Abstract

Extensive research exists on the individual determinants of being an immigrant entrepreneur, concerning both social environment and human capital. However, the role of the judiciary has not been investigated yet. Analyzing more than 160,000 new micro enterprises owned by immigrants, our paper aims to fill this gap by focusing on the relation between justice and immigrant entrepreneurship. Results show that judicial efficiency is one of the determinants of self‐employment, although some differences among immigrant groups are identified. Therefore, the study confirms the key role of judicial enforcement in promoting not only growth but also the integration of these new citizens.

Introduction

Immigration flows are an important feature of many European countries. The phenomenon is relatively recent in Italy compared to other EU states, and it has been mainly concentrated in the last few decades (Venturini Citation1999). Indeed, in France and the United Kingdom, as well as in Spain and Portugal, the influx of immigrants from the ex‐colonies has been more gradual over time and related to specific ethnic groups. In Italy, the situation is significantly more complex, due to the specific moment in which immigration flows started and the social, cultural, and economic conditions found by immigrants (Quassoli Citation1999). However, according to national statistics, immigrant entrepreneurship is considerable and plays an increasingly important role in the country's economic growth (Piergiovanni, Carree, and Santarelli Citation2012). The creation and development of new enterprises managed by immigrants have been growing over time and the trend is more than linear in relation to immigration flows (CNEL Report Citation2011). This phenomenon represents an interesting case in order to investigate the motivations behind immigrant entrepreneurial choices, especially when we consider the main role of entrepreneurs in economic growth (Acs, Desai, and Hessels Citation2008; Nijkamp Citation2003; Santarelli Citation2006), as well as urban development and integration of immigrants (Baycan‐Levent, Nijkamp, and Sahin Citation2009; Razin and Light Citation1988).

An increasing number of studies have focused on ethnic and immigrant entrepreneurship, for instance in the United Kingdom (Clark and Drinkwater Citation2010; Levie Citation2007) or the United States (Köllinger and Minniti Citation2006; Shinnar and Young Citation2008). Nevertheless, the situation in Italy has been almost entirely neglected and only a handful of works have been proposed (Brzozowski, Cucculelli, and Surdej Citation2014; CNEL Report Citation2011; Quassoli Citation1999; Riva and Lucchini Citation2015). Looking more specifically at the motivations driving ethnic entrepreneurship, scholars have mainly investigated the social and economic factors behind the immigrants’ decision to start a new business (e.g., Tienda and Raijman Citation2004), but no study has analyzed the relation between judicial efficiency and entrepreneurial choices. Several studies have highlighted the relation between enforcement and entrepreneurship (e.g., Chemin Citation2009; Ippoliti et al. Citation2015a; Lichand and Soares Citation2011), but none of these have focused on the choice of location by immigrant entrepreneurs, that is, a share of the total national entrepreneurship which is more flexible and mobile. Moreover, scholars have focused almost exclusively on the impact of bankruptcy enforcement on entrepreneurial choices (Armour and Cumming Citation2008; Fossen Citation2014).Footnote24

Referring to the concept of mixed embeddedness, that is, highlighting the key role of both social networks and the socio‐economic and political‐institutional framework (Barrett, Jones, and McEvoy Citation2001; Barrett et al. Citation2002; Jones et al. Citation2014; Kloosterman, Rusinovic, and Yeboah Citation2016), this work analyzes the proposed relation in an innovative way, considering one‐man companies owned by immigrant entrepreneurs and the judicial enforcement institutions. Indeed, the paper hypothesizes that the performance of the judicial system might affect the decision by these new citizens to start an entrepreneurial activity, accepting the formal rules of the new society. The proposed theory is coherent with the mixed embeddedness approach (Kloosterman Citation2010; Kloosterman and Rath Citation2001; Kloosterman, Van der Leun, and Rath Citation1999) since, on the one hand, immigrants might be clearly affected by their ethnic group (internal force) while, on the other hand, they might be conditioned by the institutional, social, and economic framework of the host country (external force), which represents the so‐called opportunity structure. The combined forces of social networks and opportunity structures might drive an immigrant to start a new business within the formal market. Obviously, the choice of the key opportunity structure made in this paper (i.e., the judicial enforcement system) constitutes its main contribution to the current literature.

The expected positive relation between judicial efficiency and entrepreneurship might be due to the courts’ ability to enforce the rights of entrepreneurs. On the one hand, the security of property rights can reinforce incentives to invest, by protecting returns on entrepreneurial activities (Bianco, Jappelli, and Pagano Citation2005; Djankov et al. Citation2008). On the other hand, enforcing the rules can also stimulate these agents to initiate (legal) relationships, thus reducing opportunistic behavior (i.e., working in the informal/criminal market).Footnote25 The above circumstances should have a positive impact on the immigrants’ decision to accept the rules of the new country, stimulating their entrepreneurial choices and their introduction to the formal economy (Quassoli Citation1999). This result might be even more significant if we consider the extent of Italy's gray economy and the potential risk that these immigrants might move to an alternative market, instead of the formal one, which does not respect the rules of society.Footnote26 In this vein, the proposed case study might contribute to filling the current gap, highlighting the above‐mentioned relation and offering suggestions to face one of the main challenges of European societies in the current age of migrations, that is, the integration of new citizens moving from the poorest to the richest countries.Footnote27

The structure of this paper is as follows. The first section proposes the theoretical background concerning immigrant entrepreneurships and judicial enforcement institutions and surveys the literature on mixed embeddedness and judicial efficiency, highlighting the current knowledge on self‐employment determinants and measures of courts’ performance. The second section proposes the adopted methodology, while the third section illustrates the data and some descriptive statistics. The results of the empirical analysis are set out in the fourth section, while the last section puts forward some conclusions.

Theoretical Background and Literature Review

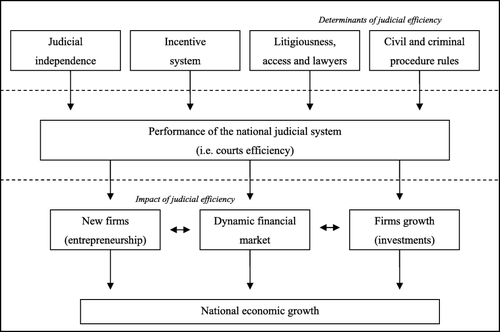

Spurred by the efforts of governments and international organizations—including the European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ) and the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), as well as the Organization for Economic Co‐operation and Development (OECD), and the World Bank, the judiciary has been deeply analyzed in the last decades. In particular, researchers have focused their interest on the determinants of courts performance and on the economic impact of the enforcement system. Taking courts and the determinants of their performance into account, researchers have analyzed the independence of judges (Feld and Voigt Citation2003; Ríos‐Figuero and Staton Citation2014) and their incentive system (Cooter Citation1983; Posner Citation1993), as well as the impact of litigiousness and/or the number of lawyers (Carmignani and Giacomelli Citation2010; Ippoliti Citation2014), or the adopted civil and criminal procedure rules (Lanau, Esposito, and Pompe Citation2014). Considering the impact of the judiciary on the economy, the current literature points to the existence of a positive relation between judicial efficiency and economic growth. In particular, there is evidence that the performance of courts can affect business demography, that is to say, new entries on the market (i.e., entrepreneurship) and the growth of already existing firms. Indeed, observations on more efficient courts show the presence of larger firms than those found in weaker legal environments (Dougherty Citation2014; Garcìa‐Posada and Mora‐Sanguinetti Citation2015; Giacomelli and Menon Citation2013; Kumar, Rajan, and Zingales Citation2001; Laeven and Woodruff Citation2007). In other words, a healthy environment in which there is certainty about the enforcement of rights can have a positive influence on the growth of the economy (Beck, Demirguc‐Kunt, and Maksimovic Citation2006; La Porta et al. Citation2000; Levine Citation1999). Finally, taking the financial market into account, the current literature stresses the key role of judicial efficiency (Claessens and Klapper Citation2009; White Citation2009). In fact, the performance of the legal system can affect not only access to the credit market (Bianco, Jappelli, and Pagano Citation2005; Burkart and Ellingsen Citation2002; Fabbri Citation2001) but also the financial structure of enterprises (Giacomelli and Menon Citation2013). Evidence from research suggests that mortgage interest rates are correlated to the enforcement ability of the legal system (Jaffee Citation1985; Meador Citation1982), while the presence of less lending and more nonperforming loans are identified where the enforcement system is not efficient (Castelar Pineiro and Cabral Citation2001; Cristini, Moya, and Powell Citation2001; Fabbri and Padula Citation2001). Moreover, Fabbri (Citation2010) suggests that judicial enforcement might have a significant impact on business financing.

Figure 1 summarizes the main hypothesis behind the relation between judicial efficiency and economic growth, as mentioned above. On the one hand, we can observe the determinants of judicial performance, that is, judicial independence or the incentive system, as well as litigiousness or the number of lawyers and the adopted procedural rules. On the other hand, we have the main impacts of courts efficiency on the economy, that is, more vivacious business demography and a dynamic financial market with less distress. Obviously, these impacts can lead to national economic growth; moreover, they might contribute to creating an opportunity structure. Indeed, all of these positive impacts can shape the market in which potential entrepreneurs might enter, providing opportunities to start new successful businesses, that is to say, creating an institutional, social, and economic framework able to stimulate and facilitate entrepreneurship.

In this work, referring to the mixed embeddedness approach, the authors aim to shed new light on the relation between entrepreneurship and the judiciary by focusing on a specific case study, that is, immigrant entrepreneurship in Italy between 2006 and 2008. This represents a remarkable opportunity to analyze the relation between enforcement institutions and immigrant integration, highlighting the potential key role of judicial efficiency as opportunity structure (Kloosterman and Rath Citation2001; Kloosterman, Van der Leun, and Rath Citation1999). Indeed, as explained by Jones et al. (Citation2014) and Barrett and Vershinina (Citation2017), social capital must be placed in its proper context, that is, the political‐economic environment of the market and the legal structure which regulates it. In other words, entrepreneurial initiatives have to be grounded in more than one sphere of influence instead of solely in their own ethnic network (Kloosterman Citation2010). Several case studies have been proposed by researchers to shed new light on the concept of mixed embeddedness, linking the resources of (aspiring) migrant entrepreneurs to the specific local urban opportunity structure. Just to cite a few, Barrett, Jones, and McEvoy (Citation2001), Barrett et al. (Citation2002), and Jones et al. (Citation2014) focus on immigrant businesses in the United Kingdom, Price and Chacko (Citation2009) study Ethiopian and Bolivian immigrants in the United States, Peters (Citation2002) analyzes immigrant entrepreneurship in Australia, while Kloosterman, Rusinovic, and Yeboah (Citation2016) investigate ethnic entrepreneurial activities in the Netherlands. Nevertheless, none of these works focus on the judiciary.

Innovatively, this work aims to test the relation between the concentration of immigrant entrepreneurs and the efficiency of judicial enforcement institutions (our opportunity structure). These potential foreign entrepreneurs might move to places where an enclave from their home country exists and then, if there are optimal economic, institutional, and/or social‐cultural conditions, they might decide to start an independent business on the formal market (i.e., applying and respecting the legal rules of that market). This is exactly the idea of mixed embeddedness proposed in this work. On the one hand, there is an enclave effect (internal force), which can support the new citizens in the host country, and, on the other hand, there is an institutional effect, which can lead these immigrants to integration (external force). Obviously, our key optimal (external) condition is the judicial enforcement institution, which is also essential to prevent these immigrants from moving toward another type of market to make money, that is, the informal/criminal market. Indeed, according to Quassoli (Citation1999), these immigrant entrepreneurs might be attracted by the alternative informal/criminal market, since they might observe both leaner bureaucracy and lower costs to start their entrepreneurial activity, that is, higher expected gain. The judicial system might decrease that expected gain, enforcing the rules of the formal market and, in doing so, leading immigrants to integrate into the formal market and society. This idea is coherent with the model proposed by Lofstrom (Citation2002), which addresses the immigrants’ decision to start an entrepreneurial activity on the formal market, even though in that case the alternative choice is employment (i.e., labor market). In relation to this, how can immigrant entrepreneurs, who know almost nothing about their host country, be affected by judicial efficiency? Who might direct these new immigrants’ attention toward this key factor?

A realistic explanation is that immigrant entrepreneurs might be driven by their community, which has been staying in the host country and might have previous experience with the judicial system. In other words, the decision by these new citizens to become entrepreneurs on the formal or informal market might be driven by the very ethnic group that is actively supporting them. This ethnic group, which is already there and knows how the local society works, can facilitate the arrival of these new citizens and their initial accommodation in the new country, and influence their decision to become entrepreneurs or employees. In other words, this ethnic network will guide them in the key decision about whether to move in the legal or illegal world, based on the previous experience of their members. If they know that the judicial system works very well, that is, the courts are able to efficiently enforce the rules of society, we can expect the members of the network to lead these new entrepreneurs toward the legal market. Otherwise, if the enforcement system is not efficient, we can expect a lower concentration in the legal market. Therefore, referring to the proposed mixed embeddedness approach, we can talk about an indirect external force driven by the immigrants’ ethnic community.

Taken as a whole, this logic suggests the following hypothesis:

H1: The concentration of immigrant entrepreneurs is positively affected by the courts’ ability to enforce justice.

Controlling for some key variables and an estimated measure of judicial efficiency, which will be introduced in the model according to the following literature review, the empirical analysis will test whether this hypothesis cannot be rejected. Moreover, in order to support our results with a higher level of robustness, a parallel analysis considering autochthonous entrepreneurs will be proposed. By doing so, we will have the opportunity to test whether Italian‐born entrepreneurs respond to these same differences in judicial efficiency, confirming the hypothesis that the observed behavior of immigrant entrepreneurs is mirrored by autochthonous entrepreneurs. Indeed, we expect the same results regarding the relation between efficiency and entrepreneurs, although Italian‐born entrepreneurs can make decisions based on their own previous experience.

The following literature review is divided into two subsections: the first considers the determinants of immigrant and ethnic entrepreneurship, while the second presents the measures of judicial efficiency.

Determinants of Ethnic and Immigrant Entrepreneurship

The literature on the motivations driving entrepreneurship is very broad and the phenomenon has been thoroughly analyzed in recent decades. Just to cite a few, there are studies on the decisions to become and stay self‐employed, focusing on women and gender issues (Cramer et al. Citation2002; Noseleit Citation2014; Patrick, Stephens, and Weinstein Citation2016), personality characteristics (Caliendo, Fossen, and Kritikos Citation2014; Ciavarella et al. Citation2004; Fairlie and Holleran Citation2012), age (Lévesque and Minniti Citation2006; Minola, Criaco, and Obschonka Citation2016), and education (Bergmann, Hundt, and Sternberg Citation2016; Hoppe Citation2016). Other works focus on the success of immigrants’ entrepreneurial activities investigating, for example, ethnic and business networks (Basu and Altinay Citation2002; Rezaei Citation2009; Schøtt et al. Citation2014) or multicultural and multi‐linguistic competences (Light, Rezaei, and Dana Citation2013).

Focusing more specifically on ethnic and immigrant entrepreneurship, the current literature identifies two main types of factors, referred to as push factors and pull factors (Bates Citation1999). As highlighted by Shinnar and Young (Citation2008), pull factors are related to self‐employment opportunities (i.e., mobility motives), while push factors explain this choice as a last resort (i.e., escape motives). Moreover, Block and Sandner (Citation2009) identify two different types of entrepreneurs: on the one hand, an individual who steps into self‐employment voluntarily (i.e., an opportunity entrepreneur) and, on the other hand, an individual who starts self‐employment out of necessity (i.e., a necessity entrepreneur).

Analyzing the escape motives, the disadvantage theory ascribes self‐employment to low wages, chronic unemployment, and labor market discrimination (Paulson and Townsend Citation2005; Rissman Citation2006). Similarly, the labor market theory explains ethnic entrepreneurship in terms of exclusion from the primary job market (Alvarez Citation1990; Blume et al. Citation2009), which is clearly due to discrimination, language barriers, and incompatible education or training (Fairlie Citation2008; Tienda and Raijman Citation2004). Taking the mobility motivations into account, among the determinants of self‐employment are desire for economic independence and/or autonomy (Wilson, Marlino, and Kickul Citation2004; Zuiker Citation1998), human capital coming from the home country (Bohon Citation2001; Lofstrom Citation2002), and concentration of the same ethnic/immigrant group in a certain metropolitan area, that is, the enclave effect (Clark and Drinkwater Citation2002; Shinnar and Young Citation2008; Tienda and Raijman Citation2004). Finally, looking at the economic factors, scholars identify a positive relation between self‐employment and high unemployment rate (Tervo Citation2006), larger amounts of small‐scale business activities (Armington and Acs Citation2002; Gabe Citation2003), population density, and overall income (Wang Citation2010).

According to the proposed literature review and the suggested hypothesis, this work adopts some cultural and social factors as control variables in the analysis of immigrants’ self‐employment (e.g., geographical macro‐areas, population density, and enclaves), as well as some economic factors (e.g., unemployment rate and average income).

Measures of Judicial Efficiency

Spurred by the efforts of governments and international organizations, a “fragmented” body of literature has recently sought to gain deeper insights into the workings of courts, to better understand and thereby improve the performance of judicial systems (e.g., CEPEJ Citation2012; OECD Citation2013). Focusing on the literature and the adopted measures of efficiency, several methods have been proposed which involve assessing, for instance, the time needed to settle a case (Christensen and Szmer Citation2012; Di Vita Citation2010; Mitsopoulos and Pelagidis Citation2007), technical efficiency scores (Falavigna et al. Citation2015; Ippoliti Citation2015; Ippoliti et al. Citation2015; Santos and Amado Citation2014), the number of cases completed by a court (Beenstock and Haitovsky Citation2004; Ramseyer Citation2012), and clearance rates (CEPEJ Citation2012; Ippoliti and Vatiero Citation2014; Soares and Sviatschi Citation2010). However, significant differences exist among these estimations and, in some cases, the matters analyzed do not specifically concerns efficiency.

On the one hand, the number of cases completed by a court is an output estimation and, without considering the inputs needed to produce that output, we cannot identify that indicator as a proper measure of efficiency. Clearance rate is simply that output estimation, but normalized for the incoming cases (i.e., the flow of the demand for justice).Footnote28 On the other hand, technical efficiency scores are broadly recognized as a good measure of productivity estimation and they can consider both the resources necessary to produce that output (e.g., judges and staff) and environmental variables (e.g., demand for justice). Finally, the time needed to settle a case is more strictly related to the outcome of this government activity, that is, the supply of justice. Therefore, if justice is an outcome, then denied justice can only be considered a negative outcome, that is to say, a negative externality produced by the government's inefficiency in producing the expected output (i.e., settled cases).Footnote29

Based on the literature reviewed and the aforementioned considerations, this work proposes technical efficiency scores as explanatory variables of the opportunity structure. This measure is estimated using the Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA), which has been successfully adopted in judicial analysis both in its one‐stage form (Chaparro and Jimenez Citation1996; Kittelsen and Førsund Citation1992; Lewin, Morey, and Cook Citation1982) and in its two‐stage form (Deyneli Citation2012; Ippoliti Citation2014; Schneider Citation2005).Footnote30

Methodology

This work focuses on the relation between the efficiency of judicial enforcement institutions and immigrant entrepreneurship. First of all, measures of the judicial efficiency of Italian courts and of self‐employment are estimated. Afterward, the efficiency measures are used as key explanatory variables of entrepreneurial choices. As for entrepreneurship, we focus on the overall birth rate of immigrant and autochthonous enterprises, as well as the number of new enterprises for some selected foreign groups. As for judicial efficiency, we propose a technical efficiency score.

The adoption of different measures will support more robust results and, at the same time, provide more detailed information on judicial performance and how it can affect entrepreneurship.

Judicial Technical Efficiency Scores

DEA is a nonparametric technique which allows efficiency performance to be measured as a score (Cook and Seiford Citation2009). The DEA approach lets researchers build a deterministic, nonparametric production frontier comparing the performance of several Decision‐Making Units (DMUs), which in our case are the courts of first instance, aggregated at the district level (i.e., Distretti di Corte di Appello).Footnote31 Technical efficiency scores are computed based on the radial distance of every DMU from the frontier.Footnote32 Here we have used the output‐oriented model, as proposed by Farrell (Citation1957), and we have also assumed Variable Returns to Scale (VRS) (Banker, Charnes, and Cooper Citation1984).

The technical efficiency scores (TEi) referring to each court (DMU) are computed as follows:

where n is the number of DMUs and 1 ≤ TEi ≤ +∞.

TEi scores are computed by solving the following linear programing duality problem, on the basis of the output‐oriented DEA approach (Farrell Citation1957):

where z is a scalar >1, λ is a vector of nx1 weights allowing for convex combination of inputs and outputs, Y is an sxn output matrix, X is an input matrix, and N1 is an Nx1 unitary vector. Furthermore, z − 1 indicates the proportional output increment maintaining the input level constant. The output‐oriented framework aims to maximize output levels while keeping the inputs constant, on the assumption that the inputs cannot be easily changed, at least in the short run. This orientation is also known as the “output‐augmenting” approach: it keeps the inputs bundle unchanged and expands the output level until the frontier is reached (Daraio and Simar Citation2007).

The results of the DEA methodology are technical efficiency scores referring to each element (in our case, judicial districts, i.e., Distretti di Corte di Appello) and representing its position in relation to the frontier. The scores indicate the ability of each district to maximize the number of cases settled at first level, given the available resources (judges) and the demand for justice at first level (both civil and criminal), in terms of both flow (i.e., incoming cases) and stock (i.e., pending cases at the beginning of each year).Footnote33 The idea of estimating a single technical efficiency score, considering both penal and civil justice, instead of two different estimations is conditioned by data availability.Footnote34

This measure will then be introduced into the regression model to evaluate the relation between efficiency and entrepreneurship, with the purpose of shedding light on the phenomenon investigated here.

Birth Rate of Enterprises

The proposed index is a key indicator of business dynamism and reflects an important dimension of entrepreneurship within a country, namely the capacity to start entirely new businesses (OECD Citation2012). Two birth rates are proposed. On the one hand, the birth rate of foreign enterprises is the relationship between new immigrant enterprises (i.e., the flow of entrepreneurship by immigrants) and the existing number of enterprises on the market (i.e., the stock of entrepreneurship on the market). On the other hand, the birth rate of autochthonous enterprises is the relationship between new Italian enterprises (i.e., the flow of entrepreneurship by Italians) and the existing number of enterprises on the market (i.e., the stock of entrepreneurship on the market). Therefore, both birth rates are equal to the flow of entrepreneurship divided by its stock:

where i represents the i‐th judicial district (i.e., the adopted geographical unit) considered at year(s) t.

Note that, in this specific case, we analyze one‐man companies (i.e., Ditte individuali or Persone fisiche), focusing on the role of judicial efficiency as a driver of immigrant entrepreneurship. For this reason, we do not distinguish between employer and nonemployer enterprises although, from an economic point of view, the latter type is more relevant than the former in relation to the notion of entrepreneurship as a driver of job creation and innovation. Moreover, the choice of this entrepreneurial form (i.e., one‐man company) relies on Italian regulations. Indeed, these entrepreneurs might start two main types of enterprises in Italy: one‐man or partnership (which might be a general partnership or a limited company). In the first case, an entrepreneur only needs a residency permit (if his/her citizenship is non‐EU) or an identity document (if his/her citizenship is EU) and, in few hours and with limited cost (approximately 150.00 Euro), the one‐man company will be established after a simple registration with the competent Chamber of Commerce. In the second case, the procedure is more complex and more expensive, since a partnership has to be legally established with the involvement of a notary (with an expected fee between 2,500.00 and 10,000.00 Euro). Moreover, capital (i.e., a deposit) is necessary in order to set up a limited company. To conclude, these entrepreneurs have two options, one cheaper and faster and one longer and more expensive, and the authors analyze the first option, which is more credible considering the proposed case study (Riva and Lucchini Citation2015).

The above indices will be the dependent variables of the empirical model proposed in the main empirical analysis while, in the sub‐analysis, the numerator (i.e., the number of new immigrant enterprises) will be adopted directly as the dependent (count) variable, but considering only some selected foreign groups (see OECD Citation2006). Finally, by comparing the two estimated rates (i.e., the birth rate of autochthonous enterprises and of immigrant ones), we can determine whether some differences actually exist.

Data

In this work, efficiency scores are computed considering the geographical jurisdiction of the second instance level but taking exclusively the justice at first instance level into account. In other words, DMUs are courts of first instance which have been aggregated at the district level. In the considered period (2006–2009), there were 26 districts, which means a total of 104 observations.

The variables used in order to obtain judicial technical efficiency scores are as follows:

Input: number of judges; incoming cases and pending cases (both civil and criminal justice);

Output: settled cases (both civil and criminal justice);

This means that there are five inputs and two outputs. Data about judicial activity have been extracted from the data set of the Ministry of Justice, while data about judges have been extracted from the data set of the Magistrates Governing Body (CSM).

The descriptive statistics regarding the variables used for the DEA methodology are shown in Table . Notice that we use the lagged variables of judicial efficiency (i.e., t − 1, at year(s) t) in relation to the decision to start a new entrepreneurial activity. In other words, we assume that the perceived efficiency at time t − 1 (i.e., the previous year) can affect the choice of whether to start a business at time t.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics: Inputs and Outputs Adopted for the Technical Efficiency Scores Second Instance Districts (i.e., Distretti di Corte di Appello), 2005–2008

Table shows the estimated average technical efficiency for every judicial district, as well as its judicial delay and the number of first instance districts within each second instance district. By considering the results we can easily understand the problem of the Italian judicial system, that is, the available resources necessary to satisfy the demand for justice. Indeed, despite all judicial districts being efficient (i.e., technical efficiency scores close to 1), the supply of justice is not able to satisfy the demand, resulting in a remarkably high number of days needed, on average, to settle a civil case (e.g., more than 800 days are necessary to complete a case in the districts of Bari, Messina, and Potenza). Obviously, the poor performance of Italian courts is also related to the backlog accumulated over the last decades, which still affects their current productivity. This is even more significant in the sector of civil justice, in which there is no prescription, that is, no time limit to complete trials.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics: Technical Efficiency Scores and Judicial Delay Second Instance Districts (i.e., Distretti di Corte di Appello), 2005–2008

The target of this study is the relation between entrepreneurship and judicial efficiency, controlling for some explanatory variables. The table below proposes descriptive statistics about self‐employment, which is under investigation in this work. In detail, the table lists macro‐regions by continent, indicating the total number of new enterprises started in Italy by entrepreneurs from each of said macro‐regions and their relative percentages. Data about the number of new one‐man enterprises are provided by the data set of the Italian National Institute of Statistic (ASIA, Italian Archive of Active Enterprises), while data about the stock of enterprises on the market in the previous year are provided by Chambers of Commerce (UNIONCAMERE data set). In order to map the nationality of the enterprises, the place of birth of the entrepreneurs is used as reference (Table ).Footnote35

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics: New Enterprises in Italy between 2006 and 2009

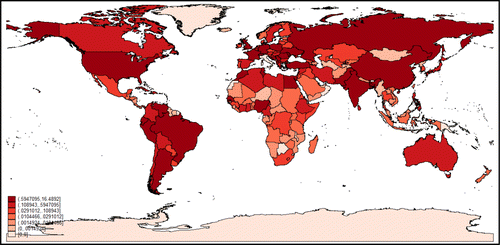

Table in the Appendix presents some detailed statistics about European countries (both EU and non‐EU), indicating the total number of new enterprises in Italy classified according to the entrepreneurs’ country of birth and their relative percentages, as well as the average age of these entrepreneurs and the percentage of women. It can be seen that, on average, more than 50,000 new entrepreneurs were born in Europe, with the highest percentage from Romania (43.49%, i.e., 22,098 enterprises), followed by Albania (28.98%, i.e., 14,725 enterprises).

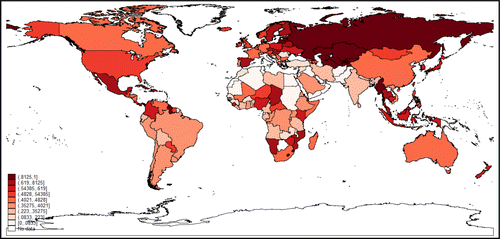

Among non‐European countries, on average, more than 23,000 new entrepreneurs were born in the BRIC countriesFootnote36 with the highest percentage from China (81.47%, i.e., 19,123 enterprises). See Figures A1 and A2 in the Appendix for a detailed mapping of these entrepreneurs.

The sub‐analysis focuses on three nationalities, that is, Chinese, Albanian, and Romanian entrepreneurs, which are the most numerous and the most recent immigrant groups and, taken together, represent more than 20% of the whole population of migrant entrepreneurs.Footnote37 Obviously, although there are other significant immigrant groups, like German entrepreneurs, they are not so relevant in numerical terms compared to the above groups and, for the sake of readability, only three immigrant groups have been considered.

In the empirical analysis, some explanatory variables are introduced to check the determinants of entrepreneurship. In detail, the following independent variables are proposed:

technical efficiency scores, which should capture the impact of judicial efficiency on self‐employment, considering the organization of the system (i.e., adopted resources, demand for and supply of justice), representing our key opportunity structure;

population residing in the judicial district (per km2), which is an independent variable to check the demographic density of the observations;

foreign population residing in the judicial district (per 1,000 inhabitants), which is an independent variable to check the enclave effect of the observationsFootnote38;

unemployment rate, which captures the state of the economy in the observations and tests the push factor, as suggested by the current literature;

people income (per capita, considering the resident population and taking inflation into account), which is an alternative variable referring to the state of the economy in the observations and is useful to test the pull factorFootnote39;

entrepreneur income (per capita, considering the Italian population of one‐man companies and taking inflation into account), which is a further alternative variable to check the state of the economy in the observations and test the pull factorFootnote40;

geographical macro‐areas, which are dummy variables introduced as independent variables aimed at considering the social and cultural background of the observations;

years, which are dummy variables introduced as independent variables to account for the time factor.

With reference to the geographical criteria, the districts are grouped into the following five macro‐areas:

North‐West: Districts of Turin, Milan, Brescia, and Genoa;

North‐East: Districts of Venice, Trento, Bologna, and Udine;

Center: Districts of Florence, Perugia, Ancona, and Rome;

South: Districts of Reggio Calabria, Catanzaro, Potenza, Salerno, Lecce, Bari, Naples, Campobasso, and L'Aquila;

Islands: Districts of Cagliari, Palermo, Caltanissetta, Catania, and Messina.

The birth rate of immigrant enterprises and the birth rate of autochthonous enterprises are the dependent variables of the main analysis, representing the entrepreneurial choices made by immigrants and Italians. As mentioned in the methodological section, this rate considers the number of new enterprises started by entrepreneurs each year (numerator) over the total population of enterprises on the market during the previous year (denominator). As suggested in the methodology section, only one‐man enterprises are analyzed (i.e., Ditte individuali or Persone fisiche). In the sub‐analysis, in order to control for the enclave effect, the number of new immigrant enterprises is proposed as dependent variable (count), representing the entrepreneurial choices made by some specific foreign communities. Our investigation focuses on the number of new enterprises started by Romanian, Chinese, and Albanian entrepreneurs. Obviously, in this second analysis, the main control variable is the foreign population, which is equal to the number of immigrants from a specific foreign community for every 1,000 inhabitants residing in each district.

Table sets out some descriptive statistics concerning the proposed dependent and independent variables, taking both the preliminary and the main analysis into account.

Table 4. Descriptive Statistics of Variables Adopted in the Empirical Analysis Second Instance Districts (i.e., Distretti di Corte di Appello), 2005–2008

Data about population and unemployment have been extracted from the data sets of the Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT), while data about income have been extracted from the data set of the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF). Data about immigrants come from the data set of the Ministry of the Interior.Footnote41 Finally, the income of the enterprises has been extracted from the data set of the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF).Footnote42

In the next section, the results of the empirical analysis are illustrated.

Empirical Analysis

In order to analyze the relation between entrepreneurship and judicial efficiency, both ordinary least squares (OLS) and negative binomial (NB) regression models are proposed, applying the robust option. We do not consider a panel data set but a pooled sample with some dichotomous variables in order to capture the time factor (i.e., a cross‐sectional analysis is implemented).Footnote43 As mentioned, a number of models are used in the main analysis, adopting the OLS estimator and introducing the three alternative variables on economic status (i.e., unemployment rate and per capita income, for both the general population and one‐man enterprises) as well as the two measures of entrepreneurship (i.e., birth rate of immigrant and autochthonous enterprises). Moreover, a third model is proposed, applying the NB estimator—since the dependent variable is count—and focusing exclusively on the main immigrant groups in Italy (i.e., Romanian, Chinese, and Albanian—see Table ) to test the potential enclave effect. The NB regression is an appropriate model for over‐dispersed count data, that is, when the conditional variance exceeds the conditional mean.Footnote44 It can be considered a generalization of Poisson regression, since it has the same mean structure but it uses an extra parameter to model over‐dispersion (Cameron and Trivedi Citation2013). The sub‐analysis, which focuses on the enclave effect, considers only one measure of judicial efficiency and one proxy for economy status, based on the results of the main analysis.

Tables show the results of the proposed models.

Table 5. OLS Regression Model—Robust Option Immigrant Enterprises Birth Rate as Dependent Variable

Table 6. OLS Regression Model—Robust Option Autochthonous Enterprises Birth Rate as Dependent Variable

Table 7. NB Regression Model—Robust Option, Regression Results Presented as IRR Romanian, Chinese, and Albanian Population of One‐Man Enterprises (Count Variable)

In order to control for collinearity among the variables, only two macro‐areas are introduced into the regression model (i.e., Center and North West). Obviously, the other geographical macro‐areas are within the constant, as is year 2009. Looking at the models proposed in Table , they are all statistically significant (F‐test) and the R2 values are extremely high (between 85% and 87%). The distribution of residuals is also tested, with good results, as well as the mean VIF, which shows values equal to 1.49 (model 1), 1.43 (model 2), and 1.46 (model 3).

Also the models proposed in Table are statistically significant (F‐test), although the variation of the dependent variable explained by the model is lower (i.e., between 32% and 33%). The distribution of residuals is also tested, with good results, as well as the mean VIF (1.49 in model 1, 1.43 in model 2, and 1.46 in model 3). Obviously, as highlighted in the Appendix, there are no high values of correlation among the independent variables.

Note that the same regression models have been tested with alternative measures of judicial performance (i.e., civil and penal disposition time), confirming the collected results, but these are not presented in this manuscript for the sake of readability.

The following sub‐analysis considers only one economic proxy, that is, the average expected income of the entrepreneurs. Regression results are presented as incident rate ratios (IRR).

The models proposed in Table are statistically significant (Wald chi2 test). Note that, in this case, the dependent variable is count and it represents the total number of new firms for the three selected immigrant groups.

Discussion

The results suggest that there is a statistically significant positive relation between judicial efficiency and entrepreneurship. In other words, we cannot reject H1 that the performance of the judicial system can affect the decision to start a new business. This result is even more robust if we consider that the relation is coherent in all models. Indeed, judicial districts with higher efficiency—that is, the districts able to meet the demand for justice, taking the available courts resources into account—display a higher concentration of new enterprises if the observations are closer to the efficient frontier (i.e., score equal to 1). Moreover, comparing the two measures of entrepreneurship, there is coherence between autochthonous and immigrant entrepreneurs, although the coefficients for immigrant entrepreneurs are higher and more significant. These results are in line with the current literature, which stresses the key role of the judiciary in relation to contract enforcement, bankruptcy and property rights, and positive feedback on credit access (see the literature review section). At the same time, these results are coherent with the mixed embeddeness approach, which aims to explain patterns of entrepreneurship by linking the supply side of immigrant entrepreneurs with their specific set of resources, on the one hand, and with the opportunity structure and markets, on the other hand (Kloosterman, Rusinovic, and Yeboah Citation2016).

Note that, according to the proposed methodology, in both Tables and , a negative coefficient of the judicial variable (i.e., technical efficiency score) should be interpreted in a positive way. Indeed, considering that our benchmark is 1 and an inefficient observation is higher than 1, a negative coefficient denotes the impact on entrepreneurship moving from an efficient to an inefficient observation. In this case, we can support the hypothesis that entrepreneurship is affected not only by the ability to satisfy the demand for justice but also by the internal organization of the judicial districts. Indeed, the technical scores relate both to the ability to satisfy the demand for justice and to the courts’ internal resources (i.e., judges). This result is coherent with all the models proposed here, considering the economic effect as well as the enclave effect. Moreover, by analyzing the correlation matrix, it emerges that the technical efficiency score is not correlated with the adopted income proxies, supporting the proposed thesis and avoiding issues of endogeneity. What about the other variables?

Comparing autochthonous and immigrant entrepreneurs, even though both groups respond to the institutional environment in the same positive way, we can observe that economic conditions are statistically significant only for the latter population. This result could confirm the hypothesis that family ties are significant for autochthonous entrepreneurs. In other words, we cannot determine whether Italians entrepreneurs are driven by opportunity or necessity. At the same time, we cannot reject the hypothesis that other omitted variables, such as, for example, family ties, might affect autochthonous entrepreneurs.

Focusing on immigrant entrepreneurs, the expected duality in the economy can indeed be identified, confirming the coherence of our models and supporting the hypothesis that these immigrants are opportunity entrepreneurs. On the one hand, there is a statistically significant negative relation between entrepreneurship and unemployment. On the other hand, regarding average income, we can observe a positive relation, which is, again, statistically significant. For example, considering unemployment and the data displayed in Table , the results suggest that a 1 percent point increase in unemployment can reduce the birth rate of immigrant enterprises by 2.33 percent points. This duality is coherent with the proposed models, since both variables are representative of the economy in which the new enterprises will be set up, albeit with opposite signs. Therefore, these robust results can clarify whether the considered immigrants are opportunity or necessity entrepreneurs. Indeed, based on our evidence, we cannot reject the hypothesis that the entrepreneurs are driven by opportunity to make profit on the formal market thanks to their abilities, since there is a positive correlation with these economic proxies.

However, there is heterogeneity among immigrant groups. Indeed, taking the sub‐analysis into account and given that the other variables are held constant in the model, by increasing the income variable by one unit, the estimated rate ratio would be 89 times greater for new Albanian enterprises and 178 times greater for new Romanian enterprises. In both cases, these incident rates are statistically significant (p‐value < .01). Considering the Chinese enterprises, the rate is statistically significant (p‐value < .1), but its degree is dramatically lower (3.569).

For what concerns the geographical macro‐areas, a statistically significant relation can be observed between entrepreneurship and the Center macro‐area. A positive relation can also be observed in the North West of Italy, but it is not statistically significant in all models. Finally, taking the years dummy variable into account, we can detect an increase in the birth rate of enterprises in 2006 and 2007 but a decrease in 2008. However, the coefficients are not statistically significant in all cases. The result concerning the dummy variable for 2007 might be affected by the fact that Bulgaria and Romania joined the EU in that year. Although the results for Bulgaria are not significant, new Romanian enterprises in the considered period were 59% of the European ones (see the table in the Appendix). The population density is positive but not significant in all models, which is coherent with the types of businesses set up by these immigrants, as they specialize in the services and construction sectors. What about the enclave effect?

The proposed sub‐analysis highlights the strong and positive relation between the enclave effect and entrepreneurship, as suggested in the literature review. Indeed, judicial districts with higher concentrations of immigrants from a specific foreign group display a higher number of new one‐man companies set up by entrepreneurs from that foreign group. However, significant differences among the three immigrant groups emerge. Both Albanian and Romanian entrepreneurs are clearly affected by judicial efficiency (i.e., statistically significant coefficients in both cases), whereas the impact on the Chinese community is not so clear (i.e., coefficient not statistically significant). At the same time, Chinese entrepreneurs are strongly affected by the presence of an enclave. How can these results be explained?

On the one hand, according to Quassoli (Citation1999), Chinese entrepreneurial activities rely on the presence of a close‐knit community, which supports entrepreneurs by supplying ethnic workers and accepting their exploitation. On the other hand, as suggested by Hofstede (Citation1993), the enforcement of contracts and property rights does not appear to be decisive for Chinese entrepreneurs due to their risk attitude. Indeed, the Chinese score very low in uncertainty avoidance (30 points), while the scores for the Romanians and Albanians are very high (respectively, 90 and 70 points).Footnote45 This means that the Chinese are greater risk‐takers, while the other two groups are risk‐avoiders—that is to say, judicial efficiency is a crucial factor for the Albanians and Romanians while for the Chinese it is not. However, this is just one potential explanation. The Chinese may attach greater value to their internal force (i.e., the enclave effect) because of family connectedness and co‐ethnic business dealings. Furthermore, the Chinese may simply embed in ways different from those of the Albanians and Romanians, so that differences in judicial efficiency are less apparent to them or less important than the enclave element.

Based on this background, the collected results are perfectly coherent and they confirm the robustness of the proposed models.

Conclusions

Judicial systems serve important purposes not only in upholding social values but also in determining economic performance. Well‐functioning judiciaries guarantee the security of property rights and the enforcement of contracts, and they also have a significant impact on the cost of loans (Bae and Goyal Citation2009; Laeven and Majnoni Citation2005). The security of property rights reinforces incentives to save and invest, by protecting returns from these activities and, consequently, increasing the national GDP (Bianco, Jappelli, and Pagano Citation2005; Djankov et al. Citation2008). Indeed, the good enforcement of contracts stimulates agents to enter into economic relationships by reducing opportunistic behavior and transaction costs. Such circumstances positively impact on growth through various channels; they promote competition, foster specialization in more innovative industries, and contribute to the development of financial and credit markets. Moreover, according to the mixed embeddedness approach, judicial efficiency might significantly affect immigrant entrepreneurship and integration in the host country.

As stressed by Jones et al. (Citation2014) and Barrett and Vershinina (Citation2017), the social capital must be placed in its proper context, that is to say, the entrepreneurial initiatives of immigrants have to be grounded in more than one sphere of influence instead of solely in their own ethnic network (Kloosterman Citation2010). In this work, referring to the idea of opportunity structures suggested by the mixed embeddedness approach, the authors have tried to shed new light on the relation between entrepreneurship and the judiciary focusing on a specific case study, that is, immigrant entrepreneurship in Italy between 2006 and 2008. The concept of mixed embeddedness has been investigated, linking the resources of (aspiring) migrant entrepreneurs with the specific local opportunity structure due to the efficient enforcement of civil and penal law.

More precisely, this work analyzes the relation between judicial efficiency and entrepreneurship in Italy by applying the Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) at the district level. We obtain a technical efficiency score, intended as the district's ability to maximize the number of cases settled, taking the resources of first instance courts (judges) and their workload into account (i.e., incoming and pending cases at the beginning of each year). Then, we use the calculated efficiency measure as explanatory variable accounting for entrepreneurship, focusing in particular on immigrant entrepreneurs. The hypothesis of a positive relation between justice and entrepreneurship is also tested against the possibility that the rate of immigrant entrepreneurs might be determined by other local external factors (i.e., cultural, social, and economic), or by the size of their immigrant group within a given geographical unit. Moreover, we try to determine whether differences between immigrant and autochthonous entrepreneurs exist.

Our results confirm the positive relation between the judiciary and entrepreneurship, highlighting the suggested opportunity structure due to the efficiency of judicial enforcement institutions. Moreover, they hint at the crucial role of the judiciary in helping the integration of immigrants into the formal market, where they have to assimilate and apply the local (legal) rules to carry out their entrepreneurial activities. This might be a preliminary key step in the process of social and cultural integration in the host country. This result is significant for the foreign groups coming from two key European countries, that is, Albania, which is a candidate for accession to the EU, and Romania, one of the most recent EU members.

This point is particularly significant if we consider current legality issues in Italy and how they affect immigrants, as highlighted by Quassoli (Citation1999). Indeed, the efficiency of the judicial system can be an opportunity structure, influencing decisions about whether to start a new business and about whether to remain within the confines of the law (Kloosterman Citation2010). The main risk of an inefficient judicial system is that entrepreneurial activities might be started within the gray economy (i.e., informal and/or criminal market), thus respecting the rules of that market instead of the legal one. Obviously, this work analyzes only one side of this phenomenon, since it focuses on legal immigrant entrepreneurship. In other words, there certainly are a number of immigrant entrepreneurs who conduct their business outside the law (hence, not captured in our estimation), on the informal/criminal market (Quassoli Citation1999). However, this cannot but reinforce our hypothesis that judicial efficiency is a driver of immigrant integration on the formal market, since our results show a clear and positive relation between judicial efficiency and immigrant entrepreneurship, despite a certain level of heterogeneity among the different groups. Indeed, a different attitude toward integration has been detected in the Chinese community. Policy makers should consider these results, evaluating the opportunity to implement specific targeted policies in order to improve this attitude and the consequent integration of immigrant groups into our society. This should be a preliminary, but necessary, step in the process to facilitate social and cultural integration in the host country.

Our results are interesting and they can, at least partially, fill the current knowledge gap, but the analysis proposed here can certainly be improved. The main limit of our investigation is the size of the adopted sample, since our study is clearly affected by data availability. Moreover, the choice to adopt an approach based on judicial rather than administrative geography has led to the aggregation of data at the second instance district level. If data become available, it might be useful to perform an empirical analysis at the micro level—for example, at the level of first instance courts—with 165 observations per year instead of the current 26 observations. This might confirm the suggested scenario and, at the same time, shed new light on immigrant entrepreneurship, the gray economy, and judicial performance. Another improvement might come from the aforementioned double analysis, that is, on immigrant entrepreneurship in both the formal economy and the gray economy, highlighting main differences and examining the key role of the judiciary in the integration of immigrants. Finally, a potential improvement might consist in further investigating the suggested indirect embeddedness of ethnic groups, as well as ethnic and business networks. A specific survey can be implemented, collecting data that might prove fundamental in strengthening the proposed theories and shedding new light on immigrant entrepreneurs, mixed embeddedness, and the role of ethnic enclaves in the integration of these new citizens in Western countries.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Greta Falavigna

Greta Falavigna is with the Research Institute on Sustainable Economic Growth, National Research Council of Italy, Moncalieri, Italy.

Roberto Ippoliti

Roberto Ippoliti is with the University of Turin, Department of Management, Turin, Italy.

Alessandro Manello

Alessandro Manello is with the Research Institute on Sustainable Economic Growth, National Research Council of Italy, Moncalieri, Italy.

Notes

24. Others works have focused on institutional variables that might affect entrepreneurship such as, for example, taxation (Poutziouris et al. Citation2000; Fölster Citation2002), protection of intellectual property rights (Lerner Citation2002; Bigus Citation2006), and labor market regulation (Lodovici Citation1999; Parker and Robson Citation2003).

25. As explained by Kloosterman, Van der Leun, and Rath (Citation1999), the informal economy concerns activities which are not intrinsically illegal according to national law (e.g., food or clothing), but in which production and exchange escape legal regulations. Obviously, even though in some cases the border between them is not so clear, the criminal economy concerns activities that, according to national law, are expressly illegal. Both the courts and the police are crucial in interpreting the law more or less strictly and in defining the border between criminal and informal activities.

26. For an analysis of immigrant entrepreneurship and/or work in other illegal European markets, see Rezaei, Goli, and Dana (Citation2013) for the case of Belgium and Rezaei, Goli, and Dana (Citation2014) for the case of Austria.

27. Although this work does not focus on immigrant integration, that is, social and cultural assimilation in the host country, we can consider self‐employment within the formal economy as a key preliminary step in that process, since it implies acceptance of the (legal) rules of that market.

28. Clearance rate is the ratio given by the number of settled cases and the number of incoming cases (CEPEJ Citation2012).

29. See Hughes (Citation2002), Smith and Street (Citation2005), and Simpson (Citation2009), for a deeper analysis of the main approaches to estimating government outputs and productivity measurements.

30. The one‐stage DEA is aimed at estimating and analyzing efficiency, while the two‐stage DEA is aimed at using the estimated scores to study the determinants of inefficiency.

31. The Italian court system is divided into three main tiers and one lowest level. At the lowest level are the so‐called justices of the peace (i.e., Giudici di Pace), with specific civil and criminal competences. The first tier includes first instance courts (i.e., Tribunali Ordinari) which, gathering together the aforementioned justices of the peace, are part of the first instance districts (i.e., Circondari Giudiziari). In the considered period (2006–2009), there were 165 first instance judicial districts. The second tier comprises 26 second instance districts (i.e., Distretti di Corte di Appello), gathering together a variable number of first instance districts and responsible for appeals against first instance judgments. The court of last resort is the Supreme Court of Cassation (i.e., Corte Suprema di Cassazione).

32. For an in‐depth description of DEA, see also Charnes, Cooper, and Rhodes (Citation1978), Färe and Grosskopf (Citation1996), and Coelli, Rao Prasada, and Battese (Citation1998).

33. For a detailed analysis of judges and their key role in courts efficiency, see Cooter (Citation1983), Posner (Citation1993) and Beenstock and Haitovsky (Citation2004).

34. The authors are not able to disaggregate the judges’ civil and penal activities. In other words, the number of judges working in every court is available but it is not possible to determine whether they work on penal or civil cases. Note that, in the period considered, there are 165 first instance courts in Italy and in many of them there are mixed sections, which means judges have to deal with both civil and penal cases.

35. Note that the observations with place of birth recorded as Czechoslovakia, Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), and Yugoslavia are not considered, since it is not possible to assign them to the corresponding nations of today. Moreover, in 0.47 percent of the cases the place of birth of the entrepreneur is not reported; hence, this small share of enterprises is not considered in the descriptive statistics.

36. In economics, BRIC is a grouping acronym referring to the countries of Brazil, Russia, India, and China, which are all deemed to be at a similar stage of newly advanced economic development.

37. Moreover, these countries are truly significant from a European perspective, since they are currently a candidate country for EU accession (Albania), a new member state of the EU (Romania), and the most important BRIC country (China).

38. Three case studies are considered: Romanian, Chinese, and Albanian ethnic groups in Italy. This variable is adopted in the sub‐analysis.

39. Note that the average income, which considers the tax base at the local level (i.e., Addizionale IRPEF), is revaluated taking the estimated inflation into account (i.e., ISTAT values).

40. Also in this case, the average income, based on business sector analyses (i.e., Studi di settore), is revaluated taking the estimated inflation into account (i.e., ISTAT values).

41. The Ministerial data set about permits to stay (i.e., Permessi di soggiorno) is adopted, taking both EU and non‐EU immigrants into account.

42. The MEF dataset about business sector analyses (i.e., Studi di Settore) is adopted, focusing on one‐man enterprises.

43. The choice is clearly affected by the key explanatory variables on the national judicial system, which are estimated in both cases considering data about single years, hence not comparable at the panel level. This is extremely significant taking technical efficiency scores into account (see Simar and Wilson Citation2007).

44. The deviance goodness‐of‐fit test and the Pearson goodness‐of‐fit test tell us that, given the model, we can reject the hypothesis that these data are Poisson distributed (p‐value < .000). Therefore, the NB model is more appropriate than a Poisson model.

45. For a comparative analysis tool, see this link: http://geert-hofstede.com

References

- Acs, Z. J., S. Desai, and J. Hessels (2008). “Entrepreneurship, Economic Development and Institutions,” Small Business Economics 31, 219–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9135-9.

- Alvarez, R. M., Jr. (1990). “Mexican Entrepreneurs and Markets in the City of Los Angeles: A Case of an Immigrant Enclave,” Urban Anthropology and Studies of Cultural Systems and World Economic Development 19(1–2), 99–124.

- Armington, C., and Z. J. Acs (2002). “The Determinants of Regional Variation in New Firm Formation,” Regional Studies 36(1), 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400120099843.

- Armour, J., and D. Cumming (2008). “Bankruptcy Law and Entrepreneurship,” American Law and Economics Review 10(2), 303–350. https://doi.org/10.1093/aler/ahn008.

- Bae, K. H., and V. K. Goyal (2009). “Creditor Rights, Enforcement, and Bank Loans,” Journal of Finance 64(2), 823–860. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2009.01450.x.

- Banker, D. R., A. Charnes, and W. W. Cooper (1984). “Some Models for Estimating Technical and Scale Inefficiencies in Data Envelopment Analysis,” Management Science 30(9), 1078–1092. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.30.9.1078.

- Barrett, G., T. Jones, and D. Mcevoy (2001). “Socio‐Economic and Policy Dimensions of the Mixed Embeddedness of Ethnic Minority Business in Britain,” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 27(2), 241–258.

- Barrett, G., T. Jones, D. Mcevoy, and C. Mcgoldrick (2002). “The Economic Embeddness of Immigrant Enterprise in Britain,” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552550210423697.

- Barrett, R., and N. Vershinina (2017). “Intersectionality of Ethnic and Entrepreneurial Identities: A Study of Post‐War Polish Entrepreneurs in an English City,” Journal of Small Business Management 55(3), 430–443. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12246.

- Basu, A., and E. Altinay (2002). “The Interaction Between Culture and Entrepreneurship in London's Immigrant Businesses,” International Small Business Journal 20(4), 371–393. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242602204001.

- Bates, T. (1999). “Existing Self‐Employment: An Analysis of Asian Immigrant Owned Small Business,” Small Business Economics 13, 171–183. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008110421831.

- Baycan‐levent, T., P. Nijkamp, and M. Sahin (2009). “New Orientations in Ethnic Entrepreneurship: Motivation, Goals and Strategies of New Generation Ethnic Entrepreneurs,” International Journal of Foresight and Innovation Policy 5, 83–111. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJFIP.2009.0221.

- Beck, T., A. Demirguc‐kunt, and V. Maksimovic (2006). “The Influence of Financial and Legal Institutions on Firm Size,” Journal of Banking and Finance 30, 2995–3015.

- Beenstock, M., and Y. Haitovsky (2004). “Does the Appointment of Judges Increase the Output of the Judiciary?” International Review of Law and Economics 24, 351–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irle.2004.10.006.

- Bergmann, H., C. Hundt, and R. Sternberg (2016). “What Makes Student Entrepreneurs? On the Relevance (and Irrelevance) of the University and the Regional Context for Student Start‐Ups,” Small Business Economics 47, 53–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9700-6.

- Bianco, M., T. Jappelli, and M. Pagano (2005). “Courts and Banks: Effects of Judicial Enforcement on Credit Markets,” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 37(2), 223–244. https://doi.org/10.1353/mcb.2005.0021.

- Bigus, J. (2006). “Staging of Venture Financing, Investor Opportunism, and Patent Law,” Journal of Business Finance and Accounting 33, 939–960. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5957.2006.00005.x.

- Block, J., and P. Sandner (2009). “Necessity and Opportunity Entrepreneurs and Their Duration in Self‐Employment: Evidence from German Micro Data,” Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade 9(2), 117–137.

- Blume, K., M. Ejrnæs, H. S. Nielsen, and A. Würtz (2009). “Labor Market Transitions of Immigrants with Emphasis on Marginalization and Self‐Employment,” Journal of Population Economics 22(4), 881–908.

- Bohon, S. (2001). Latinos in Ethnic Enclaves. New York: Garland Publishing.

- Brzozowski, J., M. Cucculelli, and A. Surdej (2014). “Transnational Ties and Performance of Immigrant Entrepreneurs: The Role of Home‐Country Conditions,” Entrepreneurship and Regional Development: An International Journal 26(7–8), 546–573. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2014.959068.

- Burkart, M., and T. Ellingsen (2002). “In‐Kind Finance,” CEPR, Discussion Paper No. 3536.

- Caliendo, M., F. Fossen, and A. S. Kritikos (2014). “Personality Characteristics and the Decisions to Become and Stay Self‐Employed,” Small Business Economics 42, 787–814. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9514-8

- Cameron, A. C., and P. K. Trivedi (2013). Regression Analysis of Count Data, 2nd ed. Econometric Society Monograph No. 53. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Carmignani, A., and S. Giacomelli (2010). “Too Many Lawyers?” Bank of Italy ‐ Working Paper No. 745.

- Castelar pineiro, A., and C. Cabral (2001). “Credit Markets in Brazil: The Role of Judicial Enforcement and Other Institutions,” in Defusing Default: Incentives and Institutions. Ed. M. Pagano. Washington, DC: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- CEPEJ (2012). “Evaluation of European Judicial Systems,” CEPEJ Report, European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ).

- Chaparro, P. F., and S. J. Jimenez (1996). “An Assessment of the Efficiency of Spanish Courts Using DEA,” Applied Economics 28, 1391–1403. https://doi.org/10.1080/000368496327651.

- Charnes, A., W. W. Cooper, and E. Rhodes (1978). “Measuring the Efficiency of Decision Making Units,” European Journal of Operational Research 2, 429–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-2217(78)90138-8.

- Chemin, M. (2009). “The Impact of the Judiciary on Entrepreneurship: Evaluation of Pakistan's “Access to Justice Programme,” Journal of Public Economics 93, 114–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2008.05.005.

- Christensen, R. K., and J. Szmer (2012). “Examining the Efficiency of the U.S. Courts of Appeals: Pathologies and Prescriptions,” International Review of Law and Economics 32(1), 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irle.2011.12.004.

- Ciavarella, M. A., A. K. Buchholtz, C. M. Riordan, R. D. Gatewood, and G. S. Stokes (2004). “The Big Five and Venture Survival: Is There a Linkage?” Journal of Business Venturing 19, 465–483.

- Claessens, S., and L. F. Klapper (2009). “Bankruptcy around the World: Explanation of Its Relative Use,” American Law and Economics Review 7(1), 253–283.

- Clark, K., and S. Drinkwater (2002). “Enclaves, Neighbourhood Effects and Employment Outcomes: Ethnic Minorities in England and Wales,” Journal of Population Economics 15(1), 5–29.

- Clark, K., and S. Drinkwater (2010). “Patterns of Ethnic Self‐Employment in Time and Space: Evidence from British Census Microdata,” Small Business Economics 34(3), 323–338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9122-1.

- CNEL Report (2011). “Il Profilo Nazionale Degli Imprenditori Immigrati in Italia,” Consiglio Nazionale Economia e Lavoro (CNEL), Rome.

- Coelli, T., D. S. Rao prasada, and G. E. Battese (1998). An Introduction to Efficiency and Productivity analysis. Noerwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Cook, W. D., and L. M. Seiford (2009). “Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) – Thirty Years On,” European Journal of Operational Research 192, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2008.01.032.

- Cooter, R. D. (1983). “The Objectives of Private and Public Judges,” Public Choice 41, 107–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00124053.

- Cramer, J. S., J. Hartog, N. Jonker, and C. M. Van Praag (2002). “Low Risk Aversion Encourages the Choice for Entrepreneurship: An Empirical Test of a Truism,” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 48, 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-2681(01)00222-0.

- Cristini, M., R. A. Moya, and A. Powell (2001). “The Importance of an Effective Legal System for Credit Markets: The Case of Argentina,” in Defusing Default: Incentives and Institutions. Ed. M. Pagano. Washington, DC: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Daraio, C., and L. Simar (2007). Advanced Robust and Nonparametric Methods in Efficiency Analysis: Methodology and Application. Berlin: Springer.

- Deyneli, F. (2012). “Analysis of Relationship Between Efficiency of Justice Services and Salaries of Judges with Two‐Stage DEA Method,” European Journal of Law and Economics 34, 477–493. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-011-9258-3.

- Di Vita, G. (2010). “Production of Laws and Delays in Court Decisions,” International Review of Law and Economics 30(3), 276–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irle.2010.03.006.

- Djankov, S., O. Hart, C. Mcliesh, and A. Shleifer (2008). “Debt Enforcement Around the World,” Journal of Political Economy 116, 1105–1149. https://doi.org/10.1086/595015.

- Dougherty, S. M. (2014). “Legal Reform, Contract Enforcement and Firm Size in Mexico,” Review of International Economics 22(4), 825–844. https://doi.org/10.1111/roie.12136.

- Fabbri, D. (2001). “Legal Institutions, Corporate Governance and Aggregate Activity: Theory and Evidence,” CSEF, Working Paper No. 72.

- Fabbri, D. (2010). “Law Enforcement and Firm Financing: Theory and Evidence,” Journal of the European Economic Association 8(4), 776–816. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-4774.2010.tb00540.x.

- Fabbri, D., and M. Padula (2001). “Judicial Costs and Household Debt,” CSEF Working Paper, University of Salerno.

- Fairlie, R. W. (2008). “Estimating the Contribution of Immigrant Business Owners to the U.S. Economy,” Working Paper at SBA Office of Advocacy.

- Fairlie, R. W., and W. Holleran (2012). “Entrepreneurship Training, Risk Aversion and Other Personality Traits: Evidence from a Random Experiment,” Journal of Economic Psychology 33, 366–378.

- Falavigna, G., R. Ippoliti, A. Manello, and G. Ramello (2015). “Judicial Productivity, Delay and Efficiency: A Directional Distance Function (DDF) Approach,” European Journal of Operational Research 240, 592–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2014.07.014.

- Färe, R., and S. Grosskopf (1996). Intertemporal Production Frontiers: With Dynamic DEA. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Farrell, M. J. (1957). “The Measurement of Productive Efficiency,” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 120(3), 253–290.

- Feld, L. P., and S. Voigt (2003). “Economic Growth and Judicial Independence: Cross‐Country Evidence Using a New Set of Indicators,” European Journal of Political Economy 19, 497–527.

- Fölster, S. (2002). “Do Lower Taxes Stimulate Self‐Employment?” Small Business Economics 19(2), 135–145. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016200800982.

- Fossen, F. M. (2014). “Personal Bankruptcy Law, Wealth, and Entrepreneurship—Evidence from the Introduction of a “Fresh Start” Policy,” American Law and Economics Review 16(1), 269–312.

- Gabe, T. M. (2003). “Local Industry Agglomeration and New Business Activity,” Growth and Change 34(1), 17–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2257.00197.

- Garcìa‐posada, M., and J. S. Mora‐sanguinetti (2015). “Does (Average) Size Matter? Court Enforcement, Business Demography and Firm Growth,” Small Business Economics 44, 639–669. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9615-z.

- Giacomelli, S., and C. Menon (2013). “Firm Size and Judicial Efficiency in Italy: Evidence from the Neighbour's Tribunal,” Bank of Italy ‐ Working Paper No. 898.

- Hofstede, G. (1993). “Cultural Constraints in Management Theories,” Academy of Management Executive 7(1), 81–94.

- Hoppe, M. (2016). “Policy and Entrepreneurship Education,” Small Business Economics 46, 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-015-9676-7.

- Hughes, A. (2002). “Guide to the Measurement of Government Productivity,” International Productivity Monitor 5(Fall), 64–77.

- Ippoliti, R. (2014). “The Competitiveness of the Market for Legal Services and Judicial Efficiency,” Italian Journal of Public Economics 2, 53–90. https://doi.org/10.3280/EP2014-002003.

- Ippoliti, R. (2015). “The Reform of Judicial Geography: Technical Efficiency and Demand of Justice,” Italian Journal of Public Economics 2, 91–124. https://doi.org/10.3280/EP2015-002003.

- Ippoliti, R., A. Melcarne, and G. Ramello (2015a). “The Impact of Judiciary Efficiency on Entrepreneurial Action: A European Perspective,” Economic Notes 44(1), 57–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecno.12030.

- Ippoliti, R., A. Melcarne, and G. Ramello (2015b). “Judicial Efficiency and Entrepreneurs’ Expectations on the Reliability of European Legal Systems,” European Journal of Law and Economics 40, 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-014-9456-x.

- Ippoliti, R., and M. Vatiero (2014). “An Analysis of How 2002 Judicial Reorganization Has Impacted on the Performance of the First Instance Courts (Preture) in Ticino,” Working Paper Università della Svizzera Italiana, IdEP Economic Papers 2014/08.

- Jaffee, A. (1985). “Mortgage Foreclosure Law and Regional Disparities in Mortgage Financing Costs,” Working Paper No 85–80, Pennsylvania State University.

- Jones, T., M. Ram, P. Edwards, A. Kiselinchev, and L. Muchenje (2014). “Mixed Embeddedness and New Migrant Enterprise in the UK,” Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 26(5–6), 500–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2014.950697.

- Kittelsen, S. A. C., and F. R. Førsund (1992). “Efficiency Analysis of Norwegian District Courts,” Journal of Productivity Analysis 3, 277–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00158357.

- Kloosterman, R. (2010). “Matching Opportunities with Resources: A Framework for Analysing (Migrant) Entrepreneurship from a Mixed Embeddedness Perspective,” Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 22(1), 25–45.

- Kloosterman, R., and J. Rath (2001). “Immigrant Entrepreneurs in Advanced Economies: Mixed Embeddedness Further Explored,” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 27(2), 189–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830020041561.

- Kloosterman, R., J. Van der Leun, and J. Rath (1999). “Mixed Embeddedness: (In)Formal Economic Activities and Immigrant Businesses in the Netherlands,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 23(2), 252–266. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.00194.

- Kloosterman, R., K. Rusinovic, and D. Yeboah (2016). “Superdiverse Migrants—Similar Trajectories? Ghanaian Entrepreneurship in the Netherlands Seen from a Mixed Embeddedness Perspective,” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42(6), 913–932. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2015.1126091.