Abstract

Learning by observing the behaviors and choices of other (referent) firms is an important way for firms to augment their stock of knowledge. However, new ventures face unique challenges with vicarious learning. In particular, their referent firms may not be spatially close, which makes it difficult to collect and make sense of information. In a field study of 175 high‐technology new ventures, we examine and find that distance and the maturity of the legal environments of the observed firms, along with the moderating effect of the size of referent firms, can influence new ventures’ observation and processing of information. Such learning is reflected by the perceived speed of new ventures fulfilling ISO 9000 certification.

Introduction

The short histories of new ventures provide them with limited opportunities to accumulate the knowledge needed for sophisticated organizational processes (Posen and Chen Citation2013). For example, although learning by doing can be effective for gaining knowledge (Ying Citation1967), this effect is limited in size and scope for new ventures because of their limited histories and resources. Therefore, abundant studies found that when new ventures are founded based on unique and rich resources, knowledge, and experiences of founders, they are more likely to overcome liability of newness to survive and thrive (Fryges, Kohn, and Ullrich Citation2015; Kirchhoff, Newbert, and Walsh Citation2007; Walsh and Linton Citation2011; Walsh et al. Citation2005; West and Noel Citation2009). Yet still, such existing stock of knowledge, including founders’ industry‐specific and entrepreneurial experiences, is often insufficient to support the operations and management of many new ventures (Chrisman and McMullan Citation2004; West and Noel Citation2009).

Existing studies suggest that when and where knowledge deficiencies exist, firms of different sizes and ages tend to learn by observing the behaviors and outcomes of other firms, or “referents,” particularly ones that are similar in size and age (Greve Citation1999; Haunschild and Miner Citation1997; Porac et al. Citation1995; Terlaak and Gong Citation2008). In this study, we particularly focus on new ventures’ learning from their chosen referents. Indeed, this type of vicarious (observational) organizational learning allows new ventures to mitigate their liability of newness (Stinchcombe Citation1965), bolster their knowledge base, and bridge the gap between their initially endowed knowledge and needed knowledge (Baum and Ingram Citation1998; Lowik et al. Citation2012; Miner and Haunschild Citation1995).

Despite the potential benefits attributed to learning from similar firms (Krugman Citation1991; Saxenian Citation1994), new ventures, particularly those in new and emerging high‐technology industries, may face unique challenges. One such challenge is finding learning referentsFootnote15 in nearby geographic regions. Given the weak normative forces (e.g., the absence of dominant designs or standards) that often exist in the early and growth‐stages of an industry's life cycle (Agarwal and Bayus Citation2004), firms tend to differentiate themselves along unique dimensions and thus occupy different market niches (Porac et al. Citation1995). Therefore, in such industries, geographic dispersion often exists among ventures that occupy similar market niches, leading to a shortage of “nearby” referents for new ventures that then need to search for a referent over a long distance.

However, organizational learning over distance is typically associated with obstacles. First, research in economics on regional “clustering” (Krugman Citation1991; Saxenian Citation1994) has found that knowledge spillovers resulting from agglomeration are heavily geographically constrained and can be exhausted outside of only a few miles (Kolympiris and Kalaitzandonakes Citation2013). Second, under certain circumstances, knowledge acquired from other markets was found to adversely affect a firm's performance in a focal market (Greve Citation1999; Ingram and Baum Citation1997; Sanders and Carpenter Citation1998; Tushman and Nadler Citation1978). The possibility of such negative out‐of‐market experiences raises the question of whether new ventures can, in fact, learn from referents located in different environments. Therefore, it remains unclear as to (1) whether new ventures are actually able to find referents over long distances, if so, (2) whether the distance poses a strong obstacle to the learning process, and (3) whether contextual factors associated with the chosen referent firms influence the effectiveness of such learning.

Existing studies on learning across distance in established firms provide little direction in understanding these questions. Specifically, learning through observation involves two cognitive aspects: information observation and subsequent processing of such information. Thus effective learning occurs when information can be both observed and sufficiently processed. Many vicarious learning studies, however, equate effective learning to only its observational aspect (particularly the observation and collection of hard, explicit information) but leave the knowledge processing and assimilation aspects largely unaddressed. For example, in their study of Manhattan hotels, Baum and Ingram (Citation1998) assumed that observations made during visits to rivals’ hotels were easy and adequate to facilitate effective learning. In addition, work on agglomeration effects (Krugman Citation1991; Saxenian Citation1994) has focused on the average performance of groups of firms (and almost exclusively established firms), which makes it difficult to tease out the generative mechanisms through which geographic proximity works to improve firm performance. Therefore, the field's understanding of the mechanisms in effective learning across geographic distance remains unarticulated and relatively superficial.

To address this gap in our understanding of how new ventures learn, we adopt an empirical context involving the implementation of ISO 9000 quality assurance management systems among high‐technology new ventures in an industrial district in China. We use ISO 9000 certification as a context and the perceived speed of fulfilling ISO 9000 requirements as a proxy for new venture learning effectiveness for two reasons. First, ISO 9000 certification has been increasingly acquiring a “rule‐like status” for firms, and particularly high‐technology ventures (Hu and Bai Citation2009). Virtually all technology ventures are trying to get this certification as quickly as possible yet the process‐oriented approach of ISO 9000 requires firms to design, choose, and install routines and processes that best suit their specific circumstances (Stankard Citation2002). Therefore, the perceived speed to certification is largely determined by how well a firm learns to design, install, and coordinate its operational routines and processes and could serve as a strong proxy for its learning effectiveness. Second, the conceptual and practical difficulties in directly measuring the occurrence of a latent process such as organizational learning have made it a common practice to operationalize its occurrence through firms’ implementation of specific new technologies or standards (e.g., implementation of total quality management in Douglas and Judge Citation2001; or reduction in defect rates in Haunschild and Rhee Citation2004). We thus follow this tradition by using firm's perceived speed of fulfilling ISO 9000 requirements as a proxy for the occurrence and effectiveness of learning.

In this study, we develop and test two main lines of arguments. First, new ventures with geographically close referents are able to learn more effectively from these referents, which in turn will contribute to their faster perceived speed of fulfilling ISO 9000 requirements. Although studies find that agglomeration effects dissipate beyond a short distance (a few miles), we find that for new ventures the effects of learning from their carefully chosen referents can occur across much longer distances. Second, we argue new ventures tend to learn faster from referent firms located in mature legal institutional environments, and such maturity even reduces the negative effect of geographic distance on new venture learning. Furthermore, we argue that the size of the referent firms will also influence the relationship between distance and learning effectiveness.

Like many other empirical studies, our study may suffer from several deficiencies. For example, the cross‐sectional data used in the study do not allow us to conclusively infer the causal relationships proposed. The narrow geographic region of the sample firms leaves the generalizability of our results an unresolved issue, the solution of which requires future studies that include firms covering a broader range of geographic regions. However, our study still provides implications to the literature in theoretical development of organizational learning and agglomeration effects. First, our findings help to isolate a “micro‐foundation” of agglomeration effects by revealing the effect of how a new venture chooses its referent on the effectiveness of its learning, thereby providing a more complete and nuanced understanding of the boundary conditions of such learning in new ventures. Second, these findings highlight a long‐ignored possibility that learning effectively from other firms across distance depends not only on observing the successes or failures of other firms, but also on inferential processes influenced by contextual factors (Terlaak and Gong Citation2008).

Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

The competency perspective (Hamel and Prahalad Citation1990) and the knowledge‐based view of the firm (Grant Citation1996) suggest that it is crucial for firms to develop difficult‐to‐imitate and socially complex, heterogeneous knowledge bases and capabilities, which are the major determinants of sustained competitive advantage. To develop such knowledge bases and capabilities, companies need to not only develop internal knowledge but also access knowledge elements from external sources because most innovations and competency building result from borrowing rather than from internally‐focused inventions (March and Simon Citation1958). Following these perspectives, the extant literatures on technological learning, management of technology, and high‐technology entrepreneurship have accumulated abundant studies on the importance of technological firms’ learning capabilities, particularly the capabilities to absorb relevant knowledge from external sources (e.g., absorptive capacity), to the effectiveness of organizational learning and firm performance (e.g., Harms Citation2015; Lanza and Passarelli Citation2014; Linton and Walsh Citation2004; Maes and Sels Citation2014). However, these research streams have often neglected the heterogeneity of external entities, such as referent firms, from which firms learn and thus paid insufficient attention to whether and how the characteristics of these external entities influence firm learning. A few studies in management of technology has examined how the technological, social, and cognitive proximity between focal firms and their knowledge sources, often referent firms, influence technological learning (Presutti, Boari, and Majocchi Citation2011; vom Stein and Sick Citation2014). Yet these studies have not investigated the potential effects of the geographic proximity between focal firms and their referent firms, as an external source of knowledge, on the effectiveness of technological learning.

To address this insufficiently tapped issue about geographic proximity, studies in geographic strategy and the economics of agglomeration provide certain clues. These literatures indicate that the spatial proximity between a firm and its stakeholders (Peteraf and Shanley Citation1997) and regional agglomeration (Dudley Citation1990; Krugman Citation1991) can yield benefits to firms through knowledge spillovers. In contrast, geographic distance can exert a bounding effect on such spillovers because the ability to implement lessons learned from outside a firm's local market is contingent on the degree of similarity between different markets (Greve Citation1999; Kolympiris and Kalaitzandonakes Citation2013; March, Sproull, and Tamuz Citation1991; Sanders and Carpenter Citation1998; Tushman and Nadler Citation1978). For this reason, research on geographic strategy, agglomeration effects, and vicarious learning tend to examine firms and their referents within very narrow geographic regions (Baum and Haveman Citation1997; Kim and Miner Citation2007; Posen and Chen Citation2013). For example, Baum and Haveman (Citation1997) studied hotels located in the same borough (Manhattan) that were able to observe the behavioral choices and outcomes of one another. Other studies have adopted a similar focus on learning through close observation (Haunschild Citation1993; Haunschild and Miner Citation1997; Srinivasan, Haunschild, and Grewal Citation2007; Terlaak and Gong Citation2008).

New ventures, particularly those in emerging industries, face unique challenges. One challenge is a knowledge disadvantage vis‐à‐vis firms already operating in the industry. Therefore, a common response is to obtain and apply knowledge through mimetic isomorphism or other observational learning mechanisms (Zaheer Citation1995). The ventures can be especially dependent on referent firms in making sense of and adapting to their environments. Indeed, work on vicarious learning indicates that firms can learn by observing the innovations, routines, designs, and positive or negative outcomes of other firms, and then adopting associated practices (Baum and Ingram Citation1998; Gittelman and Kogut Citation2003; Haunschild Citation1993; Haunschild and Miner Citation1997; Kim and Miner Citation2007). Yet as argued, new ventures face significant obstacles in finding relevant referent firms within close proximity. Therefore, they often need to make a trade‐off between referents in a wider geographic area and those that are geographically close but dissimilar on key organizational dimensions. Moreover, unlike hotels or banks, whose competition is limited to a narrow location, new ventures in new and emerging high‐technology industries often compete at the national or even global levels (“born global” firms in Rennie Citation1993). The unique circumstances facing such ventures provide, and indeed often require, learning from firms that can be very geographically distant.

The geographic strategy literature indicates that, despite recent advances in communication technology that help firms collect information (Sorenson and Baum Citation2003), distance can still create severe information constraints that contribute to biases in decision making (Golledge and Stimson Citation1997). These biases are especially apparent when firms attempt to access information in new and dynamic environments or when they suffer from insufficient resources (Golledge and Stimson Citation1997), both of which are hallmarks of the conditions faced by new firms. Thus, as we argue in the next section, the geographic position and institutional characteristics of a chosen referent firm may influence the effectiveness of an observing new venture's learning from the referent.

Geographic Distance

The characteristics of collected information can have implications for new ventures’ ability to observe and process information from referent firms. Landier, Nair, and Wulf (Citation2009) classified information collected for business decisions into two categories: “hard” and “soft.” Hard information, which is akin to explicit knowledge, is often quantifiable and not context‐specific and thus easy to collect, store, and transmit across long distances. Hard information that could be collected from a referent firm includes both its routines, processes, and other observable practices, and measures of its financial performance, age, size, and conspicuous strategic and competitive actions. In contrast, soft information can include a referent firm's vision, motivations, goals, expectations, organizational culture, and team dynamics. Resembling tacit knowledge (Polanyi Citation1958), soft information is often context‐specific, difficult or impossible to quantify and collect, and can become distorted with distance.

Reduction in geographic distance between an observing new venture and its referent can facilitate information collecting and processing, which in turn facilitates learning. First, geographic proximity facilitates collecting information, especially soft information that is context‐specific and tacit. Firms can directly monitor the behaviors, choices, or artifacts of close by referent firms through personal visits, observations, and physical interactions. New ventures can also acquire information about referent firms through employee mobility (Rosenkopf and Almeida Citation2003), board interlocks (Haunschild and Beckman Citation1998), and other social relations (Ingram and Roberts Citation2000).

Second, the processing of hard information, such as the absence or presence of specific routines in referent firms, can be improved with cues extracted from soft information collected. These cues provide reference points for connecting information to broader semantic networks and are “simple, familiar structures that are seeds from which people develop a larger sense of what may be occurring” (Weick Citation1995, p. 50). Such connections help to generate additional and deeper insights from hard information at hand (Roundy and Graebner Citation2013). Understanding the concerns, rationales, and motivations for the adoption or nonadoption of practices helps the observing firm make better decisions. Therefore, the existence of referent firms in close proximity facilitates the effective learning of a new venture.

However, outside of close proximity, communication difficulties (Cummings Citation2008) and the cost of seeking and acquiring knowledge (Borgatti and Cross Citation2003) increase significantly. These difficulties may increase the likelihood of new ventures relying on third‐party intermediaries such as consulting companies, investment banks, brokers, trade association meetings, or industry conferences (Chakrabarti and Mitchell Citation2013), or unobtrusive observations completed over long distance through newspapers, trade journals, or the Internet (Gittelman and Kogut Citation2003; Haunschild and Miner Citation1997). Despite the advances in information technology that help firms collect information in this way (Sorenson and Baum Citation2003), the use of secondary sources still increases the potential for inaccuracies, distortions, and biases in information. Furthermore, geographic distance reduces opportunities for directly observing soft information, making it harder to fully make sense of collected hard information.

Additionally, geographic distance can also embody differences in socioeconomic, regulatory, administrative, and cultural institutions (Boschma and Frenken Citation2006), which create further obstacles for effective learning. Specifically, increases in geographic distance correspond to increased potential for institutional differences and make it difficult for a new firm to apply the contextual, location‐specific knowledge to make sense of the observable choices and outcomes of its referent firm. This limits the firm's ability to process the observed information (Sanders and Carpenter Citation1998; Tushman and Nadler Citation1978). The institutional differences embodied in geographic distance also limit the applicability of knowledge acquired from referents (Sanders and Carpenter Citation1998; Tushman and Nadler Citation1978). Applying these arguments to learning from referents about fulfilling ISO 9000 requirements, we propose

H1: Among Chinese high‐technology new ventures, the geographic distance between a new venture and a referent firm is negatively associated with the effectiveness of the venture's learning from the referent for fulfilling the requirements of ISO 9000.

Maturity of Legal Institutions

In addition to distance, the effectiveness of both information observation and processing will, in turn, depend on contextual factors associated with the geographic locations of referent firms. A critical contextual factor, which we argue can influence the effectiveness of firms learning, is the maturity of legal institutions. The maturity of legal institutions represents the “Rule of Law,” or the creation and wide social acceptance of a permanent framework of laws within which productive activities are guided by individual decisions (Tamanaha Citation2004). The “Rule of Law” embodies a society's embracement of the legal principle that laws should govern a nation, as opposed to the arbitrary decisions of individuals or government officials (see Hayek Citation1994). In contrast, the lack of formal and regulatory frameworks—known as “institutional voids” (Peng and Heath Citation1996)—explain the pervasive use of relationship‐based business transactions in emerging economies (Li, Poppo, and Zhou Citation2008; Zhang and Li Citation2008). Research has proposed that the maturity of legal institutions prompt firms to move from relationship‐oriented strategies, based on entrepreneurs’ personal connections to governments and other stakeholders, to rule‐based strategies, featuring arm's length transactions (Hoskisson et al. Citation2005).

Systematic variations will exist in the maturity of legal systems in different geographic and administrative regions even within the same country (Pistor and Wellons Citation1999). This is particularly true in emerging economies such as China (Hasan, Wachtel, and Zhou Citation2009). We theorize that, the legal institutionalization of a referent's region (i.e., the extent of the “Rule of Law”) determines the clarity of the learning context and plays a critical role in facilitating new firms’ learning. Specifically, we suggest that new ventures can better learn from their referents, particularly through abductive reasoning, if these referents are located in regions with relatively mature legal institutions. Our reasoning is as follows.

Abductive reasoning proceeds from an observation to a hypothesis that could account for the observation, seeking to find the most parsimonious and likely explanation for the observation (Peirce Citation1883). The guiding principle of “inference to the best explanation” associated with abductive reasoning (Peirce Citation1883), fits the fact that people often favor plausibility over accuracy in accounts of events and contexts (Abolafia Citation2010). This also serves as an important property of information processing and sensemaking because “in an equivocal, postmodern world, infused with the politics of interpretation and conflicting interests and inhabited by people with multiple shifting identities, an obsession with accuracy seems fruitless, and not of much practical help, either” (Weick Citation1995, p. 61).

The nature of vicarious learning and the complexity of entrepreneurial processes may increase entrepreneurs’ tendency to use abductive inferential processes to learn from the observations of their most important referent firms.Footnote16 Free from the limitations of deductive and inductive reasoning, abductive reasoning will serve as a more practical and frequently used inferential method in learning from the observations of referent firms. For example, if there is wide social acceptance and strict enforcement of laws, there is less need for the prevalence of nepotism, cronyism, and other relationship‐based unobservable rules in governing and facilitating business transactions (Li, Poppo, and Zhou Citation2008; Zhang and Li Citation2008). In this case, upon observing that a referent firm adopts a specific practice to fulfill a certain purpose (i.e., fulfilling ISO 9000 requirements), the observing firm may have confidence in concluding that the adopted practice may be more transferrable to the context of its own, because such a practice may rely less on the referent's idiosyncratic relationships with various stakeholders. Therefore, everything else being equal, the new venture is more likely to face less complicated decision scenarios and make accurate and quick judgment about adopting the practices.

However, when laws are not strictly and impartially enforced, entrepreneurs will face more difficulties in determining the cause of actions. Upon seeing the adoption of a practice by the referent, such as that related to fulfilling ISO 9000 requirements, the observing firm will be less certain whether the practice is intrinsically legally accepted or is in fact legally problematic but with fewer (or no) costs given the lax law enforcement. More fundamentally, in such a legal environment, the observed success in implementing certain practices by a referent firm may largely rely on personal‐relationship‐based coordination among various internal and external stakeholders. Such coordination depends on the management of specific relationships among these stakeholders (Hoskisson et al. Citation2005), which is often invisible to third‐party observers. As a result, new ventures are more likely to make an incorrect inference and misattribute a referent's actions; that is, they may mis‐learn the information. Thus, consistent with the view that laws and market rules are instruments helping market participants correctly predict others’ behaviors (Hayek Citation1994), the maturity of legal institutions ensures that transactions are based on clear rules, which helps third parties infer more accurate information about the transactions. Based on the above reasoning, we hypothesize the following

H2: Among Chinese high‐technology new ventures, the maturity of the legal institutions of the regions where referents are located is positively associated with the effectiveness of new venture's learning from the referent for fulfilling the requirements of ISO 9000.

The Joint Effect of Geographic Distance and the Maturity of Legal Institutions

When the referent of a new venture operates in a locale with mature legal support, the effect of close geographic distance on the effectiveness of new venture learning will become particularly conspicuous. This effect occurs because, as argued, close geographic distance provides a new firm with more information, particularly soft information. Such context‐specific information, combined with wide social acceptance of and strict enforcement of laws and reduced reliance on social connections for transactions, helps disproportionately reduce the likelihood of alternative explanations for observed outcomes (Ross and Creyer Citation1992). This increased clarity allows a new firm to engage in more accurate inferring and judgment, which contributes to firm learning. In contrast, when legal institutions are underdeveloped, nepotism, cronyism, and other implicit rules are more ubiquitous in business transactions (Li, Poppo, and Zhou Citation2008; Zhang and Li Citation2008). With this inadequate functioning of market mechanisms, geographic proximity to a firm's referent may exert limited or even a negative impact on the effectiveness of the firm's learning process: the positive impact on learning from an increased abundance of information may not compensate for loss in learning because of increased intricacy and ambiguity in unobserved rules for business transactions and the increased volume of information. This situation can, in turn, create a null or even negative influence on the learning of new ventures. Based on the above reasoning, we thus propose

H3: Among Chinese high‐technology new ventures, the negative relationship between the geographic distance of a new venture and its referent and the effectiveness of learning from referents for fulfilling the requirements of ISO 9000 is reduced if the legal institutions where referents are located are more mature.

The Moderating Role of Referent Firm Size

In addition to the legal environments where a referent is located, characteristics associated with a referent firm itself may provide additional cues that improve the learning of new ventures. We theorize that the size of referent firms is one such characteristic.

Research on corporate finance has used various forms of “differential information availability” arguments to explain the long‐documented negative effect of firm size on stock returns (i.e., risk‐adjusted returns are a decreasing function of firm size; Atiase Citation1985). This argument suggests that the amount of unexpected information contained in an earnings announcement, which is inversely related to firm size, contributes to higher risk‐adjusted stock returns. Large firms are more visible to the public and must respond to greater demands for firm specific information due to greater incentives for information search by stakeholders. Such firms tend to attract greater interest from investors, financial analysts, and institutional investors, and thus have greater press coverage (Atiase Citation1985). By contrast, smaller firms, particularly private businesses, are less informationally transparent because they are often the sole verifiers of their information, are not required to release financial information, and have limited coverage by informed professional investors and analysts (Stein Citation2002). Thus large information asymmetries can exist between small firms and their external stakeholders (Dennis and Sharpe Citation2005; Hull and Pinches Citation1995).

Geographic Distance, Referent Firm Size, and Learning Effectiveness

Building on the above findings, we posit that if the most important referent of a new venture is large and in close geographic proximity to the venture, information advantages to the learning firm will be disproportionally larger. Not all the extra information observed from a large referent will necessarily be accurate nor make sense to the new venture without sufficient contextual information. But close geographic distance provides a new venture with abundant opportunities to find verifiers of the information for cross‐validation and to locate tacit and localized information that can facilitate the sensemaking of such information. These verifiers can be third‐party firms or individuals that have mutual connections with the observing new venture and its referent (e.g., mutual suppliers, service firms, distribution channels, buyers, or social relationship). In contrast, small firms are informationally opaque and have fewer connections with other firms that could serve as potential verifiers of information (e.g., Dennis and Sharpe Citation2005). Thus, the small size of a referent makes it difficult for a new venture to cross‐validate and make sense of observed information, even though the two firms might be closely located. The abundance of observable but invalidated information may even lead to increased errors in learning. Therefore, we propose

H4a: Among Chinese high‐technology new ventures, the negative relationship between the geographic distance of a new venture and its referent and the effectiveness of learning from the referent for fulfilling the requirements of ISO 9000 is reduced when the size of the referent is larger.

Maturity of Legal Institutions, Referent Firm Size, and Learning Effectiveness

As argued, a mature legal environment where referents are located will increase the confidence of the observing venture in inferring that practices adopted by the referents are more likely based on contracts rather than the referents’ idiosyncratic relationships with various stakeholders. Also, as argued, a larger referent will be more exposed to the public and thus provide opportunities for extra information to be observed. These two factors allow an observing venture to further eliminate alternative explanations and make better and quicker judgment about adopting practices. Therefore, we propose the following

H4b: Among Chinese high‐technology new ventures, the positive relationship between the maturity of the legal institutions of the regions where referents are located and the effectiveness of learning for fulfilling the requirements of ISO 9000 is enhanced when the size of the referent is larger.

Methods

Sample and Data Collection

To test our model, we collected both primary and secondary data. We first administered a surveyFootnote17 to new ventures located in a large, government‐sponsored high‐technology industrial district in the Yangtze River Delta, the most economically advanced region in China. This represents a particularly rich and appropriate context to test the proposed hypotheses for several reasons. First, the high‐technology industries have been rapidly emerging with the developed infrastructure in this region and the financial and policy support from both local and national governments. Second, the high‐tech new ventures in this region must learn from various sources because in these emerging industries (and in the region where they are located) there are often no prior or existing templates for firms to follow. Third, there is large variance in the maturity of legal institutions across nearby provinces. Finally, application for ISO 9000 certification, the focal issue of our study, has become almost a norm among high‐tech firms in China, particularly those that are located in the industrial district (Hu and Bai Citation2009). However, unlike those easily observable and implementable business practices (Davis Citation1991; Haunschild Citation1993; Haunschild and Beckman Citation1998), the nature of ISO 9000 systems still allows new ventures to retain discretion over choosing the most suitable practices to conform to the requirements (Stankard Citation2002).

We obtained the directory of firms in the industrial district from its administrative office. From the directory we then chose all the 215 new ventures that met two criteria. First, to reduce confounding factors associated with diversified firms, only nondiversified business units were included in our sample. Second, only firms with an operating history of more than one year but less than four years were chosen. This cutoff point was selected because firms with four years of history are considered new by most standards in the field of entrepreneurship (Hmieleski and Baron Citation2008); a one‐year lower bound was adopted because a very early‐stage venture with less than one year of history may not have a stable choice of referent firms. A prior survey conducted by the administrative office has indicated that almost all the firms in the district devoted some resources to the preparation of the application for the ISO 9000 certification.

Questionnaires were delivered in sealed envelopes to the CEO (lead entrepreneur) and at least one other member of the entrepreneurial team of each firm through the administrative office of the industrial district. In addition to answering items for other variables, survey respondents of each focal firm were asked whether, within two years of establishment (or since their establishment if they did not have two years of history), their firms had or have stable “referent firms” that meet two criteria. First, the behaviors, decisions, and outcomes of such firms have been observed and used as benchmarks, objects for making analogies, or in other ways to facilitate sensemaking of the industry and of market conditions and to provide guidance about the strategies and operations of the entrepreneur's venture. Second, these firms were referred to by entrepreneurial team members in at least half of the entrepreneurial team's discussions about company operations and strategies in the past year. The survey participants were then asked to list the estimated number of their referent firms that they considered to satisfy both of these criteria and provide the name, address, phone number, and other contact information of the referent firm that they deemed to be the most important (i.e., the firm to which they most frequently referred).

In total, 182 firms had at least two respondents complete the surveys, containing responses to the requests about referent firms. Each of the responding entrepreneurs unanimously answered that they had at least one such referent. None of them chose referents that did not belong to the general industry categories which their firms belonged to.Footnote18 There was significant agreement about the most important referent firms designated by lead entrepreneurs and other members of entrepreneurial teams (95 percent matching rate). Therefore, we used the referent firms designated by the lead entrepreneurs for the rest of the data collection. All these referent firms were then contacted (primarily through phone calls) and asked to provide or verify their addresses and information about the size of their firms.

Through a time‐consuming process, we collected and verified 175 pairs of focal and referent firms, which represented an 81 percent final response rate. To assess potential nonresponse bias, we used ANOVA to compare the focal firms in the final statistical analyses with those not included. No significant differences were found in firm size and age (Fsize = 0.61, p > .10; Fage = 0.82, p > .10, respectively). The focal firms in the final sample are from a variety of high‐tech industries, including new energy, electronics, biopharmaceuticals, telecommunications, computer software, environmental technologies, and advanced materials, etc. All these firms have designated referent firms that are dispersed in a wide‐spanning geographic area in China. Additionally, these chosen referents are located in the same industries or industries very close to those of new ventures and have longer histories (on average 6.3 years of existence) and larger firm size (on average 175 employees) than the designating new ventures. Fifty‐two new ventures have not obtained the certification and have been still engaging in the fulfilling process. Therefore, the firms in our study present an unbiased sample that includes both firms that have obtained certification and those that have not.

Measures

A New Venture's Geographic Distance to Its Chosen Referent Firm

After collecting the business addresses of the focal and referent firms, we used Google Map and Baidu Map to determine their latitudes and longitudes. When the specific locations of firms could not be found, we assigned the latitudes and longitudes of central places of areas matching the zip codes of the firms. With the latitude and longitude information of the firms, we calculated the geographic distance (Da.b) of a focal new firm (a) to a referent firm (b) by using the following formula (Sorenson and Audia Citation2000):

where lat and long refer to the latitude and longitude, respectively, of the focal firm (a) and the reference firm (b), and C (= 3,437) is a constant based on the radius of the sphere that converts the results into linear units so that they represent miles on the surface of the earth. The maximum, minimum, and average direct distance between focal and referent firms in the sample are 621, 34, and 163 miles, respectively, well beyond a several‐miles radius limit within which economies of agglomeration take place in mature industry clusters (Krugman Citation1991). In addition, 135 out of the total 175 sample firms have their referents located outside their home provinces. We then use the log value of Da.b in statistical analyses.

Maturity of Legal Institutions

Following Hasan, Wachtel, and Zhou (Citation2009) and Pistor and Wellons (Citation1999), we use the extent of the presence of legal professionals as a proxy for the maturity of legal institutions. Specifically, we measure the number of lawyers per 10,000 people in the province where a referent firm is located in the survey year. The data were collected from the Law Yearbook of China, the Chinese Yearbook of Lawyers, and the Statistics Yearbooks of each province for the year 2011, the year when most surveyed firms were founded. Additional information was collected from phones calls or visits to All China Lawyers Associations (ACLA) and the lawyers’ associations of the Chinese provinces covered in the study. The population data were obtained from the National Bureau of Statistics of China. We use lawyers as a percentage of the population as a measure for two reasons. First, studies have demonstrated that an increased presence of legal professionals in a province is indicative of both the maturity of legal institutions and the extent to which laws will be enforced (Hasan, Wachtel, and Zhou Citation2009). Second, as the presence of legal professionals increases, a general population becomes more familiar with the law and legal institutions; in contrast, the effectiveness of laws will suffer when new laws are enacted in a population unfamiliar with the underlying legal tradition (Pistor and Wellons Citation1999).

Size of Referent Firm

To measure firm size, we asked the contacted referent firms to indicate the numerical categories to which the average number of employees hired by the referent firm in the past three years belonged. In designing the categories, we consulted with entrepreneurs in similar industries for the upper and lower bounds of each of the six numerical categories, ranging from the lowest category (100–150 employees) to the highest category (above 500 employees).

Learning Effectiveness: Perceived Speed of ISO 9000 Implementation

Learning effectiveness was operationalized as the perceived implementation speed of ISO 9000 management systems. As previously mentioned, this choice is appropriate because the perceived speed with which firms fulfill the requirements of ISO 9000 management systems will largely depend on the effectiveness of their learning from various sources, including their chosen referents. The data for the perceived speed of ISO 9000 implementation were obtained from annual surveys conducted by the administrative office of the industrial district to gauge the fulfillment of ISO 9000 requirements. Survey questions were sent annually to firms reaching two years of establishment. To measure this variable, three 1–7 Likert scale items from existing studies on speed to market (Chen, Reilly, and Lynn Citation2005; Kessler and Chakrabarti Citation1999; Lynn, Skov, and Abel Citation1999) were adopted and modified to fit the context of ISO implementation.Footnote19 A pilot survey indicated that within two years after their establishment, firms located in the industrial district had at least accomplished certain requirements of ISO 9000 system. Therefore, items measuring perceived speed of implementation include “your fulfillment of ISO requirements in the first 2 years of firm establishment (or ever since establishment) was (or is) slower than, equal to, or faster than industry average,” “your fulfillment of ISO requirements in the first two years of firm establishment (or ever since establishment) was (or is) much slower than, as, or much faster than you expected,” and “your fulfillment of ISO requirements in the first two years of firm establishment (or ever since establishment) was (or is) far behind, fit (ted), or far ahead of your time goals.” This measure was adopted because it allowed entrepreneurs to compare their perceived fulfillment speeds with those of their same‐industry peers’ and thus captured certain confounding effects associated with industry affiliation. A possible alternative was to measure the time elapsed between the firm's establishment and its procurement of the ISO 9000 certification. However, this measure did not allow us to collect relevant data from those 52 firms that have not obtained the ISO 9000 certification by the time when the survey was conducted. Therefore, this measurement was abandoned.

Controls

We controlled for several confounding factors that may influence the speed of fulfilling ISO 9000 requirements. First, initial firm size (logarithmized number of employees at the end of the firm's first year of establishment) was controlled for. Large initial firm size suggests that there are more aspects of firm operations to cover for fulfilling ISO 9000 requirement and thus these large‐sized firms might need longer time to complete the fulfillment process. Second, increased firm size‐adjusted average annual expenditure on fulfilling ISO 9000 requirements (a 1 to 6 categorical variable) tends to expedite the fulfillment process and the variable was thus included as a control. Third, larger estimated number of referent firms and larger number of firms co‐located in the same general industry category (density) provide more useful information and knowledge about ISO 9000 requirement fulfillment to borrow, which increases the speed of ISO 9000 requirement fulfillment. Fourth, size and functional heterogeneity of entrepreneurial team (Blau's index; Blau Citation1977) and lead entrepreneur's prior entrepreneurial experience (dummy) all suggest the size or diversity of the new venture's internal knowledge sources that allows it to access, process, and assimilate knowledge from external sources (Maes and Sels Citation2014) and will also likely influence the ISO‐related learning. They were thus also included as controls. Finally, increased environmental dynamism will also influence the effectiveness of sensemaking of the firm about its environments (Covin and Slevin Citation1989). We thus included as a control environmental dynamism in the most recent three years using a six‐item instrument used and validated in previous research (Covin and Slevin Citation1989). This variable also captured much of the variance in the firms’ industry affiliations.

Results

Table contains the descriptive statistics and correlations of all variables used in the subsequent statistical tests. The independent and moderator variables were mean‐centered and then multiplied to create interaction terms (Aiken and West Citation1991). Multicollinearity is unlikely to be an issue because there are low to moderate correlations between variables and the scores for the variance inflation factors (VIFs) are all below the recommended threshold of 4. Table reports the results from hierarchical moderated ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions.Footnote20 Model 1 is the base model, including only control variables. Model 2 includes the geographic distance measure, the measure for the maturity of legal institutions, and the control variables. In addition to control and independent variables, Models 3–5 each include one interaction term. Model 6 is the full model with all interaction variables.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 2. Regression Results: Perceived Speed of Fulfilling ISO Requirements

As shown in Model 2, the coefficient for geographic distance is negative and significant (

geographic distance = −1.22, p < .001) and the coefficient for the maturity of legal institutions is positive and significant (

maturity of legal institutions = 1.08, p < .05). These results, respectively, support H1 and H2.

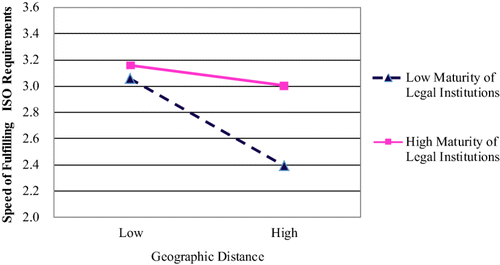

Regarding the moderation effects, first, consistent with what is predicted in H3, the coefficient for the interaction between the maturity of legal institutions and geographic distance is positive (

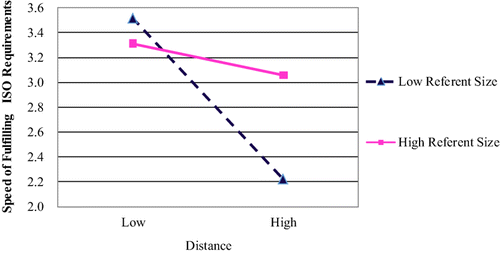

maturity of legal institutions × geographic distance = 4.88, p < .05 in Model 3). Figure 1 plots the moderating effect. As predicted, the relationship between geographic distance and learning effectiveness turns more negative when the legal institutions in chosen referent firms’ geographic regions are underdeveloped. Second, the coefficient for the interaction between geographic distance and referent size is positive and significant (

geographic distance × referent firm size = 9.86, p < .001 in Model 4), supporting H4a. Consistent with the hypothesis, the relationship between the geographic distance and learning effectiveness becomes more negative when the size of the referent firms is below average (see Figure 2). Finally, in Model 5, the coefficient for the interaction between the maturity of legal institutions and referent size is insignificant (

maturity of legal institutions × referent firm size = 2.00, n.s.). Therefore, we fail to find support for H4b.

Figure 1. The Moderating Effect of the Maturity of Legal Institutions [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Figure 2. The Moderating Effect of the Size of Referent Firm [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

To check the robustness of the findings, we removed the 40 new ventures whose referents were located in the same province and re‐calculated the regressions using the remaining 135 ventures. The results produced the same patterns of findings as in the full sample. Further, using the values of the geographic distance measure, we split the 175 observations equally into two groups and then ran the same regressions on the two subsamples. Again, we found the same patterns of outcomes as in the full sample.

Discussion

In addition to what has been revealed in the hypothesis testing, our study reveals another empirical pattern that was not predicted in the theory development part but is indicative of rich nuances in firms’ learning across distance and adoption of innovations and practices. Specifically, Figure 2 shows that having a nearby, small referent firm helps a new venture learn better than having a large referent firm with the same geographic proximity. This counterintuitive pattern suggests that two opposite mechanisms may simultaneously operate underlying the effect of referent firm size on a focal firm's learning effectiveness. On one hand, as suggested by the size effect in the previous literature (Hull and Pinches Citation1995), large firms provide more observation and thus learning opportunities for other firms. On the other hand, when considering the possibility of transplanting full or partial practices from large‐sized firms to satisfy ISO 9000 requirements, new ventures face the burden of collecting and processing additional information, particularly context‐specific soft information, from the referents to further examine the compatibility of these practices with their new contexts. Such a constraint may offset the positive effect of information abundance associated with a large firm size on learning effectiveness. The existence and functioning of such opposite forces may also provide clues to the null effect associated with H4a. Future research can address this issue by operationalizing these two forces and teasing out their effects from one another.

Implications for Theory and Practice

Our findings provide several implications for the literature in entrepreneurial learning and cognition, and geographic strategy. First, our findings contribute to the literature on entrepreneurial and organizational learning by revealing an important learning mechanism adopted by new ventures to reduce their liability of newness. Previous literature has focused on intra‐organizational learning that occurs at either the level of the individual entrepreneur or the organization (for references, see Wang and Chugh Citation2014). However, the likelihood and effectiveness of new ventures’ learning from the experiences of counterparts have rarely been examined. Furthermore, the unique context of emerging high‐technology industries makes it difficult for new firms to find similar learning targets in nearby and/or similar places, which will hinder knowledge spillovers because spillovers are strongly geographically bound (Kolympiris and Kalaitzandonakes Citation2013). Thus, with few exceptions (Srinivasan, Haunschild, and Grewal Citation2007), little is known about how the vicarious learning of new ventures in this phase of industry growth will differ from those that are located close to each other or that can easily observe each other in mature industries. Our study enriches the learning literature by finding that new ventures in early industry stages can actively learn from referents located beyond distances examined by traditional geographic strategy studies.Footnote21

Our findings also contribute to the entrepreneurial cognition literature by revealing the strong influence of contextual factors on the effectiveness of observing and processing information from referent firms, which is rarely examined. We found that both the maturity of legal institutions in the region where a referent is located and the size of the referent contribute (directly and/or indirectly) to the effectiveness of a new firm's ability to collect and make sense of information observed. In particular, at the societal level, identifying the maturity of legal institutions as an important facilitator for entrepreneurial learning provides evidence that the “Rule of Law” (Hayek Citation1994) not only provides benefits to parties directly involved in contractual arrangements but also learning benefits to observers not necessarily involved in such arrangements. Therefore, this finding contributes to institutional theory by revealing a micro‐mechanism through which institutions influence entrepreneurial learning, cognition, and outcomes.

Lastly, the results of our study also contribute to the strategy literature on firms’ geographic locations by exploring the effects of the geographic proximity of chosen referents and the characteristics associated with their institutional environments, which can embody various factors that improve or hinder the learning of the new venture. More generally, our findings also contribute to the clusters and aggregation economics literatures (Krugman Citation1991; Saxenian Citation1994) by identifying a generative rule through which co‐location with competitors improves the performance of new ventures. These literatures have mainly focused on the relationship between the density of firms in a narrow geographic region and their survival rates and performance (Chang and Park Citation2005; Singh and Marx Citation2013). However, by using population density measures at the industry level, this stream of research has failed to reveal specific mechanisms through which economies of aggregation take effects. The mechanism of geographic distances identified in our study provides implications for understanding the dynamics of population density in an industry and the effects of firm conglomeration in a specific location over time. Specifically, the positive learning implications of close geographic proximity can play a role in firms locating near one another until proximity reaches a certain point. After that point, the ease of learning is weighed against competitive pressures associated with close geographic proximity (Baum and Haveman Citation1997). Future research could adopt a longitudinal research design to track the changes in firm locations to examine whether there are aggregation and disaggregation tendencies among the firms in the same industry over time, and whether and how often firms change their major referents with changes in their locations.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite its contributions, this study is not without limitations, some of which suggest avenues for future research. First, following prior work on vicarious learning (Baum and Ingram Citation1998; Kim and Miner Citation2007; Miner and Haunschild Citation1995; Posen and Chen Citation2013; Srinivasan, Haunschild, and Grewal Citation2007), we inferred its occurrence in new ventures by assuming that the perceived speed of a new venture fulfilling ISO 9000 requirements reflects the net outcomes of learning from its referent. Similar to all studies that must rely on this method for capturing latent processes such as organizational learning and knowledge spillovers, this study can only infer the occurrence of learning from improvements in performance or adoption of observed practices rather than measuring them directly. Such approaches suffer from criticisms that they fail to reveal subtleties in learning processes (Argote Citation2013). Although we follow the approach of a long stream of research on organizational learning, our study is not exempt from these criticisms. Future research could develop more direct and fine‐tuned measures of learning that capture specific observational, sensemaking, or imitation mechanisms involved in new venture learning.

Second, our choice of a single proxy for the maturity of legal institutions may not capture the complete aspects of the construct. The maturity of legal institutions likely includes numerous components associated with the legal and regulatory systems. In addition to the number of legal professionals, which is the most commonly used measure of legal maturity (Hasan, Wachtel, and Zhou Citation2009), the maturity of legal institutions also relies on the social acceptance of fundamental laws and the values supporting the legal system, such as respect for property rights. Future research could use measures like the number of patent applications, patents, or property rights violations to operationalize other aspects of this construct.

Third, we examined the relationship between learning and the proximity of a new venture to its most important referent firm. However, it is likely that a new firm can compensate for loss in learning effectiveness due to such geographic distance by increasing its number of referent firms. Our data actually supported this. There is a positive correlation between the geographic distance measure and the number of referent firms that the lead entrepreneur stated they refer to in entrepreneurial team decisions (r = 0.22, p < .01). Examining the potential effect of a new firm's proximity to its group of major referents may allow researchers to capture more variance in the effectiveness of its vicarious learning.

Finally, our list of contextual factors that influence information observation and processing and that facilitate the vicarious learning is most likely incomplete. Aspects of economic development, or factors associated with cultural, administrative, and political institutions of different geographic regions (Ghemawat Citation2001; Presutti, Boari, and Majocchi Citation2011) might also improve (or hinder) new venture learning. In China, the setting of our study, these contextual factors vary significantly across regions because of large differences between neighboring provinces. When there is a perfect match between the contextual factors of contiguous regions and geographic distance (i.e., distance aligns with changes in various aspect of social institutions), our geographic distance variable will capture (or subsume) the variances in these contextual factors. However, even after controlling for geographic proximity, we have found that the maturity of legal institutions still exerts both direct and indirect influences on the vicarious learning, indicating the existence of misalignment between distance and the maturity of legal institutions. This could also be the case for other contextual variables. For example, Fagerberg and Srholec (Citation2008) identified several other factors that capture the cultural, societal, and institutional differences among different countries, such as the development of innovation system, the quality of governance, the character of the political system, and the degree of openness of the economy. Such differences can also exist among different regions within the same country and differentially influence entrepreneurial cognition, learning, and activities in these regions. Additionally, it remains an interesting research question whether our research context, China, a collectivistic culture, is itself a boundary condition for our theories and findings. Therefore, a possible direction for future research is to test the generalizability of our findings in other cultural and institutional contexts, or more directly operationalize contextual factors like these, and to explore their potential influences on learning across distance. We end this paper by calling for more research attention to the role of cultural and institutional factors in studying organizations’ vicarious learning across distance.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ye Dai

Ye Dai is an assistant professor in the Department of Management at the Southern Illinois University Carbondale.

Gukdo Byun

Gukdo Byun is an assistant professor in the management department at Chungbuk National University, South Korea.

Jay I. Chok

Jay I. Chok is an associate professor of management at the Keck Graduate Institute of Applied Life Sciences.

Fangsheng Ding

Fangsheng Ding is an associate professor of management at Zhejiang Ocean University.

Notes

15. We define “referent firms” as those firms chosen by new ventures as major information sources and benchmarks for decision‐making. Even though, we do not restrict these referents to the same narrowly defined industries where focal new ventures are located, as evident from data in our study, new ventures typically chose referent firms that were located in industries as close as possible to theirs.

16. Because of their short history of existence and the newness of their industrial environments, new ventures in emerging industries are often not able to observe repetitive patterns or sequences of referent firm choices and outcomes. This limits the effectiveness of inductive inference. Conversely, a valid conclusion derived from deductive inference depends on the validity of what is assumed. However, the complexity of ever‐changing business environments often limits the universal validity of assumptions that could be used in deductive inference.

17. The survey we administered was originally prepared in English. We then used the back‐translation method to prepare the Chinese version (Brislin Citation1980). After a pretest with 20 Chinese entrepreneurs (not included in the final sample), we further improved the wording of the survey to ensure the relevance and clarity of the questions.

18. We also manually assigned 4‐digit industry codes to the firms in the sample and their referent firms and then examined whether each of the firms and its referent firm belong to the same industry category. Among all the 175 firms in our sample, only 17 firms were considered as being in different industries than those of their referent firms.

19. The Cronbach's alpha index for the measure is 0.84, indicating satisfactory reliability. The inter‐rater agreement score (rwg; James, Demaree, and Wolf Citation1993) for the speed measure was over 0.70 and above the conventional 0.60 cutoff point. This indicates a high level of convergence among the perceived scores of respondents for this firm‐level variable provided by the respondents. The ICC(l) score for the measure was greater than zero with corresponding significant F‐statistics, which suggests the reliability of individual responses (Bartko Citation1976). Furthermore, its ICC(2) score was above the conventional 0.70 threshold, which indicates that the average score for this perceptual measure from the respondents is a reliable measurement of this firm‐level variable (Bartko Citation1976).

20. Our focus on the geographic distance as a predictor gives rise to a question regarding possible endogeneity of the focal firms’ distance choices. There is large geographic dispersion in the referent firms in this study and new venture location choices in China are strongly constrained by the home locations of entrepreneurs, both of which reduce the likelihood of a learning‐based motivation for distance choices. However, to explore the possibility of endogeneity, we followed several steps. First, we asked participating entrepreneurs for the percentage of their sales that were exported in the past year and used it as an instrumental variable. The choice was based on the rationale that a firm's export orientation influences the competitive intensity between the firm and other similar firms, including its referent firm, in the domestic market and, in turn, the distance choice of the new entrant. Consistent with the rationale, we found that export orientation was significantly associated with geographic distance (r = 0.30, p < .01), but was insignificantly associated with the firms’ speed of ISO 9000 requirements fulfillment (r = 0.02, n.s.). Second, a Durbin–Wu–Hausman test (Greene Citation2011) using export orientation as an instrumental variable revealed that the coefficient for the residual term was insignificant. Finally, the geographic distance variable remained significant even after adding the export‐orientation as an instrument in a two‐stage least squares regression. These results suggest that endogeneity is not likely an issue in the sample.

21. Indeed, informal conversations with participating entrepreneurs indicated that some new firms actively document the activities and outcomes of their referent firms, even those referents located afar, and frequently use the observed information in strategy making (although the empirical results suggest that geographic distance between a firm and its referent generally reduces the effectiveness of such learning).

References

- Abolafia, M. (2010). “Narrative Construction as Sensemaking,” Organization Studies 3, 349–367.

- Agarwal, R., and B. L. Bayus (2004). “Creating and Surviving in New Industries,” in Business Strategy over the Industry Lifecycle, Advances in Strategic Management. Eds. Baum J. A. C. and Mcgahan A. M.. Bingley, UK: Emerald, 107–130.

- Aiken, L. S., and S. G. West (1991). Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Argote, L. (2013). Organizational Learning: Creating, Retaining and Transferring Knowledge, 2nd ed. New York: Springer.

- Atiase, R. K. (1985). “Predisclosure Information, Firm Capitalization, and Security Price Behavior Around Earnings Announcements,” Journal of Accounting Research 23, 21–36.

- Bartko, J. J. (1976). “On Various Intraclass Correlation Reliability Coefficients,” Psychological Bulletin 83(5), 762–765.

- Baum, J. A., and H. A. Haveman (1997). “Love Thy Neighbor? Differentiation and Agglomeration in the Manhattan Hotel Industry, 1898–1990,” Administrative Science Quarterly 42, 304–338.

- Baum, J. A., and P. Ingram (1998). “Survival‐Enhancing Learning in the Manhattan Hotel Industry, 1898–1980,” Management Science 44, 996–1016.

- Blau, P. M. (1977). Inequality and Heterogeneity: A Primitive Theory of Social Structure. New York: Free Press.

- Borgatti, S. P., and R. Cross (2003). “A Relational View of Information Seeking and Learning in Social Networks,” Management Science 49, 432–445.

- Boschma, R. A., and K. Frenken (2006). “Why Is Economic Geography Not an Evolutionary Science? Towards an Evolutionary Economic Geography,” Journal of Economic Geography 6, 273–302.

- Brislin, R. W. (1980). “Translation and Content Analysis of Oral and Written Material,” in Handbook of Cross‐Cultural Psychology. Eds. Triandis H. C. and Berr J. W.. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 389–444.

- Chakrabarti, A., and W. Mitchell (2013). “The Persistent Effect of Geographic Distance in Acquisition Target Selection,” Organization Science 24, 1805–1826.

- Chang, S. J., and S. Park (2005). “Types of Firms Generating Network Externalities and MNCs’ Colocation Decisions,” Strategic Management Journal 26, 595–615.

- Chen, J. Y., R. R. Reilly, and G. S. Lynn (2005). “The Impacts of Speed‐to‐Market on New Product Success: The Moderating Effects of Uncertainty,” IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 52(2), 199–212.

- Chrisman, J. J., and W. E. Mcmullan (2004). “Outsider Assistance as a Knowledge Resource for New Venture Survival,” Journal of Small Business Management 42, 229–244.

- Covin, J. G., and D. P. Slevin (1989). “Strategic Management of Small Firms in Hostile and Benign Environments,” Strategic Management Journal 10, 75–87.

- Cummings, J. N. (2008). “Leading Groups from a Distance: How to Mitigate Consequences of Geographic Dispersion,” in Leadership at a Distance: Research in Technologically‐Supported Work. Ed. Weisband S. P.. Abingdon, UK: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 33–50.

- Davis, G. F. (1991). “Agents without Principles? The Spread of the Poison Pill through the Intercorporate Network,” Administrative Science Quarterly 36(4), 583–613.

- Dennis, S. A., and I. G. Sharpe (2005). “Firm Size Dependence in the Determinants of Bank Term Loan Maturity,” Journal of Business Finance and Accounting 32, 31–64.

- Douglas, T. J., and W. Q. Judge (2001). “Total Quality Management Implementation and Competitive Advantage: The Role of Structural Control and Exploration,” Academy of Management Journal 44(1), 158–169.

- Dudley, M. (1990). “Competition by Choice: The Impact of Consumer Search on Firm Location Decisions,” The American Economic Review 80, 1092–1104.

- Fagerberg, J., and M. Srholec (2008). “National Innovation Systems, Capabilities and Economic Development,” Research Policy 37, 1417–1435.

- Fryges, H., K. Kohn, and K. Ullrich (2015). “The Interdependence of R&D Activity and Debt Financing of Young Firms,” Journal of Small Business Management 53, (1), 251–277.

- Ghemawat, P. (2001). “Distance Still Matters: The Hard Reality of Global Expansion,” Harvard Business Review 79(8), 137–147.

- Gittelman, M., and B. Kogut (2003). “Does Good Science Lead to Valuable Knowledge? Biotechnology Firms and the Evolutionary Logic of Citation Patterns,” Management Science 49, 366–382.

- Golledge, R. G., and R. J. Stimson (1997). Spatial Behavior: A Geographic Perspective. New York: Guilford Press.

- Grant, R. M. (1996). “Toward a Knowledge‐Based Theory of the Firm,” Strategic Management Journal 17(Winter Special Issue), 109–122.

- Greene, W. (2011). Econometric Analysis, 7th ed. India: Pearson.

- Greve, H. R. (1999). “Branch Systems and Nonlocal Learning in Populations,” in Advances in Strategic Management: Population Level Learning and Industry Change. Eds. Miner A. S. and Anderson P.. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 57–80.

- Hamel, G., and C. K. Prahalad (1990). “Corporate Imagination and Expeditionary Marketing,” Harvard Business Review 69(4), 81–92.

- Harms, R. (2015). “Self‐Regulated Learning, Team Learning and Project Performance in Entrepreneurship Education: Learning in a Lean Startup Environment,” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 100, 21–28.

- Hasan, I., P. Wachtel, and M. Zhou (2009). “Institutional Development, Financial Deepening and Economic Growth: Evidence from China,” Journal of Banking and Finance 33, 157–170.

- Haunschild, P. R. (1993). “Interorganizational Imitation: The Impact of Interlocks on Corporate Acquisition Activity,” Administrative Science Quarterly 38, 564–592.

- Haunschild, P. R., and C. Beckman (1998). “When Do Interlocks Matter? Alternate Sources of Information and Interlock Influence,” Administrative Science Quarterly 43, 815–844.

- Haunschild, P. R., and A. S. Miner (1997). “Modes of Interorganizational Imitation: The Effects of Outcome Salience and Uncertainty,” Administrative Science Quarterly 42, 472–500.

- Haunschild, P. R., and M. Rhee (2004). “The Role of Volition in Organizational Learning: The Case of Automotive Product Recalls,” Management Science 50(11), 1545–1560.

- Hayek, F. A. (1994). The Road to Serfdom. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Hmieleski, K. M., and R. A. Baron (2008). “Regulatory Focus and New Venture Performance: A Study of Entrepreneurial Opportunity Exploitation Under Conditions of Risk versus Uncertainty,” Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 2, 285–299.

- Hoskisson, R., R. Johnson, L. Tihanyi, and R. White (2005). “Diversified Business Groups and Corporate Refocusing in Emerging Economies,” Journal of Management 31, 941–965.

- Hu, C. H., and H. Y. Bai (2009). Tu Po (Breakthrough) ISO9000: Xin Zhiliang Guanli Gao Caiwu Shouyi (New Quality Management and High Financial Returns). Shenzhen, Guangdong, China: Haitian Press.

- Hull, R. M., and G. E. Pinches (1995). “Firm Size and the Information Contents of Over‐the‐Counter Common Stock Offerings,” The Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance 4, 31–55.

- Ingram, P., and J. A. Baum (1997). “Chain Affiliation and the Failure of Manhattan Hotels, 1898–1980,” Administrative Science Quarterly 42, 68–102.

- Ingram, P., and P. W. Roberts (2000). “Friendships Among Competitors in the Sydney Hotel Industry,” American Journal of Sociology 106, 387–423.

- James, L. R., G. R. Demaree, and G. Wolf (1993). “Rwg: An Assessment of Within‐Group Interrater Agreement,” Journal of Applied Psychology 78(2), 306–309.

- Kessler, E. H., and A. K. Chakrabarti (1999). “Speeding Up the Pace of New Product Development,” Journal of Product Innovation Management 16(3), 231–247.

- Kim, J. Y. J., and A. S. Miner (2007). “Vicarious Learning from the Failures and Near‐Failures of Others: Evidence from the US Commercial Banking Industry,” Academy of Management Journal 50, 687–714.

- Kirchhoff, B., S. Newbert, and S. Walsh (2007). “Defining the Relationship among Founding Resources, Strategies, and Performance in Technology Intensive New Ventures: Evidence from the Semiconductor Silicon Industry,” Journal of Small Business Management 45(4), 438–466.

- Kolympiris, C., and N. Kalaitzandonakes (2013). “Geographic Scope of Proximity Effects Among Small Life Sciences Firms,” Small Business Economics 40, 1059–1086.

- Krugman, P. (1991). “Increasing Returns and Economic Geography,” Journal of Political Economics 99, 483–499.

- Landier, A., B. V. Nair, and J. Wulf (2009). “Trade‐Offs in Staying Close: Corporate Decision Making and Geographic Dispersion,” Review of Financial Studies 22, 1119–1148.

- Lanza, A., and M. Passarelli (2014). “Technology Change and Dynamic Entrepreneurial Capabilities,” Journal of Small Business Management 52(3), 427–450.

- Li, J. J., L. Poppo, and K. Z. Zhou (2008). “Do Managerial Ties in China Always Produce Value? Competition, Uncertainty, and Domestic vs. Foreign Firms,” Strategic Management Journal 29, 383–400.

- Linton, J. D., and S. Walsh (2004). “Integrating Innovation and Learning Curve Theory: An Enabler for Moving Nanotechnologies and Other Emerging Process Technologies into Production,” R&D Management 34(5), 513–522.

- Lowik, S., D. van Rossum, J. Kraaijenbrink, and A. Groen (2012). “Strong Ties as Sources of New Knowledge: How Small Firms Innovate Through Bridging Capabilities,” Journal of Small Business Management 50, 239–256.

- Lynn, G. S., R. B. Skov, and K. D. Abel (1999). “Practices That Support Team Learning and Their Impact on Speed to Market and New Product Success,” Journal of Product Innovation Management 16(5), 439–454.

- Maes, J., and L. Sels (2014). “SMEs' Radical Product Innovation: The Role of Internally and Externally Oriented Knowledge Capabilities,” Journal of Small Business Management 52(1), 141–163.

- March, J. G., and H. A. Simon (1958). Organizations. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

- March, J. G., L. S. Sproull, and M. Tamuz (1991). “Learning from Samples of One or Fewer,” Organization Science 2, 1–13.

- Miner, A. S., and P. R. Haunschild (1995). “Population Level Learning,” in Research in Organizational Behavior. Eds. Cummings L. L. and Staw B. M.. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 115–166.

- Peirce, C. S. (1883). “Theory of Probable Inference,” in Studies in Logic. Ed. Hopkins J.. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 126–181.

- Peng, M. W., and P. S. Heath (1996). “The Growth of the Firm in Planned Economies in Transition: Institutions, Organizations, and Strategic Choice,” Academy of Management Review 21, 492–528.

- Peteraf, M., and M. Shanley (1997). “Getting to Know You: A Theory of Strategic Group Identity,” Strategic Management Journal 18, 165–186.

- Pistor, K., and P. A. Wellons (1999). The Role of Law and Legal Institutions in Asian Economic Development. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

- Polanyi, M. (1958). Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post‐Critical Philosophy. London: Routledge.

- Porac, J. F., H. Thomas, F. Wilson, D. Paton, and A. Kanfer (1995). “Rivalry and the Industry Model of Scottish Knitwear Producers,” Administrative Science Quarterly 40, 203–227.

- Posen, H. E., and J. S. Chen (2013). “An Advantage of Newness: Vicarious Learning Despite Limited Absorptive Capacity,” Organization Science 24, 1701–1716.

- Presutti, M., C. Boari, and A. Majocchi (2011). “The Importance of Proximity for the Start‐Ups' Knowledge Acquisition and Exploitation,” Journal of Small Business Management 49, 361–389.

- Rennie, M. W. (1993). “Global Competitiveness: Born Global,” McKinsey Quarterly 4, 45–52.

- Rosenkopf, L., and P. Almeida (2003). “Overcoming Local Search Through Alliances and Mobility,” Management Science 49, 751–766.

- Ross, W. T., Jr., and E. H. Creyer (1992). “Making Inferences About Missing Information: The Effects of Existing Information,” Journal of Consumer Research 19(1), 14–25.

- Roundy, P. T., and M. Graebner (2013). “Can Stories Shape Strategy? Narrative‐Structured Information and Strategic Decision Making,” Academy of Management Proceedings 2013(1), 10851.

- Sanders, W. G., and M. A. Carpenter (1998). “Internationalization and Firm Governance: The Roles of CEO Compensation, Top Team Composition, and Board Structure,” Academy of Management Journal 41, 158–178.

- Saxenian, A. (1994). Regional Advantage: Culture and Competition in Silicon Valley and Route 128. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Singh, J., and M. Marx (2013). “Geographic Constraints on Knowledge Diffusion: Political Borders vs. Spatial Proximity,” Management Science 59, 2056–2078.

- Sorenson, O., and P. Audia (2000). “The Social Structure of Entrepreneurial Activity: Geographical Concentration of Footwear Production in the U.S., 1940–1989,” American Journal of Sociology 106, 424–462.

- Sorenson, O., and J. A. Baum (2003). “Geography and Strategy: The Strategic Management of Space and Place,” in Geography and Strategy: Advances in Strategic Management. Eds. O., Sorenson and Baum J. A.. Bingley, UK: Emerald, 1–19.

- Srinivasan, R., P. Haunschild, and R. Grewal (2007). “Vicarious Learning in New Product Introductions in the Early Years of a Converging Market,” Management Science 53, 16–28.

- Stankard, M. F. (2002). Management Systems and Organizational Performance: The Search for Excellence beyond ISO9000. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

- Stein, J. C. (2002). “Information Production and Capital Allocation: Decentralized vs. Hierarchical Firms,” Journal of Finance 57, 1891–1921.

- Stinchcombe, A. L. (1965). “Organizations and Social Structure,” in Handbook of Organizations. Ed. J. G. March. Chicago: Rand‐McNally, 153–193.

- Tamanaha, B. Z. (2004). On the Rule of Law: History, Politics, Theory. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.