Abstract

Objectives

Despite regularly reporting high levels of occupational stress, lawyers are an under‐researched group in this field. The first objective of this research is to develop a short measure assessing two common work stress management techniques (WSMS) commonly employed by lawyers: relaxation and cognitive restructuring. A second objective is to assess the impact of three key job characteristics and two work stress management techniques upon levels of psychological strain, job satisfaction, and work engagement in a sample of lawyers.

Method

Drawing on the Job Demands Control‐Support theoretical explanation of occupational stress, we assessed the impact of the two stress management techniques upon three key psychological outcomes, in comparison with three common job characteristics. An anonymous survey was administered to lawyers employed in one Australian state and produced a respondent sample of N = 114.

Results

Confirmatory factor analysis produced acceptable psychometric results for the six‐item WSMS. Hierarchical multiple regression analyses indicated that job demands was not directly associated with any of the three criterion variables. Importantly, cognitive restructuring was as strongly associated with job satisfaction and work engagement, compared to the three job characteristics. Cognitive restructuring techniques were also associated with high levels of work engagement even when experiencing high job demands.

Conclusions

The implications for occupational stress experienced by lawyers, the current popularity of occupational resilience and organisational wellness programs, and the assessment of generic job characteristics are all discussed.

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS TOPIC

Three common generic antecedents of occupational stress are job demands, job control, and job support.

The costs of stress are increasing, costing the Australian economy an estimated $15 billion per annum.

Lawyers are under‐represented in stress research, but report high rates of depression, alcoholism, drug abuse, burnout, divorce, and poor physical health.

WHAT THIS TOPIC ADDS

An empirical assessment of occupational stress experienced by a sample of Australian lawyers.

A new psychometrically sound measure of two common stress management techniques.

The importance of using cognitive restructuring stress management in periods of high job demands.

INTRODUCTION

Recent reports indicate that experiences of occupational stress are increasing for many groups of workers, while the costs of managing employees experiencing stress and the financial consequences of occupational stress claims continue to rise in many countries, including Australia (Safe Work Australia, Citation2013). A recent review described occupational stress as a “sizeable financial burden on society” (Hassard, Teoh, Visockaite, Dewe, & Cox, Citation2018, p. 1). A second recent review reported that occupational stress journal articles have increased steadily in number since 2002; indicative of the increased interest and developments within this field (Bliese, Edwards, & Sonnentag, Citation2017). The key demographical, technological, societal, and financial reasons for this steady increase in occupational stress experiences by a wide range of workers have been reported (e.g., Brough, O'Driscoll, Kalliath, Cooper, & Poelmans, Citation2009), while more effective strategies to assist workers to better manage their stress experiences are emerging (e.g., Biggs, Brough, & Barbour, Citation2014a). Recent attention has turned to the groups of high‐risk workers who remain under‐represented within scholarly discussions of occupational stress, and one of these groups, and the focus of this article, is lawyers.

In this article, we adopt the definition of stress described by Kalliath, Brough, O'Driscoll, Manimala, Siu, and Parker (Citation2014, p. 229): “stress is best described as a dynamic, interactive process that occurs between a person and his or her environment.” This definition of stress is based on the widely employed definition described by Lazarus and Folkman (Citation1984) within their theoretical transactional explanation of stress. Both these definitions of stress emphasise the importance of an individual's cognitive perceptions in the experience of stress, as opposed to simple objective capacity. The impact of occupational stress experienced by lawyers has only comparatively recently been reported. Reports indicate, for example, high rates of depression, alcoholism, drug abuse, divorce, and poor physical health are commonly experienced by lawyers (Bergin & Jimmieson, Citation2013; Di Stefano, Citation2010). Marcus (Citation2014) reported above average levels of suicide for Australian legal professionals, with an estimated 10% of lawyers regularly contemplating suicide. Similar to other criminal justice occupations, chronic occupational stress experienced by lawyers is associated with toxic work environments, work‐life imbalance, and high levels of turnover (Brough, Brown, & Biggs, Citation2016; Omari & Paull, Citation2013; Seligman, Verkuil, & Kang, Citation2004). For example, from their sample of 384 Australian lawyers, Bergin and Jimmieson (Citation2014) reported that 49% reported symptoms of clinical stress, 37% demonstrated moderate to severe depression, 31% reported high anxiety, 28% reported high levels of job dissatisfaction, and 35% reported regular excessive alcohol intake. These figures are generally comparable with similar research assessing lawyer's occupational stress originating in both the United States and Europe (Brough et al., Citation2016; Rhode & Paton, Citation2002; Seto, Citation2012).

Management of occupational stress

The fundamental tripartite model describing the three common approaches to stress management interventions (SMIs) is 30 years old, but in the absence of any effective replacements (bar updates) remains a relevant theoretical explanation (Murphy, Citation1988; Murphy & Sauter, Citation2003). Murphy's (Citation1988) tripartite model divides SMIs into practices focused on job re‐design, improving levels of employee resilience (e.g., coping skills training), and counselling provisions. Recent research has answered long‐standing calls for effective job re‐design SMIs, primarily focused on reducing the job demands and/or increasing levels of job support available to workers (e.g., Biggs et al., Citation2014a; Biron & Karanika‐Murray, Citation2014; Brough & Biggs, Citation2015a; Brough & O'Driscoll, Citation2010). Similarly, the current popularity of “occupational resilience” research focuses on improving levels of employee well‐being, primarily via training to improve a worker's coping abilities to better withstand their work stressors (Crane, Citation2017; Hegney et al., Citation2018). Scholarly discussions have also reflected this renewed interest in the provision of organisational stress management programs. For example, Richardson and Rothstein's (Citation2008) meta‐analysis of SMIs, identified the two most common SMI components as being cognitive‐behavioural and relaxation techniques. Importantly, Richardson and Rothstein (Citation2008) reported that SMIs consisting of cognitive‐behavioural techniques had the largest effect sizes and were the most effective methods for managing occupational stress. However, relaxation techniques were included more frequently in the SMIs as compared to cognitive‐behavioural techniques, despite their reduced impact on occupational stress experiences. Richardson and Rothstein (Citation2008) suggested the relative ease (and low cost) of including a relaxation component within a SMI is the central reason for their popularity. Similarly, in their meta‐analysis, Parks and Steelman (Citation2008) identified that employee participation in these programs was associated with lower rates of absenteeism and higher rates of job satisfaction. Importantly, both reviews identified the need for further evaluations of the impact of SMIs and this call has been reinforced more recently (Brough, Drummond, & Biggs, Citation2018; Richardson, Citation2017).

Occupational resilience training currently commonly includes the application of two skills: relaxation and cognitive restructuring (Richardson, Citation2017). Relaxation techniques (e.g., meditation, deep‐breathing, or muscle relaxation) aim to assist employees in creating a physical and/or mental state to reduce the physiology of stress (Buckley, Brough, & Westaway, Citation2018). Cognitive restructuring also has a long history of association with occupational stress management. For example, Maddi, Kahn, and Maddi (Citation1998) demonstrated that training 54 managers in hardiness (i.e., toughness, resilience), was effective in improving their abilities to cope with their experiences of occupational stress and increased levels of both work engagement and job satisfaction. The relative ease of adoption of these skills within organisational training programs, is contributing to the current growth in organisational wellness programs, albeit with a varied quality of wellbeing assessments.

A final pertinent issue is the measurement of relaxation techniques and cognitive restructuring skills. This field is currently dominated by the clinical/therapeutical/physical processes of training individuals in relaxation techniques and cognitive restructuring skills. Subjective assessments of an individual's frequency of use of these skills are currently not available. Consequently, one objective of the current research is to develop and validate an occupational stress management measure, specifically focused on the two most common stress management components: relaxation and cognitive restructuring skills. This measure will be included in assessments of occupational stress to estimate three common outcomes: psychological strain, job satisfaction, and work engagement. We therefore, propose:

Hypothesis 1: The work stress management scale developed by this research will demonstrate acceptable psychometric characteristics (i.e., validity and reliability).

Hypothesis 2: Both relaxation and cognitive restructuring will each be negatively associated with psychological strain and positively associated with both job satisfaction and work engagement.

Influential job characteristics

Specific inherent job characteristics directly contribute to the occupational stress experienced by lawyers, with a key characteristic being the meeting of financial targets, also referred to as the “payment by results regime” (Brough et al., Citation2016, p. 214). Bergin and Jimmieson (Citation2014) called for Australian law practices to recognise that time‐billing targets contributed to high levels of occupational stress experienced by lawyers, and that if this job characteristic cannot be changed, then improved management of the stress it produces is required. Other key job characteristics common to many criminal justice occupations, including lawyers, are high social status and opportunities to contribute to a better community (Brough et al., Citation2016). However, the large discrepancy between new graduate expectations of these job characteristics and their experienced reality has been widely documented (Castan, Paterson, Richardson, Watt, & Dever, Citation2010). This discrepancy is recognised as a source of occupational stress in the early years of employment for many criminal justice workers, including lawyers.

Other influential job characteristics contributing to occupational stress experienced by lawyers are generic to many occupations, and are included as causal factors within theoretical explanations of occupational stress. Three common job characteristics are job demands, job control, and job support, which are widely reported as influencing employee's levels of mental health and job performance both directly and in combination (i.e., interaction effects; Job Demands Control Support [JDCS] model; Johnson & Hall, Citation1988). In a recent review of 60 articles reporting SMIs, Burgess, Brough, Biggs, and Hawkes (Citationin press) identified the JDC(S) as one of the most commonly utilised theoretical explanation of occupational stress. Research has repeatedly reported how a lack of control over job content and work hours, and inadequate levels of supervisor support are each associated with high levels of psychological strain and decreased work motivation for lawyers (Seligman et al., Citation2004). Similarly, in an assessment based on the Job Demands‐Resources model (Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner, & Schaufeli, Citation2001), Bergin and Jimmieson (Citation2014) reported differences between these levels of job characteristics experienced by junior and senior lawyers. Junior lawyers reported lower levels of job control, job support, and higher levels of job demands and stress, when compared to senior lawyers. There is also evidence of the impact of these three job characteristics on long‐term employee health and performance outcomes (i.e., job satisfaction and work engagement) for workers within other sectors of the criminal justice system, including police and corrections workers (Biggs et al., Citation2014a; Brough et al., Citation2018; Brough & Biggs, Citation2015b). Therefore, in accordance with this literature, it is proposed:

Hypothesis 3: Job demands will be positively associated with psychological strain, and negatively associated with both job satisfaction and work engagement (H3a). Both job control and job support will each be negatively associated with psychological strain and positively associated with both job satisfaction and work engagement (H3b).

Hypothesis 4: The relationships between job demands and each criterion variable will be reduced (moderated) by the influence of job control (H4a), job support (H4b), cognitive restructuring (H4c), and relaxation (H4d), respectively.

The current research

The current research seeks to address the under‐representation of lawyers in scholarly discussions of occupational stress via the investigation of two research objectives. First, we assess the influence of key job characteristics, and the use of relaxation and cognitive restructuring, upon the mental health and job performance of a sample of Australian lawyers. This article contributes to the recent discussions of stress management and occupational resilience by developing and validating a measure of stress management. The measure is intended to specifically assess the subjective use of relaxation techniques and cognitive restructuring skills. Second, based on the JDCS theoretical explanation of occupational stress, we assess how three key job characteristics (job demands, job control, and job support) directly impact three common dependent variables (psychological strain, job satisfaction, and work engagement) in a sample of lawyers. We offer a unique contribution to current SMIs discussions, by assessing the degree to which the use of relaxation and cognitive restructuring techniques reduces (moderates) the impact of job demands upon these three outcomes.

METHOD

Participants and procedure

Research ethics approval for this research was obtained from the university. Samples of lawyers employed in one Australian state were invited to participate in this research. Participants were invited via the membership lists (approximately 10,600 members) of the state law society to complete an anonymous self‐report survey administered in both online and hard‐copy formats. A total of N = 114 completed surveys were returned directly to the university researchers. The respondents were mostly female (n = 79, 69%) and ranged in age from 22 to 77-years (M = 36-years, SD = 11). Years since admission to the legal profession ranged from 4 months to 52-years (M = 10 years, SD = 10.68). Most respondents were employed on a full‐time basis (n = 101, 89%) and specialised in family, commercial, personal injury, or civil law (n = 58, 51%). The majority of the respondents were solicitors employed in private practices (n = 71, 62%) and who worked between 9 and 90-hr per week (M = 46-hr, SD = 11.67).

Measures

Job characteristics variables

Job demands and job control

Job demands and job control were assessed with Wall, Jackson, and Mullarkey's (1995) job characteristics measure. The job demands subscale consists of nine items, including “Are you required to deal with problems, which are difficult to solve?” The job control subscale consists of 10 items, including “Do you decide on the order in which you do things?” Participants responded on a 5‐point scale (1 = not at all and 5 = a great deal). High scores indicate high levels of both job demands and job control. Both subscales demonstrated high levels of internal reliability (Cronbach's alpha): job demands of 0.84 and job control of 0.95.

Job support

The supervisor support subscale of Caplan, Cobb, French, Van Harrison, and Pinneau's (1980) job social support measure was included as the third job characteristic variable in this research. Four items ask the extent to which practical and emotional support is received from immediate supervisors. An example item is “How easy is it to discuss your problems with your immediate supervisor?” Responses are recorded on a 5‐point scale (1 = don't have such a person and 5 = very much), with high scores indicative of high levels of work support. The scale demonstrated high levels of internal reliability (Cronbach's alpha: 0.94).

Stress management variables

Work stress management scale

The six‐item work stress management scale was developed by the researchers to assess how frequently participants employed cognitive‐restructuring and relaxation strategies to assist them in managing their experiences of occupational stress.

Item generation and pilot testing

Scale items were informed by the literature and from interviews with lawyers and occupational stress‐management subject matter experts (full details are described in Boase, 2015). The original scale consisted of eight‐items and was pilot tested with a convenience sample of 21 respondents (primarily consisting of people within the legal industry). Respondents provided feedback on the clarity of wording of the scale items (i.e., face validity), the suitability of the response scale, and the length of time required to complete the measure. Minor revisions to the scale items were conducted based on this feedback. This eight‐item scale was subject to exploratory factor analysis (EFA) described below, from which two items were deleted.

The measure was included in the full survey and was subject to detailed structure analysis (results described below). Example items include: “I use deep breathing” (relaxation) and “I turn negative thoughts into positive statements” (cognitive restructuring). Frequency of use responses were recorded on a 7‐point scale (1 = never to 7 = always), with high scores indicating more frequent use of each stress management technique. The two factors of the resultant six‐item measure each demonstrated high levels of internal reliability (Cronbach's alphas): 0.87 (cognitive restructuring) and 0.84 (relaxation).

Dependent variables

Psychological strain

Psychological strain was assessed with Goldberg's (1972) 12‐item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ). Items were prefaced with the stem: “Have you recently experienced the following in the past few weeks …” and an example item was “been feeling unhappy or depressed?” Responses were recorded on a frequency scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (much more than usual), so high scores represent high levels of strain. Cronbach's alpha coefficients were 0.92 in this study.

Work engagement

Work engagement was measured using the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale‐9 (UWES‐9; Schaufeli, Bakker, & Salanova, 2006). An example item is “My job inspires me” and responses are scored on a 7‐point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (every day). High scores indicate high levels of work engagement. The scale demonstrated high levels of internal reliability (Cronbach's alpha): 0.92.

Job satisfaction

Finally, job satisfaction was measured with Warr, Cook, and Wall's (1979) 15‐item subscale assessing satisfaction with 15 job features. An example item is “The amount of variety in your job”. Participants responded on a 7‐point scale (1 = extremely dissatisfied and 7 = extremely satisfied). High scores indicate high levels of satisfaction. The scale demonstrated high levels of internal reliability: 0.94.

RESULTS

Structure of the work stress management scale

Statistical analyses were conducted with the IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 25, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). To test Hypothesis 1, the psychometric properties of the WSMS were assessed by two methods. First, an exploratory principal component analysis (PCA) of the initial eight‐item measure was tested on one third (n = 38) of the total sample. The PCA sample is small and offers a subject‐to‐item ratio of 4:1. Costello and Osborne (Citation2005) noted that 41% of published articles which included exploratory factor analyses, were based on subject‐to‐item ratios of between 2:1 and 5:1. The results of the PCA revealed the presence of two factors with eigenvalues exceeding 1 and accounting for 60% of the total variance. Specifically, component 1 accounted for 32.53% and component 2 accounted for 26.60% of the variance in the data. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy value was 0.76 and Bartlett's test of sphericity reached statistical significance, supporting the factorability of the correlation matrix. Oblimin rotation was performed to assist in the interpretation of these two components. The rotated solution indicated strong loadings for the two components. The PCA results were presented in full in Boase (2015). In consideration of the small sample size, it is important to note that the PCA results did not produce evidence of either of the two “indicators of extreme trouble” (Costello & Osborne, Citation2005, p. 7). That is neither the presence of Heywood cases (factor loadings greater than 1.0) nor a failure to converge, were observed.

Second, this factor structure was assessed via confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in AMOS (version 23; Arbuckle, 2014), in the remaining two thirds of the sample (n = 76). This ensures that the exploratory and confirmatory structural analyses are conducted on separate “independent” samples. The splitting of the data into two groups consisting of one third and two thirds of the respondents was informed by Woods (Citation2019); see also Brough, O'Driscoll, & Kalliath, Citation2005). The CFA sample is small; however, given the number of free model parameters, the model does meet recommendations to avoid saturation (Goodboy & Kline, Citation2017). Hu and Bentler's (Citation1998) recommended two‐index presentation strategy for the reporting of goodness‐of‐fit statistics was adopted (i.e., the inclusion of the chi‐square statistic and other alternative fit indices). Five alternative fit statistics, plus the chi‐square statistic, are reported to overcome any effects of sample size, misspecifications or other violations of assumptions represented by each individual fit statistic (Brough et al., Citation2014; Yang, Citation2019).

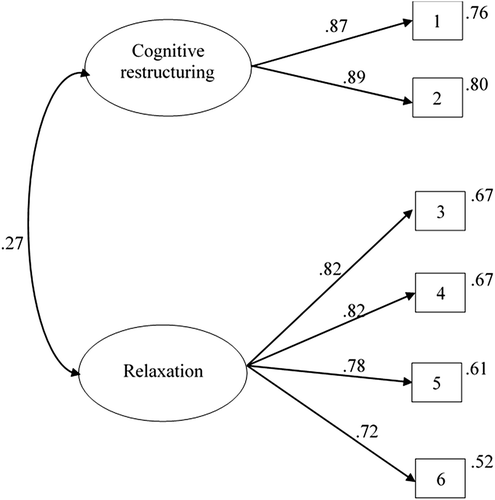

The CFA results are presented in Table . The PCA solution (Model A in Table ) produced a number of low‐squared multiple correlations (R2) for several items, indicating that only a small proportion of variance in these items is accounted for by their respective factor. To improve the psychometric properties of the WSMS without altering the factor structure, the items with low R2 were deleted from the analysis. Model changes were conducted individually, in a cumulative format, and each subsequent model was examined for improved statistical fit. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) was utilised to confirm that each new model was an improvement on the previous model. Optimum results were produced by the final Model C (six items) and this solution is illustrated in Figure 1. The fit indices indicated that the measure had a good fit to the data: the TLI and CFI estimates exceeded 0.95 and the SRMR estimates were low (0.04; Yang, Citation2019). In consideration of the small sample size, the 8° of freedom produced by Model C is indicative that the model was not over‐identified (Goodboy & Kline, Citation2017). Figure 1 illustrates that the six WSMS items accounted for acceptable proportions of variance (square multiple correlations [R2] greater than 0.30). The internal reliability estimates (Cronbach's alpha) for each factor were also acceptable, as was noted above (supporting Hypothesis 1).

Table 1. Goodness‐of‐fit statistics for the confirmatory factor analysis models (N = 76)

Harman's single‐factor test and descriptive statistics

To test for common method variance (CMV), we conducted Harman's (Citation1967) single‐factor test in SPSS. This analysis identifies whether a general factor emerges from the data and accounts for most of the covariance among the measures (Siu et al., Citation2015). All the research items were entered in a factor analysis with un‐rotated principal axis factoring. If a substantial amount of CMV is present, a single factor will emerge from the factor analysis, or one general factor will account for the majority of the covariance among variables. The results produced 14 factors each with an eigenvalue greater than 1. The 14 un‐rotated factors together accounted for 76.63% of variance, suggesting that CMV was not of a great concern and was unlikely to significantly confound the interpretations of the results.

Table presents the bivariate correlations, means, SDs, and internal consistencies for the research variables. As expected job demands were significantly positively related to work hours and psychological strain; and negatively related to job satisfaction. Job control demonstrated a significant negative association with strain, and significant positive associations with both work engagement and job satisfaction. Supervisor support was also significantly positively associated with both work engagement and job satisfaction. Interestingly, none of these three key job characteristics variables demonstrated a significant association with either of the two WSMS factors. Relaxation was significantly and positively association with strain, while cognitive restructuring was significantly and positively association with both work engagement and job satisfaction (supporting Hypothesis 1), offering support for the construct validity of the WSMS.

Table 2. Means, SDs, correlations, and reliability coefficients (N = 114)

Hierarchical moderated multiple regression analyses

To test Hypotheses 2–4, assessing the associations of the job characteristics variables and the two WSMS factors upon the three dependent variables, three hierarchical moderated multiple regression analyses were constructed, with the whole dataset (N = 114). At Step 1, the direct effects of job demands, job control, and supervisor support were assessed. At Step 2, the direct effects of the two WSMS factors (relaxation and cognitive restructuring) were tested. Finally, at Step 3, interaction terms between job demands and the two other job characteristic variables and the two WSMS variables were tested to assess any moderation effects. The interaction terms were calculated via the multiplication of the respective standardised predictor and moderator variables. Given the small sample size, separate regression equations were constructed to test moderations involving (a) the three job characteristic variables and (b) the two WSMS variables. Results indicated non‐significant findings for the interactions of the three job characteristic variables and hence demonstrate no support to Hypotheses 4a and 4b. A summary of the equations depicting the significant interaction terms for job demands with the two WSMS variables are presented in Table .

Table 3. Hierarchical moderated multiple regression analyses predicting psychological strain, work engagement, and job satisfaction (N = 114)

In the prediction of psychological strain, job control and relaxation were the only predictor variables to demonstrate significant main effects. Relaxation produced a positive association with strain, which was contrary to the direction hypothesised in Hypothesis 2. High levels of job control were associated with lower level of psychological strain, partly supporting Hypothesis 3b. The interaction terms entered in Step 3 were not significant. The regression equation overall accounted for 30% of variance; F(7, 106) = 6.63, p < 0.001.

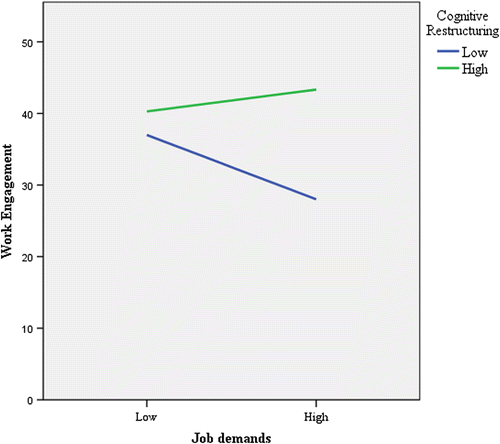

In the prediction of work engagement, the predictors of job control, supervisor support, and cognitive restructuring each produced significant and positive results; partly supporting Hypotheses 2 and 3b. The interaction term of job demands × cognitive restructuring (Hypothesis 4c) was significant and is illustrated in more detail in Figure 2. From Figure 2 it can be observed that both high and low levels of cognitive restructuring have a similar impact on levels of work engagement when job demands are low. However, when job demands are high, respondents employing cognitive restructuring more frequently have better outcomes (an increase in work engagement), while those respondents using less cognitive restructuring report decreases in work engagement. The regression equation overall accounted for 32% of variance; F(7, 103) = 4.12, p < 0.001.

Finally, in the prediction of job satisfaction, the predictors of job control, supervisor support, and cognitive restructuring each again produced significant and positive direct effects; partly supporting Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3b. Neither of the interaction terms entered into the equation at Step 3 were significant; offering no support for Hypothesis 4. The regression equation overall accounted for 48% of variance; F(7, 104) = 13.95, p < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

This research had two primary research objectives: (a) to develop and validate a measure assessing the use of two stress management techniques employed by lawyers; and (b) to assess the impact of these stress management techniques upon three key psychological outcomes, in comparison with three common job characteristics.

Work stress management scale

The results demonstrated the first research objective was successfully achieved and thus supported Hypothesis 1. A six‐item, two‐factor measure of two common stress management techniques was developed by this research and was found to have acceptable psychometric properties. The two factors describe relaxation and cognitive restructuring techniques frequently employed to manage occupational stressors (the measure is described in full in the Appendix). The WSMS measure demonstrated acceptable psychometric characteristics and was significantly associated with two of the dependent variables, partly supporting Hypothesis 1. Specifically, the cognitive restructuring subscale was positively associated with work engagement and job satisfaction, within both the correlation and multiple regression analyses. Relaxation was significantly associated with psychological strain within both the correlation and multiple regression analyses. These results offer some support to the reported respective associations between these two stress management techniques and similar outcome measures (Parks & Steelman, Citation2008; Richardson & Rothstein, Citation2008). Consequently, the measure is recommended for use in future research.

Given the lack of similar measures, it is suggested that this WSMS measure will be a useful addition to assessments of occupational stress management. Valid and accessible tools such as this WSMS, encourage the inclusion of robust assessments of all areas relating to psychological wellbeing, by the instigators of organisational wellness programs. These wellness programs appear to be enjoying a prolific period of growth, and typically focus on the person‐orientated methods to enable employees to better resist stress (i.e., resilience; Hegney et al., in press). It is noticeable that despite scholarly calls for improved stress interventions (e.g., Bliese et al., Citation2017; Brough & Biggs, Citation2015a), and recognition of the increasing costs of occupational stress (Hassard et al., Citation2018), it remains relatively rare for organisations to undertake systematic job‐orientated stress interventions, despite these being recognised as the best opportunity to actually reduce stress experiences for workers (Biggs et al., Citation2014a; Murphy, Citation1988). In comparison, the lower cost of organisational wellness programs certainly has corporate appeal. The WSMS is therefore, offered here as an effective tool to consider for inclusion in evaluations of organisational wellness programs. The need for more effective evaluations of organisational interventions has been recently recognised (e.g., Brough et al., Citation2016). It is hoped that empirical data produced by such measures as the WSMS included in evaluations of these organisational wellness programs, will assist in demonstrating the value (or otherwise) of these programs.

Impact upon psychological strain, work engagement, and job satisfaction

A second major contribution of the current research is the comparison between established job characteristics widely recognised as influencing psychological strain and work attitudes, and variables associated with stress management techniques. The results demonstrated that cognitive restructuring was significantly associated with both job satisfaction and work engagement, and accounted for approximately similar proportions of unique variance as compared to three common job characteristics (job demands, job control, and supervisor support). Furthermore, the regression results demonstrated that the relationship between job demands and work engagement was moderated by cognitive restructuring: respondents using cognitive restructuring more frequently reported increased levels of work engagement during periods of high job demands. Respondents who did not use cognitive restructuring to assist in managing their high workloads, experienced reduced levels of work engagement.

This result, indicating that cognitive restructuring moderates the relationship between job demands and work engagement, is an interesting finding and contributes to current scholarly discussions concerning the role of personal resources within the occupational stress process (e.g., Biggs, Brough, & Barbour, Citation2014b; Freedy & Hobfoll, Citation2017). For example, Chan et al. (Citation2017) demonstrated that employees who are actively encouraged to utilise their personal resources are better positioned to cope with their job and family demands. Through an application of the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, Citation1989), Chan et al. (Citation2017) demonstrated the COR's principle of resource gain spirals; that is, how employees seek to obtain, retain, and protect their resources in order to manage their role demands and attain wellbeing. While a significant proportion of this scholarly discussion is focused on the identification of innate resources which best alleviate job demands (e.g., Brough et al., Citation2018), the current research is instrumental in connecting these discussions with the SMI literature. The findings of the current research demonstrate that employees can employ personal resources (e.g., cognitive restructuring) obtained from stress management training, for example, and that this resource acts in a similar way as established resources (i.e., job control and supervisor support) to relieve the negative impact of job demands. It appears to be intuitive that employees with more available resources, are better able to manage the negative impact of occupational stress, and this is the principal spiral‐gains theory of the COR model (Hobfoll, Citation1989). The current research demonstrated that when experiencing high levels of job demands the active use of cognitive restructuring, is a preferred and effective option for managing this occupational stress. Thus, perhaps it is not the quantity of resources available to individuals which is important, but rather their opportunity to actively use a single effective resource to manage their stress experiences, which has more of an impact (see also, van Woerkom, Bakker, & Nishii, Citation2016).

Interestingly, relaxation demonstrated a small but significant positive association with psychological strain, but did not moderate any impact of the job characteristics upon strain. The reasons why techniques such as mediation, muscle relaxation, and deep breathing should be positively, rather than negatively, associated with levels of psychological strain appears to be counter‐intuitive, and requires further investigation. It is plausible that the use of these relaxation skills primarily occurs during high‐stress experiences (e.g., deep breathing) and/or by individuals regularly perceiving high levels of work stress (e.g., mediation); thereby generating a positive relationship with strain. That is, relaxation techniques are utilised when respondents experience strain. Equally, given the variation in psychological strain reported by this research, the relationship between relaxation and strain could differ for respondents reporting high and low levels of strain. This issue of “dilution” of impact was, for example, recently identified in a longitudinal assessment of stress management training in a sample of government workers. After controlling for baseline strain levels, Flaxman and Bond (Citation2010, p. 347) reported “meaningful effects were found only among a subgroup of initially distressed workers.” The small sample achieved by the current research precludes any meaningful difference testing, but we do note that over half our sample (55%) scored above the GHQ threshold (of 1); indicative of high strain. Clearly, further work is required with a larger sample than we achieved here, to more accurately assess the relationship between relaxation and psychological strain. The benefits of dividing respondents into high and low strain groups, as well as adopting a longitudinal research design to test the impact of relaxation on distal strain outcomes, are highly recommended for future research in this field.

Job control, rather than job demands, was the only job characteristic to demonstrate a significant association with psychological strain in the regression results. Although unexpected, other reports of non‐significant direct effects between job demands and psychological strain have been reported. Brough and Biggs (Citation2015b), for example, noted that assessments of job demands that are specifically focused on the work conducted by the respondent sample, demonstrate stronger associations compared to generic measures of job demands. This reasoning is supported by research which has included lawyer‐specific assessments of job demands (e.g., interpersonal challenges, bullying, and excessive billing targets) and reported significant associations between these job demands and psychological strain (Omari & Paull, Citation2013; Tsai, Huang, & Chan, Citation2009). We acknowledge that such lawyer‐specific assessments of job demands would have been valuable to include in the current research. We do also recognise, however, that other research has reported significant associations between generic measures of job demands and psychological strain with samples of lawyers (e.g., Bergin & Jimmieson, Citation2015). Clearly, lawyers similar to many other professions, experience both generic and specific job demands. Assessments of lawyer's occupational stress experiences should ideally therefore, include both types of job demands, in order to more accurately determine the impact of work upon lawyers' levels of mental health (Brough & Biggs, Citation2014). We also recognise the value of assessing different types of job demands such as cognitive, challenge, and hindrance demands which has also recently been recommended (Brough et al., Citation2018).

Research limitations

One limitation to the research reported here is its cross‐sectional research design, which hinders any discussion of causality. The difficulties experienced in obtaining the current sample prohibited any inclusion of a longitudinal research design, but we acknowledge this requires more consideration and creativity during the research design stage (see, e.g., Brough & Hawkes, Citation2019). We also acknowledge the value of replication (i.e., to test concurrent validity and test–retest reliability) of the WSMS within research adopting a longitudinal research design and with a larger sample (e.g., Woods, Citation2019; Yang, Citation2019). Such research would, for example, provide further clarity on the association between relaxation and subsequent levels of psychological strain. We do suggest, however, that the scarcity of occupational stress research focused on lawyers ensures the relevance of this article. Second, the study was based on self‐reports, which may raise questions of common method bias (e.g., Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003). While self‐report is an appropriate research design to assess the subjective experiences of occupational stress, the potential for bias in the single‐source data requires consideration. The results from the Harman's single‐factor test were indicative that CMV was not a major problem in this study.

Finally, a third limitation is the low response rate achieved by this research. Despite numerous sampling efforts, we acknowledge that our research sample of N = 114 lawyers is an extremely low representation of the state's solicitor population (of approximately 10,600 solicitors). It is possible, for example, that the non‐respondents may experience higher levels of occupational stress (a common reason for non‐responses to surveys) compared to the research respondents; subsequently the results of this study may underestimate levels of psychological strain (Brough et al., Citation2016). The small sample size directly restricted the statistical analyses reported in this article. Although minimal thresholds for both the PCA and CFA analyses were met, we acknowledge the necessity to validate the WSMS with large, independent samples. Again, strategies to encourage research recruitment from lawyer populations should be considered further, including, for example, consideration of offering participant payments. Strategies to enhance participation are especially relevant for future research adopting longitudinal research designs.

Conclusion

This article addressed two research objectives. First, we answered calls to explain the over‐representation of lawyers in occupational health statistics reporting high levels of job dissatisfaction, depression, alcoholism, burnout, and marital breakdowns (Bergin & Jimmieson, Citation2014; Marcus, Citation2014). Second, we developed and validated a measure of work stress management (WSMS) assessing the use of two common stress management techniques: relaxation and cognitive restructuring. The results indicated that cognitive restructuring was as strongly associated with job satisfaction and work engagement, compared to three core generic job characteristics (job demands, supervisor support, and job control). Cognitive restructuring techniques were associated with high levels of work engagement even during periods of high job demands. The use of relaxation techniques demonstrated a positive association with strain and therefore, requires further assessment within longitudinal research designs to clarify its influence.

REFERENCES

- Arbuckle, J. L. (2014). Amos (Version 23.0) [Computer Program]. Chicago: IBM SPSS.

- Bergin, A. J., & Jimmieson, N. L. (2013). Explaining psychological distress in the legal profession: The role of overcommitment. International Journal of Stress Management, 20(2), 134–161. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032557

- Bergin, A. J., & Jimmieson, N. L. (2014). Australian lawyer well‐being: Workplace demands, resources and the impact of time‐billing targets. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 21(3), 427–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2013.822783

- Bergin, A. J., & Jimmieson, N. L. (2015). Interactive relationships among multiple dimensions of professional commitment: Implications for stress outcomes in lawyers. Journal of Career Development, 42(6), 493–510. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845315577448

- Biggs, A., Brough, P., & Barbour, J. (2014b). Relationships of individual and organizational support with engagement: Examining various types of causality in a three‐wave study. Work and Stress, 28(3), 236–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2014.934316

- Biggs, A., Brough, P., & Barbour, J. P. (2014a). Enhancing work‐related attitudes and work engagement: A quasi‐experimental study of the impact of an organizational intervention. International Journal of Stress Management, 21, 43–68. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034508

- Biron, C., & Karanika‐murray, M. (2014). Process evaluation for organizational stress and well‐being interventions: Implications for theory, method, and practice. International Journal of Stress Management, 21(1), 85–111. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033227

- Bliese, P. D., Edwards, J. R., & Sonnentag, S. (2017). Stress and well‐being at work: A century of empirical trends reflecting theoretical and societal influences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(3), 389–402. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000109

- Brough, P., & Biggs, A. (2014). Comparing the impact of occupation‐specific and generic work characteristics. In M. Dollard, A. Shimazu, R. Bin nordin, P. Brough, & M. Tuckey (Eds.), Psychosocial factors at work in the Asia Pacific (pp. 145–159). London, England:: Springer.

- Brough, P., & Biggs, A. (2015a). The highs and lows of occupational stress intervention research: Lessons learnt from collaborations with high‐risk industries. In M. Karanika‐murray & C. Biron (Eds.), Derailed organizational stress and well‐being interventions: Confessions of failure and solutions for success (pp. 263–270). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

- Brough, P., & Biggs, A. (2015b). Job demands x job control interaction effects: Do occupation‐specific job demands increase their occurrence? Stress and Health, 31(2), 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2537

- Brough, P., Brown, J., & Biggs, A. (2016). Improving criminal justice workplaces: Translating theory and research into evidenced‐based practice. London, England: Routledge.

- Brough, P., Drummond, S., & Biggs, A. (2018). Job support, coping and control: Assessment of simultaneous impacts within the occupational stress process. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(2), 188–197. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000074

- Brough, P., & Hawkes, A. (2019). Designing impactful research. In P. Brough (Ed.), Advanced research methods for applied psychology: Design, analysis, and reporting (pp. 7–14). London, England: Routledge.

- Brough, P., & O'driscoll, M. (2010). Organizational interventions for balancing work and home demands: An overview. Work and Stress, 24, 280–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2010.50680

- Brough, P., O'driscoll, M., & Kalliath, T. (2005). Confirmatory factor analysis of the cybernetic coping scale. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78, 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317904X23754

- Brough, P., O'driscoll, M., Kalliath, T., Cooper, C. L., & Poelmans, S. (2009). Workplace psychological health: Current research and practice. Cheltenham, England: Edward Elgar.

- Brough, P., Timms, C., O'driscoll, M., Kalliath, T., Siu, O. L., Sit, C., & Lo, D. (2014). Work‐life balance: A longitudinal evaluation of a new measure across Australia and New Zealand workers. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(19), 2724–2744. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2014.899262

- Buckley, R. C., Brough, P., & Westaway, D. (2018). Bringing outdoor therapies into mainstream mental health. Frontiers in Public Health, 6, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2016.00257

- Burgess, M. G., Brough, P., Biggs, A., & Hawkes, A. J. (in press). Why interventions fail: A systematic review of occupational health psychology interventions. International Journal of Stress Management.

- Castan, M., Paterson, J., Richardson, P., Watt, H., & Dever, M. (2010). Early optimism? First‐year law students' work expectations and aspirations. Legal Education Review, 20(1), 1–11.

- Chan, X. W., Kalliath, T., Brough, P., O'driscoll, M. P., Siu, O. L., & Timms, C. (2017). Self‐efficacy and work engagement: Test of a chain model. International Journal of Manpower, 38(6), 819–834. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-11-2015-0189

- Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. W. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 10(7), 1–9.

- Crane, M. F. (2017). Managing for resilience: A practical guide for employee wellbeing and organizational performance. London, England: Taylor & Francis.

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands‐resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512.

- Di stefano, G. (2010). Courting the blues: Attitudes towards depression in Australian law students and legal practitioners. Bulletin (Law Society of South Australia), 32(4), 18–26.

- Flaxman, P. E., & Bond, F. W. (2010). Worksite stress management training: Moderated effects and clinical significance. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(4), 347–358. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020522

- Freedy, J., & Hobfoll, S. E. (2017). Conservation of resources: A general stress theory applied to burnout. In W. B. Schaufeli, C. Maslach, & T. Marek (Eds.), Professional burnout: Recent developments in theory and research (pp. 115–129). London, England: Routledge.

- Goodboy, A. K., & Kline, R. B. (2017). Statistical and practical concerns with published communication research featuring structural equation modeling. Communication Research Reports, 34(1), 68–77.

- Harman, D. (1967). A single factor test of common method variance. Journal of Psychology, 35, 359–378.

- Hassard, J., Teoh, K. R. H., Visockaite, G., Dewe, P., & Cox, T. (2018). The cost of work‐related stress to society: A systematic review. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2017.1380726

- Hegney, D., Craigiea, M., Slatyera, S., Heritage, B., Harvey, C., Rees, C., & Brough, P. (2018). Mindful self‐care and resiliency (MSCR): Protocol for the development and evaluation of a brief mindfulness pilot intervention to promote occupational resilience. BMJ Open, 8(6), e021027.

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524.

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modelling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3, 424–453.

- Johnson, J., & Hall, E. (1988). Job strain, work place social support and cardiovascular disease: A cross‐sectional study of a random sample of the working population. American Journal of Public Health, 78, 1336–1342.

- Kalliath, T., Brough, P., O'driscoll, M., Manimala, M., Siu, O. L., & Parker, S. (2014). Organisational behaviour: A psychological perspective for the Asia‐Pacific (2nd ed.). Melbourne, Australia: McGraw‐Hill Publishers.

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. New York, NY: Springer.

- Maddi, S. R., Kahn, S., & Maddi, K. L. (1998). The effectiveness of hardiness training. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 50(2), 78–85.

- Marcus, C. (2014). Lawyers' alarming depression rates prompt efforts to boost mental health support. Retrieved from http://www.abc.net.au/news/2014‐2011‐2021/lawyers‐depression‐rates‐alarming/5903660.

- Murphy, L. R. (1988). Workplace interventions for stress reduction and prevention. In C. L. Cooper & R. Payne (Eds.), Causes, coping, and consequences of stress at work (pp. 301–339). New York, NY: Wiley.

- Murphy, L. R., & Sauter, S. L. (2003). The USA perspective: Current issues and trends in the management of work stress. Australian Psychologist, 38, 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050060310001707157

- Omari, M., & Paull, M. (2013). ‘Shut up and bill’: Workplace bullying challenges for the legal profession. International Journal of the Legal Profession, 20(2), 141–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/09695958.2013.874350

- Parks, K. M., & Steelman, L. A. (2008). Organizational wellness programs: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 13, 58–68. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.13.1.58

- Rhode, D. L., & Paton, P. D. (2002). Lawyers, ethics, and Enron. Stanford Journal of Law, Business & Finance, 8, 9–38.

- Richardson, K. M. (2017). Managing employee stress and wellness in the new millennium. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 423–428. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000066

- Richardson, K. M., & Rothstein, H. R. (2008). Effects of occupational stress management intervention programs: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 13, 69–93. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.3.1.69

- Safe Work Australia. (2013). The incidence of accepted workers compensation claims for mental stress in Australia (Publication No. 978‐0‐642‐78719‐4). Retrieved from http://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au

- Seligman, M. E. P., Verkuil, P. R., & Kang, T. H. (2004). Why lawyers are unhappy. Deakin Law Review, 10(1), 49–66.

- Seto, M. (2012). Killing ourselves: Depression as an institutional, workplace and professionalism problem. The University of Western Ontario Journal of Legal Studies, 2(2), 1–25. Retrieved from http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/uwojls/vol2/iss2/5

- Siu, O. L., Bakker, A. B., Brough, P., Lu, J. Q., Wang, H., O'driscoll, M., … Timms, C. (2015). A three‐wave study of antecedents of work‐family enrichment: The roles of social resources and affect. Stress and Health, 31, 306–314. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2556

- Tsai, F.‐J., Huang, W.‐L., & Chan, C.‐C. (2009). Occupational stress and burnout of lawyers. Journal of Occupational Health, 51(5), 443–450. https://doi.org/10.1539/joh.L8179

- van Woerkom, M., Bakker, A. B., & Nishii, L. H. (2016). Accumulative job demands and support for strength use: Fine‐tuning the job demands‐resources model using conservation of resources theory. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(1), 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000033

- Woods, S. A. (2019). Instrumentation). In P. Brough (Ed.), Advanced research methods for applied psychology: Design, analysis, and reporting (pp. 46–60). London, England: Routledge.

- Yang, Y. (2019). Structural equation modelling. In P. Brough (Ed.), Advanced research methods for applied psychology: Design, analysis, and reporting (pp. 246–258). London, England: Routledge.

APPENDIX A WORK STRESS MANAGEMENT SCALE

What techniques do you use to cope with work stress? These techniques might be used either at work or at home, with the purpose of reducing the experience of work stress. Please indicate how often you use these techniques.