Abstract

Objective

Climate change and related issues associated with the interaction of humans with the environment are of great importance in today's context. More and more research is focusing on understanding what can be done to prevent and reverse the effects of environmental problems through individual behaviours. Within psychology, there is a lack of synthesis of what drives pro‐environmental behaviours in various paradigms and how they can be changed. The current study focuses on the application of protection motivation theory to predicting and changing pro‐environmental behaviours using a systematic mapping approach.

Methods

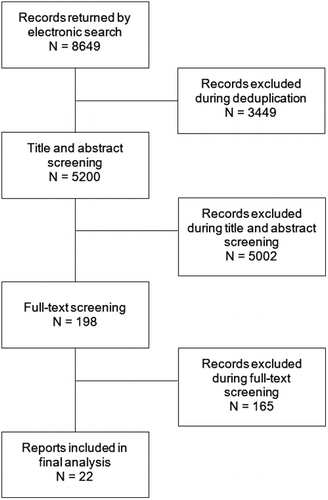

A systematic screening of 132 databases was performed, resulting in the identification of 22 relevant studies with the total N = 12,827.

Results

Investigation of the included research revealed a number of gaps in knowledge including: lack of experimental evidence with successful manipulations of protection motivation theory constructs; non‐inclusion of all the aspects of the theory into studies; the absence of examination of the intention–behaviour relationship; the lack of consistency in operationalisation of protection motivation theory constructs; a focus on predominantly western high income societies, and the lack of uniformity in the definition of pro‐environmental behaviours.

Conclusion

Future research should consider employing experimental designs with proper manipulation checks and longitudinal focus, as well as consistent definitions and operationalisations of relevant concepts, and exploring these constructs across different countries.

Funding information Deakin University's Health ReseArch Capacity Building Grant ScHeme

What is already known about this topic

Protection motivation theory (PMT) is a model of behaviour that applies threat‐based perceptions and beliefs to typically understand the adoption of health‐protective behaviours.

Due to the threat of environmental hazards such as climate change, some recent research has attempted to employ PMT to understand the adoption of some forms of pro‐environmental behaviours.

Currently there is a lack of synthesis of what PMT constructs have been found to be associated with and contribute to pro‐environmental behaviour.

What this topic adds

The current systematic mapping review identifies and synthesises 22 studies with 12,827 individuals that applied the protection motivation theory (PMT) to predict and change pro‐environmental behaviour.

Broad findings provide support for the hypothesised association between all the PMT constructs and a range of pro‐environmental behaviours.

However, findings also suggest several gaps in the literature, including a lack of well‐powered experimental designs, studies that include all PMT constructs in the one study, a lack of non‐WEIRD samples, an inconsistent usage of pro‐environmental behaviour definitions, and little examination of the intention–behaviour relationship for pro‐environmental behaviour.

INTRODUCTION

Human behaviour plays a significant role in explaining the current state of the natural environment (IPCC, Citation2018; Laffoley & Baxter, Citation2016). For instance, global environmental threats such as climate change, biodiversity loss, and deforestation have all been, at least partly, attributed to unsustainable human behaviour (IPCC, Citation2018; Laffoley & Baxter, Citation2016). While institutional and policy changes can help to reduce these environmental threats, they are incomplete without a simultaneous focus on understanding and encouraging individual‐level behaviours that reduce one's unsustainable impact on the natural environment (Clayton & Brook, Citation2005; Swim, Clayton, & Howard, Citation2011). Therefore, encouraging individuals to engage in a variety of pro‐environmental behaviours, such as reducing their energy use, increasing use of public transport, and changing farming practices, is an important component in maximising positive environmental outcomes and reducing the severity of global environmental threats (Gardner & Stern, Citation2008; Koger & Winter, Citation2011; Rettie, Burchell, & Riley, Citation2012; Steel, Citation1996; Vlek & Steg, Citation2007).

Researchers have long attempted to understand the factors that influence the persuasiveness of social marketing and public information communications that advocate changes in pro‐environmental behaviours (Cismaru, Cismaru, Ono, & Nelson, Citation2011; Hall & Taplin, Citation2007; Kidd, Bekessy, & Garrard, Citation2019; Markelj, Citation2009; Nelson, Cismaru, Cismaru, & Ono, Citation2011; Scharks, Citation2016). Studies that have sought to review the content of press coverage and government and NGO social marketing campaigns have observed that such persuasive messages commonly include a fear appeal component that emphasises threat to individuals and/or society (Cismaru et al., Citation2011; Kidd et al., Citation2019; Nelson et al., Citation2011; Scharks, Citation2016). More recently, messages have also begun to include a stronger emphasis on efficacy messages that seek to persuade people that they are capable of engaging in behaviours that would be effective in mitigating threats (Scharks, Citation2016).

The growing emphasis on efficacy messages has occurred as conservation scientists have made explicit calls for decreasing emphasis on ‘crisis’ and adoption of a more optimistic approach to behaviour change within conservation science (Garnett & Lindenmayer, Citation2011) and as environmental psychologists and others have argued that fear appeals are most effective when combined with efficacy information (Pike, Doppelt, & Herr, Citation2010). However, as recently acknowledged by Kidd et al. (Citation2019) this shift in emphasis has often not been based on domain specific evidence. Instead, researchers and policy makers have often relied on studies of fear appeals from public health and medicine when making recommendations about how campaigns should be designed (Cismaru et al., Citation2011; Nelson et al., Citation2011; Scharks, Citation2016). Calls from more focused empirical tests of theories of behaviour change within the domain of pro‐environmental behaviour have been made by a number of researchers over the past decade (Kidd et al., Citation2019; Nelson et al., Citation2011).

In parallel, a number of researchers have sought to identify theories that are of particular relevance to understanding pro‐environmental behaviours and to designing and evaluating persuasive messages that seek to increase engagement in such behaviours (Nisbet & Gick, Citation2008; Pronello & Gaborieau, Citation2018). Such reviews have tended to take the form of a narrative discussion of theories that may be conceptually relevant to this domain rather than a systematic review of the body of evidence using any given theory. While such an approach plays an important role in introducing novel theories and/or identifying widely used theories from other areas (most often from health psychology and behavioural medicine) that are likely to be useful in understanding pro‐environmental behaviours, they have not sought to systematically identify and summarise the empirical evidence from studies that have sought to apply and test individual theories within this domain. The lack of such a comprehensive empirical review makes it difficult for researchers, policy‐makers, and practitioners to easily access an up‐to‐date summary of the empirical basis for applying a theory within this domain. This challenge is compounded by the diversity of the pro‐environmental literature, while some studies have been conducted in environmental psychology others are published within more distant disciplines such as economics, tourism, agriculture, sustainability, water management, ecology, and conservation science. Unfortunately, such work is often not indexed within a single bibliographic database and so is difficult for individuals to access and synthesise independently.

The aim of this study is to systematically identify all studies that have sought to apply a single theory of behaviour and behaviour change, protection motivation theory (PMT), to predict and change pro‐environmental behaviours. PMT was originally developed to understand the adoption of health‐protective behaviour (Prentice‐Dunn & Rogers, Citation2001), and there is extensive evidence supporting the associations among the constructs outlined in the theory within a health context (Floyd, Prentice‐Dunn, & Rogers, Citation2001; Milne, Sheeran, & Orbell, Citation2000). PMT has since been applied to behaviours outside of a health context such as parenting (Campis, Prentice‐Dunn, & Lyman, Citation1989), tourism (Horng, Hu, Teng, & Lin, Citation2014), information security (Lebek, Uffen, Neumann, Hohler, & Breitner, Citation2014), and disaster preparedness (Bubeck, Wouter Botzen, Laudan, Aerts, & Thieken, Citation2017). Researchers have repeatedly argued that PMT is an effective model understanding and promoting engagement in pro‐environmental behaviours (Cismaru et al., Citation2011; Nelson et al., Citation2011; Pronello & Gaborieau, Citation2018).

Protection motivation theory

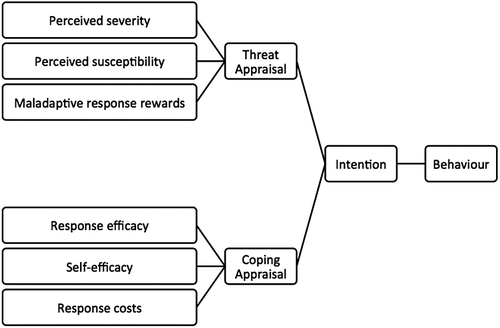

PMT postulates that there are two processes that determine engagement in protective behaviours: coping appraisal and threat appraisal (see Figure 1; Maddux & Rogers, Citation1983; Prentice‐Dunn & Rogers, Citation2001; Rogers, Prentice‐Dunn, & Gochman, Citation1997). According to the theory, individuals intend to engage in protective behaviour (i.e., adaptive response) when facing a threatening event when they believe that lack of action would pose a threat to themselves (high threat appraisal) and that performing the protective behaviour would ameliorate that threat (high coping appraisal; Prentice‐Dunn & Rogers, Citation2001; Rogers et al., Citation1997).

Within threat appraisal, maladaptive response rewards, threat severity and threat susceptibility are suggested as antecedents of intention to engage in protective behaviour (Prentice‐Dunn & Rogers, Citation2001; Rogers et al., Citation1997). Maladaptive response rewards refer to the intrinsic and extrinsic benefits of neglecting a given protective behaviour, thus this construct has a negative relationship with intention to act protectively (Prentice‐Dunn & Rogers, Citation2001; Rogers et al., Citation1997). Threat severity is a belief about the seriousness of the consequences of the threat; and threat susceptibility is the perception of one's personal vulnerability to suffering those consequences. According to the theory and to past research that has applied it, higher perceived threat severity and susceptibility correspond to higher intention to engage in the protective behaviour (Prentice‐Dunn & Rogers, Citation2001; Rogers et al., Citation1997).

Within coping appraisal, response efficacy, self‐efficacy, and response costs are proposed as antecedents of intention to adopt a given protective behaviour. Response efficacy relates to the belief that the protective behaviour will effectively avert the threat (Prentice‐Dunn & Rogers, Citation2001; Rogers et al., Citation1997); and self‐efficacy is conceptualised as the individual's perception of their ability to perform the protective behaviour (Prentice‐Dunn & Rogers, Citation2001; Rogers et al., Citation1997). Higher response efficacy and self‐efficacy predict higher intention to engage in the protective behaviour. On the other hand, response costs refer to the perception of the costs associated with carrying out the protective behaviour; therefore, higher response costs are associated with lower intention to uptake the adaptive response (Prentice‐Dunn & Rogers, Citation2001; Rogers et al., Citation1997).

Overall, a person is most likely to intend to engage in a behaviour to protect themselves from a threat when severity, susceptibility, self‐efficacy, and response efficacy are high and response costs and maladaptive response rewards are low. For example, a person evaluating whether or not to purchase an electric vehicle in response to the threat of climate change would evaluate the seriousness of risks posed by climate change (severity), the extent to which they are personally vulnerable to the risks posed by climate change (susceptibility), and whether there are any perverse incentives that would personally benefit them if climate change was to occur or if they did not engage in behaviours to reduce the risk of climate change occurring (maladaptive response rewards). The person would also consider whether they personally feel capable of switching to an electric vehicle (self‐efficacy) whether they believe that using an electric vehicle would reduce the threat of climate change (response efficacy), and the perceived costs or barriers to electric vehicle adoption (response costs). Similarly, a farmer might adopt sustainable farming practices in order to reduce the threat posed by drought if they believe that the threat of drought is high (severity), they are highly vulnerable to drought on their property (susceptibility), there are few or no perverse incentives to drought occurring (maladaptive response rewards) and where they believe that the drought mitigation behaviours are not overly costly (response costs), they are capable of enacting them (self‐efficacy) and they would be effective in reducing the risk of negative impacts of drought occurring (response efficacy).

Aim

The overall aim of this review is to identify, map, and describe existing empirical evidence regarding the use of protection motivation theory to predict and change pro‐environmental behaviour using a systematic mapping approach. A systematic evidence map provides an overview of existing research, and categorises the key characteristics of included studies. This method of research synthesis uses a systematic process to identify relevant evidence. It is intended that these maps facilitate access to research and highlights important gaps in the research evidence (Snilstveit, Vojtkova, Bhavsar, Stevenson, & Gaarder, Citation2016).

The specific major objectives of this systematic evidence gap map are to:

Identify studies that have used PMT to predict and change of pro‐environmental behaviour.

Identify gaps in the research where new studies could add value.

METHOD

Search strategy

Systematic searches were conducted to identify studies that used PMT in the following databases providers EBCOHost (25 databases), ProQuest (101 databases), and Web of Science (6 databases). The full list of databases is shown in Appendix 1. The search included databases in health, education, economics, humanities, and physical sciences. In addition, forward citation searching of four key papers was conducted through Web of Science (see Table ).

Table 1. Key references for forward citation searching

Screening

Screening of titles and abstracts was conducted to identify records that were relevant to the review. Title and abstract screening was conducted by three reviewers (EK, MN, and ML). Records that remained after title and abstract screening underwent full‐text screening (EN, EK, ML, AK, and BM). At both stages all records were independently reviewed by at least two reviewers, where the reviewers did not initially agree conflicts were resolved via consensus and after consultation with a third reviewer.

Records were excluded if they: did not include human participants; mentioned a theory other than PMT in the title and did not mention PMT or fear appeals within the title or abstract; did not describe a study that sought to predict or change behaviour or beliefs; included an experimental manipulation that targeted non‐PMT constructs and did not include a condition where PMT constructs were manipulated; were published in a language other than English; or were a commentary, press release, systematic review, meta‐analysis or report of qualitative research.

Records were included if they described a study where the behaviour of interest was categorised by the expert reviewers as a ‘pro‐environmental behaviour’ and PMT was used to predict or change intention and/or behaviour.

Definitions of pro‐environmental behaviour are often broad and vary within the literature (as noted by Lange & Dewitte, Citation2019). However, for the purposes of the study, pro‐environmental behaviour was defined as those behaviours that proactively attempted to conserve and/or protect the natural environment (Stern, Citation2000; Vlek & Steg, Citation2007). More specifically, these would be behaviours that individuals engaged in that either attempted to reduce harm to the natural environment as much as possible (conserve) or benefit the natural environment (protect).

Following this definition, specific actions that were considered pro‐environmental varied from small, private‐sphere individual actions such as recycling to large, public sphere collective actions such as environmental activism (Bamberg & Möser, Citation2007; Gatersleben, Citation2012). In particular, behaviours that were considered to fall under our broad definition included: activism (active involvement in public displays of environmental concern such as protesting); citizenship behaviours (individual support and acceptance of pro‐environmental government policies); conservation lifestyle actions (individual lifestyle actions that have a positive impact on the natural environment such as green consumerism and reduction in energy use); willingness to make financial sacrifices on behalf of the environment; and organisational environmentalism (behaviours or policies that organisations employ to reduce their environmental impact; Stern, Citation2000). Behaviours that were a direct response or strategy to cope with an environmental risk rather than an intention to conserve, such as adaptive framing practices in response to drought, were not considered as examples of pro‐environmental behaviour in this instance. However, adaptive farming practices that were intended to avoid environmental degradation such as soil conservation and site specific forestry to reduce environmental damage from wild animals and climate change were included.

Studies were classified as applying PMT where they measured or manipulated at least one construct from the theory in order to predict or change intention and/or behaviour and made explicit reference to PMT in the introduction or methods section for the study. Accordingly, studies that measured constructs such as self‐efficacy and perceived severity that are common to a number of different theoretical approaches (Davis, Campbell, Hildon, Hobbs, & Michie, Citation2015) were only eligible for inclusion if the examination of that construct was at least partially justified on the basis of the PMT.

Data extraction

Key information from each study was extracted for the purposes of mapping and categorisation. The following information was extracted from each study

Bibliographic information (author, title, year, journal, publication type)

Sample characteristics (gender, special characteristics, country)

Study type: Prediction or intervention study

PMT constructs measured

Behaviour of interest

RESULTS

Database searches resulted in the return of 8,649 records, of which 5,200 remained once de‐duplication had been performed. The full flow of studies through the review and the number of exclusions at each stage are shown in Figure 2. In total, 22 studies were identified in the screening process and retained for the review (see Table ).

Table 2. Summary of included studies

Sample size and type

The total sample was comprised of 12,827 individuals from 22 studies. Most studies were focused on the behaviours of particular sub‐populations. These included studies that specifically sought to recruit farmers and ranchers (k = 3; n = 1,896), homeowners in high risk areas (k = 2; n = 701), tourists travelling to a particular region (k = 1; n = 512), car owners (k = 1; n = 2,974) in order to investigate their intention and/or behaviour that was specifically related to their sub‐population membership. For example, studies that specifically recruited farmers tended to investigate intention to engage in pro‐environmental farming practices. The remaining studies recruited community members (k = 8; n = 3,421) and students (k = 7; n = 3,323) and tended to investigate behaviours that are of more general relevance such as green consumerism.

The included studies were geographically diverse. In total, studies included participants from 28 countries. However, substantial geographic diversity was provided by a single study (Almarshad, Citation2017), which included data from participants in 18 countries including the only country in the African World Health Organisation (WHO) Region and the only two low income countries. Only one other study included samples from more than one country, the United States and South Korea. One study reported that participants were recruited from a country within the ‘Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region’ without reporting the specific country from which those participants were recruited (Ibrahim & Al‐Ajlouni, Citation2001). However, based on the affiliations of the authors we believe it was likely that that study was conducted in Saudi Arabia and so have coded it as such in subsequent analyses.

According to the classification of WHO Regions, six studies included participants from the Americas (n = 5,243). Of these only one was conducted in a country other than the United States (Chile). Nine studies had participants from countries in the Western Pacific (n = 4,349), including studies in Taiwan, Australia, South Korea, and China. Six studies included participants from Europe (n = 1,895) including studies in The Netherlands, Sweden, Spain, and Germany. Three studies included participants from countries in the Eastern Mediterranean region (n = 1,343; Iran, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Syria, Yemen, Egypt, Morocco, Sudan, Tunisia, Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq, Libya, and Palestine). Only one study included participants from the African region (Algeria, n = 70).

Calculation of the number of participants from some World Bank Income Regions is difficult because one study (Almarshad, Citation2017) reported a combined total for the proportion of participants from four countries (Syria, Yemen, Iraq, and Libya) which fall across two income regions. For the purposes of reporting, we have included the possible range of values and the number of samples rather than studies. When classified by World Bank Income Regions the majority of participants (n = 11,887) were recruited from ‘High Income’ countries. Eight samples came from an ‘Upper Middle Income’ Countries (n = 1,496–1,501) and five samples came from a ‘Lower Middle Income’ country (n = 210). Only one study included participants from ‘Low Income’ country (n = 2–7).

Study type

The majority of studies identified in the review were observational studies that sought to predict intention and/or behaviour on the basis of PMT constructs (k = 17). Relatively few studies sought to manipulate PMT constructs (in isolation or combination) in order to investigate their impact on intention and behaviour (k = 5).

Behaviour of interest

Many behaviours were only investigated in a single study (e.g., site specific forestry Eriksson, Citation2017; supporting the return of wolves Hermann & Menzel, Citation2013; lionfish consumption Huth et al., Citation2018). However, broadly speaking, most behaviours of interest could be characterised as involving political action or policy support (Ahern, Citation2008; Hermann & Menzel, Citation2013; Lam, Citation2015), water conservation (Kantola et al., Citation1983; Mankad et al., Citation2013; Tapsuwan et al., Citation2017), green consumerism (Horng et al., Citation2014; Hunter & Röös, Citation2016; Huth et al., Citation2018; Ibrahim & Al‐Ajlouni, Citation2001; Kim et al., Citation2013; Langbroek et al., Citation2016; Rodriguez‐Priego & Montoro‐Rios, Citation2018; Zhao et al., Citation2016), or adaptive farming and forestry (Eriksson, Citation2017; Huenchuleo et al., Citation2012; Keshavarz & Karami, Citation2016).

Interestingly, a number of studies investigated pro‐environmental intention/behaviour through the use of a composite intention/behaviour index that included a broad range of pro‐environmental behavioural targets. For example, Rainear and Christensen (Citation2017), measured intention to engage in eight pro‐environmental behaviours including: driving less and using environmentally friendly transportation, changing the light bulbs at your home to more energy saving ones, and turning down the thermostat during night or when gone. Similarly, Kim et al. (Citation2013) investigated intention to engage in seven behaviours: reducing car use; reducing cooling and heating use; participating in recycling; using reusable products; switching to fluorescent light bulbs; purchasing products produced by pro‐environmental firms, even if they are more expensive than other products; and purchasing products produced by firms that maintain nationally recommended temperatures. In both cases, researchers calculated a composite intention measure that reflected the mean of intention to engage in each behaviour.

Intention

Intention was the most commonly measured construct from within PMT.

According to PMT, intention is the proximal antecedent of behaviour. However, relatively few studies (k = 3) included examination of the relationship between intention and behaviour. Of these, two reported that intention predicted (past) behaviour within the context of a cross‐sectional study (Horng et al., Citation2014; Tapsuwan et al., Citation2017). The third, Huenchuleo et al. (Citation2012), assessed current soil conservation behaviour and willingness to pay for soil conservation (which they conceptualised as indicative of intention) in a sample of Chilean farmers. However, intention and behaviour were not associated in that study. Authors note that in their study current behaviour was performance of soil conservation behaviours without financial subsidies, whereas the willingness‐to‐pay intention measure was related to a scenario in which substantial subsidies would be applied. As such, they argue that the lack of intention–behaviour relationship may be unsurprising within this specific context.

According to PMT, intention is jointly determined by perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, maladaptive response rewards, self‐efficacy, response efficacy, and response costs. Five papers reported studies where one or more PMT construct was manipulated and the effect of the manipulation on intention was measured. Seventeen studies simply sought to predict intention or behaviour on the basis on PMT constructs. Discussion of each of these studies is included below within the subsection relating to the relevant PMT construct.

Threat appraisal

Given the range of behaviours and sub‐populations investigated in the studies there were considerable variations in the threat participants were asked to evaluate within threat appraisal measures and manipulations. Studies included generalised threats such as climate change and global warming as well as less commonly investigated threats such as water scarcity (Kantola et al., Citation1983), soil erosion (Huenchuleo et al., Citation2012), species decline (Hermann & Menzel, Citation2013; Huth et al., Citation2018), and poor air quality (Ahern, Citation2008).

Studies also varied in the referent group used when measuring threat. While many studies assessed threat appraisal in the context of threat to self, other studies also assessed the perceived threat to: society, others, coming generations, ‘people in poor countries’, the planet, and/or threat to plants and animals. Where multiple referent groups were assessed within a single study, some studies chose to combine them into a single threat appraisal measure such that scores on a perceived severity measure was the average of an individual's response to items rating the threat to each referent group. In other studies, the role of these different types of threat appraisal was assessed separately. For example, Hunter and Röös (Citation2016) measured susceptibility and severity for five different referent groups: you, coming generations, society, ‘people in poor countries’, plants and animals; and then conducted principal component analysis that found that these threat constructs were best conceptualised as a ‘threat close’ component that included both severity and susceptibility items for threat to self and threat to the coming generations and a ‘threat other’ component that included severity and susceptibility items for threats to society, ‘people in poor countries’, and plants and animals. Both threat appraisal constructs predicted intention to reduce meat consumption in response to the threat posed by climate change. Similarly, Rodriguez‐Priego and Montoro‐Rios (Citation2018), measured the threats associated with climate change with regard to threat to self, threat to future generations and threat to animals and found that only threat to self predicted past engagement in green consumerist behaviour in a model that also included coping appraisal and demographic and personality constructs.

Threat appraisal as a general construct

It is clear from the discussion of studies that measured threat through the use of multiple referents (above) that a number of studies collapsed severity and susceptibility into a single combined measure (no studies included maladaptive response rewards within the global threat appraisal construct). In some cases, the use of this combined measure occurred when the items measured an overarching risk appraisal construct within single items. For example, the item ‘How much do you think global climate change will harm you personally?’ includes an evaluation of both severity and susceptibility within one item (Rodriguez‐Priego & Montoro‐Rios, Citation2018). In other studies, separate questions were used to assess the constructs but were then combined into a single construct for analysis purposes (Hunter & Röös, Citation2016; Mankad et al., Citation2013). Some studies that used this approach presented the results of a factor analysis or similar to justify the combination of severity and susceptibility items in this manner (Mankad et al., Citation2013).

In summary, studies that took this approach to examine the intention–threat association found that threat appraisal was associated with intention to engage in water conservation behaviour (Mankad et al., Citation2013; Tapsuwan et al., Citation2017) and green consumerism (Rodriguez‐Priego & Montoro‐Rios, Citation2018). Whereas, Langbroek et al. (Citation2016) reported that threat appraisal, specifically the belief that ‘the current transport system is a danger for the environment’ was not associated with adoption of electric vehicles in a hypothetical stated choice paradigm once controlling for other factors. Similarly, Chen (Citation2016) found that threat appraisal was not associated with intention once moral obligation, trust in organisations, trust in mass media, self‐efficacy and collective efficacy were accounted for.

Severity

Ten studies examined the relationship between severity and intention or behaviour. Across the included studies, there is evidence that higher severity is associated with intention to purchase an electric vehicle (Bockarjova & Steg, Citation2014), intention to engage in energy saving tourism behaviours (Horng et al., Citation2014), intention to engage in composite pro‐environmental behaviours (Kim et al., Citation2013; Rainear & Christensen, Citation2017), intention to engage in green consumerism (Ibrahim & Al‐Ajlouni, Citation2001), intention to engage in political activism to support the reintroduction of wolves (Hermann & Menzel, Citation2013), intention to engage in sustainability behaviours (Almarshad, Citation2017), and current engagement in adaptive farming (Keshavarz & Karami, Citation2016). However, severity was not associated with support for pro‐environmental policies when controlling for the effect of other PMT constructs (Lam, Citation2015), current or intended soil conservation behaviour by Chilean farmers (Huenchuleo et al., Citation2012) or current engagement in energy saving tourism behaviours (Horng et al., Citation2014).

One study found that the severity‐intention relationship varied according to the type of behaviour under consideration and the socioeconomic status of the participants. That study examined predictors of intention to engage in low cost pro‐environmental behaviours (reduction of water and electricity use, waste, and overall household consumption) and high cost (recycling and willingness to spend extra money on environmentally friendly products) pro‐environmental behaviours among base of pyramid (i.e., low socioeconomic position) consumers and other consumers (Zhao et al., Citation2016). Among base of pyramid consumers, severity was a predictor of intention to engage in low cost behaviours, but not of high cost behaviours. Among other consumers, severity was a predictor of intention to engage in both categories of behaviours (Zhao et al., Citation2016).

Three studies manipulated perceived severity to assess the impact on intention (k = 2) or behaviour (k = 1). Two of these studies used a video‐based message to increase perceived severity, and measured the impact on intention. The results of these studies were mixed. Kantola et al. (Citation1983) manipulated the perceived severity of water shortages and measured the impact on intention to conserve water. While the intervention message was effective at increasing severity, there was no impact on intention. In contrast, Chen (Citation2016) found that a video message based on increasing severity (and susceptibility) did increase intention to reduce individual contribution to climate change. However, the interpretation of these results is complicated by the fact that Chen found that individuals in the ‘high fear’ condition actually reported less fear in post‐experimental manipulation than those in the ‘low fear’ condition. Accordingly, the study reported that the condition that experienced the greatest amount of evoked fear (confusingly named the low fear condition) were more likely to intend to engage in pro‐environmental behaviour and interpreted this as consistent with PMT. A third study that included a severity manipulation investigated the impact of a severity manipulation on purchasing behaviour (Huth et al., Citation2018). That study, (Huth et al., Citation2018), used the Becker‐Degroot‐Marschak auction paradigm in a study on green consumerism in response to species decline due to invasive lionfish and found that a severity manipulation was effective at changing consumption behaviour. However, it is important to note that the study paradigm included a measure of behaviour (willingness to pay) in a scenario where individuals were provided with money for the purpose of the study. As the authors note, the impact of a severity manipulation on actual consumer behaviour in a more ecologically valid setting is not clear (Huth et al., Citation2018).

Susceptibility

Eleven studies examined the relationship between severity and intention or behaviour. Susceptibility was also associated with farmers' intention to practice site specific forestry (Eriksson, Citation2017) and reported engagement in adaptive farming (Keshavarz & Karami, Citation2016). Across the included studies there was also evidence that perceived susceptibility is associated with individuals' intention to engage in both high and low cost private sphere pro‐environmental behaviours (Zhao et al., Citation2016), intention to purchase an electric vehicle (Bockarjova & Steg, Citation2014), intention to engage in green consumerism (Ibrahim & Al‐Ajlouni, Citation2001), intention to engage in sustainability behaviours (Almarshad, Citation2017), and intention to engage in a composite index of private sphere pro‐environmental behaviours (Kim et al., Citation2013; Rainear & Christensen, Citation2017). Horng et al. (Citation2014) reported that susceptibility did not predict intention or actual behaviour; however, the operationalisation of susceptibility in this study is unusual. Specifically, the study was interested in tourists' engagement in carbon emission reduction behaviours while travelling (e.g., towel reuse in hotels) and measured susceptibility with items such as ‘Tourist behaviour [sic] causes environment problems’ rather than items which evaluated whether individuals believed that they would experience the negative impacts of such environmental problems.

With regard to public sphere pro‐environmental behaviours, susceptibility did not predict support for pro‐environmental policies when controlling for the effect of other PMT constructs (Lam, Citation2015) but did predict students' intention to engage in political activism to support the reintroduction of wolves (Hermann & Menzel, Citation2013). However, it should be noted that Hermann and Menzel (Citation2013) defined susceptibility as the perceived probability that the return of the animal would succeed in Germany (i.e., ‘The return of the animal will be successful’) which does not seem to match the severity construct (i.e., ‘If the wolf does not become re‐established it will be a severe loss for all humans, who are not able to become acquainted with the animal’).

Only one study sought to manipulate perceived susceptibility (Huth et al., Citation2018). That study manipulated severity and as such was discussed above. In short, the study found that participants in the condition that experienced the greatest amount of evoked fear, on average, were more likely to intend to engage in pro‐environmental behaviour. However, as mentioned above, the manipulation threat in that study was complicated by the fact that the ‘high threat’ condition actually experienced less fear than the ‘low fear’ condition following the intervention.

Maladaptive response rewards

Only three studies included a measure of maladaptive response rewards. Maladaptive response rewards was found to be negatively associated with car owners intention to purchase an electric car (Bockarjova & Steg, Citation2014) and intention to engage in sustainability behaviours (Almarshad, Citation2017). However, it was not associated with intention to engage in green consumerism when controlling for susceptibility, severity, response efficacy, self‐efficacy, response costs, moral obligation, moral accountability, and moral outrage (Ibrahim & Al‐Ajlouni, Citation2001).

Adaptive coping

Whereas researchers commonly combined threat appraisal constructs, coping appraisal variables tended not to be combined into superordinate constructs. Mankad et al. (Citation2013) combined self‐efficacy and response efficacy into a single construct in their study of homeowners' water conservation intentions. The combined measure, which they labelled ‘response efficacy’ was associated with intention. Huenchuleo et al. (Citation2012) measured both response efficacy and self‐efficacy but reported that the two constructs were perfectly correlated in their sample. As such, they only included one of these coping efficacy constructs, response efficacy, which was associated with current and intended soil conservation behaviour among Chilean farmers.

Response efficacy

Excluding those studies discussed in the summary of studies of ‘adaptive coping’, 18 studies either measured or manipulated response efficacy.

Across the included studies, there is evidence that higher response efficacy is associated with a range of private sphere behaviours including farmers' intention to engage in adaptive farming (Eriksson, Citation2017) and current engagement in adaptive farming behaviour (Keshavarz & Karami, Citation2016), intention to purchase an electric vehicle (Bockarjova & Steg, Citation2014), both intended and actual energy saving tourism behaviours (Horng et al., Citation2014), intention to engage in dietary changes to reduce climate impact (Hunter & Röös, Citation2016), intention to engage in green consumerism (Almarshad, Citation2017; Ibrahim & Al‐Ajlouni, Citation2001; Rodriguez‐Priego & Montoro‐Rios, Citation2018), homeowners' intention to adopt water conservation practices in response to threat of water shortages (Tapsuwan et al., Citation2017), and intention to engage in a composite index of private sphere pro‐environmental behaviours (Kim et al., Citation2013; Rainear & Christensen, Citation2017). Two studies reported findings that were inconsistent with this pattern of results. Zhao et al. (Citation2016) investigated predictors of intention to engage in low cost pro‐environmental behaviours (reduction of water, electricity, waste, and overall household consumption) and high cost (recycling and willingness to spend extra money on environmentally friendly products) pro‐environmental behaviours among base of pyramid consumers and other consumers. Among base of pyramid consumers, response efficacy predicted intention to engage in both sets of behaviours. However, for other consumers response efficacy predicted intention to engage in low cost behaviours but not high cost behaviours. Langbroek et al. (Citation2016) reported that response efficacy was not associated with adoption of electric vehicles in a hypothetical stated choice paradigm.

Three studies investigated the relationship between response efficacy and public sphere political activism behaviours/policy support. Response efficacy was associated with intention to engage in political action to support the return of wolves (Hermann & Menzel, Citation2013) and intention to engage in political action to support pro‐environmental legislation (Ahern, Citation2008). Lam (Citation2015) found that response efficacy predicted support for policies that prohibit the leakage of air‐conditioned air in public places, restrict the minimum room temperature in public places, introduce a ‘gas guzzler tax’, and subsidise the use of renewable energy. However, it did not predict support for subsidies for public transportation or rises in electric prices. In that study response efficacy was measured using a single item for each policy.

Two studies included an experimental manipulation of response efficacy. Ahern (Citation2008) conducted an experimental study where they sought to manipulate response efficacy in order to increase intention to engage in political advocacy for two environmental issues, legislation to decrease local air pollution through emissions and a treaty to restrict global carbon emissions. However, they were not successful in manipulating response efficacy in the study. While the effect of the experimental messages (short films) on intention was not reported, given that they were not effective in changing response efficacy, the interpretation of such a comparison would not have provided meaningful causal evidence regarding the nature of the relationship between response efficacy and intention. Kantola et al. (Citation1983) manipulated the perceived response efficacy of reducing water consumption on threat of water shortages and investigated the impact on intention to conserve water. The intervention message (a short film) was effective at increasing response efficacy, however, there was no impact on intention.

Self‐efficacy

Fifteen studies examined the relationship between self‐efficacy and intentions or behaviour. Across the included studies, there is evidence that higher self‐efficacy is associated with support for policies regarding green consumer behaviours (Lam, Citation2015), intention and actual engagement in energy saving tourism behaviours (Horng et al., Citation2014), intention to reduce meat consumption for environmental reasons (Hunter & Röös, Citation2016), intention to engage in green consumer behaviours (Kim et al., Citation2013; Rainear & Christensen, Citation2017) including when controlling for other PMT constructs, moral obligation, moral accountability, and moral outrage (Ibrahim & Al‐Ajlouni, Citation2001), intention to engage in sustainability behaviours (Almarshad, Citation2017). Bockarjova and Steg (Citation2014) found self‐efficacy predicted intention to purchase an electric car both at the bivariate level and when accounting for the role of other PMT constructs. Self‐efficacy was also associated with farmers' pro‐environmental behaviours in drought conditions (Keshavarz & Karami, Citation2016), and intention to support the reintroduction of wolves (Hermann & Menzel, Citation2013). The relationship between self‐efficacy and the engagement with high‐ and low‐cost environmental behaviours was conditional on socioeconomic status, predicting low‐cost behaviours in low income respondents and high‐cost behaviours in other respondents after controlling for other PMT constructs (Zhao et al., Citation2016).

Inconsistent with the model, self‐efficacy was not associated with intention to engage in site‐specific forestry practices (Eriksson, Citation2017), nor with adoption of electric vehicles in a hypothetical stated choice paradigm (Langbroek et al., Citation2016), however, this study conceptualised self‐efficacy as the individuals' belief that they are able to satisfy their travel needs with an electric vehicle rather than a conventional vehicle. Chen (Citation2016) found that after exposure to either a high or low fear message regarding climate change, self‐efficacy was not associated with intention in either group after controlling for moral obligation, trust in organisations, trust in mass media, risk perception, and collective efficacy.

Only one study sought to manipulate self‐efficacy (Greenhalgh, Citation2011). However, individuals who received the self‐efficacy message did not differ from those in the control group with regard to post‐message self‐efficacy to reduce carbon footprint. The message was not successful in bringing about a change in intention.

Response costs

Thirteen studies examined the relationships between response costs and intentions or behaviour.

Overall, response costs were associated with intention to engage in a range of private sphere pro‐environmental behaviours including intention to engage in sustainability behaviours (Almarshad, Citation2017), intention to purchase an electric vehicle (Bockarjova & Steg, Citation2014), homeowners' intention to adopt water conservation practices (Mankad et al., Citation2013; Tapsuwan et al., Citation2017), and intention to engage in composite pro‐environmental behaviours (Rainear & Christensen, Citation2017). Zhao et al. (Citation2016) found response costs was a predictor of intention to engage in ‘high cost’ behaviours but not ‘low cost’ behaviours among both socioeconomic groups included in that study. However, when other PMT constructs were controlled for, perceived response costs were not associated with either intention to reduce meat consumption (Hunter & Röös, Citation2016) or green consumer behaviours (Ibrahim & Al‐Ajlouni, Citation2001). Specifically, response costs was not a predictor of meat reduction when controlling for other PMT constructs (Hunter & Röös, Citation2016) or a predictor of green consumer behaviour after controlling for other PMT constructs and deontic justice constructs (Ibrahim & Al‐Ajlouni, Citation2001).

With regards to adaptive farming, Eriksson (Citation2017) found that response costs were associated with intention to engage in site specific forestry practices. However, in this study, response costs were operationalised purely with regards to perceived financial costs of behaviour (Eriksson, Citation2017). Huenchuleo et al. (Citation2012) reported that response costs were not associated with intended adoption of adaptive farming practices. However, it is important to note that the study measured willingness to pay under conditions of high subsidies. Response costs were associated with current behaviour within that study. Response cost was also associated with current adaptive farming practices among farmers in Iran (Keshavarz & Karami, Citation2016).

Two studies investigated the role of response costs in public sphere political action/policy support. Both included unusual conceptualisations of response costs that make it difficult to interpret the findings. Lam (Citation2015) created a combined relative benefit construct that combined maladaptive response reward and response costs items. Relative benefit was associated with support for restrictions on minimum room temperature in public places, introduction of a ‘gas guzzler tax’, subsidies for public transportation, raising electricity prices but not prohibiting the leakage of air‐conditioned air in public places or subsidising use of renewable energy. Hermann & Menzel (2013) included a measure of barriers that the authors indicated as a component of coping appraisal (most likely response costs). While higher barriers were associated with greater intention, the construct was operationalised in a way that appears potentially inconsistent with response costs. ‘Four items measured perceived barriers and related to factors that oppose the protection of wolves, such as economic losses or other human restrictions … (i.e., “High population growth and declining habitats are making resettlement of the animal impossible”)’ (Hermann & Menzel, Citation2013, p. 156).

No studies included an experimental manipulation of response cost in order to examine the causal relationship between response cost and intention or behaviour.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this research was to identify studies that have used PMT to predict and change engagement in pro‐environmental behaviour. The comprehensive search of 132 databases identified 22 studies with 12,827 individuals. The pattern of results provides broad support for the hypothesised association between PMT constructs and a range of pro‐environmental behaviours. While the association between each construct and intention/behaviour was found to vary between studies and between behaviours—for all PMT constructs and all types of pro‐environmental behaviour there is correlational evidence for the pathway posited by the theory from at least one study.

Gaps in the literature identified in the review

There is, unfortunately, very limited evidence of causal relationships as posited by PMT on the basis of the reviewed studies. Overall, only five studies included an experimental manipulation of at least one PMT construct. Of these, a number of studies reported that the experimental manipulation was not successful in bringing about change in the PMT construct it purported to target (Ahern, Citation2008; Greenhalgh, Citation2011). These studies provide no basis on which to evaluate the causal relationship between change in the targeted PMT construct and change in intention/behaviour in the pro‐environmental behaviour context. Only three studies provided a test of causality where the experimental manipulation passed the manipulation check(s), however the results were mixed (Chen, Citation2016; Huth et al., Citation2018; Kantola et al., Citation1983). This is in contrast to previous reviews and meta‐analyses in other domains, such as health‐related behaviour (Milne et al., Citation2000), which have demonstrated that manipulation of PMT constructs has been effective at changing these behaviours. There are no valid experimental tests of the relationship between intention and response costs, self‐efficacy, or maladaptive response rewards. Of course, an absence of evidence should not be interpreted as evidence of no effect. As such, these gaps in the body of evidence do not imply that the relationship between PMT constructs and intention is not causal, rather that there are simply too few tests of causality available to fully evaluate these components of PMT. Where studies were successful in achieving change in PMT constructs but not in changing intention it is not clear whether this is because the relationship between the construct and intention is not causal or because the change in the PMT construct was of insufficient magnitude to lead to detectable change in intention. A greater number of well‐designed and well reported experimental studies are therefore needed in order to allow for the examination of the causal mechanisms within PMT in the context of pro‐environmental behaviour. Research from the health domain suggests that manipulation of severity and susceptibility are more effective at changing behaviour rather than those manipulations that focus on response efficacy or self‐efficacy (Milne et al., Citation2000; Norman, Boer, Seydel, & Mullan, Citation2015) and that the balance of fear and efficacy is important (Ruiter, Kessels, Peters, & Kok, Citation2014) in determining response to PMT‐based messages. Not surprisingly given the dearth of experimental studies in this domain, these nuances have not yet been investigated within pro‐environmental behaviour.

Another gap in the literature identified through the review is the limited number of studies that have measured certain key PMT constructs. For example, only three studies examined the relationship between maladaptive response rewards and intention. This is consistent with reviews of the application of PMT in the health context conducted by Floyd et al. (Citation2001) and Milne et al. (Citation2000) that both reported that maladaptive response rewards were frequently omitted from tests of PMT. It is perhaps more surprising that more studies did not examine the relationship between intention and behaviour. Only three studies assessed the intention–behaviour relationship and all did so cross‐sectionally. Cross‐sectional evaluations of intention–behaviour associations are likely to artificially inflate the relationship as people may change their reported intentions or behaviour in order to reduce cognitive dissonance or because of social desirability (Sniehotta, Presseau, & Araújo‐Soares, Citation2014). Further, such studies do not allow the direction of the relationship to be evaluated. The nature of pro‐environmental behaviours and populations under review sometimes make evaluation of the intention–behaviour relationship difficult to achieve (e.g., farming practices or vehicle purchasing decisions). However, this is a clear gap in the evidence base that would be useful to address, especially given the evidence that the intention–behaviour relationship varies considerably across different behaviours (McEachan, Conner, Taylor, & Lawton, Citation2011).

More complete measurement of all PMT constructs would also help to address the paucity of studies that test all PMT constructs within a single model. Most correlational studies evaluated PMT using regression or structural equation modelling. The observed relationships between PMT constructs and intention are therefore influenced by the choice of other constructs to include within the analytic model. However, as is clear from Table , very few studies actually include all PMT constructs, even excluding the infrequently measured construct of maladaptive response rewards. Additionally, some studies only evaluated the PMT within a model that also included a number of other non‐PMT constructs (e.g., Ibrahim & Al‐Ajlouni, Citation2001). The inconsistent selection of constructs from the theory in reviewed studies limits both evaluation of the relative importance of the constructs with regard to the prediction of intention, and also evaluation of PMT as a whole.

Measurement issues in the reviewed studies

Even where PMT constructs have been measured within the reviewed studies, the manner in which they are operationalised suffers from significant inconsistency between studies. Importantly, some studies appear to have operationalised some constructs inconsistently both with other studies within this domain and within the PMT literature more broadly, and with the definitions of the constructs provided within the theory. In some cases these discrepancies are relatively minor (e.g., conceptualising response costs only with regard to financial costs Eriksson, Citation2017). However, in other cases these appear to be more serious. As discussed above, these included non‐standard operationalisation of both susceptibility and response costs. This non‐standard measurement makes it difficult to evaluate the results with regard to theory and to compare results across studies. Further, few studies conducted elicitation studies to develop their scales as recommended by many authors (Norman et al., Citation2015) and as such it may be possible that the beliefs being measured are not those most salient to the population being examined. Going forward, researchers could use resources that have been developed in other areas such as the theory of planned behaviour and the health action process approach (Francis et al., Citation2004; Renner & Schwarzer, Citation2005) and conduct a belief elicitation procedure in order to ensure robust measurement of core PMT constructs.

The current review focused on pro‐environmental behaviours, which are a broad and non‐uniformly defined category of behaviours. Pro‐environmental behaviours are often categorised into sub‐classifications on the basis of their difficulty, cost, location of engagement (private vs. public sphere), action (individual vs. public), and impact (curtailing impact vs. increasing efficiency) (Bamberg & Möser, Citation2007; Larson, Stedman, Cooper, & Decker, Citation2015; Markle, Citation2013; Stern, Citation2000). While all types of pro‐environmental behaviour attempt to protect and conserve the natural environment in some manner, there are meaningful and distinct differences across behaviours within the different sub‐classifications. Interestingly, some studies included a composite pro‐environmental behaviour construct that included behaviours that crossed several domain boundaries (e.g., Kim et al., Citation2013). These behaviours differed meaningfully in terms of their difficulty, cost, or location of engagement. This is particularly concerning given that where studies included multiple behaviours without collapsing them into a single composite construct, the effects of PMT constructs were behaviour specific. This finding is consistent with the theory but decreases the ability to synthesise results across studies, especially where composite measures are used (Staats, Citation2003). Given the evidence that the role of specific PMT constructs varies even within single domains such as policy support (Lam, Citation2015), researchers would ideally refrain from the creation of composite measures. Where studies do measure multiple behaviours, comparison of the predictors rather than the creation of composite measures would be a particularly valuable contribution to the literature. Regardless of the approach, they choose to take, future researchers who employ PMT in the context of pro‐environmental behaviour must clearly outline how they conceptualise and measure the construct. This should include a detailed discussion of whether and why behaviours are combined for the purposes of analysis.

Sociodemographic diversity in the research literature

Climate change and broadly speaking environmental concerns are without a doubt global problems, effecting entire population in general. However, this review demonstrates clear selection biases within this domain of research. The majority of participants and a majority of studies are conducted in the United States of America and Europe. Furthermore, African countries are almost entirely omitted, and fewer than 10 participants come from Low Income countries. These trends are consistent with wider patterns within the psychological literature (Henrich, Heine, & Norenzayan, Citation2010). While there is no reason to infer that the constructs have different meaning in these underrepresented cultures beyond the previously discussed issues with the lack of elicitation studies, the lack of diversity does potentially limit our ability to extrapolate especially given that the relationship between PMT constructs is thought to be context specific. For example, studies within the review do indicate that the relationship between coping appraisal constructs and intention varies on the basis of both the wealth of participants and the specific behaviour of interest (Zhao et al., Citation2016). Further cross‐cultural research and research in non‐WEIRD (western, educated, industrialised, rich, and democratic) countries would provide insights into the boundary conditions of the relationships between PMT constructs and intention in the context of pro‐environmental behaviours.

Strengths and limitations of the review methodology

One of the strengths of the current study is that it is the first review to systematically identify and synthesise studies that have applied PMT to the prediction and/or change of pro‐environmental behaviours. The review provides an up‐to‐date and comprehensive summary of the empirical basis for the applying PMT within this domain. While conduct of a formal evaluation of risk of bias or the overall levels of evidence was outside of the scope of this systematic mapping review, we have identified a number of important strengths and limitations of the literature that we believe will be helpful in guiding future research using PMT in this behavioural domain. Our comprehensive search strategy and duplicate screening of all titles, abstracts, and reports allowed us to identify unpublished (theses) work, studies reported in journals not indexed in common psychology or behavioural science databases. Notably, inclusion of unpublished work allowed for the identification of the only study to experimentally manipulate self‐efficacy using the framework of PMT within pro‐environmental behaviours (Greenhalgh, Citation2011). Given the diversity in the behaviours, populations, and operationalisation of constructs we have not attempted to quantitatively synthesise results. While such a synthesis may become possible as this field of research matures, any quantitative synthesis at this time would be compromised by a lack of homogeneity in the operationalisation of constructs and the diversity in the populations and behaviour of interest.

The current review indicates what PMT constructs may be associated with or contribute to an increase in intention/behaviours within the context of pro‐environmental behaviour. However, it is important to acknowledge that there are stark differences in how pro‐environmental behaviour is conceptualised across the research field (Osbaldiston & Schott, Citation2012; Stern, Citation2000). For instance, some take a stricter impact‐orientated approach, with only those actions that actually affect the natural environment considered pro‐environmental; while others take a broader intent‐orientated approach, arguing that any action that has the intention to protect or conserve the environment can be considered a type of pro‐environmental behaviour (even if it does not cause an actual change in the natural environment; Kaiser & Wilson, Citation2004; Larson et al., Citation2015; Truelove & Gillis, Citation2018). The definition used within this review led to exclusion of studies that had applied PMT to the prediction of behaviours that are designed to lead to adaptation to climate change and natural hazards. Some of these studies were described by the original authors as studies of pro‐environmental behaviour. However, they were not eligible for inclusion because the behaviours do not protect or conserve the natural environment but rather buffer individuals from negative consequences of damage to the environment. The use of a consistent definition for inclusion and exclusion criteria is a necessary condition for the conduct of a robust systematic review. Nevertheless, it is important to recognise that the application of a different definition within this review would have led to the selection of different studies for the basis. In turn, this would have impacted the results and conclusions drawn from the review. On the basis of title and abstract screening, we believe that there is likely to be scope for separate reviews of the use of PMT within research on response to natural hazards and adaptation to climate change, which is an interesting area for future investigation.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, with the gravity that the world is facing as a result (at least in part) of human behaviour it is important to have a clear appreciation of what the factors that lead to pro‐environmental behaviours are. It appears that PMT may provide researchers with a useful framework to do this, with the caveat that more carefully designed studies that include all PMT variables and that use consistent operationalisation of PMT constructs and behaviour are needed. There is an opportunity to build on this research to design real interventions that are effective and efficacious in changing behaviour. In addition, future research is needed to investigate the intention–behaviour relationship to allow greater understanding of the difficulties of translating pro‐environmental intentions into behaviour. More longitudinal studies are needed to investigate the temporal relationships between the constructs. This combined with more experimental research will allow researchers to understand the relationships between variables and the impact of change in one construct on another and any other interaction effects there may be. Finally, as is the case in much research most studies were conducted in easy to access, convenient samples leading to an over representation of high income, white samples and this greatly limits our understanding of the domain.

raup_a_12098952_sm0001.docx

Download MS Word (16.3 KB)ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported in part by the Deakin University's Health ReseArch Capacity Building Grant ScHeme (HAtCH).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

Funding information Deakin University's Health ReseArch Capacity Building Grant ScHeme

REFERENCES

- Ahern, L. (2008). Psychological responses to environmental messages: The roles of environmental values, message issue distance, message efficacy and idealistic construal (PhD). Penn State.

- Almarshad, S. O. (2017). Adopting sustainable behavior in institutions of higher education: A study on intentions of decision makers in the MENA region. European Journal of Sustainable Development, 6(2), 89–110.

- Bamberg, S., & Möser, G. (2007). Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta‐analysis of psycho‐social determinants of pro‐environmental behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 27(1), 14–25.

- Bockarjova, M., & Steg, L. (2014). Can Protection Motivation Theory predict pro‐environmental behavior? Explaining the adoption of electric vehicles in The Netherlands. Global Environmental Change, 28, 276–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.06.010

- Bubeck, P., Wouter botzen, W. J., Laudan, J., Aerts, J. C. J. H., & Thieken, A. H. (2017). Insights into flood‐coping appraisals of protection motivation theory: Empirical evidence from Germany and France. Risk Analysis: An Official Publication of The Society For Risk Analysis, 38(6), 1239–1257.

- Campis, L. K., Prentice‐dunn, S., & Lyman, R. D. (1989). Coping appraisal and parents' intentions to inform their children about sexual abuse: A protection motivation theory analysis. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 8(3), 304–316.

- Chen, M.‐F. (2016). Impact of fear appeals on pro‐environmental behavior and crucial determinants. International Journal of Advertising, 35(1), 74–92.

- Cismaru, M., Cismaru, R., Ono, T., & Nelson, K. (2011). “Act on climate change”: An application of protection motivation theory. Social Marketing Quarterly, 17(3), 62–84.

- Clayton, S., & Brook, A. (2005). Can psychology help save the world? A model for conservation psychology. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 5(1), 87–102.

- Davis, R., Campbell, R., Hildon, Z., Hobbs, L., & Michie, S. (2015). Theories of behaviour and behaviour change across the social and behavioural sciences: a scoping review. Health Psychology Review, 9(3), 323–344.

- Eriksson, L. (2017). The importance of threat, strategy, and resource appraisals for long‐term proactive risk management among forest owners in Sweden. Journal of Risk Research, 20(7), 868–886.

- Floyd, D. L., Prentice‐dunn, S., & Rogers, R. W. (2001). A meta‐analysis of research on protection motivation theory. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30(2), 407–429.

- Francis, J., Eccles, M. P., Johnston, M., Walker, A. E., Grimshaw, J. M., Foy, R., … Bonetti, D. (2004). Constructing questionnaires based on the theory of planned behaviour: A manual for health services researchers. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Centre for Health Services Research, University of Newcastle upon Tyne.

- Gardner, G. T., & Stern, P. C. (2008). The short list: The most effective actions US households can take to curb climate change. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 50(5), 12–25.

- Garnett, S. T., & Lindenmayer, D. B. (2011). Conservation science must engender hope to succeed. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 26(2), 59–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2010.11.009

- Gatersleben, B. (2012). The psychology of sustainable transport. Psychologist, 25(9), 676–679.

- Greenhalgh, T. (2011). Assessing a combined theories approach to climate change communication (PhD). Las Vegas: University of Nevada.

- Hall, N. L., & Taplin, R. (2007). Solar festivals and climate bills: Comparing NGO climate change campaigns in the UK and Australia. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 18(4), 317–338 Retrieved from JSTOR.

- Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2–3), 61–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0999152X

- Hermann, N., & Menzel, S. (2013). Predicting the intention to support the return of wolves: A quantitative study with teenagers. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 36, 153–161.

- Horng, J.‐S., Hu, M.‐L. M., Teng, C.‐C. C., & Lin, L. (2014). Energy saving and carbon reduction behaviors in tourism—A perception study of Asian visitors from a protection motivation theory perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 19(6), 721–735.

- Huenchuleo, C., Barkmann, J., & Villalobos, P. (2012). Social psychology predictors for the adoption of soil conservation measures in Central Chile. Land Degradation & Development (Formerly Land Degradation and Rehabilitation), 23(5), 483–495.

- Hunter, E., & Röös, E. (2016). Fear of climate change consequences and predictors of intentions to alter meat consumption. Food Policy, 62, 151–160.

- Huth, W. L., Mcevoy, D. M., & Morgan, O. A. (2018). Controlling an invasive species through consumption: The case of lionfish as an impure public good. Ecological Economics, 149(C), 74–79.

- Ibrahim, H., & Al‐ajlouni, M. M. Q. (2001). Sustainable consumption. Management Decision, 56(3), 610–633.

- IPCC. (2018). Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC special report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre‐industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty.

- Kaiser, F. G., & Wilson, M. (2004). Goal‐directed conservation behavior: The specific composition of a general performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(7), 1531–1544.

- Kantola, S. J., Syme, G. J., & Nesdale, A. R. (1983). The effects of appraised severity and efficacy in promoting water conservation: An informational analysis. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 13(2), 164–182.

- Keshavarz, M., & Karami, E. (2016). Farmers' pro‐environmental behavior under drought: Application of protection motivation theory. Journal of Arid Environments, 127, 128–136.

- Kidd, L. R., Bekessy, S. A., & Garrard, G. E. (2019). Neither hope nor fear: Empirical evidence should drive biodiversity conservation strategies. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 34(4), 278–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2019.01.018

- Kim, S., Jeong, S.‐H., & Hwang, Y. (2013). Predictors of pro‐environmental behaviors of American and Korean Students: The application of the theory of reasoned action and protection motivation theory. Science Communication, 35(2), 168–188.

- Koger, S. M., & Winter, D. D. (2011). The psychology of environmental problems: Psychology for sustainability. New York: Psychology Press.

- Laffoley, D. D., & Baxter, J. (Eds.). (2016). Explaining ocean warming: Causes, scale, effects and consequences. Switzerland: IUCN Gland.

- Lam, S.‐P. (2015). Predicting support of climate policies by using a protection motivation model. Climate Policy, 15(3), 321–338.

- Langbroek, J. H. M., Franklin, J. P., & Susilo, Y. O. (2016). The effect of policy incentives on electric vehicle adoption. Energy Policy, 94, 94–103.

- Lange, F., & Dewitte, S. (2019). Measuring pro‐environmental behavior: Review and recommendations. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 63, 92–100.

- Larson, L. R., Stedman, R. C., Cooper, C. B., & Decker, D. J. (2015). Understanding the multi‐dimensional structure of pro‐environmental behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 43, 112–124.

- Lebek, B., Uffen, J., Neumann, M., Hohler, B., & Breitner, M. H. (2014). Information security awareness and behavior: A theory‐based literature review. Management Research Review, 37(12), 1049–1092.

- Maddux, J. E., & Rogers, R. W. (1983). Protection motivation and self‐efficacy: A revised theory of fear appeals and attitude change. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 19(5), 469–479.

- Mankad, A., Greenhill, M., Tucker, D., & Tapsuwan, S. (2013). Motivational indicators of protective behaviour in response to urban water shortage threat. Journal of Hydrology, 491, 100–107.

- Markelj, J. (2009). Using protection motivation theory to examine environmental communications: The review of in‐home energy saving advertisements. International Journal of Sustainability Communication, 4, 113–124.

- Markle, G. L. (2013). Pro‐environmental behavior: Does it matter how it's measured? Development and validation of the pro‐environmental behavior scale (PEBS). Human Ecology, 41(6), 905–914.

- Mceachan, R. R. C., Conner, M., Taylor, N. J., & Lawton, R. J. (2011). Prospective prediction of health‐related behaviours with the theory of planned behaviour: A meta‐analysis. Health Psychology Review, 5(2), 97–144.

- Milne, S., Sheeran, P., & Orbell, S. (2000). Prediction and intervention in health‐related behavior: A meta‐analytic review of protection motivation theory. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30(1), 106–143.

- Nelson, K., Cismaru, M., Cismaru, R., & Ono, T. (2011). Water management information campaigns and protection motivation theory. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 8(2), 163–193.

- Nisbet, E. K. L., & Gick, M. L. (2008). Can health psychology help the planet? Applying theory and models of health behaviour to environmental actions. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 49(4), 296–303. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013277

- Norman, P., Boer, H., Seydel, E. R., & Mullan, B. (2015). Protection motivation theory. In Predicting and changing health behaviour: Research and practice with social cognition models (3rd ed.). Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Osbaldiston, R., & Schott, J. P. (2012). Environmental sustainability and behavioral science: Meta‐analysis of proenvironmental behavior experiments. Environment and Behavior, 44(2), 257–299.

- Pike, C., Doppelt, B., & Herr, M. (2010). Climate communications and behavior change: A guide for practitioners. Retrieved from Climate Leadership Initiative website: https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/xmlui/handle/1794/10708.

- Prentice‐dunn, S., & Rogers, R. W. (2001). Protection motivation theory and preventive health: Beyond the Health Belief Model. Health Education Research, 1(3), 153–161.

- Pronello, C., & Gaborieau, J.‐B. (2018). Engaging in pro‐environment travel behaviour research from a psycho‐social perspective: A review of behavioural variables and theories. Sustainability, 10(7), 2412. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072412

- Rainear, A. M., & Christensen, J. L. (2017). Protection motivation theory as an explanatory framework for proenvironmental behavioral intentions. Communication Research Reports, 34(3), 239–248.

- Renner, B., & Schwarzer, R. (2005). Risk and health behaviors: Documentation of the scales of the research project: “Risk Appraisal Consequences in Korea” (RACK). Retrieved from http://www.gesundheitsrisiko.de/docs/RACKEnglish.pdf.

- Rettie, R., Burchell, K., & Riley, D. (2012). Normalising green behaviours: A new approach to sustainability marketing. Journal of Marketing Management, 28(3–4), 420–444.

- Rodriguez‐priego, N., & Montoro‐rios, F. J. (2018). How cultural beliefs and the response to fear appeals shape consumer's purchasing behavior toward sustainable products. In A. Leal‐millan, M. Peris‐ortiz, & A. Leal‐rodríguez (Eds.), Sustainability in innovation and entrepreneurship. Innovation, technology, and knowledge management. Cham: Springer.

- Rogers, R. W., Prentice‐dunn, S., & Gochman, D. S. (1997). Protection motivation theory. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

- Ruiter, R. A. C., Kessels, L. T. E., Peters, G.‐J. Y., & Kok, G. (2014). Sixty years of fear appeal research: Current state of the evidence. International Journal of Psychology: Journal International De Psychologie, 49(2), 63–70.

- Scharks, T. (2016). Threatening Messages in Climate Change Communication (Thesis, University of Washington). Retrieved from https://digital.lib.washington.edu:443/researchworks/handle/1773/36393.

- Sniehotta, F. F., Presseau, J., & Araújo‐soares, V. (2014). Time to retire the theory of planned behaviour. Health Psychology Review, 8(1), 1–7.

- Snilstveit, B., Vojtkova, M., Bhavsar, A., Stevenson, J., & Gaarder, M. (2016). Evidence & gap maps: A tool for promoting evidence informed policy and strategic research agendas. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 79, 120–129.

- Staats, H. (2003). Understanding proenvironmental attitudes and behavior: An analysis and review of research based on the theory of planned behavior. In M. Bonnes, T. Lee, & M. Bonaiuto (Eds.), Psychological theories for environmental issues (pp. 171–201). Aldershot, UK: Ashgate.

- Steel, B. S. (1996). Thinking globally and acting locally? Environmental attitudes, behaviour and activism. Journal of Environmental Management, 47(1), 27–36.

- Stern, P. C. (2000). New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 407–424.