Abstract

This paper reports on a three‐country comparative study examining the internationalization of family winemakers in distinct regional wine clusters of Argentina, Chile, and New Zealand. In‐depth interviews were conducted with owner–operators, to understand the drivers and barriers to internationalization of their businesses. Key findings reveal that while size and age are not determinants of the ability or propensity to export wine, the existence of an independent industry body has a positive impact and greatly speeds up the internationalization process, providing an effective route for small firms to establish their very often, relatively unknown brand(s) in lucrative foreign markets.

Introduction

Comparing California's Silicon Valley with Route 128 in Massachusetts, Saxenian (Citation1994) observed that the former thrived while the latter declined during the 1990s; the explanation given was that Silicon Valley developed a cooperative, although decentralized, industrial system while the other was dominated by self‐sufficient corporations. Interest subsequently escalated in the nature, structure, and functioning of regional clusters from academics, business owners, development agencies, and governments (De Propris and Lazzeretti Citation2009; Felzensztein, Gimmon, and Carter Citation2010). In parallel, the late 20th century (Wright Citation1999) and early 21st witnessed increased interest in the internationalization of small firms (Dana Citation2004). Our interest is at the intersection of these two streams. What are relevant issues when clustered small firms seek to internationalize?

Research has taken different angles to study what contributes to the internationalization of SMEs. Brasch (Citation1981) focused on organizational structures for small firms deciding to export. Becker and Porter (Citation1983) identified export‐trading companies as helping small businesses. Turner, Timmins, and Bhatt (Citation1983) suggested banks had a major role to play and Reid (Citation1985) argued that size was an important and complex variable influencing export activity. Namiki (Citation1988) emphasized the importance of export strategy. Over time, much empirical research emerged about firm size and export behavior in established markets of the Northern Hemisphere (Ali and Swiercz Citation1991). Oviatt and McDougall (Citation1994) discussed international new ventures, ranging from London's East India Company to Ford—all based in the Northern Hemisphere. Madsen and Servais (Citation1997) focused on born‐globals in Australia, Denmark, France, Italy, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States. Hart and Tzokas (Citation1999) explored the relationship between exporting marketing research and export performance; their findings in the United Kingdom suggest that export performance was affected by the nature of information elements collected, the research vehicle and the use of these. Moen and Servais (Citation2002) investigated the export behavior of Danish, French, and Norwegian SMEs. Tang (Citation2011) noted that networking helped Chinese SMEs to internationalize. Studying Brazilian exporters, Boehe (Citation2013) found that access to local network resources, facilitated by a firm's membership in a group, is a good predictor and that collaboration intensity was linked to export intensity. D'Angelo, Majocchi, and Buck (Citation2016) emphasized that while some family SMEs are inert local firms, others are dynamic and international; that study sought to explain the scope of internationalization among family SMEs.

The literature on clusters and industrial districts clarified inherent advantages; Piore and Sabel (Citation1984) on flexible specialization is one example. The Italian school, with Brusco (Citation1986) and Becattini (Citation1990), clarified advantages of colocalization and coopetition, based on mutual trust and tacit norms, facilitating the circulation of information that could be relevant for competitive aims. Building on Brusco's (Citation1986) study of industrial districts and contributing to the canonical district model, Harrison (Citation1992) discussed the existence of a cooperative climate in Italian industrial districts. Rabellotti (Citation1995) also focused on industrial districts, comparing footwear districts in Italy and Mexico; this preceded Porter (Citation1997). Bresnahan and Gambardella (Citation2004) studied high‐tech clusters in India, Ireland, Israel, Scandinavia, Taiwan, and the United States. Ketels and Sölvell (Citation2006) examined clusters across Eastern Europe. Chetty and Agndal (Citation2008) focused on interpersonal and interorganizational networks in Auckland's boat‐building industrial district; they showed how interpersonal networks can be transformed into interorganizational networks, and vice versa, strengthening the district and learning to balance competition with cooperation. Other contributions include Camuffo and Grandinetti (Citation2011) and Furlan and Grandinetti (Citation2011). Cainelli, Mazzanti, and Montresor (Citation2012) subsequently focused on the role of inter‐firm network relationships, agglomeration economies, and internationalization strategies in northeastern Italy. Examining the Italian experience in the context of globalization, De Marchi and Grandinetti (Citation2014) observed and discussed the decline of the Marshallian model that dominated Italy until the recent past.

Most related research has focused on developed countries of the Northern Hemisphere. Exceptions include Blandy's (Citation2000) reference to the wine‐making cluster in South Australia, Chetty and Campbell‐Hunt's (Citation2004) study of internationalization among 16 New Zealand firms, Hall's (Citation2005) study of New Zealand wine cluster and network development, Chetty and Agndal's (Citation2008) study of Auckland's boat‐building industrial district, the Dana and Winstone (Citation2008) study of a New Zealand wine cluster, and Brown, McNaughton, and Bell (Citation2010) about the electronics cluster in Christchurch; also relevant are Dana et al. (Citation2013) and Felzensztein et al. (Citation2014). While there is agreement in the literature that clusters provide benefits to firms, especially value chain inputs and more general aspects of the production process (Mackinnon, Chapman, and Cumbers Citation2004), the relative contribution of regional clusters to new ventures and business growth is controversial (Fritsch and Mueller Citation2004) and may vary over time and from country to country (Acs, Desai, and Hessels Citation2008), presenting a lacuna and providing conflicting evidence on the benefits and positive externalities associated to regional clusters (Felzensztein and Gimmon Citation2009). In response to an increasing interest in comparative studies (Gupta et al. Citation2011), we explore drivers and barriers for internationalization activities of small (mostly family‐owned) firms in three important wine clusters located in Argentina, Chile, and New Zealand as shown in Figure 1. Although the first two countries share a language, each of these three exposes its firms to a unique combination of economic turbulence, exchange rate fluctuations, local government initiatives (Schmiedeberg Citation2010), and export promotion incentives (Moini Citation1998).

Figure 1. Three Southern Hemisphere Wine Regions [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Our contribution arises from the fact that the wine industry provides an interesting example of clustered firms, and helps to further our understanding of the function of regional districts (Johannisson et al. Citation2007). It has been shown that the New World wine industry is prone to geographic clustering with Canada (Mytelka and Goertzen Citation2003), Chile (Giuliani and Bell Citation2005), New Zealand (Dana and Winstone Citation2008), the United States (Porter Citation1998; Porter and Bond Citation2004), and others, seen as suitable regions to study this phenomenon, especially in the Southern Hemisphere (Felzensztein et al. Citation2014). Wine firms located in clusters benefit from regional recognition or branding and therefore a high level of inter‐firm cooperation in the quest to achieve maximum potential, particularly in foreign markets (Felzensztein et al. Citation2014).

Focusing on the wine sector, our study examines export enablers, such as cooperative initiatives (Bengtsson and Kock Citation1999; Brandenburger and Nalebuff Citation1996) and government support (Lang Citation1977; Moini Citation1998; Weaver, Berkowitz, and Davies Citation1998) to overcome SME export barriers (Leonidou Citation2004; Suirez‐Ortega Citation2003). We chose an inductive multiple‐case approach aiming to develop an understanding of these issues (Eisenhardt and Graebner Citation2007) in specific geographical settings. Our sample was composed of small firms committed to exporting, from three well‐known and established New World wine regions in the Southern Hemisphere. Our qualitative data, gathered by in‐depths interviews with clustered, small businesses, allows for unique, deep comparisons, noting the challenges and opportunities that surround the internationalization process, and the implications for international growth in similarly sized and sector‐based clusters. Our study thus contributes to the ongoing development of literature on small clustered family businesses overcoming export barriers (see Calabrò, Brogi, and Torchia Citation2016). Findings reveal that although age and size are not determinants of the ability or propensity to export, the existence of an independent industry body has a positive impact, accelerating internationalization, providing an effective route for small firms to establish their brand(s) abroad. Thus, our unique context contributes to a deeper understanding of and contribution to the dialog about the internationalization of clustered small businesses. Results can also contribute to public policy debates.

The paper is organized as follows. The theoretical section presents an overview of the literature on regional clusters and internationalization, with a focus on small firms. The empirical part presents 31 cases based on personal in‐depth interviews conducted in three New World countries of the Southern Hemisphere, well known for having wine business clusters, but otherwise different in many ways. Findings are then presented. The paper ends with conclusions and a discussion of limitations and future research opportunities.

Theoretical Insights: Clusters and Internationalization

Regional Clusters for Inter‐Firm Cooperation

Marshall (Citation1920) introduced the concept of industrial clusters. Astley and Fombrun (Citation1983) focused on collective aspects of interorganizational collectivities. Dollinger and Golden (Citation1992) showed that collective strategy was prevalent among small firms in fragmented industries. Simultaneously, research on clusters gained momentum with a variety of definitions arising. Swann and Prevezer defined clusters as “groups of firms within one industry based in one geographical area” (Citation1996, p. 139). Rosenfeld elaborated, “A cluster is very simply used to represent concentrations of firms that are able to produce synergy because of their geographical proximity and interdependence” (Citation1997, p. 4). Porter (Citation1998, p. 226) subsequently explained regional clusters, as being “a form of network that occurs within a geographic location, in which proximity of firms ensures a certain form of commonality and increases the frequency and impact of interactions.” An example among many is the wine cluster in Canada's Niagara Peninsula, discussed by Andersson et al. (Citation2004). In time, nuances arose. Carbonara, Giannoccaro, and McKelvey proposed, “Geographical clusters are geographically defined production systems, characterized by a large number of small and medium‐sized firms that are involved at various phases in the production of a homogeneous product family” (Citation2010, p. 21). Clusters have also been defined as “geographic concentrations of industries related by knowledge, skills, inputs, demand, and/or other linkages” (Delgado, Porter, and Stern Citation2016, p. 38). The driver industries of a region are its main source of competitive advantage (Carlsson and Mudambi Citation2003), and often exhibit a dependence on a few lead firms in the industry. A typical cluster would include producers, suppliers, intermediaries, contract service providers, third party logistics (3PL) companies, and in some cases an industry or government body (Felzensztein and Deans Citation2013).

Whereas industrial districts formerly functioned as rather closed local networks, Corò and Grandinetti (Citation2001) showed that 19 industrial districts in Italy were undergoing transition; these districts were increasingly relating with external holders of knowledge and resources, transforming a relatively closed system of exchange at local level into something else. A comprehensive collection on this is Becattini et al. (Citation2003).

Clusters arise and endure because firms that may be competing also share similar market ambitions and seek to leverage the cluster members' shared goals and aspirations by inter‐firm cooperation (Felzensztein, Gimmon, and Carter Citation2010). Zheliazkov et al. (Citation2015) noted that clusters are generally perceived as drivers of economic growth. However, to be sustainable there needs to be a balance between cooperation, cluster development, support initiatives, competitive rivalry, and differentiation. It is well known that cluster incentives and initiatives are becoming increasingly prevalent in national and local economic policies (Obadic Citation2013; Schmiedeberg Citation2010), and while some clusters are deemed to be success stories (Pillay and Uctu Citation2013), cluster policies (see: Andersson et al. Citation2004) have resulted in mixed results (Ebbekink and Lagendijk Citation2013). Nevertheless, the role of regional clusters in the development and growth of entrepreneurial and small firms continue to be and important research theme in the management literature (Audretsch Citation2001; Brown, McNaughton, and Bell Citation2010; Felzensztein, Gimmon, and Carter Citation2010; Li, de Zubielqui, and O'Connor Citation2015), as well as in the economic and geography domains (Mudambi and Santangelo Citation2016; Mudambi et al. Citation2016). To succeed, clusters must rely on heightened levels of sharing, trust, and cooperation—not easily found in all industries. Bengtsson and Kock (Citation1999) speak of coopetition as creating a healthy balance of cooperation and competition; this is elaborated upon by Park, Srivastava, and Gnywalli (Citation2014). Also relevant are marketing externalities (Brown, McNaughton, and Bell Citation2010).

Regional clusters can be seen as a form of inter‐firm alliances that leads to inter‐firm cooperation. Previous research has shed light on the inter‐firm alliance process and related challenges (Doz Citation1996; Felzensztein, Gimmon, and Carter Citation2010). This is the focus of the resource‐based view (RBV) of the firm where it is suggested that if an organization is not able to access resources it needs or to develop them by itself, it enters alliances (Katila, Rosenberger, and Eisenhardt Citation2008). Of the four types of inter‐firm relationships identified by Bengtsson and Kock (Citation1999)—coexistence, competition, collaboration, and coopetition—coopetition is the one strategy designed to achieve better performance levels (Brandenburger and Nalebuff Citation1996). It has also been linked to financial performance (Le Roy, Marques, and Robert Citation2008) and market share (Meade, Hyman, and Blank Citation2009). Bengtsson and Kock proposed a revised definition suggesting that “coopetition is a paradoxical relationship between two or more actors, regardless of whether they are in horizontal or vertical relationships, simultaneously involved in cooperative and competitive interactions” (Citation2014, p. 180).

Research on coopetitive strategies has been largely concerned with high‐tech firms (Gueguen Citation2009; Pellegrin‐Boucher and Le Roy Citation2009; Soekijad and van Wendel de Joode Citation2009). A recent body of research has increased the spectrum of application of coopetitive strategies, by focusing on airlines (Czakon and Dana Citation2013; Dana, Etemad, and Wright Citation2000); brewery, dairy, and lining industries (Bengtsson and Kock Citation2000); communications (Yami and Nemeh Citation2014); defense industries (Depeyre and Dumez Citation2009); football (Le Roy, Marques, and Robert Citation2008); health‐care services (Peng and Bourne Citation2009); insurance (Okura Citation2007); mining (Tapscott and Williams Citation2006); opera (Mariani Citation2007); reindeer herding (Dana and Guieu Citation2014); salmon farming (Felzensztein and Gimmon Citation2007); telecommunications satellites (Fernandez, Le Roy, and Gnyawali Citation2014); and coopetition within wine clusters (Dana and Granata Citation2013; Dana and Winstone Citation2008; Felzensztein and Deans Citation2013: Felzensztein et al. Citation2014).

As Dagnino and Rocco (Citation2009) suggested, the concept of coopetition does not simply emerge from coupling competition and cooperation issues, but rather from merging both concepts to form a new kind of strategic interdependence between firms, giving rise to a coopetitive system of value creation. Furthermore, the extant literature on the merits and drawbacks of coopetition or cooperative competition demonstrates that such behaviors typically arise when industry linked companies, or a cluster, sense a partial congruence of interests and that by taking a more holistic perspective the value created by the cluster can be greater than the sum of individual firms' value creating processes. Such coopetition can take many forms; sharing of market knowledge, sharing of technical skills and/or capability and jointly shared marketing initiatives such as regional branding and international or domestic trade fairs (Felzensztein and Deans Citation2013; Gray and McNaughton Citation2010). The focus of coopetition in regional clusters is also known as positive marketing externalities (Brown, McNaughton, and Bell Citation2010).

Brown, McNaughton, and Bell (Citation2010) argued that the establishment of firms at a particular location is as much a matter of historical accident as anything else. The subsequent attraction of more firms depends on the economies of scale and positive externalities; however, the importance of the geographical location may differ across industries. The firm's location in the overall specific network is what Gulati (Citation2007) called positional embeddedness. Nevertheless, it is well known in the economic geography literature that location‐bound resources might limit this kind of regional network, and that regional lock‐in may occur, leading to the decline of an entire network (Hilmersson Citation2012; O'Gorman Citation2014). This line of argument suggests, in the economic geography literature, that in the context of clusters, success and decline are multidimensional constructs (Hannigan, Cano‐Kollmann, and Mudambi Citation2015).

Recent research on regional clusters has focused on the role of new businesses in regional economic growth (Debrulle, Maes, and Sels Citation2014; McAdam et al. Citation2014), while other studies have highlighted the role of entrepreneurship and the establishment of new ventures as a mechanism for innovation, economic growth, and the creation of employment (Mudambi and Santangelo Citation2016; Thurik and Wennekers Citation2004).

Previous literature also suggested that companies that colocate and display cooperative inter‐firm links, achieve benefits as a group through a common understanding of their shared business environment (Felzensztein et al. Citation2014; Wright and Dana Citation2003). Bathelt (Citation2005) argued that this process does not always occur in every agglomeration; rather, it occurs when well‐managed and mature firms participate in well‐ordered clusters. The benefits that firms accrue from cooperative strategies have also been well researched within the literature on networks and small firms (Kuivalainen et al. Citation2012). Inter‐firms relationships that lead to more meaningful interactions between firms and then to cooperation, are defined as “complementary actions taken by firms in inter‐dependent relationships to achieve mutual outcomes over time” (Anderson and Narus Citation1990, p. 42). Such interactions require a proactive attitude toward cooperation, building of trust and commitment (Huemer, Boström, and Felzensztein Citation2009), and the construction of social capital among firms (Felzensztein, Brodt, and Gimmon Citation2014; Gulati Citation2007).

Maskell (Citation2001) suggested that the social process of inter‐firm learning and innovation works best when the partners involved are located sufficiently close to each other to allow frequent interaction and effective exchange of information and ideas. Close proximity at a regional level facilitates frequent face‐to‐face interaction and the creation of regional institutions that help reinforce an environment for inter‐firm interaction (Salazar and Holbrook Citation2007). Looking at export‐oriented firms, they can achieve cooperation results from a shared understanding of the issues and the benefits, often initiated or facilitated by a trade association (Felzensztein and Deans Citation2013).

It is well known that informal contacts play an important role in building social networks, facilitating inter‐firm cooperation and the internationalization of entrepreneurial small firms in export markets—especially those located in small export‐dependent countries such as Chile and New Zealand (Agndal, Chetty, and Wilson Citation2008; Evers and Knight Citation2008; Felzensztein Citation2016). Building inter‐firm cooperation for small and entrepreneurial firms is not always straightforward and one of the fundamental problems, especially when multiple partners are involved, is the inherent conflict of cooperation and competition between firms, especially for inter‐firm cooperation at horizontal levels. Some researchers argued that both cooperation and competition are needed for business relationships to be efficient (Ford Citation2009). Zeng and Chen (Citation2003) called the tension that this conflict generates a social dilemma, as partners have to balance competitive and cooperative agendas. Tidström (Citation2014) focused on managing such tension.

Furthermore, firms are motivated to cooperate if each potential partner has complementary goals and objectives (Felzensztein and Gimmon Citation2007; Felzensztein, Gimmon, and Carter Citation2010; Mudambi et al. Citation2016). Several industry level factors may affect inter‐firm cooperation including the stage of market development, industry specificity, export versus local market orientation, as well as competitive uncertainty of firms (Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven Citation1996; Mudambi et al. Citation2016). In response to the above literature, we can propose proposition

P1: Clustered firms will have inter‐firm cooperation for entering international markets, rather than for marketing activities in the domestic market.

Clusters for Internationalization

A reason for studying the internationalization process of cluster‐based firms is that the local environment (the cluster) should provide very specific advantages (and disadvantages as well) to firms localized within. Among competitive factors of industrial districts is the presence of firms acting as connectors between the local environment (the cluster) and global markets. Such specificities are expected to affect the internationalization process. Enterprises exert an important role in driving internationalization, both by facilitating their indirect process of export and also the direct one (piggyback effect).

Interest in internationalization of small firms and international entrepreneurship (IE) has increased rapidly due to an acceleration of globalization in the world economy (Etemad, Wright, and Dana Citation2001; Zahra and George Citation2002). IE research, which increased our knowledge of the internationalization process of small firms, introduced different measures of internationalization (Oviatt and McDougall Citation1994). Zhou, Wu, and Luo (Citation2007) argued that home‐based social networks play a mediating role in the relationship between internationalization and firm performance. Yet we still do not fully understand internationalization of small and family businesses in nontraditionally American or European contexts, neither conceptually (Casillas and Acedo Citation2013; Chetty, Johanson, and Martín Citation2014) nor empirically (Casillas and Moreno‐Menéndez Citation2014).

Early studies of internationalization focused mainly on large‐multinational‐enterprises (MNEs), from developed economies, overlooked contexts where SMEs prevail and institutional voids—the lack of institutions to foster market development—are ubiquitous (Dana, Etemad, and Wright Citation1999; Mingo Citation2013). Whether the state can assist SME internationalization and export is debatable. Spence (Citation2003) found that U.K. overseas trade missions contributed to the generation of incremental exports indirectly, by facilitating relationship building between firms. Zhang et al. (Citation2004) proposed that different types of organizational flexibility affected SMEs internationalizing from emerging markets; their sample of Chinese firms revealed that strategic flexibility had a positive effect, but that operational flexibility weakened the main effect, while structural flexibility had no significant influence on the internationalization–performance relationship. Chiarvesio and Di Maria (Citation2009) compared internationalization of Italian firms in and outside of clusters. In New Zealand, Dana, Chan, and Chia (Citation2008) found that exports were not prompted by direct government efforts but rather by relationships between producers and others in a network. Hayakawa, Lee, and Park (Citation2014) reported that export promotion agencies in Asia have had a positive and significant effect on exports. In Chile, the role of informal networks and subsequently the support from export promotions agencies prevail (Felzensztein et al. Citation2015).

Astrachan (Citation2010) observed that little was known about the internationalization of small family firms. Kontinen and Ojala (Citation2010) noted the scarcity of information about relevant strategies. Kontinen and Ojala (Citation2011) found that the creation of weak ties and informal networks helped family firms recognize international opportunities. More recently, the discipline of family business has been maturing (Sirmon Citation2014), with Fernández and Nieto (Citation2014) providing an overview of the internationalization of family business. Yet writing about the internationalization of family firms from China, Liang, Wang, and Cui noted, “Empirical evidence on this question is inconclusive” (Citation2014, p. 126).

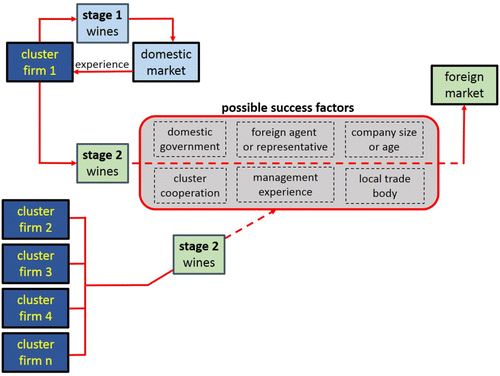

Recent literature on the internationalization of family firms (Calabrò, Brogi, and Torchia Citation2016; Kontinen and Ojala Citation2012a) and the internationalization and international marketing of clustered firms from the Southern Hemisphere (Felzensztein et al. Citation2014) contributed to the debate on the challenges and constraints of family businesses going international and whether incoming generations' involvement impacts the decision to exploit and explore international opportunities. The IE literature also suggests that early and accelerated international market entry can be enhanced by stronger institutional development in terms of market internationalization and competition in the home country (Etemad Citation2016; Madsen and Servais Citation1997; Oviatt and McDougall Citation2005). This is because the stronger the development of institutions, the stronger the competitive pressures on the individual firm and, therefore, the motivation to internationalize increases. Since the competitive intensity of a highly competitive domestic market is often similar to that of international markets, new ventures and small firms are able to compete in international markets straight away. Relating to this, prior empirical research on larger public‐listed firms showed that firms that originated in countries with strong market institutions tend to be more competitive abroad, particularly in countries with less competitive market conditions (Del Sol and Kogan Citation2007). Thus, we can suggest that the development of different kinds of and behaviors, as shown in Figure 2, as drivers to a highly competitive environment at the home country, can facilitate the internationalization of small family firms located in regional clusters. This leads to this proposition:

P2: Cluster institutions, such as a trade organization, will facilitate the internationalization of clustered firms.

Figure 2. Small Firm Internationalization [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Methodology

Research Method

It is suggested that the best thing about small family firms is their sense of ownership (The Economist Citation2015) and that this factor is crucial in our sample of small family business owners. In order to explore our two propositions about the internationalization of clustered small businesses, we opted for a qualitative approach (Reay and Zhang Citation2014), with an inductive design, using a multiple case study methodology (Yin Citation1994). Dana (Citation1994) and Melin, Nordqvist, and Sharma (Citation2014) recommended the use of such a methodology particularly for international research involving entrepreneurial businesses. Qualitative research based on interviews and the narrative data of case studies are needed in the case of small family businesses, since in‐depth research provides opportunities through richness of contextualized cases (Dawson and Hjorth Citation2012). Patmore and Haddoud (Citation2015) used such a qualitative approach in their study of drivers and barriers facing SMEs wishing to internationalize.

Sample, Data Gathering, and Analysis

We elected to conduct our qualitative study with interviews in three countries: Argentina, Chile, and New Zealand, which are among the leading producers and exporters of wine, located in the Southern Hemisphere. One common characteristic of the firms interviewed in these three countries is that they are all entrepreneurial family‐owned or operated businesses, with entrepreneurial objectives, ready to expand and keen to internationalize.

Specifically, our study is based on a sample of 31 businesses located in one region in Argentina (Mendoza), two regions in Chile (Cachapoal and Maule), and one region in New Zealand (Central Otago). We focused on entrepreneuring families (Uhlaner et al. Citation2012) with entrepreneurial objectives, ready to expand and keen to internationalize. Then, all of the firms were founded by entrepreneurs, many of whom still own the firm or are the managing director. A summary of the sample characteristics is presented in Table . A summary of company size and exports is shown in Table , while Table shows export details.

Table 1. Sample Characteristics

Table 2. Company Size and Export Overview

Table 3. Export Overview

We conducted the in‐depth personal interviews during 2013–2014. In Argentina, this was in Mendoza, one of the main cities on the west side of Argentina. In Chile, the interviews took place in the cities of Curico, Santiago, and Talca. We conducted the New Zealand interviews at the vineyards of Central Otago subregions: Cromwell, Bannockburn, and Gibbston Valley. Owner–operators, who were also managing directors, were the most appropriate contact for the interviews as they had a “total picture” of the importance of their firms' internationalization process. The use of such interviewees as key informants in this kind of study is a convention of small firm research (Tzokas, Carter, and Kyriazopoulos Citation2001). Two of the authors conducted the interviews in the local language, Spanish Castellano in Argentina and Chile and English in New Zealand. Each interview lasted up to two hours. The Spanish interviews were translated into English. The interview protocol is shown in the Appendix.

The objective of the interviews was to explore our two research propositions and gain an understanding, in a comparative context, of the drivers and barriers of internationalization activities by small family firms located in the three international wine clusters. Content analysis of the interviews was performed to understand how firms in each cluster internationalize through inter‐firm cooperation and the use of industry organizations like a trade organization, or institutions, as facilitators for their internationalization. We discuss our results and propositions below following an analysis of our interviews.

Context

The companies were drawn from firms participating in the value chain activities of wine, a primary industry that makes a substantial contribution in all three countries. This particular industry was chosen for four main reasons. First, it possesses similar characteristics across all three countries. Second, firms were clustered in specific geographical regions in all three countries and contribute directly to the local economic development of regional and rural areas. Third, all three countries are New World wine producers. Last, Argentina, Chile, and New Zealand are significant world producers of wine: 6th, 8th, and 18th, respectively (Felzensztein and Deans Citation2013). These characteristics led us to believe that this industry would provide useful comparative data for our study.

From a cultural perspective, Argentina and Chile have similar cultures and language, but are subject to very different political and economic fluctuations. As reported in previous cultural studies of family businesses (Discua Cruz, Hamilton, and Jack Citation2012; Gupta and Levenburg Citation2010), it is important to understand and not under‐estimate this. From a marketing and sales point of view, the wine industry in Argentina, Chile, and New Zealand are different. The Argentinian and Chilean industries achieve about 50 percent and 80 percent, respectively, of their sales in foreign markets while New Zealand (Central Otago) exports only 36 percent of production.

Regional cluster policies are also different in the three countries. Argentina has a clear top‐down approach, the industry being an integral part of the Mendoza wine cluster. Chile has a bottom‐up approach, led by the local companies with minimum government intervention, but having a strong trade association: “Wines of Chile.” New Zealand has pursued a different strategy where activity is “controlled” and managed by the cluster with pump‐priming funding from the national government. The New Zealand cluster used a government grant to form the Central Otago Wine Association (COWA). The reputation and success of Central Otago wines in world markets is largely due to the efforts of a COWA wholly owned company, namely Central Otago Pinot Noir Limited (COPNL). Both of these organizations have played critical roles in the marketing, branding, and positioning of Central Otago wines and in the case of COPNL, Central Otago Pinot Noir wines.

Results

Considering our propositions P1 (Clustered firms will have inter‐firm cooperation for entering international markets, rather than for marketing activities in the domestic market) and P2 (Third‐party institutions, such as a trade organization, facilitate the internationalization of clustered firms), we now discuss our results related to P1. In total, 31 interviews were conducted in Argentina, Chile, and New Zealand. Argentinian firms have been exploring new and more diversified export markets since 2012. The majority of them export over 50 percent of their total production, despite being relatively young companies. The key difficulties identified by the managers include inflation, taxing of exports and imports, currency exchange rate problems (and the consequent loss of international competitiveness), a persistent structural deficit, commercial organization of the country, and government restrictions to export. They further explained that the three critical success factors to begin the process of internationalization were import networks, export networks and the “right entry modes to enter foreign markets.” The majority of the firms noted that it is essential to spread their internationalization efforts on a broad portfolio of potential new markets (especially emerging markets) as this helps their export diversification process and minimizes their exposure to the economic crises in the more traditional European markets. Another important point is the overseas network as “having a sales person or a commercial office in key markets is part of our internationalization strategy.” Domestic competition faced by Argentinean firms was a mix of other local firms and Chilean wines. Internationally the competition was the same but also included “Australian and New Zealand, South African, American, Spanish, and French wines.”

Chilean firms, from the Maule Region and the Región del Libertador General Bernardo O'Higgins considered the main difficulty in exporting wines to other countries were “the requirements to entry” as they impacted on market access and “barriers” presented by the prevailing political conditions in certain markets. Managers pointed to the importance of satisfying foreign clients in terms of quality, grape and wine variety (organic, sparkling, premium or fruity wines). Managers noted a serious complexity of exporting, as “…the bad exchange rate against the Chilean peso which is now very strong while the dollar fluctuates.” Historically, they experienced difficulties related to the other Chilean exporters: “We are a small company and have been in the market for more than 15 years but we are just starting to think about exporting products, which requires an incredible effort!” that is now changing: “It was impossible to do it before because of our competitors' low prices….”

Country of origin enablers include country image and the prevailing political and economic environment. Chilean wine companies depend on Export Managers rather than foreign offices to export their products. there is strong competitive rivalry within this industry as well as a highly individualistic business culture in Chile (Felzensztein, Gimmon, and Carter Citation2010). Consequently, Chilean wine companies are even more individualistic and there is fierce competition between them. This leads to problems for SMEs in their internationalization process, positioning, and survival strategy. Chilean wines are produced in thirteen valleys across the country and collaborative marketing effort between producers is almost nonexistent. Chilean producers do however rely heavily on cooperation through alliances with foreign wineries for communicating information about the upgrading of production facilities, wine making and wine marketing. Few have international offices, networks or JVs although two respondents did have warehousing facilities in their two top markets allowing them to ship in quantity and deliver/on‐sell on more of a just‐in‐time (JIT) basis than the usual more protracted export–import timeline. A final example of inter‐firm cooperation is the link between domestic firms and importers or distributors since SMEs rely on the marketing knowledge and capacity of overseas distributors, as well as importers to manage their wine brand(s) (Felzensztein and Deans Citation2013).

The main barrier for New Zealand firms to export is international exchange rate fluctuations coupled with a strong New Zealand dollar (that has since fallen). Few Central Otago vineyards have the financial resources to undertake expansive international marketing activity. Consequently Current export markets were established and developed either for historical reasons, that is, because they were English speaking or because of personal networks and contacts. Few companies have sophisticated market analysis, customer analysis, and forecasting systems in place. When considering the domestic market, all respondents considered each other to be among their main competitors “every time a bottle of Central Otago wine is sold, one less bottle of mine is sold.” Their main international markets have a mix of domestic wines and imported wines. The majority (90 percent) of companies interviewed have their products in foreign markets. It took longer for Chilean firms to internationalize than Argentinian firms and Argentinian firms took longer the New Zealand firms. Similarly, and not unrelated, New Zealand firms cooperated more than Argentinian firms who in turn cooperated more than Chilean firms. Chilean companies were more focused on their own sales and production and respondents did not mention the importance of collective international marketing strategies in order to internationalize their firms, preferring to compete individually in foreign markets.

We now move on to P2 (Third‐party institutions, such as a trade organization, facilitate the internationalization of clustered firms). The economic instability of Argentina has been compensated by regional cluster policies in the Mendoza Valley, to facilitate companies' internationalization and to facilitate better performance in foreign markets. Two Argentinean companies had commercial offices abroad, one has an office in Brazil and the other has an office, through the government, in Shanghai. None of the Argentinian companies had explicit joint ventures (JVs) with foreign firms. Only one company (100 percent sales are Internet based) expressed a preference to coordinate its own marketing without the involvement or “interference” from a third‐party or trade association.

Small Chilean companies do not rely on the trade association “Wines of Chile,” to assist in the development of their marketing initiatives in overseas markets. Rather, they focus on generic marketing leveraging the country and region of origin, highlighting good weather conditions for wine production. As one company stated, “Our wines differentiate themselves from others because of the special micro‐climate produced by the mountains and the coast, as the vineyard is situated in the middle of them…I assure you these wines possess an unique taste and there is not another wine anywhere around the globe with the same characteristics.” They are thus keen to promote their region, history, and individual tradition(s) and characteristics.

In contrast, New Zealand cooperation through shared resources and initiatives managed by both COWA and COPNL has given small vineyards access to global events—trade fairs under the umbrella organization with or without having a physical presence. Options range from “user pays stand space” at international wine fairs as part of a COPNL stand or bottles of wine presented at special importer/sommelier events in potential markets without the winemaker needing to be present. All respondents promoted their wines in a manner that reflected either their beginnings (family‐owned) the scarcity of the release, the region, sub‐region or “Block” the wine came from and always the premium quality of the wine.

Discussion

The existence of local, designated industry organizations in all the three countries is important, supporting our P2. However, the Chilean results showed less use of their trade association when compared to firms in New Zealand and Argentina. At the same time the Chilean case shows little inter‐firm cooperation (P1) and a longer time to internationalize, compared to Argentina or New Zealand. Argentina has one strong trade association, “Wines of Mendoza”; such a regional initiative plus a history of firms exporting faster than Chilean companies is another surprising result due to the internal economic problems facing Argentina. In the case of New Zealand, two trade organizations were well established and have had a significant positive impact on all New Zealand companies' speed‐up their internationalization process.

The majority of the wine companies (90 percent), which we interviewed have their products in foreign markets. Results demonstrated that on average it took longer for Chilean firms to internationalize than Argentinian firms and Argentinian firms took longer the New Zealand firms. The same was for different forms of inter‐firm collaboration. The extreme case was for Chilean firms showing no inter‐firm cooperation in marketing activities for their internationalization activities. The New Zealand firms usually sought international markets from the first vintage and neither size nor age of company influenced their propensity to export. Three of the Chilean firms do not export, the reason being that it is more profitable for them to sell their grapes to other large wine companies and because it is too difficult to compete against these larger companies, such as Concha y Toro. All of the firms from Mendoza Valley export their products, including small to medium firms less than 10 years old. Historically Argentina and Chile have had a more European history of wine consumption thus domestic demand was met by domestic production and little need to export. New Zealand, conversely, was more culturally orientated toward the United Kingdom and only became more wine‐focused during the early 1990s. Thus, firms were inclined to export an early stage as supply exceeded demand. There is also a trend in all three countries of having Export Managers instead of offices or JVs in foreign markets, though some New Zealand companies leased or co‐owned warehousing facilities in Australia and in the United States. In summary, there does not seem to be any natural inhibitors to firms exporting early in their development and speeding up their internationalization process.

Turning to the results in relation to P2, there are again differences in behavior directly related to the existence or otherwise of a cluster organization and the associated trust, cooperation and shared objectives. When considering P2 it is worth doing so against the individual countries' historical background; for example, Argentina has endured economic and political fluctuations over the last decade and this has been a key driver for increased cooperation within their wine sector as there has been a shared recognition that export activity is required to offset domestic currency volatility. Managers explained that this is one of the main reasons for increased cooperation within their wine sector. To achieve this, Argentina has implemented regional cluster policies in the region of Mendoza valley and a collective marketing campaign is being used in order to accelerate the process and scope of internationalization of the SMEs. Respondents feel there has been some level of inter‐firm cooperation and associated local and international market success, but also recognize that it is not a “quick fix” and that such initiatives can take several years to fully benefit members of the cluster.

Chile is in a more established economic and political period and is considered one of South America's most stable and prosperous nations. Perhaps as a consequence of this and their individualistic and highly competitive business culture (previously documented by Felzensztein, Gimmon, and Carter Citation2010), Chilean companies interviewed were more focused on their own sales and production and respondents did not mention the importance of collective international marketing strategies in order to internationalize their firms, preferring to compete individually in foreign markets. Interestingly, some wine companies have started to work in their associated regional valleys where they belong, through the Ruta del Vino. However, much more coordination and inter‐firm cooperation between firms and the introduction of regional public policies are needed to help firms in their internationalization process.

New Zealand has had a stable economic and political landscape for some time and as a result of it specific natural resources and lack of indigenous industry it has a market economy that depends greatly on export activity. The Central Otago region in New Zealand has a history and culture of cooperation, sharing and openness collaborative initiatives. Vineyard owners from 30+ years ago were very much pioneers as the region was not considered wine producing country given the prevailing weather conditions and topography. The formation of COWA, to which almost every single vineyard joined, was critical. Initial COWA seed funding, of several hundred thousand dollars, came from the New Zealand government's Trade & Enterprise department. COWA was responsible for the marketing of the region. With very small productions in the early years, individual vineyards could not afford to market themselves nor the region overseas. COWA was very successful at that. When the number of vineyards growing pinot noir grapes and producing high‐quality wines kept increasing, COWA set up Central Otago Pinot Noir Limited (COPNL) to market that variety alone. COPNL is owned by COWA as a separate stand‐alone company. Events organized by COPNL are strictly on a user pay basis. International events are more affordable when this umbrella organization manages a presence and individual vineyards have stands side by side. If an event is too small to merit a personal presence, for example, a Sommeliers' tasting in a distant and attractive market, a vineyard can make a contribution to the cost and have their wine(s) presented.

Taking into account cultural issues in our selected context and industry, we can say that the overall Argentinian experience may be explained by economic drivers and the Chilean experience may be cultural and historical in nature, especially related to the long existence of large and strong firms competing in this market. In New Zealand, trade associations were seen as pivotal to internationalization and marketing of the region.

While there is some achievement in Argentinian context with the Mendoza trade association, the New Zealand clear success can be largely explained by the inter‐cluster's trust, cooperation, sharing, and almost unanimous support of COWA and COPNL. Therefore, P1 and P2 are supported and explained by our results, especially for the Argentinean and New Zealand cases.

Conclusions

This study has shown that when clusters of small family businesses located in small countries seek to internationalize, there are several issues they should take into account, such as their relationship with trade associations. Our study shows that clustered small businesses find it easier and quicker to internationalize if there is a trade association responsible for the overarching promotion and branding of the regional cluster. That body needs to full trust and support of all the cluster members. Equally, the cluster members must display trust, cooperation, and a shared vision for their collective future. Our sample firms were all family‐owned entrepreneurial start‐ups who internationalized early in their growth life cycle because of domestic market conditions that acted as an enabler through competitive pressure and resultant institutional capability.

Our study and unique context contributes to a deeper understanding of and contribution to the ongoing discussion about small business research in clusters and internationalization. Our results can also contribute to the public policy debate on these issues that are common in both developed and emerging economies.

Practical Implications

The results of this study support the argument that small businesses within a cluster located in a small economy like New Zealand, should consider exporting as soon as sufficient product is available. A cluster policy that leads to a cluster‐owned trade organization can be beneficial for firms' internationalization. Managers should pay more attention to how prevailing market conditions can influence their internationalization efforts rather than being influenced by historical evidence of growth options, as in the case of Chile. The speed and success of internationalization of small family‐owned businesses is more closely related to leveraging domestic experience than traditional incremental international expansion.

Managerial lessons for emerging Latin American countries, such as Chile, shows an urgent necessity to create a new trade association that represents smaller firms. This will allow more social and informal interaction between firms, enhancing the possibility of further inter‐firm cooperation and thereafter a more effective internationalization process for the SME sector. This has implications for public policies that seek to achieve international competitiveness of SMEs in other emerging economies.

Limitations and Future Research

Findings and conclusions based on this study need validation due to their limitations. The small number of cases (31) in three countries cannot be said to be representative in a statistical sense. There were some difficulties in collecting the data through interviews due to the lack of collaboration of managers especially in the case of Chile, where a more individualistic behavior and self‐confident attitude of managers prevails.

A recommendation would be to interview other wine companies from other regions in the world. It would also be useful to conduct further interviews to support and confirm the conclusions of this study. In the case of Argentina, it would be interesting to return and record measures of success as attributed to the Mendoza Valley cluster initiative. In the case of Chile, it is recommended to conduct a qualitative study involving the main managers of each Ruta del Vino and analyze futures plans and polices regarding internationalization either of the valley (collective internationalization) or by individual firms. In the case of New Zealand, it would be interesting to explore other subregions of Central Otago as well as other wine regions in the country. In all three countries, a longitudinal study would offer some interesting insights to behavior and performance over time as result of the different political, economic, and cultural differences between the three countries. This will enrich the unique cultural contexts presented in this three countries study. Finally, considering that Hermelo and Vassolo (Citation2012) found industry effect was more important than the country effect, future research may compare a sector other than wines, in these three countries.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Christian Felzensztein

Christian Felzensztein has the Dean's Chair in Strategy at Massey University, New Zealand.

Kenneth R. Deans

Kenneth R. Deans is Professor at La Rochelle Business School, France.

Léo‐paul Dana

Léo‐Paul Dana is Professor at Montpellier Business School, member of Montpellier Research in Management, and member of the Entrepreneurship & Innovation Chair (LabEx Entrepreneurship/University of Montpellier, France).

References

- Acs, Z., S. Desai, and J. Hessels (2008). “Entrepreneurship, Economic Development and Institutions,” Small Business Economics 31(3), 219–234.

- Agndal, H., S. Chetty, and H. Wilson (2008). “Social Capital Dynamics and Foreign Market Entry,” International Business Review 17(6), 663–675.

- Ali, A., and P. M. Swiercz (1991). “Firm Size and Export Behavior: Lessons from the Midwest,” Journal of Small Business Management 29(2), 71–78.

- Anderson, C. A., and J. A. Narus (1990). “A Model of Distributor Firm and Manufacturing Firm Working Relationships,” Journal of Marketing 54(1), 42–58.

- Andersson, T., S. S. Serger, J. Sörvik, and E. W. Hansson (2004). The Cluster Policies Whitebook. Malmö, Sweden: Vinnova.

- Astley, W. G., and C. J. Fombrun (1983). “Collective Strategy: Social Ecology of Organizational Environments,” Academy of Management Review 8(4), 576–587.

- Astrachan, J. H. (2010). “Strategy in Family Business: Toward a Multidimensional Research Agenda,” Journal of Family Business Strategy 1(1), 6–14.

- Audretsch, D. B. (2001). “The Role of Small Firms in U.S. Biotechnology Clusters,” Small Business Economics 17(1), 3–15.

- Bathelt, H. (2005). “Cluster Relations in the Media Industry: Exploring the ‘Distanced Neighbour’ Paradox in Leipzig,” Regional Studies 39(1), 105–127.

- Becattini, G. (1990). “The Marshallian Industrial District as a Socioeconomic Notion,” in Industrial Districts and Inter‐Firm Co‐Operation in Italy. Eds. F. Pyke, G. Becattini, and W. Sengenberger. Geneva, International Institute for Labour Studies, 37–51.

- Becattini, G. (2004). Industrial Districts: A New Approach to Industrial Change, Cheltenham. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Becattini, G., M. Bellandi, G. D. Ottati, and F. Sforzi (Eds.) (2003). From Industrial Districts to Local Development. An Itinerary of Research. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Becker, T. H., and J. L. Porter (1983). “Small Business Plus Export Trading Companies: New Formula for Export Success?” Journal of Small Business Management 21(4), 8–16.

- Bengtsson, M., and S. Kock (1999). “Cooperation and Competition in Relationships Between Competitors in Business Networks,” Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing 14(3), 178–189.

- Bengtsson, M., and S. Kock (2000). “‘Coopetition’ in Business Networks—To Cooperate and Compete Simultaneously,” Industrial Marketing Management 29(5), 411–426.

- Bengtsson, M., and S. Kock (2014). “Coopetition—Quo Vadis? Past Accomplishments and Future Challenges,” Industrial Marketing Management 43, 180–188.

- Blandy, R. (2000). Industry Clusters Program: A Review, South Australian Business Vision 2010. Adelaide: Government of South Australia.

- Boehe, D. (2013). “Collaborate at Home to Win Abroad: How Does Access to Local Network Resources Influence Export Behavior?” Journal of Small Business Management 51(2), 167–182.

- Brandenburger, A. M., and B. J. Nalebuff. (1996). Co‐Opetition. New York: Doubleday Dell.

- Brasch, J. J. (1981). “Deciding on an Organizational Structure for Entry into Export Marketing,” Journal of Small Business Management 19(2), 7–15.

- Bresnahan, T., and A. Gambardella. (2004). Building High‐Tech Clusters: Silicon Valley and Beyond. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Brown, P., R. Mcnaughton, and J. Bell (2010). “Marketing Externalities in Industrial Clusters: A Literature Review and Evidence from the Christchurch, New Zealand Electronics Cluster,” Journal of International Entrepreneurship 8(2), 168–181.

- Brusco, S. (1986). “Small Firms and Industrial Districts: The Experience of Italy,” in New Firms and Regional Development in Europe. Eds. D. Keeble and E. Wever. London, Croom Helm, 182–202.

- Cainelli, G., M. Mazzanti, and S. Montresor (2012). “Environmental Innovations, Local Networks and Internationalization,” Industry and Innovation 19(8), 697–734.

- Calabrò, A., M. Brogi, and M. Torchia (2016). “What Does Really Matter in the Internationalization of Small and Medium‐Sized Family Businesses?” Journal of Small Business Management 54(2), 679–696. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12165.

- Camuffo, A., and R. Grandinetti (2011). “Italian Industrial Districts as Cognitive Systems: Are They Still Reproducible?” Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 23(9–10), 1–38.

- Carbonara, N., I. Giannoccaro, and B. Mckelvey (2010). “Making Geographical Clusters More Successful: Complexity‐Based Policies,” E:CO 12(3), 21–45.

- Carlsson, B., and Mudambi, R. (2003). “Globalization, Entrepreneurship and Public Policy: A Systems View,” Industry and Innovation 10(1), 103–116.

- Casillas, J. C., and F. J. Acedo (2013). “Speed in the Internationalization Process of the Firm,” International Journal of Management Reviews 15(1), 15–29.

- Casillas, J. C., and A. M. Moreno‐menéndez (2014). “Speed of the Internationalization Process: The Role of Diversity and Depth in Experiential Learning,” Journal of International Business Studies 45(1), 85–101.

- Chetty, S., and H. Agndal (2008). “Role of Inter‐Organizational Networks and Interpersonal Networks in an Industrial District,” Regional Studies 42(2), 175–187.

- Chetty, S., and C. Campbell‐hunt (2004). “A Strategic Approach to Internationalization: A Traditional versus a ‘Born‐Global’ Approach,” Journal of International Marketing 12(1), 57–81.

- Chetty, S., M. Johanson, and O. Martín (2014). “Speed of Internationalization: Conceptualization, Measurement and Validation,” Journal of World Business 49(4), 633–650.

- Chiarvesio, M., and E. Di Maria (2009). “Internationalization of Supply Networks Inside and Outside Clusters,” International Journal of Operations and Production Management 29(11), 1186–1207.

- Corò, G., and R. Grandinetti (2001). “Industrial District Responses to the Network Economy: Vertical Integration versus Pluralist Global Exploration,” Human Systems Management 20(3), 189–199.

- Czakon, W., and L.‐P. Dana (2013). “Coopetition at Work: How Firms Shaped the Airline Industry,” Journal of Social Management/Revue Européenne des Sciences Sociales et du Management/Zeitschrift für Sozialmanagement 11(20), 32–61.

- Dagnino, E., and E. Rocco. (2009). Coopetition Strategy: Theory, Experiments and Cases. New York: Routledge.

- Dana, L.‐P. (1994). “On the Internationalization of a Discipline: Research and Methodology in Cross‐Cultural Entrepreneurship and Small Business Studies,” Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship 11(2), 61–76.

- Dana, L.‐P. ed. (2004). The Handbook of Research on International Entrepreneurship. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Dana, L.‐P., T. Chan, and D. Chia (2008). “Micro‐Enterprise Internationalisation Without Support: The Case of Angus Exports,” International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation 9(1), 5–10.

- Dana, L.‐P., H. Etemad, and R. W. Wright. (1999). “Theoretical Foundations of International Entrepreneurship,” in International Entrepreneurship: Globalization of Emerging Businesses. Ed. R. W. Wright. Stamford, CT: JAI Press, 3–22.

- Dana, L.‐P., H. Etemad, and R. W. Wright (2000). “The Global Reach of Symbiotic Networks,” Journal of Euromarketing 9(2), 1–16.

- Dana, L.‐P., and J. Granata (2013). “Evolution de la Coopétition Dans un Cluster: Le Cas de Waipara Dans le Secteur Du Vin,” Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship 26(4), 429–442.

- Dana, L.‐P., J. Granata, F. Lasch, and A. Carnaby (2013). “The Evolution of Co‐Opetition in the Waipara Wine Cluster of New Zealand,” Wine Economics and Policy 2, 42–49.

- Dana, L.‐P., and G. Guieu (2014). “Entrepreneuriat Coopetitif: Comment Integrer la Concurrence dans un Contexte Cooperatif? Une Enquête Aupres des Eleveurs de Rennes Sames,” Revue Internationale PME 27(3–4), 173–191.

- Dana, L.‐P., and K. E. Winstone (2008). “New World Wine Cluster Formation: Operation, Evolution and Impact in New Zealand,” International Journal of Food Science and Technology 43(12), 2177–2190.

- D'angelo, A., A. Majocchi, and T. Buck (2016). “External Managers, Family Ownership and the Scope of SME Internationalization,” Journal of World Business 51(4), 534–547.

- Dawson, A., and D. Hjorth (2012). “Advancing Family Business Research Through Narrative Analysis,” Family Business Review 25(3), 339–355.

- Debrulle, J., J. Maes, and L. Sels (2014). “Start‐Up Absorptive Capacity: Does the Owner's Human and Social Capital Matter?” International Small Business Journal 32(7), 777–801.

- Delgado, M., M. Porter, and S. Stern. (2016). “Defining Clusters of Related Industries,” Journal of Economic Geography 16(1), 1–38.

- Del sol, P., and J. Kogan (2007). “Regional Competitive Advantage Based on Pioneering Economic Reforms: The Case of Chilean FDI,” Journal of International Business Studies 38(6), 901–927.

- De Marchi, V., and R. Grandinetti (2014). “Industrial Districts and the Collapse of the Marshallian Model: Looking at the Italian Experience,” Competition and Change 18(1), 70–87.

- Depeyre, C., and H. Dumez (2009). “A Management Perspective on Market Dynamics: Stabilizing and Destabilizing Strategies in the US Defense Industry,” European Management Journal 27(2), 90–99.

- De Propris, L., and L. Lazzeretti (2009). “Measuring the Decline of a Marshallian Industrial District: The Birmingham Jewellery Quarter,” Regional Studies 43(9), 1135–1154.

- Discua cruz, A., E. Hamilton, and S. Jack (2012). “Understanding Entrepreneurial Cultures in Family Businesses: A Study of Family Entrepreneurial Teams in Honduras,” Journal of Family Business Strategy 3(3), 147–161.

- Dollinger, M. J., and P. A. Golden (1992). “Interorganizational and Collective Strategies in Small Firms: Environmental Effects and Performance,” Journal of Management 18(4), 695–715.

- Doz, Y. (1996). “The Evolution of Cooperation in Strategic Alliances: Initial Conditions or Learning Processes?” Strategic Management Journal 17(S1), 55–83.

- Ebbekink, M., and A. Lagendijk (2013). “What's Next in Researching Cluster Policy: Place‐Based Governance for Effective Cluster Policy,” European Planning Studies 21(5), 735–753.

- Eisenhardt, K. M., and M. E. Graebner (2007). “Theory Building from Cases: Opportunities and Challenges,” Academy of Management Journal 50(1), 25–32.

- Eisenhardt, K. M., and C. Schoonhoven (1996). “Resource‐Based View of Strategic Alliance Formation: Strategic and Social Effects in Entrepreneurial Firms,” Organisation Science 7(2), 136–150.

- Etemad, H. (2016). “Preface to the Thematic Special Issue on International Entrepreneurship in and from Emerging Economies,” Journal of International Entrepreneurship 14(1), 1–4.

- Etemad, H., R. W. Wright, and L.‐P. Dana (2001). “Symbiotic International Business Networks: Collaboration Between Small and Large Firms,” Thunderbird International Business Review 43(4), 481–499.

- Evers, N., and J. G. Knight (2008). “Role of International Trade Shows in Small Firm Internationalization: A Network Perspective,” International Marketing Review 25(5), 544–562.

- Felzensztein, C. (2016). “International Entrepreneurship in and from Emerging Economies,” Journal of International Entrepreneurship 14(1), 5–7.

- Felzensztein, C., S. Brodt, and E. Gimmon (2014). “Do Strategic Marketing and Social Capital Really Matter in Regional Clusters? Lessons from an Emerging Economy of Latin America,” Journal of Business Research 67(4), 498–507.

- Felzensztein, C., L. Ciravegna, P. Robson, and E. Amorós (2015). “Networks, Entrepreneurial Orientation, and Internationalization Scope: Evidence from Chilean Small and Medium Enterprises,” Journal of Small Business Management 53(s1), 145–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12188.

- Felzensztein, C., and K. R. Deans (2013). “Marketing Practices in Wine Clusters: Insights from Chile,” Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing 28(4), 357–367. https://doi.org/10.1108/08858621311313947.

- Felzensztein, C., and E. Gimmon (2007). “The Influence of Culture and Size upon Inter‐firm Marketing Cooperation: A Case Study of the Salmon Farming Industry,” Marketing Intelligence and Planning 25(4), 377–393.

- Felzensztein, C., and E. Gimmon (2009). “Social Networks and Marketing Cooperation in Entrepreneurial Clusters: An International Comparative Study,” Journal of International Entrepreneurship 7(4), 281–291.

- Felzensztein, C., E. Gimmon, and S. Carter (2010). “Geographical Co‐Location, Social Networks and Inter‐Firm Marketing Cooperation: The Case of the Salmon Industry,” Long Range Planning 43(5–6), 675–690.

- Felzensztein, C., C. Stringer, M. Benson‐rea, and S. Freeman (2014). “International Marketing Strategies in Industrial Clusters: Insights from the Southern Hemisphere,” Journal of Business Research 67(5), 837–846

- Fernandez, A.‐S., F. Le roy, and D. R. Gnyawali (2014). “Sources and Management of Tension in Co‐Opetition Case Evidence from Telecommunications Satellites Manufacturing in Europe,” Industrial Marketing Management 43(2), 222–235.

- Fernández, Z., and M. J. Nieto. (2014). “Internationalization of Family Firms,” in The SAGE Handbook of Family Business. Eds. L. Melin, M. Nordqvist, and P. Sharma. London: Sage, 403–423.

- Ford, D. (2009). “An Outline for Researching Business Interaction and Why Competition May Decline in Business Networks,” paper presented at the 25th IMP Conference, September 3–5, Marseilles, France.

- Fritsch, M., and P. Mueller (2004). “The Effects of New Business Formation on Regional Development Over Time,” Regional Studies 38(8), 961–975.

- Furlan, A., and R. Grandinetti (2011). “Size, Relationships and Capabilities: A New Approach to the Growth of the Firm,” Human Systems Management 30(4), 195–213.

- Giuliani, E., and M. Bell (2005). “The Micro‐Determinants of Meso‐Level Learning and Innovation: Evidence from a Chilean Wine Cluster,” Research Policy 34(1), 47–68.

- Gray, B. J., and R. Mcnaughton (2010). “Knowledge, Values and Internationalisation: Introduction to the Special Edition,” Journal of International Entrepreneurship 8(2), 115–120.

- Gueguen, G. (2009). “Coopetition and Business Ecosystems in the Information Technology Sector: The Example of Intelligent Mobile Terminal,” International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business 8(1), 135–153.

- Gulati, R. (2007). Managing Network Resources: Alliances, Affiliations and Other Relational Assets. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gupta, V., and N. Levenburg (2010). “A Thematic Analysis of Cultural Variations in Family Businesses: The CASE Project,” Family Business Review 23(2), 155–169.

- Gupta, V., N. M. Levenburg, L. Moore, J. Motwani, and T. Schwarz (2011). “The Spirit of Family Business: A Comparative Analysis of Anglo, Germanic and Nordic Nations,” International Journal of Cross Cultural Management 11(2), 133–151.

- Hall, C. M. (2005). “Rural Wine and Food Tourism Cluster and Network Development,” in Rural Tourism and Sustainable Business. Eds. D. R. Hall, I. Kirkpatrick, and M. Mitchell. Bristol, UK: Channel View Publications, 149–164.

- Hannigan, T. J., M. Cano‐kollmann, and R. Mudambi (2015). “Thriving Innovation Amidst Manufacturing Decline: The Detroit Auto Cluster and the Resilience of Local Knowledge Production,” Industrial and Corporate Change 24(3), 613–634.

- Harrison, B. (1992). “Industrial Districts: Old Wine in New Bottles?” Regional Studies 26(5), 469–483.

- Hart, S., and N. Tzokas (1999). “The Impact of Marketing Research Activity on SME Export Performance: Evidence from the UK,” Journal of Small Business Management 37(2), 63–75.

- Hayakawa, K., H.‐H. Lee, and D. Park (2014). “Do Export Promotion Agencies Increase Exports?” The Developing Economies 52(3), 241–261.

- Hermelo, F. D., and R. Vassolo, (2012). “How Much Does Country Matter in Emerging Economies? Evidence from Latin America,” International Journal of Emerging Markets 7(3), 263–288.

- Hilmersson, M. (2012). “Experiential Knowledge Types and Profiles of Internationalising Small and Medium‐Sized Enterprises,” International Small Business Journal 32(7), 802–817.

- Huemer, L., G. Boström, and C. Felzensztein (2009). “Control‐Trust Interplays and the Influence Paradox: A Comparative Study of MNC‐subsidiary Relationships,” Industrial Marketing Management 38(5), 520–528.

- Johannisson, B., L. C. Caffarena, A. F. Discua cruz, M. Epure, E. Hormiga, M. Kapelko, K. Murdock, D. Nanka‐bruce, M. Olejarova, A. Sanchez lopez, A. Sekki, M. Stoian, H. Totterman, and A. Bisignano (2007). “Interstanding the Industrial District: Contrasting Conceptual Images as a Road to Insight,” Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 19(6), 527–554.

- Katila, R., J. Rosenberger, and K. M. Eisenhardt (2008). “Swimming with the Sharks: Technology Ventures, Defence Mechanisms and Corporate Relationships,” Administrative Science Quarterly 53(2), 295–332.

- Ketels, C., and Ö. Sölvell (2006). Clusters in the EU‐10 New Member Countries. Brussels: Europe Innova.

- Kontinen, T., and A. Ojala (2010). “The Internationalization of Family Businesses: A Review of Extant Research,” Journal of Family Business Strategy 1(2), 97–107.

- Kontinen, T., and A. Ojala (2011). “Network Ties in the International Opportunity Recognition of Family SMEs,” International Business Review 20, 440–453.

- Kontinen, T., and A. Ojala (2012a). “Internationalization Pathways Among Family‐Owned SMEs,” International Marketing Review 29(5), 496–518.

- Kontinen, T., and A. Ojala (2012b). “Social Capital in the International Operations of Family SMEs,” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 19(1), 39–55.

- Kuivalainen, O., S. Sundqvist, S. Saarenketo, and R. Mcnaughton (2012). “Internationalization Patterns of Small and Medium‐Sized Enterprises,” International Marketing Review 29(5), 448–465.

- Lang, E. M. (1977). “It's the Little Guys Who Need Export Aid,” Journal of Small Business Management 15(1), 7–9.

- Leonidou, L. C. (2004). “An Analysis of the Barriers Hindering Small Business Export Development,” Journal of Small Business Management 42(3), 279–302.

- Le roy, F., P. Marques, and F. Robert (2008). “Coopetition et Performances—Le Cas du Football Professionnel Français,” Revue Sciences de Gestion 64(December), 127–149.

- Li, H., G. C. de Zubielqui, and A. O'connor (2015). “Entrepreneurial Networking Capacity of Cluster Firms: A Social Network Perspective on How Shared Resources Enhance Firm Performance,” Small Business Economics 45(3), 523–541.

- Liang, X., L. Wang, and Z. Cui (2014). “Chinese Private Firms and Internationalization: Effects of Family Involvement in Management and Family Ownership,” Family Business Review 27(2), 126–141.

- Mackinnon, D., K. Chapman, and A. Cumbers (2004). “Networking, Trust and Embeddedness Amongst SMEs in the Aberdeen Oil Complex,” Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 16(2), 87–106.

- Madsen, T. K., and P. Servais (1997). “The Internationalization of Born Globals: An Evolutionary Process?” International Business Review 6(6), 561–583.

- Mariani, M. M. (2007). “Coopetition as an Emergent Strategy: Empirical Evidence from a Consortium of Italian Opera Houses,” International Studies in Management and Organization 37(2), 97–126.

- Mariani, M. M. (2009). “Emergent Coopetitive and Cooperative Strategies in Interorganizational Relationships: Empirical Evidence from Australian and Italian Operas,” in Coopetition Strategy: Theory, Experiments and Cases. Eds. G. B. Dagnino and E. Rocco. New York: Routledge, 166–190.

- Marshall, A. (1920). Principles of Economics. London: Macmillan.

- Maskell, P. (2001). “Towards a Knowledge‐Based Theory of the Geographic Cluster,” Industrial and Corporate Change 10(4), 921–943.

- Mcadam, M., R. Mcadam, A. Dunn, and C. Mccall (2014). “Development of Small and Medium‐Sized Enterprise Horizontal Innovation Networks: UK Agri‐food Sector Study,” International Small Business Journal 32(7), 830–853.

- Meade, W., M. Hyman, and L. Blank (2009). “Promotions as Coopetition in the Soft Drink Industry,” Academy of Marketing Studies Journal 13(1), 105–133.

- Melin, L., M. Nordqvist, and P. Sharma. (2014). The SAGE Family Business Handbook. London: Sage.

- Mingo, S. (2013). “Entrepreneurial Ventures, Institutional Voids, and Business Group Affiliation: The Case of Two Brazilian Start‐Ups, 2002–2009,” Academia: Revista Latinoamericana de Administración 26(1), 61–76. Available from: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=71629937004.

- Moen, O., and P. Servais (2002). “Born Global or Gradual Global? Examining the Export Behavior of Small and Medium‐Sized Enterprises,” Journal of International Marketing 10(3), 49–72.

- Moini, A. H. (1998). “Small Firms Exporting: How Effective Are Government Export Assistance Programs?” Journal of Small Business Management, 36(1), 1–15.

- Mudambi, R., S. Mudambi, D. Mukherjee, and V. Scalera (2016). “Global Collaboration and the Evolution of an Industry Cluster,” paper presented at the AIB UK Conference, London, UK.

- Mudambi, R., and Santangelo, G. (2016). “From Shallow Resource Pools to Emerging Clusters: The Role of MNE Subsidiaries in Peripheral Areas,” Regional Studies 50, 1965–1979. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.985199.

- Mytelka, L., and H. Goertzen. (2003). “Vision, Innovation and Identity: The Emergence of a Wine Cluster in the Niagara Peninsula,” in Innovation Systems Research Network Conference. Ottawa: Canada National Research Council, 1–6.

- Namiki, N. (1988). “Export Strategy for Small Business,” Journal Small Business Management 26(2), 32–37.

- Obadic, A. (2013). “Specificities of EU Cluster Policies,” Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy 7(1), 23–35.

- O'gorman, C. (2014). “Creating Competitiveness: Entrepreneurship and Innovation Policies for Growth,” International Small Business Journal 32(7), 854–855.

- Okura, M. (2007). “Coopetitive Strategies of Japanese Insurance Firms: A Game Theory Approach,” International Studies of Management and Organization 37(2), 53–69.

- Oviatt, B. M., and P. P. Mcdougall (1994). “Toward a Theory of International New Ventures,” Journal of International Business Studies 25(1), 45–64.

- Oviatt, B. M., and P. P. Mcdougall (2005). “Defining International Entrepreneurship and Modeling the Speed of Internationalization,” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 29(5), 537–554.

- Park, B.‐Y., M. K. Srivastava, and D. R. Gnywalli (2014). “Walking the Tight Rope of Coopetition: Impact of Competition and Cooperation Intensities and Balance on Firm Innovation Performance,” Industrial Marketing Management 43, 210–221.

- Patmore, F., and M. Haddoud (2015). “The Drivers and Barriers Facing Small to Medium‐sized Enterprises (SMEs) Entering the US Market,” Journal of Research Studies in Business and Management 1(1), 259–280.

- Pellegrin‐boucher, E., and F. Le roy (2009). “Dynamique des Stratégies de Coopétition dans le Secteur des TIC: Le Cas des ERP,” Finance‐Contrôle‐Stratégie 12(3), 97–130.

- Peng, T.‐J. A., and M. Bourne (2009). “The Coexistence of Competition and Cooperation Between Networks: Implications from Two Taiwanese Healthcare Networks,” British Journal of Management 20(3), 377–400.

- Pillay, N. S., and R. Uctu (2013). “A Snapshot of the Successful Bio‐Clusters Around the World: Lessons for South African Biotechnology,” Journal of Commercial Biotechnology 19(1), 40–52.

- Piore, M., and C. Sabel. (1984). The Second Industrial Divide: Possibilities for Prosperity. New York: Basic Books.

- Porter, M. E. (1997). On Competition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business Press.