Abstract

This study builds on previous research on information technology implementation and usage in small and medium‐sized enterprises (SMEs) and applies a special focus on social networks. Specifically, this research investigates antecedents of social network usage in SMEs and respective performance outcomes. The results show that entrepreneurial orientation is positively related to social network usage in SMEs, whereas responsive market orientation shows no effect. Social network usage is not directly related to SME growth; yet it mediates the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and SME growth. Interestingly, large firms show the opposite effects regarding antecedents and performance‐related consequences of social network usage.

Introduction

The positive performance effect of information technology implementation and usage on firm performance has been confirmed by several studies (see, e.g., Petter, DeLone, and McLean Citation2008; Sabherwal, Jeyaraj, and Chowa Citation2006). Whereas most studies have been conducted in a large firm context, Johnston, Wade, and McClean (Citation2007) confirm that the implementation of information and communication technologies is also beneficial for SMEs. However, certain factors exist that influence and potentially inhibit technology implementation and usage by SMEs.

Internal factors are attitudes toward and knowledge of the CEO/owner manager about information technology implementation and usage, organizational context such as technological and human resource infrastructure (see, e.g., Bharadwaj and Soni Citation2007; Caldeira and Ward Citation2002; Thong Citation1999), financial capacities (Kannabiran and Dharmalingam Citation2012; Nguyen Citation2009), firm size and growth (see, e.g., Malaquias and Hwang Citation2015; Nguyen, Newby, and Macaulay Citation2015; Premkumar Citation2003), and strategic orientation of the firm such as innovative capabilities (see, e.g., Dyerson, Spinelli, and Harindranath Citation2016; Fillis, Johansson, and Wagner Citation2003; Lee and Runge Citation2001). External factors shaping technology usage in the SME context consist of competitive pressures (see, e.g., Bruque and Moyano Citation2007; Kannabiran and Dharmalingam Citation2012; Nguyen Citation2009), external support (see, e.g., Solomon and Perry Citation2011; Solomon et al. Citation2013; Thong Citation2001), and social expectations of information technology use (see, e.g., Lee and Runge Citation2001; Nguyen, Newby, and Macaulay Citation2015; Riemenschneider, Harrison, and Mykytyn Citation2003).

Since there are a variety of factors shaping the implementation and usage of information technologies in the SME context, there is reason to believe that the special characteristics of SMEs also influence the implementation and usage of social media technologies (Bulearca and Bulearca Citation2010; Keel and Bernet Citation2013). As an Internet‐based application (Kaplan and Haenlein Citation2010, p. 61), social media “provides a way people share ideas, content, thoughts and relationships online” (Scott Citation2009, p. 38). This online engagement can take on various designs from simple interaction (e.g., blogs, chats) over collaboration to cocreation (e.g., tagging, content editing; Aral, Dellarocas, and Godes Citation2013), primarily applied in social networking sites. Such social networks (e.g., Facebook, MySpace, Twitter, LinkedIn, or XING—the European pendant to LinkedIn) allow individuals and groups to connect with each other and build networks based on a personal or company profile, resulting in considerable changes in the communications landscape (Kietzmann et al. Citation2011). In fact, using social networks enables firms to more actively engage consumers than traditional communication approaches (see, e.g., Castronovo and Huang Citation2012; Hoffman and Fodor Citation2010; Trusov, Bucklin, and Pauwels Citation2009). Consequently, recent paradigm shifts in marketing such as the service dominant logic (Vargo and Lusch Citation2004) or the relationship marketing perspective (Gummesson et al. Citation2012) point toward the need for using social media as communication tool. This is particularly the case in light of the potential to share timely and relevant information with stakeholders and to shift the focus from products to consumers. As a result, in 2015, 78 percent of the U.S. Fortune 500 companies used Twitter, 74 percent Facebook, and 21 percent blogging tools (Barnes, Lescault, and Holmes Citation2015). In Switzerland, as an example of German‐speaking countries under investigation in this study, almost all large companies (89 percent) were active social media users in 2013, whereas only 59 percent of all SMEs used this technology (Keel and Bernet Citation2013).

In this regard, a few studies exist that encourage the notion that social media usage and respective performance impacts differ between SMEs and large firms. Moran (Citation2009) as well as Chua, Deans, and Parker (Citation2009) point out that SMEs do not have the necessary resources to use social media effectively. Moreover, in compliance with the results regarding information technology use in general, SMEs are often managed by a single dominant owner/manager (Tocher and Rutherford Citation2009) who might lack knowledge about social media marketing and is usually involved in numerous aspects of management. In this regard, centralized power structures and a lack of formalized and sophisticated strategic planning (Williamson, Cable, and Aldrich Citation2002) might inhibit the development and execution of successful social network marketing strategies. At the same time, SMEs appear to understand the importance of social media as a marketing tool better than large companies (George and Simon Citation2011). Given their smaller scale, SMEs are supposed to be able to use customer insights faster (Nakara, Benmoussa, and Jaouen Citation2012) and more effectively than large companies (Carter Citation2011; Wickert and Herschel Citation2001). That is, we find contradicting results regarding the antecedents and effectiveness of social media marketing in SMEs.

Given this heterogeneity in terms of empirical findings, this study aims to develop a more fine‐grained understanding of the antecedents and performance‐related consequences of information technology usage in SMEs, with an emphasis on social network usage. With regard to antecedents, earlier studies found that especially the strategic orientation of firms influences the implementation and use of information technologies (see, e.g., Dyerson, Spinelli, and Harindranath Citation2016; Fillis, Johansson, and Wagner Citation2003; Lee and Runge Citation2001). Two strategic orientations that are particularly suited to explain behavioral firm‐level outcomes are entrepreneurial orientation (EO) and responsive market orientation (RMO) (Baker and Sinkula Citation2009; Eggers et al. Citation2013; Hakala Citation2011). We believe that SMEs possessing high levels of EO and RMO might be more active in using social networking sites, using those to exploit new and innovative opportunities (Fischer and Reuber Citation2011), ultimately leading to increasing firm growth (Macpherson and Holt Citation2007). We therefore investigate the relationship between social network usage and SME growth as an indicator of firm performance. All postulated relationships will be analyzed by taking account of contingencies such as industry and customer type. Both, EO and RMO as antecedents of social network usage, as well as the link between social network usage and SME growth have not been jointly investigated in previous studies. We aim to fill this research gap through a quantitative research design of 411 companies in German‐speaking countries as we additionally contrast social network usage of SMEs with large companies to better understand the specificities associated with firm size.

Theoretical Background

Literature Review

We conducted a systematic literature review of performance‐related outcomes and antecedents of social media usage to shed more light on this fast‐paced research field. The databases ABI/INFORM Complete, Science Direct and Business Source Complete were used to cover the time frame from 2013 until 2015. We performed two systematic searches in each database using the following search strings to search abstracts, titles, and keywords: (1) “social media” AND “firm size” as well as (2) “social media” AND “firm performance” OR “social media” AND “business performance.” We deliberately refrained from including “SME” and related search terms to obtain a holistic literature perspective that allows conclusions to be derived regarding the relevance of SMEs in the social media literature. Excluding papers that did not fit the business research context led to a reduction in the number of academic articles from 56 to 37 (see complete list in the appendix table). Overall, the literature review revealed only four studies that focus on SMEs. The results of this review are combined with earlier research contributions to further illustrate this research gap. Unless otherwise noted, the following studies were either conducted among large firms or do not distinguish between different firm sizes.

In terms of the performance effect of social media technology usage, the majority of identified studies focuses on “soft” performance outcomes. In other words, the outcome of social media is assessed as the number of “likes” on, for example, a product page or as increased brand credibility (Christodoulides Citation2009; Coulter and Roggeveen Citation2012). This includes better monitoring of brand images, more motivated customers (Aquino Citation2012), and stronger purchase intentions (Colliander and Dahlen Citation2011; Hutton and Fosdick Citation2011). In addition, increased message reach, and decreased contact costs (Kirchgeorg et al. Citation2009) as well as enhanced customer loyalty are used as performance measures in social media technology studies (Gummerus et al. Citation2012; Lipsman et al. Citation2012; Weinberg and Pehlivan Citation2011).

A number of studies also make the connection between social media technology usage and “hard” performance effects, including financial performance and/or firm growth. Gecti and Dastan (Citation2013) illustrate that social media usage positively affects business turnover, with this relationship being mediated by marketing cost savings and marketing‐based outputs such as increased brand recognition and customer loyalty. Martínez‐Núñez and Pérez‐Aguiar (Citation2014) find a positive relationship between the usage of online social networks and sales as well as pre‐tax profits. Qu et al. (Citation2013) show that certain online retailers' social activities on e‐commerce platforms improve a firm's revenue and transaction volume. Also, an effective management of online reviews affects firm performance in the hospitality industry, measured as the average daily rate and revenue per available room (Kim, Lim, and Brymer Citation2015). Jiang et al. (Citation2016) show that electronic word‐of‐mouth has a significant effect on a brand's market share. The number of “followers” and “likes” positively influence a firm's share value (Paniagua and Sapena Citation2014), and social media technology usage is associated with increased stock price and return on assets (Du and Jiang Citation2015). In this regard, two additional studies report that social media usage leads to increased stock performance (Schniederjans, Cao, and Schniederjans Citation2013; Yu, Duan, & Cao Citation2013). However, Jiang et al. (Citation2016) show that only social media behaviors of certain stakeholder groups can increase a firm's share value.

We identified three studies that are noteworthy for the SME context. Kudeshia, Sikdar, and Mittal (Citation2016) analyze the effectiveness of social media technology as a communication tool for SMEs and small scale entrepreneurs. They find that “Facebook likes” are converted into word‐of‐mouth, which results in increased purchase intentions. Michaelidou, Siamagka, and Christodoulides (Citation2011) research SMEs in business‐to‐business (B2B) environments and find that social networks are mainly used to achieve brand objectives, and that an overwhelming majority of users do not adopt any metrics to assess their effectiveness. Zaglia et al. (Citation2015) find in their study on CEOs of SMEs that trust in social networks, access to resources provided through social network memberships, and perceived value of social networking technologies lead to satisfaction with their usage and increase the intention of recommending social networks to other business partners. These outcomes are largely mediated by firm growth. With regard to firm size, Nickell, Rollins, and Hellman (Citation2013) find that social media use does not discriminate between high‐ and low‐performing firms.

In terms of antecedents of social media usage, only a few studies researched the conditions contributing to the intention to implement and the actual usage of social media technology, such as individual personal motivations, attitudes toward the medium, experience, or perceived popularity (Fitzgerald et al. Citation2014; Lee and Cho Citation2011; Sledgianowski and Kulviwat Citation2009). Our literature review revealed one study with a focus on SMEs that identified IT infrastructure capability, competitor pressure, marketing, and innovation management capabilities as key mechanisms through which small firms learn to develop a social media competence (Braojos‐Gomez, Benitez‐Amado, & Llorens‐Montes Citation2015). In a large firm context, Seo and Lee (Citation2016) find that concurrently preparing both technological and organizational initiatives is important for social media technology usage, along with a correct and precise understanding of the firm's core value proposition. Schultz, Schwepker, and Good (Citation2012) propose and empirically assess a model of social media usage among B2B salespeople, finding that the age of the salesperson negatively affects social media usage, whereas social media norms positively affect it. Customer‐oriented selling was not found to be positively related to social media usage, although it does have a positive effect on sales performance. In contrast, Harrigan et al. (Citation2015) show that an underlying customer relationship orientation is needed to drive social media technology use and customer engagement initiatives.

In sum, several studies exist that focus on the performance impact of social media technology usage. However, only few deal with antecedents or explicitly consider the special characteristics and challenges of social media technology use in the context of SMEs. Among those, only one study (Braojos‐Gomez, Benitez‐Amado, and Llorens‐Montes Citation2015) deals with antecedents of SMEs' social media usage. The remaining studies focusing on social media usage in SMEs are largely descriptive (Chua, Deans, and Parker Citation2009; Derham, Cragg, and Morrish Citation2011) or case‐based and anecdotal (Harris and Rae Citation2009; Öztamur and Karakadılar Citation2014; Pentina and Koh Citation2012; Stockdale, Ahmed, and Scheepers Citation2012). Although several studies assessed the direct effect of social media usage on financial performance and firm growth, none of these studies were conducted in an SME context. This is particularly interesting because firm growth is considered one of the most important goals for SMEs and the most commonly used performance indicator in entrepreneurship and strategy research (Carton and Hofer Citation2006). So, research is largely missing regarding a firm foundation on which SMEs can base strategic decisions that concern the usage of social media technology as a marketing tool (Hoffman and Novak Citation2012).

In order to resolve this opaqueness, this study focuses on the applicability of social network usage as social media technology in SMEs for three reasons. First, there is disagreement in the literature about what communication tools meet the characteristics of social media (e.g., Constantinides and Fountain Citation2008; Kaplan and Haenlein Citation2010; Vernuccio Citation2014). Second, social networking plays a central role in the realm of social media (Hennig‐Thurau et al. Citation2010). Third, social networking sites typically include a wide range of features, combining the functions of other social media sites such as content sharing communities or blogs (Enders et al. Citation2008).

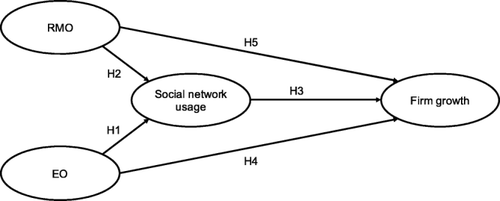

Development of Hypotheses

EO is used in the entrepreneurship and strategy literature to describe the strategic management style of firms with entrepreneurial tendencies (Lyon, Lumpkin, and Dess Citation2000). Although additional aspects of EO have been suggested in the literature (most notably autonomy and competitive aggressiveness), a general commonality among conceptualizations is the inclusion of innovativeness, risk‐taking, and proactiveness as central dimensions to define entrepreneurial strategic processes and firm‐level behaviors (Covin and Slevin Citation1991; Lumpkin and Dess Citation1996). Innovativeness reflects a firm's willingness to support new ideas, creativity, and experimentation in the development of internal solutions or external offerings. Proactiveness represents a forward‐looking and opportunity‐seeking perspective that provides an advantage over competitors' actions by anticipating future market demands. Risk‐taking is associated with a firm's readiness to make bold and daring resource commitments toward organizational initiatives with uncertain returns (Miller Citation1983).

Because proactive firms tend to adapt new technologies earlier than their competitors (Lumpkin and Dess Citation1996), it can be suggested that they have a stronger tendency to use social networking technologies to uncover and satisfy unarticulated customer needs. In this regard, Bruque and Moyano (Citation2007) found that an SME's proactive orientation leads to technological change. Furthermore, social networks help them not only analyze current customer needs, but also investigate future trends. Gaining new knowledge by listening to the crowd (Harris, Rae, and Grewal Citation2008) and discussing ideas offers the possibility to find new ideas and evaluate products (Mangold and Faulds Citation2009). Michaelidou, Siamagka, and Christodoulides (Citation2011) show that organizational innovativeness is associated with social media usage. This finding is in line with previous literature where the SME owner's innovativeness is positively correlated with information technology implementation (Lee and Runge Citation2001; Thong Citation1999). Also, a study by Braojos‐Gomez, Benitez‐Amado, and Llorens‐Montes (Citation2015) reveals that innovativeness enables SMEs to develop a social media competence. However, using social networks as a marketing tool can also be a risky endeavor because best practices in the SME context are scarce. This might in turn lead to ineffective or even negative outcomes. Although actual social network usage comes at little or no cost, it must be remembered that the development of social networking campaigns can be costly because companies have to recruit and keep personnel with specific know‐how, or outsource this task outright (Hoffman and Fodor Citation2010; Schmidt and Ralph Citation2011), which is a key issue for SMEs, typically being confronted with resource constraints. Furthermore, a company can encounter data privacy concerns (Steinman and Hawkins Citation2010). SMEs that implement new technologies can therefore be characterized by a greater risk orientation (Peltier, Schibrowsky, and Zhao Citation2009). Thus, not only proactiveness and innovativeness, but also a calculated willingness to take risks is required to make use of social networking technologies. We therefore postulate:

H1: There is a positive relationship between SMEs' entrepreneurial orientation and their social network usage.

Along with EO, social network usage in SMEs can also be influenced by RMO. RMO is the customer‐oriented part of the marketing orientation concept which can be defined as “the organization‐wide generation of market intelligence pertaining to current and future needs of customers, dissemination of intelligence horizontally and vertically within the organization, and organization‐wide action or responsiveness to market intelligence” (Kohli, Jaworski, and Kumar Citation1993, p. 467). Companies with a high RMO focus mainly on current, expressed customer needs and try to discover, understand, and satisfy these needs (Narver, Slater, and MacLachlan Citation2004).

Nguyen, Newby, and Macaulay (Citation2015) show that in small businesses, customers are the main driving force of information technology implementation, with customer orientation driving social media technology usage (Harrigan et al. Citation2015). Especially social networks provide a valuable basis for analyzing immediate customer needs (Livingstone Citation2008). Customers join brand communities for discussing products and services, or even create own forums in which they interact with like‐minded persons and share their knowledge (Arnone et al. Citation2010). This behavior results in the development of user‐generated content, allowing companies to explore customers' needs and expectations in detail. SMEs with a high RMO will therefore engage in the opportunity to analyze shared consumer information and thereby improve their products and services based on the content generated through the use of social networking technologies. Therefore, we formulate:

H2: There is a positive relationship between SMEs' responsive market orientation and their social network usage.

As prior research advocates a positive link between social media technology usage and a firm's financial performance (e.g., Kim, Lim, and Brymer Citation2015; Martínez‐Núñez and Pérez‐Aguiar Citation2014; Qu et al. Citation2013), also in the SME context, the use of social networks may be particularly promising in terms of firm growth, which again depends on the use of managerial and entrepreneurial resources. While entrepreneurial resources are required for opportunity exploration, managerial resources are essential to provide systems and processes to enable opportunity exploitation (Macpherson and Holt Citation2007). However, for SMEs with their resource constraints (Wiklund and Shepherd Citation2003), it is often not possible to engage in both exploration or exploitation, so most SMEs will be more oriented toward one of the two strategies (March Citation1991; Mitchell and Singh Citation1993). We argue that SMEs should focus on exploitation to promote firm growth. Firms focusing on exploitation compete based on their existing products and services, emphasizing quality and efficiency (Gupta, Smith, and Shalley Citation2006). In this regard, SMEs must pursue the goal of reducing variability and achieving high process and quality improvements through standardization. Therefore, SMEs require managerial resources that emphasize the efficient execution of processes and procedures (Hatak et al. Citation2016), and social networks that allow them to bring promising market opportunities to fruition through direct and more intense interaction with customers as a result. Consequently, social network usage supports entrepreneurial actions, which are associated with firm growth in SMEs (Fischer and Reuber Citation2011; Goffee and Scase Citation1995). We therefore assume:

H3: There is a positive relationship between social network usage and firm growth in SMEs.

Finally, along with analyzing EO and RMO as antecedents of social network usage, we also assess their direct growth impact. Many studies have investigated how a high EO leads to increased performance (e.g., Covin and Slevin Citation1989; Lumpkin and Dess Citation1996). Most noteworthy, the positive effect of EO on firm performance was confirmed by a meta‐analysis by Rauch et al. (Citation2009) and with a specific focus on the SME context, for example by Kraus and colleagues (Citation2012). In examining the causal relationship between EO and firm growth in SMEs and consistent with the resource‐based view, EO is seen as an organizational posture that enables the structuration, bundling, and leveraging of resources toward entrepreneurial aims (Ireland, Hitt, and Simon Citation2003). According to Wiklund and Shepherd (Citation2011), this posture is based on the notion that entrepreneurial strategy‐making and processes represent a valuable, rare, and inimitable gestalt through which firms can develop a competitive advantage, which in turn promotes firm growth (Anderson and Eshima Citation2013; Covin, Green, and Slevin Citation2006).

Also, previous studies have shown that companies that build their competitive strategy on the satisfaction of customer needs and that therefore constantly monitor the level of commitment and orientation to serving customers' needs show a positive performance outcome (Narver and Slater Citation1990; Narver, Slater, and MacLachlan Citation2004). SMEs can specifically overcome their size‐related disadvantages that distinguish them from large firms such as less market power or economies of scale by developing capabilities for closeness and responsiveness to market demands (e.g., Alpkan, Yilmaz, and Kaya Citation2007; Slater and Narver Citation1998). Consequently, and according to a study by Pelham (Citation2000), market‐oriented SMEs are more likely to achieve superior firm performance especially if they follow a growth/differentiation strategy.

Although both relationships have been tested broadly in the past, we believe that given the interaction of our study variables, and for the purpose of achieving a sufficiently thorough research model, an analysis of the final two hypotheses in this specific context makes sense:

H4: There is a positive relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and firm growth in SMEs.

H5: There is a positive relationship between responsive market orientation and firm growth in SMEs.

An overview of all hypotheses can be seen in Figure 1.

Methodology

Sample

Data were collected by drawing a random sample of companies in the four German‐speaking countries of Austria, Germany, Liechtenstein, and the German‐speaking part of Switzerland. Following a “key informant approach,” CEOs and top‐level managers from marketing and sales departments as the primary source of relevant knowledge and information (Lechner, Dowling, and Welpe Citation2006) with regard to our study context were contacted directly via email. A summary of the results was offered as an incentive for taking part in the study.

As the survey was geared toward non‐English‐speaking business executives, the entire questionnaire was subjected to double‐blind translation and back‐translation of the measuring instruments by two groups of independent translators (Brislin Citation1980). If questions did not have the same meaning after the back‐translation, the translators discussed the problem and agreed on a new wording for the question. Before conducting the survey, all translations were compared again with the original sources to identify and correct errors that may have arisen from interpretation differences.

To ensure that the questionnaire was understandable and valid, a pretest with 21 respondents that were similar to the target group was conducted (Hunt, Sparkman, and Wilcox Citation1982). This number corresponds with the views of Ferbe and Verdoorn (Citation1962) or of Boyd, Westfal, and Stasch (Citation1977) that 12 or 20 test persons (respectively) are sufficient as a pretest sample. The results of the first pretest were analyzed and the questionnaire was adjusted. This was followed by a second pretest with 14 respondents to validate the adjusted questions. The questionnaire was found to be satisfactory once this was done.

Data were selected from major company databases to generate a representative sample with 1,000 addresses randomly chosen in each country. The Swiss Schober database was used for data collection in Switzerland and Liechtenstein. In Germany, the addresses were generated from the Hoppenstedt Company Database, whereas in Austria the Aurelia database was used. A total of 596 questionnaires were returned with 411 being fully completed. The response rate was 10.2 percent in Switzerland and Liechtenstein, 12.0 percent in Germany, and 18.9 percent in Austria. The SME definition of the European Commission (Citation2003) was used to distinguish SMEs (n = 339) from large companies (n = 72). A detailed overview of all sample statistics can be found in Table .

Table 1. Overview of Sample Characteristics

Measures

Social Network Usage

Social network usage was measured through two items: “Number of social networks used” (Michaelidou, Siamagka, and Christodoulides Citation2011) and “Frequency of usage” (Kaplan and Haenlein Citation2012). Frequency of usage ranged from “daily” to “weekly,” “monthly,” “quarterly,” “semi‐annually” to “yearly,” and also included a “never” category.

EO and RMO

The questionnaire from Rigtering et al. (Citation2014), which is based on Miller's (Citation1983) three main EO categories of innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk‐taking, was used to measure EO. For RMO, the scale consisting of seven items by Narver, Slater, and MacLachlan (Citation2004) was used.

Firm growth

Firm growth was assessed via the four subdimensions of growth in sales, profit, number of employees, and market share (following Chen et al. Citation2007). All items were assessed in relation to the competition. Statements regarding all three constructs (EO, RMO, and firm growth) were measured using a five‐point Likert scale ranging from “totally agree” to “totally disagree.”

Control Variables

Several control variables with regard to firm characteristics were used to assess representativeness of our dataset and the validity of our model. Control variables are (1) availability of monitoring mechanisms for measuring the effectiveness of social network usage, (2) industry affiliation (manufacturing or service), (3) customer type (B2B or B2C), and (4) family firm (family‐owned business or not).

Data Analysis

Data was analyzed in step 1 through descriptive measures to achieve an overview of social network usage in different firm types. In step 2, covariance‐based structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test our hypotheses developed for the SME context and to further explore differences to large enterprises. SEM appears to be an adequate analysis instrument for two main reasons. First, our hypotheses create a complex pattern of interrelationships among variables with multiple ways to affect each other. Second, the suggested variables EO, RMO, social network usage, and firm growth represent higher‐order constructs that cannot be captured with one single item and thus are subject to measurement error. For example, several survey items point toward risk orientation of the firm, and risk orientation itself is one element of the EO concept. In other words, we measure latent, unobserved variables with the help of observed survey items (Maruyama Citation1997). To control the measurement error and avoid method variance by applying related but different estimation methods, all hypotheses are tested within the SEM approach. In a third step, with regard to examining possible differences between SMEs and large firms in an explorative manner, we also apply two‐group SEM modeling (Byrne, Shavelson, & Muthén, Citation1989), linear regressions, and binary logit regressions.

Results

Descriptive Analysis

Our findings indicate that 62 percent of firms in the sample use social networking sites as a marketing tool. Twenty‐one percent of current non‐users plan to start using social networks in the next two years. A difference was found in the social network usage of SMEs and large firms: Only 58 percent of SMEs are active social network users, whereas 81 percent of all large firms use social networks for achieving their marketing objectives. Whereas only 19 percent of SME “non‐users” plan to employ social networks in the next two years, it is 35 percent for large firms. A comparison between B2B and B2C oriented firms shows that there is only a small difference in usage. Sixty percent of B2B firms are active social network users whereas 66 percent of all B2C firms use social networking technologies (Table ).

Table 2. Social Network Usage

The results indicate that most firms use more than just one social network. Facebook (77 percent) is the most used social network for marketing activities in the sample, followed by XING (69 percent). A difference could be identified regarding the social network usage in SMEs and large firms. Whereas Facebook is the most popular social network among SMEs (44 percent), the majority of large firms have a presence on XING (76 percent). Overall, it can be seen that every social network under consideration has a higher usage rate by large firms (Table ).

Table 3. Most Popular Social Networking Sites

The researched firms show different behaviors of communication on social networks. Most of them (42 percent) communicate messages on a weekly basis to their audience. Twenty‐four percent write messages or send pictures and videos every day, another 18 percent communicate on a monthly basis. In general, large firms tend to be more active on social networks than SMEs: 38 percent of them communicate everyday business‐related news (20 percent in SMEs). There are also some SMEs (5 percent) that have a social network presence although they never use their profile.

Reliability and Validity Checks

SEM using a maximum likelihood estimator was used to test our hypotheses (using lavaan 0.5–19 and related packages in R). We follow the paradigm by Gerbing and Anderson (Citation1988) to ensure construct validity of our latent variables before interpreting the relationships between them. More specifically, after an assessment of factorial structure by exploratory factor analysis (EFA), reliability is evaluated by Cronbach's α, followed by convergence and discriminant validity checks in a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) as suggested by Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981). CFA and SEM are applied as two‐group comparisons to account for the expected differences between SMEs and large enterprises.

EFA results indicate that all four latent variables load on one factor each. Consequently, reliability was sufficient for social network usage (α = 0.869), EO (α = 0.763), RMO (α = 0.701), and firm growth (α = 0.893). However, an initial CFA over both groups showed low loadings for the indicators “We freely communicate information about our successful and unsuccessful customer experiences across all business functions (RMO)” (0.484) and “I believe this business exists primarily to serve customers (RMO)” (0.440) as well as for “Last year we achieved a higher growth on number of employees than our (direct/indirect) competitors (firm growth)” (0.472). Further, a two‐group CFA demonstrates that the indicator “We constantly monitor our level of commitment and orientation to serving customer needs (RMO)” even underscores the threshold of 0.4 in the large enterprises group (0.322). For these reasons, we removed the respective indicators. Since all latent variables are supposed to be reflective, indicator removal is no danger to validity (Jarvis, MacKenzie, and Podsakoff Citation2003).

In a next step, convergent and discriminant validity are checked. Social network usage (AVESME = 0.694; AVELE = 0.701), EO (AVESME =0.524; AVELE = 0.501), and firm growth (AVESME = 0.810; AVELE = 0.601) fulfill the minimum threshold for convergent validity (AVE > 0.5). Due to the extensive deletions for RMO, the explained variance is estimated below that threshold (AVESME = 0.372; AVELE = 0.438). However, since substantial intercorrelations between the items and discriminant validity are given for all measures, we continue with all latent variables.

Table depicts the measured variables' factor loadings on the latent variables in the final two‐group CFA. Table illustrates the two‐group structural model. The model provided a reasonable to good fit with the data: χ2 = 171.322 (d.f. = 98), p < .001, CFI = 0.962, RMSEA =0.060. For these fit measures, CFI values above 0.95 indicate a good‐fitting model and RMSEA values below 0.08 indicate a reasonably good‐fitting model (Keith Citation2006). Further, measurement invariance tests show small albeit significant differences in loadings (Δχ2 = 19.366 with Δdf = 8 and p < .05), intercepts (Δχ2 = 38.946 with Δdf = 8 and p < .001), and means (Δχ2 = 33.229 with Δdf = 4 and p < .001). Marginal differences in fit measures (loadings: ΔCFI = 0.006, ΔRMSEA = 0.002; intercepts: ΔCFI = 0.016, ΔRMSEA = 0.008; loadings: ΔCFI = 0.015, ΔRMSEA = 0.007) confirm this assumption and lead to the conclusion that partial invariance is achieved. Hence, we continue with the comparison of the structural coefficients.

Table 4. Measured Variables' Factor Loadings on Latent Variables (CFA)

Table 5. Empirical SEM Results

Hypotheses Tests

First, with regard to the relationship of EO and RMO to social network usage, results indicate that SMEs' social network usage is significantly improved by EO (β = 0.421, p < .001), but not by RMO (β = −0.154, p > .05). With this being the case, for the SME context, we find support for H1, but not for H2. In addition, our two‐group model indicates important results, with the Z test being used for differences in the structural estimates (Gonzalez and Griffin Citation2001). Specifically, large enterprises that intensively use social networks are not significantly driven by EO (β = 0.151, p > 0.05), but by RMO (β = 0.221, p < .01).

Second, with regard to firm growth, results indicate that SMEs cannot improve their growth levels via a more intensive usage of social networks alone since the effect is not significant (β = −0.086, p > .05). That is, H3 is not supported in the SME context. In turn, large enterprises possess this option owing to the effect's significance (β = 0.303, p < .01).

Third, we find that that the direct effect of EO and RMO on firm growth is confirmed for SMEs (EO: β = 0.240; RMO: β = 0.237; both: p < .05), providing support for H4 and H5. Due to the small sample size, both direct effects are insignificant in the large enterprise group (EO: β = 0.221; RMO: β = 0.303, both: p > .05). However, difference tests and the comparative strength of the relationship across both groups indicate that there are no meaningful differences between SMEs and large firms.

Since the effect of EO and RMO on firm growth might be mediated via social network usage, an exploratory mediation analysis is conducted to shed light on the relationships among the latent variables. We thereby applied the two‐group SEM approach of mediation analysis (Iacobucci, Saldanha, and Deng Citation2007). For SMEs, this analysis shows a mediation of EO via social network usage (direct effect: β = 0.368, p < .01; indirect effect: β = 0.450, p < .05; total effect: β = 0.404, p < .05), but none of RMO through social network usage (direct effect: β = 0.396, p < .01; indirect effect: β = −0.192, p > .05; total effect: β = −0.238, p > .05). No mediation was found in the large firm group (EO—direct effect: β = 0.402, p > .05; indirect effect: β = 0.149, p > .05; total effect: β = 0.359, p > .05; RMO—direct effect: β = 0.501, p < .05; indirect effect: β = −0.422, p > .05; total effect: β = −0.211, p > .05). The mediation effects remained constant applying a bootstrapping approach (Zhao, Lynch, and Chen Citation2010).

Moderators Affecting the Relationship between Social Network Usage and Firm Growth

In order to shed additional light on the link between social network usage and firm growth, we tested the respective relationships in SMEs and large enterprise models for moderating effects. However, since multiples of the moderators are dichotomous, applying multiple group SEM with those moderators would further split the sample size and result in insufficient power. This is why we switched to a regression approach of z‐standardized factor scores on each single factor of EO, RMO, social network usage and firm growth. Table summarizes significant moderators.

Table 6. Important Moderation Effects

Firms that measure their social network usage's effectiveness showed differences compared to firms that do not use monitoring tools. On the one hand, SMEs could improve their effect of EO on social network usage by measuring its effectiveness (measuring: b = 0.229, p < .05; no measuring = 0.074, p > .05). On the other hand, large firms that measured their social networking efforts showed a significantly higher effect of social network usage on firm growth (b = 0.660, p < .05) than large firms that did not measure their efforts (b = 0.156, p > .05). Further, not measuring social networking efforts allowed a significant effect of RMO on firm growth for SMEs (b = 0.353, p < .001) as well as for large firms (b = 0.492, p < .05). Other differences remained insignificant. These findings draw the overall conclusion that measuring social networking efforts improves the impact of EO on social network usage for SMEs, but dilutes the impact of RMO on firm growth.

Operating in service versus manufacturing industries also helps to differentiate SMEs' and large firms' antecedents and consequences of social network usage. In predicting social network usage, EO is significantly important for service (b = 0.343, p < .001), but not for manufacturing SMEs, whereas the effect of RMO on social network usage is inversed for SMEs (service: b = −0.151, p < .05; manufacturing: b = 0.190, p > .05). The effect of EO on firm growth is only significant for service industry SMEs (b = 0.246, p < .001), not for manufacturing SMEs or large enterprises. Furthermore, the relationship between RMO and firm growth is more important for manufacturing (b = 0.508, p < .001) than for service SMEs (b = 0.152, p < .05). In contrast, social network usage is only important for large firm growth in manufacturing industries (b = 0.554, p < .05). Again, no other systematic differences were found. With respect to SMEs, it appears that EO is advantageous in service industries, both with regard to social network usage and firm growth, whereas RMO is disadvantageous for social network usage. In turn, for manufacturing SMEs RMO unfolds a stronger growth effect.

Finally, customer type differentiation in terms of B2B versus B2C contexts showed some differences. While SMEs share a comparable pattern for firm growth predictors in both segments, large enterprises are significantly different in the effects of EO (B2B: b = 0.411, p < .05; B2C: b = 0.087, p > .05) and social network usage on firm growth (B2B: b = 0.316, p < .05; B2C: b = 406, p > .05). For SMEs, only the relationship between EO and social network usage is higher for B2B (b = 0.345, p < .001) than for B2C contexts (b = 0.238, p < .05). No further differences were present. EO has an evidently larger effect on SMEs' social network usage in B2B than in B2C environments.

Differences in SMEs' Social Network Usage

The linear regressions have detailed the impact of the respective variables on usage and firm growth. In order to provide a further fine‐grained picture of social network technology usage in SMEs, we recoded frequency and usage patterns to a binary outcome of having implemented social networking technologies or not (1, 0). Thus, we switched to a binary logit regression (applying a GLM in R with a binary link function).

In order to take account of SMEs resource constraints, we added a measure of resource leveraging to the analysis, that is, “doing more with less” in terms of resources available to SMEs (Morris, Schindehutte, and LaForge Citation2002, p.7), being measured via four items: “In our business we use relationships to friends, business partners, etc. to gain cheap access to information and advice,” “In our business we consistently try something new to be able to operate particularly economically,” “We arrange with other enterprises for recommending each other to save marketing costs,” “We use relationships to other enterprises to be able to offer a wider product range more cheaply” (Morris, Schindehutte, and LaForge Citation2002). All four items do not represent one single dimension, but form a multi‐faceted, but still common factor of resource leveraging. Consequently, an omega model (Zinbarg et al. Citation2006) is more appropriate and the four items represented a general factor quite well (total omega coefficient, comparable to the Cronbach's α margins = 0.79 with all items loading significantly on that general factor). A composite score using the general factor loadings as weights to represent resource leveraging was applied. Finally, we introduced a log‐transformed variable of the actual number of employees to control for firm size effects and differentiated between family and non‐family firms in addition to the aforementioned moderating variables.

The binary model showed important differences in social network usage for SMEs. SMEs are more likely to use social networks, if they are not family‐owned (β = −0.633, p < .05, Odds Ratio [OR] = 0.531), service industry‐embedded (β = 0.620, p < .05, OR = 1.859), and strong at leveraging resources (β = 0.146, p < .05, OR = 1.158). Moreover, we explored the types of social networks that SMEs use. To do so, we recoded social networks in B2C‐focused social networks (Facebook, Google+, MySpace, and Twitter) and B2B‐focused social networks (XING and LinkedIn). SMEs are more likely to use B2B social networks, if their primary clients are business customers (B2B, β = 0.903, p < .001, OR = 2.466) and if they are strong at resource leveraging (β = 0.240, p < .01, OR = 1.271). In contrast, B2C‐focused social network technology usage is more likely for non‐family SMEs (β = −0.640, p < .05, OR = 0.527) and SMEs focusing on B2C environments (β = −0.551, p < .05, OR = 0.576). The SME's number of employees had no effect in any of these models. Overall, SMEs seem to follow their customers into their preferred social networks.

Discussion

Contributions to Theory

This study investigated the antecedents and performance‐related consequences of information technology usage—more specifically the use of social networks—in SMEs. Our results confirm the hypothesized impact of EO on both social network usage and firm growth in SMEs. At the same time, RMO has the presumed positive influence on firm growth in SMEs, but, in contrast to our hypothesis, it does not impact social network usage in SMEs. Moreover, social network usage does not directly affect SME growth. Rather, the relationship between EO and SME growth is mediated by social network usage. It is interesting that this mediation effect carries through against the positive direct effect of EO on firm growth and the non‐effect of social network usage on firm growth. As a result, we see that social network usage as a managerial resource needs to be combined with entrepreneurial resources in the form of EO in order to unlock its growth potential. In other words, only when an SME possesses a strong EO so that social networks are used in a proactive, innovative, and risk‐oriented way, social networking technology use can lead to firm growth in SMEs. In contrast, if the SME possesses a moderate or even weak EO, the usage of social network technology itself does not drive firm performance.

Interestingly, all results regarding social network usage differ significantly between SMEs and large firms. Among large firms, RMO positively influences social network usage, whereas EO does not. We here also see an unmediated and therefore direct positive effect of social network usage on firm growth. These findings underscore that social network marketing indeed is effective in different ways for SMEs and large firms.

In this regard, our results suggest that research on antecedents and consequences of social network usage needs to take into account firm‐specific contingencies. When it comes to firm size, we see that measuring social network effectiveness improves the impact of EO on social network usage for SMEs. At the same time, it improves the effect of social network usage on large firm growth, whereas diluting the impact of RMO on firm growth for both SMEs and large firms at the same time. Moreover, industry seems to be a core contingency in the context of social network usage. It appears that service industry accounts for the positive effects between SMEs' EO and firm growth as well as between EO and social network usage. In turn, service SMEs with a strong RMO are less likely to use social networks. With regard to the manufacturing industry, only large firms appear to capitalize on social network technology use in terms of firm growth. For large firms, a B2B focus also creates a positive effect between social network usage and firm growth. In turn, a service focus in combination with smaller firm size brings the firm closer to its customers. This again might enable entrepreneurially oriented service SMEs to effectively use social networks as an information technology. At the same time, however, an SME's RMO is generally not associated with social network usage and even unfolds a negative effect among service SMEs. A possible explanation for this is that SMEs characterized by strong RMO give preference to personal customer contact (versus impersonal contact via social networks). These kinds of SMEs would omit social networks to maintain long‐term (offline) relationships.

According to Andzulis, Panagopoulos, and Rapp (Citation2012) and Kaplan and Haenlein (Citation2012), social networking success strongly depends on regular message updates. Our descriptive results indicate that large companies tend to use social network sites more frequently and are more active on social media platforms than SMEs. A reason for these differences can be seen in perceptual differences regarding the conditions of social network usage. Whereas 25.7 percent of SMEs that do not employ social networking tools agree with the statement that social network usage requires a large investment in terms of time, is this only the case for 9.7 percent of large firms (t = 2.95, p < .01). So there is a significant difference between SMEs and large firms when it comes to the belief that social network usage results in time well spent, or, as Nakara, Benmoussa, and Jaouen (Citation2012, p. 401) put it, “many SMEs do not make the most of these channels.” This is in line with our findings regarding differences in social network usage in SMEs. SMEs are more likely to use social networks for marketing purposes—the better the match between the specific social network employed (private or business networks) and its target customers (B2C versus B2B). The finding that resource leveraging also explains SMEs' technology usage can be seen as a further indication that entrepreneurial resources are critical for developing managerial resources in SMEs. Upon first glance, it seems obvious that the missing link between social network usage and firm growth in SMEs is caused by a lack of time, knowledge, and financial resources.

At the same time, we found an indirect performance effect of social network usage as a mediator between EO and firm growth in SMEs. Thus, the missing direct link between social network usage and firm growth in SMEs could be explained by SMEs' lack of entrepreneurial resources. If entrepreneurial resources are lacking, the firm fails to recognize new and innovative opportunities for using social networks in a way that contributes to firm growth. Only if the SME embraces innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk‐taking, social media technology use can lead to firm growth. On the other side, we see a direct positive effect of social network usage on growth among large firms. This effect is particularly caused by manufacturing firms in B2B industries. Although a positive effect of social network usage on firm performance in B2B settings was also found by other authors (Järvinen et al. Citation2012; Powell, Groves, and Dimos Citation2011), we believe that this finding warrants more research. The same applies to our result that measuring social networking efforts appears to dilute the effect of RMO in both the SME and large firm context.

Contributions to Managerial Practice

In terms of practical recommendations, we propose that SMEs strengthen their entrepreneurial resources for example by empowering their employees to develop social networking campaigns that are unique, relevant, and up‐to‐date (Geho, Smith, and Lewis Citation2010; Lacho and Marinello Citation2010; Pentina and Koh Citation2012). Contemporary social media management solutions such as Hootsuite(.com) or Klout(.com) can be of assistance in achieving this. Furthermore, among SMEs we see that EO has a positive impact on social media technology use, whereas RMO has no or even a negative effect when it comes to service industries. This means that SMEs that are mainly customer‐focused and want to use social networks should try to become more entrepreneurially oriented. This is of course easier said than done. However, efforts such as participative decision making, a reduction of organizational hierarchies, and the permission to use work time to develop creative projects have proven to increase employee creativity (Oldham and Cummings Citation1996; Zhang and Bartol Citation2010). Finally, in both the public and media there is often a preconceived notion that social network marketing is primarily used for B2C marketing purposes (Shih Citation2009). Nevertheless, our study shows that social networking is used by B2B and B2C firms alike. Further, B2B firms seem to account for the positive effect between social network usage and growth in large firms. Thus, B2B firms should consider putting more emphasis on using social media technology for their marketing purposes (see also Järvinen et al. Citation2012).

Contributions to Policy

By looking closer at firms that do not employ social networking tools, we see that SMEs are more uncertain about how the implementation of social media technology can help their firm. Whereas 18.6 percent of SMEs that do not employ social networking sites are unsure whether and how social network usage can help their company, is this only the case in 4.2 percent of large firms (t = 3.05, p < .01). Among the firms that employ social network technologies, we see that SMEs significantly agree more with the statement that social networks are unclear and not understandable (t = 2.05, p < .05). Furthermore, there is a significant difference between SMEs and large companies when it comes to the measurement of social networking efforts. Whereas 31.6 percent of SMEs monitor the outcomes of their social networking campaigns, is this the case in 53.4 percent of large firms (t = 3.07, p < .01), with monitoring, however, improving the impact of EO on social network usage for SMEs.

The main implication of these findings is that if the aim of policymakers is to support economic growth and competitiveness via entrepreneurially oriented SMEs, enhancing their usage of social network technology (e.g., through easy‐to‐grasp user manuals and workshops) would seem appropriate. This is in line with previous research that showed that a lack of training and management/technical support inhibits technology usage (Buehrer, Senecal, and Bolman Pullins Citation2005; Del Aguila‐Obra and Padilla‐Melendez Citation2006). Also, our findings highlight how different firm characteristics create distinctive barriers that prevent them from using social networks as marketing tool. Subsequently, understanding how internal barriers affect opportunity exploitation in the form of social network usage can assist policymakers in tailoring advice to help SMEs.

Limitations

As with any empirical investigation, our study is of course not without limitations. First of all, it was conducted in (German‐speaking) Western European countries. This issue could limit the ability to transfer our results to other parts of the world. Second, given very strict data privacy laws in the countries analyzed, the online questionnaire was sent out only once without any reminders. It is therefore possible that the results are biased toward more internet‐ and social media‐savvy respondents. However, since the descriptive results are consistent with other studies (Keel and Bernet Citation2013), we expect this effect to remain limited. Third, the number of returned questionnaires from SMEs was higher than the number of questionnaires returned from large companies. This actually reflects the real structure of the economy, even though a higher rate of returned questionnaires from large companies could have in fact enhanced data quality. Fourth, to reduce complexity and enlarge the generalizability of the results, the study treats SMEs and large firms as homogenous groups, so that statements regarding companies of particular sizes from different industries are limited. Fifth, our study offers avenues for firm growth of SMEs, using this as its dependent variable. Although (quantitative) growth being widely considered as the most important performance indicator, this view of course does not consider those firms that do not wish to grow—or grow rather “qualitatively.” Sixth, social network usage was measured through the number of social networks used and the frequency of usage. Therefore, it is a quantitative indicator and can of course not measure the quality of posts on social networks. Finally, a benefit of social media in their wider sense is the “passive” use of these—namely the collection of social media customer voices as a basis for marketing decisions. To foster customer relationship management as well as to enable product improvement, RMO approaches such as the systematic monitoring of social media in combination with the use of advanced analytics are recommended (Kaplan and Haenlein Citation2010). Given that we purposely tailored the study to the usage of social networking sites only, we might have missed out on these effects.

Conclusion

This study offered insights into social network usage as a special form of information technology, its outcomes, and antecedents in SMEs. Whereas only a few studies have investigated the impact of an SME's social network usage on marketing‐related outcomes, this study is the first to directly link social networking with SME growth. This study is also the first large‐scale empirical investigation to analyze EO and RMO in the context of social network usage in SMEs. By comparing the results to large firms, we pointed out differences in social network usage that can be attributed to firm size.

This study predominantly contributes to the growing academic literature on marketing and information technology usage in SMEs, social media marketing, as well as strategic orientations. In addition, our study provides a first indication that social network usage has—with EO as an antecedent—consequences for SME growth and therefore that such concepts should be included in theories of small firm performance. By conceptualizing EO as an entrepreneurial resource and social network usage as a managerial resource, we also contribute to the discussion on the effectiveness of exploration and exploitation in SMEs, confirming that ambidexterity is required to unlock social networking sites' growth potential (He and Wong Citation2004). In this regard, prior research shows that information technology usage does not only create firm growth, but that growth itself demands information technology usage (Bruque and Moyano Citation2007; Nguyen, Newby, and Macaulay Citation2015).

This paper has also created new research questions that should be addressed in the future. Here, (1) the impact of RMO on social network usage, (2) the impact of customer type and industry on the link between social network usage and firm growth, (3) resource availability as an antecedent of social network usage, and (4) the interplay between technology usage and firm growth show themselves to be of particular interest.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Fabian Eggers

Fabian Eggers is Associate Professor of Marketing, Menlo College.

Isabella Hatak

Isabella Hatak is Associate Professor of Strategic Entrepreneurship at Netherlands Institute for Knowledge‐Intensive Entrepreneurship (NIKOS), Universiteit Twente.

Sascha Kraus

Sascha Kraus is Chaired Professor of Strategic Management and Entrepreneurship, Universitat Liechtenstein.

Thomas Niemand

Thomas Niemand is Associate Researcher at Chair of Strategic Management and Entrepreneurship, Universitat Liechtenstein.

References

- Alpkan, L., C. Yilmaz, and N. Kaya (2007). “Market Orientation and Planning Flexibility in SMEs Performance Implications and an Empirical Investigation,” International Small Business Journal 25(2), 152–172.

- Anderson, B. S., and Y. Eshima (2013). “The Influence of Firm Age and Intangible Resources on the Relationship between Entrepreneurial Orientation and Firm Growth among Japanese SMEs,” Journal of Business Venturing 28(3), 413–429.

- Andzulis, J. M., N. G. Panagopoulos, and A. Rapp (2012). “A Review of Social Media and Implications for the Sales Process,” Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management 32(3), 305–316.

- Aquino, J. (2012). “Find the Right Social Media Monitoring Tool,” CRM Magazine 16(6), 33–37.

- Aral, S., C. Dellarocas, and D. Godes (2013). “Social Media and Business Transformation: A Framework for Research,” Information Systems Research 24(1), 3–13.

- Arman, S. M. (2014). “Integrated Model of Social Media and Customer Relationship Management: A Literature Review,” International Journal of Information, Business and Management 6(3), 118–131.

- Arnone, L., O. Colot, M. Croquet, A. Geerts, and L. Pozniak (2010). “Company Managed Virtual Communities in Global Brand Strategy,” Global Journal of Business Research 4(2), 76–112.

- Baker, W. E., and J. M. Sinkula (2009). “The Complementary Effects of Market Orientation and Entrepreneurial Orientation on Profitability in Small Businesses,” Journal of Small Business Management 47(4), 443–464.

- Barnes, N. G., A. M. Lescault, and G. Holmes (2015). http://www.umassd.edu/cmr/socialmediaresearch/2015fortune500/ (accessed October 21, 2013).

- Bharadwaj, P. N., and R. G. Soni (2007). “E‐Commerce Usage and Perception of E‐Commerce Issues among Small Firms: Results and Implications from an Empirical Study,” Journal of Small Business Management 45(4), 501–521.

- Boyd, H. W., R. Westfal, and S. F. Stasch (1977). Marketing Research‐Text and Cases. Homewood, IL: Richard D. Irwin.

- Braojos‐gomez, J., J. Benitez‐amado, and F. J. Llorens‐montes (2015). “How Do Small Firms Learn to Develop a Social Media Competence?,” International Journal of Information Management 35(4), 443–458.

- Brislin, R. W. (1980). “Translation and Content Analysis of Oral and Written Materials,” in Handbook of Cross‐Cultural Psychology. Eds. H. C. Triandis and J. W. Berry. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 389–444.

- Bruque, S., and J. Moyano (2007). “Organisational Determinants of Information Technology Adoption and Implementation in SMEs: The Case of Family and Cooperative Firms,” Technovation 27(5), 241–253.

- Buehrer, R. E., S. Senecal, and E. Bolman pullins (2005). “Sales Force Technology Usage—Reasons, Barriers, and Support: An Exploratory Investigation,” Industrial Marketing Management 34(4), 389–398.

- Bulearca, M., and S. Bulearca (2010). “Twitter: A Viable Marketing Tool for SMEs,” Global Business and Management Research: An International Journal 2(4), 296–309.

- Byrne, B. M., R. J. Shavelson, and B. Muthén (1989). “Testing for the Equivalence of Factor Covariance and Mean Structures: The Issue of Partial Measurement Invariance,” Psychological Bulletin 105(3), 456–466.

- Caldeira, M. M., and J. M. Ward (2002). “Understanding the Successful Adoption and Use of IS/IT in SMEs: An Explanation from Portuguese Manufacturing Industries,” Information Systems Journal 12, 121–151.

- Carim, L., and C. Warwick (2013). “Use of Social Media for Corporate Communications by Research‐Funding Organisations in the UK,” Public Relations Review 39(5), 521–525.

- Carter, M. (2011). http://econsultancy.com/uk/nma-archive (accessed October 22, 2013).

- Carton, R. B., and C. W. Hofer (2006). Measuring Organizational Performance—Metrics for Entrepreneurship and Strategic Management Research. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Castronovo, C., and L. Huang (2012). “Social Media in an Alternative Marketing Communication Model,” Journal of Marketing Development and Competitiveness 6(1), 117–134.

- Chen, C.‐N., L.‐C. Tzeng, W.‐M. Ou, and K.‐T. Chang (2007). “The Relationship among Social Capital, Entrepreneurial Orientation, Organizational Resources and Entrepreneurial Performance for New Ventures,” Contemporary Management Research 3(3), 213–232.

- Christodoulides, G. (2009). “Branding in the Post‐Internet Era,” Marketing Theory 9(1), 141–144.

- Chua, A. P. H., K. R. Deans, and C. M. Parker (2009). “Exploring the Types of SMEs Which Could Use Blogs as a Marketing Tool: A Proposed Future Research Agenda,” Australasian Journal of Information Systems 16(1), 117–136.

- Colliander, J., and M. Dahlen (2011). “Following the Fashionable Friend: The Power of Social Media‐Weighing Publicity Effectiveness of Blogs versus Online Magazines,” Journal of Advertising Research 51(1), 313–320.

- European Commission (2003). SME Definition: Commission Recommendation of 06 May 2003. Brussels: EU Commission.

- Constantinides, E., and S. J. Fountain (2008). “Web 2.0: Conceptual Foundations and Marketing Issues,” Journal of Direct, Data and Digital Marketing Practice 9(3), 231–244.

- Coulter, K. S., and A. Roggeveen (2012). “Like It or Not”: Consumer Responses to Word‐of‐Mouth Communication in on‐Line Social Networks,” Management Research Review 35(9), 878–899.

- Covin, J. G., and D. P. Slevin (1989). “Strategic Management of Small Firms in Hostile and Benign Environments,” Strategic Management Journal 10(1), 75–87.

- Covin, J. G., K. M. Green, and D. P. Slevin (2006). “Strategic Process Effects on the Entrepreneurial Orientation‐Sales Growth Rate Relationship,” Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice 30(1), 57–81.

- Covin, J. G., and D. P. Slevin (1991). “A Conceptual Model of Entrepreneurship as Firm Behaviour,” Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice 16(1), 7–24.

- Del aguila‐obra, A. R., and A. Padilla‐melendez (2006). “Organizational Factors Affecting Internet Technology Adoption,” Internet Research 16(1), 94–110.

- Derham, R., P. Cragg, and S. Morrish (2011). http://aisel.aisnet.org/pacis2011/53 (accessed October 21, 2013).

- Du, H., and W. Jiang (2015). “Do Social Media Matter? Initial Empirical Evidence,” Journal of Information Systems 29(2), 51–70.

- Dyerson, R., R. Spinelli, and G. Harindranath (2016). “Revisiting It Readiness: An Approach for Small Firms,” Industrial Management & Data Systems 116(3), 546–563.

- Eggers, F., S. Kraus, M. Hughes, S. Laraway, and S. Snycerski (2013). “Implications of Customer and Entrepreneurial Orientations for SME Growth,” Management Decision 51(3), 524–546.

- Enders, A., H. Hungenberg, H.‐P. Denker, and S. Mauch (2008). “The Long Tail of Social Networking: Revenue Models of Social Networking Sites,” European Management Journal 26(3), 199–211.

- Ferbe, R., and P. J. Verdoorn (1962). Research Methods in Economics & Business. New York: Macmillan.

- Fillis, I., U. Johansson, and B. Wagner (2003). “A Conceptualisation of the Opportunities and Barriers to E‐Business Development in the Smaller Firm,” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 10(3), 336–344.

- Fischer, E., and A. R. Reuber (2011). “Social Interaction via New Social Media: (How) Can Interactions on Twitter Affect Effectual Thinking and Behavior?,” Journal of Business Venturing 26(1), 1–18.

- Fitzgerald, M., N. Kruschwitz, D. Bonnet, and M. Welch (2014). “Embracing Digital Technology: A New Strategic Imperative. Findings from the 2013 Digital Transformation Global Executive Study and Research Project by MIT Sloan Management Review & Capgemini Consulting,” Research Report 2013. MIT Sloan Management Review, 1–12.

- Fornell, C., and D. F. Larcker (1981). “Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error,” Journal of Marketing Research 18(1), 39–50.

- Gandhi, M., and A. Muruganantham (2015). “Potential Influencers Identification Using Multi‐Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) Methods,” Procedia Computer Science 57, 1179–1188.

- Gecti, F., and I. Dastan (2013). “The Impact of Social Media‐Focused Information & Communication Technologies on Business Performance via Mediating Mechanisms: An Exploratory Study on Communication and Advertising Agencies in Turkey,” International Journal of Business and Management 8(7), 106–115.

- Geho, P., S. Smith, and S. Lewis (2010). “Is Twitter a Viable Commercial Use Platform for Small Businesses? An Empirical Study Targeting Two Audiences in the Small Business Community,” The Entrepreneurial Executive 15, 73–85.

- Gensler, S., F. Völckner, Y. Liu‐thompkins, and C. Wiertz (2013). “Managing Brands in the Social Media Environment,” Journal of Interactive Marketing 27(4), 242–256.

- George, J., and P. Simon (2011). “Connecting with Customers,” Baylor Business Review 30(1), 22–25.

- Gerbing, D. W., and J. C. Anderson (1988). “An Updated Paradigm for Scale Development Incorporating Unidimensionality and Its Assessment,” Journal of Marketing Research 25(2), 186–192.

- Giannakis‐bompolis, C., and C. Boutsouki (2014). “Customer Relationship Management in the Era of Social Web and Social Customer: An Investigation of Customer Engagement in the Greek Retail Banking Sector,” Procedia ‐ Social and Behavioral Sciences 148, 67–78.

- Goffee, R., and R. Scase (1995). Corporate Realities: The Dynamics of Large and Small Organisations. London: Routledge.

- Gonzalez, R., and D. Griffin (2001). “Testing Parameters in Structural Equation Modeling: Every ‘One’ Matters,” Psychological Methods 6(3), 258–269.

- Gummerus, J., V. Liljander, E. Weman, and M. Pihlstrom (2012). “Customer Engagement in a Facebook Brand Community,” Management Research Review 35(9), 857–877.

- Gummesson, E., C. Mele, F. Polese, E. Gummesson, and C. Grönroos (2012). “The Emergence of the New Service Marketing: Nordic School Perspectives,” Journal of Service Management 23(4), 479–497.

- Gupta, A. K., K. G. Smith, and C. E. Shalley (2006). “The Interplay between Exploration and Exploitation,” Academy of Management Journal 49(4), 693–706.

- Hakala, H. (2011). “Strategic Orientations in Management Literature: Three Approaches to Understanding the Interaction between Market, Technology, Entrepreneurial and Learning Orientations,” International Journal of Management Reviews 13(2), 199–217.

- Harrigan, P., G. Soutar, M. M. Choudhury, and M. Lowe (2015). “Modelling CRM in a Social Media Age,” Australasian Marketing Journal (AMJ) 23(1), 27–37.

- Harris, L., and A. Rae (2009). “Social Networks: The Future of Marketing for Small Business,” Journal of Business Strategy 30(5), 24–31.

- Harris, L., A. Rae, and S. Grewal (2008). “Out on the Pull: How Small Firms Are Making Themselves Sexy with New Online Promotion Techniques,” International Journal of Technology Marketing 3(2), 153–168.

- Hatak, I., T. Kautonen, M. Fink, and J. Kansikas (2016). “Innovativeness and Subsequent Family‐Firm Performance: The Moderating Effect of Family Commitment,” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 102, 120–131.

- He, Z. L., and P. K. Wong (2004). “Exploration Vs. Exploitation: An Empirical Test of the Ambidexterity Hypothesis,” Organization Science 15(4), 481–494.

- Hennig‐thurau, T., E. C. Malthouse, C. Friege, S. Gensler, L. Lobschat, A. Rangaswamy, and B. Skiera (2010). “The Impact of New Media on Customer Relationships,” Journal of Service Research 13(3), 311–330.

- Hoffman, D. L., and M. Fodor (2010). “Can You Measure the Roi of Your Social Media Marketing,” MIT Sloan Management Review 52(1), 41–49.

- Hoffman, D. L., and T. P. Novak (2012). “Toward a Deeper Understanding of Social Media,” Journal of Interactive Marketing 26(2), 69–70.

- Hothi, H., B. Saleena, and B. Prakash (2015). “Experiencing Company's Popularity and Finding Correlation between Companies in Various Countries Using Facebook's Insight Data,” Procedia Computer Science 50, 433–439.

- Hunt, S. D., R. D. Sparkman, Jr., and J. B. Wilcox (1982). “The Pretest in Survey Research: Issues and Preliminary Findings,” Journal of Marketing Research 19(2), 269–273.

- Hutton, G., and M. Fosdick (2011). “The Globalization of Social Media: Consumer Relationships with Brands Evolve in the Digital Space,” Journal of Advertising Research 51(4), 564–570.

- Iacobucci, D., N. Saldanha, and X. Deng (2007). “A Meditation on Mediation: Evidence That Structural Equations Models Perform Better than Regressions,” Journal of Consumer Psychology 17(2), 139–153.

- Ireland, R. D., M. A. Hitt, and D. G. Simon (2003). “A Model of Strategic Entrepreneurship: The Construct and Its Dimensions,” Journal of Management 29(6), 963–989.

- Jang, H.‐J., J. Sim, Y. Lee, and O. Kwon (2013). “Deep Sentiment Analysis: Mining the Causality between Personality‐Value‐Attitude for Analyzing Business Ads in Social Media,” Expert Systems with Applications 40(18), 7492–7503.

- Järvinen, J., A. Tollinen, H. Karjaluoto, and C. Jayawardhena (2012). “Digital and Social Media Marketing Usage in B2b Industrial Section,” The Marketing Management Journal 22(2), 102–117.

- Jarvis, C. B., S. B. Mackenzie, and P. M. Podsakoff (2003). “A Critical Review of Construct Indicators and Measurement Model Misspecification in Marketing and Consumer Research,” Journal of Consumer Research 30(2), 199–218.

- Jiang, G., P. R. Tadikamalla, J. Shang, and L. Zhao (2016). “Impacts of Knowledge on Online Brand Success: An Agent‐Based Model for Online Market Share Enhancement,” European Journal of Operational Research 248(3), 1093–1103.

- Jiang, S., H. Chen, J. F. Nunamaker, and D. Zimbra (2014). “Analyzing Firm‐Specific Social Media and Market: A Stakeholder‐Based Event Analysis Framework,” Decision Support Systems 67, 30–39.

- Johnston, D. A., M. Wade, and R. Mcclean (2007). “Does E‐Business Matter to SMEs? a Comparison of the Financial Impacts of Internet Business Solutions on European and North American SMEs,” Journal of Small Business Management 45(3), 354–361.

- Jussila, J. J., H. Kärkkäinen, and H. Aramo‐immonen (2014). “Social Media Utilization in Business‐to‐Business Relationships of Technology Industry Firms,” Computers in Human Behavior 30, 606–613.

- Kannabiran, G., and P. Dharmalingam (2012). “Enablers and Inhibitors of Advanced Information Technologies Adoption by SMEs,” Journal of Enterprise Information Management 25(2), 186–209.

- Kaplan, A. M., and M. Haenlein (2012). “The Britney Spears Universe: Social Media and Viral Marketing at Its Best,” Business Horizons 55(1), 27–31.

- Kaplan, A. M., and M. Haenlein. (2010). “Users of the World, Unite! the Challenges and Opportunities of Social Media,” Business Horizons 53(1), 59–68.

- Keel, G., and M. Bernet (2013). Social Media Wird Alltag: Integration Nimmt Zu: Bernet Zhaw Studie Social Media Schweiz 2013. Zürich, CH: Bernet PR AG & Züricher Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaften.

- Keith, T. Z. (2006). Multiple Regression and Beyond. Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

- Kesting, P., and F. Günzel‐jensen (2015). “SMEs and New Ventures Need Business Model Sophistication,” Business Horizons 58(3), 285–293.

- Kietzmann, J. H., K. Hermkens, I. P. Mccarthy, and B. S. Silvestre (2011). “Social Media? Get Serious! Understanding the Functional Building Blocks of Social Media,” Business Horizons 54(3), 241–251.

- Kim, W. G., H. Lim, and R. A. Brymer (2015). “The Effectiveness of Managing Social Media on Hotel Performance,” International Journal of Hospitality Management 44, 165–171.

- Kirchgeorg, M., B. Ermer, C. Brühe, and D. Hartmann (2009). Live Trends 2009/10: Live@Virtuell – Neue Formen Des Kundendialogs. Köln: Uniplan GmbH & Co. KG.

- Kohli, A. K., B. J. Jaworski, and A. Kumar (1993). “Markor ‐ A Measure of Market Orientation,” Journal of Marketing Research 30(4), 467–477.

- Kraus, S., J. P. C. Rigtering, M. Hughes, and V. Hosman (2012). “Entrepreneurial Orientation and the Business Performance of SMEs: A Quantitative Study from the Netherlands,” Review of Managerial Science 6(2), 161–182.

- Kudeshia, C., P. Sikdar, and A. Mittal (2016). “Spreading Love through Fan Page Liking: A Perspective on Small Scale Entrepreneurs,” Computers in Human Behavior 54, 257–270.

- Lacho, K. J., and C. Marinello (2010). “How Small Business Owners Can Use Social Networking to Promote Their Business,” The Entrepreneurial Executive 15, 127–133.

- Lau, R. Y. K., C. Li, and S. S. Y. Liao (2014). “Social Analytics: Learning Fuzzy Product Ontologies for Aspect‐Oriented Sentiment Analysis,” Decision Support Systems 65, 80–94.

- Lechner, C., M. Dowling, and I. Welpe (2006). “Firm Networks and Firm Development: The Role of the Relational Mix,” Journal of Business Venturing 21(4), 514–540.

- Lee, J., and J. Runge (2001). “Adoption of Information Technology in Small Business: Testing Drivers of Adoption for Entrepreneurs,” The Journal of Computer Information Systems 42(1), 44–57.

- Lee, S., and M. Cho (2011). “Social Media Use in a Mobile Broadband Environment: Examination of Determinants of Twitter and Facebook Use,” International Journal of Mobile Marketing 6(2), 71–87.

- Lipsman, A., G. Mudd, M. Rich, and S. Bruich (2012). “The Power of ‘Like’: How Brands Reach (and Influence) Fans through Social‐Media Marketing,” Journal of Advertising Research 52(1), 40.

- Livingstone, S. (2008). “Taking Risky Opportunities in Youthful Content Creation: Teenagers' Use of Social Networking Sites for Intimacy, Privacy and Self‐Expression,” New Media & Society 10(3), 393–411.

- Lumpkin, G. T., and G. G. Dess (1996). “Clarifying the Entrepreneurial Orientation Construct and Linking It to Performance,” Academy of Management Review 21(1), 135–172.

- Lyon, D. W., G. T. Lumpkin, and G. G. Dess (2000). “Enhancing Entrepreneurial Orientation Research: Operationalizing and Measuring a Key Strategic Decision Making Process,” Journal of Management 26(5), 1055–1085.

- Macpherson, A., and R. Holt (2007). “Knowledge, Learning and Small Firm Growth: A Systematic Review of the Evidence,” Research Policy 36(2), 172–192.