Abstract

Research suggests that rumination is a causal factor for intrusive memories. These are disturbing autobiographical memories that pop into one's mind involuntarily, spontaneously, and repetitively. A three‐wave longitudinal study was conducted to replicate this finding and to test whether one route via which rumination leads to (an increase in) intrusive memories is via depressed affect. Secondary school students (n = 72) filled out self‐report questionnaires measuring their level of rumination, depressive symptoms (DS), and intrusive memories. These were administered at three different points, with 3 weeks in between each measurement. Two types of rumination were measured, that is, depressive rumination and rumination in response to intrusions. Both bootstrapping analyses and cross‐lagged analyses yielded evidence for DS as a partial mediator of the relationship between rumination and intrusion frequency. Both depressive rumination and rumination about the content of intrusive memories seemed to be maladaptive: They may exacerbate negative emotions, which in turn trigger intrusive memories. Ruminative thinking also directly led to (an increase in) intrusive memories. These findings might suggest that people suffering from intrusive memories may benefit not only from therapies directly aimed at reducing intrusions but also from therapies aimed at reducing rumination and DS.

Key words:

The authors would like to thank the students of Moretus Ekeren, and Mater Salvatoris Kapellen.

Intrusive memories are disturbing autobiographical memories that pop into one's mind involuntarily, spontaneously, and repetitively. They are commonly experienced in depression (e.g., Brewin, Hunter, Carroll, & Tata, Citation1996; Kuyken & Brewin, Citation1994; Patel et al., Citation2007; Reynolds & Brewin, Citation1999). Several studies in patients suffering from major depressive disorder have shown that the frequency of intrusive memories is related to symptom severity (Brewin, Reynolds, & Tata, Citation1999; Kuyken & Brewin, Citation1994, Citation1995), or even the presence of a diagnosis of major depressive disorder (Spenceley & Jerrom, Citation1997). Furthermore, evidence for a link between intrusive memories and depressive symptoms (DS) is also found in non‐clinical studies (e.g., Hauer, Wessel, & Merckelbach, Citation2006).

There is good evidence (Birrer, Michael, & Munsch, Citation2007; Guastella & Moulds, Citation2007; Watkins, Citation2004) that intrusions are associated with rumination. In its original conceptualisation (e.g., Nolen‐Hoeksema, Citation1991), rumination is tied to depression and refers to ‘repetitively thinking about one's (depressed) feelings and about their causes, meanings, and consequences’ (p. 569). Likewise, the focus of rumination may be on a stressful or traumatic event that is represented in intrusive memories (e.g., Clohessy & Ehlers, Citation1999) rather than on depressed mood. In general, rumination is thought to trigger negative intrusive memories (Birrer et al., Citation2007). For example, when a ruminative thinking style is experimentally induced before a stressor, individuals report more intrusions about the stressor as compared with when a non‐ruminative thinking style is induced (Guastella & Moulds, Citation2007; Watkins, Citation2004).

The question remains through which mechanism rumination leads to (an increase in) intrusive memories. As there appears to be much overlap between intrusive memories of post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) patients and depressed patients (Reynolds & Brewin, Citation1998, Citation1999), explanatory models of PTSD may offer relevant cues. One such model is that of Ehlers and Clark (Citation2000). The central assumption of this model is that PTSD is characterised by a sense of current threat. This perception would be fuelled by the way in which a traumatic event and/or its consequences are appraised. According to Ehlers and Clark, various maladaptive behavioural strategies and cognitive processing styles or emotion‐regulation strategies, for example rumination, may increase PTSD symptoms such as intrusive memories.

Rumination might contribute to an increase in intrusive memories in at least two ways. To begin with, rumination may augment the frequency of intrusive memories via the strengthening of problematic appraisals of the trauma (e.g., ‘the trauma has ruined my life’). In addition, Ehlers and Clark argue that rumination may exacerbate negative emotions, which in turn provide internal retrieval cues that trigger intrusions. And although the term ‘current threat’ that Ehlers and Clark use in their PTSD model may not be readily applicable to the case of depression, the idea of rumination leading to intrusive memories via the strengthening of negative appraisals and/or via negative affect may nevertheless be of relevance for or applicable to a depression model.

It might indeed be the case that DS mediate the relationship between rumination and intrusive memories, as rumination is associated not only with intrusions but also with negative affect. Several recent studies demonstrated that people who tend to ruminate in stressful situations have a heightened vulnerability to experience major depressive episodes and have more prolonged DS (see Nolen‐Hoeksema, Citation2004, and Watkins, Citation2008, for a review). In addition, several studies have also pointed to a significant positive correlation between rumination about (the content of) intrusive memories (e.g., dwelling on how the event could have been prevented, go over what happened again and again) and DS (Ehring, Frank, & Ehlers, Citation2008; Starr & Moulds, Citation2006). Dysphoria is associated with intrusive memories and with attempts to ruminate on these memories (Williams & Moulds, Citation2007a, Citation2007b). Moreover, rumination about a negative life event (as compared with distraction) leads to a sadder mood and to the maintenance of more distressing and more negative intrusive memories in students (Ehring, Fuchs, & Kläsener, Citation2009; Williams & Moulds, Citation2010).

Rumination about intrusions and intrusive memories are similar concepts that share many characteristics. Both are recurring cognitive factors that are associated with depression and trauma and are experienced spontaneously and involuntarily. However, intrusive memories are autobiographical memories that unexpectedly pop into one's mind, whereas rumination refers to the act of repeatedly thinking about disturbing thoughts, such as unwanted autobiographical memories (i.e., intrusive memories) and/or unwanted or disturbing feelings (e.g., depressed affect). Put differently, intrusive memories are elements of autobiographical memory. Rumination about intrusive memories are characterised as evaluations, metacognitions, or ‘what if’ thoughts regarding this autobiographical event. Moreover, studies have shown that rumination is generally a relatively long‐lasting train of thoughts with varying content, whereas intrusive memories are mainly sensory in nature and shorter in duration (Evans, Ehlers, Mezey, & Clark, Citation2007; Speckens, Ehlers, Hackmann, Ruths, & Clark, Citation2007).

Taken together, research suggests (1) that DS are associated with intrusive memories and (2) that rumination (at least partly) causes DS and intrusive memories. In line with suggestions made by Cole and Maxwell (Citation2003), we set up a three‐wave longitudinal study to test the hypothesis that DS mediate the relationship between rumination and intrusion frequency (Ehlers & Clark, Citation2000). For practical reasons, we chose to investigate this in an adolescent rather than an adult sample. As far as we know, there is no reason to assume that the relationships of the variables of interest are different for adolescents than for adults. Rumination is significantly positively related with DS in younger adults, middle‐aged adults, and older adults (Nolen‐Hoeksema & Aldao, Citation2011). Because we are interested in DS and in intrusive memories, we chose to measure two types of rumination, namely depressive rumination and rumination about intrusions. We hypothesise that both types of rumination cause DS, which cause in their turn (an increase in) intrusive memories.

Method

Participants and procedure

A total of 72 Belgian secondary school students, of whom 43.7% were girls, participated in class group without compensation. Five schools in the region of Antwerp were contacted and informed about the study. Three schools decided to participate and gave permission to invite all students of the sixth grade to participate. All invited students agreed to take part in the study. The mean participant age at Time 1 was 17.06 years (standard deviation (SD) = 0.75; range from 16 to 19 years). Participants signed a consent form before participating at Time 1. They were informed that they could refuse to fill out a question or a questionnaire at any time, without consequences. A code based on their class number was used to protect their confidentiality. Level of rumination, DS, and intrusions were measured at three separate moments in time, with 3 weeks in between each measurement. As in most longitudinal studies, data were missing at different time points for different participants. In total, at the scale level, 6.95% of the data was missing.

Questionnaires

Ruminative Response Scale (RRS; Treynor, Gonzalez, & Nolen‐Hoeksema, Citation2003)

The RRS assesses the tendency to ruminate when feeling sad, down, or depressed. We adapted the instructions so that the answers referred to the level of rumination in the past week. The items elicit reactions to mood that are self‐focused, symptom‐focused, and focused on the mood's possible consequences and causes. In this study, we used the brooding and reflective pondering subscales of the RRS, as identified by Treynor et al. (Citation2003; also see Schoofs, Hermans, & Raes, Citation2010). They each contain five items. We extracted these items from the Dutch RRS version by Raes and Hermans (Citation2007), which has good psychometric properties (Schoofs et al., Citation2010; also see Raes et al., Citation2009). Examples of items are ‘Go someplace alone to think about your feelings’ and ‘Why do I always react this way?’ Responses are scored on a 10‐point Likert scale, from not at all (1) to very much (10). A total sum score was used in our analyses. Cronbach's alpha in this study was 0.87 at Time 1 and 0.95 at Time 3.

Ruminative Responses to Intrusions Questionnaire (RRIQ; Clohessy & Ehlers, Citation1999)

The RRIQ is a self‐report scale that measures intrusive memory frequency, associated distress, the meaning attributed to intrusive memories, and the extent to which individuals employ dissociation, rumination, and suppression strategies to control their memories. In this study, only the subscale measuring ruminative responses to intrusions (RRIQ) was used. It contains eight items, preceded by ‘What do you do when memories of the traumatic event pop into your mind? Please circle the answer that applied best to you during the past week’. Examples are ‘I think about how life would have been different if the event had not occurred’ or ‘I dwell on how the event could have been prevented’. Responses are scored on a 4‐point Likert scale, from never (1) to always (4). The English version has shown good reliability and validity (Ehring, Ehlers, & Glucksman, Citation2006). In this study, the Dutch version of Ehring (Citation2008) was used, with two adaptations: Firstly, we replaced ‘traumatic event’ with ‘an interfering/negative event’, as our study was performed in a non‐clinical sample. Secondly, we did not restrict the answers to the past week, as in the original version, but asked to indicate the answer that applied best ‘in general’. This scale can be filled out by all participants, in contrast to the original scale, which can only be filled out by participants who experienced intrusions in the past week. Cronbach's alpha in this study was 0.72 at Time 1 and 0.86 at Time 3.

Intrusion Frequency Measurement (IFM)

Using one question, participants were asked to indicate how often they experience intrusions on a 4‐point scale Likert scale, from never (1) to always (4). The question was ‘After a dramatic/negative personal experience or event, how often do involuntary memories of this event tend to suddenly pop into your mind in the following days or weeks?’ This question was modelled after an item of an intrusion interview by Hackmann, Ehlers, Speckens, and Clark (Citation2004).

Depression Scale (DASS; Lovibond & Lovibond, Citation1995)

The DASS‐21 is a self‐report scale that measures three negative emotional states: Depression, Anxiety, and Stress. In this study, only the subscale measuring DS was used. It contains seven items. Participants are asked to indicate how much statements as ‘I was unable to become enthusiastic about anything’ applied to them over the past week, on a 4‐point Likert scale ranging from did not apply to me at all (0) to applied to me very much, or most of the time (3). The Dutch version was used (de Beurs, van Dyck, Marquenie, Lange, & Blonk, Citation2001). This version has good psychometric properties (Nieuwenhuijsen, de Boer, Verbeek, Blonk, & van Dijk, Citation2003). Cronbach's alpha in this study was 0.70 at Time 1 and 0.87 at Time 3.

Analyses

The hypothesised mediation model was tested using a bootstrapping procedure and structural equation modeling (SEM).

Results

Preliminary analyses

Table shows means and SDs of the measures used in this study. Correlations between level of rumination, DS, and intrusions at Times 1–3 are reported in Table .

Table 1. Means (M) and standard deviations (SDs) of all measures at the three time points

Table 2. Pearson correlations of all measures at all time points

Bootstrapping analyses

To test the significance of the hypothesised mediation model, a non‐parametric, resampling approach (bootstrapping procedure; Preacher & Hayes, Citation2008) was used. When one has three waves of data, one can use Time 1 data for the predictor, Time 2 data for the mediator (controlling for Time 1 mediator data), and Time 3 data for the criterion outcome (controlling for Time 2 criterion outcome data; Rose, Holmbeck, Coakley, & Franks, Citation2004). As such, we used rumination scores (RRS or RRIQ) at Time 1 as the independent variable, DS at Time 2 as the mediator variable, and intrusion frequency (IFM) at Time 3 as the dependent variable. We controlled for DS at Time 1 and intrusion frequency at Time 2.

Both models, that is, the model with the RRS and the model with the RRIQ, fit the data well. For the model with the RRS, R 2 = 0.33, F(4, 51) = 6.37, p < .001. For the model with the RRIQ, R 2 = 0.42, F(4, 52) = 9.57, p < .001. Bootstrap results for the indirect effects showed that zero just fell out the 95% confidence intervals (CI RRS: 0.0003–0.0205; CIRRIQ:−0.0001–0.0592). These findings tentatively suggest that DS mediate the relationship between rumination and intrusions, as hypothesised. Participants who ruminated more at Time 1 had more DS at Time 2 and experienced more intrusions at Time 3.Footnote1

Cross‐lagged analyses

Cross‐lagged analysis with SEM was used to test our hypothesised mediation model in an alternative way. Participants with and without complete data were compared using Little's (Citation1988) Missing Completely At Random test. A non‐significant test statistic, χ2 (42) = 6.11, ns, suggested that missing values could be reliably estimated. Accordingly, to deal with missing values, we used the full information maximum likelihood procedure provided in MPLUS 4.0 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2002), which gives more reliable and less biased results than conventional methods such as listwise deletion (Schafer & Graham, Citation2002). Because of the relatively small sample size and the amount of parameters that had to be estimated, we could only use two measurement points for this analysis (Kline, Citation2006). To cover the total time span studied in the present study, we focused on Time 1 and Time 3 measurements for all analyses. We first tested two models including rumination (RRS in the first model and RRIQ in the second) and intrusion frequency (IFM, in both models) to explore the direct path between the dependent and the independent variable of our hypothesised mediation model. Next, we included the hypothesised mediator DS in these models, as recommended by Holmbeck (Citation1997). To ascertain the direction of effects, all cross‐lagged paths were included in these models.

The first cross‐lagged models tested included level of rumination and intrusion frequency. Within‐time associations at Times 1 and 3, autoregressive paths, and cross‐lagged paths were estimated. We used standard model fit indices (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). The chi‐squared index, which tests the null hypothesis of perfect fit to the data, should be as small as possible; the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) should be less than 0.08; and the non‐normed fit index (NNFI) and the comparative fit index (CFI) should exceed 0.90 and preferably 0.95. As our models were saturated, fit was by definition perfect (df = 0; χ2 = 0; RMSEA = 0; CFI = 1; NNFI = 1). In line with recommendations by Kline (Citation2006), models were not trimmed based on empirical considerations.

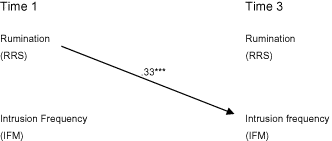

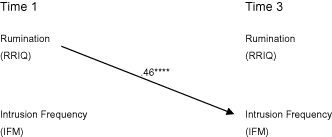

Fig. 1 displays the standardised structural coefficients for the RRS. Level of rumination positively (Time 1) predicted intrusion frequency (Time 3). Intrusion frequency (Time 1) did not predict level of rumination (Time 3). Fig. 2 displays the standardised structural coefficients for the RRIQ. Again, level of rumination (Time 1) positively predicted intrusion frequency (Time 3). Intrusion frequency (Time 1) did not predict level of rumination (Time 3).

Figure 1. Cross‐lagged path model linking rumination (RRS) and intrusion frequency (IFM). Within‐time correlations and stability coefficients are not presented for reasons of clarity; significant cross‐lagged paths are displayed. All path coefficients are standardised. ***p < .01.

Figure 2. Cross‐lagged path model linking rumination (RRIQ) and intrusion frequency (IFM). Within‐time correlations and stability coefficients are not presented for reasons of clarity; significant cross‐lagged paths are displayed. All path coefficients are standardised. ****p < .001.

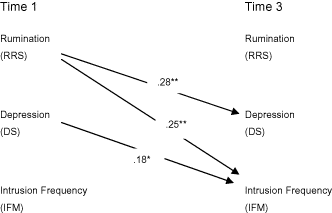

Next, DS were included in the models. All within‐time associations at Times 1 and 3, all autoregressive paths, and all cross‐lagged paths were estimated. As our models were saturated, fit was by definition perfect. Again, as recommended by Kline (Citation2006), we chose not to trim our models based on empirical considerations. Fig. 3 displays all standardised structural coefficients for the RRS. Level of rumination (Time 1) positively predicted DS (Time 3) and intrusion frequency (Time 3). DS (Time 1) positively predicted intrusion frequency (Time 3). These findings support partial mediation, with DS as a mediator of the relationship between depressive rumination and intrusion frequency.

Figure 3. Cross‐lagged path model linking rumination (RRS), depressive symptoms (DS), and intrusion frequency (IFM). Within‐time correlations and stability coefficients are not presented for reasons of clarity; significant cross‐lagged paths are displayed. All path coefficients are standardised. *p < .10, **p < .05.

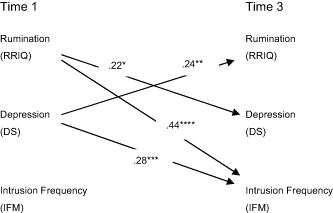

Fig. 4 displays all standardised structural coefficients for the RRIQ. Again, level of rumination (Time 1) positively predicted DS (Time 3) and intrusion frequency (Time 3). DS (Time 1) positively predicted intrusion frequency (Time 3). These findings support partial mediation, with DS as a mediator of the relationship between rumination in response to intrusions and intrusion frequency. In addition, DS (Time 1) positively predicted rumination (Time 3).

Figure 4. Cross‐lagged path model linking rumination (RRIQ), depressive symptoms (DS), and intrusion frequency (IFM). Within‐time correlations and stability coefficients are not presented for reasons of clarity; significant cross‐lagged paths are displayed. All path coefficients are standardised. *p < .10, **p < .05, ***p < .01, ****p < .001.

Discussion

The findings of our three‐wave longitudinal study yield evidence for depression symptoms as a partial mediator of the relationship between rumination and intrusion frequency. This was true when rumination was conceptualised as depressive rumination and rumination in response to intrusions. Bootstrapping analyses suggested that participants who ruminated more felt more depressed 3 weeks later and experienced more intrusions again 3 weeks later. These results were confirmed by path analyses. The direct path from rumination to intrusion frequency was significant too, and its strength did not reduce sharply after including the mediator in the models. We therefore conclude that partial (and not complete) mediation occurred. So, we did find some evidence for Ehlers and Clark's (Citation2000) suggestion that rumination may exacerbate negative emotions, which in turn provide internal retrieval cues that trigger intrusions. Or, put differently, one (but not the only) pathway through which ruminative thinking leads to (an increase in) intrusions might be via negative/depressed affect. Our findings are also in line with previous studies demonstrating that DS are associated with intrusions (Brewin et al., Citation1999; Hauer et al., Citation2006; Kuyken & Brewin, Citation1994, Citation1995) and that rumination (at least partly) causes DS (Ehring et al., Citation2008; Starr & Moulds, Citation2006; see Nolen‐Hoeksema, Citation2004, and Watkins, Citation2008, for a review) and intrusions (Ehring et al., Citation2009; Williams & Moulds, Citation2010). They extend these findings by clarifying the interrelationship between rumination, DS, and intrusion frequency. The findings may indicate that rumination leads directly and indirectly, namely via depressed affect, to (an increase in) intrusions.

Provided that these findings are replicated in future studies, they may have important clinical implications. They suggest that individuals who suffer from intrusions might, in addition to interventions directly aimed at reducing intrusions, also be helped by interventions aimed at reducing rumination. Therapists might try to promote acceptance and mindfulness towards one's inner experiences. Mindfulness training, such as the Mindfulness‐Based Stress Reduction Program (Kabat‐Zinn, Citation1982, Citation1990) or the Mindfulness‐Based Cognitive Therapy (Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, Citation2002), reduces rumination and DS (e.g., Deyo, Wilson, Ong, & Koopman, Citation2009). Examples of treatment programmes that were specifically developed to tackle rumination are metacognitive therapy (Papageorgiou & Wells, Citation2004) and rumination‐focused cognitive behaviour therapy for residual depression (Watkins et al., Citation2007). Redirecting attention might be another way to counter rumination. A study in high worriers showed that paying attention to benign stimuli during an attention modification task leads to more positive thoughts, less worrying, and less intrusions in comparison with allocating attention to threatening stimuli (Hayes, Hirsch, & Mathews, Citation2010).

A first limitation of this study is the use of self‐report scales to measure the level of depression, intrusions, and rumination. Such reports may be subject to demand effects. A second limitation is the use of a single‐item measure to assess intrusion frequency. A third limitation is our relatively small sample size, which did not allow us to use our three data‐waves in the cross‐lagged analyses. A fourth limitation is the use of a non‐selected student population, from whom we did not obtain formal diagnostic information (e.g., information on past or current episodes of depression or PTSD). Future research could replicate this study in a larger sample, in an adult rather than an adolescent sample, and in clinical groups (e.g., patients diagnosed with clinical depression). Future research could also include another type of rumination about intrusions, namely rumination about the experience of intrusions, regardless of their content (e.g., ‘The fact that I experience intrusions means that I am going crazy’). Such appraisals about intrusions are associated with PTSD severity (Clohessy & Ehlers, Citation1999; see also Ehlers & Clark, Citation2000) and level of depression (Williams & Moulds, Citation2008).

In summary, this study yielded evidence for DS partially mediating the relationship between rumination and intrusion frequency. Both depressive rumination and rumination about the content of intrusions worsen DS, which in turn trigger intrusive memories. Rumination also directly led to (an increase in) intrusive memories. If replicated, these findings may suggest that people suffering from intrusive memories might also benefit from therapies intended at reducing rumination and/or DS.

Notes

The authors would like to thank the students of Moretus Ekeren, and Mater Salvatoris Kapellen.

1. One could argue that the current model is but one of many mediation models using these three variables that might be valid. We did test such other mediation models, e.g., with rumination as a mediator of the relationship between intrusion frequency and depression scores, and with intrusion frequency as a mediator of the relationship between rumination and depression scores. However, we did not find evidence for these alternative mediation models.

References

- de Beurs, E., van Dyck, R., Marquenie, L. A., Lange, A., & Blonk, R. (2001). De DAAS: Een vragenlijst voor het meten van depressie, angst en stress [The DAAS: A questionnaire for the measurement of depression, anxiety and stress]. Gedragstherapie, 34, 35–53. Retrieved from http://www2.psy.unsw.edu.au/groups/dass

- Birrer, E., Michael, T., & Munsch, S. (2007). Intrusive images in PTSD and in traumatized and non‐traumatised depressed patients: A cross‐sectional clinical study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 2053–2065. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465811000087

- Brewin, C. R., Hunter, E., Carroll, F., & Tata, P. (1996). Intrusive memories in depression: An index of schema activation? Psychological Medicine, 26, 1271–1276. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291700035996

- Brewin, C. R., Reynolds, M., & Tata, P. (1999). Autobiographical memory processes and the course of depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108, 511–517. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0021‐843X.108.3.511

- Clohessy, S., & Ehlers, A. (1999). PTSD symptoms, response to intrusive memories and coping in ambulance service workers. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38, 251–265. doi:https://doi.org/10.1348/014466599162836

- Cole, D. A., & Maxwell, S. E. (2003). Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112, 558–577. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0021‐843X.112.4.558

- Deyo, M., Wilson, K. A., Ong, J., & Koopman, C. (2009). Mindfulness and rumination: Does mindfulness training lead to reductions in the ruminative thinking associated with depression? Journal of Science and Healing, 5, 265–271. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2009.06.005

- Ehlers, A., & Clark, D. M. (2000). A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38, 319–345. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005‐7967(99)00123‐0

- Ehring, T. (2008). The Responses to Intrusions Questionnaire—Dutch version (RIQ‐NL) (Unpublished document). University of Amsterdam.

- Ehring, T., Ehlers, A., & Glucksman, E. (2006). Contribution of cognitive factors to the prediction of posttraumatic stress disorder, phobia and depression after road traffic accidents. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 1699–1716. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.11.013

- Ehring, T., Frank, S., & Ehlers, A. (2008). The role of rumination and reduced concreteness in the maintenance of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression following trauma. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 32, 488–506. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608‐006‐9089‐7

- Ehring, T., Fuchs, N., & Kläsener, I. (2009). The effects of experimentally induced rumination versus distraction on analogue posttraumatic stress symptoms. Behavior Therapy, 40, 403–413. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2008.10.001

- Evans, C., Ehlers, A., Mezey, G., & Clark, D. M. (2007). Intrusive memories and ruminations related to violent crime among young offenders: Phenomenological characteristics. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20, 183–196. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20204

- Guastella, A. J., & Moulds, M. L. (2007). The impact of rumination on sleep quality following a stressful life event. Personality and Individual Differences, 42, 1151–1162. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.04.028

- Hackmann, A., Ehlers, A., Speckens, A., & Clark, D. M. (2004). Characteristics and content of intrusive memories in PTSD and their changes with treatment. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 17, 231–240. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOTS.0000029266.88369.fd

- Hauer, B. J. A., Wessel, I., & Merckelbach, H. (2006). Intrusions, avoidance and overgeneral memory in a non‐clinical sample. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 13, 264–268. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.495

- Hayes, S., Hirsch, C., & Mathews, A. (2010). Facilitating a benign attentional bias reduces negative thought intrusions. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119, 235–248. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018264

- Holmbeck, G. (1997). Toward terminological, conceptual, and statistical clarity in the study of mediators and moderators: Examples from the child clinical and pediatric psychology literatures. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65, 599–610. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022‐006X.65.4.599

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Kabat‐zinn, J. (1982). An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: Theoretical considerations and preliminary results. General Hospital Psychiatry, 4, 33–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0163‐8343(82)90026‐3

- Kabat‐zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress pain and illness. New York: Delacorte.

- Kline, R. B. (2006). Principles and practices of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

- Kuyken, W., & Brewin, C. R. (1994). Intrusive memories of childhood abuse during depressive episodes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 32, 525–528. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0005‐7967(94)90140‐6

- Kuyken, W., & Brewin, C. R. (1995). Autobiographical memory functioning in depression and reports of early abuse. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104, 585–591. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0021‐843X.104.4.585

- Little, R. J. A. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83, 1198–1202. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/

- Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (2nd. ed.). Sydney: Psychology Foundation.

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2002). Mplus user's guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

- Nieuwenhuijsen, K., de Boer, A. G., Verbeek, J. H., Blonk, R. W., & van Dijk, F. J. (2003). The Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS): Detecting anxiety disorder and depression in employees absent from work because of mental health problems. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 60, 77–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.60.suppl_1.i77

- Nolen‐hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100, 569–582. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0021‐843X.100.4.569

- Nolen‐hoeksema, S. (2004). The response style theory. In C. Papageorgiou & A. Wells (Eds.), Depressive rumination: Nature, theory and treatment (pp. 107–123). West Sussex: Wiley.

- Nolen‐hoeksema, S., & Aldao, A. (2011). Gender and age differences in emotion regulation strategies and their relationship to depressive symptoms. Personality and Individual Differences, 51, 704–708. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.06.012

- Papageorgiou, C., & Wells, A. (2004). Depressive rumination. Nature, theory and treatment. Chichester: Wiley.

- Patel, T., Brewin, C. R., Wheatley, J., Wells, A., Fisher, P., & Myers, S. (2007). Intrusive images and memories in major depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 2573–2580. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2007.06.004

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. doi:https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

- Raes, F., & Hermans, D. (2007). The revised version of the Dutch Ruminative Response Scale. Unpublished instrument.

- Raes, F., Schoofs, H., Hoes, D., Hermans, D., Van den eede, F., & Franck, E. (2009). ‘Reflection’ en ‘brooding’ als subtypes van rumineren: een herziening van de Ruminative Response Scale. [Reflection and brooding as subtypes of rumination: A revision of the Ruminative Response Scale]. Gedragstherapie, 42, 205–214.

- Reynolds, M., & Brewin, C. R. (1998). Intrusive cognitions, coping strategies and emotional responses in depression, post‐traumatic stress disorder and a non‐clinical population. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36, 135–147. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005‐7967(98)00013‐8

- Reynolds, M., & Brewin, C. R. (1999). Intrusive memories in depression and posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 37, 201–215. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005‐7967(98)00132‐6

- Rose, B., Holmbeck, G. N., Coakley, R. M., & Franks, L. (2004). Mediator and moderator effects in developmental and behavioral pediatric research. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 25, 1–10. Retrieved from http://www.sauder.ubc.ca/

- Schafer, J. L., & Graham, J. W. (2002). Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7, 147–177. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/1082‐989X.7.2.147

- Schoofs, H., Hermans, D., & Raes, F. (2010). Brooding and reflection as subtypes of rumination: Evidence from confirmatory factor analysis in nonclinical samples using the Dutch Ruminative Response Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 32, 609–617. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862‐010‐9182‐9

- Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2002). Mindfulness and the prevention of depression: A guide to the theory and practice of mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy. New York: Guilford Press.

- Speckens, A. E. M., Ehlers, A., Hackmann, A., Ruths, F. A, & Clark, D. M. (2007). Intrusive memories and rumination in patients with post‐traumatic stress disorder: a phenomenological comparison. Memory, 15, 249–257. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210701256449

- Spenceley, A., & Jerrom, W. (1997). Intrusive traumatic childhood memories in depression: A comparison between depressed, recovered, and never depressed women. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 25, 309–318. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465800018713

- Starr, S., & Moulds, M. L. (2006). The role of negative interpretations of intrusive memories in depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 93, 125–132. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2006.03.001

- Treynor, W., Gonzalez, R., & Nolen‐hoeksema, S. (2003). Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27, 247–259. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023910315561

- Watkins, E., Scott, J., Wingrove, J., Rimes, K., Bathurst, N., Steiner, H., … Malliaris, Y. (2007). Rumination‐focused cognitive behaviour therapy for residual depression: A case series. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 2144–2154. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2006.09.01

- Watkins, E. R. (2004). Adaptive and maladaptive ruminative self‐focus during emotional processing. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49, 1037–1052. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2004.01.009

- Watkins, E. R. (2008). Constructive and unconstructive repetitive thought. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 163–206. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033‐2909.134.2.163

- Williams, A. D., & Moulds, M. L. (2007a). Cognitive avoidance of intrusive memories: Recall vantage perspective and associations with depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 1141–1153. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2006.09.005

- Williams, A. D., & Moulds, M. L. (2007b). An investigation of the cognitive and experiential features of intrusive memories in depression. Memory, 15, 912–920. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210701508369

- Williams, A. D., & Moulds, M. L. (2008). Negative appraisals and cognitive avoidance of intrusive memories in depression: A replication and extension. Depression and Anxiety, 25, 26–33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20409

- Williams, A. D., & Moulds, M. L. (2010). The impact of ruminative processing on the experience of self‐referent intrusive memories in dysphoria. Behavior Therapy, 41, 38–45.