Abstract

New‐build development has become associated with the phase of gentrification that has taken shape since the mid‐1990s. This article examines the gentrification of Deep Deuce, a historically black neighborhood in Oklahoma City. An analysis of property sales identifies the major external agents involved and leads to a discussion of the area's racial turnover. Considering the relational aspects of place, specifically how the identity of Deep Deuce has been constructed in relation to the nearby area of Bricktown, provides new insights on the nature of changes affecting this neighborhood. Supplementing this with an examination of resistance to the gentrification of Deep Deuce shows how city neighborhoods can come to be defined by limited understandings of place, and how historic preservation efforts can generate symbolic capital and facilitate cultural appropriation. This article also contributes to the study of gentrification in smaller metropolitan areas.

I don't want to return to Oklahoma City ten years from now and see townhouses, garden apartments and high‐rise office buildings [in Deep Deuce]

Situated about a half of a mile east of Oklahoma City's central business district, Deep Second Street or Deep Deuce, developed as the commercial heart of a once‐thriving African‐American neighborhood.Footnote1 Deep Deuce came into being as a result of segregation and determined efforts to restrict the presence and mobility of blacks in the city. During the late 1970s, plans to construct a federal interstate threatened the existence of the Deep Deuce neighborhood and prompted a civil rights lawsuit filed by a local neighborhood association. At that time, Ellen Feingold, quoted in the epigraph, served as the leading civil rights official within the U.S. Department of Transportation.Footnote2 In that capacity, she determined that the proposed highway would infringe on the civil rights of neighborhood residents by disproportionately affecting minority homes and businesses. She expressed the sentiments above during a visit with city and state officials in Oklahoma City about the expected impacts of the highway on a minority community.

For approximately one year, Feingold rejected the city's plan to mitigate adverse impacts on the black community. One sticking point involved the housing for residents who would be relocated. Feingold wanted the city to build houses for displaced residents in the same vicinity instead of moving them into existing homes in other parts of the city (Malone Citation1980). Following a long series of discussions with city and state officials, including negotiations with then‐Senator David Boren, as well as acrimonious exchanges with the state's Transportation Department that were relayed through the local media, Feingold eventually approved the city's mitigation plan, giving the green light for construction of the interstate to proceed.

Feingold was well aware of the problems associated with urban renewal, and her comments called attention to the changes likely to be unleashed in the multifaceted process of redevelopment often triggered by interstate construction in urban settings. Had Feingold returned to Deep Deuce in 1990, ten years after her comments, she would not have seen a gentrified landscape. The interstate, I‐235, was not completed until 1989.Footnote3 The changes she foresaw were not realized for another twenty years, at which time she would have detected an emerging low‐rise “amenityscape” for middle‐ and upper‐middle‐class residents. She would have been challenged to find a minority community living in the area. Like anyone familiar with the history of Deep Deuce, she might have asked whether Deep Deuce had, in fact, survived.

The transformation of Deep Deuce goes far beyond that which is visible on the landscape. It likewise provides an instructive example to geographers and others of the potential pitfalls associated with trying to discern, only by reading the extant landscape, the nature of the forces that produced it. Since the initial federal approval in 1976 to construct I‐235, the remaking of Deep Deuce has been underway for more than forty years—a remarkably long time. This process has involved a complicated series of events linking local, state, and federal scales. It has also been shaped by approaches to urban planning and urban management that reflect the enduring influence of urban renewal and gentrification on the functioning and form of urban places. For this reason, it is not adequate to explain the transformation of Deep Deuce as simply an example of the consequences of urban renewal. Nor is it adequate to attempt to explain Deep Deuce as solely an example of gentrification. These two processes have been intricately woven together, which necessitates a consideration of both.

With these points in mind, this paper examines the urban dynamics that have worked to transform Deep Deuce. This remaking of Deep Deuce has been heavily contested from the very beginning. It has also involved complex aspects not only of urban renewal and gentrification, but also commodification and cultural appropriation. While most studies of gentrification have deservedly focused on larger and global cities, we know much less about how the forces of renewal and gentrification have played out in smaller metropolitan areas such as Oklahoma City. This study offers new insights on a little‐studied city by documenting the impacts of urban renewal long after the federal program ended. This study also highlights the ways in which local decisions have worked to limit the visibility of Deep Deuce and its history, as well as local efforts to push back against this.

In the sections that follow we endeavor to reconstruct and depict Deep Deuce before and during the redevelopment process, which is very much still underway. We begin with a discussion of the broader context of events and scholarly approaches to urban renewal and gentrification before moving on to our methods. We then turn to a consideration of the key actors and events involved in the remaking of Deep Deuce. Lastly, we track changes to the cultural landscape within Deep Deuce, paying attention to the efforts of Deep Deuce advocates to preserve the uniqueness of the place. We also emphasize the complicated ways in which historic preservation can challenge or support gentrification, and even facilitate cultural appropriation. By combining a focus on a smaller metropolitan area with an emphasis on “new‐build development,” our study aims to add another dimension to our understanding of the “geography of gentrification” (Lees Citation2000, 389; 405).

Urban Renewal, Redevelopment and Gentrification

In the context of American cities and housing policy, urban renewal is commonly associated with federal legislation that enabled slum clearance and demolition projects. Strictly speaking, however, the term “urban redevelopment” initially linked the processes of slum removal and blight clearance, in part because of language in the Housing Act of 1949. However, it was language in the Housing Act of 1954 that introduced the term “urban renewal,” and generally favored it over the earlier use of “urban redevelopment.” Moreover, as early as the 1940s, cities across the country had created urban renewal authorities or agencies to provide a means of handling federal funds and to identify urban redevelopment projects. These urban renewal agencies were simultaneously empowered with certain legal rights to carry out their charge. Oklahoma City formed its urban renewal authority in 1961. Although the federal government officially ended the urban renewal program in 1974, most cities have retained their urban renewal agencies. These entities now tend to focus their efforts on “urban revitalization.”Footnote4

Simply stated, urban renewal is about land use, particularly ways of improving the value—economically and aesthetically—of land. As much as urban renewal constituted a program or set of initiatives, it also operated, and continues to operate, as a process of urban and spatial restructuring. Much the same can be said about gentrification. Writing in the aftermath of the recession of the early 1990s, Neil Smith made the case that gentrification was not limited to residential makeovers. As he explained,

…what we think of as gentrification has itself undergone a vital transition. If in the early 1960s it made sense to think of gentrification very much in the quaint and specialized language of residential rehabilitation that Ruth Glass employed, this is no longer so today.

Gentrification has become an enduring global habit, but one that has evolved over time. Drawing on their research on gentrification in New York City, Jason Hackworth and Smith identify three different “waves” of gentrification (2001, 456). These waves are linked to prevailing economic conditions and are distinguished by changes in the nature of state involvement. Considerable federal assistance guided first‐wave gentrification of the late 1960s and early 1970s. During the second wave, which extended through the 1980s, gentrification diffused to many more cities, but the state played a more secondary role. The second wave also coincided with the emergence of burgeoning arts scenes in gentrified areas, as well as highly visible protests and efforts to forestall the impacts of gentrification on lower‐income groups. In contrast, third‐wave gentrification, also called “postrecession gentrification,” emerged by the mid‐1990s (Hackworth Citation2002). Third‐wave gentrification is characterized by a return to higher levels of state involvement, including such practices as municipal decisions about zoning or making mortgage insurance available to developers. These sorts of state involvement tend to reflect the fact that an important shift in scale has occurred such that third‐wave gentrification tends to be driven by large commercial developers, as opposed to individuals or smaller enterprises (Hackworth and Smith Citation2001).

Third‐wave gentrification has also become associated with new‐build gentrification, but some dissensus about this exists.Footnote5 The disagreement centers on whether the construction of new residential or mixed‐use developments in or near the central city constitutes gentrification (Davidson and Lees Citation2005; Boddy Citation2007; Davidson and Lees Citation2010). Technically, because new‐build development often involves vacant land or even brownfield sites, displacement cannot occur. Thus, for those who view displacement as crucial to the definition and operation of gentrification, “new‐build gentrification” is a misnomer. For example, although Boddy agrees that “[p]rocesses of urban change mutate over time and conceptual approaches and definitions must recognise and account for such change,” he finds with new‐build gentrification that “the concept [gentrification], and what it conveys, may have been stretched beyond the point at which it remains useful and credible as a means of understanding the processes at work” (2007, 98).

In contrast, the practice of taking a broader view of the meaning of gentrification has long existed (Davidson and Lees Citation2005, Citation2010). Our work follows in this line of thought. When Ruth Glass defined gentrification, she anchored it to the class‐based changes underway in urban neighborhoods as a result of the arrival of a new “gentry” (Citation1964). Gentrification scholars now recognize that both direct and indirect forms of displacement can occur (Davidson and Lees Citation2005). Thus, new‐build development constitutes gentrification when it creates upscale developments that are designed and priced to attract a new middle class, while indirectly excluding lower‐income groups in the process (Davidson and Lees Citation2005). In addition, because certain city districts and neighborhoods are more attractive to reinvestment than others and do not share the same propensity to be gentrified, “‘gentrification’ theory,” as Blair Badcock reminds us, “is obliged not only to account for the timing of revitalization, but why certain cities and certain blocks within their inner areas are attracting residential re‐investment” (Citation1993, 192). With respect to Deep Deuce, research is needed to consider the general contours of the area's redevelopment in light of its lengthy time span. Doing so allows us to see that new‐build development is a recent manifestation of the forces propelling the gentrification of Deep Deuce.

Study Area and Methods

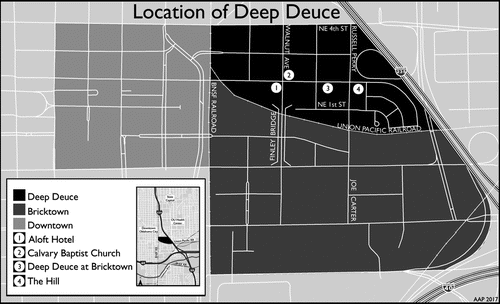

Deep Deuce is part of Oklahoma City's urban core and is located about a mile‐and‐a‐half south of the state capitol and less than a half‐mile north of Bricktown, the city's most recognized entertainment district.Footnote6 The Union Pacific and BNSF railroads form, respectively, the southern and western boundaries of Deep Deuce. Interstate 235 bounds Deep Deuce on the eastern side, and Northeast Fourth Street marks its northern perimeter. At its widest extent, Deep Deuce stretches approximately five blocks from east to west, and four blocks from north to south (Figure 1).

We conducted archival and field‐based research for this study. We used primary documents such as city directories to help understand the evolution of Deep Deuce. We were attentive to the neighborhood's residents—including where they lived, their race, and occupation—as well as the area's businesses and buildings. We supplemented this information with research utilizing government documents, newspapers, written correspondence, and city council minutes. To more fully understand how Deep Deuce changed over time, as well as how the area was redeveloped beginning in the 1990s, we used socio‐demographic data from the census for the region from 1960 to 2010. Because we were interested in block‐level data, some typical indicators, such as income, education, and age were not available due to low population in the reporting blocks. Thus, changes in the racial composition of the blocks became an important indicator of gentrification.

In order to understand the interconnected processes of urban renewal and gentrification, we examined all of the more than 470 parcels of land in Deep Deuce, and tracked changes in their ownership. We were specifically interested in when an individual resident sold his or her parcel to a private company, real estate developer, or to a governmental entity. By using the Oklahoma County Registrar of Deeds search engine provided by the County Clerk's office, it was possible to track the sale of lots in Deep Deuce from private, noncommercial owners to a business, real estate developer, or governmental body.

Over the course of several years, we also made numerous trips to Deep Deuce. We took detailed notes on the visible changes in the area. We visited each business establishment in Deep Deuce to help document the arrival of new kinds of residential, commercial, and retail development, as well as to observe the clientele and examine the ways in which these establishments expressed or appealed to the area's history. In order to glean information about the present‐day depiction of Deep Deuce's past in the cultural landscape, we paid particular attention to repurposed buildings, street signage, and historical markers in the area.

Racial Zoning, Resilience, and Resistance

The history of Deep Deuce is intimately bound up with its development and emergence as a racially stigmatized part of Oklahoma City. By the 1890s, Oklahoma City already had a small but growing black presence between Northeast First and Fourth Streets. In describing the general locational characteristics of urban black districts, David Lee notes that apart from railroad or other notable environmental boundary markers these districts “…directly abutted white ones” (Citation1992, 376). Deep Deuce mirrors that pattern, with the railroads serving as the closest thing to fencelike barriers on the neighborhood's southern and western sides.

The push for statehood, which was realized in 1907, exacerbated conditions for blacks in Oklahoma in part because of its largely southern political orientation. William “Alfalfa Bill” Murray, who presided at the convention for statehood and would later serve as the state's governor, emerged as one of Oklahoma's most infamous demagogues. An especially telling series of events occurred in 1933 when, as governor, Murray used his authority to establish a “segregation line” to prevent the northern expansion of Deep Deuce. He then urged city officials to create a racial zoning ordinance to enforce it, which they did. Black resistance to these various efforts was swift and strong, and they tested these ordinances in court. The State Supreme Court ultimately ruled against these city actions in a 1935 decision that found the zoning ordinance unconstitutional.

Despite city and state efforts to constrain and control Deep Deuce, local residents continued to harness their human capital and deployed their resources in ways that promoted community building, resistance, and individual talents. For example, Deep Deuce was home to The Black Dispatch, a newspaper for the African‐American community. The newspaper's editor and publisher, Roscoe Dunjee, was an advocate for civil rights and an important leader in the local community. Deep Deuce, and Northeast Second Street more specifically, became a destination on the jazz scene. Jimmy Rushing, the famous vocalist in Count Basie's Orchestra, performed in Deep Deuce and was a member of the Oklahoma City Blue Devils, an area jazz band. The renowned guitarist, Charlie Christian, also became part of the local jazz scene. Arguably, the most influential woman associated with Deep Deuce was Zelia Breaux, who lived four blocks north of Deep Deuce. Breaux was a co‐owner and driving force behind the creation and operation of the Aldridge Theater on Northeast Second Street. This theater was an important venue for live performances and movies. Breaux also taught music at the African‐American high school and counted Jimmy Rushing and Ralph Ellison as two of her many students.Footnote7

Deep Deuce is also home to Calvary Baptist Church, a rare example of a 1920s‐era church designed and built by an African‐American (Ruth Citation1978). Martin Luther King, Jr., preached here as well, and local anecdotes suggest that he may have also interviewed for a job as pastor. In the late 1950s, the youth sit‐in movement to resist segregated lunch counters in downtown Oklahoma City was launched from a meeting that began at Calvary Baptist Church (Ruth Citation1978). As the city developed its urban renewal plan, which called for the construction of the expressway, black residents of the affected areas not only spoke out against and protested the plan, they also circulated petitions in favor of saving several of the historic buildings in the area and formed several grassroots organizations to resist urban renewal and protect Deep Deuce (Moore Citation2000).

The Changing Face of Deep Deuce

A bustling area with doctors, hotels, fraternal lodges, auto repair shops, gas stations, movie theaters, churches, eateries, and more, Deep Deuce entered a period of decline in the 1960s. During that decade the area's population of approximately 1,700 residents dropped by nearly half (United States Census Bureau Citation1961, Citation1971). Cars and urban sprawl were undoubtedly part of this change. Together they altered not just the urban dynamics of Oklahoma City and Deep Deuce, but also the social dynamics. Mindy Thompson Fullilove describes this as “…an alteration of street activity…” that stemmed from people no longer walking as much as they once did (Citation2004, 83). Streets lost their centrality as gathering places for meeting and greeting one another. In a poignant sign of the times, the Aldridge Theater had closed by the early 1960s.

Like districts and neighborhoods in other cities, Deep Deuce experienced many of the same general developments. Neglect of the area's infrastructure, its ageing housing stock, the shuttering of businesses, and the simultaneous remaking of different parts of Oklahoma City's core in conjunction with other renewal projects all helped to shine a light on Deep Deuce as a blighted area that was ripe for renewal itself. What is surprising about Deep Deuce, however, is that it stands as a textbook example of an urban neighborhood that experienced an almost complete depopulation and demographic turnover. The total population of Deep Deuce declined precipitously from the 1960s. By 2000 the small remaining population was almost entirely African‐American, and a decade later an influx of whites turned this around (see Table ).

Table 1. Population Change in Deep Deuce by Decade

Another way in which the transformation of Deep Deuce differs from other inner‐city neighborhoods involves the long period of external involvement. Various external interests—both individual and corporate—quickly began buying property in the area, and yet the redevelopment process was very slow to get underway. For example, the Kerr‐McGee Corporation began purchasing property in Deep Deuce as early as 1969.Footnote8 In that year alone, the corporation purchased all or part of nineteen different lots in the study area. By the close of the 1970s, Kerr‐McGee had purchased fifty‐two or 11 percent of the land parcels within Deep Deuce. The corporation resold most of its properties to developers in 2002.

As specific plans for the route of the interstate got underway, the Oklahoma Department of Transportation (ODOT) also began buying lots in Deep Deuce. ODOT purchased almost all of all the parcels sold in Deep Deuce in the 1980s, most of which were located in the northeast section of the neighborhood nearest the planned route for the interstate. When the route for the interstate was finalized, Deep Deuce was spared but isolated. Sizable portions of the adjacent Harrison‐Walnut neighborhood were to be sacrificed to accommodate the interstate, but Deep Deuce was cut off from the rest of northeast Oklahoma City. By the end of the 1980s, business interests and state government had purchased almost half of the lots in Deep Deuce.

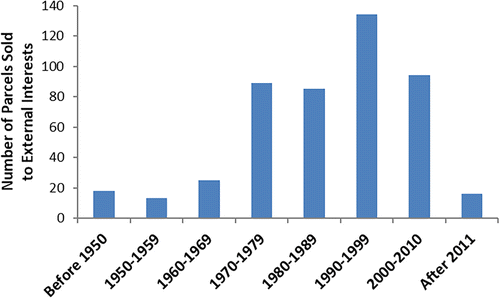

Two other major actors were involved in the acquisition of property in Deep Deuce. One was the Oklahoma City Urban Renewal Authority (OCURA). Some individuals sold their property directly to OCURA, but in many instances OCURA exercised its right of eminent domain to acquire properties. By 2000, OCURA had taken possession of approximately one‐quarter of the properties in Deep Deuce, most of which were acquired in 1997 or later. The other major actor was an individual, Craig Brown, who bought properties in his name and on behalf of his company, Brown Development Group. Brown acquired nearly as many properties as Kerr‐McGee, with 75 percent of those transactions taking place between 1992 and 1998. Altogether, more lots were sold to external interests in the 1990s than in any other decade (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Number of parcels of land in Deep Deuce sold to external interests, by decade. Source: Registrar of Deeds, Oklahoma County Clerk's Office.

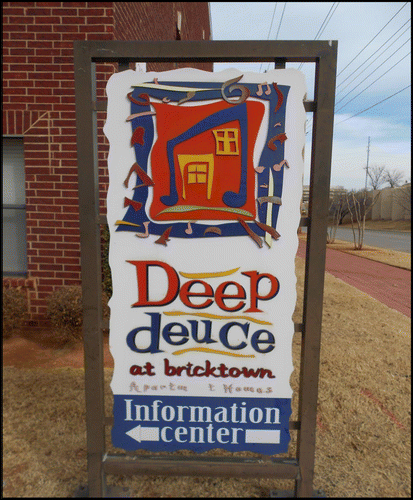

The proximity of Deep Deuce to the downtown, Bricktown, state government offices, and the University of Oklahoma Center for Health Sciences enhanced the area's potential for new residential construction. In the early 2000s the first major postinterstate construction and new‐build project in Deep Deuce was completed. It was an apartment complex with nearly 300 units, none of which was designated “affordable” (Figure 3). The apartment complex has been sold three times since it was completed. The sale price has risen from $22 million ($7 million above the original investment) to just over $38 million after its most recent sale in 2013 (Lackmeyer Citation2007). These sales provided the first major indication that economic investment in Deep Deuce could generate lucrative returns. Between 2008 and 2016, five additional high‐end residential developments including loft apartments, brownstone row houses, and townhomes transformed the look and feel of Deep Deuce (Figure 4).

Figure 3. The first new‐build construction in Deep Deuce consisted of brick veneer low‐rise apartments designed to complement existing structures such as the historic property with the sign and metal awning on the far left. Photo by Alyson L. Greiner, 2017.

About three years ago, the Aloft Hotel, a new seven‐story boutique‐style hotel, opened as well. According to the 2010 Census, most of the people living in Deep Deuce were white (refer again to Table ), and the average per capita income came to just over $55,000, signaling the arrival of a new middle class to Deep Deuce. By 2015, the average selling price for a condominium, loft, or apartment in Deep Deuce had surpassed $500,000 (Realtor Citation2015). The construction of luxury townhomes in the easternmost part of Deep Deuce that sell in the range of $500,000 to upwards of $1,000,000 has pushed the price point well beyond the level of affordability. In addition to upscale condos, Deep Deuce is now home to several bar‐and‐grill restaurants, law offices, a locally sourced grocery, a nonprofit art center, and a whiskey lounge. This new‐build development caters to a wealthier clientele and has turned Deep Deuce into a neighborhood that is much less accessible to lower‐income families and individuals.

In the Shadow of Bricktown

The material and class‐based transformations of Deep Deuce have created a neighborhood in search of an identity. From a planning perspective, Deep Deuce has and continues to lie in the shadow of Bricktown, but Deep Deuce is not Bricktown—or at least not yet. A tacit planning principle is that development initiatives undertaken in Deep Deuce should not challenge the primacy of Bricktown, but rather must support it. In fact, the most recent strategic plan for Bricktown identifies “competition from other parts of downtown” as one of the major challenges facing Bricktown (City of Oklahoma City Citation2012, 9). The redevelopment of Deep Deuce is thus connected relationally to the perceived “needs” of Bricktown. This has the effect of reinforcing narrow conceptualizations of place that diminish the importance of Deep Deuce as a part of the city with a significant and distinctive history.

One of the first indicators of this tiered relationship between Bricktown and Deep Deuce came with the naming of the first new‐build apartment complex, mentioned above. When it opened in 2001, it was named “Deep Deuce at Bricktown: Apartments and Homes” (Figure 5). In addition, some websites refer to Deep Deuce as “Bricktown North” and some maps of the city simply don't label Deep Deuce.Footnote9 More tellingly, searching the internet for the Aloft Hotel returns, among others, the following result: “Aloft Hotels – Oklahoma City Downtown – Bricktown.” Clearly, the name “Deep Deuce” does not have the same familiarity that “Bricktown” does. More importantly, “Deep Deuce” also does not have the same symbolic capital. When the hotel was preparing to open, its developer made the following comments, “I looked at this location and I felt that we have the entrance into Bricktown and we needed to add a lot more than a standard Aloft has” (quoted in Lackmeyer Citation2014). The need to have a foot on the doorstep to Bricktown and the sense of feeling pressured to add additional amenities based on consumption patterns in Bricktown illustrate that even the identity of this hotel is bound up more closely with Bricktown than Deep Deuce. This pattern of businesses and residential areas retaining an association with Bricktown continues. The newest luxury residences are called “The Hill at Bricktown Townhomes” even though they are located in Deep Deuce.

Figure 5. Sign advertising the Deep Deuce at Bricktown Apartments and Homes. Photo by Adam A. Payne, 2014.

Some geographers have shown that administrative and policy decisions about neighborhood development are informed more by conceptions of relative space, such as spaces of investment and disinvestment, and thus are not “…tethered to specific neighborhoods” (Larsen Citation2004, 32). Such perspectives do influence city development and management perspectives, but our findings suggest that relational aspects of place are also important. In the case of Deep Deuce, such relations also reveal very narrow conceptualizations of place (Rushing Citation2000). These sorts of narrow conceptualizations of place might be seen as advantageous in terms of slowing the gentrification of Deep Deuce, but more significant is the fact that they have enabled a reductive understanding of place.

In 2010 the Aloft Hotel announced that it was going to build in Deep Deuce. More than a decade prior to that announcement, however, some conflict arose about whether to preserve the nearby historic Walnut Avenue Bridge. The bridge dates to the 1930s and connects Deep Deuce to Bricktown. Specifically, it provides both pedestrian and vehicular travel above old railroad tracks once part of the Rock Island Railroad network. Its engineering provides a rare example of the use of special metal covers that protect the bridge from the steam of the old locomotives (Lydick Citation2001). Beyond that, it was also a lifeline for many Deep Deuce residents who once worked in the warehouses near the railroad and relied on the bridge to get to and from work. The bridge also carried students and teachers to and from the old African‐American high school, and graduating seniors crossed the bridge to reach Calvary Baptist Church because it had enough space for the graduation ceremonies (Lydick Citation2001). Although the bridge was not only used by Deep Deuce residents, it clearly was an important part of the social fabric of the neighborhood.

When the city council voted down a recommendation to recognize the bridge as a historic landmark, their action triggered the formation of an alliance between the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and a group of historic preservationists. Designating the bridge a historic landmark would have made it difficult for the city to tear down the bridge (Money and Lackmeyer Citation1999). Nevertheless, the historic preservationists were keen to prevent the loss of another historic structure. For the NAACP chapter president, however, the controversy was less about saving the bridge and more about allowing the African‐American community to have a greater say in the plans for the redevelopment of Deep Deuce (Lackmeyer and Money Citation1999).

A fundamental argument against saving the bridge was that the cost of some necessary repairs would exceed the cost of tearing it down. In addition, removing the bridge would enable the city to create another parking lot for Bricktown. These views were succinctly stated in an editorial that ran in the Daily Oklahoman and argued that, “[t]o remove the bridge is to open up parking expanses on the north edge of Bricktown, as well as improve access to the area….The bridge is a hindrance to Bricktown's growth” (Daily Oklahoman Citation2001). As this example shows, narrow conceptualizations of place privileged Bricktown and marginalized Deep Deuce.

In the end, it was not up to the city council to decide the fate of the bridge. The issue fell to the Oklahoma Corporation Commission, which regulates transportation and public utilities. That Commission ruled, in 2001, that a street‐level crossing of the railroad tracks would be more hazardous. Retaining the bridge, it turned out, was essential for public safety. The bridge was not only saved, but in 2005 was renamed the Finley Bridge to honor an African‐American doctor, Gravelly Finley, who maintained his practice in Deep Deuce for more than sixty years. The 1950s‐era building that housed his clinic would, however, soon be torn down and replaced by the Aloft Hotel (Figure 6).

Figure 6. A view of Deep Deuce from the Finley Bridge. The Aloft Hotel is on the left and Deep Deuce Apartments are on the right. Photo by Alyson L. Greiner, 2017.

Another example highlights the tendency of municipal decisions to favor the primacy of Bricktown. In 2000, the city's Planning Commission recommended renaming a street that stretches from Bricktown to Deep Deuce in honor of Joe Carter, a highly accomplished major league baseball player whose walk‐off home run won the 1993 World Series for the Toronto Blue Jays. Carter is an African‐American and native of Oklahoma City. He grew up and attended high school on the city's northeast side. The street that would bear his name runs beside the Bricktown Ballpark. However, some Deep Deuce advocates spoke out against the recommendation because, while they meant no disrespect to Carter, he had never lived in and was not associated with Deep Deuce (Money Citation2000). As a result of their outcries, this one street now bears two names: in Bricktown it is Joe Carter Avenue, and in Deep Deuce it is Russell M. Perry Avenue. Perry edited the Black Dispatch, the newspaper established by Roscoe Dunjee in Deep Deuce, and then went on to establish his own newspaper for African‐Americans, the Black Chronicle.

Naming is often a commemorative act intended to provide a reminder of some aspect of the past. Much of the power of place names and street names derives not only from their visibility on the landscape and on maps, but also in the language we use when we talk about places. In this way, what we name and where we place those names matter to public memory (Alderman Citation2000). Likewise, “public commemoration is not simply about determining the appropriateness of remembering the past in a certain way; it is also a struggle over where best to locate or place that memory within the cultural landscape” (Alderman Citation2000, 675). For Deep Deuce advocates, the crux of the issue centered on the “where” of the streets named for Carter and Perry. Together, the struggle to save the bridge and the emphasis on commemorating people historically associated with Deep Deuce demonstrate a concern for preserving the uniqueness of Deep Deuce so that it can be and is distinguished from other places.

These examples point to an enduring tendency on the part of city officials to make decisions in a way that reflects Bricktown's priority of place in relation to Deep Deuce. To their credit, members of the City Council, Planning Commission, and OCURA have been willing to listen to the concerns of citizens and stakeholders. These municipal officials have taken these various disagreements seriously, but the fact that these issues emerged suggests that Deep Deuce is often an afterthought. In Oklahoma City, the emphasis on Bricktown created a narrow view that tended to neglect, exclude, or diminish the importance of Deep Deuce as a distinctive place with its own community.

Placing Deep Deuce History

As if presaging the new‐build development to come, three Deep Deuce buildings were listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1995. Prior to this, only Calvary Baptist Church and a historic home in the neighborhood had been listed in the National Register. Of these five architectural resources, only one—Calvary Baptist Church—has a commemorative plaque visible on the exterior of the building.Footnote10 That plaque is from the city's Historical Preservation and Landmark Commission, and neither it nor the informational sign below it mentions that the building is also included in the National Register of Historic Places. To be clear, there is no requirement that any National Register‐listed property have a plaque or other visible signage. The decision to place a plaque or marker is left entirely to the property owner. Even so, it is difficult to separate the limited visibility of Deep Deuce's history in the cultural landscape from the forces of cultural appropriation that have begun to commodify this space.

Calvary Baptist Church has been at the center of these sorts of changes. The church was damaged as a result of the bombing of the Murrah Building in 1995. Although the church was subsequently repaired, lingering and costly maintenance issues led the congregation to list the building for sale. A lawyer, Dan Davis, purchased the church in 2012, and carried out extensive repairs (Figure 7). With the guidance of a preservation architect and an architectural firm whose motto is “We build communities,” the interior was adaptively renovated to incorporate his firm's offices around and above the church sanctuary. The sanctuary, including the original pews, was also restored (Lackmeyer Citation2014; MODA Citation2013). Davis's wife, Joy, spoke about the importance of the church as a cultural resource to the community, and noted that carrying out the restoration of the church was a way for them to “give it back to the community” (quoted in Bailey Citation2012). The Davis firm makes the church available for special events related to the church, jazz concerts, or Martin Luther King, Jr., Day (Fleming Citation2015). For these several reasons, the Davises have been celebrated as the “saviors” of the church (Fleming Citation2015).

Figure 7. Calvary Baptist Church in Deep Deuce houses a local law firm. Photo by Adam A. Payne, 2014.

Ever so gradually, journalistic discourses like this help to mainstream gentrification by celebrating the benevolent gentrifier. The church is not the only example of this. The developer, Craig Brown, who purchased dozens of the lots in Deep Deuce in the 1990s and who became a partner in the project that culminated in the first new‐build apartments in the area, has also been heralded as “Deep Deuce's savior” (Lackmeyer and Money Citation2000). Use of the term “savior” in this city, which strongly identifies with the Bible Belt, may have a special resonance, but more important is that this new discourse has supplanted that of the 1980s which celebrated the “urban pioneer.”

Returning to Calvary Baptist Church, recent events suggest that its current savior may not be eternal. In an unexpected development, Oklahoma recently revised its system of workers' compensation to abolish the Workers' Compensation Court. Since the Dan Davis Law Firm handled a substantial number of workers' compensation cases, its business has necessarily shifted to other kinds of cases. At this writing, Calvary Baptist Church is for sale with a list price of five million dollars. The Davises originally purchased the church for $700,000 (Bailey Citation2012).

Without a doubt, the investments that the Davises made in the now ninety‐six‐year‐old church saved the structure from deterioration and ruin. More specifically, they took the initiative and led the effort to preserve the oldest and most iconic building in Deep Deuce. We do not question the sincerity of the Davis's intentions. However, we are obligated to note that even for the few years that the law firm has been housed in the church, it has parlayed its location and setting into additional advertising. In the process it has been able to command considerable cultural and symbolic capital. In much the same way that advertising agencies gain prestige by having an address on Madison Avenue, businesses also gain symbolic capital by having a downtown location. Might being housed in a beautiful, historic church building, which the firm restored for the sake of the community, also enhance that firm's reputation? The noted gentrification scholar Sharon Zukin once wondered “whether historic preservation really confers or affirms more ‘distinction’ than the modern style of most new construction” (Citation1987, 135). In this particular instance, we think the evidence indicates that it does.

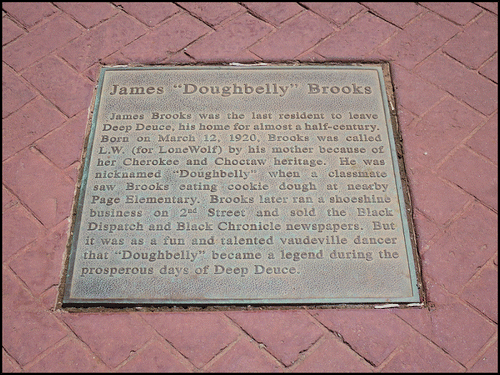

Earlier we discussed the controversy over the Walnut Avenue/Finley Bridge linking Deep Deuce to Bricktown. That controversy and the unlikely alliance it generated had important results. It led to additional open meetings with the developer who constructed the first new‐build apartments. Those meetings helped elicit suggestions about how to incorporate more of the history of Deep Deuce in the area's redevelopment. Some suggestions included renaming additional streets in Deep Deuce after other influential individuals and placing historical markers in front of the extant historical buildings (Erwin Citation1999). Ultimately, however, a different suggestion was accepted. That suggestion was to place several bronze commemorative plaques along the sidewalks, primarily along Northeast Second Street, the portion of Deep Deuce that formed the heart of the historic neighborhood. A public survey was conducted to generate the names of the people commemorated.

The plaques not only commemorate influential individuals associated with Deep Deuce, they also represent a small victory for the activists who spoke out in concern about the loss of Deep Deuce's history. One problem with the plaques is that because of their placement in and flush with the sidewalks, they are not very visible and can easily be missed. In a larger sense, however, they are problematic in the way that they contribute to what Don Mitchell calls “consensus history of place” (Citation1992, 203). These histories not only reduce the past to that which we want to remember, but in the process they elide difficult yet formative topics and events such as tense race relations, discrimination, and injustice, among others.

In the case of Deep Deuce, the area's identity as expressed through the plaques is framed by a historical narrative emphasizing its role as a central place for jazz and blues musicians with a vibrant club scene. A secondary theme articulates a strong concern for and commitment to education on the part of several key individuals. Still, the development of Deep Deuce, because of segregation and racism, is absent from the place narratives constructed about it. Nothing is said about the literal and figurative devaluation of African‐American lives that was used to justify the routing of interstates through their neighborhoods. Only one plaque comes close to hinting at this, and that is the plaque for James Brooks, who became known for his dancing ability. This plaque describes him as “the last resident to leave Deep Deuce” (Figure 8). Without additional information this language effectively naturalizes his departure. Similarly, almost nothing is said about the struggle for and contributions to civil rights that emerged in Deep Deuce. An unfortunate consequence of this is that it marginalizes the realities of the African‐American experience and diminishes the richness of their history as well as the places associated with it.

Conclusion

Gentrification is a complex, multifaceted process that is today geographically widespread. The ubiquity of gentrification leads some researchers to claim that “a ‘gentrification blueprint’ is being mass‐produced, mass‐marketed, and mass‐consumed around the world” (Davidson and Lees Citation2005, 1167). This statement surely applies in a general way, but it neglects the place‐specific character or impacts of gentrification. In the United States, for example, urban renewal and gentrification often have a complicated and interconnected history. On the one hand, that history is linked to improving the economic and aesthetic value of land in or near the urban core. On other hand, that history is also frequently associated with the displacement of minority groups and neighborhood communities in order to profit from real estate investment and development. For these reasons, being attentive to change over the long term can help us build a more nuanced understanding of gentrification.

Our study has focused on the historic African‐American neighborhood of Deep Deuce in downtown Oklahoma City. Our conceptual framework is informed not only by the literatures on the gentrification and urban renewal of African‐American neighborhoods, but also by scholarship emphasizing how the forces propelling gentrification have changed over time (Smith Citation1996; Hackworth and Smith Citation2001; Jackson Citation2001; Patillo Citation2007; Moore Citation2009; Inwood Citation2010). We have drawn on the three “waves” of gentrification identified by Hackworth and Smith, who argue that broad similarities in the nature of state involvement in gentrification help distinguish its different phases or time periods (2001). We have also discussed third‐wave or postrecession gentrification, which has become more common since the 1990s. One manifestation of third‐wave gentrification is often new‐build development. Reinvesting in central city areas via new‐build construction propels gentrification through the direct and/or indirect displacement of lower income groups.

Our study has shown that although the forces of urban renewal and, more specifically, gentrification, have been underway in Oklahoma City's Deep Deuce neighborhood for more than forty years, the area's gentrification was not fully realized until after the turn of the twenty‐first century. At that time, a series of new‐build developments finalized the area's transition from one that was a predominantly African‐American business and residential district to one that is populated mostly by white urban professionals. Subsequent new‐build development, some of which is presently under construction, has continued this trend and is making the area more income exclusive.

Our study of land parcel sales in Deep Deuce enabled us to identify the different business and governmental entities that came to control most of the area's land. These external interests included the Kerr‐McGee Corporation, OCURA, ODOT, and a private development company. We had not anticipated Kerr‐McGee's involvement and yet, given the nature of Deep Deuce's situation relative to the Oklahoma City oilfield and the corporation's compelling interest in real estate, that Kerr‐McGee would be involved seems obvious in hindsight.

Despite expressed concerns about blight in Deep Deuce that date at least to the 1980s, momentum propelling the visible expression of gentrification on the cultural landscape increased in the 1990s. New‐build development came to Deep Deuce in the early 2000s with the opening of an upscale apartment complex. The low‐rise apartments with their very modest brick veneer cladding not only complemented the few surviving historic buildings in Deep Deuce, but also visually repeated the look and feel of many of the buildings in nearby Bricktown. Since the recession of the late 2000s, several more upscale condos and townhomes have been built in Deep Deuce, dramatically transforming the landscape and place.

As these changes to Deep Deuce have occurred other conflicts have shown that Deep Deuce has not been seen as having the same importance or “priority of place” that Bricktown does. This perspective is evident in decisions about the naming of some of the new residential developments, the naming of certain streets, and conflict over the preservation of the historic Walnut Avenue/Finley Bridge. While this perspective may have worked to scale back the nature and pace of Deep Deuce's gentrification, it has necessitated an ongoing struggle on the part of Deep Deuce advocates to preserve the area's history, maintain its uniqueness as a place, and counter narrow conceptualizations of place that envision Deep Deuce as little more than an extension of Bricktown.

The placement of plaques commemorating great African‐Americans who grew up or spent time in Deep Deuce represents an important success in the sharing of Deep Deuce's history with the public, although they are necessarily partial and tend to focus mainly on the importance of the historical jazz scene. From the standpoint of historic preservation, the example of the restoration of the Calvary Baptist Church is equally complicated. On the one hand it has protected what is truly a priceless cultural resource. On the other hand, the investment in the church's restoration cannot be disentangled from the appropriation of symbolic capital.

There is still more that the city could do to promote awareness of Deep Deuce's past and make it manifest in the cultural landscape. Back in 1999 when the fate of the Walnut Street bridge was being debated, a reporter recorded the following observations made by a historic preservationist and member of the organization Preservation Oklahoma: “[h]e said he's worried that 10 years from now, the history there [in Deep Deuce] will not be marked by anything more tangible than a plaque” (Hinton Citation1999). At this writing that does indeed seem to be the case. Moreover, those comments are uncannily similar to the ones that Feingold made and which were quoted at the start of this article. Deep Deuce needs another concerted effort to build knowledge about it as a historic neighborhood, community, and place valuable not only to African Americans, but all Oklahoma City dwellers.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Adam A. Payne

Adam A. Payne, Ph.D. Lecturer of Geography Department of Geosciences Auburn University 2046 Haley Center Auburn, AL 36849; [[email protected]].

Alyson L. Greiner

Alyson L. Greiner, Ph.D. Professor of Geography Department of Geography Oklahoma State University 337 Murray Hall Stillwater, OK 74078; [[email protected]].

Notes

1. Deep Deuce developed as a mixed commercial and residential neighborhood. On a related note, Richmond, Virginia also has an historic African‐American neighborhood—Jackson Ward—situated along that city's own Second Street. Locals there use the phrase “The Deuce,” but specifically in reference to Second Street (see Bowen Citation2003).

2. Feingold's statement appears in Hinton Citation1980.

3. Ironically, this was the year in which Oklahoma celebrated the centennial of the land run. As a consequence, I‐235 was named “Centennial Expressway.”

4. Unless otherwise stated, in this paper we use the terms “urban renewal,” “urban redevelopment,” and “urban revitalization” synonymously to describe land use, infrastructural, and other urban changes that reflect forces of reinvestment.

5. Yet another expression of third‐wave gentrification is “super‐gentrification,” or the re‐making of once‐gentrified neighborhoods into even more exclusive areas (Butler and Lees Citation2006).

6. Originally a former warehouse district, Bricktown was revitalized and repurposed beginning in the mid‐1990s, and now features a ballpark, restaurants, canal, and other entertainment venues.

7. The distinguished author, Ralph Ellison, was born a block to the south on Northeast First Street in Deep Deuce in 1913.

8. Kerr McGee Corporation, a multinational oil and gas company, had significant real estate interests. The company's interest in the Deep Deuce area stems from the fact that it sits above part of the Oklahoma City oilfield. Oil derricks dotted the area's landscape into the 1950s. In 2007, Anadarko Petroleum Corporation acquired Kerr‐McGee.

9. See, for example, Google Maps, which does not label Deep Deuce but does identify other neighborhoods such as Flat Iron, Automobile Alley, and Midtown.

10. A copy of the National Register of Historic Places certificate hangs on the inside wall near the entrance to the Littlepage Building, which occupies the southwest corner of Northeast 2nd Street and North Central Avenue in Deep Deuce.

References

- Alderman, D. 2000. A Street Fit for a King: Naming Places and Commemoration in the American South. Professional Geographer 52 (4): 672–684.

- Badcock, B. 1993. Notwithstanding the Exaggerated Claims, Residential Revitalisation Really is Changing the Form of Some Western Cities: A Response to Bourne. Urban Studies 30 (1): 191–195.

- Bailey, B. 2012. Attorney Buys Deep Deuce's Calvary Baptist Church Building in Oklahoma City. Journal Record (Oklahoma City), 25 April.

- Boddy, M. 2007. Designer Neighbourhoods: New‐Build Residential Development in Nonmetropolitan UK Cities—The Case of Bristol. Environment and Planning A 39: 86–105.

- Bowen, D. 2003. The Transformation of Richmond's Historic African American Commercial Corridor. Southeastern Geographer 43 (2): 260–278.

- Butler, T., and L. Lees. 2006. Super‐gentrification in Barnsbury, London: Globalization and Gentrifying Global Elites at the Neighborhood Level. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers NS 31: 467–487.

- City of Oklahoma City. 2012. Bricktown Strategic Plan. Oklahoma City: City Planning Department.

- Daily Oklahoman. 2001. A Bridge Too Long. 23 January.

- Davidson, M., and L. Lees. 2005. New‐Build “Gentrification” and London's Riverside Renaissance. Environment and Planning A 37: 1165–1190.

- Davidson, M., and L. Lees 2010. New‐Build Gentrification: Its Histories, Trajectories, and Critical Geographies. Population, Space and Place 16 (5): 395–411.

- Erwin, R. 1999. Letter to R. Milton. 15 July. Max Nichols Collection. Oklahoma History Center, Oklahoma City, OK.

- Fleming, M. M. 2015. Savior of Calvary Baptist Church Looks for Buyer. Journal Record (Oklahoma City), 21 April.

- Fullilove, M. T. 2004. Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America, and What We Can Do About It. New York: Ballantine Books.

- Glass, R. 1964. London: Aspects of Change. London: MacGibbon and Kee.

- Hackworth, J. 2002. Postrecession Gentrification in New York City. Urban Affairs Review 37 (6): 815–843.

- Hackworth, J., and N. Smith. 2001. The Changing State of Gentrification. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 92 (4): 464–477.

- Hinton, M. 1980. Black Community Status Left in Limbo. Daily Oklahoman, 7 April.

- Hinton, M. 1999. Bridge Battle Line Drawn. Daily Oklahoman, 5 July.

- Inwood, J. F. J. 2010. Sweet Auburn: Constructing Atlanta's Auburn Avenue as a Heritage Tourist Destination. Urban Geography 31 (5): 573–594.

- Jackson, J. L. 2001. Harlemworld: Doing Race and Class in Contemporary Black America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Lackmeyer, S. 2007. Deep Deuce Delivers Downtown Deal. Daily Oklahoman, 3 August.

- Lackmeyer, S. 2014. Aloft Hotel in Oklahoma City's Deep Deuce to Open This Week. Daily Oklahoman, 14 April.

- Lackmeyer, S., and J. Money. 1999. NAACP Head Asks for “Deuce” Input. Daily Oklahoman, 7 July.

- Lackmeyer, S., and J. Money 2000. Deep Deuce's Savior Called Visionary. Daily Oklahoman, 27 February.

- Larsen, S. C. 2004. Place, Activism, and Development Politics in the Southwest Georgia United Empowerment Zone. Journal of Cultural Geography 22 (1): 27–49.

- Lee, D. 1992. Black Districts in Southeastern Florida. Geographical Review 82 (4): 375–387.

- Lees, L. 2000. A Reappraisal of Gentrification: Towards a “Geography of Gentrification”. Progress in Human Geography 24 (3): 389–408.

- Lees, L., and D. Ley. 2008. Introduction to Special Issue on Gentrification and Public Policy. Urban Studies 45 (12): 2379–2384.

- Lydick, R. 2001. Groups Lobby to Save Bridge. Daily Oklahoman, 14 January.

- Malone, P. S. 1980. Expressway Plan OK'd. Daily Oklahoman, 14 August.

- Mitchell, D. 1992. Heritage, Landscape, and the Production of Community: Consensus History and Its Alternatives in Johnstown, Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid‐Atlantic Studies 59 (3): 198–226.

- MODA Architecture. 2013. Work: We Build Communities. [http://themodaexperience.com/index.php/work/].

- Money, J. 2000. Deep Deuce Backers Want Different Street for Carter. Daily Oklahoman, 29 September.

- Money, J., and S. Lackmeyer. 1999. Bridge's Backers Strategize. Daily Oklahoman, 9 July.

- Moore, K. 2000. Oklahoma City African‐American Discovery Guide. Oklahoma City: Oklahoma African American Trail of Tears Tours Inc.

- Moore, K. S. 2009. Gentrification in Black Face?: The Return of the Black Middle Class to Urban Neighborhoods. Urban Geography 30 (2): 118–142.

- Patillo, M. 2007. Black on the Block: The Politics of Race and Class in the City. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Realtor. 2015. Home prices and home values: Deep Deuce, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. [http://www.realtor.com/local/Deep-Deuce-Sub_Oklahoma-City_OK/home-prices].

- Rushing, W. 2000. Rural Empowerment Zones and Enterprise Communities: The Impact of Globalization Processes and Public Policy on Economic Development. Journal of Poverty 4 (4): 45–63.

- Ruth, K. 1978. National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Calvary Baptist Church. Oklahoma City: Oklahoma Historical Society.

- Smith, N. 1996. The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City. London: Routledge.

- Spearman, H. 2017. Wheat Street Baptist, Nation's First Church‐Based Senior High Rise Gets Green Light for $25M Renovation Project. Atlanta Daily World, 3 July.

- United States Census Bureau. 1961. 1960 Census of Housing; Volume III: City Blocks. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau.

- United States Census Bureau. 1971. 1970 Census of Housing; Block Statistics Oklahoma City, Oklahoma Urbanized Area. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau.

- United States Census Bureau. 1981. 1980 Census of Population and Housing: Block Statistics, Oklahoma City, Okla., Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau.

- United States Census Bureau. 1991. 1990 Redistricting Data Public Law 94–171 Summary File. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau.

- United States Census Bureau. 2001. 2000 Redistricting Data Public Law 94–171 Summary File. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau.

- United States Census Bureau. 2011. 2010 Redistricting Data Public Law 94–171 Summary File. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau.

- Zukin, S. 1987. Gentrification: Culture and Capital in the Urban Core. Annual Review of Sociology 13: 129–147.