Abstract

Objective

Despite recent research demonstrating significant impact of fear of happiness on different forms of well‐being, particularly flourishing, few studies have focused on the examination the potential mediators that might play an important role in terms of such impact. This study is intended to evaluate the mediator roles of agency and pathways in the relationship between fear of happiness and flourishing.

Method

Participants consisted of 226 university students (169 males, 57 females) and aged between 18 and 29 (M = 21.17, SD = 1.72). They completed the Dispositional Hope Scale, Fear of Happiness Scale and Flourishing Scale.

Results

In terms of the findings, correlation analysis provided initial evidence supporting the link between fear of happiness, hope, and flourishing. The findings of the parallel multiple mediation analysis indicated that agency and pathways accounted for significant variance in the association between flourishing and fear of happiness controlling for gender and socioeconomic status.

Conclusion

Overall, our results offered support for the link between hope and fear of happiness, suggesting that experiencing less fear regarding engaging in happiness‐related beliefs increases levels of motivation for achieving desired goals (agency) and perceived capacity to produce the means towards achieving life goals (pathways) which in turn increase levels of flourishing. The implications of these findings are further discussed.

What is already known about this topic

Fear of happiness addresses the beliefs that experiencing positive emotions particularly happiness may result in detrimental life outcomes.

Hope is comprised of two components: agency and pathways.

Fear of happiness was negatively and significantly associated with various forms of well‐being and particularly flourishing. There is some evidence that hope agency and hope pathways might mediate the relationship between fear of happiness and flourishing.

What this topic adds

The current study expands the field of well‐being and investigates whether fear of happiness is related to hope components, namely agency and pathways.

The current study adds to the knowledge pertaining to the mechanism underlying the relationship between fear of happiness and flourishing among university students.

The current study offers a support that hope agency and hope pathways mediates and accounts for significant variance in the association between flourishing and fear of happiness.

INTRODUCTION

Happiness is considered as one of the more valuable goals to achieve in the majority of societies across the globe. In Western cultures in particular, the pursuit of happiness and well‐being is viewed as one of the basic human rights. On the contrary, many non‐Western societies tend to disfavour happiness contextually as it is believed to lead to suffering or invite evil eyes, envy or rivalry in particular situations (Joshanloo et al., Citation2014). For cultural or personal reasons, happiness is sometimes attributed as a potential cause for detrimental outcomes on individuals' lives and well‐being, a particular belief system that is referred to as fear of happiness. Fear of happiness is a recent concept, addressing relatively stable beliefs that experiencing positive emotions will have negative outcomes and, in order to avoid unpleasant consequences, individuals susceptible to fear of happiness tend to suppress their authentic positive feelings, prevent success, joy or indeed any action that might be associated with them (Joshanloo, Citation2013; Joshanloo, Citation2018).

Although avoiding happiness is believed to secure the safety and well‐being of individuals, steering away from positive emotions such as happiness may in itself lead to significant negative life outcomes. In this regard, the literature cites few—although important—studies to that demonstrate the crucial impact of fear of happiness on positive and negative psychological concepts. Several studies supported the idea that individuals with fear of happiness experience decreased levels of positive affect and psychological well‐being and increased levels of negative affect (e.g., Joshanloo, Citation2013; Yildirim, Citation2019; Yildirim & Aziz, Citation2017; Yildirim & Belen, Citation2018). Likewise, empirical studies seem to demonstrate that fear of happiness is associated with lessened life satisfaction, self‐esteem and resilience, and heightened externality of happiness, a concept which can be considered a negative life outcome (Yildirim & Aziz, Citation2017; Yildirim, Barmanpek, & Farag, Citation2018; Yildirim & Belen, Citation2019).

As studies have revealed, fear of happiness can be linked to various aspects of mental well‐being, demonstrating the importance of the concept in terms of individuals' mental health. One of these important well‐being aspects is surely flourishing due to the concept's inclusive nature. Flourishing is an inclusive index of mental well‐being and encompasses an array of well‐being indices within a single concept (Keyes, Citation2002). In essence, well‐being has been viewed in different ways over recent decades. It was conceptualised as the absence of psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety and depression, rather than presence of positive functioning (Ryff & Keyes, Citation1995). With the positive psychology movement, positive functioning has been viewed as important evidence of well‐being rather than the absence of human suffering. Thus, later explanation expanded the idea of well‐being through a positive psychological approach based on two streams of philosophical understanding: hedonic and eudaimonic well‐being. Hedonic well‐being primes the current states of happiness, experiencing pleasure and enjoyment and avoidance of pain, while eudaimonic well‐being values possessing purpose in life, searching and finding meaning and reaching one's true potential (Keyes, Shmotkin, & Ryff, Citation2002). Flourishing combines both hedonic and eudaimonic well‐being into one concept and so includes aspects of both feeling good and effective positive functioning (Huppert & So, Citation2013). As such, several scholars have highlighted the comprehensive nature of flourishing as the construct encompasses an array of positive mental health indicators such as emotional, psychological and social well‐being (Keyes, Citation2002), optimism, purpose in life, relationship, and self‐esteem (Diener et al., Citation2010).

Flourishing is still a growing field in the psychology literature and studies continue to investigate the relationship between flourishing and various other constructs. An array of studies have documented the association between flourishing and various negative life outcomes such as anxiety and depression (Schotanus‐Dijkstra et al., Citation2017), bullying (Nel, Citation2019), and also positive psychological functioning indices such as achievement (e.g., Datu, Citation2018), prosocial behaviour (Moradi, Van Quaquebeke, & Hunter, Citation2018) and emotional intelligence (Callea, De Rosa, Ferri, Lipari, & Costanzi, Citation2019). One line of research has specifically focussed on the link between flourishing and affective constructs as this concept combines the affective aspects of well‐being. For instance, Conner, DeYoung, and Silvia (Citation2017)) found flourishing to be related to increased levels of positive affect and decreased levels of negative affect. Likewise, one study by Fredrickson and Losada (Citation2005) revealed that individuals have to experience positive affect three times more than negative affect in order for an individual to flourish. As most of the studies focus on positive and negative affect, one study by Yildirim (Citation2019) examined the relationship between flourishing and fear of happiness. The study documented that individuals with higher levels of flourishing experienced lower levels of fear of happiness, and that this relationship was mediated by the construct resilience. This study is important in terms of illuminating the mechanism underlying the relationship between flourishing and fear of happiness. Yet, improved understanding is needed in terms of other potential mediators. In this regard, hope appears to be an important construct to investigate in terms of gaining a deeper understanding of the mechanism underlying fear of happiness and well‐being.

Hope refers to an individual's perceived ability and capacity to attain their future goals via producing mental energy and generating routes towards them. Snyder's trait hope theory (Snyder et al., Citation1991), the approach adopted in this research, grounds hope based on future‐oriented cognitions, and conceptualises hope as composed of two related yet distinct components: agency (will‐power) and pathways thinking (way‐power). Agency refers to the motivational aspect of hope manifesting itself in initiating or maintaining goal pursuits while pathways conveys the perceived capacity to generate the means towards a desired goal or indeed to devise alternative means when the targeted goal is blocked.

Compared to the field of fear of happiness or flourishing, the concept of hope is well‐documented in the literature. A number of studies support the link between hope and various forms of well‐being. For instance, studies revealed that hope is associated with decreased levels of anxiety (e.g., Martins et al., Citation2018), depression (e.g., Taysi, Curun, & Orcan, Citation2015), negative affect (Yalçın & Malkoç, Citation2015) and increased levels of subjective and psychological well‐being (Belen, Citation2017). Yet, the investigations of the link between hope and fear of happiness as pertaining to well‐being remains effectively unstudied. As noted, fear of happiness conveys the avoidance of situations that may evoke feelings of happiness. According to hope theory (Snyder et al., Citation1991), hope, with its distinct yet related components, is associated with happiness‐related situations, both conceptually and empirically. Conceptually, possessing a goal and achieving the desired goal through agency and pathways thinking are linked to positive emotions (Lopez et al., Citation2000) and this potential may appear as an invitation for mishap among individuals who experience fear of happiness. Thus, such individuals may negate the necessary motivation to initiate and sustain goal‐directed thinking (agency) and avoid generating routes towards desired goals (pathways). As such, Carver and Scheier (Citation1981, p. 223) argued that experiencing fear interrupts ongoing behaviour via intrusive questions regarding whether one is capable of completing the attempted or planned task which in turn might result in goal disengagement. In this regard, there is a potential risk that experiencing happiness‐related fears might influence the self‐expectation that goals can be achieved. Empirical studies have also demonstrated that hope can be associated with positive emotion‐related concepts such as increased levels of positive affect (e.g., Malinowski & Lim, Citation2015), life satisfaction (e.g., Jiang, Huebner, & Hills, Citation2013), and self‐esteem (e.g., Du, Bernardo, & Yeung, Citation2015). Thus, individuals with fear of happiness might steer away from possessing hope, agentic, and pathways thinking. In this regard, the investigation of any potential link between hope and fear of happiness is vital.

Present study

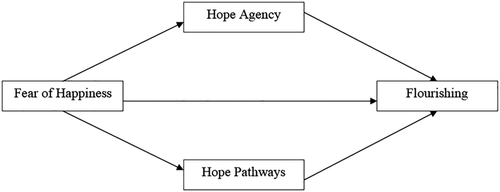

In the present study, we examined whether the relationship between fear of happiness and flourishing among Turkish undergraduate students was mediated by students' levels of hope. We hypothesized that students with low levels of fear of happiness were more likely to report high levels of hope and flourishing. As hope is a multidimensional construct that includes agency and pathways, we tested the mediation analyses for each of these components simultaneously by conducting a parallel multiple mediation analysis. In particular, we hypothesize that (a) fear of happiness is negatively associated with agency, pathways, and flourishing; (b) agency and pathways are positively associated with flourishing; and (c) agency and pathways mediate the relationship between fear of happiness and flourishing.

METHOD

Participants

Participants comprised of 226 university students (169 males and 57 females) enrolled in various undergraduate programs at Bursa Uludağ University, Turkey. Their ages ranged from 18 to 29, with a mean age of 21.17-years (SD = 1.72). One hundred ninety‐eight participants reported that they had medium perceived socioeconomic level, 14 participants reported to have low socioeconomic level, 11 high and three very low. This was a convenience sample and participants who agreed to collaborate were asked to give some of their demographic information such as age, gender and perceived socioeconomic status.

Measures

Hope

Hope was measured using the Dispositional Hope Scale (Snyder et al., Citation1991). The scale consists of 12 items and a two‐factor structure. Respondents rated each item on an 8‐point scale (1 = definitely false, 8 = definitely true). The sample items are “I energetically pursue my goals” (agency) and “I can think of many ways to get out of a jam” (pathways). The scale subscales assess agency (four items) and pathways (four items). There are also four‐filler items on the scale to minimise the subject‐related bias. The scores for each subscale were computed by summing the response of the respective items. Turkish adaptation of the scale demonstrated satisfactory evidence of reliability and validity (Tarhan & Bacanlı, Citation2015). In this study, the reliability statistics for the scale subscales (agency, α = .73, pathways, α = .72) were above the adequate level of α > .70. Higher scores refer to higher levels of agency and pathways.

Fear of happiness

Fear of happiness was measured by the Fear of Happiness Scale (Joshanloo, Citation2013). Respondents rated 5 items on a 7‐point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). The sample items are “I prefer not to be too joyful, because usually joy is followed by sadness.” and “I believe the more cheerful and happy I am, the more I should expect bad things to occur in my life.” The score for the scale was computed by adding the scores of all items. Higher scores refer to higher levels of fear of happiness. Reliability and validity studies of the Turkish version of the scale were carried out by Yildirim and Aziz (Citation2017) who provided good evidence of reliability and validity. The reliability statistics for the scale in this study was .91, reflecting excellent internal consistency reliability. Higher scores refer to higher levels of fear of happiness.

Flourishing

Flourishing was assessed using the Flourishing Scale (Diener et al., Citation2010). Respondent rated 8 items on a 7‐point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Sample items are “I lead a purposeful and meaningful life.” and “My social relationships are supportive and rewarding.” The scale total score was estimated by summing the scores of all items. Higher scores reflect greater flourishing in significant areas of human functioning. Turkish adaptation of the scale produced satisfactory psychometric properties of for scale (Telef, Citation2001). In this study, the reliability statistics for the flourishing scale (α = .79) was satisfactory by exceeding the adequate level of α > .70.

Procedure

This study formed part of a larger research project. Self‐report measures were used in data collection. The administration of the measures was carried out via online survey software. Students from different departments were contacted by mailing lists and were requested to circulate the invitation to partake the research to other students in an attempt to obtain a larger sample size. Before completing the measures, participants were given information about the research aims and characteristics via the first page of the online survey. All participants were assured about anonymity of the participation and the confidentiality of the information. Before continuing, they had to confirm their agreement as to participation or they were freed to withdraw the survey at any time during filling out the survey. Otherwise, they were discontinued. An informed consent was obtained from all participants for all measures that were administered for the data collection. Other than demographic information, all questions were mandatory to answer, and participants could only proceed from one page to another after answering all questions. Participants were not paid in exchange for their participations. The study protocol was approved by the ethic committee of Bursa Uludağ University, Turkey. This study was carried out according to the Declaration of Helsinki code of ethics.

Data analysis

Univariate outliers were investigated using z test in which all raw scores were transferred into z scores where scores falling outside the convention of −3.29 and +3.29 were regarded as outliers (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2001). With this approach, 13 cases were found to be outliers and thus removed from further analysis. In the data analysis, skewness and kurtosis values were employed to determine normal distribution. Pearson correlation was used to explore the correlations between all study variables, namely, fear of happiness, agency, pathways, and flourishing. The PROCESS macro for SPSS was used to perform the parallel multiple mediation analysis (model 4; Hayes, Citation2013). As several studies pointed out that hope is influenced by various demographic variables including gender (Belen, Citation2017) and socioeconomic status (Snyder, Citation2000, p. 227), such variables were controlled in the mediation model.

RESULTS

Descriptive and correlation analyses

Table reports the minimums, maximums, means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis statistics for all variables assessed in this study. As shown in Table , no severe violations of normal hypotheses were encountered (e.g., skewness from −0.65 to 0.89, kurtosis from−0.37 to 0.65) (West, Finch, & Curran, Citation1995). According to Table , participants described themselves as having low levels of fear of happiness where the mean score for the scale was below the median score of the scale, and high levels of agency, pathways and flourishing where the mean score for each scale was above the median score of the scales.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for main study variables

Table reports bivariate linear correlations for all variables assessed in this study. The importance of the emerging correlational results was evaluated through effect size. Cohen (Citation1988, Citation1992) recommended a rule of thumb for the assessment of effect size where a value falls within .1 ≤ r < .3 should be considered as a small effect, a value within .3 ≤ r < .5 as a medium effect, and a value of r > = .5 as a large effect. Fear of happiness was negatively correlated with agency, pathways and flourishing with small to medium effect. The correlations between flourishing with both agency and pathways were .71 and .53 (large effect), respectively.

Table 2. Intercorrelations between demographics and main study variables

Mediation analysis

Before conducting mediation analyses, we carried out variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance tests to ensure that there were no multicollinearity issues among the independent variables in the proposed mediation models. For mediation models, all VIFs ranged between 1.05 and 1.51 and all tolerance scores ranged between .66 and .93 suggesting no issues regarding multicollinearity.

In order to examine the mediator roles of agency and pathways in the same model, a parallel multiple mediation analysis was employed using the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Model 4; Hayes, Citation2013). PROCESS macro is a computational program, which is a regression‐based procedure, to examine mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis with observed variables (Hayes, Citation2013). To analyse the parallel multiple mediation model of the relationship between fear of happiness and flourishing (Figure 1), the bias‐corrected bootstrap method was performed as based on 5.000 bootstrap iterations and confidence intervals (CI) of 95%.

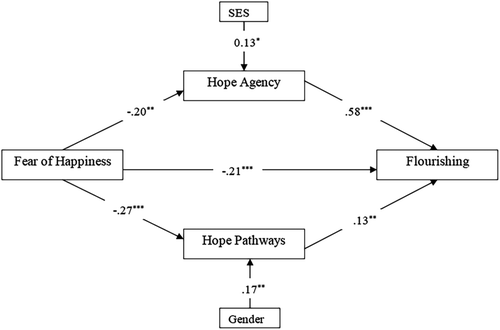

Firstly, fear of happiness was entered as an independent variable (X), flourishing as an outcome variable (Y), and agency and pathways as mediator variables (M1 and M2). Age, gender, and socioeconomic status were controlled in each model. In Model 1, we estimated the effect of fear of happiness on agency (Mediator 1) and in Model 2, on pathways (Mediator 2). In Model 3, the effects of fear of happiness and both mediators (agency and pathways) were estimated on flourishing. Table indicates the results of three regression models. Furthermore, the results of the parallel multiple mediation analysis indicated that the total effect of fear of happiness on flourishing was −0.27, SE = 0.04, (p < .001), CI [−0.36, −0.18]. Likewise, the direct effect of fear of happiness on flourishing was still significant, β = −0.21, SE = 0.03, CI [−0.22, −0.09]. Additionally, there was a significant indirect effect of fear of happiness on flourishing through agency, β = −0.11, SE = 0.03, CI [−0.19, −0.04], and through pathways, β = −0.03, SE = 0.04, CI [−0.08, −0.02]. Based on contrasts test of the mediating effects, the mediator role of agency (indirect effect via agency) was significantly stronger than the mediating role of pathways, B = −0.08, SE = 0.04, CI [−0.17, −0.01] (see Figure 2 for path coefficients).

Table 3. Direct and indirect effects of fear of happiness on flourishing

DISCUSSION

Fear of happiness, a belief system that excess happiness may result in adverse life outcomes, has an important impact on individuals' well‐being, particularly flourishing. Thus, the mechanism behind this link through hope was investigated in the current study. In this regard, the present study evaluated whether (a) hope was linked to fear of happiness and flourishing and (b) hope mediated the relationship between fear of happiness and flourishing. The study demonstrated two main results: (a) increased levels of hope were related to decreased levels of fear of happiness; and (b) hope agency and pathways mediated the relationship between fear of happiness and flourishing. Therefore, our first hypothesis, that higher hope scores were associated with lower scores on fear of happiness and higher levels of flourishing, was validated. Second, mediation analyses for the proposed model demonstrated that individuals with lower levels of fear of happiness produced greater agentic and pathways thinking, and in turn greater flourishing.

For the first hypothesis of the study, participants who reported higher levels of hope also reported lower levels of fear of happiness. This finding was consistent with the theoretical conceptualizations of both fear of happiness and hope, and indeed empirical studies regarding the constructs. Conceptually, hope refers to goal‐directed pursuits, and achieving a desired goal is linked to greater subjective well‐being and happiness (e.g., Snyder et al., Citation1991). Empirical studies also demonstrated that possessing agentic and pathways thinking is associated with lessened negative affect, heightened psychological well‐being, life satisfaction, and positive affect, such as happiness (Belen, Citation2017). Thus, one possible explanation for the finding is that individuals with fear of happiness might engage less in happiness‐provoking activities such as possessing a goal and achieving a goal through agency and pathways thinking. Additionally, the literature is in consensus with a negative association between hope and negative affective constructs (e.g., negative affect) and dysfunctional forms of well‐being (e.g., depression). In considering fear of happiness to be a dysfunctional belief system and a maladaptive concept, the reverse association between hope and fear of happiness is compatible with the literature.

With regard to the mediation analyses, the findings suggested that agency and pathways mediated the relationship between fear of happiness and flourishing. As the study by Yildirim (Citation2019) and the findings of this study revealed, less fear of happiness is linked with greater flourishing. Based on mediation analyses, the current study suggests that one's high level of flourishing is impacted by one's low level of fear of happiness. Additional to this path, low levels of fear of happiness contribute to high agentic and pathways thinking, which in turn contributes to higher levels of flourishing. The findings showed that both concepts of fear of happiness and hope, particularly the components of hope, are crucial to individuals experiencing positive psychological functioning, positive social functioning, and living within the optimal range of human functioning. This finding is consistent with previous research. Literature documents support the findings regarding the strong link between flourishing and hope (Khodarahimi, Citation2013), and particularly components of hope (Daugherty et al., Citation2018). In documenting large effect sizes between agency/pathways and flourishing, studies highlight the importance of one's self‐perception regarding the capability to achieve one's targeted goals (agency) and perceived ability to produce routes towards goals (pathways) on one's optimal positive functioning.

In terms of the path regarding fear of happiness and hope components, this study is the first to investigate such a relationship to the best of our knowledge. The findings are in line with the literature showing the mechanism underlying between fear of happiness and well‐being in relation to positive constructs such as resilience (Yildirim, Citation2019). In terms of the results regarding pathways and fear of happiness, the broaden‐and‐build theory of positive and negative emotions provides a framework for the results (Fredrickson, Citation2001). According to this theory, negative emotions narrow individuals' thought‐action repertoire and result in the creation of fewer options with which to react to a particular situation. As one of the negative emotional traits, fear of happiness might yield a narrowing down in options for reaction and influence the production of fewer attainable routes for goal achievement. On the contrary, pathways thinking helps individuals to generate multiple routes to some identified goal. In this regard, the results are in line with the conceptual framework for pathways and fear of happiness.

Given the lack of research in to the relationship between hope and fear of happiness, the results of this study are noteworthy as they underscore the idea of hope as a mediator resource on the relationship between fear of happiness and flourishing, an integrative concept encompassing social, emotional, hedonic, and eudaimonic well‐being. Although the current study sheds light the underlying mechanism with regard to how avoidance of positive genuine feelings influences individuals' levels of flourishing through agency and pathways thinking, it is important to note that some of the associated factors might restrict the generalizability of the results; chief among these limitations was the cross‐sectional nature of the study. In this regard, replication of the study with a longitudinal or experimental design might be fruitful for causal inferences. The second limitation emerges as the data was drawn among university students as a convenient sampling method which might also limit generalizability. For future studies, the use of a randomly drawn sample is suggested. Despite these limitations, we argue the findings presented in this study provide an important first step in addressing the link between fear of happiness and agency/pathways and contributes to the knowledge associated with the theoretical and empirical underpinnings of an integrative and inclusive form of well‐being.

In conclusion, this study has explored the role of hope in the relationship between fear of happiness and flourishing. The results indicated that there is a link between hope and fear of happiness and experiencing less fear with regard to engaging in happiness‐provoking activities that increase the level of motivation for achieving desired goals (agency) and the perceived capacity to produce the means towards these goals (pathways), and which in turn increases levels of flourishing.

REFERENCES

- Belen, H (2017). Emotional and cognitive correlates of hope. (Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation). University of Leicester, Leicester, UK

- Callea, A., De rosa, D., Ferri, G., Lipari, F., & Costanzi, M. (2019). Are more intelligent people happier? Emotional intelligence as mediator between need for relatedness, happiness and flourishing. Sustainability, 11(4), 1022.

- Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. E. (1981). Attention and self‐regulation: A control‐theory approach to human behaviour. New York: Springer‐Verlag.

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159.

- Conner, T. S., Deyoung, C. G., & Silvia, P. J. (2017). Everyday creative activity as a path to flourishing. Journal of Positive Psychology., 13(2), 181–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1257049

- Datu, J. A. D. (2018). Flourishing is associated with higher academic achievement and engagement in Filipino undergraduate and high school students. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19(1), 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9805-2

- Daugherty, D. A., Runyan, J. D., Steenbergh, T. A., Fratzke, B. J., Fry, B. N., & Westra, E. (2018). Smartphone delivery of a hope intervention: Another way to flourish. PLoS One, 13(6), e0197930. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197930

- Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim‐prieto, C., Choi, D. W., Oishi, S., & Biswas‐diener, R. (2010). New well‐being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97(2), 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y

- Du, H., Bernardo, A. B., & Yeung, S. S. (2015). Locus‐of‐hope and life satisfaction: The mediating roles of personal self‐esteem and relational self‐esteem. Personality and Individual Differences, 83(2015), 228–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.04.026

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden‐and‐build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226 doi: 10.1037//0003‐066x.56.3.218.

- Fredrickson, B. L., & Losada, M. F. (2005). Positive affect and the complex dynamics of human flourishing. American Psychologist, 60(7), 678–686 doi: 10.1037/0003‐066X.60.7.678.

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression‐based approach. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Huppert, F. A., & So, T. T. (2013). Flourishing across Europe: Application of a new conceptual framework for defining well‐being. Social Indicators Research, 110(3), 837–861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9966-7

- Jiang, X. U., Huebner, E. S., & Hills, K. J. (2013). Parent attachment and early adolescents' life satisfaction: The mediating effect of hope. Psychology in the Schools, 50(4), 340–352. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21680

- Joshanloo, M. (2013). The influence of fear of happiness beliefs on responses to the satisfaction with life scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 54(5), 647–651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.11.011

- Joshanloo, M. (2018). Optimal human functioning around the world: A new index of eudaimonic well‐being in 166 nations. British Journal of Psychology, 109(4), 637–655. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12316

- Joshanloo, M., Lepshokova, Z. K., Panyusheva, T., Natalia, A., Poon, W. C., Yeung, V. W. L., … Tsukamoto, S. (2014). Cross‐cultural validation of fear of happiness scale across 14 national groups. Journal of Cross‐Cultural Psychology, 45(2), 246–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022113505357

- Keyes, C. L. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, 43(2), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.82.6.1007

- Keyes, C. L., Shmotkin, D., & Ryff, C. D. (2002). Optimizing well‐being: The empirical encounter of two traditions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 1007–1022.

- Khodarahimi, S. (2013). Hope and flourishing in an Iranian adults' sample: Their contributions to the positive and negative emotions. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 8(3), 361–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-012-9192-8

- Lopez, S. J., Gariglietti, K. P., Mcdermott, D., Sherwin, E. D., Floyd, R. K., Rand, K., & Snyder, C. R. (2000). Hope for the evolution of diversity: On levelling the field of dreams. In C. R. Snyder (Ed.), Handbook of hope (pp. 224). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Malinowski, P., & Lim, H. J. (2015). Mindfulness at work: Positive affect, hope, and optimism mediate the relationship between dispositional mindfulness, work engagement, and well‐being. Mindfulness, 6(6), 1250–1262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0388-5

- Martins, A. R., Crespo, C., Salvador, Á., Santos, S., Carona, C., & Canavarro, M. C. (2018). Does hope matter? Associations among self‐reported hope, anxiety, and health‐related quality of life in children and adolescents with cancer. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 25(1), 93–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-018-9547-x

- Moradi, S., Van quaquebeke, N., & Hunter, J. A. (2018). Flourishing and prosocial behaviours: A multilevel investigation of national corruption level as a moderator. PLoS One, 13(7), e0200062. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200062

- Nel, E. C. (2019). The impact of workplace bullying on flourishing: The moderating role of emotional intelligence. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 45(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v45i0.1603

- Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well‐being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719–727. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022658

- Schotanus‐dijkstra, M., Drossaert, C. H., Pieterse, M. E., Boon, B., Walburg, J. A., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2017). An early intervention to promote well‐being and flourishing and reduce anxiety and depression: A randomized controlled trial. Internet Interventions, 9(2017), 15–24.

- Snyder, C. R. (Ed.). (2000). Handbook of hope: Theory, measures, and applications. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Snyder, C. R., Harris, C., Anderson, J. R., Holleran, S. A., Irving, L. M., Sigmon, S. T., … Harney, P. (1991). The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(4), 570–585. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.60.4.570

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2001). Using multivariate statistics (4th ed.). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Tarhan, S., & Bacanlı, H. (2015). Adaptation of dispositional hope scale into Turkish: Validity and reliability study. The Journal of Happiness & Well‐Being, 3(1), 1–14.

- Taysi, E., Curun, F., & Orcan, F. (2015). Hope, anger, and depression as mediators for forgiveness and social behavior in Turkish children. The Journal of Psychology, 149(4), 378–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2014.881313

- Telef, B. B. (2001). The validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the psychological well‐being. In Paper presented at the 11th National Congress of counselling and guidance, October 3–5. Selçuk‐İzmir: Turkey.

- West, S. G., Finch, J. F., & Curran, P. J. (1995). Structural equation models with non‐normal variables: Problems and remedies. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications (pp. 56–75). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Yalçın, I., & Malkoç, A. (2015). The relationship between meaning in life and subjective well‐being: Forgiveness and hope as mediators. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(4), 915–929. https://doi.org/10.1007/s1090

- Yildirim, M. (2019). Mediating role of resilience in the relationships between fear of happiness and affect balance, satisfaction with life, and flourishing. Europe's Journal of Psychology, 15(2), 183–198.

- Yildirim, M., & Aziz, I. A. (2017). Psychometric properties of Turkish form of the fear of happiness scale. The Journal of Happiness & Well‐Being, 5(2), 187–195.

- Yildirim, M., Barmanpek, U., & Farag, A. A. (2018). Reliability and validity studies of externality of happiness scale among Turkish adults. European Scientific Journal, 14(14), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.19044/esj.2018.v14n14p1

- Yildirim, M., & Belen, H. (2018). Fear of happiness predicts subjective and psychological well‐being above the Behavioural inhibition system (BIS) and Behavioural activation system (BAS) model of personality. Journal of Positive Psychology and Wellbeing, 2(1), 92–111.

- Yildirim, M., & Belen, H. (2019). The role of resilience in the relationships between externality of happiness and subjective well‐being and flourishing: A structural equation model approach. Journal of Positive Psychology and Wellbeing, 3(1), 62–76.