Abstract

In this paper, we apply insights from poststructuralist feminist theory to contribute to entrepreneurial leadership. By drawing on 21 individual narratives with Lebanese women entrepreneurs, we explore how they determine their status as entrepreneurial leaders and establish their entrepreneurial identities. Although the factors of gender, sociocultural values, and agency can be counteractive, it is agency that creates space for entrepreneurship for women and provides them a means to navigate structural inequalities. The entrepreneurs in this study engage in compliance, disregard, and defiance strategies to expand the boundaries of what is socially permissible for women and to strengthen their identities. This research contributes to studies on entrepreneurial leadership and aids in the development of theory by demonstrating how Arab women construct entrepreneurial leadership, agency, and identity at the juncture of patriarchy, sociocultural values, and gender ideologies.

Introduction

Entrepreneurial leadership research is often gendered as male to describe the dominant influence of men in leadership roles (Galloway, Kapasi, and Sang Citation2015; Hamilton Citation2013; Harrison, Leitch, and McAdam Citation2015; Henry et al. Citation2015). This view treats gender as a variable in isolation from its relationships with other dynamic social categories, such as culture (Crenshaw Citation1997; Essers and Tedmanson Citation2014; Mirchandani Citation1999). It also limits our implicit understanding of the unique entrepreneurial experiences and contributions of women and other minority groups (Brush, de Bruin, and Welter Citation2009; Calás, Smircich, and Bourne Citation2009; Welter Citation2011) and results in conflicted identities for female entrepreneurs in leadership (Chasserio, Pailot, and Poroli Citation2014; de Bruin, Brush, and Welter Citation2007; Diaz‐Garcia and Welter Citation2013).

In response, entrepreneurship scholars promote a contextually embedded approach to entrepreneurial leadership to advance our understanding of the complex process by which women entrepreneurs ascribe meaning to their working lives (Al Dajani and Marlow Citation2010; Galloway, Kapasi, and Sang Citation2015; Henry et al. Citation2015; Lewis Citation2016; Santos, Roomi, and Liñán Citation2016; Yousafzai, Saeed, and Muffatto Citation2015). The notion of an embedded context provides a richer sense of how sociocultural forces construct the subjectivities underlying individuals' capacity to think and act as prescribed by their social environment. Gender then is best understood and explored as socially constructed and as subjective, created, produced, and constituted differently across time, place, and culture (Ahl Citation2006; Essers and Benschop Citation2009; Harrison, Leitch, and McAdam Citation2015; Holvino Citation2010; Metcalfe and Woodhams Citation2012).

Despite the compelling evidence for adopting the perspective of contextual embeddedness in entrepreneurship studies, minimal attention has been paid to the experiences of women entrepreneurs in different geographical and cultural contexts, as well as to the use of feminist theories in entrepreneurship studies (de Bruin, Brush, and Welter Citation2007; Welter Citation2011; Zahra and Wright Citation2011). This gap is especially evident in the context of the Arab world, where sociocultural values are consistently reported to play an important role in Arab women's entrepreneurial experiences and hinder their advancement (Al Dajani and Marlow Citation2010; Tlaiss Citation2015a). We therefore aim to explore how Lebanese women entrepreneurs identify with the concept of entrepreneurial leadership and perceive themselves in relation to this concept. Accordingly, our main research questions are: How do Lebanese women entrepreneurs experience entrepreneurial leadership and the factors underlying their experiences? What strategies and mechanisms do Lebanese women use to develop their leadership identities? Adopting a social constructionist approach to entrepreneurial leadership, we perform poststructural feminist theorizing to uncover and deconstruct Arab women entrepreneurs' stories of navigating gender assumptions to construct their identities as entrepreneurial leaders within a patriarchal society. The frame of intersectionality enables better understanding how various axes of differences intersect and interlock in the construction of women's entrepreneurial identities and how multiple work identities connect to the societal phenomenon of entrepreneurship (Crenshaw Citation1997).

This study takes an important step to address the complexity and uniqueness of Arab women's experiences as entrepreneurial leaders. Based on the findings, we argue that Lebanese women entrepreneurs use different strategies; adopting, utilizing, and rejecting gender and sociocultural norms to establish their entrepreneurial identities. We demonstrate how the factors of gender, sociocultural values, and agency pull women entrepreneurs in Lebanon in different directions, demanding that they learn to navigate structural inequalities to negotiate their leadership identities.

To set the stage for this investigation, we first establish the conceptual framing of entrepreneurial leadership as a gendered, socially constructed process (Harrison, Leitch, and McAdam Citation2015) from a contextually embedded perspective (Ahl Citation2006; Brush, de Bruin, and Welter Citation2009; Welter, Citation2011). Second, we discuss feminist theories and explain our reasoning for adopting a poststructuralist feminist lens to understand and theorize the gendered constructions of entrepreneurial leadership. Third, we explain the relevance of the poststructuralist feminist perspective to exploring entrepreneurial identities and the processes of identity construction. Fourth, we ground our investigation in the local context of gender ideology and sociocultural norms in Lebanon. Next, we explain the methodological approach and discuss the results. Finally, we present our concluding remarks, followed by the limitations of the current study and suggestions for future research.

Theoretical Framework

Gender, Entrepreneurship, and Leadership

Entrepreneurial leadership is viewed as a fusion of entrepreneurship, entrepreneurship orientation, and entrepreneurship management and is positioned at the nexus of entrepreneurship and leadership (Harrison, Leitch, and McAdam Citation2015). Notions of entrepreneurial leadership, recognizing the fluidity of the concept, have evolved from a predominantly essentialist approach focusing on traits and behaviors depicting the male entrepreneur as the exemplar of success (Ahl Citation2006; Ahl and Marlow Citation2012; Davis and Shaver Citation2012; de Bruin, Brush, and Welter Citation2007; Hamilton Citation2013; Mirchandani Citation1999; West and Zimmerman Citation1987). This notion, however, has developed and taken on a more contextually embedded approach (Yousafzai, Saeed, and Muffatto Citation2015), which perceives entrepreneurial leadership as a social process of becoming an entrepreneur and a leader (Kempster and Cope Citation2010). The latter approach underscores the socially constructed nature of entrepreneurial leadership and focuses on the complex, dynamic interactions between entrepreneurs and their social environments (Cope Citation2005) and the processes that unfold amidst these interactions (Diaz‐Garcia and Welter Citation2013; Greenberg, McKone‐Sweet, and Wilson Citation2011; Kuratko Citation2007; Vecchio Citation2003; Zahra and Wright Citation2011). We therefore assume that entrepreneurial leadership is a complex, dynamic, and highly context‐dependent activity in which individuals' cognizance of themselves and their surrounding social context guides their behavior and identity construction. The definition of entrepreneurial leaders provided by Greenberg, McKone‐Sweet, and Wilson (Citation2011, p. 2) captures this view: “individuals who, through an understanding of themselves and the contexts in which they work, act on and shape opportunities that create value for their organizations, their stakeholders and the wider society.”

Consequently, there has been a marked movement among entrepreneurship scholars toward greater engagement with gender theory, recognizing gender as socially constructed rather than biologically determined (Bamiatzi et al. Citation2015; Galloway, Kapasi, and Sang Citation2015; Hamilton Citation2013; Harrison, Leitch, and McAdam Citation2015; Javadian and Singh Citation2012; Yousafzai, Saeed, and Muffatto Citation2015). Javadian and Singh (Citation2012) and Al Dajani and Marlow (Citation2010), along with others, argue that women do not merely passively adopt highly gendered constructions of their leadership identities. To the contrary, they actively work, participate in, and resist the structures that simultaneously impede and facilitate their entrepreneurship and influence their status as women entrepreneurial leaders. Studies conducted in different sociocultural contexts demonstrate that social, cultural, and political institutions influence the values and norms in women's experience of entrepreneurship (Bamiatzi et al. Citation2015; Yousafzai, Saeed, and Muffatto Citation2015). These studies promote a more informed debate on the nexus of gender and entrepreneurship in the discourse on entrepreneurial leadership (Harrison, Leitch, and McAdam Citation2015). Moreover, they suggest that context matters in the study of entrepreneurial leadership and that entrepreneurial leadership concepts and frameworks that are appropriate in one territory might not be in another (Harrison, Leitch, and McAdam Citation2015).

Despite recent scholarly efforts, research conceptualizing the experiences of women entrepreneur leaders in geographical contexts and cultures outside the west remains insufficient (Yousafzai, Saeed, and Muffatto Citation2015). In meeting our overall objective to examine how Lebanese women entrepreneurs perceive and identify themselves as entrepreneurial leaders, we hope to delineate both the process and circumstances of their experiences. We also aim to demonstrate how these circumstances are not only tied to economics but are also contextually embedded in the sociocultural values surrounding women. Recognizing entrepreneurial leadership as a gendered, socially constructed process involving both individuals and their context or circumstances and acknowledging the significance of gender in both entrepreneurship and leadership, we move to examine the feminist perspectives on entrepreneurship.

Feminist Theory and Entrepreneurship

Feminist theorizing challenges the highly gendered nature of entrepreneurship studies (Ahl Citation2006; Galloway, Kapasi, and Sang Citation2015; Harrison, Leitch, and McAdam Citation2015; Henry et al. Citation2015) by promoting a shift from an exclusive focus on the masculine experience toward a more interpretive methodology that better understands and advances women's experiences (Calás, Smircich, and Bourne Citation2009). Feminist theory and research falls into three categories based on specific conceptualizations of gender in relation to entrepreneurship studies (Ahl Citation2006; Calás, Smircich, and Bourne Citation2009; Harding Citation1987). First, studies adopt liberal feminist theory positing that equality and equal opportunities exist for both genders, but the structural barriers subordinating women create differences between men and women (Diaz‐Garcia and Welter Citation2013; Lewis Citation2013). This view promotes a clear, though unstated, masculine norm and pushes women to adapt to social inequalities by abandoning their perceived femininity and adopting the normalized masculine discourse of entrepreneurship (Lewis Citation2013). Second, studies including social and radical feminist theories characterize men and women as different but equal (Ahl Citation2006). Within women's entrepreneurship, both categories of feminist studies are criticized for essentializing gender, which increases the risk of oversimplification and blaming the victim, in this case, blaming women entrepreneurs and their actions, or lack thereof, for their own subordination (Ahl and Marlow Citation2012).

The third category of feminist theories, social constructional and poststructural feminism, shifts from perceiving gender as a variable to perceiving gender as an influence (Calás, Smircich, and Bourne Citation2009). In particular, poststructural feminism is concerned with “how gender power relations are constituted, reproduced and contested” in an effort to understand why women tolerate social relations that subordinate their interests to those of masculinist culture (Weedon Citation1987, pp. vii, 40). Poststructural feminism rejects assumptions of masculine dominance and establishes meanings by using the strategies of opposition, resistance, and deconstruction to reveal and delegitimize patriarchy within societies. Scholars apply a poststructural feminism lens to highlight the social construction of gender through series of individual acts and daily interactions with others (Diaz‐Garcia and Welter Citation2013; Lewis Citation2013). This lens also reveals the diversity of how women do entrepreneurship (Ahl Citation2006). For instance, Galloway, Kapasi, and Sang (Citation2015) emphasize women entrepreneurs' pluralistic tendencies as multiple subjectivities that both influence and shape their interpretations of entrepreneurship.

Galloway, Kapasi, and Sang (Citation2015) propose that the social construction of femininity and masculinity permits the development of culturally produced multiple identities, including entrepreneurial leadership (Calás, Smircich, and Bourne Citation2009). In constructing identities, men and women can draw on masculine and feminine characteristics (Lewis Citation2013) and redefine the social markers of identity, including gender, to create new and multiple identities (Essers and Benschop Citation2009). This feminist perspective offers a coherent approach to the atheoretical nature of knowledge of women's entrepreneurship and enables better understanding of entrepreneurship through women's experiences. This feminist theory also grants women's experiences and behaviors credibility and legitimacy (Ahl and Marlow Citation2012, p. 550). Diaz‐Garcia and Welter (Citation2013) accordingly describe gender identity as a dynamic process in which women entrepreneurs apply complex strategies in their working lives, shift between identities, and adopt various leadership practices depending on the situation.

Responding to frequent scholarly calls for a more explicit use of feminist theory in entrepreneurship studies (Hamilton Citation2013; Galloway, Kapasi, and Sang Citation2015), we adopt a poststructural approach to examine how Lebanese women construct leadership identities within the prevailing sociocultural values and gender ideology. Drawing on feminist poststructural theory allows us to highlight the alternative discourses of entrepreneurial leadership that can aid Lebanese women entrepreneurs in reconceptualizing their leadership roles and performance as both valued and respected. This framing also enables the uncovering and delegitimizing of the discourse of patriarchy that underpins how Lebanese women experience and understand entrepreneurial leadership.

Construction of Identities and Intersectionality

Social constructionist and poststructuralist feminist theories adopt a broad perspective of the process of identity construction and promote the notion of multiple identities. Individuals have inter‐related, evolving, and multiple selves (Sardar Citation2005), and their identities are historically, contextually, and discursively constructed at the intersections of various identity categories (Essers and Benschop Citation2009; Essers and Tedmanson Citation2014). Thus, individuals can have multiple fluid identities that are socially created in a process that depends on time, place, and context (Crenshaw Citation1997; Essers and Benschop Citation2009; Holvino Citation2010; Metcalfe and Woodhams Citation2012). Furthermore, while constructing identities, individuals incorporate symbolic elements such as gender, nationality, language, and cultural practices (Sardar Citation2005).

Women entrepreneurs construct their identities in a similar process. Entrepreneurial identities are usually built in relation to the archetype of a heroic, male, white entrepreneur (Essers and Tedmanson Citation2014, p. 355). Although individuals can exercise agency in identity construction, they are also inhibited by certain discourses and by the intersection of often inseparable social structures, such as gender, ethnicity, and sociocultural values (Crenshaw Citation1997; Metcalfe and Woodhams Citation2012). Studies conducted in specific national contexts show that there is no monolithic archetype of the women entrepreneur; instead, specific contextual differences shape the formation of the different identities and the ways that women entrepreneurs “do gender” and “redo gender” in identity management (Chasserio, Pailot, and Poroli Citation2014; Diaz‐Garcia and Welter Citation2013; Essers and Benschop Citation2009). This research suggests that women entrepreneurs build their professional identities within the dominant gendered discourse of entrepreneurship. By doing entrepreneurship, though, women redo gender and act in ways that challenge not only the normative concepts of what is male and female, but also the hierarchical power structures that often sanction the women for their doing of gender (Calás, Smircich, and Bourne Citation2009; West and Zimmerman Citation1987).

As women entrepreneurial leaders invest in identity construction, they resist the marginalization of their work as entrepreneurial leaders. Many face an ongoing struggle to find their voices and space to position themselves and their work within an unequal masculine domain. Relatively few studies on how women entrepreneurial leaders construct their identities take into account the impacts and roles of context and process. Accordingly, we frame our poststructural analysis of Lebanese women entrepreneurs within intersectionality to add to the traditional debate on entrepreneurship, given that identities are intersectionally constructed (Essers and Benschop Citation2009) and inseparable from other inequalities, such as gender, class, and sociocultural institutional contexts (Crenshaw Citation1997; Holvino Citation2010; Metcalfe and Woodhams Citation2012). We propose that Lebanese women socially construct their identities as entrepreneurial leaders through their own unique narratives, social processes, and social interactions within their society's normative concepts, delimiting what it means to be male and female.

Sociocultural Values and Gender Roles in Lebanon

Women represent a large pool of untapped talent in Lebanon and the Arab world. In the dominant academic discourse on entrepreneurship, patriarchal sociocultural values and associated gender ideologies are negatively related to Arab women's entrepreneurial activities (Al Dajani and Marlow Citation2010; Itani, Sidani, and Baalbaki Citation2011; Tlaiss Citation2014). Although context can be experienced as either a liability or an asset (Welter Citation2011), the literature on Lebanese and Arab women's entrepreneurial experiences generally portrays local sociocultural values and gender ideologies as liabilities that hinder women's career choices. Lebanon is described as a patriarchal, masculine country that favors a traditional division of labor and promotes highly distinct, strictly defined gender roles (Tlaiss Citation2014). From childhood, Arabs learn how to enact and behave according to gender and are expected to adhere to ascribed gender roles and prescribed behaviors stereotyped as male or female (Karam, Afiouni, and Nasr Citation2013; Tlaiss Citation2015a). Most segments of Lebanese society continue to define women by their domestic responsibilities as homemakers, mothers, and wives, and these expectations govern women's socially acceptable career choices (Tlaiss Citation2014).

The centrality of the family and the framing of domestic responsibilities and childcare as female are frequently reported to hinder Arab women's careers (Karam, Afiouni, and Nasr Citation2013; Tlaiss Citation2014). Women who choose to pursue careers outside home generally do so in sectors considered to be socially acceptable, such as education and healthcare, and occupy lower‐level roles and positions (Tlaiss Citation2015a). Arab women are rarely given decision‐making, managerial, or leadership roles simply due to the associations of femininity with caregiving and support (Al Dajani and Marlow Citation2010) and of masculinity with leadership and entrepreneurship (Itani, Sidani, and Baalbaki Citation2011; Tlaiss Citation2015b). Lebanese women occupy less than five percent of senior management positions, are clustered in the lower levels of management (Tlaiss Citation2014), and are discouraged from pursuing entrepreneurial careers or defying socially accepted gender roles. Those who do so, challenge gender conformity and are often subjected to unfavorable social attitudes (Itani, Sidani, and Baalbaki Citation2011). Entrepreneurship studies (de Bruin, Brush, and Welter Citation2007) argue that women entrepreneurs' self‐perceptions are closely linked to the environment in which entrepreneurship occurs. We therefore explore whether and how societal values that discourage women's work and view it as less desirable than men's influence Lebanese women's construction of their entrepreneurial leadership identities and their self‐perceptions as entrepreneurial leaders.

Methodology

Following our poststructuralist feminist perspective and the recommendations of previous studies (e.g., Ahl and Marlow Citation2012), we draw from the interpretive epistemological tradition. The interpretivist approach arises from a life‐world ontology which holds that all observations are value‐ and theory‐laden and that the investigation of the social world cannot uncover objective truth (Leitch, Hill, and Harrison Citation2010, p. 690). This approach allows us to explore, understand, and analyze how the production and reproduction of gender in the daily lives of Lebanese women intersects with patriarchal sociocultural norms and influences their conceptualizations of entrepreneurial leadership and their construction of entrepreneurial leadership identity. Like other small‐scale entrepreneurship studies in the interpretivist tradition (e.g., Essers and Benschop Citation2009; Essers and Tedmanson Citation2014), our objective is not to generalize, and we do not claim that our analysis is representative. The strength of this study lies in its ability to provide insights, rich descriptions, and a detailed understanding of the situational nuances influencing the interviewees' experiences with entrepreneurial leadership (Leitch, McMullan, and Harrison Citation2013). We also aim to generate new, useful, engaging insights into Lebanese women entrepreneurs.

To investigate Lebanese women's experiences as both entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial leaders, an explorative career‐narrative approach using in‐depth, semi‐structured interviews is employed. As Ahl and Marlow (Citation2012) argue, narratives are ideal tools for making sense of the human experience, and the analysis of narratives offers rich insights into entrepreneurs' worldviews and thinking. Narratives also allow us to better comprehend how women entrepreneurs' identities are co‐instituted and located in the repertoires of their culturally situated experiences (Henry et al. Citation2015). To understand how Lebanese women entrepreneurs relate to sociocultural values and gender roles in identity construction, we contextualize their stories with an analysis of the public discourses on culture and gender in Lebanon and the Arab Middle East (AME) region.

Sample and Procedures

In‐depth, semi‐structured, face‐to‐face interviews were conducted with 21 Lebanese women entrepreneurs. An entrepreneur was operationalized as an individual who owned and managed a business and thus was self‐employed (Tlaiss Citation2015a, Citation2015b). As shown in Table , five of the 21 interviewees were 30–40 years old, nine were 40–50 years old, and seven were more than 50 years old. Regarding educational attainment, nine had master's degrees, and seven had bachelor's degrees. Considering marital status, one interviewee was single, four were divorced, and 16 were married, while nine had two children, and seven had three children. Table shows that all the women entrepreneurs had been in business for longer than eight years, and more than 50 percent in business for 10 years, except for two who had been in business for seven years. All the interviewees had at least eight employees and operated businesses in the services sector.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of the Interviewees and Their Businesses

Obtaining cooperative access to information for analysis (e.g., data collection) continues to be among the most difficult aspects of conducting research in both Lebanon and the AME. Databases on women entrepreneurs in Lebanon are nonexistent. This challenge is intensified by women's reluctance to participate in a research study. Together, these factors prevent recruiting a conventional sample (Al Dajani and Marlow Citation2010; Itani, Sidani, and Baalbaki Citation2011). Consequently, researchers must use their personal contacts and social networks to gain access to the needed information. A mixed sampling strategy, therefore, was employed in this study. The participants were recruited using purposive approaches that capitalized on the researchers' personal networks of potential leads, chain referrals, and snowballing (Cohen Citation2006; Patton Citation2002). This approach generated a non‐probability sample that was neither fully representative nor random but, rather, a varied sample of interviewees willing to share information concerning the topic studied (Cohen Citation2006). Using the first author's personal connections, the researchers contacted women who were entrepreneurs themselves and individuals who knew Lebanese women entrepreneurs and were willing to make referrals. Initial contact with the prospective interviewees was made by telephone to explain the objectives of the study, assure the participants of absolute anonymity for both themselves and their responses, and elaborate on the dissemination channels for the collected data.

The first author conducted all the interviews. To facilitate trust and elicit candid responses, the researcher established rapport with the interviewees. The researcher began each interview by thanking the interviewees for their participation and then discussed confidentiality and informed them of how the data collected would be disseminated. These assurances were crucial to convincing the interviewees to share their experiences. After soliciting personal and organizational demographic information, the interviewer encouraged the interviewees to share their stories regarding their careers and experiences as entrepreneurs. Guided by the research objectives and responding to the interviewees' narrative and dialogue, the following questions were asked: Do you perceive yourself as an entrepreneurial leader? Why or why not (what are the reasons underlying your perceptions)? Depending on the interviewees' answers, the researcher asked further questions to elicit comments on the interviewees' entrepreneurial identities and the role of sociocultural factors and gender ideologies. The women were encouraged to talk about their experiences, the challenges they faced as women in a male‐dominated Arab environment, and the coping strategies/mechanisms they used to meet the challenges unique to their identity as entrepreneurial leaders.

Analysis

The interviews lasted 60–120 minutes, were tape recorded, and were conducted at locations selected by the interviewees. Additionally, the interviewees could choose to be interviewed in Arabic, French, or English. The interviews conducted in French and Arabic were translated into English by one of the researchers and then back‐translated and cross‐validated by an academic fluent in all three languages. The researchers and an independent researcher transcribed the interviews. To ensure respondent validation, the interviewees reviewed their respective transcripts for accuracy.

The interviews were subjected to thematic analysis. As suggested by Gherardi and Poggio (Citation2007), we first analyzed “how” the interviewees perceived themselves (as entrepreneurial leaders or not), then the “why” underlying these self‐perceptions, and, finally, “what” processes the women used to build their entrepreneurial identities. An initial code book (Leitch, Hill, and Harrison Citation2010) with a number of broad themes was created based on the literature review (Glaser and Strauss Citation1967; Strauss and Corbin Citation1990). The interview manuscripts were read and scrutinized by the researchers, who independently coded them. The coding process focused on highlighting the unique statements the interviewees used to discuss their experiences and answer the questions. Then, the codes created by the researchers were compared to the preliminary list of codes (Miles and Huberman Citation1994) and among the researchers to identify the convergence and divergence of themes. Axial coding was conducted for any divergence or new theme. The initial code book was modified to account for the new themes and the relationships between them (Al Dajani and Marlow Citation2010; Strauss and Corbin Citation1990) until the final coding template was created. If and when a theme recurred frequently, content analysis was utilized, as suggested by Ahl (Citation2006). Content analysis also helped achieve a quantifiable perspective that, as de Bruin, Brush, and Welter (Citation2007) argued, could broaden the understanding of entrepreneurship.

To ensure the integrity and reliability of the data, the researchers followed Lincoln and Guba's (Citation1985) suggestions. First, they recruited peer researchers with expertise in qualitative research from their own departments and institutions and from other universities to conduct an audit of the empirical process. Second, to obtain outsiders' perspective and to review the researchers' ideas (Corley and Gioia Citation2004), the researchers invited peers to crosscheck and pose critical questions about the analysis process. Third, peer researchers not involved in the study reviewed the data for emerging patterns. Finally, to assess whether the conclusions were reasonable, the expert peers reviewed the interview protocol, coding structures, and a random sample of the transcribed interviews (Corley and Gioia Citation2004).

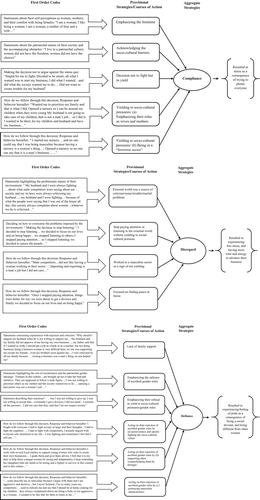

Moreover, following the iterative function outlined by Pratt, Rockmann, and Kaufmann (Citation2009), the data concerning the interviewees' construction of entrepreneurial leadership identities were analyzed by going back and forth through the transcripts (Locke Citation2001; Miles and Huberman Citation1994; Strauss and Corbin Citation1990). This process lead to the emergence of three major strategies. As suggested by Pratt, Rockmann, and Kaufmann (Citation2009), this process involved three major steps. Step 1 entailed the creation of first‐order codes. The researchers first examined the informants' statements through open coding (Locke Citation2001) and then aggregated common statements to form first‐order codes (Pratt, Rockmann, and Kaufmann Citation2009). After construction of the codes, the data were reviewed again to see whether they fit into the categories, and the codes were revised when the data did not fit well. In Step 2, axial coding was conducted (Locke Citation2001; Pratt, Rockmann, and Kaufmann Citation2009; Strauss and Corbin Citation1990). The interviewees' responses were compared, and the data were compiled into different themes/courses of action/provisional identity‐building strategies. For example, some Lebanese women entrepreneurs' statements about their reactions to sociocultural barriers indicated that they were not willing or planning to fight the status quo. Accordingly, the category “Decision not to fight” was formed to capture these reactions. In Step 3, to understand how these different provisional strategies fit together, the researchers looked for aggregate strategies underlining the courses of action generated in Step 2, following the suggestions of Pratt, Rockmann, and Kaufmann (Citation2009, p. 240). The researchers agreed upon the final aggregate strategies after several deliberations and brain‐storming sessions seeking to better understand how the courses of action related to each other and to the literature. Figure 1 summarizes the process used to arrive at the aggregate strategies.

Results and Discussion

This section presents the Lebanese women's narratives of how they personally identify with the concept of entrepreneurial leadership.Footnote4 Analyzing these narratives through a poststructural feminist lens enabled us to provide accounts of how the women's experiences and their personal identification with the concept of entrepreneurial leadership evolve in a web of intersecting patriarchal and sociocultural values and gender ideologies, on one hand, and their desire to excel, on the other. These narratives also enable seeing the subjectivities the women use and how they enact these subjectivities through their individual agency, multiple identities and sense of self as they navigate their complex local contexts and prescribed gender.

Self‐Perception as Entrepreneurial Leaders

Asked whether they perceived themselves as entrepreneurial leaders, 16 of the 21 women interviewed state that they do. Self‐perceptions as entrepreneurial leaders are attributable to the women's individual entrepreneurial career paths and the ways that they navigate their careers amid discriminatory gender ideologies and patriarchal sociocultural values. The women experience the strict gender roles and patriarchal culture as barriers. Their decisions to create their own businesses are perceived as socially unacceptable because (1) women in Lebanon are socially and culturally expected to prioritize their family obligations, and (2) entrepreneurship or business ownership is considered to be a man's job. Consequently, by creating their own businesses, the women in this study are perceived as socially rebellious and denied family and societal support. The following quotations describe the women's views regarding their social rebellion and consequent lack of familial support.

I, [therefore], am an entrepreneurial leader because I took leadership of my life and career and established my own business. But that is not it! … I was among the first to do this, and the men were always making my life difficult, saying bad things about me and offering services at lower prices. But I was not willing to give up so I kept at it.… So, yes, now I can proudly say that I am an entrepreneurial leader. (LWE 21)

Yes … because I managed to break the social rules and create a successful business in a male‐dominated industry. (LWE 17)

Sure, I am. … You need to remember that we are living in an Arab community where people see a woman only as a mother and a wife. Women at that time were not allowed to have their own businesses because men worked outside [the home].… But I had a vision for this place, and I was not willing to give it up.… I was criticized by all my family because things were not as they used to be. Owning a business was a man's thing.… My business stood the test of time and is now better than that of men. (LWE 4)

These quotes show that the participants' perceptions of themselves as entrepreneurial leaders are strongly influenced by (1) their pioneering efforts to overcome sociocultural barriers through hard work; (2) taking control of their lives; and, (3) most importantly, starting their own businesses in male‐dominated industries. The women's narratives also stress how the experience of discrimination, resistance, and lack of family support drive them to work harder to grow their businesses and assert themselves and their career choices. Differing societal expectations for women and men are clearly manifested in the traditional attitudes of the male competitors who tried to destroy the women's businesses.

For so many years, my competitors were only men who tried to put me down with gossip and negative comments about me or my management style or stealing my employees and so on. (LWE 16)

Five women (LWE 1, 9, 12, 13, and 20) were hesitant to state whether they perceive themselves as entrepreneurial leaders, but their reluctance does not lead them to proclaim themselves to be non‐leaders. After hesitating, two (LWE 1 and 12) agree that they consider themselves to be leaders, while three provide alternate descriptions of themselves without calling themselves non‐leaders. These interviewees explain their hesitation through discriminatory sociocultural values and gender roles.

I am not sure. I mean, I know that I am strong because I managed to start my business, and it survived the difficult phases. … See, as a woman, my priorities should be my children, husband, and, of course, my family and my husband's family. I think that, because I am working for myself, I can be there and do these things.… So maybe I am an entrepreneurial leader because I made my business, and it is good, and because I raised a good family. (LWE 1)

As a woman, being an entrepreneurial leader is a big thing.… To be a woman and an entrepreneurial leader here in this patriarchal culture is a lot.… I mean, no matter what you do, what is important is being a good mother and a good wife. … Even if I think I am an entrepreneurial leader, I don't think that society will. (LWE 13)

These quotations from the hesitant group show their reluctance to perceive themselves as entrepreneurial leaders without also asserting their motherhood role. Their reluctance demonstrates the influence of gender socialization and the deeply engrained gender ideologies. These prevent the women from celebrating their career choices without also showing compliance with gendered expectations. Their hesitation also demonstrates the extent to which their self‐perceptions (de Bruin, Brush, and Welter Citation2007) are negatively affected by the societal values that do not accept or support women's entrepreneurship and restrict them to roles related to the family and the home.

Seen through a poststructural feminist lens, the narratives of both groups demonstrate that cultural norms do not leave Lebanese women free to perform their gender as they desire. Moreover, these cultural norms restrict women's entrepreneurial ventures, denying them support from both family and society. These narratives illustrate how women's entrepreneurial work is perceived as less legitimate than that of their male counterparts. The women's individual narratives recount experiences of both implicit and explicit bias. The majority of women speak of the social and cultural biases they face and how they choose to deal with these biases. This process of discernment plays a role both in how they cope with such biases and in how they self‐identify as entrepreneurial leaders.

Fueled by their rejection of the strict, dominant gender roles and patriarchal sociocultural values (Afiouni Citation2014; Al Dajani and Marlow Citation2010; Itani, Sidani, and Baalbaki Citation2011; Karam, Afiouni, and Nasr Citation2013; Tlaiss Citation2014), the Lebanese women entrepreneurs choose alternative, nontraditional career paths. Pursuing their career choices and shaped by their individual battles, the women in this study construct their perceptions of entrepreneurial leaders based on their own self‐conceptualizations. The women's personal accounts, therefore, demonstrate how their self‐identity evolves in the intersecting web of patriarchal and sociocultural values, gender ideologies, and the personal desire to excel. These narratives also show that the women reconcile themselves to this perpetual internal conflict of trying to resolve the demands imposed upon them by society and others. Even while perceiving themselves as successful entrepreneurs, the women still feel that they must negotiate sociocultural complexities and respond to society's expectations. Similar findings are reported in other studies conducted in the Arab world (e.g., Al Dajani and Marlow Citation2010; Itani, Sidani, and Baalbaki Citation2011), confirming that the pressures of sociocultural values act as barriers to women's entrepreneurial careers. Accordingly, we argue that the poststructuralist feminist approach within this intersectional framework facilitates our understanding of how the interviewees' self‐reported perceptions of entrepreneurial leadership are inseparable from other social categories.

Construction of Entrepreneurial Identity and Entrepreneurial Leadership Identity

Being women, entrepreneurs, wives, and mother poses dilemmas and problems for the women in this study. All the interviewees criticize the traditional approaches to gender, the masculinization of the entrepreneurial career path, and negotiate their identities in relation to their entrepreneurship. While seeking entrepreneurial legitimation, the women display three forms of identity construction strategies: compliance and adaptation, disregard, and defiance and resistance.

Compliance

In contrast to the widespread discourse on women's entrepreneurship (Itani, Sidani, and Baalbaki Citation2011), the five women in this group (LWE 1, 9, 10, 14, and 20) find it possible to be women, mothers, and entrepreneurs. This group of women criticizes but does not resist gender discrimination. They find compliance and conformity with gendered norms to be the optimal means to advance their entrepreneurial careers. These women do not fight their culture but gain agency by negotiating and conforming with cultural prescriptions, even focusing on dedication to their families and compliance with ascribed gender roles. This strategy proves to be demanding, taxing, and stressful as the women attempt to please everyone (i.e., their families and society) while pursuing their dreams of owning their own business and fulfilling the additional responsibilities that that alone entails.

I am a woman, and I live in a patriarchal culture. It is stupid for me to fight, so I decided to be smart.… They [society and cultural expectations] want me to prioritize my family, and this what I did.… I opened a nursery, so I could be around my children when they were young, and when they went to school, they would come to me to the nursery, and I could take care of them.… So I did what I wanted, and I have my own business and did what society wanted me to do.… I often feel tired.… I always have a lot to do.… I am stressed out about my business and my husband and my children. (LWE 9)

I like being a woman, and I don't want to be rough or loud or masculine. … When I created my business, I opened a nursery, so no one can say that it was a man's business. Here, they think that children should be around women, especially when they are young. … I always emphasized how committed I am to my family and motherhood, so when the mothers and fathers came to drop off their children, they felt safe about their children, and that made me look as a good woman and mother. (LWE 20)

This group of women constructs their entrepreneurial identities by minimizing social rejection and by soliciting social approval through various means. Cognizant that their entrepreneurial interests are socially frowned upon, as explained in the previous section, these women attempt to reduce the risk of societal rejection by establishing conventional feminine ventures (nurseries and esthetics centers). They also exhibit socially appropriate behavior by focusing on and prioritizing their role as mothers and wives over that of entrepreneurs. As entrepreneurs, they use the flexibility of their work schedules to reconcile their family obligations with the demands of self‐employment. Accordingly, we argue that self‐employment serves as a coping strategy allowing the women to combine employment with being good mothers and wives, as suggested by Calás, Smircich, and Bourne (Citation2009). Thus, by choosing to accept gender norms and pursue an entrepreneurial career in a perceived feminine sector, these women can better fulfill their desire for entrepreneurial careers without sacrificing an acceptable work–life balance. Furthermore, prioritizing their motherhood/wifely/feminine identity enables these Lebanese women entrepreneurs to smoothly navigate the local gendered expectations to create and legitimize their entrepreneurial identities. By conforming to their society's gendered norms, these interviewees stretch the boundaries of what is acceptable for a woman to do within their local context. These findings, therefore, support previous studies (Afiouni Citation2014; Tlaiss Citation2014) highlighting the negative impact of societal expectations on Arab women. They also align with Essers and Tedmanson's (Citation2014) findings that Turkish women in the Netherlands develop their entrepreneurial identities and advance their careers by embracing societal gender roles and expectations and behaving in an appropriate feminine manner.

Disregard

Compared to the compliance group, the women in this group (LWE 7, 12, and 13) opt for what they find to be a more acceptable balance between compliance and resistance which they achieve through disregard to society and cultural expectations. These women's entrepreneurial identities assert some independence from patriarchal views because they operate in the traditionally masculine sectors of clothing and import/export. They do not conform to gender role stereotypes but, nevertheless, do not want to openly resist societal expectations. Alternatively, they cultivate their identities by deliberately distancing themselves from their controlling society.

I decided to stop listening.… My husband and I were always fighting because I was very nervous about what my male competitors were saying about me and all their rumors because they did not like having a woman working in their sector.… Society and my in‐laws were always criticizing my husband.… We were about to get a divorce, and finally, we decided to focus on our lives and on being happy.… We stopped listening to others, and we stopped allowing them to influence us. (LWE 7)

Although my children were big when I started my business, my husband and I were fighting because he said that I was not paying enough attention to the children … and because … people were saying that I was out of the house all day. … So we decided to ignore people. … I also try to find a happy medium. … During the high season, I let them know that I will be away or late, and I make sure that I spend quality time with them. … During the low season, I work from home and am always there when my children come back from school or university and when my husband comes back from work. (LWE 12)

Whereas the compliance group's strategy is based on gaining acceptance by complying with societal expectations, the disregard group exhibits independence by distancing themselves from their society. Concerned principally with isolating themselves from societal gender stereotyping, this group's narratives highlight their efforts to detach themselves. However, unlike their compliance counterparts, the disregard group seeks to achieve work–life balance through time management and compromise. Attempting to reconcile imposed societal expectations by juggling their careers and family responsibilities (Tlaiss Citation2014), these interviewees remain true to themselves as women and as entrepreneurial leaders. This strategy allows them to focus on career advancement, and consequently, they experience less stress in their lives, especially compared to the compliance group who seek to please everyone.

By choosing to distance themselves and to disregard discriminatory societal expectations and negative stereotypes, these women defend themselves against gendered norms and precepts. They symbolically create a boundary between themselves and their un‐egalitarian society. Such boundary work, according to Essers and Benschop (Citation2009), is a type of identity work; individuals highlight their differences to create boundaries between themselves and other groups. To deal with societal expectations, this group of women crafts their entrepreneurial identities by drawing boundaries between themselves and their businesses and society. Hence, we argue that boundary work enables them to determine their entrepreneurial identities and to extend the boundaries of social acceptability to include their leadership, entrepreneurship, and work–life balance.

This group's narratives support previous studies conducted in Lebanon and the AME (Al Dajani and Marlow Citation2010; Tlaiss Citation2015a) finding that, to construct identities, women must navigate ascribed gender roles and their maternal duties. The path taken by the women in this group to form their identity by establishing boundaries or drawing lines of separation shares commonalities with the path taken by Muslim women entrepreneurs who create their entrepreneurial identities by generating boundaries and distancing themselves from the Muslim community and its rules (Essers and Benschop Citation2009). These interviewees' responses highlight how they cope and deal with societal expectations while constructing their entrepreneurial identities. Previous studies (e.g., Essers and Tedmanson Citation2014) show that the intersections between different identities and specific societal expectations can give rise to conflict, as seen in the stories of our interviewees. In other words, the Lebanese women entrepreneurs who operate within a context that values masculinity are more likely to experience conflict between their identities as women, mothers, and entrepreneurial leaders.

Defiance

Most of the Lebanese women entrepreneurs in this group (13 of 21 interviewees, including LWE 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 11, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, and 21) legitimize themselves as entrepreneurial leaders by (1) rejecting social norms and assumptions and (2) voicing dissent from the ascribed gender roles and the normalization of the masculine discourse. Complete rejection and defiance of the societal assumptions operating within a complex system of oppression and discrimination forms the core of this group's identity construction, especially in comparison to the compliance and disregard counterparts. The defiance group objects to and outright disapproves of any form of gender discrimination and demonstrates agency by resisting conventional norms and societal expectations. Whereas the compliance group chooses to negotiate cultural prescriptions, and the disregard group to distance themselves from their patriarchal masculine society, the defiance group breaks gender stereotypes and asserts agency by claiming equal rights. In constructing identities as entrepreneurs, these interviewees openly and vocally reject societal perceptions of women as less suitable than men or not at all suited for entrepreneurship. These women also embrace their socially deviant or nonconforming status. Unlike the disregard group, the women in the defiance group seem to be comfortable constructing their own identities of what it means to be an entrepreneurial leader. To that end, they redo gender (Diaz‐Garcia and Welter Citation2013) as they act in ways that do not fit the norms governing females, thereby challenging the social hierarchy and power structures. Their narratives reveal how their experiences constructing their identities and redoing gender as a strategy intersect with the sociocultural context as they create their own self‐perceptions as entrepreneurial leaders.

The women in this group thus resist societal pressures and react with active agency, which they internalize as an empowering experience. The discriminatory values in the Lebanese sociocultural context do not negatively affect these women's self‐perceptions, as argued in previous studies (de Bruin, Brush, and Welter Citation2007), but motivate them to work harder to validate their career choices as entrepreneurs. This approach allows these women to differentiate themselves from the majority of the Lebanese women who comply with social expectations.

Females in this culture, from the time they are young, are brought up not to take the lead and initiative. They are supposed to follow their husbands. It kills the spirit of entrepreneurship to follow a male figure, whether a politician, husband, father, or brother. I was not willing to prioritize others as my mother and society wanted me to do.… Plus, why should I support my husband when he was not willing to support me? … I was not willing to accept that. … Eventually I got a divorce because my husband wanted me to focus on his needs and support him … and he was listening to what his family and society were saying. (LWE 19)

My husband and my family did not approve of me having my own business.… Opening a hair parlor was not a woman's job.… My father said that, if I wanted to work, I should get a job in a bank or as a teacher but not doing business.… But I was not willing to give up.… I fought with everyone. No one was supporting me, except my friends.… Even my brothers were against me.… I had to fight society at large and their thinking that I was selfish and a bad mother and a negligent wife because I was focusing on my new business.… I had to fight the suppliers and prove to them that my business would succeed even though I was a woman and did not have male partners.… I had to fight with competitors who were making fun of me and my lack of business experience and starting a price war against me. (LWE 6)

In my experience, every woman in Lebanon who decides to open her own business and … go against society is an entrepreneurial leader.… Being a businesswoman is very difficult here … but I did not mind.… I resisted all the pressure. … I did not care that they said that I did not respect society or that I would not be a good mother.… I actually argued with everyone who interfered in my life.… I was fighting, and sometimes I feel that I still am.… I spent all my savings and borrowed money because I was not willing to give up.… I knew that I had it in me and that I was better than what everyone was saying.… I knew that being a mother and a wife did not mean I cannot have a good business. (LWE 11)

These narratives reveal the types of challenges this group of women faces, how they make sense of these challenges, and what strategies they use in building their identities. The interviewees' narratives also show that they do not denigrate or gender stereotype other women; they do not exhibit the Queen Bee attitude attributed in recent research in psychology to successful women in masculine cultures who distinguish themselves from other women by denigrating and gender stereotyping them (Derks et al. Citation2011; Mavin Citation2008). To the contrary, this group of women empowers other women by employing them and helping them become financially independent. Despite intense pressure to conform, the women in this group focus on their individual effort and agency and do not mention reliance on specific external support mechanisms. Their narratives reiterate statements such as “No one helped me,” “I borrowed money,” and “I had to fight.” Perhaps due to the lack of external support mechanisms, these women choose to support other women as a further rejection of social conformity. In contrast to a Queen Bee who perpetuates gender stereotyping of other women (Derks et al. Citation2011; Mavin Citation2008), this group aims to instill their views on gender equality and agency in younger generations. In their narratives, the interviewees discuss their committee work with nonprofit organizations supporting women entrepreneurs with information, seed money, and assistance. The mothers in this group frequently refer to teaching their daughters to be strong and resilient, to never feel or accept inferiority to men, and to always fight for their rights. Similarly, Essers and Benschop (Citation2009) show that Moroccan women entrepreneurs construct their entrepreneurial identity through rebelling and fighting for women's rights.

All my employees are women, except my drivers. … I feel that it is my duty to help these younger women be strong and independent. (LWE 18)

Since she [my daughter] was very young, I have always taught her to say no … not to allow others to tell her what to do. … Even now, I keep reminding her that she needs to be strong and a fighter to survive in this country and in this culture. … It is very important to teach girls this at home because they do not learn this at school, and society only teaches them to be second‐class citizens. And I refuse to have my daughter think like that because men and women are equal. (LWE 5)

I work with several local entities to support young women who want to create their own businesses.… I try to go there twice a week and talk to these potential women entrepreneurs.… I guide them and give them advice.… We are also working with several banks to get them to offer these women low‐interest loans to start their businesses.… I feel that I owe it to help them.… No one helped me, so I help others. (LWE3)

The Lebanese women entrepreneurs in this group used masculine qualities without renouncing their femininity. While constructing their entrepreneurial leadership identities, the defiant group exhibits both feminine and masculine traits on an ad hoc basis. The adoption of masculine traits, such as assertiveness and dominance, is motivated by the women's need to be heard by their masculine society and to be taken seriously by their male competitors. However, their use of masculine traits further complicates their identity‐construction strategies by violating the communal traits prescribed to women by gender‐role norms (Carli, Citation1999). This behavior also aggravates their relationships with their male counterparts, who tend to see women who assert a high degree of agency as too agentic to be influential. Caught in a struggle to stay true to their ascribed gendered role while emulating masculine norms, the women adopt male traits to avoid being perceived as deficient, soft, or incompetent as entrepreneurs or entrepreneurial leaders. This effort resonates with the struggle of many women entrepreneurs with their femininity and others' negative perceptions of them based on the masculine normative discourse, expressed in social criticism (Ahl Citation2006; Ahl and Marlow Citation2012; Calás, Smircich, and Bourne Citation2009; Kelan Citation2009; Lewis Citation2013). Hence, we argue that this group of women encounters a “double bind” (Carli Citation1999): although good leaders are expected to be agentic, the agentic women leaders in this study are censured for demonstrating too much agency and insufficient femininity.

Drug distribution is male dominated in Lebanon.… They [male competitors] expected that, because I am a woman, they would be able to boss me around or put me down.… Some describe me as masculine because I argue with them, and I am aggressive and decisive.… I used them [these qualities] because I think I need them to do business, and every businessperson should be like that when the situation requires being like that. (LWE 8)

For so many years, my competitors were only men.… Sometimes when we used to meet at international exhibitions, they used to ridicule me and say that I should be at home cooking for my children.… When we used to co‐manage or plan events, they always complained about me being a bully or too aggressive as a woman.… I needed to be like that for them to listen to me because, if I am not, they will think that I am too soft, and they can boss me around. And I was not willing to let them do that to me. (LWE 15)

To conclude this section, we argue that the dynamic intersections between the women's lives and their sociocultural environments result in a multifaceted identity‐construction process. Our poststructural feminist analysis reveals the complexity of gendered dynamics within Lebanese society and confirms that the women's construction of their entrepreneurial identities is contextually driven. Moreover, the analysis reveals how the women simultaneously reinforce and challenge gendered power relations. Whereas some women do gender and try to fit in with established cultural practices and gendered norms, still others redo gender to disrupt gendered norms. This analysis brings to light how Lebanese women comply with, disregard, and defy sociocultural values and gender ideologies to build their identities as entrepreneurial leaders.

Concluding Remarks

This pioneering study reveals the heterogeneity and complexity of Lebanese women entrepreneurs' experiences of entrepreneurial leadership, agency in the face of gender discrimination, and internalization of sociocultural values and ascribed gender roles during the construction of entrepreneurial identities. The analysis illustrates how the Arab women seeking entrepreneurial legitimation use compliance, disregard, and defiance strategies to construct their identities. This article, thus, makes manifold contributions.

First, we aid in the development of the small but growing field of entrepreneurial leadership theory by addressing the need for contextually embedded research and gender studies within local contexts. To the emerging area of entrepreneurial leadership, we contribute gender research exploring how Lebanese women perceive themselves as entrepreneurial leaders. Our research demonstrates how women's entrepreneurship can best be explored, approached, and understood in its societal context. By exploring gender in the context of Arab women's entrepreneurial leadership and lived practices, we examine this concept from a unique perspective. This approach grants greater recognition that women's entrepreneurial experiences outside the Anglo‐Saxon contexts are worthy of investigation in their own right. By focusing on the Arab women of Lebanon, we support two decades of scholarly work demonstrating that current conceptions of entrepreneurship are not universally applicable across either gender or culture.

We empirically demonstrate that Lebanese women's experiences of entrepreneurial leadership reflect their struggles with societal and cultural constraints and limitations. Their entrepreneurial leadership, therefore, is built on (1) their personal status as pioneers, women who persevered to make their dreams a reality in an unsupportive, masculine environment; and (2) the realization of their dream in building successful businesses that have survived social rejection, obstacles, and financial difficulties. The Lebanese women's experiences of entrepreneurial leadership are deeply integrated into their identity creation as they seek to overcome their local culture's gendered discrimination and restrictions to prove themselves as entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial leaders. Put another way, their journey to claim entrepreneurial leadership goes hand in hand with their journey to create their entrepreneurial identities while navigating the obstacles in their local society. Their efforts provide a means to understand why some women entrepreneurs reject the dominant discursive practices within the Lebanese society and how entrepreneurial leadership unfolds through the voices of women in the AME. Through their own unique entrepreneurial encounters, Arab women voice their insights concerning social inequality, hardship, exclusion, and gender stereotypes.

Second, this study provides unique insights into gender and the construction of entrepreneurial leadership. In bringing together feminist and gender research within an intersectional framework, this study provides greater understanding of the ways in which women's socially constructed subjectivities interlock with patriarchal sociocultural values. The study's poststructural feminist lens enables better understanding of how the women construct their identities in relation to who they are and the choices they make in their journey to becoming entrepreneurial leaders. Through this exploratory process of identity construction, we can better discern the dominant discursive ways through which entrepreneurial leadership functions are understood.

Moreover, we uncover how diverse the strategies utilized by women in dealing with oppression are. Thus, we answered the scholarly calls (e.g., Ahl Citation2006; Calás, Smircich, and Bourne Citation2009; Galloway, Kapasi, and Sang Citation2015; Harrison, Leitch, and McAdam Citation2015; Henry et al. Citation2015; Lewis Citation2013) for more feminist theorizing of entrepreneurship and for entrepreneurial leadership research showing how gendered subjectivities are socially created and produced by intersectionality. We concur with Essers and Benschop (Citation2009), demonstrating that the Lebanese women entrepreneurs' identities are dynamic co‐constructions shaped by intersections with diverse social‐identity categories. This work helps to understand how women draw on various feminine and masculine traits on as‐needed basis to claim legitimacy, not only for themselves but also for their entrepreneurial careers, leadership status, and businesses. Moreover, as ascribed gender roles pull the women in one direction, and their ambitions in another, their identities become more than the sum of their womanhood, entrepreneurship, and gender roles. In this case, the women perform extensive identity work at the intersection of gender identity and sociocultural roles within entrepreneurship to create agency and cope with these structural inequalities. Our conceptual framework reflects such identity constructions because we argue that the subjectivity in identity‐building influences the act of entrepreneurial leadership. Entrepreneurial leadership, therefore, is conceptualized as individuals' ability to develop their entrepreneurial identity in a social context and couple it to and with acts of leadership.

Third, within entrepreneurial contexts, we advance the understanding of identity work to scrutinize the complexity of gendered dynamics and how they exist and intersect. Following Essers and Benschop (Citation2009) and Sveningsson and Alvesson (Citation2003), our study expands the overall understanding of how different socially constructed identities pave the way for the boundary work performed by women in the AME region to construct their entrepreneurial identities and affirm their leadership status. In our study, boundary work stands as one of the strategies women use to negotiate their entrepreneurial identities while accommodating societal gendered expectations. Consequently, we show how women can create symbolic boundaries between themselves and societal expectations without losing their independence, agency, and equality; rather, they can use such boundaries to assert themselves as entrepreneurial leaders.

Finally, this article contributes to practice through its detailed narratives describing the process of self‐reported entrepreneurial leadership, including features related to small businesses. We also contribute to the understanding of entrepreneurial leadership by identifying a need to investigate this activity separately and in relation to other entrepreneurial experiences, such as identity construction. Together with Galloway, Kapasi, and Sang (Citation2015), we argue that a more nuanced understanding of this field can be achieved if studies of entrepreneurship shift from perceiving entrepreneurship and leadership as individual properties to viewing entrepreneurship, including entrepreneurial leadership and identity, as situated experiences. The challenge for policy and practice, therefore, is to recognize that the nature of entrepreneurial leadership is changing and that women's entrepreneurial identity is not based within themselves but is crafted in interaction with their society and environment. In recent years, countries, including some AME nations, have invested in promoting entrepreneurship to increase employment and to strengthen local economies. This study provides important implications for the outcomes of these investments and initiatives. Governments and other decision‐makers charged with drafting policies to promote entrepreneurship can outline policies and programs addressing the obstacles highlighted in this study. Specifically, Arab countries can use these findings to tap into the underutilized entrepreneurial talents of Arab women to boost economic growth and development.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Interesting avenues for reproducing and expanding these findings exist given our initial data. Due to the difficulties of data collection in the Arab world, our theorization is based on interview data and purposeful sampling. Using a qualitative approach increased our understanding of how women entrepreneurs make sense of their world and individual entrepreneurial experiences, but this sampling approach and sample size can yield only a peek of the bigger picture. Therefore, we strongly encourage those interested in this topic and region to triangulate qualitative and quantitative methods to further develop the understanding of the different means by which women perceive and construct their entrepreneurial identities. More highly contextualized research with larger data sets using a triangulation method is recommended to capture a more robust understanding of women's entrepreneurship within developing countries. Furthermore, although we reference and compare our findings with those reported in other studies concerning the identities of women entrepreneurs in other contexts, our main focus is understanding and highlighting the individual and unique experiences of the Lebanese women. We, along with other scholars, need to consider further exploring how the entrepreneurial identity‐building process of women entrepreneurs differs and is similar to that of men in diverse contexts. Future studies could also investigate the entrepreneurial experiences of Lebanese and Arab women in greater detail. Equally interesting for future research would be exploring similarities and differences based on religious affiliation (equal numbers of Muslims and Christians participated in this study) and investigating the influences of Islamic teachings on Lebanese Muslim women entrepreneurs' experiences of entrepreneurial discourse. In conclusion, exploring the constituents and the antecedents of Arab women entrepreneurs' identities, as well as the traits that define and sustain them, could make for an intriguing study. Such research would address the macro‐issues that Arab women face across the region and enable generalization of the findings.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Hayfaa A. Tlaiss

Hayfaa A. Tlaiss is the chairperson of and an associate professor in the Department of Management at the College of Business, Alfaisal University.

The authors thank the associate editor and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback. They also thank the research ethics committees at their institutions of employment for approving the applications to conduct this research. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2015 ISBE Annual Conference in Glasgow, Scotland.

Saleema Kauser

Saleema Kauser is a lecturer at the Organizational Behavior Group at the Alliance Manchester Business School, University of Manchester.

The authors thank the associate editor and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback. They also thank the research ethics committees at their institutions of employment for approving the applications to conduct this research. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2015 ISBE Annual Conference in Glasgow, Scotland.

Notes

4. Throughout the results section, the acronym “LWE” refers to Lebanese women entrepreneurs. The numbers following the acronyms indicate the interviewees whose names are not revealed to maintain their anonymity.

References

- Afiouni, F. (2014). “Women's Careers in the Arab Middle East: Understanding Institutional Constraints to the Boundaryless Career View,” Career Development International 19(3), 314–336.

- Ahl, H. (2006). “Why Research on Women Entrepreneurs Needs New Directions,” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 30(5), 595–621.

- Ahl, H., and S. Marlow. (2012). “Exploring the Dynamics of Gender, Feminism and Entrepreneurship: Advancing Debate to Escape a Dead End?,” Organization 19(5), 543–562.

- Al dajani, H., and S. Marlow. (2010). “Impact of Women's Home‐Based Enterprise on Family Dynamics: Evidence from Jordan,” International Small Business Journal 28(5), 470–486.

- Bamiatzi, V., S. Jones, S. Mitchelmore, and K. Nikolopoulos. (2015). “The Role of Competencies in Shaping the Leadership Style of Female Entrepreneurs: The Case of North West of England, Yorkshire, and North Wales,” Journal of Small Business Management 53(3), 627–644.

- Brush, C. G., A. de Bruin, and F. Welter. (2009). “A Gender‐Aware Framework for Women's Entrepreneurship,” International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship 1(1), 8–24.

- Calás, M. B., L. Smircich, and K. A. Bourne. (2009). “Extending the Boundaries: Reframing ‘Entrepreneurship as Social Change’ through Feminist Perspectives,” Academy of Management Review 34(3), 552–569.

- Carli, L. L. (1999). “Gender, Interpersonal Power, and Social Influence,” Journal of Social Issues 55(1), 81–99.

- Carli, L. L. (2001). “Gender and Social Influence,” Journal of Social Issues 57(4), 725–741.

- Chasserio, S., P. Pailot, and C. Poroli. (2014). “When Entrepreneurial Identity Meets Multiple Social Identities: Interplays and Identity Work of Women Entrepreneurs,” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Research 20(2), 128–154.

- Cohen, L. (2006). “Remembrance of Past Things: Cultural Process and Practice in the Analysis of Career Stories,” Journal of Vocational Behavior 69, 189–209.

- Cope, J. (2005). “Toward a Dynamic Learning Perspective of Entrepreneurship,” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 29(4), 373–397.

- Corley, K. G., and D. A. Gioia. (2004). “Identity Ambiguity and Change in the Wake of a Corporate Spin‐off,” Administrative Science Quarterly 49(2), 173–208.

- Crenshaw, K. (1997). “Intersectionality and Identity Politics: Learning from Violence against Women of Colour,” in Reconstructing Political Identity. Eds. M. Lyndon shanaey and U. Narayan. University Park, PA.: Pennsylvania State University Press, 178–193.

- Davis, A. E., and K. G. Shaver. (2012). “Understanding Gendered Variations in Business Growth Intentions across the Life Course,” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 36(3), 495–512.

- de Bruin, A., C. G. Brush, and F. Welter. (2007). “Advancing a Framework for Coherent Research on Women's Entrepreneurship,” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 31(3), 323–339.

- Derks, B., N. Ellemers, C. van Laar, and K. De Groot. (2011). “Do Sexist Organizational Cultures Create the Queen Bee?,” British Journal of Social Psychology 50(3), 519–535.

- Diaz‐garcia, M. C. D., and F. Welter. (2013). “Gender Identities and Practices: Interpreting Women Entrepreneurs' Narratives,” International Small Business Journal 31(4), 384–404.

- Essers, C., and Y. Benschop. (2009). “Muslim Businesswomen Doing Boundary Work: The Negotiation of Islam, Gender and Ethnicity within Entrepreneurial Contexts,” Human Relations 62(3), 403–423.

- Essers, C., and D. Tedmanson. (2014). “Upsetting ‘Others’ in the Netherlands: Narratives of Muslim Turkish Migrant Businesswomen at the Crossroads of Ethnicity, Gender and Religion,” Gender, Work and Organization 21(4), 353–367.

- Galloway, L., I. Kapasi, and K. Sang. (2015). “Entrepreneurship, Leadership, and the Value of Feminist Approaches to Understanding Them,” Journal of Small Business Management 53(3), 683–692.

- Gherardi, S., and B. Poggio. (2007). Gender‐Telling in Organizations: Narratives from Male‐Dominated Environments. Copenhagen, Denmark: Copenhagen Business School Press.

- Glaser, B., and A. Strauss. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

- Greenberg, D., K. Mckone‐sweet, and H. J. Wilson. (2011). The New Entrepreneurial Leaders: Developing Leaders Who Shape Social and Economic Opportunity. San Francisco, CA: Berrett‐Koehler.

- Hamilton, E. (2013). “The Discourse of Entrepreneurial Masculinities (and Femininities),” Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 25(1–2), 90–99.

- Harding, S. G. (1987). Feminism and Methodology: Social Science Issues. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Harrison, R., C. Leitch, and M. Mcadam. (2015). “Breaking Glass: Toward a Gendered Analysis of Entrepreneurial Leadership,” Journal of Small Business Management 53(3), 693–713.

- Henry, C., L. Foss, A. Fayolle, E. Walker, and S. Duffy. (2015). “Entrepreneurial Leadership and Gender: Exploring Theory and Practice in Global Contexts,” Journal of Small Business Management 53(3), 581–586.

- Holvino, E. (2010). “Intersections: The Simultaneity of Race, Gender and Class in Organization Studies,” Gender, Work and Organization 17(3), 248–277.

- Itani, H., Y. M. Sidani, and I. Baalbaki. (2011). “United Arab Emirates Female Entrepreneurs: Motivations and Frustrations,” Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal 30(5), 409–424.

- Javadian, G., and R. P. Singh. (2012). “Examining Successful Iranian Women Entrepreneurs: An Exploratory Study,” Gender in Management: An International Journal 27(3), 148–164.

- Karam, C. M., F. Afiouni, and N. Nasr. (2013). “Walking a Tightrope or Navigating a Web: Parameters of Balance within Perceived Institutional Realities,” Women's Studies International Forum 40(October), 87–101.

- Kelan, E. K. (2009). “Gender Fatigue: The Ideological Dilemma of Gender Neutrality and Discrimination in Organizations,” Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences 26(3), 197–210.

- Kempster, S., and J. Cope. (2010). “Learning to Lead in the Entrepreneurial Context,” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research 16(1), 5–34.

- Kuratko, D. F. (2007). “Entrepreneurial Leadership in the 21st Century,” Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies 13(4), 1–12.

- Leitch, C. M., F. M. Hill, and R. T. Harrison. (2010). “The Philosophy and Practice of Interpretivist Research in Entrepreneurship: Quality, Validation, and Trust,” Organizational Research Method 13(1), 67–84.

- Leitch, C. M., C. Mcmullan, and R. T. Harrison. (2013). “The Development of Entrepreneurial Leadership: The Role of Human, Social and Institutional Capital,” British Journal of Management 24(3), 347–366.