Abstract

Objective

Literature illustrates that parenting entails positive and negative behaviour outcomes, personality development, subjective well‐being, performance, attitudes, and academic achievement of children. The study aimed to assess the direct and indirect impact of compassionate and supportive parenting style (i.e., positive parenting) on the academic achievement.

Method

The sample included 210 male and 292 female undergraduate university students. The age of the participants ranged between 22 and 24-year (M = 22.64, SD = .77). Perceived Dimensions of Parenting Scale, Rosenberg Self‐Esteem Scale, Procrastination Assessment Scale for Students, and Cumulative Grade Point Average were used as measures along with other demographic data. Path analysis through structural equation modelling via AMOS 21.0 was run to assess the mediational path model.

Results

The results indicated that 19% variance (R2 = .19) in academic achievement was accounted for by compassionate and supportive parenting style. In addition to direct impact = .27, the compassionate and supportive parenting style appeared to have a significant positive indirect impact = .08 on academic achievement via self‐esteem and academic procrastination.

Conclusion

The findings indicate that positive parenting has a significant impact on the self‐esteem of university students, and self‐esteem significantly mediates between positive parenting, academic procrastination and academic achievement.

What is already known

Positive parenting has a direct positive impact on self‐esteem of children between 5 and 15 year.

Positive parenting has a direct negative impact on procrastination behavior of children.

Positive parenting has a direct positive impact on academic achievement of children.

What this topic adds

Positive parenting indirectly influences academic procrastination behavior of children via enhancing their self‐esteem.

Positive parenting indirectly influences academic achievement behavior of children via enhancing their self‐esteem and lowering their academic procrastination behavior.

Self‐esteem does not carry the effect of positive parenting directly, but through dropping academic procrastination of young adults.

INTRODUCTION

The extent to which students achieve their educational goals is defined as an academic achievement, which is commonly measured by examinations or continuous assessment. Various studies have used GPA as a measure to assess academic achievement (Conard, Citation2006). The contemporary research designates academic achievement as complex scores clearly affected by several factors for example; parenting, personality traits and other personal factors like, self‐esteem (SE; Harackiewicz, Barron, Tauer, & Elliot, Citation2002), and motivational variables (Kuncel, Hezlett, & Ones, Citation2004) for instance, higher procrastination rates (Klassen et al., Citation2010). Empirical research has explored the relationship between parenting styles and the development of adolescents that includes self‐concept, academic motivation, academic procrastination, and academic achievement (Zakeri, Esfahani, & Razmjoee, Citation2013). Most of the studies have been carried out to assess the simple linear relationships of parenting styles with the personality attributes, behaviours, and motivation of children individually. The present study was designed to assess the direct and indirect (via SE and academic procrastination) impact of positive parenting (i.e., compassionate and supportive parenting style) on the academic achievement of university students.

The term parenting is generally defined as influence of parents on the behaviour and development of children. A parenting style is a psychological construct that represents standard strategies used by parents in rearing their children. Baumrind (Citation1991) identified three styles of parenting control, which included authoritarian, authoritative, and permissive domains; and were categorised with reference to dimensions of parental responsiveness and demandingness as positive and negative parenting styles. Parenting is a well‐recognised phenomenon and is discussed under various perspectives that entails positive and negative behaviour outcomes, personality development, subjective well‐being, performance, attitudes, and academic achievement of children. It is not surprising that the parenting styles have long‐term impacts on successes and failures of children. In an attempt to understand the critical role that parenting styles play, a large body of research on the correlates of parenting styles has been accumulating for the last four decades (e.g., Lamborn, Mounts, Steinberg, & Dornbusch as cited in Zakeri et al., Citation2013).

Effectiveness of parenting styles in the academic achievement at primary and higher education levels of students has been reported in research. Joshi, Ferris, Otto, and Regan (Citation2003) and Zahed, Rezaee, Yazdani, Bagheri, and Nabeiei (Citation2016) have reported significant inverse relationship between authoritarian parenting (negative parenting) and academic achievement in college students (also see Rahimpour, Direkvand‐Moghadam, Direkvand‐Moghadam, & Hashemian, Citation2015). However, Joshi et al. (Citation2003) differentiated parenting styles and their influence when coming from mothers and fathers, and concluded that maternal involvement and strictness positively associated with the GPA of college students compared to paternal influences. Khan, Tufail and Hussain (2014) conducted a study to demonstrate the impact of parenting styles and SE on academic achievement of postgraduate students in Pakistan. The study discovered that insignificant relationship existed between authoritative parenting style and academic achievement of students. Whereas, surprisingly and contrary to the studies published in the West, a significant positive relationship between authoritarian parenting style and academic achievement of students was found. Results further indicated that authoritarian style associated with high academic performance but low level of SE. On the other hand, authoritative parenting style associated with high SE but insignificant association with the academic performance. The data analysis also revealed that SE was not found to be a significant predictor of educational success and failure of the students. Another study that was conducted by Khan, Tufail, and Hussain (Citation2014) in Pakistan to see how parenting styles impact the academic achievements of postgraduate students found that those who grew up under authoritative parenting style had no significant relationship with academic performance. The literature indicates that the relationship between parenting styles and academic performance is not always a direct linear and simple one. Parenting styles have been reported to influence academic achievement indirectly via SE and procrastination in children (e.g., Pychyl, Coplan, & Reid, Citation2002).

SE reflects a person's overall emotional evaluation of his or her own worth, and is an evaluative dimension of the self that includes feelings of worthiness, pride and encouragement. Parents are the primary caregivers who exert significant impact on the self‐concept, SE, and growing abilities of their children. Authoritative parenting style (positive parenting) is positively associated with SE; whereas, negative correlation has been reported between authoritarian and neglectful parenting styles (negative parenting) and SE (e.g., Maziti, Citation2014). Adolescent sample, who perceived their parents as indulgent, scored higher on SE, and those who reported their parents as authoritarian obtained lower score on the SE (Martínez & García, Citation2007). A study conducted on Iranian children showed mother's authoritative parenting style as strong positive predictor of SE (Moghaddam, Validad, and Assareh (Citation2017)).

Previous literature related to parenting styles and SE states that these two variables have a significant relationship, but majority of the studies have been conducted in the Western culture that is different from collectivist culture. Studies conducted in the non‐Western cultures like, Arab and African societies show different results (Nketsia, Citation2013). Asian parents are more likely to adopt an authoritarian parenting style as they like to have greater control upon their children (Chang, Citation2007) For example, Pakistani culture gives emphasis to practice the values of obedience and respect, which is the underlying component of authoritarian parenting style (Huver, Otten, de Vries, & Engels, Citation2010) that is narrated as a negative parenting in the literature. Provided that authoritative (positive) parenting may not be appropriate in every culture (Bornstein & Bornstein, Citation2007), it is not essential that the authoritative style always positively associates with high SE levels (Garcia & Gracia, Citation2009). Moghaddam et al. (Citation2017) reported that the results of the group that consisted of collectivist parents (e.g., belonging to Pakistan) showed that even though majority of the parents practiced authoritarian parenting style, the SE of the children was still high. This finding highlights the importance of the influence of culture on the relationship between the parenting styles and SE. Hayee and Rizvi (Citation2017) in a study on Pakistani sample between 18 and 28-years of age found a nonsignificant relationship between SE of young adults and parenting styles followed by mother. On the other hand, the results indicate a significant negative correlation between SE and authoritative parenting style, and a significant positive correlation between SE and authoritarian parenting style practiced by the father.

An important body of contemporary research also documents an impact of parenting in the process of procrastination. Solomon and Rothblum (Citation1984) defined procrastination as the acts of unnecessarily delay. A common form of academic procrastination among students is to put off academic work and turn in papers or study for exams at the last moment. The demanding parents that generally suspect the abilities of their children to be successful in life induce procrastination behaviour in them. Parents' expectation and frequent condemnation and disapproval (negative parenting) are generally linked to a set of socially approved perfectionism that is associated with procrastination positively (Ferrari & Díaz‐Morales, Citation2007; Pylchyl et al., Citation2002). Zakeri et al. (Citation2013) examined the relationship between the parenting styles and academic procrastination in the students at Shiraz University in Iran. The results revealed that positive parenting, which involved “acceptance‐involvement” and “psychological autonomy‐granting” were significantly and negatively associated with academic procrastination; whereas, when parents used behavioural strictness‐supervision styles, academic procrastination significantly increased. Rosário, Costa, Núñez, González‐Pienda, and Valle (Citation2009) claimed that family plays a critical part in acquiring the positive and negative habits. As procrastination is a negative habit, parents are the most influential managers in inculcating it during developmental stages of a child (see also Scher & Ferrari, Citation2000). These researchers emphasise the role of parenting in procrastination and recommend to validate it across different cultural contexts.

As the mediating role of SE between parenting styles and various outcome behaviours concerns, the literature suggests that boosting SE through training and supportive environment, leads to many positive outcomes and benefits (Baumeister, Campbell, Krueger, & Vohs, Citation2003). Early studies in the 1990s indicate that parenting styles affect SE, which plays a significant role in the development of procrastination, for instance, extremely high parental expectations disapproval and condemnation that lowered SE of children, was positively associated with procrastination (Frost, Lahart, & Rosenblate, Citation1991). Pychyl et al. (Citation2002) provided an evidence that daughters, whose mothers instilled self‐worth in them, reported decreased procrastination behaviour, while fathers' parenting style appeared to have a direct effect on procrastination, even when self‐worth was controlled.

Given that parenting styles boost and lower SE in their children, the role of higher SE in improving academic performance via SE has long been established for example, Tafarodi and Swann (Citation1995) reported students who scored higher on SE were more confident, dynamic and motivated towards learning, actively participated in the learning process, and their performance was better in examination as compared to those students who scored lower on the SE. The low SE students were observed to remain unresponsive, inactive and unconcerned towards learning activities. Similarly, Leary and Downs (Citation1995) said that people who felt praiseworthy and competent were more likely to achieve their objectives than those who were feeling worthless, powerless, and incompetent. The proponents of this idea, advocate significant positive connection between SE and academic achievements (Ahmad, Zeb, Ullah, & Ali, Citation2013). Whereas, Pullmann and Allik (Citation2008) uphold the notion that low SE is not always an indication of a poor academic achievement.

On the other hand, the researchers have conditioned the relationship between SE and academic achievement with age. SE and academic achievement appear to be most strongly related between the years of around 7–15 (Hassan, Jami, & Aqeel, Citation2016). For example, Cvencek, Fryberg, Covarrubias, and Meltzoff (Citation2018) reported that children's actual achievement was more strongly and positively linked to SE in younger students among the preschoolers of age 5–10-years of age. Çelik, Çetin, and Tutkun (Citation2015) reported a non‐significant relationship between self‐liking component of SE and academic achievement even in a pre‐adolescent Turkish sample. While some researchers have suggested that educational success becomes less central to SE during late high school years and the years that follow (Bankston & Zhou, Citation2002). Therefore, target population for most of the previous studies was students between the age group of 5–16-years. A non‐significant direct relationship between SE and academic achievement also appeared in a study by Hassan et al. (Citation2016) in Pakistan with the students of 6th–10th grades, of the age ranged from 12 to 18-years regardless of their truancy/punctuality.

Keeping in view the inconsistent direct relationship of SE with academic achievement, the contemporary researchers are exploring the mediational role of SE in the relationship of different psychological attributes and academic achievement. For example, Yang, Tian, Huebner, and Zhu (Citation2019) examined the mediational role of SE in the relationship between academic achievement and subjective well‐being in school among the Chinese elementary school students and concluded that SE mediated the relationship between psychological wellbeing and academic achievement. Pychyl et al. (Citation2002) validated the mediational role of SE in the relationship between parenting styles and procrastination behaviour in the offspring. Academic procrastination has also been reported as a widely prevalent behaviour among students that damages their academic progress and bring about negative outcomes on SE (Schraw, Wadkins, & Olafson, Citation2007). Academic procrastination obstructs academic success, because it negatively affects the amount of learning and its quality, and increases the chance of low academic achievements (Howell & Watson, Citation2007).

As the role of gender in academic achievement concerns, female students were less likely to get low scores than male students on their academic assessments (Hyde & Kling, Citation2001; Marcenaro–Gutierrez, Lopez–Agudo, & Ropero–García, Citation2018). In fact, female students are reported to get better scores than male students globally for example, in UK (Younger, Warrington, & Williams, Citation1999) and in Turkey (Dayioglu & Turut‐Asik, 2007). However, some studies point out that male students do better on college entrance exams like SAT‐M (Young & Fisler, Citation2000).

CONCEPTUALIZATION OF THE STUDY

The review of relevant literature illustrates that academic achievement is affected by various factors like, parenting styles, SE, motivation (e.g., academic procrastination), and gender. Most of the studies report direct linear relationships of parenting styles, SE, procrastination, and gender with the academic achievement. Both direct and indirect links between parenting styles and academic achievement seem reasonable to be studied. Conceptually, a direct link between parenting styles and academic achievement would advocate that parents who practice supportive and compassionate parenting styles, induce confidence in their children to face academic challenges. Literature supports the direct major positive impact of supportive and compassionate parenting style on the academic achievement of children (e.g., Joshi et al., Citation2003; Zahed et al., Citation2016), development of children's personality traits for example, authoritative parents boost self‐concept, self‐efficacy, and SE (Baumrind, Citation1991; Lamborn et al., 1991; Martínez & García, Citation2007), decrease academic procrastination (Ferrari & Díaz‐Morales, Citation2007; Zakeri et al., Citation2013), which in turn could improve academic success (Ahmad et al., Citation2013; Howell & Watson, Citation2007). The inter‐relationships among all study variables support the notion that besides direct impact, supportive and compassionate parenting style may influence academic achievement indirectly via SE and procrastination behaviour of their children. The above mentioned studies, carried out in the Western and non‐Western contexts, illustrate that parenting styles have significant impact on the academic performance at both primary and higher education levels of students (Joshi et al., Citation2003; Rahimpour et al. (Citation2015); Zahed et al., Citation2016). Whereas, some of the studies conducted in Pakistan illustrate that authoritative parenting style has non‐significant direct relationship with academic achievement (Khan et al., Citation2014), so we may assume that the relationship between parenting styles and academic performance is not always a direct, linear and simple one. Parenting styles have been reported to influence academic achievement indirectly via some other variables for example, SE and procrastination in children (e.g., Pychyl, Coplan, & Reid, Citation2002). Moreover, after the notion raised by Pullmann and Allik (Citation2008) that low SE is not always an indication of a poor academic achievement, it has become obligatory to investigate the other psycho‐social factors that may carry the impact of SE to academic achievement, but little is known about how other related variables (e.g., academic procrastination) would mediate between the relationships of parenting styles and resultant SE with the academic achievement.

Give all that, in the current study, we proposed a mediational path model hypothesizing that compassionate and supportive parenting style (positive parenting) would have a direct positive impact on academic achievement of university students; and SE and procrastination would mediate, at least in part, in the relationship between compassionate and supportive parenting style and academic achievement of undergraduate university students.

OBJECTIVES

This study was planned to investigate the direct impact of compassionate and supportive parenting style on the academic achievement that is also mediated through SE and academic procrastination in undergraduate university students. The study also aimed at providing recommendations to parents, teachers, and academic counsellors to understand the multifaceted interaction of parenting styles, SE, and procrastination with academic achievement in male female students.

HYPOTHESES

H1

: Compassionate and supportive parenting style significantly correlates with self‐esteem, academic procrastination, and academic achievement of undergraduate university students.

H2

: Compassionate and supportive parenting style directly predicts self‐esteem, academic procrastination, and academic achievement of undergraduate university students.

H3

: Self‐esteem and academic procrastination mediate the relationship between compassionate and supportive parenting style and academic achievement of undergraduate university students by controlling gender.

METHODS

Sample

A convenient sampling technique was used to select the sample from the final semesters of BA/BSc honours of the social sciences (n = 243) and hard sciences (n = 259) departments of a public sector university in Lahore. The students from these last semesters were selected because we intended to get their final Cumulative Grade Point Average (CGPA) as a measure of their academic achievement. The sample included 210 male and 292 female undergraduate university students. The age range of the participants was between 22 and 24-years (M = 22.64, SD = .77). The reason behind involving university undergraduates in the current study was to see whether parenting styles have significant role in the personal attributes, behaviour, and academic performance even after adolescent period, because the span and role of parenting in Pakistan is different from that is in the West. Most of the studies in the West have been carried out on pre‐adolescent and adolescent samples. The reason might be the prevailing social set‐up in the West, in which the off‐spring usually start living independently, separate from their parents, once they are over 18-years of age. Contrarily, role of parenting in a country like Pakistan does not stop with the teen age. The offspring live with their parents even after 18-years, and parents use to direct and support them by realising them as their liability. Miles (Citation1992, p.245) states, “Pakistan sees little equivalent of the Western middle‐class aims to produce individuals who will increasingly exercise their own life choices and preferences as they become independent of their parents. … There are some distinctive aspects of Pakistani culture that do not appear to be shared in the Western culture”. Moreover, the approach of Pakistani researchers who included young adults to assess the impact of parenting on the personality and behaviour of their offspring supports the selection of the age sample for the current study (e.g., Ahmed & Bhutto, Citation2016; Hayee & Rizvi, Citation2017). Keeping in view the significance of parenting styles even after the age of 18-year, Stewart et al. (Citation1998) also studied functional parenting in Pakistan on the participants of age range from 17-years, 7 months to 26-years.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Mediums of instructions in many of the departments at the university were based in oriental languages (Urdu, Punjabi, Arabic, and so on), and students at these departments had difficulty in understanding English scales, thus these students were excluded from the study. Only students of departments, where medium of instructions was English, were included in the final sample.

Measures

Demographic data sheet

The demographic sheet collected information on age, gender, and study discipline of the participants.

Perceived dimensions of parenting scale (PDPS: Batool, Citation2016)

The PDPS is an indigenously developed valid and reliable tool for adolescents and young adults in Pakistan that measures positive and negative dimensions of parenting. The study intended to assess the perception of the offspring on the parenting styles that their parents had persistently been practicing since childhood, so it was an appropriate scale for the present study. In the present study, positive parenting was based on summated scores of two dimensions: compassionate and supportive parenting of PDPS (Batool, Citation2016). The PDPS is a 35‐item scale with each statement measured on a 5‐point Likert‐type scale (always = 5, often = 4, do not know = 3, sometimes = 2, never = 1). The scale contains five subscales (supportive, compassionate, controlling, aggressive, and orthodox/conventional parents). The first two subscales together constitute positive parenting and the last three subscales constitute as negative parenting. Only cumulative scores of two positive parenting styles (compassionate and supportive) with nine items in each subscales were used in the study. The supportive parents are those who boost children in their prospective plans and value their decisions, they empathise with children when they are in trouble, resolve mutual conflicts with children amicably, compliment them on their success, buck up children to resolve their academic and social issues. Compassionate parents are those who are friendly, involved, concerned, and kind. They prefer child' s likes and dislikes, give them constructive feedback, show positive attitude, understands children's problem from their perspectives, encourage and give space to the child to express his/her opinions, and resolve mutual conflict politely. The sample items are: (a) If I make a mistake, my parents softly explain it to me; (b) My parents guide me in my educational issues. The convergent validity of the scale was determined with Parenting Styles and Dimension Questionnaire (PSDQ) developed by Robinson et al. (1995), and the correlations were significant among subscales of both measures. The reported alpha coefficients on the subscales were supportive parents: α = .85, compassionate parents: α = .62, controlling parents: α = .80, aggressive parents: α = .74, and orthodox/conventional parents: α = .51 (Batool, Citation2016). Cronbach alpha for cumulative scores of compassionate and supportive parenting was .85 in the current study, and Cronbach alpha was low (.47) on the cumulative scores of last three subscales, so it was decided to use only positive parenting in the subsequent analysis. Higher cumulative scores on compassionate and supportive parenting styles indicate greater positive parenting in the study.

Rosenberg self‐esteem scale (RSES)

As we intended to assess the general SE of the study sample and the Rosenberg self‐esteem scale (RSES) is a well‐recognised measure to assess global SE, so it fulfils the demand of the present study (Rosenberg, Citation1965). Moreover, it has been reported as a valid and reliable tool for young adults in Pakistan in various earlier studies (e.g., Hayee & Rizvi, Citation2017; Khan et al., 2014) that supports the use of RSES for research in Pakistan.

The SE in the present study is the summated scores of the participants on the 10‐items RSES (Rosenberg, Citation1965). Higher scores indicate higher SE. The scale assesses the over‐all self‐worth by measuring both negative and positive approach to evaluate the self. The items of the scale are responded on a 4‐point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree = 3 to strongly disagree = 0. The score ranges from 0 to 30, with 30 indicating the highest score possible The scale has good psychometric properties (e.g., Ciarrochi, Heaven, & Davies, Citation2007). The alpha reliability for this current study was .81.

Procrastination assessment scale for students

Developed by Solomon and Rothblum (Citation1984). It has been cited as the most commonly used measure of academic procrastination (Ferrari, Johnson, & McCown, Citation1995; Harrington, Citation2005). As the study intended to assess how often students procrastinate on various academic tasks and procrastination assessment scale for students (PASS) served the purpose as it gives us the “frequency of procrastination”. Validity and reliability of the scale has been well established on university students (Yockey & Kralowec, Citation2015) that also supports the use of PASS in the current study. The PASS consists of 52 item scale. Response options range from never procrastinate = 1, to always procrastinate = 5. The scale was used by following the instructions provided by the authors. As per instructions provided by the authors of the PASS (Solomon & Rothblum, Citation1984), the first two scales related to frequency and problems with procrastination were computed. Two questions were asked in each area of procrastination (to what degree do you procrastinate on this task? To what degree is procrastination on this task a problem for you?). Each area contained three items. The scale is valid and reliable (Solomon & Rothblum, Citation1984). The Cronbach alpha in the current study was .78.

Academic achievement

It was assessed by students' final CGPA as suggested by (O'Donovan, Price, & Rust, Citation2008). Final CGPAs of students were obtained from the examination department of the university on the request of the author and with the students' consent.

Design

The study used a cross‐sectional correlational design and this analysis was extracted from the data that was published earlier (see Batool, Khursheed, & Jahangir, Citation2017), so sample characteristics and details on some measures, and procedures do overlap.

Procedure

After the approval from the “Advanced Studies and Research Board” of the university, we started data collection. Permission from the chairpersons of all the concerned departments was sought to collect data from the students in compulsory classes so that all the students of BSc (honours) final semester in the selected departments could be contacted in a single time point. Students were approached in their classes and the concerned teachers were requested to spare classes to complete a set of questionnaires. Students were briefed about the research. Some of the students in all classes who were absent on the day of data collection could not be included in the sample. It took 60-days to collect data from all the departments. No incentive was given to the students. Initially 555 students were approached and 502 sets of questionnaires were found to be suitable for data analysis.

RESULTS

Initially Pearson's correlation analysis was run to assess the inter‐correlations among the study. Later on, a mediational path analysis through structural equation modelling (SEM) was run by using AMOS 21.0 version.

Table shows significant correlations among all the study variables that support the linear relationships for further mediational path analysis (Baron & Kenny, Citation1986).

Table 1. Intercorrelations among study variables (N = 502)

Table shows that in the initial mediational path model, all the linear paths are significant at .001 level of significance, except for a path from SE to CGPA. In order to control the effect of gender, the gender was used as a covariate and it shows non‐significant path to CGPA.

Table 2. Linear paths between study variables in the initial model

Table shows the final model. All the linear paths are significant at .001, and .01 levels of significance. We added a path from SE to procrastination as it was suggested in the modification index, which is also supported in the literature. Gender was controlled in the model, and has no significant impact on CGPA.

Table 3. Linear relationships between study variables in Model 2

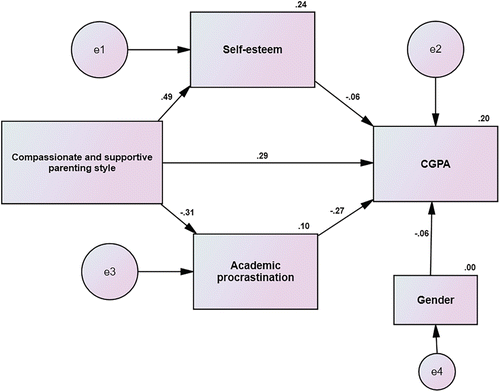

Figure 1 shows the paths of the proposed (hypothesized) mediational path model. The model shows direct significant paths from compassionate and supportive parenting style to SE, procrastination, and CGPA. However, a nonsignificant path appears from SE to CGPA that shows that SE does not carry the impact of compassionate and supportive parenting style to CGPA. The significant paths reflect that compassionate and supportive parenting style enhances SE and lowers the procrastination behaviour of university undergraduate students and procrastination determines the CGPA of the study participants. The compassionate and supportive parenting style also shows significant impact on CGPA in addition to an indirect significant impact through procrastination.

Figure 2 shows that compassionate and supportive parenting style has significant direct paths to SE, procrastination, and academic achievement. A path as suggested in the modification indices was added from SE to procrastination. The indirect path from compassionate and supportive parenting style to CGPA via SE and procrastination appears as significant. Results illustrate that procrastination mediates the relationship between compassionate and supportive parenting style and CGPA through SE. The figure shows that 19% variance in CGPA is accounted for by the direct and indirect (via SE and academic procrastination) impact of compassionate and supportive parenting style, by controlling gender.

Table shows that in the initial Model, Chi‐square value is significant and other fit indices (viz., RMR, CFI, and RMSEA) are not in the acceptable range, only the value of GFI is in acceptable range. The path from SE to academic achievement is non‐significant, so this path is desired to be removed from the model to uphold the parsimony of the Model. After removing the insignificant path and adding path from SE to procrastination in the final Model, Chi‐square (value = 1.625) becomes non‐significant at p = .804 with 4° of freedom, and all other model fit indices are in the acceptable ranges.

Table 4. Model fit indices for the models emerged from the data (N = 502)

Table shows three standardised direct and indirect effects: (a) the indirect (mediated) impact of compassionate and supportive parenting style on procrastination via SE is −.18, whereas, direct impact of compassionate and supportive parenting style on procrastination appears as −.14; (b) the indirect (mediated) impact of compassionate and supportive parenting style on CGPA is .08 via SE and procrastination. This is in addition to any direct impact that compassionate and supportive parenting style has on CGPA that is .27 in the current study; (c) the indirect (mediated) impact of SE on CGPA via procrastination is .09. There is zero direct impact of SE on CGPA in the current study.

Table 5. Decomposition of path analysis (standardised effect)

The Sobel test supports the significance of our path model (Z‐value = −5.41, SE = 0.02, p = .0000006). It shows that indirect effect of the IV (compassionate and supportive parenting style) on the DV (CGPA) via mediators (SE and academic procrastination) is significantly different from zero.

DISCUSSION

The study was carried out to test the hypothesized mediational path model that was based on the conclusion grounded in the accumulated researches that were conducted in different time points, in various parts of the world. Results showed significant correlations among study variables that supported our first hypothesis (see Table ). Whereas, the mediational analysis partially supported second and third hypotheses and the proposed model. The final model showed significant positive path from compassionate and supportive parenting style to SE (see Figure 2). Results are inconsistent with the study carried out on Pakistani sample by Hayee and Rizvi (Citation2017) that found a significant negative relationship between SE and authoritative parenting style (positive parenting) practiced by the fathers. We used the parenting styles scale that rated both parents collectively and it might be the reason of the results of current study are inconsistent with that of the study by Hayee and Rizvi (Citation2017). However, a significant positive path from parenting to SE is consistent with the studies conducted on the Western samples that authoritative parenting style (positive parenting) is positively associated with SE (e.g., Maziti, Citation2014; Moghaddam et al., Citation2017), and Martínez and García (Citation2007) that adolescent sample who perceived their parents as indulgent, scored higher on SE, and those who reported their parents as authoritarian obtained lower score on the SE. As we are living in the global world and the criteria of good and bad practices (including parenting) are being redefined, so we may conclude that parents' appreciation, compliments, love, compassion, empathy, mutual trust and support in day‐to‐day challenges of their off‐spring play positive role in enhancing their SE, no matter they are in the West or East. It suggests that the positive parenting enhances the SE of children. The SE appeared to partially mediate the relationship between compassionate and supportive parenting style and procrastination that reflects that compassionate and supportive parenting style also influences the procrastination behaviour of children indirectly (via SE) in addition to its direct impact on it. Parents who practice compassionate and supportive parenting style, guide their children in studies, share their problems, prefer children' s likes and dislikes, show positive and encouraging attitude, understand children's problem from their perspectives, resolve mutual conflict amicably, and give them constructive feedback. This all not only directly lowers the academic procrastination, it also enhances the SE of children that subsequently lowers procrastination of their academic assignments and achieve better grades in university academic assessment. The mediating role of SE between compassionate and supportive parenting style and procrastination is in line with (Pychyl et al., Citation2002; Steel, Citation2007). Researchers like, Flett, Hewitt, and Martin (Citation1995); Pychyl et al. (Citation2002); and Scher and Ferrari (Citation2000) also support the indirect association between parenting and procrastination, mediated through a third variable (e.g., self‐worth). The significant direct relationship between compassionate and supportive parenting style and academic procrastination coincides with Ferrari and Díaz‐Morales (Citation2007).

The significant path from SE to academic procrastination (see Figure 2) is in line with the empirical evidences on the significant relationships between self‐concept, self‐control and procrastination (Hen & Goroshit, Citation2014; Martínez & García, Citation2007; van Eerde, Citation2003). The researches carried out on procrastination in the university settings advocate that academic procrastination links to personality dispositions and motivational factors like; SE, perfectionism, and neuroticism (van Eerde, Citation2003). Procrastination is believed as a self‐protection of lower SE or failure at a task that becomes a sign of a lower SE and poorer self‐efficacy. Procrastination is considered as a self‐defensive approach that masks a fragile SE, and functions as an ego defensive mechanism and a protective device adopted by people with low SE (Steel, Citation2007).

The final model (see Figure 2) also suggests that compassionate and supportive parenting style has direct impact on the CGPA (academic achievement) of university students on one hand, and on the other hand, it has significant path to SE. However; SE did not appear to carry the impact of compassionate and supportive parenting style to CGPA directly, but it significantly carries the impact of compassionate and supportive parenting style to academic procrastination that subsequently carries the impact of compassionate and supportive parenting style and SE to CGPA. The age of the sample of the study might be the reason of this non‐significant direct relationship between SE and academic achievement, as the sample comprised university students and the researchers are in the view that SE most strongly related with academic achievement in pre‐adolescent and adolescent years (Cvencek, Fryberg, Covarrubias, & Meltzoff, Citation2018; Hassan et al., Citation2016). SE appeared less central to educational success even during late high school years and the years that follow (Bankston & Zhou, Citation2002). The non‐significant direct path from SE to academic achievement also validates the notion advocated by Pullmann and Allik (Citation2008) that low SE is not always an indication of a poor academic achievement.

The mediating role of SE in our path model is in line with various studies that indicate that SE mediates between different psychological attributes and procrastination (e.g., Batool et al., Citation2017; Hajloo, Citation2014), and the significant inverse relationship between procrastination and academic performance is in line with (Howell & Watson, Citation2007; Klassen et al., Citation2010; Schraw et al., Citation2007). Academic procrastination is assumed to be an obstacle to students' academic success because it drops the quality and quantity of learning and drops academic grades (Howell & Watson, Citation2007).

The significant direct path from compassionate and supportive parenting style to CGPA suggests that children, whose parents give constructive feedback, show positive attitude towards them, and support them in academic work; they achieve better grade points in the university. The results are in line with a study by Zahed et al. (Citation2016) that reveals significant negative relationship between authoritarian parenting styles and academic achievement of college students, and Rahimpour et al. (Citation2015) that demonstrates significant influence of the role parents in students' educational performance, and partly consistent with the study by Joshi et al. (Citation2003) that suggested mothers involvement and strictness linked to CGPA of college students. The significant direct and indirect path from compassionate and supportive parenting style to CGPA shows that parents who support their children in resolving their academic and general problems, it not only directly influences their academic achievement but also raises their SE and high SE links to lower procrastination behaviour that results in better academic achievement.

The impact of gender on CGPA was controlled in the mediation analysis. Gender appeared to have non‐significant impact on CGPA of university students, which is inconsistent with the previous studies that either reported female students to outperform male students (e.g., Dayioglu & Turut‐ Asik, Citation2007; Hyde & Kling, Citation2001; Marcenaro–Gutierrez et al., Citation2018) or vice versa (e.g., Young & Fisler, Citation2000). The reason might be the fact that data were collected from the same university, which is a high merit university, so due to similar academic facilities and high merit, difference in CGPA due to gender appeared as non‐significant.

Implications

The study has implications for counsellors, educational psychologists, and academicians that compassionate and supportive parenting style plays critical role in enhancing SE of the off‐spring that makes them confident to complete their academic assignments on time and secure good grades even in the young adulthood. While dealing with the academic issues of university students, the counsellors should work in collaboration with their parents, explore what kind of parenting strategies they are practicing, and also work on the SE of students. Based on the final results, we recommend parents to adopt the positive parenting styles while monitoring their children, as it appears to have long‐term impact on the SE, academic procrastination and academic achievement of their children even at higher education level.

LIMITATION AND SUGGESTIONS

The model emerged in the study needs to be further validated on different populations in relation to SE, and other possible predictors of academic achievement. We studied only one personal attribute (viz., SE) as a product of positive parenting that mediated between supportive and compassionate parenting style, and academic procrastination and academic achievement; whereas, the literature indicates that other personal attributes like, self‐regulation, perfectionism, and neuroticism (e.g., van Eerde, Citation2003) also have significant impact on procrastination. So these variables are recommended to be tested in future studies to see the relative strength of these variable in predicting academic procrastination and academic achievement. Although, this study included a recommended size of sample, but all the questionnaires were self‐reported measures (except CGPA that was obtained from the examination department of the university), so the social desirability factor cannot be ruled out. The sample was collected from one Public Sector University, which is a high merit university, so we should be cautious in generalising the results. The study followed cross‐sectional design, so the relationship may not be supposed as causational, for future studies, a longitudinal research is recommended to determine causes of low and high academic achievement. The model hypothesized in the present study was tested for the first time whereas, the parenting had separately been tested in association with SE, academic procrastination and academic achievement, so this path model needs to be replicated in future studies. We studied positive parenting styles, so in future, the impact of negative parenting styles should also be studied in relation to the mediators and outcome variables that emerged in the model.

CONCLUSIONS

The findings indicate that positive parenting style has a decisive impact on the SE of university students, and SE serves as a significant mediator between compassionate and supportive parenting style, academic procrastination and academic achievement. SE seems to function as an academic self‐regulatory mechanism that may help to decrease academic procrastination and enhance academic achievement. The final model disproves the claim of contemporary researchers (e.g., Ahmad et al., Citation2013) that the SE has significant direct impact on academic achievement. The results somehow indorse the findings of the studies by (e.g., Cvencek et al., Citation2018; Hassan et al., Citation2016) that SE and academic achievement are strongly related in younger students of 5–15-year of age, and validate the notion maintained by Pullmann and Allik (Citation2008) that low SE is not always an indication of a poor academic achievement.

However, the final model suggests that compassionate and supportive parenting style not only directly influences the academic achievement of university students but it also plays constructive role in their better grade via enhancing their SE and the subsequent delimited procrastination behaviour. If parents practice compassionate and supportive parenting style in monitoring the behaviour of children, it will entail multiple positive outcomes for their children: elevated SE of their children, which will curb the procrastination behaviour and will result in better academic grades. Repeated academic procrastination negatively affects academic achievement of children and drops their grades that often brings annoyance of parents, they reprimand their children that further lowers their SE and this vicious cycle never stops, so the parents are recommended to develop and practice positive parenting styles.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There is no conflict of interest.

ETHICAL STATEMENT

The study was approved by the Advanced Study and Research Board of Government College University, Lahore (Pakistan). Permission to collect data was taken from the University administration, Chairmen, and Directors of various departments and informed consent was taken from the participants of the study. No incentive was given to the participants.

REFERENCES

- Ahmad, I., Zeb, A., Ullah, S., & Ali, A. (2013). Relationship between self‐esteem and academic achievements of students: A case of government secondary schools in district Swabi, KPK, Pakistan. International Journal of Social Sciences and Education, 3(2), 361–369.

- Ahmed, N., & Bhutto, Z. H. (2016). Relationship between parenting styles and self‐compassion in young adults. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 31(2), 441–445.

- Bankston, C. L., & Zhou, M. (2002). Being well vs. doing well: Self‐esteem and school performance among immigrant and nonimmigrant racial and ethnic groups. The International Migration Review, 36(2), 389–415.

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator‐mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

- Batool, S. S. (2016). Construction and validation of perceived dimensions of parenting scale (PDPS). Pakistan Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 14(2), 15–25.

- Batool, S. S., Khursheed, S., & Jahangir, H. (2017). Academic procrastination as a product of low self‐esteem: A mediational role of academic self‐efficacy. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 32(1), 195–211.

- Baumeister, R. F., Campbell, J. D., Krueger, J. I., & Vohs, K. D.(2003). Does high self‐esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4(1), 1–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/1529-1006.01431

- Baumrind, D. (1991). Effective parenting during the early adolescent transition. In P. A. Cowan & E. Hetherington (Eds.), Advances in family research (Vol. 2, pp. 111–163). Hills Dale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238–246.

- Bornstein, L., &Bornstein, M. H. (2007). Parenting styles and child social development. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi:10.1.1.528.635&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Çelik, D. A., Çetin, F., & Tutkun, E. (2015). The role of proximal and distal resilience factors and locus of control in understanding hope, self‐esteem and academic achievement among Turkish preadolescents. Current Psychology, 34(2), 321–345 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-014-9260-3

- Chang, M. (2007). Cultural differences in parenting styles and their effects on teens' self‐esteem, perceived parental relationship satisfaction, and self‐satisfaction. Carnegie Mellon University. Retrieved from http://repository.cmu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1084&content=hsshonors

- Ciarrochi, J., Heaven, P. C., & Davies, F. (2007). The impact of hope, self‐esteem, and attribution style on adolescents' school grades and emotional well‐being: A longitudinal study. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(6), 1161–1178.

- Conard, M. A. (2006). Aptitude is not enough: How personality and behavior predict academic performance. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(3), 339–346.

- Cvencek, D., Fryberg, S. A., Covarrubias, R., & Meltzoff, A. N. (2018). Self‐concepts, self‐esteem, and academic achievement of minority and majority north American elementary school children. Child Development, 89(4), 1099–1109. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12802

- Dayioglu, M., & Turut‐ asik, S. (2007). Gender differences in academic performance in a large public university in Turkey. Higher Education, 53(2), 255–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-0052464-6

- Ferrari, J. R., & Díaz‐morales, J. F. (2007). Perceptions of self‐concept and self‐presentation by procrastinators: Further evidence. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 10(1), 91–96.

- Ferrari, J. R., Johnson, J. L., & Mccown, W. G. (1995). Procrastination and task avoidance: Theory, research and treatment. New York, NY: Plenum Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-14899-0227-6_2

- Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., & Martin, T. R. (1995). Dimensions of perfectionism and procrastination. In J. R. Ferrari, J. L. Johnson, & W. G. Mccown (Eds.), Procrastination and task avoidance: Theory, research and treatment (pp. 113–136). New York, NY: Plenum Press.

- Frost, R. O., Lahart, C. M., & Rosenblate, R. (1991). The development of perfectionism: A study of daughters and their parents. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 15, 469–490.

- Garcia, F., & Gracia, E. (2009). Is always authoritative the optimum parenting style? Evidence from Spanish families. Adolesence, 44(173), 101–131 Retrieved from http://www.uv.es/garpe/C_/A_/C_A_0037.pdf

- Hajloo, N. (2014). Relationships between self‐efficacy, self‐esteem and procrastination in undergraduate psychology students. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 8(3), 42–49.

- Harackiewicz, J. M., Barron, K. E., Tauer, J. M., & Elliot, A. J. (2002). Predicting success in college: A longitudinal study of achievement goals and ability measures as predictors of interest and performance from freshman year through graduation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(3), 562–575.

- Harrington, N. (2005). It's too difficult! Frustration intolerance beliefs and procrastination. Personality and Individual Differences, 39, 873–883. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.12.018

- Hassan, A., Jami, H., & Aqeel, M. (2016). Academic self‐concept, self‐esteem, and academic achievement among truant and punctual students. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 31(1), 223–240.

- Hayee, A. A., & Rizvi, Z. (2017). Perceived parental authority and self‐esteem among young adults. Paper presented in 8th The International Conference on Education and Educational Psychology. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320430557_Perceived_Parental_Authority_And_Self‐Esteem_Among_Young_Adu

- Hen, M., & Goroshit, M. (2014). Academic self‐efficacy, emotional intelligence, GPA and academic procrastination in higher education. Eurasian Journal of Social Sciences, 2(1), 1–10.

- Howell, A. J., & Watson, D. C. (2007). Procrastination: Associations with achievement goal orientation and learning strategies. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(1), 167–178.

- Huver, R. M., Otten, R., de Vries, H., & Engels, R. C. (2010). Personality and parenting style in parents of adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 10, 395–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.07.012

- Hyde, J. S., & Kling, K. C. (2001). Women, motivation and achievement. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 25, 364–378.

- Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1984). LISREL‐VI user's guide (3rd ed.). Mooresville, IN: Scientific Software.

- Joshi, A., Ferris, J. C., Otto, A. L., & Regan, P. C. (2003). Parenting styles and academic achievement in college student. Psychological Reports, 93(3), 823–828.

- Khan, A. A., Tufail, M. W., & Hussain, I. (2014). A study on the impact of parenting styles and self‐esteem on academic achievement of post‐graduate students. The Sindh University Journal of Education, 43, 96–112 Retrieved from: sujo.usindh.edu.pk/index.php/SUJE/article/download/1971/1758

- Klassen, R. M., Ang, R. P., Chong, W. H., Krawchuk, L. L., Huan, V. S., Wong, I. Y. F., & Yeo, L. S. (2010). Academic procrastination in two settings: Motivation correlates, behavioral patterns, and negative impact of procrastination in Canada and Singapore. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 59(3), 361–379.

- Kuncel, N. R., Hezlett, S. A., & Ones, D. S. (2004). Academic performance, career potential, creativity, and job performance: Can one construct predict them all? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(1), 148–161.

- Leary, M. R., & Downs, D. L. (1995). Interpersonal functions of the self‐esteem motive: The self‐esteem system as a sociometer. In M. H. Kernis (Ed.), Efficacy, agency, and self‐esteem (pp. 123–144). New York, NY: Plenum Press.

- Marcenaro–gutierrez, O., Lopez–agudo, L. A., & Ropero–garcía, M. A. (2018). Gender differences in adolescents' academic achievement. https://doi.org/10.1177/1103308817715163

- Martínez, I., & García, J. F. (2007). Impact of parenting styles on adolescents' self‐esteem and internalization of values in Spain. Spanish Journal of Psychology, 10(2), 338–348.

- Maziti, E. (2014). The relationship between parenting styles and self‐esteem among adolescents: A case of Zimunya high school (Manicaland). Asian Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities, 4(2), 27–41.

- Miles, M. (1992). Concepts of mental retardation in Pakistan: Toward cross‐cultural and historical perspectives. Disability, Handicap and Society, 7, 235–255.

- Moghaddam, M. F., Validad, A., Rakhshani, T., & Assareh, M. (2017). Child self‐esteem and different parenting styles of mothers: A cross‐sectional study. Archives of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 1, 37–42 Retrieved from http://www.archivespp.pl/uploads/images/2017_19_1/37Moghaddam_Archives_PP_1_2017.pdf

- Nketsia, J. E. (2013). Influence of parental styles on adolescents self‐esteem. Retrieved from: https://www.academia.edu/5105903/The_Influence_of_parental_style_on _ Adolescents_self_esteem

- O'donovan, B., Price, M., & Rust, C. (2008). Developing student understanding of assessment standards: A nested hierarchy of approaches. Teaching in Higher Education, 13, 205–217.

- Pullmann, H., & Allik, J. (2008). Relations of academic and general self‐esteem to school achievement. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(6), 559–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.06.017

- Pychyl, T. A., Coplan, R. J., & Reid, P. A. M. (2002). Parenting and procrastination: gender differences in the relations between procrastination, parenting style and self‐worth in early adolescence. Personality and Individual Differences, 33, 271–285.

- Rahimpour, P., Direkvand‐moghadam, A., Direkvand‐moghadam, A., &. Hashemian, A. (2015). Relationship between the parenting styles and students' educational performance among Iranian girl high school students, a cross‐ sectional study. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, 9(12), JC05‐7. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2015/15981.6914.

- Rosário, P., Costa, M., Núñez, J. S., González‐pienda, J., Solano, P., & Valle, A. (2009). Academic procrastination: Associations with personal, school, and family variables. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 12(1), 18–127.

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self‐image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Scher, S., & Ferrari, J. (2000). The recall of completed and noncompleted tasks through daily logs to measure procrastination. Journal of Social Behaviour and Personality, 15, 255–265.

- Schraw, G., Wadkins, T., & Olafson, L. (2007). Doing the things we do: A grounded theory of academic procrastination. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(1), 12–25.

- Solomon, L. J., & Rothblum, E. D. (1984). Procrastination assessment scale for students (PASS). In J. Fischer & K. Corcoran (Eds.), Measures for clinical practice (pp. 446–452). New York: The Free Press.

- Steel, P. (2007). The nature of procrastination: A meta‐analytic and theoretical review of quintessential self‐regulatory failure. Psychological Bulletin, 133, 65–94.

- Stewart, S. M., Rao, N., Bond, M. H., Mcbride‐chang, C., Fielding, R., & Kennard, B. (1998). Chinese dimensions of parenting: Broadening Western predictors and outcomes. International Journal of Psychology, 33(5), 345–358.

- Tafarodi, R. W., & Swann, W. B. (1995). Two‐dimensional self‐esteem and reactions to success and failure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 65(2), 324–325.

- van Eerde, W. (2003). A meta‐analytically derived nomological network of procrastination. Personality and Individual Differences, 35(6), 1401–1418.

- Yang, Q., Tian, L., Huebner, E. S., & Zhu, X. (2019). Relations among academic achievement, self‐esteem, and subjective well‐being in school among elementary school students: A longitudinal mediation model. School Psychology, 34(3), 328–340. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000292

- Yockey, R. D., & Kralowec, C. J. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis of the procrastination assessment scale for students. SAGE Open, 5, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015611456

- Young, J. W., & Fisler, J. L. (2000). Sex differences on the SAT: An analysis of demographic and educational variables. Research in Higher Education, 41, 401–416.

- Younger, M., Warrington, M., & Williams, J. (1999). The gender gap and classroom interactions: Reality and rhetoric? British Journal of Sociology of Education, 20, 325–341A.

- Zahed, Z. Z., Rezaee, R., Yazdani, Z., Bagheri, S., & Nabeiei, P. (2016). The influence of parenting style on academic achievement and career path. Journal of Advances in Medical Education & Professionalism, 4(3), 130–134.

- Zakeri, H., Esfahani, B. N., & Razmjoee, M. (2013). Parenting styles and academic procrastination. Procedia ‐ Social and Behavioral Sciences, 84, 57–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.509