Abstract

This article investigates the paradoxical outcomes of a mechanism to promote women's participation in payment for ecosystem services (). Focusing specifically on the Legal Representative position, I examine how gendered and generational power dynamics become reinscribed through this position and the various ways that this position is conceptualized, performed, and negotiated. To do this, I combine theoretical insights from feminist theories of subjectivity, political ecology, and forest governance with empirical evidence from a small case study of in Jalisco, Mexico. I find that the subjectivity of women within the case study both produce and are produced by gendered and generational differences that simultaneously both challenge and also maintain social‐spatial exclusions. Although this study is limited by its focus on the Legal Representative and a small sample size, such a focused case study sheds light on the social and spatial ways in which runs the risk of exacerbating already existing inequities.

Over the last decade, payment for ecosystem services (PES) has emerged as an important strategy for the sustainable management and conservation of natural resources, including forests. Born from environmental economic theory's concerns about how to internalize external costs, PES subsidizes local community members for natural resource protection and sustainable use. Most recently, new PES schemes, emerging in the form of Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+), utilize hybridized market‐state‐donor mechanisms in attempts to reduce carbon emissions and support “pro‐poor” development in forest communities. Mexico in particular is considered to be among the more advanced countries in their promotion of PES and pilot REDD+ programs, although Mexico proposes to use a suite of programs as part of their REDD+ strategy (Hall Citation2012; CIF Citation2014). However, the claim that PES is a more economically efficient means to achieve conservation raises important questions about the ability of these programs to also address a range of social equity considerations (for examples, Corbera and others Citation2007, Sommerville and others Citation2010, Daw and others Citation2011, McElwee and others Citation2014, Calvet‐Mir and others Citation2015).

Indeed, several studies have revealed the potential harm of PES projects. A survey of 287 PES‐type forest projects found that poor communities with inadequate political representation and property rights may not only be excluded from the market, they may also loose access to forest land (Landell‐Mills and Porras 2002). In another survey of World Bank PES projects with the dual goals of biodiversity conservation and poverty alleviation, only 16 percent made major progress on both objectives (Tallis and others 2008). Studies that document the tradeoffs in PES revealed that the environmental goals often outweigh or conflict with social goals and outcomes (McAffee and Shapiro Citation2010; Adhikari and Agrawal 2013). For example, restrictions on forest use have reduced household food security and income in some instances (Ibarra and others Citation2011; Osborne Citation2011; Beymer‐Farris and Bassett Citation2012). Women and landless groups are often hardest hit by such tradeoffs (Boyd Citation2002; Molina and others Citation2014).

Looking at the benefits and tradeoffs of PES and REDD+‐related programs in Kenya, Juliet Kariuki and Regina Briner found that women's exclusion is tied to definitions of eligibility that are based on a narrowly defined definition of de jure property rights, which dismisses that different degrees of access to and claims over land that shape women's access and use of forest resources (2016). Although the literature that specifically examines the gender dynamics of PES is limited, a recent review of research on how gender is being addressed within pilot REDD+ programs found that despite policy rhetoric to the contrary, women`s actual participation and access to decision‐making spaces in these programs are limited (Bee and Basnett 2016). In particular, limiting their participation results in increasing women's workloads, discouraging them from raising concerns, and restricts their access to direct benefits from such programs (see also Khadka and others 2014; Westholm and Arora‐Jonsson Citation2015).

Amidst such concerns, and given that PES‐type programs may serve as the basis for REDD+ programs, new global agreements require countries to address issues of gender equity, among other things, in local programs. As Mexico is hailed as a leader for addressing gender in early REDD+ activities, we need a better understanding of how existing PES schemes address gender and the material outcomes of these social dynamics. To date, very few if any analyses exist. Such inquiries are exactly what feminist scholars suggest are needed for a more robust understanding of climate change mitigation policy (MacGregor Citation2010; Cuomo Citation2011).

This article, therefore, explores the material outcomes of incentivizing women's participation within a PES program in Mexico. Specifically, the PES program under study in this article incentivizes women's participation by awarding additional points to applications that have a female Legal Representative or someone who is elected by their community to sign documents and receive payments associated with the program. Therefore, I examine the ways that the subjectivity of the Legal Representative is negotiated by various actors within PES and how this subjectivity enables or constrains meaningful participation for women in the program. To do this, I combine feminist theories of subjectivity, political ecology, and forest governance with a small case study from the western highlands of the Mexican state of Jalisco. In the course of my analysis, I demonstrate how the performance of the subjectivity of Legal Representative produces and is produced by gendered and generational power dynamics that paradoxically both challenge and also maintain social‐spatial exclusions.

Although this study is limited by its focus on the Legal Representative and a small sample size, such a focused case study sheds light on important questions about the gendered spaces of PES and therefore REDD+, which are important to consider for policy makers and practitioners hopeful that REDD+ can bring about simultaneous sustainable and social development. I also hope to draw attention to the ways in which PES, and the suite of REDD+ programs currently being implemented in Mexico, run the risk of exacerbating already existing gendered and class‐based access to forest‐governance spaces. Analyzing women's participation in this way demonstrates how gendered power relations are mutually constituted and embedded within environmental‐development programs such as PES.

Women and Forest Governance

The scholarship on gender and forest governance argues that, in general, women experience far more barriers to participation than men (Jackson and Chattopadhyay Citation2000; Gupte Citation2004; Benjamin 2010; Sunam and McCarthy Citation2010). Collectively, studies that document such participation demonstrate that the nature and level of women's participation can have significant impacts on both equity and efficiency. For example, despite the existence of formal rules that support more gender equitable participation between men and women, several studies have shown that prominent inequalities persist in forest use and/or management (Banana and others Citation2012; Mukasa 2012). Indeed, institutional and socioeconomic factors like wealth and education are significant predictors of women's participation in forest governance (Coleman and Mwangi Citation2013). On the other hand, several studies show that women can also be perpetrators of environmental degradation if women do not have secure property rights and the associated incentives to invest in land and natural resources (Agarwal Citation1994; Meinzen‐Dick and others Citation1997). This literature reinforces the notion that the diverse material contexts within which environmental relationships are embedded, such as women's livelihoods and their life‐cycle processes should be acknowledged.

The level of participation among women in forest user groups also depends a great deal on their acceptance by male community members and forest bureaucrats (Mohanty Citation2004). Seema Arora‐Jonsson, for example, illustrates that women's ability to reach‐out beyond the village level was in some instances restricted by men, as was the case in Sweden, or enabled by men, as was the case in India (2012). In Nepal, even women from communities with fairly egalitarian norms and high interactive participation of women in forest‐related decision‐making structures rely on men to act as intermediaries between themselves and forest officials (Sijapati Basnett Citation2008).

Consequently, these studies demonstrate that simply increasing the number of women in forest governance merely serves to instrumentalize women's participation, thus constructing participants as objects. Nor does such an arbitrary “add women and stir” approach lend itself to conservation or environmental sustainability.

Socio‐Environmental Subjectivity: Feminist Interventions

Feminist theories of subjectivity provide a useful framework for exploring how gendered subjects come to being in the context of PES and forest communities in Mexico. Feminist theories of subjectivity have explored the ways in which people internalize and embrace identities like gender, and others that intersect with this category (Butler Citation1990; Rose Citation1993; McDowell Citation1999; Longhurst Citation2003). For the purposes of this article, I view identity and subjectivity as distinct, whereby subjectivity is produced through the discursive and material social‐spatial relations of power. Subjectivity is related to identity in that it is based upon one's understanding of the self, but it also encompasses the power‐laden aspects of social context and how the sense of self may change in relation to changing circumstances (Morales and Harris Citation2014). Subjectivity does not have predetermined characteristics but, rather, results from socio‐spatial interactions, and can shift across time and space. Indeed, subjectivity is based upon embodied experiences derived from being and performing in a specific place, but also the way in which others perceive and interact with the subject. For example, in the context of natural resources management, Nightingale describes how the subjectivity of “fishermen” shifts in space, so that they may be revered as an important economic contributors within their own community, they are regarded as culprits of resource overexploitation within policy‐making and scientific spaces (2013). My understanding of subjectivity, therefore, is informed by poststructuralist thinking that conceptualizes power and subjectivity as multiple, unstable, and constituted by social relations that include gender, but also age and class, among other things.

Feminist scholar's attention to embodied experience and knowledge production is also useful for drawing attention to the ways that female bodies and their experiences are products of both the material and social relations within which they are embedded. Judith Butler, in particular, writes that the body is governed by various external discursive regulatory practices, but it can also be governed by the materialness of the body itself in terms of ability, age, and the like (1990). Thinking about embodied subjectivity in this way draws attention to the ways that subjectivities are not abstract notions but lived and enacted in bodies, in spaces, and through practices. In the context of gender and the environment, such theorizing has significantly shifted the analysis of gender from being something that structures peoples responses to environmental change and roles in resource management, to emphasizing the ways through which environmental change brings various categories of social difference, “natural” spaces, and ways of being into existence, including gender among others (Schillington Citation2008). “Gender itself is re‐inscribed in and through practices, policies and responses associated with shifting environments and natural resource management” (Resurreccion and Elmhirst 2008, 9). Recent work in feminist environmental geography and political ecology has furthered thinking about the ways in which gendered subjectivities and identities are produced, enacted, and negotiated within environmental contexts (Elmhirst Citation2011; Hawkins and Ojeda 2012).

While early work in feminist political ecology (FPE) was grounded in more overtly structural arguments, recent work has been influenced by poststructuralism and therefore turns its attention toward discursive socio‐environmental practices. Recent FPE scholarship illustrates how gendered subjectivities and environments are coproduced through everyday material practices (Sundberg Citation2004; Harris Citation2006; Mollet 2006; Sultana Citation2009; Nightingale Citation2011). In Mexico, for example, Claudia Radel's work has been important for showcasing how women's socio‐environmental subjectivity and identity is embedded in a complex arrangement of resource access, livelihood struggles, and conservation projects (2012). This work has provided important theoretical interventions into understanding subjectivity as dynamic, shifting, and produced in relation to social, spatial, and environmental phenomena. This scholarship also draws on feminist science studies and geographers who theorize socio‐natural relationships more broadly as both discursively and materially produced (Haraway Citation1992; Swyndedouw Citation1999; Castree and Braun Citation2001).

Drawing on the work of feminist political ecologists, I argue that greater attention needs to be paid to the ways that gendered, embodied subjectivities, and inequalities are (re)‐produced, enacted, negotiated, and/or contested through policies and practices of forest management. In other words, PES can be seen as a spatial practice that is produced in the offices of environmental economists and forest “experts,” and enacted in the spaces of particular forests of particular communities. It is within these spaces and processes that the socio‐spatial relations of power within which gender and age are embedded and co‐constituted. These interactions produce contrasting performances of the Legal Representative position.

PES and Gender in Mexico

Mexico has widely integrated environmental economic theory into state‐led environmental policies, in an attempt to develop markets for foreign investment and support local communities (examples: Alix‐Garcia and others Citation2005; Taylor and Zabin Citation2000; Muñoz‐Piña and others Citation2008; Corbera and others Citation2009). Although the original intent of PES in Mexico was to create markets for foreign investment, the Mexican PES program has taken the form of a more hybridized federal subsidy to support forest conservation and rural poverty alleviation (Shapiro‐Garza Citation2013). Payment is based on forest type, and recipients are paid a flat $ pesos/ha/year (US$21 ha/yr.) for five years.Footnote1 Eligibility for payments often depends upon the community's ability to carry out “good forest management practices,” as defined by the state, including fire mitigation and grazing controls (CONAFOR Citation2012c). In contrast to many countries where forested land is held privately or by the state, the vast majority of Mexican forests are managed collectively by ejidos and comunidades (Klooster Citation2003; CONAFOR Citation2008) Both these communal tenure systems emerged in the decades following the Mexican Revolution (1910–1917). Although comunidades are often considered more “indigenous” than ejidos, this is by no means always true (Kelly and others Citation2010). Between 2003 and 2011, roughly 5967 ejidos, comunidades, and private property owners enrolled in PES, resulting in 3.4 million hectares being included in the program (Shapiro‐Garza Citation2013).

In 2011, PES was made available to specific municipalities in the state of Jalisco as part of a broader umbrella program called the “Special Program for the Coastal Watersheds of Jalisco” (Cuencas Costeras),Footnote2 which was developed as a REDD+ early action strategy that Mexico implemented to comply with UNFCCC requirements (SEMARNAT INECC Citation2012). This program, with financing from the World Bank, was established to address deforestation and forest degradation, build the capacities of rural communities, improve the quality of life of rural residents, and promote sustainable development (CONAFOR Citation2011a; CONAFOR Citation2012b; CONAFOR 2013). The program was a first step toward consolidating programs within the National Forestry Commission (CONAFOR) that meet the broad goals of REDD+. Since 2011, the program has expanded from only eleven eligible municipalities to thirty‐five in 2014 (CONAFOR Citation2011b: CONAFOR Citation2015b). These experiences serve to test which strategic actions and issues — environmental and social—at different scales offer the best possibility to effectively realize the aspirations of REDD+ for the country and to replicate this process in other places (Franco de la Peza Citation2013).

It is important to note that the decision to participate in the Coastal Watersheds program, or any conservation or forestry program, must be discussed and agreed upon by the ejido assembly (asamblea), or governing body. Anyone may attend an ejido assembly, but only ejidatarios have the right to vote so meetings are typically attended only by ejidatarios. Nationally, only 19.8 percent of ejidatarios are women (INEGI Citation2007), which means that the assembly is a male‐dominated institution. Furthermore, the overwhelming majority of women who are ejidatarias are over sixty‐five years old (Procuraduría Agraria Citation2009). The stark contrast between women and men with titled landholding reflects several aspects of state policy that has historically impeded women's ability to acquire land of their own, as well as patrilineal inheritance practices within families.

Gender relations in rural Mexico are often built upon male control of land and decision making. As a consequence, much of the scholarship on gender in rural Mexico has focused on the effects of neoliberal restructuring that brought about an end to the period known as “agrarian reform” and changed land‐titling practices (Stephen Citation1996). As part of economic restructuring, Article 27 of the Mexican Constitution was reformed in 1992 and established the land‐titling program (PROCEDE, and it's predecessor FANAR). Although diverse outcomes exist, PROCEDE provides a means to map the boundaries of ejidos and the opportunity for ejidatarios to have individual, legal title to their fields, allowing them to legally rent, sell, or use their land as collateral. Prior to this reform, and indeed for ejidos that have not undergone the PROCEDE titling process, each ejidatario has a “certificate of agrarian rights,” which certifies their right to the use and enjoyment of agricultural fields and areas of common use, which include forest spaces, although diverse outcomes exist. Although land sales existed before PROCEDE, the hope was that by privatizing land and, thus, creating a market for land sales, there would be an increased flow of investment in agriculture.

Some authors argue that land titling may increase women's vulnerability to dispossession and disinheritance, as family usufruct land (held largely in men's names) transitions into individual (primarily male‐owned) private property (see Deere and Leon Citation2001). Sarah Hamilton, on the other hand, has shown that in some instances, the counterreforms actually resulted in reinforcing the validity of women's individual claims to land and increasing their control of family lands (2002). As Lynn Stephen has also shown, women's responsibility for procuring household goods, administering household budgets, and the range of strategies they have employed in order to take care of their families suggests that women's “individual responses” to economic hardship in Mexico is only one way that they are coping with economic restructuring (2005).

Yet women's exclusion from formal property rights and therefore the right to vote in assembly meetings leads to other exclusions in forest‐governance contexts. As Verónica Vázquez‐García demonstrates, even if women want to participate in workshops about federal programs, they are not invited because they do not have formal property rights (2015). Furthermore, the handful of studies that specifically focus on gender dynamics in forests collectively showcase that women's limited control over land often results in limiting their participation in forest‐governance spaces (Radel Citation2005; Velázquez 2005; Lara‐Aldave and Vizcarra‐Bordi Citation2008; Vázquez‐Garcia Citation2015). It is also widely known that productive forestry activities (that is, timber harvest), throughout Mexico and at all scales (local‐national) is also a highly masculinized space and practice (Vázquez‐Garcia Citation2015). So although land tenure and formal property rights are not the only factors that limit women's participation, they significantly influence the degree to which women are not only able to access forest resources, but also able to participate in decision‐making regarding such resources. Esteve Corbera and others, for example, found that one particular PES program in Mexico excluded women from project meetings, despite their active role in managing forest commons as fuelwood gatherers (2007). As a result, their desire to plant a particular species of tree for fuelwood was ignored in favor of a timber‐oriented species, which benefit men's interests (Corbera and others Citation2007). It is within this context that CONAFOR incentivizes participation in the Coastal Watersheds program for women through the specific position of Legal Representative within the program. As I demonstrate below, the enactment and negotiation of the Legal Representative subject demonstrates both the opportunities and constraints to more inclusive forest governance policy and practice.

Study Site and Methods

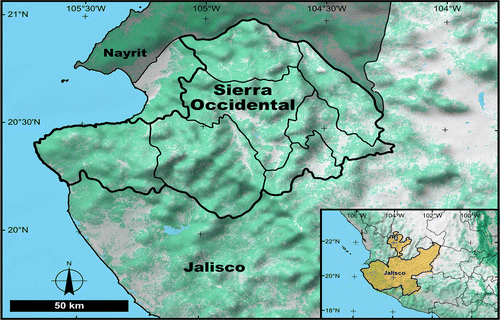

The empirical analysis I present is drawn from a small case study conducted in the Sierra Occidental of Jalisco, Mexico (Figure 1). Jalisco was selected as the study site as it was one of three specific early REDD+ action areas, defined by CONAFOR, where early REDD+ activities took place. Within Jalisco, the Sierra Occidental is one of four regions in the state that comprise the Coastal Watersheds program. The Legal Representatives whose experiences form the crux of my argument here are also from ejidos who were beneficiaries of PES within the Coastal Watersheds program and who had been previously been receiving PES through the national program.

Each ejido included in this study is divided into three areas: agricultural parcels, uso comun (which includes forest areas), and urban settlements. The uso comun areas are where each ejidatario is allowed to graze cattle, and can collect wood for fuel, furniture, and fence posts, as well as other nontimber‐forest‐products such as seasonal mushrooms. Women in the communities are typically responsible for gathering fuelwood and mushrooms, while men are responsible for grazing cattle and collecting wood for fences or furniture. Sometimes this wood is collected outside of the uso comun areas, within one's own agricultural parcel, as most ejidatarios in this region practice shifting cultivation, so parts of their parcels are fallow or partially forested most years. Access to the uso comun areas are technically only granted to ejidatarios and their families, meaning that other residents of the ejido without land and ejidatario status needs to ask permission from the ejido assembly to access the uso comun areas, which include the forest commons. Although there can be variation to this rule, this was not the case in the ejidos included in this study. Two of these ejidos have PROCEDE titles and, therefore, the ability to legally sell land with the permission of the ejido. As the transition to the full privatization happens in three stages within PROCEDE, one of these ejidos has simply mapped the boundary of the ejido, while the other has individual titles to their agricultural parcels. While the third ejido does not have PROCEDE, each ejidatario has a certificate of access to common‐use lands, which include forest resources and agricultural parcels.

State interventions in the forest commons happen when and if there is a forest fire, and any illegal logging is reported, of which neither had occurred in either of the ejidos included in this study for some time. More commonly, the relationship between the state and the ejidos, in terms of forest governance, occurs in the form of subsidies and monitoring from the national and regional offices of CONAFOR. In addition to receiving PES through the Costal Watersheds program, two of the ejidos in this study also receive a number of other benefits from CONAFOR, including financial assistance for timber extraction, reforestation, and territorial zoning, which is intended to map‐out land use within ejidos. One of the ejidos is also a member of the Mexican Coffee Association. Although both men and women are involved in the coffee cooperative, there are no women, outside of the Legal Representative, who is involved in or directly receiving benefits from CONAFOR's programs in any of the ejidos included in this study.

From May‐August 2013, I conducted a combination of interviews, participant observation, and document analysis. During this time, I completed a total of fifteen semistructured interviews with various actors involved in the regional PES program. This included two female Legal Representatives from ejidos that were currently beneficiaries of the program. Although I attempted to interview a third Legal Representative, I was unfortunately not granted permission to do so for reasons I explain below. I also conducted interviews with three ejido presidents from the same ejidos as the Legal Representatives, three officials from the regional, state, and national CONAFOR offices (one person from each), and seven forest technicians (or técnicos) working in the region, all of who were male. The técnicos are certified by CONAFOR and act as intermediaries between CONAFOR and ejidos to help facilitate and manage these programs locally. They also facilitated my access to local ejidos.

These interviews and interactions happened in a variety of contexts. Interviews with CONAFOR staff took place in their offices and largely centered on understanding the history and organization of the Coastal Watersheds program. The majority of interviews with técnicos also took place in their offices, while one or two occurred on the road between visits to ejidos, or on one occasion, in the regional CONAFOR office because the only time he had available was after dropping of some paperwork. These interviews focused on the role of the técnicos themselves in PES and their relationship with the ejidos. The interviews with ejido presidents, regarding their decision to enter into PES and their opinion about women in the program, took place in the ejido, usually in the Casa Ejidal, or the main meeting room for the ejido. My interviews with the Legal Representatives regarding their role in PES also took place in the Casa Ejidal.

In addition to interviews, I also conducted participant observation during several meetings and workshops hosted by CONAFOR about PES, REDD+ early action initiatives, and a host of other CONAFOR programs being carried out in the region. Lastly, I reviewed documents related to PES in Mexico, including the rules and obligations of the specific program under investigation, paying particular attention to the role of gender as a category of analysis.

Incentivizing Women's Participation in PES: CONAFOR

From 2007–2012, the Secretary of the Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT), which oversees CONAFOR operations, promoted the program, “Towards gender equality and environmental sustainability,” with a specific emphasis on mitigation and adaptation to climate change (SEMARNAT Citation2008). The gender equality program placed overwhelming emphasis on women's productive roles in forest communities as a means to enhance their participation and contribution to adaptation and mitigation of climate change effects. To promote gender equality, SEMARNAT prioritized “gender, indigenous people, and youth” as part of the Adaptation and Mitigation to Climate Change, which included the recent restructuring of CONAFOR conservation programs, like Coastal Watersheds, as part of early REDD+ activities. Additionally, Mexico's National REDD+ Strategy explicitly states an interest promoting and guaranteeing the participation of women and other specific groups through access to credit (ENAREDD+ Citation2015).

CONAFOR first began incentivizing women's participation in PES in 2010 in the national PES program, the year prior to the start of the Coastal Watersheds program. Both the national PES program and Coastal Watersheds utilize the same incentive structure. The incentive comes in the form of points for electing a Legal Representative for the ejido from social sectors. Specifically, each application is awarded four extra points if the Legal Representative is a woman. Applications can garner an additional four points if the Legal Representative is between the ages of eighteen and twenty‐five, and an additional four points if the community has indigenous residents (CONAFOR Citation2015b).Footnote3 So, if the Legal Representative is a young woman from an indigenous community, then theoretically, applications can receive an additional twelve points. The points‐based system is currently the only incentive for women's participation in PES programs.

The CONAFOR Rules of Operation (2014) regarding the participation of Legal Representatives in the program are quite limited. In fact, the only requirements are that the Legal Representative is elected by their community, is able to receive payments, and will be responsible for the signing of documents (CONAFOR Citation2015b). Such a limited conceptualization lends itself to the discursive formation of a subject that is quite ambiguous in practice.

Once an application is completed by the forest técnico and signed by the Legal Representative, the técnico then submits the application to a regional CONAFOR office. These applications are then passed along to the national office where a technical committee decides the awardees every year. According to CONAFOR, successful applications are based on program eligibility and the accumulation of points. To be eligible for the Coastal Watersheds program, only ejidos and comunidades located in municipalities that comprised the Early REDD+ Action Areas in Jalisco were eligible. As mentioned above, successful applicants are paid a flat $382 pesos/year (US$21/yr) for each hectare enrolled in the program, for up to five years. On average, CONAFOR approves only 10‐12 percent of any application submitted for PES, making these programs highly competitive. Due to the competitive nature of these programs, CONAFOR would only state officially that unsuccessful applications were rejected because of errors in the application itself.

The técnicos are an essential component to the success of the application and to the program itself as they interpret and facilitate the management plan for PES. In addition, they also play a critical role in interpreting and implementing CONAFOR's incentive for increasing women's participation in the program. The tecnico′s interpretation and attitudes contributes to the discursive process through which the Legal Representative subject emerges.

Essentializing Women's Participation in PES: The Técnicos

One of the forest técnicos, Don Barbito,Footnote4 recalled that when CONAFOR implemented the incentive of nominating women as Legal Representatives, he and his associates held several meetings with communities to discuss the new incentive with them and to persuade them to nominate a woman. He and his team emphasized the benefits of receiving more points when the projects were evaluated so that the applications stood a better chance of success. Don Barbito continued to emphasize this point when working with communities and indeed, each community for which he was the forest técnico, had a woman as a Legal Representative.

Another forest técnico who works with Don Barbito, Macias, commented that nominating a woman to be a Legal Representative reflected the ejido's internal socially progressive nature. “In rural contexts, it is difficult to convince men of the importance of women′s participation in the ejidos. In this territory (Sierra Occidental) there is a lot of machismoFootnote5 and very few opportunities for women to participate” (Macias). Macias also valued the action as a means for women to improve work skills and the ability to organize their communities. The role of the Legal Representative, according to Macias, was not simply to sign papers, but also to provide good ideas. For example, he recalled occasions in which communities needed to carryout a particular task and the women were more easily persuaded. “They are good facilitators and managers,” Macias commented. But none of the ejido residents I spoke to and only a couple of the técnicos envisioned a more transformative role for women serving as Legal Representatives for their communities.

In fact, the benefit of additional points for applications was a common response by the ejidos, CONAFOR staff, and the técnicos when asked what benefits they believed such a strategy had, even if they themselves did not actively promote it. Another técnico, Enrique, explained that as Legal Representatives, they often act as secretaries or treasurers for the mesa directiva (general board). He valued women's participation because they were more organized and careful with monetary resources, unlike some of their male counter parts. When I asked what benefits he saw including women might have (or has had so far), instead of a high‐minded philosophical answer about transforming society, his response was a pragmatic: “they get additional points.” Interestingly however, he was under the impression that the extra points were awarded for communities with women ejido leaders, not specifically for the position of Legal Representative for the program. As a consequence, he did not actively promote the additional benefit of female Legal Representatives among his communities. In fact, none of the communities he worked with had a female Legal Representative, although a handful had women who participated in the governance of the ejido (as secretary or treasurer). Enrique was also very careful to explain that his role is not to interfere in the business of the ejido itself. “If they want to elect a woman to serve as their Legal Representative, that is their business, but as a técnico, I cannot influence that decision.”

Fausto, who worked in the same consultation office as Enrique and was considered by his peers and by CONAFOR to be incredibly professional, did not work with a single community who had a female Legal Representative. In fact, none of the communities that were included in the combined portfolio for the consultancy had a female Legal Representative. Fausto believed CONAFOR had been promoting such things for at least the past eight years, and found women to have excellent administrative skills. He told me of a time when it was women who were able to resolve a conflict among several community members that was preventing them from complying with the requirements of the program. “They always find a solution, they're very participatory, and always have a vision of family that gives them a balance between reason and their heart and they use both.” Nevertheless, despite his positive view of women for their administrative and conflict negotiation skills, he, like Enrique, did not actively promote their participation. In other words, in contrast to Don Barbito and Macias, neither Fausto nor Enrique tried to influence the decision making of the ejido in selecting a female Legal Representative, nor did they advise including them in other ways.

How the técnicos envision women's participation in PES reflect broader development discourses about the benefits of women's participation. In the examples here, women are valued for their administrative and their dedication to their family. This is not that dissimilar from the ENAREDD document's suggestion that women should be provided increased access to credit. Although it does not specifically state why, it can be inferred that such ideas plays into old stereotypes about women's repayment rates (Rankin Citation2001). Enrique, in fact, is explicit about his ideas that women make good financial managers. Yet regardless of how the técnicos envisioned women's participation, the point is that none of them envisioned or much less facilitated a more transformative role for women in the program. As the feminist literature on forest governance demonstrates, simply increasing the number of women in forest governance merely serves to instrumentalize women's participation. Moreover, the ambiguity of the rules that determine the roles and responsibilities of the Legal Representative did not help either.

Performing Participation in PES: The Legal Representatives

When I asked the president of the ejido of La Cabra what he thought the role of the ejido's female Legal Representative was, he bluntly explained that her role was a means to an end. “Honestly, she was named as the Legal Representative so we could get points. She is a young female, so we were able to get points because she is a woman, and because she is young. She signs papers, and goes to the bank. Her father was furious that we even nominated her, but we managed to convince him that it would benefit the whole community. He doesn't let her out of his sight, so she has no real influence on anything we do.” When I later asked the técnico what he thought of the situation he told me, “She is a puppet.” As a reflection of how tightly guarded her participation was, I never saw her at any of the ejido assembly meetings or CONAFOR meetings and I was unfortunately unable to interview her myself.

The staff of the national CONAFOR offices acknowledged that this is a problem. “Yes, we have heard that in many cases, the points incentive results in simply naming a woman or a young person to be the Legal Representative, without really including them in the program. So she is the Legal Representative in name only and the application gets the extra points, but she has little to do with the program. But at the same time there are instances where women are named to be Legal Representatives and are very active in the program.” When I pressed the CONAFOR staff further, they also acknowledged that most of the women who they've seen are very active are also often older women whom have very supportive families and ejido members by their side.

One of these women I met was Doña Gabriela, the Legal Representative for Emiliano Zapata, a fifty‐seven‐year‐old ejidataria who was present at every meeting and very active in the program and in her ejido. She took her position very seriously and commented to me that as the Legal Representative, she not only received these payments, but also to attended CONAFOR meetings as a representative of the ejido. She spoke very highly of the forest técnico for the ejido, explaining that he has been their técnico since 2003 and has been very helpful to them. She also spoke highly of CONAFOR staff explaining that in her experience, everyone is very accessible and clear. In fact, she feels that the PES program has been instrumental in influencing a more “environmental” and conservation‐oriented mindset among community members. When I asked how she came to be the Legal Representative, she explained that like La Cabra, her ejido, Emiliano Zapata, decided to nominate a woman to serve as Legal Representative because of the extra points they could get. However, unlike La Cabra, the ejidatarios of Emiliano Zapata elected Doña Gabriela because she was already a willing and active member of the ejido. As a consequence, instead of being instrumentalized, she has fully embraced her role as an active participant and utilizes the opportunity to realize her participation within the program. However, it is important to note that this opportunity is afforded to her because of her status in the ejido as an ejidataria—a landed class that few women occupy, and those that do are often of advanced age.

Doña Gabriela's experience is very similar to that of Doña Patricia, an ejidataria from the ejido of El Cafecito. Doña Patricia, a widow in her mid 60s, became an ejidataria when her husband died and she inherited his land and became a voting member of the ejido. Since she became an ejidataria, she has never missed an assembly. Doña Patricia was also elected to be the Legal Representative as she was also a very active member of a local coffee cooperative, and has experience working with the range of actors that participate in the cooperative: other ejido members, government officials, donors, students, private consultants, and business owners, among others.

Like Doña Gabriela, Doña Patricia is part of only 12 percent of individuals in her community who are ejidatarios who not only have access to land, but also have full agrarian rights to that landFootnote6 and to vote in assembly meetings. Doña Patricia is very proud to be so active in her ejido and has not yet encountered difficulty in working with her técnico, or with CONAFOR, or with male ejido members. “No, they know who I am [referring to the men in her ejido] and I don′t tolerate their nonsense.” When I asked the técnico for her ejido, Don Barbito, about the social status of the Legal Representatives he works with, he responded that all of them are ejidatarias. This is in stark contrast to the woman from La Cabra, who is not. The fact that Doña Patricia and the other active Legal Representatives are ejidatarias is evidence of the uneven power dynamics within ejidos as ejidatarios have more rights than other residents. As the feminist literature on forest governance showcases, women without land or voting rights, as is the case of the woman from La Cabra, are less likely to participate in meaningful ways (Radel Citation2005; Velázquez 2005; Lara‐Aldave and Vizcarra‐Bordi Citation2008; Vázquez‐Garcia Citation2015). Understanding how women's subjectivity intersects with and is produced in relation to land tenure is significant for understanding the exclusionary politics of gendered power relations not only in local communities, but also in CONAFOR policy.

Discussion and Conclusions

The results of this study point to the varied and complex ways in which various actors within the Coastal Watersheds PES program negotiate the subjectivity of the Legal Representative. Utilizing the feminist literature on subjectivity, political ecology, and forest governance, this paper sought to highlight how the complex, and at times conflicting performance of the Legal Representative reflects the socio‐spatial relations of power that are embedded within their communities and between the actors involved. It also sought to draw our attention to the ways in which the promotion of gendered and generational subjectivities can exacerbate already unequal socio‐natural relationships in forest settings, creating opportunities for some, and exclusions for others.

Feminist theories of subjectivity and political ecology provide a useful framework for understanding the process of subject formation as embedded in a complex arrangement of resource access and control within CONAFOR programs and forest governance. Within the context of PES, gender and its associated power dynamics become reinscribed through the Legal Representative category and the various ways in which this position is performed, contested, or negotiated. In the case I present, we can see that the level of participation by women in what is an otherwise masculine space is a product of the gendered and generational social relations within their communities. So while older, ejidataria women may have full access to governance spaces, they are at the same time reproducing gender norms and ideas about women's subjectivity held by CONAFOR staff, forest técnicos, and ejido members that their value resides in their administrative and interpersonal skills. At the same time, a closer examination of the practice reveals the ways in which women become an instrument through which conservation programs are made available to their communities.

Through the points‐based incentive for all applications, CONAFOR constructs women as instruments through which communities gain access to funding and programs. Both the instrumental construction of these gendered subjects as a means to an end, and their enactment are produced through the lack of clarity on the part of CONAFOR, the forest técnicos, and ejido leadership regarding how this enactment should take place. In the case of the ejido La Cabra, this manifests in the election a young woman who merely serves as a means to gain points for those who elected her and those who condone this practice. Her voice is not present in this study because those around her tightly guarded her participation in her community, in PES, and her access to me. Despite my persistent requests to speak with her, neither the forest técnico, nor the ejido president, nor her father would allow it. As a result, we are left to guess how she might envision her own subjectivity within such a scenario. Approaching this scenario through the lens of subjectivity demonstrates how her subjectivity is discursively and materially produced, and enabled by family and community members as well as forest técnicos who represent the key point of contact for facilitating such opportunities. How she herself, adopts, contradicts, or contests such subjectivity, unfortunately remains unknown.

The cases of Doña Gabriela and Doña Patricia stand in stark contrast to the young woman from La Cabra, reflecting the uneven power dynamics present both within these communicates and within the PES program that are both gendered and generational. Unlike their counterpart, Gabriela and Patricia, as older women with land and voting rights in their ejidos, are able to contest predominantly masculine spaces of forestry and conservation to construct their own version of what women's participation can and should look like. However, both the women's age and status as ejidatarias afforded them the opportunity to do so.

Nevertheless, one might question the extent to which the performance of the Legal Representatives’ subjectivity challenges the socio‐spatial gendered norms of the forestry sector. Clearly, in the case of Gabriela and Patricia, as active representatives and administrators of CONAFOR programs, it does. Yet, while women's household or community responsibilities may very well take them into the forest space for any number of reasons, their subjectivity as Legal Representatives does not. Both the requirements of the position, as determined by CONAFOR and the attitudes of the forest técnicos, like Don Barbito and others, discursively relegate women's socio‐spatial contribution to the Coastal Watersheds program through merely administrative terms. Feminist political ecology and theories of subjectivity draw our attention to the ways that the practice of the Legal Representative and PES policy reinscribe gender by relegating “women's work” to administrative spaces, regardless of the extent of participation—whether it be instrumental or active. Furthermore, this discursive exclusion of women from forest governance is largely based in forest management systems that privilege the commercial production of timber, ignoring the needs and interests of women (Vázquez‐Garcia Citation2015). For the case study I present, the question remains as to what extent the promotion of female Legal Representatives provides an opportunity to challenge the dominant ideology of gendered relations and decision‐making and for which women this opportunity exists.

In the case presented above, the forest técnicos had a great deal of influence over whom the community should consider to elect as Legal Representative. This is consistent with other studies that demonstrate how male community members and forest officials influence women's participation in forest governance (Mohanty Citation2004; Sijapati‐Basnett Citation2008; Arora‐Jonsson Citation2012). The three communities that participated in this study all had female Legal Representatives and all of them worked with male técnicos who encouraged this practice. The forest técnicos I spoke to on the other hand who did not encourage the practice (or in some instances, even know it existed) did not work with any female Legal Representatives. However, beyond the points‐based incentives, técnicos had no other incentive to promote gender inclusivity within the program. As we saw in the case from the Legal Representative from La Cabra, as a young woman without land and the right to vote in community meetings who lacked the support of male community members, her participation was only instrumental. While the older Legal Representatives from Emiliano Zapata and El Cafecito, on the other hand, who also had land and the right to vote, were active participants. Consequently, the degree to which women became involved in the program depended not only on the support of male community members and forest técnicos, but also upon their age and land‐tenure status within the communities.

This then enables the reproduction of both forest and ejido governance as exclusionary spaces to which younger and landless ejido members have very little access. Such exclusions have several implications for forest users to claim and benefit from forest programs that are linked to land tenure and property rights. For example, questions remain as to how economic and social benefits will be distributed, particularly if benefit distribution is tied to land tenure and property rights. As Esteve Corbera and others found, when PES projects do not account for informal property rights or forest resource users, they can induce social conflict and direct confrontation between forest users and project managers (2007). At the same time, excluding landless and young residents can result in decision making that favor the interests of residents with greater social and economic power, which simply reproduce existing power inequities between community members (Corbera and others Citation2007).

An obvious shortcoming of this study is the limited voices of women representatives and other women not included in forest management activities. However, this presents opportunities for future research to investigate the effects of PES programs, beyond the construction of the legal‐representative position. As there are no other studies that specifically focus on the gender dynamics of PES programs to date, such research can provide additional insights into ways in which conservation programs enable or constrain social equity.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Beth A. Bee

Dr. Beth A. Bee, Department of Geography, Planning and Environment, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC 27858; [[email protected]].

Notes

1. 1 hectare (ha) = approximately 2.5 acres.

2. Although Coastal Watersheds has the appearance of a new PES program, it is in fact based upon the national program. Thus all rights and responsibilities of beneficiaries, including the points system, are identical.

3. It should be noted that although it is the specific Coastal Watersheds program under scrutiny in this study, that all applications for all CONAFOR programs, including REDD+ early action programs, include the same points‐based incentives for applications (CONAFOR Citation2015a, Citation2015b)

4. All names are pseudonyms.

5. Although men and women throughout Latin America, and indeed social scientists, often use the terms “machismo” or “machista” to explain women's subordination in households and communities, such a term is not reducible to a coherent set of sexist ideas and practices (Gutmann Citation2006).

6. According to agrarian law, individual agrarian rights, available only to ejidatarios and comuneros (equivalent of an ejidatario within a comunidad), implies the right to inherit individual parcels and ejidatario status to family members, the right to participate and make decision in the ejido assembly, and the right to be elected to the ejido governing bodies (Procuraduría Agraria Citation2014). It also includes the right to receive government benefits associated with farming on the individual parcels. This right is afforded to ejidatarios regardless of the ejido has PROCEDE titles or not.

References

- Agarwal, B. 1994. Gender and Command over Property: A Critical Gap in Economic Analysis in South Asia. World Development 22 (10): 1455–1478.

- Agarwal, B. 2000. Conceptualising Environmental Collective Action: Why Gender Matters. Cambridge Journal of Economics 24 (3): 283–310.

- Alix‐garcia, J., A. de Janvry, E. Sadoulet, and J. M. Torres. 2005. An Assessment of Mexico's Payment for Environmental Services Program. Rome: United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

- Arora‐jonsson, S. 2012. Gender, Development and Environmental Governance. Florence, U.K.: Routledge.

- Banana, A., M. Bukenya, E. Arinaitwe, and B. Birabwa. 2012. Gender, Tenure and Community Forests in Uganda. Working Paper No. 87. Bogor, Indonesia: CIFOR.

- Beymer‐farris, B. A., and T. J. Bassett. 2012. The REDD Menace: Resurgent Protectionism in Tanzania's Mangrove Forests. Global Environmental Change 22 (2): 332–341.

- Boyd, E. 2002. The Noel Kempff Project in Bolivia: Gender, Power, and Decision‐Making in Climate Mitigation. Gender and Development 10 (2): 70–77.

- Butler, J. 1990. Gender Trouble. New York: Routledge.

- Calvet‐mir, L., E. Corbera, A. Martin, J. Fisher, and N.Gross‐camp. 2015. Payments for Ecosystem Services in the Tropics: A Closer Look at Effectiveness and Equity. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 14: 150–162.

- Castree, N., and B. Braun (eds.). 2001. Social Nature: Theory, Practice, and Politics. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Publishers.

- CIF [Climate Investment Funds]. 2014. Linkages Between REDD+ Readiness and the Forest Investment Program. Washington, D.C.: Climate Investment Funds. [http://www.climateinvestmentfunds.org/sites/default/files/knowledge-documents/linkages_between_redd_readiness_and_fip_nov2014_0.pdf ].

- Coleman, E. A., and E. Mwangi. 2013. Women's Participation in Forest Management: A cross‐country analysis. Global Environmental Change 23 (1): 193–205.

- CONAFOR [Comision Nacional Forestal]. 2008. Readiness Plan Idea Note. Guadalajara, México: Consejo Nacional Forestal.

- CONAFOR [Comision Nacional Forestal]. 2011a. Visión de México sobre REDD+. Hacia una estrategia nacional. Guadalajara, México: Consejo Nacional Forestal.

- CONAFOR [Comision Nacional Forestal]. 2011b. Lineamientos del Programa Especial Cuencas Costeras en el Estado de Jalisco. Guadalajara, México: Consejo Nacional Forestal.

- CONAFOR [Comision Nacional Forestal]. 2012a. Bosques, cambio climático y REDD+ en México. Guía básica. Guadalajara, México: Consejo Nacional Forestal.

- CONAFOR [Comision Nacional Forestal]. 2012b. Proyecto: Bosques y Cambio Climático (SIL‐FIP). Marco de procedimientos para restricciones involuntarias de acceso al uso de recursos naturales en Áreas Naturales Protegidas (MPRI). Guadalajara, México: Consejo Nacional Forestal.

- CONAFOR [Comision Nacional Forestal]. 2012c. Lineamientos del Programa Especial Cuencas Costeras en el Estado de Jalisco. Guadalajara, México: Consejo Nacional Forestal.

- CONAFOR [Comision Nacional Forestal]. 2015a. Linamiento de operación para el Programa Especial de Áreas de Acción Temprana REDD+. Guadalajara, México: Consejo Nacional Forestal.

- CONAFOR [Comision Nacional Forestal]. 2015b. Reglas de operación del Progama Nacional Forestal 2015. Guadalajara, México: Consejo Nacional Forestal.

- Corbera, E., C. G. Soberanis, and K. Brown. 2009. Institutional Dimensions of Payments for Ecosystem Services: An Analysis of Mexico's Carbon Forestry Program. Ecological Economics 68 (3): 743–761.

- Corbera, E., N. Kosoy, and M. Martínez‐tuna. 2007. Equity Implications of Marketing Ecosystem Services in Protected Areas and Rural Communities: Case Studies from Meso‐America. Global Environmental Change 17 (3–4): 365–380.

- Cuomo, C. 2011. Climate Change, Vulnerability, and Responsibility. Hypatia 26 (4): 690–714.

- Daw, T., K. Brown, S. Rosendo, and R. Pomeroy. 2011. Applying the Ecosystem Services Concept to Poverty Alleviation: The Need to Disaggregate Human Well‐Being. Environmental Conservation 38: 370–379.

- Deere, C. D., and M. León. 2001. Empowering Women: Land and Property Rights in Latin America, Pitt Latin American series. Pittsburgh, Pa.: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Elmhirst, R. 2011. Introducing New Feminist Political Ecologies. Geoforum 42 (2): 129–132.

- Elmhirst, R., and B. P. Resurreccion. 2008. Gender, Environment and Natural Resource Management: New Dimensions, New Debates. In Gender and Natural Resource Management: Livelihoods, Mobility and Interventions, edited by B. P. Resurreccion and R. Elmhirst, 3–22. London: Earthscan.

- ENAREDD+[Estrategia Nacional para la Redución de Emisiones por Deforestación y Degradación de Bosques y Selvas]. 2015. Estrategia Nacional para La Redución de Emisiones por Deforestación y Degradación de Bosques y Selvas: Síntesis para consulta pública. Guadalajara, México: CONAFOR.

- Franco de la peza, R. G. 2013. La gobernanza intermunicipal y la implementación de mecanismos REDD+ al nivel local. Guadalajara, México: CONAFOR.

- Gupte, M. 2004. Participation in a Gendered Environment: The Case of Community Forestry in India. Human Ecology 32 (3): 365–382.

- Gutmann, M. C. 2006. The Meanings of Macho: Being a Man in Mexico City. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Hall, A. 2012. Forests and Climate Change: The Social Dimensions of REDD in Latin America. Cheltenham, U.K.: Edward Elgar.

- Hamilton, S. 2002. Neoliberalism, Gender, and Property Rights in Rural Mexico. Latin American Research Review: 119–143.

- Haraway, D. 1992. The Promise of Monsters: A Regenerative Politics for Inappropriate/d Others. In Cultural Studies, edited by L. Grossberg, C. Nelson and P. Treicher, 275–332. New York: Routledge.

- Harris, L. 2006. Irrigation, Gender, and Social Geographies of the Changing Waterscapes of Southeastern Anatolia. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 24: 187–213.

- Hawkins, R., and D. Ojeda. 2011. Gender and Environment: Critical Tradition and New Challenges. Environment and Planning D 29 (2): 237–253.

- Ibarra, J. T., A. Barreau, C. Del campo, C. I. Camacho, G. J. Martin, and S. R. Mccandless. 2011. When Formal and Informal Market‐Based Conservation Mechanisms Disrupt Food Sovereignty: Impacts of Community Conservation and Payments for Environmental Services on an Indigenous Community of Oaxaca. International Forestry Review 13: 318–337.

- INEGI. 2007. Censo Agrícola, Ganadero, y Forestal. México, DF: Institución Nacional de Estadistica, Geografía e Informática.

- Jackson, C., and M. Chattopadhyay. 2000. Identities and Livelihoods: Gender, Ethnicity, and Nature in a South Bihar village. Agrarian Environments: Resources, Representations, and Rule in India: 147–169.

- Kariuki, J., and R. Birner. 2016. Are Market‐Based Conservation Schemes Gender‐Blind? A Qualitative Study of Three Cases From Kenya. Society and Natural Resources 29 (4): 432–447.

- Kelly, J. H., P. H. Herlihy, D. A. Smith, and A. Ramos viera. 2010. Indigenous Territoriality at the End of the Social Property Era in Mexico. Journal of Latin American Geography 9 (3): 161–181.

- Klooster, D. 2003. Campesinos and Mexican Forest Policy During the Twentieth Century. Latin American Research Review 38 (2): 94–126.

- Lara‐aldave, S., and I. Vizcarra‐bordi. 2008. Políticas ambientales‐forestales y capital social femenino mazahua. Economía, sociedad y territorio 8 (26): 477–515.

- Longhurst, R. 2003. Introduction: Placing Subjectivities, Spaces and Places. In Handbook of Cultural Geography, edited by K. Anderson, M. Domosh, S. Pile and N. Thrift, 282–289. London: Sage Publications.

- Macgregor, S. 2010. A Stranger Silence Still: The Need for Feminist Social Research on Climate Change. The Sociological Review 57: 124–140.

- Mcafee, K. 2012. The Contradictory Logic of Global Ecosystem Services Markets. Development and Change 43 (1): 105–131.

- Mcafee, K., and E. Shapiro. 2010. Payments for Ecosystem Services in Mexico: Nature, Neoliberalism, Social Movements, and the State. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 100 (3): 579–599.

- Mcdowell, L. 1999. Gender, Identity and Place: Understanding Feminist Geographies. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Mcelwee, P., T. Nghiem, H. Le, H. Vu, and N. Tran. 2014. Payments for Environmental Services and Contested Neoliberalisation in Developing Countries: A Case Study from Vietnam. Journal of Rural Studies 36: 423–440.

- Meinzen‐dick, R. S., L. R. Brown, H. S. Feldstein, and A. R. Quisumbing. 1997. Gender. Property and Natural Resources. World Development 25 (8): 1303–1315.

- Mohanty, R. 2004. Institutional Dynamics and Participatory paces: The Making and Unmaking of Participation in Local Forest Management in India. IDS Bulletin 35 (2): 26–32.

- Molina, S., J. Pérez, and M. Herrera. 2014. Assessment of Environmental Payments on Indigenous Territories: The Case of Cabecar‐Talamanca, Costa Rica. Ecosystem Services 8: 35–43.

- Morales, M. C., and L. M. Harris. 2014. Using Subjectivity and Emotion to Reconsider Participatory Natural Resource Management. World Development 64: 703–712.

- Muñoz‐piña, C., A. Guevara, J. M. Torres, and J. Braña. 2008. Paying for the Hydrological Services of Mexico's Forests: Analysis. Negotiations and Results. Ecological Economics 65 (4): 725–736.

- Mukasa, C., A. Tibazalika, A. Mango, and H. Muloki. 2012. Gender and Forestry in Uganda: Policy, Legal and Institutional Frameworks. Working Paper 89. Bogor, Indonesia: CIFOR.

- Nightingale, A. 2013. Fishing for Nature: The Politics of Subjectivity and Emotion in Scottish Inshore Fisheries Management. Environment and Planning A 45: 2362–2378.

- Nightingale, A. 2011. Bounding difference. Intersectionality and the material production of gender, caste, class and environment in Nepal. Geoforum 42 (2): 153–162.

- Osborne, T. M. 2011. Carbon forestry and agrarian change: access and land control in a Mexican rainforest. Journal of Peasant Studies 38 (4): 859–883.

- Pascual, U., J. Phelps, E. Garmendia, K. Brown, E. Corbera, A. Martin, E. Gomez‐baggethun, and R. Muradian. 2014. Social Equity Matters in Payments for Ecosystem Services. BioScience 64 (11): 1027–1036.

- Procuraduría Agraria. 2009. Presencia de la mujer en el ejido. Revista de Estudios Agrarios 41: 199–204.

- Procuraduría Agraria. 2014. Ley Agraria y glosario de términos jurídicos‐agrarios 2014. México DF: Secretaría de Desarrollo Agrario, Territorial, y Urbano.

- Radel, C. 2012. Gendered Livelihoods and the Politics of Socioenvironmental Identity: Women's Participation in Conservation Projects in Calakmul, Mexico. Gender, Place and Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography 19 (1): 61–82.

- Radel, C. 2005. Women's Community‐Based Organizations, Conservation Projects, and Effective Land Control in Southern Mexico. Journal of Latin American Geography 4 (2): 7–34.

- Rankin, K. N. 2001. Governing Development: Neoliberalism, Microcredit, and Rational Economic Woman. Economy and society 30 (1): 18–37.

- Rose, G. 1993. Feminism and Geography: The Limits of Geographical Knowledge. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- SEMARNAT [Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales]. 2008. Hacia la igualidad de género y sustentabilidad ambiental 2007–2012. México, DF: Secretaria de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales.

- SEMARNAT [Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales]. 2015. Anuario estadístico de la producción forestal 2015. México, DF: Secretaria de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales.

- SEMARNAT INECC [Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales y Instituto Nacional de Ecología y Cambio Climático]. 2012. Quinta Comunicación Nacional ante la Convención Marco de las Naciones Unidas sobre el Cambio Climático. México, DF: Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Semarnat) e Instituto Nacional de Ecología y Cambio Climático (INECC).

- Shillington, L. 2008. Being(s) in Relation at Home: Socio‐Natures of “Gardens” in Managua. Nicaragua. Social and Cultural Geography 9 (7): 755–776.

- Sijapati basnett, B. 2008. Gender, Institutions and Development in Natural Resource Management: A Study of Community Forestry in Nepal. PhD diss., London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Shapiro‐garza, E. 2013. Contesting the Market‐Based Nature of Mexico's National Payments for Ecosystem Services Programs: Four Sites of Articulation and Hybridization. Geoforum 46: 5–15.

- Sommerville, M., J. P. G. Jones, M. Rahajaharison, and E. J. Milner‐gulland. 2010. The Role of Fairness and Benefit Distribution in Community‐Based Payment for Environmental Services Interventions: A Case Study from Menabe. Madagascar. Ecological Economics 69 (6): 1262–1271.

- Stephen, L. 2005. Women's Weaving Cooperatives in Oaxaca an Indigenous Response to Neoliberalism. Critique of anthropology 25 (3): 253–278.

- Stephen, L. 1996. Too Little, Too Late? The Impact of Article 27 on Women in Oaxaca. In Reforming Mexico's agrarian reform, edited by L. Randall, 289–303. Chicago: ME Sharpe.

- Sultana, F. 2009. Community and Participation in Water Resources Management: Gendering and Naturing Development Debates from Bangladesh. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 34 (3): 346–363.

- Sunam, R. K., and J. Mccarthy. 2010. Advancing Equity in Community Forestry: Recognition of the Poor Matters. International Forestry Review 12 (4): 370–382.

- Sundberg, J. 2004. Identities in the Making: Conservation, Gender and Race in the Maya Biosphere Reserve, Guatemala. Gender, Place and Culture 11 (1): 43–66.

- Swyngedouw, E. 1999. Modernity and Hybridity: Nature, Regeneracionismo, and the Production of the Spanish Waterscape, 1890–1930. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 89 (3): 443–465.

- Taylor, P. L., and C. Zabin. 2000. Neoliberal Reform and Sustainable Forest Management in Quintana Roo, Mexico: Rethinking the Institutional Framework of the Forestry Pilot Plan. Agriculture and Human Values 17 (2): 141–156.

- Vázquez garcia, V. 2015. Manejo forestal comunitario: Gobernanza y género en Hidalgo. México. Revista Mexicana de Sociologia 77 (4): 611–635.

- Vázquez garcia, V. 2002. ¿Quién cosecha lo sembrado? Relaciones de género en un área natural protegida Mexicana. México: Plaza y Valdés, Colegio de Postgraduados en Ciencias Agrícolas.

- Westholm, L., and S. Arora‐jonsson. 2015. Defining Solutions, Finding Problems: Deforestation, Gender, and REDD+ in Burkina Faso. Conservation and Society 13 (2): 189–199.