Abstract

Objective: The aim of the study was to explore the possible indirect effect of subjective career success on the relationship between work–family enrichment and job satisfaction and work–family enrichment and work engagement. Method: A cross‐sectional, quantitative research design approach was followed using a convenience sample (N = 334). Results: Results revealed that work–family enrichment was not only positively related to subjective career success, job satisfaction and work engagement, but also predictive of the mentioned constructs. Furthermore, subjective career success was found to indirectly effect the relationship between work–family enrichment and job satisfaction and work engagement. Conclusion: Using the resource‐gain‐development framework, new insights are provided into the processes and mechanisms relating to work–family enrichment. Our findings suggest that resources are creating positive affect in not only the work and career domains of employees, but also leading to more engaged and satisfied employees. (i.e., the indirect effect of subjective career success). Organisations can benefit when they enhance work environments (e.g., by providing relevant resources) to promote work–family enrichment and, by implication, subjective career success and positive work outcomes such as job satisfaction and work engagement.

Funding information National Research Foundation, Grant/Award Number: TTK14051567368

What is already known about this topic

The positive interplay between work and family, (i.e., work–family enrichment) are related to various affective, resource and performance consequences as well as general wellbeing outcomes (e.g., job satisfaction and work engagement).

Subjective career success predicts wellbeing outcomes such as happiness, performance, and engagement.

Growing interest is shown in the increasingly important connection between the work–family interface and career success (i.e., exploring career success from a work–home perspective).

What this topic adds

Work–family enrichment predicts subjective career success.

Using the resource‐gain‐development framework, this study expands the existing theoretical understandings of the enrichment‐satisfaction and engagement relationship.

Work–family enrichment leads to job satisfaction and work engagement through the indirect effect of subjective career success.

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, there has been growing interest in how individuals adapt to the changing demands of both their careers and personal lives in order to lead sustainably successful lives. Given the high importance that people and organisations attach to professional success, numerous scholars have done research on this topic, as is evidenced by existing career literature (McDonald & Hite, Citation2008; Ng & Feldman, Citation2014). Career scholars agree that the attainment of career success is meaningfully related to various positive work outcomes (e.g., job satisfaction and work engagement). Antecedents of career success that the literature distinguishes between are individual, structural and behavioural antecedents (Judge, Cable, Boudreau, & Bretz, Citation1995). However, few researchers have focused on family‐related factors (e.g., work–family conflict, satisfaction with a work–family situation, and work–life balance) as predictors of career success (Amin, Arshad, & Ghani, Citation2017). According to Amin et al. (Citation2017), employees will have positive work experiences and a psychological bond with their career if their perception is that their job enables them to balance their work and family roles. Viewed from a work–home perspective, the concept of career success is significant because individuals' appraisal of their success is likely to have an effect on their sense of well‐being (Greenhaus & Kossek, Citation2014). The reason for this is that, in modern times, career and home experiences are inextricably intertwined mainly because of the changed nature of careers.

With the aim of exploring careers from a work–home perspective, recent studies have focused on the relations between non‐work orientations and career satisfaction (Hirschi, Herrmann, Nagy, & Spurk, Citation2016), work–home balance and career decision‐making (De Hauw & Greenhaus, Citation2015), and work–family interface and career success. Growing interest in considering the role of positive psychology (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2006) has led to work–family scholars' belief that individuals can benefit from being simultaneously engaged in multiple work and family roles (a process known as work–family enrichment [WFE]). Researchers who view work experiences from a positive psychology perspective have found that both WFE and subjective career success lead to positive work‐related outcomes such as job satisfaction (Daniel & Sonnentag, Citation2016) and work engagement (Hakanen, Peeters, & Perhoniemi, Citation2011).

However, exploring the interface between work and family from an enrichment perspective (i.e., WFE) as well as the impact this interface has on individuals' career success has received scant attention. Therefore, the purpose of our study is to examine the interrelationship between work and family (from a WFE perspective), perceived career success, job satisfaction and work engagement (as affective and resource consequences). In examining these relationships, we view career success as a driver of job satisfaction and work engagement, and WFE as an antecedent of career success. Building on the resource‐gain‐development (RGD) perspective of enrichment, we aim to contribute to both career and work–family literature by expanding existing theoretical understandings of the relationship between enrichment‐satisfaction and engagement.

LITERATURE

Perceived career success

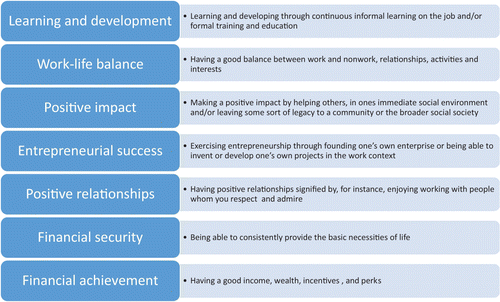

Career success has been defined as the “accomplishment of desirable work‐related outcomes at any point in a person's work experiences over time” (Arthur, Khapova, & Wilderom, Citation2005, p. 179). The literature distinguishes between objective and subjective career success and explains that these two constructs are empirically distinct but related (Ng, Eby, Sorensen, & Feldman, Citation2005). A recent perspective on subjective career success is that it is multidimensional (Shockley, Ureksoy, Rodopman, Poteat, & Dullaghan, Citation2016). In line with this perspective, Mayrhofer et al. (Citation2016) provide a comprehensive view of perceived career success, positing that it comprises four overarching themes (i.e., material concerns, learning, social relations, and pursuing of own projects) and seven meanings (i.e., learning and development, work–life balance, positive impact, entrepreneurial success, positive relationships, financial security, and financial achievement) that apply globally (see Figure 1). According to Akkermans and Kubasch (Citation2017), these recent notions of career success have not yet gained real momentum, but testing them empirically may be particularly valuable in enhancing an understanding of the phenomenon.

Figure 1 Meanings of perceived career success. Source: Mayrhofer et al. (Citation2016)

Several contemporary career scholars have recognised work–home balance as a key motivator of career transitions aimed at maintaining career sustainability (Beigi, Wang, & Arthur, Citation2017; De Hauw & Greenhaus, Citation2015; Greenhaus & Kossek, Citation2014). This notion may suggest that individuals will perceive their careers as successful if they succeed in fitting their career into a personal and family life that they find satisfying, in that way achieving a balance between work and home.

Work–family enrichment

Work–family scholars have adopted a number of theoretical approaches to explain the positive interface between work and family, for example the theory of role accumulation (Sieber, Citation1974), the resource‐gain‐development perspective (Wayne, Grzywacz, Carlson, & Kacmar, Citation2007), and the work–home resources model (Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, Citation2012). A prominent model that has been used is the work–family enrichment model of Greenhaus and Powell (Citation2006). Work–family enrichment (WFE) is defined as a process whereby the resources gained in one role (e.g., work) positively influence the performance in another role (e.g., family) or vice versa (Greenhaus & Powell, Citation2006). This process is also described as the instrumental path of enrichment. Alternatively, WFE can be experienced via an affective path, that is, a positive effect generated in one role leads to an improvement of performance in the same role, while also enhancing a positive affect and performance in the other role. This suggests that the resources acquired in one role can enrich the other role through instrumental and/or affective paths, which in turn can lead to more positive attitudes and affective outcomes (i.e., job satisfaction). Thus, the resources can either directly affect performance in the second role or cause a positive affect that leads to heightened performance in the second role. The WFE concept recognises the positive interdependence between work and family roles where resources are not fixed but may be re‐invested in multiple domains (Greenhaus & Allen, Citation2011).

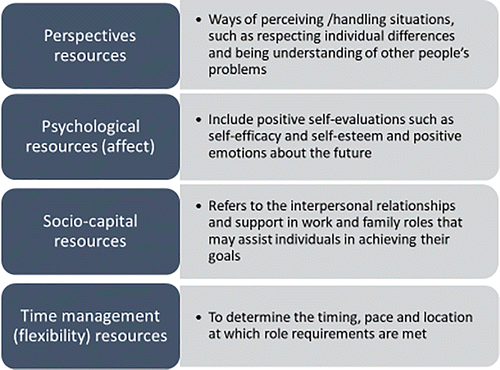

According to Greenhaus and Powell (Citation2006), a resource is an asset that may be drawn on when needed to solve a problem or cope with a challenging situation. De Klerk, Nel, Hill, and Koekemoer (Citation2013) insist that enrichment, because it focuses on the individual and the resources that assist in improving work and family life, entails more than improving role performance in individual lives. In their conceptualisation, WFE refers to “the extent to which various resources from work and family roles have the capacity to encourage an individual and to provide positive experiences, and thereby enhance that individual's quality of life in the other role (i.e., performance and positive affect)” (De Klerk et al., Citation2013, p. 4). Based on the WFE model of Greenhaus and Powell (Citation2006), De Klerk et al. (Citation2013) have validated a work–family enrichment instrument that describes the different resources that may lead to enhanced functioning. Figure 2 presents descriptions of these resources.

Figure 2 Resources of WFE. Source: De Klerk et al. (Citation2013)

Work–family enrichment, job satisfaction, and work engagement

Zhang, Xu, Jin, and Ford (Citation2018) have conducted a thorough meta‐analyses of the consequences of affective, resource, and performance consequences on WFE as well as on general well‐being. The literature also documents positive relationships between WFE and job satisfaction (Chung, Kamri, & Mathew, Citation2018; Daniel & Sonnentag, Citation2016; Shockley & Singla, Citation2011) and work engagement (Moazami‐Goodarzi, Nurmi, Mauno, & Rantanen, Citation2015; Qing & Zhou, Citation2017; Timms et al., Citation2015). De Klerk, Nel, and Koekemoer (Citation2015) explain the relationship between WFE and job satisfaction clearly; they suggest that the enrichment experience gives employees a sense of autonomy or assists them to develop new skills. This could enhance their ability to perform more effectively, resulting in the experience of job satisfaction. When work resources are provided, employees are able to be more productive and perform tasks more effectively and accurately (Hanson, Hammer, & Colton, Citation2006). Friedman and Greenhaus (Citation2000) add that employees who are given work resources can be motivated and energised to perform better, which in turn fosters a sense of job and career satisfaction and ultimately promotes subjective career success.

Likewise, Hakanen et al. (Citation2011) posit that the resources provided will enhance not only WFE but also work engagement. It is further argued that work engagement, which is “a positive, fulfilling, work‐related state of mind that is characterised by vigour, dedication, and absorption” (Schaufeli, Salanova, González‐Romá, & Bakker, Citation2002, p. 74), is enhanced by WFE because individuals who experience WFE will feel positive about their work and will demonstrate this by investing more energy in their work and showing greater vigour in performing their tasks (Qing & Zhou, Citation2017; Timms et al., Citation2015).

Theoretical framework and hypotheses

Evidence exists of the direct effects of WFE on outcomes such as job satisfaction and work engagement; however, the current study aims to show that the existing theoretical understanding of the enrichment‐satisfaction and engagement relationship can be expanded by making use of the resource‐gain‐development (RGD) framework (Wayne et al., Citation2007). According to the RGD framework, individuals will always strive to grow, develop, and achieve in the domains in which they participate, and as a result will actively seek resources in these domains that will enable them to grow and develop. This suggests that the resources that individuals gain in their work–family lives are of significance to their career growth and development. Therefore, as scholars have emphasised, it is important to gain a better understanding of how individuals experience the interplay between their work and family roles while managing their careers (to achieve career success), and of how their experiences affect their well‐being in a work context (i.e., job satisfaction and work engagement).

Individuals who experience WFE feel they have control over their family and work lives. This feeling contributes to increased self‐esteem (Aryee, Srinivas, & Tan, Citation2005) and a sense of accomplishment and satisfaction, which in turn contribute to an experience of subjective career success (Judge, Cable, Boudreau, & Bretz Jr, Citation1995). The literature indicates that the resources that employees receive who do experience WFE enable them not only to do their jobs more effectively but also to flourish in and be more satisfied with their careers (Amin et al., Citation2017; Hirschi et al., Citation2016). Therefore, resources can promote employees' motivation and energy, foster their job and career satisfaction, and ultimately promote their experience of subjective career success. De Hauw and Greenhaus (Citation2015) further argue that employees who maintain a well‐balanced work–home life experience high levels of comfort and satisfaction and are therefore more inclined to engage in career decisions aimed at career development. In terms of the RGD framework, employees' decisions to develop their careers (i.e., pursue career success) are triggered by the promise of gaining valuable job resources that are known to stimulate personal growth and development. Hall, Lee, Kossek, and Heras (Citation2012) further indicate that individuals who experience high subjective success tend to be more self‐directed and driven by their personal values. They argue that these individuals are able to craft their work–home situation (e.g., restructure their work arrangements) to such an extent that it supports their perceived career success. Thus, according to the RGD framework, these individuals seek resources (e.g., the use of various work arrangements) to promote growth and development not only in their work–family situation (so as to experience WFE) but also in their career domain (so as to experience career success). This notion resonates with the view of Amin et al. (Citation2017) that individuals' positive work–home experiences, in other words their experience of WFE (in terms of emotions, attitudes, skills, and behaviours), will be carried over to their career lives and thus influence their perception of career success.

According to Ng, Eby, Sorensen, and Feldman (Citation2005), employees who achieve work‐related goals are full of energy, and those who are devoted to continuous self‐development distinguish themselves from other employees (because they achieve more success). Coetzee, Bergh, and Schreuder (Citation2010), Karsan (Citation2011) and Smith, Caputi, and Crittenden (Citation2012) have found that employees who experience subjective career success not only feel that they belong in their organisation but they also love their jobs. As a result these employees invest time and energy in their jobs and are dedicated to and engaged in their jobs (Karsan, Citation2011). According to research, the experience of subjective career success positively influences employees' work engagement. In addition, Siu et al. (Citation2010) explain that engaged employees in a sense identify with their work; they regard their work as meaningful and significant and they enjoy being challenged as they believe in growth and learning.

The literature reports that outcomes associated with subjective career success comprise individual outcomes in the form of positive relationships with well‐being constructs (e.g., happiness, performance, life satisfaction, heightened self‐esteem) and organisational outcomes (e.g., increased performance, organisational success, organisational commitment, employee's intention to remain within an organisation and sustainable employment) (Pan & Zhou, Citation2015; Simo, Enache, Leyes, & Alarcon, Citation2010; Smith et al., Citation2012). As pointed out earlier, there seems to be consensus in the literature that the resources that employees receive who do experience WFE enable them not only to do their jobs more effectively but also to flourish and be more satisfied with their careers (Amin et al., Citation2017; Hirschi et al., Citation2016).

Using the RGD framework, our argument is that the resources that employees have at their disposal in their work and family interactions can enhance their sense of WFE and their perception of their careers, and as a consequence their work engagement and satisfaction deepen.

The aim of this study is to explore how WFE affects work satisfaction and engagement. Considering the preceding literature review we believe that we can achieve this aim by using a mediation model that involves subjective career success.

For this study, we set the following hypotheses:

H1: Work–family enrichment has an indirect effect on job satisfaction through subjective career success.

H2: Work–family enrichment has an indirect effect on work engagement through subjective career success.

METHOD

Design

The study utilised a cross‐sectional, electronic, survey‐based research design.

Respondents

The minimum criteria for participation were that a participant had to be a South African employee who had been working for at least 5-years in a full‐time capacity. Guided by career success literature (Ng et al., Citation2005), it was decided to include work experience as a minimum requirement. A sample size of 334 employees was obtained. Of these, 50.6% were females, the majority (65.6%) were Afrikaans speaking and married (64.7%) and 37.4% had no children at the time of data collection. Almost a fourth of the sample (25.4%) had been working in their current organisation for about four to 6-years. Participants were employed mainly at operational or junior levels (36.6%) or in middle management (28.4%). Employees were well educated, possessing either a degree (21%) or a postgraduate qualification (31.4%).

Measures

WFE was measured with the MACE instrument (De Klerk et al., Citation2013). Although bi‐directional in nature, only the 18 items measuring work‐to‐family enrichment comprising four dimensions were utilised: work–family perspectives (six items), work–family affect (three items), work–family time management (six items) and work–family social capital (three items). An example item reads as follows: “My family life is improved by my work showing me different viewpoints” (perspective dimension). A 5‐point Likert‐type rating scale was used (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Within this sample, high internal consistency values for both the overall scale (Composite reliability: 0.91) and sub‐dimensions (ranging from 0.77 to 0.92) were found. Previous studies reported acceptable Cronbach's alpha reliability values (Koekemoer, Strasheim, & Cross, Citation2017).

SCS was measured using items that represent select measures from a copyrighted scale that measures career success (Briscoe, Kase, Dries, Dysvik, & Unite, Citation2019) developed by the 5C Group (https://5c.careers/), that we received permission to use. Based on Mayrhofer et al. (Citation2016) perceived career success comprises of seven dimensions (learning and development (four items), positive impact (three items), financial security (three items), financial achievement (three items), work–life balance (three items), positive relationships (four items) and entrepreneurship (three items), which are measured by 23 items utilising a 5‐pointLikert‐type rating scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The instrument measures both the importance (“Thinking of my career success, I consider this career aspect…”) and level of achievement (“In regard to this career aspect, I have achieved a level I am happy with…”) for each dimension. However, for the purpose of this study only the level of achievement was measured. In this study, the overall scale (Composite reliability: 0.96) as well as its sub‐dimensions (ranging from 0.69 to 0.91) showed acceptable levels of internal consistency. Koekemoer and Olckers (Citation2019) reported composite reliabilities ranging between 0.78 and 0.91 for the sub‐dimensions.

Job satisfaction was measured using the three‐item 5‐point Likert‐type (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly job satisfaction rating scale developed by Hellgren, Sjöberg, and Sverke (Citation1997). In this study, a composite reliability value of 0.88 was found for this particular scale. An example item includes: “I enjoy being at my job”. A Cronbach's alpha value of 0.88 was reported by De Klerk et al. (Citation2015).

Work Engagement was measured using the 9‐item Utrecht work engagement scale comprising three dimensions (vigour, dedication, and absorption), using a 7‐point Likert‐type rating scale ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (always) (Schaufeli & Bakker, Citation2003). Example items include:”At my job, I feel strong and vigorous” and “I feel happy when I am working intensely”. The composite reliability for this scale, in this study was 0.93. van Zyl, van Oort, Rispens, and Olckers (Citation2019) reported a Cronbach's alpha value of 0.98 for the overall scale with the subscales ranging from 0.89 to 0.92.

Procedure and analyses

An anonymous web‐based survey was used to administer all instruments. An introductory e‐mail to participants explained the purpose of the study and assured them of anonymity and confidentiality. Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the involved institution of the researchers.

During the analyses SPSS v25 and MPlus v7.4 were used to process the data. To assess the model fit for both the competing measurement models and the final structural model, structural equation modelling with the maximum likelihood estimator was employed. The fit indices and associated cut‐offs recommended by Wang and Wang (Citation2012) to determine model fit was used: (1) absolute fit indices (Chi‐square, RMSEA: <0.08 and SRMR: <0.08), (2) incremental fit indices (e.g., TLI: >0.90, CFI: >0.90) and (3) comparative fit indices (AIC and BIC).

After refining the best‐fitting measurement model, we analysed descriptive statistics. Composite reliability, a more “accurate” estimation of internal consistency than Cronbach's alpha, was used to compute scale reliability (Raykov, Citation2009). Values above 0.70 indicate good reliability. Pearson correlation coefficients (p ≤ .01) were used to estimate the relationships among the various constructs. Harman's single factor test as well as a series of common latent factor methods were employed to detect the presence of common method bias (CMB) (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Citation2003; Tehseen, Ramayah, & Sajilan, Citation2017). To determine the indirect effect of SCS on the relationship between WFE and job satisfaction and between WFE and work engagement, bootstrapping (with 10,000 iterations) with the ability to construct two‐sided, bias‐corrected 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was used. These CI estimates should not go through zero if a significant mediation effect is required (Rucker, Preacher, Tormala, & Petty, Citation2011).

RESULTS

The results of this study are tabulated and briefly interpreted.

Measurement models

Making use of confirmatory factor analysis, three measurement models were tested.

Model 1 comprised four latent variables: WFE, SCS, job satisfaction, and work engagement. WFE consisted of four first‐order latent variables (18 items): work–family perspectives, work–family effect, work–family time management and work–family socio‐capital. SCS comprised seven first‐order latent variables (23 items): learning and development, work–life balance, positive impact, entrepreneurial success, positive relationships, financial security, and financial achievement. Job satisfaction was measured by three items and work engagement by nine items.

Model 2 followed the same template as model 1, except that all 18 WFE items loaded directly on the single latent variable.

Model 3 followed the same template as model 1, except that all 23 SCS items loaded directly on one first‐order latent variable.

The fit statistics for the three competing measurement models are displayed in Table .

Table 1 Fit statistics of competing measurement models

Results showed that model 2 and 3 did not fit the data. It was decided to continue using model 1 as part of the structural model because this model showed acceptable fit (except for the TLI fit statistic) and not only were its AIC and BIC values the lowest, but the model made sense theoretically and seemed to be the more parsimonious model.

Model refinement

Exploratory analysis was conducted with a view to improving the fit of model 1. Based on the modification indices and due to possible multi‐collinearity, two latent constructs of SCS, namely financial security and financial achievement, were allowed to correlate because it would improve the model fit and a lower chi‐square value would be obtained (Wang & Wang, Citation2012). In addition, one item of the learning and development dimension of the SCS displayed a squared multiple correlation value lower than 0.3 (Hooper, Coughlan, & Mullen, Citation2008) and was therefore removed. The improved model 1 showed the following fit statistics: χ2 = 2,237.30; df = 1,256; CFI = 0.91; TLI = 0.91; RMSEA = 0.05 (0.04; 0.05); SRMR = 0.06; AIC = 36,406.86; BIC = 37,070.00. All item loadings were significantly higher than the suggested 0.50 cut‐off score (Wang & Wang, Citation2012) and loaded significantly (p < .01) on the corresponding factors.

Descriptive statistics, reliabilities, correlations, and test for common bias

A sequence of statistical approaches was followed to detect CMB. First, Harman's single factor test indicated that a single factor could not be extracted, and that the common shared variance was below 35%. Second, following a confirmatory factor analytical approach, using a single factor indicator, also failed to produce a single factor which implies CMB may be absent (Tehseen et al., Citation2017). Finally, we use a common latent factor approach to test for the presence of CMB (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). We constructed a single unmeasured common latent factor with regression lines leading to each observed variable in a measurement model. We constrained these paths to be equal, and constrained the variance of the common factor to 1. Once again the results revealed that the common shared variance is low and the correlational paths between variables are similar to the model without the common factor. Therefore, common method bias does not seem to be an issue in this study.

Table displays the descriptive statistics, composite reliabilities of the various scales and Pearson correlations. The mean score results of all the scales show that participants' answers tended to be on the positive side (“agree”) of the scales. All scale reliabilities display acceptable internal consistencies. Further, Pearson correlations showed statistically significant relationships between all the latent variables (WFE, SCS, job satisfaction and work engagement) (p < .01).

Table 2 Descriptive statistics, reliability coefficients, and correlations (N = 334)

Structural model

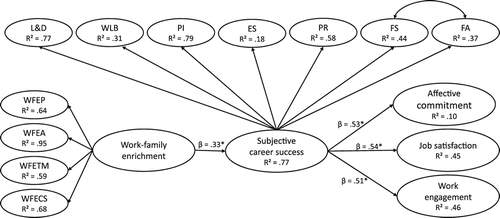

The structural model, displayed in Figure 3, was tested using the measurement model that fitted the best, namely model 1. No difference was found between the chi‐square of the best‐fitting measurement model and the structural model, suggesting acceptable model specification. The model yielded the following fit statistics: χ2 = 2,237.30; df = 1,256; CFI = 0.91; TLI = 0.91; RMSEA = 0.05 (0.04; 0.05); SRMR = 0.06; AIC = 36,406.86; BIC = 37,070.00. The structural model was used to test the relationships between the latent constructs.

Figure 3 Structural model. ES, Entrepreneurial success; FA, Financial achievement; FS, Financial security; L&D, Learning and development; PI, Positive impact; PR, Positive relationships; WFEA, work–family effect; WFEP, work–family perspectives; WFESC, work–family socio‐capital; WFETM, work–family time management; WLB, work–life balance

WFE statistically significantly predicted 12% of the total variance in SCS (β = 0.35; SE: 0.08; p < .01). Similarly, SCS statistically significantly predicted 45% of the variance in job satisfaction (β = 0.55; SE: 0.07; p < .01) and 43% in work engagement (β = 0.52; SE: 0.07; p < .01), respectively. In the presence of SCS, WFE statistically significantly predict job satisfaction (β = 0.27; SE: 0.08; p < .01) and work engagement (β = 0.27; SE: 0.07; p < .01).

Indirect effects

Bootstrapping results (with 10,000 iterations) revealed that SCS mediated the relations between WFE and job satisfaction (β = 0.32; 95% CI: 0.08, 0.32) and work engagement (β = 0.33; 95% CI: 0.07; 0.31) with significant indirect effects at the 95% CI that did not go through zero. Therefore, WFE has shown to have a significant indirect effect through SCS on job satisfaction and work engagement.

DISCUSSION

The aim of the study was to investigate the mediation function of perceived career success on the relation between WFE, job satisfaction and work engagement. Our results revealed a positive relation between WFE and SCS, suggesting that being simultaneously engaged in multiple work and family roles can have an effect on the individuals' appraisal of how successful they are in their career. Furthermore, we also found SCS to be positively related to job satisfaction as well as work engagement. In addition, results demonstrate that WFE indirectly effected job satisfaction and work engagement, via SCS.

The results showed that WFE had a significant positive relationship with SCS. Thus, when employees perceive their work and family lives as enriching (WFE), they may feel a sense of control over their work and family lives, contributing to an increased self‐esteem, sense of accomplishment and satisfaction, promoting their feelings of subjective career success. According to Arthur et al. (Citation2005), when employees receive benefits that aid them in performing in both their work and home domains, they receive benefits that are uniquely desired; hence they experience subjective career success.

Futhermore, our findings correspond with previous literature indicating that WFE and SCS lead to job satisfaction and engagement (Akram, Malik, Nadeem, & Atta, Citation2014; Shockley & Singla, Citation2011; Simo et al., Citation2010). Suggesting that when employees experience themselves as being successful, or have positive feelings about their work–home interface, they are likely to be more satisfied with their job and feel engaged in their work. Such a relationship occurs because the more employees feel they have succeeded in their job, the more satisfied they will be (Tremblay, Dahn, & Gianecchini, Citation2014). Our results also suggest that when employees feel subjectively successful in their career, a sense of belonging in the organisation and a love for the job is experienced. As a result employees invest time, energy and dedication in the job, and become more engaged (Coetzee et al., Citation2010; Karsan, Citation2011; Smith et al., Citation2012).

Finally, the study showed support for the mediating role that SCS could play in relation to WFE and job satisfaction and work engagement. Looking through the RGD lense, the resources employees gain when experiencing WFE, lead to positive feelings and evaluations about their work, resulting in more energetic and engaged employees (Zhang et al., Citation2018). In additon, these employees may develop a sense of belonging to and connection with the organisation, resulting in positive outcomes such as satisfaction. This is in line with the finding of Amin et al. (Citation2017), that employees will have positive work experiences and a pscyhological bond with their careers if they perceive their jobs as making it possible for them to balance their work and family roles. Viewed from an enrichment perspective, the resources used at work and the positive effects gained in fulfilling non‐work roles help employees to achieve goals at work that are of personal value to them, thereby increasing their satisfaction (Hirschi et al., Citation2016).

Implications and recommendations

When considering the instrumental and affective paths underpinnning the WFE theory, organisations can increase employees' affective and resource consequences (job satisfaction and work engagement), either by focusing on indiviudals' skills, attitudes and material resources (instrumental path) or by fostering positive affect in the work environment (e.g., fostering a work–family culture in the organisation). Furthermore, by providing employees opportunities for growth and development in their careers through continous formal training, education and by enhancing their entrepeneural skills, employees will experience more satisfaction in their jobs and become more engaged. Our findings suggest that employees who are able to use resources in their work environment feel more positive and enriched in their personal lives and also more successful in their careers. If organisations contribute to employees' experiences of WFE and SCS, employees become more positive towards their organisations.

Overall, our findings points to how organisations can increase the engagement and satisfaction levels of their employees, by fostering conditions of WFE or by focusing on the various resources associated with WFE. Grawitch, Barber, and Justice (Citation2010) understand balancing work and personal life as effective allocation of personal resources across the various life pursuits. These authors argue that organisations can influence the process of personal resource allocation by focussing interventions towards increasing employees' pool of available resources, altering their demands, and providing sufficient resources to help increase their personal supply. According to Koekemoer and Petrou (Citation2019), specific strategies may include taking control over one's worktime and result‐oriented work, since by giving employees more control over their time, they are in fact contributing to increased allocation of resources. Furthermore, by considering perceptions of work overload and focusing on more efficient work, organisations are altering the demands that employees face, again increasing their supply of resources. When organisations ensure the availability of sufficient human, technological, financial, and other resources to achieve its goals, they are also providing optimal conditions for work–family balance. Organisations should therefor attempt to enhance the experience of WFE by providing employees avenues to increase this enrichment phenomenon which may also include flexible work arrangements (e.g., flex time, offsite work and compressed workweeks) (Greenhaus & Powell, Citation2006) or family–friendly work policies (e.g., parental leave, flexible emergency leave and family–friendly environment) (Martinez‐Sanchez, Perez‐Perez, Vela‐Jimenez, & Abella‐Garces, Citation2018) or time management skills. As these aspects may lead to enrichment experiences. With regards to socio‐capital resources, Kossek, Hammer, Kelly, and Moen (Citation2014) provide evidence that specific family‐supportive supervision may impact stronger on the work–family domain than general supportive supervision. In this sense, “family‐supportive supervisors are those who appreciate and have an understanding for employees' demands outside of the work domain and accommodate employees' efforts to seek balance between these roles” (Kossek et al., Citation2014, p. 8). Taken together our findings concur with the view of Spurk, Hirschi, and Dries (Citation2019), that career success, as a resource, can change career attitudes in a positive manner and in turn, affects resource management behaviours and attitudes.

Limitations

Some limitations of the current study are acknowledged: the use of a cross‐sectional design excluded the possibility of inferring causal relationships between variables; and the use of convenience sampling could impact on the generalisability of the findings.

CONCLUSION

To summarise, the current study contributes to theory in that it strengthens the bridge between research done on work–family enrichment and career success. This study represents one of the first empirical inquiries using RGD as explanation to determine the indirect effects of SCS on the well‐established relationship between WFE, job satisfaction and work engagement. The contribution of this study to practice is its finding that organisations can gain significant benefits (e.g., satisfied and engaged employees) if they enhance work environments (e.g., by providing relevant resources) that are conducive to work–family enrichment and, by implication, subjective career success and positive work outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The financial assistance of the National Research Foundation (NRF) in conducting this research is acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at are those of the author and are not necessarily attributed to the National Research Foundation. This research is based on work supported by the National Research Foundation under the reference number, TTK14051567368. The authors would like to acknowledge and thank the members of the 5C group for granting permission to use the career success scale which is the intellectual property of the 5C Group. Readers interested in doing research using this career success instrument should contact the 5C directly ([email protected]).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

Funding information National Research Foundation, Grant/Award Number: TTK14051567368

REFERENCES

- Akkermans, J., & Kubasch, S. (2017). Trending topics in careers: A review and future research agenda. Career Development International, 22(6), 586–627.

- Akram, H., Malik, N. I., Nadeem, M., & Atta, M. (2014). Work‐family enrichment as predictors of work outcomes among teachers. Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences, 8(3), 733–743.

- Amin, S., Arshad, R., & Ghani, R. A. (2017). Social support and subjective career success: The role of work‐family balance and career commitment as mediator. Journal Pengurusan, 50, 133–142. https://doi.org/10.17576/pengurusan-2017-50-12

- Arthur, M. B., Khapova, S. N., & Wilderom, C. P. (2005). Career success in a boundaryless career world. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(2), 177–202.

- Aryee, S., Srinivas, E. S., & Tan, H. H. (2005). Rhythms of life: Antecedents and outcomes of work‐family balance in employed parents. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1), 132–146. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.1.132

- Beigi, M., Wang, J., & Arthur, M. (2017). Work‐family interface in the context of career success: A qualitative inquiry. Human Relations, 70(9), 1091–1114. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726717691339

- Briscoe, J. P., Kase, R., Dries, N., Dysvik, A., & Unite, J. (2019). The dual aspect importance & achievement career success scale. Copyrighted scale, 2019.

- Chung, E., Kamri, T., & Mathew, V. N. (2018). Work‐family conflict, work‐family facilitation and job satisfaction: Considering the role of generational differences. International Journal of Education, Psychology and Counseling, 3(13), 32–43.

- Coetzee, M., Bergh, Z., & Schreuder, D. (2010). The influence of career orientations on subjective work experiences. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 8(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v8i1.279

- Daniel, S., & Sonnentag, S. (2016). Crossing the borders: The relationship between boundary management, work‐family enrichment and job satisfaction. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27, 407–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1020826

- De hauw, S., & Greenhaus, J. H. (2015). Building a sustainable career: The role of work—Home balance in career decision making. In Handbook of Research on Sustainable Careers, Cheltenham, UK/Northampton MA, USA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- De klerk, M., Nel, J. A., Hill, C., & Koekemoer, E. (2013). The development of the MACE work‐family enrichment instrument. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology/SA Tydskrif vir Bedryfsielkunde, 39(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v39i2.1147

- De klerk, M., Nel, J. A., & Koekemoer, E. (2015). Work‐to‐family enrichment: Influences of work resources, work engagement and satisfaction among employees within the South African context. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 25(6), 537–546. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2015.1124606

- Ng, T. W. H., Eby, L. T., Sorensen, K. L., & Feldman, D. C. (2005). Predictors of objective and subjective career success: A meta‐analysis. Personnel Psychology, 58(2), 367–408.

- Friedman, S., & Greenhaus, J. (2000). Work and family—allies or enemies?: What happens when business professionals confront life choices. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Grawitch, M. J., Barber, L. K., & Justice, L. (2010). Rethinking the work‐life interface: It's not about balance, It's about resource allocation. Applied Psychology Health and Well‐Being, 2(2), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-0854.2009.01023.x

- Greenhaus, J. H., & Allen, T. D. (2011). Work‐family balance: A review and extension of the literature. In J. C. Quick & L. E. Tetrick (Eds.), Handbook of occupational health psychology (pp. 165–183). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Greenhaus, J. H., & Kossek, E. E. (2014). The contemporary career: A work‐home perspective. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 361–388. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091324

- Greenhaus, J. H., & Powell, G. N. (2006). When work and family are allies: A theory of work‐family enrichment. Academy of Management Review, 31(1), 72–92. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2006.19379625

- Hakanen, J. J., Peeters, M. C. W., & Perhoniemi, R. (2011). Enrichment processes and gain spirals at work and at home: A 3‐year cross‐lagged panel study. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84(1), 8–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.2010.02014.x

- Hall, D. T., Lee, M. D., Kossek, E. E., & Heras, M. L. (2012). Pursuing career success while sustaining personal and family well‐being: A study of reduced‐load professionals over time. Journal of Social Issues, 4, 742–766. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2012.01774.x

- Hanson, G. C., Hammer, L. B., & Colton, C. L. (2006). Development and validation of a multidimensional scale of perceived work‐family positive spillover. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 11(3), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.11.3.249

- Hellgren, J., Sjöberg, A., & Sverke, M. (1997). Intention to quit: Effects of job satisfaction and job perceptions. In F. Avallone, J. Arnold, & K.deWitte (Eds.), Feelings Work in Europe (pp. 415–423). Milan: Guerini.

- Hirschi, A., Hermann, A., Nagy, N., & Spurk, D. (2016). All in the name of work? Nonwork orientations as predictors of salary, career satisfaction, and life satisfaction. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 95, 46–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2016.07.006

- Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60.

- Judge, T. A., Cable, D. M., Boudreau, J. W., & Bretz, R. D., Jr. (1995). An empirical investigation of the predictors of executive career success. Personnel Psychology, 48(3), 485–519. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/cahrswp/233

- Karsan, R. (2011). Engagement and career success. Training Journal, 12–16.

- Koekemoer, E., & Olckers, C. (2019). Women's wellbeing at work: Their experience of work‐family enrichment and subjective career success. In I. L. Potgieter, N. Ferreira, & M. Coetzee (Eds.), Theory, Research and Dynamics of Career Wellbeing: Becoming Fit for the Future. Switzerland AG: Springer Nature.

- Koekemoer, E., & Petrou, M. (2019). Positive psychological interventions intended for a supportive work‐family culture. In L. E.vanZyl & S. Rothmann, Sr. (Eds.), Evidence‐Based Positive Psychological Interventions in Multi‐Cultural Contexts. Switzerland AG: Springer Nature.

- Koekemoer, E., Strasheim, A., & Cross, R. (2017). The influence of simultaneous interference and enrichment in work–family interaction on work‐related outcomes. South Africa Journal of Psychology, 47(3), 330–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246316682631

- Kossek, E. E., Hammer, L. B., Kelly, E. L., & Moen, P. (2014). Designing work, family and health organizational change initiatives. Organizational Dynamics, 43(1), 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2013.10.007

- Martinez‐sanchez, A., Perez‐perez, M., Vela‐jimenez, M., & Abella‐garces, S. (2018). Job satisfaction and work–family policies through work‐family enrichment. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 33(5), 386–402. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-10-2017-0376

- Mayrhofer, W., Briscoe, J. P., Hall, D. T., Dickmann, M., Dries, N., Dysvik, A., … Unite, J. (2016). Career success across the globe: Insights from the 5C project. Organizational Dynamics, 42(2), 197–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2016.07.005

- Mcdonald, K. S., & Hite, L. M. (2008). The next generation of career success: Implications for HRD. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 10(1), 86–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422307310116

- Moazami‐goodarzi, A., Nurmi, J. E., Mauno, S., & Rantanen, J. (2015). Cross‐lagged relations between work–family enrichment, vigor at work, and core self‐evaluations: A three‐wave study. Journal of Business and Psychology, 30(3), 473–482.

- Ng, T. W. H., & Feldman, D. C. (2014). Subjective career success: A meta‐analytic review. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 85(2), 169–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.06.001

- Pan, J., & Zhou, W. (2015). How do employees construe their career success: An improved measure of subjective career success. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 23(1), 45–58.

- Podsakoff, P. M., Mackenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Qing, G., & Zhou, E. (2017). Bidirectional work–family enrichment mediates the relationship between family‐supportive supervisor behaviors and work engagement. Social Behavior and Personality, 45(2), 299–308. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.6023

- Raykov, T. (2009). Interval estimation of revision effect on scale reliability via covariance structure analysis. Structural Equation Modeling, 16, 539–555. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510903008337

- Rucker, D. D., Preacher, K. J., Tormala, Z. L., & Petty, R. E. (2011). Mediation analysis in social psychology: Current practices and new recommendations. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(6), 359–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00355.x

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2003). UWES—work engagement scale. Test Manual, 66, 701–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164405282471

- Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González‐romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 71–92. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015630930326

- Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2006). Flow and the foundations of positive psychology: The collected works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. In Learned optimism: How to change your mind. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Shockley, K. M., & Singla, N. (2011). Reconsidering work‐family interactions and satisfaction: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Management, 37(3), 861–886. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310394864

- Shockley, K. M., Ureksoy, H., Rodopman, O. B., Poteat, L. F., & Dullaghan, T. R. (2016). Development of a new scale to measure subjective career success: A mixed‐methods study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(1), 128–153.

- Sieber, S. D. (1974). Toward a theory of role accumulation. American Sociological Review, 39(4), 567–578.

- Simo, P., Enache, M., Leyes, J. M. S., & Alarcon, V. F. (2010). Analysis of the relation between subjective career success, organizational commitment and the intention to leave the organization. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 29(E), 144–158.

- Siu, O., Lu, J. F., Brough, P., Lu, C., Bakker, A. B., Kalliath, T., … O'driscoll, M. (2010). Role resources and work‐family enrichment: The role of work engagement. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 77(3), 470–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2010.06.007

- Smith, P., Caputi, P., & Crittenden, N. (2012). How are women's glass ceiling beliefs related to career success?Career Development International, 17(5), 458–474. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620431211269702

- Spurk, D., Hirschi, A., & Dries, N. (2019). Antecedents and outcomes of objective versus subjective career success: Competing perspectives and future directions. Journal of Management, 45, 35–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318786563

- Tehseen, S., Ramayah, T., & Sajilan, S. (2017). Testing and controlling for common method variance: A review of available methods. Journal of Management Sciences, 4(2), 142–168. https://doi.org/10.20547/jms.2014.1704202

- Ten brummelhuis, L. L., & Bakker, A. B. (2012). A resource perspective on the work–home interface: The work–home resources model. American Psychologist, 67(7), 545–556.

- Timms, C., Brough, P., O'driscoll, M., Kalliath, T., Siu, O. L., Sit, C., & Lo, D. (2015). Positive pathways to engaging workers: Work–family enrichment as a predictor of work engagement. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 53(4), 490–510.

- Tremblay, M., Dahn, J., & Gianecchini, M. (2014). The mediating influence of career success in relationship between career mobility criteria, career anchors and satisfaction with organization. Personnel Review, 43(6), 818–844. https://doi.org/10.1108/pr-08-2012-0138

- vanZyl, L. E., vanOort, A., Rispens, S., & Olckers, C. (2019). Work engagement and task performance within a global IT company: The mediating role of innovative work behaviours. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00339-1

- Wang, J., & Wang, X. (2012). Structural equation modeling: Applications using Mplus. Chichester: Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118356258

- Wayne, J. H., Grzywacz, J. G., Carlson, D. S., & Kacmar, K. M. (2007). Work‐family facilitation: A theoretical explanation and model of primary antecedents and consequences. Human Resource Management Review, 17(1), 63–76.

- Zhang, Y., Xu, S., Jin, J., & Ford, M. T. (2018). The within and cross domain effects of work‐family enrichment: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 104, 210–227.