Abstract

Background and Objectives

This study investigated psychological wellbeing and sleep characteristics in Victorian racing industry workers, specifically focusing on trainers. There are few empirical studies of psychological wellbeing in the horse racing industry, despite considerable employment numbers and a potentially complex and challenging work environment. Early morning starts, and potentially long working days could compound negative wellbeing outcomes.

Methods

A survey assessing psychological wellbeing and sleep habits was distributed to racing industry employees (N = 358).

Results

Trainers reported significantly higher depression and anxiety scores compared with other racing industry workers, racehorse owners, and the general population. They had less sleeping hours and higher daytime dysfunction due to fatigue. Multivariate pathway analysis showed daytime dysfunction due to fatigue was the sole significant contributor to identified differences in depression and anxiety between trainers and racing industry counterparts.

Conclusions

Daytime dysfunction due to fatigue was an important predictor of lower psychological wellbeing in this sample of horse trainers. Longitudinal and qualitative investigation of both sleep and non‐sleep as factors in generating fatigue could assist to further delineate predictors of depression and anxiety in this population. Better understanding of interacting sleep and wellbeing processes may lead to useful self‐management strategies to address the apparent heightened psychological distress of some racing industry workers.

Funding information Racing Victoria, Grant/Award Number: No associated grant ‐ funding from Racing Victoria

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Anecdotal evidence of heightened stress levels among horse trainers

Horse trainers maintain unusual sleep/wake rhythms in their day‐to‐day work

Poorly entrained sleep/wake rhythms can exacerbate stress and affect workplace performance

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS

Empirical evidence of higher stress levels among horse trainers compared to other racing industry workers and the general population

Horse trainers sleep less and report greater daytime dysfunction due to fatigue than other racing industry workers

Daytime dysfunction due to fatigue is an important predictor of depression and anxiety in horse trainers.

The Australian horse racing industry employs approximately 250,000 staff, including 842 jockeys and 3,342 trainers (Racing Australia, Citation2017). It can be a uniquely satisfying industry to work in (Maurstad, Davis, & Cowles, Citation2013), but also a challenging one. Jockeys, for example, report that long working hours and the physical and cognitive demands of their work are a source of significant stress (Landolt et al., Citation2017). Horse trainers confront similar challenges in this highly competitive industry as well as their own unique psychological stressors, which may include isolation from social networks and the stress associated with managing large numbers of horses and staff (Bartley, Citation2016). While there is anecdotal evidence of stress among trainers, little empirical investigation exists of trainers' mental wellbeing and the causes of stress. Given the early morning starts and the potential for long working days characteristic of the trainer's role, we considered the potentially adverse effects of poor sleep a key area of investigation in this population.

Poor sleep habits are known risk factors for impaired social, physical, and emotional wellbeing. Sleep of insufficient quality and length has been shown to affect immune function (Cohen, Doyle, Alper, Janicki‐Deverts, & Turner, Citation2009), glucose metabolism, and endocrine function (Spiegel, Leproult, & Van Cauter, Citation1999), and mood regulation and cognitive performance (Durmer & Dinges, Citation2005; Watling, Pawlik, Scott, Booth, & Short, Citation2017). Data from the most recent Sleep Health Foundation national survey showed that approximately 50% of Australian adults do not get adequate sleep (Adams et al., Citation2017). Horse trainers are not immune from this wider societal trend for reduced hours of sleep, nor are they immune from the associated deficits in psychological wellbeing.

Impaired psychological wellbeing commonly co‐occurs with poor sleep quality. In a survey of the Australian adult population, people with high to very high levels of psychological distress were 8 to 10 times more likely to have poor sleep quality than those with low levels of distress (Scott, Paterson, & Happell, Citation2014). Indeed, sleep problems are considered practically ubiquitous among mood disorders in particular (Benca et al., Citation1997), but also psychopathology more generally (Harvey, Murray, Chandler, & Soehner, Citation2011).

In addition to the effects of poor sleep quality on physical and mental health, Adams et al. (Citation2017) showed that people who do not get enough sleep reported greater impairment in their daytime activities and were more likely to make errors at work. Van Mill, Vogelzangs, Hoogendijk, and Penninx (Citation2013) reported similar findings in a study of the Dutch population, showing that the combination of psychopathology (depression and anxiety) and sleep problems significantly increased the odds of impaired work performance and absenteeism.

The adverse effects of poor sleep quality on work performance make adequate sleep a potentially important workplace health and safety issue. This is particularly so for horse trainers, whose work conditions dictate that the timing of sleep disrupts the normal sleep/wake cycle. Largely for historical and pragmatic reasons (Timms, Citation2016), horse training trackwork starts in the pre‐dawn period at a time before natural light can align a person's internal circadian clock with the normal 24‐hour light/dark cycle. The resulting misalignment may lead to negative wellbeing outcomes, including depression (Levandovski et al., Citation2011) and poor sleep quality (Dijk & Lockley, Citation2002). The pre‐dawn period is also a non‐optimal time for adequate alertness and cognitive processing (Johnson et al., Citation1992), so normal mental and physical performance is likely to be negatively affected at this time of the day.

The aim of this study was to investigate, first, psychological wellbeing among horse trainers, and, second, to determine whether sleep characteristics have any role in predicting levels of depression and anxiety. To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate sleep and wellbeing outcomes among horse trainers. As a focus for our study, we hypothesised that sleep characteristics will account for any differences in psychological distress between horse trainers and other racing industry workers. This prediction was based on the existing research around sleep and mental health, as well as anecdotal evidence suggesting that trainers may have particularly challenging sleeping habits due to their combination of industry and business stresses, and the necessity of early rising to manage the trackwork of their horses.

1 SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Racing Victoria in conjunction with the Victorian Government funded this study to explore levels of psychological distress and sleep habits among its industry participants, with a particular focus on those who identify as trainers (N = 937 trainers recorded by Racing Victoria).

We recruited members of the Victorian horse racing industry visiting a “Wellbeing Lounge” at the annual yearling sales in early 2017. Adult participants were recruited over 4-days using a combination of paper‐based and computer tablet‐based surveys. Participants were volunteers, and there were no exclusion criteria. Survey instructions referred to the investigation of wellbeing among Victorian horse racing employees in general—there was no mention of a specific focus on trainers. A further round of surveys were distributed to Victorian horse trainers via email in consultation with Racing Victoria to increase the number of respondents and thus enhance the reliability of survey findings. Consenting trainers completed the surveys anonymously and returned them directly to the researchers. At no stage did Racing Victoria have access to individual survey responses. Permissions to undertake the research were granted by the Swinburne University of Technology Ethics Committee (2016/320).

Demographic data and wellbeing information were collected from respondents using the Kessler 10‐item checklist (K10; Kessler et al., Citation2002) and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI; Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman, & Kupfer, Citation1989). The K10 is a widely used, psychometrically sound, and extensively validated community screening measure of anxiety and depression, including in Australian populations (Furukawa, Kessler, Slade, & Andrews, Citation2003). A self‐report questionnaire, it yields a global measure of distress as well as total scores representing the dimensions of anxiety (six items) and depression (four items). Participants were asked how often they experienced each of the 10 symptoms on a 5‐point scale in the last 4 weeks (1 = None of the time, 2 = A little of the time, 3 = Some of the time, 4 = Most of the time, 5 = All of the time). Item scores are summed to create a total distress score and separate anxiety (range = 6–30) and depression scores (range = 4–20). In the current study, categories of global distress were also computed to represent low, moderate, high, and very high distress to enable comparisons with published Australian population data (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2012).

The PSQI is a 9‐item questionnaire that measures various aspects of sleep over the previous month, including subscales addressing duration, time to fall asleep (latency), level of sleep disturbance, level of daytime dysfunction due to sleepiness, sleep efficiency, sleep quality, and use of medications to aid sleep. Higher scores on all subscales indicate worse sleep. A total scale score is calculated from these aspects of sleep with higher total scale scores indicating worse sleep. An empirically derived cut‐off score of >5 distinguishes poor sleepers from good sleepers (Buysse et al., Citation1989) and indicates that a poor sleeper reports severe difficulties in at least two areas, or moderate difficulties in more than three areas. Good sleepers will typically score below 3 and people with diagnosable insomnia will typically score higher than 11.

Gender, age (in years), occupational status, location (indicated by postcode: major city, inner regional, outer regional, and remote), and financial wellbeing were also assessed. An item identical to one used in the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey (Watson & Wooden, Citation2002) assessed financial wellbeing. That is, participants were asked, “Given your current needs and financial responsibilities, would you say that you and your family are: Prosperous (1), Very Comfortable (2), Reasonably Comfortable (3), Just Getting Along (4), Poor (5), Very Poor (6).”

2 DATA ANALYSIS

Data were analysed using the IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 24 (SPSS; IBM Corp, Citation2016) and Mplus Version 7.4 (Muthen & Muthen, Citation2015; Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Factorial analysis of variance was used to explore differences in levels of psychological distress between trainers and non‐trainers. Multivariate pathway analysis was employed to investigate whether subscale scores on the PSQI could explain levels of depression and anxiety among trainers. Prior to conducting the main analyses, data were subjected to preliminary screening analyses. Extensive missing data meant that total K10 and PSQI scores could not be computed for 13 and 6 participants, respectively. These missing scores were excluded from all univariate analyses, but were estimated for the multivariate analyses using Mplus's full information maximum likelihood procedure (Little & Rubin, Citation1987; Muthen & Muthen, Citation2015). The alpha criterion for statistical testing was set at p < 0.05.

3 RESULTS

Three hundred and fifty‐eight racing industry personnel completed the survey, with 91 (25.4%) identifying themselves as horse trainers (representing approximately 10% of all horse trainers registered in Victoria). About 64% of the trainers were men, broadly consistent with industry numbers showing that the majority of Victorian horse trainers are men. The average age of the trainers in the sample was 51-years (SD = 13-years), which is again consistent with industry numbers that show the average age of all Victorian horse trainers is 55-years. In comparison to others (“non‐trainers”) in the sample, horse trainers were significantly older (M = 51-years, SD = 13-years vs. M = 46-years, SD = 15-years, p < 0.05). Trainers also reported statistically lower financial wellbeing than non‐trainers (t [352] = 4.95, p < 0.001), were more likely to reside in inner regional areas than a major city (χ2 [4] = 23.16, p < 0.001), and were more likely to be men (χ2 [1] = 4.59, p < 0.05).

3.1 Psychological distress

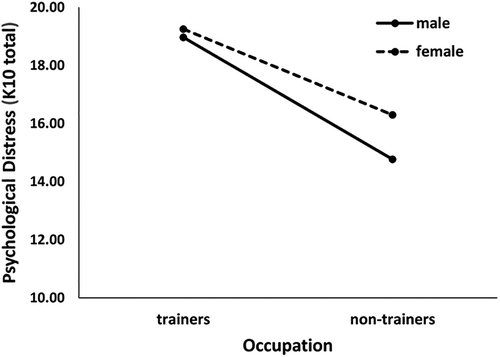

The mean psychological distress scores for the total K10 scale for men and women are displayed in Figure 1. A 2 (occupation) × 2 (gender) completely randomised analysis of variance was used to analyse the K10 data. As Figure 1 shows, the mean psychological distress score of trainers was significantly higher than that reported by non‐trainers, F(1, 336) = 19.01, p < 0.001, partial η 2 = 0.05). No significant gender differences were found and the interaction between gender and psychological distress was not significant, F(1, 336) = 0.57, p = 0.45). Thus, trainers, regardless of gender, reported higher levels of psychological distress than non‐trainers.

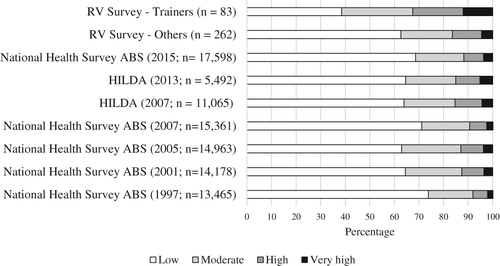

Figure 2 shows that trainers were more likely than non‐trainers and all comparison population samples, to experience moderate, high and very high distress, and less likely to be classified into the low stress group.

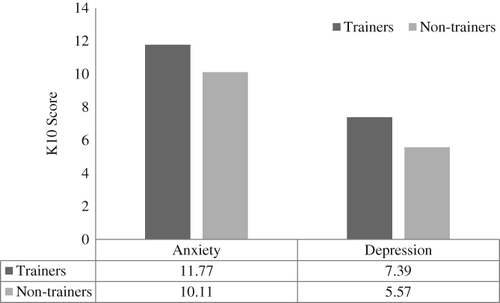

Figure 3 shows that trainers reported significantly higher levels of anxiety, F(1, 342) = 11.35, p < 0.001, partial η 2 = 0.032, and depression, F(1, 344) = 26.02, p < 0.001, partial η 2 = 0.071, than non‐trainers. Direct comparisons with population data were not possible as we do not have access to individual level data.

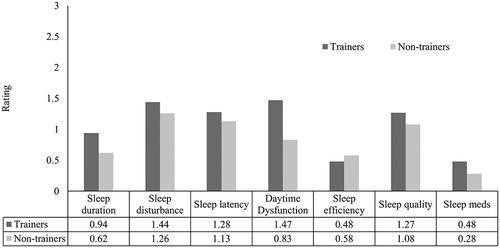

3.2 Sleep quality

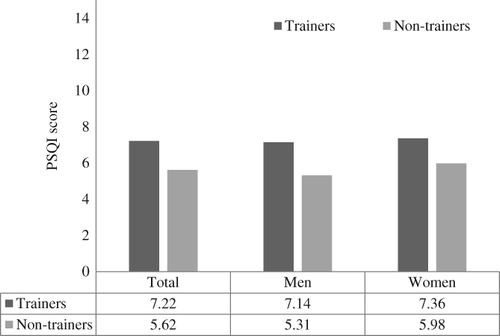

Figure 4 shows that trainers were significantly higher on total PSQI scores than non‐trainers, t(350) = 3.77, p < 0.001. Just under two thirds of trainers (62.64%) scored above the cutoff score of >5 that distinguishes poor sleepers from good sleepers, compared to 45.15% of non‐trainers. Male trainers reported lower sleep quality than female trainers, but the difference was not statistically significant. Female non‐trainers reported lower sleep quality than male non‐trainers, but again, the difference was not statistically significant.

Investigating scores on the subscales of the PSQI reveal the main reasons for worse scores among trainers, with a statistically significant difference between trainers and non‐trainers on sleep duration, t(350) = 3.19, p < 0.01, and Daytime dysfunction, t(350) = 5.15, p < 0.001 (see Figure 5). Worse sleep duration is perhaps not surprising in this sample given the normal working hours of horse trainers. The higher level of daytime dysfunction reported by trainers compared to non‐trainers is more concerning. Scores for the daytime dysfunction subscale are calculated on the basis of responses to two items in the PSQI that refers to (a) “having trouble staying awake while driving, eating meals, or engaging in social activity” and (b) “having problems keeping up enough enthusiasm to get things done.” Trainers are specifically reporting greater difficulties in these two areas compared to non‐trainers.

3.3 Multivariate analysis

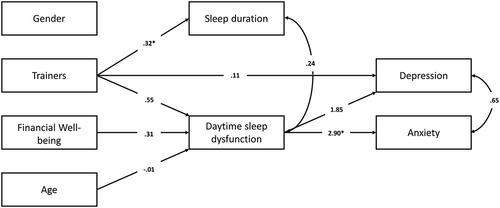

To examine whether sleep disturbance and daytime sleep dysfunction explain the higher levels of depression and anxiety among trainers (relative to non‐trainers), a multiple mediation path model was computed via Mplus Version 7.4 (Muthen & Muthen, Citation2015). Gender, financial wellbeing, and age were included in the model as covariates given the tendency of trainers to be older males with lower financial wellbeing. In addition, depression and anxiety have been consistently associated with age, gender and socioeconomic status (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & Walters, Citation2005), which may obscure the effect of being a trainer on the psychological variables.

Eleven cases were missing on all exogenous variables and removed from the analysis, resulting in a total sample size of 347. The model required 23 parameters to be estimated, resulting in an acceptable case to parameter ratio (i.e., 15:1), and in turn, sufficient statistical power (Byrne, Citation2012). The Satorra‐Bentler Robust Maximum Likelihood estimation method was used to adjust the SEs and chi‐square for multivariate non‐normality. The resulting model was a good fit with the data, χ2 (7) = 16.88, p < 0.05, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.98, Tucker‐Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.94, Root Mean Standard Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.06 (95% confidence interval of RMSEA = 0.03–0.10), Standardised Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) = 0.03, and the parameter estimates are shown in Figure 6.

The direct effects in Figure 6 confirm that trainers tended to experience significantly shorter sleep duration and higher daytime sleep dysfunction than all others in the sample. On average, sleep duration scores were 0.32 of a point higher and daytime sleep dysfunction scores were 0.55 of a point higher among trainers compared to others. Trainers were also more likely to report higher levels of depression. Thus, trainers demonstrated poorer sleep behaviours and increased depression regardless of their gender, socioeconomic status, or age. The results also show that regardless of whether one is a trainer or not, those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and younger people experience significantly more daytime sleep dysfunction (but not shorter sleep duration).

While the direct effects between sleep duration and both depression and anxiety were not significant, the direct effects for daytime dysfunction were significant. This finding suggests that it was increased daytime dysfunction rather than any other sleep factor that was predictive of increased depression and anxiety in this sample. The model also tests for the indirect effects of being a trainer on depression and anxiety through sleep behaviours. Both effects via daytime dysfunction were significant (depression: 1.02, p < 0.001; anxiety: 1.61, p < 0.001) implying that trainers have increased depression and anxiety because they also tend to experience greater daytime dysfunction due to their sleep. The model suggests that trainers are not at risk for increased depression and anxiety because of their greater tendency to have more disturbed sleep. Depression and anxiety increase for trainers because of their higher tendency to experience poorer day‐to‐day functioning due to fatigue. The direct pathway from trainers to depression suggests, however, that trainers were also more depressed for reasons other than daytime dysfunction due to fatigue.

4 DISCUSSION

We conducted this study to establish some baseline mental health and wellbeing measures of the horse trainer population in Victoria, Australia. We hypothesised that trainers would have adverse sleep habits that, in addition to potential challenges that they may experience at work (e.g., pressure from owners for horses to perform, complexities of managing small rural business ventures including managing staff, insecure income, and consequent impacts on personal relationships), may affect psychological wellbeing. This appears to be the first time that sleep and psychological wellbeing outcomes have been studied in this specific employment group. The trainers reported higher levels of depression and anxiety than both a sample of same industry non‐trainers and the general public. Overall sleep quality was also worse among the trainers compared to the non‐trainers and a general population sample. Daytime dysfunction was worse and sleep duration was shorter among the trainers in the sample compared to the non‐trainers. Sleep problems are established predictors of poorer psychological wellbeing in general population samples and indeed that is what we found in the current sample of trainers—daytime dysfunction in normal activity caused by fatigue was a significant predictor of higher depression and anxiety levels in this group. Shorter sleep duration among the trainers was not, however, associated with poorer psychological wellbeing outcomes in this group.

Daytime dysfunction was the only sleep‐related factor to predict higher depression and anxiety in the horse trainers. Self‐reported sleep duration, disturbance, latency, and quality did not contribute to the higher levels of depression and anxiety in this group, despite the trainers having worse overall sleep compared to the non‐trainers and the general population. These findings suggest that trainers' diminished self‐rated ability to do everyday tasks as a result of compromised sleep is an important contributor to their higher levels of depression and anxiety.

The findings reported here and in other recent studies (Adams et al., Citation2017; Van Mill et al., Citation2013) suggest that sleep problems may be an important workplace health and safety issue, particularly when unusual sleep/wake patterns are an integral part of the workplace milieu. In the horse racing industry, most trainers run their own businesses and are therefore ostensibly responsible for setting their own working hours. However, largely for pragmatic reasons (Timms, Citation2016), trainers tend to start work at times of the day that are not optimally aligned with the normal light/dark cycle and which may carry unintended consequences for their health. As the timing of work is a potentially unavoidable feature of the workplace for trainers, the focus should be on evidence‐based strategies for risk management. Strategies that include sleep hygiene education, timed bright light exposure, and napping are recommended (Barion & Zee, Citation2007; Richter, Acker, Adam, & Niklewski, Citation2016). Cognitive‐behavioural intervention programs that specifically target sleep behaviour also show promise in improving overall mental health outcomes (Cunningham & Shapiro, Citation2018).

Some limitations must be considered in reviewing the study outcomes. The study was cross‐sectional and relied on a self‐selecting sample of horse racing industry employees. Inferences of causality in relationships between sleep and psychological distress must therefore be interpreted with caution. The sample of trainers who provided data for the current study was broadly representative of the population of trainers in Victoria in terms of age and gender. Nevertheless, a higher response rate from this population would reduce the risk of respondent self‐selection potentially biasing the study outcomes and thus permit stronger conclusions. Finally, potential causes of heightened anxiety and depression among horse trainers other than sleep—for example, social isolation due to unsociable working hours, relationship conflicts—were not investigated in this study. Higher levels of depression, in particular, were associated with factors not measured in this study. For a comprehensive understanding of psychological distress predictors in this population, these factors should be assessed in parallel with sleep.

The current study provides a baseline reference point for the further investigation of sleep and psychological wellbeing outcomes among horse trainers. Daytime dysfunction caused by fatigue predicted the higher levels of psychological distress in this employee group compared to the same industry non‐trainers. Currently available evidence‐based interventions aimed at improving sleep behaviour and psychological wellbeing among shift workers may be usefully employed in this group. The unique characteristics of the working environment for horse trainers necessitate a more thorough investigation of the underlying reasons for their higher levels of psychological distress. Investigations of impaired circadian alignment and other sleep/wake processes may prove fruitful in this regard. The investigations should also incorporate a broader scope beyond sleep into other known predictors of depression and anxiety, including social isolation, substance use, and relationship stress. A better understanding of explanatory mechanisms will necessarily lead to useful interventions and self‐management strategies for trainers experiencing heightened levels of psychological distress as a result of sleep problems.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by funding from Racing Victoria. The funding agency had no further role in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, and in the decision to submit the paper for publication. K.F. is an employee of Racing Victoria. K.F. contributed vital industry expertise, including study design, and supported participant recruitment activities. K.F. had no role in analysing data or drawing conclusions. Nor did she have any influence in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. K.F. proof‐read the manuscript prior to submission.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

Funding information Racing Victoria, Grant/Award Number: No associated grant ‐ funding from Racing Victoria

REFERENCES

- Adams, R. J., Appleton, S. L., Taylor, A. W., Gill, T. K., Lang, C., Mcevoy, R. D., & Antic, N. A. (2017). Sleep health of Australian adults in 2016: Results of the 2016 Sleep Health Foundation National Survey. Sleep Health, 3(1), 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2016.11.005

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2012). Information paper: Use of the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale in ABS health surveys, Australia, 2007–08. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved from. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@nsf/Lookup/4817.0.55.001Chapter92007-08

- Barion, A., & Zee, P. C. (2007). A clinical approach to circadian rhythm sleep disorders. Sleep Medicine, 8(6), 566–577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2006.11.017

- Bartley, P. (2016). Trainer Tony Vasil back in racing industry after suffering depression. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved from https://www.smh.com.au/sport/racing/trainer-tony-vasil-back-in-racing-industry-after-suffering-depression-20160601-gp92rh.html

- Benca, R. M., Okawa, M., Uchiyama, M., Ozaki, S., Nakajima, T., Shibui, K., & Obermeyer, W. H. (1997). Sleep and mood disorders. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 1(1), 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1087-0792(97)90005-8

- Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F., Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R., & Kupfer, D. J. (1989). The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research, 28(2), 193–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4

- Byrne, B. M. (2012). Structural equation modeling with Mplus: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. New York, NY: Routledge Taylor.

- Cohen, S., Doyle, W. J., Alper, C. M., Janicki‐deverts, D., & Turner, R. B. (2009). Sleep habits and susceptibility to the common cold. Archives of Internal Medicine, 169(1), 62–67. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2008.505

- Cunningham, J. E. A., & Shapiro, C. M. (2018). Cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT‐I) to treat depression: A systematic review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 106, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.12.012

- Dijk, D. J., & Lockley, S. W. (2002). Invited review: Integration of human sleep‐wake regulation and circadian rhythmicity. Journal of Applied Physiology, 92(2), 852–862.

- Durmer, J. S., & Dinges, D. F. (2005). Neurocognitive consequences of sleep deprivation. Seminars in Neurology, 25(1), 117–129. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2005-867080

- Furukawa, T. A., Kessler, R. C., Slade, T., & Andrews, G. (2003). The performance of the K6 and K10 screening scales for psychological distress in the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well‐Being. Psychological Medicine, 33(2), 357–362. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291702006700

- Harvey, A. G., Murray, G., Chandler, R. A., & Soehner, A. (2011). Sleep disturbance as transdiagnostic: Consideration of neurobiological mechanisms. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(2), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.003

- IBM Corp. (2016). IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

- Johnson, M. P., Duffy, J. F., Dijk, D. J., Ronda, J. M., Dyal, C. M., & Czeisler, C. A. (1992). Short‐term memory, alertness and performance: A reappraisal of their relationship to body temperature. Journal of Sleep Research, 1(1), 24–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2869.1992.tb00004.x

- Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S. L. T., … Zaslavsky, A. M. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non‐specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 959–976. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291702006074

- Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W., Demler, O., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12‐month DSM‐IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 617–627. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617

- Landolt, K., O'halloran, P., Hale, M. W., Horan, B., Kinsella, G., Kingsley, M., & Wright, B. J. (2017). Identifying the sources of stress and rewards in a group of Australian apprentice jockeys. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 9(5), 583–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2017.1340329

- Levandovski, R., Dantas, G., Fernandes, L. C., Caumo, W., Torres, I., Roenneberg, T., … Allebrandt, K. V. (2011). Depression scores associate with chronotype and social jetlag in a rural population. Chronobiology International, 28(9), 771–778. https://doi.org/10.3109/07420528.2011.602445

- Little, R. J., & Rubin, D. B. (1987). Statistical analysis with missing data. New York, NY: Wiley.

- Maurstad, A., Davis, D., & Cowles, S. (2013). Co‐being and intra‐action in horse‐human relationships: A multi‐species ethnography of be(com)ing human and be(com)ing horse. Social Anthropology, 21(3), 322–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-8676.12029

- Muthen, L. K., & Muthen, B. O. (2015). Mplus user's guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen.

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–91.

- Racing Australia. (2017). Annual report. Retrieved from https://www.racingaustralia.horse/Aboutus/AnnualReport.aspx

- Richter, K., Acker, J., Adam, S., & Niklewski, G. (2016). Prevention of fatigue and insomnia in shift workers—A review of non‐pharmacological measures. The EPMA Journal, 7(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13167-016-0064-4

- Scott, D., Paterson, J. L., & Happell, B. (2014). Poor sleep quality in Australian adults with comorbid psychological distress and physical illness. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 12(4), 331–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2013.819469

- Spiegel, K., Leproult, R., & Van cauter, E. (1999). Impact of sleep debt on metabolic and endocrine function. The Lancet, 354(9188), 1435–1439. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01376-8

- Timms, D. (2016). Majority rules for early start times. Herald Sun. Retrieved from https://www.heraldsun.com.au/sport/superracing/majority-rules-for-early-start-times/news-story/c5c28ca7270ba7f77021fbedcd3b93c2

- Van mill, J. G., Vogelzangs, N., Hoogendijk, W. J. G., & Penninx, B. W. J. H. (2013). Sleep disturbances and reduced work functioning in depressive or anxiety disorders. Sleep Medicine, 14(11), 1170–1177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2013.04.016

- Watling, J., Pawlik, B., Scott, K., Booth, S., & Short, M. A. (2017). Sleep loss and affective functioning: More than just mood. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 15(5), 394–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2016.1141770

- Watson, N., & Wooden, M. (2002). The household, income and labour dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey: An introduction. Australian Social Policy, 2001–02, 79–99.