Abstract

Objective

Youth mental health problems have been identified as a major public health concern. However, there are a number of parent populations that remain under‐engaged with face‐to‐face parenting programs, which include fathers, and parents of lower socioeconomic position and rural location. This review aimed to evaluate the evidence for technology‐assisted parenting programs for youth mental health and parenting outcomes; as well as the extent to which they engage underserved parent populations and how they can be better tailored for these groups in an Australian context.

Methods

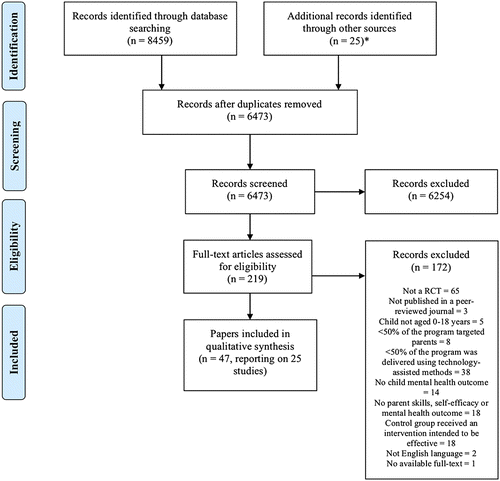

Employing the PRISMA method, we conducted a systematic review of randomised controlled trials of technology‐assisted parenting programs for youth mental health problems.

Results

We identified 43 articles that met inclusion criteria, consisting of 25 randomised controlled trials along with 8 and 10 articles describing intervention development and follow‐up, respectively. Some evidence was found to support the use of technology‐assisted parenting programs, particularly to improve externalising problems and parenting skills. Additionally, program development and recruitment strategies to engage underserved parents were under‐utilised among studies reviewed.

Conclusions

Findings from this review indicate that technology‐assisted parenting programs may present an effective alternative to traditional face‐to‐face programs. However, more comprehensive and evidence‐based strategies are required for program development and recruitment to capitalise on the advantages of technology‐assisted programs to enhance engagement with underserved parent populations. Further research should investigate program attributes and engagement strategies for diverse parent populations.

Funding information Australian Research Council; National Health and Medical Research Council, Grant/Award Number: APP1061744

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS TOPIC?

Parenting programs can improve youth mental health and parenting outcomes.

Certain parent populations are under‐engaged in traditional (i.e., face‐to‐face) parenting programs.

Technology‐assisted programs have been identified as an alternative means of intervention delivery, which minimise many of the barriers to engagement present for traditional parenting programs.

WHAT THIS TOPIC ADDS?

A comprehensive update on the effectiveness of technology‐assisted parenting programs for improving youth mental health and parenting outcomes.

Evidence‐based strategies can be used to enhance engagement with underserved parent populations, however, these strategies are largely underused or misused.

Practitioners can utilise technology‐assisted programs to improve youth mental health and parenting outcomes, particularly externalising behaviours and parenting skills, however a comprehensive engagement strategy may be required when targeting underserved Australian parent populations.

INTRODUCTION

Mental health difficulties are a leading cause of disability in children and adolescents worldwide, with one in four young people experiencing a mental disorder during their lifetime (Patel, Flisher, Hetrick, & McGorry, Citation2007; World Health Organization, Citation2016). Australian youth aged 4 to 17-years‐old have a 12‐month prevalence of 14% for mental disorders (Lawrence et al., Citation2015). These mental health problems are commonly associated with adverse long‐term experiences, including developmental, social and health‐related impairments, exposure to stigma and discrimination, and increased suicide risk (Copeland, Shanahan, Costello, & Angold, Citation2009; Lawrence et al., Citation2015; Patel et al., Citation2007). In youth, these mental health problems are typically classified into two major clusters: internalising problems, which are characterised by cognitive and behavioural inhibition, and externalising problems, which feature impulsive or over‐reactive behaviours (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Untreated, these problems can lead to substantial emotional and economic costs to individuals, families and communities (Copeland, Miller‐Johnson, Keeler, Angold, & Costello, Citation2007; Fox, Halpern, & Forsyth, Citation2008; McCauley, Katon, Russo, Richardson, & Lozano, Citation2007). As such, national and international bodies have called for a greater focus on the prevention and treatment of mental health difficulties for all communities (Commonwealth of Australia, Citation2009; World Health Organization, Citation2013).

The role of parenting in addressing youth mental health problems

Families, particularly parents, are an important and strategic early intervention target for youth mental health, with youth referring to individuals aged 0 to 18 years. As well as being viewed by their children as a primary source of support for mental health difficulties (Yap, Reavley, & Jorm, Citation2013), parents are intrinsically motivated to support their child's wellbeing, and the proximity generally shared by families offers parents the opportunity to intervene in the development and maintenance of youth mental health difficulties (Yap et al., Citation2017). Sandler, Schoenfelder, Wolchik, and MacKinnon (Citation2011) specify a conceptual framework of parenting processes to improve youth outcomes, by which three main parent factors account for long‐term effects of parenting interventions: parenting skills, parental self‐efficacy, and the removal of barriers to effective parenting, particularly parent mental health problems. There is substantial evidence to establish parenting skills—a parent's ability to respond to and support their child's developmental needs—as one of the most potent predictors of a young person's mental health (Yap & Jorm, Citation2015; Yap, Pilkington, Ryan, & Jorm, Citation2014). Moreover, parental self‐efficacy, defined as a parent's expectations about their ability to parent successfully, and parent mental health have been established as antecedents for parental competence, and act both as direct and indirect determinants of youth adjustment (Jones & Prinz, Citation2005; Moreland, Felton, Hanson, Jackson, & Dumas, Citation2016; National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, Citation2009). Although these parenting interventions are not intended as direct treatment for parent mental health or efficacy, they aim to relieve the distress associated with parenting difficulties by improving parenting confidence, knowledge, and skills, which have been shown to indirectly affect parent mental health and efficacy outcomes (e.g., Oyserman, Bybee, Mowbray, & Hart‐Johnson, Citation2005). As such, this review focussed on parents' skills, self‐efficacy and mental health for the evaluation of intervention efficacy on parent‐related factors.

Despite substantial progress in the development of effective parenting interventions for youth mental disorders, the positive impact of these interventions is often undermined by low engagement with programs and research assessments (Dumas, Moreland, Gitter, Pearl, & Nordstrom, Citation2008; Finan, Swierzbiolek, Priest, Warren, & Yap, Citation2018; Ingoldsby, Citation2010). Studies indicate that only 10–31% of eligible parents enrol to participate in face‐to‐face parenting programs, the most common form of parenting intervention (Garvey, Julion, Fogg, Kratovil, & Gross, Citation2006; Heinrichs, Bertram, Kuschel, & Hahlweg, Citation2005; Thornton & Calam, Citation2011). Furthermore, rates of program attendance are low, with parents attending between 39% and 50% of program sessions on average, while up to a third of enrolled participants do not attend a single session (Breitenstein et al., Citation2012; Garvey et al., Citation2006; Scott et al., Citation2010). As such, identifying and developing improved approaches to intervention delivery is vital in increasing the impact and accessibility of parenting programs, particularly for those most at‐risk (Sanders, Turner, & Markie‐Dadds, Citation2002).

Technology‐assisted parenting programs

The internet, mass media and other technologies have been identified as alternative means of intervention delivery that minimise many of the barriers contributing to low uptake and attendance in traditional delivery models (Baggett et al., Citation2010; Self‐Brown & Whitaker, Citation2008). Parents have reported technology‐assisted methods, such as online or via television programs, as their most preferred methods of program delivery (Metzler, Sanders, Rusby, & Crowley, Citation2012). Utilising technology to assist in the delivery of programs is advantageous as it facilitates ease of use, consistency of delivery, 24‐hr access, user autonomy, lack of waiting lists and reduced time and cost requirements for participants (Breitenstein & Gross, Citation2013; Clarke & Yarborough, Citation2013). Remote delivery of programs can also reduce the resources required by practitioners or services to implement such programs (Baggett et al., Citation2010; Gordon, Citation2000).

Despite these advantages, the field of technology‐assisted parenting interventions is relatively new. Evidence regarding how to most effectively reach parents with parenting programs is still developing, particularly for those historically underserved by traditional programs. However, with a growing rate of Australian households with internet access, reported at over 86% of Australian families and 97% of families with a child under 15-years (ABS; Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2018a), technology holds great promise. It is therefore imperative that the most effective programs and engagement strategies are established to ensure that all Australian parents are able to access suitable evidence‐based parenting programs.

For the purpose of this review, two indices of engagement with technology‐assisted parenting programs were examined: program adherence and study retention. Program adherence refers to the extent to that individuals experience the content of an intervention (Christensen, Griffiths, & Farrer, Citation2009). In the context of technology‐assisted interventions, this is indicated by the percentage of participants who adhere to the intended usage of a program, which is defined by program creators for parents to receive maximum benefit from the intervention (Kelders, Kok, Ossebaard, & Van Gemert‐Pijnen, Citation2012). Program adherence was selected as an indicator of engagement to ascertain whether intervention effects can be accounted for by the actual usage of the intervention content. Study retention describes the proportion of participants who complete all intended research assessments. Study retention is an indicator of research engagement, and is relevant to accurately estimate intervention effects in the intended population (Eysenbach, Citation2005). In the case of underserved populations, lower study retention among these groups limits knowledge of the unique needs of these populations, and impedes implementation of interventions with these groups.

Engagement of underserved groups in parenting programs

The benefits of technology‐assisted parenting interventions are particularly salient when trying to engage difficult‐to‐reach populations (Sanders & Kirby, Citation2012). These contemporary programs hold promise for many different types of parents, however this review will highlight three groups historically underserved by face‐to‐face parenting programs: parents of lower socioeconomic position (SEP), families living in rural areas, and male parents. Despite representing populations with distinct needs and barriers to accessing services (Lavigne et al., Citation2010; Sicouri et al., Citation2018), these groups have been consistently underrepresented within parenting research and among samples selected for the development and piloting of traditional parenting programs (Lundahl, Tollefson, Risser, & Lovejoy, Citation2008; McGoron & Ondersma, Citation2015). This indicates that presently, Australian parenting programs are designed and implemented without consideration for the specific parenting needs of these groups; and this underrepresentation is reflected in poorer youth mental health outcomes among rural and lower‐SEP populations (Bradley & Corwyn, Citation2002; Lawrence et al., Citation2015). To avoid inadvertently contributing to existing health inequalities, it is imperative that researchers and program developers improve efforts to address under‐engagement with these groups (Dickman, Himmelstein, & Woolhandler, Citation2017; Yap, Citation2018).

McCurdy and Daro (Citation2001) provide a framework through which to understand the impact of the underrepresentation of these groups within parenting program research. They outline four domains that influence engagement of underserved groups in parenting interventions: individual characteristics, provider factors, program factors, and neighbourhood factors. Given evidence to suggest that male, rural, and lower‐SEP parent populations experience unique individual barriers that determine their perception of the costs and benefits associated with a program (Lavigne et al., Citation2010; Tully et al., Citation2017), it is unlikely that programs informed by research that underrepresents these groups will adequately meet their specific requirements. Therefore, without consideration of the specific needs of underserved parents, the cycle of exclusion is perpetuated by current parenting intervention development and dissemination practices.

Families of lower‐SEP often have higher rates of attrition from parenting programs (Chacko et al., Citation2016), as the costs of child care and transportation associated with traditional delivery formats are more burdensome to families with fewer financial and social resources (Morawska & Sanders, Citation2006; Zubrick et al., Citation2005). Additionally, access to traditional parenting programs in rural and remote communities is limited due to geographic isolation and poor distribution of qualified professionals (National Rural Health Alliance & National Rural Health Policy Forum, Citation2002). Thus, the availability of an effective parenting program online could remove a substantial external barrier for these two groups of underserved families. Nonetheless, access to internet and technological devices favours urban, higher‐income populations, while families of lower‐SEP are more likely to access the internet using smartphones than tablets or laptop devices (Pew Research Centre, Citation2018). This highlights the need to ensure technology‐assisted parenting programs are suitable for, and accessible to, underserved populations.

Furthermore, despite evidence to suggest that parenting intervention programs that include both parents yield improved outcomes for parenting behaviours as well as disruptive youth behaviours (Bagner & Eyberg, Citation2003), male parents are less likely to feel comfortable using face‐to‐face parenting programs (Sanders, Dittman, Keown, Farruggia, & Rose, Citation2010). Barriers to engaging fathers that were most frequently cited by practitioners who implement parent training interventions include practical concerns with accessing programs or services (Tully et al., Citation2018). Additionally, Cunningham et al. (Citation2008) found that fathers were more likely than mothers to prioritise logistical concerns around accessing services and prefer to receive parenting information alone rather than in groups, while Frank, Keown, Dittman, and Sanders (Citation2015) reported that fathers' most preferred parenting program delivery methods were low intensity options, including seminars, television series, and web‐based programs. It is therefore expected that male parents are likely to benefit from the accessibility of technology‐assisted interventions, and as such, it is important to investigate the success of efforts to involve fathers in these interventions from development through to implementation.

The current systematic review

The current review will expand on previous findings by examining the efficacy of technology‐assisted parenting interventions and the engagement strategies used to increase enrolment and participation among underserved parent populations. While there are many reviews of parenting program studies (i.e., Dretzke et al., Citation2009; Sanders, Kirby, Tellegen, & Day, Citation2014; Yap et al., Citation2016), there are limited reviews investigating technology‐assisted parenting interventions. The four reviews that have been conducted either lack recent studies (Breitenstein, Gross, & Christophersen, Citation2014; Nieuwboer, Fukkink, & Hermanns, Citation2013) or focus only on youth externalising problems (Baumel, Pawar, Mathur, Kane, & Correll, Citation2017) or one developmental stage (Hall & Bierman, Citation2015). Technology‐assisted parenting programs are a rapidly growing field, with 80% or more of studies identified in past reviews conducted after 2012, indicating that an up‐to‐date review is required to account for new evidence and technologies available to deliver parenting programs (Baumel et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, extant reviews have not examined long‐term effects of the programs included, nor the use of technology‐assisted programs to overcome barriers to engaging traditionally underserved parent populations. As such, this review will be a comprehensive investigation of the efficacy of all technology‐assisted parenting intervention studies on parent and youth outcomes, and their engagement of underserved parent groups. In this review, parenting interventions will be those where more than 50% of the intervention is directed towards parents or caregivers, with the primary aim of preventing or reducing youth mental health difficulties through parental education and skill development. Additionally, programs must have targeted parents of young people aged 0 to18 years and more than 50% of the program had to be delivered via a technological platform.

Specifically, this review aims to: (a) investigate the efficacy of technology‐assisted parenting interventions on parents' skills, self‐efficacy and mental health; (b) investigate their efficacy on youth mental health outcomes; (c) explore the extent to which they engage underserved parent populations; and (d) explore how programs can be better tailored for these populations.

METHOD

Search strategy

Studies were identified through systematic searches of eight electronic databases: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Embase, Informit, ProQuest, PsychINFO, PubMed, and Scopus. The effective combination of search terms was designed and set up by two reviewers (A.H. and G.B.) according to the PRISMA statement (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, Citation2009) and different terms and rules of each database. Terms were identified on the basis of prior research and keyword searching. Specific keywords and free text terms for parenting, interventions, youth mental health, and technology assistance were used for each database (Appendix S1, Supporting Information). The last search was conducted on 12th June, 2018. Reference lists of retrieved studies were then hand‐searched between June and July 2018, and articles citing these relevant studies in Google Scholar were screened to identify any additional studies that were overlooked in the initial electronic database search. The search strategy, inclusion criteria, primary and secondary outcomes and data synthesis methods were pre‐specified, registered and published on the Prospero database (Prospero ID 2018: CRD42018095270).

Study selection

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (a) randomised controlled trial design, (b) published in a peer‐reviewed journal, (c) evaluated an intervention targeting mental health outcomes in youth aged 0 to 18-years, (d) the intervention targeted parents or caregivers in more than 50% of the program, (e) more than 50% of the program was delivered online or through technology‐assisted methods, (f) included a youth mental health outcome, (g) included a parent skills, self‐efficacy or mental health outcome, (h) the control group did not receive an intervention intended to be effective, (i) published in the English language, and (j) published between January 1993 and July 2018. For the purpose of this review, youth mental health outcomes included any measures of mental health problems in young people, defined as any dysregulation of mood, thought and/or behaviour (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013).

Screening and data extraction

One researcher (from A.H., G.B., or a research assistant) screened titles and abstracts of studies that were identified through electronic database searches, following the removal of duplicate references using Covidence v.1033 systematic review software. Full text articles of potentially relevant studies were then assessed independently by two authors (A.H. and G.B.). Discrepancies in eligibility assessment were resolved through discussion between authors.

Two researchers (A.H. and G.B.) independently extracted key study characteristics and outcomes using a standardised data extraction form that was pre‐piloted on three studies. Study characteristics included: risk of bias, country of participant population, inclusion and exclusion criteria, demographics of parent and youth participants, sample size, schedule of intervention delivery, format and description of technology‐assisted intervention component, family members who participated in the intervention, timing of intervention (i.e., youth age), type and description of comparison condition, level of intervention (e.g., universal, selective, or indicated), focus of the intervention (e.g., parenting skills, parent–child relationship etc.), and type of youth mental health outcome targeted. Study outcomes extracted included: intervention effect on youth mental health outcomes; intervention effect on parents' skills, self‐efficacy or mental health outcomes; program adherence; study retention; and post‐intervention effects at all reported time‐points.

Risk of bias

Risk of bias of each individual study was independently assessed by two authors (A.H. and G.B.). Information about potential sources of bias from each of the following domains was extracted using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (Higgins et al., Citation2011): Selection bias, including random sequence generation and allocation concealment; performance bias, including the blinding of participants and personnel; detection bias, including blinding of outcome assessment; attrition bias, including incomplete outcome data; reporting bias, including selective outcome reporting; and other bias, which can include any other observed bias not addressed in the other domains. Studies were rated as “Low,” “High,” or “Unclear” on seven possible domains of bias according to the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins, Altman, & Sterne, Citation2011).

Data synthesis

Heterogeneity in intervention features, settings, populations and outcome variables did not allow for a meta‐analysis to be conducted. As such, the results are presented in the form of a narrative synthesis. Study characteristics are detailed, including participants targeted by the programs, as well as the intervention features most commonly incorporated. The programs' efficacy is then described. Primary outcomes included youth mental health outcomes, including immediate (post‐intervention), as well as short‐ (<6 months), medium‐ (6–12-months), and long‐term (>12-months) follow‐ups post intervention where possible; and parent outcomes, including parents' skills (e.g., parental monitoring), self‐efficacy (i.e., parents' belief in their capability to perform parenting behaviours) or mental health (e.g., parental stress). Secondary outcomes included engagement measures of study retention, and program adherence. Study retention data‐collection points for follow‐up were coded into four categories post‐intervention: Short‐ (<6 months), medium‐ (6–12-months), and long‐term (>12-months), or no reported follow‐up. Finally, the strategies the study employed to increase engagement, particularly for underserved populations, were described.

RESULTS

A total of 8,459 studies were identified through initial electronic database searches, and reduced to 6,448 after removal of duplicates. The 6,448 studies were then screened by title and abstract, and reduced to 194 articles that were screened by full‐text, after which 174 were excluded for various reasons (see Figure 1). Reference lists and citations of the remaining 20 articles were hand‐searched, which revealed five additional articles that met study criteria. Further searches were conducted to identify articles that reported either (a) the development and initial evaluation of the intervention program, or (b) long‐term follow‐up of intervention outcomes, of which eight and 10 were found respectively. A final total of 43 articles were then included for review, consisting of 25 randomised controlled trials along with eight development articles and 10 reporting follow‐up outcomes. The studies have been summarised below using narrative review to describe study quality, characteristics and outcomes. The total number of “Low” bias ratings for included studies ranged from one to five out of seven domains. However, overall quality of included studies remains indeterminate due to many studies obtaining multiple unclear bias ratings (17 of the 25 studies obtained more than one unclear bias rating). A summary of risk of bias ratings for each study is presented in Table .

Table 1. Summary of risk of bias for included studies

Study characteristics

Participants

Although inclusion criteria allowed for parents of youth aged 0 to 18-years, participants of the included studies were parents or caregivers of young people who ranged in age from 12-months to 15-years. The majority of interventions catered to parents of youth aged under 5-years (n = 12, Baker et al., Citation2017; Breitenstein et al., Citation2016; Day & Sanders, Citation2018; DuPaul et al., Citation2017; Hemdi & Daley, Citation2017; MacKenzie & Hilgedick, Citation1999; Morgan et al., Citation2017; Nixon et al., Citation2003; Sanders et al., Citation2012; Sanders et al., Citation2000; Sourander et al., Citation2016; Van Zeijl et al., Citation2006). The average number of participants across studies was n = 208.60, and ranged broadly from 33 to 916 participants. Male youth were well represented across many studies, constituting more than 50% of the young people in 14 studies (Baker et al., Citation2017; Cardamone‐Breen et al., Citation2018; DuPaul et al., Citation2017; Enebrink et al., Citation2012; Hinton et al., Citation2017; Irvine et al., Citation2015; Jones et al., Citation2014; Morawska et al., Citation2014; Sanders et al., Citation2000; Sanders et al., Citation2012; Sourander et al., Citation2016; Van Zeijl et al., Citation2006; Yap et al., Citation2018), on average making up 44.6% of youth participants. In contrast, male caregivers were severely underrepresented (on average 5.0%), with only three studies including more than 10% male caregivers (Khanna et al., Citation2017; MacKenzie & Hilgedick, Citation1999; Yap et al., Citation2018). No male caregivers were primary recipients of the intervention in eight studies (Breitensteinet al., 2016; Fang et al., 2010; Hemdi & Daley, Citation2017; Sanders et al., Citation2000; Schinke et al., Citation2009a; Schinke et al., Citation2009b; Schwinn et al., Citation2014; Van Zeijl et al., Citation2006). In most studies, the majority (>50%) of the sample were educated with post‐secondary qualifications (n = 14, Baker et al., Citation2017; Cardamone‐Breen et al., Citation2018; Day & Sanders, Citation2018; DuPaul et al., Citation2017; Fang et al., Citation2010; Hemdi & Daley, Citation2017; Jones et al., Citation2014; Khanna et al., Citation2017; Morgan et al., Citation2017; Sanders et al., Citation2012; Sanders et al., Citation2000; Schinke et al., Citation2009a; Schinke et al., Citation2009b; Schwinn et al., Citation2014; Yap et al., Citation2018). While most studies did not adequately report the employment status of their participants (n = 14, DuPaul et al., Citation2017; Enebrink et al., 2012; Fang et al., Citation2010; Khanna et al., Citation2017; Kuravackel et al., Citation2018; MacKenzie & Hilgedick, Citation1999; Morawska et al., Citation2014; Morgan et al., Citation2017; Nixon et al., Citation2003; Sanders et al., Citation2000; Schinke et al., Citation2009a; Schinke et al., Citation2009a; Schinke et al., 2009b; Sourander et al., Citation2016; Van Zeijl et al., 2006), of those that did, most reported over 50% of their sample engaged in employed work of some description (n = 8, Baker et al., Citation2017; Cardamone‐Breen et al., Citation2018; Day & Sanders, Citation2018; Hinton et al., Citation2017; Irvine et al., Citation2015; Sanders et al., Citation2012; Schwinn et al., Citation2014; Yap et al., Citation2018). A detailed break‐down of participant characteristics across included studies is presented in Table .

Table 2. Summary of participant and program characteristics

Intervention

Interventions most commonly targeted parenting factors associated with externalising behaviours exclusively (n = 14, Baker et al., 2017; Breitenstein, Day & Sanders, Citation2018; DuPaul et al., 2017; Enebrink et al., Citation2012; Hemdi & Daley, Citation2017; Irvine et al., 2015; Kuravackel et al., Citation2018; MacKenzie & Hilgedick, Citation1999; Nixon et al., Citation2003; Sanders et al., 2012; Sanders et al., Citation2000; Sanders et al., Citation2000; Sourander et al., Citation2016; Van Zeijl et al., Citation2006), particularly among youth aged less than 5-years (n = 9). Of the four interventions that solely addressed internalising symptoms, one was used by parents of youth aged 3 to 6 years (Morgan et al.,2017), one by parents of youth aged 7 to 14 years (Khanna etal., 2017); and two by parents of adolescents (Cardamone‐Breen et al., 2018; Yap et al., 2018). Among the programs that targeted multiple domains of youth mental health, those that simultaneously addressed internalising and externalising symptoms (Hinton et al., 2017; Jones et al., 2014; Morawska et al., 2014) were developed primarily for parents of primary‐school aged youth. The remaining four interventions that targeted substance use behaviours and internalising symptoms were designed for parents of young people in late childhood (Schwinn et al., 2014) or early adolescence (Fang et al., 2010; Schinke et al., 2009a; Schinke et al., 2009b) or early adolescence (Schinke et al., Citation2009a; Schinke et al., Citation2009b). The majority of interventions focussed on parenting skills (n = 15, Baker et al., 2017; Breitenstein et al., 2016; Day & Sanders, 2018; DuPaul et al., 2017; Hinton et al., 2017; Irvine et al., 2015; Jones et al., 2014; Khanna et al., 2017; Kuravackel et al., 2018; Morawska et al., 2014; Morgan et al., 2017; Sanders et al., 2012; Sanders et al., 2000), while the remaining studies focussed on either the parent–child relationship (n = 5, Fang et al., 2010; Hemdi & Daley, 2017; Schinke et al., 2009a; Schinke et al., 2009b; Van Zeijl et al., 2006) or multiple domains (n = 7, Cardamone‐Breen et al., 2018; Enebrink et al., 2012; MacKenzie & Hilgedick, 1999; Nixon et al., 2003; Schwinn et al., 2014; Sourander et al., 2016; Yap et al., 2018). With regard to delivery of interventions, the most frequently utilised modes of technology were computerised interventions, in the form of internet modules (n = 10, Baker et al., 2017; DuPaul et al., 2017; Enebrink et al., 2012; Fang et al., 2010; Irvine et al., 2015; Jones et al., 2014; Khanna et al., 2017; Sanders et al., 2012; Schwinn et al., 2014; Yap et al., 2018). A number of interventions made use of multi‐modal technological delivery (n = 5, Day & Sanders, 2018; Hinton et al., 2017; Morgan et al., 2017; Nixon et al., 2003; Sourander et al., 2016), while others made use of computer, tablet or phone applications (n = 4, Breitenstein et al., 2016; Schinke et al., 2009a; Schinke et al., 2009b; MacKenzie & Hilgedick, 1999). Most commonly, the technology functioned to facilitate self‐directed learning (n = 17, Baker et al., 2017; Breitenstein et al., 2016; Cardamone‐Breen et al., 2018; DuPaul et al., 2017; Enebrink et al., 2012; Fang et al., 2010; Irvine et al., 2015; Jones et al., 2014; Khanna et al., 2017; MacKenzie & Hilgedick, 1999; Morawska et al., 2014; Sanders et al., 2012; Sanders et al., 2000; Schinke et al., 2009a; Schinke et al., 2009b; Schwinn et al., 2014; Yap et al., 2018) or remote therapist contact (n = 2, Hemdi & Daley, 2017; Kuravackel et al., 2018). Five interventions incorporated concurrent self‐directed learning and remote therapist contact (Day & Sanders, 2018; Hinton et al., 2017; Morgan et al., 2017; Nixon et al., 2003; Sourander et al., 2016). Refer to Table 2 for further details of intervention characteristics.

Intervention efficacy (primary outcomes)

Table presents an overview of study characteristics along with main findings for intervention efficacy across youth mental health symptoms and parent outcomes (parents' skills, self‐efficacy and mental health). Main findings are presented at post‐intervention—measured at conclusion of the intervention administration period; and at follow‐up—measured at any point following post‐intervention data collection when the control group is still available for comparison. Youth mental health outcomes are grouped and presented by measures of internalising and externalising problems. Studies that measured substance use behaviours have been discussed separately, as these are considered distinct from the internalising and externalising clusters (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). All measures are parent‐report unless otherwise indicated.

Table 3. Summary of study results for youth and parent outcomes

Parent

Immediate (post‐intervention) outcomes

Most included studies reported some degree of improvement in parents' skills, self‐efficacy or mental health, compared to a control condition. Among 19 studies that reported measures of parenting skills, outcomes were inconsistent. Twelve studies reported improved parenting skills across all measured outcomes compared to waitlist control (WLC; Cardamone‐Breen et al., 2018; Day & Sanders, 2018; DuPaul et al., 2017; Enebrink et al., 2012; Jones et al., 2014; Khanna et al., 2017; Morawska et al., 2014; Sanders et al., 2012), care as usual (CAU; Hinton et al., 2017), education/attention control (EC; Sourander et al., 2016; Van Zeijl et al., 2006), or no intervention control (NI; Fang et al., 2010). One study did not report any improvements in parent‐reported parenting skills compared to WLC (Sanders et al., 2000). The remaining six studies reported significant improvements relative to WLC (Baker et al., 2017; Irvine et al., 2015; Nixon et al., 2003), NI (Schinke et al., 2009b; Schwinn et al., 2014), or EC (Yap et al., 2018) on at least one measure of parenting skills, but not on all measured outcomes. Nine studies reported parent mental health outcomes, of which eight targeted externalising symptoms and one targeted both substance use behaviours and internalising symptoms. The majority of these reported no improvements in parent mental health outcomes, which included depression, anxiety, stress, anger, and substance use symptoms (Baker et al., 2017; DuPaul et al., 2017; Kuravackel et al., 2018; Sanders et al., 2000; Schwinn et al., 2014; Sourander et al., 2016), compared to NI, WLC or EC. Only one study (Nixon et al., 2003) reported significant improvements relative to WLC across all measured parent mental health outcomes. Day and Sanders (2018) found significant improvements in all measured parent mental health outcomes relative to WLC in an in an enhanced, telephone supported condition, which included depression, anxiety, stress and anger. However, these improvements relative to WLC were found only for stress and anger in a self‐directed condition where telephone support was not provided. The remaining two studies reported significant improvements in at least one measure of parent mental health relative to WLC (Sanders et al., 2012) or CAU (Hemdi & Daley, 2017), but not other outcomes measured. Eight studies reported parent self‐efficacy outcomes, of which five reported improved outcomes relative to WLC (Irvine et al., 2015; Nixon et al., 2003; Sanders et al., 2012; Sanders et al., 2000) or CAU (Hinton et al., 2017), and one did not report improved outcomes relative to WLC (Kuravackel et al., 2018). Baker et al. (2017) and Morawska et al. (2014) reported inconsistent outcomes across different measures of parent self‐efficacy compared to WLC no improvements in parent depression, anxiety and stress symptoms compared to WLC, but did find improvements in parental anger. Finally, two studies (Hemdi & Daley, Citation2017; Nixon et al., Citation2003) found improvements in parent‐reported happiness, as well as stress, anxiety and depression symptoms.

Eight studies reported parental self‐efficacy outcomes, of which five reported improved outcomes relative to CAU (Hinton et al., Citation2017) or WLC (Irvine et al., Citation2015; Nixon et al., Citation2003; Sanders et al., Citation2000; Sanders et al., Citation2012), and one did not report improved outcomes relative to WLC (Kuravackel et al., Citation2018). Baker et al. (Citation2017) and Morawska et al. (Citation2014) reported inconsistent outcomes across different measures of parental self‐efficacy compared to WLC.

Short‐term (<6‐months) follow‐up outcomes

Only seven studies reported short‐term follow‐up parent outcomes, of which four targeted externalising behaviours (Breitenstein et al., 2016; Day & Sanders, 2018; Hemdi & Daley, 2017; MacKenzie & Hilgedick, 1999), two targeted internalising symptoms (Cardamone‐Breen et al., 2018; Morgan et al., 2017), and one targeted substance use behaviours and internalising symptoms (Schwinn et al., 2014). Two studies (Breitenstein et al., 2016; Schwinn et al., 2014) reported significant improvements in only some of the parent skills outcomes that were measured at 24‐weeks and 5‐months, respectively. Cardamone‐Breen et al. (2018) reported improvements in parent‐reported, but not adolescent‐reported, parenting skills compared to WLC at 3‐month follow‐up. Nonsignificant findings for parent self‐efficacy and mental health outcomes compared to EC were reported by Breitenstein et al. (2016) at 24‐weeks. Post‐intervention parental depression, anxiety, stress and happiness outcomes reported by Hemdi and Daley (2017; significant improvement relative to CAU, with the exception of parent anxiety) were maintained at short‐term follow‐up. Post‐intervention findings across parenting skills and mental health outcomes were maintained at 5‐month follow‐up for Day and Sanders (2018), with the exception of depression, stress and anger in the self‐directed treatment condition. Finally, Morgan et al. (2017) reported no significant improvements in parenting skills relative to WLC at 24‐weeks, whilst MacKenzie and Hilgedick (1999) only reported improvements in one measure of parenting skills relative to NI at 1‐month.

Medium‐term (6–12‐month) follow‐up outcomes

Four studies reported medium‐term follow‐up outcomes (Baker et al., 2017; Sanders et al., 2012; Schinke 2009b; Sourander et al., 2016). Post‐intervention parenting skills outcomes were maintained for three studies (Baker et al., 2017; Sanders et al., 2012; Sourander et al., 2016). Significant improvements across all measured parenting skills outcomes were found by Schinke et al. (2009b) at 1‐year follow‐up, which was consistent with youth‐reported, but not parent‐reported, post‐intervention findings. Three studies reported parent mental health outcomes (Baker et al., 2017; Sanders et al., 2012; Sourander et al., 2016), all of which were maintained from post‐intervention with the exception of Sanders et al. (2012), which reported significant improvement in parental stress at 6‐month follow‐up, but not post‐intervention. Two studies reported significant improvements in measures of parent efficacy relative to WLC (Baker et al., 2017; Sanders et al., 2012) at 9‐months and 6‐months, respectively. These improvements were all consistent with post‐intervention findings, with the exception of one self‐report measure from Baker et al., (2017).

Long‐term (>12‐month) follow‐up outcomes

Long‐term parent follow‐up outcomes were reported by three studies (Fang et al., 2010; Schinke et al., 2009a; Sourander et al., 2016). Sourander et al. (2016) reported significant improvements in parenting skills but not mental health outcomes relative to EC at 24‐months, which were retained from post‐intervention and 12‐month follow‐up. Fang et al. (2010) and Schinke et al. (2009a) reported significant improvements relative to NI in all measured parenting skills and mental health outcomes at 2‐years. The findings of Fang et al. (2010) at 2‐year follow‐up were consistent with those at post‐intervention.

Youth

Immediate (post‐intervention) outcomes

Among technology‐assisted parenting interventions targeting youth externalising behaviours, findings at post‐intervention were inconsistent across studies. All interventions that exclusively targeted externalising behaviours were administered to parents of youth aged 0–12-years, Interventions for externalising disorders that combined self‐directed learning and remote therapist contact (Day & Sanders, 2018; Nixon et al., 2003; Sourander et al., 2016) reported significant reductions on at least one measure of parent‐rated externalising behaviours compared to their respective control conditions, which included WLC and EC. Two studies described an intervention that exclusively relied on remote therapist contact (Hemdi & Daley, 2017; Kuravackel et al., 2018), both significantly reducing the number of parent‐rated youth externalising behaviours compared to CAU and WLC, respectively. Varied results were observed among the six studies examining interventions for externalising behaviours based purely on self‐directed learning. Three studies reported improvements in all parent‐reported externalising behaviours compared to WLC (Enebrink et al., 2012; Sanders et al., 2012; Sanders et al., 2000) and two studies reported significant changes in at least one measures of parent‐reported externalising behaviours compared to WLC (DuPaul et al., 2017; Irvine et al., 2015). Finally, Baker et al. (2017) reported no significant improvements in parent‐reported externalising behaviours relative to WLC. Three interventions targeted substance use behaviours and internalising symptoms among youth in late childhood or early adolescence, of which two reported a significant reduction in alcohol use relative to NI (Fang et al., 2010; Schinke et al., 2009b) and one did not (Schwinn et al., 2014). Schinke et al. (2009b) further reported significant reductions in prescription medication use, but not marijuana or cigarettes; whilst Fang et al. (2010) reported significant reductions in marijuana and prescription medication use, but not cigarettes. One of these three studies (Fang et al., 2010) reported significant improvements in internalising symptoms relative to NI, whilst the other two did not. Three studies implemented interventions that targeted youth internalising symptoms (Khanna et al., 2017; Morgan et al., 2017; Yap et al., 2018), which reported mixed outcomes. Khanna et al. (2017) and Yap et al. (2018) reported no significant improvements in internalising symptoms compared to WLC and EC, respectively. Whereas, Morgan et al. (2017) reported significant improvements in all but one measures of youth internalising symptoms, compared to WLC.

Short‐term (<6 month) follow‐up outcomes

Intervention effects on youth mental health outcomes were varied at short‐term follow‐up. Both Breitenstein et al. (2016) and MacKenzie and Hilgedick (1999) reported no significant reductions in externalising symptoms compared to EC and NI at 24‐weeks and 1‐month, respectively. Hemdi and Daley (Citation2017) reported improved symptoms relative to CAU group at 8‐weeks, consistent with results reported at post‐intervention. Of two studies that reported short‐term outcomes for interventions targeting internalising symptoms, one maintained improvements in all but one youth internalising measure compared to WLC (Morgan et al., 2017), while one reported no change in parent‐ or adolescent‐reported anxiety symptoms compared to WLC (Cardamone‐Breen et al., 2018). Schwinn et al. (2014) reported significant improvements in youth stress symptoms but not alcohol use relative to NI at 5‐month follow‐up.

Medium‐term (6–12-month) follow‐up outcomes

Among four studies that reported medium‐term follow‐up outcomes, two maintained improvements in at least one measure of parent‐reported youth externalising symptoms (Sanders et al., 2012; Sourander et al., 2016), compared to WLC and EC. One study (Baker et al., 2017) maintained nonsignificant findings on three measures of youth externalising behaviours, and reported significant improvements on two measures of externalising behaviours compared to WLC at 9‐ month follow‐up. Schinke et al. (2009b) reported significant reductions relative to NI at 1‐year follow‐up in adolescent misuse of alcohol, marijuana, and prescription medication, but not cigarettes or depression symptoms.

Long‐term (>12-month) follow‐up outcomes

Only three studies reported intervention outcomes at long‐term follow up, Sourander et al. (Citation2016) reported significant improvements in youth externalising symptoms at 24‐months compared to CAU. Similarly, Sourander et al. (Citation2016) reported that improvements in youth externalising symptoms, but not callous‐unemotional traits, were maintained at 24-months. Finally, Schinke et al. (2011) and Fang et al. (Citation2010) both reported significant improvements in adolescent self‐reported misuse of alcohol, marijuana, and prescription medication, but not depression or misuse of cigarettes compared to NI at 2‐years.

Engagement (secondary outcomes)

Table presents engagement outcomes across studies in terms of rates of parent retention, adherence to the intervention program, and strategies utilised to increase engagement with underserved populations during development and recruitment stages.

Table 4. Summary of study results for engagement outcomes

Study retention

At post‐intervention, rates of study retention across studies ranged from 60.6 to 98.5%, with an average of M = 86.5%. Fourteen studies did not report follow‐up at any time point after post‐intervention data collection (DuPaul et al., Citation2017; Enebrink et al., 2012; Hinton et al., 2017; Irvine et al., 2015; Jones et al., Citation2014; Khanna et al., 2017; Kuravackel et al., 2018; MacKenzie & Hilgedick, Citation1999; Morawska et al., 2014; Nixon et al., Citation2003; Olthuis et al., 2018; Sanders et al., 2000; Van Zeijl et al., Citation2006; Yap et al., 2018). Short‐term follow‐up (<6 months post‐intervention) was reported for five studies, across which study retention rates ranged from 64.4 to 92.5%, M = 80.2%. Five studies reported medium‐term follow‐up (6–12-months), across which study retention rates ranged from 78.2 to 94.3%, M = 84.2%. Long‐term follow up (>12-months) was reported by two studies, with study retention rates ranging from 70.7 to 90.4%, M = 80.6%.

Program adherence

Program adherence was measured and reported according to a number of strategies. Intervention programs that involved self‐directed learning in the form of weekly learning modules or sessions frequently measured program adherence according to mean number of modules or sessions completed (n = 6, Breitenstein et al., 2016; Day & Sanders, 2018; DuPaul et al., 2017; Hinton et al., 2017; Morgan et al., 2017; Yap et al., 2018), or percentage of the sample that completed the intervention program to a particular stage of the outlined protocol (n = 12, Baker et al., 2017; Breitenstein et al., 2016; Cardamone‐Breen et al., 2018; Day & Sanders, 2018; Enebrink et al., 2012; Irvine et al., 2015; Morawska et al., 2014; Morgan et al., 2017; Sanders et al., 2012; Sanders et al., 2000; Schwinn et al., 2014; Yap et al., 2018). Ten studies did not report program adherence in any format (Hemdi & Daley, 2017; Jones et al., 2014; Khanna et al., 2017; Kuravackel et al., 2018; MacKenzie & Hilgedick, 1999; Nixon et al., 2003; Schinke 2009a; Schinke 2009b; Sourander et al., 2016; Van Zeijl et al., 2006). Among six studies that reported the mean number of modules or sessions completed, completion ranged from 50.0% of intended program to 87.5%, M = 68.6%. Across 12 studies, proportions of the sample who completed the entire intervention program according to the stipulated protocol ranged extremely broadly, from 22.8 to 97.2%, M = 62.0%. One study contrasted program adherence between self‐directed learning programs with and without coaching (Day & Sanders, Citation2018), reporting notably higher program adherence when a component of coaching was also present (53.0% with coaching, 22.8% without coaching).

Strategies to enhance engagement with underserved parent populations

Nineteen studies reported strategies to enhance engagement (Baker et al., Citation2017; Breitenstein et al., 2016; Cardamone‐Breen et al., Citation2018; Day & Sanders, Citation2018; DuPaul et al., Citation2017; Fang et al., Citation2010; Hemdi & Daley, Citation2017; Hinton et al., Citation2017; Irvine et al., Citation2015; Jones et al., Citation2014; Kuravackel et al., Citation2018; MacKenzie & Hilgedick, Citation1999; Morawska et al., Citation2014; Morgan et al., Citation2017; Sanders et al., Citation2012; Sanders et al., Citation2000; Schwinn et al., Citation2014; Sourander et al., Citation2016; Yap et al., Citation2018), outlined either in the primary article describing the randomised controlled trial evaluation of the intervention, or the program development article. Of these, 12 described utilising a strategy intended to enhance engagement with underserved parent populations (Baker et al., Citation2017; Breitenstein et al., 2016; Day & Sanders, Citation2018; Fang et al., Citation2010; Hemdi & Daley, Citation2017; Irvine et al., Citation2015; Jones et al., Citation2014; Kuravackel et al., Citation2018; Morawska et al., Citation2014; Morgan et al., Citation2017; Sanders et al., Citation2012; Schwinn et al., Citation2014). These underserved parent populations included lower‐SEP families (Baker et al., Citation2017; Breitenstein et al., 2016; Day & Sanders, Citation2018; Hemdi & Daley, Citation2017; Irvine et al., Citation2015; Morgan et al., Citation2017; Schwinn et al., Citation2014), ethnic minorities (Fang et al., Citation2010; Irvine et al., Citation2015; Jones et al., Citation2014; Morawska et al., Citation2014; Sanders et al., Citation2012), fathers (Jones et al., Citation2014), and families living in rural areas (Kuravackel et al., Citation2018).

Engagement strategies targeting underserved parent populations fell into three broad implementation categories: recruitment approaches that targeted underserved populations (n = 5), tailored program features (n = 4), and program development strategies (n = 6). Recruitment approaches either took the form of targeting recruitment sites frequented by lower‐income or ethnic minority families (Baker et al., Citation2017; Breitenstein et al., 2016; Fang et al., Citation2010; Schwinn et al., Citation2014) or requiring participants to meet specific socioeconomic risk factors (Day & Sanders, Citation2018). No studies implemented recruitment approaches to increase engagement with male or rural parents. Tailored program features involved allowing participants to teleconference from rural bases (Kuravackel et al., Citation2018), the use of no‐cost messaging services (Hemdi & Daley, Citation2017), multicultural video models (Sanders et al., Citation2012) or ensuring program content was written at a level accessible to participants with lower‐education levels (Irvine et al., Citation2015). Program development strategies were guided by consultation with parent focus groups, user preference data or parent survey data that strategically included underserved populations such as lower‐income parents (Breitenstein et al., 2016; Morgan et al., Citation2017), ethnic minorities (Breitenstein et al., 2016; Fang et al., Citation2010; Irvine et al., Citation2015; Jones et al., Citation2014; Morawska et al., Citation2014), or male parents (Jones et al., Citation2014).

Study retention rates for studies that attempted to enhance engagement for underserved parent populations ranged from 60.6 to 97.6%, M = 84.8%. These study retention rates varied according to the type of engagement strategy used for underserved groups, with studies utilising recruitment strategies having the highest study retention rates, M = 91.4%, followed by tailored program features, M = 90.1%, and program development strategies, M = 81.1%. Studies that incorporated more than one engagement strategy reported average study retention rates of 94.5%. Due to limited and inconsistent reporting of program adherence rates across studies, the relationship between engagement strategies and program adherence rates for underserved parent populations could not be investigated.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review aimed to investigate the efficacy of technology‐assisted parenting interventions on youth mental health and parent outcomes; and examine the extent to, and means by which, they engaged underserved parent populations. A total of 43 articles comprising 25 individual studies were identified, for which a discussion is presented in this section for youth and parent outcomes at post‐intervention and follow‐up, and engagement with underserved parent populations.

Efficacy of technology‐assisted parenting interventions on parent outcomes

This review found consistent evidence for the use of technology‐assisted parenting interventions, either in the form of self‐directed learning or remote therapist contact, for improving parenting skills in the context of youth externalising behaviours. Inconsistent evidence was found for programs targeting internalising problems, although given the very small number of these programs identified by this review, extrapolation of this finding should be made with caution. Improvements found were maintained across short‐, medium‐ and long‐term time points, where follow‐up was conducted. These findings are analogous to those found in previous reviews of group and individual face‐to‐face parent training programs (Kaminski, Valle, Filene, & Boyle, Citation2008). Parent mental health outcomes were inconsistent across and within studies, consistent with a review of traditional parenting programs by Barlow, Smailagic, Huband, Roloff, and Bennett (Citation2014).

In particular, insufficient evidence was found for self‐directed learning programs improving parent anxiety, stress or depressive outcomes across five studies. However, results were mixed among studies evaluating interventions that combined self‐directed learning and remote therapist contact. This builds on evidence to suggest that the effectiveness of technology‐assisted interventions for mental health outcomes is improved by some degree of structured therapist contact (Means, Toyama, Murphy, Bakia, & Jones, Citation2009; Richards & Richardson, Citation2012). Given the importance of parent mental health as a precursor to youth mental health (Sandler et al., Citation2011), this supports a multi‐level approach to dissemination of technology‐assisted parenting interventions, in which parents with indicated risk for poorer mental health are provided with access to programs with additional therapist support.

With regard to parental self‐efficacy, this review found evidence for improvements when technology‐assisted interventions involved self‐directed learning or incorporated self‐directed learning with remote therapist contact; but not remote therapist contact alone. However, this finding should be interpreted with caution, given that only one study reported on parental self‐efficacy outcomes for remote therapist contact. Additionally, no studies in this review reported long‐term follow‐up on parental self‐efficacy outcomes. Given the conceptual importance of parental self‐efficacy in enactment of effective parenting and maintenance of intervention effects on parenting behaviours (Jones & Prinz, Citation2005), it is imperative that future research in the area of technology‐assisted parenting interventions give consideration to longer‐term effects on parent efficacy.

Efficacy of technology‐assisted parenting interventions on youth mental health outcomes

Most of the studies included in this review targeted youth externalising behaviours, with very few addressing internalising or substance use behaviours. Given the limited number of studies identified and heterogeneity across the design of interventions, these results should be interpreted with caution, particularly with regard to interventions that focus on non‐externalising outcomes. All studies that evaluated interventions with a component of remote therapist contact demonstrated significant improvements in youth mental health outcomes, primarily externalising symptoms. This is consistent with previous reviews (Means et al., Citation2009; Richards & Richardson, Citation2012), which found that programs yield better outcomes and higher completion rates when technological components of programs are combined with therapist support.

These findings build upon evidence reviewed by Baumel et al. (Citation2017) and support the use of digital parent training programs for disruptive youth behaviours, particularly where professional support is a component of the intervention. Effect sizes ranged broadly across studies from small to large, according to Cohen's (Citation1988) criteria. This is comparable with previous meta‐analyses that have reported very small‐to‐medium pooled effects in traditional parent training interventions for internalising and youth behavioural problems (Kaminski et al., Citation2008; Yap et al., Citation2016). Findings from this review suggest technology‐assisted programs may be a viable and affordable alternative to these traditional programs.

In interpreting these findings, it is worth noting that nearly half (48.0%) of eligible studies pertained to very young children aged between 0 and 5 years, while 72.0% targeted children aged less than 12-years. Youths in the included studies ranged in age from 12-months to 15-years, with no studies including older adolescents from 15 to 18-years. Further to this, among the 18 studies that focussed on children under 12-years, only one included intervention components that targeted internalising symptoms. Conversely, three of the seven studies that evaluated interventions for adolescents targeted internalising symptoms and three targeted both substance use behaviours and internalising symptoms. As such, the conclusions that can be drawn from these findings are limited primarily to interventions for externalising symptoms in children aged below 12-years, and are severely limited for adolescents, particularly older adolescents from 15 to 18-years.

Engaging underserved parent populations

An additional aim of this review was to explore strategies used to increase engagement, particularly among underserved parent populations. Concordant with previous reviews (Chacko et al., Citation2016; Finan et al., Citation2018), measures of engagement outcomes varied substantially between studies, with program adherence measures including the mean number of completed modules or sessions for the entire sample, the percentage of the sample that were compliant with a protocol, or the percentage of the sample that completed a certain number of modules or sessions. Upon inspection, no clear connections between engagement outcomes and participant demographic characteristics such as educational attainment or ethnicity were observed. These equivocal findings regarding the impact of individual factors may be explained through cumulative risk theory, which states that individual risk factors may be insufficient to impact engagement; instead it is a collection of interrelated factors that influence parental engagement in programs (Evans, Li, & Whipple, Citation2013).

Select studies described strategies utilised to increase engagement, of particular interest to this review were those that outlined strategies relevant to underserved parent populations. The relationship between engagement strategies and engagement outcomes was largely unclear due to limited and inconsistent reporting. However, this review found lower post‐intervention study retention rates in studies that incorporated a program development strategy for underserved parent populations, compared to studies that made use of the other two types of engagement strategies. This suggests that the employment of strategies that focus on consultation with underserved parents during the program development stage has been less effective in engaging these populations than that of recruitment and tailoring strategies. Further research is needed to identify evidence‐based practices that will allow researchers to capitalise upon the input of underserved parent populations in the development of appropriate programs.

Although studies attempted to adjust features or recruitment strategies to target under‐engaged groups, the historical absence of these groups from parenting research (Lundahl et al., Citation2008; McGoron & Ondersma, Citation2015) suggests the programs were still largely designed based on input and evidence from parent populations that more commonly engage in parenting programs (i.e., higher‐educated, urban mothers). Higher average study retention rates were found when more than one engagement strategy was used, suggesting that more systematic and comprehensive engagement strategies may be required to develop programs that encourage ongoing participation from these underserved parent groups. While further investigation is needed, researchers should consider implementing multiple engagement strategies to increase the representativeness of research samples, facilitating the development of appropriate programs for underserved parents.

Applicability to Australia's underserved parent populations

In this review, 10 studies (40.0% of those identified) were conducted with an Australian sample, more than any other country with the exception of the United States of America. This is particularly remarkable given Australia's relatively small population, and indicates that at present, Australia is a world leader in the implementation of technology‐assisted parenting programs. However, despite these impressive advances in the Australian context, among Australian studies, engagement with fathers, lower‐SEP and rural families was particularly low. One possible explanation for the over‐representation of middle‐class, urban families is simply that they constitute the bulk of the Australian population (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2018b). However, given that lower‐SEP and rural location represent significant risk factors for the development of youth mental health problems (Bradley & Corwyn, Citation2002; Lawrence et al., Citation2015), attention to these groups is an urgent priority for Australia's service system. Particularly given the scalability of effective technology‐assisted programs to rapidly reach more people, it is important to avoid inadvertently contributing to widening the social gradient of health in Australia (Yap, Citation2018).

The lack of engagement with fathers found by this review mirrors a 2010 Australian population survey that found that only 11% of fathers had participated in a parent education program in the past 6-months (Sanders et al., Citation2010). Moreover, no Australian studies in this review reported that they had utilised any strategy to increase engagement with fathers. Among Australian fathers, factors associated with convenience and comfort with accessing programs have been highlighted as obstacles to engagement (Tully et al., Citation2017). Technology‐assisted programs present a flexible, accessible alternative to traditional programs that have the potential to elicit higher participation from Australian fathers (Dadds et al., Citation2018). This review highlights the need for father‐tailored recruitment and program development strategies, based on research with father‐inclusive samples. Without these strategies, the side‐lining of fathers from parenting interventions will be perpetuated, despite evidence that father involvement is likely to improve youth mental health outcomes (Bagner & Eyberg, Citation2003).

One consideration for extending the reach of Australia's existing programs is the application of successful theory‐driven engagement enhancement strategies that target the attitudes and normative beliefs of these populations. McCurdy and Daro (Citation2001) argue that parents' subjective experience of a program, including ease of access, regularity of program delivery, and incentivisation, predicts their study retention. Given the importance of the subjective experience of participants, this indicates that implementing “one‐size‐fits‐all” engagement strategies with underserved parent populations is not as effective as tailoring them to that specific group's needs. Thus, prior to program implementation, focus groups should be conducted with these populations to identify and remove barriers that disproportionately hinder them from enrolling in and completing programs. These strategies may include increasing accessibility to internet and technological devices, designing programs that are compatible across different platforms and devices so that they can be accessed by lower‐SEP populations via smartphones, providing additional practitioner support sessions, or tailoring program content to under‐engaged parent populations (Fernando et al., Citation2018; Finan et al., Citation2018; Ingoldsby, Citation2010).

Recommendations for practice and public health applications

This review suggests that technology‐assisted parenting programs can be useful tools for practitioners to draw upon when endeavouring to improve youth mental health outcomes and positive parenting skills. However, this review highlights that comprehensive strategies are needed to ensure that services are not inadvertently contributing to existing health inequalities. Organisations and practitioners that contract or deliver parent services are positioned to be an integral component of such engagement strategies for underserved parent populations. Particularly, practitioners need to direct parents to appropriate programs based on their individual needs, with Axford, Lehtonen, Kaoukji, Tobin, and Berry (Citation2012) demonstrating that an accurate referral process can directly increase program attendance. However, the diverse needs and preferences of different parents can only be met if there is sufficient diversity of programs. Thus, evidence‐based program development should be funded and supported so that practitioners can effectively fulfil their responsibility to refer parents appropriately.

Limitations and future directions

Despite promising findings, limitations of the present review should be taken into consideration when interpreting these findings. There was a high degree of heterogeneity across the interventions that were evaluated in terms of the type and function of the technology used and the types of youth, parent and engagement outcomes reported. In particular, very few studies focussed on internalising problems and there was limited or inconsistent reporting of program adherence across studies, therefore it is difficult to draw conclusions about both intervention efficacy and levels of parental engagement. Future studies should endeavour to capture recruitment, attendance and completion data consistently and comprehensively to allow the field to better identify engagement domains that require further attention.

A minority of studies in this review attempted to address the unique needs and preferences of any underserved parent population, highlighting the need for greater acknowledgement of the diversity of parent populations. One method which may provide unique opportunities for understanding parents' needs is discrete‐choice experiments (Chacko et al., Citation2016). Wymbs et al. (Citation2016) utilised this consumer preference based method to demonstrate how parent preferences for treatment format influenced their participation in a parenting program. This highlights the potential use of parent preference data in the development of technology‐assisted parent interventions to ensure program features meet the needs of specific targeted groups.

Summary and conclusions

This review described and synthesised the efficacy of current technology‐assisted parent training interventions for the prevention of youth mental health problems, and evaluated their engagement with underserved Australian parent populations. While the scarcity and heterogeneity of research in this area restricts any firm conclusions from being drawn, preliminary evidence was found for the efficacy of technology‐assisted parenting programs (especially those supplemented with therapist contact) to improve youth mental health outcomes, particularly externalising behaviours. Findings regarding parent outcomes were varied, with more programs showing efficacy for parenting skills, compared to parental self‐efficacy or mental health outcomes. The small number of studies that successfully engaged a substantial percentage of underserved parents highlights the need for comprehensive strategies for program development and recruitment to enhance engagement with these populations. As such, the efficacy and applicability of technology‐assisted parenting interventions for underserved parent populations in Australia remain to be ascertained as this field continues to advance.

raup_a_12098949_sm0001.docx

Download MS Word (24 KB)ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Ms Ayesha Saha and Miss Amber Weinman in various stages of the literature review process. The authors received support from the National Health and Medical Research Council (MBHY, APP1061744) and the Australian Research Council (A.H. and G.B.).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

Funding information Australian Research Council; National Health and Medical Research Council, Grant/Award Number: APP1061744

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM‐5). Washington, DC: APA.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2018a). Household use of information technology, Australia, 2016‐17. cat no. 8146.0. Retrieved from http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/mf/8146.0.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2018b). Census of population and housing: Reflecting Australia—Stories from the Census, 2016. cat no. 2071.0. Retrieved from http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Lookup/by%20Subject/2071.0~2016~Main%20Features~In%20this%20Issue~1.

- Axford, N., Lehtonen, M., Kaoukji, D., Tobin, K., & Berry, V. (2012). Engaging parents in parenting programs: Lessons from research and practice. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(10), 2061–2071. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.06.011

- Baggett, K. M., Davis, B., Feil, E. G., Sheeber, L. L., Landry, S. H., Carta, J. J., & Leve, C. (2010). Technologies for expanding the reach of evidence‐based interventions: Preliminary results for promoting social‐emotional development in early childhood. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 29(4), 226–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121409354782

- Bagner, D. M., & Eyberg, S. M. (2003). Father involvement in parent training: When does it matter? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 32(4), 599–605. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_13

- Baguley, C., Farrand, P., Hope, R., Leibowitz, J., Lovell, K., Lucock, M., … William, C. (2010). Good practice guidance on the use of self‐help materials within IAPT services. Technical Report. IAPT. Retrieved from http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/9017/1/goodpracticelucock.pdf.

- *Baker, S., Sanders, M. R., Turner, K. M., & Morawska, A. (2017). A randomized controlled trial evaluating a low‐intensity interactive online parenting intervention, Triple P Online Brief, with parents of children with early onset conduct problems. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 91, 78–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2017.01.016

- Barlow, J., Smailagic, N., Huband, N., Roloff, V., & Bennett, C. (2014). Group‐based parent training programmes for improving parental psychosocial health. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (5), 1465–1858. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002020.pub4

- Baumel, A., Pawar, A., Mathur, N., Kane, J. M., & Correll, C. U. (2017). Technology‐Assisted Parent Training Programs for Children and Adolescents with Disruptive Behaviors: A Systematic Review. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 78(8), e957–e969. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.16r11063

- Bradley, R. H., & Corwyn, R. F. (2002). Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 371–399. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.13523

- ‡Breitenstein, S. M., Brager, J., Ocampo, E. V., & Fogg, L. (2017). Engagement and Adherence With ezPARENT, an mHealth Parent‐Training Program Promoting Child Well‐Being. Child Maltreatment, 22(4), 295–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559517725402

- *Breitenstein, S. M., Fogg, L., Ocampo, E. V., Acosta, D. I., & Gross, D. (2016). Parent use and efficacy of a self‐administered, tablet‐based parent training intervention: A randomized controlled trial. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 4(2), e36. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.5202.

- ‡Breitenstein, S. M., & Gross, D. (2013). Web‐based delivery of a preventive parent training intervention: A feasibility study. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 26(2), 149–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcap.12031

- Breitenstein, S. M., Gross, D., & Christophersen, R. (2014). Digital delivery methods of parenting training interventions: A systematic review. Worldviews on Evidence‐Based Nursing, 11(3), 168–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12040

- Breitenstein, S. M., Gross, D., Fogg, L., Ridge, A., Garvey, C., Julion, W., & Tucker, S. (2012). The Chicago Parent Program: Comparing 1‐year outcomes for African American and Latino parents of young children. Research in Nursing & Health, 35(5), 475–489. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.21489

- §Breitenstein, S. M., Schoeny, M., Risser, H., & Johnson, T. (2016). A study protocol testing the implementation, efficacy, and cost effectiveness of the ezParent program in pediatric primary care. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 50, 229–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2016.08.017

- §Breitenstein, S. M., Shane, J., Julion, W., & Gross, D. (2015). Developing the eCPP: Adapting an Evidence‐Based Parent Training Program for Digital Delivery in Primary Care Settings. Worldviews on Evidence‐Based Nursing, 12(1), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12074

- *Cardamone‐breen, M. C., Jorm, A. F., Lawrence, K. A., Rapee, R. M., Mackinnon, A. J., & Yap, M. B. H. (2018). A Single‐Session, Web‐Based Parenting Intervention to Prevent Adolescent Depression and Anxiety Disorders: Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(4), e148. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.9499.

- Chacko, A., Jensen, S. A., Lowry, L. S., Cornwell, M., Chimklis, A., Chan, E., … Pulgarin, B. (2016). Engagement in behavioral parent training: Review of the literature and implications for practice. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 19(3), 204–215. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-016-0205-2

- Christensen, H., Griffiths, K. M., & Farrer, L. (2009). Adherence in internet interventions for anxiety and depression: A systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 11(2), e13. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1194

- Clarke, G., & Yarborough, B. J. (2013). Evaluating the promise of health IT to enhance/expand the reach of mental health services. General Hospital Psychiatry, 35(4), 339–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.03.013

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Commonwealth of Australia. (2009). Fourth National Mental Health Plan: An agenda for collaborative government action in mental health 2009–2014. Retrieved from https://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/9A5A0E8BDFC55D3BCA257BF0001C1B1C/$File/plan09v2.pdf.

- Copeland, W. E., Miller‐johnson, S., Keeler, G., Angold, A., & Costello, E. J. (2007). Childhood psychiatric disorders and young adult crime: A prospective, population‐based study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(11), 1668–1675. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06122026

- Copeland, W. E., Shanahan, L., Costello, E. J., & Angold, A. (2009). Childhood and adolescent psychiatric disorders as predictors of young adult disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66(7), 764–772. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.85

- Cunningham, C., Deal, E., Rimas, K., Buchanan, H., Gold, D., Sdao‐jarvie, H., & Boyle, M. (2008). Modeling the Information Preferences of Parents of Children with Mental Health Problems: A Discrete Choice Conjoint Experiment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(7), 1123–1138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-008-9238-4

- Dadds, M., Sicouri, G., Piotrowska, P., Collins, D., Hawes, D., Moul, C., … Tully, L. (2018). Keeping Parents Involved: Predicting Attrition in a Self‐Directed, Online Program for Childhood Conduct Problems. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 53, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2018.1485109

- *Day, J. J., & Sanders, M. R. (2018). Do Parents Benefit From Help When Completing a Self‐Guided Parenting Program Online? A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Triple P Online With and Without Telephone Support. Behavior Therapy, 49, 1020–1038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2018.03.002

- Dickman, S. L., Himmelstein, D. U., & Woolhandler, S. (2017). Inequality and the health‐care system in the USA. The Lancet, 389(10077), 1431–1441. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30398-7

- Dretzke, J., Davenport, C., Frew, E., Barlow, J., Stewart‐brown, S., Bayliss, S., … Hyde, C. (2009). The clinical effectiveness of different parenting programmes for children with conduct problems: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 3(1), 7–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-3-7