Abstract

Background

Children exposed to intimate partner violence (IPV) are at heightened risk of emotional and behavioural problems. However, not all children exposed to IPV experience difficulties. Many display positive wellbeing and development despite experiencing this adversity.

Objective

This is the first known article to systematically review the existing literature on the factors associated with emotional and behavioural resilience and positive functioning in children exposed to IPV.

Method

This review was registered at the PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews, registration number CRD42016037101. Four databases were searched (Embase, Web of Science, Psychinfo, and Medline) for peer‐reviewed articles assessing factors associated with positive outcomes for children (aged between 0 and 12-years) who had been exposed to IPV. Retrieved articles were screened for eligibility by two independent reviewers.

Results

Of the 1,365 retrieved articles, 15 were eligible for inclusion. Results showed that maternal mental health was a significant predictor of resilience in children exposed to IPV. Preliminary evidence was found for emotion coaching, parenting, and child temperament. Broader socio‐contextual factors were largely neglected across the articles reviewed.

Conclusion

The findings from this review highlighted that there is still much to be learned about what helps children display resilience when exposed to IPV and what can be done to foster this resilience.

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS TOPIC?

Children exposed to IPV are at an increased risk of emotional‐behavioural problems.

Children are impacted by exposure to both physical and psychological IPV.

Not all children exposed to IPV display difficulties in their emotional‐behavioural functioning.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Between 20‐90% of children exposed to IPV display emotional‐behavioural resilience.

Maternal psychological wellbeing is protective for children exposed to IPV and encouraging women to seek help for themselves in important in promoting positive outcomes in children.

Assisting parents to increase their awareness of their child's emotions and respond using emotion coaching techniques may promote positive emotional‐behavioural outcomes in children exposed to IPV.

INTRODUCTION

There is a growing awareness of the prevalence of intimate partner violence (IPV) with 30% of women expected to experience IPV during their lifetime (World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2013). IPV refers to any act within a current or previous intimate relationship that causes physical, sexual, or psychological harm (WHO, Citation2013). While IPV directly impacts women, it is also a serious issue for children, with 26% exposed to IPV at some point during childhood (Hamby, Finkelhor, Turner, & Ormod, Citation2011). The relationship between exposure to IPV and negative child outcomes is well established. In particular, there is an association with higher rates of depression, anxiety, post‐traumatic stress reactions, as well as behavioural difficulties, sleep disturbances, lower levels of cognitive functioning, and peer problems (Bogat, DeJonghe, Levendosky, Davidson, & von Eye, Citation2006; Flach et al., Citation2011; Wolfe, Crooks, Lee, McIntyre‐Smith, & Jaffe, Citation2003). However, not all children who are exposed to IPV experience poor outcomes (Holt, Buckley, & Whelan, Citation2008). Therefore, it is important to better understand why some children do well and experience good health and wellbeing despite their exposure to IPV. This systematic review aims to synthesise the existing evidence of factors associated with resilience in children who have been exposed to IPV. This will help to understand how children can be best supported during this time.

Childhood exposure to IPV can take many forms. The most obvious of these is directly witnessing IPV between caregivers or attempting to intervene to protect a loved one (Kitzmann, Gaylord, Holt, & Kenny, Citation2003). Notably, regardless of the form of IPV exposure, it has similar impacts on children's development (Kitzmann et al., Citation2003). Several published reviews have summarised the impact of IPV exposure on children. A meta‐analysis of 41 studies found a significant but small effect size (r = 0.28) for the impact of exposure to IPV on child emotional‐behavioural functioning (Wolfe et al., Citation2003). In a larger meta‐analysis (N = 118), 63% of exposed children were reported to have significantly more difficulties in emotional‐behavioural functioning than non‐exposed children (Kitzmann et al., Citation2003). Importantly, however, Kitzmann et al. (Citation2003) identified that approximately 37% of children exposed to IPV, displayed outcomes similar or better than non‐exposed children. A literature review similarly reported on the consistent finding of a group of children who were exposed to IPV but did not display difficulties (Holt et al., Citation2008). Taken together, these results suggested that many children adapt and display resilience despite the risk associated with exposure to IPV.

Resilience is defined as positive or successful adaptation in the face of significant adversity (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, Citation2000). The concept of resilience is multidimensional, and consequently a child might show resilience following one adversity but not another, or in one area of functioning but not another (Wright, Masten, & Narayan, Citation2005). However, research into developmental cascades suggests that when domains of development are conceptually related, competence in one domain can contribute to competence in another (Masten & Cicchetti, Citation2010). To gain insight into why some individuals adapt to certain adversities, resilience researchers aim to identify those factors which interfere with risk, and are associated with positive outcomes (Masten, Citation2001). These factors might be individual characteristics or part of the family or socio‐cultural environment. In this way, resilient outcomes are determined by complex patterns of interactions between the individual, the adversity that the individual experiences, and the environment (Wright et al., Citation2005).

In recent times, there has been a small but growing emphasis on identifying factors which might promote positive adaptation in children exposed to IPV (Graham‐Bermann, Gruber, Howell, & Girz, Citation2009; Howell, Graham‐Bermann, Czyz, & Lilly, Citation2010; Martinez‐Torteya, Anne Bogat, von Eye, & Levendosky, Citation2009). Across these studies, different terms, including resilience, adaptation, or positive functioning, have been used to refer to positive outcomes (Graham‐Bermann et al., Citation2009; Manning, Davies, & Cicchetti, Citation2014; Martinez‐Torteya et al., Citation2009; Miller, VanZomeren‐Dohm, Howell, Hunter, & Graham‐Bermann, Citation2014; Owen, Thompson, Shaffer, Jackson, & Kaslow, Citation2009). By consequence, there is some confusion as to whether these studies are measuring comparable constructs. Moreover, inconsistency exists in the types of outcomes assessed in these studies with some focusing on a broad definition of emotional‐behavioural functioning (Insana, Foley, Montgomery‐Downs, Kolko, & McNeil, Citation2014; Martinez‐Torteya et al., Citation2009) while others have taken a narrower focus such as social functioning (Bowen, Citation2015). These inconsistencies make it difficult to obtain an accurate picture of the individual and socio‐contextual factors which promote successful adaptation in children exposed to IPV. A clearer understanding of such protective factors could better guide families and service providers as to the best way to support children and promote positive emotional‐behavioural wellbeing when exposed to IPV (Graham‐Bermann & Hughes, Citation2003).

Study objective

To date, no known systematic reviews have been conducted in this area. The purpose of this article was to provide a systematic review of studies identifying factors promoting positive outcomes in children who have been exposed to IPV. Keeping the multidimensional nature of resilience in mind, it was important to ensure that the studies assessed in the current review measured similar outcomes. The large majority of research into the impact of IPV exposure on children has focused on emotional‐behavioural outcomes; that is internalising (e.g., depression and anxiety) and externalising (such as conduct) difficulties. Similarly, the current review has focused on emotional‐behavioural functioning and resilience defined by the absence of difficulties in these domains.

METHOD

Data sources

The following key words were used to carry out the search strategy: “intimate partner violence,” “intimate partner abuse,” “domestic violence,” “Child*,” “resilien*,” “protective,” and “risk.” The strategy searched four databases (Embase, Web of Science, Psychinfo, and Medline) for articles published between January 1, 2005 until November 9, 2015. Additional articles were retrieved via manual searches of the reference list of included articles, literature reviews, and via automated alerts emailed to the author from the four databases of articles meeting the search terms from November 10, 2015 and December 2017.

Study selection

Studies were included in the review if (a) participants were children aged between 0 and 12 years who had (currently or previously) been exposed to IPV or mothers who had experienced IPV with children aged between 0 and 12-years, (b) protective and/or risk factors associated with child outcomes were assessed, (c) outcomes of the study addressed positive functioning in children, and (d) the study was written in English language. Intervention and qualitative articles were excluded from review.

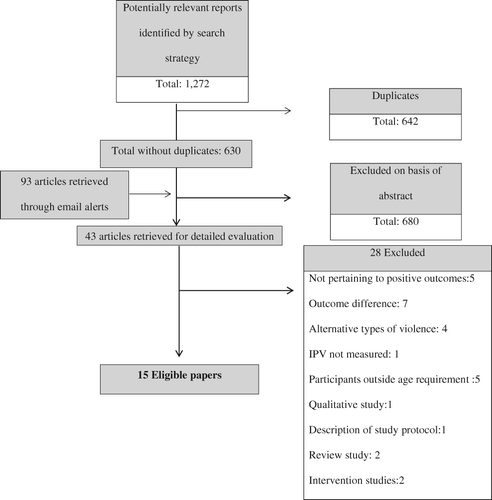

The initial search generated 1,272 citations, which were exported into Endnote for review. Once duplicates were removed, two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts of the citations to determine eligibility. When necessary, full‐texts of the citations were retrieved to assess eligibility. A further 93 articles published after November 9, 2015 were retrieved via database email alerts. Any queries about inclusion were discussed between the reviewers until a mutual decision was agreed upon.

Quality appraisal, data extraction, and analysis

The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement (Von Elm et al., Citation2008) was used to evaluate the quality of included articles. The STROBE statement can be used with cross‐sectional or cohort studies and assesses the quality across the following domains: (a) clarity of aims, (b) appropriateness and rigour of design and analysis, (c) risk of bias, and (d) relevance of results (Von Elm et al., Citation2008). Data were extracted by one reviewer using a standardised data extraction form developed for this review. Due to the heterogeneity of the included studies, a meta‐analysis was deemed unsuitable and the data were analysed qualitatively. This review was registered at the PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews, registration number CRD42016037101.

RESULTS

Of the 1,365 articles retrieved, 14 met the eligibility criteria. An additional study by Insana et al. (Citation2014) met all but one eligibility criteria with the age of participants ranging from 6 to 13-years of age (outside of our criteria of 0–12-years of age). Due to the significant overlap of their age range with the current eligibility criteria, it was decided to include the study by Insana et al. in this systematic review. Figure 1 displays the details of study selection.

Description of the studies

Table displays the characteristics of the included studies. The sample sizes of the 15 included studies ranged from 22 to 7,743 with the median size at 120. Thirteen of the 15 studies were conducted in the United States and 12 used a cross‐sectional design.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies

Table displays the exposure and outcome measures reported. Four of the articles asked directly about children witnessing the IPV with the remaining 11 assuming that children were exposed if their mother or primary caregiver reported violence. Nine of the studies assessed for physical violence or threat alone with four studies assessing physical and psychological violence. Only two studies included a measure of physical, psychological, and sexual violence. The most common tool used to assess abuse was the Conflict Tactic Scale (CTS) (Straus, Citation1979) or the Revised Conflict Tactic Scale (CTS2) (Straus, Hamby, Boney‐McCoy, & Sugarman, Citation1996) with over half using either the full version or a subscale. There was significant diversity among the measures used to assess resilience with the most common being the Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Edelbrock, Citation1993) (utilised by eight of the studies). The ninth study used the Social Competency Scale (SCS) (Conduct Problem Prevention Research Group, Citation2002) and validated this scale against the CBCL (Achenbach & Edelbrock, Citation1993). Other emotional‐behavioural scales such as Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, Citation2001) and the Behavioural and Emotional Rating Scale (BERS; Epstein, Harniss, Pearson, & Ryser, Citation1999) were used. Eight of the studies used solely maternal reports for child measures with four utilising both maternal reports and self‐report. Alternatively, one study used only self‐report with the remaining two studies using researcher‐reports of child adjustment.

Table 2. Exposure and outcome measures of included studies

Longitudinal designs were utilised by just three of the included studies (Bowen, Citation2017; Manning et al., Citation2014; Martinez‐Torteya et al., Citation2009). Bowen (Citation2017) used data from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC). Mothers were recruited during pregnancy with children identified as exposed to IPV if their mothers reported IPV at 8, 21, or 33-months postpartum. Child outcomes were measured at 47-months of age, and predictor variables at varying time points between 6 and 47-months. Specific retention rates were not reported; however, Bowen (Citation2017) reported that mothers who participated in all waves of the study were more likely to be white, have higher education levels and have children with higher levels of adjustment. No differences in experiences of IPV were reported between the original and final sample. The longitudinal design utilised by Manning et al. (Citation2014) measured IPV, child outcomes, and predictor variable across three waves. These waves occurred when the children were 2, 3, and 4 years. Retention rates between waves one to two and waves one to three were reported at 83 and 87%, respectively, with differences between waves not reported. Lastly, Martinez‐Torteya et al. (Citation2009) also utilised longitudinal design measuring IPV exposure, child outcomes, and predictor variables when children were 2, 3, and 4 years. Retention rates were reported to be high with no differences found in prevalence of IPV, maternal depression or income between those who remained in the study at 4 years and those who were lost to follow‐up.

With respect to risk and protective factors, 12 of the 15 studies examined maternal factors. For instance, eight studies included a measure of maternal psychological wellbeing in their analysis. Individual child factors such as race, gender, and temperament were also identified. Only one study explored broader community factors (involvement in judicial process). A full list of the factors and their corresponding results across the 15 studies are presented in Table . Regression equations (hierarchical or logistically) were most commonly selected for statistical analysis with structural equation modelling, analysis of variance (ANOVA), t‐tests, and correlation each used by individual studies.

Table 3. Psychosocial factors assessed across the included studies and the corresponding results

Prevalence of emotional‐behavioural resilience

Only three studies reported on the prevalence of emotional‐behavioural resilience (Graham‐Bermann et al., Citation2009; Martinez‐Torteya et al., Citation2009 & McDonald et al., Citation2016). The prevalence rate in one further study was able to be calculated based on presented results (Bowen, Citation2017). Bowen (Citation2017) cross classified exposure to IPV with SDQ scores to determine four groups of children, listing the number of children within each group: non‐resilient (N = 129); vulnerable (N = 241); competent (N = 6,135); and resilient (N = 1,238). Based on these sample sizes we were able to calculate that, out of the children who were exposed to IPV (non‐resilient and resilient group) 90% displayed emotional‐behavioural resilience. Across these four studies the prevalence of emotional‐behavioural resilience in children exposed to IPV ranged between 20 and 90%. This large range may be best explained by differences between the samples utilised. For instance, the study by Graham‐Bermann et al. (Citation2009) (reporting a 20% prevalence of emotional‐behavioural resilience) recruited participants from domestic services and consequently, may represent a sample of children exposed to more frequent and severe exposure to violence. Conversely, the study reporting a 90% prevalence of emotional‐behavioural resilience was a large community‐based cohort study. This study is likely to include children with a broader range of exposure to IPV. In addition, a single item measure of resilience was used in this study which may have led to some children being misclassified as having IPV exposure.

Individual level protective factors

Six studies investigated the role of individual level factors such as temperament, sleep, and race/ethnicity. Bowen (Citation2017) and Martinez‐Torteya et al. (Citation2009) were the only authors to assess child temperament, with both studies assessing resilience in preschool‐aged children from community samples with sample sizes of 7,743 and 190, respectively. Martinez‐Torteya et al. (Citation2009) summed subscales of the Carey Temperament Scales (CTSs) to form an ease of temperament variable, finding that higher scores on this variable significantly predicted resilience. Bowen (Citation2017) also assessed temperament using the CTSs, however, used only the mood and intensity dimensions of this scale. This study also incorporated the Emotionality Activity Sociability questionnaire which yields the four subscales of: emotionality; activity; shyness, and sociability, as well as the social achievement scale from Denver Development Screening Test, measuring children cooperation, autonomy, and engagement in socially appropriate behaviours. This study by Bowen assessed individual components of temperament, finding emotionality, activity and shyness were significantly associated with children's emotional‐behavioural resilience in both girls and boys. However, sociability was associated significantly with this resilience in boys exposed to IPV but not in girls, and social development was significant for girls but not boys.

Child ethnicity/race was investigated by 4 of the 15 studies (Bowen, Citation2017; Howell et al., Citation2010; Martinez‐Torteya et al., Citation2009 & McDonald et al., Citation2016). There were inconsistencies in the terminology used between studies, with two studies referring to race (Bowen, Citation2017; Martinez‐Torteya et al., Citation2009), one to ethncity (Howell et al., Citation2010), and one to race/ethnicity (McDonald et al., Citation2016). The measurement of ethnicity was not reported by Howell et al. (Citation2010); however, both Bowen (Citation2017) and Martinez‐Torteya et al. (Citation2009) used a dichotomous variable of “white” or “not white.” Non‐significant findings were reported by these three studies, all of which used samples of preschool‐aged children with sample sizes varying from 190 to 7,743. Conversely, in a large (N = 289) sample of 7–12-year olds recruited from domestic violence services, McDonald et al. (Citation2016) categorised ethnicity as: white non‐Latino; Latino; multi‐ethnic; or other, finding that IPV exposed Latino children were significantly more likely to be categorised as asymptomatic. Despite this large sample, the majority of participants were classified as Latino. Small numbers of participants classified as non‐Latino white (17.9%) or “other ethnicities” (4.8%) may have been limited the statistical power to detect associations between these groups and positive outcomes.

There were a number of individual factors assessed by studies that were not found to be associated with emotional‐behavioural resilience in children exposed to IPV. For instance, child gender, which was assessed across both preschool‐ (N = 56) and school‐aged (N = 289) samples (Howell et al., Citation2010; McDonald et al., Citation2016), was not found to be associated with children's emotion‐behavioural resilience. Cognitive ability was also found to be non‐significant in a community sample of 190 preschool‐aged children (Martinez‐Torteya et al., Citation2009). In school‐aged children, both lack of sleep difficulties (Insana et al., Citation2014) and children's immediate reaction to provocation (Allen, Wolf, Bybee, & Sullivan, Citation2003) were assessed, with no signifcant assoication found in samples of 100 and 80 preschool children, respectively. Small sample sizes across studies looking at individual level factors may have limited statistical power to detect associations between factors and resilient outcomes.

Family level protective factors

Maternal factors

Family level factors such as maternal mental health and parenting were a predominant focus of the studies included in this review. Six of the 15 studies assessed maternal mental health as defined as lack of clinically significant maternal depressive or psychiatric symptoms. Five of these studies found maternal mental health to be significantly associated with emotional‐behaviour resilient outcomes (Graham‐Bermann et al., Citation2009; Howell et al., Citation2010; Martinez‐Torteya et al., Citation2009; Owen et al., Citation2009). These studies varied in sample sizes (N = 56–219) and included studies of both preschool‐aged and school‐aged children. When assessed in the study by Cohodes, Chen, and Lieberman (Citation2017) in a community sample of 95 preschool‐aged children, maternal psychiatric symptoms were associated with changes in externalising but not internalising symptoms. However, a lack of statistical power might have impacted on the ability to detect an association for internalising symptoms in this study. The significance of maternal psychological wellbeing or absence of maternal psychological distress across these five studies varied from p < 0.05 (Owen et al., Citation2009) to p < 0.001 (Howell et al., Citation2010). Last, Bowen (Citation2017) assessed maternal depressive symptomology across child gender in a large community study of 7,743 4‐year‐old children, finding no association with children's behavioural resilience in either boys or girls.

Parenting as a predictor of resilience was assessed across 3 of the 15 studies with mixed results. Each study relied on a different measure of parenting around the domains of nurturing, positive discipline, and/or consistent parenting. In a study of 56 preschool‐aged children recruited from domestic violence shelters and services, Howell et al. (Citation2010) found that parenting effectiveness, positive parenting, and consistent parenting significantly predicted resilience in children exposed to IPV. In contrast, another study of 190 preschool‐aged children, this time from a large community sample, found that maternal nurturing behaviour, positive discipline and consistency were not associated with resilient outcomes (Martinez‐Torteya et al., Citation2009). Only one study assessed parenting within school‐aged children. In this study of 219 children recruited from parenting support groups, Graham‐Bermann et al. (Citation2009) found parenting warmth and effectiveness was significantly associated with emotional‐behavioural resilient outcomes.

Other factors relating to the mother–child relationship were also investigated (Katz, Hunter, & Klowden, Citation2008; Manning et al., Citation2014; Owen et al., Citation2009; Skopp, McDonald, Jouriles, & Rosenfield, Citation2007). When IPV levels were high, Manning et al. (Citation2014) found maternal sensitivity, defined by maternal warmth, child‐centeredness, and supportive presence, to be significant predictors of prosocial behaviour and lower levels of externalising behaviour in a sample of preschool‐aged children (N = 201). Similarly, in a sample of 157 school‐aged children, Skopp et al. (Citation2007) found that maternal warmth significantly moderated the relationship between exposure to IPV and children's externalising behaviour with exposure to IPV associated with externalising problems at lower, but not higher levels of maternal warmth.

Maternal emotion coaching (the degree of respect which parents show for their child's emotional experience, and their ability to assist their child to adaptively cope with their emotions) was associated with emotional‐behavioural functioning in three of the included studies (Cohodes et al., Citation2017; Johnson & Lieberman, Citation2007; Katz et al., Citation2008). In a small sample (N = 30) of preschool‐aged children, recruited from a domestic violence shelter population, Johnson and Lieberman (Citation2007) found that mother's ability to attune to sad and angry emotions accounted for significant variance in children externalising behaviour but were not associated with children's internalising behaviour. Katz et al. (Citation2008) and Cohodes et al. (Citation2017) assessed emotion coaching as a moderator. In another small community sample (N = 95) of preschool children, Cohodes et al. (Citation2017) investigated whether emotion coaching moderated the relationship between maternal psychiatric symptomology and internalising and externalising behaviour in children exposed to IPV. This study found that maternal awareness of children's negative emotions moderated the relationship between maternal symptomology and children's externalising and internalising behaviours. Similarly, maternal coaching of negative emotions moderated the relationship between maternal symptomology and children's internalising but not externalising behaviours. No significant role was found for maternal acceptance of children's negative emotions. The small sample size used in this study may have limited the statistical power needed to identify a significant role of maternal acceptance of children's negative emotions. Similarly, Katz et al. (Citation2008), investigated emotion coaching in a small sample (N = 67) of school‐aged children. They found that when levels of maternal emotion coaching were high, children exposed to high levels of IPV were more likely to display adaptive social behavioural responses. Finally, maternal involvement in childcare activities such as “bathing the child” and “cuddling the child” was assessed by Bowen (Citation2017) in a large community sample of 7,743 preschool‐aged children. Although not using a validated measure, maternal involvement in childcare activities, was found to significant predict emotional behavioural resilience in girls but not boys exposed to IPV.

The influence of mother–child attachment and family cohesion were assessed by Owen et al. (Citation2009) and Johnson and Lieberman (Citation2007). Owen et al. found that child ratings of both attachment relationship and family cohesion significantly mediated the relationship between IPV exposure and adaptive functioning in sample of 139 8‐ to 12‐year‐old children. This finding was, however, non‐significant when maternal reports of attachment and family cohesion were used. Conversely, Bowen (Citation2017), in a large community sample (N = 7,743) of 4 year olds, found maternal reports of reunion warmth (defined by reports of child's behaviour when reuniting with mother after a period of separation) to significantly predict resilience for girls exposed to IPV, however, this was non‐significant for boys. The measure of reunion warmth used by this study was not validated and comprised just three items. Consequently, caution should be taken when interpreting these findings. Johnson & Lieberman also found that quality of mother–child interactions significantly predicted children's externalising behaviour, in a small sample (N = 30) of 3‐ to 5‐year‐old children. This study found quality of mother–child interactions to significantly correlate to children's internalising behaviours. However, due to the non‐significance of their other variables of interest, conducting a regression analysis for internalising behaviour did not fit with their study aims.

Other family level factors

Partner warmth towards the child and partner involvement in childcare activities were assessed by Skopp et al. (Citation2007) and Bowen (Citation2017), respectively. In their study, Skopp et al. (Citation2007) found high levels of partner warmth to significantly predict higher child externalising behaviour in a medium‐sized (N = 157) sample of 7–9 year olds, identifying it as a potential risk factor for child outcomes when IPV is present. In contrast, partner involvement in childcare activities was not found to be significantly associated with emotional‐behavioural resilience in 7,743 preschool‐aged children exposed to IPV (Bowen, Citation2017). This study, however, lacked a validated measure of partner involvement. The study relied on nine items around caregiver engagement (e.g., “feeding the child” and “cuddling the child”), as reported by mothers.

Miller et al. (Citation2014) examined the role of in‐home family supports in a sample of 4–6 year old children (N = 120) of whom, 52% had previously used a domestic violence shelter. They found that larger in‐home social supports (defined by number of significant people living in the family home) predicted lower emotional‐behavioural problems in children exposed to IPV. However, a further analysis found maternal level of education moderated this effect. Specifically, for mothers' with lower education levels, child emotional‐behavioural problems decreased as in‐home social support increased. Similarly, Bowen (Citation2017) and Martinez‐Torteya et al. (Citation2009) both investigated whether having a mother who experienced few stressful life events was protective for children exposed to IPV. Both studies were of large community‐based samples of preschool‐aged children, and found this to be non‐significant.

Two studies investigated the protective role of the family's total monthly income (Howell et al., Citation2010; Martinez‐Torteya et al., Citation2009) in children of preschool age (N = 56 and 190, respectively). Howell et al. (Citation2010) assessed a family's income through a dichotomous variable of “above $1,000” or “below $1,000,” whereas Martinez‐Torteya et al. (Citation2009) recorded income as a continuous variable. Despite the differences in categorisation, neither study found total family income per month to predict resilience in those children exposed to IPV.

Last, maternal education level was assessed by both Bowen (Citation2017) and McDonald et al. (Citation2016) with contrasting results. Bowen (Citation2017), in a large community sample (N = 7,743) of 4 year old children, found that children whose mothers had higher levels of education had significantly increased odds of being classified as resilient. However, in a large sample (N = 289) of 7–12-year old children, McDonald et al. (Citation2016) found that higher levels of maternal education to be associated with internalising difficulties in children exposed to IPV.

Community level protective factors

Just one study investigated the protective role of a community level factor. Georgsson, Almqvist, and Broberg (Citation2011) compared emotional‐behavioural functioning for children who were and were not involved in any kind of judicial or civil dispute or process with the violent partner. Their study included a small sample (N = 22–24) of children aged 7–10 years, recruited from an IPV treatment program. Despite lacking statistical power, t‐tests revealed that children who were not involved in a judicial process had higher levels of emotional‐behavioural functioning than those who were involved in a judicial process.

Quality appraisal

Articles included in the analysis were assessed against the STROBE statement (Von Elm et al., Citation2008) to systematically evaluate methodological issues that might impact the validity of the results. Sampling issues were identified in 9 of 15 studies, where the majority of participants were recruited from shelter populations and/or social service agencies. These samples are generally characterised by social disadvantage and are not representative of the wider community population where IPV remains prevalent (Gartland et al., Citation2014). In addition, six of the studies had small sample sizes (N = 22, 30, 56, and N = 69, 80, 95), which compromised statistical power. As a result, it was unclear if non‐significant findings were a result of this limited power or a lack of relationship between the variables. There was lack of consistency in how IPV was measured with some studies using a component of a validated scale, or one or two items. Few studies included a measure of psychological or emotional abuse, which is included in the WHO (Citation2013) definition of IPV. Twelve of the 15 studies were cross‐sectional in design, often assessing children's exposure to IPV across the prior 12‐month period. Consequently, this review was unable to consider protective factors for children with past exposure, or the impact of cumulative and chronic exposure over time. Research also varied in the methods used to collect information about children's resilience with most studies using parent or maternal reports. Other studies relied on child self‐report measures, while a small number used observer or researcher reports. Just three studies used both child and maternal reports of resilience. Last, just eight of the included studies included a reference group of not exposed children to be used as a control group in their analysis.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review revealed a small but growing body of literature on factors associated with emotional‐behavioural resilience and adjustment in children exposed to IPV. This systematic review is the first known to address this area. It aimed to better understand how some children show resilience despite IPV exposure, and to synthesise the evidence for factors promoting positive outcomes. This review also highlighted key methodological considerations in the field. Fifteen recent studies of mothers and their children aged between 0 and 13-years were included in the review. The prevalence of resilience among children exposed to IPV ranged from 20 to 90% between studies. Promising evidence was found for the protective role of family factors such as maternal mental health and emotion coaching. Preliminary evidence was also found for individual child factors including temperament. The results of this review provide a unique overview of empirical research focusing on resilience and or positive adjustment in this population, and highlighted that there is little evidence to date as to factors within the broader community might be protective for children exposed to IPV.

Overall, the literature supports the protective role of maternal mental health in promoting resilience in children exposed to IPV (Cohodes et al., Citation2017; Graham‐Bermann et al., Citation2009; Howell et al., Citation2010; Martinez‐Torteya et al., Citation2009; Owen et al., Citation2009). This evidence is largely based on preschool‐aged children, with just one known study asssesing the protective role of maternal mental health in school‐aged children. Several authors (Howell et al., Citation2010; Martinez‐Torteya et al., Citation2009) offer an explanation for the protective role of maternal mental health stating that women who experience good mental health are more likely to model emotional intelligence through responding adaptively to stress, therefore assisting their children to regulate their own emotional responses. The protective role of maternal mental health is not surprising given the well‐established link between maternal depression and emotional‐behavioural difficulties (Giallo, Woolhouse, Gartland, Hiscock, & Brown, Citation2015). However, given the significant impact that experiencing abuse can have on women's mental health (Woolhouse, Gartland, Hegarty, Donath, & Brown, Citation2012), it does emphasise the importance of services identifying IPV and co‐occurring mental health concerns.

Despite the evidence supporting the protective role of maternal mental health in promoting resilience in children exposed to IPV, Bowen (Citation2017) found that although IPV exposed children were more likely to have a mother experiencing mental health difficulties, maternal mental health did not predict child outcomes. This was the only study examining maternal mental health across child gender. It may be that the subtle differences in profiles of adjustment present when gender differences are examined, explain this result. This study did, however, find that for boys, higher levels of maternal mental health were associated with resilient versus vulnerable group memberships (those children not‐exposed to IPV but displaying behavioural problems). In addition, for girls, higher levels of maternal mental health were associated with resilient versus competent group membership (children not exposed to IPV who are displaying positive adjustment). These findings indicate that maternal mental health is likely to influence resilience processes and emphasise the importance of promoting the mental health of mothers important in fostering positive outcomes in children. However, in high risk settings, such as when IPV is present, this protective pathway might not be as clear. It is also important to note that maternal mental health in these studies was determined by the absence of negative mental health symptoms. Positive mental health attributes such as self‐competence and optimism would provide a more accurate picture of the protective role maternal mental health may play (Graham‐Bermann et al., Citation2009).

A predominant focus of the included studies was the relationship and interactions between mothers and their children. Three studies assessed the role of parenting across the domains of positive discipline, consistency, and nurturance with mixed results (Graham‐Bermann et al., Citation2009; Howell et al., Citation2010; Martinez‐Torteya et al., Citation2009). Whilst two studies found parenting behaviours to be a protective factor for preschool‐ and school‐aged children exposed to IPV (Graham‐Bermann et al., Citation2009; Howell et al., Citation2010), this was not supported in the study by Martinez‐Torteya et al. (Citation2009). Unlike the prior two studies, Martinez‐Torteya et al. (Citation2009) used a control group, which consisted of preschool children who had not been exposed to IPV. This enabled the authors to distinguish between factors which promote positive outcomes in all children, and those that hold an additional protective value within the context of IPV exposure. These discrepant findings, along with the established relationship between parenting and child outcomes (Whittle et al., Citation2014) suggest that parenting might be a resource factor. That is, it plays an important role in promoting positive emotional‐behavioural outcomes in all children, rather that holding a unique protective role following IPV exposure.

Results from this review demonstrated preliminary evidence of the protective roles of maternal warmth and sensitivity, emotional coaching, and attachment, all of which represent an aspect of the mother–child relationship (Cohodes et al., Citation2017; Johnson & Lieberman, Citation2007; Katz et al., Citation2008; Manning et al., Citation2014; Owen et al., Citation2009; Skopp et al., Citation2007). However, there was some variability in these findings. Specifically, studies by Johnson and Lieberman (Citation2007) and Owen et al. (Citation2009) both provided support for the protective role of mother–child attachment. However, in the study by Owen et al., only child and not maternal reports of the quality of attachment were significant. This inconsistent finding highlighted concerns around the reliability of parent‐report measures, which can be biased by the parent's own psychological state (Ordway, Citation2011).

The use of emotion coaching techniques and maternal awareness of the child's emotional experience were found to be associated with emotional‐behaviour resilience in children exposed to IPV across three studies encompassing both preschool‐ and school‐aged children (Cohodes et al., Citation2017; Johnson & Lieberman, Citation2007; Katz et al., Citation2008). Although all three studies has small sample sizes (N = 30–95), these finding have implications for intervention development as research suggests that emotion coaching as a technique can be taught effectively through individual and group parenting programs (Chronis‐Tuscano et al., Citation2016; Havighurst et al., Citation2012). Consequently, future research could aim to determine the efficacy of emotion coaching programs in promoting positive outcomes in children exposed to IPV.

There has been less of a focus on individual child factors, which might promote resilience. Several researchers (e.g., Bowen, Citation2017; Martinez‐Torteya et al., Citation2009) provided substantial evidence for the role of temperament across two large community samples of preschool‐aged children. This construct was operationalised differently across the two studies with Bowen (Citation2017) assessing a number of different components of temperament (e.g., emotionality, activity, and shyness) across gender rather than using a combined ease of temperament variable (Martinez‐Torteya et al., Citation2009). These results demonstrated that a child's temperament impacts how they adjust following exposure to IPV, however, more research is needed to determine what specific characteristics of temperament are particularly protective for this group of children.

Child race/ethnicity was also assessed within the literature with 4 of the 15 studies including it in their analysis (Bowen, Citation2017; Howell et al., Citation2010; Martinez‐Torteya et al., Citation2009; McDonald et al., Citation2016). Only results from McDonald et al. (Citation2016) were significant. In this study, Latino children were less likely to display emotional‐behaviour difficulties following IPV. This finding highlighted the influence of one's cultural context in determining responses to risk and adversity. This was also the only study to examine ethnicity in school‐aged children. By consequence, it may be that the protective role of ethnicity for children exposed to IPV increases as children get older and begin to form their identity (Molix & Bettencourt, Citation2010). The inconsistencies present in assessing ethnicity also highlight the need for a more nuanced approach when considering the influence of ethnicity and culture on developmental outcomes.

Many inconsistencies were noted throughout the literature and point to areas for future investigation. For example, contrary to expectation, evidence was presented for higher levels maternal education as a risk factor for children exposed to IPV with another study finding in‐home family supports was protective only when maternal education levels were low (Miller et al., Citation2014). The authors of these articles pointed to the need for longitudinal research to explore this relationship between maternal education and outcomes in children exposed to IPV. Additionally, just two studies assessed any aspect of partner involvement. Partner warmth was found to be a risk factor for children's externalising behaviour in one study (Skopp et al., Citation2007), with no significant association found between partner involvement in childcare activities and child's emotional‐behaviour adjustment in another (Bowen, Citation2017). These are important contributions to field of literature and future research which builds on this, could inform parenting programs targeting fathers who have used violence with relationships.

Overall, only one study investigated the role of a single community factor associated with resilience in children exposed to IPV. Consequently, this review cannot conclude what community level factors might promote resilience. However, in this study, Georgsson et al. (Citation2011) found that children who were not involved in the judicial system had higher levels of emotional‐behavioural functioning than those who were involved in this system. Given this study included just 22 participants, these findings are not generalisable to the wider population. Community factors might be particularly important when looking at school‐aged children who spend more time outside of the family home. The role of child care accessibility, support from school, involvement in the community, as well as access to primary health services in promoting resilience in this population could be explored in future studies.

Limitations and future directions

This review highlighted that the majority of included studies took place within America. It is likely that cultural and community responses to IPV influence the complex relationship between exposure to IPV and child outcomes. Subsequently, it is unclear whether these results are generalisable to other socio‐cultural environments. Furthermore, many included studies might have underestimated the significance of protective factors due to a lack of statistical power (Georgsson et al., Citation2011; Howell et al., Citation2010; Johnson & Lieberman, Citation2007; Katz et al., Citation2008). Future studies should aim to include larger sample sizes which are more sensitive to these effects.

Moreover, 10 of the 15 studies recruited at least 50% of their sample from domestic violence shelters and/or community programs servicing disadvantaged populations. This is an issue present more broadly within IPV research (Holt et al., Citation2008). Such samples frequently represent children who have witnessed severe and recent abuse, community violence and other life stressors (Holt et al., Citation2008; McIntosh, Citation2003). Consequently, these samples do not capture children exposed to lower levels of IPV, or those exposed at an earlier time. Consideration must be given to these factors before generalising the results of these studies to the broader community where research has demonstrated that IPV prevalence rates remain high (Gartland et al., Citation2014).

In addition, many included studies were of cross‐sectional design. Such designs do not capture children with prior (but not current) exposure to IPV. Nor do these designs consider the impact of chronic exposure to IPV across time. Further longitudinal research is needed to determine what may be protective for children with different patterns of exposure.

The majority of the included studies relied on parent‐report of emotional‐behavioural functioning and consequently may be biased (Allen et al., Citation2003; Bowen, Citation2017; Cohodes et al., 2017; Graham‐Bermann et al., Citation2009; Howell et al., Citation2010; Insana et al., Citation2014; Johnson & Lieberman, Citation2007; Martinez‐Torteya et al., Citation2009; Miller et al., Citation2014; Owen et al., Citation2009). For instance, if the mother is finding it difficult to cope, she may perceive her child as struggling due to a negativity bias which commonly occurs when under psychological stress (Ordway, Citation2011). Future researchers should continue to include reports from other informants, including the children and teachers.

This review highlighted inconsistencies resilience measurement. Despite only reviewing studies measuring emotional‐behavioural functioning, large differences in outcomes remained. This provided a challenge when comparing results as it posed the question as to whether results of one study would remain the same if the outcome measurement of a different study was used. Research clarifying resilience definitions, operationalisation, and measurement within children, would be beneficial to increase the consistency in this area and develop a clear understanding of what might promote resilience in children exposed to IPV. In addition, further consistency within this field would increase the ease at which a meta‐analysis could be conducted. Given the current evidence around the protective role of maternal mental health, a meta‐analysis on this factor alone may be warranted.

Another important consideration is the age range of the children included in the studies. Although some studies examined a particular age (e.g., 4 years) or a narrow age range (e.g., 3–5 years), many studies included wide age range (e.g., 6–13, 7–12, 6–12-years) or crossed developmental and educational stages (e.g., 4–6, 7–11-years). This is particularly important to consider given that resilience theory postulates that vulnerabilities and protective processes vary across ages and developmental periods (Masten, Best, & Garmezy, Citation1990). Due to the age ranges utilised in these studies, the current systematic review was not able to look specifically at resilience in children within different developmental periods. Future research should aim to consider the developmental differences across stages of development and where possible assess what factors may be protective for children of certain ages. This information will allow for the development of interventions targeting children of particular developmental periods.

This review looked specifically at emotional‐behavioural resilience and factors which might promote this in children exposed to IPV. Given this, the findings cannot be generalised to other domains of resilience such as academic resilience. Only published articles were included in this analysis and therefore negative or null‐hypothesis findings might be under‐represented. A further source of bias is that only English language articles were included. However, no studies of differing languages were identified in our search. Additionally, our review did not exclude studies based on type of reporter. Consequently, it included studies with mother‐report, child‐report, and experimenter‐report. Although the majority of studies did include mother‐report, our review has not been able to take the potential influence of reporter type on results into account. Finally, human error can impact the selection of studies to be included in the analysis. To address this, two reviewers independently assessed the identified articles for eligibility.

Implications and conclusion

This study provided a systematic review on the current evidence on factors which promote emotional‐behavioural resilience and adjustment in preschool‐ and school‐aged children exposed to IPV. This evidence is an important resource for service providers working with families experiencing violence and those developing interventions for children. This review also highlighted key methodological considerations, which may help to strengthen future research in the area. Our findings highlighted support for maternal mental health as a protective factor for children exposed to IPV. This emphasises the need for mothers who have experienced IPV to receive assistance to access appropriate psychological supports and treatment to promote not only their own health and wellbeing but also that of their children. Parenting and mother–child attachment also both appear to play a protective role within this context; however, further research is needed to address current inconsistencies in this literature. This is the first known systematic review to address this growing area. It has highlighted that there is currently limited available evidence about what assists children to adapt and cope when exposed to IPV. This knowledge is essential in guiding clinical and community interventions which assist children and families to maintain good health, wellbeing, and development despite this adversity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

A,.F. received support through an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

Author contribution

All authors of this research have reviewed and significantly contributed to this article.

REFERENCES

- Achenbach, T. M., & Edelbrock, C. (1993). Manual for the child behavior checklist and revised child behavior profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont.

- Allen, N. E., Wolf, A. M., Bybee, D. I., & Sullivan, C. M. (2003). Diversity of children's immediate coping responses to witnessing domestic violence. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 3(1–2), 123–147. https://doi.org/10.1300/J135v03n01_06

- Bogat, G. A., Dejonghe, E., Levendosky, A. A., Davidson, W. S., & von Eye, A. (2006). Trauma symptoms among infants exposed to intimate partner violence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30(2), 109–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.09.002

- Bowen, E. (2015). The impact of intimate partner violence on preschool children's peer problems: An analysis of risk and protective factors. Child Abuse & Neglect, 50, 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.09.005

- Bowen, E. (2017). Conduct disorder symptoms in pre‐school children exposed to intimate partner violence: Gender differences in risk and resilience. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 10(2), 97–107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-017-0148-x

- Chronis‐tuscano, A., Lewis‐morraty, E. L., Woods, K. E., O'brien, K. A., Mazursky‐horositz, H., & Thomas, S. R. (2016). Parent–child interaction therapy with emotion coaching for preschoolers with attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 23(1), 62–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.11.001

- Cohodes, E., Chen, S., & Lieberman, A. (2017). Maternal meta‐emotion philosophy moderates effect of maternal symptomatology on preschoolers exposed to domestic violence. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(7), 1831–1843.

- Conduct Problem Prevention Research Group. (2002). Psychometric properties of the social competence scale‐ teacher and parent ratings. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University.

- Epstein, M. H., Harniss, M. K., Pearson, N., & Ryser, G. (1999). The behavioral and emotional rating scale: Test‐retest and inter‐rater reliability. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 8(3), 319–327.

- Flach, C., Leese, M., Heron, J., Evans, J., Feder, G., Sharp, D., & Howard, L. M. (2011). Antenatal domestic violence, maternal mental health and subsequent child behaviour: A cohort study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 118(11), 1383–1391. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03040.x

- Gartland, D., Woolhouse, H., Mensah, F. K., Hegarty, K., Hiscock, H., & Brown, S. J. (2014). The case for early intervention to reduce the impact of intimate partner abuse on child outcomes: Results of an Australian cohort of first‐time mothers. Birth, 41(4), 374–383.

- Georgsson, A., Almqvist, K., & Broberg, A. G. (2011). Dissimilarity in vulnerability: Self‐reported symptoms among children with experiences of intimate partner violence. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 42(5), 539–556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-011-0231-8

- Giallo, R., Woolhouse, H., Gartland, D., Hiscock, H., & Brown, S. (2015). The emotional–behavioural functioning of children exposed to maternal depressive symptoms across pregnancy and early childhood: A prospective Australian pregnancy cohort study. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(10), 1233–1244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-014-0672-2

- Goodman, R. (2001). Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(11), 1337–1345.

- Graham‐bermann, S. A., Gruber, G., Howell, K. H., & Girz, L. (2009). Factors discriminating among profiles of resilience and psychopathology in children exposed to intimate partner violence (IPV). Child Abuse & Neglect, 33(9), 648–660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.01.002

- Graham‐bermann, S. A., & Hughes, H. M. (2003). Intervention for children exposed to interparental violence (IPV): Assessment of needs and research priorities. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 6(3), 189–204.

- Hamby, S. L., Finkelhor, D., Turner, H. A., & Ormod, R. K. (2011). Children's exposure to intimate partner violence and other forms of family violence: Nationally representative rates among US youth. OJJDP Juvenile Justice Bulletin‐ NCJ 232272. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

- Havighurst, S. S., Wilson, K. R., Harley, A. E., Kehoe, C. E., Afron, D., & Prior, M. R. (2012). “Tuning into kids”: Reducing young children's behavior problems using emotion coaching parenting program. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 44, 247–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-012-0322-1

- Holt, S., Buckley, H., & Whelan, S. (2008). The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people: A review of the literature. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32(8), 797–810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.02.004

- Howell, K. H., Graham‐bermann, S. A., Czyz, E., & Lilly, M. (2010). Assessing resilience in preschool children exposed to intimate partner violence. Violence and Victims, 25(2), 150–164.

- Insana, S. P., Foley, K. P., Montgomery‐downs, H. E., Kolko, D. J., & Mcneil, C. B. (2014). Children exposed to intimate partner violence demonstrate disturbed sleep and impaired functional outcomes. Psychological Trauma Theory Research Practice and Policy, 6(3), 290–298. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033108

- Johnson, V. K., & Lieberman, A. F. (2007). Variations in behavior problems of preschoolers exposed to domestic violence: The role of mothers' attunement to children's emotional experiences. Journal of Family Violence, 22, 297–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-007-9083-1

- Katz, L. F., Hunter, E., & Klowden, A. (2008). Intimate partner violence and children's reaction to peer provocation: The moderating role of emotion coaching. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(4), 614–621. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012793

- Kitzmann, K. M., Gaylord, N. K., Holt, A. R., & Kenny, E. D. (2003). Child witnesses to domestic violence: A meta‐analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(2), 339–352. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.71.2.339

- Luthar, S. S., Cicchetti, D., & Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71(3), 543–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00164

- Manning, L. G., Davies, P. T., & Cicchetti, D. (2014). Interparental violence and childhood adjustment: How and why maternal sensitivity is a protective factor. Child Development, 85(6), 2263–2278. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12279

- Martinez‐torteya, C., Anne bogat, G., von Eye, A., & Levendosky, A. A. (2009). Resilience among children exposed to domestic violence: The role of risk and protective factors. Child Development, 80(2), 562–577. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01279.x

- Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56(3), 227–238.

- Masten, A. S., Best, K. M., & Garmezy, N. (1990). Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Development and Psychopathology, 2(4), 425–444.

- Masten, A. S., & Cicchetti, D. (2010). Developmental cascades. Development and Psychopathology, 22(3), 491–495.

- Mcdonald, S. E., Corona, R., Maternick, A., Ascione, F. R., Williams, J. H., & Graham‐bermann, S. A. (2016). Children's exposure to intimate partner violence and their social, school, and activities competence: Latent profiles and correlates. Journal of Family Violence, 31(7), 849–864. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-016-9846-7

- Mcintosh, J. (2003). Children living with domestic violence: Research foundations for early intervention. Journal of Family Studies, 9(2), 219–234. https://doi.org/10.5172/jfs.9.2.219

- Miller, L. E., Vanzomeren‐dohm, A., Howell, K. H., Hunter, E. C., & Graham‐bermann, S. A. (2014). In‐home social networks and positive adjustment in children witnessing intimate partner violence. Journal of Family Issues, 35(4), 462–480. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X13478597

- Molix, L., & Bettencourt, B. A. (2010). Predicting well‐being among ethnic minorities: Psychological empowerment and group identity. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40(3), 513–533.

- Ordway, M. R. (2011). Depressed mothers as informants on child behavior: Methodological issues. Research in Nursing & Health, 34(6), 520–532. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20463

- Owen, A. E., Thompson, M. P., Shaffer, A., Jackson, E. B., & Kaslow, N. J. (2009). Family variables that mediate the relation between intimate partner violence (IPV) and child adjustment. Journal of Family Violence, 24(7), 433–445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-009-9239-2

- Skopp, N. A., Mcdonald, R., Jouriles, E. N., & Rosenfield, D. (2007). Partner aggression and children's exteneralising problems: Maternal and partner warmth as protective factors. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(3), 459–467. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.21.3.459

- Straus, M. A. (1979). Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The conflict tactics (CT) scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 41, 75–88.

- Straus, M. A., Hamby, S. L., Boney‐mccoy, S., & Sugarman, D. B. (1996). The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2) development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues, 17(3), 283–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251396017003001

- Von elm, E., Altman, D. G., Egger, M., Pocock, S. J., Gøtzsche, P. C., & Vandenbroucke, J. P. (2008). The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology [STROBE] statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Gaceta Sanitaria, 22(2), 144–150. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0213-91112008000200011

- Whittle, S., Simmons, J. G., Dennison, M., Vijayakumar, N., Schwartz, O., Yap, M. B. H., … Allen, N. B. (2014). Positive parenting predicts the developmental of adolescent brain structure: A longitudinal study. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 8, 7–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2013.10.006

- Wolfe, D. A., Crooks, C. V., Lee, V., Mcintyre‐smith, A., & Jaffe, P. G. (2003). The effects of children's exposure to domestic violence: A meta‐analysis and critique. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 6(3), 171–187. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024910416164

- Woolhouse, H., Gartland, D., Hegarty, K., Donath, S., & Brown, S. J. (2012). Depressive symptoms and intimate partner violence in the 12 months after childbirth: A prospective pregnancy cohort study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 119(3), 315–323. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03219.x

- World Health Organization. (2013). Understanding and addressing violence against women: Intimate partner violence. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/77432/1/WHO_RHR_12.36_eng.pdf

- Wright, M. O., Masten, A. S., & Narayan, A. J. (2005). Resilience processes in development: Four waves of research on positive adaption in the context of adversity. In S. Goldstein & R. B. Brooks (Eds.), Handbook of resilience in children (2nd ed., pp. 15–37). New York, NY: Springer.