Abstract

Research evidence has shown that in childhood, a secure attachment to a reliable caregiver is important for future mental health and well‐being. The theoretical and research basis for attachment theory continues to grow. As attachment theory has become more widely adopted there are challenges and opportunities both theoretically and in terms of its clinical use. Disordered attachment has been linked to psychopathology including internalising and externalising disorders. However, there are ongoing implications for researchers and clinicians as only the most extreme forms of attachment disorders are included in the current diagnostic systems. A wide range of reliable and validated observational assessments to classify attachment are available. Owing to the growing popularity of attachment‐based interventions there is a need to develop assessments which are practical for use in clinical settings. The use of attachment‐based parenting interventions in clinical settings is increasing as they have been found to be effective and relevant. This growth presents opportunities to further refine these interventions, so they are easy to deliver in clinical practice and tailored to different populations. Attachment‐based interventions are being widely used in Australia, and this has led to a need to understand and adapt the theory, assessments, and interventions to this context. Attachment‐based interventions demonstrate the importance of relationships and provide an important tool to support children and families. For psychologists here in Australia there are many opportunities to develop measures and interventions based on attachment theory that fit into the Australia context.

Key words:

What is already known about this topic

There is a strong theoretical and research basis for attachment theory.

There is growing research evidence that supports attachment‐based parenting interventions.

There is increasing evidence showing a relationship between a dysfunctional attachment in childhood and poor outcomes later in life.

What this topic adds

Diagnosis of attachment problems in childhood remains fraught due to the lack of relevant diagnostic criteria.

The growing clinical use of attachment‐based interventions offers some challenges which require more research.

Attachment‐based assessments and interventions are being used in Australia with some preliminary research demonstrating positive outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

Attachment is the biologically based need by infants to maintain proximity, particularly at times of distress, to their caregivers. This proximity helps them to regain emotional and psychological balance which provides them with the confidence to return to exploring their world. The research evidence is increasingly showing that early life experiences and close relationships have a large impact on later mental health and wellbeing (Englund, Kuo, Puig, & Collins, Citation2011; Lyons‐Ruth, Bureau, Holmes, Easterbrooks, & Brooks, Citation2013; Sroufe, Citation2005). Attachment theory fits well in clinical settings with many psychologists looking for innovative and relationally based interventions with which to treat clients. There is a growing body of research which has demonstrated the effectiveness of attachment‐based interventions in assisting parents and children to build more secure attachments. As the research base has grown so too has the popularity of parenting interventions based on attachment theory. Recent reviews have discussed the potential of attachment‐based interventions particularly in terms of their strong theoretical underpinnings, the known links between attachment and psychopathology, and the growing research base around effective interventions (Barlow et al., Citation2016; Rose & O'Reilly, Citation2017; Woodhouse, Citation2018). These interventions are gaining acceptance by clinicians and participants; however, there is much work to do to ensure they have the same level of support of other widely used therapies.

There have been calls for further research into evidence‐based assessments and parenting interventions based on attachment theory both in Australia (National Health and Medical Research Council, Citation2017) and overseas (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Citation2015). There is now considerable research evidence which suggests the universality of attachment principals and patterns across cultures including North American and European populations as well as in Africa, East Asia, Latin America, and Israel (Mesman, Van Ijzendoorn, & Sagi‐Schwartz, Citation2016). However, it is important to consider attachment within the social milieu within which children live. As attachment‐based interventions are widely used in Australia, there is a need to recognise the cultural context particularly as research indicates that in Aboriginal culture the concept of attachment may be interpreted more broadly (Ryan, Citation2011; Yeo, Citation2003). This article reviewed theory, psychopathology, diagnosis, assessments, and interventions with a focus on the Australian context. The discussion focuses on the challenges and opportunities for attachment theory both conceptually and clinically in the future.

A systematic literature review was conducted in which a comprehensive search of multiple relevant subject databases was undertaken. The databases which were searched included Google Scholar, Psychnet (APA), ProQuest, JSTOR, SAGE Journals, Taylor and Francis Online, Web of Science, and Psychiatry Online. These searches were conducted in 2017 and 2018. Both published and unpublished manuscripts were considered, however unpublished research may have been missed if it was not included in the databases. Search terms which were used included attachment theory, attachment parenting, attachment disorders, attachment styles, Australia(n) attachment theory, attachment theory aboriginal culture, attachment interventions, attachment assessments, strange situation, and parenting programs. While no specific review protocol was used the author made every effort to search for published materials which were recent, widely cited, seminal works, or review articles. This review placed a particular emphasis on sourcing relevant articles with an Australian focus.

Attachment theory

A secure attachment according to Bowlby (1969/1982) is the deep and enduring emotional bond between a parent and child. A parent who is accepting, sensitive, available, and cooperative is more likely to have a child with a secure attachment (Ainsworth, Citation1969). The main tenet of attachment theory is that early environmental influences effect the development of character (Bowlby, Citation1940). Bowlby (Citation2007) established that children need a warm, intimate, and consistent relationship with a caregiver. Further, Bowlby (Citation1960) identified that grief and mourning occur when an attachment figure is unavailable and a succession of substitute attachment figures leads to the child becoming unable to form deep relationships with other people. Cassidy (Citation2016) finds there have been no serious challenges to this idea despite over 40-years of research and that recent research has primarily served to extend and enrich Bowlby's ideas. Ainsworth, Blehar, and Waters (Citation1978) developed a classification system based on patterns of attachment. These patterns include securely attached children who have sensitive and responsive parents and as a result are comfortable when exploring and upon reunion; anxious‐avoidantly attached children who feel anxious when they are separated from their parents but are not calmed by reunion with their parents; and anxious‐resistant or insecurely attached children who are avoidant of their parents and are not distressed by separation from their parents. Disorganised/disoriented attachment was added as a fourth category by Main and Solomon (Citation1990). This is a broad category encompassing a wide range of infant behaviours that occur when there is a lack of the expected attachment behaviours or a confusing mix of attachment behaviours present. To ensure the validity of the constructs discussed, in this article the terminology stated in the research to identify the classification will be used. The terms insecure and dysfunctional attachment are broader terms used to encompass all types of attachment which are not secure. The concept of attachment has been supported by theoretical advancements in evolutionary theory, neuroscience, and physiology (Coan, Citation2016; Ehrlich, Miller, Jones, & Cassidy, Citation2016; Hane & Fox, Citation2016; Simpson & Belsky, Citation2016). However, there is still a need for theoretical reviews to keep up to date with the ever‐growing research base.

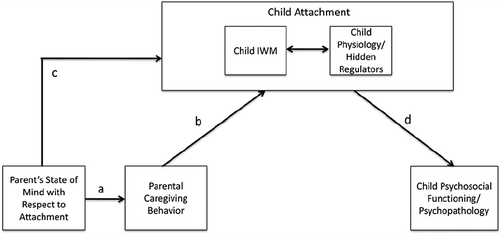

There have been three main reviews of the theoretical underpinnings of attachment theory (Cassidy, Jones, & Shaver, Citation2013; Masters & Wellman, Citation1974; Thompson & Raikes, Citation2003). Each of these reviews demonstrate the advances made in clarifying the theoretical components of attachment theory. Cassidy et al. (Citation2013) in their review find attachment theory has generated a half century of creative and innovative research. They proposed a simple model of attachment‐related processes, which has emerged from recent theoretical advancements (Figure 1. A Simple Model of Attachment‐Related Processes). Sroufe (Citation2016) described attachment theory as revolutionary. He credited it with transforming psychology from a one‐person concept to a dyadic and relational concept. In the Australian context is it also important to consider the cultural implications of using the concept of attachment to make decisions about parenting. Attachment theory was developed based on cross‐cultural research (Ainsworth, Citation1967). Ryan (Citation2011) found many connections between traditional Aboriginal forms of child rearing and attachment theory, particularly in terms of security and protection. Within these connections the concept of “kanyirninpa” or “holding” which is used in some areas of Australia to describe the nurturing acts which occur from childhood to adulthood were emphasised. This concept is similar to attachment, but is grounded in the notion that this idea is very broad in Aboriginal culture and applies not only to parents but also attachment to kin, community, and land. In terms of the applicability of the attachment construct to Aboriginal groups there is little research. However Yeo (Citation2003) urges that any use of the core hypotheses of attachment theory when applied to Aboriginal peoples be based on Aboriginal cultural values. Despite the many commendations attachment theory has received it is important to consider its cross‐cultural implications. There are also other areas which need more research, and these are examined further in the discussion section.

Attachment and links to psychopathology

Theoretically, four mechanisms have been proposed to link attachment and psychopathology (DeKlyen & Greenberg, Citation2016). First, observed behaviours such as those that are disruptive (for example, non‐compliance and displays of anger) have the ability to regulate the caregiving response. If the infant uses this strategy regularly it may lead to maladaptive behaviour patterns. These behaviours also serve to maintain the connection with the caregiver by increasing the need for the parent to pay attention to the child. Second, the emotion‐regulatory processes that develop within an attachment are related to a range of physiological changes. In a secure attachment these changes would lead to the child developing the self‐regulatory skills needed to manage their emotions independently. However, if the attachment is disordered these processes may lead to the child being less able to self‐regulate. Third, the attachment relationship helps to shape the child's internal working models (IWMs) of self and others. In dyads where unhealthy schemas are developed this could lead to dysfunction later in life. Finally, there are motivational processes, including a general social orientation, that is either more positive or resistant that can be passed from the parent to the child. DeKlyen and Greenberg (Citation2016) reported that there is growing evidence of a link between disrupted or dysfunctional attachment and psychopathology in terms of both internalising and externalising behaviours.

Research has linked disordered attachment patterns with externalising behaviours (oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, aggression, and antisocial behaviour) and internalising disorders (anxiety disorders and depression). Research indicates that externalising disorders are more related to disorganised attachment and insecure attachment has more links to internalising disorders (Colonnesi et al., Citation2011; Fearon & Belsky, Citation2011; Futh, O'Conner, Matais, Green, & Scott, Citation2008; Moss et al., Citation2006; Nowakowski‐Sims & Rowe, Citation2016; Pasalich, Dadds, Hawes, & Brennan, Citation2012; Shaw, Keenan, Vondra, Delliquadri, & Giovannelli, Citation1997). DeKlyen and Greenberg (Citation2016) also reported findings demonstrating links between disordered attachments and attention‐deficit/hyper activity disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, post‐traumatic stress disorder, autism spectrum disorder, gender dysphoria, and eating disorders.

Stovall‐McClough and Dozier (Citation2016) reviewed the literature and found links between a dysfunctional attachment classification and adult psychopathology. In the Minnesota Longitudinal Study of Risk and Adaptation, connections were found between dissociative symptoms in adolescence and early adulthood and a disorganised attachment (Carlson, Citation1998; Sroufe, Egeland, Carlson, & Collins, Citation2005). Further connections have been identified between anxiety disorders in adolescence and a resistant attachment (Warren, Huston, Egeland, & Sroufe, Citation1997). Stovall‐McClough and Dozier (Citation2016) report there are links which have been identified between attachment and adult mood disorders, anxiety disorders, dissociative disorders, eating disorders, schizophrenia, and personality disorders. Alternatively, secure attachment has been shown to provide resilience against stress. Further research from the Minnesota study has shown that even children who have high‐level behavioural problems with a secure attachment in preschool were found to have significantly fewer behavioural problems later in childhood (Sroufe, Egeland, & Kreutzer, Citation1990). Previous research from the same study found that children with a history of secure attachment are significantly less likely to have behaviour problems in the context of high family stress (Pianta, Egeland, & Sroufe, Citation1990). This research demonstrates there are links between attachment and outcomes for children.

Dysfunctional attachment has shown clear links to a range of psychopathologies. The diagnostic criteria available do not reflect these links, and currently options are limited. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual – Fifth Edition (DSM‐5), included criteria for reactive attachment disorder (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD‐11), classify reactive attachment disorder of childhood and a disinhibited attachment disorder of childhood (World Health Organization, Citation2018). These diagnoses have been developed based on a small number of children from extreme caregiving situations who were very impaired (DeKlyen & Greenberg, Citation2016). These diagnoses are useful in that they acknowledge the link between attachment and psychopathology. Zeanah (Citation1996), however, finds that these diagnoses are not based on attachment theory research and in many ways are inconsistent with this theory. Zeanah finds these diagnoses are more aligned with a maltreatment syndrome than on Bowlby's (Citation1969) theoretical understanding of attachment disorder. Based on developmental attachment research, Zeanah and Boris (Citation2000) developed alternative criteria for attachment disorders including a secure base distortion and disinhibited attachment disorder. More recently Zeanah and Gleason (Citation2010) identified two subtypes “emotionally withdrawn/inhibited” and “indiscriminately social/disinhibited”. Unfortunately, these criteria were not incorporated into the most recent revision of the diagnostic classification systems as there is not a clear consensus as to how attachment patterns should be classified.

Attachment‐based measures of the parent–child relationship

In the 1950s, Mary Ainsworth started to develop a research methodology to measure Bowlby's theoretic ideas. The development of this methodology was innovative as it provided direct behavioural observations of attachment in practice settings. Ainsworth was the first to start to classify mother–child relationships into patterns including positive, ambivalent, and non‐expressive, indifferent, or hostile (Bowlby, Ainsworth, Boston, & Rosenbluth, Citation1956). Ainsworth later brought together these ideas into the Strange Situation Procedure where an infant's reactions are observed when the mother departs the room, a stranger enters, and upon the mother's return. The aim is to assess the relationship between a child and caregiver in terms of attachment style (Ainsworth et al., Citation1978). This along with similar assessment procedures remains the gold standard in the assessment of attachment and primarily focusses on the construct of parental sensitivity.

Mesman and Rossanneke (Citation2013) in their review of measures of parental sensitivity found that Ainsworth's original sensitivity scale (Ainsworth, Bell, & Stayton, Citation1974) is still commonly used today. Observational assessment continues to be the primary way to measure attachment security and parental sensitivity with no self‐report measures available currently. Mesman and Rossanneke (Citation2013) identified over 50 other observational instruments which have been developed from Ainsworth's sensitivity scale. The most commonly used measures they identified included the CARE‐Index (Crittenden, Citation2001), Coding Interactive Behaviour (Feldman, Citation1998), Emotional Availability Scales (Biringen, Robinson, & Emde, Citation1993), Erickson scales (Erickson, Sroufe, & Egeland, Citation1985), Global Ratings of Mother‐Infant Interaction (Murray, Fiori‐Cowley, Hooper, & Cooper, Citation1996), Maternal Behaviour Q‐Sort (Pederson & Moran, Citation1995), NICHD‐SECCYD (Owen, Citation1992), and the Parent–Child Early Relational Assessment (Clark, Citation1985). Mesman and Rossanneke (Citation2013) discuss the need for further research on these measures in differing populations including fathers and non‐parental caregivers.

Researchers such as Cadman, Belsky, and Pasco Fearon (Citation2018) have started to work towards developing a shorter adaptation of a similar observational measure. They recently created a shortened version of the Attachment Q‐Sort (AQS) named the Brief Attachment Scale (BAS‐16) as a screening instrument for insecure attachment due to the unsuitability of the AQS and the SSP for clinical settings. The BAS‐16 is a screening measure and was found to have comparable convergent, externalising and concurrent validity with the full AQS. Having validated and reliable screening measures such as the BAS‐16 is vital for both clinical practice and research purposes.

Solomon and George (Citation2016) in their review of methods for assessing attachment security in infancy and early childhood conclude with an encouragement for research to develop an efficient measure which could be used in more large scale and intervention studies. However, they urged caution based on the work of George and West (Citation2012). This is because the parents' “defensive exclusion” or the rejection of information from conscious awareness would need to be taken into account. The idea that a parent's unconscious or conscious response bias could influence the results of a self‐report measure of attachment is one of the primary reasons this type of instrument has not been developed.

In summary Ainsworth developed a measure which continues to be widely used and has led to a proliferation of similar instruments. The need to refine the number of instruments will be discussed later in this article. The focus of the majority of attachment research remains on observational methods. Two other areas are identified which include the need for screening measures which can be used in routine clinical practice and the need for self‐report measures for parents.

Attachment‐based parenting interventions

Attachment theory and research can be linked to interventions through IWMs. A parent's IWMs effect their attachment to their child and their parenting and caregiving behaviours (Berlin, Zeanah, & Lieberman, Citation2016). These behaviours then shape the child's attachment to the caregiver. In this conceptualisation, IWMs anticipate, interpret, and guide interactions in relationships under which a parent selects their parenting behaviour including their sensitivity to their child. A parent who is sensitive towards their child will increase the likelihood of the child having a secure attachment. Berlin et al. (Citation2016) reported that following from this model a parent's IWMs and behaviours are two areas that should be targeted for intervention. The goal of attachment intervention is to change longstanding IWMs (Bretherton, Citation1992). Therapy should focus on changing the parent's IWMs and the resulting behaviour as a way of increasing their sensitivity to their child. This leads to an increase in their child's attachment security.

There have now been a number of reviews and meta‐analyses undertaken to clarify what works and for whom. Woodhouse (Citation2018) in her review for a special issue found there are a number of attachment‐based interventions which aim to improve the sensitivity of caregiving and address IWMs. Bakermans‐Kranenburg, Van Ijzendoorn, and Juffer (Citation2003) found in their meta‐analysis that interventions with five sessions were as effective as those with 5–16 sessions and that interventions with over 16 sessions were less effective. Barlow et al. (Citation2016) found that parent‐infant psychotherapy, video‐feedback and mentalisation‐based programs are all effective in improving attachment related outcomes and that these can be delivered through both home visiting and parenting programs. Rose and O'Reilly (Citation2017) found that despite adopted children being prone to developing attachment difficulties there was insufficient empirical information for conclusions from their review. These reviews primarily include the four most commonly used interventions outlined in the following sections.

The most promising prevention and intervention programs that support attachment security include: child–parent psychotherapy (CPP; Lieberman & Van Horn, Citation2005, Citation2008), the attachment and bio‐behavioural catch‐up program (ABC; Dozier, Lindheim, & Ackerman, Citation2005), the video‐feedback intervention to promote positive parenting program (VIPP; Juffer, Bakermans‐Kranenburg, & Van Ijzendoorn, Citation2008), and the circle of security program (COS; Powell, Cooper, Hoffman, & Marvin, Citation2014). A brief review of these interventions and the research evidence for them is discussed in the following sections.

Child–parent psychotherapy

CPP is an intervention for parents with children under 5-years of age. Developed by Lieberman and Van Horn (Citation2005, Citation2008) as a 12‐month, manualised intervention. It is primarily targeted at parents of children who have faced stress and trauma in their early years. Implemented with families from a wide range of income levels and ethnicities, the treatment attempts to help parents see the role that unresolved childhood experiences play in shaping their IWMs, which in turn, affects their attachment with their children. The aims of this treatment are for the therapist to use empathic guidance to assist the parent to connect with the emotions of distressing childhood experiences and to understand the impact of these unresolved conflicts on their current parenting (Berlin et al., Citation2016). CPP was found to have stronger effects with higher risk children, defined as children who have experienced more traumatic and stressful life events (Ghosh Ippen, Harris, Van Horn, & Lieberman, Citation2011). This intervention has demonstrated effectiveness in terms of improving attachment and mental health outcomes.

Attachment and bio‐behavioural catch‐up

ABC is a 10 session, home‐based program developed by Dozier et al. (Citation2005). The goals of ABC are to help children aged 6 months to 2-years who have experienced adversity to develop attachment security and biological regulation with two randomised control trials including children placed in foster care (Bick & Dozier, Citation2013; Bick, Dozier, & Moore, Citation2012). The program targets adoptive, birth, and foster parents by using video‐feedback and parent coaches. These coaches have three main behavioural targets for parents. These include helping the parent to develop more nurturance, learn to follow their child's lead, and reduce any frightening caregiving behaviour (Berlin et al., Citation2016). They particularly focus on overriding the parent's history of being parented and their non‐nurturing instincts. This therapy has shown strong efficacy and positive effects in terms of biological and behavioural outcomes. It is considered appealing as a community‐based intervention as it is shorter than some of the other interventions (Berlin et al., Citation2016). However, as with CPP it is resource intensive. A skilled therapist who can conduct home‐visits and provide videotaping equipment is required.

Video‐feedback intervention to promote positive parenting

VIPP is the briefest intervention with only four to six 90‐minute sessions. Developed by Juffer et al. (Citation2008), this intervention uses written material and videotaped interactions. The target population includes children 1–3-years of age with a risk of externalising behaviour problems. The primary therapeutic technique of VIPP is called “speaking for the child”. This includes helping the parent to notice their infant's signals, interpret them, and respond promptly (Juffer et al., Citation2008). This technique includes getting the parent to attend to sensitivity chains where the parent's responsiveness promotes positive responses from the child. VIPP has been found to be more effective with highly reactive or irritable children, as well as with children considered to have more genetic vulnerability in terms of having dopamine receptor polymorphism or D4DR 7‐repeat allele (Bakermans‐Kranenburg, Van Ijzendoorn, Mesman, Alink, & Juffer, Citation2008; Bakermans‐Kranenburg, Van, Pijlman, Mesman, & Juffer, Citation2008; Velderman, Bakermans‐Kranenburg, Juffer, & van, Citation2006). Program effects on infant–mother attachment security have not been obtained; however, VIPP has shown positive results for sensitive caregiving behaviours and positive child outcomes.

Circle of security

Hoffman, Marvin, Cooper, and Powell (Citation2006) developed the COS protocol, a widely used intervention which has been adapted to a number of different populations. It targets parents of children aged 0–5-years. Research which has assessed the effectiveness of the COS protocol has focused on high‐risk populations such as teen mothers and parents of irritable babies. It has been used with adoptive, birth, and foster parents in residential care facilities, outpatient clinics, and community agencies. This intervention focuses on parents of children with difficulties including aggression, withdrawal, disruptive behaviour, emotional regulation, and impulse control. This intervention does not include the child in the therapy but teaches attachment theory to parents using simple COS graphics and video reviews. It attempts to change parent's working models of attachment, identify the parent's core sensitivities, and their biggest parenting challenges. Berlin et al. (Citation2016) reported that it has a developing research base. The three program evaluations, which have been completed have all shown positive effects. Hoffman et al. (Citation2006) examined toddler/pre‐schooler and caregiver dyads and found significant within‐subject changes in attachment classification. Cassidy et al. (Citation2010) found that using the Circle of Security Perinatal Protocol with mothers in a jail diversion program resulted in post‐intervention attachment classification which was similar to low‐risk samples. Finally, Cassidy, Woodhouse, Sherman, Stupica, and Lejuez (Citation2011) used a randomised control trial to test a brief intervention and found that highly irritable infants had significant treatment effects.

Another version which has been developed is the Circle of Security – Parenting (COS‐P). COS‐P does include versions which are 8–10-weeks in length. A recent randomised control trial examined the 10‐week version as part of the Head Start program. They assessed outcomes using both observational and self‐report measures and found main effects for maternal unsupportive (not supportive) responses to infant distress (Cassidy et al., Citation2017). Once maternal age and marital status were controlled effects were also found for child inhibitory control. No effects were found for the child's attachment, behaviour problems, or cognitive flexibility. Another recent study examined adding COS‐P to a comprehensive parent–child intervention in Swedish infant mental health clinics (Risholm Mothander, Furmark, & Neander, Citation2017). They used the Emotional Availability (EA; Biringen, Derscheid, Vlliegen, Closson, & Easterbrooks, Citation2014) scales to assess the capacity of the caregiver and child to share an emotionally healthy relationship and the Working Model of the Child Interview (WMCI) (WMCI; Zeanah, Benoit, & Barton, Citation1996) to assess parents' experiences of their infant and their thoughts on their child's future and their representation of their relationship with their infant. They found significant increases in the proportion of balanced representations and the proportion of emotionally available interactions. These studies demonstrate that shorter term attachment‐based interventions can be effective in helping parents make some important changes in their relationship with their child.

The fundamental tenet of COS is that “having a primary caregiver who consistently provides both comfort (a safe haven) and encouragement (a secure base from which to explore) optimises a child's chance of growing into an adult who can rely on both self and others and successfully navigate the world” (Powell et al., Citation2014, p. 23). In Australia, 381 professionals and organisations are listed as facilitators (Circle of Security, Citation2018). Slade (Citation2016) describes the program as dominant in the theory and practice of psychotherapy. COS and its variant have engaging graphics and the number of facilitators demonstrates its popularity with professionals, however even in its most reduced version at eight group sessions it could still be difficult for some parents to attend consistently.

In the Australian context Huber, McMahon, and Sweller (Citation2015) found that caregiver reflective functioning, caregiving representations and the level of child attachment security increased after the 20‐week Circle of Security intervention. Huber, McMahon, and Sweller (Citation2016) found in another study that for parents of children between 1 and 7-years of age the COS intervention was effective in reducing parenting stress and psychological symptoms. The Boomerangs Parenting Program was based on the COS protocol but adapted for Aboriginal parents and their children (Lee, Griffiths, Glossop, & Eapen, Citation2010). The Boomerang program's objective was to use a video‐based intervention to provide parent education and psychotherapy with an aim to observe and improve parents' care giving capacity. The program had 20 sessions including two camps and provided activities such as child/parent interactional guidance, family games, craft, book reading and play, fathering and mothering business, self‐care, and baby massage. Using three case studies they found the mothers gave positive feedback on the program in terms of increasing awareness, sensitivity and responsiveness. Research has also examined the effects of COS training on Australian and New Zealand practitioners and found that after COS training they showed significantly greater attachment understanding and provided more attachment‐focused descriptors (McMahon, Huber, Kohlhoff, & Camberis, Citation2017). Together these results are encouraging in terms of the effectiveness of COS in the Australian context and show there is potential for it to be successfully adapted to Aboriginal populations. It also demonstrates that COS is viewed as beneficial by practitioners.

The National Health and Medical Research Council (Citation2017) reported that there are research opportunities to see which attachment‐based interventions are most effective in the Australian context. With a wide range of practitioners using Circle of Security in Australia there are many opportunities for research with different Australian populations. This would provide further evidence that focusing on attachment as a point of intervention can have positive real‐life impact.

DISCUSSION

Attachment theory fits well in clinical settings and clinicians recognise the applicability to their clients particularly in the area of parenting. However, there are already a number of therapies primarily based on CBT principles already available. The primary theoretical difference between CBT and attachment‐based interventions is that attachment theory places relationship‐based IWMs as the primary intervention point for positive change. There are also similarities between the core beliefs of cognitive therapy and IWMs. Bowlby borrowed the idea of IWMs from cognitive psychology and described how experiences can be represented by a script or working model (Waters & Waters, Citation2006). There are conceptual similarities between IWMs, and the core beliefs or schema described in cognitive psychology. However, what sets attachment‐based interventions apart is that they are firmly placed in the context of the relational milieu. Attachment‐based interventions focus on the way IWMs are co‐created in interactions and how relationships can also be the main driver for change in these scripts.

In 1976 Aaron Beck (Beck, Citation1976), questioned if CBT a new psychotherapy, could challenge psychoanalysis and behaviour therapy which were widely used at that time. Since that time CBT has been extensively researched and is widely used clinically. In 2012 there were 269 meta‐analytic studies of CBT (Hofmann, Asnaani, Imke, Sawyer, & Fang, Citation2012). Along with this research base Gaudiano (Citation2008) proposed that the reasons for CBT's popularity included its common sense and clear principles, the numerous self‐help books available, and its short‐term and structured nature. Furthermore, he discussed the ease with which CBT is disseminated and implemented with manualised treatments that can be provided to clients over a short period of time. Similarly, Bakermans‐Kranenburg et al. (Citation2003) found attachment‐based interventions that are shorter and more focused were more successful. CBT also targets specific populations such as CBT for eating disorders and CBT for anxiety disorders. As attachment‐based interventions are more recent there is a need for research into more tailored programs for different populations. The popularity and wide‐spread use of CBT is undeniable. In terms of therapeutic popularity CBT provides a good framework of how a therapy gains public and clinician approval. This framework was considered as part of the challenges and opportunities for attachment theory in the future.

Researchers need to ensure the theory, diagnostic criteria, assessments, and interventions based on this attachment theory are useable in the Australian health care system. Particular focus should be placed on the lack of clear diagnostic criteria and the paucity of self‐report measures as they affect the usability of these interventions in the Australian health care sector. Attachment theory faces many challenges and opportunities in terms of its theoretical conceptualisation, links to psychopathology and diagnosis, clinical assessment, and broadening the evidence base of the interventions.

Challenges and opportunities for the theory

There are a number of areas within attachment theory which with further research could be strengthened and clarified. Cassidy et al. (Citation2013) discussed a number of areas that need more research, including the need for a better understanding of IWMs in infancy, as she stated there is almost no research evidence in this area. The physiological components of attachment and threat also need further investigation particularly in terms of the biological stress response when attachment is threatened. Further areas of enquiry could also focus on the link between psychopathology and attachment with additional integration of the advances in neuroscience.

As discussed previously, research has examined attachment‐based interventions in the Australian Aboriginal context. The Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS, Citation2016) cautions that when applying the theory to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and families there is a need to look beyond the dyad to multiple attachment relationships and in particular to consider the extended family and kinship networks. The AIFS document was written in the context of out of home care placements however this should also be considered during assessment and intervention. Ryan's (Citation2011) linkage of the Aboriginal concept of kanyininpa, or holding, to attachment and her understanding of a wider view of attachment within Aboriginal culture which included land, extended family, and spirituality begins to explore these ideas. Further exploration is also needed of Yeo's (Citation2003) ideas that aspects of attachment may be interpreted differently in Aboriginal culture and that the historical, cultural and spiritual contexts need to be included when assessing attachment. Attachment theory was developed using cross cultural populations, however continued refinement to include and extend any Aboriginal knowledge would serve to further strengthen its theoretical basis.

Another important consideration is that there are recent movements such as Attachment Parenting International and Dr Sears (Citation2001) who wrote The Attachment Parenting Book. These sources discussed attachment parenting as including home birth, breastfeeding, and co‐sleeping (Divecha, Citation2017). These practices may be beneficial to children and parents; however, the research base linking these practices to the development of a secure attachment is insufficient (Divecha, Citation2017). Attachment therapy, which is also termed coercive restraint therapy, involves physically intrusive techniques with the aim of increasing emotional attachment (Mercer, Citation2005). Mercer (Citation2005) reported that these dangerous coercive restraint techniques have been linked to child deaths and poor growth outcomes. In popular culture such as blogs and self‐help books the terms attachment parenting, attachment therapy, and attachment theory are often used interchangeably. Researchers and clinicians who use attachment theory need to be careful to explain the differences between these concepts as they may be confused in public perception.

Challenges and opportunities for links to psychopathology and diagnostic criteria

Attachment has been shown to predict outcomes in adolescence and adulthood (Sroufe, Coffino, & Carlson, Citation2010). There have been difficulties translating these findings into useable clinical concepts. First, there are a lack of clear links to diagnostic categories. Zeanah and Boris (Citation2000) made a convincing argument for the inclusion of further diagnostic criteria based on the findings from attachment research. DeKlyen and Greenberg (Citation2016) reported that these criteria were not included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013) or the International Classification of Diseases (ICD‐10, World Health Organization, Citation2007). The more extreme forms of attachment disorders such as RAD were kept in the classification manuals despite them being uncommon in clinical populations due to the extreme nature of the caregiving environment required. There is an opportunity for further research looking at symptomology and classification of dysfunctional attachment patterns and whether these could be added to the current diagnostic criteria, overlap with other disorders already listed in the diagnostic criteria, or if a new relationally based diagnostic system is required. Indeed Lyons‐Ruth and Jacobvitz (Citation2016) propose that the development and clinical applications of these criteria should be a priority.

Second, the interventions which have been developed are general in nature, targeting a range of behaviours in parents and children. While the overarching nature of the attachment‐based interventions mirrors the wide ranging implications of attachment on later health and wellbeing they do not address specific psychopathology or populations. Cassidy et al. (Citation2013) encourages further research to focus on clinically significant problems and specific clinical disorders. Since the research indicates stronger links between a disorganised attachment and externalising disorders and between insecure attachment and internalising disorders it may be useful for research to examine whether the interventions could be tailored for these individual populations. From these two groups sub‐populations may be identified which meet specific diagnostic criteria and have a greater response to the intervention. Tailoring interventions can provide parents and caregivers with more information relevant to their specific difficulties and could provide them with a clearer understanding of how parenting behaviour can affect their child's behaviours.

Challenges and opportunities for attachment‐based measures

Observational measures are rich in data but are time and resource intensive to administer. There is a need to narrow down the large number of observational measures and ensure information regarding validity and reliability is easily accessible (Mesman & Rossanneke, Citation2013; Munson & Odom, Citation1996). When implementing an intervention, it is important to have easy‐to‐use assessments which are well validated and easy for participants to complete. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Citation2015) recommended that reliable and valid screening measures should be developed. There is more research needed to assess the BAS‐16 in a variety of populations and to ensure the results of the first study can be replicated. Screening measures need to be able to be used in routine clinical appointments and focus on assessing parental attachment style and sensitivity.

Attachment theory has a large range of psychometrically sound observational assessment instruments available. However, there are no self‐report measures of attachment classification or parental sensitivity. Self‐report measures could be completed by a parent to examine their attachment style, their child's attachment style, or to assess their level of parental sensitivity. There is also scope for a therapist‐report measure to be developed for the therapist to complete to assess the attachment style of a parent and/or child. One of the reasons for the lack of self‐report measures is the idea that trauma can cause segregated systems or dissociative symptoms which could lead to defensive exclusion of information by parents (Bowlby, Citation1980; George & West, Citation2012; Solomon & George, Citation2016). This is an important consideration; however, response bias is a well understood psychological construct and many psychometrics incorporate a range of measures to reduce its impact. Cassidy et al. (Citation2013) discussed the difficulties of widespread implementation of attachment interventions due to their cost including the cost of assessing these interventions. A focus for the future should be the development of self‐report measures particularly to examine parental sensitivity and attachment classification. These measures would need to include questions to measure response bias or socially desirable responding.

Munson and Odom (Citation1996) note that when researchers are assessing parent infant interactions, they are combining rating scales and other systems including behavioural coding systems and parent interviews. The combination of methods can provide more descriptive information. Assessing for consistency between self‐report and observational measures could address some of the weaknesses in current dyadic interaction methodologies (Munson & Odom, Citation1996) and lead to a better understanding of responding bias in self‐report measures. Future research should focus on developing self‐report measures, further validating brief instruments such as the BAS‐16, and aim to narrow down the number of observational measures. This research will help develop an evidence base for attachment‐based interventions. A self‐report measure in particular would add another dimension to the assessment of the constructs of caregiver sensitivity and attachment style while being more economical in terms of resources and time.

Challenges and opportunities for parenting interventions

Attachment interventions are growing in popularity and there is a call from large health bodies for more research and evaluation. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Citation2015) in the United Kingdom encouraged evaluation of extensively used interventions for attachment difficulties. It described these interventions as unevaluated. Here in Australia the National Health and Medical Research Council (Citation2017) in a recent report encouraged research to determine which attachment‐based interventions are most effective in Australian communities. They found that it may be feasible to train the whole workforce involved with pregnancy and young children in attachment informed care. Relationships Australia (Citation2016) conducted a survey looking at where parents would seek help if they were worried about their relationship with their baby and found that only 15% of men and 5% of women did not know where to go for help. However, with 1 in 35 children involved with Child Protective Services in Australia during the 2017–18 period it is clear a large number of parents either do not know where to access appropriate services or there are no appropriate services available to support parents (Australia Insititute of Health and Welfare, Citation2017). There is a need for attachment‐based interventions which are backed by research evidence particularly in the Australian context and to ensure all parents know how to access these services.

Effective parenting and a secure attachment have been recognised as ways to build resilience in children (Berlin et al., Citation2016; Lyons‐Ruth et al., Citation1998). Attachment‐based interventions that aim to increase attachment security and caregiver sensitivity lead to lasting and diverse positive effects for children (Berlin et al., Citation2016). Lieberman and Van Horn (Citation2008) argued that attachment‐based interventions should specifically target changing the caregiver's IWMs. This will change the caregiver's behaviour which will flow through to behavioural changes in their child. Parental emotions and cognitions underlie parental behaviour and are more easily measured. Cassidy et al. (Citation2013) encouraged future researchers to make cognitions and emotions in particular IWMs the focus of their interventions. They described these as more “amenable targets” in that they are at the start of a chain of process. Therefore, intervention programs need to focus on the attachment relationship between children and caregivers with a particular emphasis on caregivers' IWMs.

In a recent meta‐analysis Wright and Edginton (Citation2016) found positive overall effective size in the 21 studies of interventions which promoted secure attachment. Because there were a limited number of studies, they encouraged further research. They point to small sample sizes and the lack of studies outside of the United States as important considerations. The California Evidence‐Based Clearing House for Child Welfare reported under its attachment interventions section promising research evidence for child–parent relationship therapy (The California Evidence‐Based Clearing House for Child Welfare, Citation2018). They also described attachment and bio‐behavioural catch‐up as being well‐supported by research evidence, CPP as being supported by research evidence, and circle of security home visiting as having promising research evidence. Attachment‐based interventions are not included in the American Psychological Association website for evidence‐based practice (American Psychological Association, Citation2018) or the Australian Psychological Society review of evidence‐based psychological interventions (Australian Psychological Society, Citation2018). Berlin et al. (Citation2016) reported that the evidence is impressive that attachment‐based interventions are effective. They called for further research particularly focusing on fidelity, family culture and belief systems, and community collaboration. Attachment‐based interventions are widely used, and large health systems acknowledge this, yet they are lacking widespread acceptance from the psychology profession.

Attachment‐based parenting interventions need to be accessible to the general public, short term, cost effective, and focused on IWMs. Bakermans‐Kranenburg et al. (Citation2003) found in their meta‐analysis that “less is more”. Specifically, short‐term, economical, and behaviourally focused programs achieved better outcomes than long‐term programs. Further Van Ijzendoorn, Bakermans‐Kranenburg, and Juffer (Citation2005) proposed that by helping the parent to be more sensitive leads to the child becoming more responsive and that these two reactions continue to scaffold each other. Bakermans‐Kranenburg et al. (Citation2003) and Van Ijzendoorn et al. (Citation2005) further proposed that highly intensive interventions do not work and may even have a negative effect on attachment. Cassidy et al. (Citation2013, p. 1415) discussed the urgent need for “evaluations of comprehensive theory and research‐based intervention protocols that can be widely implemented among families whose infants and children are at elevated risk for developing or maintaining insecure attachments”. Cassidy et al. (Citation2017) discuss in a recent article that there are links between attachment insecurity and disorganisation and psychopathology, however, there have been implementation challenges in the dissemination of attachment‐based interventions. This review discussed attachment‐based interventions as being “very expensive” to implement and that services cannot afford to start the programs. There are “considerable resources” needed to implement these programs including video‐taping and the provision of individualised parental feedback (Cassidy et al., Citation2013). Interventions that can be widely and cost‐effectively implemented are needed.

CONCLUSION

There are many opportunities for researchers interested in attachment theory to develop the theory, assessments, links to diagnosis, and interventions. As attachment‐based interventions are becoming more widely used in Australia it is particularly important to further examine their effectiveness here. The theoretical gaps in the research which have been identified need further investigation. Researchers and clinicians who use attachment theory need to ensure parents and families understand this difference between this theory and other practices which use the word attachment. It is particularly important that the differences are emphasised between research‐based attachment theory and other non‐validated practices. The development of user‐friendly self‐report measures of attachment style and parental sensitivity should be a focus for researchers. This would ensure interventions can be assessed for effectiveness in an economical manner. Intervention programs implemented in clinical practice need to be tested for effectiveness. Attachment researchers would do well to make clear links to current diagnostic criteria. Alternatively, if the current diagnostic criteria are found to be lacking, a consensus on an alternative diagnostic framework is needed. Finally, attachment‐based intervention programs are needed which are cost effective, short term, and target IWMs. Shorter more targeted interventions are less resource and time intensive. Attachment theory has much potential to help build resilience in future generations. This potential is beginning to be realised through innovative interventions. However, there is a need for the assessment and diagnostic criteria to change along with the growth of this theory.

REFERENCES

- Ainsworth, M. D. (1967). Infancy in Uganda: Infant care and the growth of love. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press.

- Ainsworth, M. D. (1969). Maternal sensitivity scales: The Baltimore longitudinal project (1969). Retrieved from http://www.psychology.sunysb.edu/attachment/measures/content/maternal%20sensitivity%20scales.pdf

- Ainsworth, M. D., Bell, S. M., & Stayton, D. (1974). Infant‐mother attachment and social development. In M. P. Richards (Ed.), The introduction of the child into a social world (pp. 99–135). London, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Ainsworth, M. D., Blehar, M. C., & Waters, E. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study strange situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of the mental disorders (Fifth Edition – Text Revision, DSM‐5_TR). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- American Psychological Association. (2018). Psychological treatments. Retrieved from https://www.div12.org/treatments/

- Australia Insititute of Health and Welfare. (2017–2018). Child protection Australia 2017–18. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/child‐protection/child‐protection‐australia‐2017‐18/contents/table‐of‐contents

- Australian Institute of Family Studies. (2016). Children's attachment needs in the context of out‐of‐home care. CFCA Practitioner Resource. Retrieved from https://aifs.gov.au/cfca/publications/childrens-attachment-needs-context-out-home-care

- Australian Psychological Society. (2018). Evidence‐based psychological interventions in the treatment of mental disorders: A review of the literature.

- Bakermans‐kranenburg, M. J., Van, I. M. H., Pijlman, F. T., Mesman, J., & Juffer, F. (2008). Experimental evidence for differential susceptibility: Dopamine D4 receptor polymorphism (DRD4 VNTR) moderates intervention effects on toddlers' externalizing behavior in a randomized controlled trial. Developmental Psychology, 44(1), 293–300. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.293

- Bakermans‐kranenburg, M. J., Van ijzendoorn, M. H., & Juffer, F. (2003). Less is more: Meta‐analyses of sensitivity and attachment interventions in early childhood. Psychological Bulletin, 129(2), 195–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.195

- Bakermans‐kranenburg, M. J., Van ijzendoorn, M. H., Mesman, J., Alink, L. R., & Juffer, F. (2008). Effects of an attachment‐based intervention on daily cortisol moderated by dopamine receptor D4: A randomized control trial on 1‐ to 3‐year‐olds screened for externalizing behavior. Development and Psychopathology, 20(3), 805–820. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579408000382

- Barlow, J., Schrader‐mcmillan, A., Axford, N., Wrigley, Z., Sonthalia, S., Wilkinson, T., … Coad, J. (2016). Review: Attachment and attachment‐related outcomes in preschool children – a review of recent evidence. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 21(1), 11–20.

- Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New York, NY: International University Press.

- Berlin, L. J., Zeanah, C. H., & Lieberman, A. F. (2016). Prevention and intervention programs to support early attachment security: A move to the level of community. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications (pp. 739–758). New York, NY: The Guildford Press.

- Bick, J., & Dozier, M. (2013). The effectiveness of an attachment‐based intervention in promoting Foster mothers' sensitivity toward Foster infants. Infant Mental Health Journal, 34(2), 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21373

- Bick, J., Dozier, M., & Moore, S. (2012). Predictors of treatment use among foster mothers in an attachment‐based intervention program. Attachment & Human Development, 14(5), 439–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2012.706391

- Biringen, Z., Derscheid, D., Vlliegen, N., Closson, L., & Easterbrooks, A. (2014). Emotional availability (EA): Theoretical background, empirical research using the EA scales and clinical applications. Developmental Review, 34, 114–167.

- Biringen, Z., Robinson, J., & Emde, R. N. (1993). Manual for scoring of the emotional availability scales middle childhood version. Boulder, CO: University of Colorado.

- Bowlby, J. (1940). The influence of early environment in the development of neurosis and neurotic character. International Journal of Psycho‐Analysis, 21, 154–178.

- Bowlby, J. (1951). Maternal care and mental health. World Health Organization Monograph. (Serial No. 2). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation.

- Bowlby, J. (1960). Grief and mourning in infancy and early childhood. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, VX, 3–39.

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss. In Attachment (Vol. 1). New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and loss. In Loss, sadness and depression (Vol. 3). New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Bowlby, J., Ainsworth, M., Boston, M., & Rosenbluth, D. (1956). The effects of mother‐child separation: A follow‐up study. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 29, 211–247.

- Bretherton, I. (1992). The origins of attachment theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. Developmental Psychology, 28(5), 759–775. http://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0012-1649.28.5.759

- Cadman, T., Belsky, J., & Pasco fearon, R. M. (2018). The brief attachment scale (BAS‐16): A short measure of infant attachment. Child, Care, Health and Development, 44, 766–775.

- Carlson, E. A. (1998). A retrospective longitudinal study of disorganised/disoriented attachment. Child Development, 69, 1107–1128.

- Cassidy, J. (2016). The nature of the child's ties. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications (pp. 3–24). New York, NY: The Guildford Press.

- Cassidy, J., Brett, B. E., Gross, J., Stern, J. A., Martin, D. R., Mohr, J. J., & Woodhouse, S. S. (2017). Circle of security–parenting: A randomized controlled trial in head start. Development and Psychopathology, 29(2017), 651–673.

- Cassidy, J., Jones, J. D., & Shaver, P. R. (2013). Contributions of attachment theory and research: A framework for future research, translation, and policy. Development and Psychopathology, 25(4 Pt 2), 1415–1434. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579413000692

- Cassidy, J., Woodhouse, S. S., Sherman, L. J., Stupica, B., & Lejuez, C. W. (2011). Enhancing infant attachment security: An examination of treatment efficacy and differential susceptibility. Development and Psychopathology, 23(1), 131–148. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579410000696

- Cassidy, J., Ziv, Y., Stupica, B., Sherman, L. J., Bulter, H., Karfgin, A., … Powell, B. (2010). Enhancing attachment security in the infants of women in a jail‐diversion program. Attachment & Human Development, 12(4), 333–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730903416955

- Circle of Security. (2018). Directory. Retrieved from https://www.circleofsecurityinternational.com/directory

- Clark, R. (1985). Early parent‐child relationship assessment. Madison, WI: Department of Psychiatry.

- Coan, J. A. (2016). Toward a neuroscience of attachment. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications (pp. 242–263). New York, NY: The Guildford Press.

- Colonnesi, C., Draijer, E. M., Stams, G. J., Van der bruggen, C., Bogels, S., & Noom, M. J. (2011). The relation between insecure attachment and child anxiety: A meta‐analytic review. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 40, 630–645.

- Crittenden, P. M. (2001). CARE‐index manual. Miami, FL: Family Relations Institute.

- Deklyen, M., & Greenberg, M. T. (2016). Attachment and psychopathology in childhood. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications (pp. 639–666). New York, NY: The Guildford Press.

- Divecha, D. (2017). What is a secure attachment? And why doesn't “attachment parenting” get you there? Retrieved from http://www.developmentalscience.com/blog/2017/3/31/what-is-a-secure-attachmentand-why-doesnt-attachment-parenting-get-you-there

- Dozier, M., Lindheim, O., & Ackerman, J. P. (2005). Attachment and biobehavioural catch‐up. In L. J. Berlin, Y. Ziv, L. Amaya‐jackson, & M. T. Greenberg (Eds.), Enhancing early attachments: Theory, research, intervention, and policy (pp. 178–194). New York, NY: Guildford Press.

- Ehrlich, K. B., Miller, G. E., Jones, J. D., & Cassidy, J. (2016). Attachment and psychoneuroimmunology. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications (pp. 180–201). New York, NY: The Guildford Press.

- Englund, M., Kuo, S. I., Puig, J., & Collins, W. A. (2011). Early roots of adult competence: The significance of close relationships from infancy to early adulthood. International Journal of Behavioural Development, 35, 490–496.

- Erickson, M. F., Sroufe, L. A., & Egeland, B. (1985). The relationship between quality of attachment and behavior problems in preschool in a high‐risk sample. In I. Bretherton & E. Waters (Eds.), Growing points of attachment: Theory and research. Monographs of the Society for Research in child development (Vol. 50, pp. 147–166). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Fearon, P., & Belsky, J. (2011). Infant‐mother attachment and the growth of externalizing problems across primary‐school years. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52, 782–791.

- Feldman, R. (1998). Coding interactive behaviour (CIB) manual. Bar‐Ilan University. Unpublished manuscript.

- Futh, A., O'conner, T. G., Matais, C., Green, J., & Scott, S. (2008). Attachment narratives and behavioural and emotional symptoms in an ethnically diverse, at‐risk sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47, 709–718.

- Gaudiano, B. A. (2008). Cognitive‐behaviour therapies: Achievements and challenges. Evidence Based Mental Health, 11(2), 5–7.

- George, C., & West, M. L. (2012). The adult attachment projective picture system: Attachment theory and assessment in adults. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Ghosh ippen, C., Harris, W. W., Van horn, P., & Lieberman, A. F. (2011). Traumatic and stressful events in early childhood: Can treatment help those at highest risk? Child Abuse & Neglect, 35(7), 504–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.03.009

- Hane, A. A., & Fox, N. A. (2016). Studying the biology of human attachment. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications (pp. 223–241). New York, NY: The Guildford Press.

- Health, N., & Medical Research Council. (2017). NHMRC report on the evidence: Promoting social and emotional development and wellbeing of infants in pregnancy and the first year of life. Canberra, ACT: National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Government.

- Hoffman, K. T., Marvin, R. S., Cooper, G., & Powell, B. (2006). Changing toddlers' and preschoolers' attachment classifications: The circle of security intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(6), 1017–1026. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1017

- Hofmann, S. G., Asnaani, A., Imke, V. J., Sawyer, A. T., & Fang, A. (2012). The efficacy of cognitive behaviour therapy: A review of meta‐analyses. Cognitive Therapy Research, 36(5), 427–440.

- Huber, A., Mcmahon, C., & Sweller, N. (2015). Efficacy of the 20‐week circle of security intervention: Changes in caregiver reflective functioning representations, and child attachment in an Australian clinical sample. Infant Mental Health Journal, 36(6), 556–574.

- Huber, A., Mcmahon, C., & Sweller, N. (2016). Improved parental emotional functioning after circle of security 20‐week parent–child relationship intervention. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 2526–2540.

- Juffer, F., Bakermans‐kranenburg, M. J., & Van ijzendoorn, M. H. (2008). Promoting positive parenting: An attachment‐based intervention. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Lee, L., Griffiths, C., Glossop, P., & Eapen, V. (2010). The boomerangs parenting program for aboriginal parents and their young children. Australasian Psychiatry, 18(6), 527–533.

- Lieberman, A. F., & Van horn, P. (2005). Don't hit my mommy: A manual for child‐parent psychotherapy with young witnesses of family violence. Washington, DC: Zero to Three Press.

- Lieberman, A. F., & Van horn, P. (2008). Psychotherapy with infants and young children: Repairing the effects of stress and trauma on early attachment. New York, NY: Guildford Press.

- Lyons‐ruth, K., Bruschweiler‐stern, N., Harrison, A. M., Morgan, A. C., Nahum, J. P., Sander, L., … Tronick, E. Z. (1998). Implicit relational knowing: Its role in development and psychoanalytic treatment. Infant Mental Health Journal, 19(3), 282–289. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0355(199823)19:3<282::AID-IMHJ3>3.0.CO;2-O

- Lyons‐ruth, K., Bureau, J., Holmes, B., Easterbrooks, A., & Brooks, N. H. (2013). Borderline symptoms and suicidality/self injury in late adolescence: Prospectively observed relationship correlates in infancy and childhood. Psychiatry Research, 206, 273–281.

- Lyons‐ruth, K., & Jacobvitz, D. (2016). Attachment disorganisation from infancy to adulthood: Neurobiological correlates, parenting contexts, and pathways to disorder. In J. Cassidy & P. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Main, M., & Solomon, J. (1990). Procedures for identifying infants and disorganised/disoriented during the Ainsworth strange situation. In M. T. Greenberg, C. A. Cummings, & E. M. Cummings (Eds.), Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research and intervention (pp. 134–146). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Masters, J. C., & Wellman, H. M. (1974). The study of human infant attachment: A procedural critique. Psychological Buletin, 81, 218–237.

- Mcmahon, C., Huber, A., Kohlhoff, J., & Camberis, A. L. (2017). Does training in the circle of security framework increase relational understanding in infant/child and family workers. Infant Mental Health Journal, 38(5), 658–668.

- Mercer, J. (2005). Coercive restraint therapies: A dangerous alternative mental health intervention. Medscape General Medicine, 7(3), 6.

- Mesman, J., & Rossanneke, G. E. (2013). Mary Ainsworth's legacy: A systematic review of observational instruments measuring parental sensitivity. Attachment & Human Development, 15(5–6), 485–506.

- Mesman, J., Van ijzendoorn, M. H., & Sagi‐schwartz, A. (2016). Cross‐cultural patterns of attachment: Universal and contextual dimensions. New York, NY: The Guildford Press.

- Moss, E., Smolla, N., Cyr, C., Dubois‐comtois, K., Mazzarello, T., & Berthiaume, C. (2006). Attachment and behaviour problems in middle childhood as reported by adult and child informants. Development and Psychopathology, 18, 425–444.

- Munson, L. J., & Odom, S. L. (1996). Review of rating scales that measure parent‐infant interaction. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 16(1), 1–25.

- Murray, L., Fiori‐cowley, A., Hooper, R., & Cooper, P. (1996). The impact of postnatal depression and associated adversity on early mother‐infant interactions and later infant outcome. Child Development, 67(5), 2512–2526.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2015). Children's attachment: Attachment in children and young people who are adopted from care, in care or at high risk of going into care. United Kingdom: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

- Nowakowski‐sims, E., & Rowe, A. (2016). The relationship between childhood adversity, attachment, and internalising behaivours in a diversion program for child‐to‐mother violence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 72, 266–275.

- Owen, M. T. (1992). The NICHD study of early child care mother‐infant interaction scales. Dallas, TX: Timberlawn Psychiatric Research Foundation Unpublished manuscript.

- Pasalich, D. S., Dadds, M. R., Hawes, D. J., & Brennan, J. (2012). Attachment and callous‐emotional traits in children with early‐onset conduct problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53, 838–845.

- Pederson, D. R., & Moran, G. (1995). Appendix B: Maternal behavior Q‐set. Monographs for the Society for Research in Child Development, 60(2–3), 247–254.

- Pianta, R. C., Egeland, B., & Sroufe, L. A. (1990). Maternal stress in childrens' development: Predictions of school outcomes and identification of protective factors. In J. E. Rolf, A. Masten, D. Cicchetti, K. Neuchterlen, & S. Weintraub (Eds.), Risk and protective factors in the development of psychopathology (pp. 215–235). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Powell, B., Cooper, G., Hoffman, K., & Marvin, B. (2014). The circle of security intervention: Enhancing attachment in early parent‐child relationships. New York, NY: NY: The Guildford Press.

- Relationships Australia. (2016). July 2016: Child attachment. Retrieved from https://www.relationships.org.au/what-we-do/research/online-survey/july-2016-child-attachment

- Risholm mothander, P., Furmark, C., & Neander, K. (2017). Adding “circle of security – Parenting” to treatment as usual in three Swedish infant mental health clinics. Effects on parents' internal representations and quality of parent‐infant interaction. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 59(3), 262–272.

- Rose, J., & O'reilly, B. (2017). A systematic review of attachment‐based psychotherapeutic interventions for adopted children. Early Child Development and Care, 187(12), 1844–1862.

- Ryan, F. (2011). Kanyininpa (holding): A way of nurturing children in aboriginal Australia. Australian Social Work, 64(2), 183–197.

- Sears, W. (2001). The attachment parenting book. New York, NY: Little, Brown & Company.

- Shaw, D. S., Keenan, K., Vondra, J. I., Delliquadri, E., & Giovannelli, J. (1997). Antecedents of preschool children's internatlising problems: A longitudinal study of low‐income families. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 1760–1767.

- Simpson, J. A., & Belsky, J. (2016). Attachment theory with a modern evolutionary framework. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications (pp. 91–116). New York, NY: The Guildford Press.

- Slade, A. (2016). Attachment and adult psychotherapy: Theory, research, and practice. In J. Cassidy & P. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. New York, ny: The Guilford Press.

- Solomon, J., & George, C. (2016). The measurement of attachment security and related constructs in infancy and early childhood. In J. Cassidy & P. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications (pp. 366–396). New York, NY: The Guildford Press.

- Sroufe, A. L., Egeland, B., & Kreutzer, T. (1990). The fate of early experience following developmental change: Longitudinal approaches to individual adaptation in childhood. Child Development, 61(5), 1363–1373.

- Sroufe, L. A. (2005). Attachment and development: A prospective, longitudinal study from birth to adulthood. Attachment & Human Development, 7(4), 349–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730500365928

- Sroufe, L. A. (2016). The place of attachment in development. In J. Cassidy & P. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications (pp. 997–1011). New York, NY: The Guildford Press.

- Sroufe, L. A., Coffino, B., & Carlson, E. A. (2010). Conceptualising the role of early experience: Lessons from the Minnesota longitudinal study. Developmental Review, 30, 36–51.

- Sroufe, L. A., Egeland, B., Carlson, E. A., & Collins, W. A. (2005). The development of the person: The Minnesota study of risk and adaptation form birth to adulthood. New York, NY: Guildford Press.

- Stovall‐mcclough, K. C., & Dozier, M. (2016). Attachment states of mind and psychopathology in adulthood. In J. Cassidy & P. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- The California Evidence‐Based Clearing House for Child Welfare. (2018). Topic: Attachment inteventions (Child & Adolescent). Retrieved from http://www.cebc4cw.org/topic/attachment‐interventions‐child‐adolescent/

- Thompson, R. A., & Raikes, H. A. (2003). Toward the next quarter‐century: Conceptual and methodological challenges for attachment theory. Development and Psychopathology, 15, 691–718.

- Van ijzendoorn, M. H., Bakermans‐kranenburg, M. J., & Juffer, F. (2005). Why less is more: From the dodo bird verdict to evidence‐based interventions on sensitivity and early attachments. In L. Berlin, Y. Ziv, L. Amaya‐jackson, & M. Greenberg (Eds.), Enhancing early attachments: Theory, research, intervention, and policy (pp. 297–312). New York, NY: Guilford.

- Velderman, M. K., Bakermans‐kranenburg, M. J., Juffer, F., & Van, I. M. H. (2006). Effects of attachment‐based interventions on maternal sensitivity and infant attachment: Differential susceptibility of highly reactive infants. Journal of Family Psychology, 20(2), 266–274. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.266

- Warren, S. L., Huston, L., Egeland, B., & Sroufe, L. A. (1997). Child and adolescent anxiety disorders and early attachment. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 637–644.

- Waters, H. S., & Waters, E. (2006). The attachment working models concept: Among other things, we build script‐like representations of secure base experiences. Attachment & Human Development, 8(3), 185–197.

- Woodhouse, S. S. (2018). Attachment‐based interventions for families with young children. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74, 1296–1299.

- World Health Organization. (2007). Preventing child maltreatment in Europe: A public health approach. Rome, Italy: WHO Press.

- World Health Organization. (2018). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11th Revision). Retrieved from https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en

- Wright, B., & Edginton, E. (2016). Evidence‐based parenting interventions to promote secure attachment: Findings from a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Global Pediatric Health, 3, 1–14.

- Yeo, S. S. (2003). Bonding and attachment of Australian aboriginal children. Child Abuse Review, 12, 292–304. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.817

- Zeanah, C. H. (1996). Beyond insecurity: A reconceptualization of attachment disorders of infancy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64(1), 42–52. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.64.1.42

- Zeanah, C. H., Benoit, D., & Barton, M. (1996). Working model of the child interview coding manual. Unpublished manuscript.

- Zeanah, C. H., & Boris, N. W. (2000). Disturbances and disorders of attachment in early childhood. In C. H. Zeanah (Ed.), Handbook of infant mental health (2nd ed., pp. 353–368). New York, NY: The Guildford Press.

- Zeanah, C. H., & Gleason, M. M. (2010). Reactive attachment disorder: A review for DSM‐V. Report presented to the American Psychiatric Association, Retrieved from http://www.dsm5.org/