Abstract

Objective

Involuntary job loss can lead to symptoms of complicated grief (CG), depression, and anxiety. Information about the temporal linkage between these symptoms is limited and may have implications for the treatment of those suffering from mental health complaints after dismissal. The aim of this study was to explore the possible reciprocal relationships between symptoms of CG, depression, and anxiety following involuntary job loss.

Method

We recruited 128 Dutch workers who had lost their job within the past 12 months, including 72 males and 56 females with an average age of 49.8 (SD = 9.0) years. They completed questionnaires tapping CG, depression, and anxiety symptoms at baseline (Time 1) and a 6‐month follow‐up (Time 2). Several cross‐lagged panel models were compared.

Results

Our analyses indicated that CG symptom severity following job loss at Time 1 predicted depression at Time 2, but not vice versa. Similar results were found for job loss‐related CG and anxiety symptoms.

Conclusions

Symptom‐levels of CG following job loss predict later depression and anxiety symptoms more strongly than vice versa. This implies that screening and targeting job loss‐related CG symptoms with early interventions might protect individuals from developing depression or anxiety symptoms after their dismissal.

Key Points

Involuntary job loss can cause mental health problems, such as symptoms of complicated grief, depression, and anxiety.

The results of this study suggest that complicated grief symptoms following job loss predict depression and anxiety symptoms later in time.

Hence, screening and preventive measures targeting complicated grief might reduce the risk of developing additional mental health issues after dismissal.

INTRODUCTION

Involuntary job loss is major life event (Miller & Rahe, Citation1997). It involves many secondary losses, such as loss of collective purpose, social contacts, status, identity, time structure, and financial security (e.g., Jahoda, Citation1981). The attachment to the lost job, the disruption of identity, the sense of self, relationships and social roles can lead to symptoms of grief (Papa & Lancaster, Citation2016). Although most people show a resilient response when facing stressful life events like bereavement, divorce, and marriage, a minority group shows a decrease in subjective well‐being (Mancini, Bonanno, & Clark, Citation2011). Meaning, identity, and basic assumptions about the self, the world, and others need to be reviewed and reconstructed in case of bereavement, as well as in non‐bereavement losses like job loss, divorce (Harvey & Miller, Citation1998; Papa, Lancaster, & Kahler, Citation2014), and romantic break‐ups (Boelen & Reijntjes, Citation2009).

Several studies have shown that involuntary job loss can lead to symptoms of grief, depression, and anxiety (Archer & Rhodes, Citation1993; Brewington, Nassar‐McMillan, Flowers, & Furr, Citation2004; Papa & Maitoza, Citation2013). In general, these grief symptoms decrease over time. However, in some persons they remain and evolve into symptoms of complicated grief (CG; Papa & Lancaster, Citation2016; Van Eersel, Taris, & Boelen, Citation2019). Research on job loss‐related CG symptoms is sparse and predominantly based on cross‐sectional data. Hence, knowledge of the long‐term effects of job loss‐related CG symptoms and their relationships to other mental health problems is limited.

Characteristics of job loss‐related CG symptoms include preoccupying thoughts about the lost job, disbelief or inability to accept the loss, bitterness, and a sense that life is meaningless without the former occupation. CG symptoms following job loss can co‐occur with symptoms of depression and/or anxiety. Even though there is an overlap in symptoms between CG, depression, and anxiety, factor‐analytic studies have shown that these symptoms form distinguishable concepts (Papa & Maitoza, Citation2013; Van Eersel et al., Citation2019). Still little is known about whether and how symptoms of CG, depression, and anxiety following job loss influence each other over time. It is conceivable that people who experience job loss‐related CG symptoms are at risk for developing depression or anxiety symptoms later in time, but the reverse relationship would also seem defensible. Thus, at present the temporal relationship between CG, depression, and anxiety connected with job‐loss is still largely unclear.

Symptoms of CG and depression

Knowledge on the relationship between CG and depression symptoms following involuntary job loss is limited. Jahoda (Citation1981) argued that deprivation of the latent functions of work (e.g., time structure, identity, shared goals, contact with others, and purpose) triggers the development of depressive symptoms after job loss. Over the years, cross‐sectional and longitudinal studies have revealed the potential negative impact of involuntary job loss on psychological and physiological well‐being (among others, McKee‐Ryan, Song, Wanberg, & Kinicki, Citation2005; Paul & Moser, Citation2009). However, job loss‐related CG symptoms were not addressed in prior longitudinal research. For instance, in their cross‐lagged analysis, Howe et al. (Citation2017) found that the severity of the job loss (e.g., in terms of lost income and/or benefits) was associated with the intensity of subsequent depressive symptoms but not with the level of anxiety symptoms. Stolove, Galatzer‐Levy, and Bonanno (Citation2017) showed that people who were resilient or who were remitting from depression had a greater chance of being re‐employed, compared to people who experienced chronic or emergent depressive symptoms.

To our knowledge, longitudinal studies to examine the linkage between CG and depression symptoms following loss events have only focused on CG symptoms following bereavement losses. Shear et al. (Citation2011) stated that having a psychiatric diagnosis, especially a mood disorder, is a risk factor for the development of CG following bereavement. In their cross‐lagged analysis among widowers, Prigerson et al. (Citation1996) found that CG symptoms predicted depression at 18‐month post‐loss follow‐up, whereas initial depression did not predict subsequent grief. Lenferink, Nickerson, de Keijser, Smid, and Boelen (Citation2019) obtained a similar result in their cross‐lagged analysis: changes in the level of CG symptoms had a greater impact on depression than vice versa.

The results of these sparse studies suggest that the relationship between CG and depression is reciprocal. From a theoretical viewpoint, one could argue that elevated CG following job loss aggravates later depression because the preoccupation with the loss of the job, implicated in job loss‐related CG, could block the motivation to engage in potentially pleasurable activities, consequently fuelling depressive feelings and anhedonia. Conversely, depression following job loss could precede CG, such that the feelings of guilt and hopelessness implicated in elevated depression contribute to a tendency to yearn for what was lost.

Symptoms of CG and anxiety

Research on the relationship between job loss‐related CG symptoms and anxiety is scarce as well. Some studies have shown that these concepts represent theoretically as well empirically distinct phenomena (Archer & Rhodes, Citation1993; Papa & Maitoza, Citation2013; Van Eersel et al., Citation2019). None of these studies explored the possible reciprocal associations between CG and anxiety symptoms related to involuntary job loss.

In bereavement studies, CG has been found to be associated with high rates of comorbid anxiety disorders (Marques et al., Citation2013; Simon et al., Citation2007). According to Bui et al. (Citation2013), pre‐existing anxiety symptoms could increase the risk of CG following loss elicited by a preference of maladaptive coping styles. At present, there are no prospective studies published on the relation between CG and anxiety, only of post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and CG; studies have shown that the level of CG symptoms predicted PTSD symptoms later in time more strongly than PTSD predicted CG after loss (Djelantik, Smid, Kleber, & Boelen, Citation2018; Lenferink et al., Citation2019).

From a theoretical viewpoint, one could argue that elevated CG symptoms following job loss inflates later anxiety because experiential avoidance, which is a hallmark symptom of job loss‐related CG, can also lead to avoidance in other life areas and increase anxiety symptoms. Conversely, anxiety could also precede job loss‐related CG symptoms because it interferes with elaboration of the consequences of the loss, thereby maintaining grief. This could make it harder for people to face reality and accept that their job is permanently lost, leading to an increase of job loss‐related CG symptoms.

Aim of the study

In the present study, we build on prior studies pointing out that job loss‐related CG, depression, and anxiety symptoms are distinguishable (e.g., Papa & Maitoza, Citation2013; Van Eersel et al., Citation2019), to examine the order in which these symptoms influence each other, using cross‐lagged analysis. We used data from participants who completed questionnaires measuring job loss‐related CG, depression, and anxiety symptoms within the first year after their involuntary job loss and again 6 months later. Our aim was to explore to which extent job loss‐related CG, depression, and anxiety symptoms at Time 1 (T1) predicted the level of these symptoms at Time 2 (T2). Based on prior empirical results of job loss and bereavement we explored (a) if CG symptoms following job loss predicted symptom‐levels of depression later in time and vice versa and (b) if job loss‐related CG symptoms predicted symptom‐levels of anxiety over time and vice versa.

This is the first time the temporal relations between symptoms of CG, depression, and anxiety after involuntary job loss are explored. Acquiring knowledge on the reciprocal associations between these symptoms improves our understanding of the etiology of job loss‐related CG symptoms. This could enhance knowledge about which symptoms need to be dealt with first in treatment of comorbid loss‐related symptoms after involuntary job loss, which is imperative for developing more effective interventions and treatment methods.

METHOD

Procedure and participants

This study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of the faculty of Social Sciences of (Utrecht University) (FETC 16‐111). Participants who had involuntarily lost their job were recruited through two channels: (a) workshops about the impact of the job loss for people who had lost their job (N = 15) and (b) social (media) networks (N = 198). At T1, 213 people participated who had lost their job the previous year. All participants provided informed consent. They filled out the survey using paper‐and‐pencil or in a secured online area. Part of this sample from T1 was included in another study of our research program (Van Eersel et al., Citation2019). After 6 months (T2) the participants were invited to fill out the questionnaires again in an online format administered through a secured online area; 128 participants (60%) completed this follow‐up study. The T1–T2 interval ranged from 5.5 to 7.1 months (M = 6.3; SD = 0.3 months).

Dropout analyses

The T2 responders were compared to the T2 non‐responders using t‐tests and chi‐square tests on background variables (e.g., age, gender, and education), features of the job loss (e.g., time since loss, duration of employment, and cause of dismissal), and symptom scores at T1. Outcomes, summarised in Table , showed that T2 non‐responders were younger (t[211] = 3.56, p < .001) and had higher depression scores (t[211] = −2.15, p < .05) than the T2 responders.

Table 1 Characteristics of the participants at Time 1

Measures

Demographics

From all participants demographic data and characteristics of the loss of their jobs were collected (Table ).

Job Loss Grief Scale

For the measurement of the CG symptoms following job loss, the job loss grief scale (JLGS; Van Eersel et al., Citation2019) was used. With their job loss in mind, participants rated the extent to which they experienced the listed 33 symptoms (e.g., “I can't accept the loss of my job,” “Memories about the loss of my job upset me”) during the past month on a 5‐point scale (1 = “never”, 5 = “always”). A study by Van Eersel et al. (Citation2019) indicated that the scale has good psychometric properties. In the present sample Cronbach's α was .97 at both T1 and T2.

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS‐21)

For the measurement of depression and anxiety symptoms, the DASS‐21 (Lovibond & Lovibond, Citation1995) was used. Participants rated the extent to which they had experienced the 21 symptoms listed during the preceding week (e.g., “I felt I had no desire for anything,” “I felt afraid for no reason”) on a 4‐point scale (1 = “never or rarely”, 4 = “always or frequently”). Henry and Crawford (Citation2005) showed that the measure has good psychometrics. In the present sample Cronbach's α for depression was .91 at T1 and T2, and for anxiety was .83 at T1 and .81 at T2.

Statistical analyses

Ten models were consecutively tested in Mplus version 8 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation1998), to examine the reciprocal relationships between symptoms levels of job loss‐related CG, depression, and/or anxiety, represented by the summed score on the JLGS, the subscale of depression of the DASS‐21, and the subscale anxiety of the DASS‐21, respectively.

In Model 1, we looked at the auto‐regressive paths of the job loss‐related CG and depression data, further allowing T1 depression and T1 job loss‐related CG to correlate. Model 2 extended Model 1 with the cross‐lagged path between T1 depression and T2 job loss‐related CG. Model 3 was similar to Model 1, adding the cross‐lagged path between T1 job loss‐related CG and T2 depression. In Model 4 we integrated Models 1–3, including the auto‐regressive paths, the T1 and T2 associations between CG and depression, and both cross‐lagged paths. Model 5 was based on Model 4, but here the cross‐lagged paths were constrained to be equal to each other. Five similar models (Models 6–10) were examined with anxiety instead of depression.

We computed and compared the statistical fit of all models. Goodness of fit was evaluated with the χ2‐value, the χ2/df ratio, CFI, and the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR), because these measures provide the most useful information for samples with less than 200 subjects (Hooper, Coughlan, & Mullen, Citation2008). Lower values of χ2 and χ2/df ratio indicate better fit (Hoelter, Citation1983), CFI values of >0.95 are good (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999), and SRMR values of <0.08 are acceptable (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999) and <0.05 good (Byrne, Citation1998). The associated dataset is freely retrievable (Van Eersel, Taris, & Boelen, 2020).

The results reported below are based on the data from the participants who participated in both waves (N = 128). These results were compared to those obtained after multiple imputation of the T2‐data for those who participated at T1, but not at T2 (N = 231). Since both sets of findings were highly similar and led to identical conclusions and recommendations, for brevity we report only the findings obtained for those who participated in both waves (N = 128). The other results can upon request be obtained from the corresponding author.

RESULTS

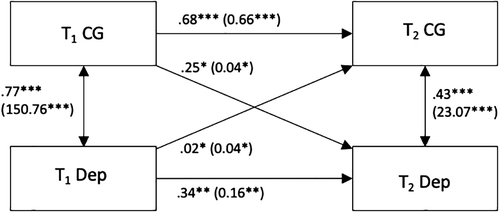

Table summarises the fit indices for all models and presents the model comparisons. Model 1 examined the autoregressive pathways of job loss‐related CG on T1 and T2, and depression on T1 and T2. The results showed that T1 CG was associated with T2 CG, and that T1 depression was associated with T2 depression. Model 2 added the cross‐lagged path of T1 depression on T2 job loss‐related CG to Model 1. The results indicate that depression at T1 predicts CG symptoms following job loss at T2 (β = .22, p < .05). Model 2 showed significantly better fit indices than Model 1. Model 3 was similar to Model 2, but examined the other cross‐lagged path. The results indicated that CG at T1 predicts depression symptoms at T2 (β = .25, p < .05). Model 3 also improved significantly on Model 1. In Model 4 all paths were tested in a single model, which led to a fully saturated model with a perfect fit. Models 2–4 did not differ significantly (Table ). Model 5 examined whether the cross‐lagged associations between job loss‐related CG and depression differed significantly. Table shows that the chi‐square increase for Model 5 compared to the fit of Model 4 was not significant, Δχ2 with 1 df = 2.28, p > .05. Thus, the cross‐lagged effect of CG on depression did not differ significantly from that of depression on CG. Models 2, 3 and 5 cannot be statistically compared because they all have the same number of df, but in conjunction these models essentially indicate that job loss‐related CG and depression are reciprocally related. The results for Model 5 are shown in Figure 1. T1 job loss‐related CG significantly predicted T2 depression (β = .25, p < .05). This indicates that for every point increase of the CG sum score at T1, the depression sum score at T2 will be 0.25 points higher on the standardised scale, when controlling for the other parameters in the model. Conversely, a small part of T1 depression was also significantly associated with T2 CG (β = .02, p < .05).

Table 2 Comparison between all models

Figure 1 Model 5 cross‐lagged associations between job loss‐related complicated grief and depression. Note. CG, complicated grief; Dep, depression; first estimate, standardised effect; second estimate (in brackets), unstandardized effect. * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001

A similar set of consecutive models was compared for the associations between CG following job loss and anxiety. Model 6 presented good fit indices (Table ), showing significant autoregressive pathways for CG following job loss on T1 and T2, and anxiety on T1 and T2. Model 7 did not find a significant relation between T1 anxiety and T2 job loss‐related CG (β = .14, p = .07), and showed no significant improvement in fit compared to Model 6. Model 8 examined the relation between T1 job loss‐related CG and T2 anxiety (β = .23, p < .05), significantly improving on Model 6. Model 9 tested all pathways in a single model and thus was fully saturated with a perfect fit. This model was not a significant improvement compared to Model 8.

Finally, Model 10 examined whether the cross‐lagged associations between CG following job loss and anxiety could be constrained to be equal. Constraining these cross‐lagged effects showed no significant improvement on Model 9 (cf. Table ). Models 8 and 10 have the same number of df and could not be compared statistically; both models indicate a reciprocal relationship between CG following job loss and anxiety. T1 job loss‐related CG appeared to explain a greater amount of the variance of T2 anxiety (β = .23, p < .05) in Model 10, compared to the variance in T2 CG that was explained by T1 anxiety (β = .01, p < .05). Figure 2 shows the results for Model 10.

DISCUSSION

The objective of this study was to explore the possibly reciprocal relations between job loss‐related CG, depression, and anxiety symptoms. Using two‐wave panel data from 128 people who had lost their jobs, the results revealed a significant relationship between job loss‐related CG and depression at both time points for the cross‐lagged pathways. Nonetheless, the effect of T1 job loss‐related CG on T2 depression was stronger than the effect of T1 depression on T2 CG following job loss. This indicates that a higher score on job loss‐related CG symptoms is associated with a higher score on depression symptoms, even when controlling for the stability of symptom levels of CG after job loss and depression on T1 and T2. Similar results were found for job loss‐related CG and anxiety symptoms. Again, T1 CG symptoms following job loss were more strongly related with a higher score on T2 anxiety than vice versa, which remained when controlling for the symptom stability level of job loss‐related CG and anxiety on T1 and T2. Based on these results, we can conclude that CG symptoms following job loss are associated with later depression and anxiety symptoms.

Looking at prior studies, our results correspond with the outcome of bereavement studies by Djelantik et al. (Citation2018), Lenferink et al. (Citation2019), and Prigerson et al. (Citation1996) on CG, depression, and PTSD. These findings provide the first evidence that job loss‐related CG symptoms may contribute to the exacerbation of depression and anxiety symptoms later in time.

Our findings suggest that yearning for, and preoccupation with the lost job, may block engagement in positive, valued activities (fuelling depression) and fears and worries about the future (fuelling anxiety). A possible explanation could be provided by the stress sensitization theory (Smid et al., Citation2015). This theory claims that individuals who are confronted with major life events are more vulnerable to developing depression or anxiety symptoms in response to subsequent stressful events, for example due to negative appraisals about the loss (Smid et al., Citation2015). Job loss can yield multiple descending losses, such as loss of financial security, social contacts, and access to other potential reinforcements associated with employment (Papa & Maitoza, Citation2013). From this perspective, involuntary job loss can trigger certain global beliefs about the self, life or the future, and strengthen maladaptive cognitions regarding trust, esteem, and personal control. These negative schemas can produce negatively biased interpretations, depressive and anxiety symptoms, as a response to the occurrence of other stressful life events. Hence, people who experience job loss‐related CG symptoms seem to be more prone to develop depressive or anxiety symptoms when confronted with subsequent stressful life events.

Limitations

There are some limitations that need to be kept in mind while interpreting these findings. First, our sample size was relatively small (N = 128). Therefore, generalisation must be done with caution, and larger‐scale replication studies are in place. Second, the time between measurements was 6 months. Therefore, it is uncertain if different time intervals can disclose other short‐ or long‐term cross‐lagged effects of CG following job loss, depression, and anxiety. As a result of the time‐interval dependency (Taris, Citation2000), it is possible that the cross‐lagged effect of anxiety on job loss‐related CG needs more time to reveal itself, than of job loss‐related CG on anxiety, or CG following job loss on depression. Even though there are no theoretical or empirical reasons to assume this; since our findings are consistent with earlier cross‐lagged studies on bereavement (Djelantik et al., Citation2018; Lenferink et al., Citation2019; Prigerson et al., Citation1996). Third, the current sample was restricted to participants who had lost their job during the last 12 months. The follow‐up measurement took place between 6 and 18-months after the job loss, because we expected that changes in the severity of CG symptoms would predominantly occur within the first 18-months following the dismissal. However, the present results showed that CG following job loss, depression, and anxiety symptoms can still change 12–18-months after the job loss occurred. Therefore, it would be interesting to explore the development of job loss‐related CG, depression, and anxiety symptoms, over a longer period of time with more waves, to gain more insight in how they interact and how intertwined clusters are formed. Research with more than two assessments would also allow the application of more sophisticated statistics, such as random intercept cross‐lagged modelling (Hamaker, Kuiper, & Grasman, Citation2015). Finally, it would be useful for future research to study other emotional symptoms following involuntarily job loss including symptoms of adjustment disorder (Maercker et al., Citation2013).

Implications

Our findings in an early stage might reduce the risk for later depressive or anxiety symptoms over time. Note that the presence of depression or anxiety symptoms does not appear to predict the aggravation of job loss‐related CG symptoms later in time.

Moreover, our data provide evidence that CG symptoms following job loss can aggravate depression and anxiety symptoms over time. This implies that preventive interventions should focus on, for example, acceptance of the job loss or reducing the sense of meaningfulness after the job loss. Individuals could be stimulated to re‐engage in meaningful social activities to reduce the risk for the development of elevated depressive symptoms. Interventions that focus on cognitive restructuring, could target the fears and worries about the future to prohibit anxiety symptoms from increasing.

Furthermore, our results indicate that psychopathological symptoms following job loss are relatively stable in time. Hence, during screening it seems useful to focus on the recognition of job loss‐related CG symptoms, next to anxiety and depression symptoms. If elevated CG symptoms are identified in the first year after the job loss, precautions can be made to keep the situation from becoming worse through development of depressive or anxiety symptoms. Reduction of job loss‐related CG symptoms can prevent other mental health problems from evolving and increase well‐being, and therefore enhances the chance of sustainable re‐employment.

CONCLUSION

Notwithstanding the study limitations, our findings indicate that job loss‐related CG symptoms affect depressive and anxiety symptoms more strongly than vice versa. This implicates that screening and early interventions aiming CG symptoms following job loss might reduce the risk for later development of depressive or anxiety symptoms after the dismissal. Hence, awareness about the consequences of job loss‐related CG symptoms needs to become common knowledge among practitioners as well as people who are confronted with involuntary job loss.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Archer, J., & Rhodes, V. (1993). The grief process and job loss: A cross‐sectional study. British Journal of Psychology, 84(3), 395–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1993.tb02491.x

- Boelen, P. A., & Reijntjes, A. (2009). Negative cognitions in emotional problems following romantic relationship break‐ups. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress, 25(1), 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.1219

- Brewington, J. O., Nassar‐mcmillan, S. C., Flowers, C. P., & Furr, S. R. (2004). A preliminary investigation of factors associated with job loss grief. Career Development Quarterly, 53(1), 78–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2004.tb00657.x

- Bui, E., Leblanc, N. J., Morris, L. K., Marques, L., Shear, M. K., & Simon, N. M. (2013). Panic‐agoraphobic spectrum symptoms in complicated grief. Psychiatry Research, 209(1), 118–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2013.03.033

- Byrne, B. M. (1998). Structural equation modeling with LISREL, PRELIS and SIMPLIS: Basic concepts, applications and programming. New York: Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203774762

- Djelantik, A. A. A. M. J., Smid, G. E., Kleber, R. J., & Boelen, P. A. (2018). Do prolonged grief disorder symptoms predict post‐traumatic stress disorder symptoms following bereavement? A cross‐lagged analysis. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 80, 65–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.09.001

- Hamaker, E. L., Kuiper, R. M., & Grasman, R. P. (2015). A critique of the cross‐lagged panel model. Psychological Methods, 20(1), 102–116. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038889

- Harvey, J. H., & Miller, E. D. (1998). Toward a psychology of loss. Psychological Science, 9(6), 429–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00081

- Henry, J. D., & Crawford, J. R. (2005). The short‐form version of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS‐21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non‐clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44, 227–239. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466505X29657

- Hoelter, J. W. (1983). The analysis of covariance structures: Goodness‐of‐fit indices. Sociological Methods & Research, 11(3), 325–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124183011003003

- Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60. https://doi.org/10.21427/D7CF7R

- Howe, G. W., Cimporescu, M., Seltzer, R., Neiderhiser, J. M., Moreno, F., & Weihs, K. (2017). Combining stress exposure and stress generation: Does neuroticism alter the dynamic interplay of stress, depression, and anxiety following job loss? Journal of Personality, 85(4), 553–564. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12260

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Jahoda, M. (1981). Work, employment, and unemployment: Values, theories, and approaches in social research. American Psychologist, 36(2), 184–191. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.36.2.184

- Lenferink, L. I. M., Nickerson, A., de Keijser, J., Smid, G. E., & Boelen, P. A. (2019). Reciprocal associations between symptom levels of disturbed grief, posttraumatic stress, and depression following traumatic loss: A four‐wave cross‐lagged study. Clinical Psychological Science, 7(6), 1330–1339. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702619858288

- Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the Beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U

- Maercker, A., Brewin, C. R., Bryant, R. A., Cloitre, M., van Ommeren, M., Jones, L. M., … Reed, G. M. (2013). Diagnosis and classification of disorders specifically associated with stress: Proposals for ICD‐11. World Psychiatry, 12(3), 198–206. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20057

- Mancini, A. D., Bonanno, G. A., & Clark, A. E. (2011). Stepping off the hedonic treadmill: Latent class analyses of individual differences in response to major life events. Journal of Individual Differences, 32(2), 144–152. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-0001/a000047

- Marques, L., Bui, E., Leblanc, N., Porter, E., Robinaugh, D., Dryman, M. T., … Simon, N. (2013). Complicated grief symptoms in anxiety disorders: Prevalence and associated impairment. Depression and Anxiety, 30(12), 1211–1216. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22093

- Mckee‐ryan, F., Song, Z., Wanberg, C. R., & Kinicki, A. J. (2005). Psychological and physical well‐being during unemployment: A meta‐analytic study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1), 53–76. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.1.53

- Miller, M. A., & Rahe, R. H. (1997). Life changes scaling for the 1990s. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 43(3), 279–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(97)00118-9

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus user's guide (8th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

- Papa, A., & Lancaster, N. (2016). Identity continuity and loss after death, divorce, and job loss. Self and Identity, 15(1), 47–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2015.1079551

- Papa, A., Lancaster, N. G., & Kahler, J. (2014). Commonalities in grief responding across bereavement and non‐bereavement losses. Journal of Affective Disorders, 161, 136–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.03.018

- Papa, A., & Maitoza, R. (2013). The role of loss in the experience of grief: The case of job loss. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 18(2), 152–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2012.684580

- Paul, K. I., & Moser, K. (2009). Unemployment impairs mental health: Meta‐analyses. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74(3), 264–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.01.001

- Prigerson, H. G., Shear, M. K., Newsom, J. T., Frank, E., Reynolds, C. F., III, Maciejewski, P. K., … Kupfer, D. J. (1996). Anxiety among widowed elders: Is it distinct from depression and grief? Anxiety, 2(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1522-7154(1996)2:1%3C1::AID-ANXI1%3E3.0.CO;2-V

- Shear, M. K., Simon, N., Wall, M., Zisook, S., Neimeyer, R., Duan, N., … Keshaviah, A. (2011). Complicated grief and related bereavement issues for DSM‐5. Depression and Anxiety, 28(2), 103–117. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20780

- Simon, N. M., Shear, K. M., Thompson, E. H., Zalta, A. K., Perlman, C., Reynolds, C. F., … Silowash, R. (2007). The prevalence and correlates of psychiatric comorbidity in individuals with complicated grief. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 48(5), 395–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.05.002

- Smid, G. E., Kleber, R. J., de la Rie, S. M., Bos, J. B. A., Gersons, B. P. R., & Boelen, P. A. (2015). Brief eclectic psychotherapy for traumatic grief (BEP‐TG): Toward integrated treatment of symptoms related to traumatic loss. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6(0), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v6.27324

- Stolove, C. A., Galatzer‐levy, I. R., & Bonanno, G. A. (2017). Emergence of depression following job loss prospectively predicts lower rates of reemployment. Psychiatry Research, 253, 79–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.03.036

- Taris, T. W. (2000). A primer in longitudinal data analysis. London: Sage.

- Van eersel, J. H. W., Taris, T. W., & Boelen, P. A. (2019). Development and initial validation of the job loss grief scale. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 32(4), 428–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2019.1619703

- Van eersel, J. H. W., Taris, T. W., & Boelen, P. A. (2020). Dataset ‐ Reciprocal relations between symptoms of complicated grief, depression, and anxiety following job loss: A cross‐lagged analysis [dataset]. Yoda. https://doi.org/10.24416/UU01-TJP4XG