Abstract

Objective

Australian research on volunteering is rich and diverse, but also increasingly fragmented. In an attempt to promote a more integrated study of volunteering, we review volunteering research conducted in Australia, using volunteering journey as a framework. Specifically, we summarise literature on volunteer characteristics, motivations, benefits, psychological contract, commitment, and withdrawal.

Method

A comprehensive review yielded 152 studies on volunteering conducted in Australia.

Results

We find that volunteers have distinct characteristics, such as being older, better connected, employed, and residing in rural areas. There are a variety of reasons that prompt individuals to volunteer, and this motivation does change over time. Volunteering leads to better psychological well‐being, as well as increases in social and human capital. Volunteer expectations and commitment are key drivers of ongoing volunteering. Finally, stress, work–family conflict, and negative interactions with others lead to volunteer withdrawal.

Conclusion

A lot is known about volunteering, however, future advancement of the field will depend on better integration across disciplines and domains. Currently, volunteering is viewed as a set of distinct stages, and a more integrated approach is required. We also note a lack of theoretical and methodological rigour in many Australian studies on volunteering.

Funding information Australian Research Council; Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC

What is already known about this topic

Volunteering represents an important and beneficial civic activity for all Australians

There are growing concerns over the viability and sustainability of volunteering workforce in Australia

Volunteering research in Australia is rich and diverse, but also increasingly fragmented, which inhibits more integrative study

What this topic adds

This narrative review integrates Australian volunteering research using a metaphor of a volunteer's journey with distinct yet interconnected stages

An overview of research findings and insights is provided to guide volunteer researchers and practitioners

The main criticism of volunteering research in Australia is a lack of theoretical and methodological rigour

INTRODUCTION

Volunteering work in Australia has been estimated to be worth in excess of $43 billion per year (ABS, Citation2016). Undoubtedly, volunteering represents an important and beneficial civic activity for all Australians; therefore, it attracts continuous attention from researchers, government, and industry. Recently, concerns were raised about the future of volunteering in Australia, such as the diminishing number of volunteers and median volunteering hours (Oppenheimer, Haski‐Leventhal, Holmes, Lockstone‐Binney, & Meijs, Citation2015). Additionally, the nature of volunteering seems to be changing with an increase of informal volunteering, as opposed to traditional, organisation‐bound volunteering (Whittaker, McLennan, & Handmer, Citation2015) and spontaneous volunteering (McLennan, Molloy, & Handmer, Citation2016). These challenges and trends represent a threat to volunteering sustainability. In an attempt to address current volunteering challenges and to promote a more integrative approach to volunteering research into the future, we offer a narrative review of Australian volunteering research, focusing on an individual (as opposed to organisational) perspective.

Volunteering has been defined as “freely chosen and deliberate helping activities that extend over time, are engaged in without expectation of reward or other compensation and often through formal organizations, and that are performed on behalf of causes or individuals who desire assistance” (Snyder & Omoto, Citation2008, p. 3). This definition builds on the work of Cnaan, Handy, and Wadsworth (Citation1996) and contains the elements usually found in definitions used in Australia: free‐will, formal organisation, without payment, and in the service of others or the community. Thus, volunteering is a specific type of a helping behaviour that has clear boundaries. Furthermore, for the purposes of this review, volunteering is conceptualised as a proactive activity that entails some commitment of time and effort, rather than reactive such as spontaneous volunteering, reviewed elsewhere (Dunn, Chambers, & Hyde, Citation2016; Whittaker et al., Citation2015). In the 2016 census, 3.62 million of Australians (19% of the population aged 15-years and over) indicated that they were engaged in voluntary work through an organisation or group.Footnote1 The United Nations estimated that this translates into almost 1 million full‐time equivalent people, of whom 63% are females (United Nations Volunteers, Citation2018).

Researchers are making continuous attempts to understand factors that affect volunteer recruitment, engagement, and retention from both individual‐ and organisation‐based perspectives. Previous attempts have been made to integrate the exisiting volunteering literature through an organisational lens, specifically, volunteer management practices, largely adapted from the Human Resource Management literature (e.g., Cuskelly, Taylor, Hoye, & Darcy, Citation2006). However, we chose to focus on an individual level in order to better understand the psychological processes underlying volunteering behaviour. We believe such an approach will allow us to build a more advanced understanding of why individuals choose to volunteer and maintain this activity over time, which in turn, will address the volunteering sustainability challenges that organisations face.

The literature on volunteering is extensive and spans a variety of topics and disciplines, including sociology, management, psychology, and political science. Unsurprisingly, previous reviews of volunteering focus on a particular population of interest (e.g., seniors; Anderson et al., Citation2014), a particular type of volunteering (e.g., employee volunteering; Rodell, Breitsohl, Schröder, & Keating, Citation2016), or a particular discipline (e.g., sociology; Wilson, Citation2000). Similarly, our review is primarily limited to the discipline of psychology, and a particular geography, that is, we review empirical research conducted with volunteers in Australia.

Due to the enormous variety in volunteering research, no integrated theory of volunteering has emerged (Hustinx, Cnaan, & Handy, Citation2010) and the literature remains largely fragmented, which prevents the advancement of knowledge in the study of volunteering. To address this fragmentation we have organised our review along the distinct, yet interconnected stages of the individual's volunteering journey. These stages are becoming a volunteer, deriving benefits from volunteering activities, remaining a volunteer over time, and withdrawing from volunteering. Experiences at different stages of volunteering are interconnected and affect decision to remain in a volunteering role. This framework has been informed by previously proposed volunteer management models (e.g., Studer & Von Schnurbein, Citation2013), which, however, considered the volunteering process from an organisational perspective. Therefore, we have refined the stages in the framework to align with the individual perspectives on volunteering, as these emerged from our review of the literature.

METHODOLOGY

To get a more comprehensive overview of the published and unpublished research on volunteering in Australia, we conducted an extensive search using Web of Science and Scopus databases. Because our aim was to capture a broad selection of literature on volunteering, we used rather unrestricted keywords (i.e., “volunteer” and “volunteering”) contained anywhere in the article's text. At the later stages of the search, we also used keyword “Australia” to narrow the results. The search was completed in August 2018. The results returned by the databases were screened for relevance and records that were found suitable were stored for later analysis. The initial search uncovered approximately 600 published and unpublished manuscripts.

To sort and analyse the identified literature we engaged in several rounds of inductive and deductive coding. Because we were primarily interested in reviewing research on volunteering conducted in Australia, the first step of coding involved assigning a country in which the data was collected. This proved to be a harder task than anticipated because a small proportion of papers did not identify the location of data collection (~10%). Finally, we identified 152 studies on volunteering conducted in Australia, including both published and unpublished research.

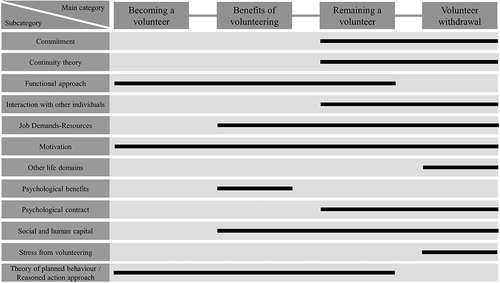

Following this, articles were coded inductively to identify main topics (categories) that emerged as we systematically analysed the abstracts. Next, articles were assigned a primary pre‐defined category (e.g., becoming a volunteer, benefits, being a volunteer, withdrawal), derived from the main topics identified in the first coding round and review of the published models of volunteer management practices. In some cases, articles were also assigned a secondary pre‐defined category, where they addressed more than one stage in the volunteering journey. In addition, information on journal name, year of publication, title, authors, and abstract were recorded. Due to the aims and nature of our review, we primarily focused on analysing and describing published, peer‐reviewed studies conducted in Australia that investigated phenomena at the individual level of analysis. However, where necessary, we include information about research conducted in other countries or at a different level of analysis, as well as non‐peer‐reviewed publications. In the following sections, we provide an account of the literature identified in each of the review categories.Footnote2 Most subtopics identified in the review align with several volunteering journey stages, as depicted in Figure 1.

WHO VOLUNTEERS?

Census data suggested that about 19% of Australians volunteer (ABS, Citation2016). Volunteers differ from non‐volunteers in terms of particular demographic, socioeconomic, and geographic characteristics. Latest findings from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey (Beatton & Torgler, Citation2018) suggested that employed, non‐married, divorced or widowed individuals volunteer less often, while volunteering is positively related to having children and being female, married, more highly educated, healthier, older, retired, and unemployed. A similar pattern of results was observed among older Australians (Warburton, Le Brocque, & Rosenman, Citation1998); those in white collar occupations and higher self‐rated health were more likely to volunteer, but not those in self‐employment. A more recent study (Warburton & Stirling, Citation2007) of volunteering by older Australians (aged 55+) found that attending recreational, cultural, community, cultural, or religious activities were associated with higher odds of volunteering. This study also confirmed that having an excellent or very good health was positively related to volunteering. A study of 93 young Australians (aged 13–24; Webber, Citation2011) found that those who were older, better educated, and had access to networks and mentoring we more likely to be engaged in volunteering with people who are in need, are disadvantaged, or marginalised. Finally, a recent report by the United Nations Volunteers (Citation2018) provided an interesting insight into the fluctuation of volunteering rates with age. The volunteering rate is said to peak at 40% for 36–45-years old Australians, and drop to the lowest rate of around 20% for those 26–35-years old and 56–65-years old, with 65+ years old having a slightly higher rate of participation again. Overall, these findings are consistent with evidence from other Western nations. For example, a review of volunteering literature published in 1990s in the United States found that volunteers are typically people with higher incomes, higher education, and more social resources (Wilson, Citation2000).

These findings are also consistent with both the social capital theory and sociostructural resources theory. The social capital theory posits that volunteering is both a key mechanism for building trust and strong social networks, and an outcome of strong social networks (Warburton & Stirling, Citation2007). Thus, volunteering is associated with high levels of social connectedness, leading to stronger networks and higher levels of trust. At the same time, individuals with stronger social networks are more likely to volunteer, because they possess more social capital, which is key in the ability to cooperate and collaborate with others. The sociocultural resources theory argues that individuals have different levels of access to opportunities and resources, which explains the different roles they undertake in society (Warburton & Stirling, Citation2007). Thus, the extra resources available to those of higher socioeconomic status will facilitate volunteering (Wilson & Musick, Citation1997). For example, Overgaard (Citation2016) found that Australian women volunteer more frequently because they find it easier to balance family obligations with the demands of volunteering than with the demands of paid work.

In terms of geographical differences, volunteering seems to be more prevalent in rural areas. The ABS General Social Survey (GSS; ABS, Citation2015) revealed a higher rate of volunteering involvement in rural areas, with a volunteering rate of 34% compared to 31% in metropolitan areas in 2014. Data about rural volunteers in Western Australia (Davies, Lockstone‐Binney, & Holmes, Citation2018) again confirmed that being older, being female, and having children at home was positively related to volunteering, however, there was no significant relationship between employment status and volunteering. Interestingly, Davies et al. (Citation2018) also found that long‐term rural residents were more likely than newer residents to have volunteered. Given the higher prevalence of volunteering in rural areas and some concerns over volunteering sustainability specifically in rural areas (Davies et al., Citation2018; McLennan, Citation2005), we note a lack of research looking into rural volunteering.

The ABS GSS (2015) also provided some further insights into which types of volunteering Australians are engaged in. The survey showed that 31% volunteered with sport and recreation organisations, 27%—other, 24%—education and training, 21%—welfare and community, 19%—religious, and 10%—health. The more frequently reported types of activities were fundraising/sales (23%), teaching/providing information (15%), coaching/refereeing/judging or food preparation/servicing (14% each), and other (21%).

Finally, demographic differences also seem to impact the choice of the specific volunteering activity. For example, Gray, Khoo, and Reimondos (Citation2012) investigated which volunteering organisations Australians are more likely to join at the various stages of life. They found that volunteering in sports/hobby and educational organisations mostly occurs in middle adulthood, potentially related to having children participating in these organisations. Individuals in mid‐adulthood were also found to volunteer less—than younger and older adults—for organisations that are not child‐centric, such as arts and health organisations. Additionally, the authors found that older people mostly volunteer in the welfare and community sector. Furthermore, Gray et al. (Citation2012) also investigated if other demographic characteristics were related to volunteering in specific domains. They found that men are more likely to volunteer in sports/hobby organisations, whereas women are more likely to volunteer for welfare, community, and health organisations. We further explore the differences in volunteer motivations, expectations and outcomes among different demographic groups throughout this review.

Barrier to volunteering

As noted in a previous review (McLennan, Birch, Acker, Beatson, & Jamieson, Citation2004), there is limited knowledge about the reasons why people do not volunteer in Australia. The investigations that have been conducted since the McLennan et al. review have confirmed that the barriers to volunteering in Australia seem to be similar to the barriers in other countries. Hyde and Knowles (Citation2013) found that students were mainly deterred from volunteering by time constraints (68%), but also by a lack of interest in volunteering, a lack of awareness about volunteering opportunities, or just the inconvenience of volunteering. A small group also indicated that they were discouraged to volunteer by the potential emotional or financial costs of volunteering. Additionally, Holmes (Citation2009) found that volunteers indicated that their volunteering brought some costs with it, of which the most significant was time, followed by financial costs. Both time and money investments seemed to be highest in the first year, usually because there are some costs associated with training and starting up, such as purchasing a uniform. Overall, we note the lack of research in this domain and encourage future investigations. A promising recent development is a study by Haski‐Leventhal, Meijs, Lockstone‐Binney, Holmes, and Oppenheimer (Citation2018) who introduced the concept of volunteerability, which offers a richer understanding of how people can be assisted to overcome barriers to maximise their volunteer potential and thus increase volunteering.

BECOMING A VOLUNTEER

Volunteers are a scarce resource and organisations with comparable reputations and activities compete over the same pool of potential volunteers (Randle, Leisch, & Dolnicar, Citation2013). Dolnicar and Randle (Citation2007) analysed ABS data and found that most people join as a volunteer because they were asked or because they knew someone in the organisation. Far fewer people joined because they saw recruitment material in the media or because they looked for the opportunity themselves; over five times more people indicated they joined through existing social connections. Similarly, Baxter‐Tomkins and Wallace (Citation2009) showed that about 70% of emergency service volunteers in NSW joined the services mostly through existing personal relationships. This “sponsor” convinced the new recruit by describing the benefits of joining. The high regard of the other person was the foremost reason to consider joining the volunteering service.

Randle and Dolnicar (Citation2011) showed that a decision to join an organisation by a potential volunteer depends on the perceptions of that volunteering organisation. As such, individuals’ perceptions of volunteer organisations shape which organisations they would consider joining. Moreover, when Randle and Dolnicar (Citation2015) specifically compared potential environmental volunteers to non‐volunteers, they found that the potentials showed more interest not just in protecting the environment, but also in a range of other factors (e.g., socialising). They (Randle & Dolnicar, Citation2011, Citation2015) suggested that volunteer organisations should understand why individual join and address the whole array of reasons in their recruitment. Therefore, in this section of the review we address volunteer motivation and other factors that influence an individual to become a volunteer.

Motivation to volunteer is a well‐researched topic (Hustinx et al., Citation2010). A great deal of research has investigated which reasons to volunteer are most common and these studies generally found a complex interplay between altruistic and personal reasons (e.g., Cnaan & Goldberg‐Glen, Citation1991; Haski‐Leventhal, Citation2009). These reasons are sometimes investigated separately or as a combination (e.g., a profiles of reasons). Frequently, these reasons have been measured as broad categories rather than specific or detailed (e.g., Clary & Snyder, Citation1991; Yeung, Citation2004). Considering the amount of research it is surprising that new reasons for why people volunteer are still being discovered. Some of these reasons seem specific to certain types of volunteering, whereas others could be relevant to all volunteers. For example, Duarte Alonso and Nyanjom (Citation2016) recently found that paying it forward was an important reason to volunteer, in addition to other, well‐documented reasons.

Functional approach

The majority of research looking into the reasons to volunteer used the Volunteer Functions Inventory (VFI; Clary et al., Citation1998). This inventory is based on the functional approach to volunteer motivation, which is concerned with “the needs being met, the motives being fulfilled, and social and psychological functions being served by the activities of those people who engage in volunteer work” (Clary & Snyder, Citation1991, p. 123). In essence, the functional approach states that people have different reasons to engage in the same volunteer activity. These reasons could affect volunteer experiences differently. Therefore, understanding why people volunteer is crucial to fully understand pivotal volunteer experiences. In line with the functional approach to volunteering, the VFI measures six broad categories of motivation or psychological functions met through volunteering. These six volunteer functions include values (i.e., volunteering to express pro‐social values), understanding (i.e., volunteering to learn), enhancement (i.e., volunteering for personal growth), career (i.e., volunteering for career‐relevant experience), social (i.e., volunteering to strengthen social relationships), and protective (i.e., volunteering to alleviate personal problems). A study of The Smith Family volunteers in Australia found that the most important motivational factor was values, followed by understanding and enhancement, whereas career was least important (Zappalà & Burrell, Citation2002). Interestingly though, career and enhancement were the strongest predictors of time spent volunteering, whereas social and values factors were negatively related to time investments.

Other studies in different volunteering populations did not use the VFI as a measure, but still found that most reasons to volunteer were consistent with a functional approach. For example, Hyde and Knowles (Citation2013) used a thematic analysis to understand the volunteering reasons among psychology undergraduate students in Victoria. The most prevalent reasons were that the volunteering (a) helped others, (b) had personal relevance, (c) was easily accessible, (d) gave enjoyment, and (e) provided skill/career development. Anderson and Shaw (Citation1999) discussed the main reasons that motivated 97 volunteers to volunteer at a tourist attraction in Victoria. They used several analytical techniques to study answers to an open‐ended question about the volunteers’ motivation. Across classification methods, the most frequently mentioned reasons for volunteering were (a) interest in the activities of the organisation (e.g., dressing up as a historical figure), (b) social interaction and family involvement, pro‐social motives (e.g., helping others), (c) self‐development (e.g., learning and career building), and (d) enjoyment and recreation. De Villiers, Laurent, and Stueven (Citation2017) found that volunteers at archival organisations across Australia were mainly motivated by the content of their work and subsequently by the social connections that they experienced through their volunteering. Phillips, Andrews, and Hickman (Citation2014) found that hospice volunteers in NSW mainly volunteered to make a difference, including believing in the values of the cause, and for personal development, such as personal growth and skills development.

Although research into volunteering functions is fairly consistent, some researchers argued that it is important to understand the volunteering reasons of specific groups, because these reasons may not be fully captured by the inventory. For example, Ranse and Carter (Citation2010) found that, in a sample of ambulance volunteers, volunteering also provided a way to disconnect from work or give a break from family life. Pegg, Patterson, and Matsumoto (Citation2012) found that tourism volunteers generally volunteered for well‐known reasons, but also because they were looking “to do things different from just traveling” and “for a cheap holiday.” Furthermore, Monga (Citation2006) investigated the reasons for volunteering in a sample of South Australian event volunteers. She argued that the reasons of event volunteers were likely to be ranked somewhat differently than those of typical ongoing volunteers. Monga found that event volunteers’ main reason for volunteering was their affective relation with the event. The second most important reason was that volunteering felt gratifying. Other reasons to participate in event volunteering were altruism towards the community, personal development, and solidarity with traditions or close others. Other research has shown that event volunteers have distinct reasons for volunteering, such as the need to associate with and support an event (Treuren, Citation2009). Building on this event volunteering research, Kim, Fredline, and Cuskelly (Citation2018) compared the content of the Volunteer Functions Inventory to four event volunteer specific inventories. They confirmed that all these inventories overlapped to a degree. Additionally, the event volunteer specific inventories also included aspects unique to event volunteering. Considering the results from these investigations, the reasons for volunteering do not seem to be entirely different for specific groups or event volunteers, but the sub‐group differences are large enough to take into account for future research.

Finally, findings from the reviewed literature suggest that the reasons to volunteer also depends on the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. For example, Stukas, Hoye, Nicholson, Brown, and Aisbett (Citation2016) used the VFI to show that older volunteers generally attached less importance to different reasons to volunteer, except for volunteering because of altruistic values, which remained similar to younger volunteers. They also found that women score higher than men on all reasons to volunteer except for social motivation, on which they score similarly. Furthermore, both Francis and Jones (Citation2012) and McLennan and Birch (Citation2008) found very few intergenerational differences between the reasons to volunteer for emergency management volunteers. Both investigations found that younger (<35-years old) and more mature volunteers (>35-years old) mainly volunteered for the same reasons: “giving back to the community” and “the content of the volunteering work.” However, younger volunteers more frequently reported “career advancement” and “dealing with their own problems/emotions” as reasons to volunteer.

Overall, we note that that the functional approach seems to capture most reasons for volunteering, except volunteering for fun/enjoyment. There are broad overarching reasons to volunteer in all sectors/roles, but on a more granular level the reasons why people volunteer are nearly non‐exhaustive. A potential revision of the current models could consider a hierarchy of motives to contribute to a more nuanced understanding of how the reasons for volunteering are related. Additionally, it seems prudent for any future taxonomy to consider the different types of volunteering to fully and accurately capture the wide array of reasons why people volunteer.

Motivation profiles

Recently, identifying distinct profiles of volunteers based on their motivation to volunteer has become a popular approach in the literature (e.g., Dolnicar & Randle, Citation2007; Kim et al., Citation2018; Kragt, Dunlop, Gagné, Holtrop, & Luksyte, Citation2018). Volunteering is usually investigated based on averages and there is relatively little attention to individual differences. Therefore, Dolnicar and Randle (Citation2007) analysed ABS data that contained the 12 main reasons why people volunteer. They found that the reasons for volunteering clustered into six distinct profiles: “Classic volunteers” want to do something useful, help others, and gain personal satisfaction. “Dedicated volunteers” are motivated by a wide and less focussed range of reasons. “Personally involved volunteers” volunteer because they know someone in the organisation, such as their child. “Volunteers for personal satisfaction” and “altruists” mainly want to help the community, and “niche volunteers” have a few specific and less common motivators, such as gaining work experience. The classic volunteers and the dedicated volunteers were somewhat older than the other groups and included more people who were not part of the current labour force. Volunteers from these two profiles also seemed to be most active, spending more time on volunteering than volunteers from the other profiles.

Similarly, Kim et al. (Citation2018) recently investigated how reasons for volunteering cluster together, using survey data from Queensland sporting event volunteers. As a theoretical framework they used the incentives approach, an alternative taxonomy of volunteering motivation that overlaps with the functional approach. The incentives approach distinguishes three broad underlying volunteer motives: normative incentives (comparable to VFI “values”) describing a genuine concern for others and a desire to help; affective incentives (comparable to VFI “social”) describing social benefits; and utilitarian incentives (somewhat comparable to VFI “understanding” or “career”) describing tangible benefits, such as work experience and skills (Knoke & Prensky, Citation1984). Additionally, Kim et al. (Citation2018) measured some reasons that are specific to sports volunteers, such as the love for sports. They found that the volunteering motives clustered in four distinct clusters: (a) Material benefit seekers, (b) sports and community enthusiasts, (c) altruists, and (d) career and social relationship seekers. This study also uncovered some sociodemographic differences between the profiles, for example, career and social relationship seekers were younger and mostly unemployed or employed in a part‐time job. Material benefit seekers and career and social relationship seekers were also more likely to be first‐time volunteers.

So far, the Australian studies (e.g., Dolnicar & Randle, Citation2007; Kim et al., Citation2018) that have looked at profiles of volunteer motivations have shown that motives cluster together in a meaningful way. Until now, these profiles have mostly been compared in demographic differences. Future research could consider using volunteer motivation profiles to investigate volunteering experiences and outcomes. For example, Kragt et al. (Citation2018) found three distinct profiles of emergency services volunteers and showed that these initial motivation profiles were related to later experiences and turnover intentions.

Initial and later motivation

Some studies (e.g., Alam & Campbell, Citation2017; Cuskelly, Harrington, & Stebbins, Citation2002; Kim et al., Citation2018) highlighted that the initial motivation to volunteer can change over time. Thus, reasons that prompt individuals to start volunteering might be different from reasons why they continue to volunteer. Therefore, it seems important to distinguish between volunteers’ motivation to join an organisation and to stay with an organisation. However, we find that most research investigating volunteer motivations deduce reasons for “joining as a volunteer” from the reasons “why current volunteers are volunteering.” In contrast, very few investigations have explicitly investigated why people join as a volunteer. For example, Alam and Campbell showed that volunteers’ motivation changed from intrinsic to intrinsic/extrinsic depending on the tasks. Cuskelly et al. (Citation2002) distinguished between “career” volunteers, who volunteer out of a desire to help others in their free time, and “marginal” volunteers, who volunteer out of compliance. Their study of volunteer sport administrators showed that many of the volunteers who reported a “marginal” reason for joining, were reporting a “career” reason to continuing volunteering 12-months later (55%). Based on these results it seems prudent to clearly distinguish between reasons to join a volunteer organisation and reasons to stay.

Potentially, these changes might occur because volunteering brings about unexpected benefits, which further promote volunteer engagement and retention by changing the motivation to volunteer. For example, a study of adult volunteers in a school kitchen garden programme in ACT found that initial motivations were a combination of personal beliefs, the desire to build and participate in the community and pleasure from or a desire to learn about gardening (Henryks, Citation2011). Some of the unexpected benefits reported by these volunteers were the expansion of social network (friendships), sense of pride, and learning from/with children. We believe that the process of change in volunteer motivations is a topic that should be investigated further, with a focus on the triggers and outcomes of these processes. We find this especially important because research has shown that volunteers can change to have more positive motives, which might lead to better retention.

Motivation and personality

In addition to showing that people volunteer for a variety of reasons, some research has looked into individuals differences to investigate volunteer motivation. In general, some studies (e.g., Carlo, Okun, Knight, & de Guzman, Citation2005) have found that people high on agreeableness and extraversion volunteer more often. These findings are similar to results from a small Australian sample: Elshaug and Metzer (Citation2001) found that South Australian volunteer food preparers have a different personality profile than career food preparers, again scoring higher on agreeableness and extraversion. Remarkably, the personality characteristics that are associated with volunteering align neatly with the main reasons for volunteering. First, agreeableness is the tendency to be tolerant, good‐natured, and cooperative (Lee & Ashton, Citation2004), which is related to “giving back to the community,” the number one reason for volunteering identified in several studies (e.g., Dolnicar & Randle, Citation2007; Hyde & Knowles, Citation2013; Zappalà & Burrell, Citation2002). Second, extraversion is the tendency to be gregarious and seek out social situations (Lee & Ashton, Citation2004), which could very well be associated with another frequently reported reason to volunteer—“to connect with others” (e.g., Anderson & Shaw, Citation1999; De Villiers et al., Citation2017).

Although there appears to be some resemblance between volunteer reasons and personality traits, there is little Australian research relating the frequently studied volunteer reasons to dispositional differences. One exception (Francis & Jones, Citation2012), used a competitive perspective and investigated if volunteer functions or values are more predictive of volunteer satisfaction. They found that reasons for joining—as measured with the VFI (Clary et al., Citation1998)—were far more predictive of the volunteers’ satisfaction than volunteers’ values. We would argue that comparing predictive validity of context‐specific motivations to general individual differences is likely to result in comparable results. However, it would be informative to understand if and how fluid volunteer functions emerge from stable individual differences and the characteristics of different volunteering activities.

Theory of planned behaviour/reasoned action approach

A number of studies have tried to explain volunteering behaviour with the theory of planned behaviour (TPB; e.g., Ajzen, Citation1991). The TPB proposes that human behaviour, such as volunteering, follows from behavioural intentions. In turn, intentions are formed by three considerations: attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control. Attitudes reflect if an individual thinks executing the intended behaviour will have positive or negative consequences. Subjective norms reflect if an individual thinks he/she is expected to perform the behaviour. Behavioural control reflects the individual's perception of the difficulty of the intended behaviour, which is often equated to a person's self‐efficacy. More recently, the TPB proposed that a person's control over the situation will affect how behavioural intentions are translated to actual behaviour (Ajzen, Citation2012).

Applying the TPB, several researchers have investigated how Australians are prompted to volunteer (e.g., Greenslade & White, Citation2005; Hyde & Knowles, Citation2013; MacGillivray & Lynd‐Stevenson, Citation2013; Warburton & Terry, Citation2000; Warburton, Terry, Rosenman, & Shapiro, Citation2001). Hyde and Knowles (Citation2013) tested the TPB in a Victorian student population and found that the three key variables of the TPB explained 67% of the variance in volunteering intentions. MacGillivray and Lynd‐Stevenson (Citation2013) tested the TPB in a cross‐sectional study in South Australia and only found partial support for the theory; specifically, attitudes towards volunteering were related to volunteering intentions and these intentions were related to volunteering behaviour. Warburton and colleagues mostly focussed on what prompted older individuals (65+) in Queensland to volunteer. Using the TPB, Warburton and Terry (Citation2000) found that attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control explained unique variance in volunteer intentions and that those intentions predicted the amount of volunteering 4–6 weeks later. Additionally, Warburton et al. (Citation2001) found that, compared to older non‐volunteers, older volunteers saw more benefits of volunteering (i.e., had a more positive attitude), thought that people close to them expected them to volunteer more (i.e., had higher subjective norms), and believed to have somewhat more control over their volunteering behaviours (i.e., had higher perceived control).

In a qualitative study, Randle and Dolnicar (Citation2009) showed that different cultural groups (Australian, Anglo‐Celtic, and Southern European) in Australia all hold positive norms, attitudes and perceived behavioural control towards volunteering. However, the underlying reasons for these aspects of the TPB were different between the groups. For example, the Southern Europeans primarily volunteered to support people with a similar cultural background. In a follow‐up quantitative study, same authors (Randle & Dolnicar, Citation2012) compared Australians to Chinese, Americans, and Germans on the TPB components. They found significant differences in what contributed to forming the norms, attitudes, and perceived behavioural control between the groups. For example, they found that the Chinese were more affected by the opinion of others about volunteering and the Germans believed that volunteering had more personal benefits. Based in their findings, Randle and Dolnicar suggested that volunteer organisations need to develop marketing strategies aimed at specific cultural groups.

Additionally, some studies (Hyde & Knowles, Citation2013; Warburton & Terry, Citation2000) not only confirmed the TPB for volunteering behaviours, but also extended the model. These studies included moral norms in addition to the three core predictors of intentions. Moral norms describe if individuals thinks they should volunteer because it is the morally right thing to do. Moral norms are different from subjective norms in that subjective norms are the perceptions of other people's norms and moral norms originate from the feelings of the person themselves. These studies generally found good support for moral norms as a predictor of volunteering intentions, sometimes even mediating the relation between attitudes towards volunteering and volunteering intentions (Warburton & Terry, Citation2000).

Finally, some researchers combined the TPB with functional approach. In a two‐wave study, Greenslade and White (Citation2005) set out to compare the TPB to the VFI in terms of their predictive validity. They used both frameworks to predict above average volunteering in a sample of Australian welfare volunteers. In the first wave, they collected information on the TPB variables and administered the VFI. A month later, they asked participants to indicate whether they have volunteered three or more hours per week. They also collected other information on volunteering behaviour (such as the frequency and extent of the volunteering work) that was unfortunately not reported in the paper. Their results showed that the TPB explained more variance than the VFI in above average volunteering. Based on these results, Greenslade and White concluded that the TPB model is superior to the VFI model in predicting volunteering. Rather than investigating differences in predictive validity, MacGillivray and Lynd‐Stevenson (Citation2013) suggested that future research should investigate synergies between the TPB and the VFI. For example, while the TPB describes how volunteering behaviour is the result of a person's views on volunteering in general, the VFI describes specific motives for volunteering. Therefore, the TPB seems ideally suited to predict if people engage in volunteering, whereas the VFI may do a better job at describing which volunteering opportunities a person would gravitate towards.

BENEFITS OF VOLUNTEERING

Often the value of volunteering is discussed from an organisational/societal perspective, that is, the contribution of volunteers to the betterment of communities. For example, the value of volunteering is frequently computed by estimating the number of volunteering hours and multiplying that by an amount of dollars that represents the average worth of a volunteering hour. Although these calculations have established that volunteers add great economical value, it remains a matter of debate who is the greatest beneficiary of volunteering: society, the organisation, the recipients, or the volunteers themselves. Holmes (Citation2009) investigated the worth of volunteering for individuals and organisations. Based on interviews with 37 volunteers, she found that these volunteers generally reported experiencing great personal benefits from volunteering. Compared to the benefits derived by the organisation and the recipients, Holmes found that volunteers perceived that they were the primary beneficiaries of volunteering activity.

Indeed, research has demonstrated that volunteering produces a distinct set of intangible resources for an individual including social, human and psychological capital in the form of personal rewards, including personal enrichment, self‐actualization, self‐expression, self‐image, self‐gratification, recreation, and financial returns, as well as social rewards like social attraction and group accomplishment (Stebbins, Citation1996). The results of numerous volunteer surveys conducted in Australia are fairly consistent in demonstrating that individuals engage in volunteering primarily for personal benefit. Based on data from the ABS GSS (2015), Australians volunteer to help others/community (64%), for personal satisfaction (57%), to do something worthwhile (54%), because of personal or family involvement (45%), to maintain social contact (37%), and to use existing skills/experience (31%). In this section of the review, we therefore focus on psychological and social benefits, as well as human capital, derived by individual volunteers.

Psychological benefits

It has been suggested that volunteering is associated with better psychological outcomes, such as wellbeing, because it represents a form of active social engagement. Using a large sample of Australian adults, Mellor et al. (Citation2009) found that volunteers reported a higher level of personal wellbeing (i.e., happiness and cognitive judgement of life satisfaction) and social wellbeing (i.e., trust, participation, reciprocity, and security), compared to non‐volunteers. Volunteers were also found to be more extroverted and optimistic and to perceive a greater sense of control in their lives than non‐volunteers. In a small survey sample of mostly marginalised individuals, Molsher and Townsend (Citation2016) discovered that environmental volunteering led to significant improvements in general well‐being and mood states. In an exit interview, most participants attributed these improvements to the social aspect of the volunteering program and to learning about the environment. Koss and Kingsley (Citation2010) also presented some evidence that sea search volunteering was associated with emotional wellbeing, social benefits, and a connection to nature. Moreover, volunteering was a source of pride and satisfaction. Mollidor, Hancock, and Pepper (Citation2015) found some support for a partially mediating effect of volunteering between religiosity and wellbeing among Australian churchgoers. They used a large survey sample to show that some religious denominations prompted more volunteering, which subsequently improved a person's wellbeing (i.e., general satisfaction). Finally, Bateman, Anderson, Bird, and Hungerford (Citation2016) described how volunteering to take care of patients with mental dementia/delirium in rural Australian hospitals improved volunteers’ attitudes towards patients and their self‐confidence.

It was interesting to note that a large proportion of research has investigated the link between volunteering and psychological wellbeing specifically among older adults. For example, Griffin and Hesketh (Citation2008) found that Australian retirees who continued to work were less satisfied than retirees who transitioned to volunteer work. The positive effect of volunteering on wellbeing has been explained by the socioemotional selectivity theory, which proposes that individuals place a greater importance on emotionally meaningful activities conducted in the present and a lower priority to the pursuit of goals concerned with future achievements as they age (Carstensen, Citation2006). Because volunteering contributes to the needs and welfare of others, it is consistent with older adults’ emotional goals (Thoits, Citation1983). Older people also display more altruism (Hubbard, Harbaugh, Srivastava, Degras, & Mayr, Citation2016), which may explain why volunteering is positively related to age.

Consistent with this approach, Findsen (Citation2016) reviewed the potential benefits and challenges that older (65+) volunteers experience in Australia. He concluded that volunteering matches the desires of retired workers, such as the need to give back to society. Windsor, Anstey, and Rodgers (Citation2008) found that hours spent volunteering were related to psychological well‐being among older Australians. Similarly, longer volunteering time was associated with increase in life satisfaction over a 4‐year period among older Australians, particularly among those who lost more friends during this time (Jiang, Hosking, Burns, & Anstey, Citationin press). However, Windsor et al. (Citation2008) warn that too much volunteering can also lead to a decrease in wellbeing, thus suggesting that there is some optimal level of engagement in volunteering, at least, for older adults.

Job Demands‐Resources model

Our discussion of the psychological benefits of volunteering would be incomplete without mentioning the Job Demands‐Resources model (JD‐R; Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner, & Schaufeli, Citation2001). The JD‐R model posits that demands (e.g., workload, physical demands, and emotional demands) and resources (e.g., social support, autonomy, and feedback) affect volunteers’ mental health. Several studies have used this model to study burnout and engagement in volunteers. Cox, Pakenham, and Cole (Citation2010) studied how job demands (role conflict, role ambiguity, and job overload) and job resources (social support) affect depression and satisfaction through feelings of burnout among HIV/AIDS volunteers. They found some support for the JD‐R model, their results indicated that demands affect volunteer burnout more so, than resources. Lewig, Xanthopoulou, Bakker, Dollard, and Metzer (Citation2007) investigated the JD‐R model in a large sample of South Australia volunteer ambulance officers. They found that burnout fully mediated the relationship between volunteering job demands (time pressure and work‐home interference) with health problems (depression, strain, and reduced happiness) and reduced retention intentions. Lewig et al. also showed that the positive relation between volunteer job resources and intention to remain was mediated by feelings of connectedness. Interestingly, conflicting findings have emerged around number of hours spent volunteering and burnout, with some finding a reduction in burnout with the increase in hours (Cox et al., Citation2010), whereas others found the opposite (Cowlishaw, Evans, & McLennan, Citation2010a). This may suggest that that the relationship between the two is non‐linear, as demonstrated by Windsor et al. (Citation2008).

Social and human capital

Social exchange theory seeks to explain why individuals express loyalty to an organisation (Settoon, Bennett, & Liden, Citation1996). This theory asserts that individuals develop exchanges for socioemotional and economic reasons, and that the type of exchange relationship predicts attitudes and behaviours directed at the organisation. Because volunteers do not receive remuneration for their time and work, they seek to satisfy other needs, such as need for relatedness, social interaction, and praiseworthy work (Pearce, Citation1983). For example, volunteers expect that in return for their (unpaid) labour they will receive formal or informal recognition, support, social connection, and skill development from the organisation. In the volunteering context, social exchange theory has been applied to study characteristics of the organisational environment—perceived organisational support (POS) and perceived supervisor support (PSS)—and how these affect volunteer satisfaction.

POS is defined as the set of beliefs individuals hold about how organisations value an individual's contribution, and how organisations care about the well‐being of an individual (Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchison, & Sowa, Citation1986). PSS is defined simply as the degree of support provided by a supervisor, specifically in valuing an individual's wellbeing and contributions. Both POS and PSS are social benefits derived from volunteering activity that affect volunteer satisfaction. Fallon and Rice (Citation2015) found that organisational support and recognition were the strongest predictors of emergency service volunteers’ job satisfaction, which consequently predicted intention to stay. Furthermore, they also found that perceived investment in employee development was also positively related to job satisfaction among volunteers, although not as strongly as for paid employees. Similarly, POS has been found to improve perceptions of training and satisfaction with a volunteers’ role among Australian humanitarian aid workers (Balvin, Bornstein, & Bretherton, Citation2007), to increase commitment and the perception of personal benefits among older volunteers (Tang, Choi, & Morrow‐Howell, Citation2010), and to contribute to commitment and satisfaction among sport event volunteers in Victoria (Aisbett & Hoye, Citation2014).

Supervisor support forms a large part of the POS perceptions, and has been found to promote volunteer satisfaction and intent to remain with the organisation among emergency service volunteers (Rice & Fallon, Citation2011). Despite some positive findings, there remains a need to more closely examine the POS and PSS constructs in the volunteering context. Specifically, it is unclear to what extent volunteers can distinguish their perception of organisational support from that of a supervisor. For example, Aisbett, Randle, and Kappelides (Citation2015) found that when studied together, only POS was found to predict satisfaction and intention to volunteer in the future among sport event volunteers, whereas PSS was not related to these outcomes. The authors speculated that because volunteers had little contact with the organisation and a lot of contact with their immediate supervisor, they might have “interpreted organizational support as that which was provided by their immediate supervisor acting as an agent of the organization” (p. 504).

Another line of research investigating the role of social capital in volunteering is concerned with connectedness. Volunteer connectedness is the extent to which volunteers feel connected to (a) other workers, (b) the people they are helping, (c) the tasks in their volunteering role, and (d) the values of the organisation (Huynh, Metzer, & Winefield, Citation2012). One of the key propositions tested was that volunteer connectedness plays a mediating role in the motivational process of the JD‐R model. For example, Huynh, Xanthopoulou, and Winefield (Citation2014) studied the JD‐R model with a cross‐sectional sample of 887 volunteer emergency service workers in South Australia. This study supported direct effects of volunteer job demands on emotional exhaustion and volunteer job resources on engagement and connectedness. Additionally, volunteers’ demands and resources had an indirect effect on turnover intentions that was mediated by emotional exhaustion or engagement and connectedness respectively.

Feeling of connectedness appears to be an important pre‐cursor to volunteering, but also a benefit of volunteering. Beale, Wilkes, Power, and Beale (Citation2008) found that volunteers with a cooperative family project in Sydney experienced a sense of enjoyment, relatedness (feeling like a family), and intrinsic reward (from the impact of their volunteering). Similarly, Australian blood donors reported a sense of social connection as the largest benefit derived from volunteering (Alessandrini, Citation2007). Volunteers in a remote outreach program across Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory reported several benefits of participation (Cinelli & Peralta, Citation2015). These benefits included exposure to and experience with remote Aboriginal peoples and community, increased cultural knowledge, personal learning, forming and building relationships, and skill development, but were particularly praising volunteering for the opportunity to form new relationships and build the established ones.

Social capital appears to be particularly important among volunteers in rural and remote communities. For example, Kilpatrick, Stirling, and Orpin (Citation2010) found that volunteers in rural areas mostly volunteer to contribute to their community and because of the social connections with the community. Other reasons included a passion for the content or a very positive feeling from their volunteering work. Individuals with a strong regional connection (e.g., born and raised in regional area) reported higher rates of participation in local volunteering (Davies et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, a reciprocal relationship seems to exist between participation in volunteering and sense of community (or community connectedness), as those who volunteer also report a stronger sense of community. Volunteering also contributes to reinforce the social fabric of the community through encouraging a common purpose (i.e., boosting tourism in a region; Alonso & Liu, Citation2013).

Motivation and benefits

For the purposes of the present review we tried to delineate the discussion of volunteering motivation and benefits. However, it became clear that the two are interrelated. For example, positive effects of volunteering on wellbeing appear to be moderated by volunteers’ motivation. Stukas et al. (Citation2016) found people who volunteer for other‐oriented reasons (i.e., to express their altruism) experienced a higher wellbeing. For self‐oriented reasons their results were less unidirectional. Volunteering to learn or to connect with others was positively related to wellbeing, but volunteering to escape your own troubles or for career purposes was negatively related to wellbeing. Theoretically, these differential effects make sense. The volunteering reasons that are positively related to wellbeing are aligned with autonomous motivation (i.e., volunteering for fun or because you think it is important; e.g., Gagné et al., Citation2015), whereas the reasons that are negatively related to wellbeing are aligned with controlled motivation (i.e., volunteering to avoid negative consequences or for extrinsic rewards). This line of research is fairly new, but promising, with findings in other countries showing the strong link between motivation, wellbeing, and supportive work climate. Wu and Li (Citation2018) found in a large sample of volunteers that subjective wellbeing was enhanced only for those volunteers who were motivated by autonomous forms of motivation.

Given that volunteering motivation and volunteering benefits appear to be interlinked, future research should further investigate the dynamic interplay between the two unfolding over time. Considering the evidence that volunteer motivation changes over time (e.g., Alam & Campbell, Citation2017; Cuskelly et al., Citation2002) and that different motivations are related to different benefits (Stukas et al., Citation2016), it seems entirely possible that volunteers’ motivation and the benefits they experience interact to inform the development of motivation. We propose to first clearly separate motivations from benefits and use that framework to study the development of volunteer motivation. Relatedly, researchers should also be more careful in delineating the initial motivation to join a volunteering organisation and later motivation after being in a volunteering role for some time. We have observed that occasionally researcher claim to measure initial motivation, but their samples consist of more experienced volunteers. Having provided evidence that the motivation is likely to change over the course of volunteering, we think it is important to separate the two.

REMAINING A VOLUNTEER

Volunteer turnover remains a major issue for volunteering organisations in Australia. In the previous sections of the review, we have discussed what motivates volunteers to join organisations and what potential benefits they derive from volunteering. In this section, we will focus on factors that promote a volunteer's decision to remain a volunteer, such as psychological contract and commitment.

Psychological contract

The notion of psychological contract recognises the subjective nature of employment relationships and is grounded in social exchange theory. The psychological contract is a cognitive state that is subjective and interpretative and refers to the development and maintenance of the relationship between the individual and the organisation (Taylor, Darcy, Hoye, & Cuskelly, Citation2006). In a volunteering context, the psychological contract refers to the obligations, rights, and rewards that a volunteer believes he or she is owed in return for continued work and loyalty to a manager, group, team, or organisation (Rousseau, Citation1995). In other words, a psychological contract is what a volunteer expects the volunteering experience to be like, based on what was promised by a manager, group, team, or organisation. In contrast to a traditional written contract, the psychological contract (a) is implicit rather than explicit; (b) can be shaped by experiences the volunteer has before and during the volunteering experience; and (c) can be unique for every volunteer rather than standardised for all volunteers (Stirling, Kilpatrick, & Orpin, Citation2011).

The “terms” of a volunteer's psychological contract are said to be formed even before the organisation has interacted with that volunteer. The initial terms of the psychological contract are formed through exposure to social cues or external messages that attract volunteers to the organisation in a first place (Kappelides, Citation2017). Similarly, previous volunteering experiences may influence the development of psychological contract, as volunteers bring expectations and assumptions based on their past volunteer experience and compare these expectations with their current experience. Thus, psychological contract plays an important role in influencing the individual to become a volunteer. However, even more importantly, the (mis)match of the expectations will affect volunteer's willingness to remain in their role.

After a volunteer is recruited, their psychological contract is influenced during “socialisation” experiences. For example, organisational norms and culture were found to influence the formation of the psychological contract among both traditional and episodic camp volunteers in Australia (Kappelides, Citation2017). Throughout the engagement with the organisation, psychological contracts can be solidified or transformed. There is also a risk of psychological contract breach if these early activities do not meet the expectations a volunteer had before or during recruitment.

Furthermore, volunteer expectations may depend on individual differences. For example, Findsen (Citation2016) argued that older volunteers maintain the goals of lifelong learning after retirement and expect to fulfil this goal when volunteering. Additionally, he argued that organisations and older volunteers should clearly align expectations through conversations to ensure that the needs of the older volunteers will be met. Paull et al. (Citation2017) drew similar conclusions for student volunteers. They found that organisations that put effort in their communication with the volunteers had more positive experiences with student volunteers because neither side was disappointed by the collaboration. Essentially, these studies illustrated that clear communication from the onset can prevent future misunderstandings, such as a person's reasons for volunteering not being fulfilled by the organisation, leading to volunteer withdrawal.

There are two main types of psychological contracts: transactional contracts that focus on monetary exchanges and relational contracts that focus on social and emotional concerns. Many volunteer expectations fit the relational contract concept because they are linked to social identity and emotions such as group belonging and doing something worthwhile. In support of this proposition, Stirling et al. (Citation2011) found that public recognition was supporting volunteers’ relational expectations in Tasmania. Interestingly, the study also found that volunteers have transactional expectations in that volunteers actively resist formal management practices (i.e., keeping formal records) and generally dislike the “red tape,” which is negatively associated with recruitment and retention. As such, volunteers seem to have an expectation to not be transactionally managed. Another “term” of transactional psychological contract was the absence of out‐of‐pocket expenses, or if such expenses were incurred, there was an expectation of a reimbursement. Similarly, Taylor et al. (Citation2006) found that transactional psychological contracts were not overtly relevant for the majority of rugby club volunteers in Australia. Rather, these volunteers focused on the relational contract expectations, such as benefits, sufficient power and responsibility, training and development, and a pleasant social environment. The study also highlighted distinct differences between the perceived expectations among volunteers and volunteer administrators. The latter were overly focused on transactional aspects, such as adherence to professional, legal, and regulatory standards. Paradoxically, volunteer administrators were also volunteers themselves.

When a volunteer perceives a psychological contract breach, they may feel that trust has been violated and may respond with aggressiveness, negative behaviour, and/or leave the service (Vantilborgh, Citation2015). For example, Vantilborgh et al. (Citation2012) found that helping other volunteers was perceived as an integral part of the volunteering role, although this task was not expected when joining an organisation. Consequently, some volunteers did not want to undertake this additional task, presumably as a way of reconciling a psychological contract breach. Other research found that psychological contract outcomes were related to the retention of volunteers, such that fulfilment of the psychological contract led to higher retention (Kappelides, Citation2017).

Commitment

Broadly, commitment can be defined as the degree to which an individual identifies with a particular organisation and its goals and wishes to remain an organisational member. Researchers frequently conceptualise commitment in terms of the employees’ commitment to an organisation. However, in the volunteering context, there seem to be several foci of commitment: organisations, teams, and the volunteering activity itself.

Several major theories of commitment have been applied in volunteer research. The behavioural commitment theory asserts that an individual's psychological state of commitment is a consequence of the behaviours of the individual. An individual is seen as freely choosing actions, committing to these actions, and feeling obliged to follow through with these actions (Salancik, Citation1977). Thus, commitment is associated with affective attachment to a rewarding activity or behaviour. For example, an individual who freely chooses to volunteer will commit to the volunteering behaviour and, consequently, feels obliged to follow through with volunteering. However, volunteer organisations have been described as having behaviourally weak environments with low performance expectations. The transactional commitment theory suggests that commitment arises out of an individual's investment of resources and subsequent rewards (Becker, Citation1960). In other words, individuals are committed because they perceive they will sustain a significant loss (of time, effort, and money) if they do not maintain membership in the organisation. This type of commitment might be less applicable to the volunteering workforce, because volunteers do not have to sacrifice pay or other tangible benefits if they leave the organisation (Boezeman & Ellemers, Citation2007). Indeed, research conducted in the US confirmed that continuance commitment (related to personal sacrifice) was irrelevant among board member volunteers (Dawley, Stephens, & Stephens, Citation2005).

In contrast to other approaches, the attitudinal commitment theory focuses on the desire of the individual to remain in an organisation (Meyer & Herscovitch, Citation2001). Here, affective commitment arises from feelings of cohesion or involvement with an organisation, which are driven by perceived value congruence, feelings of care for the organisation, pride, and willingness to put in extra effort (Mercurio, Citation2015). In the volunteering context, affective organisational commitment has been found to predict turnover among committee members in Queensland sporting organisations (Cuskelly & Boag, Citation2001). In addition, Cuskelly and Boag found that commitment declined over time for those volunteers who later left the organisation, possibly indicating that the turnover decision was not sudden, but rather accumulated over time. Interestingly, in a different study of volunteer sports administrators by the same first author (Cuskelly et al., Citation2002), it was found that affective organisational commitment decreased over time for all volunteers. The attitudinal commitment theory is underpinned by social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979), which argues that individuals think of themselves as psychologically linked to the groups and organisations to which they belong. In application of this theory to the volunteering context, Boezeman and Ellemers (Citation2007) found that pride and respect in the organisations were positively related to affective organisational commitment among volunteers in the United States.

Obligatory commitment theory conceptualised commitment as an individual's predisposition or mindset of obligation to an organisation, which arises from the specific norms that are internalised by the individual (Meyer & Allen, Citation1984). It is interesting to note that the notion of obligation and duty frequently features in the commitment theories. Although volunteering is rarely conceptualised as an obligation, about 8% of Australian volunteers report that they volunteer because they felt obliged (ABS, Citation2015). Recently, Gallant, Smale, and Arai (Citation2017) designed and validated a scale to measure the obligation to volunteer as commitment (OVC) and obligation to volunteer as duty (OVD). This constitutes a novel and—in our opinion—exciting area of volunteering research.

Overall, we note that the focus of much Australian research is on volunteer motivation and benefits, rather than other processes that describe volunteering activities. This suggests the need to expand the pool of volunteering phenomena studied to fully capture the complexities of volunteering. For example, we found very little research on volunteer commitment conducted in in Australia, but insights from studies conducted elsewhere are promising, and hence, should be more rigorously replicated in Australia.

VOLUNTEER WITHDRAWAL

A study of volunteer ambulance officers in Australia and New Zealand found that exit rates increased after 2.5 years of service (Fahey, Walker, & Lennox, Citation2003). Although exit trends and reasons are frequently studied, there does not seem to be a consensus on how long a volunteer should stay with an organisation or a clear taxonomy for why volunteers leave their organisations. In our review we found that researchers have studied a wide array of volunteer withdrawal reasons (e.g., lack of support or training, bureaucratic processes, burnout, stress, work‐home interference, mismatched expectations, competing interests). Most of these withdrawal reasons seem comparable to the turnover reasons among paid workers. However, volunteers are not bound to an organisation for financial reasons and thus are able to leave more easily. This section focusses on three broad categories of volunteer withdrawal: interaction with other individuals, stress from volunteering, and other life domains interfering with volunteering.

Interaction with other individuals

Some studies have investigated if the interaction with paid colleagues can prompt volunteers to withdraw from their role. Huynh, Winefield, Xanthopoulou, and Metzer (Citation2012) found that conflict with paid employees was negatively related to volunteers’ intention to remain. This study illustrates the divide between staff and volunteers that is mentioned in some research. Prabhu, Hanley, and Kearney (Citation2008) found that volunteers found the lack of acknowledgement from staff and supervisors a less enjoyable component of volunteering. Both staff and volunteers agreed that volunteers had few opportunities to voice their opinions.

In extreme cases, negative interactions with other individuals will lead to bullying, which will consequently prompt volunteer withdrawal. Although bullying has been extensively studied in the workplace context, the research on bullying in the volunteering context is only emerging. An exploratory study of 136 volunteers and volunteer managers in Australia found one third of the respondents reporting that they had been subjected to bullying behaviours (Paull & Omari, Citation2015). Examples of bullying behaviours experienced by volunteers included intimidation, abuse from clients and the public, and gossiping and exclusion, which are also common in the traditional workplace. However, some bullying behaviours were unique to volunteer setting, for example, pressure to undertake duties not within volunteer roles or being “bullied” into volunteering. Although not conceptualising it as bullying, a study of volunteers with an Australian government community service program found that dealing with difficult or demanding clients was a challenge for volunteers, potentially leading to turnover (Warburton, Smith‐Merry, & Michaels, Citation2013).

Stress from volunteering

Several studies have found that volunteers can experience significant stress in their roles. For example, Cinelli and Peralta (Citation2015) found that being a role model for Indigenous youth caused stress in some volunteers. However, they also found that overcoming this stress could result in pride and personal growth. Phillips et al. (Citation2014) found that 22% of hospice volunteers indicated experiencing some burnout from their volunteering, which is lower than paid employees in comparable professions. Based on their findings, Phillips et al. concluded that the rewards of volunteering outweigh the negative consequences. Ironically, there is some evidence that the most active volunteers are also most susceptible to burnout. Byron and Curtis (Citation2002) found that higher levels of activity in a volunteering group were associated with higher levels of burnout. Moreover, the feelings that their volunteering group did not get important tasks done and did not set priorities were also related to higher levels of burnout. The authors argue that creating clear and realistic expectations could reduce burnout experienced from volunteering.

Although burnout does not seem to affect a large portion of the volunteer population, it is important to note that some research indicates that volunteers may receive less support than paid employees (e.g., Prabhu et al., Citation2008). Some volunteering roles put the volunteers in potentially traumatic circumstances that can severely impact their mental health. Doley, Bell, and Watt (Citation2016) found that 29% of the volunteer firefighters who were deployed during Ash Wednesday Bushfire disaster qualified for a PTSD diagnosis. These findings clearly illustrate that volunteers who have potentially traumatic tasks need access to coping support that is comparable to the support that paid professionals in similar roles have access to. Volunteers who do not get the correct support may resort to ineffective coping strategies, making them more susceptible to threats to their mental health, and consequently, withdrawal.

Volunteer withdrawal and other life domains

Cowlishaw and colleagues have used the JD‐R model to investigate the precursors and outcomes of conflict between volunteering work and family life, a topic that has otherwise received little attention. Volunteering often competes for time with activities in other life domains, most notably family life. This line of research started with a review (Cowlishaw, Evans, & McLennan, Citation2008) that found volunteering work potentially has disruptive effects on family life. This review was subsequently followed up by several field studies with volunteer firefighters. Cowlishaw et al. (Citation2010a) described how on‐call emergency activities and post‐traumatic stress increased volunteering‐family conflict. The increased volunteering‐family conflict subsequently affected volunteer burnout. Additionally, Cowlishaw, Evans, and McLennan (Citation2010b) found that marriage quality suffered when demands from volunteering hindered a volunteer's family contributions, which ultimately resulted in more stress for the volunteer's partner. Furthermore, Cowlishaw, Birch, McLennan, and Hayes (Citation2014) found that volunteer firefighters experienced more volunteering‐family conflict when they had higher operational demands (i.e., the number of call‐outs), which in turn negatively affected the volunteers’ intention to remain. These findings were mimicked by Huynh, Winefield, et al. (Citation2012), who found that volunteering‐home conflict subsequently affected retention intentions for hospice volunteers. Conversely, Cowlishaw et al. (Citation2014) also found that volunteering‐family facilitation was improved by training quality and effective leadership, meaning that volunteering experiences can also positively spill over to the family domain. Together, these findings illustrate how volunteers can be overworked and stressed from their volunteering work, which leads to withdrawal. Furthermore, this means that the effects of volunteering are not isolated to just the volunteering domain, but also spill over to other major life domains.

Continuity theory

Despite some research reviewed in the previous sections, little remains known about volunteer withdrawal. One potential avenue for theorising in this domain is the continuity theory. The continuity theory suggests that individuals maintain well‐being by maintaining established patterns of behaviour during status transitions and throughout life in order to preserve role stability (Atchley, Citation1989). Even when an individual is presented with changing normative expectations or possible disruptions in the availability of social roles, they will attempt to preserve continuity of attitudes, dispositions, preferences, and behaviours. It then follows that prior behaviours and attitudes are the most significant predictors of present or future behaviour. For example, Moorfoot, Leung, Toumbourou, and Catalano (Citation2015) found that young adolescents who are volunteering in their early teens are more likely to volunteer when they become young adults.

Continuity theory would also suggest that individual maintain their volunteering role even when faced with significant life events, such as improved or worsened finances, disruption of the family/household structure, changing job, and so on. Beatton and Torgler (Citation2018) analysed data from 10 waves of the HILDA survey, and, in support of continuity theory, found that both improved and worsening finances contribute to increase in volunteering, albeit the effects were somewhat different across wealth/income groups. However, they also found that other life events that interfere with an individual's free time, such as moving house, being promoted, getting married, becoming pregnant or having a child, reduce volunteering. Other events that interrupt normal life, such as death of a spouse, job loss, job change, separation from a partner, and injury also reduce volunteering. Thus, more research is needed to investigate when and why volunteers withdraw or remain in face of a challenging life circumstances.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION