Abstract

Postsecular geographies seek to examine how place is linked with identity and how religious identities in turn can be accommodated in public space. Postsecular practices in urban contexts have been researched extensively, but they do not always fully engage with a relational approach to place‐making. This paper argues that through the place‐making practices seen at Virgin Mary statues in Dublin city, Ireland, a relational approach to examining postsecular practices and representations provides a more productive way to understand how the secular and the religious coexist in cities. The paper uses archival and contemporary data gathered from a sample of Marian statues in Dublin city to locate the relational geographies of the religious and the secular. By focussing on the ways that the statues remain uncontested within a changing urban landscape, the paper re‐examines the political significance of religious place‐making practices. It concludes that if geographies of religion in the postsecular city are to have a broader relevance to geography, they need a relational approach to place‐making.

Standing in the middle of the Dublin city's principal street are four male figures, representing various political events in the city. Over the last three decades, other figures have been added across the city: musicians, poets, and revolutionaries. Another set of statues is also prominent: statues of the Virgin Mary. There are more statues of Mary in Dublin, the city of James Joyce and Brendan Behan, than any other figure. How did these statues become a part of Dublin's urban landscape? Under what conditions do they persist? What does their location reveal about the relationship between the religion and public space? Ostensibly the site of Catholic veneration, the statues have taken on a different meaning in the context of ongoing urban change. To enhance understandings of the postsecular city, this paper argues that the statues’ persistence point to ongoing political contestations over how the modern city is made and remade over time. It is an attempt to move postsecular approaches, itself an ambiguous term, in urban contexts away from a binary between “once religious, but now secular” and toward recognising the inherent political content of the religious in place from the start (Beckford Citation2012).

Much current research conducted in the geographies of religion has been concerned with the location of religious practices in urban contexts (Stevenson and others Citation2010; Dwyer Citation2016; Lynch Citation2016). The postsecular approach has been put forward to understand how the multiply construed identities of urban life interact with the places of the religious and the secular. This approach tries to understand the relationship between place‐making practices and religious identities emerging among the secular spaces of the city (Beaumont and Baker Citation2011, 1–14; Cloke and Beaumont Citation2012). The approach acknowledges the indeterminacy of religious place‐making practices and a theoretical opacity for the public sphere (Staeheli and Mitchell Citation2007; Staeheli and others Citation2009). Most recently, Banu Gökarıksel and Anna Secor (Citation2015) have shown how the secular and the religious in urban settings are, in fact, mutually constituted. I do not wholly endorse the postsecular approach but seek to make it more robust by arguing that current usages of a postsecular approach, understood as a deconstruction of the secular/sacred binary seen in the re‐emergence of religion in cities, is insufficient.

Drawing on Doreen Massey's (Citation2005) deconstruction of the space/place dichotomy and Pierce and others’ (Citation2010) work on relational place‐frames, this paper argues that understandings of postsecular urban space are often shorn of their broader political significance. Postsecular accounts of urban space have rarely, to this point, been able to sufficiently account for ongoing attachments to religious commitment that derive their political power from contestations on other scales. In short, the politics of the postsecular city needs to be acknowledged from the start of any analysis.

I use the example of the Marian statues of Dublin city to show how contested urban space is used for religious place‐making. Such contestations are of political significance, worthy of our attention as geographers. While the postsecular is a useful way of seeing the persistence of the religious in urban settings, thinking about the religious and the secular as existing in relation to each other means paying attention to continuing political contestations as place‐frames. In this way, I point to a deficiency in the postsecular approach. The statues of the Virgin Mary in Dublin provide evidence of a relational geography that can help us to understand dynamic political contestation in urban settings. In this context, the place‐frame is continuity of religious experiences. In the next section I outline the social and political context of the Marian statues in Irish urban landscape.

The first part of the paper examines the literature on the postsecular city and an understanding of place‐frames. It provides a theoretical basis for my own empirical work and analysis. In the second part, I demonstrate how the Marian statues of Dublin city prompt a relational place‐frames approach. I outline how the religious practices they prompt continue to be part of the spatial politics of the city, particularly in working‐class neighborhoods. Catholic adherence remains relatively strong in Ireland, particularly in a European context. While religious service attendance is declining, particularly among younger cohorts, between one in three and one in four people in Ireland attend weekly religious services, Christian and non‐Christian. The contestations present at Dublin's Marian statues show that current postsecular understandings of the relationship between place and religious identity in the city do not fully engage with how this identity is suffused with political meaning. The final part argues that by noting the places and spaces where these contestations occur, we can understand the political quality of everyday religious practice. As has been noted by Justin Tse, secular place‐making practices are co‐constituted with transcendent practices (2014).

Marian statues take a prominent place in many Irish housing developments built between 1940 and 1970, often occupying the neighborhood's entrance from the main road. They were meant as objects of veneration to Mary, the mother of Jesus, a central figure for all Catholics and in her role as intercessor with God. Additionally, the statues provide a focus for community rosary gatherings and the local presidium of the Legion of Mary. They act as a visual reminder that the domestic space is as important as the Mass, held daily in the local parish church. The statues’ continuity in housing neighborhoods across Dublin belies a notion that religion is reappearing in public, an underlying assumption of the postsecular city argument. The place‐frame of continuity is evident from the statues’ persistence in a variety of changing urban settings. The argument concludes by noting that contestations over what makes space secular and religious in urban settings means being attuned to and noting a direct political intent for religious identities forged in these places.

The Marian Statues of Dublin city in Context

With significant social and cultural change in recent decades, Dublin city provides a useful case study to understand the relational place‐frame of continuity of religious identity. Some context can demonstrate that the statues are not artefacts of a religious past, but part of the ongoing contestation over the urban in Ireland. Dublin city has seen significant change in its urban form in the last two decades, with the development of new docklands sites hosting mobile multinational capital and a massive speculative housing boom from 2001 to 2008 (O'Callaghan and others Citation2015). Socially, a number of features of Ireland's development point to unresolved fractures within the urban landscape. Large‐scale survey data confirm that fewer people in Ireland now attend Catholic rites and rituals when compared with the 1980s (O'Mahony Citation2010). The numbers of people declaring no religion in the census in the last two decades increased threefold (Horner Citation2004; Andersen Citation2010; CSO Citation2012; Donnelly Citation2015), a pattern confirmed by more recent census data. These changes are partly due to processes of transnational migration (Bushin and White Citation2010; Maher and Cawley Citation2016). To the present time, Irish social life is infused by a set of practices and performances originating in Catholicism. How can we account for this?

From the eighteenth century, following colonial prohibition, Catholic religious practice was reterritorialised by the Roman Catholic Church within parishes (Duffy Citation2007, 63). Since the 1870s, the Catholic Church developed a strong power base in parishes while also securing a significant cultural presence across Ireland (Whelan Citation1983; Daly Citation1984; O Broin and Kirby Citation2009). For example, the largest sporting organization in the country, the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) is organized into 2,300 clubs on a Catholic parish basis (O'Connor Citation2011). Beyond territory, the publicly funded national broadcaster plays the Catholic Angelus twice daily on television and radio. To the present day, journalists seek the views of Catholic bishops on matters of reproductive rights and family policy as part of a journalistic habitus receptive to Catholicism (Donnelly Citation2015). Finally, Catholic religious orders influence the political, educational, and medical contexts within Ireland, arguably best described as a precariously secular state (Inglis Citation1998; Agrama Citation2010).

These contexts are infused with class distinctions, where religious orders (or their trustees) structure and have ownership over the country's elite educational institutions and private medical care is entrusted to these orders. As recent government reports have shown, the newly independent state's incarcerating institutions have had defined class outcomes, with working class women and girls suffering disproportionately (for example, the Department of Justice and Equality Citation2013). The bodies of working class women and girls were subject to particular forms of abuse in these carceral systems (Crowley and Kitchin Citation2008). Seen in this way, the placement of Marian statuary during the twentieth century was a form of neighborhood reinstatement of female chastity promulgated from the church altar.

Geographers’ representations of religion in Ireland have been confined to cartographic evidence of the distribution of various populations (Gillmor Citation2006; Cunningham and Gregory Citation2012). Some attempts have been made to examine the changing religious composition through ethnicity (see Ugba Citation2008). Outside a small number of studies however, geographers’ representations of religious places in Ireland do not often connect local practices with networks of power in other contexts (an exception being White and Gilmartin Citation2008). In the following section, I examine the theoretical underpinnings of my critique of the postsecular approach.

Religion, Place, and Identity

Much of the recent work in the geography of religion has examined the relationship between religion, place, and identity. This has been undertaken to understand both the changing demographics within large cities and the mobilities that have arisen from globalisation processes over the last century (Beckford, Citation2012, 14). An understanding of urban space as postsecular has been offered as a way to examine this relationship. It outlines how relational place‐frames allow geographers to reveal the political contestations in religious places. Place‐frames arise when people orient social and political action during the dynamic production of places through everyday life (Pierce and others, 2011, 59). This is important because some forms of religious practice are more politically contestable, in European space for example, than others. The planning of a new mosque in Ireland attracts more political attention than disturbances caused by annual Christian pilgrimages. In this way, the continuity of the Marian statues in Dublin indicates a political meaning for religious practice. To examine this place‐frame of continuity, we need a theoretical framework that allows the political meaning of the statues to be present from the start, one that requires us to look again at how place and identity are related. By explaining how emplaced actors negotiate the open‐ended trajectories of everyday social action, Massey is an ideal starting point (Citation2005). The open‐endedness of places allows for a fluidity in the way place is (re)created. What Massey calls the “chance of space” (Citation2005, 111) is a way to escape the structuralist calculus of lived reality and representations of the places that we inhabit. The chance of space is the contingent everyday process of making and remaking our world. Negotiation for place is thus always possible. Crucial to Massey's formulation is the taming of space: where the histories and representations of Others are held still while the people of modern societies become increasingly so. In these terms, she states, the religious is deprived of a history that informs its present (Citation2005, 121‐122).

However, as social and cultural geographers, we still need an understanding of how place is sedimented and routinely altered at the same time. What work has been done to examine trajectories uses Massey's conceptualisation of throwntogetherness, the contingency amongst the seeming solidity of place. For Massey, space is a topographical surface that time renders as culturally and politically uneven (Citation2005). Trajectories (that is, when the specifics of place are layered into place bundles) are locally authored, but are in turn altered by other authorizations found elsewhere. The politics of local authorization gives rise to a contingency that is often difficult for geographers to represent. Jeff Baldwin's work with Antiguan resort workers recognizes “that in order to identify, to see, and then understand such relationships [between actors and trajectories], a certain openness…is helpful. But we are not told how to perform that” (Citation2012, 209). A challenge for geographers of religion in particular is the encounter with, and the adequate representation of, the messiness of religious place‐making practices.

Such a task is made more difficult by an unhelpful division between public and private space: held to be self‐evident categories rather than outcomes of contested and ongoing place‐making practices. Both religious and secular subjects encounter and reauthorize trajectories, irrespective of their current emplacement. Massey's open‐ended quality of space assists in the further decomposition of this unhelpful public/private binary employed in many geographic accounts of religious identities in urban settings. Religious identities in cities are better thought of as unresolved—never completely knowable by a single process called secularization. More productive ways of understanding religion within cities (once assumed to be religious spaces, now secular) are possible. Recent work on postsecular public spaces has provided a way forward.

Work on postsecular urban space has encouraged further explanations of interreligious dialogue, and a tolerance between positions of former incompatibility (Knott Citation2010; Holloway Citation2013). It has allowed geographers to begin to disentangle the public/private binary (Gökarıksel and Secor Citation2015, 28). Its usage is not meant to denote a specific time frame within which the secular has ended, followed inevitably by postsecular place‐making practices (Bondi Citation2013). The postsecular is not meant here as a progression, or a stage beyond, the secular. Instead the postsecular city is a set of hybridized moments, places, and practices that draw from both immanent and spiritual commitments. For some, understanding postsecular practices means the adoption of a reflexive position against secularity rather than a rejection of the concept itself (Lee Citation2015, 45–46). Others have characterised the postsecular as a recognition of the limits of secularism's understanding of freedom and rationality (Holloway Citation2013). In Gökarıksel and Secor's research, the sanctioning of Sunni women for headscarf use in urban Turkey points to the fact that religious faith is knitted into both anonymous and intimate spaces at the same time. From my own research, the Marian statues represent a public piety embodied in particular sites that refer back to the role that Mary plays as an intercessor for Catholics in their own prayer. For a postsecular analysis of the urban experience, a problem remains: it discounts the multiple ways that place and identity are formed and re‐formed in combination. The postsecular city, as characterized, conceives of the religious devotee through a lens of greater individual freedom. Crucially, examinations of postsecular cities do not connect the significance of local practices with networks of power found elsewhere. They frequently misrecognize what is understood as religion in public life in the first instance (Beckford Citation2012, 17). In support of Lily Kong (Citation2010), the concept of the postsecular does “present a new and exciting conceptual apparatus in order to understand cities” (Beaumont and Baker Citation2011, 4) but that is often disconnected from networks of power found elsewhere.

If the postsecular is to be as energizing a concept as Gökarıksel and Secor wish, it needs further work to undermine the division between private and religious space and public and secular space, still prevalent in public discourse. The myriad interactions and places through which all social action, including that found at and around the Marian statuary of Dublin, is grounded as political need more work. They acknowledge that the abstract spaces of the media or being religious in public are not enough to incorporate the experience of Sunni women in Istanbul. However, as geographers we need to do that work knowing that everyday religious practices are more than local iterations of large scale processes found elsewhere. Place matters in identity formation, and this is reflected back to the devotee as contestable urban space, drawing from significances located elsewhere and sometimes even from pasts no longer material in these places. The Marian statues in Dublin city are imbued with a political significance that does not require us to define them as religion. Furthermore, the religious is not a foil for the secular, to be invoked merely to naturalise the secular (Gökarıksel Citation2009).

Locating postsecular spaces and practices relies on a visibility in public, a term with significant ambiguity (Staeheli and Mitchell Citation2007). When this public is understood as a series of conflicts over ownership, the state remains the arbiter of deciding what is religious and what is not (Staeheli and others Citation2009). Gökarıksel and Secor have already identified a need to understand postsecular urban space in places other than the state. Working across scales, they indicate how particular neighborhoods in Istanbul are constitutive of “micro‐geographies of pluralism” (Citation2015, 26). However, they do not redefine what is meant by the political in the same way. This is why the adoption of a relational place‐frame approach is constructive. It means taking political motivations as constitutive of identity in place from the start. It means seeing actors as participating in a series of local interactions that are connected to other places. Such accounts of postsecular urban space are grounded among legalistic state arbitrations over where the public is found and where it is not.

One of the shortcomings of a postsecular approach, then, is its starting point. Public religious practices remain accommodations made within secular polities (Asad Citation2003; Bondi Citation2013; Bugyis Citation2015). Too much power is given to the supposed neutrality of the state‐arbitrated public sphere. We are left with an under‐theorization of the relationship between place and identity within the geography of religion. As will be seen with the Marian statues of Dublin, neighborhood planning allows for religious identity even when rarely stated as such. What few attempts have been made argue for a relational approach to understanding the spatialities of religion (Brace and others Citation2006; Lee Citation2015). They produce hybridized places, defying determination as once religious but now secular. Place‐making requires us to recognize the constant unfolding of places where the daily practice of religious place‐making is a political expression of place‐identity. Relational place‐frames are used to make those expressions more explicit.

Relational place‐frames are locations in space where contestation over place is inherently political (Pierce and others Citation2010). The frames are not always recognized as formally political but nor are they made less so by being connected with local forms of political contestation. Pierce and others ask that we:

Focus analytical attention on the place/bundles drawn on by actors in the place‐framing process in order to identify points of contention and commonality in the elements of the place/bundles experienced by actors on opposing sides of a conflict.

This attention allows for an open‐ended contestation over place/bundles, of the place‐frames deployed in the conflict, and the broader strategic aims of those engaged. Pierce and others argue that to understand relational place‐frames, we should pay attention to the way actors participate in overlapping and contradictory networks “as well as those actors who remain invisible in power‐laden disputes” (Citation2010, 66). They affirm, like Catherine Brace and others, that all places are relational, and geographers must seek the interconnections between place, identity, and politics (2006). We need to reveal the conflicts produced by places (Pierce and others Citation2010, 67). In their work, and done here too, Pierce and others seek to operationalize the hybridized unfolding of place by outlining the places where the particular takes precedence and how it is related with networks elsewhere. This helps us to escape the theoretical and analytical restrictions of a religious/secular binary mapped too neatly on to a division between private and public space.

Moving away from the perspective that the particular is only a window into the general has proven as difficult to operationalize as it was to theorize a decade ago (Cidell Citation2006; Collinge Citation2006; Moore Citation2008). Pierce and others argue that “relational place becomes ‘exposed’ for investigation and scholarship as it is made and remade, or via contestations” (2010, 61). When a place's meaning changes, the relational place‐frames involved are made clearer and, in particular, more available to a postsecular analysis. Employing a relational place‐frames approach means that “rediscovering” religious practices in urban settings like Dublin is unnecessary work; it was rarely privatised in the first instance. As I show, the practices at Marian sites in Dublin never disappeared in the first place. They remain in many places, tended to and decorated monthly and more often. They are sites of ongoing venerative practice. To advance the relational place‐frames approach, I argue that new contestations over the statues’ sites and changing uses for the surrounding land reveal how the religious and the secular are emplaced together.

Methodology

The research used a combination of qualitative methods with a focus on photographic methods and historical archival work to build up a picture of the statues’ origins and current context. In this way, the research conforms to a broad but recent tradition of attending to the ways in which visual culture can be used to answer research questions (Rose Citation2007, 4–6). While I could not claim that the act of photographing these statues was a neutral act, visual methodologies used in the social sciences draw attention to the site of the image as well as the site of production. For this project, where the photography formed a significant part of the data‐collection method, the purpose was not to understand how people use these sites through photographing them, but to record their positioning within broader contexts. They are illustrative of their position within specific neighborhoods of the city. This is in keeping with an approach to humanistic geography where methods like nonparticipant observation have been supplemented with an interpretation of texts, images, and related cultural practices to reflect on the place of the researcher (Rodaway Citation2015, 336).

I investigated the sites of twenty‐eight Marian statues in residential neighborhoods of the Dublin metropolitan area. These sites represent about two‐thirds of the known statues of Mary in the Dublin region. I located the statues across the city through word of mouth and documentary sources, visiting each site twice. The statues and sites were photographed twice: the first time was using a smartphone camera collecting XY coordinates so that the sites could be placed more accurately on a map of the city. The second visit was with a digital single‐lens reflex camera. I took three hundred pictures across all of the sites within the study. At a small number of the sites, where it could be arranged, I conducted a small number of unstructured interviews to gather supporting data, acting as a brief oral history of the site. This only occurred once at Fatima Mansions/Reuben Street and went, at that site, unrecorded. At some others, conversations with people were prompted by my photography. Written notes on these conversations and the unstructured interviews were recorded after the fact. The statue at each site was also examined for the type of material used, its decoration, and the placement within the site as a whole. In general, and when it was possible to engage people in conversation, people do not speak directly about these statues.

These statues however, as characterised recently by Rose are not stable cultural objects, yielding their meaning only when produced through digital imagery (2016). Following the site visits, I conducted a search of the Irish Newspaper Archive to gather some additional historical evidence. This archive holds many of the smaller newspapers archives of the time as well as two nationally published newspapers, the Irish Press and Irish Independent. The terms “Marian statue,” “Our Lady,” and the names of known sites drove the search process. It involved searching within the timeframe 1952 to 1955, to cover the Marian Year celebrations of 1954 and adding the names of specific neighborhoods (1952 to the present day) where the statues are currently found. In all, a total of twenty‐five newspaper articles in the time period 1952 to 2015 were found using the search criteria. This archival work was an attempt, however limited, to recuperate some of their meaning as they were placed within the urban landscape at the time. The articles were used to gather additional historical detail that may have given insight into the site and the context within which the statues were installed in the first instance. Very often, newspapers were the sole record of the statues’ origins and opening ceremonies still extant.

The Statues as Uncontested Sites

The locations of the Marian statues in Dublin city are related to developments in the provision of public housing throughout the twentieth century. While Dublin's municipalities had been incorporating surrounding villages since the 1850s, public housing was built in much great numbers after 1930 (McManus Citation2002). The move from small‐scale model projects of the pre‐independence period to massed suburban development up to 1970 reflects the concerns of the new state (Kincaid Citation2006, 66‐77) ensuring adequate housing for working‐class people migrating to the cities. What is distinctive about the post‐1930 suburban housing schemes was their large green areas. The public housing schemes of the neighborhoods of Cabra and Crumlin, for example, involved low‐density development accompanied by large green spaces, some of which accommodate Marian statues. Very often, the institutional Catholic Church was involved at planning the early stages of these developments (Rowley, 2016). Land‐use decisions like these are a part of the nexus of politics, social class, and the emplaced identities of Dublin residents.

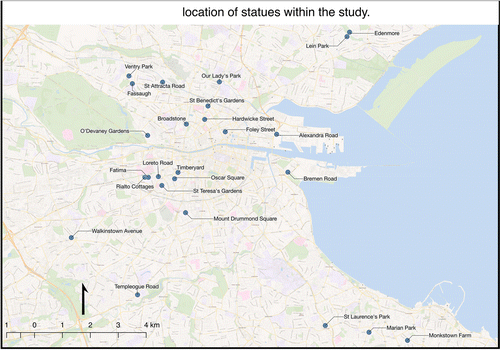

The map below (Figure 1) shows the location of the Marian statues of the Dublin area within the study. Their distribution across the city represents the story of the growth of (sub)urban Dublin through the second half of the twentieth century. As housing developments were completed, statues were funded and erected across the city (see Irish Independent Citation1955a). The sampled statues are in three parts of the city:

The Liberties, in the city's south west (eight statues)

Dublin's inner suburbs (thirteen statues)

Dublin's outer suburbs (seven statues)

The Liberties area lay outside the medieval city walls until their redundancy after the mid‐eighteenth century. In the remaking of the city after the establishment of the Wide Streets Commission in the 1750s, the Liberties remained a district composed of dense working‐class residential and commercial buildings. The other two parts of the city where the statues are found, largely completed by the 1970s, have larger green spaces than the Liberties. Of the twenty‐eight statues, the majority are located within residential areas, although a small number are near or within the bounds of workplaces. Their persistence represents a sense of Catholic piety in public space, providing an opportunity to many to ritually bless themselves. They are a representation of the hegemony of the Catholic Church across many aspects of Irish public life.

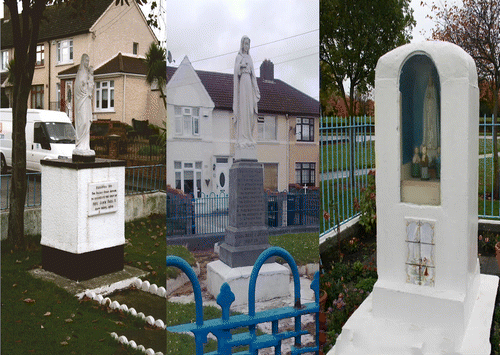

At a majority of the sites studied, the statue is surrounded by green space and low railings, although some are contained within an enclosed corner space. The unenclosed statues tend to be made of concrete, while encased ones being cast in plaster. Figure 2 indicates the forms that these statues take in three different locations across the city.

Railings indicate a space apart, neither entirely residential nor recreational space. The celebration of the Marian Year of 1954 accounts for the placement of some of the statues (Irish Independent Citation1955b, Citation1956). The statues are generally placed on a plinth about two meters in height; some are taller than that. At most of the sites, the figure of Mary stands on an orb, a crescent moon, and serpent, a reference to overcoming sin. If painted, the statues are blue and white, reflecting Mary's association with water (Foley Citation2010, 72–73). The statues are cast posed in one of two ways: hands opened in invitation or clasped in prayer. This form echoes the statues found within churches from the post‐Famine period onward (Lawless Citation2010). Unlike those within churches, Marian statues on open ground have an inscribed proclamation of Mary's status as, for example, the Immaculate Conception. This public declaration of Mary's status confirms the statues’ role in reinforcing religious devotion in residential space. In the case of the statue at Drumcondra, it is on a site formerly containing derelict houses. At its unveiling in May 1955, it was noted that the statue replaced an older one amongst the houses (Irish Independent Citation1955b).

The statues are unimposing focal points on green space where children can play soccer nearby. In keeping with other research, religious practices are often made corporeal where the body is a medium of faith and not a vessel into which faith is poured (Gökarıksel Citation2009, 660–662). Their presence on open green space where generations of children grew up makes every day that which might otherwise be deemed devotional (Figure 3). Any distinction made between sacred space and secular suburbia is thus blurred.

The following three examples from the twenty‐eight surveyed statues show how the use of urban land for statues remains uncontested until the present day. These three examples show how place, identity and religion are related and how they are maintained in the face of larger scale urban change. The prominence of the statues may have changed but they remain open to ongoing political contestation over what is religious and secular. Their place‐frame is continuity within residential and workplace settings. The statues’ persistence on green space on housing developments and at some workplaces are not a part of the contestation over the role of the Catholic Church in public life, particularly following revelations of institutional abuse. These examples serve to demonstrate their place‐frame of continuity.

Fatima Mansion Reuben Street

Fatima Mansions, a public housing complex about 2 km south west of Dublin city center, was a site of significant public investment in the late 1990s to early 2000s. Originally built in the 1950s, the fourteen four‐storey blocks of apartments became a site of multiple deprivation throughout the 1980s. In the mid‐1990s, the combined residents groups leveraged local and national political power to bring about a regeneration of the complex. Fifty‐seven percent of the 6,200 people who live in the neighborhood (2 electoral divisions) declare themselves to be Catholic, compared to 78 percent nationally (Central Statistics Office Citation2017). The area has a relatively young age profile, with about half the old dependency ratio (proportion of over 65s to the remaining population) of the city as a whole. Between 15 and 20 percent of the housing stock in this area was built after 2006, reflecting the large regeneration project that occurred before this time. Between 60 and 70 percent of this stock is rented either from the local authority or privately, compared with 44 percent for the city as a whole.

The original Marian statue at Fatima Mansions (now redesignated Reuben Street) was a glass‐encased Our Lady of Fatima. Early in the regeneration project, the statue was removed from its place against a high wall that separated the public housing from the rest of the neighborhood. Deirdre, a community worker based within the area indicated that, even during years when heroin abuse was a significant social problem, the statue was never vandalized. A new statue was purchased in 2011 in advance of the completed housing program. The photo below shows this statue in storage before its repositioning.

Following the regeneration program's completion, Fatima Groups United (the combined residents’ representative body) replaced the broken statue with a new one and within a Zen Garden, containing among other things, a geodesic dome for vegetable production. When asked about the replacement statue, Deirdre replied that it is “our statue, not the [Catholic] church's”.

The place of the statue at Fatima Mansions / Reuben Street did not go unchallenged in the regeneration program. Arising from the community capacity‐building process central to this program, the returning residents insisted on the statue being replaced. However, it was replaced within the site as a community resource, not a sign of Catholic devotion. Crucially, while still connected with Marian devotion at other sites, the residents of what was once Fatima Mansions have replaced the statue and insisting that it belongs to them and not to the institutional church (Figure 4). The ownership and meanings of the statue passed from the institutional Church to a newly constituted public over the course of the regeneration process. The statue's meaning remained open to change, never wholly a secular object, but signifying a continuity among the older residents.

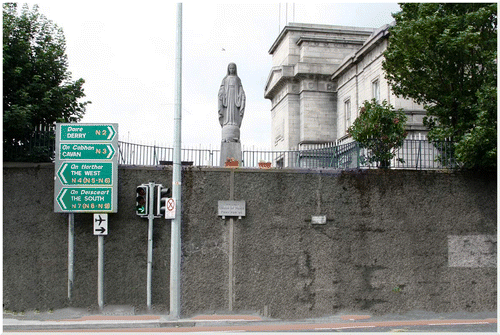

Broadstone Bus Garage

This Marian statue is on the grounds of repurposed railway station closed in the 1930s, above a national primary road running northwest out of Dublin (Figure 5). It is now a bus depot with little current public usage but being reintegrated into public space as part of a cross‐city tram project. The three‐meter tall concrete statue was paid for by the employees of the state transport company CIÉ and later opened in a grand ceremony (Irish Press Citation1952). Two other city bus garages owned by Dublin Bus (Ringsend and Conyngham Road) and a CIÉ carriage workshop also have Marian statues. In all four cases, the railway and bus garages are located in working class neighborhoods and subject to high levels of emigration in the 1950s. In that decade, these neighborhoods experienced declines in the numbers of residents. South Dock saw a 27 percent decline in population in the five years between 1951 and 1956 and Phoenix Park a decline of over 10 percent (Central Statistics Office Citation1957). It is clear from newspaper reports that CIÉ workers were prominent in Marian devotion at this time (Irish Independent Citation1954).

Three men (not bus company workers) were present on the morning in 2011 I went to photograph the statue. After a brief conversation, one of the men took out a Marian medal dangling around his neck and said that “she protects me.” In 2014, a conservation architect from Dublin City Council, investigating the site in advance of the new tram line's installation wished to know the ownership of the statue at the Broadstone site. She had had “a query regarding the above statue. The caller thought maybe [the City Council] owned the statue” and stated that there “are no plans to remove it permanently but of course that could change” (personal communication 2014). The statue stands, to this day, entirely within the bounds of the publicly owned bus company. This continuity is founded on the basis that the statue does not represent a challenge to the changing land use for transportation.

In 2016, the tram construction project management company confirmed that the statue will remain, arising from representations made by some bus company employees. In late 2017, I spoke with a man painting the surrounding railings in preparation for the Feast of the Immaculate Conception. Seeing my Repeal (of the 8th amendment to the Irish constitution which prohibits abortion) lapel badge, he told me that “your crowd” should leave the statue alone, a reference to an occurrence a year earlier where a Repeal sign was placed around the statue's neck. The altered land use at Broadstone is compatible with the statue remaining in place. Little division exists between religious and secular place‐frames here, let alone public and private space. The place‐frame that is evident is one of continuity.

The Timberyard

The Timberyard building is located in the center of the Liberties district in the south inner city. This area has a higher than city average percentages of people renting privately and from the local authority (77 percent of the area's residents; 44 percent being the average) but an older person dependency ratio that is half that of the city average (Central Statistics Office Citation2012). While 3 percent of the city's residents are classed as unskilled, 7 percent of this area's residents is. In 2009, a new apartment building replaced a long‐derelict site, on which a Marian grotto already stood. During the planning process, written objections made by the Coombe Residents Association included one that stated “the space were [sic] our statue exists will be lost and were [sic] a seeking a commitment from the City Council that they will compromise on this by providing a new play facility for the children of the Coombe in an alternative location” (Coombe Residents Association Citation2005). With the loss of the grotto space, the residents sought a playground for the children of the area instead.

In an unstructured interview I conducted with the project's chief architect, she spoke of residents’ concerns and about how pedestrian access to the adjacent Cork Street were overcome with the placement of the statue at the corner of the site. She stated it is not a religious site but is “out in the community” in fulfilment of the role of architecture as more than just functional. On nearing completion she was asked to create a recess with the kneeling step for the statue. According to her, the building of a kneeling step at the statue's recess “just happened.” In lieu of the requested children's play area, the statue was placed into this recess (Figure 6).

At the Timberyard site, the re‐placement of the statue of Mary shows the political process whereby residents’ objections could be alleviated. Objections about access to Cork Street were resolved by the placement of the statue at the apex of the building. Forty‐three percent of the area's population is Catholic and 28 percent state no religion (CSO Citation2017). We might expect to see more objection to the inclusion of a religious statue within the new building. However, as with the Broadstone statue, it is an acceptable use of the land to replace the Marian statue without ever questioning this as a reassertion of Catholic religious place‐making practices. Its placement as an element of continuity within the scheme helped resolve the conflict over access from the main road and the lack of children's play area.

The above three examples provide evidence that the statues of the Virgin Mary remain uncontested within changing uses for the land in each case. The place‐frame referred to each case is the continuity of the statue. In a city undergoing material and social change, there is little to suggest that the statues are part of the contestation over secular and religious space. Across other examples from within the twenty‐eight sites, the statues remain in place with significant alteration to the surrounding city and suburban landscapes. In Ballyfermot, a western suburb, the main roundabout was redesigned and the Marian statue was re‐placed and redecorated. In the city center, the Foley street neighborhood was redeveloped with private and public housing, but the enclosed statue remains in place. In the south suburbs at Monkstown, in the midst of a changing village redevelopment, the elaborate Marian statue remains adorned and attracted monthly devotions at the time of the fieldwork. In Drumcondra, the site of the Marian statue was renamed Marian Park by the City Council in 2014. That these statues remain uncontested across the city while the landscape around them changes shows how a place‐frame of continuity exists. In the next section, I explore the political outcomes of this place‐frames approach.

The Politics of Religious Places

The examples of Marian statues above show how no clear distinction can be drawn in Dublin's changing urban landscape between private religious practices and a secular public space. The sites of the statues are uncontested within any understanding of a secular and changing city. The Council keeps a database of all public art installations, but none of the Marian statues surveyed for the research is listed in this database.

Within a context of significant urban change, the locations and uses of the statues have not changed in recent years. In some cases, statues have been re‐placed within new developments on or near older statuary sites. This prompts a broader reassessment of how, as geographers, we often map an unproductive secular/religious binary on to a division between private and public space. Such a mapping inhibits an adequate analysis of the changing practices and performances of the religious in the ongoing mutual constitution of identity and place. Understanding religious place‐making by persisting with a division between a secular public realm and the private lives of people is made redundant using a place‐frames approach as outlined by Pierce and others (Citation2010).

Alongside the broader changes across the last two decades, the statues are bundled with processes and practices found on multiple scales elsewhere. Like many cities in the early part of the twenty‐first century, groundings of multinational capital formed a significant part of Dublin's economic growth during the 2000s. Specific forms of urban development dominated the period 2002 to 2008, most notably private apartment building in the city center. The material evidence for these groundings is found in the redevelopment of the city's docklands as well as housing regeneration programs like Fatima Mansions (Moore Citation2008; Brudell and Attuyer 2014; Byrne Citation2016). This implies a number of points. Firstly, a focus on contested and continuing place‐frames allows for a critical reassessment of analyses that focus on a clear distinction between one form of space and another. The continuity place‐frame of the statues draws from both secular and religious struggles, co‐constituted but not neatly mapped onto both public and private space. Furthermore, a relational place‐frames approach means we take the political contestations of actors and networks at these statue sites seriously. This is why the statues’ placement in largely working‐class neighborhoods matter: the institutional Church supported parishes’ fund‐raising activities for them, but did so on the basis that it reflected a politics within the domestic space (Inglis Citation1998). All else may have changed in these public housing complexes, but the Marian statue provided a solid focus for community activity across a long span of time. After the replacement of the Fatima Mansions statue, the place‐making occurred as part of the neighborhood regeneration. The Council played a significant role in the regeneration alongside community groups and a number of private investors. After regeneration, residents re‐placed the statue as part of a multifaith Zen garden. The replacement of the statue at the Timberyard formed the center of a struggle over community gain. We can see then, following Pierce and others that all places are relational and produced through a networked politics:

[A] relational approach to place‐making provides insights into how to analytically unpack competing place‐frames in order to identify key points of discontinuity, contestation and fluidity.

The Marian statues call attention to a political significance for the religious and identities claimed in a context of significant change in the urban landscape. Dublin city needs housing, transport infrastructure, and new green spaces, but the statues remain compatible with this vision for the city. There is no contestation between the entrepreneurial ambitions of the Council and persistence of the statues. Geographers should begin with the contestations and continuities that arise, an approach that does not rely on sets of pre‐formed and dominant categories. A dismissal of the statues as remnants of a “religious past” dismisses the political significance in these places.

Secondly, the maintenance practices at these statue sites are not inherently local and the place‐frame of continuity they prompt are much wider than Dublin city. They are connected, through other networks, to Marian veneration elsewhere (Tweed Citation1999; Orsi Citation2010). Marian statuary in Dublin city is related to sites and practices found elsewhere in Europe, a transnational network of veneration. For example, the statue at Broadstone was dedicated as Queen of Peace in 1952 with the emergence of nuclear peril as a geopolitical concern. The statues are more than a representation of some authenticity of local religious practices, exceptional to Dublin. Their continuity in place rejects a spatial imaginary of the religious as now past (Massey Citation2005). If we begin with the site and its contestations, we can seek the multiple ways that religious identities are formed and re‐formed in place.

Finally, the Marian statues are significant because the political meaning of their continuity is more than local. Examining these statues using a relational place‐frames approach gives them a greater political power than them being examined solely as an exemplar for abstractions such as ‘the religious.’ Peoples’ continued use and maintenance of the statues, and the continuities formed in their persistence, are connected from the start with other places. These places are never resolved as secular or religious because the politics of these places and the identities formed there remain open to contestation. Conflict over what is an appropriate use for this part of the city originate in trajectories elsewhere. The geographical study of religious and secular place‐making is thus made richer and more amenable to geography as a whole when understood as part of a relational place‐frames approach (Kong Citation2010). It means revisiting the central aims of Massey's work on the throwntogetherness of place and the adoption of a framework open to the contingency of how place is made (Citation2005).

Conclusion

Understanding the geographies of religion as relational place‐frames avoids unhelpful binaries: the private and religious spaces, practices, and representations on the one hand and public and secular ones on the other. Geographers and others have gone a little way to unpacking some of these binaries. Using the Marian statues of Dublin city as an example, I show how a place‐frame of continuity is evident. This place‐frame approach exposes the ways in which the secular and religious coexist in urban settings. Our understandings of the postsecular city need a way in which to analyse how local practices connect more significantly with geopolitical events on other scales, not just as an exemplar of local peculiarity. I believe that Pierce and his colleagues’ work on relational place‐frames and Massey's work on the incoherence of place across time can aid us in this work. In questioning what is meant by the postsecular city, Gökarıksel and Secor's approach is appealing. It ensures that the complexity of place‐making practices and the identities that they form are identifiable in urban settings. They do not bridge the gap between everyday practices and struggles on other scales. The uses of state‐owned land for Marian statuary in Dublin shows how contestations identified by Gökarıksel and Secor in a “restlessly mobile public sphere” are connected to other places (2015, 28).

In this paper, I am arguing that religious practices are not laid down merely to act as a foil to enhance secular place‐making practices. While the secular and the religious are mutually constituted, religious place‐making practices are not uniformly replaced by an inevitable secularity of public space. A restlessly mobile public sphere implies both contingency and continuity in both public and private spaces. It includes religious practices and changing religious identities but is often conceived as contingent upon, even contrary to, the imperatives of that which demands rational argument. Such rational argument is thought of as a prerequisite for a stable public sphere. The people who maintain the statues draw from a political power that changes in other places but maintains a continuity at these sites. The Marian statues remain uncontested within residential and other settings because their persistence does not destabilise other political struggles about the institutional Church's role in state politics or the city's efforts at making Dublin more amenable to global capital. The statues are neither contested by the municipal authority nor in opposition to their vision of urbanism. Some are working on this idea of the mutual constitution of local and regional practices (van Kempen and Wissink Citation2014; Pile and others Citation2016). The currency of the geographies of the religious geography is enhanced if we retain a focus on the political nature of the relational place‐frame.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Eoin O'mahony

Eoin O'Mahony, Teaching Fellow, School of Geography, Newman Building, UCD, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland. [email protected]

References

- Agrama, H. A. 2010. Secularism, Sovereignty, Indeterminacy: Is Egypt a Secular or a Religious State? Comparative Studies in Society and History 52 (3): 495–523.

- Andersen, K. 2010. Irish Secularization and Religious Identities: Evidence of an Emerging New Catholic Habitus. Social Compass 57 (1): 15–39.

- Asad, T. 2003. Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press.

- Baldwin, J. 2012. Putting Massey's Relational Sense of Place to Practice: Labour and the Constitution of Jolly Beach, Antigua. West Indies. Geografiska Annaler: Series B 94 (3): 207–221.

- Beckford, J. 2012. Public Religions and the Postsecular: Critical Reflections. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 51 (1): 1–19.

- Beaumont, J., and C. Baker. 2011. Postsecular Cities: Space, Theories, and Practice. London: Continuum.

- Bondi, L. 2013. Between Christianity and Secularity: Counselling and Psychotherapy Provision in Scotland. Social & Cultural Geography 14 (6): 668–688.

- Brace, A., R. Bailey, and D. C. Harvey. 2006. Religion, Place and Space: A Framework for Investigating Historical Geographies of Religious Identities and Communities. Progress in Human Geography 30 (1): 28–43.

- Brady, J. 2016. Dublin: 1950–1970 Houses, Flats and High Rise. Dublin: Four Courts Press.

- Bugyis, E. 2015. Postsecularism as Colonialism by Other Means. Critical Research on Religion 3 (1): 25–40.

- Bushin, N., and A. White. 2010. Migration Politics in Ireland: Exploring the Impacts on Young People's Geographies. Area 42 (2): 170–180.

- Byrne, M. 2016. Entrepreneurial Urbanism After the Crisis: Ireland's “Bad Bank” and the Redevelopment of Dublin's Docklands. Antipode 48 (4): 899–918.

- Central Statistics Office. 1957. Population, Area and Valuation of Each District Electoral Division and of Each Larger Unit of Area. Dublin: The Stationery Office.

- Central Statistics Office 2012. Population Classified by Area. Dublin: Government of Ireland.

- Central Statistics Office 2017. Religion, Identity and Irish Travellers. Dublin: Government of Ireland.

- Cidell, J. 2006. The Place of Individuals in the Politics of Scale. Area 38 (2): 196–203.

- Cloke, P., and J. Beaumont. 2012. Geographies of Postsecular Rapprochement in the City. Progress in Human Geography 37 (1): 27–51.

- Collinge, C. 2006. Flat Ontology and the Deconstruction of Scale: a Response to Marston, Jones and Woodward. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers NS 31: 244–251.

- Coombe Residents Association. 2005. Planning ref. 3167/05. [http://www.dublincity.ie/main-menu-services-planning/planning-search/].

- Crowley, U., and R. Kitchin. 2008. Producing “Decent Girls”: Governmentality and the Moral Geographies of Sexual Conduct in Ireland (1922–1937). Gender, Place & Culture 15 (4): 355–372.

- Cunningham, N., and I. Gregory. 2012. Religious Change in Twentieth‐Century Ireland: A Spatial History. Irish Geography 45 (3): 209–233.

- Daly, M. 1984. Dublin: the Deposed Capital. A Social and Economic History, 1860–1914. Cork, Ireland: Cork University Press.

- Department of Justice and Equality. 2013. Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee to Establish the Facts of State Involvement with the Magdalen Laundries. Dublin: Department of Justice and Equality.

- Donnelly, S. 2015. Sins of the Father: Unravelling Moral Authority in the Irish Catholic Church. Irish Journal of Sociology 24 (3): 315–339.

- Duffy, P. 2007. Exploring the History and Heritage of Irish Landscapes. Dublin: Four Courts Press.

- Dwyer, C. 2016. Why Does Religion Matter for Cultural Geographers? Social & Cultural Geography 17 (6): 758–762.

- Fatima Community Regeneration Team. 2000. Eleven Acres, Ten Steps. Dublin: FCRT / PCC.

- Foley, R. 2010. Healing Waters: Therapeutic Landscapes in Historic and Contemporary Ireland. Surrey, U.K.: Ashgate.

- Gillmor, D. A. 2006. Changing Religions in the Republic of Ireland, 1991–2002. Irish Geography 39 (2): 111–128.

- Gökarıksel, B., and A. Secor. 2015. Postsecular Geographies and the Problem of Pluralism: Religion and Everyday Life in Istanbul, Turkey. Political Geography 46: 21–30.

- Gökarıksel, B. 2009. Beyond the Officially Sacred: Religion, Secularism, and the Body in the Production of Subjectivity. Social & Cultural Geography 10 (6): 657–674.

- Holloway, J. 2013. The Space That Faith Makes: Towards a (Hopeful) Ethos of Engagement. In Religion and Place: Landscape, Politics and Piety, edited by P. Hopkins, L. Kong and E. Olson, 203–218. London: Springer.

- Horner, A. 2004. Reinventing the City: The Changing Fortunes of Places of Worship in Inner-city Dublin. In Surveying Ireland's Past: Multidisciplinary Essays in Honour of Anngret Simms, edited by H. B. Clarke, J. Prunty and M. Hennessy, 665–688. Dublin: Geography Publications.

- Inglis, T. 1998. Moral Monopoly: The Rise and Fall of the Catholic Church in Modern Ireland, 2nd ed. Dublin: UCD Press.

- Irish Independent. 1954. C.I.E. Employes’ [sic] Act of Homage to Our Lady. [http://archive.irishnewsarchive.com] 31 May.

- Irish Independent 1955a. Ceremony at Cabra. [http://archive.irishnewsarchive.com] 9 May.

- Irish Independent 1955b. Statue of Our Lady Unveiled. [http://archive.irishnewsarchive.com] 9 May.

- Irish Independent 1956. Blessing of Marian Year Statue [http://archive.irishnewsarchive.com] 10 December.

- Irish Press. 1952. C.I.E. Workers Erect Statue to Our Lady [http://archive.irishnewsarchive.com] 18 September.

- Kincaid, A. 2006. Postcolonial Dublin: Imperial Legacies and the Built Environment. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Knott, K. 2010. Cutting Through the Postsecular City: A Spatial Interrogation. In International Studies in Religion and Society, Volume 13: Exploring the Postsecular: The Religious, the Political and the Urban, edited by A. Molendijk, J. Beaumont and C. Jedan, 19–38. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill Academic Publishers.

- Kong, L. 2010. Global Shifts, Theoretical Shifts: Changing Geographies of Religion. Progress in Human Geography 34 (6): 755–776.

- Lawless, C. 2010. Devotion and Representation in Nineteenth‐century Ireland. In Visual, Material & Print Culture in Nineteenth‐century Ireland, edited by C. Breathnach and C. Lawless, 85–97. Dublin: Four Courts Press.

- Lee, L. 2015. Recognizing the Non‐Religious: Reimagining the Secular. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press.

- Lynch, N. 2016. Domesticating the Church: The Reuse of Urban Churches as Loft Living in the Postsecular City. Social & Cultural Geography 17 (7): 849–870.

- Maher, G., and M. Cawley. 2016. Short‐term Labour Migration: Brazilian Migrants in Ireland. Population, Place, and Space 22 (1): 23–35.

- Marston, S., J. P. Jones, and K. Woodward. 2005. Human Geography Without Scale. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers NS 30: 416–432.

- Marston, S., K. Woodward, and J. P. Jones. 2007. Flattening Ontologies of Globalization: The Nollywood Case. Globalizations 4 (1): 45–63.

- Massey, D. 2005. For Space. London: Sage.

- Mcmanus, R. 2002. Dublin 1910–1940: Shaping the City and Suburbs. Dublin: Four Courts Press.

- Moore, A. 2008. Rethinking Scale as a Geographical Category: From Analysis to Practice. Progress in Human Geography 32 (2): 203–225.

- Moore, N. 2008. Dublin Docklands Reinvented: The Post‐Industrial Regeneration of a European City Quarter. Dublin: Four Courts Press.

- Ó broin, D., and P. Kirby. 2009. Power, Dissent and Democracy: Civil Society and the State in Ireland. Dublin: A&A Farmar.

- O'callaghan, C., S. Kelly, M. Boyle, and R. Kitchin. 2015. Topologies and Topographies of Ireland's Neoliberal Crisis. Space and Polity 19 (1): 31–46.

- O'connor, P. 2011. A Parish Far From Home: How Gaelic Football Brought the Irish in Stockholm Together. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

- O'mahony, E. 2010. Religious Practice and Values in Ireland: A Summary of European Values Study 4th Wave Data. Maynooth, Ireland: Irish Catholic Bishops Conference.

- Orsi, R. 2010. The Madonna of 115th Street: Faith and Community in Italian Harlem, 3rd ed. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

- Pierce, J., D. G. Martin, and J. T. Murphy. 2010. Relational Place‐making: The Networked Politics of Place. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers NS 36: 54–70.

- Pile, S., R. Chris, N. Bartolini, and S. Mackian. 2016. The Place of Spirit: Modernity and the Geographies of Spirituality. Progress in Human Geography 41 (3): 3–354.

- Rodaway, P. 2015. Humanism and People‐Centered Methods. In Approaches to Human Geography: Philosophies, Theories People and Practices, edited by S. C. Aitken and G. Valentine, 334–343. London: Sage.

- Rose, G. 2007. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to the Interpretation of Visual Materials, 2nd ed. London: Sage.

- Rose, G. 2016. Rethinking the Geographies of Cultural “Objects” through Digital Technologies: Interface, Network, and Friction. Progress in Human Geography 40 (3): 334–351.

- Rowley, E. 2015. The Architect, the Planner and the Bishop: The Shapers of “Ordinary” Dublin, 1940–60. Footprint 16 (2): 69–88.

- Staeheli, L., and D. Mitchell. 2007. Locating the Public in Research and Practice. Progress in Human Geography 31 (6): 792–811.

- Staeheli, L., D. Mitchell, and C. Nagel. 2009. Making Publics: Immigrants, Regimes of Publicity and Entry to “the Public”. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 27: 633–648.

- Stevenson, D., K. Dunn, A. Possamai, and A. Piracha. 2010. Religious Belief Across “Postsecular” Sydney: The Multiple Trends in (De)Secularisation. Australian Geographer 41 (3): 323–350.

- Tse, J. 2014. Grounded Theologies: “Religion” and the “Secular” in Human Geography. Progress in Human Geography 38 (2): 201–220.

- Tweed, T. A. 1999. Diasporic Nationalism and Urban Landscape: Cuban Immigrants at a Catholic Shrine in Miami. In Gods of the City: Religion and the American Urban Landscape, edited by R. Orsi, 131–154. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Ugba, A. 2008. A Part of and Apart from Society? Pentecostal Africans in the “New Ireland”. Translocations 4 (1): 86–101.

- van Kempen, R., and B. Wissink. 2014. Between Places and Flows: Towards a New Agenda for Neighborhood Research in an Age of Mobility. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 96 (2): 95–108.

- Whelan, K. 1983. The Catholic Parish, the Catholic Chapel and Village Development in Ireland. Irish Geography 16: 1–15.

- White, A., and M. Gilmartin. 2008. Critical Geographies of Citizenship and Belonging in Ireland. Women's Studies International Forum 31: 390–399.