to more than 180,000 students aged 7–19 years in over 600 schools. However, to date, the psychometric properties of the GHQ‐12 in preadolescent children remain to be explored.

The psychometric properties of the GHQ‐12 have been extensively tested in both older and younger adolescents (French & Tait, Citation2004). The GHQ‐12 in adolescents is reported to demonstrate high internal consistency with Cronbach's alphas ranging from 0.81 to 0.89 (Baksheev, Robinson, Cosgrave, Baker, & Yung, Citation2011; French & Tait, Citation2004; Mann et al., Citation2011; Politi, Piccinelli, & Wilkinson, Citation1994; Suzuki et al., Citation2011; Tait, French, & Hulse, Citation2003). It is reported to demonstrate good predictive validity with high GHQ‐12 scores predicting poor mental well‐being (Schrnitz, Kruse, & Tress, Citation1999) and elevated depression, anxiety, self‐esteem, and stress scores (Mann et al., Citation2011; Tait et al., Citation2003). The GHQ‐12 also shows good discriminant validity with elevated GHQ‐12 scores distinguishing between adolescents in hospital with or without alcohol‐ or drug‐related problems (Tait et al., Citation2003) and those with or without emotional disturbances according to psychiatrist ratings and scores on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (Politi et al., Citation1994). It also performs better than chance at identifying adolescents who on diagnostic interview have disorders of depression and anxiety (Baksheev et al., Citation2011). Studies examining the construct validity of the GHQ‐12 in adolescents typically report two or three factor solutions. For example, using principle component analysis to explore factor structure Politi et al. (Citation1994), in a sample of 320 Italian males aged 18 years, report a two‐factor solution (“General Dysphoria” and “Social Dysfunction”) and, likewise, Suzuki et al. (Citation2011) report a two‐factor solution in a large sample of almost 100,000 Japanese adolescents from grades 7 to 12 (“Depression/Anxiety” and “Loss of Positive Emotion”). By contrast, Graetz (Citation1991) in a large study of 8,998 Australian adolescents and adults aged 16–25 years report a three‐factor solution (“Social Dysfunction,” “Anxiety/Depression,” and “Loss of Confidence”), a factor structure that was replicated using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) by French and Tait (Citation2004) in 236 Australian adolescents aged 11–15 years and Padrón, Galán, Durbán, Gandarillas, and Rodríguez‐Artalejo (Citation2012) in a large sample of 4,146 Spanish adolescents aged 13–18 years.

A point of contention in relation to the factor structure of the GHQ‐12 is the suggestion that the positively and negatively worded items may result in an artefactual dual‐factor model, whereby all positively worded items load onto one factor, and negatively worded items load onto the other (Gnambs & Staufenbiel, Citation2018; Smith, Oluboyede, West, Hewison, & House, Citation2013; Wang & Lin, Citation2011). A recent set of meta‐analyses investigating a large number of studies has shed light on this debate, with a series of exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and CFA yielding results that suggest that the GHQ‐12 is best described as a unidimensional construct (Gnambs & Staufenbiel, Citation2018). While these analyses included studies (N = 129) with participants (N = 487,113) ranging in age from 13 to 100 years, the samples included predominantly young and older adults, as consistent with the literature in general (meta‐analysis I, mean age = 37, SD = 16 years; meta‐analysis II, mean age = 45, SD = 20).

Indeed, in contrast to the data for adolescents and adults, the psychometric properties of the GHQ‐12 in younger children are less well established. It has been used successfully in children as young as 11 years of age despite reservations about the possible lack of understanding of mental well‐being concepts in young children, and the methodological problem of negatively worded items in the GHQ‐12 and susceptibility of young children to negative item biases (Hennessy, Swords, & Heary, Citation2008; Marsh, Citation1986). Whether children younger than 11 years can meaningfully complete the GHQ‐12 and whether they interpret the GHQ‐12 similarly to young adolescents is yet to be examined. Using EFA and CFA to examine the factor structure of responses, we explored these questions in a large sample of 180,700 Australian children aged 7–19 years.

METHODS

Participants

A convenience sample was utilised, whereby RYA administered the survey to schools whose principals agreed to participation. N = 180,700 (males = 89,708; females = 90,335; gender diverse = 657, age range 7–19 years) school students in year levels 3–12 undertook the survey between 2012 and 2017. Students were from 634 participating schools in all states and territories of Australia (Victoria = 73.7%, Queensland = 15.3%, South Australia = 8.0%, Tasmania = 1.9%, Western Australia = 0.5%, Northern Territory = 0.3%, New South Wales = 0.2%, and Australian Capital Territory = 0.1%), and resided in 3,479 suburbs. Schools were a mix of state and private schools in suburban and regional areas. Students from a spread of differing socioeconomic status (SES) areas were involved in the study, with Index of Relative Socio‐economic Advantage and Disadvantage (ABS, Citation2016) scores ranging from one (lowest SES) to 10 (highest SES). Demographic information (N per sex and age) is presented in Table .

Table 1. Sample size and gender profile of each age group

Design

The GHQ‐12 was administered to participants during class time as part of a larger survey. The Resilience Survey (RYA Limited) consists of 98 questions for primary and 99 questions for secondary students, and includes the Children's Hope Scale (6 items) (Snyder et al., Citation1997) and under licence agreement the GHQ‐12 (12 items) (Goldberg et al., Citation1997), and Developmental Asset Profile (58 items) (Scales & Leffert, Citation1999). The survey also includes demographic items and approximately 23 practice‐derived questions on risk and protective behaviours. The Resilience Survey was administered electronically via an online web‐based application and took between 30 and 60 min to complete, largely depending on the age of the respondent. The GHQ‐12 itself took approximately 5 min to complete and was located halfway through the omnibus survey. Teacher supervision was utilised to ensure students completed the survey in a thorough manner and understood each question. Prior to commencing the survey, participants were informed that their responses would remain strictly confidential and were nonidentifiable at the individual level (group means only). The participants were also told to speak to a staff member if the survey questions raised any issues for them.

The GHQ‐12 asks questions about mental well‐being in the context of how the respondent's current state differs from his or her usual state. As part of the Resilience Survey, all GHQ‐12 questions required a response on a 4‐point Likert scale (1 = not at all/less than usual; 4 = much more than usual). In order to score the GHQ‐12 in accordance with the Likert scoring method (Goldberg et al., Citation1972), scores for each item were reverse coded such that a higher score represented more severe psychological distress. Scores were then recoded from a scale of 1–4 to a scale of 0–3. Scores from each of the 12 items were then added to give a total score ranging from 0 to 36, with a higher score reflective of worse psychological distress. The cut‐off score in adults that suggests psychological distress is 11/12 (Goldberg et al., Citation1997). In adolescents, a threshold score of 9/10 for males and 10/11 for females was found to be optimal for identifying depressive and anxiety disorders (Baksheev et al., Citation2011). Surveys with any missing data were excluded from analysis.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics Version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York), STATA Version 15.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas), and R Studio Version 1.1.423 (RStudio Inc., Boston, Massachusetts, 2009–2018). From a total of 229,018 responses, 48,318 were removed due to missing data, leaving a total of 180,700 participants who were included in the final analyses. Due to the small number of participants aged 7 years (N = 86) and 19 years (N = 188), age bands were created for analyses for ages 7–8 and 18–19 years.

Factor structure

Exploratory factor analysis

EFA has been used extensively in the examination of the GHQ‐12 (Hu, Stewart‐Brown, Twigg, & Weich, Citation2007;Politi et al., Citation1994 ; Suzuki et al., Citation2011). In order to mirror these studies in our sample, the factor structure of the 12 GHQ‐12 items was analysed using EFA with a principal axis factoring (extraction method). An oblique rotation (direct oblimin) was chosen as this method allows for correlation between factors, and previous studies have found GHQ‐12 items to be dependent (Graetz, Citation1991). In order to mirror previous studies, factors were retained on the basis of an eigenvalue greater than 1.00 (Politi et al., Citation1994; Suzuki et al., Citation2011), and significant contribution of the items within each factor were determined using a threshold for loading ≥0.3 (Politi et al., Citation1994). The number of factors obtained was also examined using parallel analysis, which involves generation of a random dataset (a parallel dataset), and the number of factors is chosen by examining how many factors in the real dataset have eigenvalues higher than those found in the simulated dataset (Çokluk & Koçak, Citation2016). Factor loadings, correlations, eigenvalues, explained variances, and communalities are reported for the sample as a whole, and by age band.

Confirmatory factor analysis

As described earlier, recent research suggests that while the GHQ‐12 is frequently analysed as a two‐, or three‐factor model, it is perhaps better described as a unidimensional construct (Gnambs & Staufenbiel, Citation2018) and that separate dimensions may be an artefact of positive, as opposed to negative, wording of items (Gnambs & Staufenbiel, Citation2018; Smith et al., Citation2013; Wang & Lin, Citation2011). In this context, we performed a series of (CFA) models, mirroring the one‐ and two‐factor structural models tested in Gnambs and Staufenbiel (Citation2018). Specifically, we used the SEM procedure in STATA 15 (Texas, Revision 19, 2017) to examine:

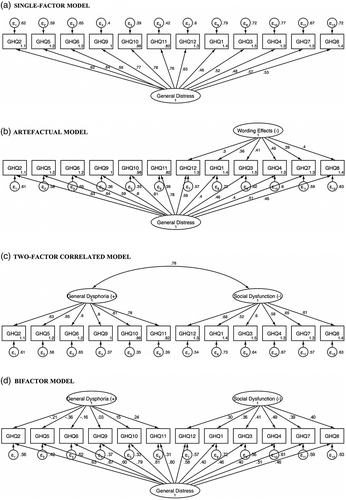

A single‐factor model (single factor that explains covariances between all items, Figure 1a).

An artefactual model (a general factor for all items and a specific factor for items that are negatively worded, Figure 1b).

A two‐factor correlated model (two correlated latent factors representing general dysphoria and social dysfunction, Figure 1c).

A bifactor model (a general factor and two orthogonal latent factors, Figure 1d).

Goodness‐of‐fit indices (model χ2, Comparative Fit Index, Standardised Root Mean Square Residual, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation [and associated p value, pclose] and Coefficient of Determination) were calculated for each model. Also reported for the bifactor model are omega hierarchical (ω h, the sum of the squared loadings on the general factor) and omega total (ω h, the sum of the squared loadings on all the factors) (McNeish, 2018).

Internal Consistency: Cronbach's alpha was used to assess internal consistency of the GHQ‐12. Cronbach's alpha is based on the average correlation of the items within a scale and a Cronbach's alpha of 0.7 or greater is considered robust (Nunnally, Citation1967).

Sensitivity: Linear mixed model ANOVA was conducted to investigate differences in GHQ‐12 scores by sex and age. Separate models specified dependent variables of total GHQ‐12 score and subscales, with fixed effects of sex, age, and the sex × age interaction, with a random effect of school ID on the intercept, to appropriately account for any serial correlation at the school level (Van Dongen, Olofsen, Dinges, & Maislin, Citation2004). Participants who identified as gender diverse were excluded from these models (results from this population will be the focus of a future paper) leaving a total of 180,043 participants for these specific analyses.

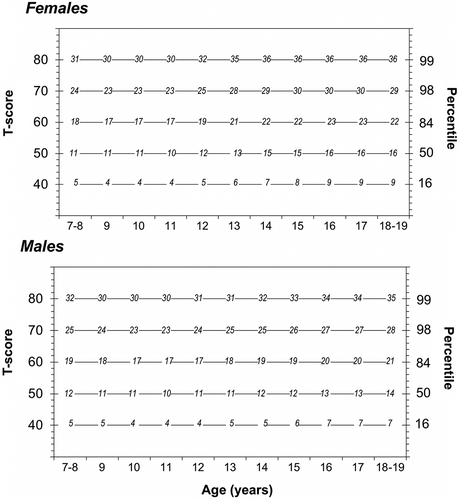

T‐Scores: In order to provide easily interpreted standardised scores to facilitate comparison with future studies, T‐scores were calculated for males and females in each age band and plotted in conjunction with percentile scores and raw scores. T‐scores are standardised scores, where a score of 50 represents the mean. A difference of 10 from the mean indicates a difference of one SD.

RESULTS

Factor analysis

EFAs using the traditional eigenvalue threshold (>1, Politi et al., Citation1994) revealed a two‐factor model, which was consistent across all age bands. Factor A (labelled the “General Dysphoria Subscale”) encompassed items measuring feelings of depression and anxiety, for example, “Have you recently been thinking of yourself as a worthless person”. Factor B (labelled the “General Functioning Subscale”) included items measuring difficulties in the ability to perform daily activities and cope with problems, for example, “Have you recently been able to enjoy your day‐to‐day activities”. The label for Factor A is consistent with naming conventions from previous research (Politi et al., Citation1994), while for Factor B, typically labelled “Social Dysfunction,” the label represents the items that load onto this subscale which are a measure of incapacity to make decisions and not feeling useful (which may or may not be socially related). Table presents item loadings for the overall sample and item loadings for each age band (Table S1, Supporting Information in Appendix S1). For ages 14 and 16–19 years, item GHQ12 “Have you recently been feeling reasonably happy, all things considered” loaded onto both Factor A: General Dysphoria and Factor B: General Functioning. However, for all age groups, item GHQ12 loaded most strongly onto Factor B: General Functioning. Factors A and B explained a cumulative total of 53.6% of the variance in the overall model. Item correlations for the overall sample are presented in Table S2 in Appendix S1. In contrast, Horn's parallel analysis for component retention suggested retention of only one component, with the scree plot clearly showing only one factor with an eigenvalue higher than the parallel dataset (adjusted eigenvalue = 1.6, estimated bias = 2.2).

Table 2. Item loadings for the overall sample

For the CFA, none of the models yielded a nonsignificant model χ2, indicating a less than optimal fit. However, all of the other fit indices were acceptable. Overall, the worst fit was found for the single‐factor model. The artefactual and two‐factor correlated models were comparable. The two latent factors (General Dysphoria and Social Dysfunction) were highly correlated (0.76). A general pattern was for the positively worded items to have higher factor loadings than the negatively worded items.

In the bifactor model, all items had loadings ≥0.4 on the General Dysphoria factor, while the highest loading onto the other two latent factors was 0.49, with 5 out of 12 items yielding factor loadings onto these factors of <0.3 (Table ). Reliability indicators also supported the existence of a single factor (ω h = 0.81, ωt = 0.90, general factor proportion of variance = 0.9). Therefore, results from this section onwards will describe the unidimensional model only (see Supporting Information for results relating to reliability, sensitivity, and T‐scores of the two‐factor model).

Table 3. Summary statistics (fit indices) for the four different models estimated using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) (reflecting models from Gnambs & Staufenbiel, Citation2018)

Reliability analyses

Reliability analyses (Table ) revealed robust reliability for total GHQ‐12 score in all age bands (Cronbach's α > 0.8).

Table 4. Cronbach's alpha per age band and the complete sample (OVERALL) for GHQ‐12 total score

Sensitivity analyses

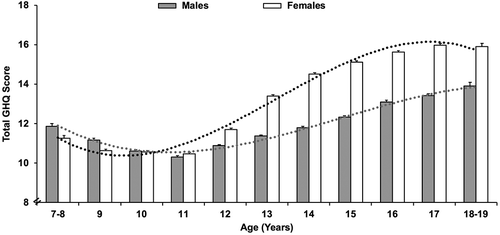

The average GHQ‐12 total score for the whole sample (N = 180,700) was 12.36 (SD 6.99). For total GHQ‐12 score, there were significant main effects of sex (p < 0.001), age (p < 0.001), and a significant sex × age interaction (p < 0.001) (Table ). Males aged 7–9 years had significantly higher GHQ‐12 scores (indicating worse mental well‐being) than females, there were no sex differences at 10 or 11 years, and from 12 to 19 years, females had significantly higher scores than males (p < 0.05; refer to Table S4 in Appendix S1 for mean scores and SDs per sex and age band). Effect sizes for sex differences ranged in size from minimal (Cohen's d = 0.09) in the age band with the smallest mean differences (7–8 years) through to medium (Cohen's d = 0.42) in the age band with the largest mean differences (15 years). The sex difference increased across the adolescent years (Figure 2; Figures S2 and S3 in Appendix S1). Lowest scores (indicative of best mental well‐being) were recorded at 11 years. Using this point as a reference, planned contrasts indicated that in males, this age was significantly better than all other ages (p < 0.05). For females, scores at 11 years were not significantly different than at 9 or 10 years, but were significantly better than 7–8 and 12–19 years (p < 0.05).

Table 5. Mixed effects ANOVA for sex, age, and the sex × age interaction for the General Health Questionnaire‐12 (GHQ‐12) total score

T‐scores

T‐scores for GHQ‐12 total scores are plotted separately for females and males across age groups in Figure 3 (see Supporting Information in Appendix S1 for T‐scores of subscales). Figures also display percentile rankings corresponding to each T‐score and GHQ‐12 score. For example, a total GHQ‐12 score of 30 in a 12‐year‐old male would equate to a T‐score of 80 (99th percentile).

DISCUSSION

The aim of the study was to assess factor structure, internal consistency, and sensitivity of the GHQ‐12 in Australian preadolescent (primary school‐aged) and adolescent (secondary school‐aged) children. The large dataset enabled us to examine, for the first time, use of the questionnaire in young people under 11 years old (and as young as 7 years old), in the context of a broad sample extending throughout secondary school. In contrast to the originally proposed three‐factor structure of the instrument used frequently in adult samples (Graetz, Citation1991), results of EFA yielded a two‐factor structure, in line with Politi et al. (Citation1994), that was consistent across all age bands. Internal consistency was also high across all age bands, expanding previous work (Baksheev et al., Citation2011; French & Tait, Citation2004; Mann et al., Citation2011; Politi et al., Citation1994; Suzuki et al., Citation2011; Tait et al., Citation2003). CFA of the two‐factor correlated structure and comparison to the single‐factor model also provided support for this two‐factor structure. However, consistent with Gnambs and Staufenbiel (Citation2018), examination of the bifactor and artefactual models suggested that the GHQ‐12 may indeed be best described by a single factor. Therefore, despite the fact that the two‐factor structure may be useful in practice‐based education settings to unpack findings and describe behaviours and feelings in schools, the unidimensional model may be most suitable for practitioners in clinical settings where diagnostic cut‐offs are used.

The instrument was shown to be sensitive to expected differences in sex and age (Baksheev et al., Citation2011; French & Tait, Citation2004; Hankin et al., Citation1998; Tait et al., Citation2003). These results establish the reliability and sensitivity of the GHQ‐12 in students from 7–19 years, providing norms by sex and age. Importantly, these norms, alongside the T‐score benchmarks, can be used, not only by researchers, but also by schools, to help teachers and administrators put scores, at the student or class level, in context. These data can also scaffold interpretation of scores in clinical settings.

The present results suggest that mental well‐being peaks at 11 years, which is also an age with the smallest sex differences in GHQ‐12 scores. Before this age, females have better scores than males, and while significant in this large sample, the sex difference is relatively small and consistent with previous findings (Angold & Worthman, Citation1993). Conversely, from 12 years of age corresponding to the onset of puberty and onwards GHQ‐12 scores for females become worse than for males, and this difference increases across adolescence, to early adulthood (Angold & Worthman, Citation1993; Baksheev et al., Citation2011; French & Tait, Citation2004; Hankin et al., Citation1998; Tait et al., Citation2003).

In addition to examining differences between males and females, the Resilience Survey also included the option for students to identify as gender diverse. While these students were included in the overall statistics presented in this article, they were not included in the analyses by sex due to the relatively small numbers (N = 657). Having a well‐validated measure of psychological distress in children who have identities that do not map onto heteronormative structures is critical, given the growing body of research suggesting that this may be associated with vulnerabilities in regard to mental well‐being (Bockting, Miner, Swinburne Romine, Hamilton, & Coleman, Citation2013). We propose to follow this up in a future study.

Results also raise interesting considerations about thresholds used for interpreting GHQ‐12 scores. The GHQ‐12 threshold considered to indicate psychological distress has been set at 11/12 in adult samples (Goldberg et al., Citation1997), and lower thresholds have been applied in cohorts of older adolescents, to identify depressive and anxiety disorders (10/11 for females, 9/10 for males; Baksheev et al., Citation2011). In the current sample, the mean score was 11/12 for the younger participants, and increased with age. Given the relatively high mean scores in our sample, establishing thresholds is an important area for further investigation. Establishing predictive validity (relative to clinical diagnoses, for example) across childhood and adolescence in large samples would be highly beneficial to set meaningful cut‐off scores, particularly for children younger than 11 years.

A further area for future work, especially in young children, is to interrogate the factor structure of the GHQ. Our results were highly consistent with Gnambs and Staufenbiel (Citation2018), supporting the potential that the GHQ‐12 is measuring a unidimensional construct that is broadly representative of mental health. While the recent meta‐analyses (Gnambs & Staufenbiel, Citation2018) were large and comprehensive, they are nonetheless limited by the conventions of the published data, namely, the vast majority of studies of GHQ‐12 with the combination of negatively and positively worded items, potentially introducing artefactual results in terms of structure. Some authors have conducted studies specifically designed to test this effect by rewording items prior to data collection (Greenberger, Chen, Dmitrieva, & Farruggia, Citation2003). Findings indicated that once all items of the scale of interest were written in a consistent direction, a single‐factor scale emerged rather than the two‐factor structure previously found by some researchers, suggesting that the two‐factor structure was an artefact of the positive and negative item wording; however, this pattern was not observed across respondents with differing verbal ability levels, indicating that it may not hold true in children. One study by Wang and Lin (Citation2011) administered three versions of the GHQ‐12 to adults; the original version, a version with all items worded positively, and a version with all items worded negatively. After controlling for wording effects, the GHQ‐12 was deemed to have a unidimensional structure. Further studies in children comparing versions of the GHQ‐12 with the wording bias removed, alongside the current commonly used version would be advantageous in disentangling these issues. In addition, psychometric approaches are evolving, and at the same time, computers are allowing increasingly more sophisticated analytic techniques, that are becoming more widely accessible for researchers. Bifactor modelling approaches, in combination with different ways of quantifying consistency (such as omega as an alternative to Cronbach's alpha), are (re)emerging in recent literature as informative techniques for understanding factor structure (Dunn, Baguley, & Brunsden, Citation2014; Gignac, Citation2014; McNeish, 2018; Reise, Citation2012). Embedding these techniques in further research is of clear benefit.

The sampling approach of the present study must be taken into account when assessing the representativeness of the results. Although this was not a random sample, the present study utilised a very large convenience sample, with children enrolled in 634 different schools and living in 3,479 suburbs in all states and territories of Australia. Although the majority of schools were located in Victoria, there was a large spread of students from differing socio‐economic status areas in this sample. There was also minimal missing data due to the survey being completed during class time. Therefore, the results of this study are likely to be broadly generalisable to children throughout Australia. One limitation to note is that due to the survey being administered at some schools over several years, there is the possibility that the same individuals completed the survey over multiple years. Although schools were controlled for in the mixed model ANOVA, it is not possible to determine whether the same individuals repeated the survey on multiple occasions.

Taken together, findings from this study reinforce conclusions made by previous authors (e.g., Tait et al. (Citation2003); French and Tait (Citation2004)), that the GHQ‐12 is suitable for assessing psychological symptoms in Australian adolescents. Our results also support the use of this scale for the measurement of mental well‐being symptoms in children and establish new norms from 7–19 years of age. Whether ultimately considered as a two‐factor instrument or a unidimensional construct, overall psychometric properties including sensitivity, suggest that the GHQ‐12 provides a robust indicator of short‐term mental state in children and adolescents. It is easy to administer and does not appear to cause distress to primary school‐aged children. Therefore, the GHQ‐12 may be a suitable tool that could be easily implemented by clinicians into primary and secondary school curricula as part of early screening for psychological problems in individuals. The implementation of the GHQ‐12 may also provide a critical point for early intervention which may aid in fostering resilient mindsets in children and reducing the high rates of psychological distress in later adolescence.

raup_a_12098928_sm0001.docx

Download MS Word (39.4 MB)ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the schools who were involved in data collection. They would also like to acknowledge Luke Thorburn for his assistance with data collation and Emma Ravet for her contribution to the literature search. The authors would also like to gratefully acknowledge the time and effort of the reviewers of this manuscript, whose suggestions contributed significantly to this work.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

Funding information Resilient Youth Australia

REFERENCES

- Angold, A., & Worthman, C. W. (1993). Puberty onset of gender differences in rates of depression: A developmental, epidemiologic and neuroendocrine perspective. Journal of Affective Disorders, 29(2), 145–158.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2016). Socio‐Economic Indexes for Australia (SEIFA). Time series spreadsheet, cat. no. 2033.0.55.001, viewed May 2018.

- Baksheev, G. N., Robinson, J., Cosgrave, E. M., Baker, K., & Yung, A. R. (2011). Validity of the 12‐item general health questionnaire (GHQ‐12) in detecting depressive and anxiety disorders among high school students. Psychiatry Research, 187(1), 291–296.

- Bockting, W. O., Miner, M. H., Swinburne romine, R. E., Hamilton, A., & Coleman, E. (2013). Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 943–951.

- Çokluk, Ö., & Koçak, D. (2016). Using Horn's parallel analysis method in exploratory factor analysis for determining the number of factors. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 16(2), 537–551.

- Dunn, T. J., Baguley, T., & Brunsden, V. (2014). From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. British Journal of Psychology, 105(3), 399–412.

- French, D. J., & Tait, R. J. (2004). Measurement invariance in the general health Questionnaire‐12 in young Australian adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 13(1), 1–7.

- Gignac, G. E. (2014). On the inappropriateness of using items to calculate total scale score reliability via coefficient alpha for multidimensional scales. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 30, 130–139.

- Gnambs, T., & Staufenbiel, T. (2018). The structure of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ‐12): Two meta‐analytic factor analyses. Health Psychology Review, 12(2), 179–194.

- Goldberg, D. P., Gater, R., Sartorius, N., Ustun, T. B., Piccinelli, M., Gureje, O., & Rutter, C. (1997). The validity of two versions of the GHQ‐12 in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychological Medicine, 27(1), 191–197.

- Goldberg, D. P., Mcdowell, I., & Newell, C. (1972). General health questionnaire (GHQ), 12 item version, 20 item version, 30 item version, 60 item version [GHQ12, GHQ20, GHQ30, GHQ60]. In Measuring health: A guide to rating scales and questionnaire (pp. 225–236). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Graetz, B. (1991). Multidimensional properties of the General Health Questionnaire. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 26(3), 132–138.

- Greenberger, E., Chen, C., Dmitrieva, J., & Farruggia, S. P. (2003). Item‐wording and the dimensionality of the Rosenberg self‐esteem scale: Do they matter? Personality and Individual Differences, 35(6), 1241–1254.

- Hankin, B. L., Abramson, L. Y., Moffitt, T. E., Silva, P. A., Mcgee, R., & Angell, K. E. (1998). Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10‐year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107(1), 128–140.

- Hennessy, E., Swords, L., & Heary, C. (2008). Children's understanding of psychological problems displayed by their peers: A review of the literature. Child: Care, Health and Development, 34(1), 4–9.

- Hu, Y., Stewart‐brown, S., Twigg, L., & Weich, S. (2007). Can the 12‐item general health questionnaire be used to measure positive mental health? Psychological Medicine, 37(7), 1005–1013.

- Mann, R. E., Paglia‐boak, A., Adlaf, E. M., Beitchman, J., Wolfe, D., Wekerle, C., … Rehm, J. (2011). Estimating the prevalence of anxiety and mood disorders in an adolescent general population: An evaluation of the GHQ12. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 9(4), 410–420.

- Marsh, H. W. (1986). Negative item bias in ratings scales for preadolescent children: A cognitive‐developmental phenomenon. Developmental Psychology, 22(1), 37–49.

- Mcneish, D. (2018). Thanks coefficient alpha, we'll take it from here. Psychological Methods, 23(3), 412–433. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000144

- Nunnally, J. C. (1967). Psychometric theory. New York, NY: McGraw‐Hill.

- Padrón, A., Galán, I., Durbán, M., Gandarillas, A., & Rodríguez‐artalejo, F. (2012). Confirmatory factor analysis of the general health questionnaire (GHQ‐12) in Spanish adolescents. Quality of Life Research, 21(7), 1291–1298.

- Politi, P., Piccinelli, M., & Wilkinson, G. (1994). Reliability, validity and factor structure of the 12‐item general health questionnaire among young males in Italy. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 90(6), 432–437.

- Reise, S. P. (2012). The rediscovery of bifactor measurement models. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 47(5), 667–696.

- Scales, P. C., & Leffert, N. (1999). Developmental assets: A synthesis of the scientific research on adolescent development. Minneapolis, MN: Search Institute.

- Schrnitz, N., Kruse, J., & Tress, W. (1999). Psychometric properties of the general health questionnaire (GHQ‐12) in a German primary care sample. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 100(6), 462–468.

- Smith, A. B., Oluboyede, Y., West, R., Hewison, J., & House, A. O. (2013). The factor structure of the GHQ‐12: The interaction between item phrasing, variance and levels of distress. Quality of Life Research, 22(1), 145–152.

- Snyder, C. R., Hoza, B., Pelham, W. E., Rapoff, M., Ware, L., Danovsky, M., … Stahl, K. J. (1997). The development and validation of the Children's Hope scale. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 22(3), 399–421.

- Suzuki, H., Kaneita, Y., Osaki, Y., Minowa, M., Kanda, H., Suzuki, K., … Ohida, T. (2011). Clarification of the factor structure of the 12‐item general health questionnaire among Japanese adolescents and associated sleep status. Psychiatry Research, 188(1), 138–146.

- Tait, R. J., French, D. J., & Hulse, G. K. (2003). Validity and psychometric properties of the general health Questionnaire‐12 in young Australian adolescents. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 37(3), 374–381.

- Van dongen, H. P., Olofsen, E., Dinges, D. F., & Maislin, G. (2004). Mixed‐model regression analysis and dealing with interindividual differences. Methods in Enzymology, 384, 139–171.

- Wang, L., & Lin, W. (2011). Wording effects and the dimensionality of the general health questionnaire (GHQ‐12). Personality and Individual Differences, 50(7), 1056–1061.