Abstract

Objective

The default assumption among most psychologists is that personality varies along a set of underlying dimensions, but belief in the existence of discrete personality types persists in some quarters. Taxometric methods were developed to adjudicate between these alternative dimensional and typological models of the latent structure of individual differences. The aim of the present review was to assess the taxometric evidence for the existence of personality types.

Method

A comprehensive review yielded 102 articles reporting 194 taxometric findings for a wide assortment of personality attributes.

Results

Structural conclusions differed strikingly as a function of methodology. Primarily older studies that did not assess the fit of observed data to simulated dimensional and typological comparison data drew typological conclusions in 65.2% (60/92) of findings. Primarily newer studies employing simulated comparison data supported the typological model in only 3.9% (4/102) of findings, and these findings were largely in the domain of sexual orientation rather than personality in the traditional sense.

Conclusions

In view of strong Monte Carlo evidence for the validity of the simulated comparison data method, it is highly likely that personality types are exceedingly scarce or non‐existent, and that many early taxometric research findings claiming evidence for such types are spurious.

What is already known about the topic

Whether personality attributes are best understood as dimensions or categories (types) is the subject of some debate.

Taxometric research methods aim to test between dimensional and categorical models of individual differences.

Previous taxometric research has supported the existence of some personality types.

What this topic adds

This review of 102 taxometric studies of personality finds little replicated evidence for personality types.

Many early studies that supported the existence of types had a methodological bias toward that conclusion.

It is likely that personality types are very scarce or non‐existent.

INTRODUCTION

Personality psychologists tend to assume by default that individual differences have a dimensional latent structure. People are understood to differ by degree along a set of continuous dimensions, and this understanding supports taken‐for‐granted practices such as quantitative personality assessment and the use of dimension‐generating statistical procedures such as factor analysis. The idea that personality might be captured by a few personality types—discrete categories to which people belong in an either/or fashion—is commonly dismissed as a crude figment of popular psychology.

In an important theoretical article, Meehl (Citation1992) demonstrated that our contemporary assumptions about the latent structure of personality were not uniformly shared by our forebears. The existence of personality types was proposed by Jung (Citation1971) in his work on psychological type, by Sheldon (Citation1942) in his work on somatotypes and their associated temperaments, in the psychoanalytic theory of character types, and in accounts of Type A personality. More recently, a typological view of abnormal personality has been implicit in the categorical diagnosis of personality disorders within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, a matter of ongoing dispute (Trull & Durrett, Citation2005). Meehl argued that we should not dismiss the possibility that some personality types exist, and he articulated several causal mechanisms, including major gene effects and environmental moulding, through which they might arise (see also Asendorpf (Citation2002)).

Meehl did not merely raise the existence of personality types as an abstract possibility. He also conjectured the existence of one type and developed a set of quantitative methods for detecting latent categories, which he dubbed “taxa” (singular “taxon”). In early work (Meehl, Citation1962), he proposed that schizotypal personality was typological or “taxonic,” characterising a small latent class of people who were at elevated risk of developing schizophrenia, and in later work (Meehl, Citation1995) he laid out a family of “taxometric” procedures to detect such a taxa. These mathematically independent procedures, most of which produce graphical plots of patterns of covariation among indicators of the proposed latent variable, generate different patterns when the latent variable is taxonic or dimensional, and use consistency among multiple procedures rather than statistical significance testing to draw structural inferences (see Ruscio, Haslam, & Ruscio (Citation2006) for an overview).

The first taxometric study of personality was published by Golden and Meehl (Citation1979), who supported the existence of Meehl's conjectured “schizoid taxon.” Several influential taxometric studies followed each finding evidence of another personality type. Gangestad and Snyder (Citation1985) found evidence that self‐monitoring was typological, as did Strube (Citation1989) for Type A personality, Harris, Rice, and Quinsey (Citation1994) for psychopathy, and Oakman and Woody (Citation1996) for hypnotic susceptibility. During this early period of taxometric research, the taxonic status of schizotypy was also replicated by Erlenmeyer‐Kimling, Golden, and Cornblatt (Citation1989), Lenzenweger and Korfine (Citation1992), and Tyrka et al. (Citation1995). Of the first 10 taxometric studies of personality, nine supported the existence of a personality type, dramatically challenging the prior assumption that personality variation is invariably dimensional.

Taxometric methods have subsequently become widely used in personality and clinical psychology. A review of all studies published or “in press” in early 2011 (Haslam, Holland, & Kuppens, Citation2012) found 177 articles that reported a total of 311 distinct findings about specific variables which were distributed widely across the fields of psychopathology, personality, other individual differences, and several other domains. The review showed that a large minority (38.9%) of taxometric findings were reported as supporting a taxonic latent structure for the variable of interest. This finding, although aggregated across many dissimilar research fields, raises the plausibility of latent classes existing in the broad domain of individual differences, with the strongest evidence found in studies of schizotypy, autism, and substance use.

However, this conclusion about the high prevalence of taxonic findings was qualified by a very strong methodological effect. Earlier studies drew conclusions about latent structure primarily from visual inspection of the graphical plots generated by taxometric procedures. Many later studies added a methodological refinement developed by Ruscio, Ruscio, and Meron (Citation2007), which compared the observed taxometric plots to parallel analyses of simulated comparison datasets that matched the parameters of the observed data (e.g., variability, skew, intercorrelations) but were either generated by a taxonic or a dimensional latent structure. This simulated comparison data procedure enabled a direct comparison of the fit of the analyses of the observed data to those of the respective simulations, captured by a Comparison Curve Fit Index (CCFI). A CCFI value of 0.50 represented equally good fit of the two latent structures, values <0.45 favoured dimensional structure, values >0.55 favoured taxonic structure, and values between 0.45 and 0.55 were ambiguous. Extensive Monte Carlo research (Ruscio & Kaczetow, Citation2009; Ruscio et al., Citation2007; Ruscio, Walters, Marcus, & Kaczetow, Citation2010), examining more than 200,000 simulated datasets varying on parameters commonly encountered in psychological research settings, established that the simulated comparison data method was highly accurate in identifying dimensional versus taxonic datasets with no bias in favour of either alternative. The method was especially accurate when CCFI values were averaged across multiple taxometric procedures and when conclusions were not drawn if these values fell within the ambiguity band. For example, Ruscio et al. (Citation2010) found that mean CCFI yielded unambiguous (<0.45 or >0.55) values in 94.8% of 100,000 datasets, half of which were dimensional and half taxonic, and it achieved 99.4% accuracy in distinguishing between dimensional and taxonic sets.

Haslam et al.'s (Citation2012) review revealed that studies employing the simulated comparison data procedure and the CCFI produced a markedly lower rate of taxonic findings (16.2%) than studies that did not employ it (56.6%). In view of the Monte Carlo evidence that the simulation procedure is highly accurate in identifying latent structure, that studies which did not employ it tended to be methodologically weaker in other respects, and that visual inspection of taxometric plots may be vulnerable to biases that favour taxonic inferences, Haslam et al. (Citation2012) speculated that the rate of taxonic findings had been over‐estimated in previous taxometric research. In particular, they proposed that some taxonic findings obtained in influential early studies which did not employ simulated comparison data were likely to be spurious. If this were the case, early taxometric research may have mistakenly challenged the prior assumption that personality is latently dimensional and personality types are rare or non‐existent.

The 2012 review provided a broad‐brush overview of the state of taxometric research as it stood in 2011 but it has two significant limitations. First, its inclusiveness led it to incorporate studies of a very disparate collection of variables, making it difficult to extract meaningful conclusions about the distribution of dimensions and types in specific domains. Second, it necessarily omitted the large quantity of research conducted since 2011, much of which has followed up some of the ambiguities identified by the original review. Consequently, the present study was intended to provide an updated review of taxometric research focused narrowly on the domain of personality. Our objectives were: (a) to survey all published taxometric research on personality characteristics, (b) to draw conclusions about the prevalence of typological variables in the personality domain, and (c) to identify regions of the personality domain that are most likely to contain types, if these exist.

METHOD

Study sample

A thorough literature search was conducted in three parts. First, all 177 taxometric articles identified in the previous review (Haslam et al., Citation2012), itself based on a comprehensive search using multiple databases for all peer‐reviewed journal articles published or in press by April 2011 and on a prior review (Haslam, Citation2003), were retained. Second, searches with the same search terms (taxometric*, taxon*, MAXCOV, MAMBAC, MAXEIG) were conducted for the period 2011 to July 1, 2018, again using multiple databases (Google, Google Scholar, PsycInfo, Web of Science), yielding 87 new articles. Third, from the combined set of 264 taxometric articles we extracted those that conducted at least one taxometric analysis of a personality characteristic, defined in an inclusive manner. Articles were removed from the set if the only variable(s) they examined taxometrically: (a) were not primarily psychological (e.g., handedness, tardive dyskinesia), (b) did not have the individual person as the unit of analysis (e.g., relationship types, emotion episodes), (c) were mental disorders or symptoms of disorders except personality disorders (e.g., autism, cannabis dependence, mania), or (d) were specific behaviours or emotional responses rather than broader dispositions (e.g., fear of pain, internet gambling, dietary restraint, malingering). These exclusion criteria led to the retention of several studies of individual difference variables that are in the broad personality domain but are not prototypical traits, such as sexual orientation, alexithymia, attachment styles, questionnaire response biases such as impression management, and depression‐proneness. After the application of the exclusion criteria, 102 articles remained, 74 of which had been included in Haslam et al. (Citation2012).

Definition of taxometric findings

After defining the article sample, we extracted individual taxometric findings from them. As in Haslam et al. (Citation2012), a finding was defined as a conclusion about the latent structure of a single construct (i.e., taxonic, dimensional, or ambiguous) based on at least one taxometric procedure in a single sample. An article could yield multiple findings if it examined the structure of one construct in two or more distinct samples, two or more distinct constructs in a single sample, or multiple constructs in multiple samples. To avoid redundancy or non‐independence of findings within single articles, if taxometric analyses were reported both for a whole sample and for component subsamples, only the whole‐sample analysis was recorded. Similarly, if analyses of a construct in one sample were run with one set of indicators of the construct and also with a subset of those indicators, only the analysis of the whole set of indicators was recorded. Following this definition, a total of 194 distinct findings were recorded from the 102 articles (M = 1.90).

Coding

All 102 articles were coded by the author, with original codes of the 74 articles included in the Haslam et al. (Citation2012) review retained. The publication date for each article was recorded, and after individuating the findings in each study, the following information was coded for each one: sample size, sample source, construct examined, taxometric procedures employed (coded as MAXCOV, MAMBAC, MAXEIG, L‐Mode, MAXSLOPE and other), and use or non‐use of simulated comparison data. For studies employing simulated comparison data, CCFI values were recorded for each finding. Findings themselves were recorded in two ways: for studies that did not yield CCFI values, the researchers' own conclusions (coded taxonic or non‐taxonic) were recorded, and for studies that did yield them, the mean CCFI value across all taxometric procedures generating CCFI values was recorded.

Data analysis

The aim of the present study was primarily to describe the distribution of taxometric research findings in the personality domain rather than to conduct complex analyses of their determinants. Unlike a meta‐analysis, for example, the outcome of interest is a binary decision (taxonic vs. non‐taxonic) rather than an effect size and the field of interest is broad and disparate (personality as a whole) rather than a specific effect. Consequently, data analysis is primarily descriptive. Findings are treated as the unit of analysis in most of the descriptive analyses.

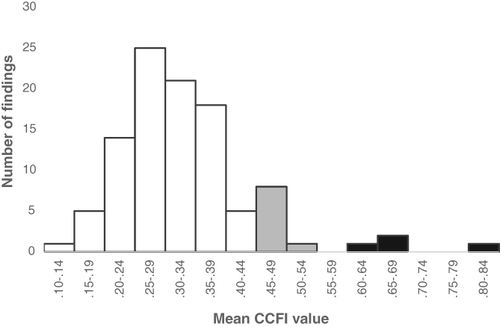

RESULTS

The mean publication year for the 102 articles was 2006.8 (range: 1979–2018). For the 194 findings, the mean sample size was 3,123.9. Samples were drawn from undergraduates (77; 39.7%), community members (73; 37.6%), and clinical or forensic settings (52; 26.8%)—percentages add to over 100 because some samples were composites—and 21 (10.8%) were composed of children or adolescents. The average finding was based on 2.36 distinct taxometric procedures, including MAMBAC (144; 74.2%), MAXCOV (122; 62.9%), L‐Mode (97; 50.0%), MAXEIG (86; 44.3%), and MAXSLOPE (4; 2.1%). One hundred and two findings (52.6%) employed simulated comparison data and the CCFI, with a mean average CCFI value of 0.331.

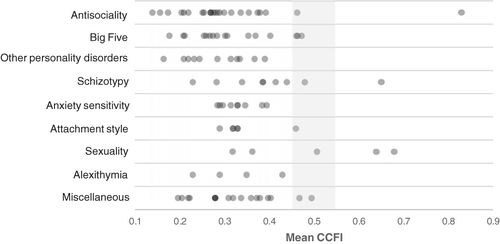

Prior to examining the distribution of taxometric findings, the diverse assortment of constructs represented in the 194 findings was grouped into 12 sets. This grouping was done in a way that combined studies of similar constructs, represented major foci of existing taxometric research, and was relatively economical (i.e., only sets with four or more findings were assigned a grouping). Table presents a summary of the composition of these sets in descending order of number of findings included. Studies of antisocial and psychopathic tendencies on the one hand, and varieties of schizotypal personality on the other, have been the focus of a substantial proportion of taxometric research on personality. Other forms of abnormal personality (“other personality disorders [PDs]”) and vulnerability factors for mental health problems (e.g., “anxiety sensitivity”) have received some attention, and a few sets—Big Five traits, Jungian types—include relatively numerous findings from relatively few articles. The “miscellaneous” set contains many findings from a diverse collection of dispositions. In total, taxometric research has examined the latent structure of a very extensive sampling of personality characteristics, enabling a wide‐angle scan for the existence of personality types.

Table 1. Classification of sets of findings based on similarity of constructs

Table summarises the distribution of structural findings across the 12 sets of personality characteristics. Overall, 60 of the 92 findings (65.2%) that did not employ simulated comparison data and the CCFI were judged taxonic by the researchers who generated them, whereas only 4 of the 102 findings (3.9%) that employed this method yielded unambiguously taxonic conclusions (i.e., mean CCFI > 0.55). This difference is striking, χ(1) = 82.21, p < 0.001, but it must be noted that use of simulated comparison data is not evenly distributed across the 12 sets of findings, χ(11) = 79.65, p < 0.001. It is relatively rare in analyses of schizotypy and relatively common in analyses of antisociality and Big Five traits. The huge discrepancy in rates of taxonic findings between studies employing and not employing simulated comparison data might therefore partly reflect differences in the constructs being examined in the respective studies. Nevertheless, the discrepancy remains substantial even within specific sets of latent variables. Table shows that schizotypy (29 of 33), anxiety sensitivity (11 of 11), and antisociality (4 of 4) yield disproportionately taxonic conclusions in non‐simulation studies, but much lower rates of taxonic conclusions in studies employing the CCFI: schizotypy (1 of 9; χ(1) = 20.42, p < 0.001), anxiety sensitivity (0 of 9; χ(1) = 20.00, p < 0.001), and antisociality (1 of 24; χ(1) = 21.47, p < 0.001).

Table 2. Distribution of taxometric findings across construct sets as a function of use or non‐use of data simulations

Figures 1 and 2 display the rarity of taxonic conclusions among the 102 findings of analyses that used the simulated comparison data method. (Figure 2 omits the hypnotic susceptibility, Jungian types, and response biases construct sets because none of their findings were based on this method.) Figure 1 shows that only four findings have mean CCFI values that are unambiguously taxonic, and even among the nine findings in the ambiguity band (0.45–0.55), eight fall on the non‐taxonic side (<0.50) and are probably best seen as belonging to the right tail of the distribution of non‐taxonic findings. Figure 2 shows that for almost every set of constructs, the majority of mean CCFI values favour dimensional conclusions. The one exception is the sexuality set, in which two findings are non‐taxonic, one is ambiguous (mean CCFI = 0.507) and two are taxonic. These two taxonic findings, both reported in Norris et al. (Citation2015), relate to male and female homosexuality. Sexual orientation is rarely conceptualised as a personality variable, and in the absence of these findings, only two other findings from the remaining 100 findings based on simulated comparison data—on antisocial personality disorder (Kerridge et al., Citation2014a, Citation2014b) and schizotypy (Everett & Linscott, Citation2015)—favour the existence of a personality type. These two findings deviate from and are outweighed by other studies of the same characteristics: 22 antisociality findings and 7 schizotypy findings yield CCFI values in the non‐taxonic range (<0.45).

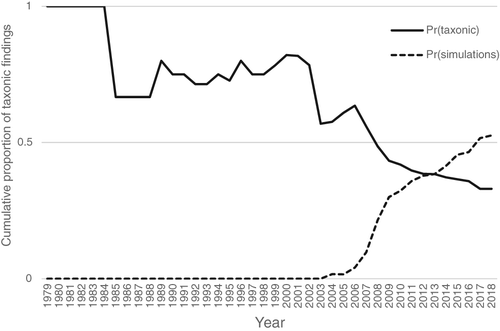

Figure 3 provides an overview of the evolving conclusions of taxometric research on personality over the 40-years since Golden and Meehl's (Citation1979) first study. It demonstrates that the cumulative proportion of research findings identified as taxonic has steadily declined from a large majority in the 1980s to a modest minority (33.3%) in 2018. The cumulative proportion of studies employing simulated comparison data and the CCFI shows the opposite pattern, rising steeply in the past decade so that it has now been used in the majority of published findings. The figure identifies 2007 as a pivotal year in taxometric personality research. Up to and including that year, 55.9% of taxometric research findings were taxonic and 9.7% of findings had employed simulated comparison data. After that year, 11.7% of findings were taxonic and 92.1% employed such data. The increased use of this almost universally adopted methodological advance has coincided with findings supportive of personality types becoming extremely scarce.

DISCUSSION

The present review of taxometric research on personality is broadly consistent with the earlier review of taxometric research, which included studies of mental disorders and other variables outside the personality domain (Haslam et al., Citation2012). Both reviews indicated that taxometric research has historically supported the existence of taxa in a relatively high proportion of studies. However, both reviews also established that this proportion has dropped precipitously in recent years, identifying the use of simulated comparison data as the main cause of this decline. Both reviews conclude that taxonic latent variables are likely to be substantially rarer than early taxometric research suggested. If anything, the present review's conclusions are starker than those of Haslam et al. (Citation2012). The earlier review found that studies employing and not employing simulated comparison data supported the taxonic model in 56.6 and 14.0% of findings, respectively, whereas the present review yields figures of 65.2 and 3.9%. Even recognising that the two subsets of studies in the present review did not examine an identical mix of personality attributes, it is remarkable that one subset finds evidence of types at more than 16 times the rate of the other, which approximates zero.

Confronted with this evidence that the findings of taxometric studies are crucially dependent on whether a specific methodological practice is employed, three conclusions are logically possible. We could conclude that the simulated comparison data method is reliable, infer that studies which do not employ it are biased toward taxonic findings, and discount those findings as a result. Alternatively, we could conclude that the simulated comparison data method is unreliable, infer that studies employing it are biased against taxonic findings, and discount these findings. Finally, we could conclude that both methods may be unreliable, perhaps suffering from biases that operate in different directions. At the present time, the first of these possible conclusions is significantly more plausible than the others.

For a start, substantial Monte Carlo research (Ruscio & Kaczetow, Citation2009; Ruscio et al., Citation2007, Citation2010) has demonstrated that the simulated comparison data method has no systematic bias for or against taxonic conclusions under an assortment of realistic data conditions. Second, and relatedly, it has been shown that latently dimensional data can generate taxometric plots that look taxonic in the presence of indicator skew (Cleland & Haslam, Citation1996). Third, the exclusive reliance of taxometric research on visual inspection of graphical plots prior to the adoption of the CCFI leaves this research vulnerable to subjectivity, bias, and researcher degrees of freedom where plotting and interpretation decisions are concerned. For these reasons, it is far more probable that studies which did not employ simulated comparison data have over‐estimated the prevalence of personality types than that studies that did employ them have under‐estimated it. The true prevalence of typological findings in the personality domain is therefore likely to be much closer to 3.9% than to 65.2%.

This striking aggregate difference in support for the existence of personality types from studies employing different quantitative methodologies is reflected in the steep decline in cumulative support for personality types since the early days of taxometric research. It is also reflected in miniature for almost every personality attribute that was claimed to be typological at that time. Gangestad and Snyder's (Citation1985) taxonic finding for self‐monitoring was overturned by Wilmot's (Citation2015) stronger studies using simulated comparison data. Strube's (Citation1989) study of Type A personality has recently met the same fate (Wilmot, Haslam, Tian, & Ones, Citationin press). Harris et al.'s (Citation1994) taxonic finding for psychopathy has been followed by 24 findings using simulated comparison data, 23 of which fit a dimensional model better than a taxonic alternative. Numerous early studies indicating that anxiety sensitivity was typological (e.g., Bernstein, Zvolensky, Weems, Stickle, & Leen‐Feldner, Citation2005) were called into serious question by an uninterrupted run of 11 dimensional findings from simulation‐based studies.

Schizotypy is the one exception to this pattern of early typological findings that have since been rebutted. After 40-years of taxometric research that was inaugurated by Golden and Meehl (Citation1979), and 42 distinct findings from 22 articles, schizotypy's latent structure remains stubbornly unresolved. Although 71.4% (30/42) of findings support the existence of a taxon, all but one of these findings (i.e., 29/33) derives from studies that did not employ parallel analyses of simulated comparison data. Findings from studies that did employ this method were unambiguously supportive of a taxon in only one of nine findings, with one finding ambiguous but more consistent with dimensionality (mean CCFI < 0.5). The respective rates of taxonic findings from the two sets of studies are therefore 87.9 and 11.1% (mean = 49.5%). In sum, the aggregated evidence from taxometric research appears to favour a taxonic conclusion for schizotypy largely because most researchers who have examined it did not adopt a methodological tool that challenges that conclusion, either because it had yet to be widely used (25/33 of the findings in question precede 2008) or because they were sceptical of it.

A diplomatic reading of the accumulated taxometric evidence on the status of schizotypy might conclude that its latent structure remains moot because neither taxonic nor dimensional structures have been consistently supported. However, a less equivocal reading may be justified for several reasons. First, Monte Carlo studies strongly support the accuracy and lack of bias of taxometric inferences when simulated comparison data are employed. The much higher rate of taxonic findings obtained for schizotypy when this method is not employed must therefore reflect methodological bias. Second, the findings of the present review indicate that the base rate of taxonic findings in the personality domain is very low (3.9% of findings using simulated comparison data across a wide assortment of variables, or 2.0% if findings for male and female sexual orientation (Norris et al., Citation2015) are excluded as falling outside the personality domain as normally understood). From a Bayesian standpoint, if personality types are as rare as this base‐rate suggests, then schizotypy would have to be a very surprising exception, and unusually persuasive evidence would be needed to override the high prior probability of it being dimensional. Third, the idea that personality is overwhelmingly dimensional is consistent with the growing evidence that traits reflect the summation of a very large number of influences of small effect (e.g., Terracciano et al., Citation2010).

These three reasons to question research claiming that schizotypy is taxonic represent generic critiques but concerns that are specific to schizotypy research can also be raised. One rarely noted concern is that the specification of the supposed taxon varies widely across studies. In some cases, in accordance with Meehl's (Citation1962) original theoretical claim, a singular taxon is sought and found. In others, schizotypy is fractionated into several components (e.g., perceptual aberration, magical ideation, social anhedonia, and physical anhedonia; or positive and negative schizotypy) and each is found to have its own taxon. The fact that studies which do not employ simulated comparison data consistently obtain taxonic findings across these diverse ways of defining and assessing schizotypy calls into question what the taxon or taxa might be, and whether these studies might be drawing taxonic conclusions too liberally. A recent case in point is Morton et al. (Citation2017), which found evidence of three partially overlapping “disorganised,” “interpersonal,” and “cognitive‐perceptual” schizotypal taxa in the same sample, such that some individuals belonged to one, two, or all three taxa. Another concern is the wide discrepancy across studies in the supposed prevalence of schizotypal taxa in normal samples, which Meehl predicted to be about 10%. Estimates have ranged from less than 5% to more than 30% (e.g., 32% of Morton et al.'s university student participants belonged to at least one schizotypal taxon). The failure of such prevalence estimates to converge on a plausible value is compatible with the alternative view that no latent category exists.

In conclusion, the present review suggests that typological variables are extremely scarce in the personality domain, and possibly non‐existent. A substantial body of taxometric research has surveyed a large and diverse sample of personality characteristics but has not identified a single characteristic that generates replicable typological findings when a validated quantitative methodology is employed. This research methodology, which has demonstrated great accuracy in differentiating typological and dimensional data, has not only failed to locate personality types, a negative result, but has also consistently obtained positive support for dimensional models. By implication, the default assumption among psychologists that personality is latently dimensional may be correct, and the challenge to that assumption made by early taxometric researchers may have been instructive but ultimately misplaced.

REFERENCES

- *Ahmed, A. O., Green, B. A., Buckley, P. F., & Mcfarland, M. E. (2012). Taxometric analyses of paranoid and schizoid personality disorders. Psychiatry Research, 196, 123–132.

- *Ahmed, A. O., Green, B. A., Goodrum, N. M., Doane, N. J., Birgenheir, D., & Buckley, P. F. (2013). Does a latent class underlie schizotypal personality disorder? Implications for schizophrenia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122, 475–491.

- *Arnau, R. C., Green, B. A., Rosen, D. H., Gleaves, D. H., & Melancon, J. G. (2003). Are Jungian preferences really categorical? An empirical investigation using taxometric analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 34, 233–251.

- *Arntz, A., Bernstein, D., Gielen, D., van Nieuwenhuijzen, M., Penders, K., Haslam, N., & Ruscio, J. (2009). Taxometric evidence for the dimensional structure of cluster‐C, paranoid and borderline personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders, 23, 606–628.

- Asendorpf, J. (2002). Editorial: The puzzle of personality types. European Journal of Personality, 16, S1–S5.

- *Asmundson, G. J. G., Weeks, J. W., Carleton, R. N., Thibodeau, M. A., & Fetzner, M. G. (2011). Revisiting the latent structure of the anxiety sensitivity construct: More evidence of dimensionality. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25, 138–147.

- *Beller, J., & Bosse, S. (2017). Machiavellianism has a dimensional latent structure: Results from taxometric analyses. Personality and Individual Differences, 113, 57–62.

- *Bernstein, A., Zvolensky, M. J., Feldner, M. T., Lewis, S. F., & Leen‐feldner, E. W. (2005). Anxiety sensitivity taxonicity: A concurrent test of cognitive vulnerability for post‐traumatic stress symptomatology among young adults. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 34, 229–241.

- *Bernstein, A., Zvolensky, M. J., Kotov, R., Arrindell, W. A., Taylor, S., Sandin, B., … Schmidt, N. B. (2006). Taxonicity of anxiety sensitivity: A multi‐national analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 20, 1–22.

- *Bernstein, A., Zvolensky, M. J., Norton, P. J., Schmidt, N. B., Taylor, S., Forsyth, J. P., … Cox, B. (2007). Taxometric and factor analytic models of anxiety sensitivity: Integrating approaches to latent structural research. Psychological Assessment, 19, 74–87.

- *Bernstein, A., Zvolensky, M. J., Stewart, S., & Comeau, N. (2007). Taxometric and factor analytic models of anxiety sensitivity among youth: Exploring the latent structure of anxiety psychopathology vulnerability. Behavior Therapy, 38, 269–283.

- *Bernstein, A., Zvolensky, M. J., Stewart, S. H., Comeau, M. N., & Leen‐feldner, E. W. (2006). Anxiety sensitivity taxonicity across gender among youth. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 679–698.

- *Bernstein, A., Zvolensky, M. J., Weems, C., Stickle, T., & Leen‐feldner, E. W. (2005). Taxonicity of anxiety sensitivity: An empirical test among youth. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43, 1131–1155.

- *Blanchard, J. J., Gangestad, S. W., Brown, S. A., & Horan, W. P. (2000). Hedonic capacity and schizotypy revisited: A taxometric analysis of social anhedonia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 87–95.

- *Bove, E. A., & Epifani, A. (2012). From schizotypal personality to schizotypal dimensions: A two‐step taxometric study. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 9, 111–122.

- *Broman‐fulks, J. J., Deacon, B. J., Olatunji, B. O., Bondy, C. L., Abramowitz, J. S., & Tolin, D. F. (2010). Categorical or dimensional: A reanalysis of the anxiety sensitivity. Behavior Therapy, 41, 154–171.

- *Broman‐fulks, J. J., Green, B. A., Berman, M. E., Olatunji, B. O., Arnau, R. C., Deacon, B. J., & Sawchuk, C. N. (2008). The latent structure of anxiety sensitivity—Revisited. Assessment, 15, 188–203.

- *Broman‐fulks, J. J., Hill, R. W., & Green, B. A. (2008). Is perfectionism categorical or dimensional? A taxometric analysis. Journal of Personality Assessment, 90, 481–490.

- *Carleton, R. N., Weeks, J. W., Howell, A. N., Asmundson, G. J., Antony, M. M., & Mccabe, R. E. (2012). Assessing the latent structure of the intolerance of uncertainty construct: An initial taxometric analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26, 150–157.

- Cleland, C., & Haslam, N. (1996). The robustness of taxometric analysis with skewed indicators: I. A Monte Carlo study of the MAMBAC procedure. Psychological Reports, 79, 243–248.

- *Edens, J. F., Marcus, D. K., Lilienfeld, S. O., & Poythress, N. J. (2006). Psychopathic, not psychopath: Taxometric evidence for the dimensional structure of psychopathy. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115, 131–144.

- *Edens, J. F., Marcus, D. K., & Morey, L. C. (2009). Paranoid personality has a dimensional latent structure: Taxometric analyses of community and clinical samples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118, 545–553.

- *Edens, J. F., Marcus, D. K., & Ruiz, M. A. (2008). Taxometric analyses of borderline personality features in a large‐scale male and female offender sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117, 705–711.

- *Edens, J. F., Marcus, D. K., & Vaughn, M. G. (2011). Exploring the taxometric status of psychopathy among youthful offenders: Is there a juvenile psychopath taxon? Law and Human Behavior, 35, 13–24.

- *Eichner, K. V., Kwon, P., & Marcus, D. K. (2014). Optimists or optimistic? A taxometric study of optimism. Psychological Assessment, 26, 1056–1061.

- *Erlenmeyer‐kimling, L., Golden, R. R., & Cornblatt, B. A. (1989). A taxonometric analysis of cognitive and neuromotor variables in children at risk for schizophrenia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 98, 203–208.

- *Everett, K. V., & Linscott, R. J. (2015). Dimensionality vs taxonicity of schizotypy: Some new data and challenges ahead. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 41, S465–S474.

- *Falcon, R. G. (2016). Stay, stray or something in‐between? A comment on Wlodarski et al. Biology Letters, 12, 20151069.

- *Ferguson, E., Williams, L., O'connor, R., Howard, S., Hughes, B., Johnston, D. W., … O'carroll, R. E. (2009). A taxometric analysis of type‐D personality. Psychosomatic Medicine, 71, 981–986.

- *Fossati, A., Beauchaine, T. P., Grazioli, F., Carretta, I., Cortinovis, F., & Maffei, C. (2005). A latent structure analysis of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth edition, Narcissistic Personality Disorder criteria. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 46, 361–367.

- *Fossati, A., Raine, A., Borroni, S., & Maffei, C. (2007). Taxonic structure of schizotypal personality in nonclinical subjects: Issues of replicability and age consistency. Psychiatry Research, 152, 103–112.

- *Foster, J. D., & Campbell, W. K. (2007). Are there such things as “narcissists” in social psychology? A taxometric analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory. Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 1321–1332.

- *Fraley, R. C., Hudson, N. W., Heffernan, M. E., & Segal, N. (2015). Are adult attachment styles categorical or dimensional? A taxometric analysis of general and relationship‐specific attachment orientations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109, 354–368.

- *Fraley, R. C., & Roisman, G. I. (2014). Categories or dimensions? A taxometric analysis of the Adult Attachment Interview. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 79(3), 36–50.

- *Gangestad, S. W., Bailey, J. M., & Martin, N. G. (2000). Taxometric analyses of sexual orientation and gender identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 1109–1121.

- *Gangestad, S. W., & Snyder, M. (1985). "To carve nature at its joints": On the existence of discrete classes in personality. Psychological Review, 92, 317–349.

- *Gibb, B. E., Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Beevers, C. G., & Miller, I. W. (2004). Cognitive vulnerability to depression: A taxometric analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113, 81–89.

- *Golden, R. R., & Meehl, P. E. (1979). Detection of the schizoid taxon with MMPI indicators. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 88, 217–233.

- *Guay, J.‐P., Knight, R. A., Ruscio, J., & Hare, R. D. (2018). A taxometric investigation of psychopathy in women. Psychiatry Research, 261, 565–573.

- *Guay, J., Ruscio, J., Hare, R., & Knight, R. A. (2007). A taxometric study of the latent structure of psychopathy: Evidence for dimensionality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116, 701–716.

- *Harris, G. T., Rice, M. E., & Quinsey, V. L. (1994). Psychopathy as a taxon: Evidence that psychopaths are a discrete class. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62, 387–397.

- *Haslam, N. (1997). Evidence that male sexual orientation is a matter of degree. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 862–870.

- Haslam, N. (2003). Categorical versus dimensional models of mental disorder: The taxometric evidence. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 37, 696–704.

- Haslam, N., Holland, E., & Kuppens, P. (2012). Categories versus dimensions in personality and psychopathology: A quantitative review of taxometric research. Psychological Medicine, 42, 903–920.

- *Herpers, P. C. M., Klip, H., Rommelse, N. N. J., Taylor, M. J., Green, C. U., & Buitelaar, J. K. (2017). Taxometric analyses and predictive accuracy of callous‐unemotional traits regarding quality of life and behavior problems in non‐conduct disorder diagnoses. Psychiatry Research, 253, 351–359.

- *Horan, W. P., Blanchard, J. J., Gangestad, S. W., & Kwapil, T. R. (2004). The psychometric detection of schizotypy: Do putative schizotypy indicators identify the same latent class? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113, 339–357.

- Jung, C. G. (1971). Psychological types. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- *Kerridge, B. T., Saha, T. D., & Hasin, D. S. (2014a). DSM‐IV antisocial personality disorder and conduct disorder: Evidence for taxonic structures among individuals with and without substance use disorders in the general population. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 75, 496–509.

- *Kerridge, B. T., Saha, T. D., & Hasin, D. S. (2014b). DSM‐IV schizotypal personality disorder: A taxometric analysis among individuals with and without substance use disorders in the general population. Mental Health and Substance Use, 7, 446–460.

- *Korfine, L., & Lenzenweger, M. F. (1995). The taxonicity of schizotypy: A replication. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104, 26–31.

- *Lenzenweger, M. F. (1999). Deeper into the schizotypy taxon: On the robust nature of maximum covariance analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108, 182–187.

- *Lenzenweger, M. F., & Korfine, L. (1992). Confirming the latent structure and base rate of schizotypy: A taxometric analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101, 567–571.

- *Lenzenweger, M. F., Mclachlan, G., & Rubin, D. B. (2007). Resolving the latent structure of schizophrenia endophenotypes using expectation‐maximization‐based finite mixture modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116, 16–29.

- *Linscott, R. J. (2007). The latent structure and coincidence of hypohedonia and schizotypy and their validity as indices of psychometric risk for schizophrenia. Journal of Personality Disorders, 21, 225–242.

- *Linscott, R. J. (2013). The taxonicity of schizotypy: Does the same taxonic class structure emerge from analyses of different attributes of schizotypy and from fundamentally different statistical methods? Psychiatry Research, 210, 414–421.

- *Linscott, R. J., Marie, D., Arnott, K. L., & Clarke, B. L. (2006). Over‐representation of Maori New Zealanders among adolescents in a schizotypy taxon. Schizophrenia Research, 84, 289–296.

- *Linscott, R. J., Morton, S. E., & GROUP Investigators. (2018). The latent taxonicity of schizotypy in biological siblings of probands with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 44, 922–932.

- *Liu, R. T., Burke, T. A., Abramson, L. Y., & Alloy, L. B. (2018). The behavioral approach system (BAS) model of vulnerability to bipolar disorder: Evidence of a continuum in BAS sensitivity across adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46, 1333–1349.

- *Longley, S. L., Miller, S. A., Broman‐fulks, J., Calamari, J. E., Holm‐denoma, J. M., & Meyers, K. (2017). Taxometric analyses of higher‐order personality domains. Personality and Individual Differences, 108, 207–219.

- *Marcus, D. K., John, S., & Edens, J. F. (2004). A taxometric analysis of psychopathy. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113, 626–635.

- *Marcus, D. K., Lilienfeld, S. O., Edens, J. F., & Poythress, N. G. (2006). Is antisocial personality disorder continuous or categorical? A taxometric analysis. Psychological Medicine, 36, 1571–1581.

- *Marcus, D. K., Ruscio, J., Lilienfeld, S. O., & Hughes, K. T. (2008). Converging evidence for the latent structure of antisocial personality disorder—Consistency of taxometric and latent class analyses. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 35, 284–293.

- *Mattila, A. K., Keefer, K. V., Taylor, G. J., Joukamaa, M., Jula, A., Parker, J. D. A., & Bagby, R. M. (2010). Taxometric analysis of alexithymia in a general population sample from Finland. Personality and Individual Differences, 49, 216–221.

- Meehl, P. E. (1962). Schizotaxia, schizotypy, schizophrenia. American Psychologist, 17, 827–838.

- Meehl, P. E. (1992). Factors and taxa, traits and types, difference of degree and differences in kind. Journal of Personality, 60, 117–174.

- Meehl, P. E. (1995). Bootstraps taxometrics: Solving the classification problem in psychopathology. American Psychologist, 50, 266–275.

- *Meyer, T., & Keller, F. (2001). Exploring the latent structure of the perceptual aberration, magical ideation and physical anhedonia scales in a German sample—A partial replication. Journal of Personality Disorders, 15, 521–535.

- *Meyer, T., & Keller, F. (2003). Is there evidence for a latent class called “hypomanic temperament”? Journal of Affective Disorders, 75, 259–267.

- *Morton, S. E., O'hare, K. J. M., Maha, J. L. K., Nicolson, M. P., Machada, L., Topless, R., … Linscott, R. J. (2017). Testing the validity of taxonic schizotypy using genetic and environmental risk variables. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 43, 633–643.

- *Murrie, D. C., Marcus, D. K., Douglas, K. S., Lee, Z., Salekin, R. T., & Vincent, G. (2007). Youth with psychopathy features are not a discrete class: A taxometric analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48, 714–723.

- *Norris, A. L., Marcus, D. K., & Green, B. A. (2015). Homosexuality as a discrete class. Psychological Science, 26, 1843–1853.

- *Oakman, J. M., & Woody, E. Z. (1996). A taxometric analysis of hypnotic susceptibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 980–991.

- *Olatunji, B. O., & Broman‐fulks, J. J. (2007). A taxometric study of the latent structure of disgust sensitivity: Converging evidence for dimensionality. Psychological Assessment, 19, 437–448.

- *Parker, J. D. A., Keefer, K. V., Taylor, G. J., & Bagby, R. M. (2008). Latent structure of the alexithymia construct: A taxometric investigation. Psychological Assessment, 20, 385–396.

- *Rawlings, D., Williams, B., Haslam, N., & Claridge, G. (2008). Taxometric analysis supports a dimensional latent structure for schizotypy. Personality and Individual Differences, 44, 1640–1651.

- *Roisman, G. I., Fraley, R. C., & Belsky, J. (2007). A taxometric study of the adult attachment interview. Developmental Psychology, 43, 675–686.

- *Rothschild, L., Cleland, C., Haslam, N., & Zimmerman, M. (2003). Taxometric analysis of borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112, 657–666.

- Ruscio, J., Haslam, N., & Ruscio, A. M. (2006). Introduction to the taxometric method: A practical guide. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Ruscio, J., & Kaczetow, W. (2009). Differentiating categories and dimensions: Evaluating the robustness of taxometric analyses. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 44, 259–280.

- Ruscio, J., Ruscio, A. M., & Meron, M. (2007). Applying the bootstrap to taxometric analysis: Generating empirical sampling distributions to help interpret results. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42, 349–386.

- *Ruscio, J., & Walters, G. D. (2009). Using comparison data to differentiate categorical and dimensional data by examining factor score distributions: Resolving the mode problem. Psychological Assessment, 21, 578–594.

- Ruscio, J., Walters, G. D., Marcus, D. K., & Kaczetow, W. (2010). Comparing the relative fit of categorical and dimensional latent variable models using consistency tests. Psychological Assessment, 22, 5–21.

- *Schmidt, N. B., Kotov, R., Lerew, D. R., Joiner, T. E., & Ialongo, N. S. (2005). Evaluating latent discontinuity in cognitive vulnerability to panic: A taxometric investigation. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 29, 673–690.

- Sheldon, W. H. (1942). The varieties of temperament. New York, NY: Harper.

- *Silove, D., Slade, T., Marnane, C., Wagner, R., Brooks, R., & Manicavasagar, V. (2007). Separation anxiety in adulthood: Dimensional or categorical? Comprehensive Psychiatry, 48, 546–553.

- *Skilling, T. A., Harris, G. T., Rice, M. T., & Quinsey, V. L. (2001). Identifying persistently antisocial offenders using the Hare Psychopathy Checklist and DSM IV antisocial personality disorder criteria. Psychological Assessment, 14, 27–38.

- *Skilling, T. A., Quinsey, V. L., & Craig, W. M. (2001). Evidence of a taxon underlying serious antisocial behavior in boys. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 28, 450–470.

- *Stevens, K. T., Kertz, S. J., Björgvinsson, T., & Mchugh, R. K. (2018). Investigating the latent structure of distress intolerance. Psychiatry Research, 262, 513–519.

- *Strong, D. R., Brown, R. A., Kahler, C. W., Lloyd‐richardson, E. E., & Niaura, R. (2004). Depression proneness in treatment‐seeking smokers: A taxometric analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 36, 1155–1170.

- *Strong, D. R., Glassmire, D. M., Frederick, R. I., & Greene, R. L. (2006). Evaluating the latent structure of the MMPI‐2 F(p) scale in a forensic sample: A taxometric analysis. Psychological Assessment, 18, 250–261.

- *Strong, D. R., Greene, R. L., Hoppe, C., Johnston, T., & Olesen, N. (1999). Taxometric analysis of impression management and self‐deception on the MMPI‐2 in child‐custody litigants. Journal of Personality Assessment, 73, 1–18.

- *Strong, D. R., Greene, R. L., & Kordinak, S. T. (2002). Taxometric analysis of impression management and self‐deception in college student and personnel evaluation settings. Journal of Personality Assessment, 78, 161–175.

- *Strong, D. R., Greene, R. L., & Schinka, J. A. (2000). Taxometric analysis of the MMPI‐2 infrequency scales [F and F(p)] in clinical settings. Psychological Assessment, 12, 166–173.

- *Strube, M. J. (1989). Evidence for the type in type A behavior: A taxometric analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 972–987.

- Terracciano, A., Sanna, S., Uda, M., Deiana, B., Usala, G., Busonero, F., … Costa, P. T. (2010). Genome‐wide association scan for five major dimensions of personality. Molecular Psychiatry, 15, 647–656.

- *Tran, U. S., Bertl, B., Kossmeier, M., Pietschnig, J., Stieger, S., & Voracek, M. (2018). “I'll teach you differences”: Taxometric analysis of the dark triad, trait sadism, and the dark core of personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 126, 19–24.

- Trull, T. J., & Durrett, C. A. (2005). Categorical and dimensional models of personality disorder. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 355–380.

- *Trull, T. J., Widiger, T. A., & Guthrie, P. (1990). Categorical versus dimensional status of borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 99, 40–48.

- *Tyrka, A., Cannon, T. D., Haslam, N., Mednick, S. A., Schulsinger, F., Schulsinger, H., & Parnas, J. (1995). The latent structure of schizotypy: I. Premorbid indicators of a taxon of individuals at risk for schizophrenia‐spectrum disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104, 173–183.

- *van Kampen, D. (1999). Genetic and environmental influences on pre‐schizophrenic personality: MAXCOV‐HITMAX and LISREL analyses. European Journal of Personality, 13, 63–80.

- *Vasey, M. W., Kotov, R., Frick, P. J., & Loney, B. R. (2005). The latent structure of psychopathy in youth: A taxometric investigation. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33, 411–429.

- *Veale, J. F. (2014). Evidence against a typology: A taxometric analysis of the sexuality of male‐to‐female transsexuals. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43, 1177–1186.

- Waller, N. G., & Meehl, P. E. (1998). Multivariate taxometric procedures: Distinguishing types from continua. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- *Walters, G. D. (2009). Latent structure of a two‐dimensional model of antisocial personality disorder: Construct validation and taxometric analysis. Journal of Personality Disorders, 23, 647–660.

- *Walters, G. D. (2011a). The latent structure of life‐course‐persistent antisocial behaviour: Is Moffitt's developmental taxonomy a true taxonomy? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79, 96–105.

- *Walters, G. D. (2011b). Childhood temperament: Dimensions or types? Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 1168–1173.

- *Walters, G. D. (2014). The latent structure of psychopathy in male adjudicated delinquents: A cross‐domain taxometric analysis. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 5, 348–355.

- *Walters, G. D., Brinkley, C. A., Magaletta, P. R., & Diamond, P. M. (2008). Taxometric analysis of the Levenson self‐report psychopathy scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 90, 491–498.

- *Walters, G. D., Diamond, P. M., Magaletta, P. R., Geyer, M. D., & Duncan, S. A. (2007). Taxometric analysis of the antisocial features scale of the personality assessment inventory in federal prison inmates. Assessment, 14, 351–360.

- *Walters, G. D., Duncan, S. A., & Mitchell‐perez, K. (2007). The latent structure of psychopathy: A taxometric investigation of the psychopathy checklist‐revised in a heterogeneous sample of male prison inmates. Assessment, 14, 270–278.

- *Walters, G. D., Ermer, E., Knight, R. A., & Kiehl, K. A. (2015). Paralimbic biomarkers in taxometric analyses of psychopathy: Does changing the indicators change the conclusion? Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 6, 41–52.

- *Walters, G. D., Gray, N. S., Jackson, R. L., Sewell, K. W., Rogers, R., Taylor, J., & Snowden, R. J. (2007). A taxometric analysis of the psychopathy checklist: Screening version (PCL: SV): Further evidence of dimensionality. Psychological Assessment, 19, 330–339.

- *Walters, G. D., Knight, R. A., Looman, J., & Abracen, J. (2016). Child molestation and psychopathy: A taxometric analysis. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 22, 379–393.

- *Walters, G. D., & Ruscio, J. (2009). To sum or not to sum: Taxometric analysis with ordered categorical assessment items. Psychological Assessment, 21, 99–111.

- *Wilmot, M. P. (2015). A contemporary taxometric analysis of the latent structure of self‐monitoring. Psychological Assessment, 27, 353–364.

- *Wilmot, M. P., Haslam, N., Tian, J., & Ones, D. S. (in press). Direct and conceptual replications of the taxometric analysis of type A behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

- *Woodward, S. A., Lenzenweger, M. F., Kagan, J., Snidman, N., & Arcus, D. (2000). Taxonic structure of infant reactivity: Evidence from a taxometric perspective. Psychological Science, 11, 296–301.