Abstract

Spiritual landscapes arise from a dynamic relationship of spiritual beliefs, ritual practices, and embodied encounters in place. They can contain multiple spiritual and non‐spiritual elements that change over time. This paper offers an appreciation of the diverse, overlapping, and ambivalent meanings emerging from Trappist monasteries in the United States. With origins tracing back to eleventh‐century France, Trappist monasteries are Roman Catholic intentional communities belonging to the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance. Attempts to establish monasteries in the American scene began around the turn of the nineteenth century. Contemplation, a receptive state of interior spiritual silence, represents one significant component of Trappist spirituality. Like other aspects of the spiritual landscape, contemplation has been reprioritized as Trappist monks and nuns confront situations like political conflict, changes in monastic leadership, and economic problems. These places continue to address challenges and possibilities for reinvention as they become open to shifting social contexts.

I've found the Great Silence, and I've come to see that the noise was inside.

In Tales of a Magic Monastery, Theophane Boyd (1930–2003)—a Trappist monk of St. Benedict's Monastery in Snowmass, Colorado—depicted a fictional dialogue between two monks about how to find “the Great Silence” (1981, 55). One monk said that he had tasted the silence at different times, until finally “Jesus came…and said to me simply, ‘Come, follow me.’ I went out, and I've never gone back.” The Great Silence, this monk said, came from inside himself, not externally—a receptive act of unknowing everything he expected about spiritual encounter. This experience is often referred to as contemplation. Trappist monks and nuns have described themselves as contemplative in the purest sense of the word (Merton Citation1949). Ideally, monasteries are deemed quintessential places for fostering physical solitude and community stability necessary for such interior silence (Jones Citation2001; Jonveaux Citation2011; Sbardella Citation2014). Contemplation, as a significant component of the Trappist spiritual landscape, has had an ambivalent past.

This paper traces the evolving spiritual geographies of American Trappist monasteries, from their historical roots in Old World monasticism to joining other contemporary monastic communities as centers of contemplative spirituality (de Groot and others Citation2014). It attempts to understand how shifting historical contexts and relationships between openness (social availability) and cloister (separateness) have influenced the spiritual landscape. Though both spiritual and nonspiritual elements are considered, emphasis is placed on how historical accounts interpret the varying prioritizations of contemplation as a form of monastic place‐making. Two questions structure this discussion. First, how have the characteristics of spiritual landscapes changed during the history of American Trappist monasteries? Second, how have traditional and contemporary expressions of contemplation existed in relation to the spiritual landscape? Trappists (monks) and Trappistines (nuns)Footnote1 belong to Roman Catholicism's Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance (OCSO). The OCSO represents one of the two branches of Cistercians, the second being the Cistercians of the Common Observance (O. Cist.) (Pennington Citation1995; Bell Citation2000). In the United States, they are one of numerous intentional communities in rural areas (Meijering and others Citation2007).

Research included trips to five Trappist monasteries in the United States (out of seventeen in operation) over the course of six years, examination of monastic archives and newspaper articles, and a literature review on monasticism and spiritual landscapes. Four of these monasteries are communities of monks: Abbey of Gethsemani (established 1848, forty‐five monks) in Kentucky, New Melleray Abbey (established 1849, thirty‐four monks) in Iowa, Assumption Abbey (established 1950, ten monks) in Missouri, and St. Benedict's Monastery (established 1956, sixteen monks) in Colorado. One Trappistine monastery, Our Lady of the Mississippi Abbey (established 1964, eighteen nuns) in Iowa, was also visited. Stays lasted between one day to two weeks.

Three takeaways serve as an outline for the proceeding sections. First, the spiritual landscape consists of a variety of representations, which have resulted in ambiguous, overlapping, and diverging meanings. Contemplation may act as an entryway toward appreciating these ambiguities. Second, in the history of American Trappist monasteries—from their origins in France to their New World presence—there exists an ambivalence between “the Great Silence” of contemplation and other conditions that influence how these spiritual landscapes are created, maintained, or disrupted. Such spiritual and nonspiritual forces include the missionary zeal of members, focus on political and economic ambitions, exclusionary practices, politically forced migration, and emphasis of other forms of spiritual exercises, such as asceticism. Contemplation, despite its evident centrality to monastic spirituality, has been historically affected by varying prioritizations. Third, drawing from Danièle Hervieu‐Léger (Citation2014) and Edward Relph (Citation2017), contemporary American Trappist monasteries represent a small, but significant series of case studies for understanding the complicated relationship between openness and cloister in the spiritual landscape. Openness and cloister are paradoxical, yet necessary aspects of monastic confrontations with modernity. Together, openness and cloister present opportunities and challenges associated with maintaining the balance between contemplative solitude and social availability to broader contexts extending beyond monastery perimeters. Concluding thoughts take care to assess the limitations and future possibilities of this exploration.

Contemplation and the Spiritual landscape

Broadly speaking, spiritual landscapes are “co‐constituting sets of relations between bodily existence, felt practice and faith in things that are immanent, but not yet manifest” (Dewsbury and Cloke Citation2009, 696). In other words, spiritual landscapes arise from the synergy of ritual, belief, and existential being‐in‐the‐world. The spiritual landscape was selected because it allows for a gathering of religious and nonreligious situations in place, such as the practice of meditation, brewing beer, or the celebration of Mass (Dewsbury and Cloke Citation2009).

Ambivalence arises in spiritual landscapes because religious traditions are “internally plural, fluid, and evolving” (Appleby Citation2000, 281). Religious practices and meanings are able to change drastically by charismatic figures, and the formation of social movements and communities that react to a certain issue (Appleby Citation2000). In a study of the Earthworks of Newark, Ohio, Lindsay Jones described three attributes of ambiguity that can aid in the investigation of spiritual landscapes (2017). First, spiritual landscapes may contain a multitude of different meanings based on the interpreter, conceptions that are prone to diverge from the landscape's original intent. Second, these places are often sites of varying degrees of disagreement and contestation. Spiritual landscapes, in general, may be tainted by a false spiritualization that can render the landscape superficial or uninspiring (Dewsbury and Cloke Citation2009). The critical, contested realities of spiritual landscapes should be paired with equally realistic, and more empathetic, opportunities for regeneration and reinvention (see Lekai Citation1977). Third, Jones noted a sense of unpredictability that underlies how the meanings attributed to spiritual landscapes may change over time and gain new contexts. Drawing from Jones, the spiritual landscapes of American Trappist monasteries are discussed in terms of their assorted and evolving meanings (2017). While American Trappist spiritual landscapes have been subjected to conflicts between ideals and realities (Lekai Citation1977), they also illuminate the complex connections among these conflicts and ambiguities.

Trappist monasteries represent spiritual landscapes that orient their sense of dwelling and community according to contemplative ideals (Connor Citation1972; Fracchia Citation1979). Contemplation, therefore, exists as one representation of the greater spiritual landscape. Though contemplation embodies a main focus of this paper, it is crucial to note that separating contemplation from the totality of the spiritual landscape would risk misrepresenting other linked spiritual and nonspiritual influences (see Hervieu‐Léger Citation2014). Contemplation is an elusive term, much like the “spiritual landscape” or words such as nature, place, and sacred (see Buttimer Citation2017). Contemplative spirituality has been commissioned in diverse ways inside and outside spiritual circles to uncover commonalities in a culturally diverse world. In planning and design, a contemplative landscape characterizes various architectural encounters, such as a long‐distance view, a sense of peace and solitude, an invitation for rest and relaxation, or a form of enclosure (Olszewska and others Citation2018). In monastic communities, the contemplative impulse has formed an opening from which different faiths find common ground. Beginning in the twentieth century, interfaith dialogue among and about monasteries has considered how contemplation is expressed and experienced in a variety of ways. Such monastic communities include, but are not limited to Buddhist, Hindu, Roman Catholic, and other Christian denominations, like the Anglican and the Eastern Orthodox Church (see Ward Citation1972; Fracchia Citation1979; Ludueña Citation2008; Palmisano Citation2014). Contemplation has acted as a spiritual bridge among monasteries, though each community has its own spiritual and theological grounding for the practice.

The term “contemplation” has a theological definition that orients how Trappists and other Christian monastics dwell in place. Contemplation is described here in terms of its relationship to two other important components of the spiritual landscape—the aesthetic and the ascetic. First, the contemplative (apophatic) perspective is a counterpart of the aesthetic (kataphatic) (Lane Citation2002; Keating Citation2006). The aesthetic approach relies upon imagery and other meaningful sensory and emotional experiences that provoke an active spiritual state of mind in a landscape. The contemplative state is the yin to the aesthetic yang. It symbolizes darkness and receptivity, as opposed to light and action or ambition. Contemplation refers to the receptive practice of unknowing, the realization and acceptance that the person “no longer knows what God is” (Merton Citation1961; original emphasis). Contemplation deviates from aesthetics by stressing the dismissal of material, social, intellectual, and emotional distractions (Merton Citation1961). This viewpoint is embedded in The Cloud of Unknowing, written by an anonymous fourteenth‐century mystic, who stated, “Center all your attention and desire on [God] and let this be the sole concern of your mind and heart. Do all in your power to forget everything else, keeping your thoughts and desires free from involvement with any of God's creatures or their affairs” (Anonymous Citation2014, 40). The experience implies a full immersion into an interior state where a person and God are existentially united.

Another dynamic aspect of the spiritual landscape is asceticism, which is closely related to contemplation. Both concepts are inextricably linked to the monastic life (Meninger Citation2005), but have also been competing ideals in the history of the Trappist order (Merton Citation1949). Asceticism has been defined as a tool to discipline the body as a way to focus on the contemplation of God rather than worldly aspects (Merton Citation1949; Jonveaux Citation2011; Abbruzzese Citation2014). Asceticism can include quantitative restrictions in diet (such as fasting or abstaining from meat), reduced sleep, and bodily mortification, which tends to occur less frequently today than in the past (Jonveaux Citation2011). Asceticism, as an embodied practice, may provide useful steps to grow in contemplation, but that is not a guarantee (Merton Citation1949, Citation1955). The history of American Trappist monasteries provides a number of illustrations for the dynamic relationship between contemplation and asceticism, as well as with a variety of other influences on the spiritual landscape.

The Spiritual Landscape in Historical Context

Origins of Trappists (1098‐1798)

The spiritual landscapes of American Trappist monasteries are a composite of historical meanings that date back to the beginning of the Cistercians. The history of the Trappist order was characterized by pressures such as business‐as‐usual practices versus institutional reforms, unyielding ambitions of monastic leaders, exclusionary activities, overworking, missionary zeal, place disruption, and “athletic” feats of asceticism. Changing historical contexts and conditions affected how certain aspects of the spiritual landscape were prioritized over others. Thomas Merton's version of early Trappist history depicted contemplation as though it were in a state of dormancy, a feature that he identified as a significant failure of the order's past (1949). Contemplation, as it was represented in historical accounts, appeared to blend into the background of the spiritual landscape until the twentieth century.

The early history of Trappist monasteries echoes Jones's assertion that spiritual landscapes are sites of unpredictability, contestation, and regeneration (2017). The Trappists are a reformed branch descending from a larger ancestral order, the Cistercians, a group that also emerged out of monastic reforms. The story of the Cistercians begins in 1098 France with attempts by Christian monks to reinvigorate the original values of asceticism and structure in monastic life. During that year, the initial group of twenty‐one monks, led by Robert of the Benedictine Abbey of Molesme, AD 1027–1111, founded Cîteaux Abbey, the first Cistercian monastery (Bell Citation2000). The members of this monastery desired a stricter, “to‐the‐letter” observance of the The Rule of St. Benedict (Citation1982), a key text which structures everyday religious life of Catholic monastics (Pennington Citation1995; Lawrence Citation1989). To provide historical perspective, the European and New World landscapes were completely different places. Cîteaux Abbey was founded around the same period when the Cahokia peoples were building the largest prehistoric earthen structure on North America—Monk's Mound, located in Illinois, less than ten miles from the present‐day downtown area of St. Louis, Missouri (this concurrence will become relevant later) (Thomas Citation1907).

Adding to the desire for reform and renewed asceticism, the charisma and biases of early Cistercian leaders motivated how monasteries were shaped socially and institutionally. The Cistercians grew significantly through charismatic contemplative figures like St. Bernard of Clairvaux (AD 1090–1153) during the twelfth century (Lawrence Citation1989). The “strict adherence” that inspired Cistercian reform would compensate for the perceived lack of austere asceticism in the monasteries operated by the Order of St. Benedict (OSB) (Pennington Citation1995). Such austerity came in the form of intense displays of poverty, regular and more extreme fasts, rejection of all kinds of aesthetic expression in architecture, and acts of detachment further from the outside world. The Cistercians would not necessarily keep to that letter, which provoked centuries of dissent and attempted reformations (Lawrence Citation1989). Nuns were originally excluded from the order, but they began adopting the Cistercian ideals in 1120 (Pennington Citation1995); their numbers propagated substantially during the thirteenth century, until they were subjected to temporary prohibition of new foundations in 1228, once female monasteries began to outnumber the males (Lawrence Citation1989). The Cistercian spiritual landscape was characterized by the growing acceptance of asceticism, met with some blatant instances of gender‐based exclusion. Twentieth‐century monastic landscapes, by contrast, would characterize a relatively greater emphasis on contemplative spirituality and deinstitutionalization (de Groot and others Citation2014).

From the eleventh century until the seventeenth, Cistercian monasteries cultivated political power and privilege, but were prone to being lackadaisical in terms of contemplation and asceticism (Merton Citation1949; Krüger Citation2008). This period reflects an ambivalence toward what J.D. Dewsbury and Paul Cloke might call “false spiritualization” (2009). A monk like St. Bernard, despite being a renowned contemplative, became a central figure in European politics (Lekai Citation1977). C.H. Lawrence summed up the irony of the situation, “An order that had originated in a protest against monastic wealth and grandeur and had placed apostolic poverty in the forefront…had by the end of the twelfth century acquired…an unenviable reputation for avarice and group acquisitiveness” (1989, 198). Once again, following Jones, the Cistercian spiritual landscapes that rose out of disagreement became sites of further reform (2017). In seventeenth‐century France, this realization triggered a polarization among Trappists between business‐as‐usual and returns to stricter approaches. Single monasteries would instigate reforms against the parent body (Merton Citation1949).

By the mid‐1600s, over sixty monasteries adopted a back‐to‐basics observance of The Rule of St. Benedict (Citation1982), contrasting with the Cistercian customs at the time (Merton Citation1949; Lekai Citation1977). By 1666, Pope Alexander VII intervened to create two forms of Cistercian observance, the common and strict (Lekai Citation1977; Bell Citation2000). In the same year, Armand‐Jean le Bouthillier de Rancé assumed the role as abbot at La Trappe, the monastery from which the Trappists and Trappistines got their name. La Trappe effectively became the symbol for Cistercian reform and the development of the OCSO during the seventeenth century and thereafter (Merton Citation1949). Merton recognized one important result of La Trappe: it “reintegrated the monastic life by reviving that asceticism without which sanctity and contemplation are impossible” (1949, 47). La Trappe, however, reflected the zeal, exaggerated asceticism, and restlessness of its leader. Rancé viewed the monastery as a prison where the monks were to spend their lives enduring severe penances (Lekai Citation1977). Asceticism under Rancé became an end in itself rather than a path to contemplation.

Merit‐based asceticism continued to hold high spiritual priority after the Trappists were displaced during the French Revolution. Napoleon's increasing power led to severe place disruptions for French Trappists and other religious groups. The government authorized suppression and confiscation of monasteries and religious houses in France (Merton Citation1949; Bell Citation2000). On 1 June 1791, a group of the early Trappist monks fled to Switzerland to establish a new community named La Val Sainte, a forced migration led by Dom Augustin de Lestrange (Lekai Citation1977). At La Val Sainte (or Valsainte), the domineering Dom Augustin instituted athletic acts of asceticism and bodily mortification, including restricted diets, reduced sleep, and increased manual labor. The refugee status of the Valsainte monks only drove them deeper into intense ascetic practice (Lekai Citation1977).

The final dispersal of monks happened in March 1793 when the French authorities required that they either swear allegiance to the government or face deportation or imprisonment (Merton Citation1949). In Switzerland, the refugee Trappists soon accommodated Cistercian nuns, who became the first Trappistines in 1796 (Lekai Citation1977; Krüger Citation2008). Napoleon invaded Switzerland in 1798, which pushed the Trappists and other orders to places outside of the country—an “abbey‐on‐wheels, a logistic feat that allegedly stupefied even the great Napoleon” (Lekai Citation1977, 183). This move provoked Dom Augustin to consider seeking sites of refuge in other countries, including the United States (Merton Citation1949; Lekai Citation1977). Through these historical accounts, it becomes evident that these spiritual landscapes were the stages for a dynamic range of phenomena, including multiple attempts at reform, differing degrees of political and economic power, international displacement, and intense expressions of asceticism. Contemplation, on the other hand, appeared to take on latent and symbolic role in the spiritual landscape, rather than a fundamental tenet of the Trappist order.

Trappist Monasteries in the American Scene

The effects of political displacement, intense ascetic feats, and a relatively dormant contemplation were carried over in colonies of Trappists migrating to the New World. These traits were combined with growing restlessness and missionary desires brought about by virtue of being Christians in the New World (see Monson Citation2013). Some of the first Trappists, however, did not arrive in the Americas for the purpose of colonizing and creating foundations. During the French Revolution, some monks were arrested in France and interned in French Guiana. One La Trappe monk was on a prison ship intercepted by the H.M.S. Indefatigable, which granted the freedom to the ship's prisoners and took them to Plymouth (Merton Citation1949). The Trappists’ first encounters with the North and South American scene were ones not by vocation to the contemplative life, but by force.

The first two foundations of refugee Trappists in the American scene were deemed failures (Lekai Citation1977). Merton (Citation1949) and Lawrence Flick (Citation1886) observed this outcome more as a problem prioritizing asceticism, active work, and missionary ambitions over contemplative values. This impression reflects Merton's understanding that “contemplation can never be the object of calculated ambition” (1961, 10). A colony of forty Trappists were led by Dom Urban Guillet from La Val Sainte to Baltimore, Maryland, in search of a place to build a monastery. They set their sights in Kentucky (Merton Citation1949). The monks reached the state malnourished, but ended up purchasing 800 acres of land in 1806 along Casey Creek. According to Merton, they tended to dedicate much of their time toward work rather than spiritual development, setting up a local school and establishing themselves as watchmakers. Guillet was a sociable young monk who was dissatisfied with their present Kentucky. He was evidently on the lookout for opportunities to move the community to where they could evangelize among American Indians. Flick described Guillet's restless nature, “Father Urban had not yet learned wisdom nor forsaken his Bohemian ways” (1886, 19). With that said, Guillet and his Trappists were not the only Catholic monks with ambitions to evangelize early America; the Benedictine monks also had a zealous missionary appetite (Monson Citation2013).

When the Casey Creek monastery burned down in 1808, the monks, prompted by the impatient Guillet, moved again even before the Kentucky settlement was officially established. The monks settled among the burial mounds of Cahokia, Illinois. There, they endured typhoid fever and the 1812 New Madrid earthquake. In 1813, the Cahokia monastery, Our Lady of Good Counsel, was called to pack up for a rendezvous with the newly arrived colony led by Dom Augustin in New York (Merton Citation1949). A prominent place name remains, leaving a ghostly footprint of the former Trappist spiritual landscape—Monks Mound (Garraghan Citation1925; Flick Citation1886). In New York, the monks took over a school once owned by the Jesuits, located on what is now Fifth Avenue. After Napoleon was captured, the American transplants returned to France (Merton Citation1949). Initial attempts to create an American spiritual landscape were hindered by the intersections of ambition, evangelism, finding work, and movement.

The first successful Trappist monastery in the New World was Petit Clairvaux in Nova Scotia (Lekai Citation1977). Around 1821, the monastery began as a small community of three Trappistine nuns and Father Vincent de Paul Merle, a monk who was fanatical about converting American Indians and the only remaining Trappist after the community left for Europe in 1814. Petit Clairvaux was authorized to become a monastery around 1823 (Flick Citation1886; Lekai Citation1977). In 1848, a colony of monks journeyed from France to New Orleans. There, the monks took the ‘Martha Washington’ big river steamer to Kentucky and established the second successful monastery: the Abbey of Gethsemani (Merton Citation1949). In 1849, a group of sixteen members from the Irish Melleray Abbey crossed the Atlantic and traveled up the Mississippi to join some explorer monks in establishing New Melleray Abbey in Dubuque, Iowa; six of these founding members were plagued with cholera and died during the journey (Perkins Citation1892). New Melleray and Gethsemani currently remain in operation.

Nearing the end of the nineteenth century and entering the twentieth, the Trappists confronted struggles to achieve a lasting imprint on the American scene through a series of ill‐fated and unsuccessful foundations. Our Lady of the Holy Spirit (1862–1872), a Quebec daughter house of Petit Clairvaux, attempted to start the monastery of the Immaculate Conception in Old Monroe, Mo. around 1867. Immaculate Conception was eventually abandoned in 1875, partly due to ideological tensions between the local community and the monks (Merton Citation1949). In 1904 Oregon, a group of Trappist monks arrived from France to escape the anti‐religious French political climate of the time. They began the monastery of Our Lady of Jordan, with hopes of installing a large sawmill to take advantage of the local timber industry (Merton Citation1949). Ultimately, the Oregon community dissipated by 1910 because it accrued too much debt, lost its uninsured sawmill to a fire, and lacked an adequate number of novices and postulants (Hannum Citation2001; Langlois Citation2004). Though it did not last beyond 1919, the Canadian Petit Clairvaux imparted a lineage of U.S. monasteries, including Our Lady of the Valley in 1900 in Rhode Island, which burned down on 21 March 1950 (Greely Daily Tribune Citation1950). In that same year, the displaced Valley monks were instrumental in forming St. Joseph's Abbey located in Spencer, Massachusetts. (Bertoniere Citation2005).

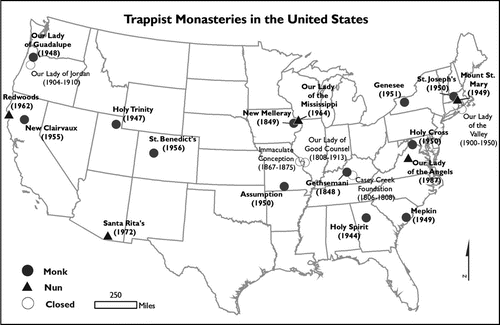

Spiritually, the twentieth century saw a pendulum shift from the previous athletic asceticism to a revival of the contemplative perspective (Lekai Citation1977). By the middle of the twentieth century, new scholarly journals and interest in Cistercian monasticism were met with a growth in Trappist vocations (Lekai Citation1977). The post‐World War II era of the 1940s and 50s (especially 1948–1951) witnessed an upsurge in the establishment of monasteries, as well as a renewed commitment to contemplation (Merton Citation1949; Downey Citation1997; Figure 1). The Abbey of Gethsemani, in particular, served as a model for contemplative landscapes. It was also the cloister of Thomas Merton (1915–1968), perhaps the most well‐known American Trappist monk and popularizer of contemplative spirituality (Lekai Citation1977). Monasteries had a literary template for integrating contemplative spirituality into everyday place‐making, through books like Merton's autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain ([1948] Citation1999). Merton's contemplative perspective spread throughout popular religious culture and appeared widely in Catholic periodical advertisements (The Catholic Advance Citation1951).

The renaissance of contemplative practices was met with a rising tide of new Trappist monasteries (Merton Citation1949). For example, between 1944 and the end of 1956, the number of monasteries exploded with eleven new establishments in the American scene (Lekai Citation1977). Gethsemani alone created five additional American monasteries located in Georgia, Utah, South Carolina, New York, and California (Merton Citation1949). This increase happened around the time when soldiers were coming back from World War II. The influx of monasteries and entering novices corresponded with an overall “church boom,” renewed popularity in monastic life, and a virtual “updating” of Catholic teachings and policies (Sopher Citation1967, 108). Monks founded the majority of American Trappist monasteries. While Trappistines were among the first OCSOs in North America, they instituted a strong presence in the United States during the second half of the twentieth century, with the openings of Mount St. Mary Abbey (Massachusetts 1949), Redwoods Abbey (California 1962), Our Lady of the Mississippi, Santa Rita's Abbey (Arizona 1972), and Our Lady of the Angels (Virginia 1987).

Throughout the history of American Trappist monasteries, these spiritual landscapes sustained elements from Old World communities. Regardless, the New World allowed for additional expressions of the spiritual landscape, ranging from colonial evangelism to the recent embracement of contemplation. Contemplation has had its ebbs and flows according to the values and inhibitions of monastery leaders. Though the contemplative idyll remains a mainstream topic, it comes up against contemporary tensions, pressures, and redefinitions. The next section shows how contemplation as a quality of the spiritual landscape becomes more apparent, yet remains exposed to emerging ambiguities and ambivalences.

Openness and Cloister

The monastery has been described as “a laboratory of confrontation, as well as of the restructuring of the relationships between Christianity and modernity” (Hervieu‐Léger Citation2014, 21). Physical solitude and sensorial silence have been identified as important circumstances for pursuing the contemplative life. In American Trappist spiritual landscapes, the contemplative idyll is challenged by the relationship between openness and cloister—the balance between solitude, or rejection of the world, and the necessity for involvement with people and places outside the cloister of the monastery (Merton Citation1961, Citation1971). Regardless of this contradictory relationship, Merton argued the importance of an openness for contemplative communities, to blend the contemplative life with contemporary reality, as well as encouraging outside individuals to experience a deeper contemplative connection to the monastery. Reverting to the laboratory metaphor, Hervieu‐Léger viewed Catholic monasteries as experimental in their confrontation of modernity for two reasons: they have a certain degree of autonomy from the Catholic Church and they possess network connections to places outside of their boundaries (2014). From a geographer's standpoint, Relph's “openness of place” appropriately fits this situation (2017). The openness of place considers a landscape's connectedness to other places and extension to broader regional and global contexts. While an openness of place can be vital to the sustainability of Trappist landscapes, it can also complicate or redefine contemplation's presence in the spiritual landscape. In other ways, it may provide opportunities for contemplative outreach. This section discusses the openness of place among five spiritual landscapes: Abbey of Gethsemani, New Melleray Abbey, Assumption Abbey, St. Benedict's Monastery, and Our Lady of the Mississippi Abbey.

There exists a range of remoteness among these five monasteries. The condition stems back to when the father of Western monasticism, St. Benedict, escaped from the urban city of Rome to a cave, later becoming an abbot and writing The Rule of St. Benedict (Benedict Citation1982; Tvedten 2006). Both New Melleray and Our Lady of the Mississippi are located in close proximity of each another in Dubuque County, Iowa, a short drive to the downtown county seat bearing the same name. St. Benedict's Monastery is tucked away within a basin of the Rocky Mountains, a landscape that provides a physical barrier of isolation from the nearby tourist destinations of Aspen and Snowmass. Gethsemani and Assumption Abbey are more remote, by comparison. Assumption Abbey, in particular, is located deep within the Missouri Ozark foothills, simply has a series of road signs with the word “MONASTERY” and an arrow indicating the general direction. The writer William Classen shared his experience driving to the monastery:

At the county road sign, I flip on the turn signal and pull off onto a narrow two‐lane road that climbs into the Ozark foothills. The blacktop curls and dips and swerves, weaving its way through the brown and gray rural terrain. Occasionally I drive past a house surrounded by a picket fence, or a mobile home partially hidden by the oncoming darkness. The drive feels longer than usual. I've been told that Assumption Abbey is the most remote Trappist monastery in the United States.

Classen's description of the southern Missouri drive denotes the feeling of remoteness that can be experienced when entering a monastery—or simply trying to find it. The writer's sense of isolation is fueled by the long drive and the oncoming darkness of an ending day. These degrees of remoteness have altered over time according to changes in the surrounding communities.

Regardless of the physical remoteness, all five monasteries are subjected to multiple forms of social openness and availability. American Trappist monasteries, like other Catholic monastic communities, have had conflicts with the extent to which they make themselves available through social media, events, publications, and other outlets. An openness of place possesses some obvious challenges to idealized contemplative place‐making. A greater social openness of place can impair the conditions of privacy and solitude that the traditional idyll of contemplation upholds (Merton Citation1961). On the other hand, the increased availability of Trappists in the public realms has redefined contemplation as a more inclusive spiritual component of the landscape. Monastic spirituality, on the whole, is becoming more pluralized and deinstitutionalized (de Groot and others Citation2014).

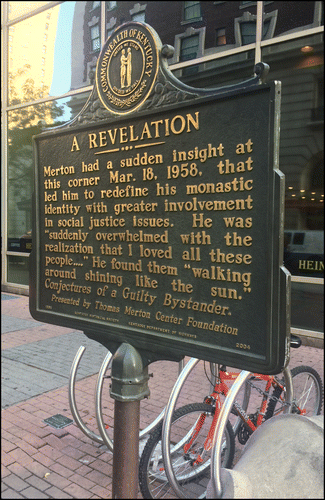

Perhaps the most important long‐term openness of the American Trappist monastery has been through the publications of important contemplative figures, such as Gethsemani's Thomas Merton. The books of this Kentucky monk and those of many other Trappists and Trappistines continue to attract people to the connecting with the American Trappist landscape and contemplative way of life. Merton's autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain (originally published in 1948), has prompted the vocations of many Catholic monastics. His writings have also influenced people of other religious and spiritual beliefs (Giroux Citation1998). The Abbey of Gethsemani was the landscape in which Merton began to form his ideas about contemplative spirituality and Catholicism's connections to Zen Buddhist teachings (Pearson 2014). For this reason, the abbey has become a significant pilgrimage site for religious and lay people to visit. Merton's influence has left its mark on landscapes beyond the monastery perimeter. For example, in Louisville, Kentucky, a monument stands at the intersection of Muhammad Ali Boulevard and Thomas Merton Square (Figure 2). The sign is situated where the monk was standing when he had a revelation on 18 March 1958. The monument recounts that Merton experienced a profound realization that he loved all of the people walking on that street. This sentiment catalyzed Merton's work in social justice and redefined contemplation in the context of larger systemic societal problems (see Merton Citation1971).

Figure 2. Monument dedicated to Thomas Merton in downtown Louisville, KY (photograph by the author, July 2017).

Though Merton was important, he was not the only Trappist to have had a remarkable influence on opening the contemplative experience of the monastery to larger scales. Thomas Keating represents another influential monk who popularized the contemplative practice of Centering Prayer, which is a Christian form of meditation (Keating Citation2006). In the 1970s, Keating, Basil Pennington, and William Menninger, monks at St. Benedict's Monastery, helped establish an influential organization dedicated to advocating Trappist monastic spirituality, called Contemplative Outreach. The group currently serves over 40,000 people, has over 120 active chapters in 39 countries, and provides support to over 800 prayer groups. Over the years, the group, under the guidance of Keating, has been instrumental in interfaith dialogue, as well. St. Benedict's Monastery has been the site of the Snowmass Interreligious Conference, an annual event that began in fall 1983 and continues to meet every spring (Contemplative Outreach Citation2017). Contemplative Outreach represents one illustration of a greater trend for monasteries to become more colloquial spiritual centers rather than places of strict religious adherence (see de Groot and others Citation2014).

The Internet and social media platforms like Facebook have served to increase the visibility of Catholic monasteries, but sometimes to the detriment of monastic contemplative and ascetical practices (Jonveaux Citation2013). All five American Trappist monasteries visited in this research currently maintain a website. Four of the five monasteries (excluding Our Lady of the Mississippi) have either an official or unofficial Facebook page. Members of four monasteries (excluding Assumption Abbey) operate a YouTube account where they post videos. These websites and social media profiles act as digital entries into the monastic spiritual landscape, especially for individuals interested in learning more about the monastery, as well as folks who might be discerning a vocation to monastic life. These websites and social media profiles can also contain information on how to purchase products being sold by a particular monastery.

The social availability does not end at the Internet domain. The openness of the Trappist monastery extends to television and cinema, a feature that is also experienced by other Catholic monastic orders (see Hervieu‐Léger Citation2014). For example, the Trappistines of Our Lady of the Mississippi Abbey opened up their cloister to a reality TV show, entitled The Monastery, a series between 2003 and 2007, which focused on four different monasteries in the U.K. and the U.S. Five women from diverse spiritual and religious backgrounds entered Our Lady of the Mississippi in January 2006 and lived with the sisters for forty days. In the four‐part series, the women were confronted with the difficulties of monastic living. They also learned about contemplative spirituality from the position of the OCSO. The Trappistines’ segment was never aired, but the monastery had been given permission to circulate copies of the four‐episode series (Our Lady of the Mississippi Citation2006). Despite never being aired on television, this example demonstrates how modern media has redefined the accessibility of the Trappist cloister and the contemplative ideals.

Similarly, Thomas Keating of St. Benedict's became the subject of a documentary, entitled Thomas Keating: A Rising Tide of Silence, directed by his nephew, Peter C. Jones (Citation2014). The biopic detailed Keating's role as one of the principal founders of the Centering Prayer movement and Contemplative Outreach. The documentary was not simply a history of Keating's life. It also provided a glimpse into the modern gravity of Trappist contemplation and how the practice began to blend with Eastern spirituality after the mid‐twentieth century. The film gained national recognition (Bale Citation2014) and even progressed to the first round of documentary nominations for the Oscars, though the monk did not ultimately take home an award (Hassler Citation2015).

Changing contexts result in changing levels of outside accessibility to the American Trappist landscape. One example of this changing accessibility is through lay orders. Books like Benedictine Brother Benet Tvedten's How to Be a Monastic and Not Leave Your Day Job champion the ability for lay people to feel like they are part of the monastery (2013). Visitors, often of different belief systems, describe strong experiential connections when they participate in personal and group retreats at Trappist monasteries, so much to the point where they may want to take next steps in their identification with the spiritual landscape (see Classen Citation2007; Hervieu‐Léger Citation2014). In some cases, outsiders may become “third order oblates,” or lay members of the monastery (Tvedten Citation2013). For the most part, oblates have been present in varying degrees throughout Cistercian history (Lekai Citation1977). Lay members were even present during the first attempted Trappist foundation in Kentucky (Merton Citation1949). The inclusion of oblates has helped monasteries of various Catholic orders build a strong supportive community, especially during times when the number of entering monks is low (see Jamroziak Citation2010). Assumption Abbey has accepted oblates in the past (Citation2018). In Iowa, Our Lady of the Mississippi Abbey and New Melleray Abbey have teamed up to create a group of lay associates in 1995 called the Associates of Iowa Cistercians (O'Neill Citation2015). Kentucky's Trappists have their own Lay Cistercians of Gethsemani Abbey (Citation2018). Overall, lay orders necessitate an increased openness of the monastery for visitors to feel like they belong without having to take vows to become a monk or nun. While some Trappist monasteries have allowed oblates, others, like St. Benedict's Abbey, only provide accommodations for temporary guests.

One occasion existed in which the rules were bent for an individual who wanted to become a Trappist, but was physically restricted from that place. W. Paul Jones, a hermit living on the monastery property of Assumption Abbey, told the story of his relationship with a convicted murderer named Clayton Fountain (2011). This prisoner was serving life in prison for a series of five murders. Through Jones’ spiritual advisement, Fountain underwent a 180‐degree conversion to Catholicism and was able to take the steps necessary to become a Trappist hermit of Assumption Abbey without stepping foot on the monastery soil. Fountain adopted the contemplative lifestyle and created a hermitage out of his cell during his life of solitary confinement. Though he died before hearing his official acceptance as a full monk, the prisoner was buried at the monastery's cemetery. The above examples show that contemplation's reach has gone beyond the perimeter of the monastery to include new spatial and digital contexts. The increased social openness, availability, and inclusiveness of American Trappist monasteries have led to the recasting of contemplation as an entryway for place‐making among nonmonastics.

Embracing Ambiguity in Spiritual Landscapes

I came there looking for my brother. They told me, “Try that little building over there.” Well, I had tried every place else, so I went.

Strangest thing—so small outside, it was vast inside, and sure enough, I found my brother there.

The interior immensity of the monastery that Theophane Boyd (Citation1981) described above could be seen as analogous to the vastness of the spiritual landscape. This paper demonstrates that American Trappist monasteries are a composite of dynamic historical contexts and various forms of spiritual expression. Therefore, it can be difficult to predict, according to Jones, exactly how a spiritual landscape might be created, reinvented, or forgotten (2017). Contemplation represents one example of how a significant aspect of the spiritual landscape can acquire different meanings. By understanding the historical nuances of American Trappist monasteries, it becomes apparent that the virtue of simply being at a monastery, for instance, cannot be viewed as the equivalent to attaining a profound contemplative experience. As Lane noted, a sacred landscape can be encountered, but that does not mean that a person will attain a heightened spiritual awareness while in that place (2002). Even Thomas Merton's spiritual conception of place continued to reshape as he lived out his years at Gethsemani before dying while travelling in Thailand (Pearson Citation2016).

Three important limitations of this paper exist, which may give rise to future possibilities. First, this study points out some of the ambiguities and ambivalences, but by no means claims to provide a comprehensive survey of the spiritual landscapes of American Trappist monastery. Some examples of further inquiry include examining the changing spiritual elements of American Trappist architecture, as well as the conflicted relationship between work and contemplation in Trappist monasteries (see Jonveaux Citation2014). Furthermore, a wider range of voices ought to be incorporated, including those of contemporary Trappists, Trappistines, visitors from different spiritual backgrounds, and others. This paper draws heavily from the work of Thomas Merton, whose writings not only capture the words of an authority on contemplation, but also contribute just one dimension to the story of what might constitute “authentic” spiritual practice and what might not. Regardless, Merton's work continues to acquire fresh interpretations and has gained an invigorated relevance to geography in a special issue of The Merton Annual, entitled “Thin Places and Thick Descriptions” (Raab Citation2016).

Second, due to the broadness of this paper, parts of it involve discussing the spiritual landscapes of American Trappist monasteries out of the depth of their original circumstances. As such, it is imperative to recognize that each monastery possesses its own context and peculiarities. In‐depth case studies, similar to Francesca Sbardella's ethnographic work among Carmelite nuns, are encouraged to expand upon, add to, or challenge the very ideas of this paper (2014).

Third, the pluralized nature of contemplation in the spiritual landscape cannot be limited to the scope of one monastic order in Roman Catholicism. Other spiritual and religious traditions employ contemplation in a myriad of other ways (Fracchia Citation1979), which could serve as the basis for future comparative studies. These three limitations, while significant, exist beyond the scope of this paper.

In addition to the unpredictability of encountering the spiritual at a Trappist monastery, there remains an unpredictability for how long some monasteries may last. Though monasteries have a global presence, their futures have been a point of uncertainty for religious scholars (see Jonveaux Citation2017). In Europe and North America, monasteries have been subjected to closing due to aging members and lack of vocations. By comparison, Asia and Africa have a higher proportion of younger vocations (Jonveaux Citation2017). The contemporary monastic presence risks being reduced to a folkloric state (Hervieu‐Léger Citation2014). Since 2013, Assumption Abbey has been in the process of transitioning over to monks from a monastery in southern Vietnam (Schuessler Citation2015). While many monasteries have been able to reinvent themselves, others struggle in the midst of globalization and secularization (Jonveaux Citation2017).

Contemplation can represent, from a geographer's point‐of‐view, a receptive and spiritualized form of place‐making. The concept also provides an entrance into exploring the harmonies and disconnects between the ideal and real, traditional and contemporary, openness and cloister in spiritual landscapes. Regardless of being in transition and relative decline, William Meninger justifiably wrote “monastic spirituality will always have its place” (2005, 2).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Thomas Barclay Larsen

Thomas Barclay Larsen is a doctoral student of geography at Kansas State University in Manhattan, Kansas, USA; [[email protected]]

Notes

1. Hereafter, “Trappist” is used as a general reference to all monasteries and members of the OCSO. “Trappistine” is applied when specifically referring to nun‐led monasteries.

References

- Abbruzzese, S. 2014. Monastic Asceticism and Everyday Life. In Annual Review of the Sociology of Religion Volume 5: Sociology and Monasticism, Between Innovation and Tradition, edited by I. Jonveaux, S. Palmisano and E. Pace, 3–20. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Anonymous. 2014. The Cloud of Unknowing and the Book of Privy Counseling, edited by W. Johnson. New York: Image.

- Appleby, R. S. 2000. The Ambivalence of the Sacred: Religion, Violence, and Reconciliation. Lanham, Md.: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Assumption Abbey. 2018. External Oblates. Assumption Abbey. [http://www.assumptionabbey.org/oblates.asp].

- Bale, M. 2014. Breaking Silence on a Monk: ‘Thomas Keating’ Follows a Life from Affluent to Austere. New York Times. [https://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/11/movies/thomas-keating-follows-a-life-from-affluent-to-austere.html]. 10 April.

- Benedict. 1982. The Rule of St. Benedict in English, edited by T. Fry. Collegeville, Minn.: The Liturgical Press.

- Bell, D. N. 2000. Trappists. In Encyclopedia of Monasticism, edited by W. M. Johnston, vol. 2, 1298–1300. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn.

- Bertoniere, G. 2005. Through Faith and Fire: The Monks of Spencer 1825–1958. New York: Yorkville Press.

- Boyd, T. 1981. Tales of a Magic Monastery. New York: Crossroad.

- Buttimer, A. 2017. Nature, Place, and the Sacred. In Place and Phenomenology, edited by J. Donohoe, 59–74. New York: Rowman and Littlefield.

- The Catholic Advance. 1951. Advertisement of Thomas Merton's Seven Storey Mountain. Wichita, Kans. 9 February.

- Classen, W. 2007. Another World: A Retreat in the Ozarks. Lanham, Md.: Sheed & Ward.

- Connor, M. 1972. The De Instituto Christiano: Reflections on Contemplative Community. In Contemplative Community: An Interdisciplinary Symposium, edited by M. B. Pennington, 47–60. Washington, D.C.: Cistercian Publications Consortium Press.

- Contemplative Outreach. 2017. Main Page. Butler, N.J.: Contemplative Outreach Ltd. [http://www.contemplativeoutreach.org/].

- de Groot, K., J. Pieper, and W. Putman. 2014. New Spirituality in Old Monasteries? In Annual Review of the Sociology of Religion Volume 5: Sociology and Monasticism, Between Innovation and Tradition, edited by I. Jonveaux, S. Palmisano and E. Pace, 107–130. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Dewsbury, J. D., and P. Cloke. 2009. Spiritual Landscapes: Existence, Performance and Immanence. Social and Cultural Geography 10 (6):695–711.

- Downey, M. 1997. Trappist: Living in the Land of Desire. Mahwah, N.J.: Paulist Press.

- Flick, L. F. 1886. The French Refugee Trappists in the United States. Philadelphia: D. J. Gallagher.

- Fracchia, C. A. 1979. Living Together Alone: The New American Monasticism. San Francisco, Calif.: Harper and Row.

- Garraghan, G. J. 1925. The Trappists of Monks Mound. Illinois Catholic Historical Review 8 (2):106–136.

- Giroux, R. 1998.Thomas Merton's Durable Mountain. The New York Times. [http://www.nytimes.com/books/98/10/11/bookend/bookend.html]. 11 October.

- Greeley Daily Tribune. 1950. 2‐Million‐Dollar Fire Destroys 50‐year‐old Trappist Community. Greeley, Colo. 22 March.

- Hannum, K. 2001. Stable, Rural Parish Community Maintains Solid Catholic Traditions and History. Catholic Sentinel. [http://www.catholicsentinel.org/Content/News/Local/Article/Stable-rural-parish-community-maintains-solid-Catholic-traditions-and-history/2/35/6415]. 20 September.

- Hassler, L. 2015. Thomas Keating: The Monk Who Went to the Oscars (Almost). Huffington Post. [https://www.huffingtonpost.com/linda-hassler/thomas-keating-the-monk-w_b_6781120.html]. 3 March.

- Hervieu‐léger, D. 2014. Virtuosity, “Folklorisation” and Cultural Protest: Monasticism as a Laboratory of the Confrontation between Christianity and Modernity. In Annual Review of the Sociology of Religion Volume 5: Sociology and Monasticism, Between Innovation and Tradition, edited by I. Jonveaux, S. Palmisano and E. Pace, 21–33. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Jamroziak, E. 2010. Spaces of Lay‐Religious Interaction in Cistercian Houses of Northern Europe. Project Muse 27 (2):37–58.

- Jones, L. 2017. The Ambiguity of “Sacred Space”: Superabundance, Contestation, and Unpredictability at the Earthworks of Newark, Ohio. In Place and Phenomenology, edited by J. Donohoe, 97–124. New York: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Jones, P. C. 2014. Thomas Keating: A Rising Tide of Silence [Motion Picture]. Snowmass, Colo.: A Rising Tide of Silence LLC.

- Jones, W. P. 2001. A Table in the Desert: Making Space Holy. Brewster, Mass.: Paraclete Press.

- Jones, W. P. 2011. A Different Kind of Cell: The Story of a Murderer Who Became a Monk. Grand Rapids, Mich.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing.

- Jonveaux, I. 2011. Asceticism: An Endangered Value? Mutations of Asceticism in Contemporary Monasticism. Religion and the Body 23:186–196.

- Jonveaux, I. 2013. Facebook as a Monastic Place? The New Use of the Internet by Catholic Monks. In Annual Review of the Sociology of Religion Volume 5: Sociology and Monasticism, Between Innovation and Tradition, edited by I. Jonveaux, S. Palmisano and E. Pace, 87–106. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Jonveaux, I. 2014. Redefinition of the Role of Monks in Modern Society: Economy as Monastic Opportunity. In Annual Review of the Sociology of Religion Volume 5: Sociology and Monasticism, Between Innovation and Tradition, edited by I. Jonveaux, S. Palmisano and E. Pace, 71–86. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Jonveaux, I. 2017. Does Monasticism Still Have a Future? Demographical Evolution and Monastic Identity in Europe and Outside Europe. In Monasticism in Modern Times, edited by I. Jonveaux and S. Palmisano, 46–62. New York: Routledge.

- Keating, T. 2006. Open Mind, Open Heart, 20th Anniversary Edition. New York: Bloomsbury.

- Krüger, K. 2008. Monasteries and Monastic Orders: 2000 Years of Christian Art and Culture. Königswinter, Germany: Hf Ullmann.

- Lane, B. C. 2002. Landscapes of the Sacred: Geography and Narrative in American Spirituality. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Langlois, E. 2004. Trappists recall the monastery that was. Catholic Sentinel. [http://www.catholicsentinel.org/MobileContent/News/Local/Article/Trappists-recall-the-monastery-that-was/2/35/1401]. 21 October.

- Lawrence, C. H. 1989. Medieval Monasticism: Forms of Religious Life in Western Europe in the Middle Ages, 2nd ed. New York: Longman.

- Lay Cistercians of Gethsemani Abbey. 2018. Home. Lay Cistercians of Gethsemani Abbey. [https://laycisterciansofgethsemani.org/].

- Lekai, L. J. 1977. The Cistercians: Ideals and Reality. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press.

- Ludueña, G. A. 2008. Tradition and Imagination in the Creation of a New Monastic Model in Contemporary Hispanic America. International Journal for the Study of the Christian Church 8 (1):43–55.

- Meijering, L., P. Huigen, and B. van Hoven. 2007. Intentional Communities in Rural Spaces. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 98 (1):42–52.

- Meninger, W. 2005. 1012 Monastery Road, 2nd ed. New York: Lantern Books.

- Merton, T. 1949. The Waters of Siloe. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company.

- Merton, T. 1955. No Man Is an Island. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

- Merton, T. 1961. New Seeds of Contemplation. Norfolk, Conn.: New Directions.

- Merton, T. 1971. Contemplation in a World of Action. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday and Company.

- Merton, T. 1999. The Seven Storey Mountain, Fiftieth Anniversary Edition. New York: Harvest.

- Monson, P. G. 2013. The Sacramental Vision of America's Early Benedictine Monks. American Catholic Studies 124 (3):45–59.

- O'neill, K. 2015. A Life of Hope: Our Lady of the Mississippi Abbey. Dalton, Mass.: The Studley Press.

- Olszewska, A. A., P. F. Marques, R. L. Ryan, and F. Barbosa. 2018. What Makes a Landscape Contemplative? Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 45 (1):7–25.

- Our Lady of the Mississippi Abbey. 2006. The Monastery: Our Lady of the Mississippi Abbey [Video File]. MMVI Discovery Communications, Inc.

- Palmisano, S. 2014. An Innovative Return to Tradition: Catholic Monasticism Redux. In Annual Review of the Sociology of Religion Volume 5: Sociology and Monasticism, Between Innovation and Tradition, edited by I. Jonveaux, S. Palmisano and E. Pace, 87–106. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Pennington, M. B. 1995. The Cistercians. In The Modern Catholic Encyclopedia, edited by M. Glazier, 178–179. Collegeville, Minn.: Liturgical Press.

- Pearson, P. M. 2016. From Clairvaux to Mount Olivet: Thomas Merton's Geography of Place. The Merton Annual 29:58–71.

- Perkins, W. R. 1892. The Trappist Abbey of New Melleray in Dubuque County, Iowa. Iowa City: State University of Iowa.

- Raab, J. Q. 2016. Introduction: Thin Places and Thick Descriptions. The Merton Annual 29:7–14.

- Relph, E. 2017. The Openness of Places. In Place and Phenomenology, edited by J. Donohoe, 3–15. New York: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Sbardella, F. 2014. Ethnography of Cloistered Life: Field Work in to Silence. In Annual Review of the Sociology of Religion Volume 5: Sociology and Monasticism, Between Innovation and Tradition, edited by I. Jonveaux, S. Palmisano and E. Pace, 55–70. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Schuessler, R. 2015. A New Face for an Ozark Monastery. Al Jazeera America. [http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2015/1/3/a-new-face-for-anozarksmonastery.html]. 3 January.

- Sopher, D. E. 1967. Geography of Religions. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall.

- Thomas, C. 1907. Cahokia or Monk's Mound. American Anthropologist 9:362–365.

- Tvedten, B. 2013. How to Be a Monastic and Not Leave Your Day Job. Brewster, Mass.: Paraclete Press.

- Ward, B. 1972. Contemplation and Community: An Anglican Perspective. In Contemplative Community: An Interdisciplinary Symposium, edited by M. B. Pennington, 185–193. Washington, D.C.: Cistercian Publications Consortium Press.